Assessing the Feasibility of In Vitro Assays in Combination with Biological Matrices to Screen for Endogenous CYP450 Phenotype Biomarkers Using an Untargeted Metabolomics Approach—A Proof of Concept Study

Abstract

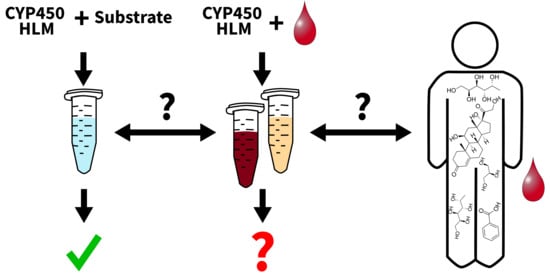

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Blood and Plasma Samples

2.3. In Vitro Assays

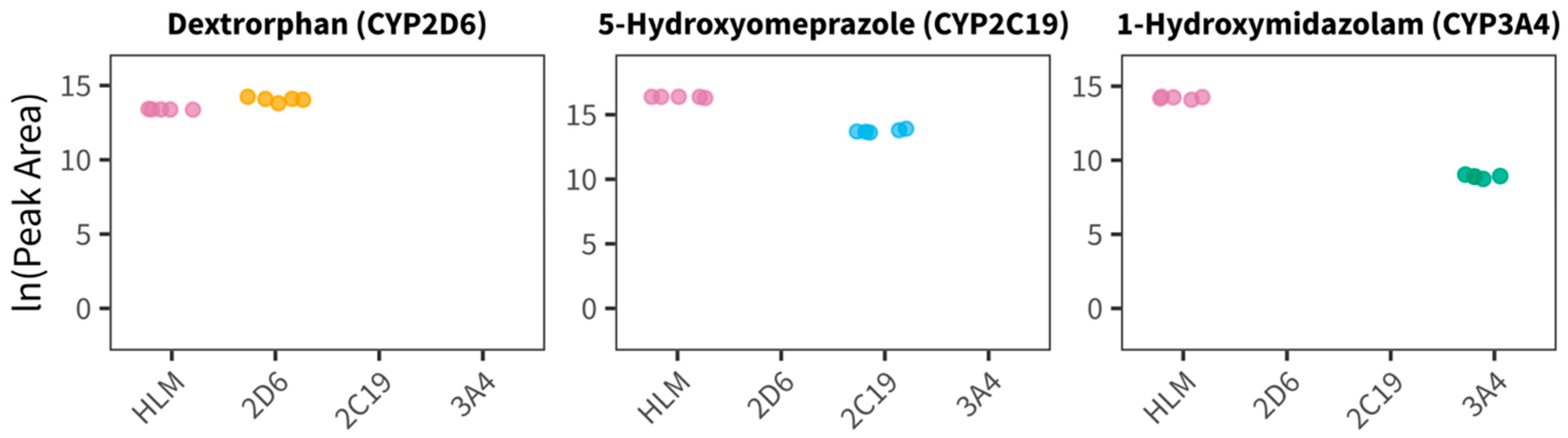

2.4. Targeted LC-MS/MS Data Acquisition

2.5. Untargeted LC-qTOF-MS Data Acquisition

2.6. Evaluation of Assay Performance in the Presence of Blood or Plasma (Experiment 1)

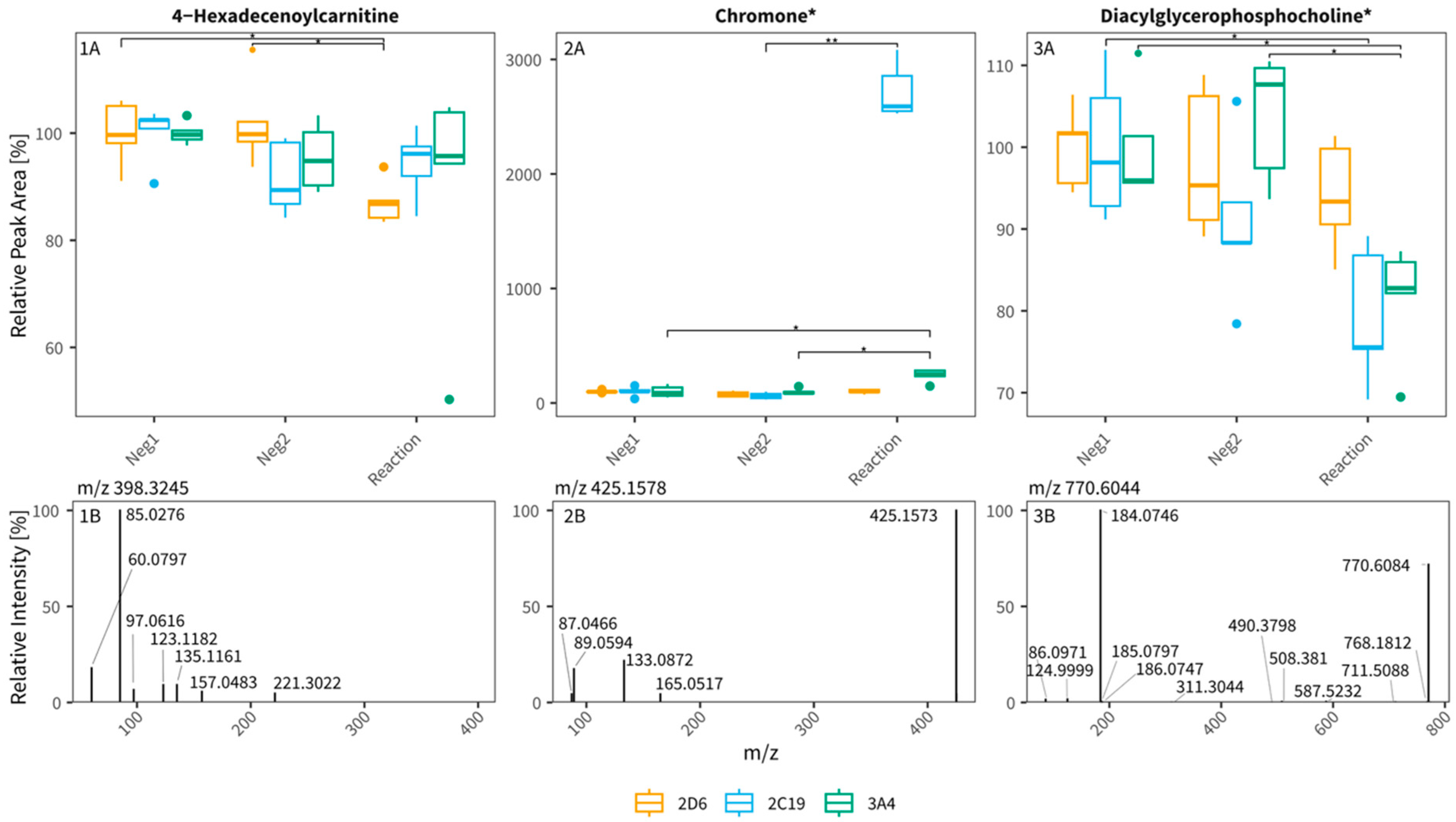

2.7. Untargeted Analysis for Initial CYP Biomarker Search (Experiment 2)

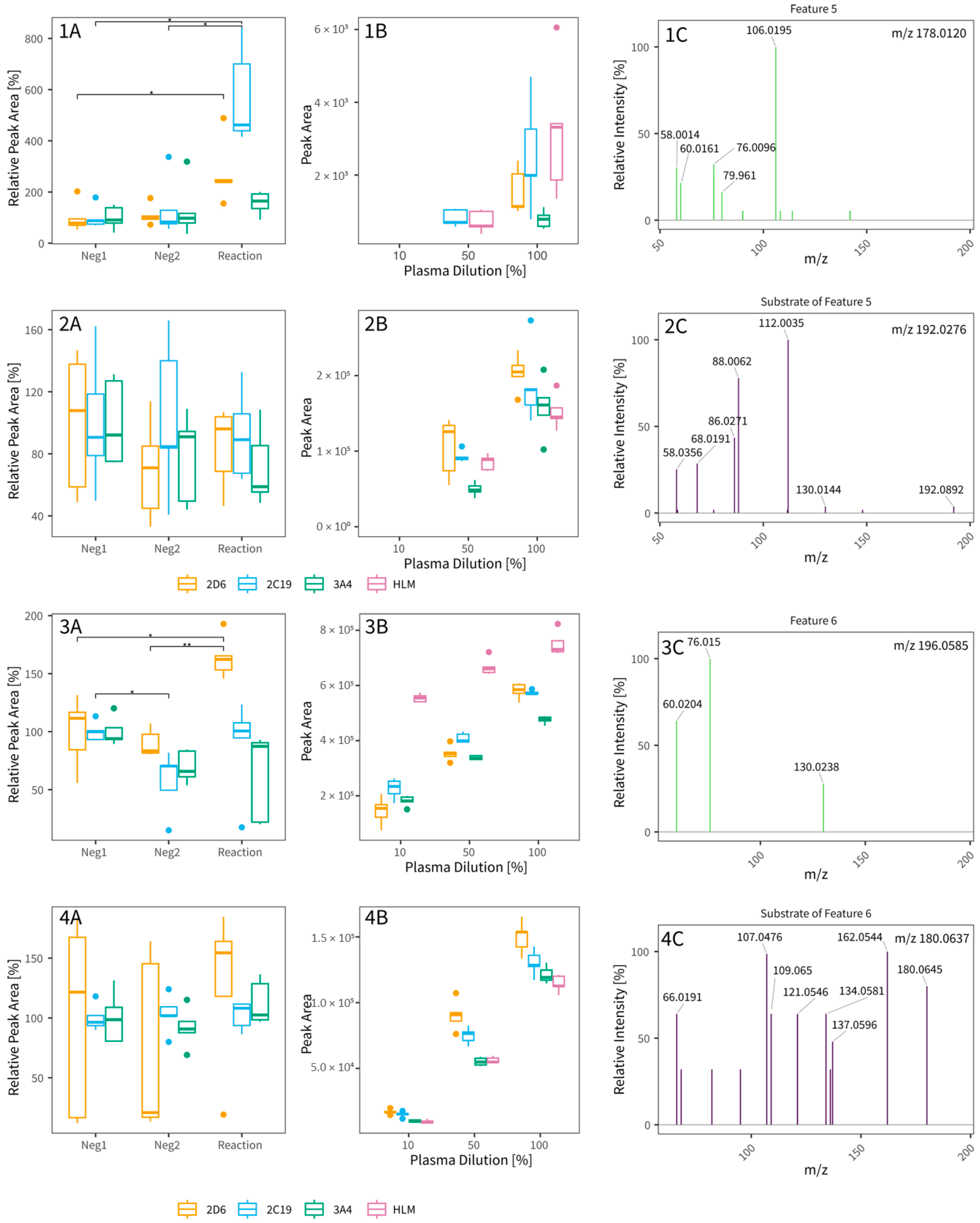

2.8. Further Evaluation of the Potential CYP Biomarker (Experiment 3)

3. Results

3.1. Evaluation of the General CYP Assay Performance in the Presence of Blood or Plasma (Experiment 1)

3.2. Untargeted Metabolomics Workflow for Tentative CYP Biomarker Search in In Vitro Assays (Experiments 2 and 3)

4. Discussion

4.1. General CYP Assay Performance in the Presence of Blood or Plasma

4.2. Untargeted Metabolomics Workflow for Tentative CYP Biomarker Search in In Vitro Assays

5. Conclusions and Outlook

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ingelman-Sundberg, M. Human drug metabolising cytochrome P450 enzymes: Properties and polymorphisms. Naunyn-Schmiedeberg’s Arch. Pharmacol. 2004, 369, 89–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertz, R.J.; Granneman, G.R. Use of in vitro and in vivo data to estimate the likelihood of metabolic pharmacokinetic interactions. Clin. Pharmacokinet. 1997, 32, 210–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magliocco, G.; Thomas, A.; Desmeules, J.; Daali, Y. Phenotyping of Human CYP450 Enzymes by Endobiotics: Current Knowledge and Methodological Approaches. Clin. Pharmacokinet. 