Abstract

This is an extensive review on epiphytic plants that have been used traditionally as medicines. It provides information on 185 epiphytes and their traditional medicinal uses, regions where Indigenous people use the plants, parts of the plants used as medicines and their preparation, and their reported phytochemical properties and pharmacological properties aligned with their traditional uses. These epiphytic medicinal plants are able to produce a range of secondary metabolites, including alkaloids, and a total of 842 phytochemicals have been identified to date. As many as 71 epiphytic medicinal plants were studied for their biological activities, showing promising pharmacological activities, including as anti-inflammatory, antimicrobial, and anticancer agents. There are several species that were not investigated for their activities and are worthy of exploration. These epipythes have the potential to furnish drug lead compounds, especially for treating cancers, and thus warrant indepth investigations.

1. Introduction

Epiphytes are plants that grow on other plants and are often known as air plants. They are mostly found in moist tropical areas on canopy tree-tops, where they exploit the nutrients available from leaf and other organic debris. These plants exist within the plantae and fungi kingdom. The term epiphyte itself was first introduced in 1815 by Charles-François Brisseau de Mirbel in “Eléments de physiologie végétale et de botanique” [1]. Epiphytes can be categorized into vascular and non-vascular epiphytic plants; the latter includes the marchantiophyta (liverworts), anthocerotophyta (hornworts), and bryophyta (mosses). The common epiphytes are mosses, ferns, liverworts, lichens, and the orchids. Epiphytes fall under two major categories: As holo- and hemi-epiphytes. While orchids are a good example of holo-epiphytes, the strangler fig is a hemi-epiphyte. Although geological studies have proposed the existence of epiphytes since the pleistone epoch, an epiphyte was first depicted in “the Badianus Manuscript” by Martinus de la Cruz in 1552, which showed the Vanilla fragrans, a hemi-epiphytic orchid, being used by the tribal communities in latin America for fragrance and aroma, usually hung around their neck [1].

Epiphytes have been a source of food and medicine for thousands of years. Since they grow in a unique ecological environment, they produce interesting secondary metabolites that often show exciting biological activities. There are notable reviews on non-vascular epiphytes, bryophyta, regarding their phytochemical and pharmacological activities [2,3,4,5]. There are also extensive reviews on epiphytic lichens covering secondary metabolites and their pharmacological activities [6,7,8,9]. The only available review on vascular epiphytes related to medicinal uses was focused on Orchidaceae [10]. Therefore, to the best of our knowledge, there is no extensive database of vascular epiphytes regarding their medicinal contribution.

There are 27,614 recorded species of vascular epiphytes belonging to 73 families and 913 genera [11]. Vascular epiphyte species are commonly found in pteridophyta, gymnosperms, and angiosperms plant groups, which are mostly found in the moist tropical areas on canopy tree tops, where they exploits the nutrients available from leaf and other organic debris [12,13]. In this study, information on vascular epiphytic medicinal plant species was collected using search engines (Web of Science, Scifinder Scholar, prosea, prota, Google scholar), medicinal plant books (Plant Resources of South-East Asia: Medicinal and Poisonous Plants [14,15,16], Plant Resources of South-East Asia: Cryptogams: Ferns and Fern Allies [17], Mangrove Guide for South-East Asia [18], Medicinal Plants of the Asia-Pacific [19], Medicinal Plants of the Guiana [20], Indian Medicinal Plants [21,22], Medicinal Plants of Bhutan [23], Medicinal and aromatic plants of Indian Ocean islands: Madagascar, Comoros, Seychelles and Mascarenes [24]), and the Indonesian Medicinal Plants Database [25]. Scientific names of the epiphytic medicinal plant species were compared against the Plantlist database for accepted names to avoid redundancy [26]. The time-frame threshold for data coverage was from the earliest available data until early 2020. Nevertheless, empirical knowledge regarding traditional medicinal plants was passed through generations using verbal or written communication, with verbal communication highly practiced by remote tribes [27,28]. It is possible that some oral traditional medical knowledge may not be reported and therefore not captured in this review. In this current study, we collected and reviewed 185 epiphytic medicinal plants reported in the literature, covering ethnomedicinal uses of epiphytes, their phytochemical studies and the pharmacological activities. The data collection approach used is presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Schematic data collection approach.

2. Ethnopharmacological Information of Vascular Epiphytic Medicinal Plants

2.1. Vascular Epiphytic Medicinal Plant Species Distribution within Plant Families

In this component of the study, we collated and analysed 185 of the medicinally used epiphytic plants species using ethnopharmacological information. This data (Table 1) includes the name of species, plant family, areas where the epiphytes are used in traditional medicines, part(s) of the plant being used in medication, how the medicine was prepared, and indications. Of the 185 medicinally used epiphytes, 53 species were ferns (mostly polipodiaceae), with 132 species belonging to the non-fern category. The Orchidaceae family contains the Dendrobium genus that contains the highest number of medicinal epiphytes, including 64 orchid species and 20 Dendrobium species. The Orchidaceae epiphytes were the majority of non-fern epiphytes. Cassytha filiformis L, Bulbophyllum odoratissimum (Sm.) Lindl. ex Wall., Cymbidium goeringii Rchb.f.) Rchb.f., Acrostichum aureum Limme, and Ficus natalensis Hochst. were the five most popular vascular epiphytic medicinal pants used (Figure 2).

Table 1.

Ethnopharmacological database of epiphytic medicinal plants.

Figure 2.

Five most popular medicinal epiphytes. (A) C. filiformis L. (B) B. odoratissimum (Sm.) Lindl. ex Wall. (C) C. goeringii (Rchb.f.) Rchb.f. (D) A. aureum Limme. (E) F. natalensis Hochst.

2.2. Distribution of Vascular Epiphytic Medicinal Plant Species by Country

Based on the available records, the data curation and analysis revealed that the Indigenous Indonesians have used 58 diverse epiphytic medicinal plant species throughout the archipelago and have the highest record compared to other tropical countries (Figure 3). China is second and is well known for its traditional medicine, including the use of epiphytes in medicament preparation. This is followed by the Indigenous Indians, with the well-established Ayurveda as a formal record of Indian medicinal plants. The traditional medicinal plant knowledge of Indonesa has been heavily influenced by Indian culture and enriched by Chinese and Arabian traders since the kingdom era [27].

Figure 3.

Density map showing a number of epiphytic medicinal plant species used by different countries. The number of species used is proportional to colour intensity.

2.3. Parts of Vascular Epiphytic Medicinal Plant Species Used in Traditional Medicines

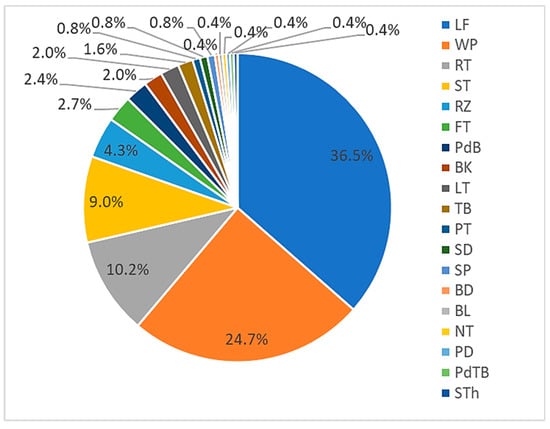

This review determined that leaves were the main plant components used in the traditional medicines (Figure 4). This was expected given they are more easily harvested (without excessive tools) and processed compared to other plant parts, e.g., the root and stem. As some epiphytes have a small biomass compared to higher trees, the whole plant is commonly harvested in medicament preparation. Interestingly, almost half of epiphytic medicinal plants were ferns, in which the stem-like stipe is prepared for medicine. Without haustoria (a specialised absorbing structure of a parasitic plant), the root and rhizome of epiphytic medicinal plants are easily harvested and prepared.

Figure 4.

Components of epiphytic plants used in medicinal preparations (represented in percentages). LF: leaf; WP: whole; RT: root; ST: stem, RZ: rhizome; FT: fruit; PdB: pseudobulbs; BK: bark; LT: latex; TB: tuber; PT: pith; SD: seed; SP: spore; BD: buds; BL: bulbs: NT: nutmeg; PD: pedi; PdTB: pseudotuber; STh: sheath.

2.4. Modes of Preparation and Dosage of Administration of Vascular Epiphytic Medicinal Plant Species in Traditional Medicines

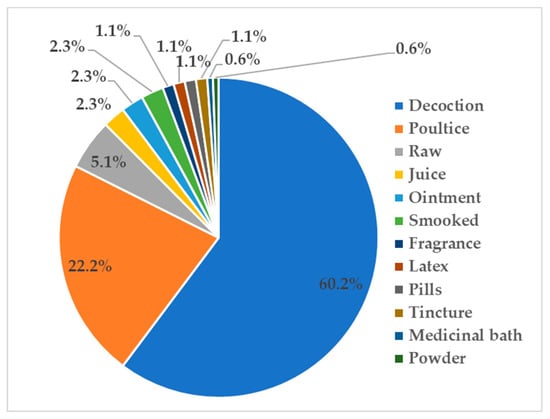

Generally, medicinally active secondary metabolites have a water solubility problem likely related to the lipophilic moieties in their structures [29]. Using boiling water, decoctions are able to increase the yield of secondary metabolites extracted from medicinal plants. Therefore, it is not surprising that decoctions are commonly used in traditional medicine preparations from plants (Figure 5). External applications are also commonly practiced in traditional medicinal therapies, including poultice (moist mass of material), raw, or less processed medicine. Poultices were commonly prepared for skin diseases while a decoction was ingested for internal infectious diseases (i.e., fever).

Figure 5.

Modes of preparation and administration of epiphytic medicinal plants (represented in percentages).

2.5. Category of Diseases Treated by Vascular Epiphytic Medicinal Plant Species

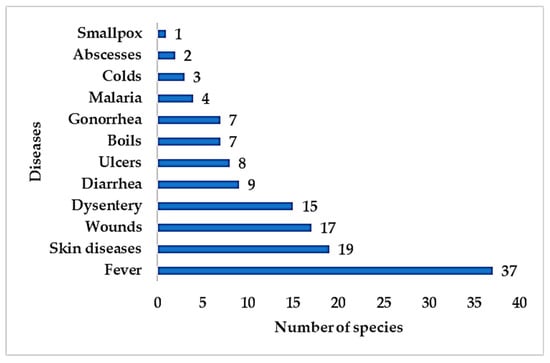

Interestingly, epiphytes have been used for treating various ailments, including both infectious and non-infectious diseases. Traditional communities described infectious diseases related to skin diseases (wounds, boils, ulcers, abscesses, smallpox) and non-skin diseases (fever, diarrhoea, ulcers, colds, worm infections, and malaria). A total of 54 epiphytic medicinal plant species were prescribed to treat skin diseases while 81 species to treat non-skin infectious diseases (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Number of epiphytic medicinal plant species used traditionally to treat infectious diseases.

