In Vitro Antioxidant, Anti-Platelet and Anti-Inflammatory Natural Extracts of Amphiphilic Bioactives from Organic Watermelon Juice and Its By-Products

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials, Reagents and Instrumentation

2.2. Sample Preparation and Extraction-Separations

2.2.1. Preparation of Watermelon Juice Samples

2.2.2. Preparation of Watermelon By-Product Samples

2.2.3. Counter-Current Distribution (CCD)

2.2.4. Evaporation of Samples

2.2.5. Aliquoting of the Amphiphilic (TAC) and Neutral (TLC) Lipid Samples

2.3. Determination of Total Phenolic Content (Folin–Ciocalteu Assay)

2.4. Determination of Total Carotenoid Content (TCC)

2.5. Determination of Total Antioxidant Activity (TAA)

2.5.1. ABTS Assay

2.5.2. DPPH Assay

2.5.3. FRAP Assay

2.6. Platelet Aggregometry Biological Assays

2.7. Assessment of Fatty Acid Composition by LC–MS

2.8. ATR–FTIR Analysis

2.9. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Yield of Extraction

3.2. Total Phenolic Content

3.3. Total Carotenoid Content

3.4. Antioxidant Activity Expressed as ABTS Values

3.5. Antioxidant Activity Expressed as TEAC Values According to the DPPH Assay

3.6. Antioxidant Activity Expressed as FRAP Values

3.7. ATR-FTIR Spectroscopy

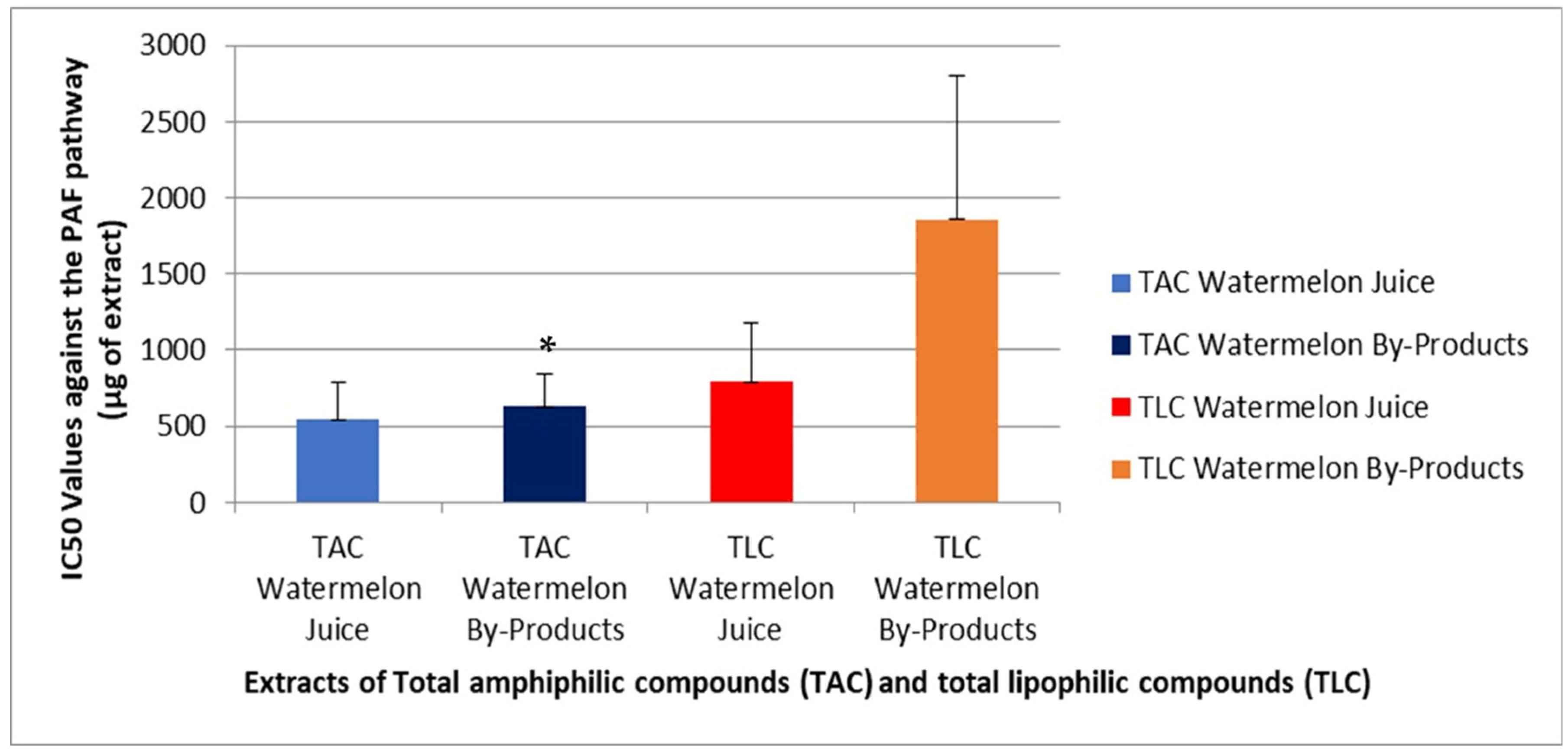

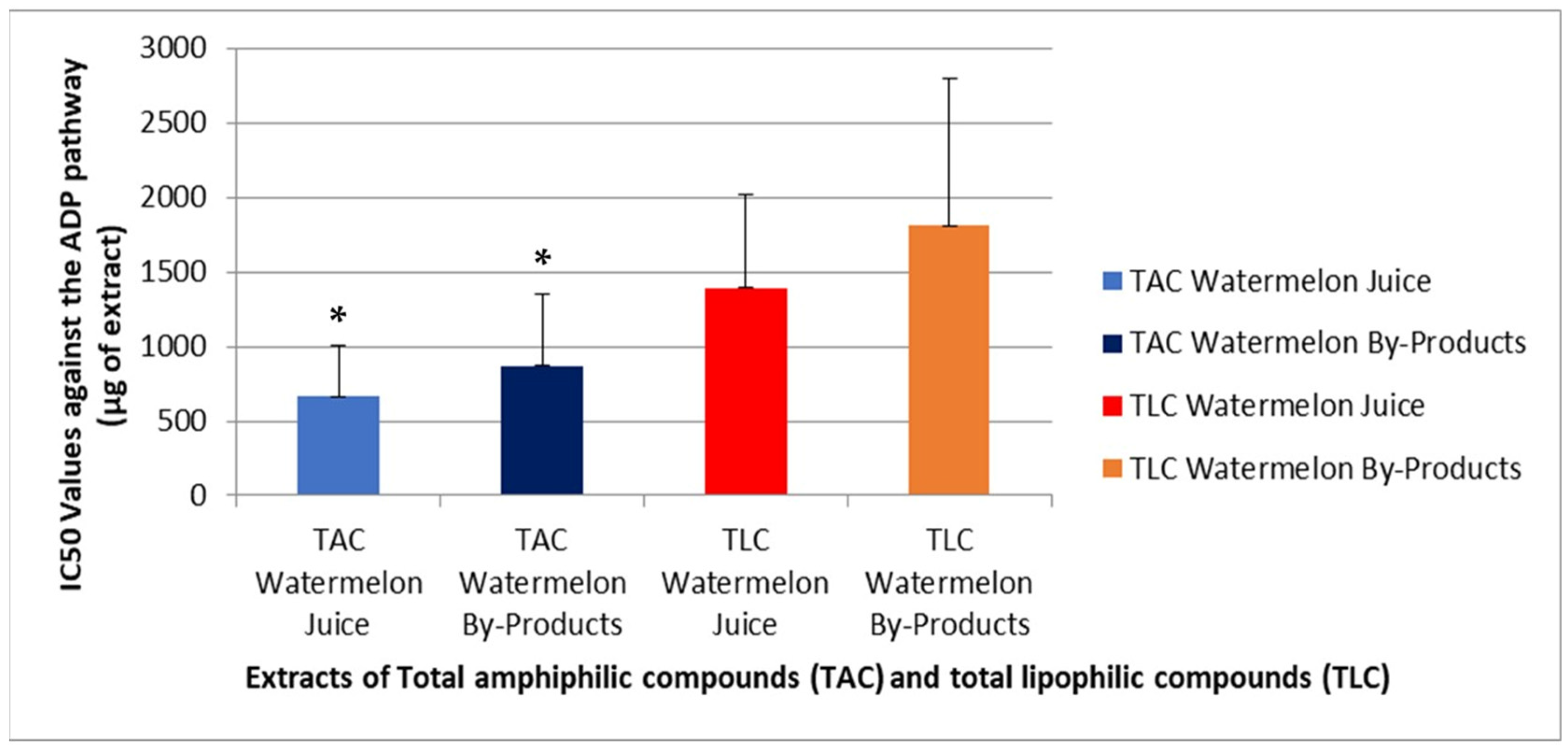

3.8. Platelet Aggregometry Assay—Evaluation of Antithrombotic and Anti-Inflammatory Activity

3.9. Fatty Acid Composition of the Saponified TAC Fractions from Watermelon Juice and By-Products

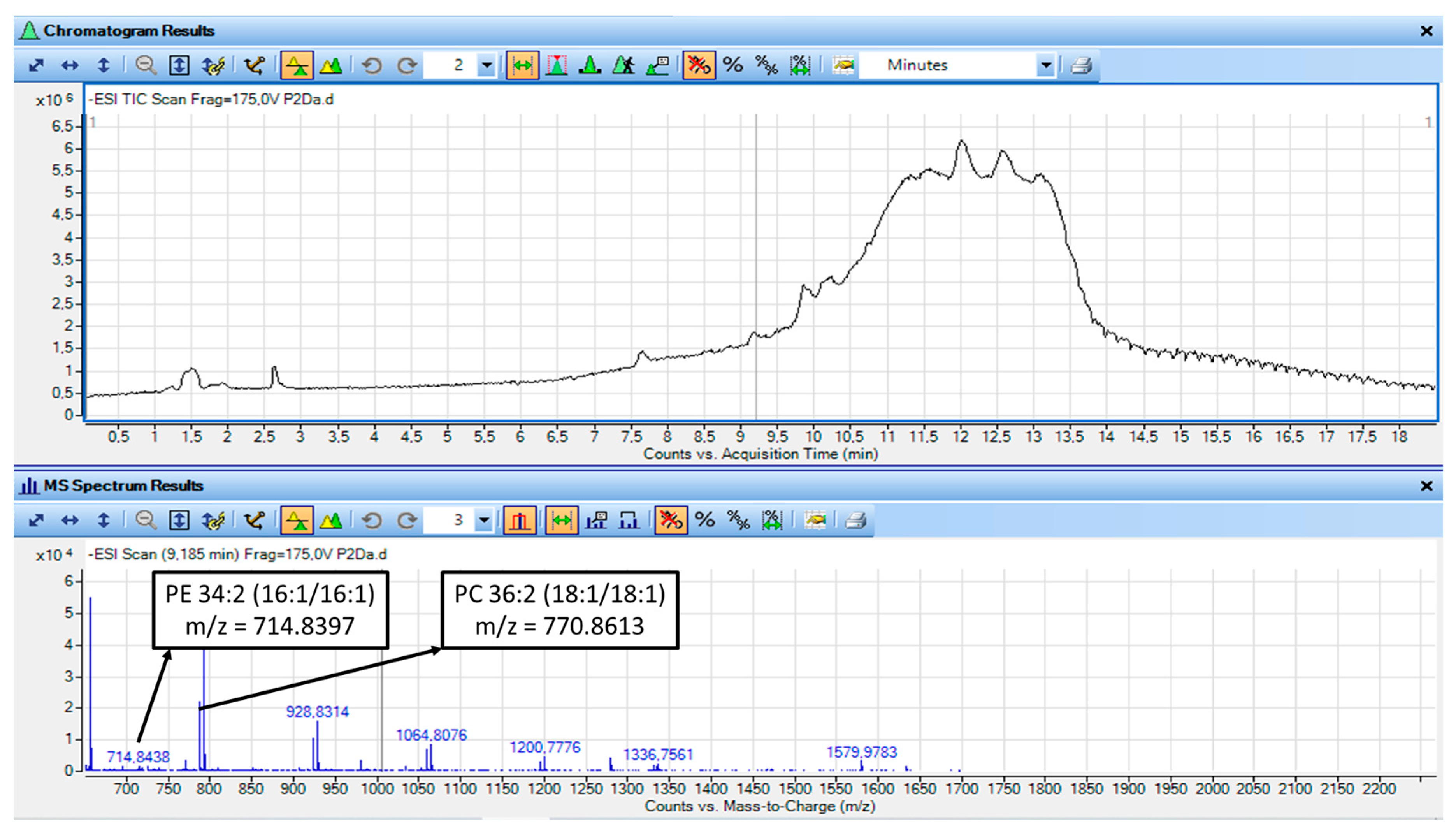

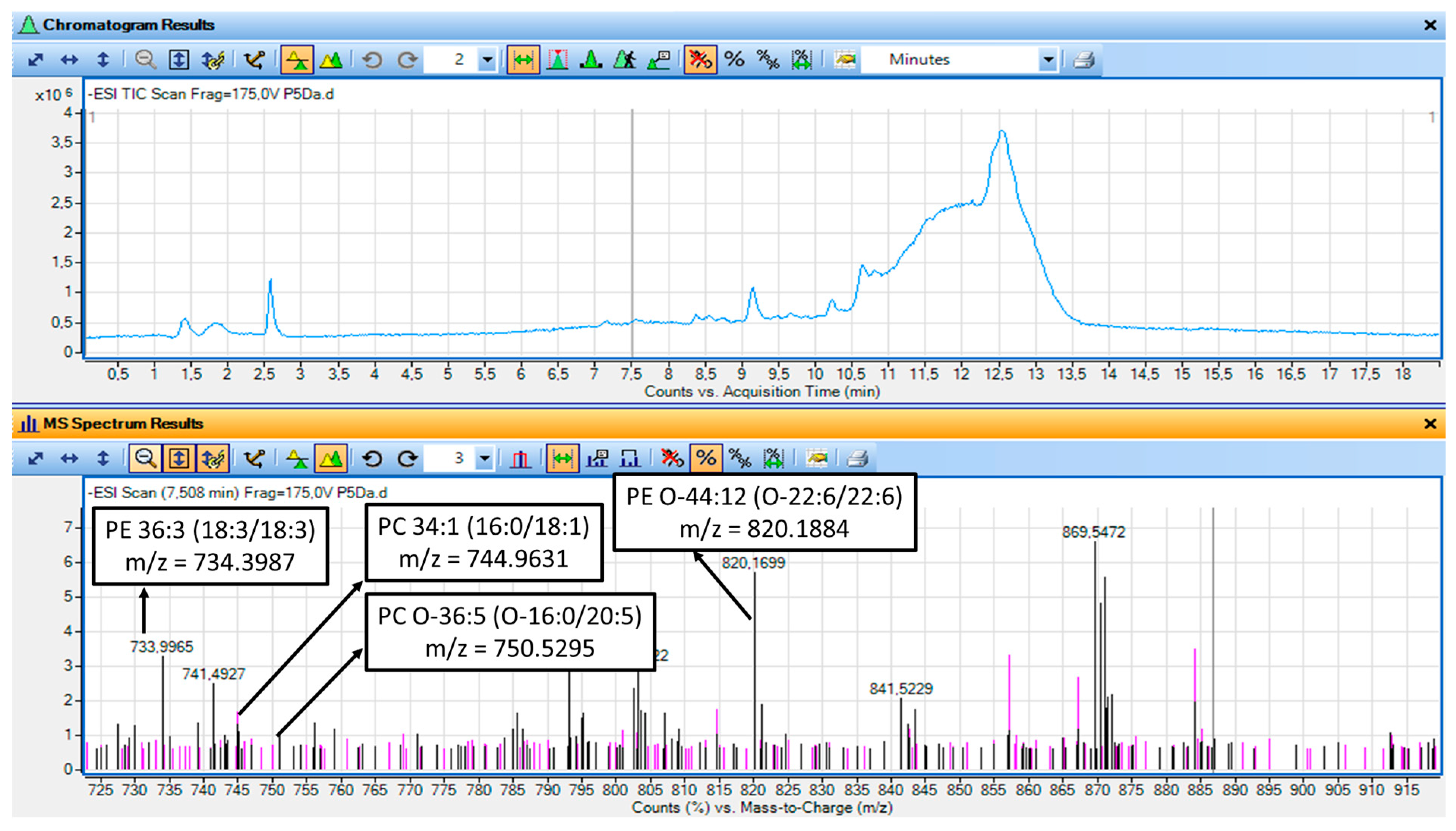

3.10. LC-MS Analysis of the Non-Saponified TAC Extracts from Both the Watermelon Juice and Its By-Products

4. Discussion

4.1. Yield of Extraction in TACs and TLCs for Both the Watermelon Juice and the By-Products

4.2. Total Phenolic Content of Both TACs and TLCs from Watermelon Juice and Its By-Products

4.3. Total Carotenoid Content in the Extracts from Both the Watermelon Juice and Its By-Products

4.4. Antioxidant Activity of Extracts Expressed as ABTS Values

4.5. Antioxidant Activity of Extracts Expressed as TEAC Values According to the DPPH Assay

4.6. Antioxidant Activity Based on the FRAP Assay

4.7. ATR-FTIR Spectroscopy of TAC Fractions from Watermelon Juice and Its By-Products

4.8. Evaluation of Antithrombotic and Anti-Inflammatory Activities of Samples by the Platelet Aggregometry Assay

4.9. Fatty Acid Composition of the Bioactive PLs of the TAC Extracts from Watermelon Juice and By-Products

4.10. Structural Elucidation and Proposed Structures of the Main Bioactive Phospholipids Detected in the TAC Extracts of Both the Watermelon Juice and By-Products

