The PELP1 Pathway and Its Importance in Cancer Treatment

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. PELP1: Structure and Function

2.1. Overview of PELP1 Structure

2.2. PELP1 Post-Translational Modifications

2.3. PELP1 Interaction Partners

3. PELP1 Signaling Pathways

3.1. Genomic Functions

3.2. Non-Genomic Signaling

3.3. Cell Cycle

3.4. Chromatin Modifications

3.5. DNA Damage Response

3.6. Immune Signaling

3.7. Stem Cells

3.8. Ribosome

4. Role of PELP1 in Cancer

4.1. Breast Cancer (BCa)

4.2. Prostate Cancer (PCa)

4.3. Endometrial Cancer (ECa)

4.4. Ovarian Cancer (OCa)

4.5. Hepatocellular Carcinoma (HCC)

4.6. Colorectal Cancer (CRC)

4.7. Non-Small Cell Lung Carcinoma (NSCLC)

4.8. Gastric Cancer (GCa)

4.9. Medulloblastoma (MB)

4.10. Pancreatic Cancer

5. PELP1 as a Biomarker

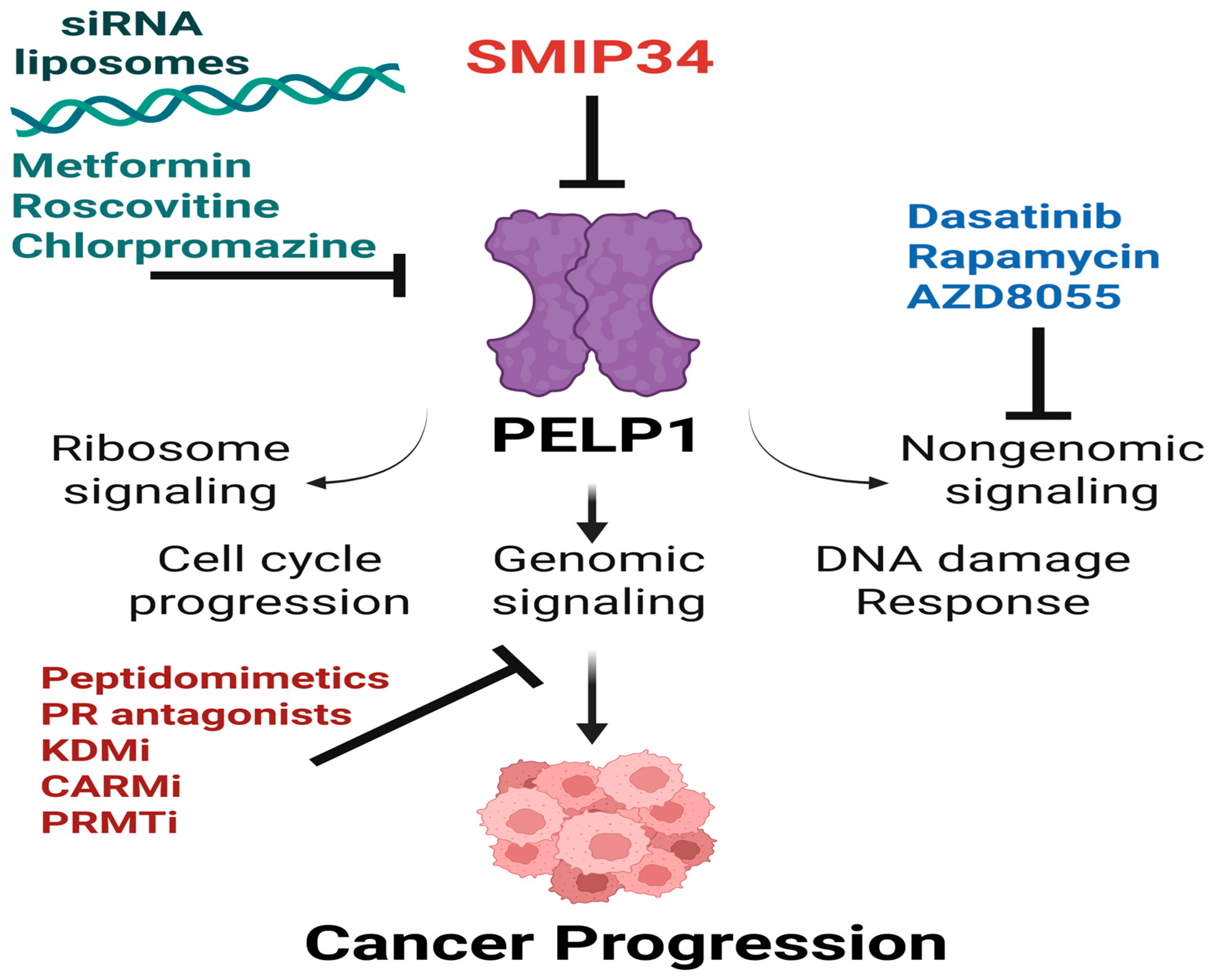

6. Therapeutic Targeting of PELP1

7. Conclusions and Future Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| PELP1 | Proline, Glutamic acid, and Leucine-rich Protein 1 |

