Vitamin B12-Loaded Chitosan Nanoparticles Promote Skeletal Muscle Injury Repair in Aged Rats via Amelioration of Aging-Suppressed Efferocytosis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

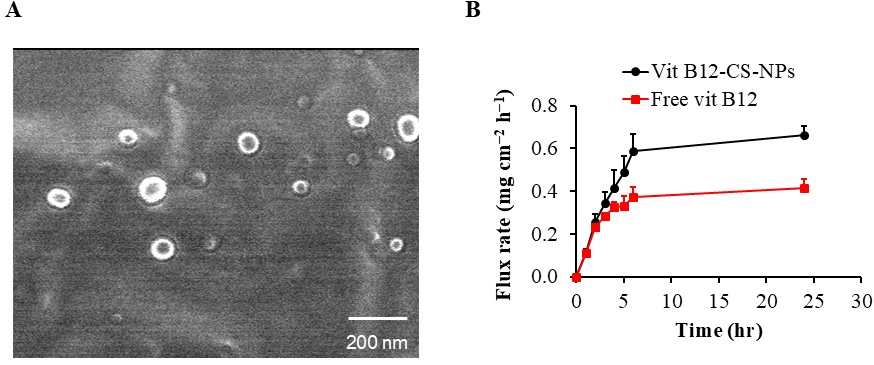

2.1. Preparation and Characterization of Vit B12-Loaded Chitosan Nanoparticles (B12 CS NPS)

2.2. Animals

2.3. Chemicals

2.4. Study Design

2.5. Biochemical Analysis

2.6. Quantitative Real-Time Polymerase Chain Reaction (qPCR) Analysis for mRNA Gene Expression of BAX, Bcl-2, MerTK, ADAM17, PPARγ, MiR-124, Pax7, MyoD and Myog

2.6.1. Total RNA Extraction

2.6.2. SYBR Green RT-qPCR

2.7. Histological Analysis

2.8. Immunohistochemical Analysis

2.9. Microscopic Analysis

2.10. Computer-Assisted Digital Image Analysis (Digital Morphometric Study)

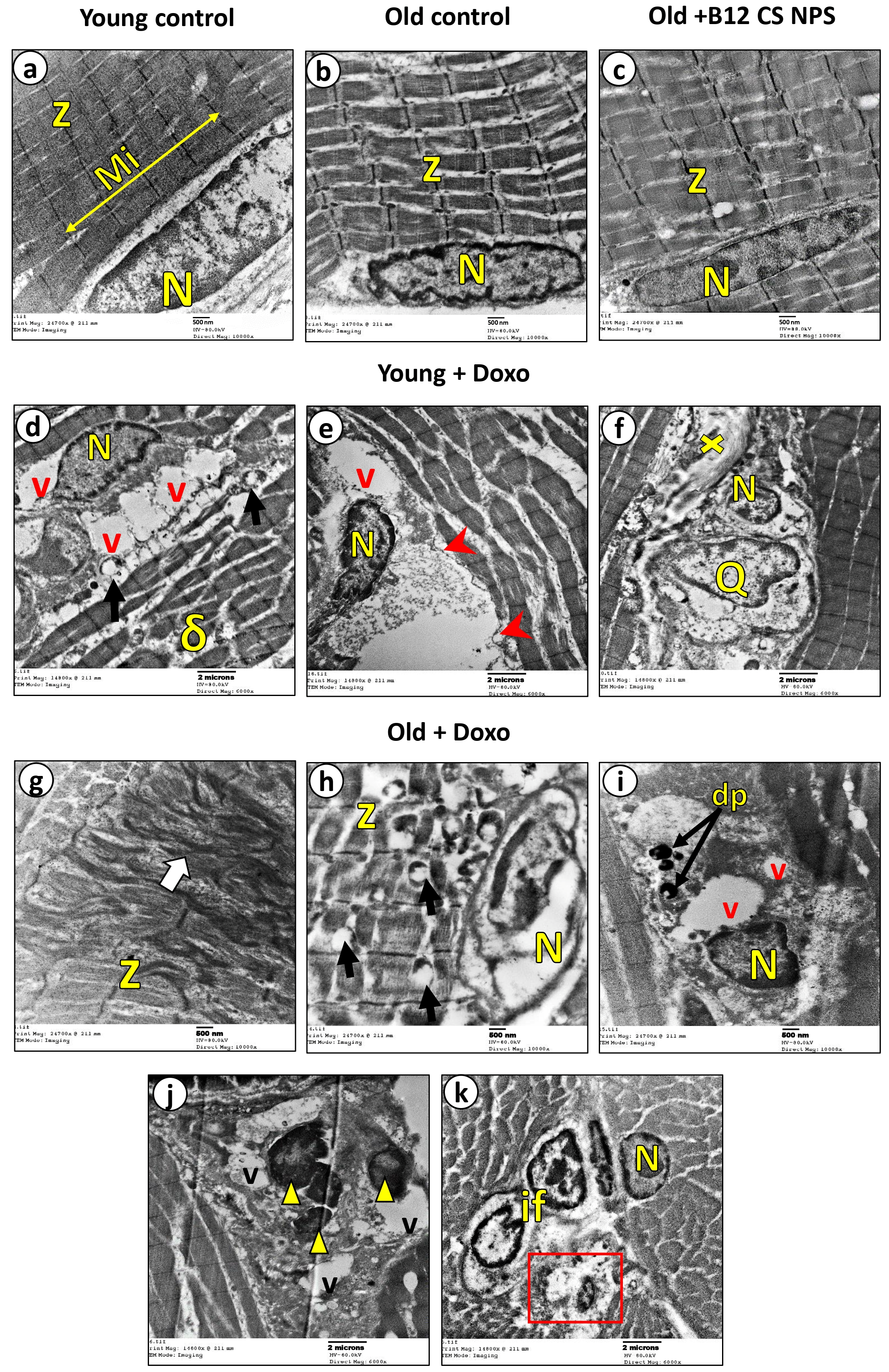

2.11. Transmission Electron Microscopic Examination

2.12. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Preparation and Characterization of B12 CS NPS

