Diagnosis and Management of Pediatric Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease: An Overview

Abstract

1. Introduction

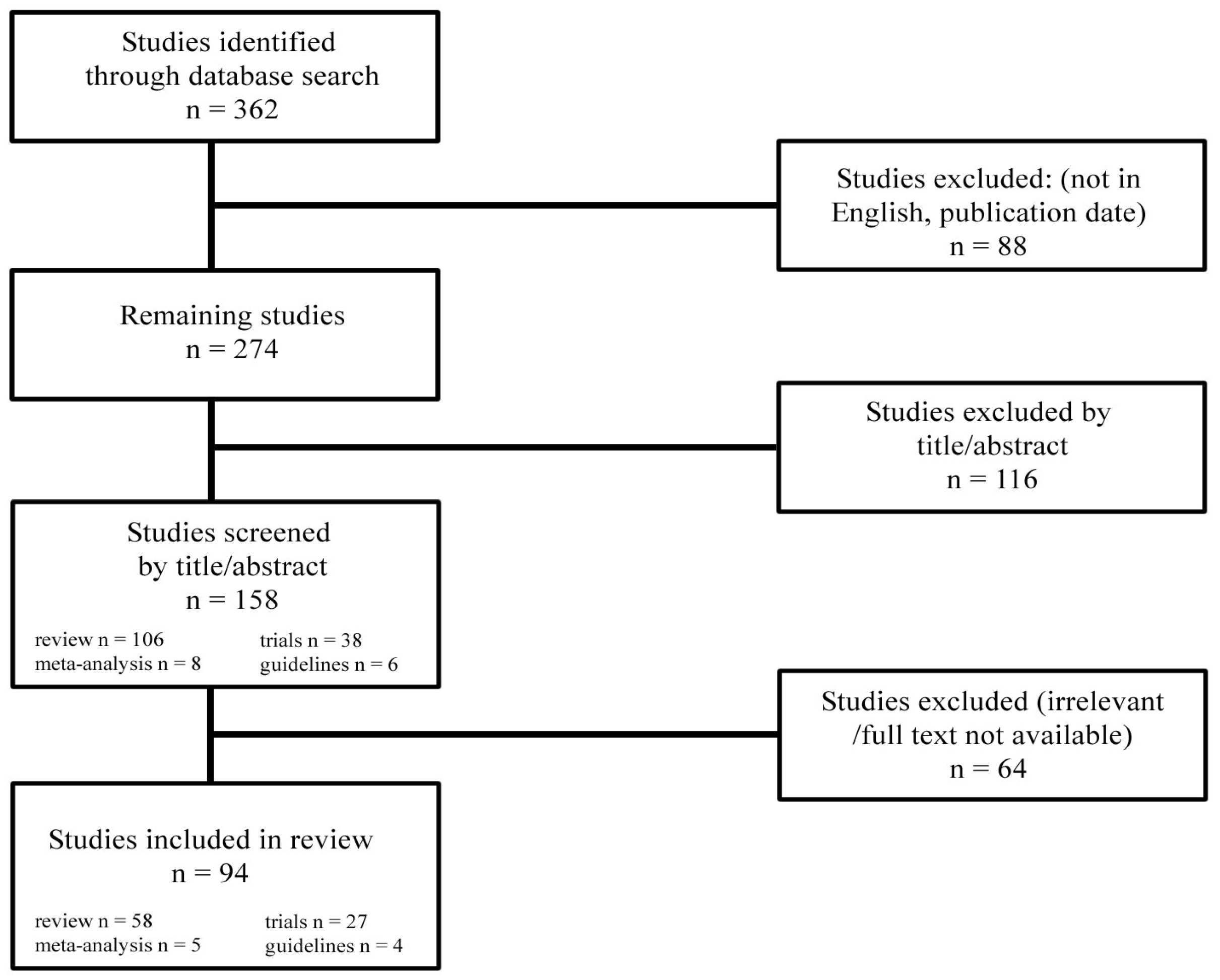

2. Materials and Methods

3. Epidemiology

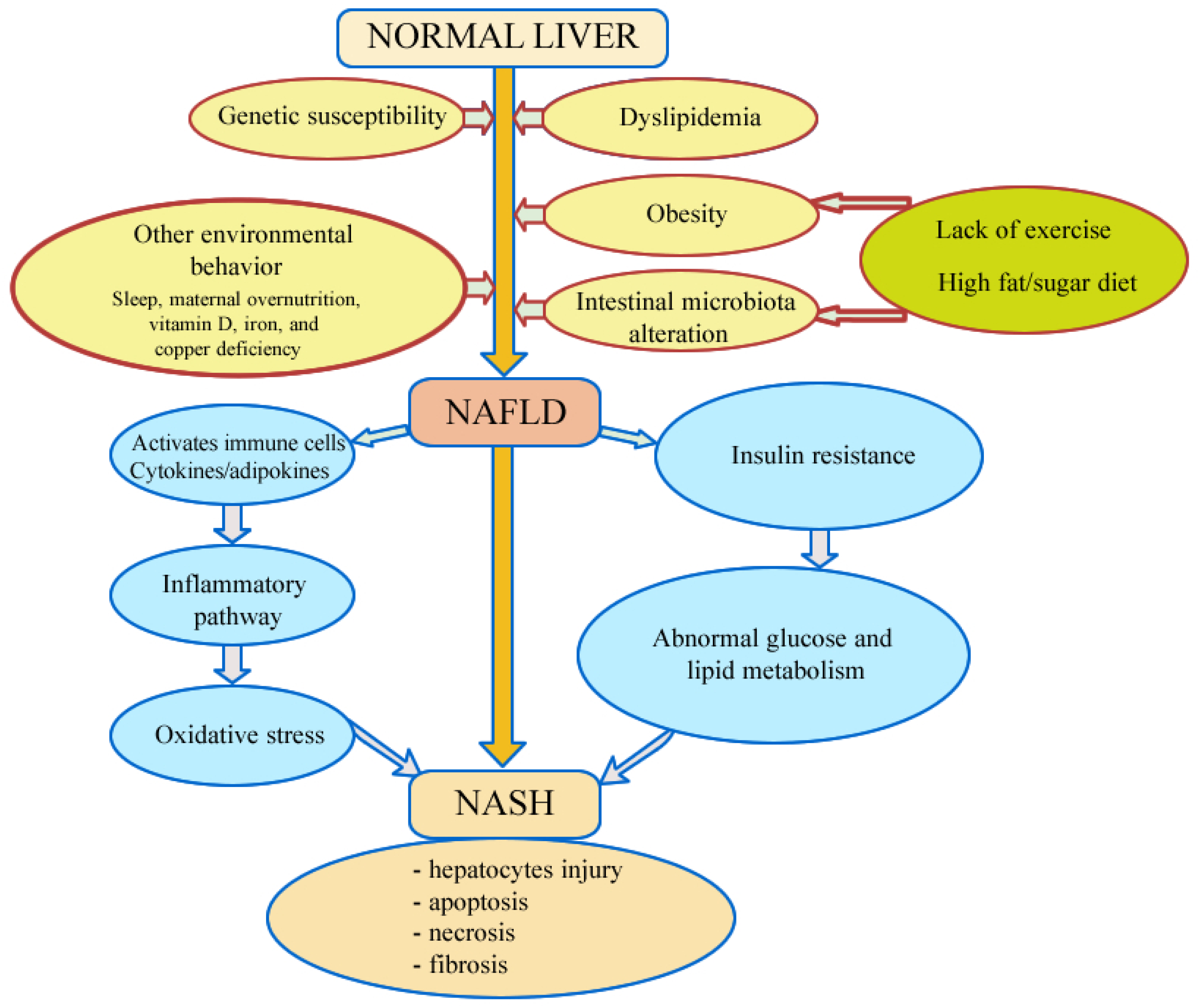

4. Pathogenesis

4.1. Insulin Resistance

4.2. Oxidative Stress

4.3. Genetic Susceptibility

4.4. The Role of Nutrients in Pediatric NAFLD

4.5. Intestinal Microbial Dysbiosis in Pediatric NAFLD

4.6. Obstructive Sleep Apnea

4.7. Other Mechanism Involved

4.8. Maternal Overnutrition and NAFLD Developmental Programming

5. Clinical Signs

6. Diagnosis

7. Differential Diagnosis

8. Biochemical Assessment

9. Imaging Methods

10. Non-Invasive Indices

11. Liver Biopsy

12. Treatment

12.1. Lifestyle Interventions

12.2. Pharmacological Approaches

12.3. Medical Therapy

12.4. Surgical Therapies

Current Limitations and Future Research Directions

13. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| NAFLD | Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease |

| MASLD | Metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease |

| NASH | Non-alcoholic steatohepatitis |

| BMI | Body mass index |

| TNF-alpha | Tumor necrosis factor-alpha |

| IL-6 | Interleukin 6 |

| CVD | Cardiovascular disease |

| DNA | Deoxyribonucleic acid |

| mRNA | Messenger ribonucleic acid |

| HSCs | Hepatic stellate cells |

| TG | Triglyceride |

| LPL | Lipoprotein lipase |

| FFA | Free fatty acids |

| ApoC-III | Apolipoprotein C-III |

| NAD | Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide |

| FAD | Flavin adenine dinucleotide |

| CYP4A | Cytochrome P450 4A |

| ROS | Cytotoxic reactive oxygen species |

| NFκB | Nuclear factor pathway κB |

| MOMP | Mitochondrial outer membrane permeabilization |

| PNPLA3 | Adiponutrin/patatin-like phospholipase domain-containing 3 |

| ALT | Alanine aminotransferase |

| AST | Aspartate aminotransferase |

| LAL | Lysosomal acid lipase |

| GCKR | Glucokinase regulatory protein |

| APOC3 | Apolipoprotein C3 |

| TM6SF2 | Human transmembrane 6 superfamily 2 |

| ChREBP | Carbohydrate response element-binding protein |

| GLUT5 | Glucose transporter protein type-5 |

| ATP | Hepatic adenosine triphosphate |

| VLDL | Very-low-density lipoprotein |

| PRRs | Pattern recognition receptors |

| TLRs | Toll-like receptors |

| NOD-like receptors | Nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain-like receptors |

| SCFAs | Short-chain fatty acids |

| ChREBP | Hepatic carbohydrate response element-binding protein |

| BCFAs | Branched-chain fatty acids |

| NO | Nitric oxide |

| H2S | Hydrogen sulfide |

| FXR | Farnesoid X receptor |

| NLRP3 | Pyrin domain-containing protein 3 |

| SEC | Sinusoidal endothelial cells |

| ADH | Insulin-dependent alcohol dehydrogenase |

| OSA | Obstructive sleep apnea |

| GOAT | Ghrelin-ghrelin O-acyltransferase |

| HFD | High-fat diet |

| PCOS | Polycystic ovary syndrome |

| MRI | Magnetic resonance imaging |

| GGT | Gamma-glutamyl transferase |

| BA | Serum bile acid |

| HOMA-IR | Homeostatic Model Assessment for Insulin Resistance |

| CK-18 | Cytokeratin 18 |

| ANAs | Anti-nuclear antibodies |

| TGR | G protein-coupled receptor |

| CAP | Controlled attenuation parameter |

| NFS | NAFLD fibrosis score |

| FIB-4 | Fibrosis-4 Index |

| AAP | American Academy of Pediatrics |

| GLP-1 | Glucagon-like peptide |

| LOXL2 | Lysyl Oxidase-like 2 |

| FDA | Food and Drug Administration |

References

- Brunt, E.M. Pathology of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2010, 7, 195–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aly, F.Z.; Kleiner, D.E. Update on fatty liver disease and steatohepatitis. Adv. Anat. Pathol. 2011, 18, 294–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giorgio, V.; Prono, F.; Graziano, F.; Nobili, V. Pediatric non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: Old and new concepts on development, progression, metabolic insight and potential treatment targets. BMC Pediatr. 2013, 13, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sweeny, K.F.; Lee, C.K. Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease in Children. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2021, 17, 579–587. [Google Scholar]

