Cloning and Characterization of the Novel Endoglucanase Identified in Deep Subsurface Thermal Well of Biragzang (North Ossetia) by Metagenomic Analysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Bacterial Strains and Plasmids

2.2. Metagenomic Analysis of the Biragzang Thermal Well

2.2.1. Sampling Procedure

2.2.2. Extraction of Environmental DNA and Library Preparation and Sequencing

2.2.3. Bioinformatic Analysis: Identification of Novel Cellulase Gene in the Thermal Well Metagenome and Its Phylogenetic Analysis

2.3. Cloning and Expression of the Cellulase Gene (cel7465)

2.4. Protein Purification by Metal Affinity Chromatography (IMAC) and Size Exclusion Chromatography

2.5. Cellulase Enzyme Activity

2.6. Effect of Temperature, pH, Metal Ions, Chelator on Enzyme Activity and Thermostability of the Protein

3. Results

3.1. Metagenomic Analysis of Biragzang Thermal Well and Identification of cel7465 Candidate Gene

3.2. Expression and Purification of the Cel7564 Glycoside Hydrolase

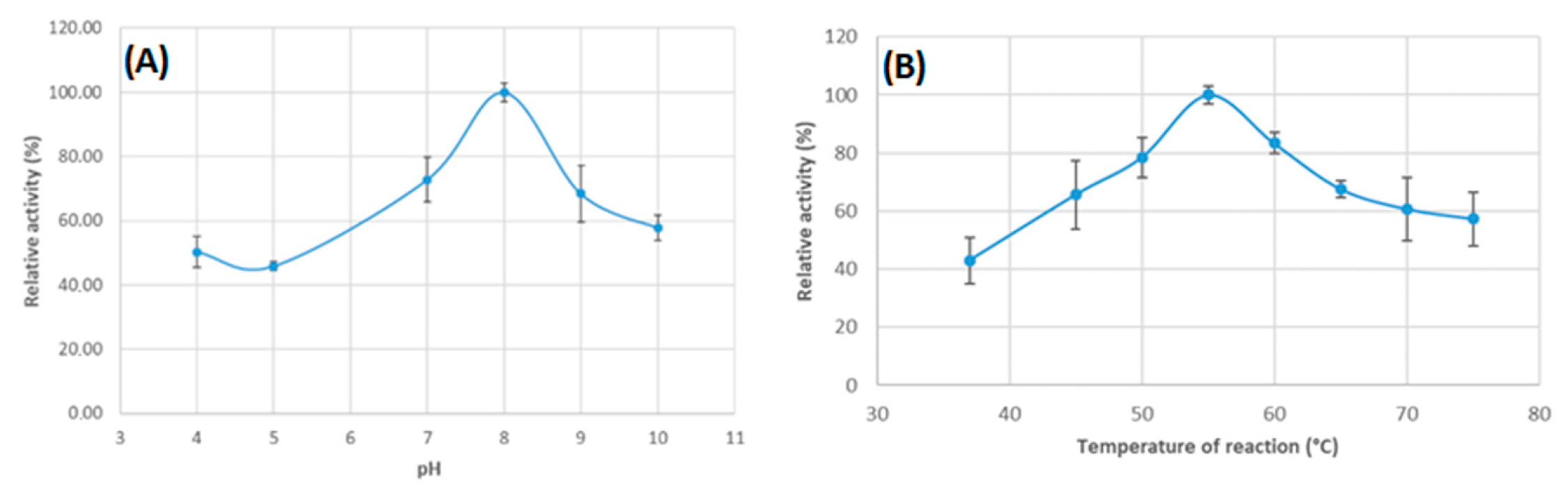

3.3. The Effect of the pH and Temperature on the Protein Activity

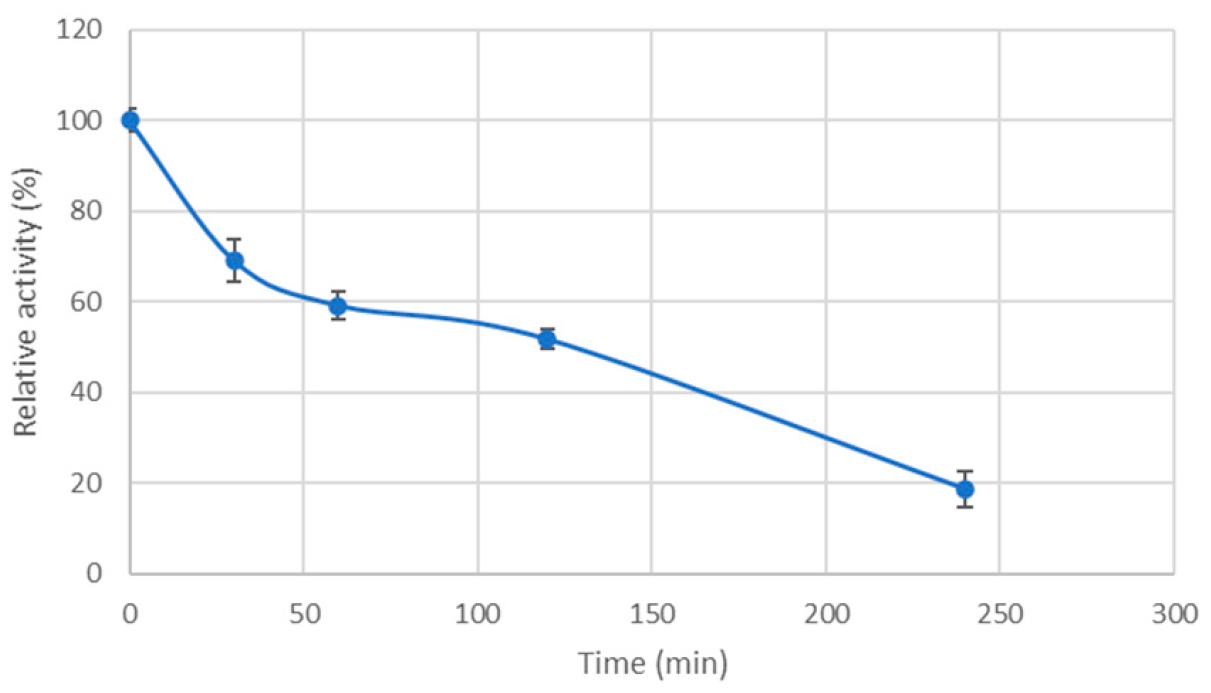

3.4. Temperature Stability of the Cel7465 Enzyme

3.5. The Effect of Different Ions on the Reaction Was Also Investigated

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lynd, L.R.; Weimer, P.J.; Van Zyl, W.H.; Pretorius, I.S. Microbial Cellulose Utilization: Fundamentals and Biotechnology. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2002, 66, 506–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beguin, P.; Aubert, J.-P. The Biological Degradation of Cellulose. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 1994, 13, 25–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Streit, W.R.; Schmitz, R.A. Metagenomics—The Key to the Uncultured Microbes. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2004, 7, 492–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hess, M.; Sczyrba, A.; Egan, R.; Kim, T.