Integrative Regulatory Networks of MicroRNA-483: Unveiling Its Systematic Role in Human Diseases and Clinical Implications

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Upstream Regulators of miR-483

2.1. TF-miR-483 Regulation

2.2. CircRNA-miR-483 Regulation

2.3. LncRNA-miR-483 Regulation

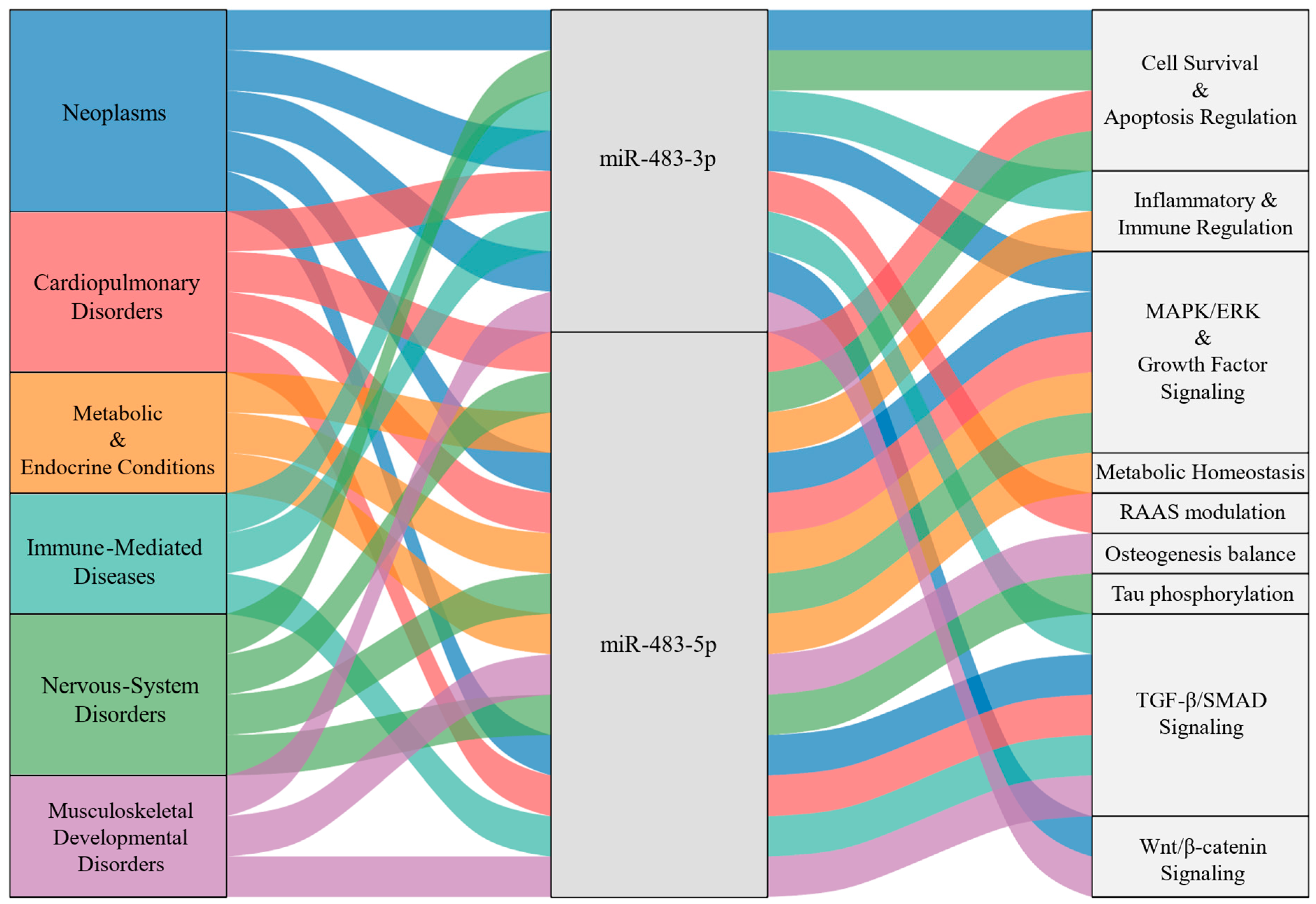

3. Integrative miR-483-Mediated Networks

3.1. Systematic Regulatory Network Mediated by miR-483

3.2. Disease-Specific Pathway Signatures of the miR-483 Network

3.2.1. Neoplasms

- (i)

- Cell-Cycle Acceleration and Apoptosis Evasion. Functionally, miR-483-3p disrupts the cellular division checkpoint and apoptotic brakes while reinforcing cyclin/CDK drive: it targets multiple cell-cycle regulators, including CCNE1, CDK4/6, CDC25A, and RB1, thereby accelerating G1/S transition [37,56,116,117,118]. Simultaneously, it suppresses the pro-apoptotic factor BBC3/PUMA and the p53 regulator MDM4, shifting the balance toward proliferation and apoptosis resistance [42,119,120]. Consistent with this target profile, overexpression of miR-483-3p inhibits TP53-mediated apoptosis in hepatocellular carcinoma [121]. This dual repression, of both division checkpoints and death signals, permits sustained tumor expansion.

- (ii)

- Developmental Plasticity and EMT via Wnt/β-Catenin and TGF-β/SMAD Pathways. miR-483-3p stabilizes Wnt signaling by targeting the pathway inhibitor DKK3, a mechanism implicated in colorectal and gastric cancer progression [64,122]. In parallel, it represses SMAD4 and SMAD2, central transducers of TGF-β signaling [123,124]. The functional outcome of SMAD suppression depends on tumor context: in early-stage cancers where TGF-β retains growth-inhibitory activity, miR-483 relieves this brake; in advanced tumors, reduced canonical SMAD signaling may favor non-canonical, pro-invasive TGF-β outputs that promote EMT.

- (iii)

- Growth-Factor Signaling and Invasion-Metastasis Circuits. Both miR-483 isoforms enhance mitogenic signaling by targeting negative regulators such as PTEN and by directly modulating effectors like IGF1 and MAPK1/ERK2, thereby reinforcing PI3K-Akt and MAPK cascades [29,73,125,126,127]. Downstream effects include increased eIF4E-mediated protein synthesis, which supports rapid cell growth [127]. Invasion is further promoted through extracellular matrix remodeling: miR-483-3p targets MMP9 and the integrin ITGB3, facilitating basement membrane degradation and cell motility [49,63,128]. Additional effects on genome maintenance and chromatin programs (e.g., BRCA1, histone deacetylases) may confer resistance to genotoxic stress [16].

3.2.2. Cardiopulmonary Disorders

- (i)

- RAAS Modulation and Vascular Homeostasis. The RAAS pathway, which controls blood pressure and fluid balance, is uniquely targeted by miR-483 in cardiovascular contexts [137]. miR-483-3p directly represses AGT (angiotensinogen), ACE and ACE2 (angiotensin-converting enzymes), and AGTR2 (angiotensin II receptor type 2), thereby attenuating hypertensive signaling and pathological cardiac remodeling [138]. miR-483-5p complements this activity by targeting MAPK1/3 (ERK2/ERK1) and the vasoconstrictor endothelin-1 (ET-1), which interface with RAAS to regulate smooth muscle contractility and endothelial function [139,140]. Together, both isoforms coordinate to dampen pressor signaling and preserve vascular stability.

- (ii)

- Antifibrotic Control via TGF-β/SMAD-ROCK Signaling. Cardiac fibrosis results from sustained TGF-β signaling and cytoskeletal remodeling in myofibroblasts. miR-483-5p suppresses this cascade at multiple nodes: it targets the ligand TGFB1, the receptor TGFBR2, and the downstream effector SMAD2, thereby reducing profibrotic gene transcription [140,141]. Concurrently, miR-483-5p inhibits ROCK1, a kinase that drives actomyosin contractility and myofibroblast differentiation, which limits extracellular matrix deposition and tissue stiffening [140]. Consistent with this mechanism, miR-483-5p also downregulates TIMP2 and PDGFB, matrix regulators implicated in cardiac remodeling [140,142]. This multilayered repression establishes miR-483-5p as a central antifibrotic regulator in the heart.

- (iii)

- Stress-Apoptosis Control and Angiogenic Balance. miR-483-5p enhances cardiomyocyte survival under stress by targeting MAPK3/ERK1, which modulates cytoprotective signaling, and by suppressing the pro-apoptotic factor TNFSF8 [143]. In the vasculature, miR-483-3p regulates the endothelial transcription factor VEZF1, promoting orderly angiogenesis and barrier integrity [144]. These effects sustain both myocardial viability and microvascular function during ischemic injury.

3.2.3. Metabolic & Endocrine Conditions

- (i)

- β-Cell Identity and Insulin/IGF Signaling. miR-483-5p targets PDX1 and MAFA, transcription factors required for β-cell maturation and insulin gene expression [145]. Additionally, miR-483-3p represses IGF1 and IGF1R, while miR-483-5p targets the downstream kinase MAPK1/ERK2, collectively modulating β-cell survival and glucose-stimulated insulin secretion in experimental diabetes [36,146,147].

- (ii)

- Inflammatory JAK/STAT Signaling and Diabetic Complications. By tuning cytokine signaling nodes such as SOCS3 and IL6, miR-483-5p links metabolic inflammation to endocrine dysfunction [148,149]. This axis extends to tissue injury, in diabetic kidney disease, miR-483-5p suppresses TIMP2 and HDAC4, attenuating TGF-β-driven renal fibrosis [36,146,147]. Repression of IGF1R further connects metabolic inflammation to diabetic retinopathy, suggesting that miR-483 coordinates immune-metabolic crosstalk across multiple target organs.

- (iii)

- Adipogenesis and Lipid Metabolism. miR-483-5p influences adipocyte differentiation by targeting ALDH1A3 and regulates cholesterol metabolism through PCSK9 [150,151,152]. These targets converge on pathways controlled by PPAR transcription factors [153], providing a mechanistic basis for miR-483 effects on adipose expansion, circulating lipid profiles, and hepatic lipid deposition, contributing to obesity, NAFLD, and cardiometabolic risk.