2019, 58, 1373–1391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanger, U.M.; Schwab, M. Cytochrome P450 enzymes in drug metabolism: Regulation of gene expression, enzyme activities, and impact of genetic variation. Pharmacol. Ther. 2013, 138, 103–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Fernando, A.; Adrián, L. Simultaneous Determination of Cytochrome P450 Oxidation Capacity in Humans: A Review on the Phenotyping Cocktail Approach. Curr. Pharm. Biotechnol. 2016, 17, 1159–1180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rollason, V.; Mouterde, M.; Daali, Y.; Čížková, M.; Priehodová, E.; Kulichová, I.; Posová, H.; Petanová, J.; Mulugeta, A.; Makonnen, E.; et al. Safety of the Geneva Cocktail, a Cytochrome P450 and P-Glycoprotein Phenotyping Cocktail, in Healthy Volunteers from Three Different Geographic Origins. Drug Saf. 2020, 43, 1181–1189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Donzelli, M.; Derungs, A.; Serratore, M.G.; Noppen, C.; Nezic, L.; Krahenbuhl, S.; Haschke, M. The basel cocktail for simultaneous phenotyping of human cytochrome P450 isoforms in plasma, saliva and dried blood spots. Clin. Pharmacokinet. 2014, 53, 271–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magliocco, G.; Desmeules, J.; Bosilkovska, M.; Thomas, A.; Daali, Y. The 1beta-Hydroxy-Deoxycholic Acid to Deoxycholic Acid Urinary Metabolic Ratio: Toward a Phenotyping of CYP3A Using an Endogenous Marker? J. Pers. Med. 2021, 11, 150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Magliocco, G.; Desmeules, J.; Matthey, A.; Quiros-Guerrero, L.M.; Bararpour, N.; Joye, T.; Marcourt, L.; Queiroz, E.F.; Wolfender, J.L.; Gloor, Y.; et al. Metabolomics Reveals Biomarkers in Human Urine and Plasma to Predict Cyp2d6 Activity. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2021, 178, 4708–4725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aderemi, A.V.; Ayeleso, A.O.; Oyedapo, O.O.; Mukwevho, E. Metabolomics: A Scoping Review of Its Role as a Tool for Disease Biomarker Discovery in Selected Non-Communicable Diseases. Metabolites 2021, 11, 418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steuer, A.E.; Brockbals, L.; Kraemer, T. Metabolomic Strategies in Biomarker Research-New Approach for Indirect Identification of Drug Consumption and Sample Manipulation in Clinical and Forensic Toxicology? Front. Chem. 2019, 7, 319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, J.; Zhen, Y.; Miksys, S.; Beyoglu, D.; Krausz, K.W.; Tyndale, R.F.; Yu, A.; Idle, J.R.; Gonzalez, F.J. Potential role of CYP2D6 in the central nervous system. Xenobiotica 2013, 43, 973–984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, B.; Lee, J.; Shin, K.H.; Lee, S.; Yu, K.S.; Jang, I.J.; Cho, J.Y. Identification of omega- or (omega-1)-Hydroxylated Medium-Chain Acylcarnitines as Novel Urinary Biomarkers for CYP3A Activity. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 2018, 103, 879–887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, J.; Qian, X.; Zhou, Y.; Xiong, S.; Ji, S.; Wang, Y.; Zhao, P. Human liver microsomes study on the inhibitory effect of plantainoside D on the activity of cytochrome P450 activity. BMC Complement. Med. Ther. 2022, 22, 197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luffer-Atlas, D.; Atrakchi, A. A decade of drug metabolite safety testing: Industry and regulatory shared learning. Expert. Opin. Drug Metab. Toxicol. 2017, 13, 897–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diao, X.; Huestis, M. Approaches, Challenges, and Advances in Metabolism of New Synthetic Cannabinoids and Identification of Optimal Urinary Marker Metabolites. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 2017, 101, 239–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, Z.; Martin, M.V.; Guengerich, F.P. Elucidation of functions of human cytochrome P450 enzymes: Identification of endogenous substrates in tissue extracts using metabolomic and isotopic labeling approaches. Anal. Chem. 2009, 81, 3071–3078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staeheli, S.N.; Veloso, V.P.; Bovens, M.; Bissig, C.; Kraemer, T.; Poetzsch, M. Liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry screening method using information-dependent acquisition of enhanced product ion mass spectra for synthetic cannabinoids including metabolites in urine. Drug Test. Anal. 2019, 11, 1369–1376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boxler, M.I.; Schneider, T.D.; Kraemer, T.; Steuer, A.E. Analytical considerations for (un)-targeted metabolomic studies with special focus on forensic applications. Drug Test. Anal. 2019, 11, 678–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steuer, A.E.; Wartmann, Y.; Schellenberg, R.; Mantinieks, D.; Glowacki, L.L.; Gerostamoulos, D.; Kraemer, T.; Brockbals, L. Postmortem metabolomics: Influence of time since death on the level of endogenous compounds in human femoral blood. Necessary to be considered in metabolome study planning? Metabolomics 2024, 20, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsugawa, H.; Cajka, T.; Kind, T.; Ma, Y.; Higgins, B.; Ikeda, K.; Kanazawa, M.; VanderGheynst, J.; Fiehn, O.; Arita, M. MS-DIAL: Data-independent MS/MS deconvolution for comprehensive metabolome analysis. Nat. Methods 2015, 12, 523–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dührkop, K.; Fleischauer, M.; Ludwig, M.; Aksenov, A.A.; Melnik, A.V.; Meusel, M.; Dorrestein, P.C.; Rousu, J.; Böcker, S. SIRIUS 4: A rapid tool for turning tandem mass spectra into metabolite structure information. Nat. Methods 2019, 16, 299–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing, Version 4.4.3; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2021.

