Exploration of Key Flavor Compounds in Five Grilled Salmonid Species by Integrating Volatile Profiling and Sensory Evaluation

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Reagents

2.3. Sensory Evaluation

2.4. Analysis of Volatile Compounds

2.4.1. Detection and Identification of Volatile Compounds Using GC/Mass Spectrometry (GC/MS)

2.4.2. GC/O Analysis

2.5. Multivariate Analysis

2.6. Quantification of Key Flavor Candidates

2.6.1. Quantification of Key Flavor Candidates Other than TMA

2.6.2. Quantification of TMA

2.7. Additive Tests

3. Results

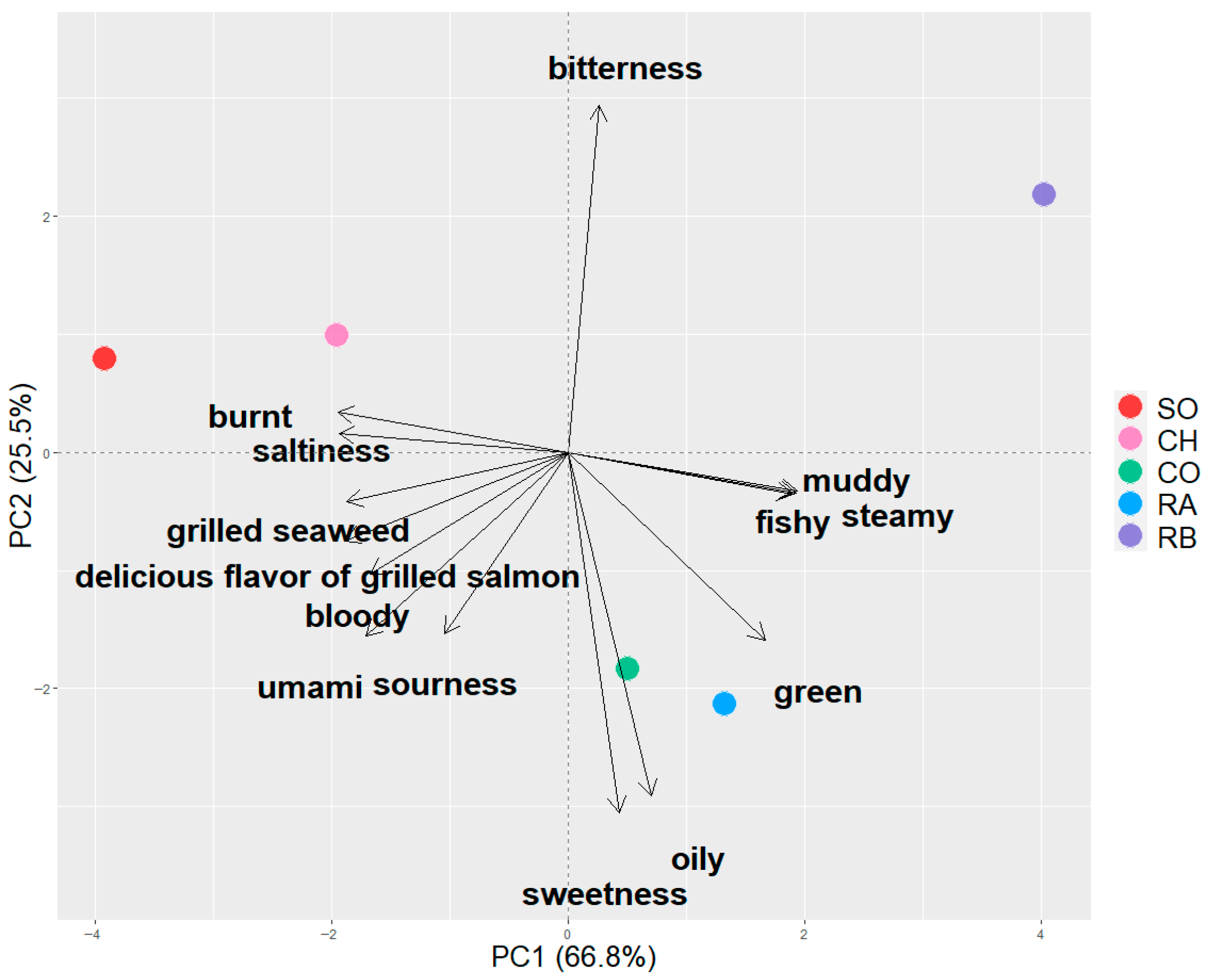

3.1. Sensory Characteristics of Grilled Salmonid Species

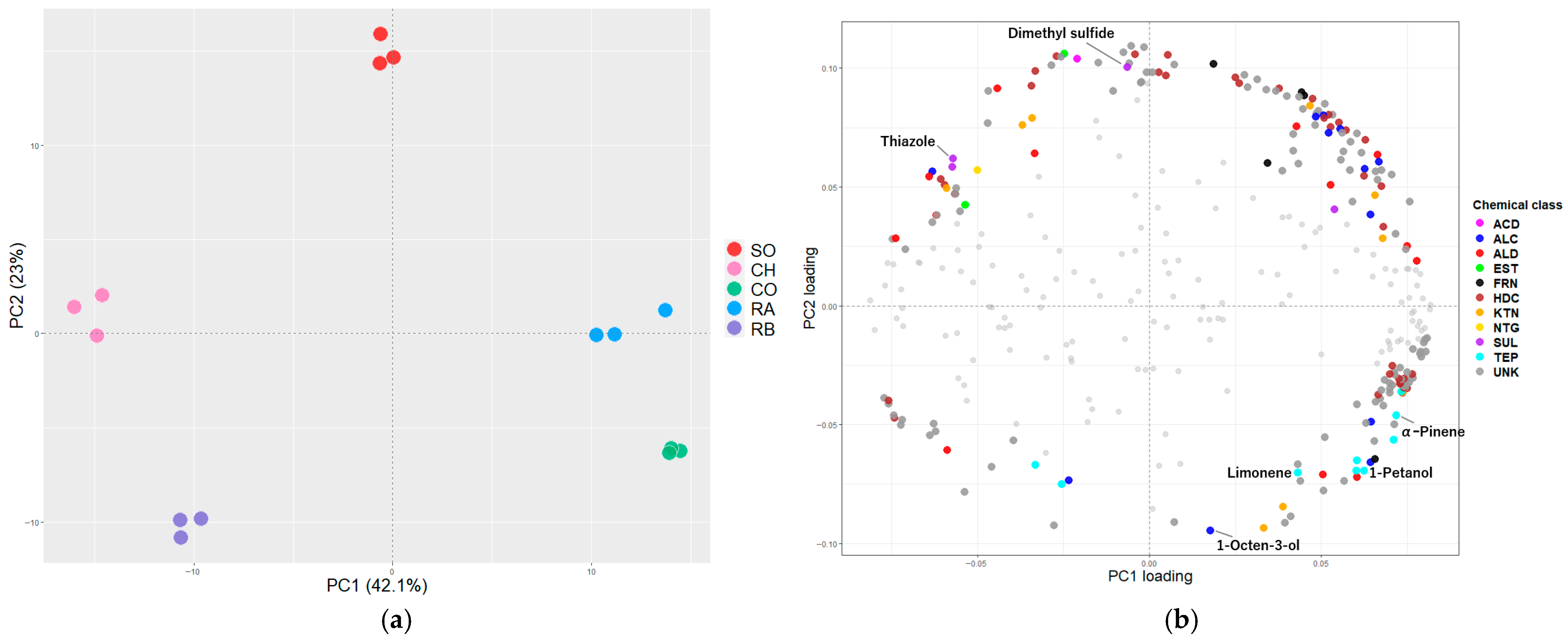

3.2. Volatile Profiles of Grilled Salmonid Species

