The Association Between the Eosinophilic COPD Phenotype with Overall Survival and Exacerbations in Patients on Long-Term Non-Invasive Ventilation

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design and Subjects

2.2. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Comparison of the High Eosinophil and Low Eosinophil Groups

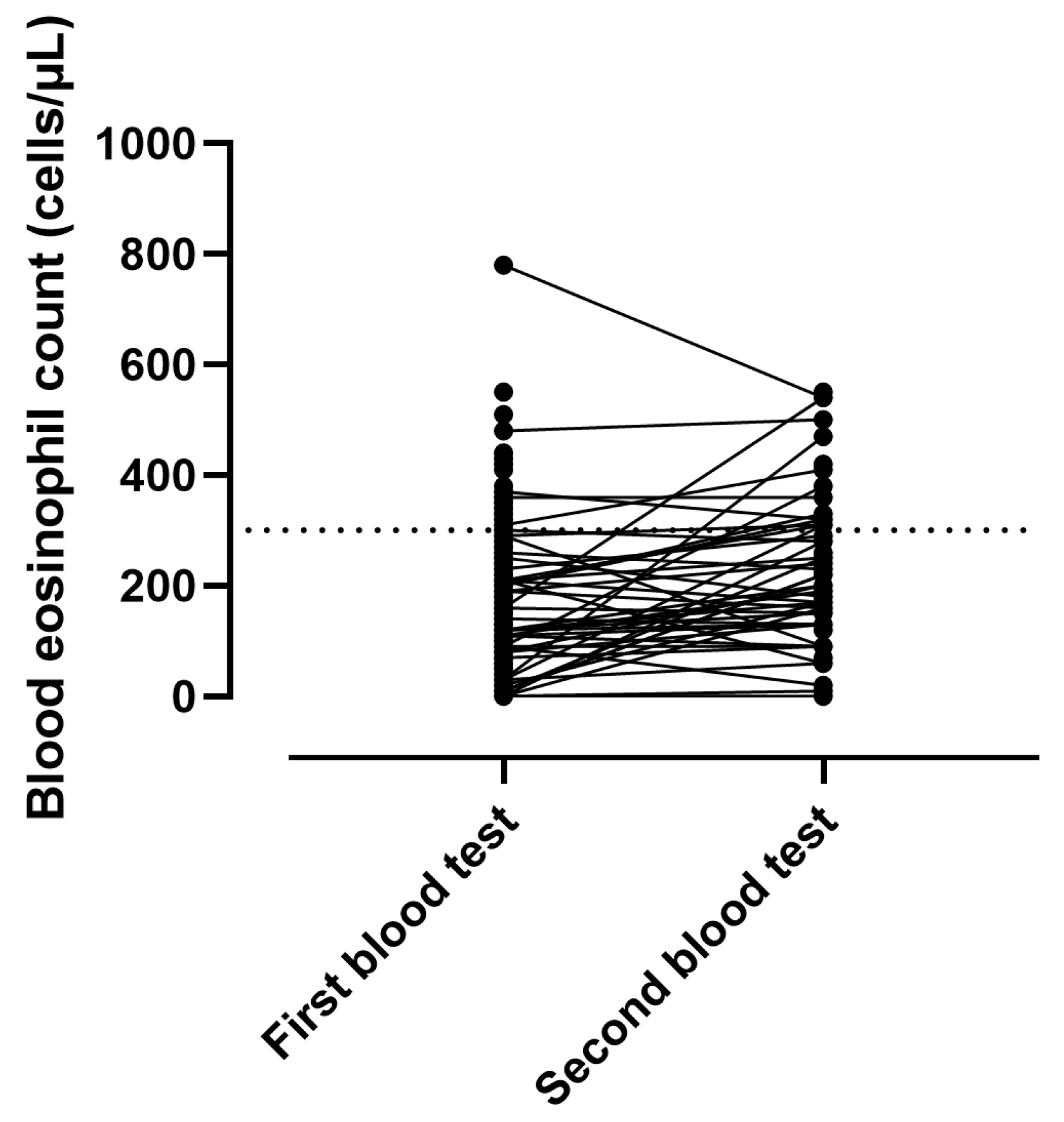

3.2. Stability of BEC at LT-NIV Setup

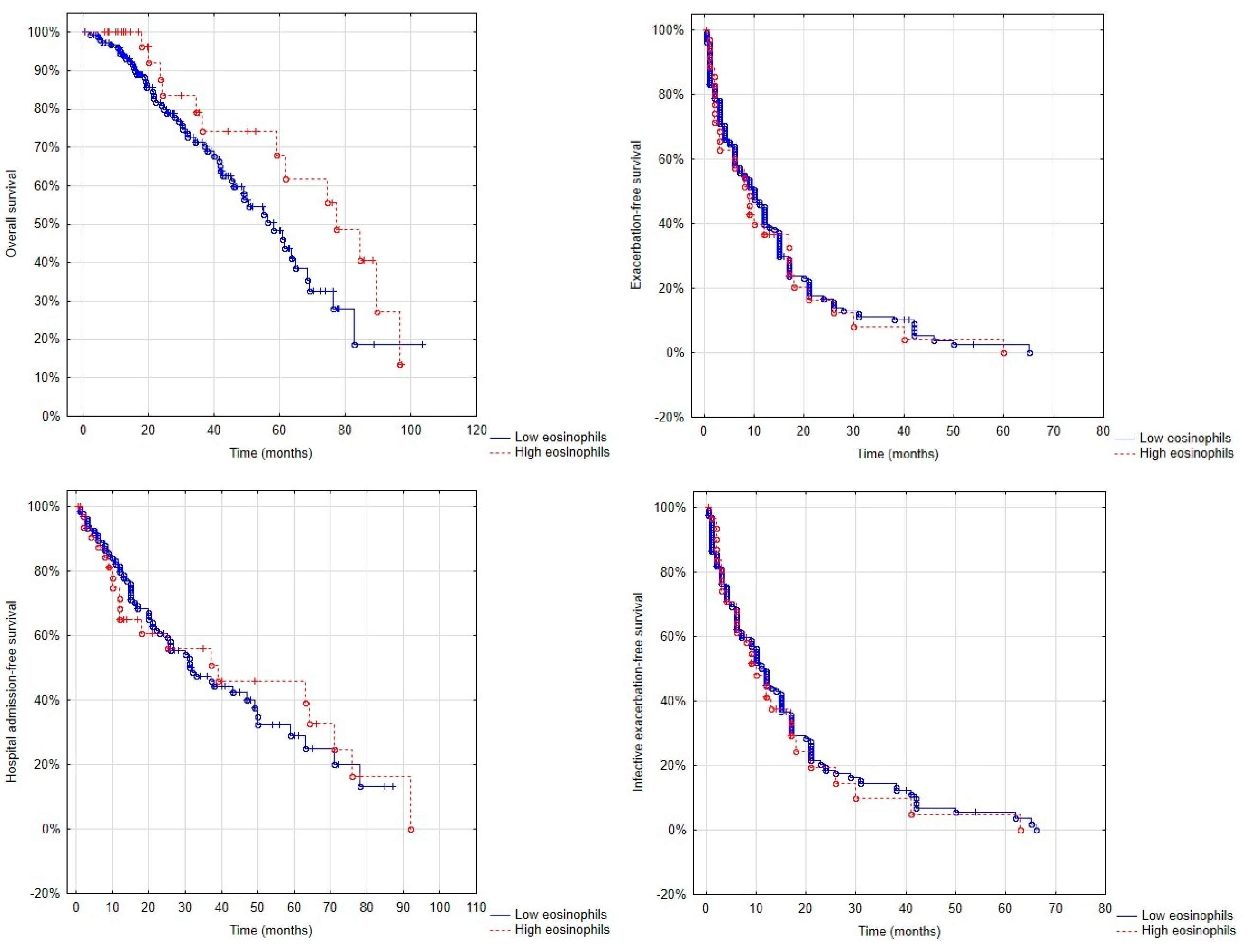

3.3. Overall Survival, Exacerbation-Free Survival and Hospitalisation-Free Survival in Patients with and Without the Eosinophilic Phenotype