| NRs | Nuclear Receptors |

| ER | Estrogen Receptor |

| ERα/ERβ | Estrogen Receptor alpha/beta |

| AR | Androgen Receptor |

| PR | Progesterone Receptor |

| GR | Glucocorticoid Receptor |

| RXR | Retinoid X Receptor |

| ERRα | Estrogen-Related Receptor alpha |

| STAT3 | Signal Transducer and Activator of Transcription 3 |

| NF-κB | Nuclear Factor Kappa-Light-Chain-Enhancer of Activated B Cells |

| SP1 | Specificity Protein 1 |

| AP1 | Activator Protein 1 |

| FHL2 | Four-and-a-Half LIM Domains Protein 2 |

| Src | Proto-oncogene tyrosine-protein kinase Src |

| PI3K | Phosphoinositide 3-Kinase |

| MAPK | Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase |

| mTOR | Mechanistic Target of Rapamycin |

| GSK3β | Glycogen Synthase Kinase 3 Beta |

| ATM/ATR/DNA-PKcs | DNA Damage Response Kinases |

| CDK | Cyclin-Dependent Kinase |

| PKA | Protein Kinase A |

| ILK1 | Integrin-Linked Kinase 1 |

| HDAC2 | Histone Deacetylase 2 |

| KDM1A/LSD1 | Lysine-Specific Demethylase 1 |

| CBP/p300 | CREB-Binding Protein/E1A Binding Protein p300 |

| CARM1 | Coactivator-Associated Arginine Methyltransferase 1 |

| PRMT6 | Protein Arginine Methyltransferase 6 |

| SETDB1 | SET Domain Bifurcated Histone Lysine Methyltransferase 1 |

| macroH2A1 | Histone Variant MacroH2A1 |

| SC35 | Splicing Component 35 |

| SLiM | Short Linear Motif |

| GAR | Glutamic Acid-Rich Region |

| NLS | Nuclear Localization Signal |

| SH3/SH2 | Src Homology Domains 3/2 |

| SUMO | Small Ubiquitin-like Modifier |

| TTLL4 | Tubulin Tyrosine Ligase-Like Family Member 4 |

| MDN1 | Midasin AAA ATPase 1 |

| WDR18/TEX10/LAS1L/NOL9/SENP3 | Rixosome Complex Components |

| DDR | DNA Damage Response |

| EMT | Epithelial–Mesenchymal Transition |

| HER2 | Human Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor 2 |

| HRS | Hepatocyte Growth Factor-Regulated Tyrosine Kinase Substrate |

| PFKFB3/PFKFB4 | 6-Phosphofructo-2-Kinase/Fructose-2,6-Bisphosphatase 3/4 |

| CTC | Circulating Tumor Cell |

| TNBC | Triple-Negative Breast Cancer |

| MTp53/WTp53 | Mutant/Wild-Type p53 |

| VEGFA | Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor A |

| TME | Tumor Microenvironment |

| GM-CSF | Granulocyte–Macrophage Colony-Stimulating Factor |

| IKK | IκB Kinase |

| Treg | Regulatory T Cell |

| PD-L1/CTLA4 | Immune Checkpoints |

| RUNX2 | Runt-Related Transcription Factor 2 |

| rRNA | Ribosomal RNA |

| Cryo-EM | Cryogenic Electron Microscopy |

| SMIP34 | Small Molecule Inhibitor of PELP1 |

| CPZ | Chlorpromazine |

| TKI | Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitor |

| ESCC | Esophageal Squamous Cell Carcinoma |

| BCa/PCa/ECa/OCa/HCC/CRC/GCa/MB | Breast/Prostate/Endometrial/Ovarian/Hepatocellular/Colorectal/Gastric/Medulloblastoma Cancer |