- Wartmann, Y.; Boxler, M.I.; Kraemer, T.; Steuer, A.E. Impact of three different peak picking software tools on the quality of untargeted metabolomics data. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2024, 248, 116302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sumner, L.W.; Amberg, A.; Barrett, D.; Beale, M.H.; Beger, R.; Daykin, C.A.; Fan, T.W.; Fiehn, O.; Goodacre, R.; Griffin, J.L.; et al. Proposed minimum reporting standards for chemical analysis Chemical Analysis Working Group (CAWG) Metabolomics Standards Initiative (MSI). Metabolomics 2007, 3, 211–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buters, J.T.; Shou, M.; Hardwick, J.P.; Korzekwa, K.R.; Gonzalez, F.J. cDNA-directed expression of human cytochrome P450 CYP1A1 using baculovirus. Purification, dependency on NADPH-P450 oxidoreductase, and reconstitution of catalytic properties without purification. Drug Metab. Dispos. 1995, 23, 696–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallifax, D.; Foster, J.A.; Houston, J.B. Prediction of human metabolic clearance from in vitro systems: Retrospective analysis and prospective view. Pharm. Res. 2010, 27, 2150–2161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ponraj, K.; Gaither, K.A.; Singh, D.K.; Davydova, N.; Zhao, M.; Luo, S.; Lazarus, P.; Prasad, B.; Davydov, D.R. Non-additivity of the functional properties of individual P450 species and its manifestation in the effects of alcohol consumption on the metabolism of ketamine and amitriptyline. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2024, 230, 116569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowland, A.; Gaganis, P.; Elliot, D.J.; Mackenzie, P.I.; Knights, K.M.; Miners, J.O. Binding of inhibitory fatty acids is responsible for the enhancement of UDP-glucuronosyltransferase 2B7 activity by albumin: Implications for in vitro-in vivo extrapolation. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2007, 321, 137–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatakrishnan, K.; von Moltke, L.L.; Court, M.H.; Harmatz, J.S.; Crespi, C.L.; Greenblatt, D.J. Comparison between cytochrome P450 (CYP) content and relative activity approaches to scaling from cDNA-expressed CYPs to human liver microsomes: Ratios of accessory proteins as sources of discrepancies between the approaches. Drug Metab. Dispos. 2000, 28, 1493–1504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, M.; Li, J.; Xu, J.; Zheng, L.; Xu, S. Exploring human CYP4 enzymes: Physiological roles, function in diseases and focus on inhibitors. Drug Discov. Today 2023, 28, 103560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kater, C.E.; Giorgi, R.B.; Costa-Barbosa, F.A. Classic and current concepts in adrenal steroidogenesis: A reappraisal. Arch. Endocrinol. Metab. 2022, 66, 77–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; DuBois, R.N. Epoxyeicosatrienoic acids: A double-edged sword in cardiovascular diseases and cancer. J. Clin. Investig. 2012, 122, 19–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hossam Abdelmonem, B.; Abdelaal, N.M.; Anwer, E.K.E.; Rashwan, A.A.; Hussein, M.A.; Ahmed, Y.F.; Khashana, R.; Hanna, M.M.; Abdelnaser, A. Decoding the Role of CYP450 Enzymes in Metabolism and Disease: A Comprehensive Review. Biomedicines 2024, 12, 1467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Nikolic, D.; Chadwick, L.R.; Pauli, G.F.; van Breemen, R.B. Identification of Human Hepatic Cytochrome P450 Enzymes Involved in the Metabolism of 8-Prenylnaringenin and Isoxanthohumol from Hops (Humulus lupulus L.). Drug Metab. Dispos. 2006, 34, 1152–1159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schiffer, L.; Barnard, L.; Baranowski, E.S.; Gilligan, L.C.; Taylor, A.E.; Arlt, W.; Shackleton, C.H.L.; Storbeck, K.H. Human steroid biosynthesis, metabolism and excretion are differentially reflected by serum and urine steroid metabolomes: A comprehensive review. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2019, 194, 105439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hiroi, T.; Kishimoto, W.; Chow, T.; Imaoka, S.; Igarashi, T.; Funae, Y. Progesterone Oxidation by Cytochrome P450 2D Isoforms in the Brain. Endocrinology 2001, 142, 3901–3908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| ID | m/z | Time | Enzyme | Feature Type | Fold Change | Analysis | Proposed Formula | Proposed Ident. | Id. Level | Pair Partner (Neutral m/z) | Pair Prop. Formula |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 131.047 | 7.02 | all | substrate | 0.79 | HILIC ESI- | C4H8N2O3 | Asparagine | 1 | Metabolite, m/z 118.039, (∆= 14.0153) | C3H6N2O3 |

