Plant-Assisted Synthesis, Phytochemical Profiling, and Bioactivity Evaluation of Copper Nanoparticles Derived from Tordylium trachycarpum (Apiaceae)

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials and Instrumentations

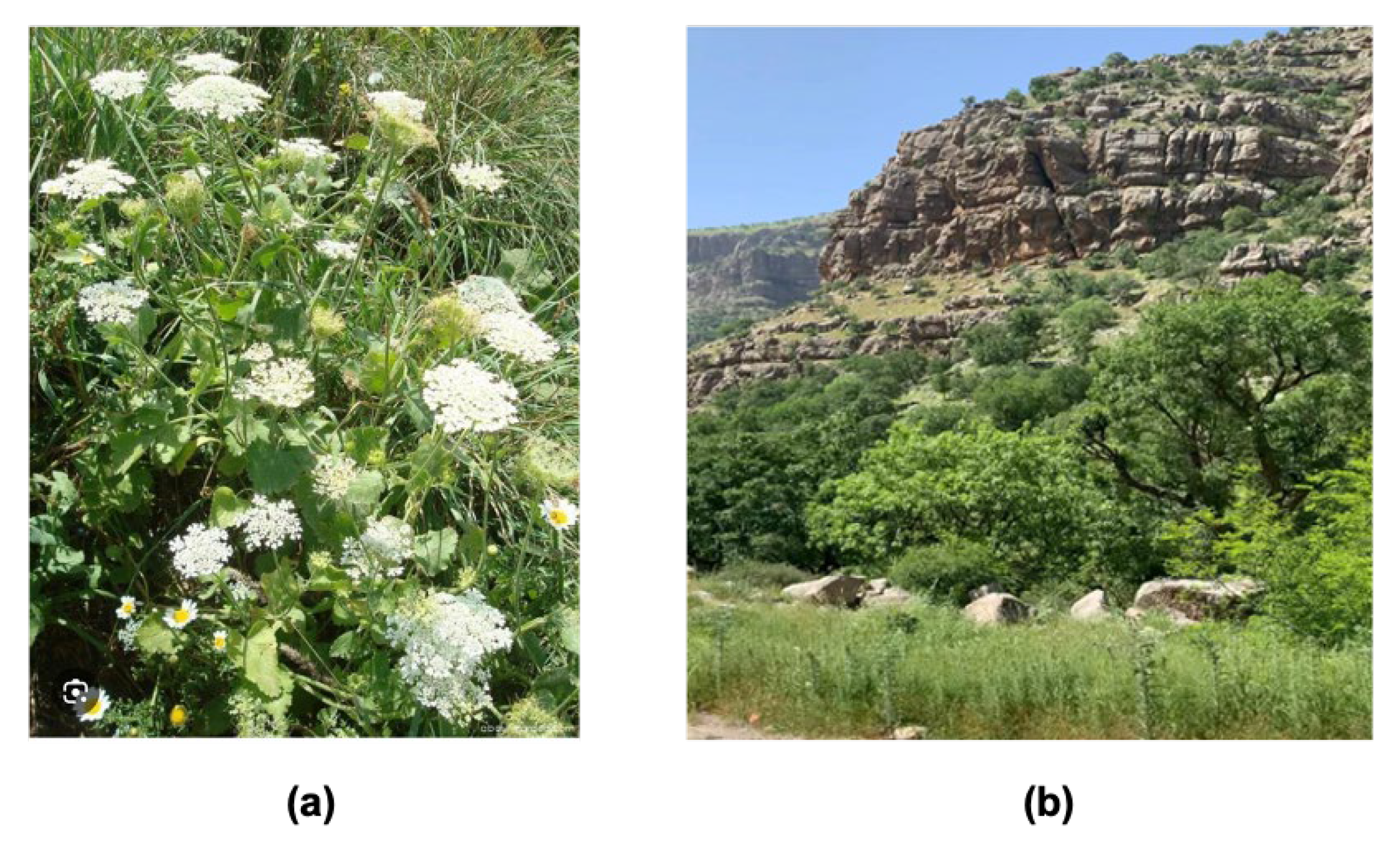

2.2. Plant Collection

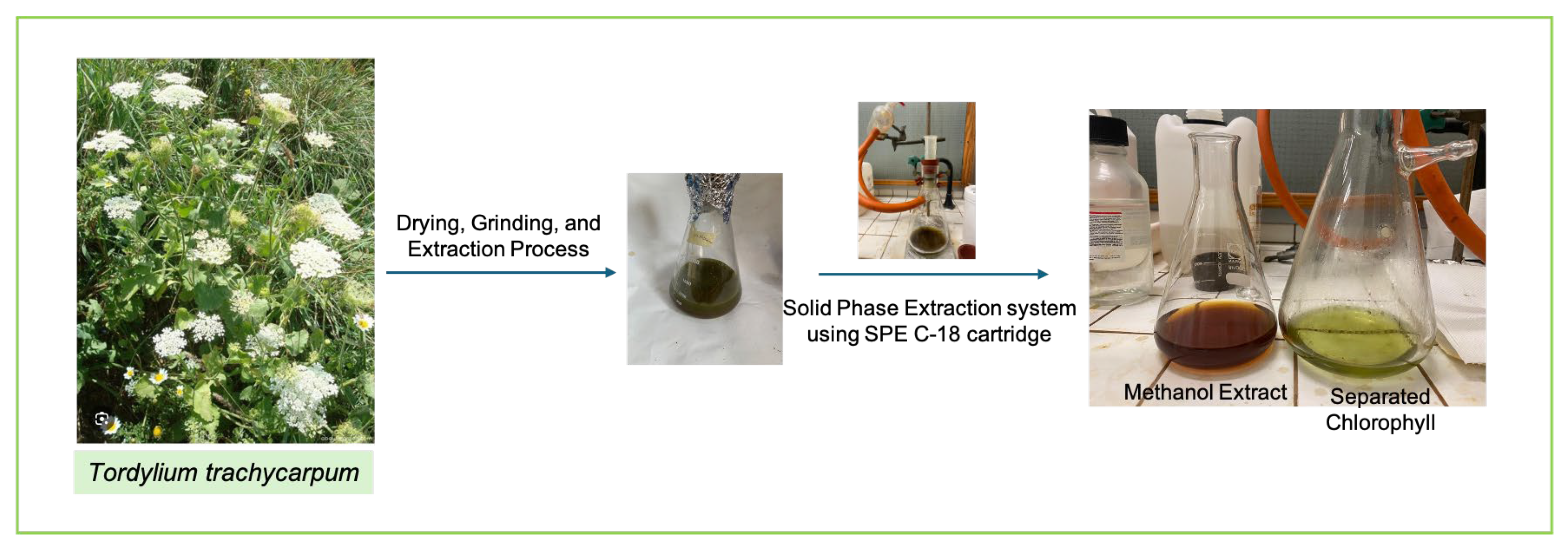

2.3. Extraction Process and Preliminary Chromatographic Purification of the Methanolic Extract

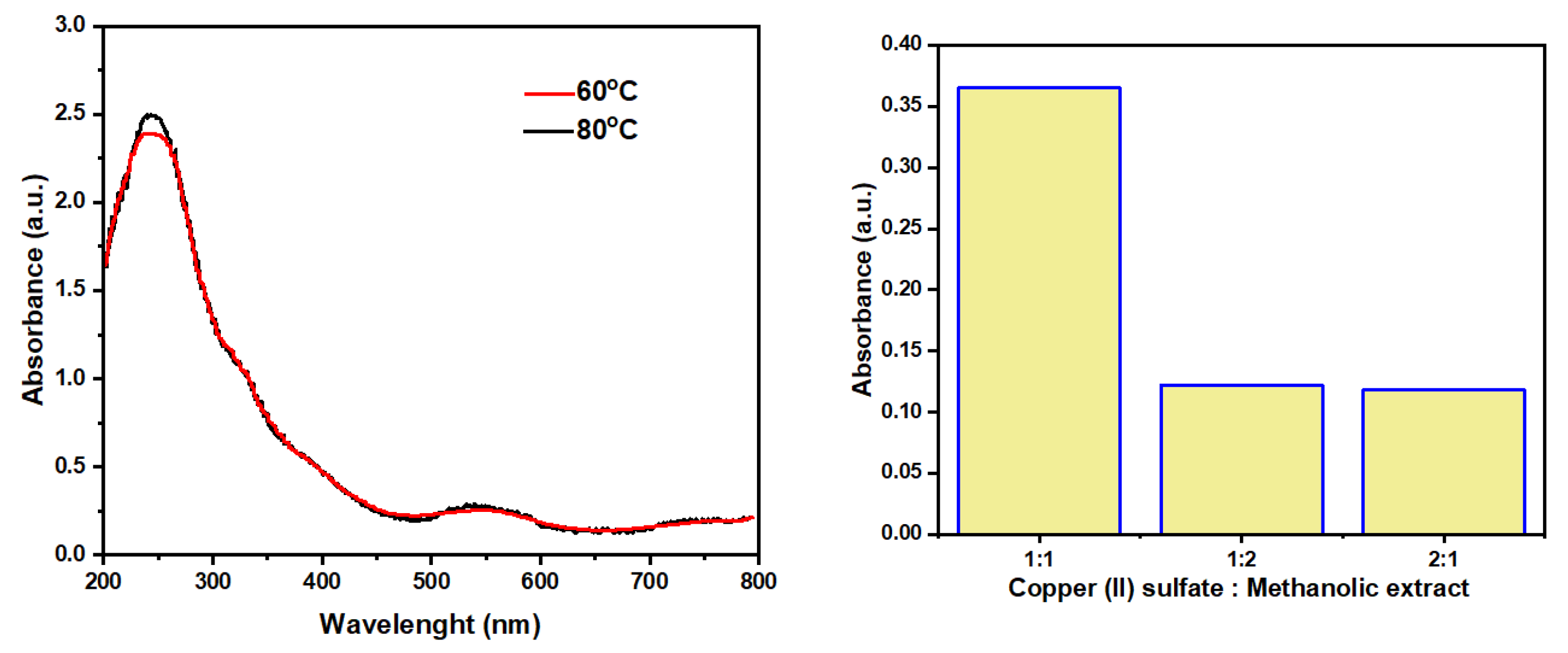

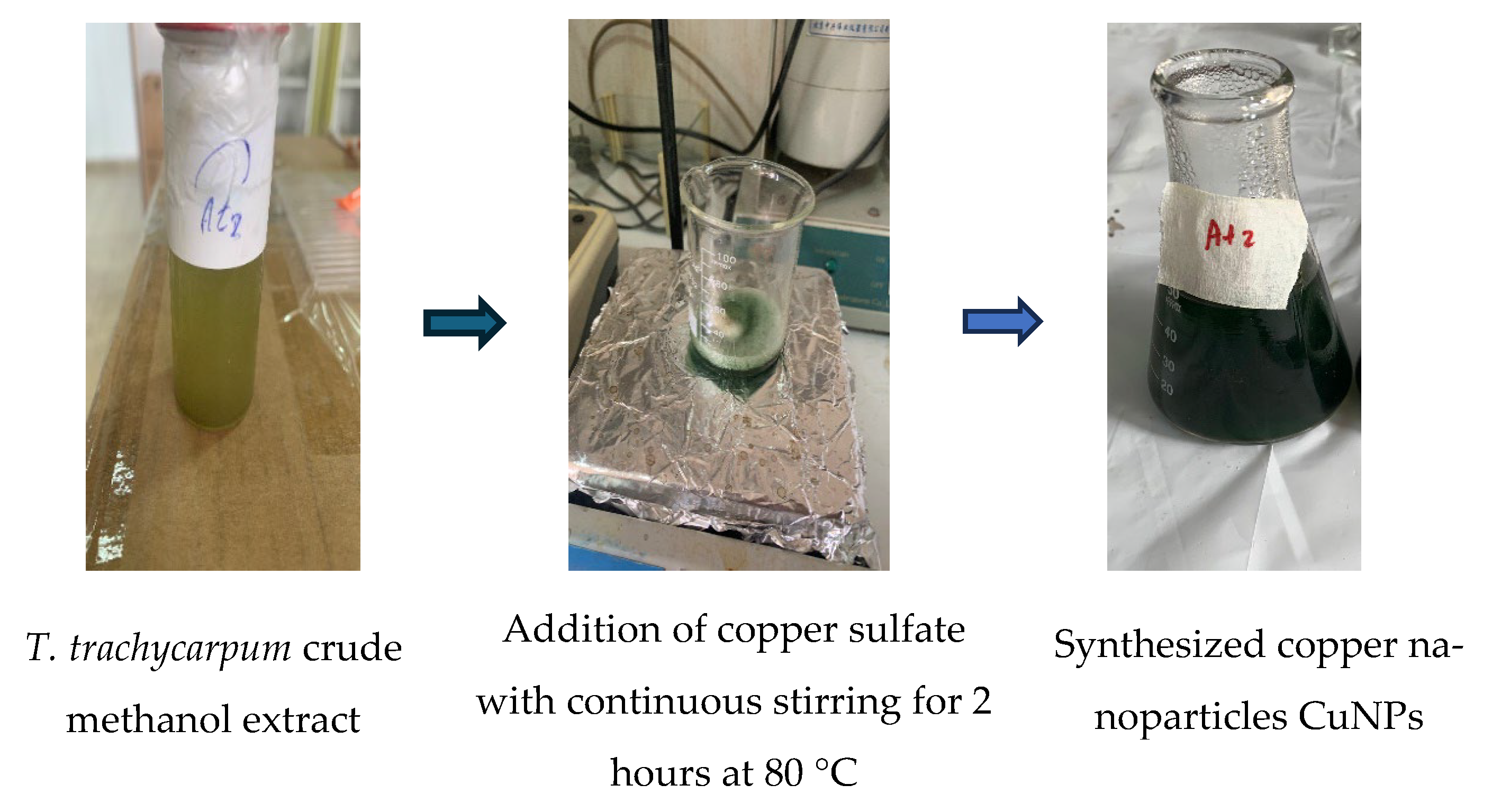

2.4. Synthesis of Copper Nanoparticles

2.5. Antimicrobial Assay

2.6. Minimum Inhibitory Concentration (MIC)

2.7. Antioxidant Assay

2.8. Total Phenolic and Flavonoid Contents Assay

2.9. Enzyme-Inhibitory Assay

2.10. Gas Chromatography–Mass Spectrometry (GC–MS) Analysis

2.11. Phytochemical Profiling of the Post-Synthesis Supernatant

2.12. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

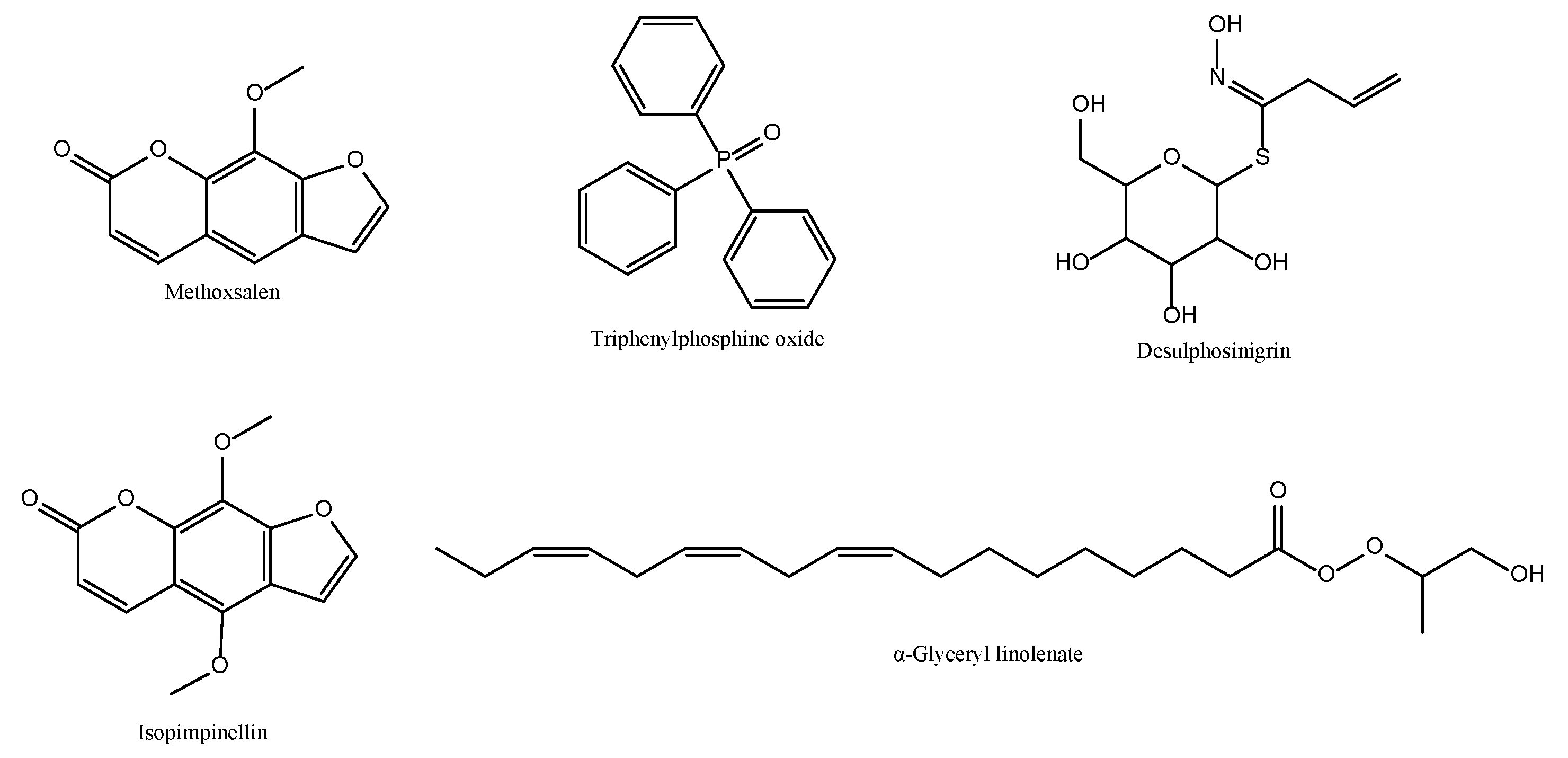

3.1. Phytochemical Analysis

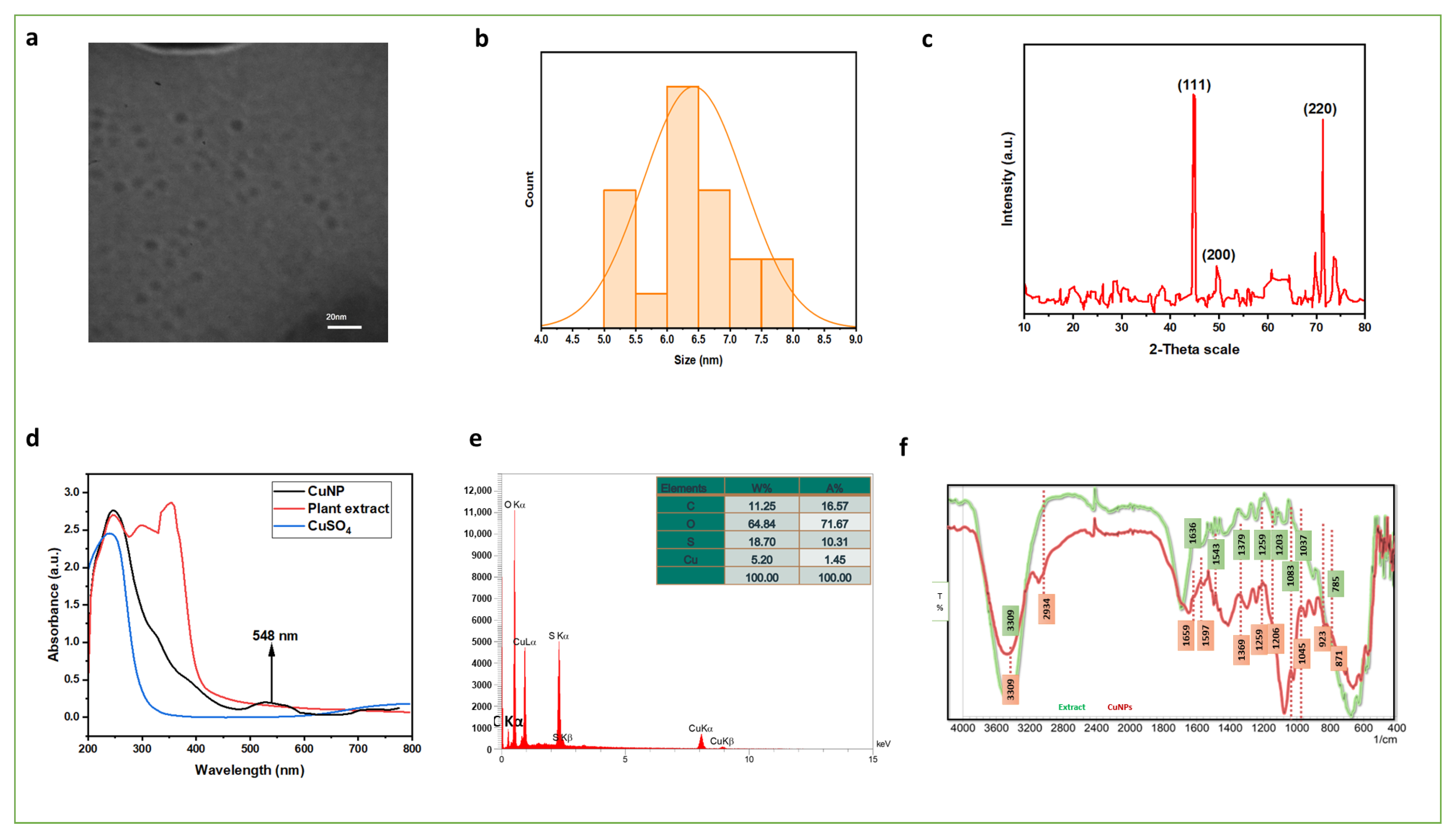

3.2. Characterization of Synthesized Copper Nanoparticles

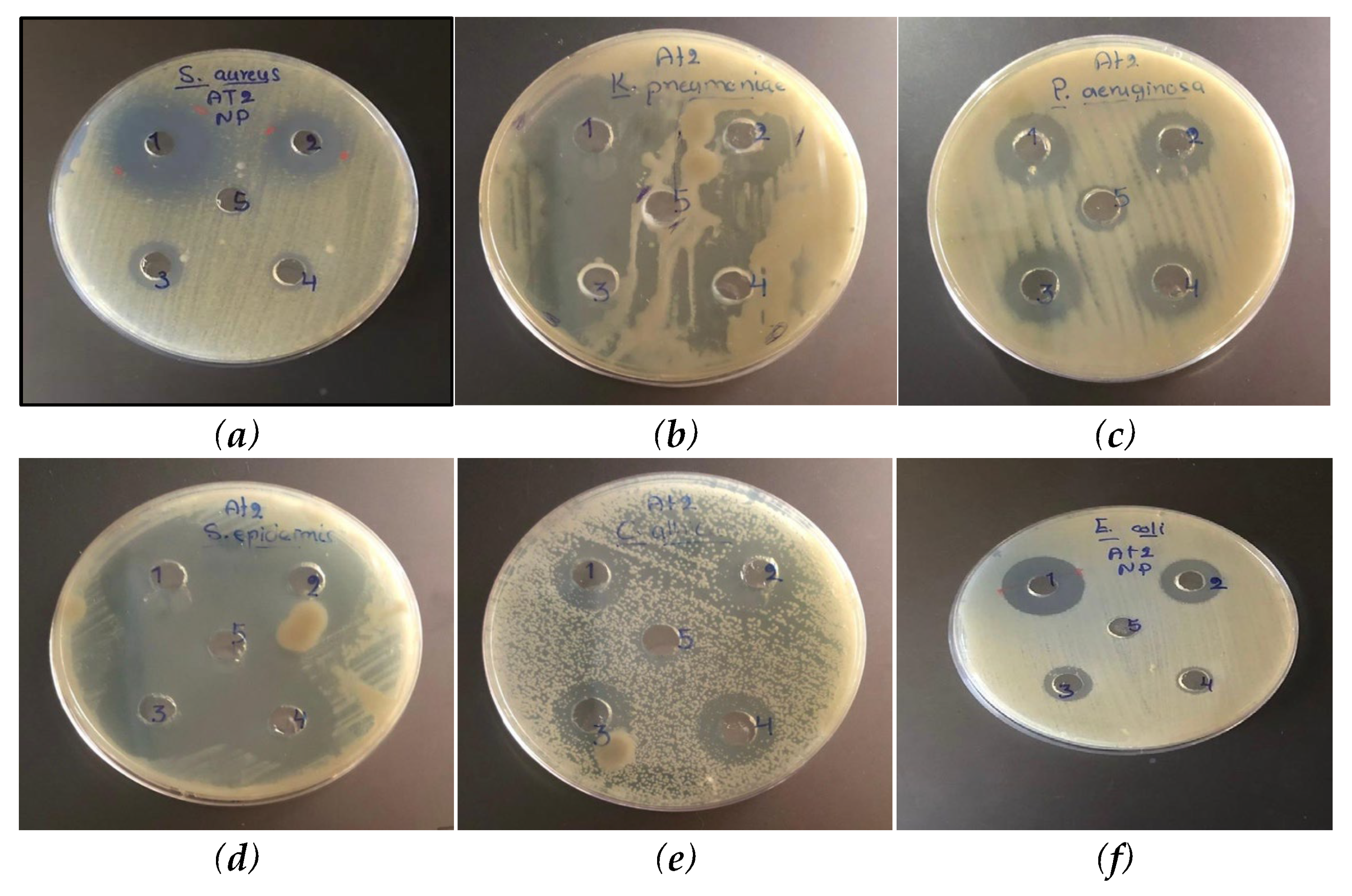

3.3. Antibacterial and Antifungal Activity

3.4. Minimum Inhibitory Concentration (MIC)

3.5. Total Flavonoid and Phenolic Composition

3.6. Antioxidant Capacity

3.7. Enzyme-Inhibitory Assay

3.8. Mechanistic Discussion

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Amin, H.I.M.; Ibrahim, M.F.; Hussain, F.H.; Sardar, A.; Vidari, G. Phytochemistry and ethnopharmacology of some medicinal plants used in the Kurdistan Region of Iraq. Nat. Prod. Commun. 2016, 11, 291–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, H.M. Medicinal plants used in traditional medicine among populations in Hawler (Erbil) Province, Kurdistan Region, Iraq. J. Herbs Spices Med. Plants 2025, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amin, H.I.M.; Hussain, F.H.; Maggiolini, M.; Vidari, G. Bioactive constituents from the traditional Kurdish plant Iris persica. Nat. Prod. Commun. 2018, 13, 1934578X1801300907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseini, S.H.; Sadeghi, Z.; Hosseini, S.V.; Bussmann, R.W. Ethnopharmacological study of medicinal plants in Sarvabad, Kurdistan province, Iran. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2022, 288, 114985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pieroni, A.; Sõukand, R.; Amin, H.I.M.; Zahir, H.; Kukk, T. Celebrating multi-religious co-existence in Central Kurdistan: The bio-culturally diverse traditional gathering of wild vegetables among Yazidis, Assyrians, and Muslim Kurds. Hum. Ecol. 2018, 46, 217–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizvi, S.A.A.; Einstein, G.P.; Tulp, O.L.; Sainvil, F.; Branly, R. Introduction to traditional medicine and their role in prevention and treatment of emerging and re-emerging diseases. Biomolecules 2022, 12, 1442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fahim, M.; Shahzaib, A.; Nishat, N.; Jahan, A.; Bhat, T.A.; Inam, A. Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles: A comprehensive review of methods, influencing factors, and applications. JCIS Open 2024, 16, 100125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jodha, B.; Jagrawat, A.; Patel, S. Nanotechnological Aspects in the Development of Phytotherapeutics Against Metabolic Disorders. In Plant-Based Drug Discovery; Bisht, M., Singh, A., Srivastava, A.K., Eds.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2026; pp. 461–494. ISBN 9780443316982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edo, G.I.; Mafe, A.N.; Ali, A.B.M.; Akpoghelie, P.O.; Yousif, E.; Isoje, E.F.; Igbuku, U.A.; Zainulabdeen, K.; Owheruo, J.O.; Essaghah, A.E.; et al. Eco-friendly nanoparticle phytosynthesis via plant extracts: Mechanistic insights, recent advances, and multifaceted uses. Nano TransMed 2025, 4, 100080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanna, D.H.; Nady, D.S.; Wasef, M.W.; Fakhry, M.H.; Mohamed, F.S.; Isaac, D.M.; Kirolos, M.M.; Azmy, M.S.; Hakeem, G.E.; Fathy, C.A. Plant-derived nanoparticles: Green synthesis, factors, and bioactivities. Next Mater. 2025, 9, 101275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayub, A.; Wani, A.K.; Malik, S.M.; Ayub, M.; Singh, R.; Chopra, C.; Malik, T. Green nanoscience for healthcare: Advancing biomedical innovation through eco-synthesized nanoparticle. Biotechnol. Rep. 2025, 47, e00913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banjara, R.A.; Kumar, A.; Aneshwari, R.K.; Satnami, M.L.; Sinha, S.K. A comparative analysis of chemical vs. green synthesis of nanoparticles and their various applications. Environ. Nanotechnol. Monit. Manag. 