Oral–Gut Microbial Crosstalk and Therapeutic Applications of Bacterial Extracellular Vesicles

Abstract

1. Introduction

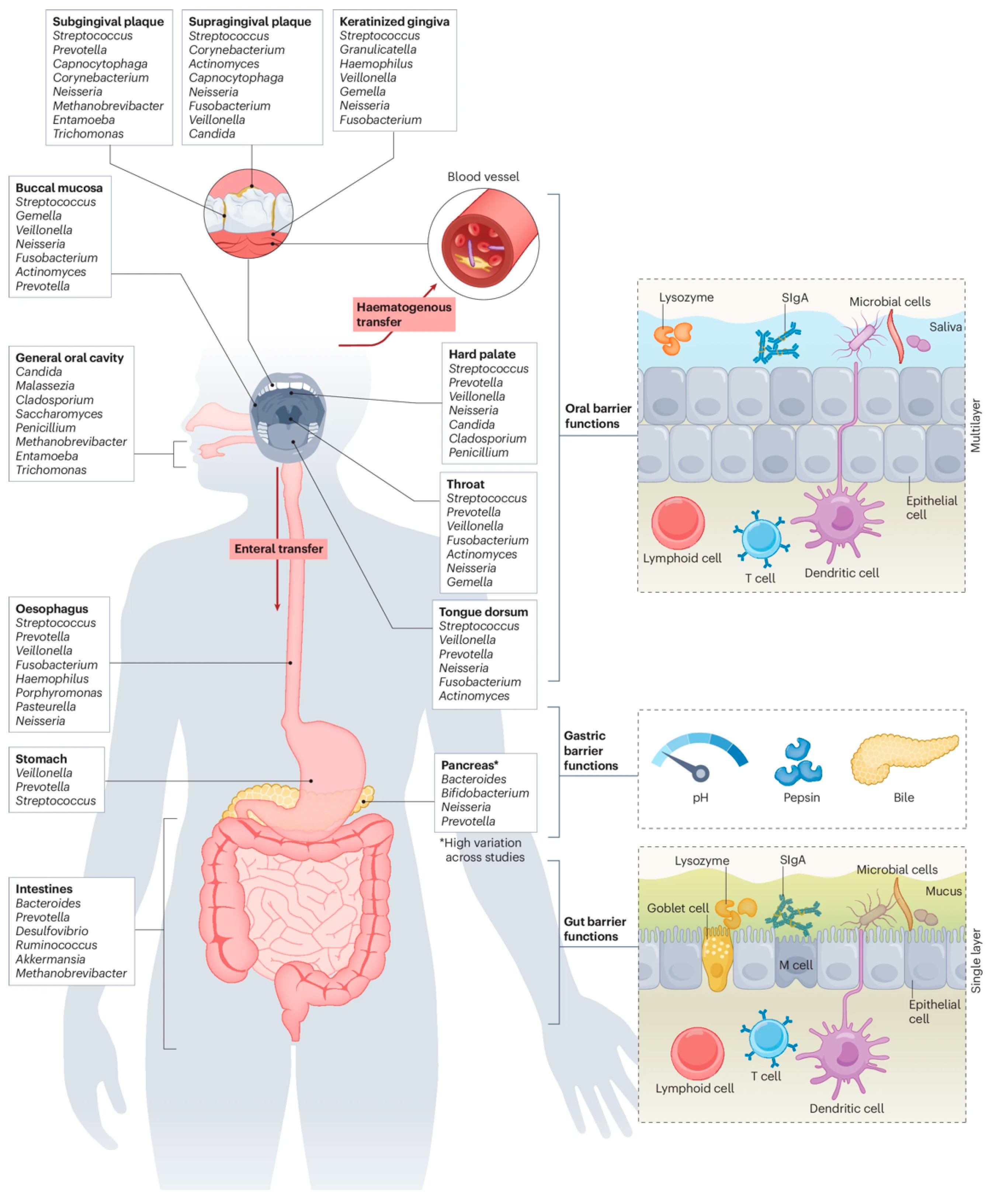

2. Oral–Gut Microbial Interactions in Diseases

2.1. Gut Dysbiosis Under Periodontitis

2.2. Oral Impact of IBD

| Disease | Classification | Abundance | Methods | Objects of Study | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Periodontitis | Lachnospiraceae | Increased | 16S rRNA sequencing | Fecal samples from patients with periodontitis | Baima, G. et al. [41] Bao, Jun. et al. [44] |

| Bacteroidota | Increased | 16S rRNA sequencing | Fecal samples from patients with periodontitis | Baima, G. et al. [41] Arimatsu, K. et al. [66] | |

| 16S rRNA sequencing | Ileal contents from Pg–treated mice | Sasaki, N. et al. [28] | |||

| Faecalibacterium | Increased | 16S rRNA sequencing | Fecal samples from patients with periodontitis | Baima, G. et al. [41] | |

| Clostridium | Increased | 16S rRNA sequencing | Fecal samples from patients with periodontitis | Bao, Jun. et al. [44] Kamer, A. R. et al. [67] | |

| Fusobacterium | Increased | High-throughput whole metagenome sequencing | Fecal samples from patients with periodontitis | Baima, G. et al. [68] | |

| Streptococcus | Decreased | 16S rRNA sequencing | Fecal samples from patients with periodontitis | Bao, Jun. et al. [44] | |

| High-throughput whole metagenome sequencing | Fecal samples from patients with periodontitis | Baima, G. et al. [68] | |||

| Porphyromonas | Increased | 16S rRNA sequencing | Fecal samples from patients with periodontitis | Bao, Jun. et al. [44] | |

| Lactobacillus | Decreased | 16S rRNA sequencing | Fecal samples from patients with periodontitis | Baima, G. et al. [41] Kamer, A. R. et al. [67] | |

| High-throughput whole metagenome sequencing | Fecal samples from patients with periodontitis | Baima, G. et al. [68] | |||

| Faecalibacterium | Decreased | High-throughput whole metagenome sequencing | Fecal samples from patients with periodontitis | Baima, G. et al. [68] | |

| Bacillota | Decreased | 16S rRNA sequencing | Ileal contents from Pg–treated mice | Sasaki, N. et al. [28] | |

| Turicibacter | Decreased | 16S rRNA sequencing | Oral Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans mice | Komazaki, R. et al. [69] | |

| IBD | Bacteroidota | Increased | 16S rRNA sequencing | Saliva from patients with IBD | Said, H. S. et al. [58] Docktor, M. J. et al. [70] Hu, S. et al. [53] |

| Prevotella | Increased | 16S rRNA sequencing | Saliva from patients with IBD | Said, H. S. et al. [58] | |

| Decreased | 16S rRNA sequencing | Saliva from patients with IBD | Xun, Z. et al. [71] | ||

| Veillonellaceae | Increased | 16S rRNA sequencing | Saliva from patients with IBD | Xun, Z. et al. [71] | |

| Fusobacteriota | Decreased | 16S rRNA sequencing | Tongue and buccal mucosal brushings from patients with IBD | Docktor, M. J. et al. [70] | |

| Lachnospiraceae | Decreased | 16S rRNA sequencing | Saliva from patients with IBD | Xun, Z. et al. [71] | |

| Streptococcaceae | Increased | 16S rRNA sequencing | Saliva from patients with IBD | Xun, Z. et al. [71] | |

| Decreased | 16S rRNA sequencing | Saliva from patients with IBD | Said, H. S. et al. [58] | ||

| Enterobacteriaceae | Increased | 16S rRNA sequencing | Saliva from patients with IBD | Xun, Z. et al. [71] |