- Alisi, A.; Feldstein, A.E.; Villani, A.; Raponi, M.; Nobili, V. Pediatric nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: A multidisciplinary approach. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2012, 9, 152–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Day, C.P. Genetic and environmental susceptibility to non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Dig. Dis. 2010, 28, 255–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwimmer, J.B.; Pardee, P.E.; Lavine, J.E.; Blumkin, A.K.; Cook, S. Cardiovascular risk factors and the metabolic syndrome in pediatric nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Circulation 2008, 118, 277–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelishadi, R.; Cook, S.R.; Adibi, A.; Faghihimani, Z.; Ghatrehsamani, S.; Beihaghi, A. Association of the components of the metabolic syndrome with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease among normal-weight, overweight and obese children and adolescents. Diabetol. Metab. Syndr. 2009, 1, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Louthan, M.V.; Theriot, J.A.; Zimmerman, E.; Stutts, J.T.; McClain, C.J. Decreased prevalence of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in black obese children. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 2005, 41, 426–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, A. Pediatric Fatty Liver Disease. Mo Med. 2019, 116, 123–128. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Accacha, S.; Barillas-Cerritos, J.; Srivastava, A.; Ross, F.; Drewes, W.; Gulkarov, S.; De Leon, J.; Reiss, A.B. From Childhood Obesity to Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Steatotic Liver Disease (MASLD) and Hyperlipidemia Through Oxidative Stress During Childhood. Metabolites 2025, 15, 287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Poustchi, H.; George, J.; Esmaili, S.; Esna-Ashari, F.; Ardalan, G.; Sepanlou, S.G. Gender differences in healthy ranges for serum alanine aminotransferase levels in adolescence. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e21178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loomba, R.; Sirlin, C.B.; Schwimmer, J.B.; Lavine, J.E. Advances in pediatric nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatology 2009, 50, 1282–1293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lobanova, Y.S.; Scherbakov, A.M.; Shatskaya, V.A.; Evteev, V.A.; Krasil’nikov, M.A. NF-kappaB suppression provokes the sensitization of hormone-resistant breast cancer cells to estrogen apoptosis. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 2009, 324, 65–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, J.W.; Gong, J.; Chang, X.M.; Luo, J.Y.; Dong, L.; Jia, A. Effects of estradiol on liver estrogen receptor-alpha and its mRNA expression in hepatic fibrosis in rats. World J. Gastroenterol. 2004, 10, 250–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, E.J.; Choi, M.; Ahn, S.B.; Yoo, J.J.; Kang, S.H.; Cho, Y.; Song, D.S.; Koh, H.; Jun, D.W.; Lee, H.W. Prevalence of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in pediatrics and adolescents: A systematic review and meta-analysis. World J. Pediatr. 2024, 20, 569–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, E.L.; Howe, L.D.; Jones, H.E.; Higgins, J.P.; Lawlor, D.A.; Fraser, A. The Prevalence of Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease in Children and Adolescents: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0140908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Mandala, A.; Janssen, R.C.; Palle, S.; Short, K.R.; Friedman, J.E. Pediatric Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease: Nutritional Origins and Potential Molecular Mechanisms. Nutrients 2020, 12, 3166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Katsagoni, C.N.; Papachristou, E.; Sidossis, A.; Sidossis, L. Effects of dietary and lifestyle interventions on liver, clinical and metabolic parameters in children and adolescents with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: A systematic review. Nutrients 2020, 12, 2864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zdanowicz, K.; Bialokoz-Kalinowska, I.; Lebensztejn, D.M. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in non-obese children. Hong Kong Med. J. 2020, 26, 459–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Sessa, A.; Cirillo, G.; Guarino, S.; Marzuillo, P.; Miraglia Del Giudice, E. Pediatric non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: Current perspectives on diagnosis and management. Pediatric. Health Med. Ther. 2019, 10, 89–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Clemente, M.G.; Mandato, C.; Poeta, M.; Vajro, P. Pediatric non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: Recent solutions, unresolved issues, and future research directions. World J. Gastroenterol. 2016, 22, 8078–8093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Povero, D.; Feldstein, A.E. Novel Molecular Mechanisms in the Development of Non-Alcoholic Steatohepatitis. Diabetes Metab. J. 2016, 40, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farooqi, I.S.; O’Rahilly, S. Leptin: A pivotal regulator of human energy homeostasis. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2009, 89, 980S–984S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reinehr, T.; Kratzsch, J.; Kiess, W.; Andler, W. Circulating soluble leptin receptor, leptin, and insulin resistance before and after weight loss in obese children. Int. J. Obes. 2005, 29, 1230–1235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cambuli, V.M.; Musiu, M.C.; Incani, M.; Paderi, M.; Serpe, R.; Marras, V. Assessment of adiponectin and leptin as biomarkers of positive metabolic outcomes after lifestyle intervention in overweight and obese children. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2008, 93, 3051–3057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reilly, M.P.; Lehrke, M.; Wolfe, M.L.; Rohatgi, A.; Lazar, M.A.; Rader, D.J. Resistin is an inflammatory marker of atherosclerosis in humans. Circulation 2005, 111, 932–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shai, I.; Schulze, M.B.; Manson, J.E.; Rexrode, K.M.; Stampfer, M.J.; Mantzoros, C.; Hu, F.B. A prospective study of soluble tumor necrosis factor-alpha receptor II (sTNF-RII) and risk of coronary heart disease among women with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care 2005, 28, 1376–1382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reinehr, T.; Stoffel-Wagner, B.; Roth, C.L.; Andler, W. High-sensitive C-reactive protein, tumor necrosis factor alpha, and cardiovascular risk factors before and after weight loss in obese children. Metabolism 2005, 54, 1155–1161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelishadi, R.; Mirghaffari, N.; Poursafa, P.; Gidding, S.S. Lifestyle and environmental factors associated with inflammation, oxidative stress and insulin resistance in children. Atherosclerosis 2009, 203, 311–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buzzetti, E.; Pinzani, M.; Tsochatzis, E.A. The multiple-hit pathogenesis of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD). Metabolism 2016, 65, 1038–1048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goyal, N.P.; Schwimmer, J.B. The Progression and Natural History of Pediatric Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. Clin. Liver Dis. 2016, 20, 325–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vacca, M.; Allison, M.; Griffin, J.L.; Vidal-Puig, A. Fatty Acid and Glucose Sensors in Hepatic Lipid Metabolism: Implications in NAFLD. Semin. Liver Dis. 2015, 35, 250–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nassir, F.; Rector, R.S.; Hammoud, G.M.; Ibdah, J.A. Pathogenesis and Prevention of Hepatic Steatosis. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2015, 11, 167–175. [Google Scholar]