| NSCLC | Non-Small Cell Lung Carcinoma |

| ERE | Estrogen Response Element |

| DHT | Dihydrotestosterone |

References

- Ravindranathan, P.; Lange, C.A.; Raj, G.V. Minireview: Deciphering the Cellular Functions of PELP1. Mol. Endocrinol. 2015, 29, 1222–1229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajhans, R.; Nair, S.; Holden, A.H.; Kumar, R.; Tekmal, R.R.; Vadlamudi, R.K. Oncogenic potential of the nuclear receptor coregulator proline-, glutamic acid-, leucine-rich protein 1/modulator of the nongenomic actions of the estrogen receptor. Cancer Res. 2007, 67, 5505–5512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nair, S.S.; Guo, Z.; Mueller, J.M.; Koochekpour, S.; Qiu, Y.; Tekmal, R.R.; Schule, R.; Kung, H.J.; Kumar, R.; Vadlamudi, R.K. Proline-, glutamic acid-, and leucine-rich protein-1/modulator of nongenomic activity of estrogen receptor enhances androgen receptor functions through LIM-only coactivator, four-and-a-half LIM-only protein 2. Mol. Endocrinol. 2007, 21, 613–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sareddy, G.R.; Zhang, Q.; Wang, R.; Scott, E.; Zou, Y.; O’Connor, J.C.; Chen, Y.; Dong, Y.; Vadlamudi, R.K.; Brann, D. Proline-, glutamic acid-, and leucine-rich protein 1 mediates estrogen rapid signaling and neuroprotection in the brain. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2015, 112, E6673–E6682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Zhang, X.-Y.; Liao, N.-Q.; He, Z.-H.; Chen, Q.-F. Identification of ribosome biogenesis genes and subgroups in ischaemic stroke. Front. Immunol. 2024, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordon, J.; Kaminski, A.M.; Bommu, S.R.; Skrajna, A.; Petrovich, R.M.; Pedersen, L.C.; McGinty, R.K.; Warren, A.J.; Stanley, R.E. PELP1 coordinates the modular assembly and enzymatic activity of the rixosome complex. Sci. Adv. 2025, 11, eadw4603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Altwegg, K.A.; Vadlamudi, R.K. Role of estrogen receptor coregulators in endocrine resistant breast cancer. Explor. Target. Anti-tumor Ther. 2021, 2, 385–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nassar, K.M.; Yang, X.; Baker, A.; Gopalam, R.; Arnold, W.C.; Adeniran, T.T.; Hernandez Fernandez, M.H.; Mahajan, M.; Lai, Z.; Chen, Y.; et al. PELP1 Is a Novel Therapeutic Target in Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Cancer Res. Commun. 2024, 4, 2610–2620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unni, E.; Sun, S.; Nan, B.; McPhaul, M.J.; Cheskis, B.; Mancini, M.A.; Marcelli, M. Changes in androgen receptor nongenotropic signaling correlate with transition of LNCaP cells to androgen independence. Cancer Res. 2004, 64, 7156–7168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barletta, F.; Wong, C.W.; McNally, C.; Komm, B.S.; Katzenellenbogen, B.; Cheskis, B.J. Characterization of the interactions of estrogen receptor and MNAR in the activation of cSrc. Mol. Endocrinol. 2004, 18, 1096–1108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sareddy, G.R.; Vadlamudi, R.K. PELP1: Structure, biological function and clinical significance. Gene 2016, 585, 128–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vadlamudi, R.K.; Wang, R.A.; Mazumdar, A.; Kim, Y.; Shin, J.; Sahin, A.; Kumar, R. Molecular cloning and characterization of PELP1, a novel human coregulator of estrogen receptor alpha. J. Biol. Chem. 2001, 276, 38272–38279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonugunta, V.K.; Nair, B.C.; Rajhans, R.; Sareddy, G.R.; Nair, S.S.; Vadlamudi, R.K. Regulation of rDNA transcription by proto-oncogene PELP1. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e21095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mann, M.; Zou, Y.; Chen, Y.; Brann, D.; Vadlamudi, R. PELP1 oncogenic functions involve alternative splicing via PRMT6. Mol. Oncol. 2014, 8, 389–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nair, B.C.; Nair, S.S.; Chakravarty, D.; Challa, R.; Manavathi, B.; Yew, P.R.; Kumar, R.; Tekmal, R.R.; Vadlamudi, R.K. Cyclin-dependent kinase-mediated phosphorylation plays a critical role in the oncogenic functions of PELP1. Cancer Res. 2010, 70, 7166–7175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nagpal, J.K.; Nair, S.; Chakravarty, D.; Rajhans, R.; Pothana, S.; Brann, D.W.; Tekmal, R.R.; Vadlamudi, R.K. Growth factor regulation of estrogen receptor coregulator PELP1 functions via Protein Kinase A pathway. Mol. Cancer Res. 2008, 6, 851–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krishnan, S.R.; Nair, B.C.; Sareddy, G.R.; Roy, S.S.; Natarajan, M.; Suzuki, T.; Peng, Y.; Raj, G.; Vadlamudi, R.K. Novel role of PELP1 in regulating chemotherapy response in mutant p53-expressing triple negative breast cancer cells. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2015, 150, 487–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finkbeiner, E.; Haindl, M.; Raman, N.; Muller, S. SUMO routes ribosome maturation. Nucleus 2011, 2, 527–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segala, G.; Bennesch, M.A.; Ghahhari, N.M.; Pandey, D.P.; Echeverria, P.C.; Karch, F.; Maeda, R.K.; Picard, D. Vps11 and Vps18 of Vps-C membrane traffic complexes are E3 ubiquitin ligases and fine-tune signalling. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 1833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kashiwaya, K.; Nakagawa, H.; Hosokawa, M.; Mochizuki, Y.; Ueda, K.; Piao, L.; Chung, S.; Hamamoto, R.; Eguchi, H.; Ohigashi, H.; et al. Involvement of the tubulin tyrosine ligase-like family member 4 polyglutamylase in PELP1 polyglutamylation and chromatin remodeling in pancreatic cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2010, 70, 4024–4033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ning, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, H.; Wu, J.; Song, T.; Wu, Q.; Liu, F. PELP1 suppression inhibits colorectal cancer through c-Src downregulation. Oxid. Med. Cell Longev. 2014, 2014, 193523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nair, B.C.; Krishnan, S.R.; Sareddy, G.R.; Mann, M.; Xu, B.; Natarajan, M.; Hasty, P.; Brann, D.; Tekmal, R.R.; Vadlamudi, R.K. Proline, glutamic acid and leucine-rich protein-1 is essential for optimal p53-mediated DNA damage response. Cell Death Differ. 2014, 21, 1409–1418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vadlamudi, R.K.; Balasenthil, S.; Broaddus, R.R.; Gustafsson, J.A.; Kumar, R. Deregulation of estrogen receptor coactivator proline-, glutamic acid-, and leucine-rich protein-1/modulator of nongenomic activity of estrogen receptor in human endometrial tumors. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2004, 89, 6130–6138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravindranathan, P.; Lee, T.K.; Yang, L.; Centenera, M.M.; Butler, L.; Tilley, W.D.; Hsieh, J.T.; Ahn, J.M.; Raj, G.V. Peptidomimetic targeting of critical androgen receptor-coregulator interactions in prostate cancer. Nat. Commun. 