| 2 | 138.055 | 1.53 | 2D6 | metabolite | 1.42 | HILIC ESI- | - | - | 4 | ||

| 3 | 165.076 | 4.23 | 2C19 | metabolite | 1.13 | HILIC ESI- | C6H14O5 | L-Fucitol | 2 | Substrate m/z 150.0886 (∆ = 15.9948) | C6H14O4 |

| 4 | 171.007 | 7.04 | 2D6/2C19 | metabolite | 14.64 | HILIC ESI- | - | - | 4 | ||

| 5 | 177.005 | 7.02 | 2D6/2C19 | metabolite | 5.40 | HILIC ESI- | C6H2N4O3 | - | 4 | Substrate, m/z 192.0276, (∆ = 14.0156) | C7H4N4O3 |

| 6 | 195.051 | 6.69 | 2D6 | metabolite | 1.66 | HILIC ESI- | C6H12O7 | - | 4 | Substrates, m/z 180.0637/210.0742 (∆ = 15.9947/14.0157) | C6H12O6/C7H14O7 |

| 7 | 243.172 | 5.08 | 2C19 | metabolite | 1.63 | HILIC ESI- | C12H24N2O3 | Ile-Ile | 2 | ||

| 8 | 248.984 | 7.03 | 2D6/2C19 | metabolite | 15.06 | HILIC ESI- | - | - | 4 | ||

| 9 | 334.309 | 14.8 | 2D6 | substrate | 0.40 | RP ESI+ | C22H39NO | N-acyl-amine * | 3 | Metabolite, m/z 349.2972 (∆ = 15.9951) | C22H39NO2 |

| 10 | 359.858 | 7.84 | 2D6/2C19 | substrate | 0.63 | RP ESI+ | - | - | 4 | ||

| 11 | 368.315 | 15.98 | 2D6 | substrate | 0.18 | RP ESI+ | C22H41NO3 | N-acyl-amine * | 3 | Metabolite m/z 383.3020 (∆ = 15.9948) | C22H41NO4 |

| 12 | 374.192 | 8.43 | 2D6/2C19 | metabolite | 4.66 | RP ESI+ | - | Oligopeptide * | 3 | ||

| 13 | 382.986 | 7.01 | 2D6/2C19 | substrate | 0.49 | HILIC ESI- | - | - | 4 | ||

