Bioactive Plant Metabolites in the Management of Non-Communicable Metabolic Diseases: Looking at Opportunities beyond the Horizon

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Successes and Failures of Current Strategies for Management of Non-Communicable Diseases: Lipid Lowering Therapy as an Example

2.1. Statin Intolerance

2.2. Coenzyme Q10

2.3. Vitamin D Supplementation

2.4. Alternatives to Statins

2.5. PCSK9 Inhibition: The Future?

| Agent/Dose | Mechanism of Action | Effects on Lipid Profile | Common Side Effects | Key Clinical Data |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Niacin | Inhibits triglyceride (TG) synthesis and favorably impacts apoliprotein B containing lipoproteins | Two gram dose can lower low density liproprotein (LDL) by 15%, increase HDL by up to 25%, and lower TG by up to 30% | Flushing, gastrointestinal effects, pruritis, and rash | Randomized controlled trials of niacin including AIM-HIGH and HPS2-THRIVE have demonstrated no benefit in cardiovascular events despite significant increases in HDL levels [27,28]. |

| Fibrates | Reduces hepatic TG production, enhances LDL uptake by the LDL receptor, and stimulates lipoprotein lipolysis | Primarily lowers TG and can lower LDL by ~10% | Gastrointestinal side effects including nausea and diarrhea. Can raise liver enzymes and cause gallstone formation. Drug-drug interactions with statins and warfarin are important to watch | Meta-analyses have demonstrated a reduction in coronary events including non-fatal MI. However, no benefit in all-cause mortality was seen [27,28] |

| Bile acid sequestrants | Bind to bile acids in the intestine and prevent recirculation of cholesterol | Depending on dosage, can decrease LDL 15%–30% | Gastrointestinal side effects including constipation, very rare reports of myalgias | May have beneficial impact on coronary atherosclerosis and may lower HbA1c [27]. |

| Plant sterol esters | Interfere with dietary and biliary cholesterol absorption from the intestines | 2–3 grams per day may reduce LDL cholesterol by 8%–15% (typically 8%–9%) and TG by 6%–9% | Well tolerated, uncertain impact on vitamin and nutrient absorption Uncertain impact on cancer risk | Limited data on markers of atherosclerosis and no large randomized cardiovascular outcomes data [29]. |

| Red rice yeast | Functionally a low dose statin. Contains monacolin—the active ingredient in lovastatin is monacolin K | Reductions in LDL vary between 19% and 30% Minimal impact on HDL and modest effect on TG reduction | Generally well tolerated—even in statin intolerant patients but there have been reported myalgias similar to statins with one case of rhabdomyolysis reported. | Several small randomized controlled trials. Recent meta-analysis of 13 trials confirms LDL reduction, modest TG reductions and no impact on HDL levels [30]. No significant creatinine kinase level changes were noted. |

| Ezetimibe | Decreases cholesterol absorption in the small intestine | As an alternative to statin therapy can lower LDL cholesterol ~15%–20%. Minimal impact on HDL as monotherapy. With statin use can lower LDL by ~25%–60% with moderate reduction in TG. Can be used with fibrates to achieve ~20% lowering of LDL, and moderate increase in HDL, and decrease in TG | Generally well tolerated. Most common side effects: diarrhea (2.0%–2.5%), myalgias with statin use (3%), transaminitis with statin use (1.3%) | Clinical efficacy and safety for LDL lowering have been established in multiple studies. IMPROVE-IT randomized 18,144 recent acute coronary syndrome patients to simvastatin + ezetimibe vs. simvastatin + placebo [31]. There was a median follow up of six years and the primary composite endpoint was death from CVD, a major coronary event (nonfatal myocardial infarction (MI), documented unstable angina requiring hospital admission, or coronary revascularization occurring at least 30 days after randomization), or nonfatal stroke. The trial demonstrated an absolute risk reduction of 2.0% (p = 0.016) in the primary endpoint, driven by a significant reduction in non-fatal MI and stroke. |

3. A Brief Survey of Foods Rich in Bioactive Plant Metabolites

3.1. Phytosterols

3.2. Flavonoids

3.3. Lignans

4. Select Examples of Bioactive Plant Metabolites with Potentials for Management of Non-Communicable Diseases

4.1. Resistant Starch

4.2. Cyclic Dipeptides

4.3. Cyclo (His-Pro), Food Intake, and Body Weight

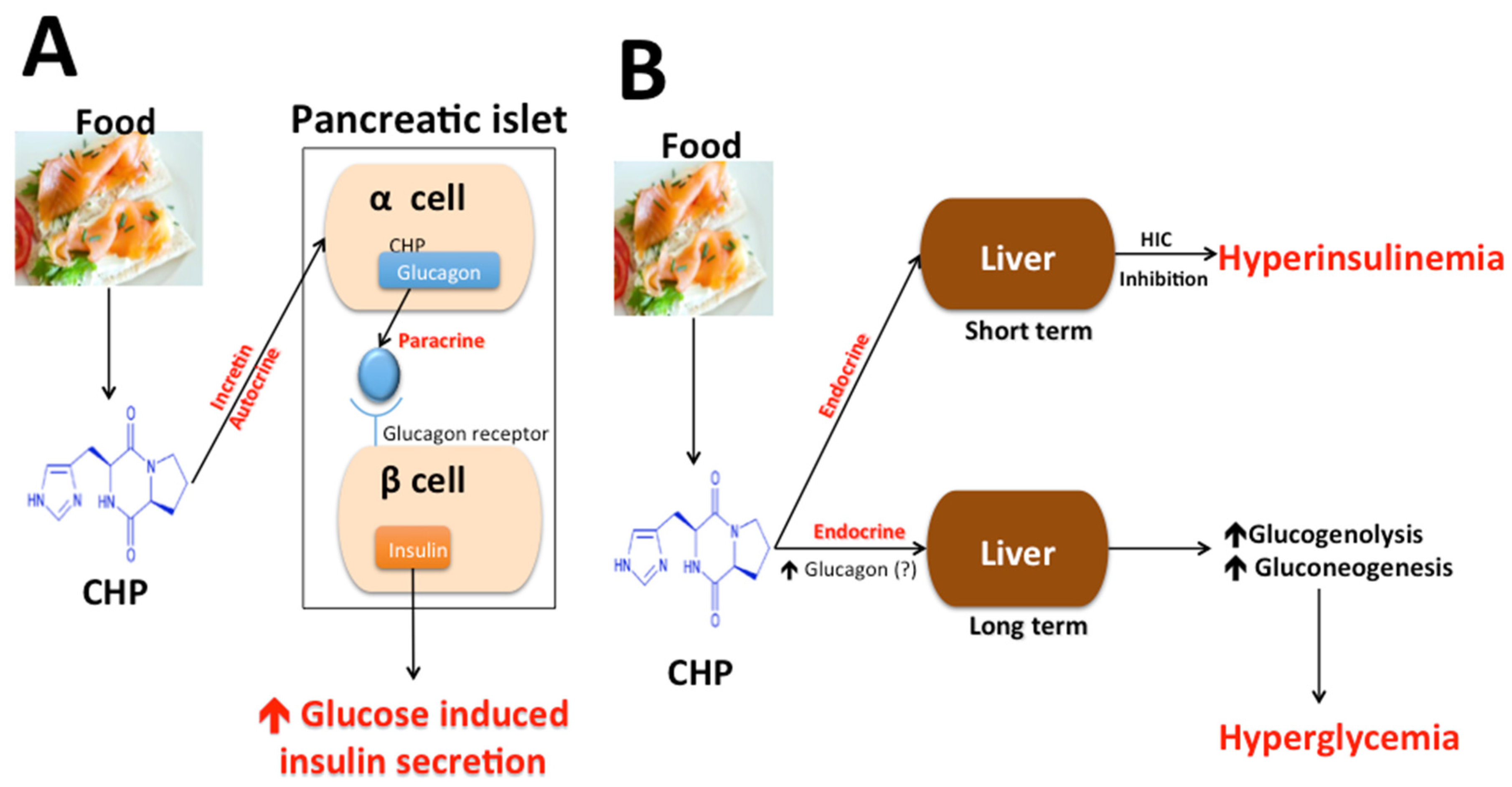

4.4. Cyclo (His-Pro), Insulin Secretion, Glucose Metabolism, and Diabetes

| Food | Cyclo (His-Pro) Concentration | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Noodle | 18.8 ng/g | [136] |