3.2.4. Immune-Mediated Diseases

- (i)

- Modulation of the Pro-Fibrotic Cascade. In acute or immune-related fibrosis with transient inflammation such as pancreatitis-associated lung injury, rheumatoid arthritis, and sepsis-induced intestinal injury, miR-483 acts as a suppressor of pathological fibrosis and inflammation [154,155,156]. Both miR-483 isoforms interfere with TGF-β–driven signaling cascades: miR-483-3p represses upstream amplifiers of fibrotic signaling such as CTGF and the nuclear kinase HIPK2, while miR-483-5p sustains TGF-β-driven transcription by suppressing the splicing regulator SRSF4 and epigenetic cofactor HDAC2, thereby blocking myofibroblast differentiation and reducing the expression of structural proteins such as COL1A1 [34,154,155,156,157]. These effects collectively limit ECM accumulation and tissue stiffening, aligning miR-483 with an anti-fibrotic and anti-inflammatory role in acute or immune-driven injury.By contrast, in chronic fibrotic disorders such as systemic sclerosis (SSc), miR-483-5p appears to engage a different regulatory axis [158]. Overexpression of miR-483-5p in endothelial cells enhances transcription of myofibroblast differentiation markers αSMA and SM22A, while suppresses FLI1, a negative regulator of ECM that is downregulated in SSc skin, indicating a selective remodeling rather than a global repression of ECM synthesis [158]. Together, these data position miR-483-5p as a context-dependent regulator of fibrogenesis, displaying protective effects in acute immune-inflammatory injury but pro-fibrotic remodeling in chronic sclerotic conditions.

- (ii)

- Cytokine Signaling and Leukocyte Dynamics. miR-483 also modulates the inflammatory processes that initiate and sustain fibrosis [46]. miR-483-3p targets CD81 (involved in immune cell adhesion and signaling), RNF5 (a regulator of inflammatory signaling), and APLNR (which controls leukocyte extravasation from blood into tissue) [46,159]. Additionally, repression of IGF1 influences fibroblast-macrophage crosstalk, a critical determinant of tissue repair and inflammation [160]. Through these targets, miR-483-3p attenuates both the intensity of cytokine signaling and the extent of leukocyte infiltration, thereby aligning the inflammatory state with the tissue remodeling processes.

3.2.5. Nervous-System Disorders

- (i)

- Regulating Tau Phosphorylation and Synaptic Plasticity via MAPK/ERK Signaling. In Alzheimer’s disease models, miR-483-5p targets ERK1 and ERK2, kinases that drive pathological Tau hyperphosphorylation [161]. Notably, this repression occurs within a range that limits toxic Tau phosphorylation without abolishing ERK-dependent synaptic plasticity, a balance critical for preserving long-term potentiation and cognitive function. Thus, miR-483-5p may uncouple neurodegenerative ERK signaling from physiological synaptic maintenance.

- (ii)

- Stress-Apoptosis Buffering and Neuronal Survival. miR-483 confers acute stress resistance through coordinated regulation of oxidative defense and apoptotic checkpoints [162,163]. miR-483-5p limits oxidative damage by targeting GPX3 and modulates excitotoxicity via MAPK/ERK fine-tuning, while miR-483-3p suppresses XPO1 to retain pro-survival transcription factors in the nucleus [162,163]. Over longer timescales, both isoforms sustain synaptic architecture: miR-483-3p and -5p regulate XPO1 and PGAP2, genes required for neurotrophic signaling and synaptosomal protein trafficking [163]. This two-tiered mechanism: immediate cytoprotection plus sustained structural support, distinguishes miR-483 from stress-response miRNAs with purely acute effects.

3.2.6. Musculoskeletal & Developmental Disorders

- (i)

- Regulation of Skeletal Patterning and Lineage Commitment. The two miR-483 isoforms have opposite roles in bone formation. miR-483-5p inhibits osteogenesis by repressing SATB2, a chromatin regulator that activates the RUNX2/osteocalcin transcriptional program required for osteoblast differentiation [164]. It also suppresses osteogenic differentiation of bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells (BMSCs) by targeting RPL31, which modulates RAS/MEK/ERK signaling [38].Conversely, miR-483-3p promotes bone formation by repressing DKK2, an inhibitor of Wnt signaling, thereby enhancing osteoblast proliferation and differentiation [165]. miR-483-3p also facilitates BMSC osteogenesis by targeting STAT1 [166].Beyond osteogenesis, miR-483 regulates chondrogenesis and skeletal morphogenesis. miR-483-3p inhibits chondrogenic differentiation by targeting SMAD4 [167], while miR-483-5p modulates cartilage homeostasis by repressing MATN3, a cartilage matrix protein [168], and repressed DUSP5, a MAPK phosphatase that provides spatial patterning signals during limb and joint formation [169].

- (ii)

- Myogenesis and Tissue Regeneration. In skeletal muscle, miR-483 attenuates anabolic IGF signaling by targeting IGF1, IGF2, and their downstream kinases MAPK1/ERK2 and MAPK3/ERK1, thereby reducing signals for myocyte survival, hypertrophy, and protein synthesis [32,169,170]. Both isoforms also repress the serum response factor (SRF), a transcription factor controlling actin cytoskeleton and contractile gene expression, and NOTCH3, which targeted by miR-483-5p, regulating satellite cell activation during muscle repair [148,171]. This regulatory network is further refined through the targeting of DUSP5 by miR-483-5p, which controls ERK signal duration and balances proliferation with terminal differentiation [68].