-W.; Chokhawala, H.; Schroth, G.; Luo, S.; Clark, D.S.; Chen, F.; Zhang, T.; et al. Metagenomic Discovery of Biomass-Degrading Genes and Genomes from Cow Rumen. Science 2011, 331, 463–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandrasekharaiah, M.; Thulasi, A.; Bagath, M.; Kumar, D.P.; Santosh, S.S.; Palanivel, C.; Jose, V.L.; Sampath, K.T. Identification of Cellulase Gene from the Metagenome of Equus burchelli Fecal Samples and Functional Characterization of a Novel Bifunctional Cellulolytic enzyme. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2012, 167, 132–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, A.; Zou, G.; Yan, X.; Wang, Q.; Zhang, J.; Liu, F.; Zhu, B.; Zhou, Z. Expression and Characterization of a Novel Metagenome-Derived Cellulase Exo2b and Its Application to Improve Cellulase Activity in Trichoderma reesei. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2012, 96, 951–962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Z.; Ruan, L.; Chen, X.; Zhang, Y.; Xu, X. A Novel Salt-Tolerant Endo-β-1,4-Glucanase Cel5A in Vibrio sp. G21 Isolated from Mangrove Soil. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2010, 87, 1373–1382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Voget, S.; Steele, H.L.; Streit, W.R. Characterization of a Metagenome-Derived Halotolerant cellulase. J. Biotechnol. 2006, 126, 26–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ali, S.M.; Soliman, N.A.; Allah Abdal-Aziz, S.A.; Abdel-Fattah, Y.R. Cloning of Cellulase Gene Using Metagenomic Approach of Soils Collected from Wadi El Natrun, an Extremophilic Desert Valley in Egypt. J. Genet. Eng. Biotechnol. 2022, 20, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nyathi, M.; Dhlamini, Z.; Ncube, T. Cloning Cellulase Genes from Victoria Falls Rainforest Decaying Logs Metagenome. Pol. J. Microbiol. 2024, 73, 343–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeh, Y.-F.; Chang, S.C.; Kuo, H.-W.; Tong, C.-G.; Yu, S.-M.; Ho, T.