| Potted Meat | 40.9 ng/g | [136] |

| Nondairy creamer | 30.0 ng/g | [136] |

| Hot Dog | 18.1 ng/g | [136] |

| Ham | 32.5 ng/g | [136] |

| Egg | 5.7 ng/g | [136] |

| White Bread | 21.8 ng/g | [136] |

| Tuna | 510.4 ng/g | [136] |

| Fish Sauce | 1291.8 ng/g | [136] |

| Dried Shrimp | 1630.8 ng/g | [136] |

| Fresh Cow Milk | 1.8 ng/g | [135] |

| Pasteurized Cow Milk | 2.5 ng/g | [135] |

| Yogurt | 4.2 ng/g | [135] |

| Spent Brewer’s Yeast hydrolysate | 674,000 ng/g | [157] |

| Nutritional Supplements | ||

| (1) Ensure plus 1 | 300 ng/mL | [137] |

| (2) Ensure HN 1 | 601 ng/mL | |

| (3) Ensure 1 | 454 ng/mL | |

| (4) Pulmocare 2 | 824 ng/mL | |

| (5) Enrich 1 | 323 ng/mL | |

| (6) TwoCal HN 2 | 4763 ng/mL | |

| (7) Jevity 1 | 4467 ng/mL | |

| (8) Osmolite 1 | 123 ng/mL | |

| (9) Tolerex 3 | ND | |

| (10) Travasorb Hepatic 4 | ND | |

| (11) Travasorb Renal 4 | ND |

4.5. Fruit Berries

4.6. Bioactive Berry Constituents

4.7. Berry Consumption and Non-Communicable Disease

4.8. Cardiovascular Diseases

4.9. Hypertension

4.10. Diabetes Mellitus

5. Future Directions

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Aldridge, S.; Parascadola, J.; Sturchio, J.L.; American Chemical Society; Royal Society of Chemistry (Great Britain). The Discovery and Development of Penicillin 1928-1945: The Alexander Fleming Laboratory Museum, London, UK, November 19, 1999: An International Historic Chemical Landmark; American Chemical Society: Washington, DC, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Stern, M.N.; Markel, H. The history of vaccines and immunization: Familiar patterns, new challenges. Health Aff. 2005, 24, 611–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bishai, D.; Nalubola, R. The history of food fortification in the United States: Its relevance for current fortification efforts in developing countries. Econ. Dev. Cult. Chang. 2002, 51, 37–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization (WHO). Projections of Mortality and Burden of Disease, 2004–2030. Available online: http://www.who.int/healthinfo/global_burden_disease/projections2004/en/ (accesses on 13 September 2015).