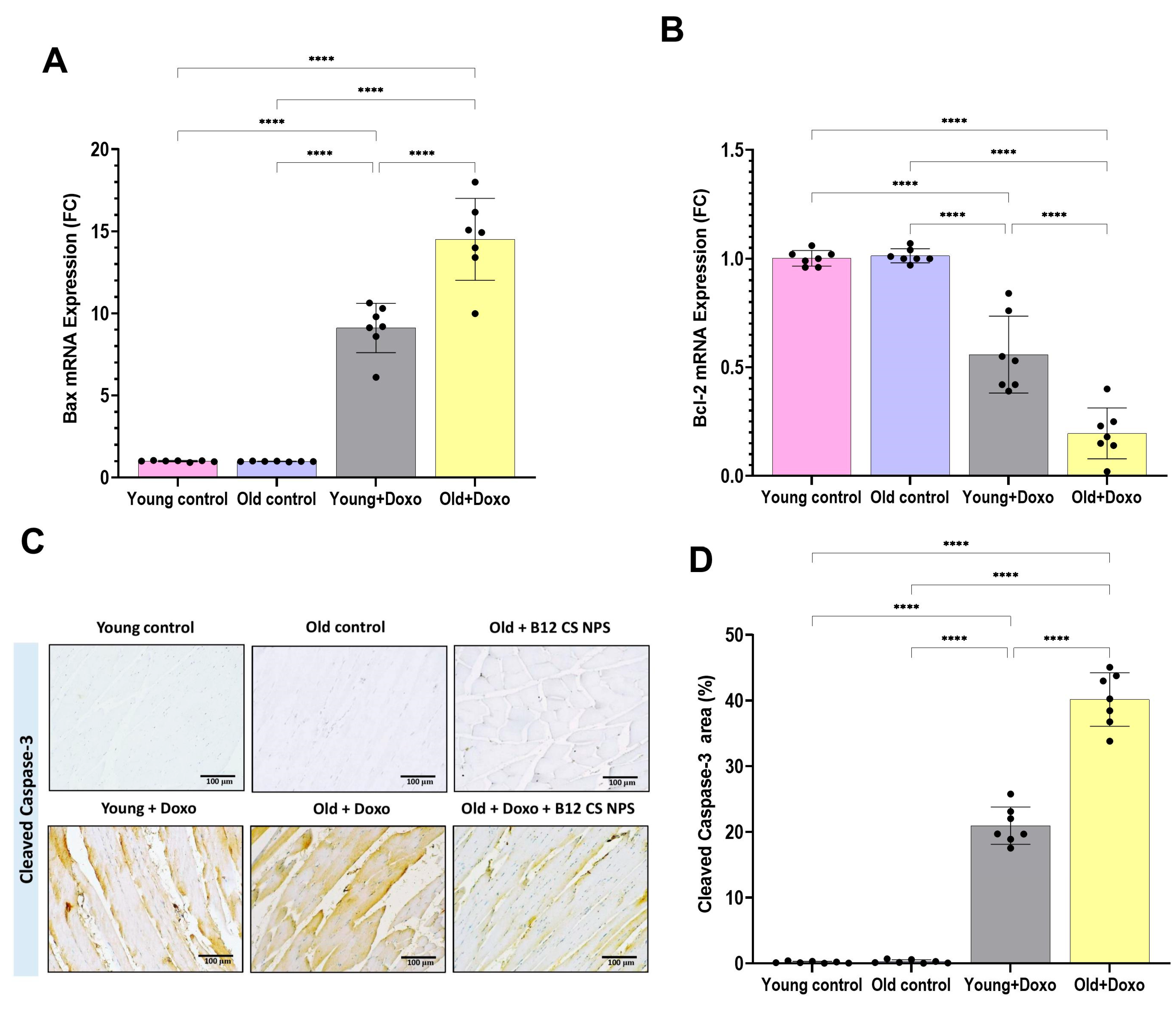

3.2. Aging Suppressed Efferocytosis of Apoptotic Skeletal Muscle Cells

3.3. Suppressed MerTK and Enhanced ADAM17 Expression Contributed to Age-Related Impaired Efferocytosis

3.4. PPARγ and MiR-124 Contribute to Age-Related Impaired Efferocytosis

3.5. Vit B12 Enhances Aging-Impaired Efferocytosis of Apoptotic Skeletal Muscle Cells

3.6. Vit B12 Promotes Aging-Impaired Efferocytosis via Enhancing MerTK Expression and Supressing ADAM17

3.7. PPARγ and MiR-124 Are Enhanced by Vit B12 Administration

3.8. Vit B12-Enhanced Macrophage Phenotypic Shift Toward CD163+ M2 Phenotype at Day 3 Post-Doxorubicin-Induced Acute Myotoxicity

