The Role of Mitochondrial Dynamics in Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Steatotic Liver Disease and the Regulatory Mechanisms of Exercise Intervention: A Systematic Review of Preclinical Studies

Abstract

1. Introduction

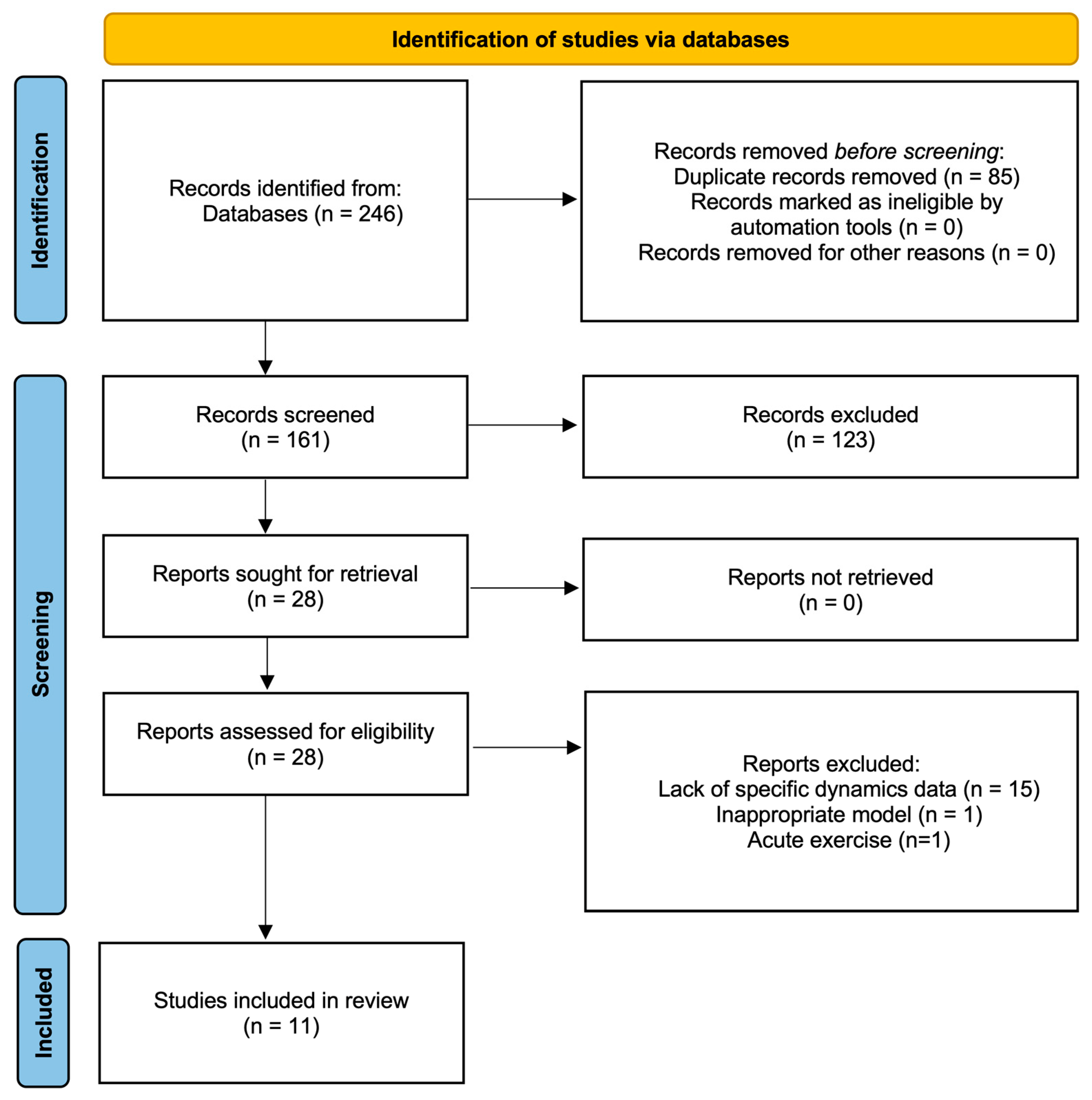

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Search Strategy

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

2.3. Study Selection and Data Extraction

2.4. Quality Assessment

2.5. Data Analysis

3. Result

3.1. Identified Records

3.2. Methodological Quality Assessment

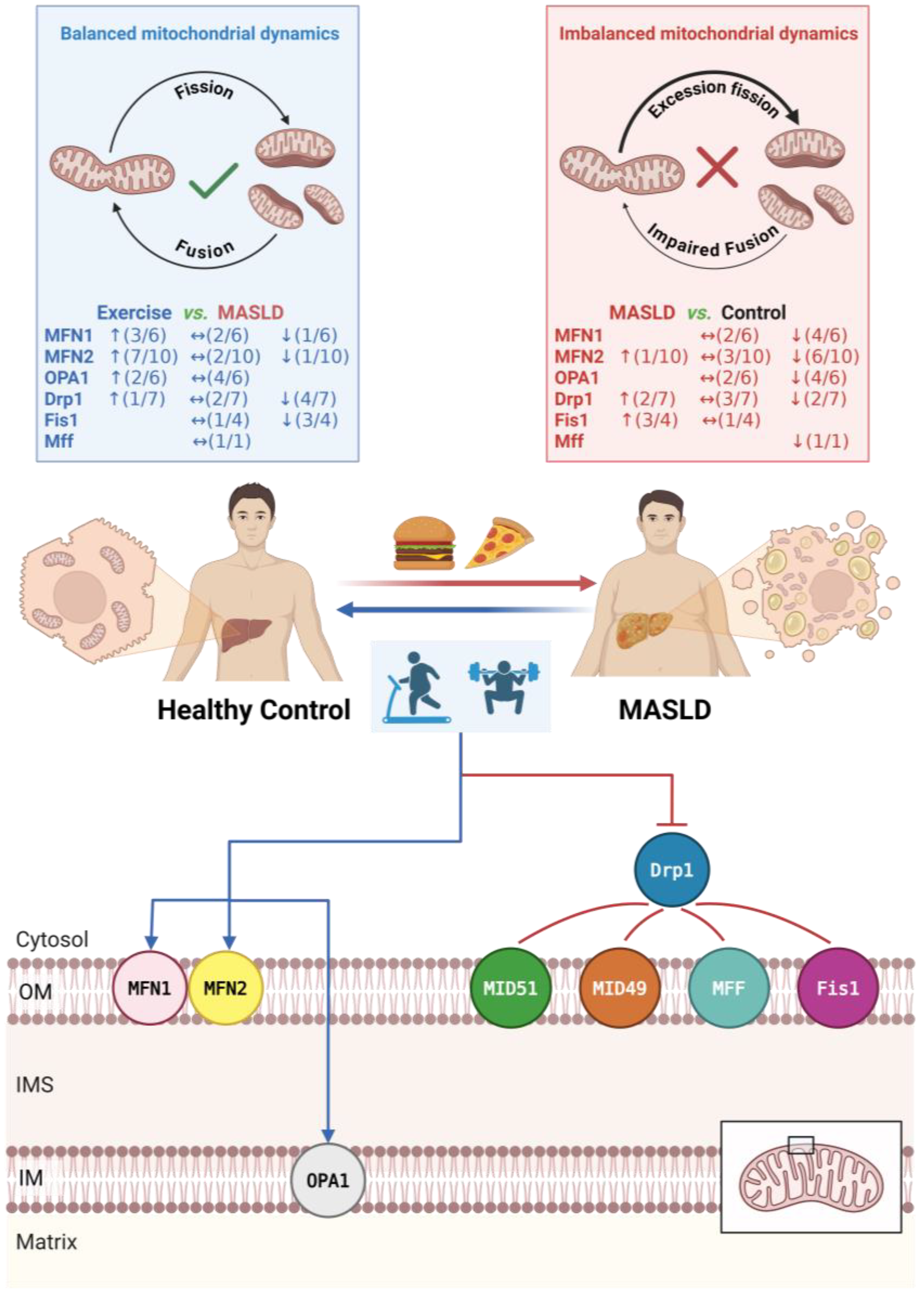

3.3. Regulatory Effects of Exercise Intervention on Mitochondrial Dynamics

3.3.1. Effects of Exercise on Mitochondrial Fusion Proteins

| Reference | Study Model | Study Protocol | Key Results ↓ Down Significantly, ↑ Up Significantly, ↔ No Significant | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Specie Sex | Age | Disease Stage | Modeling Protocol | Exercise Classification | Exercise Protocol Details | MASLD/MASH vs. Control | Exercise vs. MASLD/MASH | |

| Zou et al. (2023) [23] | Zebrafish AB strain | 6 months | MASLD | 12 weeks HFD (24% energy from fat) Exercise concurrent with HFD | Aerobic Exercise MICT | Mode: Swimming Intensity: Month 1: 6 × BL/s (~40% Ucrit) for 4 h Months 2–3: 8 × BL/s (~55% Ucrit) for 4 h Freq: 5 d/w Duration: 12 weeks | MASLD: ↓ MFN2 protein ↓ OPA1 protein ↓ Drp1 protein | MICT: ↑ MFN2 protein ↔ OPA1 protein ↑ Drp1 protein |

