Rutin Maintains the Thermogenic Phenotype of Beige Adipocytes and Concomitantly Suppresses Mitophagy Against Obesity in HFD Mice

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Experimental Design and Animal Grouping

2.2.1. HFD Obesity Model

2.2.2. Cold Exposure and Withdrawal Protocol

2.2.3. Sample Collection and Biochemical Analysis

2.3. Cell Culture and Treatment

2.4. IPGTT

2.5. H&E and IHC Staining

2.6. Western Blot Analysis

2.7. qPCR

| Target Gene | Forward Primer (5′-3′) | Reverse Primer (5′-3′) |

|---|---|---|

| PINK1 | GAGGAGAAGCAGGCGGAAGG | TGCCAGCATCGAGTGTCCAG |

| Parkin | TTGACACGAGTGGACCTGAGC | ACCTCTGGCTGCTTCTGAATCC |

| β-actin | GTGCTATGTTCTAGACTTCG | ATGCCACAGGATTCCATACC |

2.8. Oil Red O Staining

2.9. Immunofluorescence

2.10. Mito-Tracker Red Staining

2.11. ATP Detection

2.12. ROS

2.13. JC-1

2.14. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Rutin Inhibited the Beige-to-White Transition and Preserved the Phenotype of Beige Adipocytes Following CL Withdrawal

3.2. Rutin Alleviated Mitochondrial Dysfunction in Beige Adipocytes Following CL Withdrawal

3.3. Rutin Suppressed Mitochondrial Autophagy in Beige Adipocytes After CL Withdrawal

3.4. The Changes in LC3B/p62 Protein Expression of Beige Adipocytes After Rutin Treatments Were Consistent with Autophagy Activity

3.5. Rutin Continuously Improved Metabolic Indicators in HFD-Induced Obese Mice After Withdrawal of Cold Stimulation

3.6. Rutin Preserved the Thermogenic Characteristics of Beige Adipocytes in the iWAT Following Withdrawal of Cold Stimulation