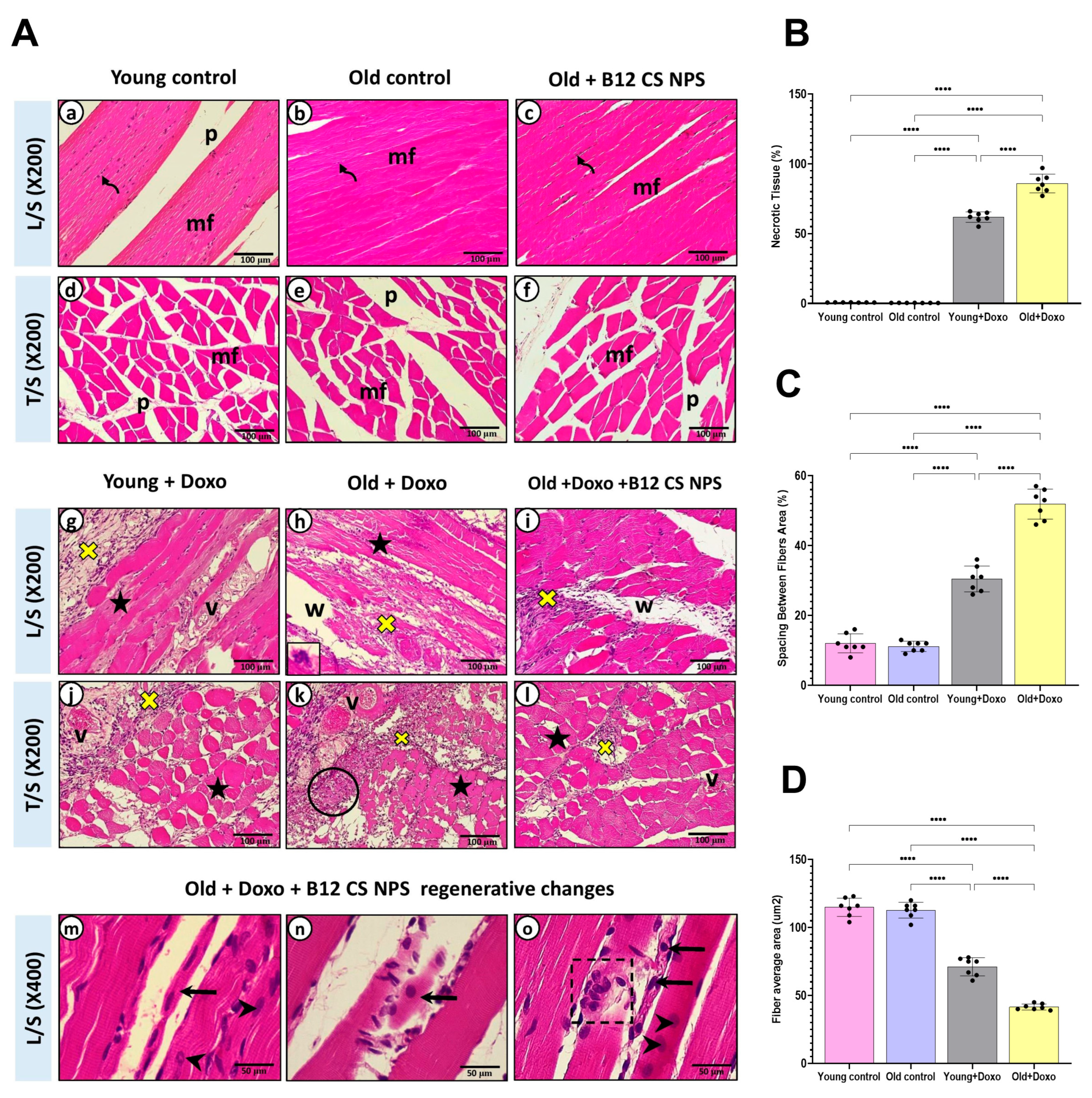

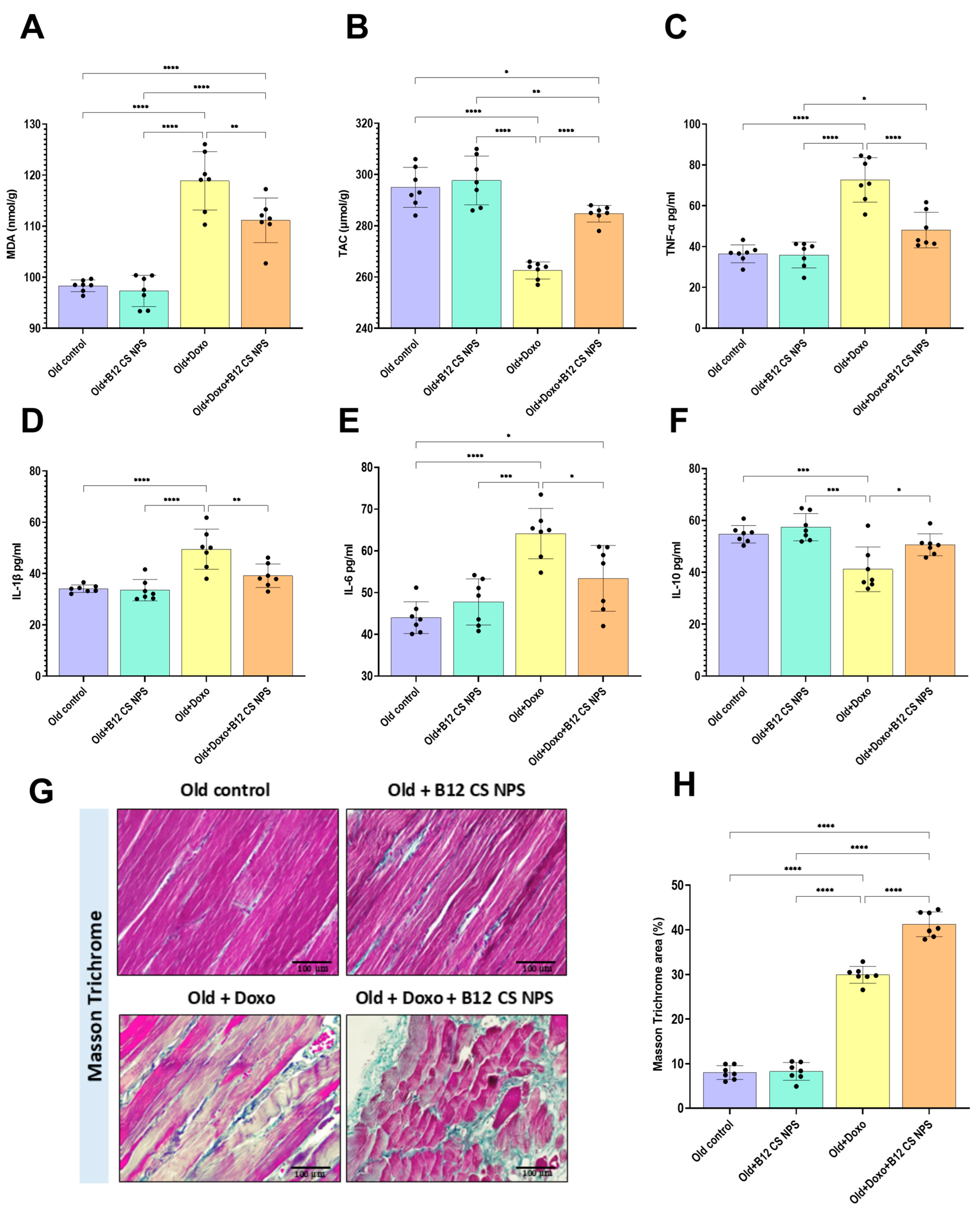

3.9. Vit B12 Reduced Oxidative Stress and Inflammation, Promoted Extracellular Matrix Deposition, and Improved Remodeling Post-Doxorubicin-Induced Acute Myotoxicity

3.10. Vit B12 Enhanced Satellite Cell Activation and Early Differentiation at Day 3 Post-Doxorubicin-Induced Acute Myotoxicity