5. Limitations

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| Abbreviation | Meaning |

| EPA | Eicosapentaenoic acid |

| DHA | Docosahexaenoic acid |

| n3 | Omega-3 |

| n6 | Omega-6 |

| n9 | Omega-9 |

| SFA | Saturated fatty acid |

| MUFA | Monounsaturated fatty acid |

| PUFA | Polyunsaturated fatty acid |

| ND | Undetectable |

| TAC | Total amphiphilic compound |

| TLC | Total lipophilic compound |

| TL | Total lipid |

| WMJ | Watermelon juice |

| FFA | Free fatty acid |

| LC–MS | Liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry |

| KOH | Potassium hydroxide |

| HPLC | High-performance liquid chromatography |

| ESI | Electrospray ionization |

| m/z | Mass-to-charge ratio |

| TPC | Total phenolic content |

| TCC | Total carotenoid content |

| TAA | Total antioxidant activity |

| DPPH | 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl |

| ABTS | 2,2′-azino-bis(3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonic acid) |

| FRAP | Ferric reducing antioxidant power |

| TE / TEAC | Trolox equivalent / Trolox equivalent antioxidant capacity |

| DW | Dry weight |

| PRP | Platelet-rich plasma |

| PPP | Platelet-poor plasma |

| PAF | Platelet-activating factor |

| ADP | Adenosine diphosphate |

| IC50 | Half-maximal inhibitory concentration |

| ATR–FTIR | Attenuated total reflectance Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy |

| CCD | Counter-current distribution |

| GAE | Gallic acid equivalent |

| CE | β-Carotene equivalent |

| HCl | Hydrochloric acid |

| Na2CO3 | Sodium carbonate |

| PLA2 | Phospholipase A2 |

| HDL | High-density lipoprotein |

| sn-2 | Stereospecific numbering position 2 on glycerol |

| PL | Polar lipid |

| FA | Fatty acid |

| UFA | Unsaturated fatty acid |

| hPRP | Human platelet-rich plasma |

References

- Nadeem, M.; Navida, M.; Ameer, K.; Siddique, F.; Iqbal, A.; Malik, F.; Ranjha, M.; Yasmin, Z.; Kanwal, R.; Javaria, S. Watermelon Nutrition Profile, Antioxidant Activity, and Processing. Korean J. Food Preserv. 2022, 29, 531–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meghwar, P.; Ghufran Saeed, S.M.; Ullah, A.; Nikolakakis, E.; Panagopoulou, E.; Tsoupras, A.; Smaoui, S.; Mousavi Khaneghah, A. Nutritional Benefits of Bioactive Compounds from Watermelon: A Comprehensive Review. Food Biosci. 2024, 61, 104609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bretscher, P.; Egger, J.; Shamshiev, A.; Trötzmüller, M.; Köfeler, H.; Carreira, E.M.; Kopf, M.; Freigang, S. Phospholipid Oxidation Generates Potent Anti-inflammatory Lipid Mediators That Mimic Structurally Related Pro-resolving Eicosanoids by Activating Nrf2. EMBO Mol. Med. 2015, 7, 593–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marra, A.; Manousakis, V.; Koutis, N.; Zervas, G.P.; Ofrydopoulou, A.; Shiels, K.; Saha, S.K.; Tsoupras, A. In Vitro Antioxidant, Antithrombotic and Anti-Inflammatory Activities of the Amphiphilic Bioactives Extracted from Avocado and Its By-Products. Antioxidants 2025, 14, 146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vandorou, M.; Plakidis, C.; Tsompanidou, I.M.; Ofrydopoulou, A.; Shiels, K.; Saha, S.K.; Tsoupras, A. In Vitro Antioxidant, Antithrombotic and Anti-Inflammatory Properties of the Amphiphilic Bioactives from Greek Organic Starking Apple Juice and Its By-Products (Apple Pomace). Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 2807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moysidou, A.M.; Cheimpeloglou, K.; Koutra, S.I.; Manousakis, V.; Ofrydopoulou, A.; Shiels, K.; Saha, S.K.; Tsoupras, A. In Vitro Antioxidant, Antithrombotic and Anti-Inflammatory Activities of Bioactive Metabolites Extracted from Kiwi and Its By-Products. Metabolites 2025, 15, 400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jarret, R.L.; Levy, I.J. Oil and Fatty Acid Contents in Seed of Citrullus lanatus Schrad. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2012, 60, 5199–5204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsoupras, A.; Cholidis, P.; Kranas, D.; Galouni, E.A.; Ofrydopoulou, A.; Efthymiopoulos, P.; Shiels, K.; Saha, S.K.; Kyzas, G.Z.; Anastasiadou, C. Anti-Inflammatory, Antithrombotic, and Antioxidant Properties of Amphiphilic Lipid Bioactives from Shrimp. Pharmaceuticals 2025, 18, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manirakiza, P.; Covaci, A.; Schepens, P. Comparative Study on Total Lipid Determination Using Soxhlet, Roese-Gottlieb, Bligh & Dyer, and Modified Bligh & Dyer Extraction Methods. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2001, 14, 93–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosidou, S.; Zannas, Z.; Ofrydopoulou, A.; Lambropoulou, D.A.; Tsoupras, A. Psychotropic and neurodegenerative drugs modulate platelet activity via the PAF pathway. Neurochem. Int. 2025, 191, 106073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puri, R.N.; Colman, R.W. ADP-Induced Platelet Activation. Crit. Rev. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 1997, 32, 437–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Upton, J.E.M.; Grunebaum, E.; Sussman, G.; Vadas, P. Platelet Activating Factor (PAF): A Mediator of Inflammation. BioFactors Oxf. Engl. 2022, 48, 1189–1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vordos, N.; Giannakopoulos, S.; Vansant, E.F.; Kalaitzis, C.; Nolan, J.W.; Bandekas, D.V.; Karavasilis, I.; Mitropoulos, A.C.; Touloupidis, S. Small-Angle X-Ray Scattering (SAXS) and Nitrogen Porosimetry (NP): Two Novel Techniques for the Evaluation of Urinary Stone Hardness. Int. Urol. Nephrol. 2018, 50, 1779–1785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williamson, G. Bioavailability of Food Polyphenols: Current State of Knowledge. Annu. Rev. Food Sci. Technol. 2025, 16, 315–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chrysikopoulou, V.; Rampaouni, A.; Koutsia, E.; Ofrydopoulou, A.; Mittas, N.; Tsoupras, A. Anti-Inflammatory, Antithrombotic and Antioxidant Efficacy and Synergy of a High-Dose Vitamin C Supplement Enriched with a Low Dose of Bioflavonoids; In Vitro Assessment and In Vivo Evaluation Through a Clinical Study in Healthy Subjects. Nutrients 2025, 17, 2643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamuz, S.; Munekata, P.; Gullón, B.; Rocchetti, G.; Montesano, D.; Lorenzo, J.M. Citrullus lanatus as Source of Bioactive Components: An up-to-Date Review. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 111, 208–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McClements, D.J.; Öztürk, B. Utilization of Nanotechnology to Improve the Application and Bioavailability of Phytochemicals Derived from Waste Streams. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2022, 70, 6884–6900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wireko-Manu, F.; Tabiri, B.; Agbenorhevi, J.; Ompouma, E. Watermelon Seeds as Food: Nutrient Composition, Phytochemicals and Antioxidant Activity. Int. J. Food Sci. Nutr. 2016, 5, 139. [Google Scholar]