3.2.7. The Functional Landscape of miR-483 in Diverse Human Diseases

4. miR-483 as a Clinical Biomarker and Therapeutic Target

4.1. Diagnostic Applications

4.2. Prognostic Significance

4.3. Therapeutic Potential

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bartel, D.P. MicroRNAs: Genomics, biogenesis, mechanism, and function. Cell 2004, 116, 281–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balasubramanian, D.; Vanderpool, C.K. New developments in post-transcriptional regulation of operons by small RNAs. RNA Biol. 2013, 10, 337–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- O’Brien, J.; Hayder, H.; Zayed, Y.; Peng, C. Overview of MicroRNA Biogenesis, Mechanisms of Actions, and Circulation. Front. Endocrinol. 2018, 9, 402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, S.; Yu, S.; Huang, H.Y.; Lin, Y.C.; Huang, Y.; Zhang, B.; Xiao, J.; Zuo, H.; Wang, J.; Li, Z.; et al. miRTarBase 2025: Updates to the collection of experimentally validated microRNA-target interactions. Nucleic Acids Res. 2025, 53, D147–D156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skoufos, G.; Kakoulidis, P.; Tastsoglou, S.; Zacharopoulou, E.; Kotsira, V.; Miliotis, M.; Mavromati, G.; Grigoriadis, D.; Zioga, M.; Velli, A.; et al. TarBase-v9.0 extends experimentally supported miRNA-gene interactions to cell-types and virally encoded miRNAs. Nucleic Acids Res. 2024, 52, D304–D310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niu, Z.Y.; Li, W.L.; Jiang, D.L.; Li, Y.S.; Xie, X.J. Mir-483 inhibits colon cancer cell proliferation and migration by targeting TRAF1. Kaohsiung J. Med. Sci. 2018, 34, 479–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCann, M.J.; Rotjanapun, K.; Hesketh, J.E.; Roy, N.C. Expression profiling indicating low selenium-sensitive microRNA levels linked to cell cycle and cell stress response pathways in the CaCo-2 cell line. Br. J. Nutr. 2017, 117, 1212–1221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, W.; Yang, W.; Yang, J.; Zhu, H.; Duan, L.; Wang, X.; Li, Y.; Niu, L.; Xiao, S.; Zhang, R.; et al. miR-483 promotes the development of colorectal cancer by inhibiting the expression level of EI24. Mol. Med. Rep. 2021, 24, 567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, H.; Xu, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Yang, Y.; Mou, Y.; Gao, Y.; Chen, R.; Chen, C.; Dai, P. MiR-483-3p regulates oxaliplatin resistance by targeting FAM171B in human colorectal cancer cells. Artif. Cells Nanomed. Biotechnol. 2019, 47, 725–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, H.; Liu, Y.; Jiang, J.; Liu, Y.; Yang, Z.; Wu, S.; Cao, W.; Cui, I.H.; Yu, C. IGF2-derived miR-483 mediated oncofunction by suppressing DLC-1 and associated with colorectal cancer. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 48456–48466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, L.; Wan, A.; Zhou, Z.; Chen, D.; Liang, H.; Liu, C.; Yan, S.; Niu, Y.; Lin, Z.; Zhan, S.; et al. RNA-binding protein RALY reprogrammes mitochondrial metabolism via mediating miRNA processing in colorectal cancer. Gut 2021, 70, 1698–1712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Candiello, E.; Reato, G.; Verginelli, F.; Gambardella, G.; D’Ambrosio, A.; Calandra, N.; Orzan, F.; Iuliano, A.; Albano, R.; Sassi, F.; et al. MicroRNA 483-3p overexpression unleashes invasive growth of metastatic colorectal cancer via NDRG1 downregulation and ensuing activation of the ERBB3/AKT axis. Mol. Oncol. 2023, 17, 1280–1301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, Q.; Xu, Y.; Yang, C.; Chen, Z.; Jia, C.; Chen, J.; Zhang, Y.; Lai, P.; Fan, X.; Zhou, X.; et al. miR-483-5p promotes invasion and metastasis of lung adenocarcinoma by targeting RhoGDI1 and ALCAM. Cancer Res. 2014, 74, 3031–3042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, W.; Zhao, L.J.; Yang, Y.; Wang, R.Y.; Ren, H.; Zhao, P.; Zhou, W.P.; Qi, Z.T. Retinoic acid induced 16 enhances tumorigenesis and serves as a novel tumor marker for hepatocellular carcinoma. Carcinogenesis 2012, 33, 2578–2585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, X.; Lyu, J. Tumor suppressor function of miR-483-3p on breast cancer via targeting of the cyclin E1 gene. Exp. Ther. Med. 2018, 16, 2615–2620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; French, B.A.; Li, J.; Tillman, B.; French, S.W. Altered regulation of miR-34a and miR-483-3p in alcoholic hepatitis and DDC fed mice. Exp. Mol. Pathol. 2015, 99, 552–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, D.; Zhou, L.; Hu, R. Exosomes derived from BMSCs alleviates high glucose-induced diabetic retinopathy via carrying miR-483-5p. J. Biochem. Mol. Toxicol. 2024, 38, e23616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayor-Lynn, K.; Toloubeydokhti, T.; Cruz, A.C.; Chegini, N. Expression profile of microRNAs and mRNAs in human placentas from pregnancies complicated by preeclampsia and preterm labor. Reprod. Sci. 2011, 18, 46–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, Y.; Song, Y.; Li, Y.; Zhao, D.; Ma, L.; Tan, L. miR-483 is Down-Regulated in Polycystic Ovarian Syndrome and Inhibits KGN Cell Proliferation via Targeting Insulin-Like Growth Factor 1 (IGF1). Med. Sci. Monit. 2016, 22, 3383–3393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez Esmerats, J.; Villa-Roel, N.; Kumar, S.; Gu, L.; Salim, M.T.; Ohh, M.; Taylor, W.R.; Nerem, R.M.; Yoganathan, A.P.; Jo, H. Disturbed Flow Increases UBE2C (Ubiquitin E2 Ligase C) via Loss of miR-483-3p, Inducing Aortic Valve Calcification by the pVHL (von Hippel-Lindau Protein) and HIF-1alpha (Hypoxia-Inducible Factor-1alpha) Pathway in Endothelial Cells. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2019, 39, 467–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, L.; Hu, N.; Du, X.; Wang, W.; Chen, H.; Li, W.; Wei, S.; Zhuang, H.; Li, X.; Li, C. Upregulation of miR-483-3p contributes to endothelial progenitor cells dysfunction in deep vein thrombosis patients via SRF. J. Transl. Med. 2016, 14, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Liu, Y.; Ma, N.; Wang, C.; Zou, J.; Liu, Z.; Zhou, Z.; Han, D.; He, J.; et al. miR-483-3p regulates hyperglycaemia-induced cardiomyocyte apoptosis in transgenic mice. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2016, 477, 541–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, Y.; Ma, N.; Wang, X.; Hui, Y.; Li, F.; Xiang, Y.; Zhou, J.; Zou, C.; Jin, J.; Lv, G.; et al. MiR-483-5p controls angiogenesis in vitro and targets serum response factor. FEBS Lett. 2011, 585, 3095–3100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saddic, L.A.; Chang, T.W.; Sigurdsson, M.I.; Heydarpour, M.; Raby, B.A.; Shernan, S.K.; Aranki, S.F.; Body, S.C.; Muehlschlegel, J.D. Integrated microRNA and mRNA responses to acute human left ventricular ischemia. Physiol. Genom. 2015, 47, 455–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, H.; Cai, J.; Xu, L.; Liu, J.; Chen, M.; Zheng, M.; Wang, L.; Yang, X. miR-483-3p regulates acute myocardial infarction by transcriptionally repressing insulin growth factor 1 expression. Mol. Med. Rep. 2018, 17, 4785–4790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, H.; Wang, J.; Du, A.; Li, Y. MiR-483-3p inhibition ameliorates myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury by targeting the MDM4/p53 pathway. Mol. Immunol. 2020, 125, 9–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leng, C.; Sun, J.; Xin, K.; Ge, J.; Liu, P.; Feng, X. High expression of miR-483-5p aggravates sepsis-induced acute lung injury. J. Toxicol. Sci. 2020, 45, 77–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, M.; Dong, J.; Wen, J.; Zhang, Y.; Han, S.Y.; Wang, C.; Gongol, B.; Wei, T.W.; Kang, J.; Huang, H.Y.; et al. Epitranscriptomic Modification of MicroRNA Increases Atherosclerosis Susceptibility. Circulation 2023, 148, 1819–1822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Roth, A.; Yu, M.; Morris, R.; Bersani, F.; Rivera, M.N.; Lu, J.; Shioda, T.; Vasudevan, S.; Ramaswamy, S.; et al. The IGF2 intronic miR-483 selectively enhances transcription from IGF2 fetal promoters and enhances tumorigenesis. Genes. Dev. 2013, 27, 2543–2548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Ge, S.; Wang, X.; Yuan, Q.; Yan, Q.; Ye, H.; Che, Y.; Lin, Y.; Zhang, J.; Liu, P. Serum miR-483-5p as a potential biomarker to detect hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatol. Int. 2013, 7, 199–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Lin, J.; Zhao, Y.; Sun, X. Deregulated Expression of miR-483-3p Serves as a Diagnostic Biomarker in Severe Pneumonia Children with Respiratory Failure and Its Predictive Value for the Clinical Outcome of Patients. Mol. Biotechnol. 2022, 64, 311–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coenen-Stass, A.M.L.; Sork, H.; Gatto, S.; Godfrey, C.; Bhomra, A.; Krjutskov, K.; Hart, J.R.; Westholm, J.O.; O’Donovan, L.; Roos, A.; et al. Comprehensive RNA-Sequencing Analysis in Serum and Muscle Reveals Novel Small RNA Signatures with Biomarker Potential for DMD. Mol. Ther. Nucleic Acids 2018, 13, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.; Li, N.; Pu, J.; Zhang, C.; Xu, K.; Wang, W.; Liu, L.; Gao, L.; Xu, X.; Tan, J. The plasma derived exosomal miRNA-483-5p/502-5p serve as potential MCI biomarkers in aging. Exp. Gerontol. 2024, 186, 112355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, M.; Chen, Z.; Martin, M.; Zhang, J.; Sangwung, P.; Woo, B.; Tremoulet, A.H.; Shimizu, C.; Jain, M.K.; Burns, J.C.; et al. miR-483 Targeting of CTGF Suppresses Endothelial-to-Mesenchymal Transition: Therapeutic Implications in Kawasaki Disease. Circ. Res. 2017, 120, 354–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kozomara, A.; Birgaoanu, M.; Griffiths-Jones, S. miRBase: From microRNA sequences to function. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019, 47, D155–D162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Chen, H.; Yun, J.; Song, L.; Ma, X.; Luo, S.; Song, Y. miRNA-483-5p Targets HDCA4 to Regulate Renal Tubular Damage in Diabetic Nephropathy. Horm. Metab. Res. 2021, 53, 562–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menbari, M.N.; Rahimi, K.; Ahmadi, A.; Mohammadi-Yeganeh, S.; Elyasi, A.; Darvishi, N.; Hosseini, V.; Abdi, M. miR-483-3p suppresses the proliferation and progression of human triple negative breast cancer cells by targeting the HDAC8>oncogene. J. Cell Physiol. 2020, 235, 2631–2642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, H.; Yu, Y.; Gu, H.; Qi, B.; Yu, A. MicroRNA-483-5p inhibits osteogenic differentiation of human bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells by targeting the RPL31-mediated RAS/MEK/ERK signaling pathway. Cell Signal. 2022, 93, 110298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bertero, T.; Gastaldi, C.; Bourget-Ponzio, I.; Imbert, V.; Loubat, A.; Selva, E.; Busca, R.; Mari, B.; Hofman, P.; Barbry, P.; et al. miR-483-3p controls proliferation in wounded epithelial cells. FASEB J. 2011, 25, 3092–3105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, Y.; Pan, W.; Xiao, X.; Zhou, X.; Gu, W.; Liu, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Li, L.; Zheng, C.; Liu, J.; et al. MicroRNA-483-5p accentuates cisplatin-induced acute kidney injury by targeting GPX3. Lab. Invest. 