3. Underlying Mechanisms of Oral–Gut Microbial Crosstalk

3.1. Direct Mechanisms

3.1.1. Microbial Migration and Colonization

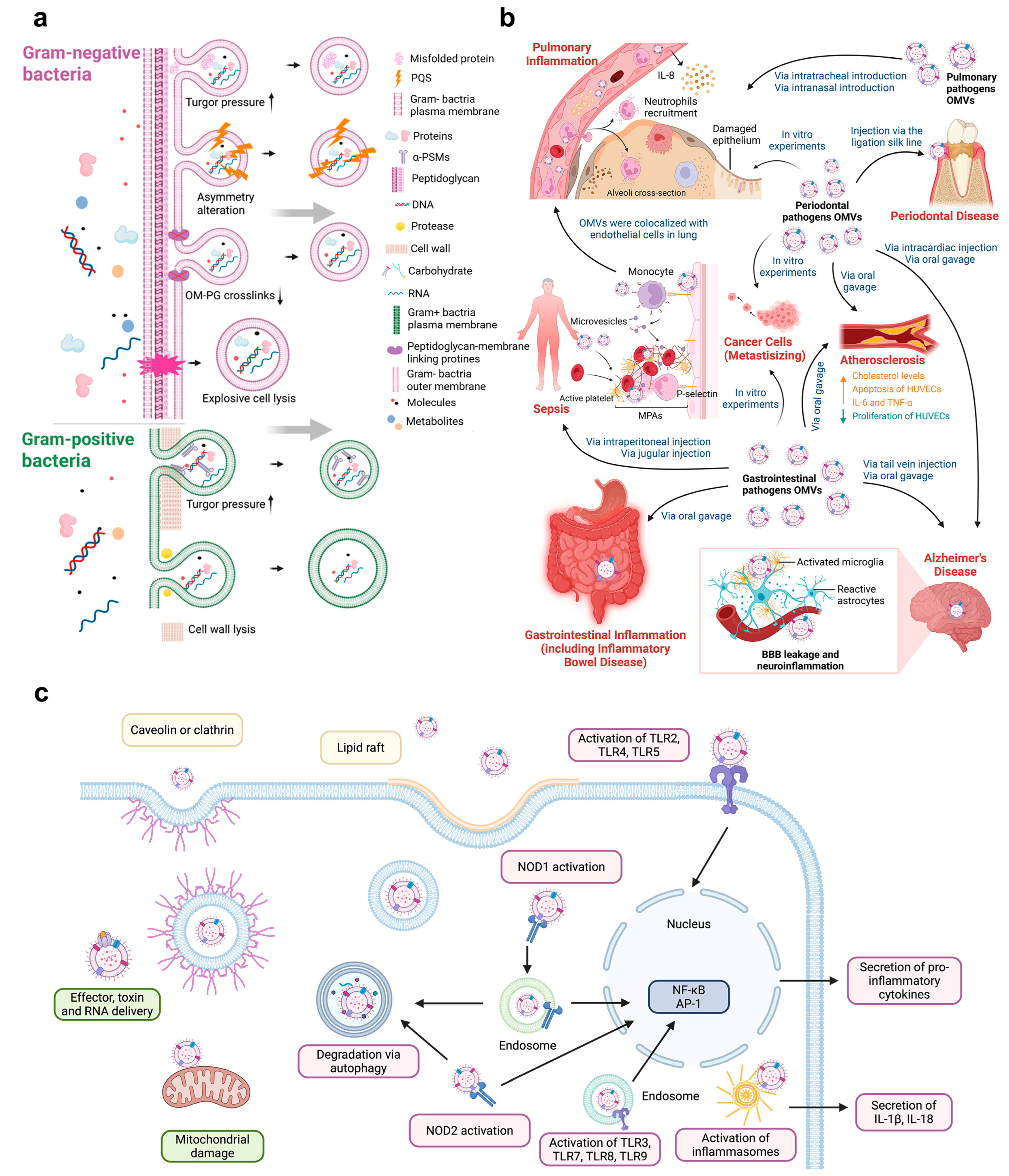

3.1.2. BEVs-Mediated Pathways

3.2. Indirect Mechanisms

3.2.1. Hematogenous Immune Route

3.2.2. Neuroimmune Route

3.2.3. BEVs-Mediated Pathways

| Mechanism Category | Mediating Route | Key Mediators/Factors | Effects | Associated Diseases | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Direct mechanisms | Microbial Migration and Colonization | Oral bacteria | Disrupt microbial homeostasis | IBD, periodontitis | Lourenço, T.G.B. et al. [42] |

| BEVs- Mediated Pathways | BEVs from oral pathogens (Pg, Fn), containing virulence factors | Increase epithelial barrier permeability by degradation of the tight junction protein. | IBD | Nonaka, S. et al. [95] | |

| Modulate autophagy via the miR-574-5p/CARD3 axis. | IBD | Wei, S. et al. [96] | |||

| Accelerate intestinal epithelial cells necroptosis by activating FADD-RIPK1-caspase 3 signaling. | IBD | Liu, L. et al. [97] | |||

| Indirect mechanisms | Hematogenous immune route | Immune cells (Th17, Treg, monocytes/macrophages), cytokines (IL-1β, IL-17, IFN-γ), microbial metabolites (linoleic acid) | Trigger local inflammatory response | Liver cirrhosis, Hepatitis | Mester, A. et al. [110] |

| Neuroimmune route | Inflammatory mediators (TNF-α, IL-1β), microbial products (LPS, SCFAs), Vagus nerve | Promote neuroinflammation via circulation/neuronal pathways | Alzheimer’s disease, Parkinson’s disease. | Sansores-España, L.D. et al. [114] | |

| BEVs- Mediated Pathways | BEVs from oral pathogens (Pg, Fn), containing virulence factors | Promote pro-inflammatory response by binding TLR2 and inducing the NF-κB signaling pathway. | IBD | Martin-Gallausiaux, C. et al. [92], Wei, S. et al. [96], Liu, L. et al. [97] | |

| BEVs from oral pathogens (Fn), containing virulence factors | Present a target for bacterial adhesion by transferring to CRC cell surfaces. | CRC | Zheng, X. et al. [126] |

