Isolation and Characterization of a Biocontrol Serine Protease from Pseudomonas aeruginosa FZM498 Involved in Antagonistic Activity Against Blastocystis sp. Parasite

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample Processing and Isolation of Fecal Bacteria and Parasites

2.2. Qualitative Protease Detection and Production

2.3. Quantitative Assay of Protease Activity

2.4. Identification of Bacteria and Parasites

2.5. Purification of Bacterial Protease

2.6. Effect of Temperature on Protease Activity and Stability

2.7. Effect of pH on Enzymatic Activity and Stability

2.8. Effect of Cations

2.9. Inhibition Study

2.10. Determination of Kinetic Parameters

2.11. Amidolytic Activity

2.12. Anti-Blastocystis Activity of Bacterial Protease

2.12.1. Light Microscopy

2.12.2. Scanning Electron Microscopy

2.13. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Isolation and Identification of Fecal Bacteria and Parasites

3.2. Purification of Selected Protease

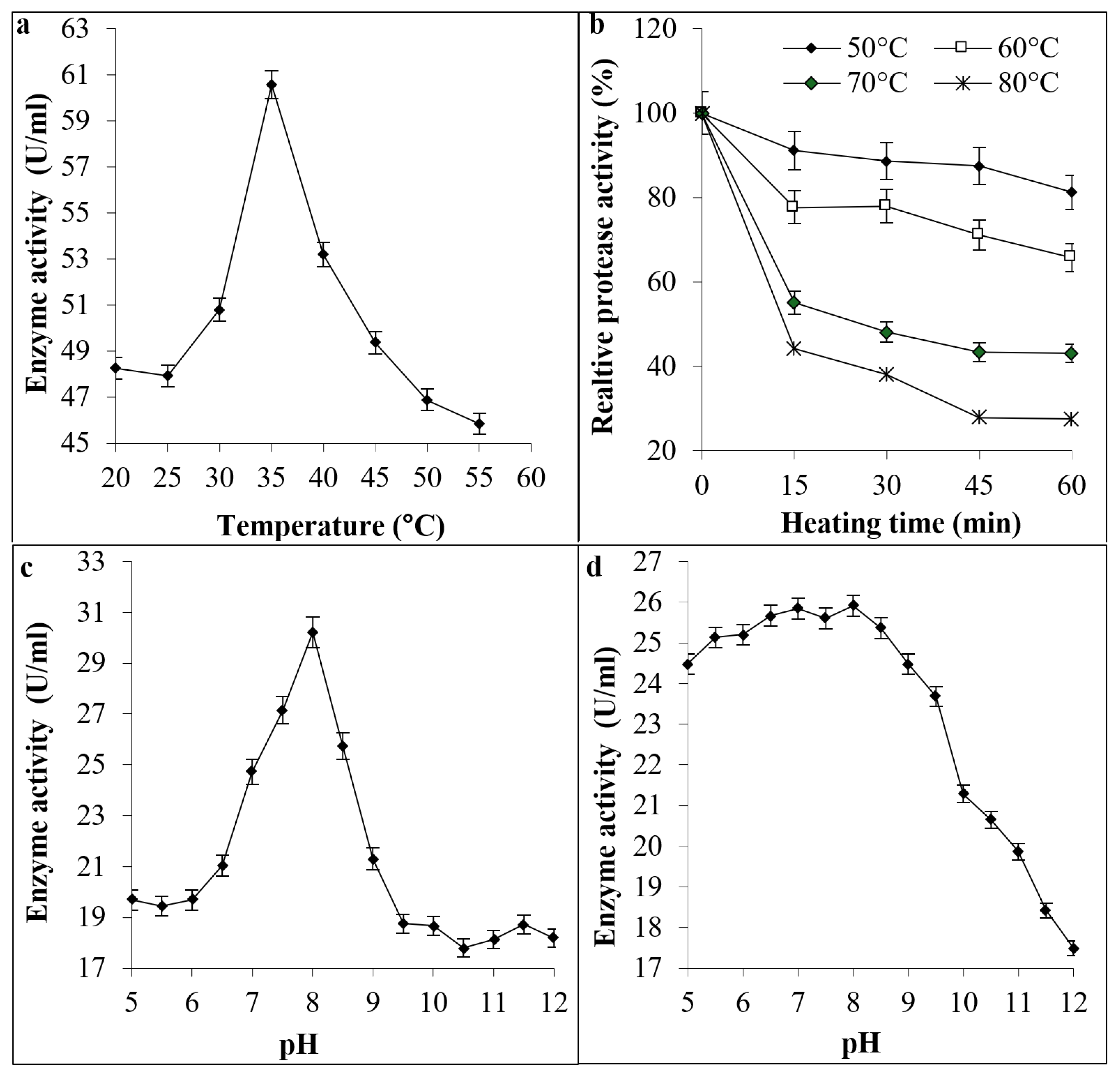

3.3. Effect of Temperature and pH on Protease Activity and Stability

3.4. Effect of Metallic Ions