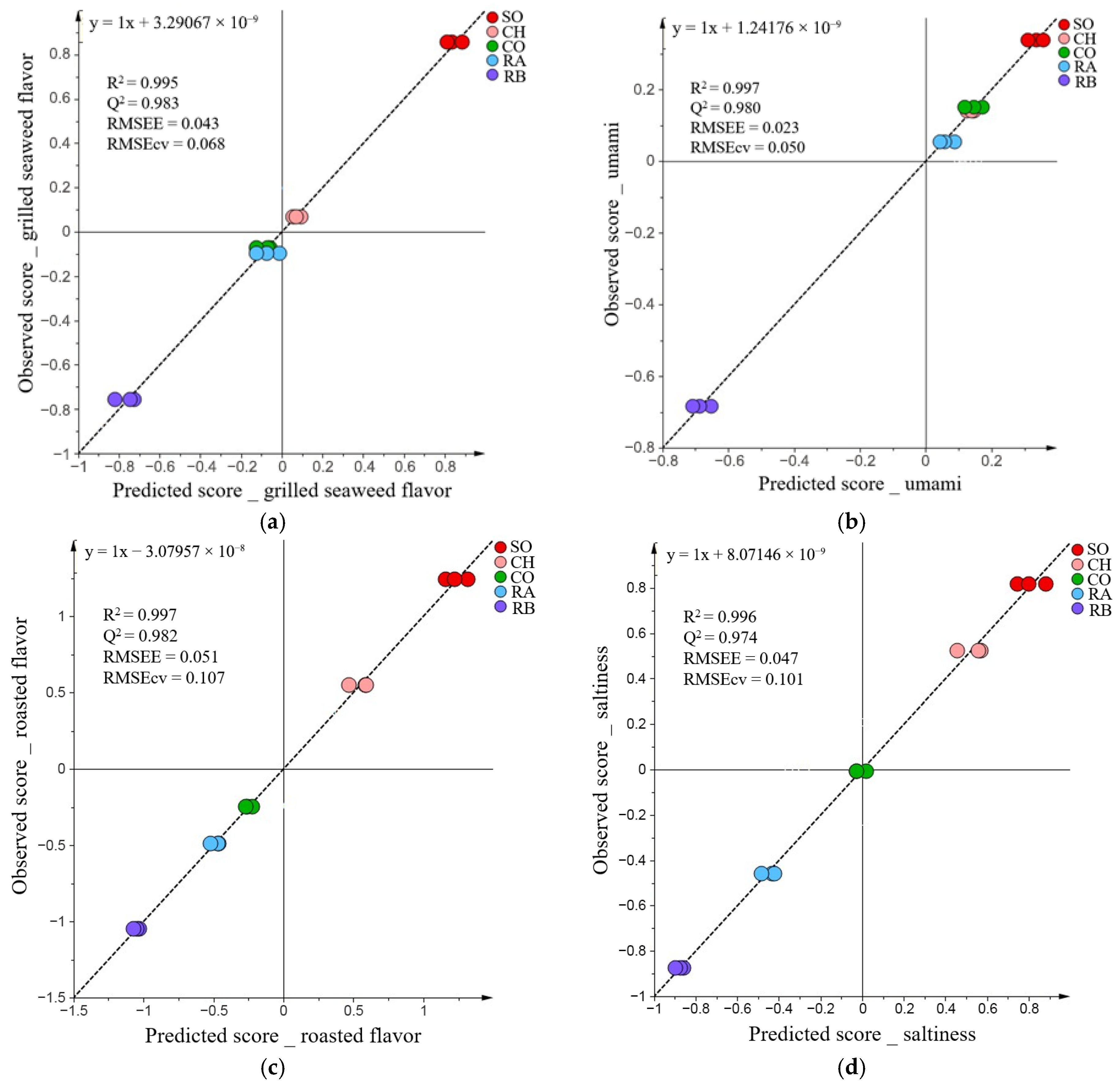

3.3. Correlation Analysis of Sensory Attributes and Volatile Profiles

3.4. Identification of Active Aroma Compounds Using GC/O Analysis

3.5. Quantification of Key Flavor Candidates

3.6. Verification of the Effects of Key Flavor Candidates by Additive Test

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| GC/MS | Gas chromatography/mass spectrometry |