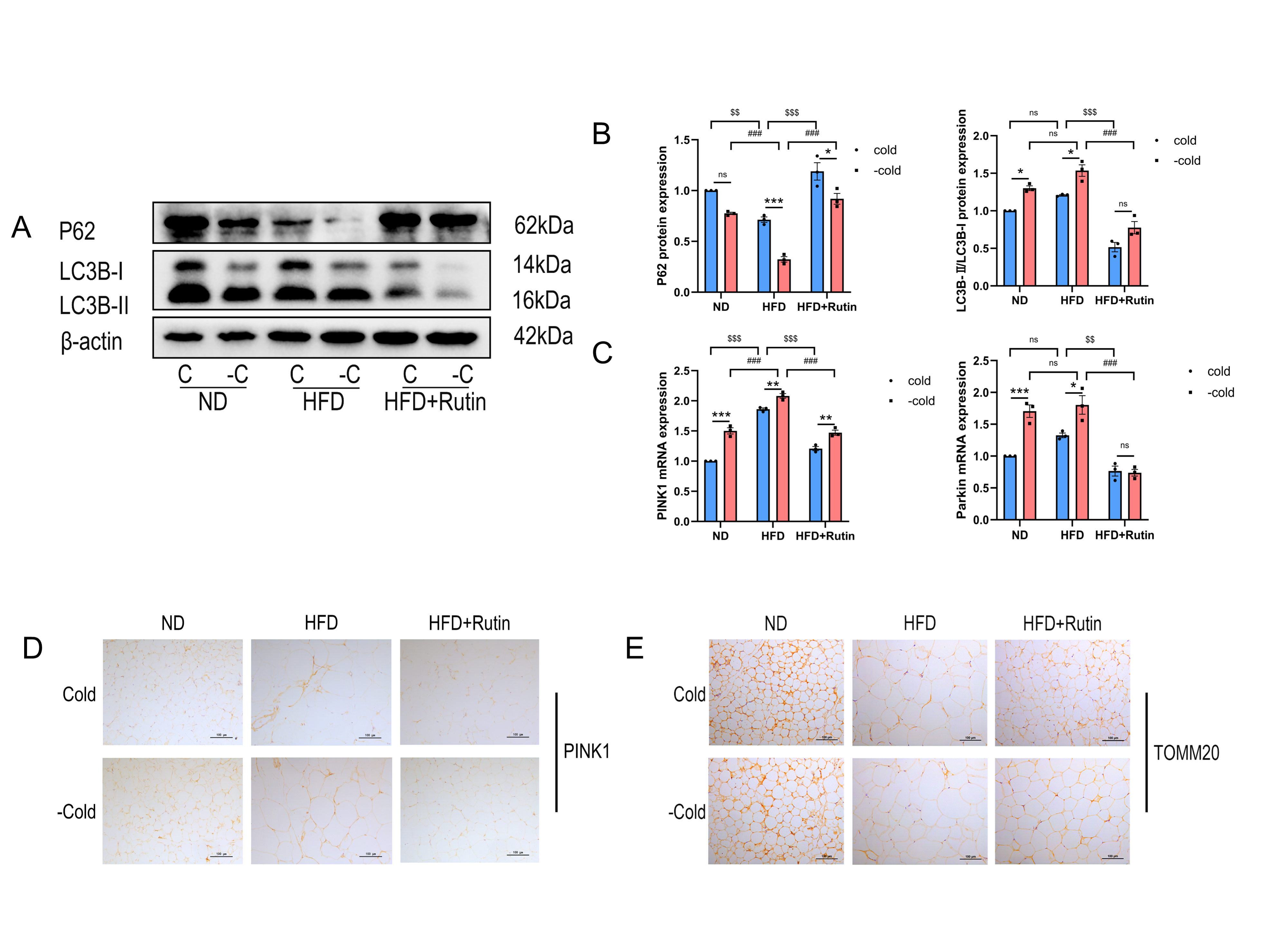

3.7. Rutin Suppressed Mitochondrial Autophagy Following Cold Withdrawal and Increased Mitochondrial Numbers in iWAT

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| WAT | White adipocyte tissue |

| BAT | Brown adipocyte tissue |

| eWAT | Epididymal white adipose tissue |

| iWAT | Inguinal white adipose tissue |

| UCP1 | Uncoupling protein-1 |

| PGC-1α | Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ coactivator 1alpha |