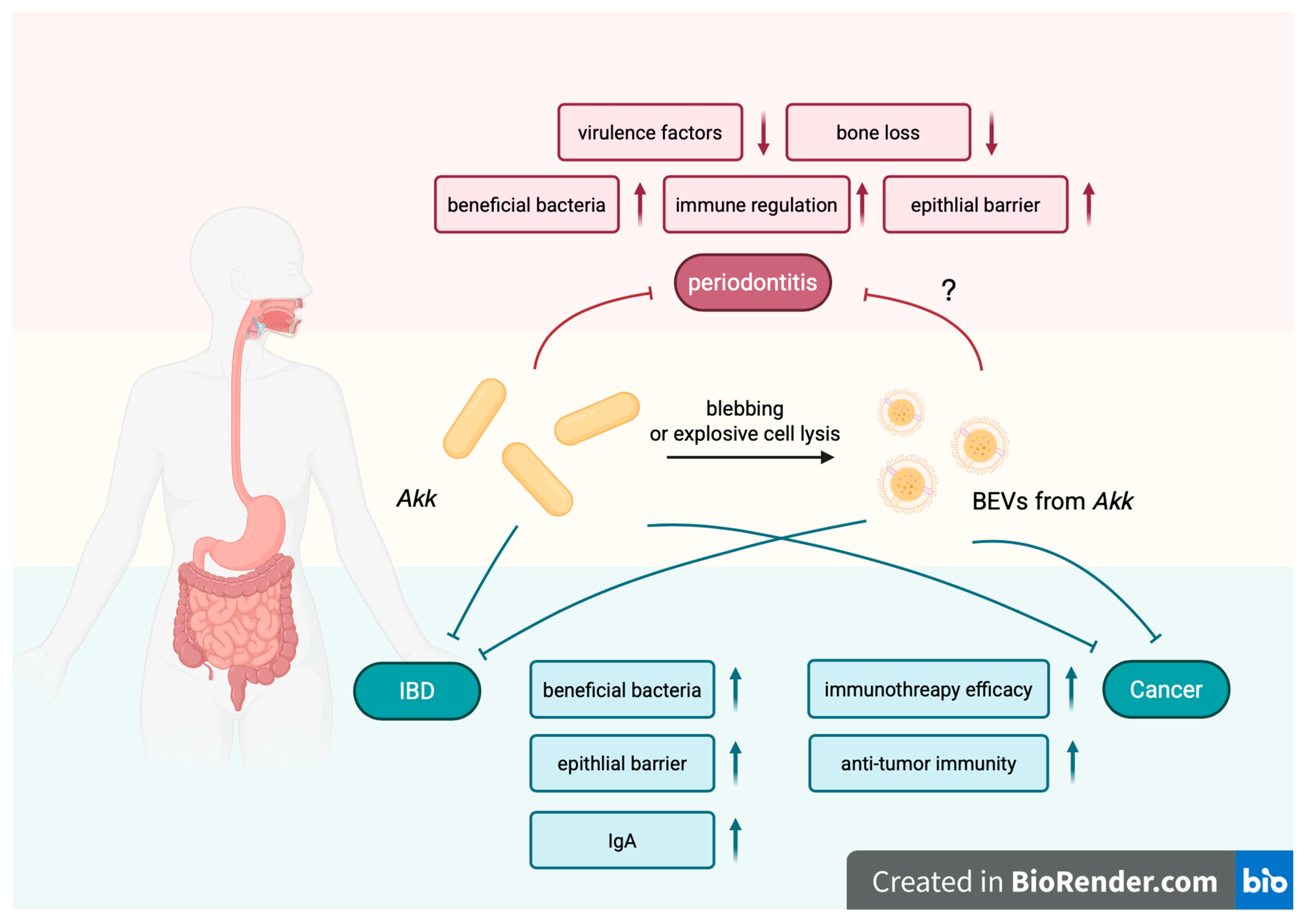

4. Therapeutic Application of Bacteria and Their BEVs Based on the Oral–Gut Microbial Crosstalk

5. Current Challenges and Controversies in Oral-to-Gut Microbial Translocation and BEV Research

6. Conclusions and Future Perspectives

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lu, H.X.; Tao, D.Y.; Lo, E.C.M.; Li, R.; Wang, X.; Tai, B.J.; Hu, Y.; Lin, H.C.; Wang, B.; Si, Y.; et al. The 4th National Oral Health Survey in the Mainland of China: Background and Methodology. Chin. J. Dent. Res. 2018, 21, 161–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, S.C.; Shi, H.Y.; Hamidi, N.; Underwood, F.E.; Tang, W.; Benchimol, E.I.; Panaccione, R.; Ghosh, S.; Wu, J.C.Y.; Chan, F.K.L.; et al. Worldwide incidence and prevalence of inflammatory bowel disease in the 21st century: A systematic review of population-based studies. Lancet 2017, 390, 2769–2778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; He, B.; Sun, Y.; Li, J.; Shen, P.; Hu, L.; Liu, G.; Wang, J.; Duan, L.; Zhan, S.; et al. Incidence of Inflammatory Bowel Disease in Urban China: A Nationwide Population-based Study. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2023, 21, 3379–3386.e3329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Z.; Ruan, G.; Bai, X.; Sun, Y.; Yang, H.; Qian, J. Growing burden of inflammatory bowel disease in China: Findings from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021 and predictions to 2035. Chin. Med. J. 2024, 137, 2851–2859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sender, R.; Fuchs, S.; Milo, R. Revised Estimates for the Number of Human and Bacteria Cells in the Body. PLoS Biol. 2016, 14, e1002533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Albuquerque-Souza, E.; Sahingur, S.E. Periodontitis, chronic liver diseases, and the emerging oral-gut-liver axis. Periodontol. 2000 2022, 89, 125–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glassner, K.L.; Abraham, B.P.; Quigley, E.M.M. The microbiome and inflammatory bowel disease. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2020, 145, 16–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ananthakrishnan, A.N.; Luo, C.; Yajnik, V.; Khalili, H.; Garber, J.J.; Stevens, B.W.; Cleland, T.; Xavier, R.J. Gut Microbiome Function Predicts Response to Anti-integrin Biologic Therapy in Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. Cell Host Microbe 2017, 21, 603–610.e603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foppa, C.; Rizkala, T.; Repici, A.; Hassan, C.; Spinelli, A. Microbiota and IBD: Current knowledge and future perspectives. Dig. Liver Dis. 2024, 56, 911–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Curtis, M.A.; Diaz, P.I.; Van Dyke, T.E. The role of the microbiota in periodontal disease. Periodontol. 2000 2020, 83, 14–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helmink, B.A.; Khan, M.A.W.; Hermann, A.; Gopalakrishnan, V.; Wargo, J.A. The microbiome, cancer, and cancer therapy. Nat. Med. 2019, 25, 377–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bungau, S.G.; Behl, T.; Singh, A.; Sehgal, A.; Singh, S.; Chigurupati, S.; Vijayabalan, S.; Das, S.; Palanimuthu, V.R. Targeting Probiotics in Rheumatoid Arthritis. Nutrients 2021, 13, 3376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, S.Y.; Hwang, B.O.; Lim, M.; Ok, S.H.; Lee, S.K.; Chun, K.S.; Park, K.K.; Hu, Y.; Chung, W.Y.; Song, N.Y. Oral-Gut Microbiome Axis in Gastrointestinal Disease and Cancer. Cancers 2021, 13, 2124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunath, B.J.; De Rudder, C.; Laczny, C.C.; Letellier, E.; Wilmes, P. The oral-gut microbiome axis in health and disease. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2024, 22, 791–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanwar, H.; Gnanasekaran, J.M.; Allison, D.; Chuang, L.S.; He, X.; Aimetti, M.; Baima, G.; Costalonga, M.; Cross, R.K.; Sears, C.; et al. Unravelling the Oral-Gut Axis: Interconnection Between Periodontitis and Inflammatory Bowel Disease, Current Challenges, and Future Perspective. J. Crohns Colitis 2024, 18, 1319–1341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, G.A.; Albarrak, H.; McColl, C.J.; Pizarro, A.; Sanaka, H.; Gomez-Nguyen, A.; Cominelli, F.; Paes Batista da Silva, A. The Oral-Gut Axis: Periodontal Diseases and Gastrointestinal Disorders. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2023, 29, 1153–1164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kitamoto, S.; Nagao-Kitamoto, H.; Jiao, Y.; Gillilland, M.G.; Hayashi, A.; Imai, J.; Sugihara, K.; Miyoshi, M.; Brazil, J.C.; Kuffa, P.; et al. The Intermucosal Connection between the Mouth and Gut in Commensal Pathobiont-Driven Colitis. Cell 2020, 182, 447–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bustamante, M.; Oomah, B.D.; Mosi-Roa, Y.; Rubilar, M.; Burgos-Díaz, C. Probiotics as an Adjunct Therapy for the Treatment of Halitosis, Dental Caries and Periodontitis. Probiotics Antimicrob Proteins 2020, 12, 325–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, S.; Dhaneshwar, S. Role of prebiotics, probiotics, and synbiotics in management of inflammatory bowel disease: Current perspectives. World J. Gastroenterol. 2023, 29, 2078–2100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajasekaran, J.J.; Krishnamurthy, H.K.; Bosco, J.; Jayaraman, V.; Krishna, K.; Wang, T.; Bei, K. Oral Microbiome: A Review of Its Impact on Oral and Systemic Health. Microorganisms 2024, 12, 1797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, J.; Li, Q.; Haesebrouck, F.; Van Hoecke, L.; Vandenbroucke, R.E. The tremendous biomedical potential of bacterial extracellular vesicles. Trends Biotechnol. 2022, 40, 1173–1194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Lin, S.; Wang, L.; Cao, Z.; Zhang, M.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, R.; Liu, J. Versatility of bacterial outer membrane vesicles in regulating intestinal homeostasis. Sci. Adv. 2023, 9, eade5079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiku, V.; Tan, M.W. Host immunity and cellular responses to bacterial outer membrane vesicles. Trends Immunol. 2021, 42, 1024–1036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segata, N.; Haake, S.K.; Mannon, P.; Lemon, K.P.; Waldron, L.; Gevers, D.; Huttenhower, C.; Izard, J. Composition of the adult digestive tract bacterial microbiome based on seven mouth surfaces, tonsils, throat and stool samples. Genome Biol. 2012, 13, R42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajishengallis, G.; Liang, S.; Payne, M.A.; Hashim, A.; Jotwani, R.; Eskan, M.A.; McIntosh, M.L.; Alsam, A.; Kirkwood, K.L.; Lambris, J.D.; et al. Low-abundance biofilm species orchestrates inflammatory periodontal disease through the commensal microbiota and complement. Cell Host Microbe 2011, 10, 497–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hajishengallis, G.; Darveau, R.P.; Curtis, M.A. The keystone-pathogen hypothesis. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2012, 10, 717–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaikh, H.F.M.; Patil, S.H.; Pangam, T.S.; Rathod, K.V. Polymicrobial synergy and dysbiosis: An overview. J. Indian Soc. Periodontol. 