Development and Validation of a Targeted Metabolomic Tool for Metabotype Classification in Schoolchildren

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

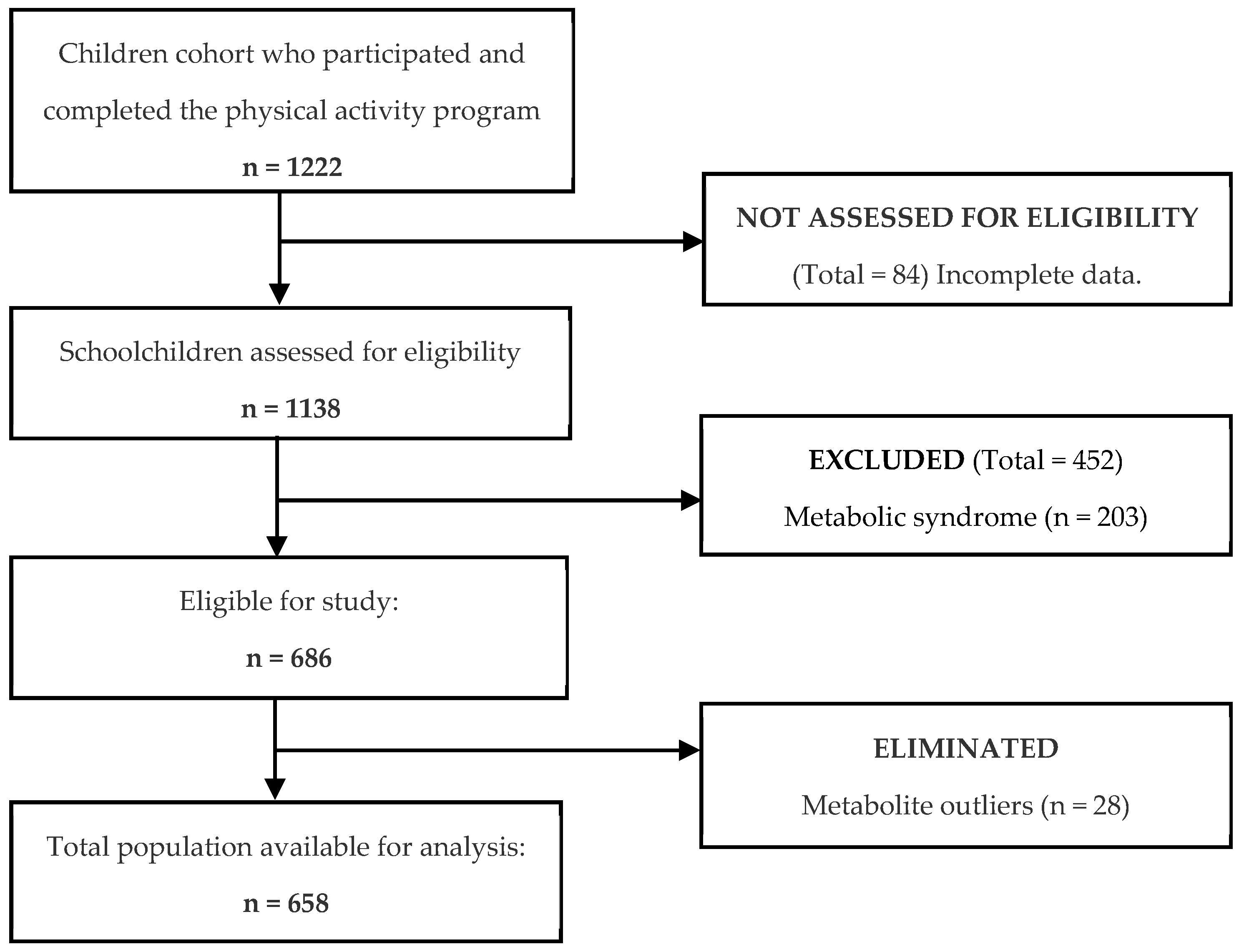

2.1. Study Population

2.2. Study Design

2.3. Sample Size and Effect

2.4. Clinical Measurements

2.5. Targeted Metabolomics

2.6. Statistical Methods

2.7. Bias Control

3. Results

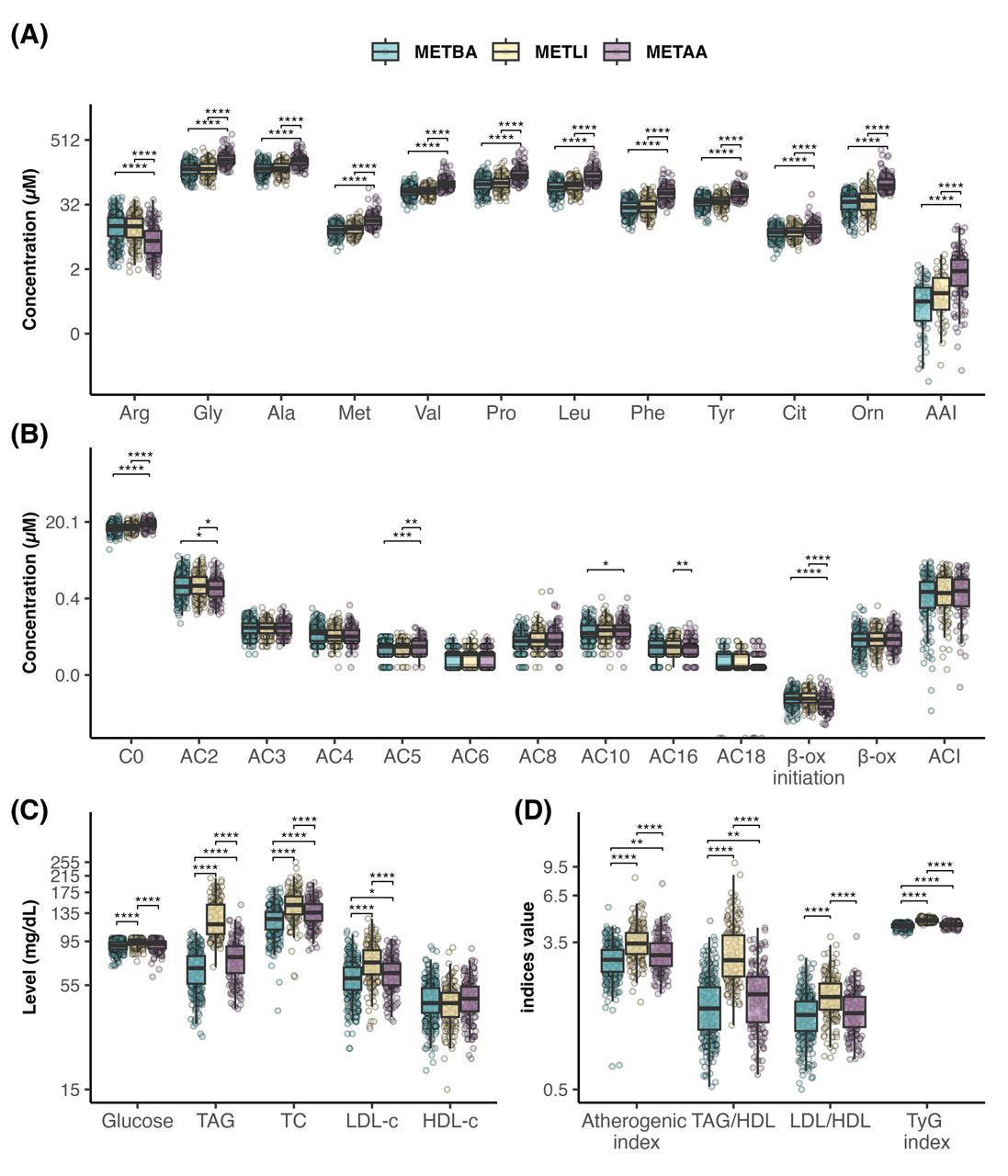

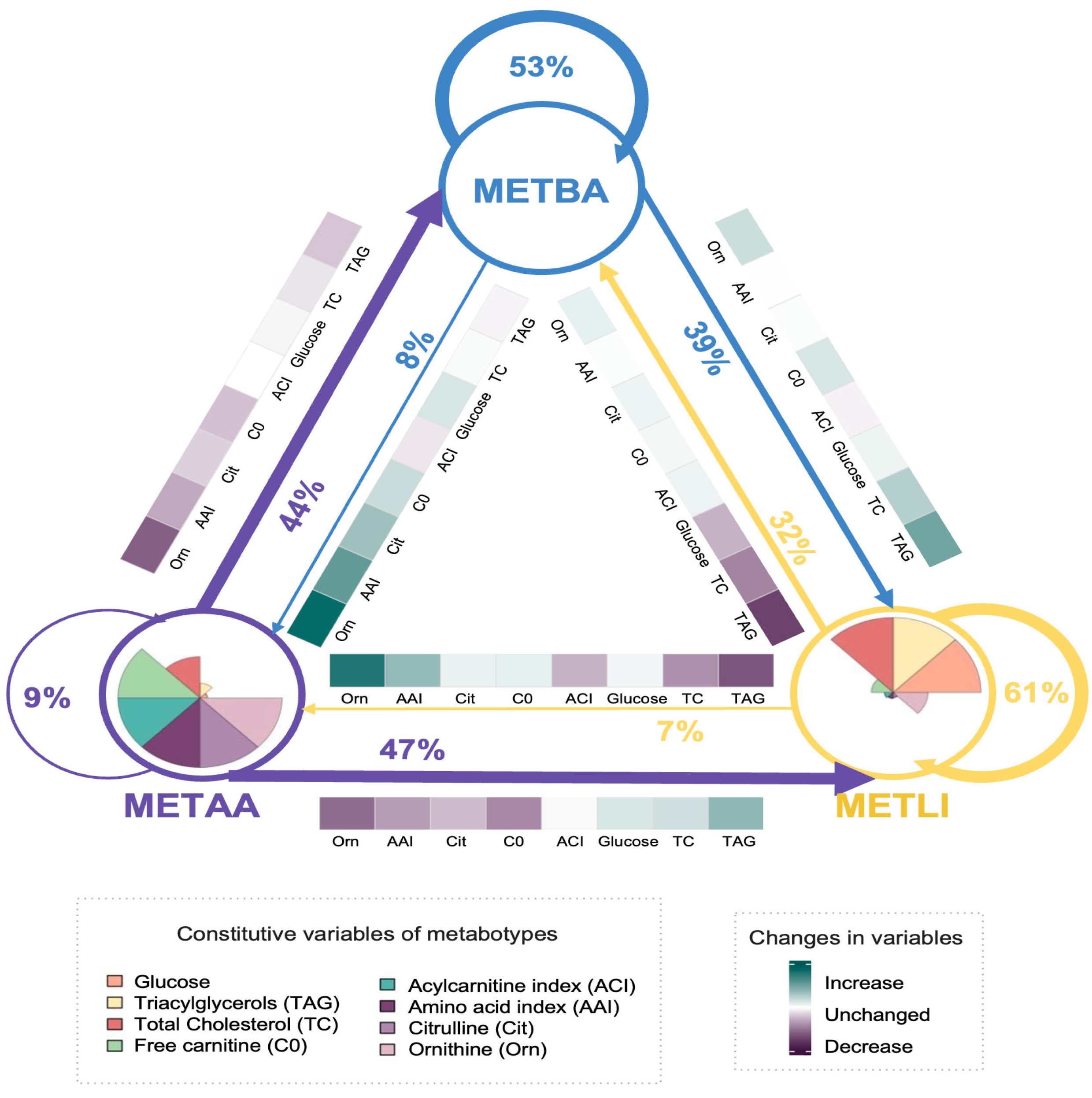

3.1. Phase 1: Development and Internal Validation of the Metabotype Classification Tool

3.2. Phase 2. External Evaluation of the Metabotype Classification Tool

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- German, J.; Hammock, B.; Watkins, S. Metabolomics: Building on a century of biochemistry to guide human health. Metabolomics 2005, 1, 3–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hillesheim, E.; Brennan, L. Metabotyping and its role in nutrition research. Nutr. Res. Rev. 2020, 33, 33–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirwan, J. Translating metabolomics into clinical practice. Nat. Rev. Bioeng. 2023, 1, 228–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trabado, S.; Al-Salameh, A.; Croixmarie, V.; Masson, P.; Corruble, E.; Fève, B.; Colle, R.; Ripoll, L.; Walther, B.; Boursier-Neyret, C.; et al. The human plasma-metabolome: Reference values in 800 French volunteers; impact of cholesterol, gender and age. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0173615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffman, D.; Powell, T.; Barret, E.; Hardy, D. Developmental origins of metabolic diseases. Physiol. Rev. 2021, 101, 739–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linner, A.; Almgren, M. Epigenetic programming-The important first 1000 days. Acta Paediatr 2020, 109, 443–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCormack, S.; Shaham, O.; McCarthy, M.; Deik, A.; Wang, T.; Gerszten, R.; Clish, C.; Mootha, V.; Grinspoon, S.; Fleischman, A. Circulating branched-chain amino acid concentrations are associated with obesity and future insulin resistance in children and adolescents. Pediatr. Obes. 2012, 8, 52–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moran-Ramos, S.; Ocampo-Medina, E.; Gutierrez-Aguilar, R.; Maclás-Kauffer, L.; Villamil-Ramirez, H.; Lopez-Contreras, B.; León-Mimila, P.; Vega-Badillo, J.; Gutierrez-Vidal, R.; Villarruel-Vazquez, R.; et al. An amino acid signature associated with obesity predicts 2-year risk of hypertriglyceridemia in school-age children. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 5607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perng, W.; Gillman, M.W.; Fleisch, A.F.; Michalek, R.D.; Watkins, S.M.; Isganaitis, E.; Patti, M.E.; Oken, E. Metabolomic profiles and childhood obesity. Obesity 