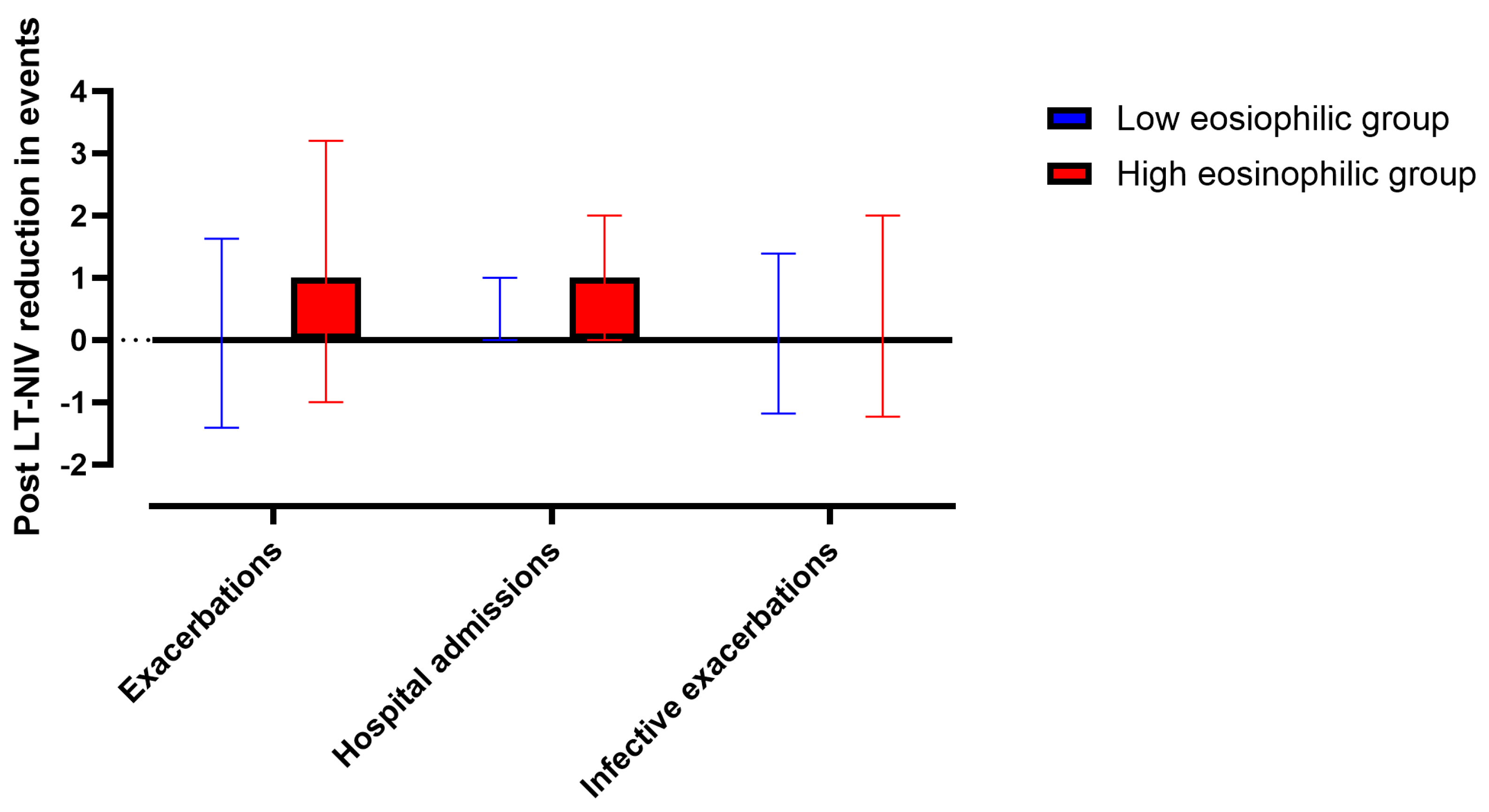

3.4. Changes in Exacerbations and Hospitalisations in Patients with High and Low BEC

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| BEC | Blood eosinophil count |