- King, H.; Aubert, R.E.; Herman, W.H. Global Burden of Diabetes, 1995–2025 Prevalence, numerical estimates and projections. Diabetes Care 1998, 21, 1414–1431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Cesare, M.; Khang, Y.-H.; Asaria, P.; Blakely, T.; Cowan, M.J.; Farzadfar, F.; Guerrero, R.; Ikeda, N.; Kyobutungi, C.; Msyamboza, K.P.; et al. Inequalities in non-communicable diseases and effective responses. Lancet 2013, 381, 585–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mintz, S.W.; Du Bois, C.M. The Anthropology of Food and Eating. Annu. Rev. Anthropol. 2002, 31, 99–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, F.B. Globalization of food patterns and cardiovascular disease risk. Circulation 2008, 118, 1913–1914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, F.B. Globalization of Diabetes. The role of diet, lifestyle, and genes. Diabetes Care 2011, 34, 1249–1257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Torun, B.; Stein, A.D.; Schroeder, D.; Grajeda, R.; Conlisk, A.; Rodriguez, M.; Mendez, H.; Martorell, R. Rural-to-urban migration and cardiovascular disease risk factors in young Guatemalan adults. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2002, 31, 218–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holmboe-Ottesen, G.; Margareta Wandel, M. Changes in dietary habits after migration and consequences for health: A focus on South Asians in Europe. Food Nutr. Res. 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hancox, R.J.; Milne, B.J.; Poulton, R. Association between child and adolescent television viewing and adult health: A longitudinal birth cohort study. Lancet 2004, 364, 257–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Douglas, M.J.; Watkins, S.J.; Gorman, D.R.; Higgins, M. Are cars the new tobacco? J. Public Health 2011, 33, 160–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stone, N.J.; Robinson, J.G.; Lichtenstein, A.H.; Bairey Merz, C.N.; Blum, C.B.; Eckel, R.H.; Goldberg, A.C.; Gordon, D.; Levy, D.; Lloyd-Jones, D.M.; et al. 2013 ACC/AHA guideline on the treatment of blood cholesterol to reduce atherosclerotic cardiovascular risk in adults: A report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2014, 63, 2889–2934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tran, J.N.; Caglar, T.; Stockl, K.M.; Lew, H.C.; Solow, B.K.; Chan, P.S. Impact of the New ACC/AHA Guidelines on the Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in a Managed Care Setting. Am. Health Drug Benefits 2014, 7, 430–443. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Bruckert, E.; Hayem, G.; Dejager, S.; Yau, C.; Begaud, B. Mild to moderate muscular symptoms with high-dosage statin therapy in hyperlipidemic patients—The PRIMO study. Cardiovasc. Drugs Ther. 2005, 19, 403–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilmot, K.A.; Khan, A.; Krishnan, S.; Eapen, D.J.; Sperling, L. Statins in the elderly: A patient-focused approach. Clin. Cardiol. 2015, 38, 56–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vandenberg, B.F.; Robinson, J. Management of the patient with statin intolerance. Curr. Atheroscler. Rep. 2010, 12, 48–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marcoff, L.; Thompson, P.D. The role of coenzyme Q10 in statin-associated myopathy: A systematic review. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2007, 49, 2231–2237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Littlefield, N.; Beckstrand, R.L.; Luthy, K.E. Statins’ effect on plasma levels of Coenzyme Q10 and improvement in myopathy with supplementation. J. Am. Assoc. Nurs. Pract. 2014, 26, 85–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morioka, T.Y.; Lee, A.J.; Bertisch, S.; Buettne, R.C. Vitamin D status modifies the association between statin use and musculoskeletal pain: A population based study. Atherosclerosis 2015, 238, 77–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khayznikov, M.; Hemachrandra, K.; Pandit, R.; Kumar, A.; Wang, P.; Glueck, C.J. Statin Intolerance Because of Myalgia, Myositis, Myopathy, or Myonecrosis Can in Most Cases be Safely Resolved by Vitamin D Supplementation. N. Am. J. Med. Sci. 2015, 7, 86–93. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Shimada, Y.J.; Cannon, C.P. PCSK9 (Proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9) inhibitors: Past, present, and the future. Eur. Heart J. 2015, 36, 2415–2424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lambert, G.; Sjouke, B.; Choque, B.; Kastelein, J.J.; Hovingh, G.K. The PCSK9 decade. J. Lipid Res. 2012, 53, 2515–2524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koren, M.J.; Scott, R.; Kim, J.B.; Knusel, B.; Liu, T.; Lei, L.; Bolognese, M.; Wasserman, S.M. Efficacy, safety, and tolerability of a monoclonal antibody to proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 as monotherapy in patients with hypercholesterolaemia (MENDEL): A randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 2 study. Lancet 2012, 380, 1995–2006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stroes, E.; Colquhoun, D.; Sullivan, D.; Civeira, F.; Rosenson, R.S.; Watts, G.F.; Bruckert, E.; Cho, L.; Dent, R.; Knusel, B.; et al. Anti-PCSK9 antibody effectively lowers cholesterol in patients with statin intolerance: The GAUSS-2 randomized, placebo-controlled phase 3 clinical trial of evolocumab. J. Am. Cardiol. 2014, 63, 2541–2548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Groot, L.J.; Beck-Peccoz, P.; Chrousos, G.; Dungan, K.; Grossman, A.; Hershman, J.M.; Koch, C.; McLachlan, R.; New, M.; Rebar, R.; et al. Endotext; MDText.com, Inc.: South Dartmouth, MA, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Keene, D.; Price, C.; Shun-Shin, M.J.; Francis, D.P. Effect on cardiovascular risk of high density lipoprotein targeted drug treatments niacin, fibrates, and CETP inhibitors: Meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials including 117,411 patients. BMJ 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gylling, H.; Simonen, P. Phytosterols, Phytostanols, and Lipoprotein Metabolism. Nutrients 2015, 7, 7965–7977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Jiang, L.; Jia, Z.; Xin, W.; Yang, S.; Yang, Q.; Wang, L. A meta-analysis of red yeast rice: An effective and relatively safe alternative approach for dyslipidemia. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e98611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cannon, C.P.; Blazing, M.A.; Giugliano, R.P.; McCagg, A.; White, J.A.; Theroux, P.; Darius, H.; Lewis, B.S.; Ophuis, T.O.; Jukema, J.W.; et al. Ezetimibe Added to Statin Therapy after Acute Coronary Syndromes. N. Engl. J. Med. 2015, 372, 2387–2397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hung, H.-C.; Joshipura, K.J.; Jiang, R.; Hu, F.B.; Hunter, D.; Smith-Warner, S.A.; Colditz, G.A.; Rosner, B.; Spiegelman, D.; Willett, W.C. Fruit and vegetable intake and risk of major chronic disease. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2004, 96, 1577–1584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joshipura, K.J.; Hu, F.B.; Manson, J.E.; Stampfer, M.J.; Rimm, E.B.; Speizer, F.E.; Colditz, G.; Ascherio, A.; Rosner, B.; Spiegelman, D.; et al. The effect of fruit and vegetable intake on risk for coronary heart disease. Ann. Intern. Med. 2001, 134, 1106–1114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, S.; Manson, J.E.; Lee, I.-M.; Cole, S.R.; Hennekens, C.H.; Willett, W.C.; Buring, J.E. Fruit and vegetable intake and risk of cardiovascular disease: The Women’s Health Study. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2000, 72, 922–928. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Liu, S.; Lee, I.-M.; Ajani, U. Intake of vegetables rich in carotenoids and risk of coronary heart disease in men: The Physicians’ Health Study. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2001, 30, 130–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bazzano, L.A.; He, J.; Ogden, L.G.; Loria, C.M.; Vupputuri, S.; Myers, L.; Whelton, P.K. Fruit and vegetable intake and risk of cardiovascular disease in US adults: The first National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey Epidemiologic Follow-up Study. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2002, 76, 93–99. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Jacobs, D.R.; Pereira, M.A.; Meyer, K.A.; Kushi, L.H. Fiber from whole grains, but not refined grains, is inversely associated with all-cause mortality in older women: The Iowa Women’s Health Study. J. Am. Coll. Nutr. 2000, 19, 326S–330S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eckel, R.H.; Jakicic, J.M.; Ard, J.D.; de Jesus, J.M.; Houston Miller, N.; Hubbard, V.S.; Lee, I.-M.; Lichenstein, A.H.; Loria, C.M.; Millen, B.E. A report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association task force on practice guidelines. Circulation 2014, 129, S76–S99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yusuf, S.; Hawken, S.; Ounpuu, S.; Dans, T.; Avezum, A.; Lanas, F.; McQueen, M.; Budaj, A.; Pais, P.; Varigos, J.; et al. Effect of potentially modifiable risk factors associated with myocardial infarction in 52 countries (the INTERHEART study): Case-control study. Lancet 2004, 364, 937–952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mouritsen, O.G.; Zuckermann, M.J. What’s so special about cholesterol? Lipids 2004, 39, 1101–1113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Halling, K.K.; Slotte, J.P. Membrane properties of plant sterols in phospholipid bilayers as determined by differential scanning calorimetry, resonance energy transfer and detergent-induced solubilization. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2004, 1664, 161–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Devaraj, S.; Jialal, I. The role of dietary supplementation with plant sterols and stanols in the prevention of cardiovascular disease. Nutr. Rev. 2006, 64, 348–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kris-Etherton, P.; Hecker, K.D.; Bonanome, A.; Coval, S.M.; Binkoski, A.E.; Hilpert, F.; Griel, A.E. Bioactive compounds in foods: Their role in the prevention of cardiovascular disease and cancer. Am. J. Med. 2002, 113, 71S–88S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katan, M.B.; Grundy, S.M.; Jones, P.; Law, M.; Miettinen, T.; Paoletti, R. Efficacy and safety of plant stanols and sterols in the management of blood cholesterol levels. Mayo Clin. Proc. 2003, 78, 965–978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nissinen, M.; Gylling, H.; Vuoristo, M.; Miettinen, T.A. Micellar distribution of cholesterol and phytosterols after duodenal plant stanol ester infusion. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 2002, 282, G1009–G1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Plat, J.; Mensink, R.P. Effects of plant stanol esters on LDL receptor protein expression and on LDL receptor and HMG-CoA reductase mRNA expression in mononuclear blood cells of healthy men and women. FASEB J. 2002, 16, 258–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, P.J.; Raeini-Sarjaz, M.; Ntanios, F.Y.; Vanstone, C.A.; Feng, J.Y.; Parsons, W.E. Modulation of plasma lipid levels and cholesterol kinetics by phytosterol versus phytostanol esters. J. Lipid Res. 2000, 41, 697–705. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- The Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 65 FR 54686 - Food Labeling: Health Claims; Plant Sterols/Stanol Esters and Coronary Heart Disease. Fed. Register 2000, 65, 54686–54739. [Google Scholar]

- The Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 75 FR 76526 - Food Labeling; Health Claim; Phytosterols and Risk of Coronary Heart Disease: Proposed Rule. Fed. Register 2010, 75, 76526–76571. [Google Scholar]

- Niinikosk, I.H.; Viikari, J.; Palmmu, T. Cholesterol-lowering effect and sensory properties of sitostanol ester margarine in normocholesterolemic adults. Scand. J. Nutr. 1997, 41, 9–12. [Google Scholar]