2014, 22, 2570–2578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, X.; Gang, Y.; Sun, C.; Han, Q.; Wang, G. Using metabolomics profiles as biomarkers for insulin resistance in childhood obesity: A systematic review. J. Diabetes Res. 2016, 2016, 8160545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchelson, K.; Chathail, M.; Roche, H. Systems biology approaches to inform precision nutrition. Proc. Nutr. Soc. 2023, 82, 208–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Polo-Oteyza, E.; Ancira-Moreno, M.; Rosel-Pech, C.; Sánchez-Mendoza, M.; Salinas-Martínez, V.; Vadillo-Ortega, F. An intervention to promote physical activity in Mexican elementary school students: Building public policy to prevent noncommunicable diseases. Nutr. Rev. 2017, 75, 70–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cook, S.; Weitzman, M.; Auinger, P.; Nguyen, M.; Dietz, W. Prevalence of a metabolic syndrome phenotype in adolescents: Findings from the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1988–1994. Arch. Pediatr. Adolesc. Med. 2003, 157, 821–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. WHO Child Growth Standards: Length/Height-for-Age, Weight-for-Age, Weight-for-Length, Weight-for-Height and Body Mass Index-for-Age: Methods and Development; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2006; p. 312. [Google Scholar]

- WHO. WHO Child Growth Standards: Growth Velocity Based on Weight, Length and Head Circumference: Methods and Development; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2009; pp. 1–240. [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez, J.; Redden, D.; Pietrobelli, A.; Allison, D. Waist circumference percentiles in nationally representative samples of African-American, European-American, and Mexican-American children and adolescents. J. Pediatr. 2004, 145, 439–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National High Blood Pressure Education Program Working Group on High Blood Pressure in Children and Adolescents. The fourth report on the diagnosis, evaluation, and treatment of high blood pressure in children and adolescents. Pediatrics 2004, 114, 555–576. [CrossRef]

- Friedewald, W.; Levy, R.; Fredrickson, D. Estimation of the concentration of low-density lipoprotein cholesterol in plasma, without the use of the preparative ultracentrifuge. Clin. Chem. 1972, 18, 499–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castelli, W.; Doyle, J.; Gordon, T.; Hames, C.; Hjortland, M.; Hulley, S.; Kagan, A.; Zukel, W. HDL cholesterol and cardiovascular mortality: The Framingham Study. Circulation 1977, 56, 844–849. [Google Scholar]

- Dobiasova, M. Atherogenic index of plasma as a significant predictor of cardiovascular risk: From research to practice. Clin. Biochem. 2001, 34, 583–588. [Google Scholar]