- Pirgon, Ö.; Bilgin, H.; Çekmez, F.; Kurku, H.; Dündar, B.N. Association between insulin resistance and oxidative stress parameters in obese adolescents with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. J. Clin. Res. Pediatr. Endocrinol. 2013, 5, 33–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashraf, N.U.; Sheikh, T.A. Endoplasmic reticulum stress and oxidative stress in the pathogenesis of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Free Radic. Res. 2015, 49, 1405–1418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lotowska, J.M.; Sobaniec-Lotowska, M.E.; Bockowska, S.B.; Lebensztejn, D.M. Pediatric non-alcoholic steatohepatitis: The first report on the ultrastructure of hepatocyte mitochondria. World J. Gastroenterol. 2014, 20, 4335–4340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berardis, S.; Sokal, E. Pediatric non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: An increasing public health issue. Eur. J. Pediatr. 2014, 173, 131–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Adamo, E.; Castorani, V.; Nobili, V. The liver in children with metabolic syndrome. Front. Endocrinol. 2019, 10, 514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubuquoy, C.; Burnol, A.F.; Moldes, M. PNPLA3, a genetic marker of progressive liver disease, still hiding its metabolic function? Clin. Res. Hepatol. Gastroenterol. 2013, 37, 30–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selvakumar, P.K.; Kabbany, M.N.; Lopez, R.; Tozzi, G.; Alisi, A.; Alkhouri, N.; Nobili, V. Reduced lysosomal acid lipase activity-A potential role in the pathogenesis of non alcoholic fatty liver disease in pediatric patients. Dig. Liver Dis. 2016, 48, 909–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tovoli, F.; Napoli, L.; Negrini, G.; D’Addato, S.; Tozzi, G.; D’Amico, J.; Piscaglia, F.; Bolondi, L. A relative deficiency of lysosomal acid lypase activity characterizes non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017, 18, 1134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goffredo, M.; Caprio, S.; Feldstein, A.E.; D’Adamo, E.; Shaw, M.M.; Pierpont, B.; Savoye, M.; Zhao, H.; Bale, A.E.; Santoro, N. Role of TM6SF2 rs58542926 in the pathogenesis of nonalcoholic pediatric fatty liver disease: A multiethnic study. Hepatology 2016, 63, 117–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossi, F.; Bellini, G.; Alisi, A.; Alterio, A.; Maione, S.; Perrone, L. Cannabinoid Receptor Type 2 Functional Variant Influences Liver Damage in Children with Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e42259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vos, M.B.; Lavine, J.E. Dietary fructose in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatology 2013, 57, 2525–2531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moore, J.B.; Gunn, P.J.; Fielding, B.A. The role of dietary sugars and de novo lipogenesis in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Nutrients 2014, 6, 5679–5703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eurtsen, M.L.; Santos, S.; Gaillard, R.; Felix, J.F.; Jaddoe, V.W.V. Associations between intake of sugar-containing beverages in infancy with liver fat accumulation at school age. Hepatology 2021, 73, 560–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sullivan, J.S.; Le, M.T.; Pan, Z.; Rivard, C.; Love-Osborne, K.; Robbins, K.; Johnson, R.J.; Sokol, R.J.; Sundaram, S.S. Oral fructose absorption in obese children with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Pediatr. Obes. 2015, 10, 188–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vajro, P.; Paolella, G.; Fasano, A. Microbiota and gut-liver axis: Their influences on obesity and obesity-related liver disease. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 2013, 56, 461–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baffy, G. Potential mechanisms linking gut microbiota and portal hypertension. Liver Int. 2019, 39, 598–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fang, Y.L.; Chen, H.; Wang, C.L.; Liang, L. Pathogenesis of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in children and adolescence: From “two hit theory” to “multiple hit model”. World J. Gastroenterol. 2018, 24, 2974–2983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kirpich, I.A.; Marsano, L.S.; McClain, C.J. Gut-liver axis, nutrition, and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Clin. Biochem. 2015, 48, 923–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Donia, M.S.; Fischbach, M.A. Small molecules from the human microbiota. Science 2015, 349, 1254766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Schubert, K.; Olde Damink, S.; von Bergen, M.; Schaap, F.G. Interactions between bile salts, gut microbiota, and hepatic innate immunity. Immunol. Rev. 2017, 279, 23–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guercio Nuzio, S.; Di Stasi, M.; Pierri, L.; Troisi, J.; Poeta, M.; Bisogno, A.; Belmonte, F.; Tripodi, M.; Di Salvio, D.; Massa, G.; et al. Multiple gut-liver axis abnormalities in children with obesity with and without hepatic involvement. Pediatr. Obes. 2017, 12, 446–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Engstler, A.J.; Aumiller, T.; Degen, C.; Dürr, M.; Weiss, E.; Maier, I.B.; Schattenberg, J.M.; Jin, C.J.; Sellmann, C.; Bergheim, I. Insulin resistance alters hepatic ethanol metabolism: Studies in mice and children with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Gut 2016, 65, 