Metabolomics Reveals Resistance-Related Secondary Metabolism in Sweet Cherry Infected by Alternaria alternata

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Test Materials

2.2. Test Strains

2.3. Field Disease-Resistance Evaluation

2.4. Method for Determination of RWC

2.5. Determination of REC

2.6. Determination of MDA Content

2.7. Metabolomics Determination

2.7.1. Biological Sample Preparation and Processing

2.7.2. Liquid Chromatography Conditions

2.7.3. Preprocessing of Raw Data

2.8. Data Analysis

3. Results

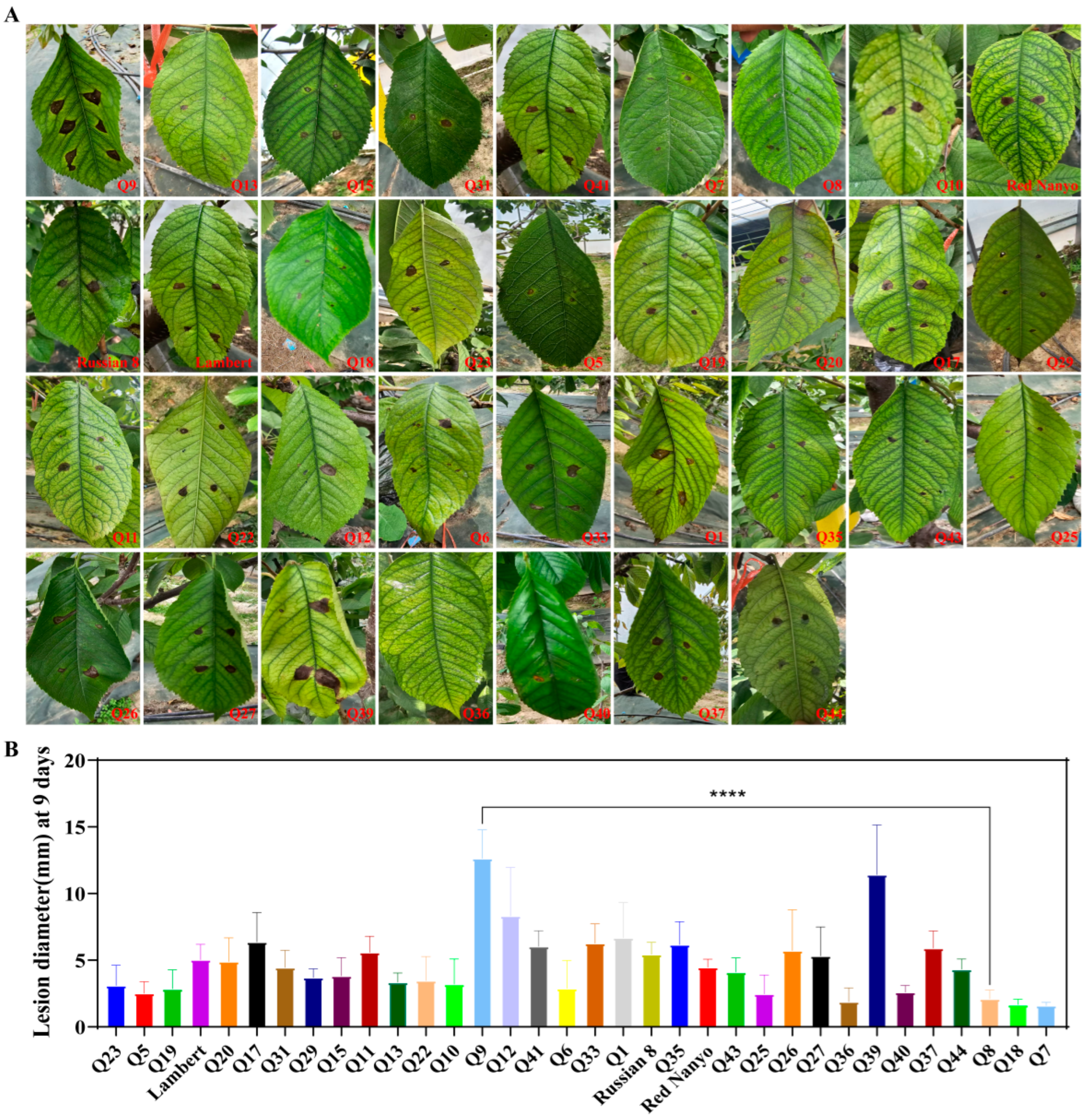

3.1. Screening of Cultivar for Field Resistance to BSD in Sweet Cherry