- Gylling, H.; Siimes, M.A.; Miettinen, T.A. Sitostanol ester margarine in dietary treatment of children with familial hypercholesterolemia. J. Lipid Res. 1995, 36, 1807–1812. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Gylling, H.; Miettinen, T.A. Serum cholesterol and cholesterol and lipoprotein metabolism in hypercholesterolaemic NIDDM patients before and during sitostanol ester-margarine treatment. Diabetologia 1994, 37, 773–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Volpe, R.; Niittynen, L.; Korpela, R.; Sirtori, C.; Bucci, A.; Fraone, N.; Pazzucconi, F. Effects of yoghurt enriched with plant sterols on serum lipids in patients with moderate hypercholesterolaemia. Br. J. Nutr. 2001, 86, 233–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hendriks, H.F.; Weststrate, J.A.; van Vliet, T.; Meijer, G.W. Spreads enriched with three different levels of vegetable oil sterols and the degree of cholesterol lowering in normocholesterolaemic and mildly hypercholesterolaemic subjects. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 1999, 53, 319–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pelletier, X.; Belbraouet, S.; Mirabel, D.; Mordret, F.; Perrin, J.L.; Pages, X.; Debry, G. A diet moderately enriched in phytosterols lowers plasma cholesterol concentrations in normocholesterolemic humans. Ann. Nutr. Metab. 1995, 39, 291–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hendriks, H.F.; Brink, E.J.; Meijer, G.W.; Princen, H.M.; Ntanios, F.Y. Safety of long-term consumption of plant sterol esters-enriched spread. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2003, 57, 681–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miettinen, T.A.; Puska, P.; Gylling, H.; Vanhanen, H.; Vartiainen, E. Reduction of serum cholesterol with sitostanol-ester margarine in a mildly hypercholesterolemic population. N. Engl. J. Med. 1995, 333, 1308–1312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grundy, S.M. Stanol, Esters as a Component of Maximal Dietary Therapy in the National Cholesterol Education Program Adult Treatment Panel III Report. Am. J. Cardiol. 2005, 96, 47–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, X.; Shen, T.; Lou, H. Dietary polyphenols and their biological significance. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2007, 8, 950–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rice-Evans, C.A.; Miller, N.J.; Paganga, G. Structure-antioxidant activity relationships of flavonoids and phenolic acids. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 1996, 20, 933–956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yochum, L.; Kushi, L.H.; Meyer, K.; Folsom, A.R. Dietary flavonoid intake and risk of cardiovascular disease in postmenopausal women. Am. J. Epidemiol. 1999, 149, 943–949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knekt, P.; Jarvinen, R.; Reunanen, A.; Maatela, J. Flavonoid intake and coronary mortality in Finland: A cohort study. Br. Med. J. 1996, 312, 478–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hertog, M.G.L.; Kromhout, D.; Aravanis, C.; Blackburn, H.; Buzina, R.; Fidanza, F.; Giampaoli, S.; Jansen, A.; Menotti, A.; Nedeljkovic, S.; et al. Flavonoid intake and long-term risk of coronary heart disease and cancer in the seven countries study. Arch. Intern. Med. 1995, 155, 381–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hertog, M.G.L.; Feskens, E.J.M.; Hollman, P.C.H.; Katan, M.B.; Kromhout, D. Dietary antioxidant flavonoids and risk of coronary heart disease: The Zutphen Elderly Study. Lancet 1993, 342, 1007–1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kammerer, D.; Claus, A.; Carle, R.; Schieber, A. Polyphenol screening of pomace from red and white grape varieties (Vitis vinifera L.) by HPLC-DAD-MS/MS. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2004, 52, 4360–4367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burns, J.; Gardner, P.T.; O’Neil, J.; Crawford, S.; Morecroft, I.; McPhail, D.B.; Lister, C.; Matthews, D.; MacLean, M.R.; Lean, M.E.; et al. Relationship among antioxidant activity, vasodilation capacity, and phenolic content of red wines. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2000, 48, 220–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kerry, N.L.; Abbey, M. Red wine and fractionated phenolic compounds prepared from red wine inhibit low density lipoprotein oxidation in vitro. Atherosclerosis 1997, 135, 93–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frankel, E.N.; Kanner, J.; German, J.B.; Parks, E.; Kinsella, J.E. Inhibition of oxidation of human low-density lipoprotein by phenolic substances in red wine. Lancet 1993, 341, 454–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duthie, G.G.; Pedersen, M.W.; Gardner, P.T.; Morrice, P.C.; Jenkinson, A.M.; McPhail, D.B.; Steele, G.M. The effect of whisky and wine consumption on total phenol content and antioxidant capacity of plasma from healthy volunteers. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 1998, 52, 733–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wollin, S.D.; Jones, P.J.H. Alcohol, red wine and cardiovascular disease. J. Nutr. 2001, 131, 1401–1404. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Rotondo, S.; de Gaetano, G. Protection from cardiovascular disease by wine and its derived products. Epidemiological evidence and biological mechanisms. World Rev. Nutr. Diet. 2000, 87, 90–113. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Freedman, J.E.; Parker, C.; Li, L.; Perlman, J.A.; Frei, B.; Ivanov, V.; Deak, L.R.; Iafrati, M.D.; Folts, J.D. Select flavonoid and whole juice from purple grapes inhibit platelet function and enhance nitric oxide release. Circulation 2001, 103, 2792–2798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiang, L.; Xiao, L.; Wang, Y.; Li, H.; Huang, Z.; He, X. Health benefits of wine: Don’t expect resveratrol too much. Food Chem. 2014, 156, 258–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vlachogianni, I.C.; Fragopoulou, E.; Kostakis, I.K.; Antonopoulou, S. In vitro assessment of antioxidant activity of tyrosol, resveratrol and their acetylated derivatives. Food Chem. 2015, 177, 165–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leonard, S.S.; Xia, C.; Jiang, B.H.; Stinefelt, B.; Klandorf, H.; Harris, G.K.; Shi, X. Resveratrol scavenges reactive oxygen species and effects radical-induced cellular responses. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2003, 309, 1017–1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pace-Asciak, C.R.; Hahn, S.; Diamandis, E.P.; Soleas, G.; Goldberg, D.M. The red wine phenolics trans-resveratrol and quercetin block human platelet aggregation and eicosanoid synthesis: Implications for protection against coronary heart disease. Clin. Chim. Acta 1995, 235, 207–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subbaramaiah, K.; Chung, W.J.; Michaluart, P.; Telang, N.; Tanabe, T.; Inoue, H.; Jang, M.; Pezzuto, J.M.; Dannenberg, A.J. Resveratrol inhibits cyclooxygenase-2 transcription and activity in phorbol ester-treated human mammary epithelial cells. J. Biol. Chem. 1998, 273, 21875–21882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carluccio, M.A.; Siculella, L.; Ancora, M.A.; Massaro, M.; Scoditti, E.; Storelli, C.; Visioli, F.; Distante, A.; de Caterina, R. Olive oil and red wine antioxidant polyphenols inhibit endothelial activation: Antiatherogenic properties of Mediterranean diet phytochemicals. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2003, 23, 622–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.T.; Shen, F.; Liu, B.H.; Cheng, G.F. Resveratrol inhibits matrix metalloproteinase-9 transcription in U937 cells. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 2003, 24, 1167–1171. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- De la Lastra, C.A.; Villegas, I. Resveratrol as an anti-inflammatory and anti-aging agent: Mechanisms and clinical implications. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2005, 49, 405–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hung, L.M.; Chen, J.K.; Huang, S.S.; Lee, R.S.; Su, M.J. Cardioprotective effect of resveratrol, a natural antioxidant derived from grapes. Cardiovasc. Res. 2000, 47, 549–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szkudelski, T.; Szkudelska, K. Resveratrol and diabetes: From animal to human studies. Biochem. Biophys. Acta 2015, 1852, 1145–1154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fujitaka, K.; Otani, H.; Jo, F.; Jo, H.; Nomura, E.; Iwasaki, M.; Nishikawa, M.; Iwasaka, T.; Das, D.K. Modified resveratrol Longevinex improves endothelial function in adults with metabolic syndrome receiving standard treatment. Nutr. Res. 2011, 31, 842–847. [Google Scholar]