2018, 22, 101–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sasaki, N.; Katagiri, S.; Komazaki, R.; Watanabe, K.; Maekawa, S.; Shiba, T.; Udagawa, S.; Takeuchi, Y.; Ohtsu, A.; Kohda, T.; et al. Endotoxemia by Porphyromonas gingivalis Injection Aggravates Non-alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease, Disrupts Glucose/Lipid Metabolism, and Alters Gut Microbiota in Mice. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 2470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abusleme, L.; Hoare, A.; Hong, B.Y.; Diaz, P.I. Microbial signatures of health, gingivitis, and periodontitis. Periodontol. 2000 2021, 86, 57–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iniesta, M.; Chamorro, C.; Ambrosio, N.; Marín, M.J.; Sanz, M.; Herrera, D. Subgingival microbiome in periodontal health, gingivitis and different stages of periodontitis. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2023, 50, 905–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iwasaki, T.; Hirose, A.; Azuma, T.; Ohashi, T.; Watanabe, K.; Obora, A.; Deguchi, F.; Kojima, T.; Isozaki, A.; Tomofuji, T. Correlation between ultrasound-diagnosed non-alcoholic fatty liver and periodontal condition in a cross-sectional study in Japan. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 7496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alakhali, M.S.; Al-Maweri, S.A.; Al-Shamiri, H.M.; Al-Haddad, K.; Halboub, E. The potential association between periodontitis and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: A systematic review. Clin. Oral Investig. 2018, 22, 2965–2974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Read, E.; Curtis, M.A.; Neves, J.F. The role of oral bacteria in inflammatory bowel disease. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2021, 18, 731–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brennan, C.A.; Garrett, W.S. Fusobacterium nucleatum—Symbiont, opportunist and oncobacterium. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2019, 17, 156–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, X.; Lu, Q.; Zhang, Q.; He, Y.; Wei, W.; Wang, Y. Oral microbiota alteration associated with oral cancer and areca chewing. Oral Dis. 2021, 27, 226–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Li, C.; Cao, W.; Zhang, Z. Alterations of Gastric Microbiota in Gastric Cancer and Precancerous Stages. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2021, 11, 559148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zanetta, P.; Squarzanti, D.F.; Sorrentino, R.; Rolla, R.; Aluffi Valletti, P.; Garzaro, M.; Dell’Era, V.; Amoruso, A.; Azzimonti, B. Oral microbiota and vitamin D impact on oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinogenesis: A narrative literature review. Crit. Rev. Microbiol. 2021, 47, 224–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jungbauer, G.; Stähli, A.; Zhu, X.; Auber Alberi, L.; Sculean, A.; Eick, S. Periodontal microorganisms and Alzheimer disease—A causative relationship? Periodontol. 2000 2022, 89, 59–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beydoun, M.A.; Beydoun, H.A.; Hedges, D.W.; Erickson, L.D.; Gale, S.D.; Weiss, J.; El-Hajj, Z.W.; Evans, M.K.; Zonderman, A.B. Infection burden, periodontal pathogens, and their interactive association with incident all-cause and Alzheimer’s disease dementia in a large national survey. Alzheimers Dement. 2024, 20, 6468–6485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsha, T.E.; Prince, Y.; Davids, S.; Chikte, U.; Erasmus, R.T.; Kengne, A.P.; Davison, G.M. Oral Microbiome Signatures in Diabetes Mellitus and Periodontal Disease. J. Dent. Res. 2020, 99, 658–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baima, G.; Ferrocino, I.; Del Lupo, V.; Colonna, E.; Thumbigere-Math, V.; Caviglia, G.P.; Franciosa, I.; Mariani, G.M.; Romandini, M.; Ribaldone, D.G.; et al. Effect of Periodontitis and Periodontal Therapy on Oral and Gut Microbiota. J. Dent. Res. 2024, 103, 359–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lourenço, T.G.B.; De Oliveira, A.M.; Tsute Chen, G.; Colombo, A.P.V. Oral-gut bacterial profiles discriminate between periodontal health and diseases. J. Periodontal Res. 2022, 57, 1227–1237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kageyama, S.; Sakata, S.; Ma, J.; Asakawa, M.; Takeshita, T.; Furuta, M.; Ninomiya, T.; Yamashita, Y. High-Resolution Detection of Translocation of Oral Bacteria to the Gut. J. Dent. Res. 2023, 102, 752–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, J.; Li, L.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, M.; Chen, F.; Ge, S.; Chen, B.; Yan, F. Periodontitis may induce gut microbiota dysbiosis via salivary microbiota. Int. J. Oral Sci. 2022, 14, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gan, G.; Lin, S.; Luo, Y.; Zeng, Y.; Lu, B.; Zhang, R.; Chen, S.; Lei, H.; Cai, Z.; Huang, X. Unveiling the oral-gut connection: Chronic apical periodontitis accelerates atherosclerosis via gut microbiota dysbiosis and altered metabolites in apoE(-/-) Mice on a high-fat diet. Int. J. Oral Sci. 2024, 16, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Han, J.; Nie, J.-Y.; Deng, T.; Li, C.; Fang, C.; Xie, W.-Z.; Wang, S.-Y.; Zeng, X.-T. Alterations and Correlations of Gut Microbiota and Fecal Metabolome Characteristics in Experimental Periodontitis Rats. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 865191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gan, G.; Luo, Y.; Zeng, Y.; Lin, S.; Lu, B.; Zhang, R.; Chen, S.; Lei, H.; Cai, Z.; Huang, X. Gut microbiota dysbiosis links chronic apical periodontitis to liver fibrosis in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: Insights from a mouse model. Int. Endod. J. 2024, 57, 1608–1622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oren, A.; Garrity, G.M. Valid publication of the names of forty-two phyla of prokaryotes. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2021, 71, 005056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roda, G.; Chien Ng, S.; Kotze, P.G.; Argollo, M.; Panaccione, R.; Spinelli, A.; Kaser, A.; Peyrin-Biroulet, L.; Danese, S. Crohn’s disease. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2020, 6, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baumgart, D.C.; Carding, S.R. Inflammatory bowel disease: Cause and immunobiology. Lancet 2007, 369, 1627–1640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuo, T.; Lu, X.J.; Zhang, Y.; Cheung, C.P.; Lam, S.; Zhang, F.; Tang, W.; Ching, J.Y.L.; Zhao, R.; Chan, P.K.S.; et al. Gut mucosal virome alterations in ulcerative colitis. Gut 2019, 68, 1169–1179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, B.; Liu, B.; Gao, X.; Xing, K.; Xie, L.; Guo, T. Metagenomic Analysis of Saliva Reveals Disease-Associated Microbiotas in Patients with Periodontitis and Crohn’s Disease-Associated Periodontitis. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2021, 11, 719411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, S.; Mok, J.; Gowans, M.; Ong, D.E.H.; Hartono, J.L.; Lee, J.W.J. Oral Microbiome of Crohn’s Disease Patients with and Without Oral Manifestations. J. Crohns Colitis 2022, 16, 1628–1636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Femiano, F.; Lanza, A.; Buonaiuto, C.; Perillo, L.; Dell’Ermo, A.; Cirillo, N. Pyostomatitis vegetans: A review of the literature. Med. Oral Patol. Oral Cir. Bucal 2009, 14, E114–E117. [Google Scholar]