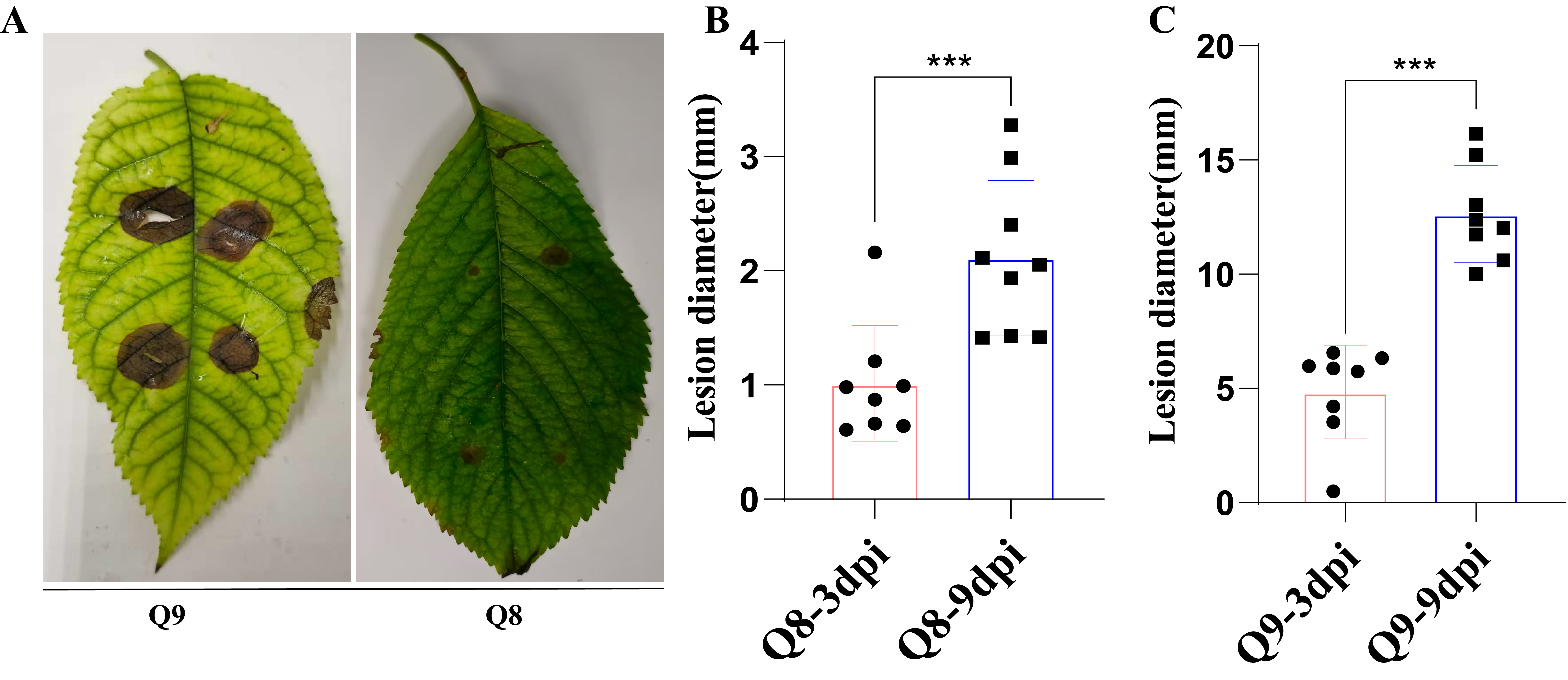

3.2. Confirmation of BSD Resistance in Resistant Sweet Cherry Cultivar Q8 and Susceptible Cultivar Q9

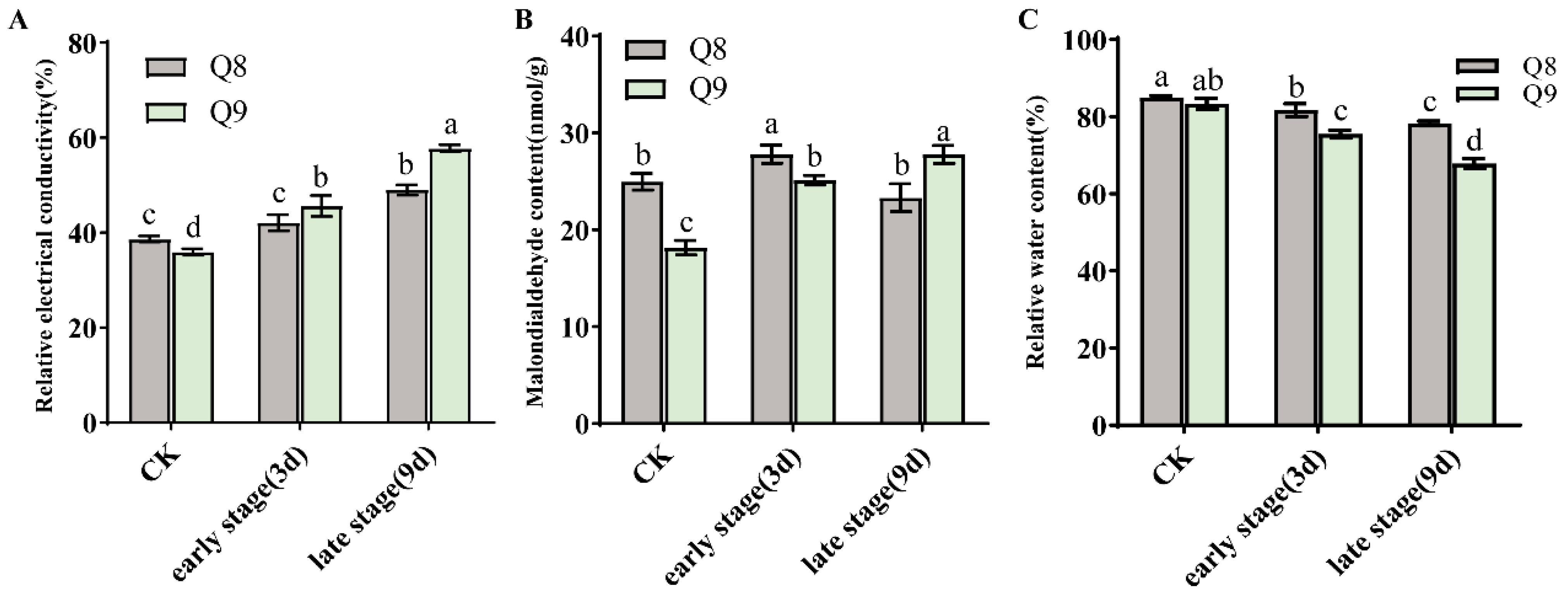

3.3. Physiological Changes in Leaves of Resistant Sweet Cherry Cultivar Q8 and Susceptible Cultivar Q9 Under BSD Infection