Hygiene has been a serious issue in traditional communities as it gives rise to infectious diseases. Fever is a common symptom of pathogenic infection and has been treated using medicinal plants, including epiphytes. Hygiene issues are also a common cause of skin disease, wounds, dysentery, and diarrhoea in traditional communities.

3. Phytochemical Composition of Vascular Epiphytic Medicinal Plants

Epiphytes belong to a distinctive plant class as they do not survive in soil and this influences the secondary metabolites present. Epiphytes are physically removed from the terrestrial soil nutrient pool and grow upon other plants in canopy habitats, shaping epiphyte morphologies by the method in which they acquire nutrients [30]. Nutrients, such as nitrogen and phosphorus, are obtained from different sources, including canopy debris (through fall) and host tree foliar leaching [30], the latter influencing canopy soil nutrient cycling [31,32]. In the conversion of sunlight into chemical energy, the epiphyte often uses a specific carbon fixation pathway (CAM: Crassulacean acid metabolism) as a result of harsh environmental conditions [33], making them unique and thus worthwhile for scientific studies.

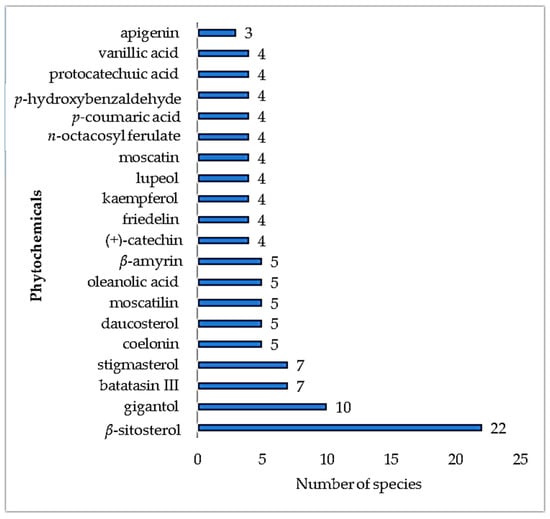

In the early 20th century, laboratory-based research on epiphytes studied the plant’s production of alkaloids, cyanogenetic, and organic sulfur compounds, with the plants producing limited quantities of these compounds [34]. Common plant steroids, e.g., β-sitosterol, have been shown to be present in 22 different epiphytic medicinal plants (Figure 7). This is possibly due to the function of the steroids as structural cell wall components, giving rise to a wide distribution across plant families and species. A further example of a common plant steroid present is stigmasterol.

Figure 7.

Number of epiphytic medicinal plant species producing the same secondary metabolites.

Table 2 lists the secondary metabolites identified in epiphytic medicinal plants and details the species, isolated compounds, and provides references. Currently, only 69 species have been phytochemically studied (23 fern and 46 non-fern epiphytes) and 842 molecules have been isolated from these epiphytic plants. Analysis of the literature showed epiphytes were able to produce a range of secondary metabolites, including terpenes and flavonoids, with no alkaloids being isolated from epiphytic fern medicinal plants thus far. β-Sitosterol, a common phytosterol in higher plants, was reported across fern genera. Interestingly, there is one unique terpene produced, hopane, which is commonly called fern sterol. Common flavonoids, such as kaempferol, quercetin, and flavan-3-ol derivatives (catechin), were also reported across the epiphytic ferns. Epiphytic pteridaceae, Acrostichum aureum Limme, is rich in quercetin [35]. Further analysis showed there were more secondary metabolites reported from non-fern epiphytic medicinal plants than from fern epiphytic medicinal plants, including terpene derivatives, flavonoids, and alkaloids. Included were flavanone, flavone, and flavonol derivatives but no flavan-3-ols were reported in these epiphytes so far. In the non-fern epiphytes, there were more phytochemical studies on orchid genera with additional classes of compounds reported, including penantrene derivatives (flavanthrinin, nudol, fimbriol B) [36,37] from the Bulbophyllum genus and the alkaloid dendrobine from the Dendrobium genus [38].

Table 2.

Phyctochemical constituents of epiphytic medicinal plants.

Therefore, while epiphytes may have limitations in accessing nutrients, adaptation has enabled them to successfully survive these environments. Studies on numerous medicinal epiphytes show that the unique environment does not constrain the plants from producing different types of secondary metabolites. These include terpenes, flavonoids, and alkaloids, especially the non-fern epiphytic medicinal plants.

4. Pharmacological Activities of Vascular Epiphytic Medicinal Plants

The pharmacological activities of medicinal epiphytes are summarised in Table 1, including the plant species, ethnopharmacological indication, and pharmacological test results. The ethnopharmacological uses of each plant are also present for a correlation and comparison with the pharmacological activities. There are a large number of phytochemical studies on the four fern-epiphytes (Stenochlaena palustris (Burm. F.) Bedd., Botrychum lanuginosum Wall.ex Hook & Grev., Pyrrosia petiolosa (Christ) Ching, Psilotum nudum (L.) P. Beauv) without any biological activity testing reported. This occurred to four non-fern epiphytes (Bulbophyllum vaginatum (Lindl.) Rchb.f, Mycaranthes pannea (Lindl.) S.C.Chen & J.J.Wood, Pholidota articulata Lindl., Viscum ovalifolium DC) and non-fern epiphytic medicinal plants. This lack of pharmacological testing limits scientific support for the traditional uses of these plants.

From the 191 collected records of epiphytic medicinal plants, around 71 species were subjected to bioactivity testing, with 25 of these species using crude extract samples. Although this testing represents almost 50% of the species examined, only a few of the pharmacological tests were related to ethnopharmacological claims. Here, we discuss selected species where the outcomes indicated a coherent relationship between bioactivities and traditional claims.

4.1. Infectious Disease Therapy

Research on epiphytes that have been used in infectious disease therapy include in wound healing, dysentery, and skin infections. A study on the methanol extract of Adiantum caudatum L., Mant showed anti-fungal activity against common fungi found in wounds (Aspergilus and Candida species) [39], including Aspergillus flavus, A. spinulosus, A. nidulans, and Candida albicans, with minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) values of 15.6, 15.6, 31.2, and 3.9 µg/mL, respectively. Gallic acid was one of the bioactive constituents [40]. The methanol extract of Ficus natalensis Hochst (a semi-epiphytic plant) showed anti-malarial activity against Plasmodium falciparum, with an half maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) value of 41.7 µg/mL, and weak bactericidal activity against Staphylococcus aureus, with an MIC value of 99 µg/mL [41]. These results became preliminary data for confirming its traditional uses as malarial fever therapy and wound healing. Phytochemical studies on Pyrrosia sheareri (Bak.) Ching successfully isolated several compounds and were subjected to anti-oxidant testing. While this was not in line with the plant’s ethnomedical uses for dysentery therapy [42], one of the isolated constituents was protocateuchic acid, which is known to possess anti-bacterial activity. It implies that the traditional uses of the epiphyte was for bacillary dysentery therapy.

4.2. Non-Infectious/Degenerative Disease-Related Therapy

An exploration on Drynaria species, highly prescribed in bone fracture therapy, successfully isolated flavonoid constituents that induce osteoblast proliferation [43]. Previous studies on Acrostichum aureum Limme failed to show its anti-bacterial activities [44] contrary to its traditional claims in wound management. However, patriscabratine 257 was isolated from the defatted methanol extract of whole plant of A. aureum, and subsequent testing showed it possessed anti-cancer activity in gastric cells and this supprted the traditional use of the plant in peptic ulcer therapy [35]. A decoction from the epiphyte Ficus deltoida has been used to treat diabetes. A study on the hot aqueous extract of this plant revealed anti-hyperglycemic activity by stimulating insulin secretion up to seven-fold. Furthermore, its activity mechanism was related to both the K+ATP-dependant and -non-dependant insulin secretion pathway [45]. However, further studies are required to identify the constituents responsible for the anti-hyperglycaemic activity.

The Indigenous people of Paraguay have used Catasetum barbatum Lindley to topically treat inflammation. Four bioactive compounds were isolated from this species and 2,7-dihydroxy-3,4,8-trimethoxyphenanthrene (confusarin) 595 showed the highest anti-inflammatory activity [46]. The study also revealed the compound to be a non-competitive inhibitor of the H1-receptor.

From the polypodiaceae family, the rhizome of Phymatodes scolopendria (burm.) Ching has been used to treat respiratory disorders. A bioassay-guided phytochemical study on Phymatodes scolopendria (Burm. f.) Pic. Serm. isolated 1,2-benzopyrone (coumarin) 209 as a bronchodilator [47].

5. Epiphytic Plant–Host Interactions on Secondary Metabolite Tapping

Secondary metabolite tapping has been an interesting study to reveal the molecular interactions between epiphytes and their host. This interaction was more visible when a physical channel between the two were developed. This channel (haustorium) made an epiphytic plant act as a parasite that enabled the plant to harvest molecular components from the host plant. A study on Scurulla oortiana (Korth.) Danser growth in three different host species (Citrus maxima, Persea Americana, and Camellia sinensis) identified three secondary metabolites (quercitrin, isoquercitrin, and rutin) in the S. oortiana (Korth.) Danser epiphyte growing on the three hosts [48]. Interestingly, extensive chromatographic and spectroscopic studies discovered that the flavonoids found in the S. oortiana (Korth.) Danser were independent of the host plants [48]. Secondary metabolite production in a host plant can also be triggered by the existence of a parasite, as discussed in a study on Tapirira guianensis infested by Phoradendron perrottetii, in which infested branches produced more tannin compare to non-infested branches, with infestation inducing a systemic response [48].