- Wong, R.H.; Howe, P.R.; Buckley, J.D.; Coates, A.M.; Kunz, I.; Berry, N.M. Acute resveratrol supplementation improves flow-mediated dilatation in overweight/obese individuals with mildly elevated blood pressure. Nutr. Metab. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2011, 21, 851–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wong, R.H.; Berry, N.; Coates, A.M.; Buckley, J.D.; Bryan, J.; Kunz, I.; Howe, P.R. Chronic resveratrol consumption improves brachial flow-mediated dilatation in healthy obese adults. J. Hypertens. 2013, 31, 1819–1827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agarwal, B.; Campen, M.J.; Channell, M.M.; Wherry, S.J.; Varamini, B.; Davis, J.G.; Baur, J.A.; Smoliga, J.M. Resveratrol for primary prevention of atherosclerosis: Clinical trial evidence for improved gene expression in vascular endothelium. Int. J. Cardiol. 2013, 166, 246–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tome-Carneiro, J.; Gonzalvez, M.; Larrosa, M.; Yáñez-Gascón, M.J.; García-Almagro, F.J.; Ruiz-Ros, J.A.; García-Conesa, M.T.; Tomás-Barberán, F.A.; Espín, J.C. One-year consumption of a grape nutraceutical containing resveratrol improves the inflammatory and fibrinolytic status of patients in primary prevention of cardiovascular disease. Am. J. Cardiol. 2012, 110, 356–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tome-Carneiro, J.; Gonzalvez, M.; Larrosa, M.; García-Almagro, F.J.; Avilés-Plaza, F.; Parra, S.; Yáñez-Gascón, M.J.; Ruiz-Ros, J.A.; García-Conesa, M.T.; Tomás-Barberán, F.A.; et al. Consumption of a grape extract supplement containing resveratrol decreases oxidized LDL and ApoB in patients undergoing primary prevention of cardiovascular disease: A triple-blind, 6-month follow-up, placebo-controlled, randomized trial. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2012, 56, 810–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goh, K.P.; Lee, H.Y.; Lau, D.P.; Supaat, W.; Chan, Y.H.; Koh, A.F. Effects of resveratrol in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus on skeletal muscle SIRT1 expression and energy expenditure. Int. J. Sport Nutr. Exerc. Metab. 2014, 24, 2–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhatt, J.K.; Thomas, S.; Nanjan, M.J. Resveratrol supplementation improves glycemic control in type 2 diabetes mellitus. Nutr. Res. 2012, 32, 537–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brasnyo, P.; Molnar, G.A.; Mohas, M.; Markó, L.; Laczy, B.; Cseh, J.; Mikolás, E.; Szijártó, I.A.; Mérei, A.; Halmai, R.; et al. Resveratrol improves insulin sensitivity, reduces oxidative stress and activates the Akt pathway in type 2 diabetic patients. Br. J. Nutr. 2011, 106, 383–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muir, A.D.; Westcott, N.D. Flax, the Genus Linum; Taylor & Francis: London, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Penalvo, J.L.; Haajanen, K.M.; Botting, N.; Adlercreutz, H. Quantification of lignans in food using isotope dilution gas chromatography/mass spectrometry. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2005, 53, 9342–9347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smeds, A.I.; Eklund, P.C.; Sjoholm, R.E.; Willfor, S.M.; Nishibe, S.; Deyama, T.; Holmbom, B.R. Quantification of a broad spectrum of lignans in cereals, oilseeds, and nuts. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2007, 55, 1337–1346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuhnle., G.G.; Dell’Aaquila, C.; Aspinall., S.M.; Runswick., S.A.; Milligan, A.A.; Bingham, S.A. Phytoestrogen content of foods of animal origin: Dairy products, eggs, meat, fish, and seafood. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2008, 56, 10099–10104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rowland, I.; Faughnan, M.; Hoey, L.; Wahala, K.; Williamson, G.; Cassidy, A. Bioavailability of phyto-oestrogens. Br. J. Nutr. 2003, 89, S45–S58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Setchell, K.D.; Lawson, A.M.; Borriello, S.P.; Harkness, R.; Gordon, H.; Morgan, D.M.; Kirk, D.N.; Adlercreutz, H.; Anderson, L.C.; Axelson, M. Lignan formation in man-microbial involvement and possible roles in relation to cancer. Lancet 1981, 2, 4–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mousavi, Y.; Adlercreutz, H. Enterolactone and estradiol inhibit each other’s proliferative effect on MCF-7 breast cancer cells in culture. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 1992, 41, 615–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basly, J.P.; Lavier, M.C. Dietary phytoestrogens: Potential selective estrogen enzyme modulators? Planta Med. 2005, 71, 287–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niemeyer, H.B.; Metzler, M. Differences in the antioxidant activity of plant and mammalian lignans. J. Food Eng. 2003, 56, 255–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pellegrini, N.; Valtuena, S.; Ardigo, D.; Brighenti, F.; Franzini, L.; del Rio, D.; Scazzina, F.; Piatti, P.M.; Zavaroni, I. Intake of the plant lignans matairesinol, secoisolariciresinol, pinoresinol, and lariciresinol in relation to vascular inflammation and endothelial dysfunction in middle age-elderly men and post-menopausal women living in Northern Italy. Nutr. Metab. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2010, 20, 64–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Englyst, H.; Wiggins, H.S.; Cummings, J.H. Determination of the non-starch polysaccharides in plant foods by gas-liquid chromatography of constituent sugars as alditol acetates. Analyst 1982, 107, 307–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Englyst, H.N.; Kingman, S.; Cummings, J. Classification and measurement of nutritionally important starch fractions. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 1992, 46, S33–S50. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Goldring, J.M. Resistant starch: Safe intakes and legal status. J. AOAC Int. 2004, 87, 733–739. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Fuentez-Zaragoza, E.; Riquelme-Navarrete, M.J.; Sanchez-Zapta, E.; Perez-Alvarez, J.A. Resistant starch as a functional ingredient: A review. Food Res. Int. 2010, 43, 931–942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nichenametia, S.N.; Weidauer, L.A.; Wey, H.E.; Beare, T.M.; Specker, B.L.; Dey, M. Resistant starch type 4-enriched diet lowered blood cholesterols and improved body composition in a double blind controlled cross-over intervention. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2014, 58, 1365–1369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haub, M.D.; Hubach, K.L.; Al-Tamimi, E.K.; Ornelas, S.; Seib, P.A. Different types of resistant starch elicit different glucose responses. J. Nutr. Metab. 2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maki, K.C.; Phillips, A.K. Dietary substitutions for refined carbohydrate that show promise for reducing risk of type 2 diabetes in men and women. J. Nutr. 2015, 145, 159S–163S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Birt, D.F.; Boylston, T.; Hendrich, S.; Jane, J.L.; Hollis, J.; Li, L.; McClelland, J.; Moore, S.; Phillips, G.J.; Rowling, M.; et al. Resistant starch: Promise for improving human health. Adv. Nutr. 2013, 4, 587–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robertson, M.D.; Wright, J.W.; Loizon, E.; Debard, C.; Vidal, H.; Shojaee-Moradie, F.; Umpleby, A.M. Insulin-sensitizing effects on muscle and adipose tissue after dietary fiber intake in men and women with metabolic syndrome. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2012, 82, 559–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnston, K.; Thomas, E.; Bell, J.; Frost, G.; Robertson, M. Resistant starch improves insulin sensitivity in metabolic syndrome. Diabet. Med. 2010, 27, 391–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robertson, M.D.; Bickerton, A.S.; Dennis, A.L.; Vidal, H.; Frayn, K.N. Insulin-sensitizing effects of dietary resistant starch and effects on skeletal muscle and adipose tissue metabolism. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2005, 82, 559–567. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Maki, K.C.; Pelkman, C.L.; Finocchiaro, E.T.; Kelley, K.M.; Lawless, A.L.; Schild, A.L.; Rains, T.M. Resistant starch from high-amylose maize increases insulin sensitivity in overweight and obese men. J. Nutr. 2012, 142, 717–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bodinham, C.L.; Smith, L.; Thomas, E.L.; Bell, J.D.; Swann, J.R.; Costabile, A.; Russell-Jones, D.; Umpleby, A.M.; Robertson, M.D. Efficacy of increased resistant starch consumption in human type 2 diabetes. Endocr. Connect. 2014, 3, 75–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brownawell, A.M.; Caers, W.; Gibson, G.R.; Kendall, C.W.; Lewis, K.D.; Ringel, Y.; Slavin, J.L. Prebiotics and the health benefits of fiber: Current regulatory status, future research, and goals. J. Nutr. 2012, 142, 962–974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, H.V.; Frassetto, A.; Kowalik, E.J., Jr.; Nawrocki, A.R.; Lu, M.M.; Kosinski, J.R.; Forrest, G. Butyrate and propionate protect against diet-induced obesity and regulate gut hormones via free fatty acid receptor 3-independent mechanisms. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e35240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burcelin, R. The incretins: A link between nutrients and well-being. Br. J. Nutr. 2005, 93, S147–S156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Batterham, R.L.; Bloom, R.L. The gut hormone peptide YY regulates appetite. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2003, 994, 162–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L.; Hua Ting, L.I.; Shen, L.; Fang, Q.C.; Qian, L.L.; Wei Ping, J.I.A. Effect of dietary resistant starch on the prevention and treatment of obesity-related diseases and its possible mechanisms. Biomed. Environ. Sci. 2015, 28, 291–297. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Zhou, J.; Martin, R.J.; Raggio, A.M.; Shen, L.; McCutcheon, K.; Keenan, M.J. The importance of GLP-1 and PYY in resistant starch’s effect on body fat in mice. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2015, 59, 1000–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Higgins, J.A.; Brown, M.A.; Storlien, L.H. Consumption of resistant starch decreases postprandial lipogenesis in white adipose tissue of the rat. Nutr. J. 2006, 5, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aziz, A.A.; Kenney, L.S.; Goulet, B.; Abdel-Aal, E. Dietary starch type affects body weight and glycemic control in freely fed but not energy-restricted obese rats. J. Nutr. 2009, 139, 1881–1889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Higgins, J.A. Resistant starch and energy balance: Impact on weight loss and maintenance. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2014, 54, 1158–1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robertson, M.D. Dietary resistant starch and glucose metabolism. Curr. Opin. Clin. Nutr. Metab. Care 2012, 15, 362–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, C.; Zhang, M.; Wang, S.; Han, R.; Cao, Y.; Hua, W.; Mao, Y.; Zhang, X.; Pang, X.; Wei, C.; et al. Interactions between gut microbiota, host genetics and diet relevant to development of metabolic syndromes in mice. ISME J. 2010, 4, 232–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- García-Rodríguez, C.E.; Mesa, M.D.; Olza, J.; Buccianti, G.; Pérez, M.; Moreno-Torres, R.; de la Cruz, A.P.; Gil, A. Postprandial glucose, insulin and gastrointestinal hormones in healthy and diabetic subjects fed a fructose-free and resistant starch type IV-enriched enteral formula. Euro. J. Nutr. 2013, 52, 1569–1578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hui, H.; Farilla, L.; Merkel, P.; Perfetti, R. The short half-life of glucagon-like peptide-1 in plasma does not reflect its long-lasting beneficial effects. Eur. J. Endocrinol. 2002, 146, 863–869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Behall, K.M.; Howe, J.C. Resistant starch as energy. J. Am. Coll. Nutr. 1996, 15, 248–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Le Leu, R.K.; Winter, J.M.; Christophersen, C.T.; Young, G.P.; Humphreys, K.J.; Hu, Y.; Gratz, S.W.; Miller, R.B.; Topping, D.L.; Bird, A.R.; et al. Butyrylated starch intake can prevent red meat-induced O6-methyl-2-deoxyguanosine adducts in human rectal tissue: A randomized clinical trial. Br. J. Nutr. 2015, 114, 220–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vaziri, N.D.; Liu, S.M.; Lau, W.L.; Khazaeli, M.; Nazertehrani, S.; Farzaneh, S.H.; Kieffer, D.A.; Adams, S.H.; Martin, R.J. High amylose resistant starch diet ameliorates oxidative stress, inflammation, and progression of chronic kidney disease. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e114881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Curtius, T.; Goebel, F. Uber Glycollather. J. Prakt. Chem. 1988, 37, 150–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abderhalden, E.; Haas, R. Further studies on the structure of proteins: Studies on the physical and chemical properties of 2,5-di- ketopiperazines. Z. Physiol. Chem. 1926, 151, 114–l19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasad, C. Bioactive cyclic dipeptides. Peptides 1995, 16, 151–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasad, C. Neurobiology of cyclo (His-Pro). Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1989, 553, 232–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prasad, C.; Kumar, S.; Adkinson, W.; McGregor, J.U. Hormones in foods: Abundance of authentic cyclo (His-Pro)-like immunoreactivity in milk and yogurt. Nutr. Res. 1995, 15, 1623–1635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilton, C.W.; Prasad, C.; Vo, P.; Mouton, C. Food contains the bioactive peptide, cyclo (His-Pro). J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 1992, 75, 375–378. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Hilton, C.W.; Prasad, C.; Svec, F.; Vo, P.; Reddy, S. Cyclo (His-Pro) in nutritional supplements. Lancet 1990, 336, 1455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mori, M.; Prasad, C.; Wilber, J.F. Specific radioimmunoassay of cyclo (His-Pro), a biologically active metabolite of thyrotropin-releasing hormone. Endocrinology 1981, 108, 1995–1997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bellezza, I.; Peirce, M.J.; Minelli, A. Cyclic dipeptides: From bugs to brain. Trends Mol. Med. 2014, 20, 551–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Minelli, A.; Bellezza, I.; Grottelli, S.; Galli, F. Focus on cyclo (His-Pro): History and perspectives as antioxidant peptide. Amino Acids 2008, 35, 283–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prasad, C. Cyclo (His-Pro): Its distribution, origin and function in the human. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 1988, 12, 19–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morley, J.E.; Levine, A.S.; Prasad, C. Histidyl-proline diketopiperazine decreases food intake in rats. Brain Res. 1981, 210, 475–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kow, L.M.; Pfaff, D.W. The effects of the TRH metabolite cyclo (His-Pro) and its analogs on feeding. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 1991, 38, 359–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kow, L.M.; Pfaff, D.W. Cyclo (His-Pro) potentiates the reduction of food intake induced by amphetamine, fenfluramine, or serotonin. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 1991, 38, 365–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilber, J.F.; Mori, M.; Pegues, J.; Prasad, C. Endogenous histidyl-proline diketopiperazine [cyclo (His-Pro)]: A potential satiety neuropeptide in normal and genetically obese rodents. Trans. Assoc. Am. Physicians 1983, 96, 131–136. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Bowden, C.R.; Karkanias, C.D.; Bean, A.J. Re-evaluation of histidyl-proline diketopiperazine [cyclo (His-Pro)] effects on food intake in the rat. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 1988, 29, 357–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasad, C.; Mizuma, H.; Brock, J.W.; Porter, J.R.; Svec, F.; Hilton, C. A paradoxical elevation of brain cyclo (His-Pro) levels in hyperphagic obese Zucker rats. Brain Res. 1995, 699, 149–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mori, M.; Pegues, J.; Prasad, C.; Wilber, J.F. Fasting and feeding-associated changes in cyclo (His-Pro)-like immunoreactivity in the rat brain. Brain Res. 1983, 268, 181–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steiner, H.; Wilber, J.F.; Prasad, C.; Rogers, D.; Rosenkranz, R.T. Histidyl proline diketopiperazine (Cyclo [His-Pro]) in eating disorders. Neuropeptides 1989, 14, 185–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, M.K.; Hwang, I.K.; Rosenthal, M.J.; Harris, D.M.; Yamaguchi, D.T.; Yip, I.; Go, V.L. Anti-Hyperglycemic Activity of Zinc Plus Cyclo (His-Pro) in Genetically Diabetic Goto-Kakizaki and Aged Rats. Exp. Biol. Med. 2003, 228, 1338–1345. [Google Scholar]

