Telomere-to-Telomere Genome Assembly of Two Hemiculter Species Provide Insights into the Genomic and Morphometric Bases of Adaptation to Flow Velocity

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

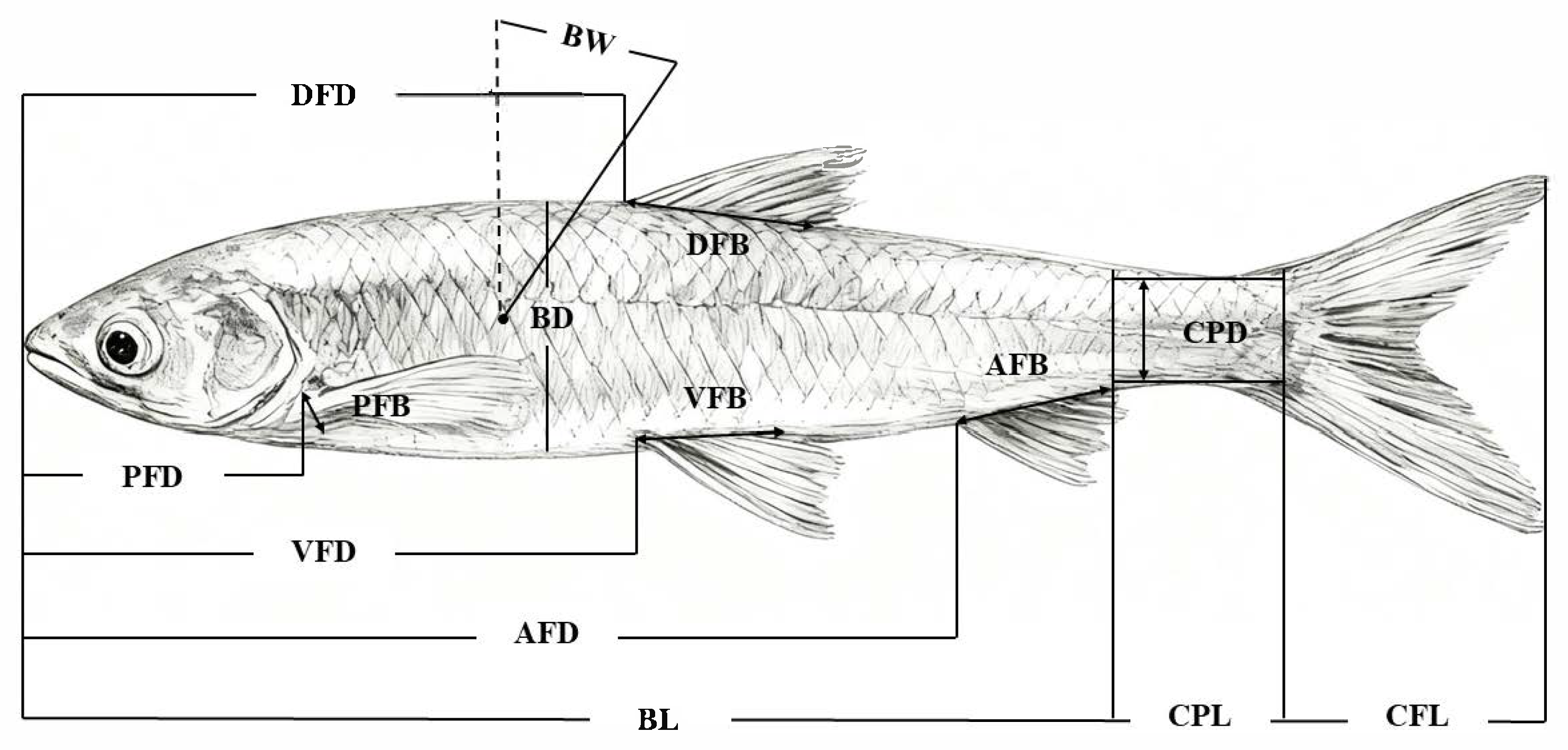

2.1. Morphometrics

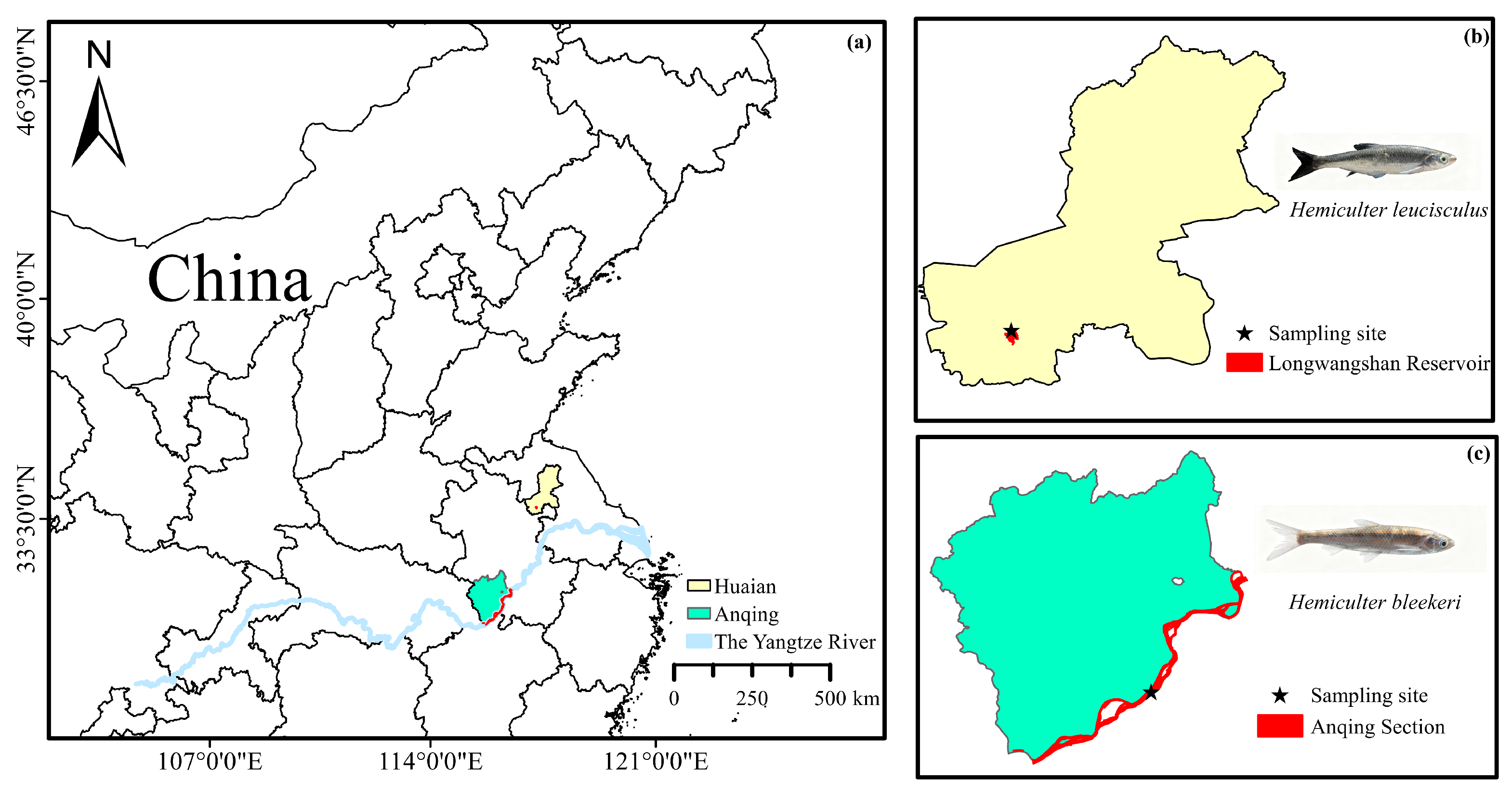

2.2. Sample Collection for Genome Sequencing

2.3. Library Construction and Genome Sequencing

2.4. T2T Genome Assembling and Quality Assessment

2.5. Repetitive Sequences Annotation, Gene Prediction and Functional Annotation

2.6. Phylogenetic Analysis, Estimation of Divergence Time and Collinearity Analysis

2.7. Gene Family Contraction and Expansion

3. Results

3.1. Morphometric Measurements

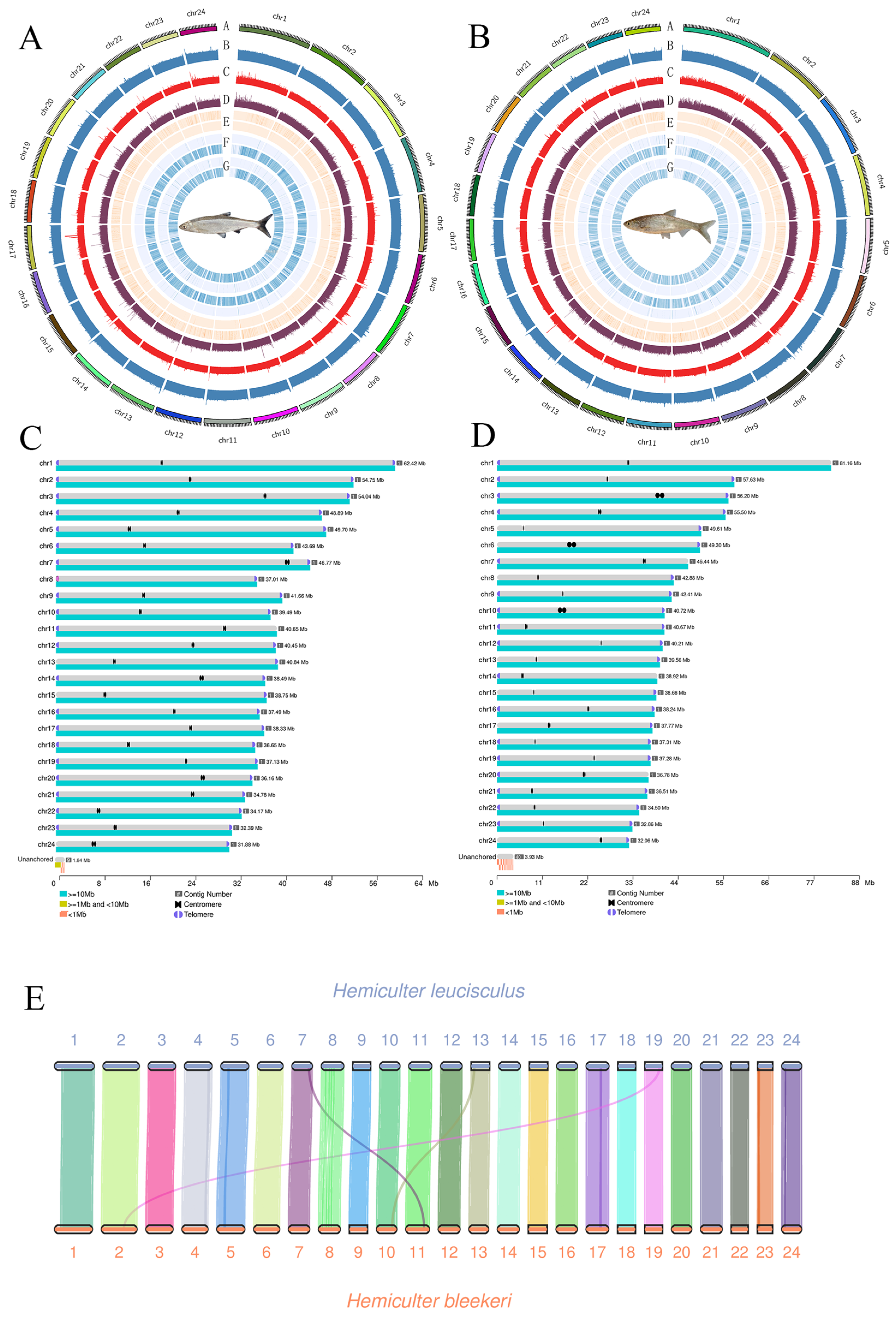

3.2. Genome Sequencing and T2T Gap-Free Assembly

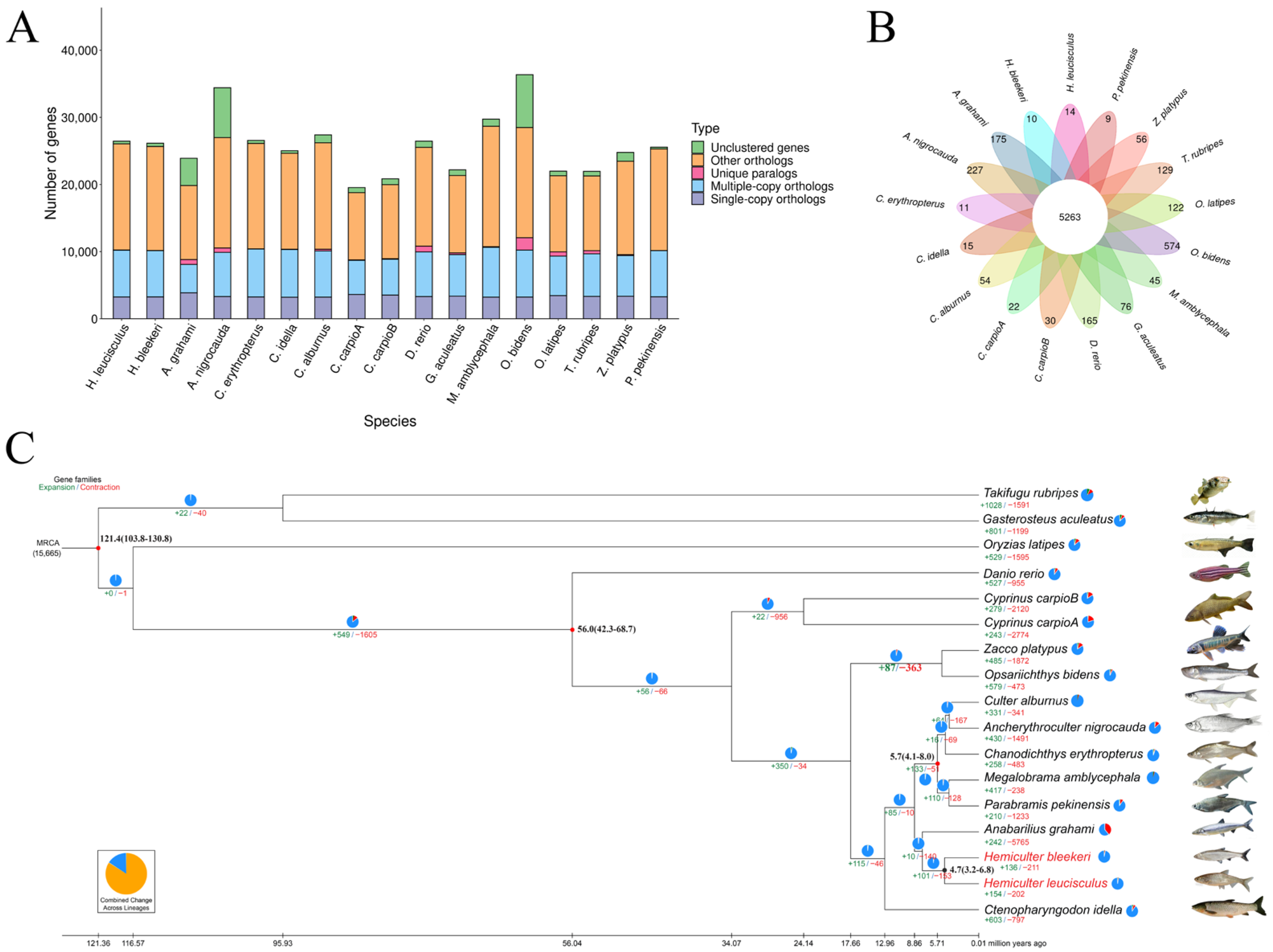

3.3. Gene Prediction and Annotation