6. Conclusions

Epiphytes are the most beautiful vascular plants and contain interesting phytochemicals and possess exciting pharmacological activities. An analysis of the literature revealed 185 epiphytes that are used in traditional medicine, in which phytochemical studies identified a total of 842 secondary metabolites. Only 71 epiphytic medicinal plants were studied for their pharmacological activities and showed promising pharmacological activities, including anti-inflammatory, antimicrobial, and anticancer. Several species were not investigated for their activities and are worthy of exploration, including epiphytes from the Araceae (P. fragantissimum), Aralliaceae (S. caudata, S. elliptica, S. elliptifoliola, S. oxyphylla, S. simulans), and Asclepidaceae (Asclopidae sp., D. acuminate, D. benghalensis, D. imbricate, D. major, D. nummularia, D. platyphylla, D. purpurea, Toxocarpus sp) families, in which no phytochemical and pharmacological studies had been reported. These species have been used by Indigenous populations to treat both degenerative and nondegenerative diseases. It is known that there are examples of Indigenous populations living in protected forest reserves (e.g., in Indonesia) where epiphytes are used in their medicine, e.g., some species of Dischidia are used to treat fever, eczema, herpes etc.; these plants have not yet been studied. Therefore, the possibility of responsible bioprospecting exists (in compliance with the Nagoya protocol), which would be invaluable in biodiscovery knowledge as well as in mutual benefit sharing agreements.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.S.N., P.W., P.A.K.; data curation and analysis, A.S.N.; making and editing of the figures, A.S.N.; writing—original draft preparation, A.S.N., P.W., P.A.K.; writing—review and editing, A.S.N., B.T., P.W., P.A.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Acknowledgments

ASN thanks to University of Jember and University of Wollongong for research support. Authors thank to Frank Zich (Australian Tropical Herbarium & National Research Collections Australia) for providing taxonomy consultation.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Benzing, D.H. Vascular Epiphytes: General Biology and Related Biota; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Asakawa, Y.; Ludwiczuk, A. Chemical Constituents of Bryophytes: Structures and Biological Activity. J. Nat. Prod. 2018, 81, 641–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asakawa, Y.; Ludwiczuk, A.; Nagashima, F. Phytochemical and biological studies of bryophytes. Phytochemistry 2013, 91, 52–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ludwiczuk, A.; Asakawa, Y. Bryophytes as a source of bioactive volatile terpenoids—A review. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2019, 132, 110649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sabovljevic, M.S.; Sabovljevic, A.D.; Ikram, N.K.K.; Peramuna, A.; Bae, H.; Simonsen, H.T. Bryophytes—An emerging source for herbal remedies and chemical production. Plant Genet. Resour. 2016, 14, 314–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basnet, B.B.; Liu, H.; Liu, L.; Suleimen, Y.M. Diversity of anticancer and antimicrobial compounds from lichens and lichen-derived fungi: A systematic review (1985–2017). Curr. Org. Chem. 2018, 22, 2487–2500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kekuda, T.R.P.; Lavanya, D.; Rao, P. Lichens as promising resources of enzyme inhibitors: A review. J. Drug Deliv. Ther. 2019, 9, 665–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrestha, G.; Clair, L.L. Lichens: A promising source of antibiotic and anticancer drugs. Phytochem. Rev. 2013, 12, 229–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solárová, Z.; Liskova, A.; Samec, M.; Kubatka, P.; Büsselberg, D.; Solár, P. Anticancer Potential of Lichens’ Secondary Metabolites. Biomolecules 2020, 10, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sut, S.; Maggi, F.; Dall’Acqua, S. Bioactive Secondary Metabolites from Orchids (Orchidaceae). Chem. Biodivers. 2017, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zotz, G. The systematic distribution of vascular epiphytes—A critical update. Bot. J. Linn. Soc. 2013, 171, 453–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Köster, N.; Nieder, J.; Barthlott, W. Effect of host tree traits on epiphyte diversity in natural and anthropogenic habitats in ecuador. Biotropica 2011, 43, 685–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zotz, G.; Hietz, P. The physiological ecology of vascular epiphytes: Current knowledge, open questions. J. Exp. Bot. 2001, 52, 2067–2078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Padua, L.S.; Bunyapraphatsō̜n, N.; Lemmens, R.H.M.J.; Foundation, P. Plant Resources of South-East Asia: Medicinal and Poisonous Plants 1; Backhuys Publishers: Leiden, The Netherlands, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- van Valkenburg, J.L.C.H.; De Padua, L.S.; Bunyapraphatsara, N.; Lemmens, R.H.M.J.; Foundation, P. Plant Resources of South-East Asia: Medicinal and Poisonous Plants 2; Backhuys Publishers: Leiden, The Netherlands, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Bunyapraphatsō̜n, N.; Lemmens, R.H.M.J.; Foundation, P. Plant Resources of South-East Asia: Medicinal and Poisonous Plants 3; Backhuys Publishers: Leiden, The Netherlands, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- De Winter, W.P. Plant Resources of South-East Asia: Cryptogams: Ferns and Fern Allies; Backhuys Publishers: Kerkwerve, The Netherlands, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Giesen, W.; Wulffraat, S.; Zieren, M.; Scholten, L. Mangrove Guidebook for Southeast Asia; FAO and Wetlands International: Bangkok, Thailand, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Wiart, C. Medicinal Plants of the Asia-Pacific: Drugs for the Future; World Scientific: Singapore, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- DeFilipps, R.A.; Crepin, J.; Maina, S.L. Medicinal Plants of the Guianas (Guyana, Surinam, French Guiana); National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution: Washington, DC, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Praptosuwiryo, T.N. Drynaria (Bory) J. Smith. In Plant Resources of South-East Asia No 15(2): Ferns and Fern Allies; De Winter, W.P., Amoroso, V.B., Eds.; Backhuys: Leiden, The Netherlands, 2003; pp. 101–104. [Google Scholar]

- Warrier, P.K.; Nambiar, V.P.K.; Raman-Kutty, C. Indian Medicinal Plants; Orient Longman Ltd.: Hyderabad, India, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Wangchuk, P.; Yeshi, K.; Jamphel, K. Pharmacological, ethnopharmacological, and botanical evaluation of subtropical medicinal plants of Lower Kheng region in Bhutan. Integr. Med. Res. 2017, 6, 372–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gurib-Fakim, A.; Brendler, T. Medicinal and Aromatic Plants of Indian Ocean islands: Madagascar, Comoros, Seychelles and Mascarenes; Medpharm Scientific Publisher: Stuttgart, Germany, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Anonim. Medicinal Herb Index in Indonesia; PT Eisai Indonesia: Jakarta, Indonesia, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- The Plant List. Available online: http://www.theplantlist.org/ (accessed on 3 January 2020).

- Nugraha, A.S.; Keller, P.A. Revealing indigenous Indonesian traditional medicine: Anti-infective agents. Nat. Prod. Commun. 2011, 6, 1953–1966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roosita, K.; Kusharto Clara, M.; Sekiyama, M.; Fachrurozi, Y.; Ohtsuka, R. Medicinal plants used by the villagers of a Sundanese community in West Java, Indonesia. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2008, 115, 72–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leeson, P.D.; Springthorpe, B. The influence of drug-like concepts on decision-making in medicinal chemistry. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2007, 6, 881–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardelu’s, C.L.; Mack, M.C. The nutrient status of epiphytes and their host trees along an elevational gradient in Costa Rica. Plant Ecol. 2010, 207, 25–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benner, J.W.; Conroy, S.; Lunch, C.; Toyoda, N. Phosphorus fertilization increases the abudance and nitrogenase activity of the cyanolichen Pseudocyphellaria crocata in Hawaian Montane Forest. Biotropica 2007, 39, 400–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardelu’s, C.L.; Mack, M.C.; Woods, C.L.; DeMarco, J.; Treseder, K.K. Nutrient cycling in canopy and terrestrial soils at lowland rainforest site, Costa Rica. Plant Soil 2009, 318, 47–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reinert, F. Epiphytes: Photosynthesis, water balance and nutrients. Oecologia Bras. 1998, 4, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- McNair, J.B. Epiphytes, parasites and geophytes and the production of alkaloids, cyanogenetic and organic sulfur compounds. Am. J. Bot. 1941, 28, 733–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uddin, S.J.; Grice, D.; Tiralongo, E. Evaluation of cytotoxic activity of patriscabratine, tetracosane and various flavonoids isolated from the Bangladeshi medicinal plant Acrostichum aureum. Pharm. Biol. 2012, 50, 1276–1280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leong, Y.W.; Kang, C.C.; Harrison, L.J.; Powell, A.D. Phenanthrenes, dihydrophenanthrenes and bibenzyls from the orchid Bulbophyllum Vaginatum. Phytochem. 1996, 44, 157–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estrada, S.; López-Guerrero, J.J.; Villalobos-Molina, R.; Mata, R. Spasmolytic stilbenoids from Maxillaria densa. Fitoterapia 2004, 75, 690–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okamoto, T.; Natsume, M.; Onaka, T.; Uchimaru, F.; Shimizu, M. Alkaloidal constituents of Dendrobium nobile (Orchidaceae). Structure determination of 4-hydroxydendroxine and nobilomethylene. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 1972, 20, 418–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chellan, G.; Shivaprakash, S.; Karimassery Ramaiyar, S.; Varma, A.K.; Varma, N.; Thekkeparambil Sukumaran, M.; Rohinivilasam Vasukutty, J.; Bal, A.; Kumar, H. Spectrum and prevalence of fungi infecting deep tissues of lower-limb wounds in patients with type 2 diabetes. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2010, 48, 2097–2102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, M.; Singh, N.; Khare, P.B.; Rawat, A.K.S. Antimicrobial activity of some important Adiantum species used traditionally in indigenous systems of medicine. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2008, 115, 327–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krief, S.; Huffman, M.A.; Sevenet, T.; Hladik, C.M.; Grellier, P.; Loiseau, P.M.; Wrangham, R.W. Bioactive properties of plant species ingested by chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes schweinfurthii) in the Kibale National Park, Uganda. Am. J. Primatol. 2006, 68, 51–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, G.; Wang, M. Chemical constituents of Pyrrosia sheareri (Bak.) Ching. Nanjing Yaoxueyuan Xuebao 1984, 15, 40–44. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.L.; Wang, N.L.; Gao, H.; Zhang, G.; Qin, L.; Wong, M.S.; Yao, X.S. Phenylpropanoid and flavonoids from osteoprotective fraction of Drynaria fortunei. Nat. Prod. Res. 2010, 24, 1206–1213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, H.Y.; Lim, Y.Y.; Tan, S.P. Antioxidative, tyrosinase inhibiting and antibacterial activities of leaf extracts from medicinal ferns. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 2009, 73, 1362–1366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adam, Z.; Khamis, S.; Ismail, A.; Hamid, M. Ficus deltoidea: A potential alternative medicine for diabetes mellitus. Evid. Based Complement. Alternat. Med. 2012, 2012, 632763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shimizu, M.; Shogawa, H.; Hayashi, T.; Arisawa, M.; Suzuki, S.; Yoshizaki, M.; Morita, N.; Ferro, E.; Basualdo, I.; Berganza, L.H. Antiinflammatory constituents of topically applied crude drugs. III. Constituents and anti-inflammatory effect of Paraguayan crude drug “Tamandá cuná” (Catasetum barbatum LINDLE). Chem. Pharm. Bull. 1988, 36, 4447–4452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramanitrahasimbola, D.; Rakotondramanana, D.A.; Rasoanaivo, P.; Randriantsoa, A.; Ratsimamanga, S.; Palazzino, G.; Galeffi, C.; Nicoletti, M. Bronchodilator activity of Phymatodes scolopendria (Burm.) Ching and its bioactive constituent. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2005, 102, 400–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kirana, C. Bio-active Compounds Isolated from Mistletoe (Scurulla oortiana (Korth.) Danser) Parasitizing Tea Plant (Camellia sinensis L.). Master’s thesis, University of Adelaide, Adelaide, Australia, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Anonim. Jenis Paku Indonesia; Bali Pustaka: Jakarta, Indonesia, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Burkill, I. A dictionary of the Economic Products of the Malay Peninsula; Government of Malaysia and Singapore: Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Djumidi, H. Inventaris Tanaman Obat Indonesia V; Balai Penelitian Tanaman Obat: Tawangmangu, Indonesia, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Rusea, G. Asplenium L. In Plant Resources of South-East Asia No 15(2): Ferns and Fern Allies; De Winter, W.P., Amoroso, V.B., Eds.; Backhuys: Leiden, The Netherlands, 2003; pp. 61–62. [Google Scholar]