2024, 22, 100988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardoso, B.; Nobrega, G.; Afonso, I.S.; Ribeiro, J.E.; Lima, R.A. Sustainable green synthesis of metallic nanoparticle using plants and microorganisms: A review of biosynthesis methods, mechanisms, toxicity, and applications. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2025, 13, 116921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lodi, R.S.; Jia, X.; Yang, P.; Peng, C.; Dong, X.; Han, J.; Liu, X.; Wan, L.; Peng, L. Whole genome sequencing and annotations of Trametes sanguinea ZHSJ. Sci. Data 2025, 12, 1460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pourmadadi, M.; Holghoomi, R.; Shamsabadipour, A.; Maleki-baladi, R.; Rahdar, A.; Pandey, S. Copper nanoparticles from chemical, physical, and green synthesis to medicinal application: A review. Plant Nano Biology 2024, 8, 100070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keabadile, O.P.; Aremu, A.O.; Elugoke, S.E.; Fayemi, O.E. Green and traditional synthesis of copper oxide nanoparticles—Comparative study. Nanomaterials 2020, 10, 2502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Husni, P.; Ramadhania, Z.M. Plant extract loaded nanoparticles. Indones. J. Pharm. 2021, 3, 38–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gawande, M.B.; Goswami, A.; Felpin, F.X.; Asefa, T.; Huang, X.; Silva, R.; Varma, R.S. Cu and Cu-based nanoparticles: Synthesis and applications in catalysis. Chem. Rev. 2016, 116, 3722–3811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, P.; Kim, Y.; Cho, H.; Kim, K.-S. Synergistic action between copper oxide (CuO) nanoparticles and anthraquinone-2-carboxylic acid (AQ) against Staphylococcus aureus. J. Compos. Sci. 2023, 7, 135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Zhou, S.; Xu, X.; Du, Q. Copper-containing nanoparticles: Mechanism of antimicrobial effect and application in dentistry: A narrative review. Front. Surg. 2022, 9, 905892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nzilu, D.M.; Madivoli, E.S.; Makhanu, D.S.; Wanakai, S.I.; Kiprono, G.K.; Kareru, P.G. Green synthesis of copper oxide nanoparticles and its efficiency in degradation of rifampicin antibiotic. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 14030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woźniak-Budych, M.J.; Staszak, K.; Staszak, M. Copper and copper-based nanoparticles in medicine—Perspectives and challenges. Molecules 2023, 28, 6687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozhanova, K.; Alimanova, A.; Datkhayev, U.; Serikbayeva, E.; Kayupova, F.; Zhumalina, K.; Ashirov, M.; Zhakipbekov, K. Unlocking the potential: Exploring pharmacological properties from Apiaceae family. Pharmacia 2025, 72, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gebreslassie, Y.T.; Gebremeskel, F.G. Green and cost-effective biofabrication of copper oxide nanoparticles: Exploring antimicrobial and anticancer applications. Biotechnol. Rep. 2024, 41, e00828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uysal, S.; Zengin, G.; Locatelli, M.; Bahadori, M.B.; Mocan, A.; Bellagamba, G.; De Luca, E.; Mollica, A.; Aktumsek, A. Cytotoxic and enzyme inhibitory potential of two Potentilla species (P. speciosa L. and P. reptans Willd.) and their chemical composition. Front. Pharmacol. 2017, 8, e202402612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grochowski, D.M.; Pietrzak, W.; Aktumsek, A.; Granica, S.; Zengin, G.; Ceylan, R.; Locatelli, M.; Tomczyk, M. In vitro enzyme inhibitory properties, antioxidant activities, and phytochemical profile of Potentilla thuringiaca. Phytochem. Lett. 2017, 20, 365–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berman, H.M.; Westbrook, J.; Feng, Z.; Gilliland, G.; Bhat, T.N.; Weissig, H.; Shindyalov, I.N.; Bourne, P.E. The Protein Data Bank. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000, 28, 235–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woźniak, Ł.; Połaska, M.; Marszałek, K.; Skąpska, S. Photosensitizing Furocoumarins: Content in Plant Matrices and Kinetics of Supercritical Carbon Dioxide Extraction. Molecules 2020, 25, 3805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bartnik, M. Methoxyfuranocoumarins of natural origin—Updating biological activity research and searching for new directions—A review. Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. 2024, 46, 856–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phul, R.; Kaur, C.; Farooq, U.; Ahmad, T. Ascorbic acid assisted synthesis, characterization and catalytic application of copper nanoparticles. Mater. Sci. Eng. Int. J. 2018, 2, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasiliev, G.; Kubo, A.-L.; Vija, H.; Kahru, A.; Bondar, D.; Karpichev, Y.; Bondarenko, O. Synergistic antibacterial effect of copper and silver nanoparticles and their mechanism of action. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 9202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Amora, U.; Dacrory, S.; Hasanin, M.S.; Longo, A.; Soriente, A.; Kamel, S.; Raucci, M.G.; Ambrosio, L.; Scialla, S. Advances in the physico-chemical, antimicrobial and angiogenic properties of graphene-oxide/cellulose nanocomposites for wound healing. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15, 338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, J.; Yue, X.; Wang, T.; Zhang, Y.; Jin, Y.; Li, G. A cost-effective and sensitive voltammetric sensor for determination of baicalein in herbal medicine based on shuttle-shape α-Fe2O3 nanoparticle-decorated multi-walled carbon nanotubes. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2025, 717, 136850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amaliyah, S.; Pangesti, D.P.; Masruri, M.; Sabarudin, A.; Sumitro, S.B. Green synthesis and characterization of copper nanoparticles using Piper retrofractum Vahl extract as bioreductor and capping agent. Heliyon 2020, 6, e04636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonio-Pérez, A.; Durán-Armenta, L.F.; Pérez-Loredo, M.G.; Torres-Huerta, A.L. Biosynthesis of Copper Nanoparticles with Medicinal Plants Extracts: From Extraction Methods to Applications. Micromachine 2023, 14, 1882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Issa, K.D.; Othman, H.O.; Amin, H.I.M.; Omar, S.E.; Jihad, S.S.; Rasool, D.D.; Ahmed, A.S.; Ghazali, M.F.; Hussain, F.H. Sustainable Antimicrobial and Anticancer Agents: Eco-Friendly Synthesis of Copper Nanoparticles Using Biebersteinia multifida DC. Chem. Biodivers. 