| BMI | Body mass index |

| CCI | Charlson Comorbidity Index |

| CFS | Clinical Frailty Score |

| COPD | Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease |

| EPAP | Expiratory positive airway pressure |

| FEV1 | Forced expiratory volume in 1 s |

| FVC | Forced vital capacity |

| ICSs | Inhaled corticosteroids |

| IL-4 | Interleukin-4 |

| IPAP | Inspiratory positive airway pressure |

| LABAs | Long-acting β-agonists |

| LAMAs | Long-acting muscarinic antagonists |

| LT-NIV | Long-term non-invasive ventilation |

| mMRC | Modified Medical Research Council Questionnaire |

| ODI | Oxygen desaturation index |

| PS | Pressure support |

| T90 | Percentage of time spent with oxygen saturation below 90% |

References

- Barnes, P.J.; Burney, P.G.; Silverman, E.K.; Celli, B.R.; Vestbo, J.; Wedzicha, J.A.; Wouters, E.F. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2015, 1, 15076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Roisin, R.; Drakulovic, M.; Rodríguez, D.A.; Roca, J.; Barberà, J.A.; Wagner, P.D. Ventilation-perfusion imbalance and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease staging severity. J. Appl. Physiol. 2009, 106, 1902–1908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersen, K.H.; Iversen, M.; Kjaergaard, J.; Mortensen, J.; Nielsen-Kudsk, J.E.; Bendstrup, E.; Videbaek, R.; Carlsen, J. Prevalence, predictors, and survival in pulmonary hypertension related to end-stage chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. J. Heart Lung Transplant. Off. Publ. Int. Soc. Heart Transplant. 2012, 31, 373–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, N.; Gates, K.L.; Trejo, H.; Favoreto, S., Jr.; Schleimer, R.P.; Sznajder, J.I.; Beitel, G.J.; Sporn, P.H. Elevated CO2 selectively inhibits interleukin-6 and tumor necrosis factor expression and decreases phagocytosis in the macrophage. FASEB J. Off. Publ. Fed. Am. Soc. Exp. Biol. 2010, 24, 2178–2190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmadi, Z.; Bornefalk-Hermansson, A.; Franklin, K.A.; Midgren, B.; Ekström, M.P. Hypo- and hypercapnia predict mortality in oxygen-dependent chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: A population-based prospective study. Respir. Res. 2014, 15, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Csoma, B.; Vulpi, M.R.; Dragonieri, S.; Bentley, A.; Felton, T.; Lázár, Z.; Bikov, A. Hypercapnia in COPD: Causes, Consequences, and Therapy. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 3180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, P.B.; Rehal, S.; Arbane, G.; Bourke, S.; Calverley, P.M.A.; Crook, A.M.; Dowson, L.; Duffy, N.; Gibson, G.J.; Hughes, P.D.; et al. Effect of Home Noninvasive Ventilation with Oxygen Therapy vs Oxygen Therapy Alone on Hospital Readmission or Death After an Acute COPD Exacerbation: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA 2017, 317, 2177–2186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Köhnlein, T.; Windisch, W.; Köhler, D.; Drabik, A.; Geiseler, J.; Hartl, S.; Karg, O.; Laier-Groeneveld, G.; Nava, S.; Schönhofer, B.; et al. Non-invasive positive pressure ventilation for the treatment of severe stable chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: A prospective, multicentre, randomised, controlled clinical trial. Lancet Respir. Med. 2014, 2, 698–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McEvoy, R.D.; Pierce, R.J.; Hillman, D.; Esterman, A.; Ellis, E.E.; Catcheside, P.G.; O’Donoghue, F.J.; Barnes, D.J.; Grunstein, R.R. Nocturnal non-invasive nasal ventilation in stable hypercapnic COPD: A randomised controlled trial. Thorax 2009, 64, 561–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Higham, A.; Beech, A.; Singh, D. The relevance of eosinophils in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: Inflammation, microbiome, and clinical outcomes. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2024, 116, 927–946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sivapalan, P.; Bikov, A.; Jensen, J.U. Using Blood Eosinophil Count as a Biomarker to Guide Corticosteroid Treatment for Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. Diagnostics 2021, 11, 236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Negewo, N.A.; McDonald, V.M.; Baines, K.J.; Wark, P.A.; Simpson, J.L.; Jones, P.W.; Gibson, P.G. Peripheral blood eosinophils: A surrogate marker for airway eosinophilia in stable COPD. Int. J. Chronic Obstr. Pulm. Dis. 2016, 11, 1495–1504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watz, H.; Tetzlaff, K.; Wouters, E.F.; Kirsten, A.; Magnussen, H.; Rodriguez-Roisin, R.; Vogelmeier, C.; Fabbri, L.M.; Chanez, P.; Dahl, R.; et al. Blood eosinophil count and exacerbations in severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease after withdrawal of inhaled corticosteroids: A post-hoc analysis of the WISDOM trial. Lancet Respir. Med. 2016, 4, 390–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavord, I.D.; Lettis, S.; Locantore, N.; Pascoe, S.; Jones, P.W.; Wedzicha, J.A.; Barnes, N.C. Blood eosinophils and inhaled corticosteroid/long-acting β-2 agonist efficacy in COPD. Thorax 2016, 71, 118–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vedel-Krogh, S.; Nielsen, S.F.; Lange, P.; Vestbo, J.; Nordestgaard, B.G. Blood Eosinophils and Exacerbations in Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. The Copenhagen General Population Study. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2016, 193, 965–974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bafadhel, M.; Peterson, S.; De Blas, M.A.; Calverley, P.M.; Rennard, S.I.; Richter, K.; Fagerås, M. Predictors of exacerbation risk and response to budesonide in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: A post-hoc analysis of three randomised trials. Lancet Respir. Med. 2018, 6, 117–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agustí, A.; Edwards, L.D.; Rennard, S.I.; MacNee, W.; Tal-Singer, R.; Miller, B.E.; Vestbo, J.; Lomas, D.A.; Calverley, P.M.; Wouters, E.; et al. Persistent systemic inflammation is associated with poor clinical outcomes in COPD: A novel phenotype. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e37483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casanova, C.; Celli, B.R.; de-Torres, J.P.; Martínez-Gonzalez, C.; Cosio, B.G.; Pinto-Plata, V.; de Lucas-Ramos, P.; Divo, M.; Fuster, A.; Peces-Barba, G.; et al. Prevalence of persistent blood eosinophilia: Relation to outcomes in patients with COPD. Eur. Respir. J. 2017, 50, 1701162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prudente, R.; Ferrari, R.; Mesquita, C.B.; Machado, L.H.S.; Franco, E.A.T.; Godoy, I.; Tanni, S.E. Peripheral Blood Eosinophils and Nine Years Mortality in COPD Patients. Int. J. Chronic Obstr. Pulm. Dis. 2021, 16, 979–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zysman, M.; Deslee, G.; Caillaud, D.; Chanez, P.; Escamilla, R.; Court-Fortune, I.; Nesme-Meyer, P.; Perez, T.; Paillasseur, J.L.; Pinet, C.; et al. Relationship between blood eosinophils, clinical characteristics, and mortality in patients with COPD. Int. J. Chronic Obstr. Pulm. Dis. 2017, 12, 1819–1824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, Y.M.; Lee, K.S.; Hong, Y.; Hwang, S.C.; Kim, J.Y.; Kim, D.K.; Yoo, K.H.; Lee, J.H.; Kim, T.H.; Lim, S.Y.; et al. Blood eosinophil count as a prognostic biomarker in COPD. Int. J. Chronic Obstr. Pulm. Dis. 2018, 13, 3589–3596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Locantore, N.; Haldar, K.; Ramsheh, M.Y.; Beech, A.S.; Ma, W.; Brown, J.R.; Tal-Singer, R.; Barer, M.R.; Bafadhel, M.; et al. Inflammatory Endotype-associated Airway Microbiome in Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease Clinical Stability and Exacerbations: A Multicohort Longitudinal Analysis. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2021, 203, 1488–1502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, W.; Liu, D.; Li, D.; Che, X.; Cui, G. Effects of hypercapnia on T cells in lung ischemia/reperfusion injury after lung transplantation. Exp. Biol. Med. 2014, 239, 1597–1605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quan, H.; Li, B.; Couris, C.M.; Fushimi, K.; Graham, P.; Hider, P.; Januel, J.M.; Sundararajan, V. Updating and validating the Charlson comorbidity index and score for risk adjustment in hospital discharge abstracts using data from 6 countries. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2011, 173, 676–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hastie, A.T.; Martinez, F.J.; Curtis, J.L.; Doerschuk, C.M.; Hansel, N.N.; Christenson, S.; Putcha, N.; Ortega, V.E.; Li, X.; Barr, R.G.; et al. Association of sputum and blood eosinophil concentrations with clinical measures of COPD severity: An analysis of the SPIROMICS cohort. Lancet Respir. Med. 2017, 5, 956–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, W.C.; Bourbeau, J.; Nadeau, G.; Wang, W.; Barnes, N.; Landis, S.H.; Kirby, M.; Hogg, J.C.; Sin, D.D. High eosinophil counts predict decline in FEV(1): Results from the CanCOLD study. Eur. Respir. J. 2021, 57, 2000838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bikov, A.; Lange, P.; Anderson, J.A.; Brook, R.D.; Calverley, P.M.A.; Celli, B.R.; Cowans, N.J.; Crim, C.; Dixon, I.J.; Martinez, F.J.; et al. FEV(1) is a stronger mortality predictor than FVC in patients with moderate COPD and with an increased risk for cardiovascular disease. Int. J. Chronic Obstr. Pulm. Dis. 2020, 15, 1135–1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurst, J.R.; Vestbo, J.; Anzueto, A.; Locantore, N.; Müllerova, H.; Tal-Singer, R.; Miller, B.; Lomas, D.A.; Agusti, A.; Macnee, W.; et al. Susceptibility to exacerbation in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 2010, 363, 1128–1138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soler-Cataluña, J.J.; Martínez-García, M.A.; Román Sánchez, P.; Salcedo, E.; Navarro, M.; Ochando, R. Severe acute exacerbations and mortality in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Thorax 2005, 60, 925–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Divo, M.; Cote, C.; de Torres, J.P.; Casanova, C.; Marin, J.M.; Pinto-Plata, V.; Zulueta, J.; Cabrera, C.; Zagaceta, J.; Hunninghake, G.; et al. Comorbidities and risk of mortality in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2012, 186, 155–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Celli, B.R.; Cote, C.G.; Marin, J.M.; Casanova, C.; Montes de Oca, M.; Mendez, R.A.; Pinto Plata, V.; Cabral, H.J. The body-mass index, airflow obstruction, dyspnea, and exercise capacity index in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 2004, 350, 1005–1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chai, A.; Csoma, B.; Lazar, Z.; Bentley, A.; Bikov, A. The Effect of Opioids and Benzodiazepines on Exacerbation Rate and Overall Survival in Patients with Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease on Long-Term Non-Invasive Ventilation. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 5624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavord, I.D.; Lettis, S.; Anzueto, A.; Barnes, N. Blood eosinophil count and pneumonia risk in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: A patient-level meta-analysis. Lancet Respir. Med. 2016, 4, 731–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steer, J.; Gibson, J.; Bourke, S.C. The DECAF Score: Predicting hospital mortality in exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Thorax 2012, 67, 970–976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saltürk, C.; Karakurt, Z.; Adiguzel, N.; Kargin, F.; Sari, R.; Celik, M.E.; Takir, H.B.; Tuncay, E.; Sogukpinar, O.; Ciftaslan, N.; et al. Does eosinophilic COPD exacerbation have a better patient outcome than non-eosinophilic in the intensive care unit? Int. J. Chronic Obstr. Pulm. Dis. 2015, 10, 1837–1846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kolsum, U.; Donaldson, G.C.; Singh, R.; Barker, B.L.; Gupta, V.; George, L.; Webb, A.J.; Thurston, S.; Brookes, A.J.; McHugh, T.D.; et al. Blood and sputum eosinophils in COPD; relationship with bacterial load. Respir. Res. 2017, 18, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oshagbemi, O.A.; Burden, A.M.; Braeken, D.C.W.; Henskens, Y.; Wouters, E.F.M.; Driessen, J.H.M.; Maitland-van der Zee, A.H.; de Vries, F.; Franssen, F.M.E. Stability of Blood Eosinophils in Patients with Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease and in Control Subjects, and the Impact of Sex, Age, Smoking, and Baseline Counts. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2017, 195, 1402–1404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abe, Y.; Suzuki, M.; Kimura, H.; Shimizu, K.; Takei, N.; Oguma, A.; Matsumoto-Sasaki, M.; Goudarzi, H.; Makita, H.; Nishimura, M.; et al. Blood eosinophil count variability in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and severe asthma. Allergol. Int. Off. J. Jpn. Soc. Allergol. 2023, 72, 402–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butt, N.M.; Lambert, J.; Ali, S.; Beer, P.A.; Cross, N.C.; Duncombe, A.; Ewing, J.; Harrison, C.N.; Knapper, S.; McLornan, D.; et al. Guideline for the investigation and management of eosinophilia. Br. J. Haematol. 2017, 176, 553–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, H.S.; Kim, S.K.; Kim, Y.H.; Kim, J.W.; Lee, S.H.; Yoon, H.K.; Rhee, C.K. The association between eosinophilic exacerbation and eosinophilic levels in stable COPD. BMC Pulm. Med. 2021, 21, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Csoma, B.; Bikov, A.; Tóth, F.; Losonczy, G.; Müller, V.; Lázár, Z. Blood eosinophils on hospital admission for COPD exacerbation do not predict the recurrence of moderate and severe relapses. ERJ Open Res. 2021, 7, 00543–2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kostikas, K.; Papathanasiou, E.; Papaioannou, A.I.; Bartziokas, K.; Papanikolaou, I.C.; Antonakis, E.; Makou, I.; Hillas, G.; Karampitsakos, T.; Papaioannou, O.; et al. Blood eosinophils as predictor of outcomes in patients hospitalized for COPD exacerbations: A prospective observational study. Biomark. Biochem. Indic. Expo. Response Susceptibility Chem. 2021, 26, 354–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ko, F.W.S.; Chan, K.P.; Ngai, J.; Ng, S.S.; Yip, W.H.; Ip, A.; Chan, T.O.; Hui, D.S.C. Blood eosinophil count as a predictor of hospital length of stay in COPD exacerbations. Respirology 2020, 25, 259–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipson, D.A.; Crim, C.; Criner, G.J.; Day, N.C.; Dransfield, M.T.; Halpin, D.M.G.; Han, M.K.; Jones, C.E.; Kilbride, S.; Lange, P.; et al. Reduction in All-Cause Mortality with Fluticasone Furoate/Umeclidinium/Vilanterol in Patients with Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2020, 201, 1508–1516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabe, K.F.; Martinez, F.J.; Ferguson, G.T.; Wang, C.; Singh, D.; Wedzicha, J.A.; Trivedi, R.; St Rose, E.; Ballal, S.; McLaren, J.; et al. Triple Inhaled Therapy at Two Glucocorticoid Doses in Moderate-to-Very-Severe COPD. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 383, 35–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pascoe, S.; Barnes, N.; Brusselle, G.; Compton, C.; Criner, G.J.; Dransfield, M.T.; Halpin, D.M.G.; Han, M.K.; Hartley, B.; Lange, P.; et al. Blood eosinophils and treatment response with triple and dual combination therapy in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: Analysis of the IMPACT trial. Lancet Respir. Med. 2019, 7, 745–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koarai, A.; Yamada, M.; Ichikawa, T.; Fujino, N.; Kawayama, T.; Sugiura, H. Triple versus LAMA/LABA combination therapy for patients with COPD: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Respir. Res. 2021, 22, 183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budweiser, S.; Jörres, R.A.; Riedl, T.; Heinemann, F.; Hitzl, A.P.; Windisch, W.; Pfeifer, M. Predictors of survival in COPD patients with chronic hypercapnic respiratory failure receiving noninvasive home ventilation. Chest 2007, 131, 1650–1658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meldrum, O.W.; Donaldson, G.C.; Narayana, J.K.; Ivan, F.X.; Jaggi, T.K.; Mac Aogáin, M.; Finney, L.J.; Allinson, J.P.; Wedzicha, J.A.; Chotirmall, S.H. Accelerated Lung Function Decline and Mucus-Microbe Evolution in Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2024, 210, 298–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Low Eosinophil Group (n = 154) | High Eosinophil Group (n = 37) | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 65.7 ± 9.3 | 64.4 ± 8.5 | 0.43 |