-H.D. A Metagenomic Approach for the Identification and Cloning of an Endoglucanase from Rice Straw Compost. Gene 2013, 519, 360–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leis, B.; Heinze, S.; Angelov, A.; Pham, V.; Thürmer, A.; Jebbar, M.; Golyshin, P.; Streit, W.; Daniel, R.; Liebl, W. Functional Screening of Hydrolytic Activities Reveals an Extremely Thermostable cellulase from a Deep-Sea Archaeon. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2015, 3, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paloyan, A.; Soghomonyan, T.; Karapetyan, M.; Grigoryan, H.; Krüger, A.; Cuskin, F.; Marles-Wright, J.; Burkhardt, C.; Antranikian, G. A Novel Acidic laminarinase Derived from Jermuk Hot Spring Metagenome. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2025, 109, 172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez del Río, Á.; Giner lamia, J.; Cantalapiedra, C.; Botas, J.; Deng, Z.; Hernández-Plaza, A.; Munar-Palmer, M.; Santamaría-Hernando, S.; Rodriguez-Herva, J.; Ruscheweyh, H.-J.; et al. Functional and Evolutionary Significance of Unknown Genes from Uncultivated Taxa. Nature 2023, 626, 377–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanjaya, R.; Putri, K.; Kurniati, A.; Rohman, A.; Puspaningsih, N.N. In Silico Characterization of the GH5-Cellulase Family from Uncultured Microorganisms: Physicochemical and Structural Studies. J. Genet. Eng. Biotechnol. 2021, 19, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, R.G.; Walker, D.C.; Mclnnes, R.R. E. coli Host Strains Significantly Affect the Quality of Small Scale Plasmid DNA Preparations Used for Sequencing. Nucleic Acids Res. 1993, 21, 1677–1678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yanisch-Perron, C.; Vieira, J.; Messing, J. Improved M13 Phage Cloning Vectors and Host Strains: Nucleotide Sequences of the M13mpl8 and pUC19 Vectors. Gene 1985, 33, 103–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, W.; Lomsadze, A.; Borodovsky, M. Ab Initio Gene Identification in Metagenomic Sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010, 38, e132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eddy, S.R. A New Generation of Homology Search Tools Based on Probabilistic Inference. Genome Inform. 2009, 23, 205–211. [Google Scholar]

