A Dataset of Standard and Abrupt Industrial Gestures Recorded Through MIMUs

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Dataset Collection and Design

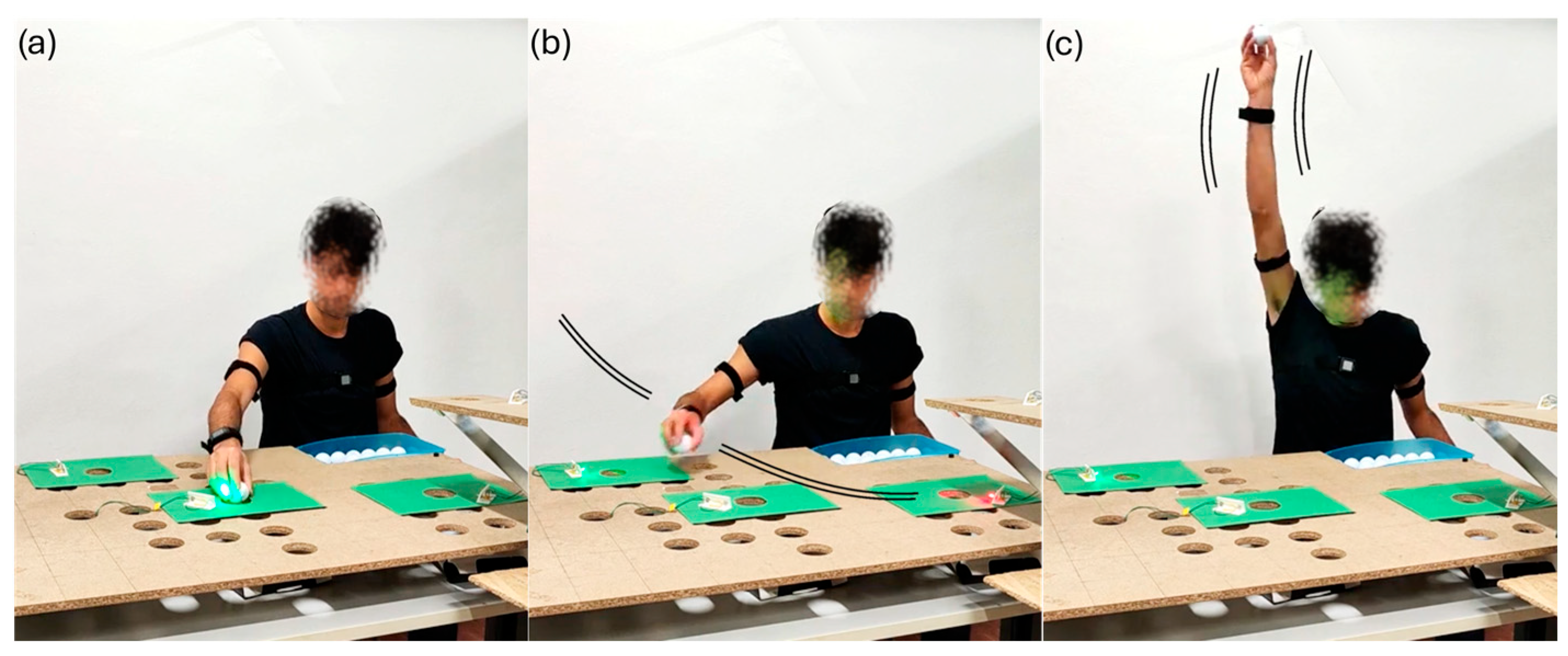

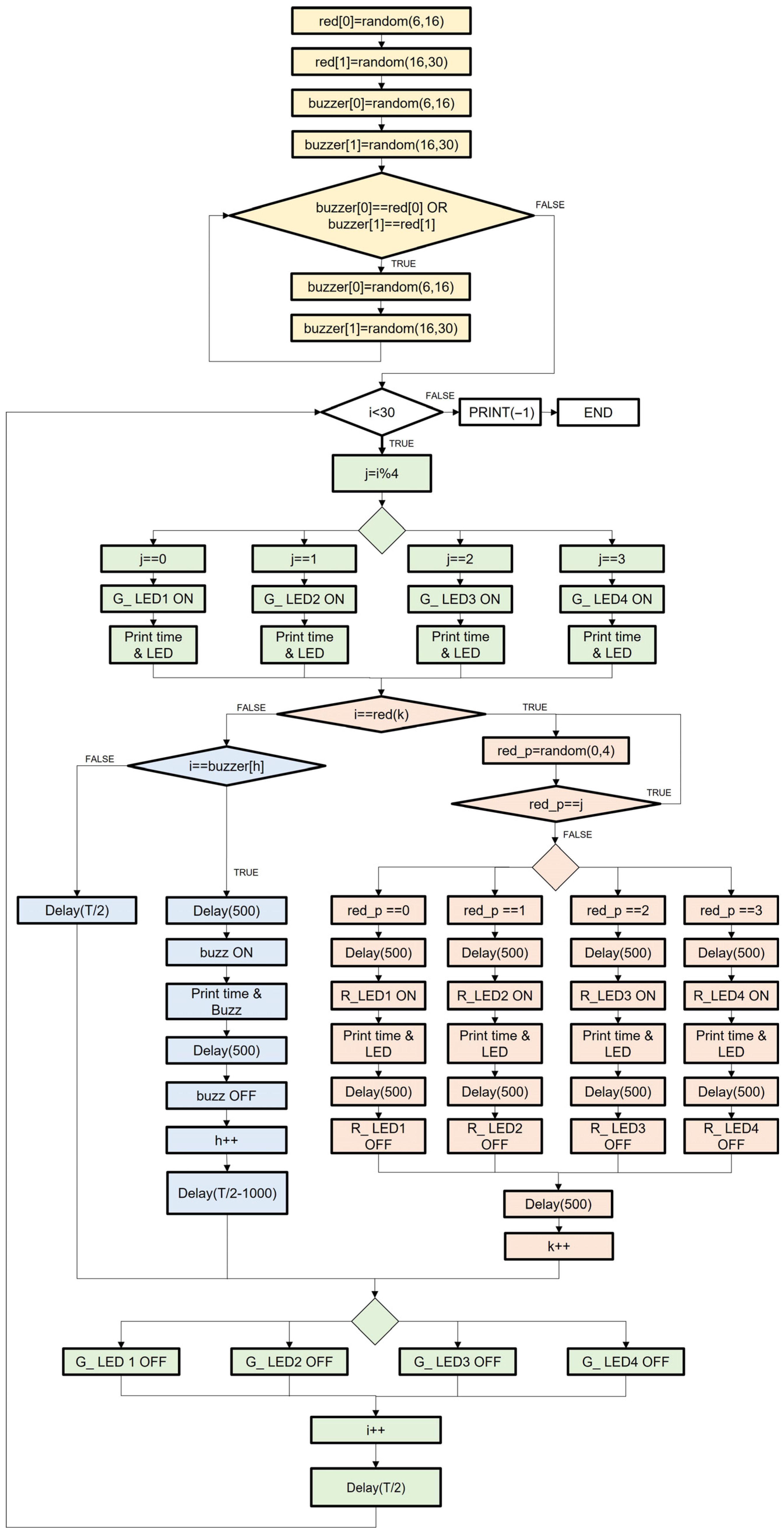

2.1. Experimental Setting and Data Collection

- Six participants in the range 20–24 years;

- Forty-one participants in the range 25–29 years;

- Eleven participants in the range 30–34 years;

- One participant in the range 50–54;

- One participant in the range 55–59.