- Acun, S.; Gül, H.; Seyrekoğlu, F. Comprehensive Analysis of Physical, Chemical, and Phenolic Acid Properties of Powders Derived from Watermelon (Crimson Sweet) by-Products. J. Food Sci. 2025, 90, e70092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balasundram, N.; Sundram, K.; Samman, S. Phenolic Compounds in Plants and Agri-Industrial by-Products: Antioxidant Activity, Occurrence, and Potential Uses. Food Chem. 2006, 99, 191–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molteni, C.; La Motta, C.; Valoppi, F. Improving the Bioaccessibility and Bioavailability of Carotenoids by Means of Nanostructured Delivery Systems: A Comprehensive Review. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 1931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adamantidi, T.; Lafara, M.-P.; Venetikidou, M.; Likartsi, E.; Toganidou, I.; Tsoupras, A. Utilization and Bio-Efficacy of Carotenoids, Vitamin A and Its Vitaminoids in Nutricosmetics, Cosmeceuticals, and Cosmetics’ Applications with Skin-Health Promoting Properties. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 1657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nissar, J.; Shafiq Sidiqi, U.; Hussain Dar, A.; Akbar, U. Nutritional Composition and Bioactive Potential of Watermelon Seeds: A Pathway to Sustainable Food and Health Innovation. Sustain. Food Technol. 2025, 3, 375–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, A.J.; Vinyard, B.T.; Wiley, E.R.; Brown, E.D.; Collins, J.K.; Perkins-Veazie, P.; Baker, R.A.; Clevidence, B.A. Consumption of Watermelon Juice Increases Plasma Concentrations of Lycopene and Beta-Carotene in Humans. J. Nutr. 2003, 133, 1043–1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, W.; Lv, P.; Gu, H. Studies on Carotenoids in Watermelon Flesh. Agric. Sci. 2013, 04, 13–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perkins-Veazie, P.; Collins, J.K.; Davis, A.R.; Roberts, W. Carotenoid Content of 50 Watermelon Cultivars. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2006, 54, 2593–2597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, K.W.; Ismail, A.; Tan, C.P.; Rajab, N.F. Optimization of Oven Drying Conditions for Lycopene Content and Lipophilic Antioxidant Capacity in a By-Product of the Pink Guava Puree Industry Using Response Surface Methodology. LWT-Food Sci. Technol. 2010, 43, 729–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, L.; Goupy, P.; Fröhlich, K.; Dangles, O.; Caris-Veyrat, C.; Böhm, V. Comparative Study on Antioxidant Activity of Lycopene (Z)-Isomers in Different Assays. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2011, 59, 4504–4511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, C.; Park, M.; Kim, S.; Cho, Y. Antioxidant Capacity and Anti-Inflammatory Activity of Lycopene in Watermelon. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2014, 49, 2083–2091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimamura, T.; Sumikura, Y.; Yamazaki, T.; Tada, A.; Kashiwagi, T.; Ishikawa, H.; Matsui, T.; Sugimoto, N.; Akiyama, H.; Ukeda, H. Applicability of the DPPH assay for evaluating the antioxidant capacity of food additives—Inter-laboratory evaluation study. Anal. Sci. 2014, 30, 717–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salihović, M.; Pazalja, M.; Ajanović, A. Antioxidant Activity of Watermelon Seeds Determined by DPPH Assay. Kem. U Ind. Časopis Kemičara Kem. Inženjera Hrvat. 2022, 71, 295–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, C.; Xue, J.; Abbas, S.; Feng, B.; Zhang, X.; Xia, S. Liposome as a Delivery System for Carotenoids: Comparative Antioxidant Activity of Carotenoids As Measured by Ferric Reducing Antioxidant Power, DPPH Assay and Lipid Peroxidation. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2014, 62, 6726–6735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zia, S.; Khan, M.R.; Mousavi Khaneghah, A.; Aadil, R.M. Characterization, bioactive compounds, and antioxidant profiling of edible and waste parts of different watermelon (Citrullus lanatus) cultivars. Biomass Conv. Bioref. 2025, 15, 2171–2183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zia, S.; Khan, M.R.; Shabbir, M.A. An Update on Functional, Nutraceutical and Industrial Applications of Watermelon by-Products: A Comprehensive Review. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 114, 275–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wijeyeratne, Y.D.; Heptinstall, S. Anti-platelet therapy: ADP receptor antagonists. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2011, 72, 647–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jagroop, I.A. Plant extracts inhibit ADP-induced platelet activation in humans: Their potential therapeutic role as ADP antagonists. Purinergic Signal. 2014, 10, 233–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kun, Y.; Ssonko Lule, U.; Xiao-Lin, D. Lycopene: Its Properties and Relationship to Human Health. Food Rev. Int. 2006, 22, 309–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balestrieri, M.L.; De Prisco, R.; Nicolaus, B.; Pari, P.; Moriello, V.S.; Strazzullo, G.; Iorio, E.L.; Servillo, L.; Balestrieri, C. Lycopene in Association with α-Tocopherol or Tomato Lipophilic Extracts Enhances Acyl-Platelet-Activating Factor Biosynthesis in Endothelial Cells during Oxidative Stress. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2004, 36, 1058–1067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teng, C.-M.; Li, H.-L.; Wu, T.-S.; Huang, S.-C.; Huang, T.-F. Antiplatelet Actions of Some Coumarin Compounds Isolated from Plant Sources. Thromb. Res. 1992, 66, 549–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.-L.; Wang, T.-C.; Lee, K.-H.; Tzeng, C.-C.; Chang, Y.-L.; Teng, C.-M. Synthesis of Coumarin Derivatives as Inhibitors of Platelet Aggregation. Helv. Chim. Acta 1996, 79, 651–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunez, D.; Randon, J.; Gandhi, C.; Siafaka-Kapadai, A.; Olson, M.S.; Hanahan, D.J. The inhibition of platelet-activating factor-induced platelet activation by oleic acid is associated with a decrease in polyphosphoinositide metabolism. J. Biol. Chem. 1990, 265, 18330–18338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smal, M.A.; Baldo, B.A. Inhibition of platelet-activating factor (PAF)-induced platelet aggregation by fatty acids from human saliva. Platelets 2022, 33, 562–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shoshan, V.; MacLennan, D.H. Quercetin Interaction with the (Ca2+ + Mg2+)-ATPase of Sarcoplasmic Reticulum. J. Biol. Chem. 1981, 256, 887–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, A.d.S.; de Oliveira, L.S.; Lopes, T.F.; Baldissarelli, J.; Palma, T.V.; Soares, M.S.P.; Spohr, L.; Morsch, V.M.; de Andrade, C.M.; Schetinger, M.R.C.; et al. Effect of Gallic Acid on Purinergic Signaling in Lymphocytes, Platelets, and Serum of Diabetic Rats. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2018, 101, 30–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Lu, H.; Zhu, X.; Wang, W.; Zhang, Z.; Fu, H.; Ma, S.; Luo, Y.; Fu, J. Inhibitory Effects of Luteolin-4’-O-β-D-glucopyranoside on P2Y12 and Thromboxane A2 Receptor-mediated Amplification of Platelet Activation in Vitro. Int. J. Mol. Med. 2018, 42, 615–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsiao, G.; Wang, Y.; Tzu, N.-H.; Fong, T.-H.; Shen, M.-Y.; Lin, K.-H.; Chou, D.-S.; Sheu, J.-R. Inhibitory Effects of Lycopene on in Vitro Platelet Activation and in Vivo Prevention of Thrombus Formation. J. Lab. Clin. Med. 2005, 146, 216–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holy, E.W.; Forestier, M.; Richter, E.K.; Akhmedov, A.; Leiber, F.; Camici, G.G.; Mocharla, P.; Lüscher, T.F.; Beer, J.H.; Tanner, F.C. Dietary α-Linolenic Acid Inhibits Arterial Thrombus Formation, Tissue Factor Expression, and Platelet Activation. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2011, 31, 1772–1780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kharazmi-Khorassani, J.; Ghafarian Zirak, R.; Ghazizadeh, H.; Zare-Feyzabadi, R.; Kharazmi-Khorassani, S.; Naji-Reihani-Garmroudi, S.; Kazemi, E.; Esmaily, H.; Javan-Doust, A.; Banpour, H.; et al. The Role of Serum Monounsaturated Fatty Acids (MUFAs) and Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids (PUFAs) in Cardiovascular Disease Risk. Acta Biomed. Atenei Parm. 2021, 92, e2021049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammad, S.; Pu, S.; Jones, P.J. Current Evidence Supporting the Link Between Dietary Fatty Acids and Cardiovascular Disease. Lipids 2016, 51, 507–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, F.; Imran, A.; Nosheen, F.; Fatima, M.; Arshad, M.U.; Afzaal, M.; Ijaz, N.; Noreen, R.; Mehta, S.; Biswas, S.; et al. Functional Roles and Novel Tools for Improving-Oxidative Stability of Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids: A Comprehensive Review. Food Sci. Nutr. 2023, 11, 2471–2482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajaram, S. Health Benefits of Plant-Derived α-Linolenic Acid123. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2014, 100, 443S–448S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Zhang, H.; Jin, Q.; Wang, X. Effects of Dietary Plant-Derived Low-Ratio Linoleic Acid/Alpha-Linolenic Acid on Blood Lipid Profiles: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Foods 2023, 12, 3005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Lorgeril, M.; Renaud, S.; Mamelle, N.; Salen, P.; Martin, J.L.; Monjaud, I.; Guidollet, J.; Touboul, P.; Delaye, J. Mediterranean Alpha-Linolenic Acid-Rich Diet in Secondary Prevention of Coronary Heart Disease. Lancet Lond. Engl. 1994, 343, 1454–1459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bazán-Salinas, I.L.; Matías-Pérez, D.; Pérez-Campos, E.; Pérez-Campos Mayoral, L.; García-Montalvo, I.A. Reduction of Platelet Aggregation From Ingestion of Oleic and Linoleic Acids Found in Vitis Vinifera and Arachis Hypogaea Oils. Am. J. Ther. 2016, 23, e1315–e1319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stivala, S.; Gobbato, S.; Bonetti, N.; Camici, G.G.; Lüscher, T.F.; Beer, J.H. Dietary alpha-linolenic acid reduces platelet activation and collagen-mediated cell adhesion in sickle cell disease mice. J. Thromb. Haemost. 2022, 20, 375–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freese, R.; Mutanen, M. Alpha-linolenic acid and marine long-chain n-3 fatty acids differ only slightly in their effects on hemostatic factors in healthy subjects. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 1997, 66, 591–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Angelo, S.; Motti, M.L.; Meccariello, R. ω-3 and ω-6 Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids, Obesity and Cancer. Nutrients 2020, 12, 2751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simopoulos, A.P. The Importance of the Omega-6/Omega-3 Fatty Acid Ratio in Cardiovascular Disease and Other Chronic Diseases. Exp. Biol. Med. 2008, 233, 674–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsoupras, A.; Brummell, C.; Kealy, C.; Vitkaitis, K.; Redfern, S.; Zabetakis, I. Cardio-Protective Properties and Health Benefits of Fish Lipid Bioactives; The Effects of Thermal Processing. Mar. Drugs 2022, 20, 187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grover, S.P.; Bergmeier, W.; Mackman, N. Platelet signaling pathways and new inhibitors. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2018, 38, E28–E35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baeza-Jiménez, R.; López-Martínez, L.X.; García-Varela, R.; García, H.S. Lipids in fruits and vegetables: Chemistry and biological activities. In Fruit and Vegetable Phytochemicals: Chemistry and Human Health, 2nd ed.; Wiley-Blackwell: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2017; pp. 423–450. [Google Scholar]