- Uritskiy, G.V.; DiRuggiero, J.; Taylor, J. MetaWRAP—A Flexible Pipeline for Genome-Resolved Metagenomic Data Analysis. Microbiome 2018, 6, 158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chklovski, A.; Parks, D.H.; Woodcroft, B.J.; Tyson, G.W. CheckM2: A Rapid, Scalable and Accurate Tool for Assessing Microbial Genome Quality Using Machine Learning. Nat. Methods 2023, 20, 1203–1212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aroney, S.T.N.; Newell, R.J.P.; Nissen, J.N.; Camargo, A.P.; Tyson, G.W.; Woodcroft, B.J. CoverM: Read Alignment Statistics for Metagenomics. Bioinformatics 2025, 41, btaf147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parks, D.H.; Chuvochina, M.; Rinke, C.; Mussig, A.J.; Chaumeil, P.-A.; Hugenholtz, P. GTDB: An Ongoing Census of Bacterial and Archaeal Diversity through a Phylogenetically Consistent, Rank Normalized and Complete Genome-Based Taxonomy. Nucleic Acids Res. 2022, 50, D785–D794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tatusova, T.; DiCuccio, M.; Badretdin, A.; Chetvernin, V.; Nawrocki, E.P.; Zaslavsky, L.; Lomsadze, A.; Pruitt, K.D.; Borodovsky, M.; Ostell, J. NCBI Prokaryotic Genome Annotation Pipeline. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016, 44, 6614–6624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, J.; Ge, Q.; Yan, Y.; Zhang, X.; Huang, L.; Yin, Y. dbCAN3: Automated Carbohydrate-Active Enzyme and Substrate Annotation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2023, 51, W115–W121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drula, E.; Garron, M.-L.; Dogan, S.; Lombard, V.; Henrissat, B.; Terrapon, N. The Carbohydrate-Active Enzyme Database: Functions and Literature. Nucleic Acids Res. 2022, 50, D571–D577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katoh, K.; Standley, D.M. MAFFT Multiple Sequence Alignment Software Version 7: Improvements in Performance and Usability. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2013, 30, 772–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capella-Gutiérrez, S.; Silla-Martínez, J.M.; Gabaldón, T. trimAl: A Tool for Automated Alignment Trimming in Large-Scale Phylogenetic Analyses. Bioinformatics 2009, 25, 1972–1973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, T.; Ly-Trong, N.; Ren, H.; Baños, H.; Roger, A.; Susko, E.; Bielow, C.; De Maio, N.; Goldman, N.; Hahn, M.; et al. IQ-TREE 3: Phylogenomic Inference Software Using Complex Evolutionary Models. Preprint 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schober, I.; Koblitz, J.; Sardà Carbasse, J.; Ebeling, C.; Schmidt, M.L.; Podstawka, A.; Gupta, R.; Ilangovan, V.; Chamanara, J.; Overmann, J.; et al. Bac Dive in 2025: The Core Database for Prokaryotic Strain Data. Nucleic Acids Res. 2025, 53, D748–D756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Letunic, I.; Bork, P. Interactive Tree Of Life (iTOL) v5: An Online Tool for Phylogenetic Tree Display and Annotation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021, 49, W293–W296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sambrook, J.; Russell, D. Molecular Cloning: A Laboratory Manual (3-Volume Set); Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press: Cold Spring Harbor, NY, USA, 2001; Volume 1, ISBN 978-0-87969-577-4. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, G.L. Use of Dinitrosalicylic Acid Reagent for Determination of Reducing Sugar. Anal. Chem. 1959, 31, 426–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toshchakov, S.V.; Izotova, A.O.; Vinogradova, E.N.; Kachmazov, G.S.; Tuaeva, A.Y.; Abaev, V.T.; Evteeva, M.A.; Gunitseva, N.M.; Korzhenkov, A.A.; Elcheninov, A.G.; et al. Culture-Independent Survey of Thermophilic Microbial Communities of the North Caucasus. Biology 2021, 10, 1352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhat, S.P.; Roach, D.J. Bioactivity of Microbial Biofilms in Extreme Environments. Front. Microbiol. 2025, 16, 1602583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarzycki, J.; Brecht, V.; Müller, M.; Fuchs, G. Identifying the Missing Steps of the Autotrophic 3-Hydroxypropionate CO2 Fixation Cycle in Chloroflexus aurantiacus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2009, 106, 21317–21322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreira, C.; Rainey, F.A.; Nobre, M.F.; Da Silva, M.T.; Da Costa, M.S. Tepidimonas Ignava Gen. Nov., Sp. Nov., a New Chemolithoheterotrophic and Slightly Thermophilic Member of the Beta-Proteobacteria. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2000, 50, 735–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tindall, B.J.; Sikorski, J.; Lucas, S.; Goltsman, E.; Copeland, A.; Glavina Del Rio, T.; Nolan, M.; Tice, H.; Cheng, J.-F.; Han, C.; et al. Complete Genome Sequence of Meiothermus ruber Type Strain (21T). Stand. Genom. Sci. 2010, 3, 26–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamaki, H.; Tanaka, Y.; Matsuzawa, H.; Muramatsu, M.; Meng, X.-Y.; Hanada, S.; Mori, K.; Kamagata, Y. Armatimonas rosea Gen. Nov., Sp. Nov., of a Novel Bacterial Phylum, Armatimonadetes Phyl. Nov., Formally Called the Candidate Phylum OP10. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2011, 61, 1442–1447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.C.-Y.; Morgan, X.C.; Dunfield, P.F.; Tamas, I.; McDonald, I.R.; Stott, M.B. Genomic Analysis of Chthonomonas calidirosea, the First Sequenced Isolate of the Phylum Armatimonadetes. ISME J. 2014, 8, 1522–1533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Im, W.-T.; Hu, Z.-Y.; Kim, K.-H.; Rhee, S.-K.; Meng, H.; Lee, S.-T.; Quan, Z.-X. Description of Fimbriimonas ginsengisoli Gen. Nov., Sp. Nov. within the Fimbriimonadia Class Nov., of the Phylum Armatimonadetes. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek 2012, 102, 307–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaumeil, P.-A.; Mussig, A.J.; Hugenholtz, P.; Parks, D.H. GTDB-Tk v2: Memory Friendly Classification with the Genome Taxonomy Database. Bioinformatics 2022, 38, 5315–5316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Slobodkina, G.B.; Merkel, A.Y.; Kondrasheva, K.V.; Stroeva, A.R.; Bonch-Osmolovskaya, E.A.; Davranov, K.D.; Slobodkin, A.I. Taxonomic and Metabolic Diversity of Microbial Communities in a Thermal Water Stream in Uzbekistan and Proposal of Two New Classes of Uncultivated Bacteria, Desulfocorpusculia Class. Nov. and Tepidihabitantia Class. Nov., Named Following the Rules of SeqCode. Syst. Appl. Microbiol. 2025, 48, 126650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, D.-C.; Wang, F.-Q.; Amann, R.I.; Teeling, H.; Du, Z.-J. Epiphytic Common Core Bacteria in the Microbiomes of Co-Located Green (Ulva), Brown (Saccharina) and Red (Grateloupia, Gelidium) Macroalgae. Microbiome 2023, 11, 126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kato, S.; Masuda, S.; Shibata, A.; Shirasu, K.; Ohkuma, M. Insights into Ecological Roles of Uncultivated Bacteria in Katase Hot Spring Sediment from Long-Read Metagenomics. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 1045931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhat, M.K. Cellulases and Related Enzymes in Biotechnology. Biotechnol. Adv. 2000, 18, 355–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, R.; Tabatabaei, M.; Karimi, K.; Sárvári Horváth, I. Recent Updates on Lignocellulosic Biomass Derived Ethanol—A Review. Biofuel Res. J. 2016, 3, 347–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araújo, R.; Casal, M.; Cavaco-Paulo, A. Application of Enzymes for Textile Fibres Processing. Biocatal. Biotransformation 2008, 26, 332–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toprak, T.; Anis, P. Combined One-Bath Desizing–Scouring–Depilling Enzymatic Process and Effect of Some Process Parameters. Cellulose 2017, 24, 383–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutaoney, P.; Rai, S.N.; Sinha, S.; Choudhary, R.; Gupta, A.K.; Singh, S.K.; Banerjee, P. Current Perspective in Research and Industrial Applications of Microbial Cellulases. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 264, 130639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Carvalho, L.M.J.; De Castro, I.M.; Da Silva, C.A.B. A Study of Retention of Sugars in the Process of Clarification of Pineapple Juice (Ananas comosus, L. Merril) by Micro- and Ultra-Filtration. J. Food Eng. 2008, 87, 447–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, A.S.; Jepsen, S.M.; Sørensen, N.S. Enzymatic Release of Antioxidants for Human Low-Density Lipoprotein from Grape Pomace. J. Agric. Food Chem. 1998, 46, 2439–2446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bamforth, C.W. Current Perspectives on the Role of Enzymes in Brewing. J. Cereal Sci. 2009, 50, 353–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.S.; Fernando, S.; Ross, B.; Wu, J.; Qin, W. Endoglucanase (EG) Activity Assays. In Cellulases; Lübeck, M., Ed.; Methods in Molecular Biology; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2018; Volume 1796, pp. 169–183. ISBN 978-1-4939-7876-2. [Google Scholar]