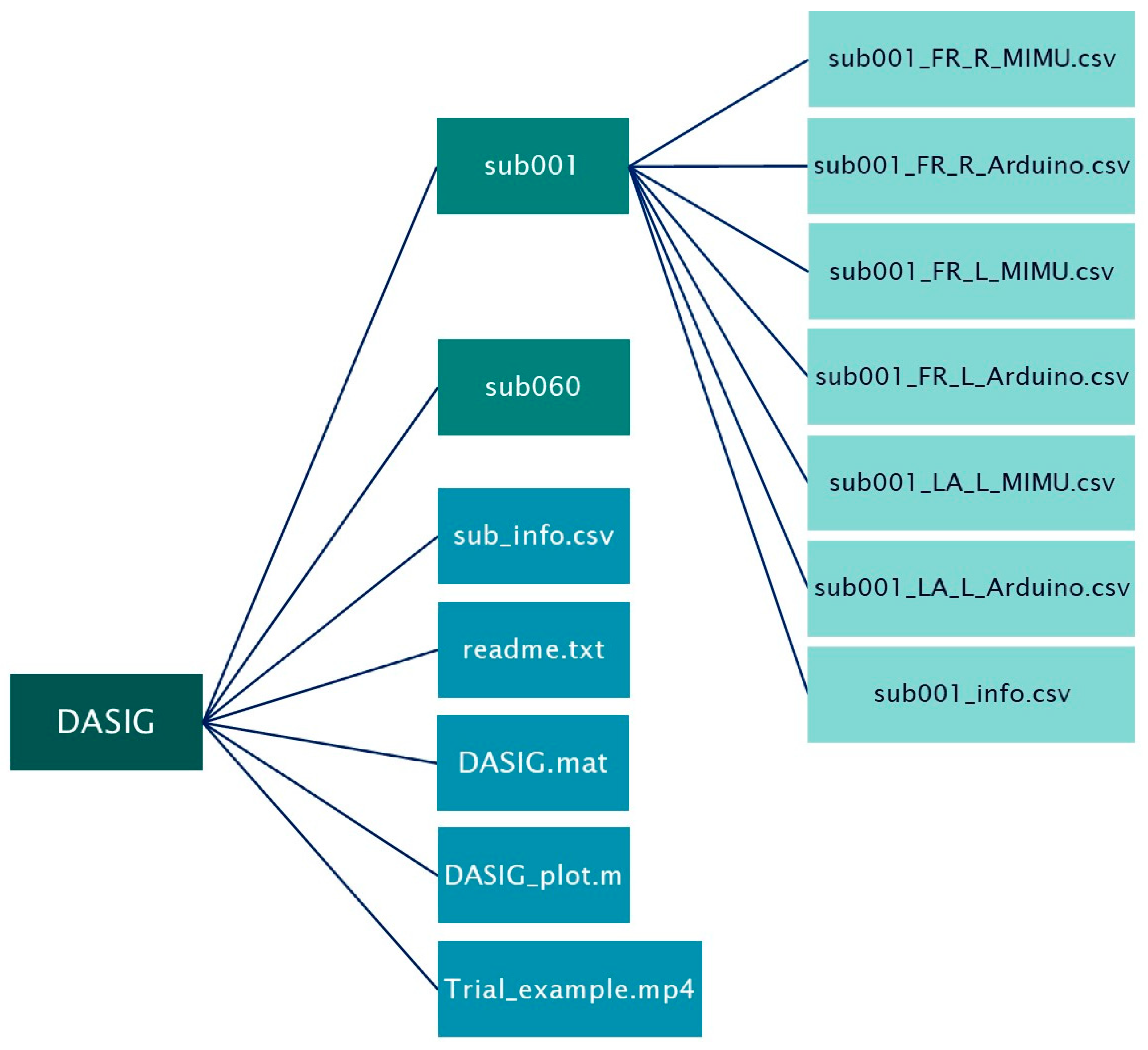

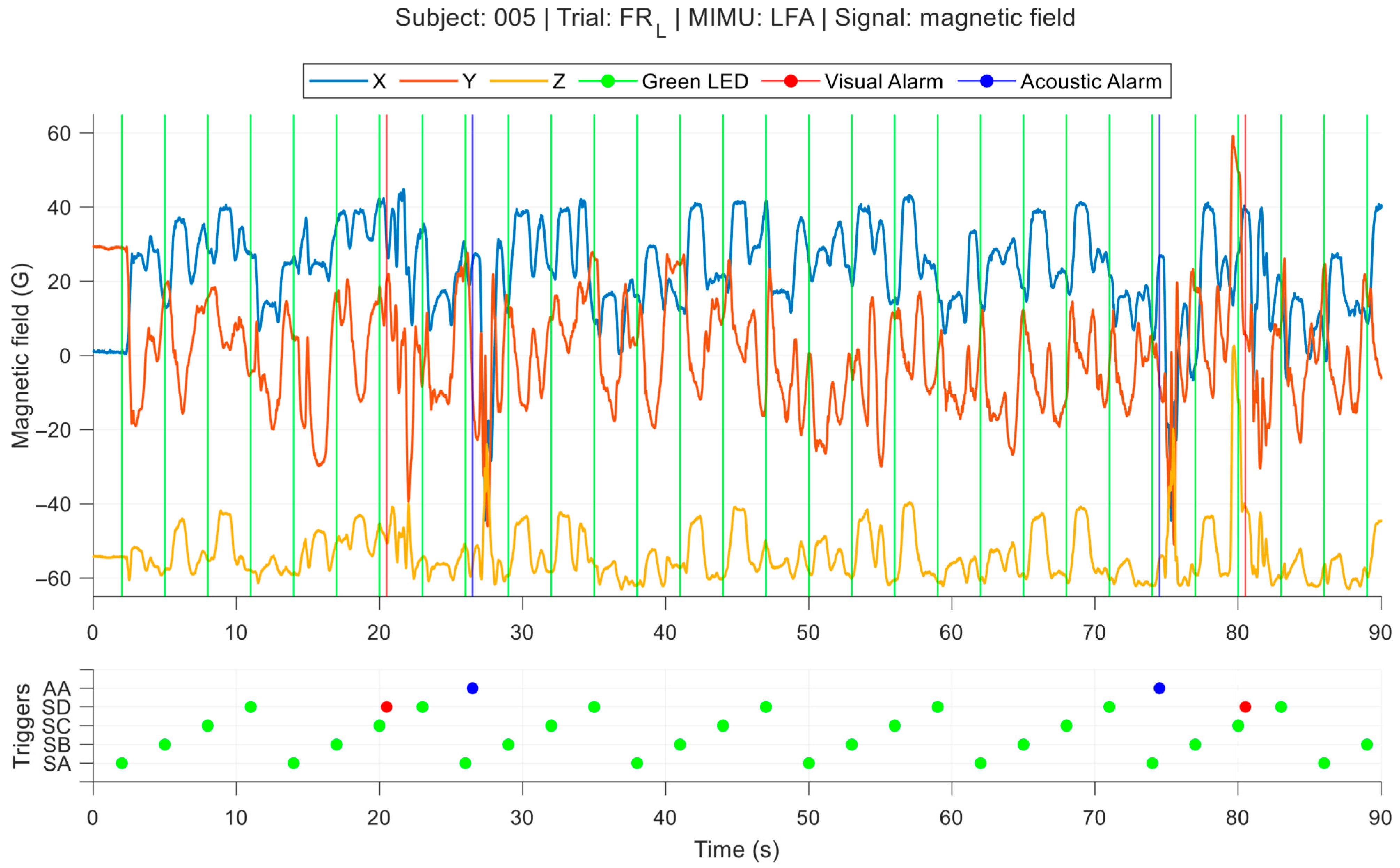

2.2. Database Structure

- Data collected from all MIMUs related to the three different trials (subXXX_FR_R_MIMU.csv, subXXX_FR_L_MIMU.csv, subXXX_LA_L_MIMU.csv). Each .csv file contains:

- o

- Time (s) of the acquisition with a sampling frequency of 200 Hz;

- o

- Accelerations (m/s2) along the three sensor axes;

- o

- Angular velocities (rad/s) around the three sensor axes;

- o

- Magnetic fields (G) along the three sensor axes;

- o

- Orientation (expressed in form of quaternions) of the sensor with respect to the Earth reference frame.