2013, 4, 1923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daniel, A.R.; Gaviglio, A.L.; Knutson, T.P.; Ostrander, J.H.; D’Assoro, A.B.; Ravindranathan, P.; Peng, Y.; Raj, G.V.; Yee, D.; Lange, C.A. Progesterone receptor-B enhances estrogen responsiveness of breast cancer cells via scaffolding PELP1- and estrogen receptor-containing transcription complexes. Oncogene 2015, 34, 506–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kayahara, M.; Ohanian, J.; Ohanian, V.; Berry, A.; Vadlamudi, R.; Ray, D.W. MNAR functionally interacts with both NH2- and COOH-terminal GR domains to modulate transactivation. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 2008, 295, E1047–E1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Rajhans, R.; Nair, H.B.; Nair, S.S.; Cortez, V.; Ikuko, K.; Kirma, N.B.; Zhou, D.; Holden, A.E.; Brann, D.W.; Chen, S.; et al. Modulation of in situ estrogen synthesis by proline-, glutamic acid-, and leucine-rich protein-1: Potential estrogen receptor autocrine signaling loop in breast cancer cells. Mol. Endocrinol. 2008, 22, 649–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, R.R.; Gururaj, A.E.; Vadlamudi, R.K.; Kumar, R. 9-cis-retinoic acid up-regulates expression of transcriptional coregulator PELP1, a novel coactivator of the retinoid X receptor alpha pathway. J. Biol. Chem. 2006, 281, 15394–15404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, Y.B.; Ko, J.K.; Shin, J. The transcriptional corepressor, PELP1, recruits HDAC2 and masks histones using two separate domains. J. Biol. Chem. 2004, 279, 50930–50941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manavathi, B.; Nair, S.S.; Wang, R.A.; Kumar, R.; Vadlamudi, R.K. Proline-, glutamic acid-, and leucine-rich protein-1 is essential in growth factor regulation of signal transducers and activators of transcription 3 activation. Cancer Res. 2005, 65, 5571–5577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Girard, B.J.; Daniel, A.R.; Lange, C.A.; Ostrander, J.H. PELP1: A review of PELP1 interactions, signaling, and biology. Mol. Cell Endocrinol. 2014, 382, 642–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vadlamudi, R.K.; Manavathi, B.; Balasenthil, S.; Nair, S.S.; Yang, Z.; Sahin, A.A.; Kumar, R. Functional implications of altered subcellular localization of PELP1 in breast cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2005, 65, 7724–7732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chakravarty, D.; Nair, S.S.; Santhamma, B.; Nair, B.C.; Wang, L.; Bandyopadhyay, A.; Agyin, J.K.; Brann, D.; Sun, L.Z.; Yeh, I.T.; et al. Extranuclear functions of ER impact invasive migration and metastasis by breast cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2010, 70, 4092–4101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thakkar, R.; Sareddy, G.R.; Zhang, Q.; Wang, R.; Vadlamudi, R.K.; Brann, D. PELP1: A key mediator of oestrogen signalling and actions in the brain. J. Neuroendocrinol. 2018, 30, e12484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Z.; Liu, J.; Ebrahimi, B.; Pratap, U.P.; He, Y.; Altwegg, K.A.; Tang, W.; Li, X.; Lai, Z.; Chen, Y.; et al. SETDB1 interactions with PELP1 contributes to breast cancer endocrine therapy resistance. Breast Cancer Res. 2022, 24, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hussey, K.M.; Chen, H.; Yang, C.; Park, E.; Hah, N.; Erdjument-Bromage, H.; Tempst, P.; Gamble, M.J.; Kraus, W.L. The histone variant MacroH2A1 regulates target gene expression in part by recruiting the transcriptional coregulator PELP1. Mol. Cell Biol. 2014, 34, 2437–2449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mann, M.; Cortez, V.; Vadlamudi, R. PELP1 oncogenic functions involve CARM1 regulation. Carcinogenesis 2013, 34, 1468–1475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mann, M.; Cortez, V.; Vadlamudi, R.K. Epigenetics of estrogen receptor signaling: Role in hormonal cancer progression and therapy. Cancers 2011, 3, 1691–1707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, S.S.; Gonugunta, V.K.; Bandyopadhyay, A.; Rao, M.K.; Goodall, G.J.; Sun, L.Z.; Tekmal, R.R.; Vadlamudi, R.K. Significance of PELP1/HDAC2/miR-200 regulatory network in EMT and metastasis of breast cancer. Oncogene 2014, 33, 3707–3716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nair, S.S.; Nair, B.C.; Cortez, V.; Chakravarty, D.; Metzger, E.; Schule, R.; Brann, D.W.; Tekmal, R.R.; Vadlamudi, R.K. PELP1 is a reader of histone H3 methylation that facilitates oestrogen receptor-alpha target gene activation by regulating lysine demethylase 1 specificity. EMBO Rep. 2010, 11, 438–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Truong, T.H.; Hu, H.; Temiz, N.A.; Hagen, K.M.; Girard, B.J.; Brady, N.J.; Schwertfeger, K.L.; Lange, C.A.; Ostrander, J.H. Cancer Stem Cell Phenotypes in ER(+) Breast Cancer Models Are Promoted by PELP1/AIB1 Complexes. Mol. Cancer Res. 2018, 16, 707–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordon, J.; Chapus, F.L.; Viverette, E.G.; Williams, J.G.; Deterding, L.J.; Krahn, J.M.; Borgnia, M.J.; Rodriguez, J.; Warren, A.J.; Stanley, R.E. Cryo-EM reveals the architecture of the PELP1-WDR18 molecular scaffold. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 6783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raman, N.; Weir, E.; Müller, S. The AAA ATPase MDN1 Acts as a SUMO-Targeted Regulator in Mammalian Pre-ribosome Remodeling. Mol. Cell 2016, 64, 607–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cermakova, K.; Hodges, H.C. Interaction modules that impart specificity to disordered protein. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2023, 48, 477–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, M.; Michael, S.; Alvarado-Valverde, J.; Zeke, A.; Lazar, T.; Glavina, J.; Nagy-Kanta, E.; Donagh, J.M.; Kalman, Z.E.; Pascarelli, S.; et al. ELM-the Eukaryotic Linear Motif resource-2024 update. Nucleic Acids Res. 2024, 52, D442–D455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennani-Baiti, I.M. Integration of ERα-PELP1-HER2 signaling by LSD1 (KDM1A/AOF2) offers combinatorial therapeutic opportunities to circumventing hormone resistance in breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res. 2012, 14, 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joung, I.; Strominger, J.L.; Shin, J. Molecular cloning of a phosphotyrosine-independent ligand of the p56lck SH2 domain. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1996, 93, 5991–5995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boonyaratanakornkit, V. Scaffolding proteins mediating membrane-initiated extra-nuclear actions of estrogen receptor. Steroids 2011, 76, 877–884. [Google Scholar]