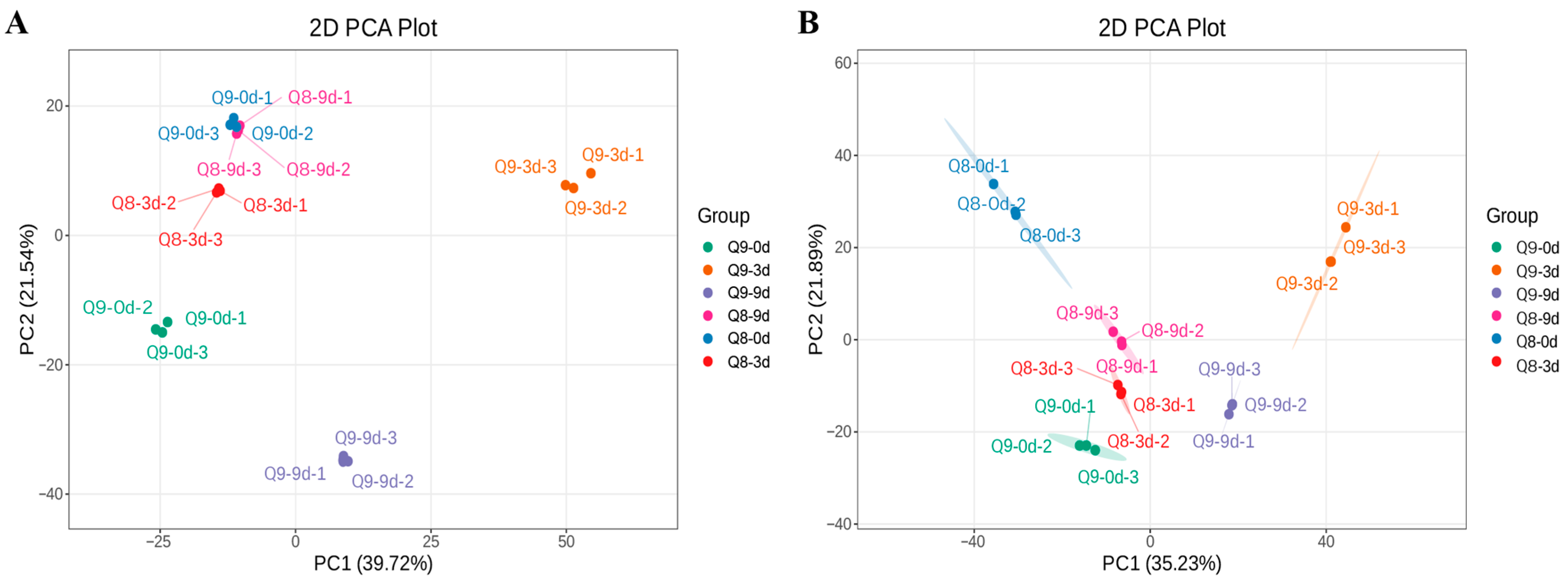

3.4. Principal Component Analysis of Metabolites in Sweet Cherry Leaves at Different Infection Stages Under Negative and Positive Modes