| Hu et al. (2023) [22] | Rats Sprague-Dawley Male | 4–5 weeks | MASLD | 11 weeks HFD (60% energy from fat) Exercise started at week 6 of HFD | Combined Exercise RE + MICT | Mode: Treadmill Intensity: Resistance: 10–25° incline, 20–25 cm/s (2 min)/rest (1 min) × 8 cycles Aerobic: Continuous running 30 min Freq: 5 d/w Duration: 5 weeks | MASLD: ↓ MFN2 protein ↓ OPA1 protein ↑ Drp1 protein | RE + MICT: ↑ MFN2 protein ↑ OPA1 protein ↓ Drp1 protein |

| Deng et al. (2025) [17] | Rats Sprague-Dawley Male | 300 g | MASLD | 16 weeks HFD (60% energy from fat) Exercise started at week 8 of HFD | Aerobic Exercise HIIT or MICT | Mode: Treadmill Intensity: HIIT: 85–90% Smax (4 min)/50–60% Smax (2 min) × 10 cycles MICT: 70% Smax for 60 min Freq: 7 d/w Duration: 8 weeks Volume-matched HIIT and MICT | MASLD: ↓ MFN1 protein ↓ MFN2 protein ↑ Fis1 protein | HIIT: ↑ MFN1 protein ↑ MFN2 protein ↓ Fis1 protein MICT: ↑ MFN1 protein ↑ MFN2 protein ↓ Fis1 protein |

| Gonçalves et al. (2016) [18] | Rats Sprague-Dawley Male | 6–7 weeks | MASH | 17 weeks liquid HFD (71% energy from fat) VWR concurrent with HFD, MICT started at week 9 of HFD | Aerobic Exercise MICT or VWR | Mode: Treadmill (MICT) or Voluntary wheel (VWR) MICT: Intensity: 15–25 m/min for 60 min Freq: 5 d/w Duration: 8 weeks VWR: Voluntary wheel running with ad libitum Duration: 17 weeks | MASH: ↓ MFN1 protein ↔ MFN2 protein ↔ OPA1 protein ↔ Drp1 protein | MICT: ↑ MFN1 protein ↑ MFN2 protein ↔ OPA1 protein ↔ Drp1 protein VWR: ↔ MFN1 protein ↔ MFN2 protein ↔ OPA1 protein ↔ Drp1 protein |