- Song, M.K.; Rosenthal, M.J.; Song, A.M.; Uyemura, K.; Yang, H.; Ament, M.E.; Yamaguchi, D.T.; Cornford, E.M. Body weight reduction in rats by oral treatment with zinc plus cyclo-(His-Pro). Br. J. Pharmacol. 2009, 158, 442–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mori, M.; Pegues, J.; Prasad, C.; Wilber, J.; Peterson, J.; Githens, S. Histidyl-proline diketopiperazine cyclo (His-Pro): Identification and characterization in rat pancreatic islets. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1983, 115, 281–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leduque, P.; Jackson, I.M.; Kervran, A.; Aratan-Spire, S.; Czernichow, P.; Dubois, P.M. Histidyl-Proline Diketopiperazine (His-Pro DKP) Immunoreactivity is Present in the Glucagon-Containing Cells of the Human Fetal Pancreas. J. Clin. Investig. 1987, 79, 875–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hilton, C.W.; Prasad, C.; Wilber, J.F. Acute alterations of cyclo (His-Pro) levels after oral ingestion of glucose. Neuropeptides 1990, 15, 55–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilton, C.W.; Reddy, S.; Prasad, C.; Wilber, J.F. Change in circulating cyclo (His-Pro) concentrations in rats after ingestion of oral glucose compared to intravenous glucose and controls. Endocr. Res. 1990, 16, 139–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, M.K.; Rosenthal, M.J.; Song, A.M.; Yang, H.; Ao, Y.; Yamaguchi, D.T. Raw vegetable food containing high cyclo (his-pro) improved insulin sensitivity and body weight control. Metabolism 2005, 54, 1480–1489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jung, E.Y.; Lee, H.S.; Choi, J.W.; Ra, K.S.; Kim, M.R.; Suh, H.J. Glucose tolerance and antioxidant activity of spent brewer’s yeast hydrolysate with a high content of Cyclo-His-Pro (CHP). J. Food Sci. 2011, 76, C272–C278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hilton, C.W.; Mizuma, H.; Svec, F.; Prasad, C. Relationship between plasma cyclo (His-Pro), a neuropeptide common to processed protein-rich food, and C-peptide/insulin molar ratio in obese women. Nutr. Neurosci. 2001, 4, 469–474. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Samols, E.; Marri, G.; Marks, V. Promotion of insulin secretion by glucagon. Lancet 1965, 2, 415–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huypens, P.; Ling, Z.; Pipeleers, D.; Schuit, F. Glucagon receptors on human islet cells contribute to glucose competence of insulin release. Diabetologia 2000, 43, 1012–1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kawai, K.; Yokota, C.; Ohashi, S.; Watanabe, Y.; Yamashita, K. Evidence that glucagon stimulates insulin secretion through its own receptor in rats. Diabetologia 1995, 38, 274–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pivovarova, O.; Bernigau, W.; Bobbert, T.; Isken, F.; Möhlig, M.; Spranger, J.; Weickert, M.O.; Osterhoff, M.; Pfeiffer, A.F.; Rudovich, N. Hepatic insulin clearance is closely related to metabolic syndrome components. Diabetes Care 2013, 36, 3779–3785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meshkani, R.; Adeli, K. Hepatic insulin resistance, metabolic syndrome and cardiovascular disease. Clin. Biochem. 2009, 42, 1331–1346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biddinger, S.B.; Hernandez-Ono, A.; Rask-Madsen, C.; Haas, J.T.; Alemán, J.O.; Suzuki, R.; Scapa, E.F.; Agarwal, C.; Carey, M.C.; Stephanopoulos, G.; et al. Hepatic insulin resistance is sufficient to produce dyslipidemia and susceptibility to atherosclerosis. Cell Metab. 2008, 7, 125–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Basu, A.; Betts, N.M.; Nguyen, A.; Newman, E.D.; Fu, D.; Lyons, T.J. Freeze-dried strawberries lower serum cholesterol and lipid peroxidation in adults with abdominal adiposity and elevated serum lipids. J. Nutr. 2014, 144, 830–837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leong, D.J.; Choudhury, M.; Hirsh, D.M.; Hardin, J.A.; Cobelli, N.J.; Sun, H.B. Nutraceuticals: Potential for Chondroprotection and Molecular Targeting of Osteoarthritis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2013, 14, 23063–23085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huntley, A.L. The health benefits of berry flavonoids for menopausal women: Cardiovascular disease, cancer and cognition. Maturitas 2009, 63, 297–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szajdek, A.; Borowska, E.J. Bioactive compounds and health-promoting properties of berry fruits: A review. Plant Foods Hum. Nutr. 2008, 63, 147–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barnes, S. Nutritional genomics, polyphenols, diets, and their impact on dietetics. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 2008, 108, 1888–1895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, C.L.; Smith, B.J.; Lo, D.-F.; Chyu, M.-C.; Dunn, D.M.; Chen, C.-H.; Kwun, I.-S. Dietary polyphenols and mechanisms of osteoarthritis. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2012, 23, 1367–1377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alvarez-Suarez, J.M.; Giampieri, F.; Tulipani, S.; Casoli, T.; di Stefano, G.; Gonzalez-Paramas, A.M.; Santos-Buelga, C.; Busco, F.; Quiles, J.L.; Cordero, M.D.; et al. One-month strawberry-rich anthocyanin supplementation ameliorates cardiovascular risk, oxidative stress markers and platelet activation in humans. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2014, 25, 289–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodriguez-Mateos, A.; Ishisaka, A.; Mawatari, K.; Vidal-Diez, A.; Spencer, J.P.E.; Terao, J. Blueberry intervention improves vascular reactivity and lowers blood pressure in high-fat-, high-cholesterol-fed rats. Br. J. Nutr. 2013, 109, 1746–1754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zunino, S.J.; Parelman, M.A.; Freytag, T.L.; Stephensen, C.B.; Kelley, D.S.; Mackey, B.E.; Woodhouse, L.R.; Bonnel, E.L. Effects of dietary strawberry powder on blood lipids and inflammatory markers in obese human subjects. Br. J. Nutr. 2012, 108, 900–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Basu, A.; Du, M.; Leyva, M.J.; Sanchez, K.; Betts, N.M.; Wu, M.; Aston, C.E.; Lyons, T.J. Blueberries decrease cardiovascular risk factors in obese men and women with metabolic syndrome. J. Nutr. 2010, 140, 1582–1587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Erlund, I.; Koli, R.; Alfhan, G.; Marniemi, J.; Puukka, P.; Mustonen, P.; Mattila, P.; Jula, A. Favorable effects of berry consumption on platelet function, blood pressure and HDL cholesterol. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2008, 87, 323–331. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ruel, G.; Pomerleau, S.; Couture, P.; Lemieux, S.; Lamarche, B.; Couillard, C. Favourable impact of low-calorie cranberry juice consumption on plasma HDL-cholesterol concentrations in men. Br. J. Nutr. 2006, 96, 354–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruel, G.; Pomerleau, S.; Couture, P.; Lamarche, B.; Couillard, C. Changes in plasma antioxidant capacity and oxidized low-density lipoprotein levels in men after short-term cranberry juice consumption. Metabolism 2005, 54, 856–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodriguez-Mateos, A.; Rendeiro, C.; Bergillos-Mecca, T.; Tabatabaee, S.; George, T.W.; Heiss, C.; Spencer, J.P. Intake and time dependence of blueberry flavonoid-induced improvements in vascular function: A randomized, controlled, double-blind, crossover intervention study with mechanistic insights into biological activity. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2013, 98, 1179–1191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heinonen, I.M.; Meyer, A.S.; Frankel, E.N. Antioxidant activity of berry polyphenolics on human low-density lipoprotein and liposome oxidation. J. Agric. Food Chem. 1998, 46, 4107–4112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, A.S.; Donovan, J.L.; Pearson, D.A.; Waterhouse, A.L.; Frankel, E.N. Fruit hydroxycinnamic acids inhibit human low-density lipoprotein oxidation in vitro. J. Agric. Food Chem. 1998, 46, 1783–1787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coban, J.; Evran, B.; Ozkan, F.; Cevik, A.; Dogru-Abbasoglu, S.; Uysal, M. Effect of blueberry feeding on lipids and oxidative stress in the serum, liver and aorta of Guinea pigs fed on a high-cholesterol diet. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 2013, 77, 389–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Del Bo, C.; Riso, P.; Campolo, J.; Moller, P.; Loft, S.; Klimis-Zacas, D.; Brambilla, A.; Rizzolo, A.; Porrini, M. A single portion of blueberry (Vaccinium corymbosum L.) improves protection against DNA damage but not vascular function in healthy male volunteers. Nutr. Res. 2013, 33, 220–227. [Google Scholar]