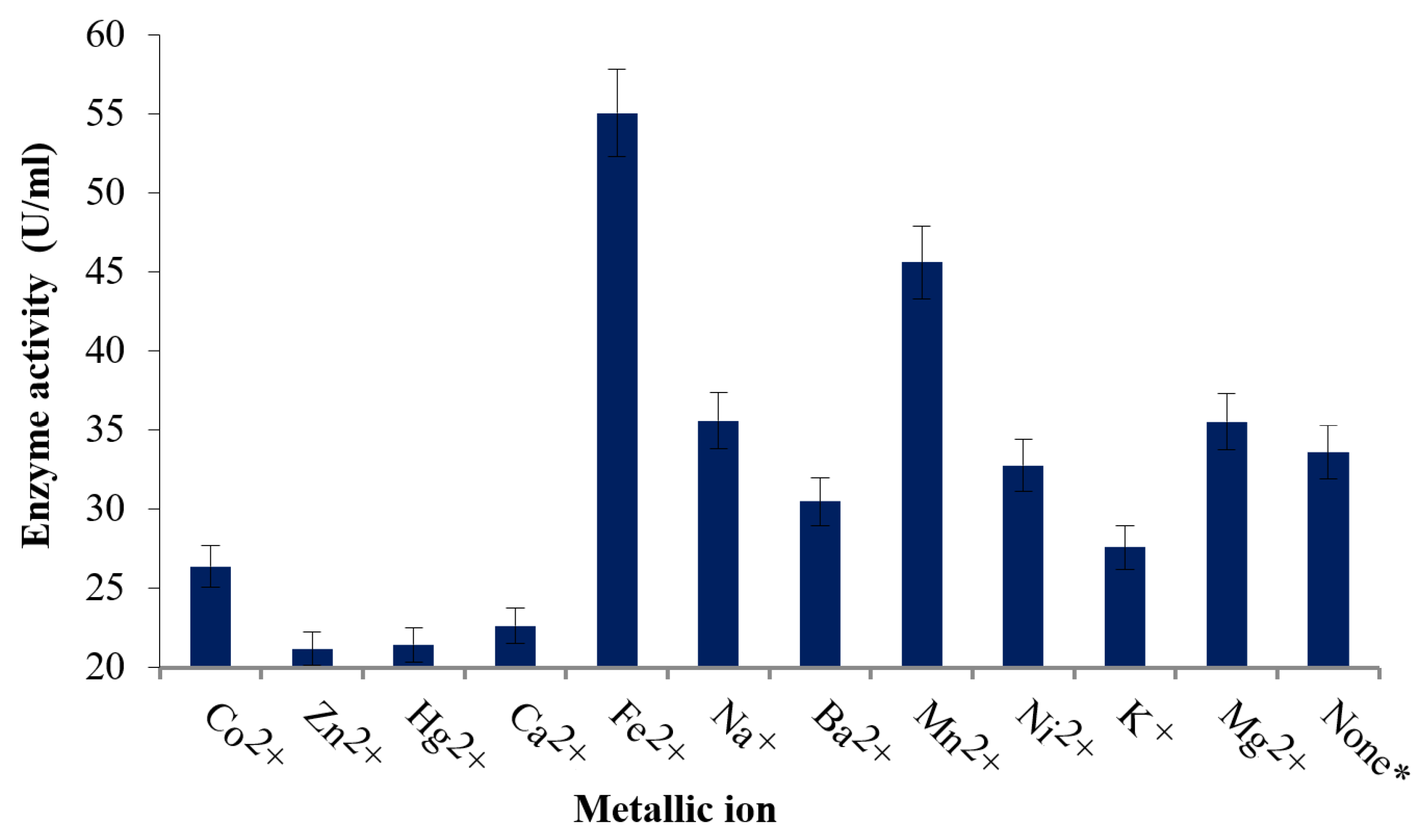

3.5. Effect of Protease Inhibitors

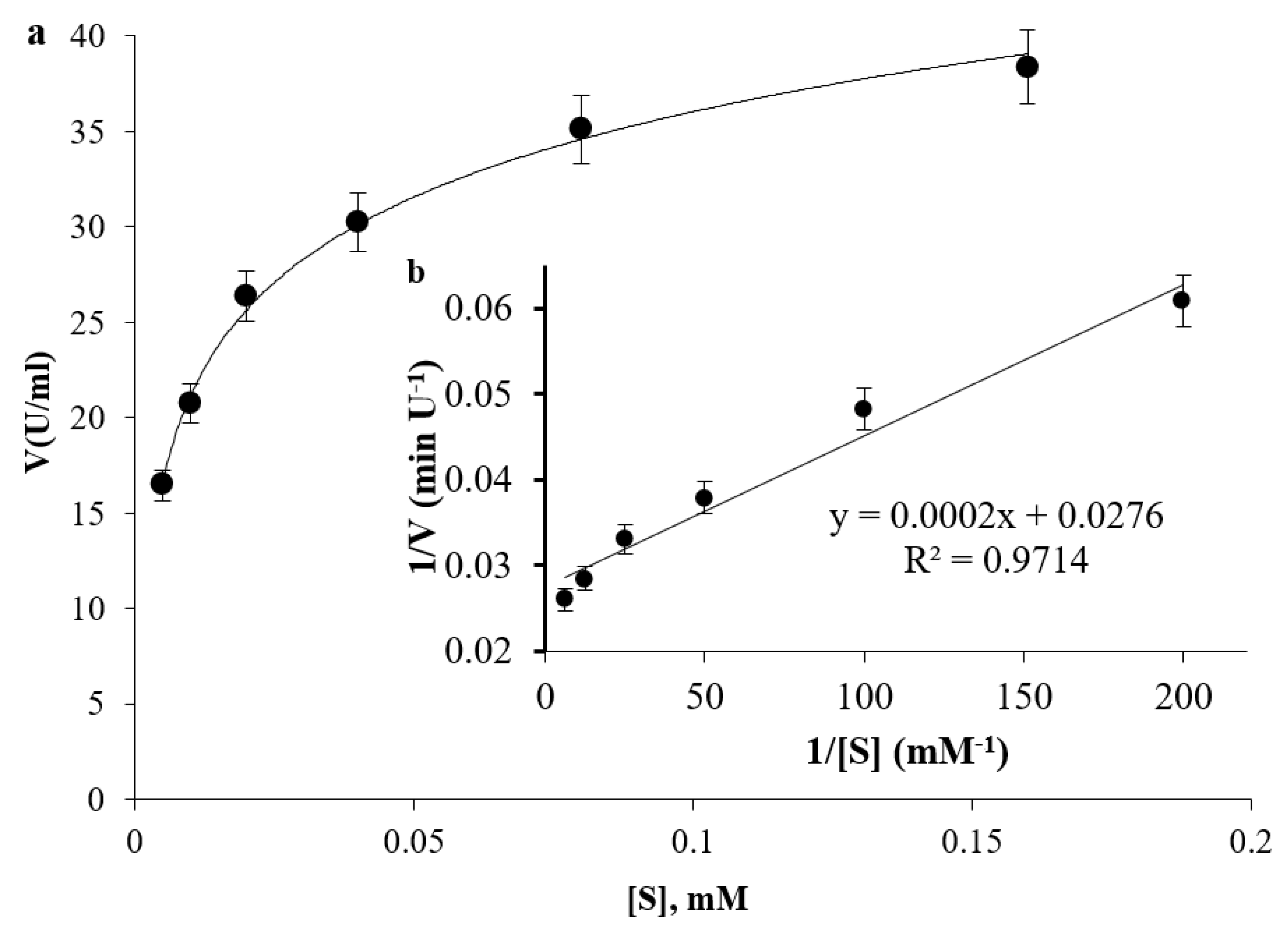

3.6. Enzyme Dynamics

3.7. Substrate Specificity

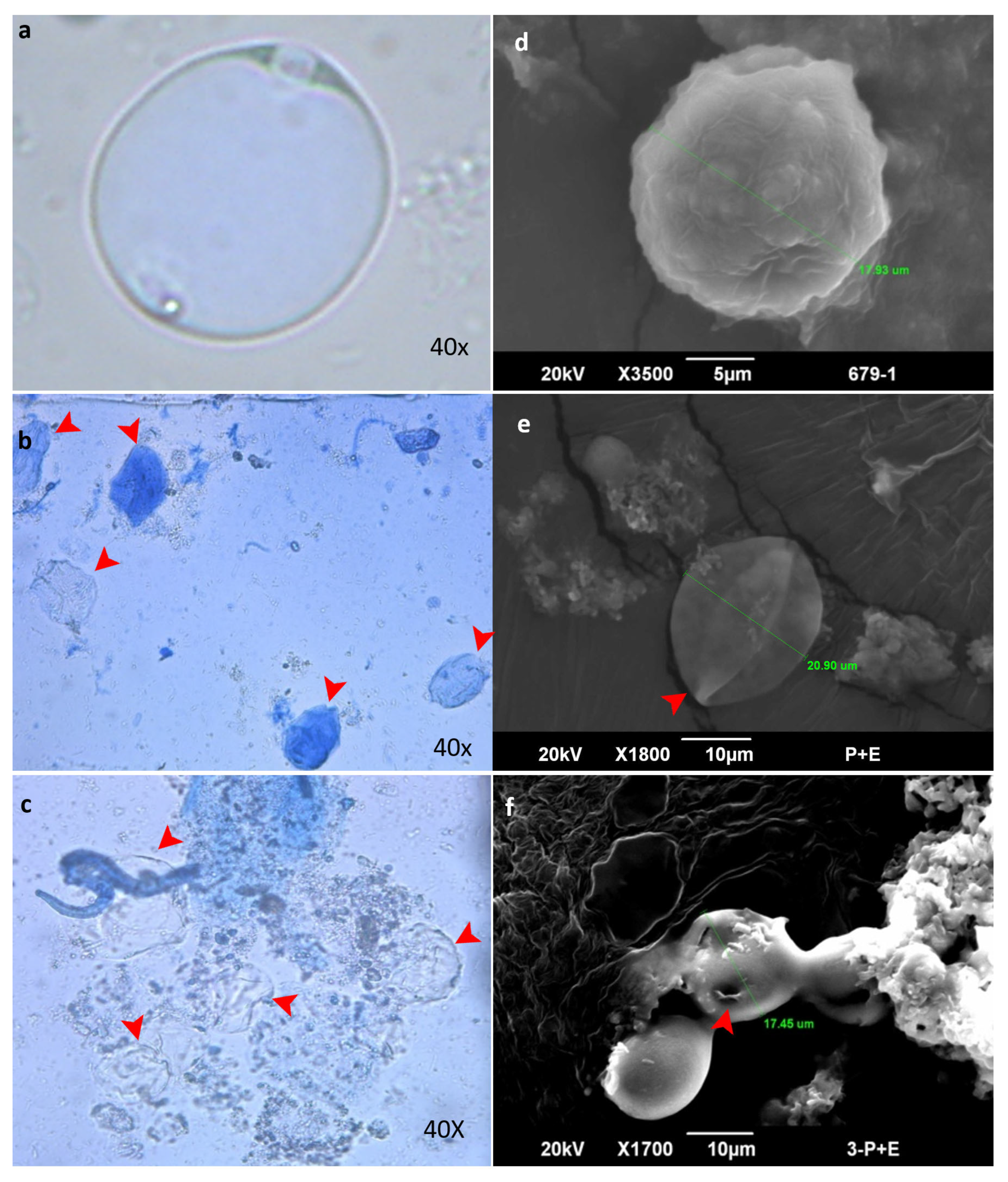

3.8. In Vitro Anti-Blastocystis Activity of Bacterial Protease

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| DMSO | Dimethyl sulfoxide |