| Andani et al. (2024) [25] | Rats Wistar Male | 230 ± 10 g | MASH | DEX injected at week 8 (2.5 → 10 mg/kg) Exercise performed prior/during | Aerobic Exercise HIIT or MICT | Mode: Treadmill Intensity: HIIT: 5% incline, 85% VO2peak (40 m/min, 3 min)/20 m/min (3 min) × 6 cycles MICT: 0 incline, 20 m/min Freq: 3 d/w Duration: 8 weeks Volume-matched HIIT and MICT | MASH: ↔ MFN2 mRNA | HIIT: ↔ MFN2 mRNA MICT: ↔ MFN2 mRNA |

| Stevanović-Silva et al. (2023) [20] | Rats Sprague-Dawley Female | 7 weeks | GDM MASLD | 18 weeks HFHS (42% energy from fat containing high cholesterol and 31% energy from carbohydrates mainly as sucrose) Exercise during pregnancy | Aerobic Exercise MICT + VWR | Mode: Treadmill + Voluntary Wheel MICT: Intensity: Week1: 18 m/min for 20–60 min, Weeks 2–3: 21 m/min for 60 min Freq: 6 d/w Duration: 3 weeks VWR: Voluntary wheel running ad libitum | GDM MASLD: ↔ MFN1 protein ↓ MFN2 protein ↓ OPA1 protein ↔ Drp1 protein (trend up) ↔ MFN1 mRNA ↔ MFN2 mRNA (trend down) ↔ Drp1 mRNA (trend down) | MICT + VWR: ↑ MFN1 protein ↑ MFN2 protein ↔ OPA1 protein ↓ Drp1 protein ↔ MFN1 mRNA ↔ MFN2 mRNA (trend up) ↔ Drp1 mRNA (trend up) |

| Li et al. (2024) [26] | Mice C57BL/6J Male | 12 weeks | MASLD | 8 weeks HFD (45% energy from fat) Exercise concurrent with HFD | Aerobic Exercise HIIT or MICT | Mode: Treadmill Intensity: HIIT: 85% Smax (2 min)/40% HIS (2 min) × 12 cycles MICT: 45–50% Smax for 60 min Freq: 5 d/w Duration: 8 weeks HIS every week increase 1 m/min, Volume-matched HIIT and MICT | MASLD: ↔ OPA1 protein ↑ Fis1 protein | HIIT: ↑ OPA1 protein ↓ Fis1 protein MICT: ↔ OPA1 protein ↓ Fis1 protein |

| Rosa-Caldwell et al. (2017) [21] | Mice C57BL/6J Male | 8 weeks | MASLD | 8 weeks WD (42% energy from fat containing 1.5 g/kg cholesterol) Exercise started at week 4 of WD | Aerobic Exercise VWR | Voluntary wheel running ad libitum Duration: 4 weeks | MASLD: ↔ MFN1 mRNA ↔ MFN2 mRNA ↓ OPA1 mRNA ↓ MFN2 protein ↓ Mff mRNA ↓ Drp1 mRNA ↔ Fis1 mRNA ↓ Drp1 protein | VWR: ↔ MFN1 mRNA ↔ OPA1 mRNA ↑ MFN2 mRNA ↔ MFN2 protein ↔ Mff mRNA ↔ Drp1 mRNA ↔ Fis1 mRNA ↔ Drp1 protein |

| da Costa Fernandes et al. (2025) [16] | Mice Swiss Male | 8 weeks | MASLD | 14 weeks HFD (60% energy from fat) Exercise after model establishment | Resistance Exercise | Mode: Ladder Climbing Intensity: 70% MVCC/rest (60–90 s) × 20 climbs Freq: 7 d/w Duration: 8 weeks | MASLD: ↓ MFN1 mRNA ↑ MFN2 mRNA ↑ Fis1 mRNA ↑ Drp1 mRNA | RE: ↓ MFN1 mRNA ↓ MFN2 mRNA ↓ Fis1 mRNA ↓ Drp1 mRNA |

| Bórquez et al. (2024) [24] | Mice C57BL/6J Male | 4 weeks | MASLD | 12 weeks HFD (60% energy from fat) Exercise started at week 8 of HFD | Aerobic Exercise MICT | Mode: Treadmill Intensity: 60–65% Smax for 60 min Freq: 5 d/w Duration:4 weeks | MASLD: ↔ MFN2 protein | MICT: ↑ MFN2 protein |

| Bórquez et al. (2024) [24] | Mice C57BL/6J Male | 8 weeks | MASH | 4 weeks MCD (methionine choline-deficient diet combined 45% HFD) Exercise concurrent with MCD | Aerobic Exercise MICT | Mode: Treadmill Intensity: 60–65% Smax for 60 min Freq: 5 d/w Duration:4 weeks | MASH: ↔ MFN2 protein | MICT: ↑ MFN2 protein |

| Wang et al. (2023) [19] | Mice C57BL/6J Male | 6 weeks | T2DM MASH | 20 weeks HFD (60% energy from fat) STZ injected at week 12 of HFD Exercise started at week 12 of HFD | Aerobic Exercise HIIT | Mode: Treadmill Intensity: 15° incline, 16 m/min (4 min)/rest (2 min) × 12 cycles Freq: 5 d/w Duration: 8 weeks Weeks 1–4 speed increased by 2 m/min every week Weeks 5–8 speed increased by 1 m/min every week | T2DM MASH: ↓ MFN1 mRNA ↓ MFN2 mRNA ↔ Drp1 mRNA | HIIT: ↔ MFN1 mRNA ↑ MFN2 mRNA ↓ Drp1 mRNA |