- Cassidy, A.; O-Reilly, E.; Kay, C.; Sampson, L.; Franz, M.; Forman, J.P.; Curhan, G.; Rimm, E.B. Habitual intake of flavonoid subclasses and incident hypertension in adults. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2011, 93, 338–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, S.A.; Figueroa, A.; Navaei, N.; Wong, A.; Kalfon, R.; Ormsbee, L.T.; Feresin, R.G.; Elam, M.L.; Hooshmand, S.; Payton, M.E.; et al. Daily blueberry consumption improves blood pressure and arterial stiffness in postmenopausal women with pre-and stage-1 hypertension: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 2015, 115, 369–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McAnulty, L.S.; Collier, S.R.; Landram, M.J.; Whittaker, D.S.; Isaacs, S.E.; Klemka, J.M.; Cheek, S.L.; Arms, J.C.; McAnulty, S.R. Six weeks daily ingestion of whole blueberry powder increases natural killer cell counts and reduces arterial stiffness in sedentary males and females. Nutr. Res. 2014, 34, 577–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McAnulty, S.R.; McAnulty, L.S.; Morrow, J.D.; Khardouni, D.; Shooter, L.; Monk, J.; Gross, S.; Brown, V. Effect of daily fruit ingestion on angiotensin converting enzyme activity, blood pressure, and oxidative stress in chronic smokers. Free Radic. Res. 2005, 39, 1241–1248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stull, A.J.; Cash, K.C.; Champagne, C.M.; Gupta, A.K.; Boston, R.; Beyl, R.A.; Johnson, W.D.; Cefalu, W.T. Blueberries improve endothelial function, but not blood pressure, in adults with metabolic syndrome: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Nutrients 2015, 7, 4107–4123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amani, R.; Moazen, S.; Shahbazian, H.; Ahmadi, K.; Jalali, M.T. Flavonoid-rich beverage effects on lipid profile and blood pressure in diabetic patients. World J. Diabetes 2014, 5, 962–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martineau, L.C.; Couture, A.; Spoor, D.; Benhaddou-Andaloussi, A.; Harris, C.; Meddah, B.; Leduc, C.; Burt, A.; Vuong, T.; Mai Le, P.; et al. Anti-diabetic properties of the Canadian lowbush blueberry Vaccinium angustifolium Ait. Phytomedicine 2006, 13, 612–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jayaprakasam, B.; Vareed, S.K.; Olson, L.K.; Nair, M.G. Insulin secretion by bioactive anthocyanins and anthocyanidins present in fruits. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2005, 53, 28–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stull, A.J.; Cash, K.C.; Johnson, W.D.; Champagne, C.M.; Cefalu, W.T. Bioactives in blueberries improve insulin sensitivity in obese, insulin-resistant men and women. J. Nutr. 2010, 140, 1764–1768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DeFuria, J.; Bennett, G.; Strissel, K.J.; Perfield, J.W., II; Milbury, P.E.; Greenberg, A.S.; Obin, M.S. Dietary blueberry attenuates whole-body insulin resistance in high fat-fed mice by reducing adipocyte death and its inflammatory sequelae. J. Nutr. 2009, 139, 1510–1516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shahidi, F.; Naczk, M. Food phenolics: An overview. In Food Phenolics: Sources, Chemistry, Effects, Applications; Shahidi, F., Naczk, M., Eds.; Technomic Publishing Company Inc.: Lancaster, PA, USA, 1995; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Hennekens, C.H.; Buring, J.E.; Manson, J.E.; Stampfer, M.; Rosner, B.; Cook, N.R.; Belanger, C.; LaMotte, F.; Gaziano, J.M.; Ridker, P.M.; et al. Lack of effect of long-term supplementation with β-carotene on the incidence of malignant neoplasms and cardiovascular disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 1996, 334, 1145–1149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