| 1,4-DTT | 1,4-dithiothreitol |

| EDTA | Ethylenediamine-tetraacetate |

| HMDS | Hexamethyldisilazane |

| IMDM | Iscove’s modified Dulbecco’s medium |

| Kcat | Catalytic rate constant |

| Km | Michaelis–Menten constant |

| LB plot | Lineweaver–Burk plot |

| PBS | Phosphate-buffered saline |

| PMSF | Phenylmethyl sulfonyl fluoride |

| pNA | p-nitroaniline |

| SBTI | Soybean trypsin inhibitor |

| SDS-PAGE | Sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis |

| T1/2 | Half-life time |

| TCA | Trichloroacetic acid |

| TLCK | Tosyl-L-lysyl-chloromethane hydrochloride |

| Vmax | Maximum velocity of reaction |

References

- Deng, L.; Wojciech, L.; Gascoigne, N.R.; Peng, G.; Tan, K.S. New insights into the interactions between Blastocystis, the gut microbiota, and host immunity. PLoS Pathog. 2021, 17, e1009253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coyle, C.M.; Varughese, J.; Weiss, L.M.; Tanowitz, H.B. Blastocystis: To treat or not to treat. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2012, 54, 105–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lappan, R.; Classon, C.; Kumar, S.; Singh, O.P.; De Almeida, R.V.; Chakravarty, J.; Kumari, P.; Kansal, S.; Sundar, S.; Blackwell, J.M. Meta-taxonomic analysis of prokaryotic and eukaryotic gut flora in stool samples from visceral leishmaniasis cases and endemic controls in Bihar State India. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2019, 13, e0007444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tito, R.Y.; Chaffron, S.; Caenepeel, C.; Lima-Mendez, G.; Wang, J.; Vieira-Silva, S.; Falony, G.; Hildebrand, F.; Darzi, Y.; Rymenans, L.; et al. Population-level analysis of Blastocystis subtype prevalence and variation in the human gut microbiota. Gut 2019, 68, 1180–1189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lukeš, J.; Stensvold, C.R.; Jirků-Pomajbíková, K.; Wegener Parfrey, L. Are human intestinal eukaryotes beneficial or commensals? PLoS Pathog. 2015, 11, e1005039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nourrisson, C.; Scanzi, J.; Pereira, B.; NkoudMongo, C.; Wawrzyniak, I.; Cian, A.; Viscogliosi, E.; Livrelli, V.; Delbac, F.; Dapoigny, M.; et al. Blastocystis is associated with decrease of fecal microbiota protective bacteria: Comparative analysis between patients with irritable bowel syndrome and control subjects. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e111868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, M.S., II; Ganac, R.D.; Hiser, G.; Hudson, N.R.; Le, A.; Whipps, C.M. Detection of Blastocystis from stool samples using real-time PCR. Parasitol. Res. 2008, 103, 551–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stensvold, C.R.; van der Giezen, M. Associations between gut microbiota and common luminal intestinal parasites. Trends Parasitol. 2018, 34, 369–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rawlings, N.D.; Salvesen, G. Handbook of Proteolytic Enzymes; Academic Press: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Casadevall, A.; Pirofski, L.A. Host-pathogen interactions: Basic concepts of microbial commensalism, colonization, infection, and disease. Infect. Immun. 2000, 68, 6511–6518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karamati, S.A.; Mirjalali, H.; Niyyati, M.; Yadegar, A.; Asadzadeh Aghdaei, H.; Haghighi, A.; Seyyed Tabaei, S.J. Association of Blastocystis ST6 with higher protease activity among symptomatic subjects. BMC Microbiol. 2021, 21, 285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clark, C.G. Extensive genetic diversity in Blastocystis hominis. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 1997, 87, 79–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uddin, M.N.; Akter, Y.; Chowdhury, M.A.B.; Shimizu, K.; Marzan, L.W. Exploring alkaline serine protease production and characterization in proteolytic bacteria Stenotrophomonas maltophilia: Insights from real-time PCR and fermentation techniques. Biocatal. Agric. Biotechnol. 2024, 58, 103186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coêlho, D.F.; Saturnino, T.P.; Fernandes, F.F.; Mazzola, P.G.; Silveira, E.; Tambourgi, E.B. Azocasein substrate for determination of proteolytic activity: Reexamining a traditional method using bromelain samples. BioMed Res. Int. 2016, 2016, 8409183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stensvold, C.R. Comparison of sequencing (barcode region) and sequence-tagged-site PCR for Blastocystis subtyping. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2013, 51, 190–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scicluna, S.M.; Tawari, B.; Clark, C.G. DNA barcoding of Blastocystis. Protist 2006, 157, 77–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beg, Q.K.; Gupta, R. Purification and characterization of an oxidant-stable, thiol-dependent serine alkaline protease from Bacillus mojavensis. Enzyme Microb. Technol. 2003, 32, 294–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razzaq, A.; Shamsi, S.; Ali, A.; Ali, Q.; Sajjad, M.; Malik, A.; Ashraf, M. Microbial proteases applications. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2019, 7, 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghafoori, H.; Askari, M.; Sarikhan, S. Purification and characterization of an extracellular haloalkaline serine protease from the moderately halophilic bacterium, Bacillus iranensis (X5B). Extremophiles 2016, 20, 115–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jermy, B.R.; Al-Jindan, R.Y.; Ravinayagam, V.; El-Badry, A.A. Anti-blastocystosis activity of antioxidant coated ZIF-8 combined with mesoporous silicas MCM-41 and KIT-6. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 6403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Zhang, S.; Qiao, J.; Wu, X.; Zhao, L.; Liu, Y.; Fan, X. Ultrastructural insights into morphology and reproductive mode of Blastocystis hominis. Parasitol. Res. 2012, 110, 1165–1172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajaei, Z.; Farahani, A.; Turki, H.; Shoja, S.; Ghanbarnejad, A.; Kamali, H.; Shamseddin, J. Molecular epidemiology of Blastocystis spp. isolates in Bandar Abbas, South of Iran. Iran. J. Med. Microbiol. 2023, 17, 441–446. [Google Scholar]

