Yeast NatB Regulates Cell Death of Bax-Expressing Cells

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Yeast Strains and Plasmids

2.2. Growth Conditions

2.3. Acetic Acid Treatment

2.4. Assessment of Plasma Membrane Integrity

2.5. Western Blot Analysis

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

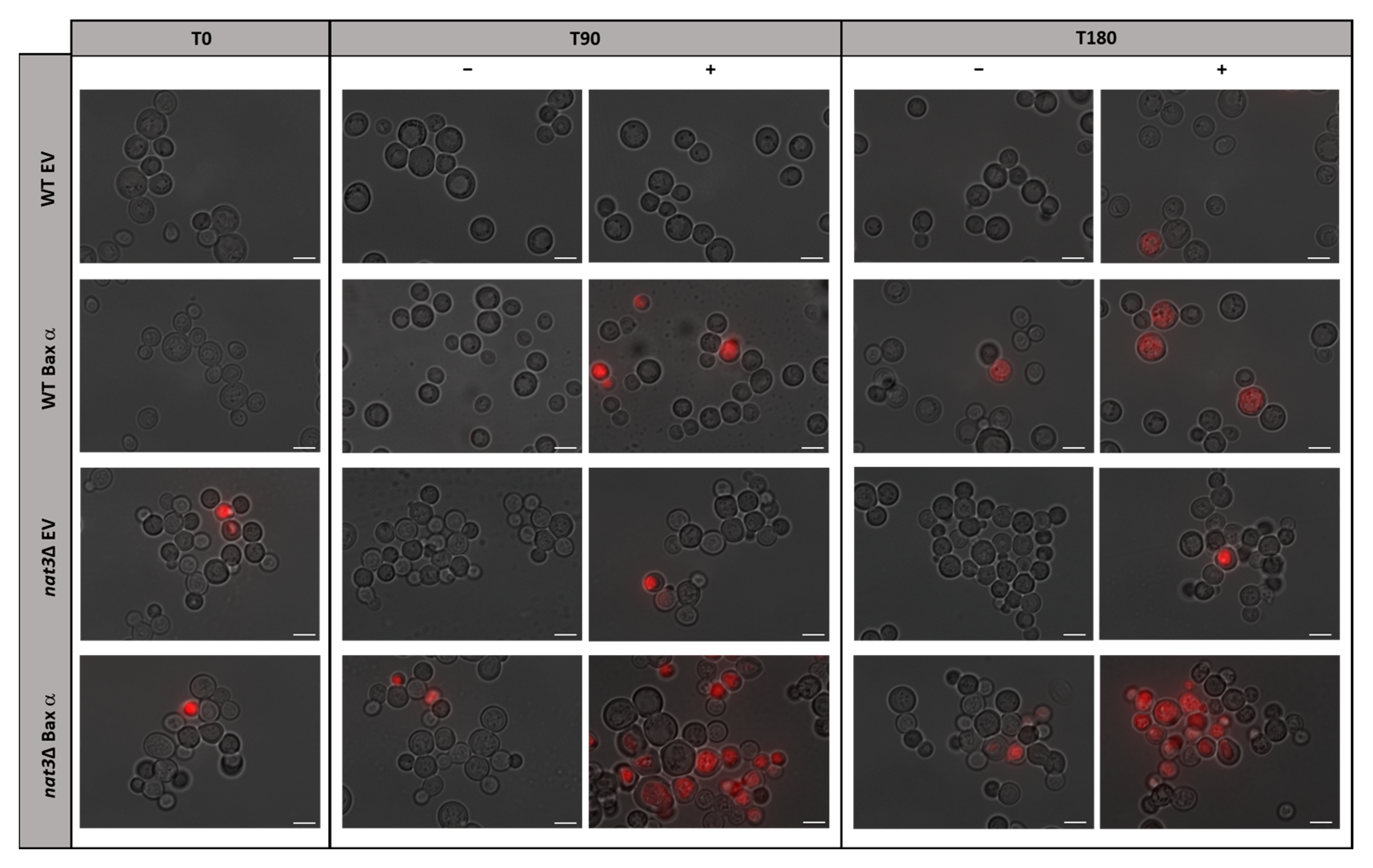

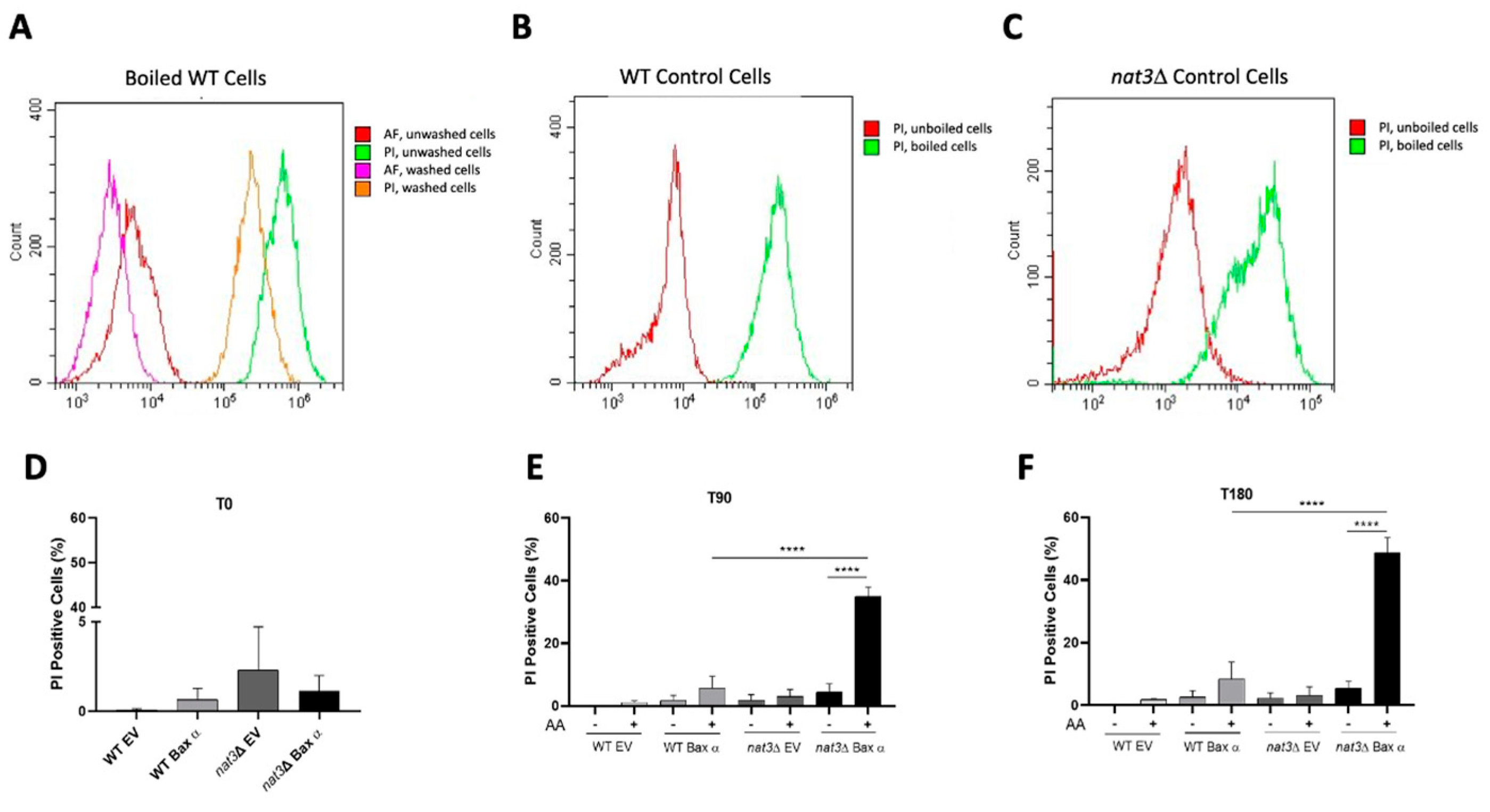

3.1. Deletion of NAT3 Increases the Susceptibility of