3.4. Collinearity Analysis of H. bleekeri and H. leucisculus

3.5. Gene Family Clustering and Phylogenetic Analysis

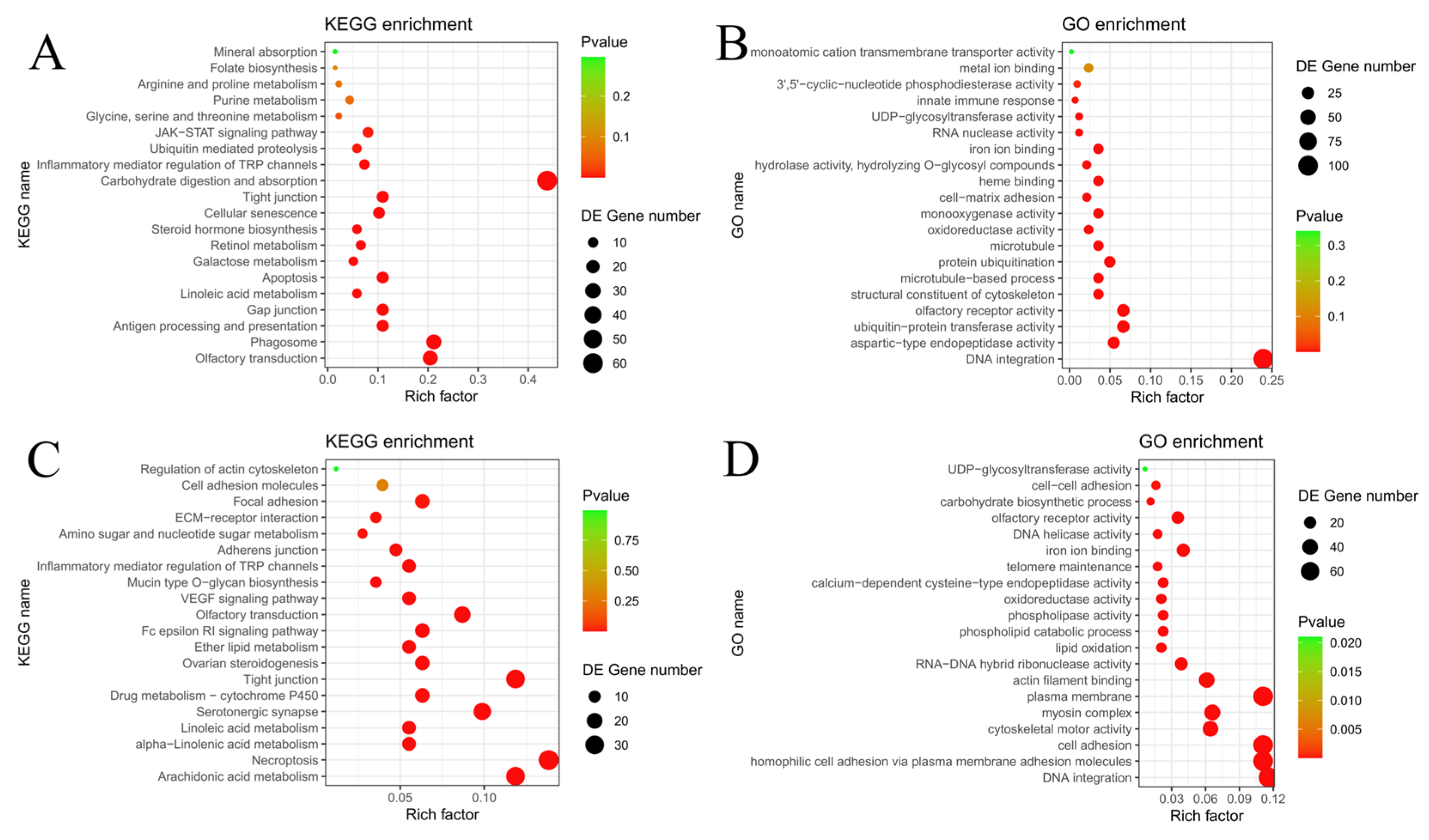

3.6. Comparative Genomic Analysis Underlying Morphological Divergence

3.7. Comparative Genomic Analysis Underlying Reproductive Strategies

4. Discussion

4.1. Genome Assembly Quality

4.2. Genome Annotation Characteristics

4.3. Comparative Genomics Provides Insights into Adaptation to Flow Velocity

4.4. Potential Factors Beyond Flow Velocity

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gatz, A.J., Jr.; Sale, M.J.; Loar, J.M. Habitat shifts in rainbow trout: Competitive influences of brown trout. Oecologia 1987, 74, 7–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morantz, D.L.; Sweeney, R.K.; Shirvell, C.S.; Longard, D.A. Selection of Microhabitat in Summer by Juvenile Atlantic Salmon (Salmo salar). Can. J. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 2011, 44, 120–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fausch, K.D. Profitable stream positions for salmonids: Relating specific growth rate to net energy gain. Rev. Can. Zool. 1984, 62, 441–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, C. Relationship between shape and trophic ecology of selected species of Sparids of the Caprolace coastal lagoon (Central Tyrrhenian Sea). Environ. Biol. Fishes 2007, 78, 115–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, X. Genome Assembly, Annotation, and Comparative Genomic Analysis of Hemiculter leucisculus and Hemiculter tchangi. Master’s Thesis, Northwest A&F University, Xianyang, China, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Li, W.J.; Gao, X.; Liu, H.Z.; Cao, W.X. Coexistence of Two Closely Related Cyprinid Fishes (Hemiculter bleekeri and Hemiculter leucisculus) in the Upper Yangtze River, China. Diversity 2020, 12, 284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Z.; Tang, W.; Zhang, Y.; Guo, H. Microplastic Pollution in Dominant Fish Species along the Jingjiang Section of the Lower Reaches of the Yangtze River. Freshw. Fish. 2024, 54, 57–65. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Z.; Tian, J.; Wang, Y.; Li, J.; Liu, K. Community Characteristics of Larval and Juvenile Fish in the Anqing Section of the Yangtze River in the First Year of Fishing Ban. Acta Hydrobiol. Sin. 2024, 48, 537–545. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Deng, Y.; Liu, S.; Li, P.; Liu, K. Analysis of fish community status and preliminary assessment of fishing ban effectiveness in the initial period of fishing ban in the lower Yangtze River. J. Fish. China 2023, 47, 206–218. [Google Scholar]