- Guerrero-Romero, F.; Simental-Mendia, L.; Gonzalez-Ortiz, M.; Martinez-Abundis, E.; Ramos-Zavala, M.; Hernandez-Gonzalez, S.; Jacques-Camarena, O. The product of triglycerides and glucose, a simple measure of insulin sensitivity. Comparison with the euglycaemic-hyperinsulinaemic clamp. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2010, 95, 3347–3351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero-Ibarguengoitia, M.; Vadillo-Ortega, F.; Enrique-Caballero, A.; Ibarra-Gonzalez, I.; Herrera-Rosas, A.; Serratos-Canales, M.; León-Hernandez, M.; Gonzalez-Chavez, A.; Mummidi, S.; Duggirala, R.; et al. Family history and obesity in youth, their effect on acylcarnitine/aminoacids metabolomics and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD). Structural equation modeling approach. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0193138. [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki, Y.; Kido, J.; Matsumoto, S.; Shimizu, K.; Nakamura, K. Associations among amino acid, lipid, and glucose metabolic profiles in childhood obesity. BMC Pediatr. 2019, 19, 273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Lancet Diabetes & Endocrinology Commision; Rubino, F.; Cummings, D.; Eckel, R.; Cohen, R.; Wilding, J.; Brown, W.; Stanford, F. Definition and diagnostic criteria of clinical obesity. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2025, 13, 221–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shah, A.; Wondisford, E. Gluconeogenesis flux in metabolic disease. Annu. Rev. Nutr. 2023, 43, 153–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Handakas, E.; Ho Lau, C.; Alfano, R.; Chatzi, V.; Plusquin, M.; Vineis, P.; Robinson, O. A systematic review of metabolomic studies of childhood obesity: State of the evidence for metabolic determinants and consequences. Obes. Rev. 2021, 23, 13384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmer, R.; Rees, D.; Ashton, H.; Moncada, S. L-arginine is the physiological precursor for the formation of nitric oxide in endothelium-dependent relaxation. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1988, 153, 1251–1256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koay, Y.; Stanton, K.; Kienzle, V.; Li, M.; Yang, J.; Celermajer, D.; O’Sullivan, J. Effect of chronic exercise in healthy young male adults: A metabolomic analysis. Cardiovasc. Res. 2021, 117, 613–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garibay-Nieto, N.; Pedraza-Escudero, K.; Omaña-Guzman, I.; Garces-Hernandez, M.; Villanueva-Ortega, E.; Flores-Torres, M.; Perez-Hernandez, J.; Leon-Hernandez, M.; Laresgoiti-Servitje, E.; Palacios-Gonzalez, B.; et al. Metabolic phenotype of hepatic steatosis and fibrosis in Mexican children living with obesity. Medicina 2023, 59, 1785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estrada-Gutierrez, G.; Zambrano, E.; Polo-Oteyza, E.; Cardona-Perez, A.; Vadillo-Ortega, F. Intervention during the first 1000 days in Mexico. Nutr. Rev. 2020, 78, 80–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Median (IQR) (n = 658) |

|---|---|

| Sex, n (%) | |

| Girls | 337 (51) |

| Boys | 321 (49) |

| Age (y) | 8.97 (7.87, 9.90) |

| Weight (kg) | 28 (23, 34) |

| Height (cm) | 129 (123, 137) |

| Waist circumference (cm) | 60 (55, 67) |

| Waist to height ratio (cm) | 0.47 (0.44, 0.51) |

| BMI (kg/m2 ) | 16.40 (15.06, 18.80) |

| BMI for age (z score) | 0.22 (−0.58, 1.15) |

| BMIfor age, n (%) | |

| Severe thinness | 1 (0) |

| Thinness | 10 (2) |

| Normal weight | 454 (69) |

| Overweight | 138 (21) |

| Obesity | 55 (8) |

| Blood pressure (mm Hg) | |

| Systolic | 105 (98, 112) |

| Diastolic | 63 (56, 70) |

| Blood pressure (percentile) | |

| Systolic | 75 (46, 90) |

| Diastolic | 64 (46,84) |

| METBA (n = 306) | METLI (n = 192) | METAA (n = 160) | p-Value a | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex, n (%) | ||||