- Reheman, A.; Hawley, M.; Holinstat, M. Regulation of platelet function and thrombosis by omega-3 and omega-6 polyunsaturated fatty acids. Prostaglandins Other Lipid Mediat. 2018, 139, 10–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oppedisano, F.; Macrì, R.; Gliozzi, M.; Musolino, V.; Carresi, C.; Maiuolo, J.; Bosco, F.; Nucera, S.; Caterina Zito, M.; Guarnieri, L.; et al. The Anti-Inflammatory and Antioxidant Properties of n-3 PUFAs: Their Role in Cardiovascular Protection. Biomedicines 2020, 8, 306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Zhang, H.; Hsu-Hage, B.H.H.; Wahlqvist, M.L.; Sinclair, A.J. Original Communication The influence of fish, meat and polyunsaturated fat intakes on platelet phospholipid polyunsaturated fatty acids in male Melbourne Chinese and Caucasian. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2001, 55, 1036–1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, L.; Cao, J.; Mao, Q.; Lu, X.; Zhou, X.; Fan, L. Influence of omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acid-supplementation on platelet aggregation in humans: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Atherosclerosis 2013, 226, 328–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velissaridou, A.; Panoutsopoulou, E.; Prokopiou, V.; Tsoupras, A. Cardio-Protective-Promoting Properties of Functional Foods Inducing HDL-Cholesterol Levels and Functionality. Nutraceuticals 2024, 4, 469–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsoupras, A. The Anti-Inflammatory and Antithrombotic Properties of Bioactives from Orange, Sanguine and Clementine Juices and from Their Remaining By-Products. Beverages 2022, 8, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manikishore, M.; Rathee, S.; Chauhan, A.S.; Patil, U.K. Watermelon Rind: Nutritional Composition, Therapeutic Potential, Environmental Impact, and Commercial Applications in Sustainable Industries. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2025, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vettorazzi, A.; López de Cerain, A.; Sanz-Serrano, J.; Gil, A.G.; Azqueta, A. European Regulatory Framework and Safety Assessment of Food-Related Bioactive Compounds. Nutrients 2020, 12, 613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Samples | Yield for TAC | TLC | TL | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median | Max | Min | Median | Max | Min | Median | Max | Min | |