2022, 102, 589–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matson, K.; Macleod, A.; Mehta, N.; Sempek, E.; Tang, X. Impacts of MicroRNA-483 on Human Diseases. Noncoding RNA 2023, 9, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pepe, F.; Visone, R.; Veronese, A. The Glucose-Regulated MiR-483-3p Influences Key Signaling Pathways in Cancer. Cancers 2018, 10, 181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scalia, P.; Williams, S.J.; Fujita-Yamaguchi, Y. Human IGF2 Gene Epigenetic and Transcriptional Regulation: At the Core of Developmental Growth and Tumorigenic Behavior. Biomedicines 2023, 11, 1655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veronese, A.; Visone, R.; Consiglio, J.; Acunzo, M.; Lupini, L.; Kim, T.; Ferracin, M.; Lovat, F.; Miotto, E.; Balatti, V.; et al. Mutated beta-catenin evades a microRNA-dependent regulatory loop. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2011, 108, 4840–4845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.; Yang, P.; Zhang, B.; Yao, M.; Jia, Y.; Li, N.; Liu, H.; Bai, H.; Gong, X. Long Noncoding RNA TTC39A-AS1 Promotes Breast Cancer Tumorigenicity by Sponging MicroRNA-483-3p and Thereby Upregulating MTA2. Pharmacology 2021, 106, 573–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Gao, C.; Di, X.; Cui, S.; Liang, W.; Sun, W.; Yao, M.; Liu, S.; Zheng, Z. Hsa_circ_0123190 acts as a competitive endogenous RNA to regulate APLNR expression by sponging hsa-miR-483-3p in lupus nephritis. Arthritis Res. Ther. 2021, 23, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pepe, F.; Pagotto, S.; Soliman, S.; Rossi, C.; Lanuti, P.; Braconi, C.; Mariani-Costantini, R.; Visone, R.; Veronese, A. Regulation of miR-483-3p by the O-linked N-acetylglucosamine transferase links chemosensitivity to glucose metabolism in liver cancer cells. Oncogenesis 2017, 6, e328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Martino, M.; Palma, G.; Azzariti, A.; Arra, C.; Fusco, A.; Esposito, F. The HMGA1 Pseudogene 7 Induces miR-483 and miR-675 Upregulation by Activating Egr1 through a ceRNA Mechanism. Genes 2017, 8, 330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Ruan, Y.; Qin, Z.; Gao, X.; Xu, K.; Shi, X.; Gao, S.; Liu, S.; Zhu, K.; Wang, W.; et al. miR-483-3p, Mediated by KLF9, Functions as Tumor Suppressor in Testicular Seminoma via Targeting MMP9. Front. Oncol. 2020, 10, 596574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naboulsi, R.; Larsson, M.; Andersson, L.; Younis, S. ZBED6 regulates Igf2 expression partially through its regulation of miR483 expression. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 19484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Tan, X.; Wang, L.; Jin, W.; He, Y.; Yan, Y.; Hu, K.; Wang, H.; Xiang, C.; Hou, M.; et al. Identification of the CeRNA axis of circ_0000006/miR-483-5p/KDM2B in the progression of aortic aneurysm to aorta dissection. BMC Cardiovasc. Disord. 2025, 25, 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X.; Tao, Z.; Zhang, Z.; He, W.; Xie, Y.; Zhang, L. The potential role of RAAS-related hsa_circ_0122153 and hsa_circ_0025088 in essential hypertension. Clin. Exp. Hypertens. 2021, 43, 715–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Wang, Z.; Zhao, L.; Wen, M.; Li, J.; Lv, Q.; Wang, F.; Ma, J.; Sun, R.; Tao, Y.; et al. Comprehensive evaluation of circRNAs in cirrhotic cardiomyopathy before and after liver transplantation. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2023, 114, 109495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, P.; Xue, Y. CircRNA hsa_circ_0006859 inhibits the osteogenic differentiation of BMSCs and aggravates osteoporosis by targeting miR-642b-5p/miR-483-3p and upregulating EFNA2/DOCK3. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2023, 116, 109844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, D.; Wu, Z.; Gao, J.; Mei, Q.; Zhang, X.; Wang, B. CircUTRN24/miR-483-3p/IGF-1 Regulates Autophagy Mediated Liver Fibrosis in Biliary Atresia. Mol. Biotechnol. 2024, 66, 1424–1433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, W.; Wei, N.; Shao, G.; Jiang, C.; Zhang, S.; Wang, L. circZNF609 promotes the proliferation and migration of gastric cancer by sponging miR-483-3p and regulating CDK6. Onco Targets Ther 2019, 12, 8197–8205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Dong, X.; Li, X.; Yang, Y.; Li, H.; Hong, Y.; Yang, G.; Kong, X.; Wang, X.; Ma, X. Moxibustion ameliorates chronic inflammatory visceral pain via spinal circRNA-miRNA-mRNA networks: A central mechanism study. Mol. Brain 2024, 17, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Li, J.; Xiao, J.K.; Xiao, L.; Xu, B.W.; Li, C. The lncRNA NEAT1 promotes the epithelial-mesenchymal transition and metastasis of osteosarcoma cells by sponging miR-483 to upregulate STAT3 expression. Cancer Cell Int. 2021, 21, 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Xu, W.; Sun, K.; Wang, F.; Wong, T.W.; Kong, A.N. Identification of novel biomarkers in prostate cancer diagnosis and prognosis. J. Biochem. Mol. Toxicol. 2022, 36, e23137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, C.; Li, S.; Fu, X.; Zhao, X.; Peng, J. LncRNA NR2F1-AS1 was involved in azacitidine resistance of THP-1 cells by targeting IGF1 with miR-483-3p. Cytokine 2023, 162, 156105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, S.; Zheng, K.; Pei, Y.; Wang, W.; Zhang, X. Long noncoding RNA NR2F1-AS1 enhances the malignant properties of osteosarcoma by increasing forkhead box A1 expression via sponging of microRNA-483-3p. Aging 2019, 11, 11609–11623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, L.; Zhang, P.; Lu, Y.; Zhang, A.; Chen, X. LINC00662 Promotes Proliferation and Invasion and Inhibits Apoptosis of Glioma Cells Through miR-483-3p/SOX3 Axis. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2022, 194, 2857–2871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, W.D.; Chang, C.H.; Pan, J.K.; Lin, F.C.; Chen, Y.C.; Chen, Y.J.; Wang, P.S.; Hong, W.Q.; Chen, S.Y.; Lin, C.H.; et al. A novel long non-coding RNA MIR4500HG003 promotes tumor metastasis through miR-483-3p-MMP9 axis in triple-negative breast cancer. Cell Death Dis. 2024, 15, 310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Q.; Ma, J.; Wei, J.; Meng, W.; Wang, Y.; Shi, M. lncRNA SNHG11 Promotes Gastric Cancer Progression by Activating the Wnt/beta-Catenin Pathway and Oncogenic Autophagy. Mol. Ther. 2021, 29, 1258–1278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.; Chen, X.; Fu, C.; Xie, M.; Ouyang, S. Long Non-Coding RNA BCAR4 Promotes Oxaliplatin Resistance in Colorectal Cancer by Modulating miR-484-3p/RAB5C Expression. Chemotherapy 2023, 68, 119–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan, L.; Li, H.; Zhang, Y. LINC00908 negatively regulates microRNA-483-5p to increase TSPYL5 expression and inhibit the development of prostate cancer. Cancer Cell Int. 2020, 20, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.; Cheng, T.; He, Y.; Zhou, S.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, K.; Yu, P. High glucose regulates ERp29 in hepatocellular carcinoma by LncRNA MEG3-miRNA 483-3p pathway. Life Sci. 2019, 232, 116602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, C.L.; Zuo, B.; Li, D.; Zhu, J.F.; Xiao, F.; Zhang, X.L.; Chen, X.D. The long noncoding RNA H19 attenuates force-driven cartilage degeneration via miR-483-5p/Dusp5. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2020, 529, 210–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Gao, N.; Ji, G.; Hu, W.; Bi, R.; Liang, J.; Liu, Y. Static magnetic field contributes to osteogenic differentiation of hPDLSCs through the H19/Wnt/beta-catenin axis. Gene 2025, 933, 148967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Q.; Qiu, T.; Chen, H.; Tian, T.; Wang, D.; Lu, C. Silencing LncRNA SNHG14 alleviates renal tubular injury via the miR-483-5p/HDAC4 axis in diabetic kidney disease. Hormones 2025, 24, 123–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teng, L.; Meng, R. Long Non-Coding RNA MALAT1 Promotes Acute Cerebral Infarction Through miRNAs-Mediated hs-CRP Regulation. J. Mol. Neurosci. 2019, 69, 494–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Li, Y.; Tian, J. Predictive value of lncRNA DBH-AS1 for cardiovascular events in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus with coronary heart disease. Diab Vasc. Dis. Res. 2024, 21, 14791641241303948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, X.; Yang, L.; Liu, X.; Liu, M.; Liu, L.; Liu, J.; Luo, J. Long non-coding RNA small nucleolar RNA host gene 29 drives chronic myeloid leukemia progression via microRNA-483-3p/Casitas B-lineage Lymphoma axis-mediated activation of the phosphoinositide 3-kinase/Akt pathway. Med. Oncol. 2024, 41, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, T.; Lv, X.; Pan, G.; Lu, Y.; Chen, W.; He, W.; Lei, X.; Zhang, H.; Liu, M.; Sun, S.; et al. Long Noncoding RNA MPRL Promotes Mitochondrial Fission and Cisplatin Chemosensitivity via Disruption of Pre-miRNA Processing. Clin. Cancer Res. 2019, 25, 3673–3688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Wu, C.; Li, Y.; Wang, T.; Huang, M.; Wang, M.; Long, L.; Chen, Y.; Feng, S.; Liu, X.; et al. Mir-483-5p-mediated activating of IGF2/H19 enhancer up-regulates IGF2/H19 expression via chromatin loops to promote the malignant progression of hepatocellular carcinoma. Mol. Cancer 2025, 24, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morales, S.; Monzo, M.; Navarro, A. Epigenetic regulation mechanisms of microRNA expression. Biomol. Concepts 2017, 8, 203–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selenou, C.; Brioude, F.; Giabicani, E.; Sobrier, M.L.; Netchine, I. IGF2: Development, Genetic and Epigenetic Abnormalities. Cells 2022, 11, 1886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schagdarsurengin, U.; Lammert, A.; Schunk, N.; Sheridan, D.; Gattenloehner, S.; Steger, K.; Wagenlehner, F.; Dansranjavin, T. Impairment of IGF2 gene expression in prostate cancer is triggered by epigenetic dysregulation of IGF2-DMR0 and its interaction with KLF4. Cell Commun. Signal. 2017, 15, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Hu, J.F.; Wang, H.; Cui, J.; Gao, S.; Hoffman, A.R.; Li, W. CRISPR Cas9-guided chromatin immunoprecipitation identifies miR483 as an epigenetic modulator of IGF2 imprinting in tumors. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 34177–34190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sayers, E.W.; Beck, J.; Bolton, E.E.; Brister, J.R.; Chan, J.; Connor, R.; Feldgarden, M.; Fine, A.M.; Funk, K.; Hoffman, J.; et al. Database resources of the National Center for Biotechnology Information in 2025. Nucleic Acids Res. 2025, 53, D20–D29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, B.; Wang, S.; Wu, W.; Shan, P.; Chen, Y.; Meng, J.; Xing, L.; Yun, J.; Hao, L.; Wang, X.; et al. Mechanisms of circRNA/lncRNA-miRNA interactions and applications in disease and drug research. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2023, 162, 114672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perge, P.; Nyiro, G.; Vekony, B.; Igaz, P. Liquid biopsy for the assessment of adrenal cancer heterogeneity: Where do we stand? Endocrine 2022, 77, 425–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loo, J.M.; Scherl, A.; Nguyen, A.; Man, F.Y.; Weinberg, E.; Zeng, Z.; Saltz, L.; Paty, P.B.; Tavazoie, S.F. Extracellular metabolic energetics can promote cancer progression. Cell 2015, 160, 393–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Xu, Y.M.; Zou, Y.Q.; Lin, J.; Huang, B.; Liu, J.; Li, J.; Zhang, J.; Yang, W.M.; Min, Q.H.; et al. Identification of differential expressed PE exosomal miRNA in lung adenocarcinoma, tuberculosis, and other benign lesions. Medicine 2017, 96, e8361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Zhang, X.; Zhong, X.; Zhang, M.; Guo, M.; Yang, L.; Li, Y.; Zhao, J.; Yu, S. Effect of miR-483-5p on apoptosis of lung cancer cells through targeting of RBM5. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Pathol. 2018, 11, 3147–3156. [Google Scholar]