3.5. Statistics of Metabolites in Sweet Cherry Leaves at Different Infection Stages in Negative and Positive Ion Modes

3.6. OPLS-DA Analysis of Metabolites in Sweet Cherry Leaves at Different Infection Stages

3.7. Volcano Plot and Heatmap Analysis of Metabolites in Sweet Cherry Leaves at Different Infection Stages

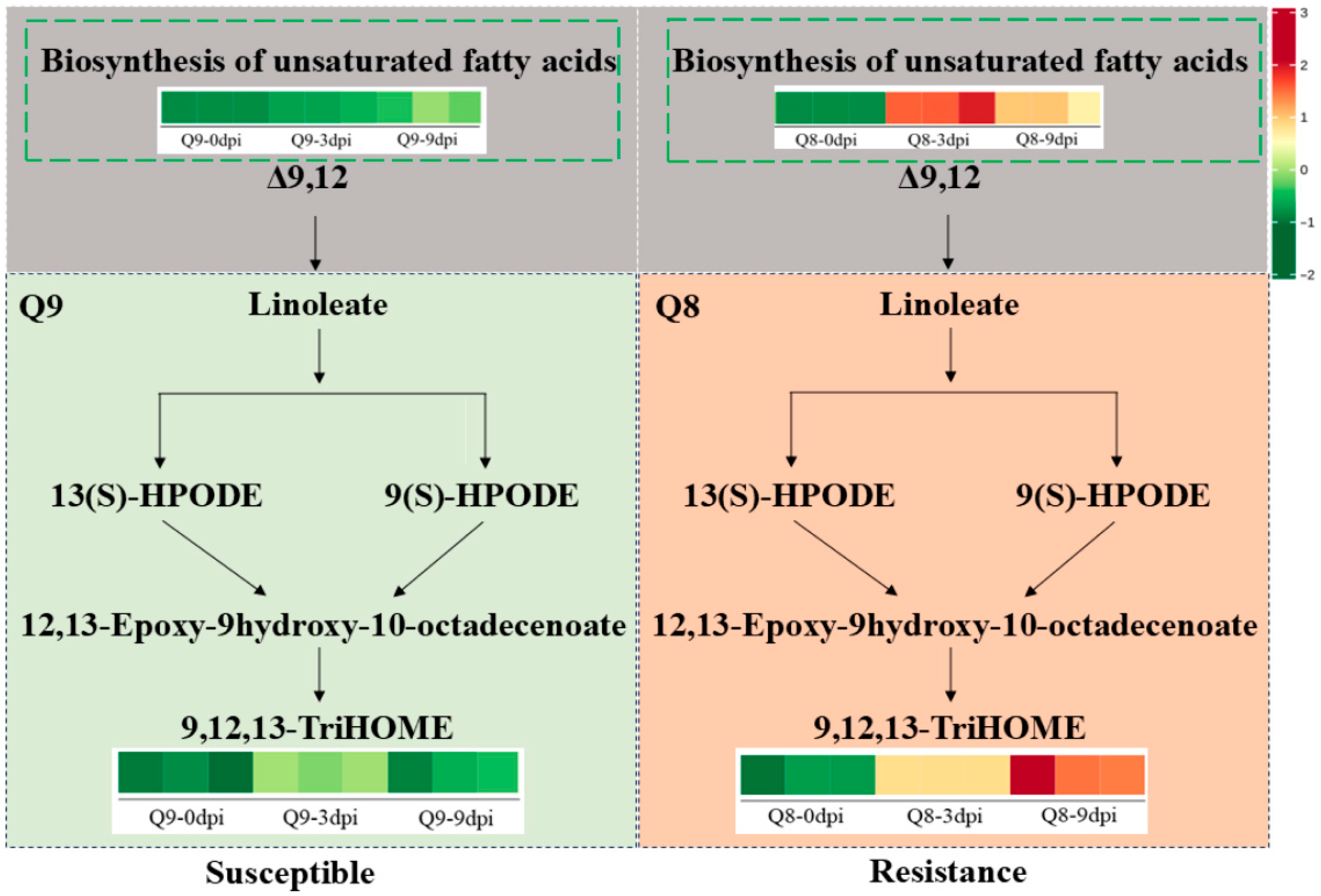

3.8. Identification of Active Metabolites Involved in BSD Resistance and Their Pathway Analysis in Q8

3.9. Metabolic Mechanisms Underlying BSD Resistance in Q8 and Susceptibility in Q9

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| dpi | days post-infection |