Yeast Cells Expressing Human Bax α to Acetic Acid

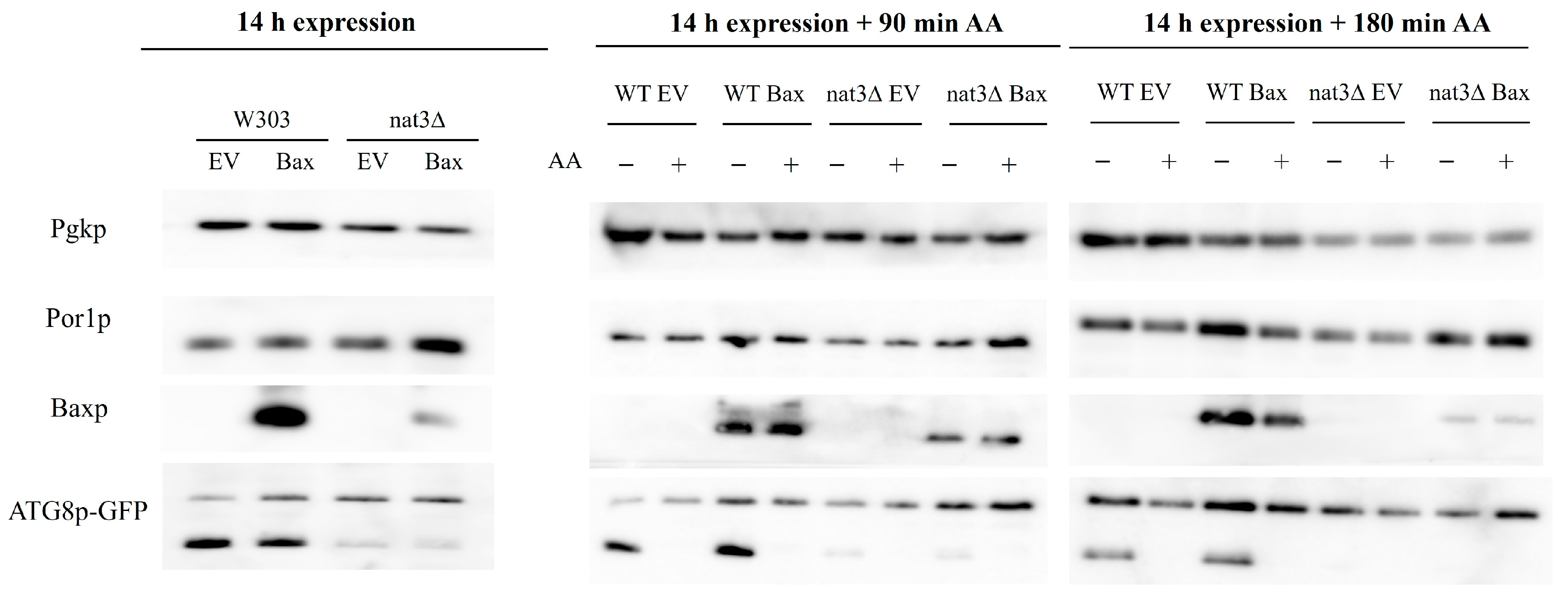

3.2. The Increased Susceptibility of nat3Δ Yeast Cells Expressing Human Bax α to Acetic Acid Is Associated with Autophagy Inhibition