| OPLSR | Orthogonal partial least squares regression |

| GC/O | Gas chromatography/olfactometry |

| PCA | Principal component analysis |

| FAO | Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations |

| MAFF | Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry, and Fisheries |

| SO | Sockeye salmon |

| CH | Chum salmon |

| CO | Coho salmon |

| RA | Rainbow trout cultured in salt water |

| RB | Rainbow trout cultured in freshwater |

| TMA | Trimethylamine |

| SPME | Solid-phase microextraction |

| QC | quality control |

| RI | Retention index |

| VIP | Variable importance in the projection |

| RMSEE | Root mean square error of estimation |

| SIM | Selected ion monitoring |

| TA | Test A |

| TB | Test B |

| ΔRS | Rank sum differences |

| LSD | The least significant difference |

| OAVs | Odor activity values |

| PUFA | Polyunsaturated fatty acids |

| MUFA | Monounsaturated fatty acids |

| TMAO | Trimethylamine oxide |

References

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO). The State of World Fisheries and Aquaculture Blue Transformation in Action. 2024. Available online: https://openknowledge.fao.org/server/api/core/bitstreams/a10e81b3-3fbd-4393-b7b6-6a926915a19a/content (accessed on 8 December 2025).

- Ferreira, V.C.; Morcuende, D.; Madruga, M.S.; Hernández-López, S.H.; Silva, F.A.; Ventanas, S.; Estévez, M. Effect of pre-cooking methods on the chemical and sensory deterioration of ready-to-eat chicken patties during chilled storage and microwave reheating. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2016, 53, 2760–2769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Song, H. Variation of aroma components during frozen storage of cooked beef balls by SPME and SAFE coupled with GC-O-MS. J. Food Process. Preserv. 2021, 45, e15036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pongsetkul, J.; Benjakul, S.; Boonchuen, P. Changes in volatile compounds and quality characteristics of salted shrimp paste stored in different packaging containers. Fermentation 2022, 8, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, M.; Liang, F.; Cui, S.; Mao, B.B.; Huang, X.H.; Qin, L. Insights into the effects of steaming on organoleptic quality of salmon (Salmo salar) integrating multi-omics analysis and electronic sensory system. Food Chem. 2024, 434, 137372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girard, B.; Durance, T. Headspace volatiles of sockeye and pink salmon as affected by retort process. J. Food Sci. 2000, 65, 34–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Methven, L.; Tsoukka, M.; Oruna-Concha, M.J.; Parker, J.K.; Mottram, D.S. Influence of sulfur amino acids on the volatile and nonvolatile components of cooked salmon (Salmo salar). J. Agric. Food Chem. 2007, 55, 1427–1436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jónsdóttir, R.; Ólafsdóttir, G.; Chanie, E.; Haugen, J.E. Volatile compounds suitable for rapid detection as quality indicators of cold smoked salmon (Salmo salar). Food Chem. 2008, 109, 184–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varlet, V.; Knockaert, C.; Prost, C.; Serot, T. Comparison of odor-active volatile compounds of fresh and smoked salmon. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2006, 54, 3391–3401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fomena Temgoua, N.S.; Sun, Z.; Okoye, C.O.; Pan, H. Fatty acid profile, physicochemical composition, and sensory properties of Atlantic salmon fish (Salmo salar) during different culinary treatments. J. Food Qual. 2022, 2022, 7425142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, M.; Zhou, Z.; Wang, B.; Zhang, Y.; Huang, X.; Qin, L. Investigating the quality discrepancy between different salmon and tracing the key lipid precursors of roasted flavor. Food Chem. 2025, 463, 141452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gulliksen, H. A least squares solution for paired comparisons with incomplete data. Psychometrika 1956, 21, 125–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsugawa, H.; Cajka, T.; Kind, T.; Ma, Y.; Higgins, B.; Ikeda, K.; Kanazawa, M.; VanderGheynst, J.; Fiehn, O.; Arita, M. MS-DIAL: Data-independent MS/MS deconvolution for comprehensive metabolome analysis. Nat. Methods 2015, 12, 523–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wimonmuang, K.; Lee, Y.S. Absolute contents of aroma-affecting volatiles in cooked rice determined by one-step rice cooking and volatile extraction coupled with standard-addition calibration using HS-SPME/GC–MS. Food Chem. 2024, 440, 138271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, S.T.; Yao, M.W.; Wong, Y.C.; Wong, T.; Mok, C.S.; Sin, D.W. Evaluation of chemical indicators for monitoring freshness of food and determination of volatile amines in fish by headspace solid-phase microextraction and gas chromatography-mass spectrometry. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2006, 224, 67–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, S.W.C.; Chan, B.T.P. Trimethylamine oxide, dimethylamine, trimethylamine and formaldehyde levels in main traded fish species in Hong Kong. Food Addit. Contam. Part B 2009, 2, 44–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Böttcher, S.; Steinhäuser, U.; Drusch, S. Off-flavour masking of secondary lipid oxidation products by pea dextrin. Food Chem. 2015, 169, 492–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farmer, L.J.; McConnell, J.M.; Kilpatrick, D.J. Sensory characteristics of farmed and wild Atlantic salmon. Aquaculture 2000, 187, 105–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yueqi, A.; Qiufeng, R.; Li, W.; Xuezhen, Z.; Shanbai, X. Comparison of volatile aroma compounds in commercial surimi and their products from freshwater fish and marine fish and aroma fingerprints establishment based on metabolomics analysis methods. Food Chem. 2024, 433, 137308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexander, D.L.; Tropsha, A.; Winkler, D.A. Beware of R2: Simple, unambiguous assessment of the prediction accuracy of QSAR and QSPR models. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2015, 55, 1316–1322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, P.; Norris, K. Near-Infrared Technology in the Agricultural and Food Industries; American Association of Cereal Chemists, Inc.: St. Paul, MN, USA, 1987; pp. 143–167. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, R.; Liu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Bai, C.; Jiang, Y.; Yuan, M.; Zhao, L.; Chen, L. Characterization of the flavor profile of four major Chinese carps using HS-SPME-GC–MS combined with ultra-fasted gas chromatography-electronic nose. Food Chem. 2025, 463, 141264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, W.; Che, X.; Ma, P.; Chen, M.; Huang, X. Aroma formation, release, and perception in aquatic products processing: A review. Foods 2025, 14, 2651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trygg, J.; Wold, S. Orthogonal projections to latent structures (O-PLS). J. Chemom. 2002, 16, 119–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schiffman, S.S.; Bennett, J.L.; Raymer, J.H. Quantification of odors and odorants from swine operations in North Carolina. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2001, 108, 213–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cengiz, N.; Guclu, G.; Kelebek, H.; Selli, S. GC–MS-olfactometric characterization of key odorants in rainbow trout by the application of aroma extract dilution analysis: Understanding locational and seasonal effects. Food Chem. 2023, 407, 135137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podduturi, R.; Petersen, M.A.; Mahmud, S.; Rahman, M.M.; Jørgensen, N.O. Potential contribution of fish feed and phytoplankton to the content of volatile terpenes in cultured pangasius (Pangasianodon hypophthalmus) and tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus). J. Agric. Food Chem. 2017, 65, 3730–3736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunyaboon, S.; Thumanu, K.; Park, J.W.; Khongla, C.; Yongsawatdigul, J. Evaluation of lipid oxidation, volatile compounds and vibrational spectroscopy of silver carp (Hypophthalmichthys molitrix) during ice storage as related to the quality of its washed mince. Foods 2021, 10, 495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Yuan, L.; Weng, L.; Yu, C.H.; Peng, B.; Tu, Z. Integration of lipidomics and flavoromics reveals the lipid-flavor transformation mechanism of fish oil from silver carp visceral with different enzymatic hydrolysis. Food Chem. 2025, 477, 143507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Varlet, V.; Prost, C.; Serot, T. Volatile aldehydes in smoked fish: Analysis methods, occurence and mechanisms of formation. Food Chem. 2007, 105, 1536–1556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammer, M.; Schieberle, P. Model studies on the key aroma compounds formed by an oxidative degradation of ω-3 fatty acids initiated by either copper (II) ions or lipoxygenase. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2013, 61, 10891–10900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Dalali, S.; Li, C.; Xu, B. Effect of frozen storage on the lipid oxidation, protein oxidation, and flavor profile of marinated raw beef meat. Food Chem. 2022, 376, 131881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javed, H.U.; Wang, D.; Abdullah; Hasan, M.; Zeng, L.Y.; Lan, Y.; Shi, Y.; Duan, C.-Q. Interrogating raisin associated unsaturated fatty acid derived volatile compounds using HS–SPME with GC–MS. Foods 2023, 12, 428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grebenteuch, S.; Kanzler, C.; Klaußnitzer, S.; Kroh, L.W.; Rohn, S. The formation of methyl ketones during lipid oxidation at elevated temperatures. Molecules 2021, 26, 1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benet, I.; Guàrdia, M.D.; Ibañez, C.; Solà, J.; Arnau, J.; Roura, E. Analysis of SPME or SBSE extracted volatile compounds from cooked cured pork ham differing in intramuscular fat profiles. LWT–Food Sci. Technol. 