3.3.2. Effects of Exercise on Mitochondrial Fission Proteins

3.4. Regulatory Effects of Exercise on Mitochondrial Quality Control

3.4.1. Effects of Exercise on Mitochondrial Biogenesis

3.4.2. Effects of Exercise on Mitophagy and Autophagic Flux

4. Discussion

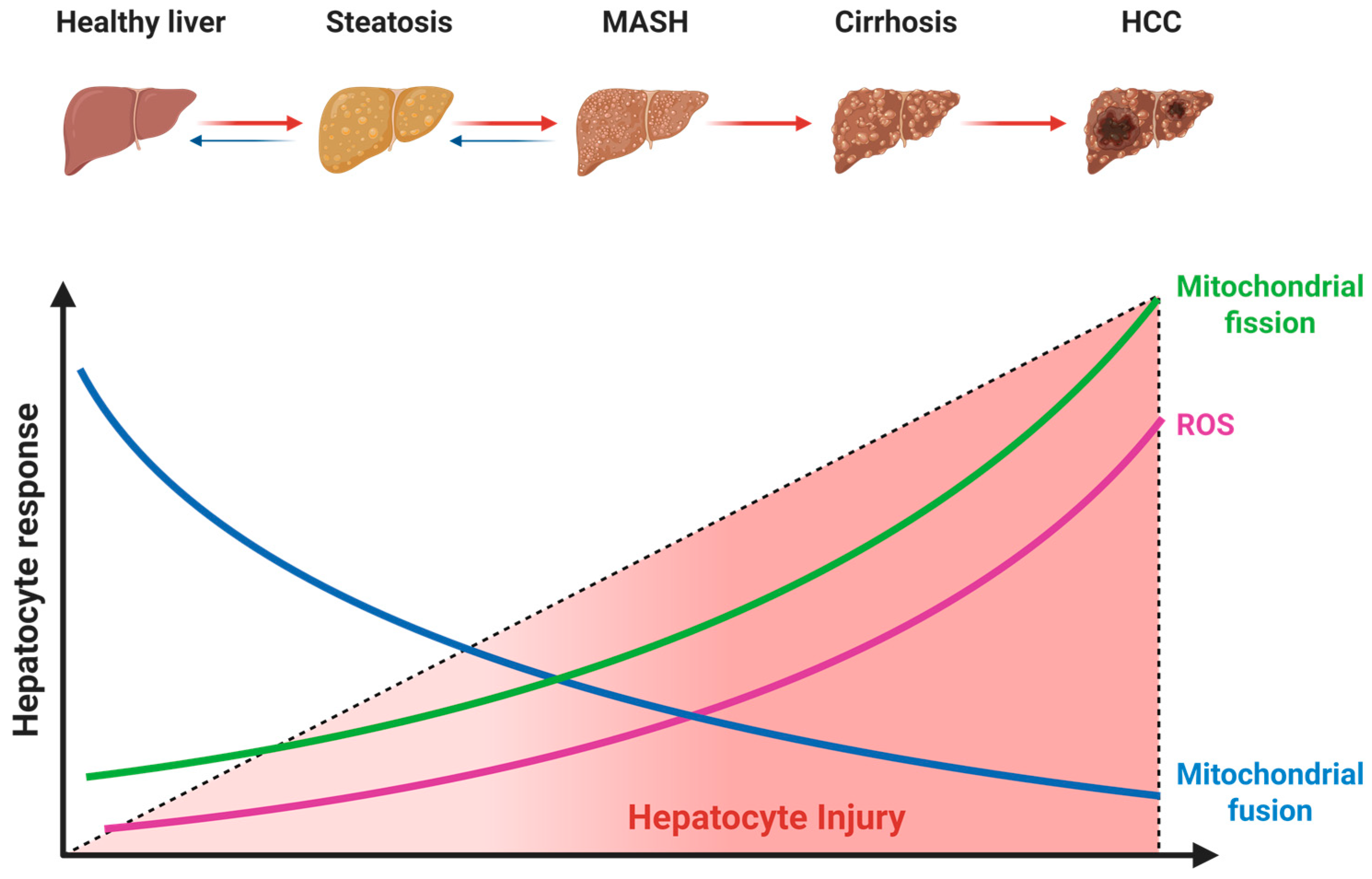

4.1. Dysregulated Mitochondrial Dynamics in MASLD Pathogenesis

4.1.1. Suppression of Mitochondrial Fusion

4.1.2. Aberrant Activation of Mitochondrial Fission

4.2. Effects of Exercise on Mitochondrial Dynamics

4.2.1. Effects on Fusion Proteins

4.2.2. Effects on Fission Proteins

4.3. Effects of Exercise on Mitochondrial Quality Control Indicators

4.3.1. Effects on Mitochondrial Biogenesis

4.3.2. Effects on Mitophagy

4.4. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| NAFLD | Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease |

| MAFLD | Metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease |

| MASLD | Metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease |

| MASH | Metabolic dysfunction-associated steatohepatitis |

| OPA1 | Optic atrophy 1 |

| mtDNA | Mitochondrial DNA |

| MFN1 | Mitofusin 1 |

| MFN2 | Mitofusin 2 |

| ER | Endoplasmic reticulum |

| Drp1 | Dynamin-related protein 1 |

| MiD49 | Mitochondrial dynamics proteins of 49 kDa |

| MiD51 | Mitochondrial dynamics proteins of 51 kDa |

| Fis1 | Fission protein 1 |

| MFF | Mitochondrial fission factor |

| ROS | Reactive oxygen species |

| HIIT | High intensity interval training |

| MICT | Moderate intensity continuous training |

| VWR | Voluntary wheel running |

| DEX | Dexamethasone |

| T2DM | Type 2 diabetes mellitus |

| GDM | Gestational diabetes mellitus |

| HFD | High-fat diet |

| HFHS | High-fat high-sucrose diet |

| HIS | High-intensity speed |

| MCD | Methionine-choline deficient diet |

| MVCC | Maximal voluntary carrying capacity |

| RE | Resistance exercise |

| STZ | Streptozotocin |

| VO2peak | Peak oxygen uptake |

| OMA1 | Mitochondrial inner membrane zinc-dependent metalloprotease |

| YME1L | Yeast mitochondrial escape 1-like ATPase |

| WD | Western diet |

| TFAM | Mitochondrial transcription factor A |

| PGC-1α | Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma coactivator 1-alpha |