- Liew, K.J.; Liang, C.H.; Lau, Y.T.; Yaakop, A.S.; Chan, K.-G.; Shahar, S.; Shamsir, M.S.; Goh, K.M. Thermophiles and Carbohydrate-Active Enzymes (CAZymes) in Biofilm Microbial Consortia That Decompose Lignocellulosic Plant Litters at High Temperatures. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 2850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, T.J.; Buongiorno, J.; Jessen, G.L.; Schrenk, M.O.; Fordyce, J.A.; De Moor, J.M.; Ramírez, C.J.; Barry, P.H.; Yücel, M.; Selci, M.; et al. Chemolithoautotroph Distributions across the Subsurface of a Convergent Margin. ISME J. 2023, 17, 140–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aspeborg, H.; Coutinho, P.M.; Wang, Y.; Brumer, H.; Henrissat, B. Evolution, Substrate Specificity and Subfamily Classification of Glycoside Hydrolase Family 5 (GH5). BMC Evol. Biol. 2012, 12, 186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, F.; Vermaas, J.V.; Zheng, J.; Wang, Y.; Tu, T.; Wang, X.; Xie, X.; Yao, B.; Beckham, G.T.; Luo, H. Activity and Thermostability of GH5 Endoglucanase Chimeras from Mesophilic and Thermophilic Parents. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2019, 85, e02079-18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fusco, F.A.; Ronca, R.; Fiorentino, G.; Pedone, E.; Contursi, P.; Bartolucci, S.; Limauro, D. Biochemical Characterization of a Thermostable Endomannanase/Endoglucanase from Dictyoglomus turgidum. Extremophiles 2018, 22, 131–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, Y.; Dodd, D.; Hespen, C.W.; Ohene-Adjei, S.; Schroeder, C.M.; Mackie, R.I.; Cann, I.K.O. Comparative Analyses of Two Thermophilic Enzymes Exhibiting Both β-1,4 Mannosidic and β-1,4 Glucosidic Cleavage Activities from Caldanaerobius polysaccharolyticus. J. Bacteriol. 2010, 192, 4111–4121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oyama, T.; Schmitz, G.E.; Dodd, D.; Han, Y.; Burnett, A.; Nagasawa, N.; Mackie, R.I.; Nakamura, H.; Morikawa, K.; Cann, I. Mutational and Structural Analyses of Caldanaerobius polysaccharolyticus Man5B Reveal Novel Active Site Residues for Family 5 Glycoside Hydrolases. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e80448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escuder-Rodríguez, J.-J.; González-Suarez, M.; de Castro, M.-E.; Saavedra-Bouza, A.; Becerra, M.; González-Siso, M.-I. Characterization of a Novel Thermophilic Metagenomic GH5 Endoglucanase Heterologously Expressed in Escherichia coli and Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Biotechnol. Biofuels Bioprod. 2022, 15, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, L.; Duan, S.; Feng, X.; Zheng, K.; Yang, Q.; Liu, Z. Purification and Characterization of a Thermostable β -Mannanase from Bacillus Subtilis BE-91: Potential Application in Inflammatory Diseases. BioMed Res. Int. 2016, 2016, 6380147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, H.; Li, S.; Zheng, H.; Wei, Z.; Liu, D.; Raza, W.; Shen, Q.; Xu, Y. A New Acidophilic Thermostable Endo-1,4-β-Mannanase from Penicillium oxalicum GZ-2: Cloning, Characterization and Functional Expression in Pichia Pastoris. BMC Biotechnol. 2014, 14, 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, S.; Lee, M.-H.; Lee, E.-S.; Nam, Y.-D.; Seo, D.-H. Characterization of Mannanase from Bacillus sp., a Novel Codium fragile Cell Wall-Degrading Bacterium. Food Sci. Biotechnol. 2018, 27, 115–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Qian, J.; Shi, T.; Wang, Y.; Ding, Q.; Ye, C. Application of Extremophile Cell Factories in Industrial Biotechnology. Enzym. Microb. Technol. 2024, 175, 110407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rigoldi, F.; Donini, S.; Redaelli, A.; Parisini, E.; Gautieri, A. Review: Engineering of Thermostable Enzymes for Industrial Applications. APL Bioeng. 2018, 2, 011501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mesbah, N.M. Industrial Biotechnology Based on Enzymes From Extreme Environments. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2022, 10, 870083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadnikov, V.V.; Mardanov, A.V.; Beletsky, A.V.; Karnachuk, O.V.; Ravin, N.V. Microbial Life in the Deep Subsurface Aquifer Illuminated by Metagenomics. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 572252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Strain | Genotype | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| E. coli DH5a | F− 80ΔlacZ M15 (lacZYA-argF) U169 recA1 endA1hsdR17(rk-, mk+) phoA supE44 -thi-1 gyrA96 relA1 | [16], Lab stock |