- Niture, S.; Gadi, S.; Qi, Q.; Gyamfi, M.A.; Varghese, R.S.; Rios-Colon, L.; Chimeh, U.; Vandana; Ressom, H.W.; Kumar, D. MicroRNA-483-5p Inhibits Hepatocellular Carcinoma Cell Proliferation, Cell Steatosis, and Fibrosis by Targeting PPARalpha and TIMP2. Cancers 2023, 15, 1715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, N.; Li, F.; Li, D.; Hui, Y.; Wang, X.; Qiao, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Xiang, Y.; Zhou, J.; Zhou, L.; et al. Igf2-derived intronic miR-483 promotes mouse hepatocellular carcinoma cell proliferation. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 2012, 361, 337–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, X.Y.; Chen, D.; Gu, X.Y.; Ding, J.; Zhao, Y.J.; Zhao, Q.; Yao, M.; Chen, Z.; He, X.H.; Cong, W.M. Predicting Value of ALCAM as a Target Gene of microRNA-483-5p in Patients with Early Recurrence in Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Front. Pharmacol. 2017, 8, 973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, S.; Chen, Y.; Feng, S.; Yi, T.; Liu, X.; Li, Q.; Liu, Z.; Zhu, C.; Hu, J.; Yu, X.; et al. MiR-483-5p promotes IGF-II transcription and is associated with poor prognosis of hepatocellular carcinoma. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 99871–99888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cui, K.; Zhang, H.; Wang, G.Z. MiR-483 suppresses cell proliferation and promotes cell apoptosis by targeting SOX3 in breast cancer. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 2019, 23, 2069–2074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, L.; Zhang, X.; Huang, Y.Z.; Zhu, Y.L.; Xu, L.Y.; Li, Z.; Dai, X.Y.; Shi, L.; Zhou, X.J.; Wei, J.F.; et al. Metformin exhibits antiproliferation activity in breast cancer via miR-483-3p/METTL3/m(6)A/p21 pathway. Oncogenesis 2021, 10, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozata, D.M.; Caramuta, S.; Velazquez-Fernandez, D.; Akcakaya, P.; Xie, H.; Hoog, A.; Zedenius, J.; Backdahl, M.; Larsson, C.; Lui, W.O. The role of microRNA deregulation in the pathogenesis of adrenocortical carcinoma. Endocr. Relat. Cancer 2011, 18, 643–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agosta, C.; Laugier, J.; Guyon, L.; Denis, J.; Bertherat, J.; Libe, R.; Boisson, B.; Sturm, N.; Feige, J.J.; Chabre, O.; et al. MiR-483-5p and miR-139-5p promote aggressiveness by targeting N-myc downstream-regulated gene family members in adrenocortical cancer. Int. J. Cancer 2018, 143, 944–957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Liu, L.; Deng, X.; Li, D.; Cai, H.; Ma, Y.; Jia, C.; Wu, B.; Fan, Y.; Lv, Z. MicroRNA 483-3p targets Pard3 to potentiate TGF-beta1-induced cell migration, invasion, and epithelial-mesenchymal transition in anaplastic thyroid cancer cells. Oncogene 2019, 38, 699–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, K.; Wang, J.; He, J.; Chen, Q.; Yang, L. miR-483-3p promotes proliferation and migration of neuroblastoma cells by targeting PUMA. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Pathol. 2018, 11, 490–501. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, L.; Shi, M.; Hou, S.; Ding, B.; Liu, L.; Ji, X.; Zhang, J.; Deng, Y. MiR-483-5p suppresses the proliferation of glioma cells via directly targeting ERK1. FEBS Lett. 2012, 586, 1312–1317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uhlmann, E.J.; Mackel, C.E.; Deforzh, E.; Rabinovsky, R.; Brastianos, P.K.; Varma, H.; Vega, R.A.; Krichevsky, A.M. Inhibition of the epigenetically activated miR-483-5p/IGF-2 pathway results in rapid loss of meningioma tumor cell viability. J. Neurooncol. 2023, 162, 109–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.; Wang, H.; Zhu, S.; Lan, X. miR-483-5p promotes esophageal cancer progression by targeting KCNQ1. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2020, 531, 615–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, J.; Li, X.; Wang, W.; Li, W.; Gao, S.; Yan, J. Mir-483-5p promotes the malignant transformation of immortalized human esophageal epithelial cells by targeting HNF4A. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Pathol. 2017, 10, 9391–9399. [Google Scholar]