- Zarif, J.C.; Miranti, C.K. The importance of non-nuclear AR signaling in prostate cancer progression and therapeutic resistance. Cell Signal 2016, 28, 348–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonugunta, V.K.; Sareddy, G.R.; Krishnan, S.R.; Cortez, V.; Roy, S.S.; Tekmal, R.R.; Vadlamudi, R.K. Inhibition of mTOR signaling reduces PELP1-mediated tumor growth and therapy resistance. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2014, 13, 1578–1588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Y.; Wang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Qiao, J.; Sasano, H.; McNamara, K.; Zhao, B.; Zhang, D.; Fan, Y.; Liu, L.; et al. Estradiol-Induced MMP-9 Expression via PELP1-Mediated Membrane-Initiated Signaling in ERα-Positive Breast Cancer Cells. Horm. Cancer 2020, 11, 87–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haas, D.; White, S.N.; Lutz, L.B.; Rasar, M.; Hammes, S.R. The modulator of nongenomic actions of the estrogen receptor (MNAR) regulates transcription-independent androgen receptor-mediated signaling: Evidence that MNAR participates in G protein-regulated meiosis in Xenopus laevis oocytes. Mol. Endocrinol. 2005, 19, 2035–2046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girard, B.J.; Regan Anderson, T.M.; Welch, S.L.; Nicely, J.; Seewaldt, V.L.; Ostrander, J.H. Cytoplasmic PELP1 and ERRgamma protect human mammary epithelial cells from Tam-induced cell death. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0121206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohshiro, K.; Rayala, S.K.; Kondo, S.; Gaur, A.; Vadlamudi, R.K.; El-Naggar, A.K.; Kumar, R. Identifying the Estrogen Receptor Coactivator PELP1 in Autophagosomes. Cancer Res. 2007, 67, 8164–8171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balasenthil, S.; Vadlamudi, R.K. Functional interactions between the estrogen receptor coactivator PELP1/MNAR and retinoblastoma protein. J. Biol. Chem. 2003, 278, 22119–22127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olsen, J.V.; Blagoev, B.; Gnad, F.; Macek, B.; Kumar, C.; Mortensen, P.; Mann, M. Global, in vivo, and site-specific phosphorylation dynamics in signaling networks. Cell 2006, 127, 635–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nair, S.S.; Mishra, S.K.; Yang, Z.; Balasenthil, S.; Kumar, R.; Vadlamudi, R.K. Potential role of a novel transcriptional coactivator PELP1 in histone H1 displacement in cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2004, 64, 6416–6423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Cortez, V.; Mann, M.; Tekmal, S.; Suzuki, T.; Miyata, N.; Rodriguez-Aguayo, C.; Lopez-Berestein, G.; Sood, A.K.; Vadlamudi, R.K. Targeting the PELP1-KDM1 axis as a potential therapeutic strategy for breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res. 2012, 14, R108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fanis, P.; Gillemans, N.; Aghajanirefah, A.; Pourfarzad, F.; Demmers, J.; Esteghamat, F.; Vadlamudi, R.K.; Grosveld, F.; Philipsen, S.; van Dijk, T.B. Five friends of methylated chromatin target of protein-arginine-methyltransferase[prmt]-1 (chtop), a complex linking arginine methylation to desumoylation. Mol. Cell Proteom. 2012, 11, 1263–1273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skibinska, I.; Andrusiewicz, M.; Soin, M.; Jendraszak, M.; Urbaniak, P.; Jedrzejczak, P.; Kotwicka, M. Increased expression of PELP1 in human sperm is correlated with decreased semen quality. Asian J. Androl. 2018, 20, 425–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vuttaradhi, V.K.; Ezhil, I.; Ramani, D.; Kanumuri, R.; Raghavan, S.; Balasubramanian, V.; Saravanan, R.; Kanakarajan, A.; Joseph, L.D.; Pitani, R.S.; et al. Inflammation-induced PELP1 expression promotes tumorigenesis by activating GM-CSF paracrine secretion in the tumor microenvironment. J. Biol. Chem. 2022, 298, 101406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.; Li, M.; Pratap, U.P.; Viswanadhapalli, S.; Liu, J.; Venkata, P.P.; Altwegg, K.A.; Palacios, B.E.; Li, X.; Chen, Y.; et al. PELP1 signaling contributes to medulloblastoma progression by regulating the NF-κB pathway. Mol. Carcinog. 2020, 59, 281–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girard, B.J.; Knutson, T.P.; Kuker, B.; McDowell, L.; Schwertfeger, K.L.; Ostrander, J.H. Cytoplasmic Localization of Proline, Glutamic Acid, Leucine-rich Protein 1 (PELP1) Induces Breast Epithelial Cell Migration through Up-regulation of Inhibitor of κB Kinase ϵ and Inflammatory Cross-talk with Macrophages. J. Biol. Chem. 2017, 292, 339–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Yin, W.; Liang, L. PELP1 is overexpressed in lung cancer and promotes tumor cell malignancy and resistance to tyrosine kinase inhibitor drug. Pathol. Res. Pract. 2022, 237, 154065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Y.; Liu, Y.; Lu, R. PELP1 promotes the expression of RUNX2 via the ERK pathway during the osteogenic differentiation of human periodontal ligament stem cells. Arch. Oral. Biol. 2021, 124, 105078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, S.P.; Denicourt, C. The impact of ribosome biogenesis in cancer: From proliferation to metastasis. NAR Cancer 2024, 6, zcae017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castle, C.D.; Cassimere, E.K.; Denicourt, C. LAS1L interacts with the mammalian Rix1 complex to regulate ribosome biogenesis. Mol. Biol. Cell 2012, 23, 716–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.; Stein, C.B.; Shafiq, T.A.; Shipkovenska, G.; Kalocsay, M.; Paulo, J.A.; Zhang, J.; Luo, Z.; Gygi, S.P.; Adelman, K.; et al. Rixosomal RNA degradation contributes to silencing of Polycomb target genes. Nature 2022, 604, 167–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.; Feng, W.; Yu, J.; Shafiq, T.A.; Paulo, J.A.; Zhang, J.; Luo, Z.; Gygi, S.P.; Moazed, D. SENP3 and USP7 regulate Polycomb-rixosome interactions and silencing functions. Cell Rep. 2023, 42, 112339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Tong, L. Molecular insights into the overall architecture of human rixosome. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 3288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nair, S.; Vadlamudi, R.K. Emerging significance of ER-coregulator PELP1/MNAR in cancer. Histol. Histopathol. 2007, 22, 91–96. [Google Scholar]