| BSD | Brown spot disease |

| REC | Relative Electrical Conductivity |

| MDA | Malondialdehyde |

| RWC | Relative Water Content |

| PCA | Principal component analysis |

| SVR | Support Vector Regression |

| FDR | False Discovery Rate |

| VIP | Variable Importance in the Projection |

| OPLS-DA | Orthogonal Partial Least Squares Discriminant Analysis |

| PDA | Potato Dextrose Agar |

| DAMs | Differentially Accumulated Metabolites |

| JA | Jasmonic acid |

| KEGG | Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes |

| WGCNA | Weighted Gene Co-expression Network Analysis |

| MAS | Marker-assisted selection |

References

- Wang, Y.Y.; Xiao, Y.Q.; Sun, Y.; Zhang, X.; Du, B.Y.; Turupu, M.; Yao, Q.S.; Gai, S.L.; Tong, S.; Huang, J.; et al. Two B-box proteins, PavBBX6/9, positively regulate light-induced anthocyanin accumulation in sweet cherry. Plant Physiol. 2023, 192, 2030–2048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, Z.F.; Xiao, Y.Q.; Wang, Y.Y.; Sun, Y.T.; Peng, X.; Feng, C.; Zhang, X.; Du, B.Y.; Zhou, X.; Wang, C.; et al. Abscisic acid-responsive transcription factorsPavDof2/6/15 mediate fruit softening in sweet cherry. Plant Physiol. 2022, 190, 2501–2518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shastry, A.; Dunham-Snary, K. Metabolomics and mitochondrial dysfunction in cardiometabolic disease. Life Sci. 2023, 333, 122137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, P.; Qu, J.; Wang, Y.; Fang, T.; Xiao, W.; Wang, Y.L.; Zhang, Y.; Khan, M.; Chen, Q.; Xu, X.Y.; et al. Transcriptome and metabolome atlas reveals contributions of sphingosine and chlorogenic acid to cold tolerance in Citrus. Plant Physiol. 2024, 196, 634–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tian, M.J.; Sun, Y.R.; Zhang, G.D.; Xu, Y.F.; Zhu, J.; Huang, W.W.; Wang, Y.Z.; Zhang, B.C.; Li, Z.Y.; Lin, S.Y.; et al. Metabolomics navigates natural variation in pathogen-induced secondary metabolism across soybean cultivar populations. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2025, 122, e2505532122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.D.; Sun, Y.; Wen, C.X.; Jiang, T.; Tian, W.; Xie, X.L.; Cui, X.S.; Lu, R.K.; Feng, J.X.; Jin, A.H.; et al. Metabolome analysis of genus Forsythia related constituents in Forsythia suspensa leaves and fruits using UPLC-ESI-QQQ-MS/MS technique. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0269915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qi, X.L.; Liu, L.F.; Liu, C.L.; Song, L.L.; Dong, Y.X.; Chen, L.; Li, M. Sweet cherry AP2/ERF transcription factor, PavRAV2, negatively modulates fruit size by directly repressing PavKLUH expression. Physiol. Plant. 2023, 175, e14065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qi, X.L.; Liu, C.L.; Song, L.L.; Dong, Y.X.; Chen, L.; Li, M. A sweet cherry glutathione s-transferase gene, PavGST1, plays a central role in fruit skin coloration. Cells 2022, 11, 1170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, Q.D.; Shen, T.J.; Yu, R.R.; Deng, H.; Wen, X.P.; Qiao, G. Functional analysis of sweet cherry PavbHLH106 in the regulation of cold stress. Plant Cell Rep. 2023, 43, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricardo-Rodrigues, S.; Laranjo, M.; Agulheiro-Santos, A.C. Methods for quality evaluation of sweet cherry. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2023, 103, 463–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, F.L.; Qu, D.H.; Zhang, X.; Sun, Y.; Wang, J.T.; Zhu, D.Z.; Yang, L.N.; Liu, X.; Tian, W.; Wang, L.; et al. PaLectinL7 enhances salt tolerance of sweet cherry by regulating lignin deposition in connection with PaCAD1. Tree Physiol. 2023, 43, 1986–2000. [Google Scholar]

- Qi, X.L.; Dong, Y.X.; Liu, C.L.; Song, L.L.; Chen, L.; Li, M. The PavNAC56 transcription factor positively regulates fruit ripening and softening in sweet cherry (Prunus avium). Physiol. Plant 2022, 174, e13834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vega, E.N.; García-Herrera, P.; Ciudad-Mulero, M.; Dias, M.I.; Matallana-González, M.C.; Cámara, M.; Tardío, J.; Molina, M.; Pinela, J.; Pires, T.C.S.P.; et al. Wild sweet cherry, strawberry and bilberry as underestimated sources of natural colorants and bioactive compounds with functional properties. Food Chem. 2023, 414, 135669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orfanidou, C.G.; Katsiani, A.; Candresse, T.; Marais, A.; Gkremotsi, T.; Drogoudi, P.; Kazantzis, K.; Katis, N.I.; Maliogka, V.I. Identification of divergent isolates of cherry latent virus 1 in Greek sweet cherry orchards. Arch. Virol. 2023, 168, 243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Probst, C.; Pandey, B.; Swamy, P.; Grove, G. Factors affecting the infection of sweet cherry (Prunus avium) fruit by Podosphaera cerasi. Plant Dis. 2021, 105, 2873–2879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nejad, M.S.; Najafabadi, N.S.; Aghighi, S.; Zargar, M.; Bayat, M.; Pakina, E. Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles by sweet cherry and its application against cherry spot disease. Heliyon 2024, 10, e31508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.W.; Zhu, D.Z.; Liu, Q.Z.; Davis, R.E.; Zhao, Y. First report of sweet cherry virescence disease in China and its association with infection by a ‘Candidatus Phytoplasma ziziphi’-related strain. Plant Dis. 2014, 98, 419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Ning, N.N.; Ma, Y.Q.; Guo, Q.Y. Isolation and identification of the pathogen causing cherry leaf spot in Qinghai province. Plant Prot. 2020, 46, 48–55+71. [Google Scholar]

- Arndt, S.K.; Irawan, A.; Sanders, G.J. Apoplastic water fraction and rehydration techniques introduce significant errors in measurements of relative water content and osmotic potential in plant leaves. Physiol. Plant. 2015, 155, 355–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shan, G.M.; Li, X.T.; Liu, P.; Zhou, J.Y.; Wang, Y.S.; Gao, R. Morphological characteristics and cold tolerance analysis of ground cover chrysanthemums Yannong Guiyou’ × ‘Yannong Maohua’ and their hybrids. North. Hortic. 2025, 1–10. Available online: https://link.cnki.net/urlid/23.1247.s.20251125.1031.002 (accessed on 30 November 2025).