| Gender (female, %) | 60 | 57 | 0.69 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 31.7 ± 10.3 | 32.5 ± 9.5 | 0.67 |

| BMI > 30 kg/m2 (%) | 57 | 56 | 0.94 |

| BMI > 35 kg/m2 (%) | 38 | 35 | 0.81 |

| Number of exacerbations in the year before setup | 2/1–4/ | 4/2–8/ | 0.01 |

| Frequent exacerbations (≥2 exacerbations/year, %) | 73 | 79 | 0.47 |

| Number of hospital admissions in the year before setup | 1/0–2/ | 1/1–2/ | 0.04 |

| Number of infective exacerbations in the year before setup | 2/1–3/ | 3/1–5/ | 0.03 |

| Never/ex-/current smokers (%) | 1/30/69 | 3/29/68 | 0.80 |

| Cigarette pack years | 48.4 ± 24.9 | 44.0 ± 19.0 | 0.36 |

| mMRC | 3.7 ± 0.7 | 3.7 ± 0.7 | 0.96 |

| CFS | 4.9 ± 1.0 | 4.9 ± 1.2 | 0.94 |

| On ICS (%) | 83 | 92 | 0.17 |

| ICS dose (μg budesonide equivalent) | 800/200–800/ | 800/250–800/ | 0.52 |

| On LABAs (%) | 91 | 97 | 0.22 |

| On LAMAs (%) | 83 | 92 | 0.17 |

| On ICS/LABAs (%) | 11 | 6 | 0.34 |

| On LABA/LAMAs (%) | 10 | 6 | 0.40 |

| On ICS/LABA/LAMAs (%) | 72 | 86 | 0.06 |

| Not on fix triple combination (%) | 17 | 32 | |

| On fix BP/FF/GB (%) | 31 | 30 | |

| On fix FF/VT/UB (%) | 23 | 24 | |

| On fix B/FF/GB (%) | 1 | 0 | |

| On systemic corticosteroids (%) | 7 | 8 | 0.74 |

| BEC (cells/µL) | 140/90–200/ | 370/320–425/ | <0.01 |

| Capillary blood pH | 7.42 ± 0.06 | 7.41 ± 0.05 | 0.34 |

| Capillary blood pCO2 (kPa) | 7.46 ± 1.37 | 7.67 ± 1.05 | 0.40 |

| Capillary blood pO2 (kPa) | 7.79 ± 1.24 | 7.63 ± 0.86 | 0.49 |

| HCO3− (mmol/L) | 32.4 ± 4.17 | 32.7 ± 4.90 | 0.75 |

| FEV1 (L) | 1.00 ± 0.41 | 0.84 ± 0.32 | 0.05 |

| FEV1 (% predicted) | 41.2 ± 15.8 | 31.0 ± 15.2 | <0.01 |

| FVC (L) | 2.15 ± 2.06 | 1.99 ± 0.65 | 0.32 |

| FVC (% predicted) | 71.5 ± 19.5 | 67.9 ± 22.3 | 0.55 |

| ODI (events/hour) | 21.2 ± 26.4 | 20.1 ± 20.0 | 0.89 |

| T90 (%) | 69.2 ± 36.1 | 90.3 ± 15.6 | 0.04 |

| Low Eosinophil Group (n = 154) | High Eosinophil Group (n = 37) | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| CCI | 2.2 ± 1.5 | 2.5 ± 1.6 | 0.22 |