| NRF1 | Nuclear respiratory factor 1 |

| NRF2 | Nuclear respiratory factor 2 |

| P62 | Sequestosome 1 |

| BNIP3 | BCL2/adenovirus E1B 19 kDa protein-interacting protein 3 |

| DRAM | Damage-regulated autophagy modulator |

| PINK1 | PTEN-induced putative kinase 1 |

| LC3 | Microtubule-associated protein 1 light chain 3 |

| Parkin | E3 ubiquitin-protein ligase Parkin |

References

- Guo, Z.; Wu, D.; Mao, R.; Yao, Z.; Wu, Q.; Lv, W. Global Burden of MAFLD, MAFLD Related Cirrhosis and MASH Related Liver Cancer from 1990 to 2021. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 7083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lou, T.-W.; Yang, R.-X.; Fan, J.-G. The Global Burden of Fatty Liver Disease: The Major Impact of China. Hepatobiliary Surg. Nutr. 2024, 13, 119–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rinella, M.E.; Neuschwander-Tetri, B.A.; Siddiqui, M.S.; Abdelmalek, M.F.; Caldwell, S.; Barb, D.; Kleiner, D.E.; Loomba, R. AASLD Practice Guidance on the Clinical Assessment and Management of Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. Hepatology 2023, 77, 1797–1835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Imai, J.; Takashimizu, S.; Suzuki, N.; Ohshinden, K.; Sawamoto, K.; Mishima, Y.; Tsuruya, K.; Arase, Y.; Yamano, M.; Kishimoto, N.; et al. Comparative Study of MAFLD as a Predictor of Metabolic Disease Treatment for NAFLD. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 13411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eslam, M.; Sanyal, A.J.; George, J.; International Consensus Panel. MAFLD: A Consensus-Driven Proposed Nomenclature for Metabolic Associated Fatty Liver Disease. Gastroenterology 2020, 158, 1999–2014.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Younossi, Z.M.; Rinella, M.E.; Sanyal, A.J.; Harrison, S.A.; Brunt, E.M.; Goodman, Z.; Cohen, D.E.; Loomba, R. From NAFLD to MAFLD: Implications of a Premature Change in Terminology. Hepatology 2021, 73, 1194–1198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rinella, M.E.; Lazarus, J.V.; Ratziu, V.; Francque, S.M.; Sanyal, A.J.; Kanwal, F.; Romero, D.; Abdelmalek, M.F.; Anstee, Q.M.; Arab, J.P.; et al. A Multisociety Delphi Consensus Statement on New Fatty Liver Disease Nomenclature. J. Hepatol. 2023, 79, 1542–1556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Longo, M.; Meroni, M.; Paolini, E.; Macchi, C.; Dongiovanni, P. Mitochondrial Dynamics and Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease (NAFLD): New Perspectives for a Fairy-Tale Ending? Metabolism 2021, 117, 154708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, B.; Wu, T.; Nasb, M.; Li, Z.; Chen, N. Regular Exercise Alleviates Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Steatohepatitis through Rescuing Mitochondrial Oxidative Stress and Dysfunction in Liver. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2025, 230, 163–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, S.; Tang, D.; Feng, J. Mitochondrial Targeted Therapies in MAFLD. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2025, 753, 151498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 Statement: An Updated Guideline for Reporting Systematic Reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liberati, A.; Altman, D.G.; Tetzlaff, J.; Mulrow, C.; Gøtzsche, P.C.; Ioannidis, J.P.A.; Clarke, M.; Devereaux, P.J.; Kleijnen, J.; Moher, D. The PRISMA Statement for Reporting Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses of Studies That Evaluate Health Care Interventions: Explanation and Elaboration. PLoS Med. 2009, 6, e1000100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hooijmans, C.R.; Rovers, M.M.; de Vries, R.B.; Leenaars, M.; Ritskes-Hoitinga, M.; Langendam, M.W. SYRCLE’s Risk of Bias Tool for Animal Studies. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2014, 14, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Long, Y.-F.; Chow, S.K.-H.; Cui, C.; Wong, R.M.Y.; Zhang, N.; Qin, L.; Law, S.-W.; Cheung, W.-H. Does Exercise Influence Skeletal Muscle by Modulating Mitochondrial Functions via Regulating MicroRNAs? A Systematic Review. Ageing Res. Rev. 2023, 91, 102048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, Y.-F.; Chow, S.K.-H.; Cui, C.; Wong, R.M.Y.; Qin, L.; Law, S.-W.; Cheung, W.-H. Regulation of Mitochondrial Dynamic Equilibrium by Physical Exercise in Sarcopenia: A Systematic Review. J. Orthop. Transl. 2022, 35, 37–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Costa Fernandes, C.J.; da Cruz Rodrigues, V.C.; de Sá Pereira, G.J.; de Melo, D.G.; de Campos, T.D.P.; Dos Santos Canciglieri, R.; da Silva, R.A.F.; da Silva, A.S.R.; Pauli, J.R.; Gross, A.; et al. Epigenetically Modulated MTCH2 and Regulated ATP5 in the Liver of Obese Mice Subjected to Strength Training. Life Sci. 2025, 384, 124105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, D.; Xu, L.; Liu, Y.; Li, C.; Jiang, Q.; Shi, J.; Feng, S.; Lin, Y. HIIT versus MICT in MASLD: Mechanisms Mediated by Gut-Liver Axis Crosstalk, Mitochondrial Dynamics Remodeling, and Adipokine Signaling Attenuation. Lipids Health Dis. 2025, 24, 144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonçalves, I.; Passos, E.; Diogo, C.; Rocha-Rodrigues, S.; Santos-Alves, E.; Oliveira, P.; Ascensao, A.; Magalhaes, J. Exercise Mitigates Mitochondrial Permeability Transition Pore and Quality Control Mechanisms Alterations in Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis. Appl. Physiol. Nutr. Metab. 