| Watermelon juice | 0.24 | 0.38 | 0.05 | 0.06 | 0.06 | 0.03 | 0.27 | 0.44 | 0.11 |

| Watermelon by-products | 0.15 | 0.15 | 0.04 | 0.10 | 0.20 | 0.04 | 0.24 | 0.25 | 0.19 |

| Samples | TPC of TACs * | TPC of TLCs * | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median | Min | Max | Median | Min | Max | |

| Watermelon juice | 40.73 | 13.62 | 60.85 | 85.23 | 60.58 | 112.30 |

| Watermelon by-products | 25.92 | 24.34 | 51.62 | 20.65 | 7.74 | 92.57 |

| Samples | TCC of TACs 1 | TCC of TLCs 1 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median | Min | Max | Median | Min | Max | |

| Watermelon juice | 2.88 | 2.80 | 7.78 | 17.30 * | 13.61 | 21.84 |

| Watermelon by-products | 3.14 | 2.83 | 13.62 | 2.49 | 1.40 | 6.84 |

| Samples | ABTS Values of TACs 1 | ABTS Values of TLCs 1 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median | Min | Max | Median | Min | Max | |

| Watermelon juice | 3.70 | 3.60 | 5.60 | 7.79 * | 7.76 | 14.11 |

| Watermelon by-products | 1.33 | 0.59 | 1.76 | 3.85 * | 1.66 | 8.72 |

| Samples | DPPH-TEAC Values of TACs 1 | DPPH-TEAC Values of TLCs 1 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median | Min | Max | Median | Min | Max | |

| Watermelon juice | 0.0049 | 0.0030 | 0.0099 | 0.0190 * | 0.0160 | 0.0380 |

| Watermelon by-products | 0.0034 | 0.0025 | 0.0100 | 0.0046 | 0.0025 | 0.0130 |

| Samples | FRAP Values of TACs 1 | FRAP Values of TLCs 1 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median | Min | Max | Median | Min | Max | |

| Watermelon juice | 2.11 | 1.11 | 4.32 | 1.38 | 0.73 | 1.82 |

| Watermelon by-products | 1.66 | 1.48 | 4.90 | 0.20 * | 0.14 | 0.27 |

| Peak (cm−1) | TACs of Watermelon Juice | TACs of Watermelon By-Products | Bond/Functional Group Correlation |

|---|---|---|---|

| 3200–3500 | + | + | O–H (hydroxyl) bonds, characteristic of this functional group in phenolic compounds, Glycolipids bearing a hydroxyl head group and fatty acids |

| 2850–3000 | + | + | C–H (alkyl), typically from fatty acids and aliphatic compounds like those present in Polar Lipids (PL) |

| 1640–1680 | + | + | Conjugated C=C bonds of polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFA) |

| 1540–1650 | + | + | Conjugated polyene chain, characteristic of carotenoids|C=C stretching |

| 1000–1300 | + | + | P=O stretching characteristic of phosphoglycerolipids |

| 850–900 | + | + | P–O–C characteristic of the bond between the phosphate group and glycerol in phosphoglycerolipids |

| Empirical Name | Fatty Acids | Watermelon Juice (%) | Watermelon By-Products (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pelargonic | C9:0 | ND | 0.10 ± 0.02 |