- Ni, Y.; Zhu, C. (Eds.) Fish Fauna of Taihu Lake; Shanghai Scientific & Technical Publishers: Shanghai, China, 2005; ISBN 7-5323-7995-7. [Google Scholar]

- Li, H.; Guo, H.; Tang, W.; Gu, S.; Huang, S.; Shen, L.; Wei, K. Temporal Patterns of Hemiculter leucisculus Catch and ARIMA Model Prediction in the Jingjiang Section along the Lower Reaches of the Yangtze River. J. Fish. Sci. China 2009, 16, 357–364. [Google Scholar]

- Dai, X.; Li, W.; Tian, S. Complete mitochondrial genome of Hemiculter bleekeri bleekeri. Mitochondrial DNA A DNA Mapp. Seq. Anal. 2016, 27, 4338–4339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zou, Y.; Liu, T.; Li, Q.; Wen, Z.; Qin, C.; Li, R.; Wang, D. Complete mitochondrial genome of Hemiculter tchangi (Cypriniformes, Cyprinidae). Conserv. Genet. Resour. 2019, 11, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Zhu, T.; Yu, F. The New Mitochondrial Genome of Hemiculte rellawui (Cypriniformes, Xenocyprididae): Sequence, Structure, and Phylogenetic Analyses. Genes 2023, 14, 2110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Zhu, L.; Tang, K.; Liu, M.; Xue, X.; Wang, G.; Wang, Z. Population genetic structure of sharpbelly Hemiculter leucisculus (Basilesky, 1855) and morphological diversification along climate gradients in China. Ecol. Evol. 2021, 11, 6798–6813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, S.; Hu, Z.; Lu, Z.; Liu, L.; Liu, X.; Zhou, Q.; Huo, B.; Li, D.; Tang, R. Genetic Diversity and Population Structure of Hemiculter leucisculus (Basilesky, 1855) in Xinjiang Tarim River. Genes 2022, 13, 1790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Wang, H.; Yang, X.; Liu, J.; Wang, H.; Yu, Y.; Su, X.; Fan, Y.; Liu, H.; Yang, R. Telomere-to-telomere gap-free genome assembly of Euchiloglanis kishinouyei. Sci. Data 2025, 12, 757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Kron, N.S.; Young, B.D.; Drown, M.K.; McDonald, M.D. Long-read de novo genome assembly of Gulf toadfish (Opsanus beta). BMC Genom. 2024, 25, 871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Wang, M.; Liu, F.; Lin, P.; Yang, S.; Liu, H. Evolutionary dynamics of ecological niche in three Rhinogobio fishes from the upper Yangtze River inferred from morphological traits. Ecol. Evol. 2015, 5, 567–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Bonenfant, B.; Noé, L.; Touzet, H. Porechop_ABI: Discovering unknown adapters in ONT sequencing reads for downstream trimming. bioRxiv 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GB/T35892-2018; Laboratory Animal—Guideline for Ethical Review of Animal Welfare. Standards Press of China (SPC): Beijing, China, 2018.