- Matovelle, C.; Tejedor, M.T.; Monteagudo, L.V.; Beltrán, A.; Quílez, J. Prevalence and associated factors of Blastocystis sp. infection in patients with gastrointestinal symptoms in Spain: A case-control study. Trop. Med. Infect. Dis. 2022, 7, 226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanetti, A.D.S.; Malheiros, A.F.; De Matos, T.A.; Longhi, F.G.; Moreira, L.M.; Silva, S.L.; Castrillon, S.K.I.; Ferreira, S.M.B.; Ignotti, E.; Espinosa, O.A. Prevalence of Blastocystis sp. infection in several hosts in Brazil: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Parasites Vectors 2020, 13, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shakra, M.Y.; Abu-Sheishaa, G.A.; Hafez, A.O.; El-Lessy, F.M. Molecular assay and in vitro culture for Blastocystis prevalence in Dakahlia governorate, Egypt. Egypt. J. Immunol. 2023, 30, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scanlan, P.D.; Stensvold, C.R.; Rajilić-Stojanović, M.; Heilig, H.G.; De Vos, W.M.; O’Toole, P.W.; Cotter, P.D. The microbial eukaryote Blastocystis is a prevalent and diverse member of the healthy human gut microbiota. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2014, 90, 326–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kasana, R.C.; Salwan, R.; Yadav, S.K. Microbial proteases: Detection, production, and genetic improvement. Crit. Rev. Microbiol. 2011, 37, 262–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marzouki, M.N.; Essghaier, B.; Omrane, I.; Kamoun, A.S.; Nasri, M. Purification and characterization of an alkaline protease Prot 1 from Botrytis cinerea: Biodetergent catalyst assay. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2007, 141, 361–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akkaya, S.N.; Almansour, A.; Altintas, R.; Sisecioglu, M.; Adiguzel, A. Purification, characterization, optimization, and docking simulation of alkaline protease produced by Brevibacillus agri SAR25 using fish wastes as a substrate. Food Chem. 2025, 471, 142816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahmoud, A.; Kotb, E.; Alqosaibi, A.I.; Al-Karmalawy, A.A.; Al-Dhuayan, I.S.; Alabkari, H. In vitro and in silico characterization of alkaline serine protease from Bacillus subtilis D9 recovered from Saudi Arabia. Heliyon 2021, 7, e08148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fahmy, N.M.; El-Deeb, B. Optimization, partial purification, and characterization of a novel high molecular weight alkaline protease produced by Halobacillus sp. HAL1 using fish wastes as a substrate. J. Genet. Eng. Biotechnol. 2023, 21, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, Y.; Qiang, J.; Zhou, G.; Zhang, X.; Wang, L.; Shi, Y. Characterization of redox and salinity-tolerant alkaline protease from Bacillus halotolerans strain DS5. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 935072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obichi, E.A.; Ezebuiro, V. Effects of temperature and pH on the stability of protease produced by Alcaligenes faecalis P2. J. Appl. Life Sci. Int. 2021, 24, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zambare, V.; Nilegaonkar, S.; Kanekar, P. A novel extracellular protease from Pseudomonas aeruginosa MCM B-327: Enzyme production and its partial characterization. New Biotechnol. 