- Baltrushes, N. Medical Ethnobotany, Phytochemistry, and Bioactivity of the Ferns of Moorea, French Polynesia. Senior. Honors Thesis, University of California, Berkeley, CA, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Mannan, M.M.; Maridass, M.; Victor, B. A review on the potential uses of ferns. Ethnobot. Leafl. 2008, 2, 281–285. [Google Scholar]

- Manickam, V.S.; Irudayaraj, V. Pteridophytes Flora of the Western Ghats of South India; BI Publications Pvt Ltd.: New Dehli, India, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Luziatelli, G.; Sorensen, M.; Theilade, I.; Molgaard, P. Ashaninka medicinal plants: A case study from the native community of Bajo Quimiriki, Junin, Peru. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2010, 6, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, H.B. Potential medicinal pteridophytes of India and their chemical constituents. J. Econ. Tax. Bot. 1999, 23, 63–78. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmad, F.B.; Holdsworth, D.K. Medicinal plants of Sarawak, Malaysia, part I. The Kedayans. Pharm. Biol. 1994, 32, 384–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, T.H.; Kashiwada, Y.; Nonaka, G.I.; Nishioka, I. Flavan-3-ol and proanthocyanidin allosides from Davallia divaricata. Phytochemistry 1989, 28, 891–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vargas Gonzalez, J.F.; Yesares Ferrer, M. Extraction of α-D-glucooctono-δ-lactone enediol from ferns, as a drug for the treatment of psoriasis. Spain Patent 2012734, 1 April 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, H.C.; Huang, G.J.; Agrawal, D.C.; Kuo, C.L.; Wu, C.R.; Tsay, H.S. Antioxidant activities and polyphenol contents of six folk medicinal ferns used as “Gusuibu”. Bot. Stud. 2007, 48, 397–406. [Google Scholar]

- Praptosuwiryo, T.N.; Jansen, P.C.M. Davallia parvula Wall. Ex Hook. & Grev. In Plant resources of South-East Asia 15 (2). Cryptograms: Ferns and Fern Allies; de Winter, W.P.D., Amoroso, V.B., Eds.; Prosea Foundation by Backhuys Publishes: Leiden, The Netherlands, 2003; p. 92. [Google Scholar]

- Praptosuwiryo, T.N.; Jansen, P.C.M. Davalia J.E. Smith. In Plant Resources of South-East Asia No 15(2): Ferns and Fern Allies; De Winter, W.P., Amoroso, V.B., Eds.; Backhuys: Leiden, The Netherlands, 2003; pp. 89–90. [Google Scholar]

- Grepin, F.; Grepin, M. La Medicine Tahitienne traditionnelle, Raau Tahiti.; Societe Nouvelle des Editions du Pacifique.: Papeete, Tahiti, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Petard, P. Raau Tahiti: The Use of Polynesia Medicinal Plants in Tahitian Medicine; South Pacific Commission: Noumea, New Caledonia, 1972. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.H.; Chang, F.R.; Lin, Y.J.; Hsieh, P.W.; Wu, M.J.; Wu, Y.C. Identification of antioxidants from rhizome of Davallia solida. Food Chem. 2008, 107, 684–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boydron-Le Garrec, R.; Benoit, E.; Sauviat, M.P.; Lewis, R.J.; Molgó, J.; Laurent, D. Ability of some plant extracts, traditionally used to treat ciguatera fish poisoning, to prevent the in vitro neurotoxicity produced by sodium channel activators. Toxicon 2005, 46, 625–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rancon, S.; Chaboud, A.; Darbour, N.; Comte, G.; Bayet, C.; Simon, P.N.; Raynaud, J.; Di, P.A.; Cabalion, P.; Barron, D. Natural and synthetic benzophenones: Interaction with the cytosolic binding domain of P-glycoprotein. Phytochemistry 2001, 57, 553–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renimel, I.; Olivier, M.; Andre, P. Use of Davallia Plant Extract in Cosmetic and Pharmaceutical Compositions for the Treatment of Skin Aging. France Patent 2757395A1, 26 June 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Benjamin, A.; Manickam, V.S. Medicinal pteridophytes from Western Ghats. Indian J. Tradit. Knowl. 2007, 6, 611–618. [Google Scholar]

- Caniago, I.; Siebert, S.F. Medicinal plant ecology, knowledge and conservation in Kalimantan, Indonesia (FN1). Econ. Bot. 1998, 52, 229–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lachman-White, D.A.; Adams, C.D.; Trotz, U.O.D. A Guide to the Medicinal Plants of Coastal Guyana; Commonwealth Science Council: London, UK, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Boonkerd, T. Huperzia carinata (desv. ex Poir.) Trevis. In Plant resources of South-East Asia No 15(2): Ferns and Fern Allies; De Winter, W.P., Amoroso, V.B., Eds.; Backhuys: Leiden, The Netherlands, 2003; pp. 112–113. [Google Scholar]

- Choo, C.Y.; Hirasawa, Y.; Karimata, C.; Koyama, K.; Sekiguchi, M.; Kobayashi, J.i.; Morita, H. Carinatumins A–C, new alkaloids from Lycopodium carinatum inhibiting acetylcholinesterase. Bioorganic Med. Chem. 2007, 15, 1703–1707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amoroso, V.B. Huperzia phlegmaria (L) Rothm. In Plant resources of South-East Asia No 15(2): Ferns and Fern Allies; De Winter, W.P., Amoroso, V.B., Eds.; Backhuys: Leiden, The Netherlands, 2003; pp. 113–115. [Google Scholar]

- Ragupathy, S.; Steven, N.; Maruthakkutti, M.; Velusamy, B.; Ul-Huda, M. Consensus of the ‘Malasars’ traditional aboriginal knowledge of medicinal plants in the Velliangiri holy hills, India. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2008, 4, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wittayalai, S.; Sathalalai, S.; Thorroad, S.; Worawittayanon, P.; Ruchirawat, S.; Thasana, N. Lycophlegmariols A-D: Cytotoxic serratene triterpenoids from the club moss Lycopodium phlegmaria L. Phytochemistry 2012, 76, 117–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimudzi, C.; Bosch, C.H. Lycopodium. In Volume 11 of Plant Resources of Tropical Africa: Medicinal Plants 1; Schmelzer, G.H., Ed.; PROTA: Leiden, Netherland, 2008; pp. 366–369. [Google Scholar]

- Noweg, T.; Abdullah, A.R.; Nidang, D. Forest plants as vegetables for communities bordering the crocker range national park. ARBEC 2003, 1-3, 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Darnaedi, D.; Praptosuwiryo, T.N. Nephrolepsis Schott. In Plant resources of South-East Asia No 15(2): Ferns and Fern Allies; De Winter, W.P., Amoroso, V.B., Eds.; Backhuys: Leiden, The Netherlands, 2003; pp. 141–145. [Google Scholar]

- Christensen, H. Uses of Ferns in Two Indigenous Communities in Sarawak, Malaysia. In Holttum Memorial Volume; Johns, R.J., Ed.; Royal Botanic Gardens: Kew, UK, 1997; pp. 177–192. [Google Scholar]

- Ojo, O.O.; Ajayi, A.O.; Anibijuwon, I.I. Antibacterial potency of methanol extracts of lower plants. J. Zhejiang Univ. Sci. B 2007, 8, 189–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Rani, D.; Khare, P.B.; Dantu, P.K. In vitro antibacterial and antifungal properties of aqueous and non-aqueous frond extracts of Psilotum nudum, Nephrolepis biserrata and Nephrolepis cordifolia. Indian J. Pharm. Sci. 2010, 72, 818–822. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kumari, P.; Otaghvari, A.M.; Govindapyari, H.; Bahuguna, Y.M.; Uniyal, P.L. Some ethno-medicinally important Pterodophytes of India. In. J. Med. Arom. Plants 2011, 1, 18–22. [Google Scholar]

- Ong, H.C.; Aguilar, N.O. Ophioglossum pendulum L. In Plant Resources of South-East Asia No 15(2): Ferns and Fern Allies; De Winter, W.P., Amoroso, V.B., Eds.; Backhuys: Leiden, The Netherlands, 2003; pp. 151–153. [Google Scholar]

- Hatani, A.; Okumura, Y.; Maeda, H. Cell Activator, Skin Whitening Agent and Antioxidant Containing Plant Extract of Ophioglossum of Ophioglossaceae. Japan Patent 2005089375, 7 April 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Hovenkamp, P.H. Pyrrosia Mirbel. In Plant resources of South-East Asia No 15(2): Ferns and Fern Alies; De Winter, W.P., Amoroso, V.B., Eds.; Backhuys: Leiden, The Netherlands, 2003; pp. 170–174. [Google Scholar]

- Anonim. Materia Medika Indonesia; Departemen Kesehatan Republik Indonesia: Jakarta, Indonesia, 1989; Volume V. [Google Scholar]

- Abdul, R.M.D. Pengenalan dan Penggunaan Herba Ubatan; Orient Press Sdn. Bhd.: Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Dalimartha, S. Atlas Tumbuhan Obat Indonesia; PT. Pustaka Pembangunan: Jakarta, Indonesia, 2008; p. 89. [Google Scholar]

- Somchit, M.N.; Hassan, H.; Zuraini, A.; Chong, L.C.; Mohamed, Z.; Zakaria, Z.A. In vitro anti-fungal and anti-bacterial activity of Drymoglossum piloselloides L. Presl. against several fungi responsible for Athlete’s foot and common pathogenic bacteria. Afr. J. Microbiol. Res. 2011, 5, 3537–3541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nugraha, A.S.; Haritakun, R.; Keller, P.A. Constituents of the Indonesian epiphytic medicinal plant Drynaria rigidula. Nat. Prod. Commun. 2013, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neamsuvan, O.; Singdam, P.; Yingcharoen, K.; Sengnon, N. A survey of medicinal plants in mangrove and beach forests from sating Phra Peninsula, Songkhla Province, Thailand. J. Med. Plants Res. 2012, 6, 2421–2437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Wang, X.L.; Wang, N.L.; Zhang, Y.; Gao, H.; Pang, W.Y.; Wong, M.S.; Zhang, G.; Qin, L.; Yao, X.S. Effects of eleven flavonoids from the osteoprotective fraction of Drynaria fortunei (KUNZE) J. SM. on osteoblastic proliferation using an osteoblast-like cell line. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 2008, 56, 46–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wangchuk, P.; Pyne, S.G.; Keller, P.A. Ethnobotanical authentication and identification of Khrog-sman (Lower Elevation Medicinal Plants) of Bhutan. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2011, 134, 813–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majumdar, H.C.; Shyam, J.M.; Chowdhury, U.; Koch, D.; Roy, N. Traditional hepatoprotective herbal medicine of Koch tribe in the South-West Garo hills district, Meghalaya. Indian J. Tradit. Knowl. 2019, 18, 312–317. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, A.; Haque, E.; Mukhlesur, R.M.; Mosaddik, A.; Rahman, M.; Sultana, N. Isolation of antibacterial constituent from rhizome of Drynaria quercifolia and its sub-acute toxicological studies. Daru J. Fac. Pharm. Tehran Univ. Med Sci. 2007, 15, 205–211. [Google Scholar]