- Chen, S.; Zhou, Y.; Chen, Y.; Gu, J. fastp: An ultra-fast all-in-one FASTQ preprocessor. Cold Spring Harb. Lab. 2018, 34, i884–i890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vurture, G.W.; Sedlazeck, F.J.; Nattestad, M.; Underwood, C.J.; Fang, H.; Gurtowski, J.; Schatz, M.C. GenomeScope: Fast reference-free genome profiling from short reads. Bioinformatics 2017, 33, 2202–2204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chaisson, M.J.; Tesler, G. Mapping single molecule sequencing reads using basic local alignment with successive refinement (BLASR): Application and theory. BMC Bioinform. 2012, 19, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Cheng, H.; Concepcion, G.T.; Feng, X.; Zhang, H.; Li, H. Haplotype-resolved de novo assembly using phased assembly graphs with hifiasm. Nat. Methods 2021, 18, 170–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- van Rengs, W.M.J.; Schmidt, M.H.; Effgen, S.; Le, D.B.; Wang, Y.; Zaidan, M.W.A.M.; Huettel, B.; Schouten, H.J.; Usadel, B.; Underwood, C.J. A chromosome scale tomato genome built from complementary PacBio and Nanopore sequences alone reveals extensive linkage drag during breeding. Plant J. 2022, 110, 572–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walker, B.J.; Abeel, T.; Shea, T.; Priest, M.; Abouelliel, A.; Sakthikumar, S.; Cuomo, C.A.; Zeng, Q.; Wortman, J.; Young, S.K.; et al. Pilon: An integrated tool for comprehensive microbial variant detection and genome assembly improvement. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e112963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Wingett, S.; Ewels, P.; Furlan-Magaril, M.; Nagano, T.; Schoenfelder, S.; Fraser, P.; Andrews, S. HiCUP: Pipeline for mapping and processing Hi-C data. F1000Research 2015, 20, 1310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Dudchenko, O.; Batra, S.S.; Omer, A.D.; Nyquist, S.K.; Hoeger, M.; Durand, N.C.; Shamim, M.S.; Machol, I.; Lander, E.S.; Aiden, A.P.; et al. De novo assembly of the Aedes aegypti genome using Hi-C yields chromosome-length scaffolds. Science 2017, 356, 92–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Durand, N.C.; Shamim, M.S.; Machol, I.; Rao, S.S.; Huntley, M.H.; Lander, E.S.; Aiden, E.L. Juicer Provides a One-Click System for Analyzing Loop-Resolution Hi-C Experiments. Cell Syst. 2016, 3, 95–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Xu, M.; Guo, L.; Gu, S.; Wang, O.; Zhang, R.; Peters, B.A.; Fan, G.; Liu, X.; Xu, X.; Deng, L.; et al. TGS-GapCloser: A fast and accurate gap closer for large genomes with low coverage of error-prone long reads. Gigascience 2020, 9, giaa094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Manni, M.; Berkeley, M.R.; Seppey, M.; Zdobnov, E.M. BUSCO: Assessing Genomic Data Quality and Beyond. Curr. Protoc. 2021, 1, e323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, Z.; Wang, H. LTR_FINDER: An efficient tool for the prediction of full-length LTR retrotransposons. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007, 35, W265–W268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Edgar, R.C.; Myers, E.W. PILER: Identification and classification of genomic repeats. Bioinformatics 2005, 21, i152–i158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stanke, M.; Diekhans, M.; Baertsch, R.; Haussler, D. Using native and syntenically mapped cDNA alignments to improve de novo gene finding. Bioinformatics 2008, 24, 637–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McGinnis, S.; Madden, T.L. BLAST: At the core of a powerful and diverse set of sequence analysis tools. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004, 32, W20–W25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Kim, D.; Paggi, J.M.; Park, C.; Bennett, C.; Salzberg, S.L. Graph-based genome alignment and genotyping with HISAT2 and HISAT-genotype. Nat. Biotechnol. 2019, 37, 907–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Kovaka, S.; Zimin, A.V.; Pertea, G.M.; Razaghi, R.; Salzberg, S.L.; Pertea, M. Transcriptome assembly from long-read RNA-seq alignments with StringTie2. Genome Biol. 2019, 20, 278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Lowe, T.M.; Eddy, S.R. tRNAscan-SE: A program for improved detection of transfer RNA genes in genomic sequence. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997, 25, 955–964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Kwon, D.; Park, N.; Wy, S.; Lee, D.; Chai, H.H.; Cho, I.C.; Lee, J.; Kwon, K.; Kim, H.; Moon, Y.; et al. A chromosome-level genome assembly of the Korean crossbred pig Nanchukmacdon (Sus scrofa). Sci. Data 2023, 10, 761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Jones, P.; Binns, D.; Chang, H.Y.; Fraser, M.; Li, W.; McAnulla, C.; McWilliam, H.; Maslen, J.; Mitchell, A.; Nuka, G.; et al. InterProScan 5: Genome-scale protein function classification. Bioinformatics 2014, 30, 1236–1240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Buchfink, B.; Reuter, K.; Drost, H.G. Sensitive protein alignments at tree-of-life scale using DIAMOND. Nat. Methods 2021, 18, 366–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Emms, D.M.; Kelly, S. OrthoFinder: Phylogenetic orthology inference for comparative genomics. Genome Biol. 2019, 20, 238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Nakamura, T.; Yamada, K.D.; Tomii, K.; Katoh, K. Parallelization of MAFFT for large-scale multiple sequence alignments. Bioinformatics 2018, 34, 2490–2492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Stamatakis, A. RAxML version 8: A tool for phylogenetic analysis and post-analysis of large phylogenies. Bioinformatics 2014, 30, 1312–1313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Yang, L.; Sun, N.; Zeng, H.; Wang, Y.; Chen, W.; Ding, Z.; Liu, Y.; Wang, J.; Meng, M.; Shen, Y.; et al. Enlarged fins of Tibetan catfish provide new evidence of adaptation to high plateau. Sci. China Life Sci. 2023, 66, 1554–1568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, S.; Suleski, M.; Craig, J.M.; Kasprowicz, A.E.; Sanderford, M.; Li, M.; Stecher, G.; Hedges, S.B. TimeTree 5: An Expanded Resource for Species Divergence Times. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2022, 39, msac174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Sun, P.; Jiao, B.; Yang, Y.; Shan, L.; Li, T.; Li, X.; Xi, Z.; Wang, X.; Liu, J. WGDI: A user-friendly toolkit for evolutionary analyses of whole-genome duplications and ancestral karyotypes. Mol. Plant 2022, 15, 1841–1851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, H.; Bowers, J.E.; Wang, X.; Ming, R.; Alam, M.; Paterson, A.H. Synteny and collinearity in plant genomes. Science 2008, 320, 486–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mendes, F.K.; Vanderpool, D.; Fulton, B.; Hahn, M.W. CAFE 5 models variation in evolutionary rates among gene families. Bioinformatics 2021, 36, 5516–5518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lahnsteiner, F.; Jagsch, A. Changes in Phenotype and Genotype of Austrian Salmo trutta Populations during the Last Century. Environ. Biol. Fishes 2005, 74, 51–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naspleda, J.; Vila-Gispert, A.; Fox, M.G.; Zamora, L.; Ruiz-Navarro, A. Morphological variation between non-native lake- and stream-dwelling pumpkinseed Lepomis gibbosusin the Iberian Peninsula. J. Fish Biol. 2012, 81, 1915–1935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Samaee, S.M.; Patzner, R.A.; Mansour, N. Morphological differentiation within the population of Siah Mahi, Capoeta capoeta gracilis, (Cyprinidae, Teleostei) in a river of the south Caspian Sea basin: A pilot study. J. Appl. Ichthyol. 2010, 25, 583–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, F.; Wang, S.; Wang, H.; Wang, A.; Xu, D.; Liu, H.; Yang, B.; Yuan, L.; Lei, L.; Chen, R.; et al. A chromosome-level reference genome of a Convolvulaceae species Ipomoea cairica. G3 2022, 12, jkac187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Yin, D.; Chen, C.; Lin, D.; Hua, Z.; Ying, C.; Zhang, J.; Zhao, C.; Liu, Y.; Cao, Z.; Zhang, H.; et al. Telomere-to-telomere gap-free genome assembly of the endangered Yangtze finless porpoise and East Asian finless porpoise. Gigascience 2024, 13, giae067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Sato, T.; Narimatsu, H. Beta-1,3-Glucosyltransferase (B3GALTL); Springer: Tokyo, Japan, 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato, T.; Sato, M.; Kiyohara, K.; Sogabe, M.; Shikanai, T.; Kikuchi, N.; Togayachi, A.; Ishida, H.; Ito, H.; Kameyama, A.; et al. Molecular cloning and characterization of a novel human beta1,3-glucosyltransferase, which is localized at the endoplasmic reticulum and glucosylates O-linked fucosylglycan on thrombospondin type 1 repeat domain. Glycobiology 2006, 16, 1194–1206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ayoubi, R.; Fotouhi, M.; Alende, C.; Bolívar, S.G.; Southern, K.; Laflamme, C.; Neuro/SGC/EDDU Collaborative Group; ABIF Consortium. A guide to selecting high-performing antibodies for Protein-glutamine gamma-glutamyltransferase 2 (TGM2) for use in western blot, immunoprecipitation and immunofluorescence. F1000Research 2024, 13, 481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canovas, S.; Cibelli, J.B.; Ross, P.J. Jumonji domain-containing protein 3 regulates histone 3 lysine 27 methylation during bovine preimplantation development. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2012, 109, 2400–2405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricote, M.; Li, A.C.; Willson, T.M.; Kelly, C.J.; Glass, C.K. The peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma is a negative regulator of macrophage activation. Nature 1997, 391, 79–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.; Han, K.; Wu, Y.; Bai, H.; Ke, Q.; Pu, F.; Wang, Y.; Xu, P. Genome-Wide Association Study of Growth and Body-Shape-Related Traits in Large Yellow Croaker (Larimichthys crocea) Using ddRAD Sequencing. Mar. Biotechnol. 2019, 21, 655–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, F.; Wang, Y.; He, J.; Chen, L.; Xue, G.; Zhao, Y.; Peng, Y.; Smith, C.; Zhang, J.; Chen, J.; et al. Molecular Mechanisms of Spawning Habits for the Adaptive Radiation of Endemic East Asian Cyprinid Fishes. Research 2022, 2022, 9827986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Kawaguchi, M.; Sano, K.; Yoshizaki, N.; Shimizu, D.; Fujinami, Y.; Noda, T.; Yasumasu, S. Comparison of hatching mode in pelagic and demersal eggs of two closely related species in the order pleuronectiformes. Zoolog. Sci. 2014, 31, 709–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Chen, F.; He, J.; Xue, G.; Chen, J.; Xie, P. Cellular and molecular modification of egg envelope hardening in fertilization. Biochimie 2021, 181, 134–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamagami, K.; Hamazaki, T.S.; Yasumasu, S.; Masuda, K.; Iuchi, I. Molecular and cellular basis of formation, hardening, and breakdown of the egg envelope in fish. Int. Rev. Cytol. 1992, 136, 51–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Cheng, J.; Siejka-Zielińska, P.; Weldon, C.; Roberts, H.; Lopopolo, M.; Magri, A.; D’Arienzo, V.; Harris, J.M.; McKeating, J.A.; et al. Accurate targeted long-read DNA methylation and hydroxymethylation sequencing with TAPS. Genome Biol. 2020, 2, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Jayakumar, V.; Sakakibara, Y. Comprehensive evaluation of non-hybrid genome assembly tools for third-generation PacBio long-read sequence data. Brief. Bioinform. 2019, 20, 866–876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Jiang, H.; Qian, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Meng, M.; Deng, Y.; Wang, G.; He, S.; Yang, L. Chromosome-level genome assembly and whole-genome resequencing of topmouth culter (Culter alburnus) provide insights into the intraspecific variation of its semi-buoyant and adhesive eggs. Mol. Ecol. Resour. 2023, 23, 1841–1852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Q.; Wang, X.; Yekefenhazi, D.; Wang, J.; Zhong, K.; Zhang, Y.; Fu, H.; Zhou, Z.; Huang, J.; Li, W.; et al. Assembling chromosome-level genomes of male and female Chanodichthys mongolicus using PacBio HiFi reads and Hi-C technologies. Sci. Data 2025, 12, 949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Zhao, S.; Yang, X.; Pang, B.; Zhang, L.; Wang, Q.; He, S.; Dou, H.; Zhang, H. A chromosome-level genome assembly of the redfin culter (Chanodichthys erythropterus). Sci. Data 2022, 9, 535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Gaither, M.R.; Gkafas, G.A.; de Jong, M.; Sarigol, F.; Neat, F.; Regnier, T.; Moore, D.; Gröcke, D.R.; Hall, N.; Liu, X.; et al. Genomics of habitat choice and adaptive evolution in a deep-sea fish. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 2018, 2, 680–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variables | Mean | PCA | p | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H. bleekeri | H. leucisculus | Principal Component 1 | Principal Component 2 | Principal Component 3 | ||