2011, 28, 173–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mushtaq, H.; Jehangir, A.; Ganai, S.A.; Farooq, S.; Ganai, B.A.; Nazir, R. Biochemical characterization and functional analysis of heat stable high potential protease of Bacillus amyloliquefaciens strain HM48 from soils of Dachigam National Park in Kashmir Himalaya. Biomolecules 2021, 11, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karray, A.; Alonazi, M.; Horchani, H.; Ben Bacha, A. A novel thermostable and alkaline protease produced from Bacillus stearothermophilus isolated from olive oil mill sols suitable to industrial biotechnology. Molecules 2021, 26, 1139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adinarayana, K.; Ellaiah, P.; Prasad, D.S. Purification and partial characterization of thermostable serine alkaline protease from a newly isolated Bacillus subtilis PE-11. AAPS PharmSciTech 2003, 4, 440–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hakim, A.; Bhuiyan, F.R.; Iqbal, A.; Emon, T.H.; Ahmed, J.; Azad, A.K. Production and partial characterization of dehairing alkaline protease from Bacillus subtilis AKAL7 and Exiguobacterium indicum AKAL11 by using organic municipal solid wastes. Heliyon 2018, 4, e00646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regode, V.; Kuruba, S.; Mohammad, A.S.; Sharma, H.C. Isolation and characterization of gut bacterial proteases involved in inducing pathogenicity of Bacillus thuringiensis toxin in cotton bollworm, Helicoverpa armigera. Front. Microbiol. 2016, 7, 1567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, R.; Beg, Q.; Lorenz, P. Bacterial alkaline proteases: Molecular approaches and industrial applications. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2002, 59, 15–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jellouli, K.; Bougatef, A.; Manni, L.; Agrebi, R.; Siala, R.; Younes, I.; Nasri, M. Molecular and biochemical characterization of an extracellular serine-protease from Vibrio metschnikovii J1. J. Ind. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2009, 36, 939–948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotb, E. Purification and partial characterization of a chymotrypsin-like serine fibrinolytic enzyme from Bacillus amyloliquefaciens FCF-11 using corn husk as a novel substrate. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2014, 30, 2071–2080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nagel, R.; Gray, C.; Bielefeldt-Ohmann, H.; Traub, R.J. Features of Blastocystis spp. in xenic culture revealed by deconvolutional microscopy. Parasitology 2015, 142, 3237–3245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mokhtar, A.B.; Ahmed, S.A.; Eltamany, E.E.; Karanis, P. Anti-Blastocystis activity in vitro of Egyptian herbal extracts (family: Asteraceae) with emphasis on Artemisia judaica. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 1555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AlKhalaf, E.; Alabdurahman, G.; Assany, Y.; El-Badry, A. Anti-Blastocystis in vitro activity and in vivo efficacy of the ethanol extracts of Origanum syriacum L. and Ceratonia siliqua. Parasitol. United J. 2023, 16, 73–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ezz El Dine, S.I.M.; Al-Antably, A.S.A.E.G.; El Bahy, M.M.; El Akad, D.M.H.; Rizk, E. In-vitro study on the effect of chitosan, and chitosan nanoparticles on the viability and ultrastructure of Blastocystis species. J. Egypt. Soc. Parasitol. 2024, 54, 283–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Protease Reagent | Standard Concentration (mM) | Enzyme Activity (A405) | Relative Activity (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| PMSF | 5.00 | 0.033 | 9.218 |