2024, 22, e202402612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhakar, A.; Srivastava, H.; Tiwari, P.; Rai, S.K. Insights into the optical properties of metal nanoparticles and their size-dependent aggregation dynamics. Microsc. Microanal. 2024, 30, 45–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giraldo-Osorno, P.M.; Aguirre-Afanador, L.B.; Barros, S.M.; Büscher, R.; Guttau, S.; Asa’ad, F.; Trobos, M.; Palmquist, A. Anodized Ti6Al4V-ELI electroplated with copper is bactericidal against Staphylococcus aureus and enhances macrophage phagocytosis. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Med. 2025, 36, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasieczna-Patkowska, S.; Cichy, M.; Flieger, J. Application of Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy in characterization of green synthesized nanoparticles. Molecules 2025, 30, 684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rusli, R.; Nurung, A.H.; Erwing, E. Minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) and minimum bactericidal concentration (MBC) of water and ethanol extracts of Eleutherine palmifolia (L.) Merr. against Staphylococcus aureus and Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J. Microbiol. Sci. 2024, 4, 161–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cushnie, T.P.T.; Lamb, A.J. Antimicrobial activity of flavonoids. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 2005, 26, 343–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khameneh, B.; Eskin, N.A.M.; Iranshahy, M.; Fazly Bazzaz, B.S. Phytochemicals: A Promising Weapon in the Arsenal against Antibiotic-Resistant Bacteria. Antibiotics 2021, 10, 1044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz-Puertas, R.; Álvarez-Martínez, F.J.; Falco, A.; Barrajón-Catalán, E.; Mallavia, R. Phytochemical-based nanomaterials against antibiotic-resistant bacteria. Polymers 2023, 15, 1392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iravani, S.; Varma, R.S. Green synthesis, characterization, and applications of nanoparticles. Molecules 2022, 27, 997. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed, S.; Saifullah; Ahmad, M.; Swami, B.L.; Ikram, S. Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using plants and their applications: A review. Arab. J. Chem. 2021, 14, 103083. [Google Scholar]