- Lankarani, K.B. Oral manifestation in inflammatory bowel disease: A review. World J. Gastroenterol. 2013, 19, 8571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Xue, N.; Wang, Z.; Zeng, X.; Ji, N.; Chen, Q. Targeting Th17 cells: A promising strategy to treat oral mucosal inflammatory diseases. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1236856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rowland, M.; Fleming, P.; Bourke, B. Looking in the mouth for Crohn’s disease. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2010, 16, 332–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Said, H.S.; Suda, W.; Nakagome, S.; Chinen, H.; Oshima, K.; Kim, S.; Kimura, R.; Iraha, A.; Ishida, H.; Fujita, J.; et al. Dysbiosis of Salivary Microbiota in Inflammatory Bowel Disease and Its Association with Oral Immunological Biomarkers. DNA Res. 2014, 21, 15–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Atarashi, K.; Suda, W.; Luo, C.; Kawaguchi, T.; Motoo, I.; Narushima, S.; Kiguchi, Y.; Yasuma, K.; Watanabe, E.; Tanoue, T.; et al. Ectopic colonization of oral bacteria in the intestine drives T(H)1 cell induction and inflammation. Science 2017, 358, 359–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elmaghrawy, K.; Fleming, P.; Fitzgerald, K.; Cooper, S.; Dominik, A.; Hussey, S.; Moran, G.P. The Oral Microbiome in Treatment-Naïve Paediatric IBD Patients Exhibits Dysbiosis Related to Disease Severity that Resolves Following Therapy. J. Crohns Colitis 2023, 17, 553–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jose, F.A.; Heyman, M.B. Extraintestinal Manifestations of Inflammatory Bowel Disease. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 2008, 46, 124–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singhal, S.; Dian, D.; Keshavarzian, A.; Fogg, L.; Fields, J.Z.; Farhadi, A. The Role of Oral Hygiene in Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Dig. Dis. Sci. 2011, 56, 170–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vavricka, S.R.; Brun, L.; Ballabeni, P.; Pittet, V.; Prinz Vavricka, B.M.; Zeitz, J.; Rogler, G.; Schoepfer, A.M. Frequency and risk factors for extraintestinal manifestations in the Swiss inflammatory bowel disease cohort. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2011, 106, 110–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Liu, Y.; Yang, X.; Li, C.; Song, Z. The Oral Microbiota: Community Composition, Influencing Factors, Pathogenesis, and Interventions. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 895537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veloso, F.T. Extraintestinal manifestations of inflammatory bowel disease: Do they influence treatment and outcome? World J. Gastroenterol. 2011, 17, 2702–2707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arimatsu, K.; Yamada, H.; Miyazawa, H.; Minagawa, T.; Nakajima, M.; Ryder, M.I.; Gotoh, K.; Motooka, D.; Nakamura, S.; Iida, T.; et al. Oral pathobiont induces systemic inflammation and metabolic changes associated with alteration of gut microbiota. Sci. Rep. 2014, 4, 4828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamer, A.R.; Pushalkar, S.; Hamidi, B.; Janal, M.N.; Tang, V.; Annam, K.R.C.; Palomo, L.; Gulivindala, D.; Glodzik, L.; Saxena, D. Periodontal Inflammation and Dysbiosis Relate to Microbial Changes in the Gut. Microorganisms 2024, 12, 1225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baima, G.; Dabdoub, S.; Thumbigere-Math, V.; Ribaldone, D.G.; Caviglia, G.P.; Tenori, L.; Fantato, L.; Vignoli, A.; Romandini, M.; Ferrocino, I.; et al. Multi-Omics Signatures of Periodontitis and Periodontal Therapy on the Oral and Gut Microbiome. J. Periodontal Res. 2025. Online ahead of print.