1564–1571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pădureanu, V.; Dop, D.; Drăgoescu, A.N.; Pădureanu, R.; Mușetescu, A.E.; Nedelcu, L. Non alcoholic fatty liver disease and hematologic manifestations (Review). Exp. Ther. Med. 2021, 22, 1355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Zhang, S.; Huang, Y.; Chen, K. Sleep duration and obesity in children: A systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. J. Paediatr. Child Health 2017, 53, 378–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shetty, A.; Hsu, J.W.; Manka, P.P.; Syn, W.K. Role of the circadian clock in the metabolic syndrome and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Dig. Dis. Sci. 2018, 63, 3187–3206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kettner, N.M.; Voicu, H.; Finegold, M.J.; Coarfa, C.; Sreekumar, A.; Putluri, N.; Katchy, C.A.; Lee, C.; Moore, D.D.; Fu, L. Circadian homeostasis of liver metabolism suppresses hepatocarcinogenesis. Cancer Cell 2016, 30, 909–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.-D.; Chen, M.-X.; Chen, G.-P.; Lin, X.-J.; Huang, J.-F.; Zeng, A.-M.; Huang, Y.-P.; Lin, Q.-C. Association between obstructive sleep apnea and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in pediatric patients: A meta-analysis. Pediatr. Obes. 2021, 16, e12718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parola, M.; Vajro, P. Nocturnal hypoxia in obese-related obstructive sleep apnea as a putative trigger of oxidative stress in pediatric NAFLD progression. J. Hepat. 2016, 65, 470–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sundaram, S.S.; Swiderska-Syn, M.; Sokol, R.J.; Halbower, A.C.; Capocelli, K.E.; Pan, Z.; Robbins, K.; Graham, B.; Diehl, A.M. Nocturnal hypoxia activation of the hedgehog signaling pathway affects pediatric nonalcoholic fatty liver disease severity. Hepatol. Commun. 2019, 3, 883–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nobili, V.; Cutrera, R.; Liccardo, D.; Pavone, M.; Devito, R.; Giorgio, V.; Verrillo, E.; Baviera, G.; Musso, G. Obstructive sleep apnea syndrome affects liver histology and inflammatory cell activation in pediatric nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, regardless of obesity/insulin resistance. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2014, 189, 66–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feldman, A.; Aigner, E.; Weghuber, D.; Paulmichl, K. The Potential Role of Iron and Copper in Pediatric Obesity and Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. BioMed Res. Int. 2015, 2015, 287401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Zhang, S.R.; Fan, X.M. Ghrelin-ghrelin O-acyltransferase system in the pathogenesis of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. World J. Gastroenterol. 2015, 21, 3214–3222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Eliades, M.; Spyrou, E.; Agrawal, N.; Lazo, M.; Brancati, F.L.; Potter, J.J.; Koteish, A.A.; Clark, J.M.; Guallar, E.; Hernaez, R. Meta-analysis: Vitamin D and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2013, 38, 246–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hourigan, S.K.; Abrams, S.; Yates, K.; Pfeifer, K.; Torbenson, M.; Murray, K.; Roth, C.L.; Kowdley, K.; Scheimann, A.O.; on behalf of the NASH CRN. Relation between vitamin D status and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in children. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 2015, 60, 396–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Medrano, M.; Arenaza, L.; Migueles, J.H.; Rodríguez-Vigil, B.; Ruiz, J.R.; Labayen, I. Associations of physical activity and fitness with hepatic steatosis, liver enzymes, and insulin resistance in children with overweight/obesity. Pediatr. Diabetes 2020, 21, 565–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karaivazoglou, K.; Kalogeropoulou, M.; Assimakopoulos, S.; Triantos, C. Psychosocial Issues in Pediatric Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. Psychosomatics 2019, 60, 10–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newton, K.P.; Feldman, H.S.; Chambers, C.D.; Wilson, L.; Behling, C.; Clark, J.M.; Molleston, J.P.; Chalasani, N.; Sanyal, A.J.; Fishbein, M.H.; et al. Low and high birth weights are risk factors for nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in children. J. Pediatr. 2017, 187, 141–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCurdy, C.E.; Bishop, J.M.; Williams, S.M.; Grayson, B.E.; Smith, M.S.; Friedman, J.E.; Grove, K.L. Maternal high-fat diet triggers lipotoxicity in the fetal livers of nonhuman primates. J. Clin. Investig. 2009, 119, 323–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonsembiante, L.; Targher, G.; Maffeis, C. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in obese children and adolescents: A role for nutrition? Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2022, 76, 28–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vos, M.B.; Abrams, S.H.; Barlow, S.E.; Caprio, S.; Daniels, S.R.; Kohli, R.; Mouzaki, M.; Sathya, P.; Schwimmer, J.B.; Sundaram, S.S.; et al. NASPGHAN clinical practice guideline for the diagnosis and treatment of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in children: Recommendations from the Expert Committee on NAFLD (ECON) and the North American Society of Pediatric Gastroen-terology, Hepatology and Nutrition (NASPGHAN). J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 2017, 64, 319–334. [Google Scholar]