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

References

- Ocampo, A.; Reddy, P.; Martinez-Redondo, P.; Platero-Luengo, A.; Hatanaka, F.; Hishida, T.; Li, M.; Lam, D.; Kurita, M.; Beyret, E.; et al. In Vivo Amelioration of Age-Associated Hallmarks by Partial Reprogramming. Cell 2016, 167, 1719–1733.e12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz-Cánoves, P.; Neves, J.; Sousa-Victor, P. Understanding muscle regenerative decline with aging: New approaches to bring back youthfulness to aged stem cells. FEBS J. 2020, 287, 406–416. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Tidball, J.G.; Flores, I.; Welc, S.S.; Wehling-Henricks, M.; Ochi, E. Aging of the immune system and impaired muscle regeneration: A failure of immunomodulation of adult myogenesis. Exp. Gerontol. 2021, 145, 111200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perandini, L.A.; Chimin, P.; Lutkemeyer, D.D.S.; Câmara, N.O.S. Chronic inflammation in skeletal muscle impairs satellite cells function during regeneration: Can physical exercise restore the satellite cell niche? FEBS J. 2018, 285, 1973–1984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juban, G.; Chazaud, B. Efferocytosis during Skeletal Muscle Regeneration. Cells 2021, 10, 3267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poon, I.K.H.; Ravichandran, K.S. Targeting Efferocytosis in Inflammaging. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2024, 64, 339–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doran, A.C.; Yurdagul, A.; Tabas, I. Efferocytosis in health and disease. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2020, 20, 254–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Zaeed, N.; Budai, Z.; Szondy, Z.; Sarang, Z. TAM kinase signaling is indispensable for proper skeletal muscle regeneration in mice. Cell Death Dis. 2021, 12, 611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lahey, K.C.; Varsanyi, C.; Wang, Z.; Aquib, A.; Gadiyar, V.; Rodrigues, A.A.; Pulica, R.; Desind, S.; Davra, V.; Calianese, D.C.; et al. Regulation of Mertk Surface Expression via ADAM17 and γ-Secretase Proteolytic Processing. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 4404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Shi, R.; Luo, B.; Yang, X.; Qiu, L.; Xiong, J.; Jiang, M.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Wu, Y. Macrophage peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ deficiency delays skin wound healing through impairing apoptotic cell clearance in mice. Cell Death Dis. 2015, 6, e1597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, Z.; Chen, J.; Yang, H.; Hu, X.; Yang, F. PIAS1 alleviates diabetic peripheral neuropathy through SUMOlation of PPAR-γ and miR-124-induced downregulation of EZH2/STAT3. Cell Death Discov. 2021, 7, 372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Shi, L.; Xin, W.; Xu, J.; Xu, J.; Li, Q.; Xu, Z.; Wang, J.; Wang, G.; Yao, W.; et al. Activation of PPARγ inhibits pro-inflammatory cytokines production by upregulation of miR-124 in vitro and in vivo. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2017, 486, 726–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calligaris, M.; Cuffaro, D.; Bonelli, S.; Spanò, D.P.; Rossello, A.; Nuti, E.; Scilabra, S.D. Strategies to Target ADAM17 in Disease: From Its Discovery to the iRhom Revolution. Molecules 2021, 26, 944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, Z.; Wang, P.-Y.; Su, D.-F.; Liu, X. miRNA-124 in Immune System and Immune Disorders. Front. Immunol. 2016, 7, 406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Artimovič, P.; Špaková, I.; Macejková, E.; Pribulová, T.; Rabajdová, M.; Mareková, M.; Zavacká, M. The ability of microRNAs to regulate the immune response in ischemia/reperfusion inflammatory pathways. Genes Immun. 2024, 25, 277–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovatcheva, M.; Melendez, E.; Chondronasiou, D.; Pietrocola, F.; Bernad, R.; Caballe, A.; Junza, A.; Capellades, J.; Holguín-Horcajo, A.; Prats, N.; et al. Vitamin B12 is a limiting factor for induced cellular plasticity and tissue repair. Nat. Metab. 2023, 5, 1911–1930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamura, J.; Kubota, K.; Murakami, H.; Sawamura, M.; Matsushima, T.; Tamura, T.; Saitoh, T.; Kurabayshi, H.; Naruse, T. Immunomodulation by vitamin B12: Augmentation of CD8+ T lymphocytes and natural killer (NK) cell activity in vitamin B12-deficient patients by methyl-B12 treatment. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 2001, 116, 28–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ge, Y.; Yang, C.; Zadeh, M.; Sprague, S.M.; Lin, Y.D.; Jain, H.S.; Determann, B.F.; Roth, W.H.; Palavicini, J.P.; Larochelle, J.; et al. Functional regulation of microglia by vitamin B12 alleviates ischemic stroke-induced neuroinflammation in mice. iScience 2024, 27, 109480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Min, K.; Kwon, O.S.; Smuder, A.J.; Wiggs, M.P.; Sollanek, K.J.; Christou, D.D.; Yoo, J.K.; Hwang, M.H.; Szeto, H.H.; Kavazis, A.N.; et al. Increased mitochondrial emission of reactive oxygen species and calpain activation are required for doxorubicin-induced cardiac and skeletal muscle myopathy. J. Physiol. 2015, 593, 2017–2036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, A.P.; Pei, X.M.; Sin, T.K.; Yip, S.P.; Yung, B.Y.; Chan, L.W.; Wong, C.S.; Siu, P.M. Acylated and unacylated ghrelin inhibit doxorubicin-induced apoptosis in skeletal muscle. Acta Physiol. 2014, 211, 201–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hiensch, A.E.; Bolam, K.A.; Mijwel, S.; Jeneson, J.A.L.; Huitema, A.D.R.; Kranenburg, O.; van der Wall, E.; Rundqvist, H.; Wengstrom, Y.; May, A.M. Doxorubicin-induced skeletal muscle atrophy: Elucidating the underlying molecular pathways. Acta Physiol. 2020, 229, e13400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sin, T.K.; Tam, B.T.; Yu, A.P.; Yip, S.P.; Yung, B.Y.; Chan, L.W.; Wong, C.S.; Rudd, J.A.; Siu, P.M. Acute Treatment of Resveratrol Alleviates Doxorubicin-Induced Myotoxicity in Aged Skeletal Muscle Through SIRT1-Dependent Mechanisms. J. Gerontol. Ser. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 2016, 71, 730–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guler, E.; Yekeler, H.B.; Parviz, G.; Aydin, S.; Asghar, A.; Dogan, M.; Ikram, F.; Kalaskar, D.M.; Cam, M.E. Vitamin B12-loaded chitosan-based nanoparticle-embedded polymeric nanofibers for sublingual and transdermal applications: Two alternative application routes for vitamin B12. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 258, 128635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abd El-Emam, M.M.; Behairy, A.; Mostafa, M.; Khamis, T.; Osman, N.M.S.; Alsemeh, A.E.; Mansour, M.F. Chrysin-loaded PEGylated liposomes protect against alloxan-induced diabetic neuropathy in rats: The interplay between endoplasmic reticulum stress and autophagy. Biol. Res. 2024, 57, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reeves, P.G.; Nielsen, F.H.; Fahey, G.C. AIN-93 purified diets for laboratory rodents: Final report of the American Institute of Nutrition ad hoc writing committee on the reformulation of the AIN-76A rodent diet. J. Nutr. 1993, 123, 1939–1951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Research Council. Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals, 8th ed.; The National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Smuder, A.J.; Kavazis, A.N.; Min, K.; Powers, S.K. Exercise protects against doxorubicin-induced oxidative stress and proteolysis in skeletal muscle. J. Appl. Physiol. 2011, 110, 935–942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huo, M.; Tang, Z.; Wang, L.; Zhang, L.; Guo, H.; Chen, Y.; Gu, P.; Shi, J. Magnesium hexacyanoferrate nanocatalysts attenuate chemodrug-induced cardiotoxicity through an anti-apoptosis mechanism driven by modulation of ferrous iron. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 7778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Zhao, Y.; Liu, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Yan, Y.; Li, S.; Li, S.; Tong, H. Cyanocobalamin promotes muscle development through the TGF-β signaling pathway. Food Funct. 2022, 13, 12721–12732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Livak, K.J.; Schmittgen, T.D. Analysis of Relative Gene Expression Data Using Real-Time Quantitative PCR and the 2−ΔΔCT Method. Methods 2001, 25, 402–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bancroft, J.D.; Layton, C. The hematoxylin and eosin stain. In Bancroft’s Theory and Practice of Histological Techniques; Churchill Livingstone: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Mondal, S.K. Manual of Histological Techniques, 2nd ed.; Jaypee Brothers Medical Publishers: New Delhi, India, 2017; pp. 107–122. [Google Scholar]