2015, 60, 393–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, Y.; Qian, Y.L.; Alcazar Magana, A.; Xiong, S.; Qian, M.C. Comparative characterization of aroma compounds in silver carp (Hypophthalmichthys molitrix), pacific whiting (Merluccius productus), and alaska pollock (Theragra chalcogramma) surimi by aroma extract dilution analysis, odor activity value, and aroma recombination studies. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2020, 68, 10403–10413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Yuan, L.; Liu, H.; Liu, H.; Zhou, Y.; Li, M.; Gao, R. Analysis of the changes of volatile flavor compounds in a traditional Chinese shrimp paste during fermentation based on electronic nose, SPME-GC-MS and HS-GC-IMS. Food Sci. Hum. Wellness 2023, 12, 173–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, X.; Li, S.; Liu, Y.; Li, J.; Dong, X.; Du, M.; Jiang, P. The dynamic changes of flavor characteristics of sea cucumber (Apostichopus japonicus) during puffing revealed by GC–MS combined with HS-GC-IMS. Food Chem. X 2024, 23, 101709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sato, Y.; Takagi, S.; Inomata, E.; Agatsuma, Y. Odor-active volatile compounds from the gonads of the sea urchin Mesocentrotus nudus in the wild in Miyagi Prefecture, Tohoku, Japan. Food Nutr. Sci. 2019, 10, 860–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avigan, J.; Blumer, M. On the origin of pristane in marine organisms. J. Lipid Res. 1968, 9, 350–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blumer, M.; Mullin, M.M.; Thomas, D.W. Pristane in the marine environment. Helgoländer Wiss. Meeresunters. 1964, 10, 187–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Requeni, P.; Mingarro, M.; Kirchner, S.; Calduch-Giner, J.A.; Médale, F.; Corraze, G.; Panserat, S.; Martin, S.; Houlihan, D.; Kaushik, S.; et al. Effects of dietary amino acid profile on growth performance, key metabolic enzymes and somatotropic axis responsiveness of gilthead sea bream (Sparus aurata). Aquaculture 2003, 220, 749–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turchini, G.M.; Hermon, K.M.; Francis, D.S. Fatty acids and beyond: Fillet nutritional characterisation of rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) fed different dietary oil sources. Aquaculture 2018, 491, 391–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wijekoon, M.P.; Parrish, C.C.; Mansour, A. Effect of dietary substitution of fish oil with flaxseed or sunflower oil on muscle fatty acid composition in juvenile steelhead trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) reared at varying temperatures. Aquaculture 2014, 433, 74–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pu, D.; Cao, B.; Xu, Z.; Zhang, L.; Meng, R.; Chen, J.; Sun, B.; Zhang, Y. Decoding of the enhancement of saltiness perception by aroma-active compounds during Hunan Larou (smoke-cured bacon) oral processing. Food Chem. 2025, 463, 141029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.; Sun, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Wang, W.; Blank, I.; Liu, S.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Liu, Y. Key aroma compounds associated with umami perception of MSG in fried Takifugu obscurus liver. Food Res. Int. 2024, 196, 114954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shepherd, G.M. Smell images and the flavour system in the human brain. Nature 2006, 444, 316–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toda, Y.; Nakagita, T.; Hirokawa, T.; Yamashita, Y.; Nakajima, A.; Narukawa, M.; Ishimaru, Y.; Uchida, R.; Misaka, T. Positive/Negative Allosteric Modulation Switching in an Umami Taste Receptor (T1R1/T1R3) by a Natural Flavor Compound, Methional. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 11796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niimi, J.; Eddy, A.I.; Overington, A.R.; Heenan, S.P.; Silcock, P.; Bremer, P.J.; Delahunty, C.M. Aroma–Taste Interactions between a Model Cheese Aroma and Five Basic Tastes in Solution. Food Qual. Prefer. 2014, 31, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Wu, X.; Shi, Y.; Qu, F.; Qi, D.; Qian, W.; Zhang, X.; Hu, J. Identification of key odorants responsible for the seaweed-like aroma quality of Shandong matcha. Food Res. Int. 2025, 204, 115945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Zhao, Y.; Zeng, M.; Xu, X. Research progress of fishy odor in aquatic products: From substance identification, formation mechanism, to elimination pathway. Food Res. Int. 2024, 178, 113914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Attribute | VIP | Coefficient |