| Chronic heart failure (%) | 29.3 | 30.3 | 0.91 |

| Ischaemic heart disease (%) | 25.2 | 24.2 | 0.91 |

| Cerebrovascular disease (%) | 8.6 | 8.8 | 0.97 |

| Pulmonary hypertension (%) | 12.7 | 18.2 | 0.40 |

| Type 2 diabetes (%) | 31.1 | 44.1 | 0.15 |

| Chronic kidney disease (%) | 10.7 | 12.1 | 0.81 |

| Asthma (%) | 20.0 | 33.3 | 0.09 |

| Bronchiectasis (%) | 24.0 | 35.3 | 0.18 |

| Obstructive sleep apnoea (%) | 26.5 | 23.5 | 0.72 |

| Depression (%) | 32.0 | 33.3 | 0.88 |

| Anxiety (%) | 16.6 | 21.2 | 0.52 |

| Kyphoscoliosis (%) | 1.3 | 5.9 | 0.10 |

| Allergic rhinitis (%) | 7.1 | 0.0 | 0.09 |

| Eczema (%) | 1.9 | 0.0 | 0.16 |

| Allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis (%) | 0.6 | 0.0 | 0.62 |

| On opioids (%) | 46.8 | 45.9 | 0.93 |

| On benzodiazepines (%) | 18.8 | 16.2 | 0.71 |

| Low Eosinophil Group (n = 154) | High Eosinophil Group (n = 37) | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| IPAP (cmH2O) | 24.0 ± 4.5 | 25.2 ± 3.9 | 0.16 |

| EPAP (cmH2O) | 6.3 ± 2.2 | 5.9 ± 1.8 | 0.38 |

| PS (cmH2O) | 17.7 ± 4.4 | 18.7 ± 4.0 | 0.21 |

| Back-up rate (breath/min) | 14.4 ± 1.2 | 14.2 ± 1.1 | 0.36 |

| Prescribed hours of use | 9.5 ± 2.4 | 9.9 ± 3.5 | 0.40 |

| pCO2 < 7 kPa achieved during LT-NIV setup (%) | 79 | 75 | 0.68 |

| Normocapnia achieved during LT-NIV setup (%) | 36 | 29 | 0.44 |

| 10 months | 20 months | 30 months | 40 months | 50 months | 60 months | 70 Months | 80 Months | 90 Months | 100 months | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low eosinophil group | 89 | 61 | 47 | 34 | 21 | 14 | 7 | 2 | 1 | 1 |

| High eosinophil group | 89 | 59 | 51 | 41 | 38 | 30 | 27 | 16 | 5 | 0 |

| p value | 0.97 | 0.86 | 0.62 | 0.49 | 0.04 | 0.03 | <0.01 | <0.01 | 0.04 | 0.62 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bikov, A.; Csoma, B.; Chai, A.; Croft, E.; Lazar, Z.; Bentley, A. The Association Between the Eosinophilic COPD Phenotype with Overall Survival and Exacerbations in Patients on Long-Term Non-Invasive Ventilation. Biomolecules 2025, 15, 1728. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom15121728

Bikov A, Csoma B, Chai A, Croft E, Lazar Z, Bentley A. The Association Between the Eosinophilic COPD Phenotype with Overall Survival and Exacerbations in Patients on Long-Term Non-Invasive Ventilation. Biomolecules. 2025; 15(12):1728. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom15121728

Chicago/Turabian StyleBikov, Andras, Balazs Csoma, Andrew Chai, Eleonor Croft, Zsofia Lazar, and Andrew Bentley. 2025. "The Association Between the Eosinophilic COPD Phenotype with Overall Survival and Exacerbations in Patients on Long-Term Non-Invasive Ventilation" Biomolecules 15, no. 12: 1728. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom15121728

APA StyleBikov, A., Csoma, B., Chai, A., Croft, E., Lazar, Z., & Bentley, A. (2025). The Association Between the Eosinophilic COPD Phenotype with Overall Survival and Exacerbations in Patients on Long-Term Non-Invasive Ventilation. Biomolecules, 15(12), 1728. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom15121728