- Glauert, A.M.; Lewis, P.R. Embedding methods. In Biological Specimen Preparation for Transmission Electron Microscopy; Portland Press Ltd.: London, UK; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 1998; pp. 147–169. [Google Scholar]

- Nelke, C.; Dziewas, R.; Minnerup, J.; Meuth, S.G.; Ruck, T. Skeletal muscle as potential central link between sarcopenia and immune senescence. eBioMedicine 2019, 49, 381–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Maeyer, R.P.H.; van de Merwe, R.C.; Louie, R.; Bracken, O.V.; Devine, O.P.; Goldstein, D.R.; Uddin, M.; Akbar, A.N.; Gilroy, D.W. Blocking elevated p38 MAPK restores efferocytosis and inflammatory resolution in the elderly. Nat. Immunol. 2020, 21, 615–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, H.; Cheng, X.; Li, F.; Guan, Z.; Xu, J.; Wu, D.; Gao, Y.; Zhan, X.; Wang, P.; Zhou, H.; et al. Defective efferocytosis by aged macrophages promotes STING signaling mediated inflammatory liver injury. Cell Death Discov. 2023, 9, 236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DeBerge, M.; Yeap, X.Y.; Dehn, S.; Zhang, S.; Grigoryeva, L.; Misener, S.; Procissi, D.; Zhou, X.; Lee, D.C.; Muller, W.A.; et al. MerTK Cleavage on Resident Cardiac Macrophages Compromises Repair After Myocardial Ischemia Reperfusion Injury. Circ. Res. 2017, 121, 930–940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rymut, N.; Heinz, J.; Sadhu, S.; Hosseini, Z.; Riley, C.O.; Marinello, M.; Maloney, J.; MacNamara, K.C.; Spite, M.; Fredman, G. Resolvin D1 promotes efferocytosis in aging by limiting senescent cell-induced MerTK cleavage. FASEB J. 2020, 34, 597–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thorp, E.; Vaisar, T.; Subramanian, M.; Mautner, L.; Blobel, C.; Tabas, I. Shedding of the Mer Tyrosine Kinase Receptor Is Mediated by ADAM17 Protein through a Pathway Involving Reactive Oxygen Species, Protein Kinase Cδ, and p38 Mitogen-activated Protein Kinase (MAPK). J. Biol. Chem. 2011, 286, 33335–33344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sather, S.; Kenyon, K.D.; Lefkowitz, J.B.; Liang, X.; Varnum, B.C.; Henson, P.M.; Graham, D.K. A soluble form of the Mer receptor tyrosine kinase inhibits macrophage clearance of apoptotic cells and platelet aggregation. Blood 2007, 109, 1026–1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rőszer, T.; Menéndez-Gutiérrez, M.P.; Lefterova, M.I.; Alameda, D.; Núñez, V.; Lazar, M.A.; Fischer, T.; Ricote, M. Autoimmune Kidney Disease and Impaired Engulfment of Apoptotic Cells in Mice with Macrophage Peroxisome Proliferator-Activated Receptor γ or Retinoid X Receptor α Deficiency. J. Immunol. 2011, 186, 621–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, B.; Gan, W.; Liu, Z.; Shen, Z.; Wang, J.; Shi, R.; Liu, Y.; Liu, Y.; Jiang, M.; Zhang, Z.; et al. Erythropoeitin Signaling in Macrophages Promotes Dying Cell Clearance and Immune Tolerance. Immunity 2016, 44, 287–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Gazzar, W.; Allam, M.; Shaltout, S.; Mohammed, L.; Sadek, A.; Nasr, H. Pioglitazone modulates immune activation and ameliorates inflammation induced by injured renal tubular epithelial cells via PPARγ/miRNA-124/STAT3 signaling. Biomed. Rep. 2022, 18, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Li, Q.; Gui, H.; Xu, D.-P.; Yang, Y.-L.; Su, D.-F.; Liu, X. MicroRNA-124 mediates the cholinergic anti-inflammatory action through inhibiting the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines. Cell Res. 2013, 23, 1270–1283. [Google Scholar]