- Wangchuk, P.; Namgay, K.; Gayleg, K.; Dorji, Y. Medicinal plants of Dagala region in Bhutan: Their diversity, distribution, uses and economic potential. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2016, 12, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boonkerd, T.; de Winter, W.P. Loxogramme scolopendrina (Bory) C. Presl. In Plant resources of South-East Asia No 15(2): Ferns and Fern Allies; De Winter, W.P., Amoroso, V.B., Eds.; Backhuys: Leiden, The Netherlands, 2003; pp. 120–121. [Google Scholar]

- Syamsuhidayat, S.S.; Hutapea, J.R. Inventaris Tanaman Obat Indonesia; Badan Penelitian dan Pengembangan Kesehatan Departemen Kesehatan Republik Indonesia: Jakarta, Indonesia, 1991; Volume I. [Google Scholar]

- Darnaedi, D.; Praptosuwiryo, T.N. Platycerium bifucartum C. Chr. In Plant resources of South-East Asia No 15(2): Ferns and Fern Allies; De Winter, W.P., Amoroso, V.B., Eds.; Backhuys: Leiden, The Netherlands, 2003; pp. 157–159. [Google Scholar]

- May, L. The economic uses and associated folklore of ferns and fern allies. Bot. Rev. 1978, 44, 491–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nair, B.K. Medicinal fern of India. Bull. Nat. Bot. Gard. 1959, 29, 1–36. [Google Scholar]

- Suryana. Keanekaragaman jenos tumbuhan paku terestrial dan epifit di Kawasan PLTP Kamojang Kab. Garut Jawa Barat. J. Biot. 2009, 7, 20–26. [Google Scholar]

- Namba, T. Coloured illustration of Wakan-Yaku; Hoikusha: Osaka, Japan, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Masuda, K.; Yamashita, H.; Shiojima, K.; Itoh, T.; Ageta, H. Fern constituents: Triterpenoids isolated from rhizomes of Pyrrosia lingua L. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 1997, 45, 590–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Z.T.; Fang, Y.S.; Tai, Z.G.; Yang, M.H.; Xu, Y.Q.; Li, F.; Cao, Q.E. Phenolic content and radical scavenging capacity of 31 species of ferns. Fitoterapia 2008, 79, 581–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, S.Y.; Chen, C.; Zhang, H.Q.; Guo, H.Y.; Wang, H.; Wang, L.; Zhang, X.; Hua, S.N.; Yu, J.; Xiao, P.G.; et al. Identification of natural compounds with antiviral activities against SARS-associated coronavirus. Antivir. Res. 2005, 67, 18–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, C.Y. Antioxidant activity of Pyrrosia petiolosa. Fitoterapia 2008, 79, 64–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gan, R.Y.; Kuang, L.; Xu, X.R.; Zhang, Y.; Xia, E.Q.; Song, F.L.; Li, H.B. Screening of natural antioxidants from traditional Chinese medicinal plants associated with treatment of rheumatic disease. Molecules 2010, 15, 5988–5997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prakash, A.O.; Saxena, V.; Shukla, S.; Tewari, R.K.; Mathur, S.; Gupta, A.; Sharma, S.; Mathur, R. Anti-implantation activity of some indigenous plants in rats. Acta Eur. Fertil. 1985, 16, 441–448. [Google Scholar]

- Dai, H.; Mei, W.; Hong, K.; Zeng, Y.; Zhuang, L. Screening of the tumor cytotoxic activity of sixteen species of mangrove plants in Hainan. Zhongguo Haiyang Yaowu 2005, 24, 44–46. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, T. In vitro evaluation of antibacterial activity of Acrostichum aureum Linn. Indian J. Nat. Prod. Resour. 2012, 3, 135–138. [Google Scholar]

- Uddin, S.J.; Grice, I.D.; Tiralongo, E. Cytotoxic effects of bangladeshi medicinal plant extracts. Evid. Based Complement. Alternat. Med. 2011, 2011, 578092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, H.; Tawan, C.S. Taenitis blechnoides (Willd.) Swartz. In Plant Resources of South-East Asia No 15(2): Ferns and Fern Allies; De Winter, W.P., Amoroso, V.B., Eds.; Backhuys: Leiden, The Netherlands, 2003; pp. 188–190. [Google Scholar]

- Manandhar, P.N. Ethnobotanical observations on ferns and ferns allies of Nepals. J. Econ. Taxon. Bot. 1996, 12, 414–422. [Google Scholar]

- Joo, S.S.; Jang, S.K.; Kim, S.G.; Choi, J.S.; Hwang, K.W.; Lee, D.I. Anti-acne activity of Selaginella involvens extract and its non-antibiotic antimicrobial potential on Propionibacterium acnes. Phytother. Res. PTR 2008, 22, 335–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gayathri, V.; Asha, V.V.; John, J.A.; Subramoniam, A. Protection of immunocompromised mice from fungal infection with a thymus growth-stimulatory component from Selaginella involvens, a fern. Immunopharmacol. Immunotoxicol. 2011, 33, 351–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, P.L.; Hsu, Y.L.; Zao, C.W.; Damu, A.G.; Wu, T.S. Constituents of Vittaria anguste-elongata and their biological activities. J. Nat. Prod. 2005, 68, 1180–1184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tap, N.; Sosef, M.S.M. Schefflera J.R. Foster & J.G. Foster. In Plant Resources of South-East Asia No 12(1): Medicinal and Poisonous Plants 1; de Padua, L.S., Bunyapraphatsara, N., Lemmens, R.H.M.J., Eds.; Backhuys: Leiden, The Netherlands, 1999; pp. 433–438. [Google Scholar]

- Oshima, R.; Soda, M. Antibacterial Agent/Highly Safe Antibacterial Agent Obtained from Plants. Japan Patent 2000136141A, 16 May 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Chuakul, W.; Soonthornchareonnon, N.; Ruangsomboon, O. Dischidia bengalensis Colebr. In Plant Resources of South-East Asia No 12(3): Medicinal and Poisonous Plants 3; Lemmens, R.H.M.J., Bunyapraphatsara, N., Eds.; Backhuys: Leiden, The Netherlands, 2003; p. 172. [Google Scholar]

- Lemmens, R.H.M.J.; Bunyapraphatsara, N. Plat Resources of Sout-East Asia 12 (3): Medicinal and Poisonous Plants; Prosea Foundation by Backhuys Publishers: Leiden, The Netherlands, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Chuakul, W.; Soonthornchareonnon, N.; Ruangsomboon, O. Dischidia major (Vahl) Merr. In Plant Resources of South-East Asia No 12(3): Medicinal and Poisonous Plants 3; Lemmens, R.H.M.J., Bunyapraphatsara, N., Eds.; Backhuys: Leiden, The Netherlands, 2003; p. 172. [Google Scholar]

- Hynniewta, S.R.; Kumar, Y. Herbal remidies among the Khasi traditional healers and village folks in Meghalaya. Indian J. Tradit. Knowl. 2008, 7, 581–586. [Google Scholar]

- Chuakul, W.; Soonthornchareonnon, N.; Ruangsomboon, O. Dischidia nummularia R.Br. In Plant Resources of South-East Asia No 12(3): Medicinal and Poisonous Plants 3; Lemmens, R.H.M.J., Bunyapraphatsara, N., Eds.; Backhuys: Leiden, The Netherlands, 2003; p. 173. [Google Scholar]

- Chuakul, W.; Soonthornchareonnon, N.; Ruangsomboon, O. Dischidia purpurea Merr. In Plant Resources of South-East Asia No 12(3): Medicinal and Poisonous Plants 3; Lemmens, R.H.M.J., Bunyapraphatsara, N., Eds.; Backhuys: Leiden, The Netherlands, 2003; p. 173. [Google Scholar]

- Bosch, C.H. Impatiens niamniamensis Gilg. In PROTA (Plant Resources of Tropical Africa/Ressources Végétales de l’Afrique Tropicale); Grubben, G.J.H., Denton, O.A., Eds.; PROTA: Wageningen, The Netherlands, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Chand, K.; Rahuja, N.; Mishra, D.P.; Srivastava, A.K.; Maurya, R. Major alkaloidal constituent from Impatiens niamniamensis seeds as antihyperglycemic agent. Med. Chem. Res. 2011, 20, 1505–1508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiart, C. Ethnopharmacology of Medicinal Plants: Asia and the Pacific; Humana Press Inc.: Totowa, NJ, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Hariana, H.A. Tumbuhan Obat & Khasiatnya 3; Niaga Swadaya: Depok, Indonesia, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Wardini, T.H. Cassytha filiformis L. In Plant Resources of South-East Asia No 12(2): Medicinal and Poisonous Plants 2; van Valkenburg, J.L.C.H., Bunyapraphatsara, N., Eds.; Backhuys: Leiden, The Netherlands, 2001; pp. 142–144. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, C.W.; Ko, F.N.; Su, M.J.; Wu, Y.C.; Teng, C.M. Pharmacological evaluation of ocoteine, isolated from Cassytha filiformis, as an α1-adrenoceptor antagonist in rat thoracic aorta. Jpn. J. Pharmacol. 1997, 73, 207–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.C.; Chang, F.R.; Chao, Y.C.; Teng, C.M. Antiplatelet and vasorelaxing actions of aporphinoids from Cassytha filiformis. Phytother. Res. 1998, 12, S39–S41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoet, S.; Stevigny, C.; Block, S.; Opperdoes, F.; Colson, P.; Baldeyrou, B.; Lansiaux, A.; Bailly, C.; Quetin-Leclercq, J. Alkaloids from Cassytha filiformis and related aporphines: Antitrypanosomal activity, cytotoxicity, and interaction with DNA and topoisomerases. Planta Med. 2004, 70, 407–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, S.; Hullatti, K.K.; Kumar, S.; Tiwari, K.B. Comparative antioxidant activity of Cuscuta reflexa and Cassytha filiformis. J. Pharm. Res. 2012, 5, 441–443. [Google Scholar]