| Myristic | C14:0 | 0.36 ± 0.04 | 0.40 ± 0.04 |

| Pentadecylic | C15:0 | 0.39 ± 0.03 | 0.38 ± 0.12 |

| Palmitic | C16:0 | 28.40 ± 0.33 | 30.34 ± 0.41 |

| Palmitoleic | C16:1 c9 (n7 MUFA) | 0.88 ± 0.16 | 1.19 ± 0.107 |

| Margaric | C17:0 | ND | 0.89 ± 0.13 |

| Stearic | C18:0 | 20.78 ± 0.36 | 19.21 ±0.15 |

| Oleic | C18:1 c9 (n9 MUFA) | 31.28 ± 0.56 | 15.80 ± 0.22 |

| Linoleic | C18:2 c9,12 (n6 PUFA) | 13.63 ± 0.11 | 16.02 ± 0.15 |

| α Linolenic | C18:3 c9,12,15 (n3 PUFA) | 4.28 ± 0.09 | 14.14 ± 0.26 |

| EPA | C20:5 c5,8,11,14,17 (n3 PUFA) | ND | 0.68 ± 0.01 |

| DHA | C22:6 c4,7,10,13,16,19 (n3 PUFA) | ND | 0.82 ± 0.04 |

| SFA | 49.94 ± 0.58 | 51.35 ± 0.55 * | |

| UFA | 50.10 ± 0.58 | 48.66 ± 0.55 | |

| MUFA | 32.16 ± 0.42 ** | 16.99 ± 0.29 ** | |

| PUFA | 17.91 ± 0.17 | 31.66 ± 0.39 | |

| n3PUFA | 4.28 ± 0.09 | 15.64 ± 0.30 | |

| n6PUFA | 13.63 ± 0.11 | 16.02 ± 0.15 | |

| n6/n3 | 3.19 ± 0.07 | 1.02 ± 0.02 | |

| UFA/SFA | 1.00 ± 0.02 | 0.95 ± 0.02 |

| Main Class of PL | Elution Time (min) | m/z | Representative Molecular Species | Proposed Structures |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PE | 7.6 | 634.8736 | PE O-29:0 | PE O-15:0|14:0 |

| 9.2 | 634.8928 | PE O-29:0 | PE O-15:0|14:0 | |

| 9.2 | 714.844 | PE 34:2 | PE 16:0|18:2 or PE 16:1|18:1 | |

| 9.2 | 714.8397 | PE 34:2 | PE 16:0|18:2 or PE 16:1|18:1 | |

| 10 | 634.8897 | PE O-29:0 | PE O-15:0|14:0 | |

| 10.27 | 634.8903 | PE O-29:0 | PE O-15:0|14:0 | |

| 10.27 | 698.4154 | PE 33:3 | PE 15:0|18:3 | |

| PC | 9.2 | 770.8635 | PC 36:2 | PC 18:1|18:1 |

| 9.6 | 714.8397 | PC O-33:2 | PC O-15:0|18:2 | |

| 9.6 | 770.8613 | PC 36:2 | PC 18:0|18:2 | |

| 10.27 | 714.4099 | PC 32:2 | PC-14:0|18:2 | |

| 10.27 | 770.8603 | PC 36:2 | PC-18:0|18:2 | |

| Mainclass of PL | Elution Time (min) | m/z | Representative Molecular Species | Proposed structures |

| PE | 7.17 | 734.0131 | PE 36:6 | PE 18:3|18:3 |

| 7.55 | 734.015 | PE 36:6 | PE 18:3|18:3 | |

| 7.55 | 820.1884 | PE O-44:12 | PE O-22:6|22:6 | |

| 8.38 | 734.0216 | PE 36:6 | PE 18:3|18:3 | |

| 8.56 | 734.0174 | PE 36:6 | PE 18:3|18:3 | |

| 8.74 | 734.0134 | PE 36:6 | PE 18:3|18:3 | |

| 8.74 | 744.9631 | PE 36:1 | PE 18:0|18:1 | |

| 9.159 | 666.0286 | PE O-31:6;O | PE O-9:0|22:6 | |

| 9.159 | 734.0236 | PE 36:6 | PE 18:3|18:3 | |

| 9.656 | 714.5567 | PE O-35:2 | PE O-17:0|18:2 | |

| 10.245 | 734.3987 | PE 36:6 | PE 18:3|18:3 | |

| PC | 7.17 | 692.1602 | PC 31:6 | PC 9:0|22:6 |

| 7.55 | 666.028 | PC 29:5 | PC 9:0|20:5 | |

| 7.55 | 820.1884 | PC 39:6;O | PC 17:0|22:6 | |

| 7.55 | 744.9631 | PC 34:1 | PC 16:0|18:1 | |

| 7.55 | 750.5295 | PC O-36:5 | PC O-16:0|20:5 | |

| 10.651 | 666.026 | PC 29:5 | PC 9:0|20:5 | |

| 10.817 | 666.0278 | PC 29:5 | PC 9:0|20:5 | |

| 12.177 | 666.028 | PC 29:5 | PC 9:0|20:5 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Nikolakakis, E.; Ofrydopoulou, A.; Shiels, K.; Saha, S.K.; Tsoupras, A. In Vitro Antioxidant, Anti-Platelet and Anti-Inflammatory Natural Extracts of Amphiphilic Bioactives from Organic Watermelon Juice and Its By-Products. Metabolites 2026, 16, 81. https://doi.org/10.3390/metabo16010081

Nikolakakis E, Ofrydopoulou A, Shiels K, Saha SK, Tsoupras A. In Vitro Antioxidant, Anti-Platelet and Anti-Inflammatory Natural Extracts of Amphiphilic Bioactives from Organic Watermelon Juice and Its By-Products. Metabolites. 2026; 16(1):81. https://doi.org/10.3390/metabo16010081

Chicago/Turabian StyleNikolakakis, Emmanuel, Anna Ofrydopoulou, Katie Shiels, Sushanta Kumar Saha, and Alexandros Tsoupras. 2026. "In Vitro Antioxidant, Anti-Platelet and Anti-Inflammatory Natural Extracts of Amphiphilic Bioactives from Organic Watermelon Juice and Its By-Products" Metabolites 16, no. 1: 81. https://doi.org/10.3390/metabo16010081

APA StyleNikolakakis, E., Ofrydopoulou, A., Shiels, K., Saha, S. K., & Tsoupras, A. (2026). In Vitro Antioxidant, Anti-Platelet and Anti-Inflammatory Natural Extracts of Amphiphilic Bioactives from Organic Watermelon Juice and Its By-Products. Metabolites, 16(1), 81. https://doi.org/10.3390/metabo16010081