2016, 41, 298–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Guo, Y.; Xu, Y.; Wang, W.; Zhuang, S.; Wang, R.; Xiao, W. HIIT Ameliorates Inflammation and Lipid Metabolism by Regulating Macrophage Polarization and Mitochondrial Dynamics in the Liver of Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus Mice. Metabolites 2023, 13, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevanovic-Silva, J.; Beleza, J.; Coxito, P.; Oliveira, P.; Ascensao, A.; Magalhaes, J. Gestational Exercise Antagonises the Impact of Maternal High-Fat High-Sucrose Diet on Liver Mitochondrial Alterations and Quality Control Signalling in Male Offspring. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 1388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosa-Caldwell, M.; Lee, D.; Brown, J.; Brown, L.; Perry, R.; Greene, E.; Chaigneau, F.; Washington, T.; Greene, N. Moderate Physical Activity Promotes Basal Hepatic Autophagy in Diet-Induced Obese Mice. Appl. Physiol. Nutr. Metab. 2017, 42, 148–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Z.; Zhang, H.; Wang, Y.; Li, B.; Liu, K.; Ran, J.; Li, L. Exercise Activates Sirt1-Mediated Drp1 Acetylation and Inhibits Hepatocyte Apoptosis to Improve Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. Lipids Health Dis. 2023, 22, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zou, Y.; Tang, X.; Chen, Z.; Liu, B.; Zheng, L.; Song, M.; Xiao, Q.; Zhou, Z.; Peng, X.; Tang, C. Exercise Intervention Improves Mitochondrial Quality in Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease Zebrafish. Front. Endocrinol. 2023, 14, 1162485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bórquez, J.; Díaz-Castro, F.; Pino-de La Fuente, F.; Espinoza, K.; Figueroa, A.; Martínez-Ruíz, I.; Hernández, V.; López-Soldado, I.; Ventura, R.; Domingo, J.; et al. Mitofusin-2 Induced by Exercise Modifies Lipid Droplet-Mitochondria Communication, Promoting Fatty Acid Oxidation in Male Mice with NAFLD. Metab.-Clin. Exp. 2024, 152, 155765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andani, F.; Talebi-Garakani, E.; Ashabi, G.; Ganbarirad, M.; Hashemnia, M.; Sharifi, M.; Ghasemi, M. Exercise-Activated Hepatic Autophagy Combined with Silymarin Is Associated with Suppression of Apoptosis in Rats Subjected to Dexamethasone Induced- Fatty Liver Damage. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2024, 51, 928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Yang, J.; Hu, W.; Ruan, Y.; Chen, H.; Zhang, Q.; Zhang, Z.; Ding, Z. Mitochondria-Associated Membranes Contribution to Exercise-Mediated Alleviation of Hepatic Insulin Resistance: Contrasting High-Intensity Interval Training with Moderate-Intensity Continuous Training in a High-Fat Diet Mouse Model. J. Diabetes 2024, 16, e13540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Zhao, H.; Li, Y. Mitochondrial Dynamics in Health and Disease: Mechanisms and Potential Targets. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2023, 8, 333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, P.; Chan, D.C. Metabolic Regulation of Mitochondrial Dynamics. J. Cell Biol. 2016, 212, 379–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevanović, J.; Beleza, J.; Coxito, P.; Ascensão, A.; Magalhães, J. Physical Exercise and Liver “Fitness”: Role of Mitochondrial Function and Epigenetics-Related Mechanisms in Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. Mol. Metab. 2020, 32, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tábara, L.-C.; Segawa, M.; Prudent, J. Molecular Mechanisms of Mitochondrial Dynamics. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2025, 26, 123–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Alvarez, M.I.; Zorzano, A. Mitochondrial Dynamics and Liver Cancer. Cancers 2021, 13, 2571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hernández-Alvarez, M.I.; Sebastián, D.; Vives, S.; Ivanova, S.; Bartoccioni, P.; Kakimoto, P.; Plana, N.; Veiga, S.R.; Hernández, V.; Vasconcelos, N.; et al. Deficient Endoplasmic Reticulum-Mitochondrial Phosphatidylserine Transfer Causes Liver Disease. Cell 2019, 177, 881–895.e17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hou, J.; Zhang, J.; Cui, P.; Zhou, Y.; Liu, C.; Wu, X.; Ji, Y.; Wang, S.; Cheng, B.; Ye, H.; et al. TREM2 Sustains Macrophage-Hepatocyte Metabolic Coordination in Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease and Sepsis. J. Clin. Investig. 2021, 131, e135197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, X.; Liao, Y.; Lin, Z.; Luo, H.; Wei, G.; Huang, N.; Li, Y.; Chen, J.; Su, Z.; Yu, X.; et al. Patchouli Alcohol Alleviates Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Steatohepatitis via Inhibiting Mitochondria-Associated Endoplasmic Reticulum Membrane Disruption-Induced Hepatic Steatosis and Inflammation in Rats. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2024, 138, 112634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, J.; Zhang, X.; Han, J.; Man, K.; Zhang, Y.; Chu, E.S.; Nan, Y.; Yu, J. Pro-Inflammatory CXCR3 Impairs Mitochondrial Function in Experimental Non-Alcoholic Steatohepatitis. Theranostics 2017, 7, 4192–4203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanfardino, P.; Amati, A.; Perrone, M.; Petruzzella, V. The Balance of MFN2 and OPA1 in Mitochondrial Dynamics, Cellular Homeostasis, and Disease. Biomolecules 2025, 15, 433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.; Yoon, Y. Mitochondrial Membrane Dynamics-Functional Positioning of OPA1. Antioxidants 2018, 7, 186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, Y.; Shi, X.; Boopathy, S.; McDonald, J.; Smith, A.W.; Chao, L.H. Two Forms of Opa1 Cooperate to Complete Fusion of the Mitochondrial Inner-Membrane. eLife 2020, 9, e50973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Martin-Levilain, J.; Jiménez-Sánchez, C.; Karaca, M.; Foti, M.; Martinou, J.