- Yuan, H.R.; Cheng, M.X.; Wang, R.H.; Wang, Z.K.; Fan, F.F.; Wang, W.; Si, F.F.; Gao, F.; Li, S.Q. miR396b/GRF6 module contributes to salt tolerance in rice. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2024, 22, 2079–2092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.H.; Zhang, R.P.; Song, Y.M.; He, J.M.; Sun, J.H.; Bai, J.F.; An, Z.L.; Dong, L.J.; Zhan, Q.M.; Abliz, Z. RRLC-MS/MS-based metabonomics combined with in-depth analysis of metabolic correlation network: Finding potential biomarkers for breast cancer. Analyst 2009, 134, 2003–2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hulin, M.T.; Vadillo, D.A.; Cossu, F.; Lynn, S.; Russell, K.; Neale, H.C.; Jackson, R.W.; Arnold, D.L.; Mansfield, J.W.; Harrison, R.J. Identifying resistance in wild and ornamental cherry towards bacterial canker caused by Pseudomonas syringae. Plant Pathol. 2022, 71, 949–965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, N.; Li, Q.; Xu, Q.; Liu, J.; Huang, F.; Zhan, Z.X.; Qin, P.; Zhou, X.P.; Yu, W.L.; Zhang, C.Y. CRb and PbBa8.1 synergically increases resistant genes expression upon infection of Plasmodiophora brassicae in Brassica napus. Genes 2020, 11, 202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, D.; Yang, D.Y.; Li, T.; Zhu, Z.; Yan, B.X.; He, Y.; Li, X.Y.; Zhai, K.R.; Liu, J.Y.; Kawano, Y. A PRA-Rab trafficking machinery modulates NLR immune receptor plasma membrane microdomain anchoring and blast resistance in rice. Sci. Bull. 2025, 70, 733–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.B.; Luo, W.D.; Xie, H.T.; Mo, C.P.; Qin, B.X.; Zhao, Y.G.; Chen, X.; Zhang, S.B.; Zhao, Y.L.; Wang, M.C. Reovirus infection results in rice rhizosphere microbial community reassembly through metabolite-mediated recruitment and exclusion. Microbiome 2025, 13, 214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pan, L.Y.; Zhou, J.; Sun, Y.; Qiao, B.X.; Wan, T.; Guo, R.Q.; Zhang, J.; Shan, D.Q.; Cai, Y.L. Comparative transcriptome and metabolome analyses of cherry leaves spot disease caused by Alternaria alternata. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1129515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.J.; Dong, W.K.; Zhao, C.X.; Ma, H.L. Comparative transcriptome analysis of resistant and susceptible Kentucky bluegrass varieties in response to powdery mildew infection. BMC Plant Biol. 2022, 22, 509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Tang, J.; Wei, K.; Jia, S.G.; Jiang, Y.W.; Cai, H.W.; Mao, P.S.; Li, M.L. Physiological and molecular responses of Zoysia japonica to rust infection. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 4185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, X.X.; Chen, Z.D.; Xia, Y.Q.; Wang, L.; Sun, Y.J.; Zhang, M.M.; Xiao, Y.; Han, Z.F.; et al. Plant receptor-like protein activation by a microbial glycoside hydrolase. Nature 2022, 610, 335–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Z.C.; Song, T.Q.; Zhu, L.; Ye, W.W.; Wang, Y.; Shao, Y.Y.; Dong, S.M.; Zhang, Z.G.; Dou, D.L.; Zheng, X.B.; et al. A Phytophthora sojae glycoside hydrolase 12 protein is a major virulence factor during soybean infection and is recognized as a PAMP. Plant Cell 2015, 27, 2057–2072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prautsch, J.; Erickson, J.L.; Özyürek, S.; Gormanns, R.; Franke, L.; Lu, Y.; Marx, J.; Niemeyer, F.; Parker, J.E.; Stuttmann, J.; et al. Effector XopQ-induced stromule formation in Nicotiana benthamiana depends on ETI signaling components ADR1 and NRG1. Plant Physiol. 2023, 191, 161–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, K.Y.; Yang, B.; Tian, D.S.; Wu, L.F.; Wang, D.J.; Sreekala, C.; Yang, F.; Chu, Z.Q.; Wang, G.L.; White, F.F.; et al. R gene expression induced by a type-III effector triggers disease resistance in rice. Nature 2005, 435, 1122–1125. [Google Scholar]