© 2015 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Prasad, C.; Imrhan, V.; Juma, S.; Maziarz, M.; Prasad, A.; Tiernan, C.; Vijayagopal, P. Bioactive Plant Metabolites in the Management of Non-Communicable Metabolic Diseases: Looking at Opportunities beyond the Horizon. Metabolites 2015, 5, 733-765. https://doi.org/10.3390/metabo5040733

Prasad C, Imrhan V, Juma S, Maziarz M, Prasad A, Tiernan C, Vijayagopal P. Bioactive Plant Metabolites in the Management of Non-Communicable Metabolic Diseases: Looking at Opportunities beyond the Horizon. Metabolites. 2015; 5(4):733-765. https://doi.org/10.3390/metabo5040733

Chicago/Turabian StylePrasad, Chandan, Victorine Imrhan, Shanil Juma, Mindy Maziarz, Anand Prasad, Casey Tiernan, and Parakat Vijayagopal. 2015. "Bioactive Plant Metabolites in the Management of Non-Communicable Metabolic Diseases: Looking at Opportunities beyond the Horizon" Metabolites 5, no. 4: 733-765. https://doi.org/10.3390/metabo5040733

APA StylePrasad, C., Imrhan, V., Juma, S., Maziarz, M., Prasad, A., Tiernan, C., & Vijayagopal, P. (2015). Bioactive Plant Metabolites in the Management of Non-Communicable Metabolic Diseases: Looking at Opportunities beyond the Horizon. Metabolites, 5(4), 733-765. https://doi.org/10.3390/metabo5040733