| PMSF | 2.00 | 0.034 | 9.497 |

| TLCK | 0.50 | 0.125 | 34.916 |

| Aprotinin | 0.05 | 0.236 | 65.922 |

| SBTI | 0.05 | 0.168 | 46.927 |

| Benzamidine | 1.00 | 0.254 | 70.950 |

| EDTA | 10.00 | 0.477 | 133.240 |

| 1,10-phenanthroline | 0.10 | 0.536 | 149.721 |

| 2,2-bipyridine | 0.10 | 0.509 | 142.179 |

| 1,4-DTT | 50.00 | 0.198 | 55.307 |

| 1,4-DTT | 10.00 | 0.254 | 70.950 |

| Pepstatin A | 0.05 | 0.473 | 132.123 |

| Pepstatin A | 0.02 | 0.382 | 106.704 |

| Leupeptin | 0.05 | 0.500 | 139.665 |

| Leupeptin | 0.02 | 0.354 | 98.883 |

| 2-mercaptoethanol | 50.00 | 0.240 | 67.039 |

| 2-mercaptoethanol | 10.00 | 0.341 | 95.251 |

| E-64 | 1.50 | 0.353 | 98.603 |

| None * | NA | 0.358 | 100.000 |

| Concentration (mM) | D-Val-Leu-Arg-P-Nitroanilide (S-6258) | D-Ile-Pro-Arg-AMC (S-2288) | N-Succinyl-Ala-Ala-Pro-Phe-P-Nitroanilide (S-7388) | D-Val-Leu-Lys-P-Nitroanilide Dihydrochloride (S-7127) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.200 | 0.689 | 0.730 | 0.787 | 0.796 |

| 0.100 | 0.745 | 0.715 | 0.733 | 0.754 |

| 0.050 | 0.671 | 0.662 | 0.694 | 0.729 |

| 0.025 | 0.575 | 0.567 | 0.567 | 0.674 |

| 0.000 | 0.362 | 0.362 | 0.362 | 0.362 |

| Classification | For Kallikrein | For tissue plasminogen-activator (tPA) | For subtilisin and chymotrypsin | For plasmin |

| Vmax | 66.23 | 61.73 | 66.67 | 64.10 |

| Km | 0.013245 | 0.00617 | 0.01333 | 0.005128 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Almilad, F.Z.; Kotb, E.; Baghdadi, H.B.; Hosin, N.; Alsaif, H.A.; El-Badry, A.A. Isolation and Characterization of a Biocontrol Serine Protease from Pseudomonas aeruginosa FZM498 Involved in Antagonistic Activity Against Blastocystis sp. Parasite. Biomolecules 2026, 16, 82. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom16010082

Almilad FZ, Kotb E, Baghdadi HB, Hosin N, Alsaif HA, El-Badry AA. Isolation and Characterization of a Biocontrol Serine Protease from Pseudomonas aeruginosa FZM498 Involved in Antagonistic Activity Against Blastocystis sp. Parasite. Biomolecules. 2026; 16(1):82. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom16010082

Chicago/Turabian StyleAlmilad, Fatimah Z., Essam Kotb, Hanadi B. Baghdadi, Nehal Hosin, Hawra A. Alsaif, and Ayman A. El-Badry. 2026. "Isolation and Characterization of a Biocontrol Serine Protease from Pseudomonas aeruginosa FZM498 Involved in Antagonistic Activity Against Blastocystis sp. Parasite" Biomolecules 16, no. 1: 82. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom16010082

APA StyleAlmilad, F. Z., Kotb, E., Baghdadi, H. B., Hosin, N., Alsaif, H. A., & El-Badry, A. A. (2026). Isolation and Characterization of a Biocontrol Serine Protease from Pseudomonas aeruginosa FZM498 Involved in Antagonistic Activity Against Blastocystis sp. Parasite. Biomolecules, 16(1), 82. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom16010082