- Flageng, M.H.; Knappskog, S.; Gjerde, J.; Lonning, P.E.; Mellgren, G. Estrogens Correlate with PELP1 Expression in ER Positive Breast Cancer. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0134351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, S.K.; Balasenthil, S.; Nguyen, D.; Vadlamudi, R.K. Cloning and functional characterization of PELP1/MNAR promoter. Gene 2004, 330, 115–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rayala, S.K.; Hollander, P.; Balasenthil, S.; Molli, P.R.; Bean, A.J.; Vadlamudi, R.K.; Wang, R.A.; Kumar, R. Hepatocyte growth factor-regulated tyrosine kinase substrate (HRS) interacts with PELP1 and activates MAPK. J. Biol. Chem. 2006, 281, 4395–4403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostrander, J.H.; Truong, T.; Trousdell, M.; Hagen, K.; Temiz, N.A.; Ciccone, M.; Dewji, F.I.; Santos, C.d.; Lange, C.A. Abstract 1425: Transcriptional and epigenomic landscape of paclitaxel resistant MCF-7 cells. Cancer Res. 2025, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Truong, T.H.; Benner, E.A.; Hagen, K.M.; Temiz, N.A.; Kerkvliet, C.P.; Wang, Y.; Cortes-Sanchez, E.; Yang, C.H.; Trousdell, M.C.; Pengo, T.; et al. PELP1/SRC-3-dependent regulation of metabolic PFKFB kinases drives therapy resistant ER(+) breast cancer. Oncogene 2021, 40, 4384–4397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Altwegg, K.A.; Liu, J.; Weintraub, S.T.; Chen, Y.; Lai, Z.; Sareddy, G.R.; Viswanadhapalli, S.; Vadlamudi, R.K. Global Genomic and Proteomic Analysis Identified Critical Pathways Modulated by Proto-Oncogene PELP1 in TNBC. Cancers 2022, 14, 930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, S.; Chakravarty, D.; Cortez, V.; De Mukhopadhyay, K.; Bandyopadhyay, A.; Ahn, J.M.; Raj, G.V.; Tekmal, R.R.; Sun, L.; Vadlamudi, R.K. Significance of PELP1 in ER-negative breast cancer metastasis. Mol. Cancer Res. 2012, 10, 25–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, J.; Li, X. PELP1/MNAR suppression inhibits proliferation and metastasis of endometrial carcinoma cells. Oncol. Rep. 2012, 28, 2035–2042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Bellazzo, A.; Sicari, D.; Valentino, E.; Del Sal, G.; Collavin, L. Complexes formed by mutant p53 and their roles in breast cancer. Breast Cancer 2018, 10, 101–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regan Anderson, T.M.; Ma, S.H.; Raj, G.V.; Cidlowski, J.A.; Helle, T.M.; Knutson, T.P.; Krutilina, R.I.; Seagroves, T.N.; Lange, C.A. Breast Tumor Kinase (Brk/PTK6) Is Induced by HIF, Glucocorticoid Receptor, and PELP1-Mediated Stress Signaling in Triple-Negative Breast Cancer. Cancer Res. 2016, 76, 1653–1663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Ravindranathan, P.; Ramanan, M.; Kapur, P.; Hammes, S.R.; Hsieh, J.T.; Raj, G.V. Central role for PELP1 in nonandrogenic activation of the androgen receptor in prostate cancer. Mol. Endocrinol. 2012, 26, 550–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Marsaud, V.; Gougelet, A.; Maillard, S.; Renoir, J.M. Various phosphorylation pathways, depending on agonist and antagonist binding to endogenous estrogen receptor alpha (ERalpha), differentially affect ERalpha extractability, proteasome-mediated stability, and transcriptional activity in human breast cancer cells. Mol. Endocrinol. 2003, 17, 2013–2027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Schiff, R.; Massarweh, S.A.; Shou, J.; Bharwani, L.; Mohsin, S.K.; Osborne, C.K. Cross-talk between estrogen receptor and growth factor pathways as a molecular target for overcoming endocrine resistance. Clin. Cancer Res. 2004, 10, 331s–336s. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimple, C.; Nair, S.S.; Rajhans, R.; Pitcheswara, P.R.; Liu, J.; Balasenthil, S.; Le, X.F.; Burow, M.E.; Auersperg, N.; Tekmal, R.R.; et al. Role of PELP1/MNAR signaling in ovarian tumorigenesis. Cancer Res. 2008, 68, 4902–4909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakravarty, D.; Roy, S.S.; Babu, C.R.; Dandamudi, R.; Curiel, T.J.; Vivas-Mejia, P.; Lopez-Berestein, G.; Sood, A.K.; Vadlamudi, R.K. Therapeutic targeting of PELP1 prevents ovarian cancer growth and metastasis. Clin. Cancer Res. 2011, 17, 2250–2259, Erratum in Clin. Cancer Res. 2013, 19, 1305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, L.; Sun, C.; Mao, Y.; Huang, X.; Yang, X.; Huang, J.; Zhang, Y.; Li, C.; Yang, W.; Zhang, W.; et al. Effects of PELP1 on proliferation, metastasis and angiogenesis of epithelial ovarian cancer. Med. Oncol. 2025, 42, 379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Englert-Golon, M.; Andrusiewicz, M.; Żbikowska, A.; Chmielewska, M.; Sajdak, S.; Kotwicka, M. Altered Expression of ESR1, ESR2, PELP1 and c-SRC Genes Is Associated with Ovarian Cancer Manifestation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 6216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Wang, L.; Liu, F.; Pan, J.; Yao, Z.; Lin, Y.; Yang, Y.; Xiong, X.; Li, K.; Yang, Y.; et al. Targeting PELP1 Attenuates Angiogenesis and Enhances Chemotherapy Efficiency in Colorectal Cancer. Cancers 2022, 14, 383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, H.; Sun, Y.; Wu, Q.; Wu, Z.; Hu, M.; Sun, Y.; Liu, Y.; Ma, Z.; Liu, S.; Xiao, W.; et al. PELP1 Suppression Inhibits Gastric Cancer Through Downregulation of c-Src-PI3K-ERK Pathway. Front. Oncol. 