| E. coli TOP10 | F− mcrA (mrr-hsdRMS-mcrBC) 80lacZ M15 lacX74 recA1 ara 139 (ara-leu)7697 galU galK rpsL (StrR) endA1 nupG. | Thermo Fischer Scientific, Waltham, CA, USA |

| E. coli BL21(DE3) pLys | F− ompT hsdSB(rB− mB−) gal dcm (DE3) pLysS (CamR) | Novagen |

| E. coli ArcticExpress (DE3) | E. coli B (DE3) F ompT hsdS(rB mB) dcm+ TetRgal endA Hte [cpn10 cpn60 GentR] | Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA. |

| Plasmid | Features | Reference |

| pUC19 | pMB1 replicon rep AmpR | [17], Lab stock |

| pET28a | pBR322 origin, f1 origin, T7 promoter, KMR | Novagen, Burlington, MA, USA |

| pUC19-cel7465 | Gene of the cellulase (cel7465) cloned in HincII restriction site | This work |

| pET28a-cel7465 | Gene of the cellulase (cel7465) cloned in restriction site Bsp19I and Sfr274I | This work |

| Purification Step | Specific Activity (U/mg; µmol/min×mg) | Purification Fold |

|---|---|---|

| Cell lysate | 761 ± 29 | - |

| Cell free extract | 784 ± 36 | 1.03 |

| Immobilized metal affinity chromatography (Ni-NTA) | 2640 ± 139 | 3.37 |

| Size exclusion chromatography | 4347 ± 380 | 5.7 |

| Residual Activity of Cellulase (%) | |

|---|---|

| Control (untreated enzyme) | 100 ± 13.8 |

| K+ | 4.9 ± 2.7 |

| Na+ | 45.2 ± 13.3 |

| Mg2+ | 147.4 ± 12.1 |

| Ca2+ | 131.7 ± 11.5 |

| Mn2+ | 786.9 ± 7.9 |

| EDTA 1 mM | 45.6 ± 5.6 |

| EDTA 10 mM | 22.3 ± 7.5 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Trachtmann, N.V.; Toshchakov, S.V.; Izotova, A.O.; Korzhenkov, A.A.; Evteeva, M.A.; Kachmazov, G.S.; Agboigba, E.E.; Validov, S.Z. Cloning and Characterization of the Novel Endoglucanase Identified in Deep Subsurface Thermal Well of Biragzang (North Ossetia) by Metagenomic Analysis. Biomolecules 2025, 15, 1710. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom15121710

Trachtmann NV, Toshchakov SV, Izotova AO, Korzhenkov AA, Evteeva MA, Kachmazov GS, Agboigba EE, Validov SZ. Cloning and Characterization of the Novel Endoglucanase Identified in Deep Subsurface Thermal Well of Biragzang (North Ossetia) by Metagenomic Analysis. Biomolecules. 2025; 15(12):1710. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom15121710

Chicago/Turabian StyleTrachtmann, Natalia V., Stepan V. Toshchakov, Anna O. Izotova, Aleksei A. Korzhenkov, Martha A. Evteeva, Gennady S. Kachmazov, Esperant E. Agboigba, and Shamil Z. Validov. 2025. "Cloning and Characterization of the Novel Endoglucanase Identified in Deep Subsurface Thermal Well of Biragzang (North Ossetia) by Metagenomic Analysis" Biomolecules 15, no. 12: 1710. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom15121710

APA StyleTrachtmann, N. V., Toshchakov, S. V., Izotova, A. O., Korzhenkov, A. A., Evteeva, M. A., Kachmazov, G. S., Agboigba, E. E., & Validov, S. Z. (2025). Cloning and Characterization of the Novel Endoglucanase Identified in Deep Subsurface Thermal Well of Biragzang (North Ossetia) by Metagenomic Analysis. Biomolecules, 15(12), 1710. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom15121710