- Data collected from Arduino system related to the three different trials (subXXX_FR_R_Arduino.csv, subXXX_FR_L_Arduino.csv, subXXX_LA_L_Arduino.csv). Each .csv file contains:

- o

- Sequence of temporal instants (s) corresponding to the occurrence of specific events during the test (lighting of a green LED, lighting of a red LED, and activation of the sound buzzer);

- o

- Numeric code identifying the type of each event and the specific station in which it occurs. In detail, numbers from 2 to 5 indicate the lighting of a green LED, numbers from 6 to 9 indicate the lighting of a red LED, and number 10 indicates the activation of the sound buzzer. Specifically, numbers 2 and 6 identify events occurred in the station SA, numbers 3 and 7 events occurred in the station SB, numbers 4 and 8 events occurred in the station SC, and numbers 5 and 9 identify events occurred in the station SD.

- o

- Anthropometric data of the subject: gender, age range (years), height (m), weight (kg), dominant arm, right upper arm length (m), left upper arm length (m), right forearm length (m), left forearm length (m).

2.3. Database Statistics

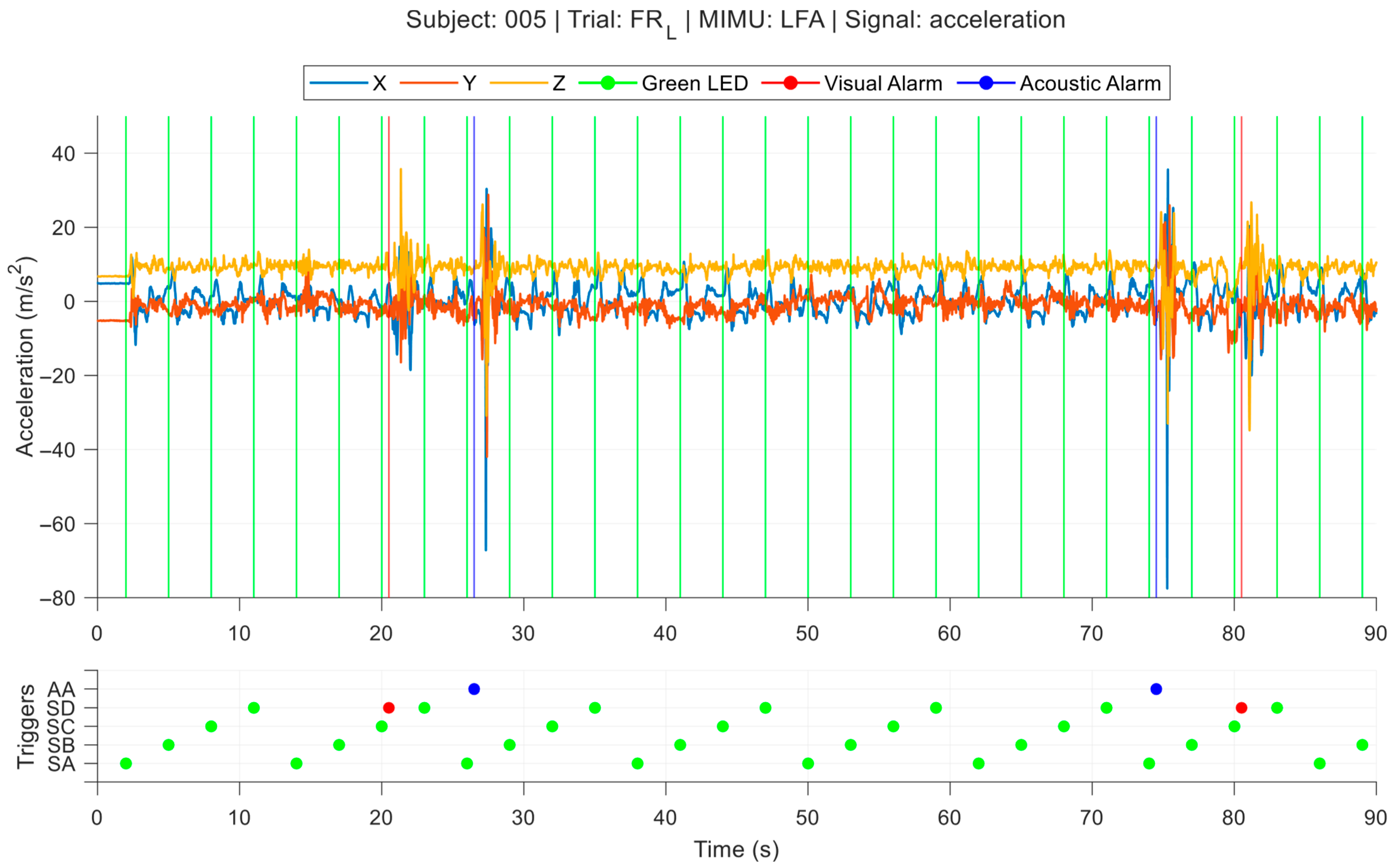

3. Database Demonstration

4. Discussions

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- ISO/TS 15066:2016; Robots and Robotic Devices—Collaborative Robots. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2016.

- Digo, E.; Polito, M.; Pastorelli, S.; Gastaldi, L. Detection of upper limb abrupt gestures for human–machine interaction using deep learning techniques. J. Braz. Soc. Mech. Sci. Eng. 2024, 46, 227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, Y.; Faccio, M.; Galizia, F.G.; Mora, C.; Pilati, F. Assembly system configuration through Industry 4.0 principles: The expected change in the actual paradigms. IFAC-PapersOnLine 2017, 50, 14958–14963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quintero, C.P.; Tatsambon, R.; Gridseth, M.; Jagersand, M. Visual pointing gestures for bi-directional human robot interaction in a pick-and-place task. In Proceedings of the 2015 24th IEEE International Symposium on Robot and Human Interactive Communication (RO-MAN), Kobe, Japan, 31 August–4 September 2015; pp. 349–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boldo, M.; Bombieri, N.; Centomo, S.; De Marchi, M.; Demrozi, F.; Pravadelli, G.; Quaglia, D.; Turetta, C. Integrating Wearable and Camera Based Monitoring in the Digital Twin for Safety Assessment in the Industry 4.0 Era. In Leveraging Applications of Formal Methods, Verification and Validation. Practice; Lecture Notes in Computer Science (Including Subseries Lecture Notes in Artificial Intelligence and Lecture Notes in Bioinformatics); Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; Volume 13704 LNCS, pp. 184–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Feudis, I.; Buongiorno, D.; Grossi, S.; Losito, G.; Brunetti, A.; Longo, N.; Di Stefano, G.; Bevilacqua, V. Evaluation of Vision-Based Hand Tool Tracking Methods for Quality Assessment and Training in Human-Centered Industry 4.0. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 1796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calderón-Sesmero, R.; Lozano-Hernández, A.; Frontela-Encinas, F.; Cabezas-López, G.; De-Diego-Moro, M. Human–Robot Interaction and Tracking System Based on Mixed Reality Disassembly Tasks. Robotics 2025, 14, 106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raj, R.; Kos, A. Study of Human–Robot Interactions for Assistive Robots Using Machine Learning and Sensor Fusion Technologies. Electronics 2024, 13, 3285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dallel, M.; Havard, V.; Baudry, D.; Savatier, X. InHARD-Industrial Human Action Recognition Dataset in the Context of Industrial Collaborative Robotics. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE International Conference on Human-Machine Systems, ICHMS 2020, Rome, Italy, 7–9 September 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lagamtzis, D.; Schmidt, F.; Seyler, J.; Dang, T. CoAx: Collaborative Action Dataset for Human Motion Forecasting in an Industrial Workspace. Scitepress 2022, 3, 98–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudenko, A.; Kucner, T.P.; Swaminathan, C.S.; Chadalavada, R.T.; Arras, K.O.; Lilienthal, A.J. THÖR: Human-Robot Navigation Data Collection and Accurate Motion Trajectories Dataset. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 2020, 5, 676–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delamare, M.; Duval, F.; Boutteau, R. A new dataset of people flow in an industrial site with uwb and motion capture systems. Sensors 2020, 20, 4511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tamantini, C.; Cordella, F.; Lauretti, C.; Zollo, L. The WGD—A dataset of assembly line working gestures for ergonomic analysis and work-related injuries prevention. Sensors 2021, 21, 7600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kratzer, P.; Bihlmaier, S.; Midlagajni, N.B.; Prakash, R.; Toussaint, M.; Mainprice, J. MoGaze: A Dataset of Full-Body Motions that Includes Workspace Geometry and Eye-Gaze. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 2021, 6, 367–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duarte, L.; Neto, P. Classification of primitive manufacturing tasks from filtered event data. J. Manuf. Syst. 2023, 68, 12–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Digo, E.; Pastorelli, S.; Gastaldi, L. A Narrative Review on Wearable Inertial Sensors for Human Motion Tracking in Industrial Scenarios. Robotics 2022, 11, 138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olivas-Padilla, B.E.; Glushkova, A.; Manitsaris, S. Motion Capture Benchmark of Real Industrial Tasks and Traditional Crafts for Human Movement Analysis. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 40075–40092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maurice, P.; Malaisé, A.; Amiot, C.; Paris, N.; Richard, G.-J.; Rochel, O.; Ivaldi, S. Human movement and ergonomics: An industry-oriented dataset for collaborative robotics. Int. J. Robot. Res. 2019, 38, 1529–1537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Digo, E.; Polito, M.; Caselli, E.; Gastaldi, L.; Pastorelli, S. Dataset of Standard and Abrupt Industrial Gestures (DASIG). 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| FR_R | FR_L | LA_L | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Standard | Abrupt | Standard | Abrupt | Standard | Abrupt | |