2019, 9, 1423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habashy, H.O.; Powe, D.G.; Rakha, E.A.; Ball, G.; Macmillan, R.D.; Green, A.R.; Ellis, I.O. The prognostic significance of PELP1 expression in invasive breast cancer with emphasis on the ER-positive luminal-like subtype. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2010, 120, 603–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Dai, J.; McNamara, K.M.; Bai, B.; Shi, M.; Chan, M.S.; Liu, M.; Sasano, H.; Wang, X.; Li, X.; et al. Prognostic significance of proline, glutamic acid, leucine rich protein 1 (PELP1) in triple-negative breast cancer: A retrospective study on 129 cases. BMC Cancer 2015, 15, 699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Tsang, J.Y.S.; Lee, M.A.; Ni, Y.B.; Tong, J.H.; Chan, S.K.; Cheung, S.Y.; To, K.F.; Tse, G.M. The Clinical Value of PELP1 for Breast Cancer: A Comparison with Multiple Cancers and Analysis in Breast Cancer Subtypes. Cancer Res. Treat. 2019, 51, 706–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moustafa, M.; Ismael, M.; Mohamed, S.; Hafez, A.M. Value of Proline, Glutamic Acid, and Leucine-Rich Protein 1 and GATA Binding Protein 3 Expression in Breast Cancer: An Immunohistochemical study. Indian. J. Surg. 2023, 85, 608–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moustafa, M.; Ismael, M.; Mohamed, S.; Magdy, A. Diagnostic utility of PELP1 and GATA3 in primary and metastatic triple negative breast cancer. Rev. Senol. Y Patol. Mamar. 2022, 35, 153–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elmetwally, A.A.; Abdel-Hafeez, M.A.M.; Hammam, M.M.; Hafez, G.A.; Atwa, M.M.; El-Kherbetawy, M.K. Immunohistochemical study of proline, glutamic acid and leucine-rich protein 1 (PELP1) in correlation with guanine adenine thymine adenine family member 3 (GATA-3) receptors expression in breast carcinomas. Egypt. J. Pathol. 2023, 43, 53–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Truong, T.H.; Lange, C.A.; Ostrander, J.H. Targeting steroid receptor co-activators to inhibit breast cancer stem cells. Oncoscience 2018, 5, 281–282. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Wang, P.; Shi, M.; Sasano, H.; Chan, M.S.; Dai, J.; Guo, L.; Liu, M.; Wang, X.; Ma, Y.; et al. The pattern of proline, glutamic acid, and leucine-rich protein 1 expression in Chinese women with primary breast cancer. Int. J. Biol. Markers 2014, 29, e1–e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Dai, J.; Pan, Y.; Wang, X.; Qiao, J.; Sasano, H.; Zhao, B.; Mcnamara, K.; Guan, X.; Liu, L.; et al. Overexpression of PELP1 in Lung Adenocarcinoma Promoted E2 Induced Proliferation, Migration and Invasion of the Tumor Cells and Predicted a Worse Outcome of the Patients. Pathol. Oncol. Res. 2021, 27, 582443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Liu, Z.; Tang, W.; Pratap, U.P.; Collier, A.B.; Altwegg, K.A.; Gopalam, R.; Li, X.; Yuan, Y.; Zhou, D.; et al. PELP1 inhibition by SMIP34 reduces endometrial cancer progression via attenuation of ribosomal biogenesis. Mol. Oncol. 2022, 18, 2136–2156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aust, S.; Horak, P.; Pils, D.; Pils, S.; Grimm, C.; Horvat, R.; Tong, D.; Schmid, B.; Speiser, P.; Reinthaller, A.; et al. The prognostic value of estrogen receptor beta and proline-, glutamic acid- and leucine-rich protein 1 (PELP1) expression in ovarian cancer. BMC Cancer 2013, 13, 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonugunta, V.K.; Miao, L.; Sareddy, G.R.; Ravindranathan, P.; Vadlamudi, R.; Raj, G.V. The social network of PELP1 and its implications in breast and prostate cancers. Endocr. Relat. Cancer 2014, 21, T79–T86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Deng, Q.; Zhang, J.; Wang, X.; Liang, H. Integrative Analysis of Androgen Receptor Interactors Aberrations and Associated Prognostic Significance in Prostate Cancer. Urol. J. 2023, 20, 318–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grivas, P.D.; Tzelepi, V.; Sotiropoulou-Bonikou, G.; Kefalopoulou, Z.; Papavassiliou, A.G.; Kalofonos, H. Expression of ERalpha, ERbeta and co-regulator PELP1/MNAR in colorectal cancer: Prognostic significance and clinicopathologic correlations. Cell Oncol. 2009, 31, 235–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Slowikowski, B.K.; Galecki, B.; Dyszkiewicz, W.; Jagodzinski, P.P. Increased expression of proline-, glutamic acid- and leucine-rich protein PELP1 in non-small cell lung cancer. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2015, 73, 97–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.; Li, K.; Lin, X.; Yao, Z.; Wang, S.; Xiong, X.; Ning, Z.; Wang, J.; Xu, X.; Jiang, Y. Metformin induces human esophageal carcinoma cell pyroptosis by targeting the miR-497/PELP1 axis. Cancer Lett. 2019, 450, 22–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nair, B.C.; Vallabhaneni, S.; Tekmal, R.R.; Vadlamudi, R.K. Roscovitine confers tumor suppressive effect on therapy-resistant breast tumor cells. Breast Cancer Res. 2011, 13, R80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altwegg, K.A.; Viswanadhapalli, S.; Mann, M.; Chakravarty, D.; Krishnan, S.; Liu, Z.; Liu, J.; Pratap, U.P.; Ebrahimi, B.; Sanchez, J.R.; et al. A First-in-Class Inhibitor of ER Coregulator PELP1 Targets ER+ Breast Cancer. Cancer Res. 2022, 82, 3830–3844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Modification | Site | Enzyme/ Regulator | Functional Outcome | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phosphorylation | Ser477, Ser991 | CDKs | Enhances E2F1 activation, ER signaling | [15] |