- Nie, X.H.; Zhao, S.Q.; Hao, Y.Q.; Gu, S.; Zhang, Y.; Qi, B.X.; Xing, Y.; Qin, L. Transcriptome analysis reveals key genes involved in the resistance to Cryphonectria parasitica during early disease development in Chinese chestnut. BMC Plant Biol. 2023, 23, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.H.; Qiu, L.N.; Liu, X.Y.; Zhang, Q.; Zhuansun, X.X.; Fahima, T.; Krugman, T.; Sun, Q.X.; Xie, C.J. Glycerol-induced powdery mildew resistance in wheat by regulating plant fatty acid Metabolism, plant hormones cross-talk, and pathogenesis-related genes. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, M.R.; Qi, X.; Li, D.; Wu, Z.Q.; Liu, M.Y.; Yang, W.G.; Zang, Z.Y.; Jiang, L.Y. Comparative transcriptome analysis highlights resistance regulatory networks of maize in response to Exserohilum turcicum infection at the early stage. Physiol. Plant. 2024, 176, e14615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.T.; Hu, X.Q.; Wang, P.; Gao, L.Y.; Pei, Y.K.; Ge, Z.Y.; Ge, X.Y.; Li, F.G.; Hou, Y.X. GhPLP2 positively regulates cotton resistance to Verticillium Wilt by modulating fatty acid accumulation and jasmonic acid signaling pathway. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 749630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rathod, V.; Rathod, K.; Tomar, R.S.; Tatamiya, R.; Hamid, R.; Jacob, F.; Munshi, N.S. Metabolic profiles of peanut (Arachis hypogaea L.) in response to Puccinia arachidis fungal infection. BMC Genom. 2023, 24, 630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuchs, D.; Tang, X.; Johnsson, A.K.; Dahlén, S.E.; Hamberg, M.; Wheelock, C.E. Eosinophils synthesize trihydroxyoctadecenoic acids (TriHOMEs) via a 15-lipoxygenase dependent process. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Cell Biol. Lipids 2020, 1865, 158611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kato, T.; Hirukawa, T.; Yano, M. Synthesis of (E)-9,10,13-Trihydroxy-11-octadecenoic Acids. Bull. Chem. Soc. Jpn. 1994, 67, 839–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.D.; Liu, J.L.; Triplett, L.; Leach, J.E.; Wang, G.L. Novel insights into rice innate immunity against bacterial and fungal pathogens. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 2014, 52, 213–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miura, A.; Kuwahara, S. A concise synthesis of pinellic acid using a cross-metathesis approach. Tetrahedron 2009, 65, 3364–3368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yuan, H.; Gao, H.; Duan, S.; Zhou, X.; Yang, X.; Sun, B.; Ren, H.; Zheng, Z.; Guo, Q. Metabolomics Reveals Resistance-Related Secondary Metabolism in Sweet Cherry Infected by Alternaria alternata. Biomolecules 2025, 15, 1730. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom15121730

Yuan H, Gao H, Duan S, Zhou X, Yang X, Sun B, Ren H, Zheng Z, Guo Q. Metabolomics Reveals Resistance-Related Secondary Metabolism in Sweet Cherry Infected by Alternaria alternata. Biomolecules. 2025; 15(12):1730. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom15121730

Chicago/Turabian StyleYuan, Huaning, Hanfeng Gao, Shupeng Duan, Xiaoyu Zhou, Xiuru Yang, Bo Sun, Hongwei Ren, Zhenzhen Zheng, and Qingyun Guo. 2025. "Metabolomics Reveals Resistance-Related Secondary Metabolism in Sweet Cherry Infected by Alternaria alternata" Biomolecules 15, no. 12: 1730. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom15121730

APA StyleYuan, H., Gao, H., Duan, S., Zhou, X., Yang, X., Sun, B., Ren, H., Zheng, Z., & Guo, Q. (2025). Metabolomics Reveals Resistance-Related Secondary Metabolism in Sweet Cherry Infected by Alternaria alternata. Biomolecules, 15(12), 1730. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom15121730