- Hoesen, D.D.H. Cuscuta asutralis R.Br. In Plant Resources of South-East Asia No 12(3): Medicinal and Poisonous Plants 3; Lemmens, R.H.M.J., Bunyapraphatsara, N., Eds.; Backhuys: Leiden, The Netherlands, 2003; pp. 144–145. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, S.J.; Suk, K.D. Inhibitory effects on melanin biosynthesis and tyrosinase activity, cytotoxicity in clone M-3 and antioxidant activity by Cuscuta japonica, C. australis, and C. chinensis extracts. Yakhak Hoechi 2006, 50, 421–428. [Google Scholar]

- Gaur, R.D.; Tiwari, J.K. Indigenous medicinal plants of Garhwal Himalaya (India): An ethnobotanical study. Proceedings of Medicinal and Poisonous Plants of the Tropics: Proceedings of Symposium 5-35 of the 14th International Botanical Congress (Compiler), Berlin, UK, 24 July–1 August 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Chopra, R.N.; Nayar, S.L.; Chopra, I.C.; Asolkar, L.V.; Kakkar, K.K.; Chakre, O.J.; Varma, B.S.; Council, S.; Industrial, R. Glossary of Indian Medicinal Plants; Council of Scientific & Industrial Research: New Delhi, India, 1956. [Google Scholar]

- Gupta, M.; Mazumder, U.K.; Pal, D.K.; Bhattacharya, S. Anti-steroidogenic activity of methanolic extract of Cuscuta reflexa roxb. stem and Corchorus olitorius Linn. seed in mouse ovary. Indian J. Exp. Biol. 2003, 41, 641–644. [Google Scholar]

- Awasthi, L.P. The purification and nature of an antiviral protein from Cuscuta reflexa plants. Arch. Virol. 1981, 70, 215–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmood, N.; Pacente, S.; Burke, A.; Khan, A.; Pizaa, C. Constituents of Cuscuta reflexa are anti-HIV agents. Antivir. Chem. Chemother. 1997, 8, 70–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pal, D.; Panda, C.; Sinhababu, S.; Dutta, A.; Bhattacharya, S. Evaluation of psychopharmacological effects of petroleum ether extract of Cuscuta reflexa Roxb. stem in mice. Acta Pol. Pharm. 2003, 60, 481–486. [Google Scholar]

- Pal, D.K.; Mandal, M.; Senthilkumar, G.P.; Padhiari, A. Antibacterial activity of Cuscuta reflexa stem and Corchorus olitorius seed. Fitoterapia 2006, 77, 589–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pandit, S.; Chauhan, N.S.; Dixit, V.K. Effect of Cuscuta reflexa Roxb on androgen-induced alopecia. J. Cosmet. Dermatol. 2008, 7, 199–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suresh, V.; Sruthi, V.; Padmaja, B.; Asha, V.V. In vitro anti-inflammatory and anti-cancer activities of Cuscuta reflexa Roxb. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2011, 134, 872–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poudel, A.; Kim, S.G.; Kim, D.K.; Kim, Y.K.; Lee, Y.S.; Lee, G.W.; Min, B.S.; Jung, H.J. Antioxidative and antiobesity activity of nepalese wild herbs. Nat. Prod. Sci. 2011, 17, 123–129. [Google Scholar]

- Lokvam, J.; Braddock, J.F.; Reichardt, P.B.; Clausen, T.P. Two polyisoprenylated benzophenones from the trunk latex of Clusia grandiflora (Clusiaceae). Phytochemistry 2000, 55, 29–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, M.P.; Solís, P.N.; Calderón, A.I.; Guinneau-Sinclair, F.; Correa, M.; Galdames, C.; Guerra, C.; Espinosa, A.; Alvenda, G.I.; Robles, G.; et al. Medical ethnobotany of the Teribes of Bocas del Toro, Panama. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2005, 96, 389–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubitzki, K.; Kadereit, J.W. The Families and Genera of Vascular Plants: Flowering Plants, Dicotyledons. In Lamiales (Except Acanthaceae Including Avicenniaceae); Springer: Heidelberg, Germany, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Esposito Avella, M.; Gupta, M.P.; Calderon, A.; Zamora, V.O.; Buitrago de Tello, R. The analgesic and anti-inflammatory effects of Drymonia serrulata (Jacq.) Mart. Rev. Med. Panama 1993, 18, 211–216. [Google Scholar]

- Suciati, S.; Lambert, L.K.; Ross, B.P.; Deseo, M.A.; Garson, M.J. Phytochemical study of Fagraea spp. uncovers a new terpene alkaloid with anti-Inflammatory properties. Aust. J. Chem. 2011, 64, 489–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Territory, A.C.O.T.N. Traditional Aboriginal Medicines in the Northern Territory of Australia; Conservation Commission of the Northern Territory of Australia: Darwin, Australia, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Roth, W.E. Superstition, magic, and medicine. North Qld. Ethnogr. Bull. 1903, 5, 1–42. [Google Scholar]

- Cleland, J.B.; Johnston, T.H. Aboriginal names and uses of plants in the Northern Flinders Ranges. T. Roy. Soc. South Aust. 1939, 63, 172–179. [Google Scholar]

- Warrier, P.K.; Nambiar, V.P.K.; Ramankutty, C.; Nair, R.V. Indian Medicinal Plants: A Compendium of 500 Species; Orient Longman: Chennai, India, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Pattanayak, S.P.; Sunita, P. Wound healing, anti-microbial and antioxidant potential of Dendrophthoe falcata (L.f) Ettingsh. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2008, 120, 241–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chuakul, W.; Soonthornchareonnon, N.; Ruangsomboon, O. Dendrophthoe Mart. In Plant Resources of South-East Asia No 12(3): Medicinal and Poisonous Plants 3; Lemmens, R.H.M.J., Bunyapraphatsara, N., Eds.; Backhuys: Leiden, The Netherlands, 2003; pp. 157–159. [Google Scholar]

- Arung, E.T.; Kusuma, I.W.; Christy, E.O.; Shimizu, K.; Kondo, R. Evaluation of medicinal plants from Central Kalimantan for antimelanogenesis. J. Nat. Med. 2009, 63, 473–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watt, J.M.; Breyer-Brandwijk, M.G. The Medicinal and Poisonous Plants of Southern and Eastern Africa: Being an Account of Their Medicinal and Other Uses, Chemical Composition, Pharmacological Effects and Toxicology in Man and Animal; E. & S. Livingstone: Edinburgh, UK, 1962. [Google Scholar]

- Rahayu, S.S.B. Loranthus globosus Roxb. In Plant Resources of South-East Asia No 12(3): Medicinal and Poisonous Plants 3; Lemmens, R.H.M.J., Bunyapraphatsara, N., Eds.; Backhuys: Leiden, The Netherlands, 2003; pp. 284–285. [Google Scholar]

- Sadik, G.; Islam, R.; Rahman, M.M.; Khondkar, P.; Rashid, M.A.; Sarker, S.D. Antimicrobial and cytotoxic constituents of Loranthus globosus. Fitoterapia 2003, 74, 308–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, R.; Alam, A.H.M.K.; Rahman, B.M.; Salam, K.A.; Hossain, A.; Baki, A.; Sadik, G. Toxicological studies of two compounds isolated from Loranthus globosus Roxb. Pak. J. Biol. Sci. 2007, 10, 2073–2077. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Rahayu, S.S.B. Macrosolen Blume. In Plant Resources of South-East Asia No 12(3): Medicinal and Poisonous Plants 3; Lemmens, R.H.M.J., Bunyapraphatsara, N., Eds.; Backhuys: Leiden, The Netherlands, 2003; pp. 284–285. [Google Scholar]

- Cardenas, L.B. Scurrula L. In Plant resources of South-East Asia No 12(3): Medicinal and Poisonous Plants 3; Lemmens, R.H.M.J., Bunyapraphatsara, N., Eds.; Backhuys: Leiden, The Netherlands, 2003; pp. 370–373. [Google Scholar]

- Ikawati, M.; Wibowo, A.E.; Octa, N.S.; Adelina, R. The Utilization of Parasite as Anticancer Agent; Faculty of Pharmacy-Gadjah Mada University: Yogyakarta, Indonesia, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Djumidi, H. Inventaris Tanaman Obat Indonesia; Badan Litbangkes Depkes RI: Jakarta, Indonesia, 1997; Volume IV. [Google Scholar]

- Ohashi, K.; Winarno, H.; Mukai, M.; Shibuya, H. Preparation and cancer cell invasion inhibitory effects of C16-alkynic fatty acids. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 2003, 51, 463–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ohashi, K.; Winarno, H.; Mukai, M.; Inoue, M.; Prana, M.S.; Simanjuntak, P.; Shibuya, H. Indonesian medicinal plants. XXV. Cancer cell invasion inhibitory effects of chemical constituents in the parasitic plant Scurrula atropurpurea (loranthaceae). Chem. Pharm. Bull. 2003, 51, 343–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lohezic-Le Devehat, F.; Bakhtiar, A.; Bezivin, C.; Amoros, M.; Boustie, J. Antiviral and cytotoxic activities of some Indonesian plants. Fitoterapia 2002, 73, 400–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Y.J.; Chen, Y.Z.; Chen, B.H.; Chen, J.H.; Lin, Z.X.; Fan, Y.L. Study on cytotoxic activities on human leukemia cell line HL-60 by flavonoids extracts of Scurrula parasitica from four different host trees. Zhongguo Zhong Yao Za Zhi 2008, 33, 427–432. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.; Xiao, Y.; Xu, J.; Wu, Y. Uses of Extracts of Loranthaceae Plants as NF-κB Inhibitor for Treating Diseases Associated with Abnormal Activation of NF-κB. China Patent 101548995A, 7 October 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Sohn, S.H.; Lee, H.; Nam, J.-y.; Kim, S.H.; Jung, H.J.; Kim, Y.; Shin, M.; Hong, M.; Bae, H. Screening of herbal medicines for the recovery of cisplatin-induced nephrotoxicity. Environ. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2009, 28, 206–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, B.H.; Lai, J.J.; Zheng, Q.; Li, J.; Xiao, Y.J. Effects of different extraction solvents on the antioxidant activities of leaves extracts of Scurrula parasitica. Fujian Shifan Daxue Xuebao Ziran Kexueban 2010, 26, 86–90. [Google Scholar]

- Xiao, Y.; Fan, Y.; Chen, B.; Zhang, Q.; Zeng, H. Polysaccharides from Scurrula parasitica L. inhibit sarcoma S180 growth in mice. Zhongguo Zhong Yao Za Zhi 2010, 35, 381–384. [Google Scholar]