|---|---|---|

| grilled seaweed flavor | 1.26 | 0.1693 |

| umami | 1.21 | 0.1335 |

| muddy flavor | 1.21 | −0.1300 |

| steamy flavor | 1.21 | −0.1317 |

| burnt flavor | 1.20 | 0.1184 |

| fishy | 1.20 | −0.1395 |

| saltiness | 1.19 | 0.0967 |

| bloody flavor | 1.09 | 0.0654 |

| green flavor | 0.90 | −0.0618 |

| sourness | 0.69 | −0.0123 |

| bitterness | 0.48 | −0.1091 |

| oily | 0.14 | 0.0559 |

| sweetness | 0.04 | 0.0744 |

| No. | Compounds | Identification Method * | Odor Description by GC/O | VIP by OPLSR ** | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Grilled Seaweed | Umami | Roasted | Saltiness | ||||

| 7 | Acetaldehyde | MS, RI, STD | Fruity, Sweet | 1.73 | 2.05 | 1.50 | 1.65 |

| 11 | Dimethyl sulfide | MS, RI, STD | Pungent, Seaweed | 1.80 | 1.08 | 1.76 | 1.62 |

| 15 | TMA | MS, RI, STD | Tuna | 1.37 | 1.42 | ||

| 17 | Propanal | MS, RI, STD | Green, Fruity | 1.31 | 1.46 | ||

| 21 | 2-Methylpropanal | MS, RI, STD | Roasted | 1.17 | 1.35 | 1.60 | |

| 57 | Unknown | - | Roasted | 1.81 | 1.37 | 1.47 | 1.33 |

| 72 | 3-Pentanone | MS, RI, STD | Yogurt | 1.04 | |||

| 107 | 2-Ethyl-5-methylfuran | MS | Roasted | 2.02 | 1.81 | 1.88 | 1.89 |

| 109 | 1-Propanol | MS, RI, STD | Vinyl | 1.26 | 1.39 | ||

| 117 | S-Methyl Thioacetate | MS, RI, STD | Fermentation | 1.07 | 1.62 | 1.74 | |

| 122 | 2,3-Pentanedione | MS, RI, STD | Yogurt | 1.79 | 1.80 | 1.44 | 1.47 |

| 163 | 2-Ethyl-2-butenal | MS, RI | Paint | 1.14 | |||

| 217 | Cyclohexanone | MS, RI, STD | Vinyl | 1.09 | |||

| 218 | cis-2-(2-Pentenyl) furan | MS | Mushrooms | 1.14 | 1.60 | ||

| 222 | trans-2-Penten-1-ol | MS, RI | Green | 1.25 | 1.24 | ||

| 238 | trans-3-Hexen-1-ol | MS, RI, STD | Paint | 1.48 | 1.43 | 1.04 | |

| 243 | cis-3-Hexen-1-ol | MS, RI, STD | Green, Grilled fish | 1.33 | 1.25 | ||

| 248 | 2-Nonanone | MS, RI, STD | Green, Roasted | 1.40 | 1.52 | ||

| 267 | 1-Heptanol | MS, RI, STD | Green, Grilled fish | 1.08 | |||

| 269 | trans, cis-2,4-Heptadienal | MS, RI | Grilled fish | 1.12 | |||

| 277 | trans, trans-2,4-Heptadienal | MS, RI, STD | Vinyl | 1.13 | |||

| 300 | 2,6,10,14-Tetramethylpentadecane | MS, RI, STD | Roasted | 1.39 | 1.54 | ||