- Komazaki, R.; Katagiri, S.; Takahashi, H.; Maekawa, S.; Shiba, T.; Takeuchi, Y.; Kitajima, Y.; Ohtsu, A.; Udagawa, S.; Sasaki, N.; et al. Periodontal pathogenic bacteria, Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans affect non-alcoholic fatty liver disease by altering gut microbiota and glucose metabolism. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 13950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Docktor, M.J.; Paster, B.J.; Abramowicz, S.; Ingram, J.; Wang, Y.E.; Correll, M.; Jiang, H.; Cotton, S.L.; Kokaras, A.S.; Bousvaros, A. Alterations in diversity of the oral microbiome in pediatric inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2012, 18, 935–942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xun, Z.; Zhang, Q.; Xu, T.; Chen, N.; Chen, F. Dysbiosis and Ecotypes of the Salivary Microbiome Associated with Inflammatory Bowel Diseases and the Assistance in Diagnosis of Diseases Using Oral Bacterial Profiles. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 1136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toyofuku, M.; Schild, S.; Kaparakis-Liaskos, M.; Eberl, L. Composition and functions of bacterial membrane vesicles. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2023, 21, 415–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toyofuku, M.; Nomura, N.; Eberl, L. Types and origins of bacterial membrane vesicles. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2019, 17, 13–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silhavy, T.J.; Kahne, D.; Walker, S. The bacterial cell envelope. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2010, 2, a000414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Donoghue, E.J.; Krachler, A.M. Mechanisms of outer membrane vesicle entry into host cells. Cell. Microbiol. 2016, 18, 1508–1517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, P.; Chen, X.; Su, Z.; Luo, Y.; Wang, T.; Li, J.; Guo, L.; Luo, T. The Role of Oral and Gut Microbiota in Bone Health: Insights from Bacterial Extracellular Vesicles. Microorganisms 2025, 13, 2254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, S.; Lei, Q.; Zou, X.; Ma, D. The role and mechanisms of gram-negative bacterial outer membrane vesicles in inflammatory diseases. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1157813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, T.S.B.; Raes, J.; Bork, P. The Human Gut Microbiome: From Association to Modulation. Cell 2018, 172, 1198–1215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schubert, M.L.; Peura, D.A. Control of gastric acid secretion in health and disease. Gastroenterology 2008, 134, 1842–1860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sohn, J.; Sun, Y.; Genco, R.J.; Kirkwood, K.L. The Periodontal Microenvironment: A Potential Reservoir for Intestinal Pathobionts in Crohn’s Disease. Curr. Oral Health Rep. 2020, 7, 37–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francis, D.; Chawla, A.; LaComb, J.F.; Markarian, K.; Robertson, C.E.; Frank, D.N.; Gathungu, G.N. Gastroesophageal reflux and PPI exposure alter gut microbiota in very young infants. Front. Pediatr. 2023, 11, 1254329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Ge, Y.; Cheng, L.; Zeng, B.; Yu, J.; Peng, X.; Zhao, J.; Li, W.; Ren, B.; Li, M.; et al. Oral bacteria colonize and compete with gut microbiota in gnotobiotic mice. Int. J. Oral Sci. 2019, 11, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujita, K.; Takashima, Y.; Inagaki, S.; Nagayama, K.; Nomura, R.; Ardin, A.C.; Grönroos, L.; Alaluusua, S.; Ooshima, T.; Matsumoto-Nakano, M. Correlation of biological properties with glucan-binding protein B expression profile in Streptococcus mutans clinical isolates. Arch. Oral Biol. 2011, 56, 258–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, Y.K.; Wu, Q.L.; Peng, Y.W.; Liang, F.Y.; You, H.J.; Feng, Y.W.; Li, G.; Li, X.J.; Liu, S.H.; Li, Y.C.; et al. Oral P. gingivalis impairs gut permeability and mediates immune responses associated with neurodegeneration in LRRK2 R1441G mice. J. Neuro 2020, 17, 347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, W.; Zhou, W.; Wang, H.; Liang, S. Roles of Porphyromonas gingivalis and its virulence factors in periodontitis. Adv. Protein Chem. Struct. Biol. 2020, 120, 45–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, Y.; Kang, X.; Bai, X.; Pu, B.; Smerin, D.; Zhao, L.; Xiong, X. The Oral-Gut-Brain Axis: The Influence of Microbes as a Link of Periodontitis with Ischemic Stroke. CNS Neurosci. Ther. 2024, 30, e70152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, Y.; Xue, J.; Wang, H.; Tan, X.; Jiao, X.; Jiang, H. The recovery of intestinal barrier function and changes in oral microbiota after radiation therapy injury. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2023, 13, 1288666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, M.H.; Chen, C.H.; Goodwin, J.S.; Wang, B.Y.; Xie, H. Functional Advantages of Porphyromonas gingivalis Vesicles. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0123448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melo-Marques, I.; Cardoso, S.M.; Empadinhas, N. Bacterial extracellular vesicles at the interface of gut microbiota and immunity. Gut Microbes 2024, 16, 2396494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catalan, E.A.; Seguel-Fuentes, E.; Fuentes, B.; Aranguiz-Varela, F.; Castillo-Godoy, D.P.; Rivera-Asin, E.; Bocaz, E.; Fuentes, J.A.; Bravo, D.; Schinnerling, K.; et al. Oral Pathobiont-Derived Outer Membrane Vesicles in the Oral-Gut Axis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 11141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Lin, Y.; Li, S.; Bi, J.; Zeng, J.; Mo, C.; Xu, S.; Jia, B.; Lu, Y.; Liu, C.; et al. Effects of bacterial extracellular vesicles derived from oral and gastrointestinal pathogens on systemic diseases. Microbiol. Res. 2024, 285, 127788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin-Gallausiaux, C.; Malabirade, A.; Habier, J.; Wilmes, P. Fusobacterium nucleatum Extracellular Vesicles Modulate Gut Epithelial Cell Innate Immunity via FomA and TLR2. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 583644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabarrini, G.; Heida, R.; van Ieperen, N.; Curtis, M.A.; van Winkelhoff, A.J.; van Dijl, J.M. Dropping anchor: Attachment of peptidylarginine deiminase via A-LPS to secreted outer membrane vesicles of Porphyromonas gingivalis. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 8949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; Yu, C.; Zhang, X.; Chen, H.; Dong, J.; Lu, W.; Song, Z.; Zhou, W. Porphyromonas gingivalis lipopolysaccharide induces cognitive dysfunction, mediated by neuronal inflammation via activation of the TLR4 signaling pathway in C57BL/6 mice. J. Neuro 2018, 15, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nonaka, S.; Okamoto, R.; Katsuta, Y.; Kanetsuki, S.; Nakanishi, H. Gingipain-carrying outer membrane vesicles from Porphyromonas gingivalis cause barrier dysfunction of Caco-2 cells by releasing gingipain into the cytosol. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2024, 707, 149783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, S.; Zhang, J.; Wu, X.; Chen, M.; Huang, H.; Zeng, S.; Xiang, Z.; Li, X.; Dong, W. Fusobacterium nucleatum Extracellular Vesicles Promote Experimental Colitis by Modulating Autophagy via the miR-574-5p/CARD3 Axis. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2023, 29, 9–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Liang, L.; Yang, C.; Zhou, Y.; Chen, Y. Extracellular vesicles of Fusobacterium nucleatum compromise intestinal barrier through targeting RIPK1-mediated cell death pathway. Gut Microbes 2021, 13, 1902718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Wang, Y.; Fan, R.; Zhang, L.; Li, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Zheng, W.; Wang, L.; Liu, B.; Quan, C. Quantitative Proteomic Analysis of Outer Membrane Vesicles from Fusobacterium nucleatum Cultivated in the Mimic Cancer Environment. Microbiol. Spectr. 2023, 11, e0039423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, H.; Gong, T.; Sun, Y.; Yang, S.; Qiao, X.; Yang, D. Bacterial growth stage determines the yields, protein composition, and periodontal pathogenicity of Porphyromonas gingivalis outer membrane vesicles. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2023, 13, 1193198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veith, P.D.; Chen, Y.Y.; Gorasia, D.G.; Chen, D.; Glew, M.D.; O’Brien-Simpson, N.M.; Cecil, J.D.; Holden, J.A.; Reynolds, E.C. Porphyromonas gingivalis outer membrane vesicles exclusively contain outer membrane and periplasmic proteins and carry a cargo enriched with virulence factors. J. Proteome Res. 2014, 13, 2420–2432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mantri, C.K.; Chen, C.H.; Dong, X.; Goodwin, J.S.; Pratap, S.; Paromov, V.; Xie, H. Fimbriae-mediated outer membrane vesicle production and invasion of Porphyromonas gingivalis. Microbiologyopen 2015, 4, 53–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabarrini, G.; Grasso, S.; van Winkelhoff, A.J.; van Dijl, J.M. Gingimaps: Protein Localization in the Oral Pathogen Porphyromonas gingivalis. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2020, 84, e00032-19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haurat, M.F.; Aduse-Opoku, J.; Rangarajan, M.; Dorobantu, L.; Gray, M.R.; Curtis, M.A.; Feldman, M.F. Selective sorting of cargo proteins into bacterial membrane vesicles. J. Biol. Chem. 2011, 286, 1269–1276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanzoni, A.; Spinelli, L.; Braham, S.; Brun, C. Perturbed human sub-networks by Fusobacterium nucleatum candidate virulence proteins. Microbiome 2017, 5, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, J.W.; Kim, S.C.; Hong, S.H.; Lee, H.J. Secretable Small RNAs via Outer Membrane Vesicles in Periodontal Pathogens. J. Dent. Res. 2017, 96, 458–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diallo, I.; Provost, P. RNA-Sequencing Analyses of Small Bacterial RNAs and their Emergence as Virulence Factors in Host-Pathogen Interactions. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 1627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Irwandi, R.A.; Kuswandani, S.O.; Harden, S.; Marletta, D.; D’Aiuto, F. Circulating inflammatory cell profiling and periodontitis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2022, 111, 1069–1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lo, B.C.; Kryczek, I.; Yu, J.; Vatan, L.; Caruso, R.; Matsumoto, M.; Sato, Y.; Shaw, M.H.; Inohara, N.; Xie, Y.; et al. Microbiota-dependent activation of CD4(+) T cells induces CTLA-4 blockade-associated colitis via Fcγ receptors. Science 2024, 383, 62–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, L.; Jiang, Y.; Wu, L.; Fu, J.; Du, J.; Luo, Z.; Guo, L.; Xu, J.; Liu, Y. Porphyromonas gingivalis aggravates colitis via a gut microbiota-linoleic acid metabolism-Th17/Treg cell balance axis. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 1617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mester, A.; Ciobanu, L.; Taulescu, M.; Apostu, D.; Lucaciu, O.; Filip, G.A.; Feldrihan, V.; Licarete, E.; Ilea, A.; Piciu, A.; et al. Periodontal disease may induce liver fibrosis in an experimental study on Wistar rats. J. Periodontol. 2019, 90, 911–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greuter, T.; Vavricka, S.R. Extraintestinal manifestations in inflammatory bowel disease—Epidemiology, genetics, and pathogenesis. Expert Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2019, 13, 307–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loeb, L.; Janovska, M.; Ma, Y.; Rogers, R.; Farraye, F.A.; Bruce, A.; Chedid, V.; Kaur, M.; Bodiford, K.; Hashash, J.G. Oral Extraintestinal Manifestations of Inflammatory Bowel Disease: The Temporal Relationship Between Oral and Intestinal Symptoms. Crohns Colitis 360 2025, 7, otaf027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szymula, A.; Rosenthal, J.; Szczerba, B.M.; Bagavant, H.; Fu, S.M.; Deshmukh, U.S. T cell epitope mimicry between Sjögren’s syndrome Antigen A (SSA)/Ro60 and oral, gut, skin and vaginal bacteria. Clin. Immunol. 2014, 152, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sansores-España, L.D.; Melgar-Rodríguez, S.; Olivares-Sagredo, K.; Cafferata, E.A.; Martínez-Aguilar, V.M.; Vernal, R.; Paula-Lima, A.C.; Díaz-Zúñiga, J. Oral-Gut-Brain Axis in Experimental Models of Periodontitis: Associating Gut Dysbiosis with Neurodegenerative Diseases. Front. Aging 2021, 2, 781582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.; Zhang, S.; Huang, Y.; Qian, J.; Tan, B.; Qian, X.; Zhuang, J.; Zou, X.; Li, Y.; Yan, F. Periodontitis-related salivary microbiota aggravates Alzheimer’s disease via gut-brain axis crosstalk. Gut Microbes 2022, 14, 2126272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Kiprowska, M.; Kansara, T.; Kansara, P.; Li, P. Neuroinflammation: A Distal Consequence of Periodontitis. J. Dent. Res. 2022, 101, 1441–1449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carabotti, M.; Scirocco, A.; Maselli, M.A.; Severi, C. The gut-brain axis: Interactions between enteric microbiota, central and enteric nervous systems. Ann. Gastroenterol. 2015, 28, 203–209. [Google Scholar]