| PRDM16 | PR domain-containing 16 |

| LC3 | Microtubule-associated protein light chain 3 |

| LC3B-II | Microtubule-associated proteins 1A/1B light chain 3B-II |

| P62 | Sequestosome 1 |

| TOMM20 | Translocase of outer mitochondrial membrane 20 |

| RT-qPCR | Quantitative real-time PCR |

| ROS | Reactive oxygen species |

| ATP | Adenosine triphosphate |

| MMP | Mitochondrial membrane potential |

| JC-1 | Mitochondrial membrane potential assay kit with JC-1 |

| M | Minimum essential medium, MEM |

| H&E | Hematoxylin and eosin |

| HFD | High-fat diet |

References

- Ahmed, B.; Sultana, R.; Greene, M.W. Adipose Tissue and Insulin Resistance in Obese. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2021, 137, 111315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, P.; Levy, J.D.; Zhang, Y.; Frontini, A.; Kolodin, D.P.; Svensson, K.J.; Lo, J.C.; Zeng, X.; Ye, L.; Khandekar, M.J.; et al. Ablation of Prdm16 and Beige Adipose Causes Metabolic Dysfunction and a Subcutaneous to Visceral Fat Switch. Cell 2014, 156, 304–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowell, B.B.; Spiegelman, B.M. Towards a Molecular Understanding of Adaptive Thermogenesis. Nature 2000, 404, 652–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marcelin, G.; Silveira, A.L.M.; Martins, L.B.; Ferreira, A.V.; Clément, K. Deciphering the Cellular Interplays Underlying Obesity-Induced Adipose Tissue Fibrosis. J. Clin. Investig. 2019, 129, 4032–4040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, K.Y.; Luong, Q.; Sharma, R.; Dreyfuss, J.M.; Ussar, S.; Kahn, C.R. Developmental and Functional Heterogeneity of White Adipocytes within a Single Fat Depot. EMBO J. 2019, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harms, M.; Seale, P. Brown and Beige Fat: Development, Function and Therapeutic Potential. Nat. Med. 2013, 19, 1252–1263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zoico, E.; Rubele, S.; De Caro, A.; Nori, N.; Mazzali, G.; Fantin, F.; Rossi, A.; Zamboni, M. Brown and Beige Adipose Tissue and Aging. Front. Endocrinol. 2019, 10, 368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shapira, S.N.; Seale, P. Transcriptional Control of Brown and Beige Fat Development and Function. Obesity 2019, 27, 13–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keipert, S.; Jastroch, M. Brite/Beige Fat and Ucp1—Is It Thermogenesis? Biochim. Biophys. Acta (BBA) Bioenerg. 2014, 1837, 1075–1082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cannon, B.; Nedergaard, J. Brown Adipose Tissue: Function and Physiological Significance. Physiol. Rev. 2004, 84, 277–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, Y.; Wang, Y.; Li, X.; Qin, H.; Yan, S.; Rao, C.; Fan, D.; Liu, D.; Deng, F.; Miao, Y.; et al. Prmt4 Facilitates White Adipose Tissue Browning and Thermogenesis by Methylating Pparγ. Diabetes 2023, 72, 1095–1111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotzbeck, P.; Giordano, A.; Mondini, E.; Murano, I.; Severi, I.; Venema, W.; Cecchini, M.P.; Kershaw, E.E.; Barbatelli, G.; Haemmerle, G.; et al. Brown Adipose Tissue Whitening Leads to Brown Adipocyte Death and Adipose Tissue Inflammation. J. Lipid Res. 2018, 59, 784–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, R.; Park, J.; Qian, Y.; Shi, Z.; Hu, R.; Yuan, Y.; Xiong, S.; Wang, Z.; Yan, G.; Ong, S.-G.; et al. Genetically Prolonged Beige Fat in Male Mice Confers Long-Lasting Metabolic Health. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 2731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Das, S.; Mukhuty, A.; Mullen, G.P.; Rudolph, M.C. Adipocyte Mitochondria: Deciphering Energetic Functions across Fat Depots in Obesity and Type 2 Diabetes. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 6681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.; Chen, J.; Hu, M.; Zheng, W.; Song, Z.; Qin, H. Sesamol Promotes Browning of White Adipocytes to Ameliorate Obesity by Inducing Mitochondrial Biogenesis and Inhibition Mitophagy Via β3-Ar/Pka Signaling Pathway. Food Nutr. Res. 2021, 65, 10-29219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, X. Maintaining Mitochondria in Beige Adipose Tissue. Adipocyte 2019, 8, 77–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, X.; Altshuler-Keylin, S.; Wang, Q.; Chen, Y.; Sponton, C.H.; Ikeda, K.; Maretich, P.; Yoneshiro, T.; Kajimura, S. Mitophagy Controls Beige Adipocyte Maintenance through a Parkin-Dependent and Ucp1-Independent Mechanism. Sci. Signal. 2018, 11, eaap8526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazarou, M.; Sliter, D.A.; Kane, L.A.; Sarraf, S.A.; Wang, C.; Burman, J.L.; Sideris, D.P.; Fogel, A.I.; Youle, R.J. The Ubiquitin Kinase Pink1 Recruits Autophagy Receptors to Induce Mitophagy. Nature 2015, 524, 309–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heo, J.