- Duan, L.; Ma, J.; Yang, W.; Cao, L.; Wang, X.; Niu, L.; Li, Y.; Zhou, W.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, J.; et al. EI24 Inhibits Cell Proliferation and Drug Resistance of Esophageal Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Front. Oncol. 2020, 10, 1570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Hong, L.; Xu, G.; Hao, J.; Wang, R.; Guo, H.; Liu, J.; Zhang, Y.; Nie, Y.; Fan, D. miR-483-3p plays an oncogenic role in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma by targeting tumor suppressor EI24. Cell Biol. Int. 2016, 40, 448–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.G.; Ma, X.D.; He, Z.H.; Guo, Y.X. miR-483-5p promotes prostate cancer cell proliferation and invasion by targeting RBM5. Int. Braz. J. Urol. 2017, 43, 1060–1067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arrighetti, N.; Cossa, G.; De Cecco, L.; Stucchi, S.; Carenini, N.; Corna, E.; Gandellini, P.; Zaffaroni, N.; Perego, P.; Gatti, L. PKC-alpha modulation by miR-483-3p in platinum-resistant ovarian carcinoma cells. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2016, 310, 9–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rattanapan, Y.; Korkiatsakul, V.; Kongruang, A.; Siriboonpiputtana, T.; Rerkamnuaychoke, B.; Chareonsirisuthigul, T. High Expression of miR-483-5p Predicts Chemotherapy Resistance in Epithelial Ovarian Cancer. Microrna 2021, 10, 51–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castro-Vega, L.J.; Calsina, B.; Burnichon, N.; Drossart, T.; Martinez-Montes, A.M.; Verkarre, V.; Amar, L.; Bertherat, J.; Rodriguez-Antona, C.; Favier, J.; et al. Overexpression of miR-483-5p is confined to metastases and linked to high circulating levels in patients with metastatic pheochromocytoma/paraganglioma. Clin. Transl. Med. 2020, 10, e260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, F.Y.; Zhou, C.Y.; Liu, Y.B.; Wang, B.; Mao, L.; Li, Y. miR-483 is down-regulated in gastric cancer and suppresses cell proliferation, invasion and protein O-GlcNAcylation by targeting OGT. Neoplasma 2018, 65, 406–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, K.; He, B.; Xu, J.; Li, Y.; Guo, C.; Cai, Q.; Wang, S. miR-483-5p Targets MKNK1 to Suppress Wilms’ Tumor Cell Proliferation and Apoptosis In Vitro and In Vivo. Med. Sci. Monit. 2019, 25, 1459–1468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, S.; Chen, W.X.; Lv, X.B.; Tang, Q.L.; Sun, L.J.; Liu, B.D.; Zhong, J.L.; Lin, Z.Y.; Wang, Y.Y.; Li, Q.X.; et al. miR-483-5p determines mitochondrial fission and cisplatin sensitivity in tongue squamous cell carcinoma by targeting FIS1. Cancer Lett. 2015, 362, 183–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, Y.; Jia, H.; Hu, A.; Liu, R.; Zeng, X.; Wang, H. Nanoparticles Targeting Delivery Antagomir-483-5p to Bone Marrow Mesenchymal Stem Cells Treat Osteoporosis by Increasing Bone Formation. Curr. Stem. Cell Res. Ther. 2023, 18, 115–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Li, L.; Zhu, L.; Zhang, C.; Li, Z.; Guo, Y.; Nie, Y.; Luo, Z. Bu-Shen-Huo-Xue-Fang modulates nucleus pulposus cell proliferation and extracellular matrix remodeling in intervertebral disk degeneration through miR-483 regulation of Wnt pathway. J. Cell. Biochem. 2019, 120, 19318–19329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, K.; He, H.; Xie, Y.; Zhao, L.; Zhao, S.; Wan, X.; Yang, W.; Mo, Z. miR-125a-3p and miR-483-5p promote adipogenesis via suppressing the RhoA/ROCK1/ERK1/2 pathway in multiple symmetric lipomatosis. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 11909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhi, Z.; Zhu, H.; Lv, X.; Lu, C.; Li, Y.; Wu, F.; Zhou, L.; Li, H.; Tang, W. IGF2-derived miR-483-3p associated with Hirschsprung’s disease by targeting FHL1. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2018, 22, 4913–4921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, G.; Guo, F.; Wang, H.; Liu, W.; Zhang, L.; Cui, M.; Wu, X. Downregulation of microRNA-483-5p Promotes Cell Proliferation and Invasion by Targeting GFRA4 in Hirschsprung’s Disease. DNA Cell Biol. 2017, 36, 930–937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, J.; Wan, J.; Huang, H.-Y.; Chen, Y.; Huang, Y.; Huang, J.; Zhang, Z.; Su, C.; Zhou, Y.; Lin, X. miRStart 2.0: Enhancing miRNA regulatory insights through deep learning-based TSS identification. Nucleic Acids Res. 2025, 53, D138–D146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, Z.; Cui, Q.; Wang, J.; Zhou, Y. TransmiR v2.0: An updated transcription factor-microRNA regulation database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019, 47, D253–D258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bertero, T.; Bourget-Ponzio, I.; Puissant, A.; Loubat, A.; Mari, B.; Meneguzzi, G.; Auberger, P.; Barbry, P.; Ponzio, G.; Rezzonico, R. Tumor suppressor function of miR-483-3p on squamous cell carcinomas due to its pro-apoptotic properties. Cell Cycle 2013, 12, 2183–2193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guled, M.; Lahti, L.; Lindholm, P.M.; Salmenkivi, K.; Bagwan, I.; Nicholson, A.G.; Knuutila, S. CDKN2A, NF2, and JUN are dysregulated among other genes by miRNAs in malignant mesothelioma -A miRNA microarray analysis. Genes Chromosomes Cancer 2009, 48, 615–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertero, T.; Gastaldi, C.; Bourget-Ponzio, I.; Mari, B.; Meneguzzi, G.; Barbry, P.; Ponzio, G.; Rezzonico, R. CDC25A targeting by miR-483-3p decreases CCND-CDK4/6 assembly and contributes to cell cycle arrest. Cell Death Differ. 2013, 20, 800–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chow, J.T.; Desjardins, A.; Lee, D.K.C.; Grigore, I.A.; Lee, L.; Fu, N.J.; Chau, S.; Lee, B.Y.; Gabra, M.M.; Salmena, L. A microRNA CRISPR screen reveals microRNA-483-3p as an apoptotic regulator in prostate cancer cells. Cell Death Dis. 2025, 16, 752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veronese, A.; Lupini, L.; Consiglio, J.; Visone, R.; Ferracin, M.; Fornari, F.; Zanesi, N.; Alder, H.; D’Elia, G.; Gramantieri, L.; et al. Oncogenic role of miR-483-3p at the IGF2/483 locus. Cancer Res. 2010, 70, 3140–3149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lupini, L.; Pepe, F.; Ferracin, M.; Braconi, C.; Callegari, E.; Pagotto, S.; Spizzo, R.; Zagatti, B.; Lanuti, P.; Fornari, F.; et al. Over-expression of the miR-483-3p overcomes the miR-145/TP53 pro-apoptotic loop in hepatocellular carcinoma. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 31361–31371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, J.; Yang, Z.; Zhou, H.; Yue, J.; Mu, T.; Zhang, Q.; Bi, X. Upregulation of DKK3 by miR-483-3p plays an important role in the chemoprevention of colorectal cancer mediated by black raspberry anthocyanins. Mol. Carcinog. 2020, 59, 168–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, J.; Zhang, S.; Zhou, Y.; Hu, X.; Shao, C. MicroRNA 483-3p suppresses the expression of DPC4/Smad4 in pancreatic cancer. FEBS Lett. 2011, 585, 207–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, H.; Zhang, Y.; Yan, J.; Ban, X.; Fan, X.; Chang, X.; Lu, Z.; Wu, Y.; Zong, L.; Mo, S.; et al. Upregulated MicroRNA-483-3p is an Early Event in Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma (PDAC) and as a Powerful Liquid Biopsy Biomarker in PDAC. Onco Targets Ther. 2021, 14, 2163–2175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, S.; Yu, Z.; Zhang, X.; Sui, L. MiR-483 Targeted SOX3 to Suppress Glioma Cell Migration, Invasion and Promote Cell Apoptosis. Onco Targets Ther. 2020, 13, 2153–2161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Che, G.; Gao, H.; Tian, J.; Hu, Q.; Xie, H.; Zhang, Y. MicroRNA-483-3p Promotes Proliferation, Migration, and Invasion and Induces Chemoresistance of Wilms’ Tumor Cells. Pediatr. Dev. Pathol. 2020, 23, 144–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagaraj, S.; Stankiewicz-Drogon, A.; Darzynkiewicz, E.; Wojda, U.; Grzela, R. miR-483-5p orchestrates the initiation of protein synthesis by facilitating the decrease in phosphorylated Ser209eIF4E and 4E-BP1 levels. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 4237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Zhang, Z.; Liu, Z.; Mu, G.; Xie, Q.; Zhou, S.; Wang, Z.; Cao, Y.; Tan, Y.; Wei, X.; et al. Circulating miR-320a-3p and miR-483-5p level associated with pharmacokinetic-pharmacodynamic profiles of rivaroxaban. Hum. Genom. 2022, 16, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Love, M.I.; Huber, W.; Anders, S. Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol. 2014, 15, 550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robinson, M.D.; McCarthy, D.J.; Smyth, G.K. edgeR: A Bioconductor package for differential expression analysis of digital gene expression data. Bioinformatics 2010, 26, 139–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Law, C.W.; Chen, Y.; Shi, W.; Smyth, G.K. voom: Precision weights unlock linear model analysis tools for RNA-seq read counts. Genome Biol. 2014, 15, R29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lewis, B.P.; Burge, C.B.; Bartel, D.P. Conserved seed pairing, often flanked by adenosines, indicates that thousands of human genes are microRNA targets. Cell 2005, 120, 15–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wingender, E.; Chen, X.; Hehl, R.; Karas, H.; Liebich, I.; Matys, V.; Meinhardt, T.; Pruss, M.; Reuter, I.; Schacherer, F. TRANSFAC: An integrated system for gene expression regulation. Nucleic Acids Res 2000, 28, 316–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howe, K.L.; Achuthan, P.; Allen, J.; Allen, J.; Alvarez-Jarreta, J.; Amode, M.R.; Armean, I.M.; Azov, A.G.; Bennett, R.; Bhai, J.; et al. Ensembl 2021. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021, 49, D884–D891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y.; Li, M.; Wang, J.; Pan, Y.; Wu, F.X. CytoNCA: A cytoscape plugin for centrality analysis and evaluation of protein interaction networks. Biosystems 2015, 127, 67–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gyorffy, B. Discovery and ranking of the most robust prognostic biomarkers in serous ovarian cancer. Geroscience 2023, 45, 1889–1898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fountain, J.H.; Kaur, J.; Lappin, S.L. Physiology, Renin Angiotensin System. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Kemp, J.R.; Unal, H.; Desnoyer, R.; Yue, H.; Bhatnagar, A.; Karnik, S.S. Angiotensin II-regulated microRNA 483-3p directly targets multiple components of the renin-angiotensin system. J. Mol. Cell Cardiol. 2014, 75, 25–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan, J.; Liu, S.; Ye, W.; Zhang, X.; Shi, W. miR-483-5p-Containing exosomes treatment ameliorated deep vein thrombosis-induced inflammatory response. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 2024, 202, 114384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; He, Y.; Yan, X.; Chen, S.; He, M.; Lei, Y.; Zhang, J.; Gongol, B.; Gu, M.; Miao, Y.; et al. MicroRNA-483 amelioration of experimental pulmonary hypertension. EMBO Mol. Med. 2020, 12, e11303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Z.; Tang, W.; Guo, J.; Sun, S. miR-483-5p plays a protective role in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Int. J. Mol. Med. 2017, 40, 193–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, H.; Liang, H.; Gao, Z.; Zhang, X.; He, Q.; He, C.; Cai, C.; Chen, J. MiR-483-5p downregulation alleviates ox-LDL induced endothelial cell injury in atherosclerosis. BMC Cardiovasc. Disord. 2023, 23, 521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Q.; Zhan, H.; Liu, C.; Zhang, C.; Wei, H.; Li, B.; Zhou, D.; Lu, Y.; Huang, S.; Cheng, J.; et al. Neuroprotective Effect of miR-483-5p Against Cardiac Arrest-Induced Mitochondrial Dysfunction Mediated Through the TNFSF8/AMPK/JNK Signaling Pathway. Cell Mol. Neurobiol. 2023, 43, 2179–2202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuschnerus, K.; Straessler, E.T.; Muller, M.F.; Luscher, T.F.; Landmesser, U.; Krankel, N. Increased Expression of miR-483-3p Impairs the Vascular Response to Injury in Type 2 Diabetes. Diabetes 2019, 68, 349–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, H.; He, M.; Yang, Q.; Niu, F.; Zou, Y.; Liu, C.; Yang, Y.; Liu, A.; Chang, X.; Chen, F.; et al. Obesity-induced upregulation of miR-483-5p impairs the function and identity of pancreatic beta-cells. Diabetes Obes. Metab. 2024, 26, 4510–4521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abudoureyimu, M.; Tayier, T.; Zhang, L. The role and mechanism of action of miR-483-3p in mediating the effects of IGF-1 on human renal tubular epithelial cells induced by high glucose. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 15635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Liu, F.; Li, Z.; Pan, S.; Xie, J.; Zhao, Z.; Liu, Z.; Zhang, J.; Liu, Z. HNRNPA1-mediated exosomal sorting of miR-483-5p out of renal tubular epithelial cells promotes the progression of diabetic nephropathy-induced renal interstitial fibrosis. Cell Death Dis. 2021, 12, 255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, L.; Liu, S.; Zhao, W.; Shi, J. miR-483-5p and miR-486-5p are down-regulated in cumulus cells of metaphase II oocytes from women with polycystic ovary syndrome. Reprod. Biomed. Online 2015, 31, 565–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Chen, M.; Wang, J.; Lu, L.; Li, X.; Le, Y. MicroRNA profiling in Chinese children with Henoch-Schonlein purpura and association between selected microRNAs and inflammatory biomarkers. Acta Paediatr. 2021, 110, 2221–2229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferland-McCollough, D.; Fernandez-Twinn, D.S.; Cannell, I.G.; David, H.; Warner, M.; Vaag, A.A.; Bork-Jensen, J.; Brons, C.; Gant, T.W.; Willis, A.E.; et al. Programming of adipose tissue miR-483-3p and GDF-3 expression by maternal diet in type 2 diabetes. Cell Death Differ. 2012, 19, 1003–1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Mohan, R.; Chen, X.; Matson, K.; Waugh, J.; Mao, Y.; Zhang, S.; Li, W.; Tang, X.; Satin, L.S.; et al. microRNA-483 Protects Pancreatic beta-Cells by Targeting ALDH1A3. Endocrinology 2021, 162, bqab031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, J.; He, M.; Li, J.; Pessentheiner, A.; Wang, C.; Zhang, J.; Sun, Y.; Wang, W.T.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, J.; et al. microRNA-483 ameliorates hypercholesterolemia by inhibiting PCSK9 production. JCI Insight 2020, 5, e143812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, X.; Bai, X.; Han, Y.; Ye, Y.; Peng, M.; Cui, H.; Li, K. PPAR gamma changing ALDH1A3 content to regulate lipid metabolism and inhibit lung cancer cell growth. Mol. Genet. Genom. 2025, 300, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, Y.; Chen, X.; Yang, X.; Zhang, H.; Li, X.; Wang, Z.; Feng, S.; Wen, W.; Xiong, X. miRNA transcriptomics analysis shows miR-483-5p and miR-503-5p targeted miRNA in extracellular vesicles from severe acute pancreatitis-associated lung injury patients. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2023, 125, 111075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Park, S.; Lee, H.; Kwon, E.J.; Park, H.R.; Kim, Y.H.; Lee, S.G. Exosomal hsa-miR-335-5p and hsa-miR-483-5p are novel biomarkers for rheumatoid arthritis: A development and validation study. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2023, 120, 110286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z.; Qin, X.; Yuan, J.; Yin, H.; Qu, R.; Zhong, C.; Ding, W. MicroRNA-483-3p Inhibitor Ameliorates Sepsis-Induced Intestinal Injury by Attenuating Cell Apoptosis and Cytotoxicity Via Regulating HIPK2. Mol. Biotechnol. 2024, 66, 233–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X.; Guo, L.; Du, J.; Luo, Z.; Xu, J.; Bhawal, U.K.; Li, X.; Liu, Y. Macrophage-derived apoptotic bodies impair the osteogenic ability of osteoblasts in periodontitis. Oral. Dis. 2024, 30, 3296–3307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chouri, E.; Servaas, N.H.; Bekker, C.P.J.; Affandi, A.J.; Cossu, M.; Hillen, M.R.; Angiolilli, C.; Mertens, J.S.; van den Hoogen, L.L.; Silva-Cardoso, S.; et al. Serum microRNA screening and functional studies reveal miR-483-5p as a potential driver of fibrosis in systemic sclerosis. J. Autoimmun. 2018, 89, 162–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maemura, T.; Fukuyama, S.; Sugita, Y.; Lopes, T.J.S.; Nakao, T.; Noda, T.; Kawaoka, Y. Lung-Derived Exosomal miR-483-3p Regulates the Innate Immune Response to Influenza Virus Infection. J. Infect. Dis. 2018, 217, 1372–1382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, L.; Luo, Q.Q.; Peng, M.G.; Zhang, Y.; Zhu, X.H. miR-483 is downregulated in pre-eclampsia via targeting insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF1) and regulates the PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway of endothelial progenitor cells. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. Res. 2021, 47, 63–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagaraj, S.; Want, A.; Laskowska-Kaszub, K.; Fesiuk, A.; Vaz, S.; Logarinho, E.; Wojda, U. Candidate Alzheimer’s Disease Biomarker miR-483-5p Lowers TAU Phosphorylation by Direct ERK1/2 Repression. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 3653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mucha, M.; Skrzypiec, A.E.; Kolenchery, J.B.; Brambilla, V.; Patel, S.; Labrador-Ramos, A.; Kudla, L.; Murrall, K.; Skene, N.; Dymicka-Piekarska, V.; et al. miR-483-5p offsets functional and behavioural effects of stress in male mice through synapse-targeted repression of Pgap2 in the basolateral amygdala. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 2134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, G.; Wang, X.; Liu, C. MiR-483-3p improves learning and memory abilities via XPO1 in Alzheimer’s disease. Brain Behav. 2022, 12, e2680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, F.; Xu, Y.; Ouyang, Y.; Wen, Z.; Zheng, G.; Wan, T.; Sun, G. Silencing of miR-483-5p alleviates postmenopausal osteoporosis by targeting SATB2 and PI3K/AKT pathway. Aging 2021, 13, 6945–6956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, B.; Peng, K.; Wang, G.; Chen, W.; Liu, P.; Chen, F.; Kang, Y. miR-483-3p promotes the osteogenesis of human osteoblasts by targeting Dikkopf 2 (DKK2) and the Wnt signaling pathway. Int. J. Mol. Med. 2020, 46, 1571–1581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Y.; Guo, Q.; Jiang, T.J.; Yuan, Y.; Yang, L.; Wang, G.W.; Xiao, W.F. miR-483-3p regulates osteogenic differentiation of bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells by targeting STAT1. Mol. Med. Rep. 2019, 20, 4558–4566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anderson, B.A.; McAlinden, A. miR-483 targets SMAD4 to suppress chondrogenic differentiation of human mesenchymal stem cells. J. Orthop. Res. 2017, 35, 2369–2377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diaz-Prado, S.; Cicione, C.; Muinos-Lopez, E.; Hermida-Gomez, T.; Oreiro, N.; Fernandez-Lopez, C.; Blanco, F.J. Characterization of microRNA expression profiles in normal and osteoarthritic human chondrocytes. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 2012, 13, 144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, K.; Chen, S.; Cai, P.; Chen, K.; Li, L.; Yang, X.; Yi, J.; Luo, X.; Du, Y.; Zheng, H. MiRNA-483-5p is involved in the pathogenesis of osteoporosis by promoting osteoclast differentiation. Mol. Cell Probes 2020, 49, 101479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Hou, L.; Yuan, X.; Xu, N.; Zhao, S.; Yang, L.; Zhang, N. miR-483-3p promotes cell proliferation and suppresses apoptosis in rheumatoid arthritis fibroblast-like synoviocytes by targeting IGF-1. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2020, 130, 110519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, B.; Zhang, Y.W.; Tong, X.H.; Liu, Y.S. Characterization of microRNA profile in human cumulus granulosa cells: Identification of microRNAs that regulate Notch signaling and are associated with PCOS. Mol. Cell Endocrinol. 2015, 404, 26–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, J.; Yang, A.; Cheng, S.; Feng, L.; Wu, X.; Lu, X.; Zu, M.; Cui, J.; Yu, H.; Zou, L. Circulating miR-19a-3p and miR-483-5p as Novel Diagnostic Biomarkers for the Early Diagnosis of Gastric Cancer. Med. Sci. Monit. 2020, 26, e923444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oreglia, M.; Sbiera, S.; Fassnacht, M.; Guyon, L.; Denis, J.; Cristante, J.; Chabre, O.; Cherradi, N. Early Postoperative Circulating miR-483-5p Is a Prognosis Marker for Adrenocortical Cancer. Cancers 2020, 12, 724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Decmann, A.; Bancos, I.; Khanna, A.; Thomas, M.A.; Turai, P.; Perge, P.; Pinter, J.Z.; Toth, M.; Patocs, A.; Igaz, P. Comparison of plasma and urinary microRNA-483-5p for the diagnosis of adrenocortical malignancy. J. Biotechnol. 2019, 297, 49–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gu, J.; Wang, M.; Wang, X.; Li, J.; Liu, H.; Lin, Z.; Yang, X.; Zhang, X.; Liu, H. Exosomal miR-483-5p in Bone Marrow Mesenchymal Stem Cells Promotes Malignant Progression of Multiple Myeloma by Targeting TIMP2. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2022, 10, 862524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tian, Y.; Yan, M.; Zheng, J.; Li, R.; Lin, J.; Xu, A.; Liang, Y.; Zheng, R.; Yuan, Y. miR-483-5p decreases the radiosensitivity of nasopharyngeal carcinoma cells by targeting DAPK1. Lab. Invest. 2019, 99, 602–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.Z.; Tu, Y.J.; Zhou, T.; Zhang, J.B.; Xiao, R.W.; Yang, D.W.; Zhang, P.F.; You, P.T.; Zheng, X.H. MicroRNA-483-5p Predicts Poor Prognosis and Promotes Cancer Metastasis by Targeting EGR3 in Nasopharyngeal Carcinoma. Front. Oncol. 2021, 11, 720835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martino, M.T.D.; Tagliaferri, P.; Tassone, P. MicroRNA in cancer therapy: Breakthroughs and challenges in early clinical applications. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2025, 44, 126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, J.; Lv, D.; Wang, C.; Li, L.; Zhao, Q.; Chen, H.; Xu, L. Epigenetic silencing of miR-483-3p promotes acquired gefitinib resistance and EMT in EGFR-mutant NSCLC by targeting integrin beta3. Oncogene 2018, 37, 4300–4312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sukocheva, O.A.; Liu, J.; Neganova, M.E.; Beeraka, N.M.; Aleksandrova, Y.R.; Manogaran, P.; Grigorevskikh, E.M.; Chubarev, V.N.; Fan, R. Perspectives of using microRNA-loaded nanocarriers for epigenetic reprogramming of drug resistant colorectal cancers. Semin. Cancer Biol. 2022, 86, 358–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koh, H.B.; Kim, H.J.; Kang, S.W.; Yoo, T.H. Exosome-Based Drug Delivery: Translation from Bench to Clinic. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15, 2042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valinezhad Orang, A.; Safaralizadeh, R.; Kazemzadeh-Bavili, M. Mechanisms of miRNA-Mediated Gene Regulation from Common Downregulation to mRNA-Specific Upregulation. Int. J. Genomics 2014, 2014, 970607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Catalanotto, C.; Cogoni, C.; Zardo, G. MicroRNA in Control of Gene Expression: An Overview of Nuclear Functions. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2016, 17, 1712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brodersen, P.; Voinnet, O. Revisiting the principles of microRNA target recognition and mode of action. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2009, 10, 141–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diener, C.; Keller, A.; Meese, E. The miRNA-target interactions: An underestimated intricacy. Nucleic Acids Res. 2024, 52, 1544–1557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, H.; Ni, H.; Liu, Y.; Yuan, Y.; Xi, T.; Li, X.; Zheng, L. RNA-binding proteins in tumor progression. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2020, 13, 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ala, U. Competing Endogenous RNAs, Non-Coding RNAs and Diseases: An Intertwined Story. Cells 2020, 9, 1574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bazrgar, M.; Mirmotalebisohi, S.A.; Ahmadi, M.; Azimi, P.; Dargahi, L.; Zali, H.; Ahmadiani, A. Comprehensive analysis of lncRNA-associated ceRNA network reveals novel potential prognostic regulatory axes in glioblastoma multiforme. J. Cell Mol. Med. 2024, 28, e18392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Topatana, W.; Juengpanich, S.; Li, S.; Cao, J.; Hu, J.; Lee, J.; Suliyanto, K.; Ma, D.; Zhang, B.; Chen, M.; et al. Advances in synthetic lethality for cancer therapy: Cellular mechanism and clinical translation. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2020, 13, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reda El Sayed, S.; Cristante, J.; Guyon, L.; Denis, J.; Chabre, O.; Cherradi, N. MicroRNA Therapeutics in Cancer: Current Advances and Challenges. Cancers 2021, 13, 2680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, G.; Zhang, X.; Meng, L.; Dong, K.; Shang, S.; Jiang, T.; Liu, Z.; Gao, H. Single-cell RNA-sequencing reveals a unique landscape of the tumor microenvironment in obesity-associated breast cancer. Oncogene 2024, 43, 3277–3290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Shi, X.; Chang, W.; Li, Y.; Wang, L.; Wang, L. Epigenetic alterations of the Igf2 promoter and the effect of miR-483-5p on its target gene expression in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Mol. Med. Rep. 2018, 17, 2251–2256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Upstream Regulator | Regulation Mode | miRNA Isoform | Downstream Target/Pathway | Functional Effect | Related Disease/State | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Transcription Factor Regulation | ||||||