| Phosphorylation | Ser350, Ser415, Ser613 | PKA (Growth factor signals) | Enhances co-activation, nuclear redistribution | [16] |

| Phosphorylation | Ser1033 | ATM, ATR, DNA-PKcs | DDR regulation, apoptosis regulation | [22] |

| Phosphorylation | Thr745, Ser1059 | GSK3β | Regulates PELP1 stability | [4] |

| SUMOylation | Not specified | SUMO (SENP3-regulated) | Regulates ribosome maturation and trafficking | [18] |

| Ubiquitination | Lys496 | Vps11/18 | Prevents c-Src interaction, blocks ERα phosphorylation | [19] |

| Polyglutamylation | Not specified | TTLL4 | Affects histone H3 affinity, chromatin remodeling | [20] |

| Phosphorylation | Tyr920 | c-Src | Reciprocal regulation with Src | [21] |

| Category | Interacting Proteins | Functional Role | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nuclear receptors (NRs) | ERα, ERβ, AR, PR, GR, ERRα, RXR | PELP1 acts as a co-activator for NRs via LXXLL motifs, facilitating transcriptional activation. | [12,23,24,25,26,27,28] |

| Transcription factors/coregulators | AP1, SP1, NF-κB, STAT3, FHL2 | PELP1 functions as a coregulator, modulating transcription factor-mediated signaling pathways. | [3,29,30] |

| Kinases and signaling proteins | c-Src, EGFR, PI3K, ILK1, CDK2, CDK4, PKA, mTOR, GSK3β, ATM, ATR | PELP1 acts as a scaffolding protein for kinases and is also phosphorylated by many kinases, affecting their localization, stability, and oncogenic signaling. | [10,11,15] |

| Chromatin modifiers | SETDB1, macroH2A1, CBP/p300, HDAC2, KDM1A/LSD1, p53, CARM1, PRMT6 | PELP1 binds histones and epigenetic enzymes and regulates chromatin structure and transcription by interacting with histone methyltransferases/demethylases and acetyltransferases. | [1,14,29,31,32,33,34,35,36] |

| Ribosome biogenesis complex | WDR18, TEX10, LAS1L, NOL9, SENP3, MDN1 | PELP1 is a component of the rixosome complex, critical for pre-60S ribosomal subunit maturation. Bridges enzymatic subunits and regulates SUMOylation and ATPase-driven maturation. | [5,6,37,38,39] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Nassar, K.M.; Subbarayalu, P.; Viswanadhapalli, S.; Vadlamudi, R.K. The PELP1 Pathway and Its Importance in Cancer Treatment. Biomolecules 2025, 15, 1729. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom15121729

Nassar KM, Subbarayalu P, Viswanadhapalli S, Vadlamudi RK. The PELP1 Pathway and Its Importance in Cancer Treatment. Biomolecules. 2025; 15(12):1729. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom15121729

Chicago/Turabian StyleNassar, Khaled Mohamed, Panneerdoss Subbarayalu, Suryavathi Viswanadhapalli, and Ratna K. Vadlamudi. 2025. "The PELP1 Pathway and Its Importance in Cancer Treatment" Biomolecules 15, no. 12: 1729. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom15121729

APA StyleNassar, K. M., Subbarayalu, P., Viswanadhapalli, S., & Vadlamudi, R. K. (2025). The PELP1 Pathway and Its Importance in Cancer Treatment. Biomolecules, 15(12), 1729. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom15121729