- Brecelj, J.; Orel, R. Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease in Children. Medicina 2021, 57, 719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Cheung, R. Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease in Children: Where Are We? Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2022, 20, 2210–2215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Antonucci, L.; Porcu, C.; Iannucci, G.; Balsano, C.; Barbaro, B. Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease and Nutritional Implications: Special Focus on Copper. Nutrients 2017, 9, 1137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suri, A.; Song, E.; van Nispen, J.; Voigt, M.; Armstrong, A.; Murali, V.; Jain, A. Advances in the Epidemiology, Diagnosis, and Management of Pediatric Fatty Liver Disease. Clin. Ther. 2021, 43, 438–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barlow, S.E. Expert Committee. Expert committee recommendations regarding the prevention, assessment, and treatment of child and adolescent overweight and obesity: Summary report. Pediatrics 2007, 120 (Suppl. S4), S164–S192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anania, C.; Perla, F.M.; Olivero, F.; Pacifico, L.; Chiesa, C. Mediterranean diet and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. World J. Gastroenterol. 2018, 24, 2083–2094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medrano, M.; Cadenas-Sanchez, C.; Alvarez-Bueno, C.; Cavero-Redondo, I.; Ruiz, J.R.; Ortega, F.B.; Labayen, I. Evidence-Based Exercise Recommendations to Reduce Hepatic Fat Content in Youth- a Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Prog. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2018, 61, 222–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xanthakos, S.A.; Lavine, J.E.; Yates, K.P.; Schwimmer, J.B.; Molleston, J.P.; Rosenthal, P.; Murray, K.F.; Vos, M.B.; Jain, A.K.; Scheimann, A.O.; et al. Progression of fatty liver disease in children receiving standard of care lifestyle advice. Gastroenterology 2020, 159, 1731–1751.e10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luger, M.; Kruschitz, R.; Kienbacher, C.; Traussnigg, S.; Langer, F.B.; Schindler, K.; Würger, T.; Wrba, F.; Trauner, M.; Prager, G.; et al. Prevalence of Liver Fibrosis and its Association with Non-invasive Fibrosis and Metabolic Markers in Morbidly Obese Patients with Vitamin D Deficiency. Obes. Surg. 2016, 26, 2425–2432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boyraz, M.; Pirgon, Ö.; Dündar, B.; Çekmez, F.; Hatipoğlu, N. Long-Term Treatment with n-3 Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids as a Monotherapy in Children with Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. J. Clin. Res. Pediatr. Endocrinol. 2015, 7, 121–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vajro, P.; Veropalumbo, C.; D’Aniello, R.; Mandato, C. Probiotics in the treatment of non alcoholic fatty liver disease: Further evidence in obese children. Nutr. Metab. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2013, 23, e9–e10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dop, D.; Marcu, I.R.; Padureanu, V.; Caragea, D.C.; Padureanu, R.; Niculescu, S.A.; Niculescu, C.E. Clostridium difficile infection in pediatric patients. Biomed. Rep. 2024, 20, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vajro, P.; Mandato, C.; Licenziati, M.R.; Franzese, A.; Vitale, D.F.; Lenta, S.; Caropreso, M.; Vallone, G.; Meli, R. Effects of Lactobacillus rhamnosus strain GG in pediatric obesity-related liver disease. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 2011, 52, 740–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Famouri, F.; Shariat, Z.; Hashemipour, M.; Keikha, M.; Kelishadi, R. Effects of probiotics on nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in obese children and adolescents. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 2017, 64, 413–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liyanagedera, S.; Williams, R.P.; Veraldi, S.; Nobili, V.; Mann, J.P. The pharmacological management of NAFLD in children and adolescents. Expert Rev. Clin. Pharmacol. 2017, 10, 1225–1237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mann, J.P.; Tang, G.Y.; Nobili, V.; Armstrong, M.J. Evaluations of Lifestyle, Dietary, and Pharmacologic Treatments for Pediatric Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease: A Systematic Review. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2019, 17, 1457–1476.e1457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Zhao, X.; Ran, L.; Wan, J.; Wang, X.; Qin, Y.; Shu, F.; Gao, Y.; Yuan, L.; Zhang, Q. Resveratrol improves insulin resistance, glucose and lipid metabolism in patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: A randomized controlled trial. Dig. Liver Dis. 2015, 47, 226–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zein, C.O.; Yerian, L.M.; Gogate, P.; Lopez, R.; Kirwan, J.P.; Feldstein, A.E.; McCullough, A.J. Pentoxifylline improves nonalcoholic steatohepatitis: A randomized placebo-controlled trial. Hepatology 2011, 54, 1610–1619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takeshita, Y.; Takamura, T.; Honda, M.; Kita, Y.; Zen, Y.; Kato, K.; Misu, H.; Ota, T.; Nakamura, M.; Yamada, K. The effects of ezetimibe on non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and glucose metabolism: A randomised controlled trial. Diabetologia 2014, 57, 878–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fujio, A.; Kawagishi, N.; Echizenya, T.; Tokodai, K.; Nakanishi, C.; Miyagi, S.; Sato, K.; Fujimori, K.; Ohuchi, N. Long-term survival with growth hormone replacement after liver transplantation of pediatric nonalcoholic steatohepatitis complicating acquired hypopituitarism. Tohoku J. Exp. Med. 2015, 235, 61–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nobili, V.; Vajro, P.; Dezsofi, A.; Fischler, B.; Hadzic, N.; Jahnel, J.; Lamireau, T.; McKiernan, P.; McLin, V.; Socha, P.; et al. Indications and limitations of bariatric intervention in severely obese children and adolescents with and without nonalcoholic steatohepatitis: ESPGHAN Hepatology Committee Position Statement. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 2015, 60, 550–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Homan, M.; Kovač, J.; Orel, R.; Battelino, T.; Kotnik, P. Relevant Weight Reduction and Reversed Metabolic Co-morbidities Can Be Achieved by Duodenojejunal Bypass Liner in Adolescents with Morbid Obesity. Obes. Surg. 2020, 30, 1001–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Prevalence % in the General Population (2024) | Prevalence % of Obese Population (2024) | Prevalence % in the General Population (2015) | Prevalence % of Obese Population (2015) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall prevalence of NAFLD | 13 | 47 | 2.3 | 36.1 |