- Simonenko, S.Y.; Bogdanova, D.A.; Kuldyushev, N.A. Emerging Roles of Vitamin B12 in Aging and Inflammation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 5044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erkurt, M.A.; Aydogdu, I.; Dikilitaş, M.; Kuku, I.; Kaya, E.; Bayraktar, N.; Ozhan, O.; Ozkan, I.; Sönmez, A. Effects of Cyanocobalamin on Immunity in Patients with Pernicious Anemia. Med. Princ. Pract. 2008, 17, 131–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ge, Y.; Zadeh, M.; Sharma, C.; Lin, Y.-D.; Soshnev, A.A.; Mohamadzadeh, M. Controlling functional homeostasis of ileal resident macrophages by vitamin B12 during steady state and Salmonella infection in mice. Mucosal Immunol. 2024, 17, 1314–1325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colapicchioni, V.; Millozzi, F.; Parolini, O.; Palacios, D. Nanomedicine, a valuable tool for skeletal muscle disorders: Challenges, promises, and limitations. WIREs Nanomed. Nanobiotechnol. 2022, 14, e1777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hicks, M.R.; Liu, X.; Young, C.S.; Saleh, K.; Ji, Y.; Jiang, J.; Emami, M.R.; Mokhonova, E.; Spencer, M.J.; Meng, H.; et al. Nanoparticles systemically biodistribute to regenerating skeletal muscle in DMD. J. Nanobiotechnol. 2023, 21, 303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oakley, R. Vascular Hyperpermeability and Aging. Aging Dis. 2014, 5, 114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ge, Y.; Zadeh, M.; Mohamadzadeh, M. Vitamin B12 Regulates the Transcriptional, Metabolic, and Epigenetic Programing in Human Ileal Epithelial Cells. Nutrients 2022, 14, 2825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmad, S.; Kumar, K.A.; Basak, T.; Bhardwaj, G.; Yadav, D.K.; Lalitha, A.; Chandak, G.R.; Raghunath, M.; Sengupta, S. PPAR signaling pathway is a key modulator of liver proteome in pups born to vitamin B12 deficient rats. J. Proteom. 2013, 91, 297–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meher, A.; Joshi, A.; Joshi, S. Differential Regulation of Hepatic Transcription Factors in the Wistar Rat Offspring Born to Dams Fed Folic Acid, Vitamin B12 Deficient Diets and Supplemented with Omega-3 Fatty Acids. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e90209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, L.; Jia, J.; Chen, Y.; Liu, R.; Cao, R.; Duan, M.; Zhang, M.; Xu, Y. Pentoxifylline alleviates ischemic white matter injury through up-regulating Mertk-mediated myelin clearance. J. Neuroinflamm. 2022, 19, 128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, J.; Peng, Y.; Gu, C.; Chen, H.; Lin, Z.; Zhou, H.; Wu, X.; Li, J.; Yu, X.; Cao, Y.; et al. Wogonin Accelerates Hematoma Clearance and Improves Neurological Outcome via the PPAR-γ Pathway After Intracerebral Hemorrhage. Transl. Stroke Res. 2021, 12, 660–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhou, D.; Zhang, L.S.; Deng, F.X.; Shu, S.; Wang, L.J.; Wu, Y.; Guo, N.; Zhou, J.; et al. Angiotensin II deteriorates advanced atherosclerosis by promoting MerTK cleavage and impairing efferocytosis through the AT 1 R/ROS/p38 MAPK/ADAM17 pathway. Am. J. Physiol.-Cell Physiol. 2019, 317, C776–C787. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.; Li, X.; Lu, R.; Lv, Y.; Wu, Y.; Ye, J.; Zhao, J.; Li, L.; Huang, Q.; Meng, W.; et al. Vitamin B 12 protects necrosis of acinar cells in pancreatic tissues with acute pancreatitis. MedComm 2024, 5, e686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sciorati, C.; Rigamonti, E.; Manfredi, A.A.; Rovere-Querini, P. Cell death, clearance and immunity in the skeletal muscle. Cell Death Differ. 2016, 23, 927–937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noelia, A.; Bensinger, S.J.; Hong, C.; Beceiro, S.; Bradley, M.N.; Zelcer, N.; Deniz, J.; Ramirez, C.; Díaz, M.; Gallardo, G.; et al. Apoptotic Cells Promote Their Own Clearance and Immune Tolerance through Activation of the Nuclear Receptor LXR. Immunity 2009, 31, 245–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ariel, A.; Serhan, C.N. New Lives Given by Cell Death: Macrophage Differentiation Following Their Encounter with Apoptotic Leukocytes during the Resolution of Inflammation. Front. Immunol. 2012, 3, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukundan, L.; Odegaard, J.I.; Morel, C.R.; Heredia, J.E.; Mwangi, J.W.; Ricardo-Gonzalez, R.R.; Goh, Y.S.; Eagle, A.R.; Dunn, S.E.; Awakuni, J.U.; et al. PPAR-δ senses and orchestrates clearance of apoptotic cells to promote tolerance. Nat. Med. 2009, 15, 1266–1272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mehrotra, P.; Ravichandran, K.S. Drugging the efferocytosis process: Concepts and opportunities. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2022, 21, 601–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tibrewal, N.; Wu, Y.; D’mello, V.; Akakura, R.; George, T.C.; Varnum, B.; Birge, R.B. Autophosphorylation Docking Site Tyr-867 in Mer Receptor Tyrosine Kinase Allows for Dissociation of Multiple Signaling Pathways for Phagocytosis of Apoptotic Cells and Down-modulation of Lipopolysaccharide-inducible NF-κB Transcriptional Activation. J. Biol. Chem. 2008, 283, 3618–3627. [Google Scholar]