| Acceleration (m/s2) | 9.96 ± 0.14 | 11.18 ± 1.17 | 9.98 ± 0.11 | 11.07 ± 1.01 | 9.96 ± 0.11 | 10.97 ± 0.91 |

| p-value | <0.01 ** | <0.01 ** | <0.01 ** | |||

| Angular velocity (rad/s) | 1.29 ± 0.35 | 2.11 ± 0.73 | 0.98 ± 0.25 | 1.94 ± 0.74 | 1.12 ± 0.33 | 1.97 ± 0.68 |

| p-value | <0.01 ** | <0.01 ** | <0.01 ** | |||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Digo, E.; Polito, M.; Caselli, E.; Gastaldi, L.; Pastorelli, S. A Dataset of Standard and Abrupt Industrial Gestures Recorded Through MIMUs. Robotics 2025, 14, 176. https://doi.org/10.3390/robotics14120176

Digo E, Polito M, Caselli E, Gastaldi L, Pastorelli S. A Dataset of Standard and Abrupt Industrial Gestures Recorded Through MIMUs. Robotics. 2025; 14(12):176. https://doi.org/10.3390/robotics14120176

Chicago/Turabian StyleDigo, Elisa, Michele Polito, Elena Caselli, Laura Gastaldi, and Stefano Pastorelli. 2025. "A Dataset of Standard and Abrupt Industrial Gestures Recorded Through MIMUs" Robotics 14, no. 12: 176. https://doi.org/10.3390/robotics14120176

APA StyleDigo, E., Polito, M., Caselli, E., Gastaldi, L., & Pastorelli, S. (2025). A Dataset of Standard and Abrupt Industrial Gestures Recorded Through MIMUs. Robotics, 14(12), 176. https://doi.org/10.3390/robotics14120176