| Female | 10 | 39 | 6.3 | 21.8 |

| Male | 15 | 54 | 9 | 35.3 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Dop, D.; Pădureanu, V.; Pădureanu, R.; Niculescu, C.E.; Niculescu, Ș.A.; Marcu, I.R. Diagnosis and Management of Pediatric Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease: An Overview. Metabolites 2025, 15, 792. https://doi.org/10.3390/metabo15120792

Dop D, Pădureanu V, Pădureanu R, Niculescu CE, Niculescu ȘA, Marcu IR. Diagnosis and Management of Pediatric Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease: An Overview. Metabolites. 2025; 15(12):792. https://doi.org/10.3390/metabo15120792

Chicago/Turabian StyleDop, Dalia, Vlad Pădureanu, Rodica Pădureanu, Carmen Elena Niculescu, Ștefan Adrian Niculescu, and Iulia Rahela Marcu. 2025. "Diagnosis and Management of Pediatric Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease: An Overview" Metabolites 15, no. 12: 792. https://doi.org/10.3390/metabo15120792

APA StyleDop, D., Pădureanu, V., Pădureanu, R., Niculescu, C. E., Niculescu, Ș. A., & Marcu, I. R. (2025). Diagnosis and Management of Pediatric Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease: An Overview. Metabolites, 15(12), 792. https://doi.org/10.3390/metabo15120792