| 315 | Unknown | - | Cotton candy | 1.42 | 1.56 | ||

| No. | Compounds Name | Concentration (μg/kg) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| SO | CO | ||

| 7 | Acetaldehyde | 7900.42 ± 545.09 b | 9626.06 ± 563.98 a |

| 11 | Dimethyl sulfide | 32.25 ± 6.42 a | 1.95 ± 0.01 b |

| 15 | TMA | 6835.34 ± 192.34 a | 1155.23 ± 294.80 b |

| 17 | Propanal | 20,433.20 ± 2682.42 | 18,367.55 ± 2413.40 |

| 21 | 2-Methyl propanal | 29.41 ± 2.27 b | 35.29 ± 0.83 a |

| 72 | 3-Pentanone | 33.47 ± 4.05 b | 83.86 ± 6.21 a |

| 109 | 1-Propanol | 424.23 ± 41.09 a | 314.49 ± 31.62 b |

| 117 | S-Methyl thioacetate | 0.65 ± 0.13 | 0.61 ± 0.08 |

| 122 | 2,3-Pentanedione | 5437.58 ± 75.25 | 5622.35 ± 581.15 |

| 217 | Cyclohexanone | 2.87 ± 0.26 a | 1.61 ± 0.05 b |

| 238 | trans -3-Hexen-1-ol | 11.55 ± 1.57 a | 7.90 ± 0.42 b |

| 243 | cis-3-Hexen-1-ol | 13.49 ± 0.21 | 14.04 ± 1.51 |

| 248 | 2-Nonanone | 28.84 ± 6.97 a | 2.32 ± 0.27 b |

| 267 | 1-Heptanol | 78.29 ± 14.90 a | 22.52 ± 2.58 b |

| 277 | trans, trans-2,4-Heptadienal | 2873.71 ± 975.98 | 2284.54 ± 11.92 |

| 300 | 2,6,10,14-Tetramethylpentadecane | 92,840.44 ± 2619.88 a | 2206.21 ± 613.18 b |

| Pairwise Comparison | Aroma ΔRS | Flavor ΔRS |

|---|---|---|

| SO—CO | 42 * | 42 * |

| SO—TA | 23 * | 25 * |

| SO—TB | 15 | 13 |

| CO—TA | 19 | 17 |

| CO—TB | 27 * | 29 * |

| TA—TB | 8 | 12 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Mori, Y.; Hatanaka, A.; Fukusaki, E. Exploration of Key Flavor Compounds in Five Grilled Salmonid Species by Integrating Volatile Profiling and Sensory Evaluation. Metabolites 2026, 16, 30. https://doi.org/10.3390/metabo16010030

Mori Y, Hatanaka A, Fukusaki E. Exploration of Key Flavor Compounds in Five Grilled Salmonid Species by Integrating Volatile Profiling and Sensory Evaluation. Metabolites. 2026; 16(1):30. https://doi.org/10.3390/metabo16010030

Chicago/Turabian StyleMori, Yuka, Akimasa Hatanaka, and Eiichiro Fukusaki. 2026. "Exploration of Key Flavor Compounds in Five Grilled Salmonid Species by Integrating Volatile Profiling and Sensory Evaluation" Metabolites 16, no. 1: 30. https://doi.org/10.3390/metabo16010030

APA StyleMori, Y., Hatanaka, A., & Fukusaki, E. (2026). Exploration of Key Flavor Compounds in Five Grilled Salmonid Species by Integrating Volatile Profiling and Sensory Evaluation. Metabolites, 16(1), 30. https://doi.org/10.3390/metabo16010030