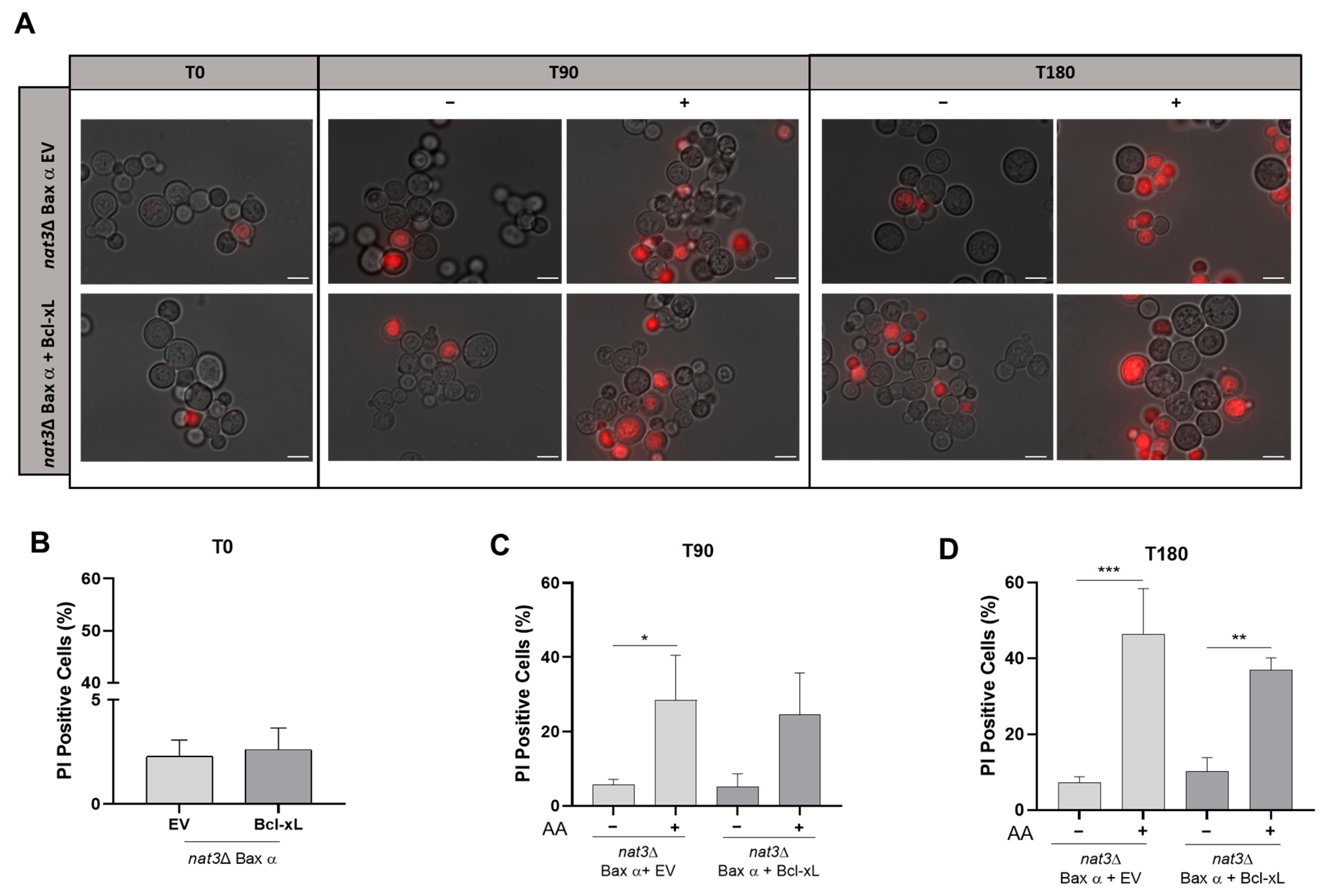

3.3. Bcl-xL Does Not Rescue nat3Δ Yeast Cells Expressing Human Bax α from Acetic Acid-Induced Cell Death

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Schellenberg, B.; Wang, P.; Keeble, J.A.; Rodriguez-Enriquez, R.; Walker, S.; Owens, T.W.; Foster, F.; Tanianis-Hughes, J.; Brennan, K.; Streuli, C.H.; et al. Bax Exists in a Dynamic Equilibrium between the Cytosol and Mitochondria to Control Apoptotic Priming. Mol. Cell 2013, 49, 959–971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalkavan, H.; Green, D.R. MOMP, cell suicide as a BCL-2 family business. Cell Death Differ. 2017, 25, 46–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, D.R.; Llambi, F. Cell death signaling. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2015, 7, a006080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kale, J.; Osterlund, E.J.; Andrews, D.W. BCL-2 family proteins: Changing partners in the dance towards death. Cell Death Differ. 2018, 25, 65–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czabotar, P.E.; Lessene, G.; Strasser, A.; Adams, J.M. Control of apoptosis by the BCL-2 protein family: Implications for physiology and therapy. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2014, 15, 49–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crawford, E.D.; Wells, J.A. Caspase Substrates and Cellular Remodeling. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2011, 80, 1055–1087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Letai, A.; Kutuk, O. Regulation of Bcl-2 Family Proteins by Posttranslational Modifications. Curr. Mol. Med. 2008, 8, 102–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alves, S.; Neiri, L.; Chaves, S.R.; Vieira, S.; Trindade, D.; Manon, S.; Dominguez, V.; Pintado, B.; Jonckheere, V.; Van Damme, P.; et al. N-terminal acetylation modulates Bax targeting to mitochondria. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2018, 95, 35–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gauci, S.; Helbig, A.O.; Slijper, M.; Krijgsveld, J.; Heck, A.J.R.; Mohammed, S. Lys-N and Trypsin Cover Complementary Parts of the Phosphoproteome in a Refined SCX-Based Approach. Anal. Chem. 2009, 81, 4493–4501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacome, A.S.V.; Rabilloud, T.; Schaeffer-Reiss, C.; Rompais, M.; Ayoub, D.; Lane, L.; Bairoch, A.; Van Dorsselaer, A.; Carapito, C. N-terminome analysis of the human mitochondrial proteome. Proteomics 2015, 15, 2519–2524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Damme, P.; Lasa, M.; Polevoda, B.; Gazquez, C.; Elosegui-Artola, A.; Kim, D.S.; De Juan-Pardo, E.; Demeyer, K.; Hole, K.; Larrea, E.; et al. N-terminal acetylome analyses and functional insights of the N-terminal acetyltransferase NatB. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2012, 109, 12449–12454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Damme, P.; Osberg, C.; Jonckheere, V.; Glomnes, N.; Gevaert, K.; Arnesen, T.; Aksnes, H. Expanded in vivo substrate profile of the yeast N-terminal acetyltransferase NatC. J. Biol. Chem. 2022, 299, 102824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arokium, H.; Ouerfelli, H.; Velours, G.; Camougrand, N.; Vallette, F.M.; Manon, S. Substitutions of Potentially Phosphorylatable Serine Residues of Bax Reveal How They May Regulate Its Interaction with Mitochondria. J. Biol. Chem. 2007, 282, 35104–35112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renault, T.T.; Teijido, O.; Missire, F.; Ganesan, Y.T.; Velours, G.; Arokium, H.; Beaumatin, F.; Llanos, R.; Athané, A.; Camougrand, N.; et al. Bcl-xL stimulates Bax relocation to mitochondria and primes cells to ABT-737. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2015, 64, 136–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noda, T.; Matsuura, A.; Wada, Y.; Ohsumi, Y. Novel System for Monitoring Autophagy in the Yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1995, 210, 126–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gietz, R.D.; Woods, R.A. Yeast Transformation by the LiAc/SS Carrier DNA/PEG Method. In Yeast Protocols; Humana Press: Totowa, NJ, USA; pp. 107–120. [CrossRef]