- Roh, C.; Jung, U. Screening of crude plant extracts with anti-obesity activity. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2012, 13, 1710–1719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, D.Z.H.; Abdul, K.H.; Ling, S.K. Bioassay-guided isolation of neuroprotective compounds from Loranthus parasiticus against H2O2-induced oxidative damage in NG108-15 cells. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2012, 139, 256–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zuo, G.Y.; Zhang, X.J.; Yang, C.X.; Han, J.; Wang, G.C.; Bian, Z.Q. Evaluation of traditional Chinese medicinal plants for anti-MRSA activity with reference to the treatment record of infectious diseases. Molecules 2012, 17, 2955–2967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amabeoku, G.J.; Leng, M.J.; Syce, J.A. Antimicrobial and anticonvulsant activities of Viscum capense. J. Ethnopharmacol. 1998, 61, 237–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tibe, O.; Pernthaner, A.; Sutherland, I.; Lesperance, L.; Harding, D.R.K. Condensed tannins from Botswanan forage plants are effective priming agents of γδ T cells in ruminants. Vet. Immunol. Immunopathol. 2012, 146, 237–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nurdin, H.; Dachriyanus; Nordin, M. Profil fitokimia dan aktifitas antiacetylcholinesterase dari daun Tabat barito (Ficus deltoidea Jack). J. Ris. Kim. 2009, 2, 169–173. [Google Scholar]

- Adam, H.; Ismail, A.; Khamis, S.; Mokhtar, M.H.M.; Hamid, M. Antihyperglycemic activity of F. deltoidea ethanolic extract in normal rats. Sains Malays. 2011, 40, 489–495. [Google Scholar]

- Rojo, J.P.; Pitargue, F.C.; Sosef, M.S.M. Ficus L. In Plant Resources of South-East Asia No 12(1): Medicinal and Poisonous Plants 1; de Padua, L.S., Bunyapraphatsara, N., Lemmens, R.H.M.J., Eds.; Backhuys: Leiden, The Netherlands, 1999; pp. 277–289. [Google Scholar]

- Fazliana, M.S.; Muhajir, H.; Hazilawati, H.; Shafii, K.; Mazleha, M. Effects of Ficus deltoidea aqueous extract on hematological and biochemical parameters in rats. Med. J. Malays. 2008, 63, 103–104. [Google Scholar]

- Sulaiman, M.R.; Hussain, M.K.; Zakaria, Z.A.; Somchit, M.N.; Moin, S.; Mohamad, A.S.; Israf, D.A. Evaluation of the antinociceptive activity of Ficus deltoidea aqueous extract. Fitoterapia 2008, 79, 557–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zunoliza, A.; Khalid, H.; Zhari, I.; Rasadah, M.A.; Mazura, P.; Fadzureena, J.; Rohana, S. Evaluation of extracts of leaf of three Ficus deltoidea varieties for antioxidant activities and secondary metabolites. Pharmacogn. Res. 2009, 1, 216–223. [Google Scholar]

- Ilyanie, Y.; Wong, T.W.; Choo, C.Y. Evaluation of hypoglycemic activity and toxicity profiles of the leaves of Ficus deltoidea in rodents. J. Complement. Integr. Med. 2011, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oh, M.J.; Hamid Mariani, A.; Ngadiran, S.; Seo, Y.K.; Sarmidi Mohamad, R.; Park Chang, S. Ficus deltoidea (Mas cotek) extract exerted anti-melanogenic activity by preventing tyrosinase activity in vitro and by suppressing tyrosinase gene expression in B16F1 melanoma cells. Arch Dermatol. Res. 2011, 303, 161–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdsamah, O.; Zaidi, N.T.A.; Sule, A.B. Antimicrobial activity of Ficus deltoidea Jack (Mas Cotek). Pak. J. Pharm. Sci. 2012, 25, 675–678. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Zakaria, Z.A.; Hussain, M.K.; Mohamad, A.S.; Abdullah, F.C.; Sulaiman, M.R. Anti-inflammatory activity of the aqueous extract of Ficus deltoidea. Biol. Res. Nurs. 2012, 14, 90–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhatt, D.D. Natural History and Economic Botany of Nepal; Dept. of Information, His Majesty’s Govt. of Nepal: Kathmandu, Nepal, 1970. [Google Scholar]

- Bajracharya, D.; Rana, S.J.B.; Shrestha, A.K. A general survey and biochemical analysis of fodder plants found in Nagarjun hill forest of Kathmandu valley. J. Nat. Hist. Mus. 1978, 2, 105–116. [Google Scholar]

- Rai, S.K.; Subedi, S.; Mishra, S. Utilization pattern of medicinal plants in Thumpakhar, Sindhupalchok, Nepal. Bot. Orient. 2004, 4, 75–78. [Google Scholar]

- Lan, Z. Oral Medicated Liquor Comprising Caulis et Folium Piperis, Radix Celastri Angulati and Ficus Lacor Buch-Ham with Effects of Eliminating Dampness Relieving Pain. China Patent 1814035, 9 August 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Oyen, L.P.A. Ficus natalensis Hochst. In PROTA (Plant Resources of Tropical Africa/Ressources Végétales de l’Afrique Tropicale); Brink, M., Achigan-Dako, E.G., Eds.; PROTA: Wageningen, The Netherlands, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Nakano, D.; Ishitsuka, K.; Hatsuse, T.; Tsuchihashi, R.; Okawa, M.; Okabe, H.; Tamura, K.; Kinjo, J. Screening of promising chemotherapeutic candidates against human adult T-cell leukemia/lymphoma from plants: Active principles from Physalis pruinosa and structure-activity relationships with withanolides. J. Nat. Med. 2011, 65, 559–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ragasa, C.Y.; Juan, E.; Rideout, J.A. A triterpene from Ficus pumila. J. Asian Nat. Prod. Res. 1999, 1, 269–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panyaphu, K.; On, T.V.; Sirisa-ard, P.; Srisa-nga, P.; ChansaKaow, S.; Nathakarnkitkul, S. Medicinal plants of the Mien (Yao) in Northern Thailand and their potential value in the primary healthcare of postpartum women. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2011, 135, 226–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chua, S. Kajian Etnobotani ke Atas Komuniti Temuan di Semenyih, Selangor. Bachelor’s Thesis, Universiti Malaya, Kuala Lumpur, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Nardiah, R.J.; Nazlina, I.; Mohd, R.A.R.; Siti, N.A.Z.; Ling, C.Y.; Shariffah, M.S.A.; Farina, A.H.; Yaacob, W.A.; Ahmad, I.B.; Din, L.B. A survey on phytochemical and bioactivity of plant extracts from Malaysian forest reserves. J. Med. Plants Res. 2010, 4, 203–210. [Google Scholar]

- Jalal, J.S.; Kumar, P.; Pangtey, Y.P.S. Ethnomedicinal orchids of Uttarakhand, western Himalaya. Ethnobot. Leafl. 2008, 12, 1227–1230. [Google Scholar]

- Sulistiarini, D. Acriopsis javanica Reinw. ex Blume. In Plant Resources of South-East Asia No 12(3): Medicinal and Poisonous Plants 3; Lemmens, R.H.M.J., Bunyapraphatsara, N., Eds.; Backhuys: Leiden, The Netherlands, 2003; pp. 33–34. [Google Scholar]

- Satish, M.N.; Abhay, P.S.; Chen-Yue, L.; Chao-Lin, K.; Hsin-Sheng, T. Studies on tissue culture of Chinese medicinal plant resources in Taiwan and their sustainable utilization. Bot. Bull. Acad. Sin. 2003, 44. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, J.M.; Lin, C.C.; Chiu, H.F.; Yang, J.J.; Lee, S.G. Evaluation of the anti-inflammatory and liver-protective effects of Anoectochilus formosanus, Ganoderma lucidum and Gynostemma pentaphyllum in Rats. Am. J. Chin. Med. 1993, 21, 59–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Du, X.M.; Sun, N.Y.; Tamura, T.; Mohri, A.; Sugiura, M.; Yoshizawa, T.; Irino, N.; Hayashi, J.; Shoyama, Y. Higher yielding isolation of kinsenoside in Anoectochilus and its anti-hyperliposis Effect. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 2001, 24, 65–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shih, C.C.; Wu, Y.W.; Lin, W.C. Ameliorative effects of Anoectochilus formosanus extract on osteopenia in ovariectomized rats. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2001, 77, 233–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.Y.; Kuo, Y.H.; Chang, H.N.; Kang, P.L.; Tsay, H.S.; Lin, K.F.; Yang, N.S.; Shyur, L.F. Profiling and characterization antioxidant activities in Anoectochilus formosanus Hayata. J. Agric. Food. Chem. 2002, 50, 1859–1865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shih, C.C.; Wu, Y.W.; Lin, W.C. Antihyperglycaemic and anti-oxidant properties of Anoectochilus Formosanus in diabetic rats. Clin. Exp. Pharmacol. Physiol. 2002, 29, 684–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shyur, L.F.; Chen, C.H.; Lo, C.P.; Wang, S.Y.; Kang, P.L.; Sun, S.J.; Chang, C.A.; Tzeng, C.M.; Yang, N.S. Induction of apoptosis in MCF-7 human breast cancer cells by phytochemicals from Anoectochilus formosanus. J. Biomed. Sci. 2004, 11, 928–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shih, C.C.; Wu, Y.W.; Hsieh, C.C.; Lin, W.C. Effect of Anoectochilus formosanus on fibrosis and regeneration of the liver in rats. Clin. Exp. Pharmacol. Physiol. 2004, 31, 620–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shih, C.C.; Wu, Y.W.; Lin, W.C. Aqueous extract of Anoectochilus formosanus attenuate hepatic fibrosis induced by carbon tetrachloride in rats. Phytomedicine 2005, 12, 453–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsiao, H.B.; Wu, J.B.; Lin, H.; Lin, W.C. Kinsenoside isolated from Anoectochilus formosanus suppresses LPS-stimulated inflammatory reactions in macrophages and endotoxin shock in mice. Shock 2011, 35, 184–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hsieh, W.T.; Tsai, C.T.; Wu, J.B.; Hsiao, H.B.; Yang, L.C.; Lin, W.C. Kinsenoside, a high yielding constituent from Anoectochilus formosanus, inhibits carbon tetrachloride induced Kupffer cells mediated liver damage. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2011, 135, 440–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, W.C.; Hsieh, C.C.; Lu, T.J.; Tsay, H.S.; Yang, L.C.; Lin, C.C.; Wang, C.H. Anoectochilus spp. Polysaccharide Extracts for Stimulating Growth of Advantageous Bacteria, Stimuating Release of Granulocyte Colony-Stimulating Factor, Modulating T Helper Cell Type I, and/or Modulating T Helper Cell Type II and Uses of the Sa. U.S. Patent 20110082103, 7 April 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Ye, S.; Shao, Q.; Zhang, A. Anoectochilus roxburghii: A review of its phytochemistry, pharmacology, and clinical applications. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2017, 209, 184–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Cai, J.; Ruan, H.; Pi, H.; Wu, J. Antihyperglycemic activity of kinsenoside, a high yielding constituent from Anoectochilus roxburghii in streptozotocin diabetic rats. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2007, 114, 141–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, S.C.; Yu, J.; Zhang, X.H.; Cheng, M.Z.; Yang, L.W.; Xu, J.Y. Antihyperglycemic and antioxidant activity of water extract from Anoectochilus roxburghii in experimental diabetes. Exp. Toxicol. Pathol. 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, B.; He, S.; Pan, Y.J. New dihydrodibenzoxepins from Bulbophyllum kwangtungense. Planta Med. 2006, 72, 1244–1247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Xu, J.; Yut, H.; Qin, C.W.; Zhangt, Y.; Liu, Y.; Wang, J. Bulbophyllum Odoratissimum 3,7- Dihydroxy- 2,4,6-trimethoxyphenanthrene. J. Korean Chem. Soc 2007, 51, 352. [Google Scholar]