-C.; Maechler, P. In Vivo Stabilization of OPA1 in Hepatocytes Potentiates Mitochondrial Respiration and Gluconeogenesis in a Prohibitin-Dependent Way. J. Biol. Chem. 2019, 294, 12581–12598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, F.; Fang, M.; Zhang, H.; Song, Q.; Li, S.; Li, Y.; Jiang, S.; Yang, L. Drp1: Focus on Diseases Triggered by the Mitochondrial Pathway. Cell Biochem. Biophys. 2024, 82, 435–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, W.; Wang, L.; Wang, C.; Xiong, X.; Huang, Q.; Chen, S.; Liu, C.; Liu, W.; Wang, Y.; Huang, Q. SENP1 Prevents High Fat Diet-Induced Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Diseases by Regulating Mitochondrial Dynamics. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Basis Dis. 2025, 1871, 167527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Liu, W.; Zhang, J.; Sun, C. The Role of Mitochondrial Quality Control in Liver Diseases: Dawn of a Therapeutic Era. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 2025, 21, 1767–1783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, D.; Yang, Y.; Hou, Y.; Zhao, Z.; Liang, N.; Yuan, P.; Yang, T.; Xing, J.; Li, J. Increased Mitochondrial Fission Drives the Reprogramming of Fatty Acid Metabolism in Hepatocellular Carcinoma Cells through Suppression of Sirtuin 1. Cancer Commun. Lond. Engl. 2022, 42, 37–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elbadawy, M.; Tanabe, K.; Yamamoto, H.; Ishihara, Y.; Mochizuki, M.; Abugomaa, A.; Yamawaki, H.; Kaneda, M.; Usui, T.; Sasaki, K. Evaluation of the Efficacy of Mitochondrial Fission Inhibitor (Mdivi-1) Using Non-Alcoholic Steatohepatitis (NASH) Liver Organoids. Front. Pharmacol. 2023, 14, 1243258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.; Ma, A.; Moore, T.M.; Wolf, D.M.; Yang, N.; Tran, P.; Segawa, M.; Strumwasser, A.R.; Ren, W.; Fu, K.; et al. Drp1 Controls Complex II Assembly and Skeletal Muscle Metabolism by Sdhaf2 Action on Mitochondria. Sci. Adv. 2024, 10, eadl0389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Xie, X.; Tao, J.; Wang, S.; Hu, M.; Wang, X.; Yu, Z.; Xu, L.; Lin, Y.; Wu, W.; et al. Mystery of Bisphenol F-Induced Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease-like Changes: Roles of Drp1-Mediated Abnormal Mitochondrial Fission in Lipid Droplet Deposition. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 904, 166831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Liu, Z.; Huang, X.; Heng, X.; Wu, J.; Chen, Z.; Guo, X.; Fan, J.; Huang, Q. Mdivi-1 Alleviates Sepsis-Induced Liver Injury by Inhibiting Sting Signaling Activation. Shock 2024, 62, 95–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steffen, J.; Ngo, J.; Wang, S.-P.; Williams, K.; Kramer, H.F.; Ho, G.; Rodriguez, C.; Yekkala, K.; Amuzie, C.; Bialecki, R.; et al. The Mitochondrial Fission Protein Drp1 in Liver Is Required to Mitigate NASH and Prevents the Activation of the Mitochondrial ISR. Mol. Metab. 2022, 64, 101566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Price, S.; Wiecha, S.; Cieśliński, I.; Śliż, D.; Kasiak, P.S.; Lach, J.; Gruba, G.; Kowalski, T.; Mamcarz, A. Differences between Treadmill and Cycle Ergometer Cardiopulmonary Exercise Testing Results in Triathletes and Their Association with Body Composition and Body Mass Index. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 3557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toyama, E.Q.; Herzig, S.; Courchet, J.; Lewis, T.L.; Losón, O.C.; Hellberg, K.; Young, N.P.; Chen, H.; Polleux, F.; Chan, D.C.; et al. AMP-Activated Protein Kinase Mediates Mitochondrial Fission in Response to Energy Stress. Science 2016, 351, 275–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunningham, J.T.; Rodgers, J.T.; Arlow, D.H.; Vazquez, F.; Mootha, V.K.; Puigserver, P. mTOR Controls Mitochondrial Oxidative Function through a YY1–PGC-1α Transcriptional Complex. Nature 2007, 450, 736–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narendra, D.P.; Jin, S.M.; Tanaka, A.; Suen, D.-F.; Gautier, C.A.; Shen, J.; Cookson, M.R.; Youle, R.J. PINK1 Is Selectively Stabilized on Impaired Mitochondria to Activate Parkin. PLoS Biol. 2010, 8, e1000298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wan, S. Mitochondrial MFN2 Integrates the Function of Multiple Organelles to Regulate Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Steatotic Liver Disease: Mechanisms and Therapeutic Insights. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2025, 242, 117423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Hu, Y.; Zou, F.; Ding, L.; Jiang, M. Unlocking the Benefits of Aerobic Exercise for MAFLD: A Comprehensive Mechanistic Analysis. J. Transl. Med. 2025; online ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; He, J.; Bao, L.; Shi, X.; Wang, J.; Li, Q. Harnessing Exercise to Combat Chronic Diseases: The Role of Drp1-Mediated Mitochondrial Fission. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2025, 13, 1481756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Reference | Study Model | Exercise Protocol | Key Results ↓ Down Significantly, ↑ Up Significantly, ↔ No Significant | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Specie Sex | Age | Disease Stage | Exercise Classification | MASLD/MASH vs. Control | Exercise vs. MASLD/MASH | |