- Siddiqi, K.S.; Ur Rahman, A.; Tajuddin, N.; Husen, A. Properties of zinc oxide nanoparticles and their activity against microbes. Nanoscale Res. Lett. 2022, 17, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuhrotun, A.; Oktaviani, D.J.; Hasanah, A.N. Biosynthesis of gold and silver nanoparticles using phytochemical compounds. Molecules 2023, 28, 3240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siakavella, I.K.; Lamari, F.; Papoulis, D.; Orkoula, M.; Gkolfi, P.; Lykouras, M.; Avgoustakis, K.; Hatziantoniou, S. Effect of plant extracts on the characteristics of silver nanoparticles for topical application. Pharmaceutics 2020, 12, 1244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Periasamy, A.P.; Umasankar, Y.; Chen, S.-M. Nanomaterials—Acetylcholinesterase enzyme matrices for organophosphorus pesticides electrochemical sensors: A review. Sensors 2009, 9, 4034–4055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, J.; Zhang, Z.; Jin, A.; Tan, M.; Jiang, S.; Li, Y. Organic functional groups and their substitution sites in natural flavonoids: A review on their contributions to antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and analgesic capabilities. Food Sci. Nutr. 2025, 13, e70191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, W.; Stehbens, S.J.; Barnard, R.T.; Blaskovich, M.A.T.; Ziora, Z.M. Dysregulation of tyrosinase activity: A potential link between skin disorders and neurodegeneration. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 2024, 76, 13–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Y.; Wu, X.; Yao, X.; Chen, Y.; Ho, C.-T.; He, C.; Li, Z.; Wang, Y. Metabolite profiling, antioxidant and α-glucosidase inhibitory activities of buckwheat processed by solid-state fermentation with Eurotium cristatum YL-1. Food Res. Int. 2021, 143, 110262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gu, H.; Li, J.; Dai, P.; Sun, T.; Chen, C.; Guo, Z.; Fan, K. Polyphenol oxidase-like nanozymes. Adv. Mater. 2025, 37, e09346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shahidi, F.; Athiyappan, K.D. Polyphenol–polysaccharide interactions: Molecular mechanisms and potential applications in food systems—A comprehensive review. Food Prod. Process Nutr. 2025, 7, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, H.-D.; Choi, H.; Abekura, F.; Park, J.-Y.; Yang, W.-S.; Yang, S.-H.; Kim, C.-H. Naturally occurring tyrosinase inhibitors classified by enzyme kinetics and copper chelation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 8226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, P.; Feng, X.; Liu, S.; Jiang, Y. Traditional uses, phytochemistry, pharmacology and toxicology of Ruta graveolens L.: A critical review and future perspectives. Drug Des. Dev. Ther. 2024, 18, 6459–6485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ameh, T.; Gibb, M.; Stevens, D.; Pradhan, S.H.; Braswell, E.; Sayes, C.M. Silver and copper nanoparticles induce oxidative stress in bacteria and mammalian cells. Nanomaterials 2022, 12, 2402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Y.-P.; Chan, Y.-B.; Aminuzzaman, M.; Shahinuzzaman, M.; Djearamane, S.; Thiagarajah, K.; Leong, S.-Y.; Wong, L.-S.; Tey, L.-H. Green Synthesis and Characterization of Copper Oxide Nanoparticles from Durian (Durio zibethinus) Husk for Environmental Applications. Catalysts 2025, 15, 275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khoroshutin, A.V.; Lypenko, D.A.; Korlyukov, A.A.; Aleksandrov, A.E.; Buikin, P.A.; Moiseeva, A.A.; Botezatu, A.; Tokarev, S.D.; Tameev, A.R.; Fedorova, O.A. Methoxy-substituted naphthothiophenes—Single molecules vs. condensed phase properties and prospects for organic electronics applications. Synth. Met. 2022, 287, 117094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewick, P.M. Medicinal Natural Products: A Biosynthetic Approach, 2nd ed.; John Wiley and Sons: Chichester, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

| RT | % Area | Phytochemical Constituent | Molecular Formula | Cas No. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2.49 | 2.09 | 2,2-Dimethoxybutane | C6H14O2 | 3453-99-4 |

| 3.83 | 0.17 | 1,2-Hydrazinedicarboxamide | C2H6N4O2 | 110-21-4 |

| 5.8 | 1.17 | Glycerin | C3H8O3 | 56-81-5 |

| 8.61 | 0.64 | 1,2,3-Propanetriol, 1-acetate | C5H10O4 | 106-61-6 |

| 9.9 | 1.27 | Pyranone | C6H8O4 | 28564-83-2 |

| 10.83 | 5.07 | Octanoic acid | C8H16O2 | 124-07-2 |

| 12.53 | 2.6 | α-Monoacetin | C5H10O4 | 106-61-6 |

| 16 | 2.89 | 4-Methylmannitol | C7H16O6 | 130073 |

| 18.68 | 4.7 | 1,4-Di-O-acetyl-2,3,5-tri-O-methylribitol | C12H22O7 | 84925-40-6 |

| 19.46 | 0.63 | 2,4-Di-tert-butylphenol | C14H22O | 96-76-4 |

| 21.15 | 10.79 | Desulphosinigrin | C10H17NO6S | 5115-81-1 |

| 22.57 | 3.34 | D-Melezitose | C18H32O16 | 597-12-6 |

| 25.53 | 1.41 | 1-Heptatriacotanol | C16H32O2 | 105794-58-9 |

| 25.84 | 1.32 | Octanoic acid, octyl ester | C16H32O2 | 2306-88-9 |

| 26.81 | 0.77 | Isopsoralen | C11H6O3 | 523-50-2 |

| 29.16 | 0.72 | R-1 Methanandamide | C23H39NO2 | 157182-49-5 |

| 29.55 | 2.21 | Palmitic acid | C16H32O2 | 57-10-3 |

| 30.32 | 30.91 | Methoxsalen | C12H8O4 | 298-81-7 |

| 31.22 | 6.39 | α-Glyceryl linolenate | C21H36O4 | 18465-99-1 |

| 31.98 | 6.72 | Isopimpinellin | C13H10O5 | 482-27-9 |

| 32.76 | 0.64 | 3,3′,4,4′-Tetrahydrospirilloxanthin | C42H64O2 | 13833-01-7 |

| 34.87 | 12.54 | Triphenylphosphine oxide | C18H15OP | 791-28-6 |

| Microorganism | Zone of Inhibition (mm) | |

|---|---|---|

| Tt1 | Tt2 | |

| Escherichia coli | NBG | 3.0 |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa | 2.0 | 2.7 |