- E Engevik, M.A.; Danhof, H.A.; Ruan, W.; Engevik, A.C.; Chang-Graham, A.L.; Engevik, K.A.; Shi, Z.; Zhao, Y.; Brand, C.K.; Krystofiak, E.S.; et al. Fusobacterium nucleatum Secretes Outer Membrane Vesicles and Promotes Intestinal Inflammation. mBio 2021, 12, e02706-20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cecil, J.D.; O’Brien-Simpson, N.M.; Lenzo, J.C.; Holden, J.A.; Chen, Y.Y.; Singleton, W.; Gause, K.T.; Yan, Y.; Caruso, F.; Reynolds, E.C. Differential Responses of Pattern Recognition Receptors to Outer Membrane Vesicles of Three Periodontal Pathogens. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0151967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.; Sun, Q.; Cai, Q.; Zhou, H. Outer Membrane Vesicles From Fusobacterium nucleatum Switch M0-Like Macrophages Toward the M1 Phenotype to Destroy Periodontal Tissues in Mice. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 815638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- du Teil Espina, M.; Fu, Y.; van der Horst, D.; Hirschfeld, C.; López-Álvarez, M.; Mulder, L.M.; Gscheider, C.; Haider Rubio, A.; Huitema, M.; Becher, D.; et al. Coating and Corruption of Human Neutrophils by Bacterial Outer Membrane Vesicles. Microbiol. Spectr. 2022, 10, e0075322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waller, T.; Kesper, L.; Hirschfeld, J.; Dommisch, H.; Kölpin, J.; Oldenburg, J.; Uebele, J.; Hoerauf, A.; Deschner, J.; Jepsen, S.; et al. Porphyromonas gingivalis Outer Membrane Vesicles Induce Selective Tumor Necrosis Factor Tolerance in a Toll-Like Receptor 4- and mTOR-Dependent Manner. Infect. Immun. 2016, 84, 1194–1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zepeda-Rivera, M.; Minot, S.S.; Bouzek, H.; Wu, H.; Blanco-Míguez, A.; Manghi, P.; Jones, D.S.; LaCourse, K.D.; Wu, Y.; McMahon, E.F.; et al. A distinct Fusobacterium nucleatum clade dominates the colorectal cancer niche. Nature 2024, 628, 424–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alon-Maimon, T.; Mandelboim, O.; Bachrach, G. Fusobacterium nucleatum and cancer. Periodontol. 2000 2022, 89, 166–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akbari, E.; Epstein, J.B.; Samim, F. Unveiling the Hidden Links: Periodontal Disease, Fusobacterium Nucleatum, and Cancers. Curr. Oncol. Rep. 2024, 26, 1388–1397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, X.; Gong, T.; Luo, W.; Hu, B.; Gao, J.; Li, Y.; Liu, R.; Xie, N.; Yang, W.; Xu, X.; et al. Fusobacterium nucleatum extracellular vesicles are enriched in colorectal cancer and facilitate bacterial adhesion. Sci. Adv. 2024, 10, eado0016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubinstein, M.R.; Baik, J.E.; Lagana, S.M.; Han, R.P.; Raab, W.J.; Sahoo, D.; Dalerba, P.; Wang, T.C.; Han, Y.W. Fusobacterium nucleatum promotes colorectal cancer by inducing Wnt/β-catenin modulator Annexin A1. EMBO Rep. 2019, 20, e47638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rubinstein, M.R.; Wang, X.; Liu, W.; Hao, Y.; Cai, G.; Han, Y.W. Fusobacterium nucleatum promotes colorectal carcinogenesis by modulating E-cadherin/β-catenin signaling via its FadA adhesin. Cell Host Microbe 2013, 14, 195–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, P.; Bartold, P.M.; Ivanovski, S. The emerging role of small extracellular vesicles in saliva and gingival crevicular fluid as diagnostics for periodontitis. J. Periodontal Res. 2022, 57, 219–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanders, M.E.; Merenstein, D.J.; Reid, G.; Gibson, G.R.; Rastall, R.A. Probiotics and prebiotics in intestinal health and disease: From biology to the clinic. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2019, 16, 605–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ioannou, A.; Berkhout, M.D.; Geerlings, S.Y.; Belzer, C. Akkermansia muciniphila: Biology, microbial ecology, host interactions and therapeutic potential. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2025, 23, 162–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cani, P.D.; Depommier, C.; Derrien, M.; Everard, A.; de Vos, W.M. Akkermansia muciniphila: Paradigm for next-generation beneficial microorganisms. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2022, 19, 625–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Li, M.; Chen, Y.; Yu, Z.; Cheng, P.; Yu, Z.; Cheng, W.; Zhang, W.; Wang, Z.; Gao, X.; et al. Function and therapeutic prospects of next-generation probiotic Akkermansia muciniphila in infectious diseases. Front. Microbiol. 2024, 15, 1354447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Earley, H.; Lennon, G.; Balfe, Á.; Coffey, J.C.; Winter, D.C.; O’Connell, P.R. The abundance of Akkermansia muciniphila and its relationship with sulphated colonic mucins in health and ulcerative colitis. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 15683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavares, C.O.; Rost, F.L.; Silva, R.B.M.; Dagnino, A.P.; Adami, B.; Schirmer, H.; de Figueiredo, J.A.P.; Souto, A.A.; Maito, F.D.M.; Campos, M.M. Cross Talk between Apical Periodontitis and Metabolic Disorders: Experimental Evidence on the Role of Intestinal Adipokines and Akkermansia muciniphila. J. Endod. 2019, 45, 174–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huck, O.; Mulhall, H.; Rubin, G.; Kizelnik, Z.; Iyer, R.; Perpich, J.D.; Haque, N.; Cani, P.D.; de Vos, W.M.; Amar, S. Akkermansia muciniphila reduces Porphyromonas gingivalis-induced inflammation and periodontal bone destruction. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2020, 47, 202–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, B.; Xian, W.; Sun, Y.; Gou, L.; Guo, Q.; Zhou, X.; Ren, B.; Cheng, L. Akkermansia muciniphila inhibited the periodontitis caused by Fusobacterium nucleatum. NPJ Biofilms Microbiomes 2023, 9, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulhall, H.; DiChiara, J.M.; Huck, O.; Amar, S. Pasteurized Akkermansia muciniphila reduces periodontal and systemic inflammation induced by Porphyromonas gingivalis in lean and obese mice. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2022, 49, 717–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mulhall, H.; DiChiara, J.M.; Deragon, M.; Iyer, R.; Huck, O.; Amar, S. Akkermansia muciniphila and Its Pili-Like Protein Amuc_1100 Modulate Macrophage Polarization in Experimental Periodontitis. Infect. Immun. 2020, 89, e00500-20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, S.; Xiang, J.; Abedin, M.; Wang, J.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Wu, H.; Xiao, J. Characterization and Anti-Inflammatory Effects of Akkermansia muciniphila-Derived Extracellular Vesicles. Microorganisms 2025, 13, 464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, C.S.; Ban, M.; Choi, E.J.; Moon, H.G.; Jeon, J.S.; Kim, D.K.; Park, S.K.; Jeon, S.G.; Roh, T.Y.; Myung, S.J.; et al. Extracellular vesicles derived from gut microbiota, especially Akkermansia muciniphila, protect the progression of dextran sulfate sodium-induced colitis. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e76520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, Z.W.; Xia, K.; Liu, Y.W.; Liu, J.H.; Rao, S.S.; Hu, X.K.; Chen, C.Y.; Xu, R.; Wang, Z.X.; Xie, H. Extracellular Vesicles from Akkermansia muciniphila Elicit Antitumor Immunity Against Prostate Cancer via Modulation of CD8(+) T Cells and Macrophages. Int. J. Nanomed. 