-M.; Ordureau, A.; Paulo, J.A.; Rinehart, J.; Harper, J.W. The Pink1-Parkin Mitochondrial Ubiquitylation Pathway Drives a Program of Optn/Ndp52 Recruitment and Tbk1 Activation to Promote Mitophagy. Mol. Cell 2015, 60, 7–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarraf, S.A.; Raman, M.; Guarani-Pereira, V.; Sowa, M.E.; Huttlin, E.L.; Gygi, S.P.; Harper, J.W. Landscape of the Parkin-Dependent Ubiquitylome in Response to Mitochondrial Depolarization. Nature 2013, 496, 372–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirkin, V.; Lamark, T.; Sou, Y.-S.; Bjørkøy, G.; Nunn, J.L.; Bruun, J.-A.; Shvets, E.; McEwan, D.G.; Clausen, T.H.; Wild, P.; et al. A Role for Nbr1 in Autophagosomal Degradation of Ubiquitinated Substrates. Mol. Cell 2009, 33, 505–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z.; Yang, T.; Zeng, M.; Wang, Z.; Chen, Q.; Chen, J.; Christian, M.; He, Z. Miquelianin in Folium Nelumbinis Extract Promotes White-to-Beige Fat Conversion Via Blocking Ampk/Drp1/Mitophagy and Modulating Gut Microbiota in Hfd-Fed Mice. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2023, 181, 114089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, S.; Li, Y.; Teng, W.; Du, M.; Li, Y.; Sun, B. Liensinine Inhibits Beige Adipocytes Recovering to White Adipocytes through Blocking Mitophagy Flux in Vitro and in Vivo. Nutrients 2019, 11, 1640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Altshuler-Keylin, S.; Shinoda, K.; Hasegawa, Y.; Ikeda, K.; Hong, H.; Kang, Q.; Yang, Y.; Perera, R.M.; Debnath, J.; Kajimura, S. Beige Adipocyte Maintenance Is Regulated by Autophagy-Induced Mitochondrial Clearance. Cell Metab. 2016, 24, 402–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.-H.; Petkova, A.P.; Mottillo, E.P.; Granneman, J.G. In Vivo Identification of Bipotential Adipocyte Progenitors Recruited by β3-Adrenoceptor Activation and High-Fat Feeding. Cell Metab. 2012, 15, 480–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delgado-Anglés, A.; Blasco-Roset, A.; Godoy-Nieto, F.J.; Cairó, M.; Villarroya, F.; Giralt, M.; Villarroya, J. Parkin Depletion Prevents the Age-Related Alterations in the Fgf21 System and the Decline in White Adipose Tissue Thermogenic Function in Mice. J. Physiol. Biochem. 2024, 80, 41–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iqbal, A.; Kamran, S.H.; Siddique, F.; Ishtiaq, S.; Hameed, M.; Manzoor, M. Modulatory Effects of Rutin and Vitamin a on Hyperglycemia Induced Glycation, Oxidative Stress and Inflammation in High-Fat-Fructose Diet Animal Model. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0303060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, C.-L.; Wu, C.-H.; Huang, S.-L.; Yen, G.-C. Phenolic Compounds Rutin and O-Coumaric Acid Ameliorate Obesity Induced by High-Fat Diet in Rats. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2009, 57, 425–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, B.; Hao, J.; Xu, H.; Liu, L.; Wang, W.; Chen, S.; Wu, H. Rutin Promotes White Adipose Tissue “Browning” and Brown Adipose Tissue Activation Partially through the Calmodulin-Dependent Protein Kinase Kinase β/Amp-Activated Protein Kinase Pathway. Endocr. J. 2022, 69, 385–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Ping, X.; Zhang, Y.; Li, G.; Zhang, T.; Chen, G.; Ma, X.; Wang, D.; Xu, L. Comparative Transcriptome Profiling of Cold Exposure and β3-Ar Agonist Cl316,243-Induced Browning of White Fat. Front. Physiol. 2021, 12, 667698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kajimura, S.; Spiegelman, B.M.; Seale, P. Brown and Beige Fat: Physiological Roles Beyond Heat Generation. Cell Metab. 2015, 22, 546–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ikeda, K.; Kang, Q.; Yoneshiro, T.; Camporez, J.P.; Maki, H.; Homma, M.; Shinoda, K.; Chen, Y.; Lu, X.; Maretich, P.; et al. Ucp1-Independent Signaling Involving Serca2b-Mediated Calcium Cycling Regulates Beige Fat Thermogenesis and Systemic Glucose Homeostasis. Nat. Med. 2017, 23, 1454–1465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taylor, D.; Gottlieb, R.A. P Parkin-Mediated Mitophagy Is Downregulated in Browning of White Adipose Tissue. Obesity 2017, 25, 704–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Li, J.; Li, K.; Li, S.; Cui, J.; Zhou, S.; Wu, H. Rutin Maintains the Thermogenic Phenotype of Beige Adipocytes and Concomitantly Suppresses Mitophagy Against Obesity in HFD Mice. Metabolites 2026, 16, 12. https://doi.org/10.3390/metabo16010012

Li J, Li K, Li S, Cui J, Zhou S, Wu H. Rutin Maintains the Thermogenic Phenotype of Beige Adipocytes and Concomitantly Suppresses Mitophagy Against Obesity in HFD Mice. Metabolites. 2026; 16(1):12. https://doi.org/10.3390/metabo16010012

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Jianmei, Kexin Li, Shengnan Li, Jingxun Cui, Shuangying Zhou, and Huiwen Wu. 2026. "Rutin Maintains the Thermogenic Phenotype of Beige Adipocytes and Concomitantly Suppresses Mitophagy Against Obesity in HFD Mice" Metabolites 16, no. 1: 12. https://doi.org/10.3390/metabo16010012

APA StyleLi, J., Li, K., Li, S., Cui, J., Zhou, S., & Wu, H. (2026). Rutin Maintains the Thermogenic Phenotype of Beige Adipocytes and Concomitantly Suppresses Mitophagy Against Obesity in HFD Mice. Metabolites, 16(1), 12. https://doi.org/10.3390/metabo16010012