- Casal, M.; Cardoso, H.; Leao, C. Mechanisms regulating the transport of acetic acid in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Microbiology 1996, 142, 1385–1390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guedes, J.P.; Baptista, V.; Santos-Pereira, C.; Sousa, M.J.; Manon, S.; Chaves, S.R.; Côrte-Real, M. Acetic acid triggers cytochrome c release in yeast heterologously expressing human Bax. Apoptosis 2022, 27, 368–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caesar, R.; Warringer, J.; Blomberg, A. Physiological Importance and Identification of Novel Targets for the N-Terminal Acetyltransferase NatB. Eukaryot. Cell 2006, 5, 368–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Polevoda, B.; Cardillo, T.S.; Doyle, T.C.; Bedi, G.S.; Sherman, F. Nat3p and Mdm20p Are Required for Function of Yeast NatB Nα-terminal Acetyltransferase and of Actin and Tropomyosin. J. Biol. Chem. 2003, 278, 30686–30697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kiššová, I.; Plamondon, L.-T.; Brisson, L.; Priault, M.; Renouf, V.; Schaeffer, J.; Camougrand, N.; Manon, S. Evaluation of the Roles of Apoptosis, Autophagy, and Mitophagy in the Loss of Plating Efficiency Induced by Bax Expression in Yeast. J. Biol. Chem. 2006, 281, 36187–36197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, T.; Jiang, L.; Wang, X.; Xu, Q.; Han, L.; Liu, S.; Huang, T.; Li, H.; Dai, L.; Li, H.; et al. Function and molecular mechanism of N-terminal acetylation in autophagy. Cell Rep. 2021, 37, 109937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pereira, C.; Chaves, S.; Alves, S.; Salin, B.; Camougrand, N.; Manon, S.; Sousa, M.J.; Côrte-Real, M. Mitochondrial degradation in acetic acid-induced yeast apoptosis: The role of Pep4 and the ADP/ATP carrier. Mol. Microbiol. 2010, 76, 1398–1410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rego, A.; Ribeiro, A.; Côrte-Real, M.; Chaves, S.R. Monitoring yeast regulated cell death: Trespassing the point of no return to loss of plasma membrane integrity. Apoptosis 2022, 27, 778–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, M.; Youle, R.J.; Tjandra, N. Structure of Bax: Coregulation of dimer formation and intracellular localization. Cell 2000, 103, 645–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arokium, H.; Camougrand, N.; Vallette, F.M.; Manon, S. Studies of the interaction of substituted mutants of BAX with yeast mitochondria reveal that the C-terminal hydrophobic alpha-helix is a second ART sequence and plays a role in the interaction with anti-apoptotic BCL-xL. J. Biol. Chem. 2004, 279, 52566–52573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lalier, L.; Vallette, F.; Manon, S. Bcl-2 Family Members and the Mitochondrial Import Machineries: The Roads to Death. Biomolecules 2022, 12, 162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ametzazurra, A.; Larrea, E.; Civeira, M.P.; Prieto, J.; Aldabe, R. Implication of human N-α-acetyltransferase 5 in cellular proliferation and carcinogenesis. Oncogene 2008, 27, 7296–7306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Friedrich, U.A.; Zedan, M.; Hessling, B.; Fenzl, K.; Gillet, L.; Barry, J.; Knop, M.; Kramer, G.; Bukau, B. Nα-terminal acetylation of proteins by NatA and NatB serves distinct physiological roles in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Cell Rep. 2021, 34, 108711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaves, S.R.; Rego, A.; Santos-Pereira, C.; Sousa, M.J.; Côrte-Real, M. Current and novel approaches in yeast cell death research. Cell Death Differ. 2024, 32, 207–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silva, M.T. Secondary necrosis: The natural outcome of the complete apoptotic program. FEBS Lett. 2010, 584, 4491–4499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crompton, M.; Virji, S.; Ward, J.M. Cyclophilin-D binds strongly to complexes of the voltage-dependent anion channel and the adenine nucleotide translocase to form the permeability transition pore. Eur. J. Biochem. 1998, 258, 729–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halestrap, A.P. What is the mitochondrial permeability transition pore? J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 2009, 46, 821–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kokoszka, J.E.; Waymire, K.G.; Levy, S.E.; Sligh, J.E.; Cai, J.; Jones, D.P.; MacGregor, G.R.; Wallace, D.C. The ADP/ATP translocator is not essential for the mitochondrial permeability transition pore. Nature 2004, 427, 461–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baines, C.P.; Kaiser, R.A.; Sheiko, T.; Craigen, W.J.; Molkentin, J.D. Voltage-dependent anion channels are dispensable for mitochondrial-dependent cell death. Nat. Cell Biol. 2007, 9, 550–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baines, C.P.; Kaiser, R.A.; Purcell, N.H.; Blair, N.S.; Osinska, H.; Hambleton, M.A.; Brunskill, E.W.; Sayen, M.R.; Gottlieb, R.A.; Dorn, G.W., II; et al. Loss of cyclophilin D reveals a critical role for mitochondrial permeability transition in cell death. Nature 2005, 434, 658–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schinzel, A.C.; Takeuchi, O.; Huang, Z.; Fisher, J.K.; Zhou, Z.; Rubens, J.; Hetz, C.; Danial, N.N.; Moskowitz, M.A.; Korsmeyer, S.J. Cyclophilin D is a component of mitochondrial permeability transition and mediates neuronal cell death after focal cerebral ischemia. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2005, 102, 12005–12010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giorgio, V.; von Stockum, S.; Antoniel, M.; Fabbro, A.; Fogolari, F.; Forte, M.; Glick, G.D.; Petronilli, V.; Zoratti, M.; Szabó, I.; et al. Dimers of mitochondrial ATP synthase form the permeability transition pore. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2013, 110, 5887–5892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonora, M.; Bononi, A.; De Marchi, E.; Giorgi, C.; Lebiedzinska, M.; Marchi, S.; Patergnani, S.; Rimessi, A.; Suski, J.M.; Wojtala, A.; et al. Role of the c subunit of the FO ATP synthase in mitochondrial permeability transition. Cell Cycle 2013, 12, 674–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alavian, K.N.; Beutner, G.; Lazrove, E.; Sacchetti, S.; Park, H.-A.; Licznerski, P.; Li, H.; Nabili, P.; Hockensmith, K.; Graham, M.; et al. An uncoupling channel within the c-subunit ring of the F1F0 ATP synthase is the mitochondrial permeability transition pore. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2014, 111, 10580–10585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whelan, R.S.; Konstantinidis, K.; Wei, A.-C.; Chen, Y.; Reyna, D.E.; Jha, S.; Yang, Y.; Calvert, J.W.; Lindsten, T.; Thompson, C.B.; et al. Bax regulates primary necrosis through mitochondrial dynamics. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2012, 109, 6566–6571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karch, J.; Kwong, J.Q.; Burr, A.R.; Sargent, M.A.; Elrod, J.W.; Peixoto, P.M.; Martinez-Caballero, S.; Osinska, H.; Cheng, E.H.-Y.; Robbins, J.; et al. Bax and Bak function as the outer membrane component of the mitochondrial permeability pore in regulating necrotic cell death in mice. eLife 2013, 2, e00772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kissová, I.; Deffieu, M.; Manon, S.; Camougrand, N. Uth1p Is Involved in the Autophagic Degradation of Mitochondria. J. Biol. Chem. 2004, 279, 39068–39074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiššová, I.B.; Salin, B.; Schaeffer, J.; Bhatia, S.; Manon, S.; Camougrand, N. Selective and Non-Selective Autophagic Degradation of Mitochondria in Yeast. Autophagy 2007, 3, 329–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Welter, E.; Montino, M.; Reinhold, R.; Schlotterhose, P.; Krick, R.; Dudek, J.; Rehling, P.; Thumm, M. Uth1 is a mitochondrial inner membrane protein dispensable for post-log-phase and rapamycin-induced mitophagy. FEBS J. 2013, 280, 4970–4982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carmona-Gutiérrez, D.; Bauer, M.A.; Ring, J.; Knauer, H.; Eisenberg, T.; Büttner, S.; Ruckenstuhl, C.; Reisenbichler, A.; Magnes, C.; Rechberger, G.N.; et al. The propeptide of yeast cathepsin D inhibits programmed necrosis. Cell Death Dis. 2011, 2, e161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pereira, H.; Azevedo, F.; Rego, A.; Sousa, M.J.; Chaves, S.R.; Côrte-Real, M. The protective role of yeast Cathepsin D in acetic acid-induced apoptosis depends on ANT (Aac2p) but not on the voltage-dependent channel (Por1p). FEBS Lett. 2012, 587, 200–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, H.; Oliveira, C.; Castro, L.; Preto, A.; Chaves, S.R.; Corte-Real, M. Yeast as a tool to explore cathepsin D function. Microb. Cell 2015, 2, 225–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guedes, J.P.; Boyer, J.B.; Elurbide, J.; Carte, B.; Redeker, V.; Sago, L.; Meinnel, T.; Côrte-Real, M.; Giglione, C.; Aldabe, R. NatB Protects Procaspase-8 from UBR4-Mediated Degradation and Is Required for Full Induction of the Extrinsic Apoptosis Pathway. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2024, 44, 358–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Guedes, J.P.; Mendes, F.; Machado, B.O.; Manon, S.; Côrte-Real, M.; Chaves, S.R. Yeast NatB Regulates Cell Death of Bax-Expressing Cells. Biomolecules 2025, 15, 1731. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom15121731

Guedes JP, Mendes F, Machado BO, Manon S, Côrte-Real M, Chaves SR. Yeast NatB Regulates Cell Death of Bax-Expressing Cells. Biomolecules. 2025; 15(12):1731. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom15121731

Chicago/Turabian StyleGuedes, Joana P., Filipa Mendes, Beatriz O. Machado, Stéphen Manon, Manuela Côrte-Real, and Susana R. Chaves. 2025. "Yeast NatB Regulates Cell Death of Bax-Expressing Cells" Biomolecules 15, no. 12: 1731. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom15121731

APA StyleGuedes, J. P., Mendes, F., Machado, B. O., Manon, S., Côrte-Real, M., & Chaves, S. R. (2025). Yeast NatB Regulates Cell Death of Bax-Expressing Cells. Biomolecules, 15(12), 1731. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom15121731