- Yao, X.; Wang, N.; Bei, Z.; Liu, D. Bulbophyllispiradienone Compound and its Derivatives as Antitumor Agent and Inhibiting NO Release from Macrophage. China Patent 1594311, 16 March 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Yao, X.; Wang, N.; Bei, Z.; Liu, D.; Zhang, J. New Dibenzyl Compounds as Antitumor Agent and Inhibiting Macrophage from Releasing NO. China Patent 1594309, 16 March 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.; Xu, J.; Yu, H.; Chen, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, L.; Liu, Y.; Wang, J. Cytotoxic phenolics from Bulbophyllum odoratissimum. Food Chem. 2007, 107, 169–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Yu, H.; Qing, C.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Chen, Y. Two new biphenanthrenes with cytotoxic activity from Bulbophyllum odoratissimum. Fitoterapia 2009, 80, 381–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shimizu, M.; Shogawa, H.; Hayashi, T.; Arisawa, M.; Suzuki, S.; Yoshizaki, M.; Morita, N.; Ferro, E.; Basualdo, I.; Berganza, L.H. Chemical and pharmaceutical studies on medicinal plants in Paraguay. Anti-inflammatory constituents of topically applied crude drugs. III. Constituents and anti-inflammatory effect of Paraguayan crude drug “Tamanda cuna” (Catasetum barbatum Lindle). Chem. Pharm. Bull. 1988, 36, 4447–4452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huyen, D.D. Cymbidium aloifolium (L.) Sw. In Plant Resources of South-East Asia No 12(3): Medicinal and Poisonous Plants 3; Lemmens, R.H.M.J., Bunyapraphatsara, N., Eds.; Backhuys: Leiden, The Netherlands, 2003; pp. 147–148. [Google Scholar]

- Howlader, M.A.; Alam, M.; Ahmed, K.T.; Khatun, F.; Apu, A.S. Antinociceptive and anti-inflammatory activity of the ethanolic extract of Cymbidium aloifolium (L.). Pak. J. Biol. Sci. 2011, 14, 909–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Webb, L.J. Queensland. Proc. Roy. Soc. 1959, 71, 103. [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe, K.; Tanaka, R.; Sakurai, H.; Iguchi, K.; Yamada, Y.; Hsu, C.S.; Sakuma, C.; Kikuchi, H.; Shibayama, H.; Kawai, T. Structure of cymbidine A, a monomeric peptidoglycan-related compound with hypotensive and diuretic activities, isolated from a higher plant, Cymbidium goeringii (Orchidaceae). Chem. Pharm. Bull. 2007, 55, 780–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Won, J.H.; Kim, J.Y.; Yun, K.J.; Lee, J.H.; Back, N.I.; Chung, H.G.; Chung, S.A.; Jeong, T.S.; Choi, M.S.; Lee, K.T. Gigantol isolated from the whole plants of Cymbidium goeringii inhibits the LPS-induced iNOS and COX-2 expression via NF-κB inactivation in RAW 264.7 macrophages cells. Planta Med. 2006, 72, 1181–1187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkateswarlu, S.; Raju, M.S.; Subbaraju, G.V. Synthesis and biological activity of isoamoenylin, a metabolite of Dendrobium amoenum. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 2002, 66, 2236–2238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Yang, L.; Wang, Z.; Xu, L. Simultaneous determination of phenols (Bibenzyl, phenanthrene, and fluorene) in Dendrobium species by high-performance liquid chromatography with diode array detection. J. Chromatogr. A 2006, 1104, 230–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Han, H.; Nakamura, N.; Hattori, M.; Wang, Z.; Xu, L. Bio-guided isolation of antioxidants from the stems of Dendrobium aurantiacum var. denneanum. Phytother. Res. 2007, 21, 696–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.S.; Xu, J.H.; Chen, L.Z.; Sun, J.J. Studies on anti-hyperglycemic effect and its mechanism of Dendrobium candidum. Zhongguo Zhong Yao Za Zhi 2004, 29, 160–163. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, J.; Chen, L.; Li, L. Effects of white dendrobium (Denbrobium candidum) and American ginseng (Panax quinquefolium) on nourishing the Yin and promoting glandular secretion in mice and rabbits. Zhongcaoyao 1995, 26, 79–80. [Google Scholar]

- He, T.G.; Yang, L.T.; Li, Y.R.; Wan, C.Q. Antioxidant activity of crude and purified polysaccharide from suspension-cultured protocorms of Dendrobium candidum in vitro. Zhongchengyao 2007, 29, 1265–1269. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Wang, C.L.; Wang, Y.J.; Guo, S.X.; Yang, J.S.; Chen, X.M.; Xiao, P.G. Three New Bibenzyl Derivatives from Dendrobium candidum. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 2009, 57, 218–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Wang, C.L.; Wang, Y.J.; Wang, F.F.; Guo, S.X.; Yang, J.S.; Xiao, P.G. Four new bibenzyl derivatives from Dendrobium candidum. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 2009, 57, 997–999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, H.; Zhang, X.; Tu, F.; Yao, X. Chemical components of Dendrobium candidum. Zhongcaoyao 2009, 40, 1873–1876. [Google Scholar]

- Sulistiarini, D. Dendrobium crumenatum Sw. In Plant Resources of South-East Asia No 12(2): Medicinal and Poisonous Plants 2; van Valkenburg, J.L.C.H., Bunyapraphatsara, N., Eds.; Backhuys: Leiden, The Netherlands, 2001; p. 216. [Google Scholar]

- Mardisiswojo, S.; Rajakmangunsudarso, H. Cabe Puyang, Warisan Nenek Moyang; Balai Pustaka: Jakarta, Indonesia, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Sandrasagaran, U.M.; Ramanathan, S.; Subramnaniam, S.; Mansor, S.M.; Murugaiyah, V. Antimicrobial activity of Dendrobium crumenatum (Pigeon Orchid). Malays. J. Pharm. Sci. 2010, 1, 111–112. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.M.; Wang, H.Y.; Liu, G.Q. Erianin induces apoptosis in human leukemia HL-60 cells. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 2001, 22, 1018–1022. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, L.; Qin, L.H.; Bligh, S.W.; Bashall, A.; Zhang, C.F.; Zhang, M.; Wang, Z.T.; Xu, L.S. A new phenanthrene with a spirolactone from Dendrobium chrysanthum and its anti-inflammatory activities. Bioorganic Med. Chem. 2006, 14, 3496–3501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, C.; Wang, W.; Wang, Y.; Qin, G.; Zhao, W. Chemical constituents from Dendrobium densiflorum. Phytochemistry 2001, 57, 1255–1258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heyne, K. De Nuttige Planten Van Indonesie; N.V.Uitgeverij W. van Hoeve: ‘s-Gravenhage, The Netherlands, 1950. [Google Scholar]

- Bi, Z.M.; Wang, Z.T.; Xu, L.S.; Xu, G.J. Studies on the chemical constituents of Dendrobium fimbriatum. Yao Xue Xue Bao 2003, 38, 526–529. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, A.; Fan, Y. In vitro antioxidant of a water-soluble polysaccharide from Dendrobium fimbriatum Hook.var.oculatum Hook. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2011, 12, 4068–4079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ho, C.K.; Chen, C.C. Moscatilin from the orchid Dendrobrium loddigesii is a potential anticancer agent. Cancer Investig. 2003, 21, 729–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- LI, M.F.; Hirata, Y.; Xu, G.J.; Niwa, M.; Wu, H.M. Studies on the chemical constituents of Dendrobium loddigesii rolfe. Yao Xue Xue Bao 1991, 26, 307–310. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, C.C.; Wu, L.G.; Ko, F.N.; Teng, C.M. Antiplatelet aggregation principles of Dendrobium loddigesii. J. Nat. Prod. 1994, 57, 1271–1274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ito, M.; Matsuzaki, K.; Wang, J.; Daikonya, A.; Wang, N.L.; Yao, X.S.; Kitanaka, S. New Phenanthrenes and Stilbenes from Dendrobium loddigesii. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 2010, 58, 628–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, K.K.; Chen, A.L. The alkaloid of Chin-Shih-Hu. J. Biol. Chem. 1935, 653–658. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, T.H.; Chang, S.J.; Chen, C.C.; Wang, J.P.; Tsao, L.T. Two phenanthraquinones from Dendrobium moniliforme. J. Nat. Prod. 2001, 64, 1084–1086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.L.; He, G.Q.; Zhang, M.; Li, H.J. Hypoglycemic effect of the polysaccharide from Dendrobium moniliforme. Zhejiang Daxue Xuebao Lixueban 2003, 30, 693–696. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, S.; Wei, F.J.; Cai, Y.P.; Lin, Y. Anti-oxidation activity in vitro of polysaccharides of Dendrobium huoshanense and Dendrobium moniliforme. Agric. Sci. Technol. 2009, 10, 121–124. [Google Scholar]

- Malla, B.; Gauchan, D.P.; Chhetri, R.B. An ethnobotanical study of medicinal plants used by ethnic people in Parbat district of western Nepal. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2015, 165, 103–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Valkenburg, J.L.C.H.; Bunyaprapphatsara, N. Plant resources of South-East Asia 12 (2). Medicinal and poisonous plants 2; Back-huys Publisher: Leiden, The Netherlands, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Gutiérrez, R.M.P. Orchids: A review of uses in traditional medicine, its phytochemistry and pharmacology. J. Med. Plants Res. 2010, 4, 592–638. [Google Scholar]

- Kong, J.M.; Goh, N.K.; Chia, L.S.; Chia, T.F. Recent advances in traditional plant drugs and orchids. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 2003, 24, 7–21. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Liu, Q.F.; Zhao, W. A new dedonbrine-type alkaloid from Dendrobium nobile. Chin. Chem. Lett. 2003, 14, 278–279. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, W.; Ye, Q.; Tan, X.; Jiang, H.; Li, X.; Chen, K.; Kinghorn, A.D. Three new sesquiterpene glycosides from Dendrobium nobile with immunomodulatory activity. J. Nat. Prod. 2001, 64, 1196–1200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, Q.; Qin, G.; Zhao, W. Immunomodulatory sesquiterpene glycosides from Dendrobium nobile. Phytochemistry 2002, 61, 885–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Xu, J.K.; Wang, J.; Wang, N.L.; Kurihara, H.; Kitanaka, S.; Yao, X.S. Bioactive bibenzyl derivatives and fluorenones from Dendrobium nobile. J. Nat. Prod. 2006, 70, 24–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]