2021, 16, 2949–2963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamza, M.; Wang, S.; Wu, H.; Sun, J.; Du, Y.; Zeng, C.; Liu, Y.; Li, K.; Zhu, X.; Liu, H.; et al. Targeting copper homeostasis: Akkermansia-derived OMVs co-deliver Atox1 siRNA and elesclomol for cancer therapy. Acta Pharm. Sin. B 2025, 15, 2640–2654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, J.H.; Chen, C.Y.; Liu, Z.Z.; Luo, Z.W.; Rao, S.S.; Jin, L.; Wan, T.F.; Yue, T.; Tan, Y.J.; Yin, H.; et al. Extracellular Vesicles from Child Gut Microbiota Enter into Bone to Preserve Bone Mass and Strength. Adv. Sci. 2021, 8, 2004831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baddouri, L.; Hannig, M. Probiotics as an adjunctive therapy in periodontitis treatment-reality or illusion-a clinical perspective. NPJ Biofilms Microbiomes 2024, 10, 148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Homayouni Rad, A.; Pourjafar, H.; Mirzakhani, E. A comprehensive review of the application of probiotics and postbiotics in oral health. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2023, 13, 1120995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Ding, Y.; Guo, Q. Probiotic Species in the Management of Periodontal Diseases: An Overview. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2022, 12, 806463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bloch, S.; Hager-Mair, F.F.; Andrukhov, O.; Schäffer, C. Oral streptococci: Modulators of health and disease. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2024, 14, 1357631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Y.; Giardino Torchia, M.L.; Lawson, G.W.; Karp, C.L.; Ashwell, J.D.; Mazmanian, S.K. Outer membrane vesicles of a human commensal mediate immune regulation and disease protection. Cell Host Microbe 2012, 12, 509–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durant, L.; Stentz, R.; Noble, A.; Brooks, J.; Gicheva, N.; Reddi, D.; O’Connor, M.J.; Hoyles, L.; McCartney, A.L.; Man, R.; et al. Bacteroides thetaiotaomicron-derived outer membrane vesicles promote regulatory dendritic cell responses in health but not in inflammatory bowel disease. Microbiome 2020, 8, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López, P.; González-Rodríguez, I.; Sánchez, B.; Gueimonde, M.; Margolles, A.; Suárez, A. Treg-inducing membrane vesicles from Bifidobacterium bifidum LMG13195 as potential adjuvants in immunotherapy. Vaccine 2012, 30, 825–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, J.H.; Moon, C.M.; Shin, T.S.; Kim, E.K.; McDowell, A.; Jo, M.K.; Joo, Y.H.; Kim, S.E.; Jung, H.K.; Shim, K.N.; et al. Lactobacillusparacasei-derived extracellular vesicles attenuate the intestinal inflammatory response by augmenting the endoplasmic reticulum stress pathway. Exp. Mol. Med. 2020, 52, 423–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Mo, L.; Ou, J.; Fang, Q.; Wu, H.; Wu, Y.; Nandakumar, K.S. Proteus mirabilis Vesicles Induce Mitochondrial Apoptosis by Regulating miR96-5p/Abca1 to Inhibit Osteoclastogenesis and Bone Loss. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 833040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Xie, J.; Wang, Z.; Zhong, Y.; Liu, L.; Liu, J.; Zhang, W.; Pi, Y.; Tang, F.; Liu, Z.; et al. Androgen deficiency-induced loss of Lactobacillus salivarius extracellular vesicles is associated with the pathogenesis of osteoporosis. Microbiol. Res. 2025, 293, 128047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, H.; Zhou, J.; Wu, T. ECM stiffness-mediated regulation of glucose metabolism in MSCs osteogenic differentiation: Mechanisms, intersections, and implications. Oral Sci. Homeost. Med. 2025, 1, 9610025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, A.L.; Fonseca, S.; Miquel-Clopés, A.; Cross, K.; Kok, K.S.; Wegmann, U.; Gil-Cordoso, K.; Bentley, E.G.; Al Katy, S.H.M.; Coombes, J.L.; et al. Bioengineering commensal bacteria-derived outer membrane vesicles for delivery of biologics to the gastrointestinal and respiratory tract. J. Extracell. Vesicles 2019, 8, 1632100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hay, J.J.; Rodrigo-Navarro, A.; Petaroudi, M.; Bryksin, A.V.; García, A.J.; Barker, T.H.; Dalby, M.J.; Salmeron-Sanchez, M. Bacteria-Based Materials for Stem Cell Engineering. Adv. Mater. 2018, 30, e1804310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Li, H.; Wang, J.; Yao, M.; Peng, Y.; Liu, T.; Li, Z.; Luo, G.; Deng, J. Engineering Bacteria-Activated Multifunctionalized Hydrogel for Promoting Diabetic Wound Healing. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2021, 31, 2105749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Song, P.; Zhang, H.; Zhou, F.; Ji, N.; Wang, M.; Zhou, G.; Han, R.; Liu, X.; Weng, W.; et al. Synthetic biology-based bacterial extracellular vesicles displaying BMP-2 and CXCR4 to ameliorate osteoporosis. J. Extracell. Vesicles 2024, 13, e12429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moghaddam, Z.S.; Dehghan, A.; Halimi, S.; Najafi, F.; Nokhostin, A.; Naeini, A.E.; Akbarzadeh, I.; Ren, Q. Bacterial Extracellular Vesicles: Bridging Pathogen Biology and Therapeutic Innovation. Acta. Biomater. 2025, 200, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meng, F.; Li, L.; Zhang, Z.; Lin, Z.; Zhang, J.; Song, X.; Xue, T.; Xing, C.; Liang, X.; Zhang, X. Biosynthetic neoantigen displayed on bacteria derived vesicles elicit systemic antitumour immunity. J. Extracell. Vesicles 2022, 11, e12289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chronopoulos, A.; Kalluri, R. Emerging role of bacterial extracellular vesicles in cancer. Oncogene 2020, 39, 6951–6960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Wu, Y.; Wang, F.; Wang, S.; Ji, N.; Wang, M.; Zhou, G.; Han, R.; Liu, X.; Weng, W.; et al. Bone-targeted engineered bacterial extracellular vesicles delivering miRNA to treat osteoporosis. Compos. B Eng. 2023, 267, 111047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, M.; Chen, H.; Zeng, Y.; Lv, Z.; Hu, X.; Tong, Y.; Wang, P.; Zhao, M.; Mu, R.; Yu, J.; et al. DH5α Outer Membrane-Coated Biomimetic Nanocapsules Deliver Drugs to Brain Metastases but not Normal Brain Cells via Targeting GRP94. Small 2023, 19, e2300403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.; Ou, Z.; Pang, M.; Tao, Z.; Zheng, X.; Huang, Z.; Wen, D.; Li, Q.; Zhou, R.; Chen, P.; et al. Extracellular vesicles derived from Akkermansia muciniphila promote placentation and mitigate preeclampsia in a mouse model. J. Extracell. Vesicles 2023, 12, e12328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Fu, W.; Yang, N.; Yan, J.; Han, B.; Niu, Q.; Li, Z.; Bai, R.; Yu, T. Oral–Gut Microbial Crosstalk and Therapeutic Applications of Bacterial Extracellular Vesicles. Biomolecules 2026, 16, 26. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom16010026

Fu W, Yang N, Yan J, Han B, Niu Q, Li Z, Bai R, Yu T. Oral–Gut Microbial Crosstalk and Therapeutic Applications of Bacterial Extracellular Vesicles. Biomolecules. 2026; 16(1):26. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom16010026

Chicago/Turabian StyleFu, Wenmei, Ninghan Yang, Jiale Yan, Bing Han, Qin Niu, Zhengyu Li, Rushui Bai, and Tingting Yu. 2026. "Oral–Gut Microbial Crosstalk and Therapeutic Applications of Bacterial Extracellular Vesicles" Biomolecules 16, no. 1: 26. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom16010026

APA StyleFu, W., Yang, N., Yan, J., Han, B., Niu, Q., Li, Z., Bai, R., & Yu, T. (2026). Oral–Gut Microbial Crosstalk and Therapeutic Applications of Bacterial Extracellular Vesicles. Biomolecules, 16(1), 26. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom16010026