| CTNNB1/USF1 | Activation | miR-483 | BBC3/PUMA (repressed) | Enhances tumor progression and chemoresistance | Cancers | [42,44,47] |

| EGR1 | Activation | miR-483 | Not Specified | Associated with tumor progression, poor prognosis | Human carcinomas | [48] |

| KLF4 | Activation | miR-483 | CTGF (derepressed) | Suppress EMT | Kawasaki disease | [34] |

| KLF9 | Activation | miR-483-3p | MMP9 (repressed) | Inhibits cancer cell proliferation and invasion | Testicular seminoma | [49] |

| ZBED6 | Repression | miR-483 | PI3K-Akt signaling | Represses IGF2 and miR-483 expression | Muscle hypertrophy, Cancers | [50] |

| WT1 | Repression | miR-483 | ERK signaling | Induce mesenchyme differentiation | Cancers | [42] |

| Circular RNA Regulation | ||||||

| circ_0000006 | Sequestration | miR-483-5p | KDM2B (derepressed) | Promotes VSMC proliferation & phenotypic switching | Aortic dissection | [51] |

| circ_0122153 | Sequestration | miR-483-3p | RAAS signaling | Elevated blood pressure | Essential hypertension | [52] |

| circ_0123190 | Sequestration | miR-483-3p | APLNR (repressed) | Exacerbates renal inflammation and fibrosis | Lupus nephritis | [46] |

| circ-ASAP1 | Sequestration | miR-483-3p | mTOR/MAPK signaling | Contributes to cardiac dysfunction | Cirrhotic cardiomyopathy | [53] |

| circ_0006859 | Sequestration | miR-483-3p | EFNA2, DOCK3 (derepressed) | Inhibits osteogenic differentiation of BMSCs, promotes bone loss | Osteoporosis (post-menopausal) | [54] |

| circUTRN24 | Sequestration | miR-483-3p | IGF1 (derepressed) | Influences fibrosis progression, HSC autophagy | Biliary atresia (liver fibrosis) | [55] |

| circZNF609 | Sequestration | miR-483-3p | CDK6 (derepressed) | Promotes the proliferation and migration of gastric cancer | Gastric cancer | [56] |

| circRNA_02767 | Sequestration | miR-483-3p | GFAP (derepressed) | Alleviates central sensitization, reduces neuropathic pain | Chronic inflammatory visceral pain/Neuropathic pain | [57] |

| Long Non-coding RNA Regulation | ||||||

| NEAT1 | Sequestration | miR-483-3p | STAT3 (derepressed) | Promotes EMT, metastasis | Osteosarcoma | [58] |

| NEAT1 | Sequestration | miR-483-3p | UBE2C (derepressed) | Associated with progression, biomarker potential | Prostate cancer | [59] |

| NR2F1-AS1 | Sequestration | miR-483-3p | IGF1 (derepressed) | Fosters azacitidine resistance | Acute myeloid leukemia | [60] |

| NR2F1-AS1 | Sequestration | miR-483-3p | FOXA1 (derepressed) | Drives malignant progression | Osteosarcoma | [61] |

| LINC00662 | Sequestration | miR-483-3p | SOX3 (derepressed) | Promoted tumor proliferation and invasiveness | Glioma | [62] |

| MIR4500HG003 | Sequestration | miR-483-3p | MMP9 (derepressed) | Enhances metastasis | Triple-negative breast cancer | [63] |

| SNHG11 | Sequestration | miR-483-3p | CTNNB1, ATG12 (derepressed) | Facilitates oncogenic autophagy | Gastric cancer | [64] |

| BCAR4 | Sequestration | miR-483-3p | RAB5C (derepressed) | Enhances chemotherapy resistance (Oxaliplatin) | Colorectal cancer | [65] |

| TTC39A-AS1 | Sequestration | miR-483-3p | MTA2 (derepressed) | Promoted proliferation and metastasis | Breast cancer | [45] |

| LINC00908 | Sequestration | miR-483-5p | TSPYL5 (derepressed) | Inhibits proliferation and metastasis | Prostate Cancer | [66] |

| MEG3 | Sequestration | miR-483-3p | ERp29 (derepressed) | Promotes proliferation and migration | Hepatocellular carcinoma | [67] |

| H19 | Sequestration | miR-483-5p | DUSP5 (derepressed) | Mitigates mechanical stress-induced cartilage degradation | Developmental dysplasia of the hip/Osteoarthritis | [68] |

| H19 | Sequestration | miR-483-3p | Wnt/β-catenin signaling | Promotes osteogenic differentiation | Osteogenic differentiation | [69] |

| SNHG14 | Sequestration | miR-483-5p | HDAC4 (derepressed) | Exacerbates renal tubular damage, inflammation, fibrosis | Diabetic kidney disease | [70] |

| MALAT1 | Sequestration | miR-483-3p | hs-CRP (derepressed) | Enhances inflammation | Acute cerebral infarction | [71] |

| DBH-AS1 | Sequestration | miR-483-5p | HCAEC function (proliferation, apoptosis, inflammation) | Influences endothelial dysfunction, predicts CV events | Type 2 diabetes mellitus/Coronary heart disease | [72] |

| SNHG29 | Sequestration | miR-483-3p | CBL (derepressed) | Drives progression | Chronic myeloid leukemia | [73] |

| MPRL | Sequestration | miR-483-5p | FIS1 (derepressed) | Enhances cisplatin sensitivity | Tongue squamous cell carcinoma | [74] |

| miR-483-5p | Activation | miR-483-5p | Binding IGF2/H19 enhancer | Promote HCC malignant progression | Hepatocellular carcinoma | [75] |

| Disease Category | miR-483 Isoform | Validated Targets |

| Neoplasm | miR-483-3p | BBC3, PUMA, MMP9, CCNE1, PTEN, CDK4, CDK6, CDC25A, RB1, MDM4, DKK3, SMAD4, SMAD2, ITGB3, IGF1, BRCA1 |

| miR-483-5p | MAPK1, ERK2 | |

| Cardiopulmonary | miR-483-3p | AGT, ACE, ACE2, AGTR2, VEZF1 |

| miR-483-5p | MAPK1, MAPK3, ERK2, ERK1, ET-1, TGFB1, TGFBR2, SMAD2, ROCK1, TIMP2, PDGFB, TNFSF8, CTGF, PCSK9 | |

| Metabolic | miR-483-3p | IGF1, IGF1R |

| miR-483-5p | PDX1, MAFA, MAPK1, ERK2, TIMP2, HDAC4, ALDH1A3, PCSK9 | |

| Immune-mediated | miR-483-3p | CTGF, HIPK2, APLNR, CD81, RNF5, IGF1 |

| miR-483-5p | SRSF4, HDAC2, COL1A1, FLI1 | |

| Nervous System | miR-483-3p | XPO1 |

| miR-483-5p | ERK1, ERK2, GPX3, PGAP2 | |

| Musculoskeletal | miR-483-3p | DKK2, SMAD4, IGF1, IGF2, SRF |

| miR-483-5p | SATB2, RPL31, MATN3, DUSP5, IGF2, MAPK1, MAPK3, ERK2, ERK1, NOTCH3, SRF |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Xu, J.; Luxu, S.; Huang, H.-Y.; Lin, Y.-C.-D.; Huang, H.-D. Integrative Regulatory Networks of MicroRNA-483: Unveiling Its Systematic Role in Human Diseases and Clinical Implications. Biomolecules 2025, 15, 1707. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom15121707

Xu J, Luxu S, Huang H-Y, Lin Y-C-D, Huang H-D. Integrative Regulatory Networks of MicroRNA-483: Unveiling Its Systematic Role in Human Diseases and Clinical Implications. Biomolecules. 2025; 15(12):1707. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom15121707

Chicago/Turabian StyleXu, Jiatong, Shupeng Luxu, Hsi-Yuan Huang, Yang-Chi-Dung Lin, and Hsien-Da Huang. 2025. "Integrative Regulatory Networks of MicroRNA-483: Unveiling Its Systematic Role in Human Diseases and Clinical Implications" Biomolecules 15, no. 12: 1707. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom15121707

APA StyleXu, J., Luxu, S., Huang, H.-Y., Lin, Y.-C.-D., & Huang, H.-D. (2025). Integrative Regulatory Networks of MicroRNA-483: Unveiling Its Systematic Role in Human Diseases and Clinical Implications. Biomolecules, 15(12), 1707. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom15121707