| 14 | 398.325 | 14.61 | 2D6 | substrate | 0.87 | RP ESI+ | C23H43NO4 | 4-Hexadecenoyl-carnitine | 2 | ||

| 15 | 412.210 | 8.19 | 2D6 | substrate | 0.53 | RP ESI+ | - | - | 4 | ||

| 16 | 417.335 | 15.08 | 2D6/2C19 | metabolite | 4.06 | RP ESI+ | C27H44O3 | 3-oxo-delta-4-steroid | 3 | Substrate m/z 400.3335 (∆ = 15.9947) | C27H44O2 |

| 17 | 425.156 | 10.02 | 2C19 | metabolite | 107.53 | RP ESI+ | - | - | 4 | ||

| 18 | 425.158 | 10.3 | 2C19 | metabolite | 32.36 | RP ESI+ | C24H24O7 | Chromone * | 3 | ||

| 19 | 447.060 | 8.17 | all | metabolite | 1.60 | HILIC ESI- | C20H16O12 | Benzoic acid ester * | 3 | ||

| 20 | 505.203 | 3.52 | 2D6 | substrate | 0.82 | HILIC ESI- | - | - | 4 | ||

| 21 | 532.283 | 15.13 | 3A4 | substrate | 0.79 | RP ESI+ | - | Phospholipid * | 3 | ||

| 22 | 547.776 | 6.68 | 2D6/2C19 | metabolite | 2.51 | HILIC ESI- | - | - | 4 | ||

| 23 | 564.437 | 16.48 | 2D6/3A4 | substrate | 0.90 | RP ESI+ | C30H62NO6P | Phosphatidyl-choline * | 3 | ||

| 24 | 576.401 | 16.03 | 2D6 | substrate | 0.82 | RP ESI+ | C30H58NO7P | Monoacylglycero-phosphocholine * | 3 | ||

| 25 | 578.421 | 16.24 | 2D6/3A4 | substrate | 0.88 | RP ESI+ | C30H60NO7P | Monoacylglycero-phosphocholine * | 3 | ||

| 26 | 659.516 | 4.79 | 2D6 | substrate | 0.68 | HILIC ESI- | - | - | 4 | ||

| 27 | 770.604 | 18.05 | 3A4 | substrate | 0.81 | RP ESI+ | C44H84NO7P | Diacylglycero-phosphocholine * | 3 | ||

| 28 | 822.639 | 18.71 | all | substrate | 0.86 | RP ESI+ | C48H88NO7P | Diacylglycero-phosphocholine * | 3 | ||

| 29 | 831.562 | 16.24 | 2D6 | substrate | 0.56 | RP ESI+ | - | Phospholipid * | 3 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wartmann, Y.; Brockbals, L.; Kraemer, T.; Steuer, A.E. Assessing the Feasibility of In Vitro Assays in Combination with Biological Matrices to Screen for Endogenous CYP450 Phenotype Biomarkers Using an Untargeted Metabolomics Approach—A Proof of Concept Study. Metabolites 2025, 15, 791. https://doi.org/10.3390/metabo15120791

Wartmann Y, Brockbals L, Kraemer T, Steuer AE. Assessing the Feasibility of In Vitro Assays in Combination with Biological Matrices to Screen for Endogenous CYP450 Phenotype Biomarkers Using an Untargeted Metabolomics Approach—A Proof of Concept Study. Metabolites. 2025; 15(12):791. https://doi.org/10.3390/metabo15120791

Chicago/Turabian StyleWartmann, Yannick, Lana Brockbals, Thomas Kraemer, and Andrea E. Steuer. 2025. "Assessing the Feasibility of In Vitro Assays in Combination with Biological Matrices to Screen for Endogenous CYP450 Phenotype Biomarkers Using an Untargeted Metabolomics Approach—A Proof of Concept Study" Metabolites 15, no. 12: 791. https://doi.org/10.3390/metabo15120791

APA StyleWartmann, Y., Brockbals, L., Kraemer, T., & Steuer, A. E. (2025). Assessing the Feasibility of In Vitro Assays in Combination with Biological Matrices to Screen for Endogenous CYP450 Phenotype Biomarkers Using an Untargeted Metabolomics Approach—A Proof of Concept Study. Metabolites, 15(12), 791. https://doi.org/10.3390/metabo15120791