| Zou et al.(2023) [23] | Zebrafish AB strain | 6 months | MASLD | Aerobic Exercise MICT | MASLD: ↓ PGC1α protein ↓ TFAM protein ↓ NRF1 protein ↓ NRF2 protein ↓ PINK1 protein ↓ Parkin protein ↑ P62 protein | MICT: ↑ PGC1α protein ↑ TFAM protein ↑ NRF1 protein ↑ NRF2 protein ↔ PINK1 protein ↑ Parkin protein ↓ P62 protein |

| Deng et al. (2025) [17] | Rats Sprague-Dawley Male | 300 g | MASLD | Aerobic Exercise HIIT or MICT | MASLD: ↓ PGC1α protein ↓ PINK1 protein ↓ Parkin protein | HIIT: ↑ PGC1α protein ↑ PINK1 protein ↑ Parkin protein MICT: ↑ PGC1α protein ↑ PINK1 protein ↑ Parkin protein |

| Gonçalves et al. (2016) [18] | Rats Sprague-Dawley Male | 6–7 weeks | MASH | Aerobic Exercise MICT or VWR | MASH: ↔ PGC1α protein ↓ TFAM protein ↓ PINK1 protein ↓ Parkin protein ↔ LC3-II protein ↔ P62 protein | MICT: ↑ PGC1α protein ↑ TFAM protein ↑ PINK1 protein ↑ Parkin protein ↔ LC3-II protein ↔ P62 protein VWR: ↑ PGC1α protein ↔ TFAM protein ↔ PINK1 protein ↔ Parkin protein ↔ LC3-II protein ↔ P62 protein |

| Andani et al.(2024) [25] | Rats Wistar Male | 230 ± 10 g | MASH | Aerobic Exercise HIIT or MICT | MASH: ↔ DRAM mRNA | HIIT: ↔ DRAM mRNA MICT: ↑ DRAM mRNA |

| Stevanović-Silva et al. (2023) [20] | Rats Sprague-Dawley Female | 7 weeks | GDM MASLD | Aerobic Exercise MICT + VWR | GDM MASLD: ↔ PGC1α protein ↔ TFAM protein ↔ PINK1 protein ↓ Parkin protein ↔ LC3-II/LC3-I protein | MICT + VWR: ↔ PGC1α protein ↑ TFAM protein ↔ PINK1 protein ↔ Parkin protein ↔ LC3-II/LC3-I protein |

| Li et al. (2024) [26] | Mice C57BL/6J Male | 12 weeks | MASLD | Aerobic Exercise HIIT or MICT | MASLD: ↓ PINK1 protein ↓ Parkin protein ↑ LC3-II/LC3-I protein ↑ BNIP3 protein | HIIT: ↔ PINK1 protein ↑ Parkin protein ↔ LC3-II/LC3-I ↓ BNIP3 protein MICT: ↑ PINK1 protein ↑ Parkin protein ↓ LC3-II/LC3-I protein ↓ BNIP3 protein |

| Rosa-Caldwell et al. (2017) [21] | Mice C57BL/6J Male | 8 weeks | MASLD | Aerobic Exercise VWR | MASLD: ↓ PGC1α mRNA ↔ LC3-II/LC3-I protein ↔ P62 protein ↓ BNIP3 protein ↔ BNIP3 mRNA | VWR: ↔ PGC1α mRNA ↑ LC3-II/LC3-I protein ↓ P62 protein ↔ BNIP3 protein ↔ BNIP3 mRNA |

| da Costa Fernandes et al. (2025) [16] | Mice Swiss Male | 8 weeks | MASLD | Resistance Exercise | MASLD: ↔ PGC1α mRNA ↔ TFAM mRNA ↔ NRF1 mRNA ↑ NRF2 mRNA ↑ PGC1α protein ↑ NRF2 protein | RE: ↓ PGC1α mRNA ↓ TFAM mRNA ↓ NRF1 mRNA ↓ NRF2 mRNA ↓ PGC1α protein ↓ NRF2 protein |

| Wang et al. (2023) [19] | Mice C57BL/6J Male | 6 weeks | T2DM MASH | Aerobic Exercise HIIT | T2DM MASH: ↓ PGC1α mRNA ↓ TFAM mRNA ↓ NRF1 mRNA | HIIT: ↑ PGC1α mRNA ↑ TFAM mRNA ↔ NRF1 mRNA |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Tian, H.; Wang, A.; Wu, H.; Yan, L.; Wang, J. The Role of Mitochondrial Dynamics in Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Steatotic Liver Disease and the Regulatory Mechanisms of Exercise Intervention: A Systematic Review of Preclinical Studies. Metabolites 2026, 16, 11. https://doi.org/10.3390/metabo16010011

Tian H, Wang A, Wu H, Yan L, Wang J. The Role of Mitochondrial Dynamics in Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Steatotic Liver Disease and the Regulatory Mechanisms of Exercise Intervention: A Systematic Review of Preclinical Studies. Metabolites. 2026; 16(1):11. https://doi.org/10.3390/metabo16010011

Chicago/Turabian StyleTian, Haonan, Aozhe Wang, Haoran Wu, Lin Yan, and Jun Wang. 2026. "The Role of Mitochondrial Dynamics in Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Steatotic Liver Disease and the Regulatory Mechanisms of Exercise Intervention: A Systematic Review of Preclinical Studies" Metabolites 16, no. 1: 11. https://doi.org/10.3390/metabo16010011

APA StyleTian, H., Wang, A., Wu, H., Yan, L., & Wang, J. (2026). The Role of Mitochondrial Dynamics in Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Steatotic Liver Disease and the Regulatory Mechanisms of Exercise Intervention: A Systematic Review of Preclinical Studies. Metabolites, 16(1), 11. https://doi.org/10.3390/metabo16010011