| Girls | 148 (48) | 109 (57) | 80 (50) | 0.2 |

| Boys | 158 (52) | 83 (43) | 80 (50) | |

| Age (y) b | 9.27 (8.07, 10.02) | 9.15 (8.03, 9.97) | 8.21 (7.32, 9.37) | <0.001 |

| Weight (kg) b | 28 (24, 35) | 28 (24, 33) | 26 (22, 31) | 0.004 |

| Height (cm) b | 131 (124, 138) | 130 (123, 138) | 126 (121, 133) | <0.001 |

| Waist Circumference (cm) b | 61 (55, 69) | 60 (55, 66) | 59 (54, 65) | 0.08 |

| Waist to Height ratio c | 0.48 (0.05) | 0.47 (0.04) | 0.48 (0.05) | 0.11 |

| BMI (kg/m2) c | 17.28 (2.94) | 16.81 (2.39) | 16.78 (2.51) | 0.2 |

| BMI for age (z-score) c | 0.34 (1.28) | 0.18 (1.11) | 0.28 (1.16) | 0.3 |

| BMI for age, n (%) | ||||

| Severe thinness | 1 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0.05 |

| Thinness | 7 (2) | 1 (1) | 2 (1) | |

| Normal weight | 191 (62) | 147 (77) | 116 (73) | |

| Overweight | 79 (26) | 31 (16) | 28 (18) | |

| Obesity | 28 (9) | 13 (7) | 14 (9) | |

| Blood pressure (mm Hg) b | ||||

| Systolic | 104 (97, 112) | 104 (95, 111) | 107 (101, 113) | 0.004 |

| Diastolic | 62 (56, 70) | 63 (56, 68) | 64 (58, 71) | 0.2 |

| Blood pressure (percentile) b | ||||

| Systolic | 72 (46, 90) | 71 (41, 88) | 82 (65, 93) | <0.001 |

| Diastolic | 61 (43, 84) | 63 (43, 82) | 74 (50, 88) | 0.02 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Hernández-Ramírez, S.K.; Velázquez-Trejo, D.A.; Sandoval-Colín, E.; Fresno, C.; Flores-Torres, M.; Polo-Oteyza, E.; Garcés-Hernández, M.J.; Garibay-Nieto, N.; Ibarra-González, I.; Vela-Amieva, M.; et al. Development and Validation of a Targeted Metabolomic Tool for Metabotype Classification in Schoolchildren. Metabolites 2026, 16, 44. https://doi.org/10.3390/metabo16010044

Hernández-Ramírez SK, Velázquez-Trejo DA, Sandoval-Colín E, Fresno C, Flores-Torres M, Polo-Oteyza E, Garcés-Hernández MJ, Garibay-Nieto N, Ibarra-González I, Vela-Amieva M, et al. Development and Validation of a Targeted Metabolomic Tool for Metabotype Classification in Schoolchildren. Metabolites. 2026; 16(1):44. https://doi.org/10.3390/metabo16010044

Chicago/Turabian StyleHernández-Ramírez, Sheyla Karina, Diego Arturo Velázquez-Trejo, Eduardo Sandoval-Colín, Cristóbal Fresno, Mariana Flores-Torres, Ernestina Polo-Oteyza, María José Garcés-Hernández, Nayely Garibay-Nieto, Isabel Ibarra-González, Marcela Vela-Amieva, and et al. 2026. "Development and Validation of a Targeted Metabolomic Tool for Metabotype Classification in Schoolchildren" Metabolites 16, no. 1: 44. https://doi.org/10.3390/metabo16010044

APA StyleHernández-Ramírez, S. K., Velázquez-Trejo, D. A., Sandoval-Colín, E., Fresno, C., Flores-Torres, M., Polo-Oteyza, E., Garcés-Hernández, M. J., Garibay-Nieto, N., Ibarra-González, I., Vela-Amieva, M., Estrada-Gutierrez, G., & Vadillo-Ortega, F. (2026). Development and Validation of a Targeted Metabolomic Tool for Metabotype Classification in Schoolchildren. Metabolites, 16(1), 44. https://doi.org/10.3390/metabo16010044