| BD/BL * | 0.205 ± 0.014 | 0.219 ± 0.024 | 0.172 | 0.190 | 0.722 | <0.01 ** |

| BW/BL | 0.096 ± 0.009 | 0.100 ± 0.025 | 0.203 | −0.041 | 0.885 | 0.199 |

| DFD/BL * | 0.494 ± 0.018 | 0.555 ± 0.068 | −0.156 | 0.975 | −0.056 | <0.01 ** |

| PFD/BL | 0.206 ± 0.028 | 0.225 ± 0.010 | −0.044 | 0.382 | 0.067 | <0.01 ** |

| VFD/BL | 0.460 ± 0.017 | 0.467 ± 0.422 | 0.094 | 0.270 | −0.209 | 0.224 |

| AFD/BL | 0.701 ± 0.018 | 0.696 ± 0.028 | 0.174 | −0.017 | 0.540 | 0.198 |

| DFB/BL | 0.103 ± 0.0133 | 0.093 ± 0.020 | 0.290 | −0.387 | 0.514 | <0.01 ** |

| PFB/BL | 0.043 ± 0.005 | 0.045 ± 0.006 | 0.074 | 0.194 | 0.386 | 0.004 ** |

| VFB/BL | 0.045 ± 0.006 | 0.038 ± 0.001 | 0.109 | −0.391 | 0.170 | <0.01 ** |

| AFB/BL | 0.158 ± 0.011 | 0.162 ± 0.043 | −0.009 | 0.191 | −0.735 | 0.336 |

| CFL/BL | 0.233 ± 0.126 | 0.200 ± 0.050 | −0.023 | −0.318 | −0.853 | <0.01 ** |

| CPD/BL | 0.093 ± 0.001 | 0.085 ± 0.008 | 0.434 | −0.366 | 0.339 | <0.01 ** |

| CPL/BL | 0.153 ± 0.015 | 0.147 ± 0.020 | −0.703 | −0.318 | 0.259 | 0.041 * |

| CPD/CPL | 0.614 ± 0.071 | 0.592 ± 0.115 | 0.998 | 0.049 | −0.024 | 0.152 |

| Explained variability (%) | / | / | 50.499 | 19.492 | 13.225 | / |

| Accumulative variability (%) | / | / | 50.499 | 69.991 | 83.216 | / |

| Library Type | H. bleekeri | H. leucisculus |

|---|---|---|

| Total size of assembled genome (Gb) | 0.998 | 1.05 |

| Contig N50 (Mb) | 40.45 | 40.66 |

| Contig N90 (Mb) | 34.17 | 36.51 |

| Number of contigs | 24 | 24 |

| Scaffold N50 (Mb) | 40.45 | 40.66 |

| Scaffold N90 (Mb) | 34.17 | 36.51 |

| Scaffolds number | 24 | 24 |

| Number of base chromosomes | 24 | 24 |

| Number of gap-free chromosomes | 24 | 24 |

| Number of candidate telomeres | 48 | 37 |

| Number of gaps | 0 | 0 |

| Number of telomeres (pairs/single) | 24/0 | 13/11 |

| Genome BUSCOs | 99.4% | 99.4% |

| QV | 43.15 | 44.39 |

| TE size | 50.66% | 52.19% |

| GC content | 37.82 | 37.42 |

| Number of genes | 26,168 | 26,446 |

| Gene BUSCOs | 99.4% | 99.4% |

| Heterozygosity | 1.51 | 1.10 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Liu, J.; Yin, D.; Ma, F.; Jiang, M.; Wang, X.; Wang, P.; Liu, K. Telomere-to-Telomere Genome Assembly of Two Hemiculter Species Provide Insights into the Genomic and Morphometric Bases of Adaptation to Flow Velocity. Biomolecules 2026, 16, 83. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom16010083

Liu J, Yin D, Ma F, Jiang M, Wang X, Wang P, Liu K. Telomere-to-Telomere Genome Assembly of Two Hemiculter Species Provide Insights into the Genomic and Morphometric Bases of Adaptation to Flow Velocity. Biomolecules. 2026; 16(1):83. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom16010083

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiu, Jie, Denghua Yin, Fengjiao Ma, Min Jiang, Xinyue Wang, Pan Wang, and Kai Liu. 2026. "Telomere-to-Telomere Genome Assembly of Two Hemiculter Species Provide Insights into the Genomic and Morphometric Bases of Adaptation to Flow Velocity" Biomolecules 16, no. 1: 83. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom16010083

APA StyleLiu, J., Yin, D., Ma, F., Jiang, M., Wang, X., Wang, P., & Liu, K. (2026). Telomere-to-Telomere Genome Assembly of Two Hemiculter Species Provide Insights into the Genomic and Morphometric Bases of Adaptation to Flow Velocity. Biomolecules, 16(1), 83. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom16010083