- Filardy, A.A.; Pires, D.R.; Nunes, M.P.; Takiya, C.M.; Freire-de-Lima, C.G.; Ribeiro-Gomes, F.L.; DosReis, G.A. Proinflammatory Clearance of Apoptotic Neutrophils Induces an IL-12lowIL-10high Regulatory Phenotype in Macrophages. J. Immunol. 2010, 185, 2044–2050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zizzo, G.; Hilliard, B.A.; Monestier, M.; Cohen, P.L. Efficient Clearance of Early Apoptotic Cells by Human Macrophages Requires M2c Polarization and MerTK Induction. J. Immunol. 2012, 189, 3508–3520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Zhou, L. The Many Roles of Macrophages in Skeletal Muscle Injury and Repair. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2022, 10, 952249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Careccia, G.; Mangiavini, L.; Cirillo, F. Regulation of Satellite Cells Functions during Skeletal Muscle Regeneration: A Critical Step in Physiological and Pathological Conditions. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 25, 512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nawaz, A.; Bilal, M.; Fujisaka, S.; Kado, T.; Aslam, M.R.; Ahmed, S.; Okabe, K.; Igarashi, Y.; Watanabe, Y.; Kuwano, T.; et al. Depletion of CD206+ M2-like macrophages induces fibro-adipogenic progenitors activation and muscle regeneration. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 7058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Gene Name | Primer Sequences (5′→3′) (F: Forward; R: Reverse) | Accession Number |

|---|---|---|

| Bax | F: TGGCCTCCTTTCCTACTTCG R: AAAATGCCTTTCCCCGTTCC | NM_017059.2 |

| Bcl-2 | F: AACTCTTCAGGGATGGGGTG R: GCTGGGGCCATATAGTTCCA | NM_016993.2 |

| MerTK | F: AGGGTTTGATGGCTACTCCC R: ACCAGCCAATCTCATTCCGA | NM_022943.1 |

| ADAM17 | F: CTGTGCCTTGTCTCTCCTGA R: TACATACACCCACACACCCC | NM_020306.3 |

| miR-124 | F: TCAAGATCAGAGACTCTGCTC R: TTCAAGTGCAGCCGTAGG | NR_031867.1 |

| PPARγ | F: GGATTCATGACCAGGGAGTTCCTC R: GCGGTCTCCACTGAGAATAATGAC | NM_013124.3 |

| Myog | F: GAGCCCCACTTCTATGACGG R: GTTGAGCAGGGTGCTTCTCT | NM_017115.3 |

| PAX7 | F: AGCCGAGTGCTCAGAATCAA R: TCCTCTCGAAAGCCTTCTCC | NM_001191984.2 |

| MyoD | F: GACGGCTCTCTCTGCTCCTT R: GTCTGAGTCGCCGCTGTAGT | NM_176079.2 |

| B-actin | F: AACCTTCTTGCAGCTCCTCC R: CCATACCCACCATCACACCC | NM_031144.3 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

El Gazzar, W.B.; Farag, A.A.; Bayoumi, H.; Radwaan, S.E.; Mohammed, L.A.; Nasr, H.E.; Ahmed, N.E.; Ibrahim, R.M.; Mostafa, M.; Mohamed, S.K.; et al. Vitamin B12-Loaded Chitosan Nanoparticles Promote Skeletal Muscle Injury Repair in Aged Rats via Amelioration of Aging-Suppressed Efferocytosis. Biomolecules 2025, 15, 1709. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom15121709

El Gazzar WB, Farag AA, Bayoumi H, Radwaan SE, Mohammed LA, Nasr HE, Ahmed NE, Ibrahim RM, Mostafa M, Mohamed SK, et al. Vitamin B12-Loaded Chitosan Nanoparticles Promote Skeletal Muscle Injury Repair in Aged Rats via Amelioration of Aging-Suppressed Efferocytosis. Biomolecules. 2025; 15(12):1709. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom15121709

Chicago/Turabian StyleEl Gazzar, Walaa Bayoumie, Amina A. Farag, Heba Bayoumi, Shaimaa E. Radwaan, Lina Abdelhady Mohammed, Hend Elsayed Nasr, Nashwa E. Ahmed, Reham M. Ibrahim, Mahmoud Mostafa, Shimaa K. Mohamed, and et al. 2025. "Vitamin B12-Loaded Chitosan Nanoparticles Promote Skeletal Muscle Injury Repair in Aged Rats via Amelioration of Aging-Suppressed Efferocytosis" Biomolecules 15, no. 12: 1709. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom15121709

APA StyleEl Gazzar, W. B., Farag, A. A., Bayoumi, H., Radwaan, S. E., Mohammed, L. A., Nasr, H. E., Ahmed, N. E., Ibrahim, R. M., Mostafa, M., Mohamed, S. K., Abdelhady, D., Elwakeel, E. E., Badr, A. M., & Soliman, S. (2025). Vitamin B12-Loaded Chitosan Nanoparticles Promote Skeletal Muscle Injury Repair in Aged Rats via Amelioration of Aging-Suppressed Efferocytosis. Biomolecules, 15(12), 1709. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom15121709