| Klebsiella pneumoniae | 3.5 | 5.0 |

| Staphylococcus aureus | 1.0 | 3.0 |

| Staphylococcus epidermidis | 3.0 | 5.0 |

| Candida albicans | 2.0 | 3.4 |

| Types of Microorganism | Samples | Concentration (µg/mL) | Controls | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 125 | 250 | 500 | 1000 | 2000 | +Ve | −Ve | ||

| Escherichia coli | Tt1 | 1.177 ± 0.07 | 0.972 ± 0.02 | 0.762 ± 0.08 | 0.400 ± 0.01 | 0.394 ± 0.03 | 0.833 ± 0.04 | 0.141 ± 0.02 |

| Tt2 | 0.840 ± 0.05 | 0.779 ± 0.05 | 0.126 ± 0.04 | 0.227 ± 0.04 | 0.332 ± 0.09 | |||

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa | Tt1 | 0.666 ± 0.09 | 0.419 ± 0.03 | 0.254 ± 0.01 | 0.205 ± 0.09 | 0.0165 ± 0.05 | 0.602 ± 0.01 | 0.119 ± 0.03 |

| Tt2 | 0.714 ± 0.10 | 0.377 ± 0.05 | 0.083 ± 0.04 | 0.221 ± 0.01 | 0.2985 ± 0.01 | |||

| Klebsiella pneumoniae | Tt1 | 1.009 ± 0.03 | 0.409 ± 0.04 | 0.774 ± 0.09 | 0.669 ± 0.09 | 0.604 ± 0.08 | 0.807 ± 0.04 | 0.096 ± 0.01 |

| Tt2 | 0.587 ± 0.11 | 0.027 ± 0.07 | 0.312 ± 0.05 | 0.088 ± 0.02 | 0.009 ± 0.01 | |||

| Staphylococcus aureus | Tt1 | 0.474 ± 0.10 | 0.475 ± 0.01 | 0.319 ± 0.06 | 0.099 ± 0.02 | 0.085 ± 0.05 | 0.575 ± 0.01 | 0.141 ± 0.06 |

| Tt2 | 0.911 ± 0.04 | 1.111 ± 0.13 | 0.297 ± 0.04 | 0.097± 0.03 | 0.258 ± 0.09 | |||

| Staphylococcus epidermidis | Tt1 | 0.605 ± 0.03 | 0.461 ± 0.08 | 0.478 ± 0.10 | 0.419± 0.07 | 0.379 ± 0.01 | 0.284 ± 0.02 | 0.099 ± 0.05 |

| Tt2 | 0.632 ± 0.11 | 0.419 ± 0.10 | 0.026 ± 0.07 | 0.153± 0.03 | 0.076 ± 0.01 | |||

| Candida albicans | Tt1 | 0.757 ± 0.08 | 0.838 ± 0.01 | 0.376 ± 0.06 | 0.340± 0.04 | 0.074 ± 0.05 | 0.699 ± 0.01 | 0.141 ± 0.04 |

| Tt2 | 0.378 ± 0.01 | 0.012 ± 0.05 | 0.032 ± 0.02 | 0.157± 0.07 | 0.216± 0.03 | |||

| Assay | Tt1 (Mean ± SD) | Tt2 (Mean ± SD) |

|---|---|---|

| Total phenol | 26.22 ± 0.50 mg GAE/g | 21.48 ± 0.61 mg GAE/g |

| Total flavonoids | 46.90 ± 0.56 mg QE/g | 39.03 ± 0.37 mg QE/g |

| Assay | Tt1 (Mean ± SD) | Tt2 (Mean ± SD) |

|---|---|---|

| DPPH (mg TE/g) | 61.42 ± 1.30 | 88.42 ± 0.96 |

| ABTS (mg TE/g) | 135.18 ± 2.84 | 128.89 ± 4.96 |

| FRAP (mg TE/g) | 103.52 ± 8.16 | 113.15 ± 1.22 |

| CUPRAC (mg TE/g) | 63.04 ± 1.87 | 82.11 ± 0.72 |

| PMA (mmol TE/g) | 2.56 ± 0.12 | 1.38 ± 0.03 |

| MCA (mg EDTA/g) | 6.94 ± 0.69 | 11.42 ± 1.44 |

| Inhibition Assay | Samples (Mean ± SD) | |

|---|---|---|

| Tt1 | Tt2 | |

| AChE (mg GALAE/g) | 2.29 ± 0.20 | 1.78 ± 0.09 |

| BChE (mg GALAE/g) | 0.89 ± 0.03 | NA |

| Tyrosinase (mg KAE/g) | 46.96 ± 3.18 | 52.62 ± 1.96 |

| Amylase (mmol ACAE/g) | 0.57 ± 0.01 | 0.35 ± 0.02 |

| Glucosidase (mmol ACAE/g) | 1.12 ± 0.02 | NA |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Abdullah, V.S.; Amin, K.Y.M.; Amin, H.I.M. Plant-Assisted Synthesis, Phytochemical Profiling, and Bioactivity Evaluation of Copper Nanoparticles Derived from Tordylium trachycarpum (Apiaceae). Biomolecules 2025, 15, 1693. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom15121693

Abdullah VS, Amin KYM, Amin HIM. Plant-Assisted Synthesis, Phytochemical Profiling, and Bioactivity Evaluation of Copper Nanoparticles Derived from Tordylium trachycarpum (Apiaceae). Biomolecules. 2025; 15(12):1693. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom15121693

Chicago/Turabian StyleAbdullah, Venos Saeed, Kamaran Younis M. Amin, and Hawraz Ibrahim M. Amin. 2025. "Plant-Assisted Synthesis, Phytochemical Profiling, and Bioactivity Evaluation of Copper Nanoparticles Derived from Tordylium trachycarpum (Apiaceae)" Biomolecules 15, no. 12: 1693. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom15121693

APA StyleAbdullah, V. S., Amin, K. Y. M., & Amin, H. I. M. (2025). Plant-Assisted Synthesis, Phytochemical Profiling, and Bioactivity Evaluation of Copper Nanoparticles Derived from Tordylium trachycarpum (Apiaceae). Biomolecules, 15(12), 1693. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom15121693