Measurement of δ1-Pyrroline-5-Carboxylic Acid in Plant Extracts for Physiological and Biochemical Studies

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Reagents

2.2. Synthesis and Purification of dl-δ1-Pyrroline-5-carboxylic Acid

2.3. Quantitative Determination of δ1-Pyrroline-5-carboxylic Acid

2.4. Plant and Cultured Cell Growth Conditions

2.5. Extraction and Quantitation of δ1-Pyrroline-5-carboxylic Acid from Plant Tissues

2.6. P5C Reductase Heterologous Expression, Purification, and Assay

2.7. Proline Dehydrogenase Extraction and Assay Methods

2.8. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

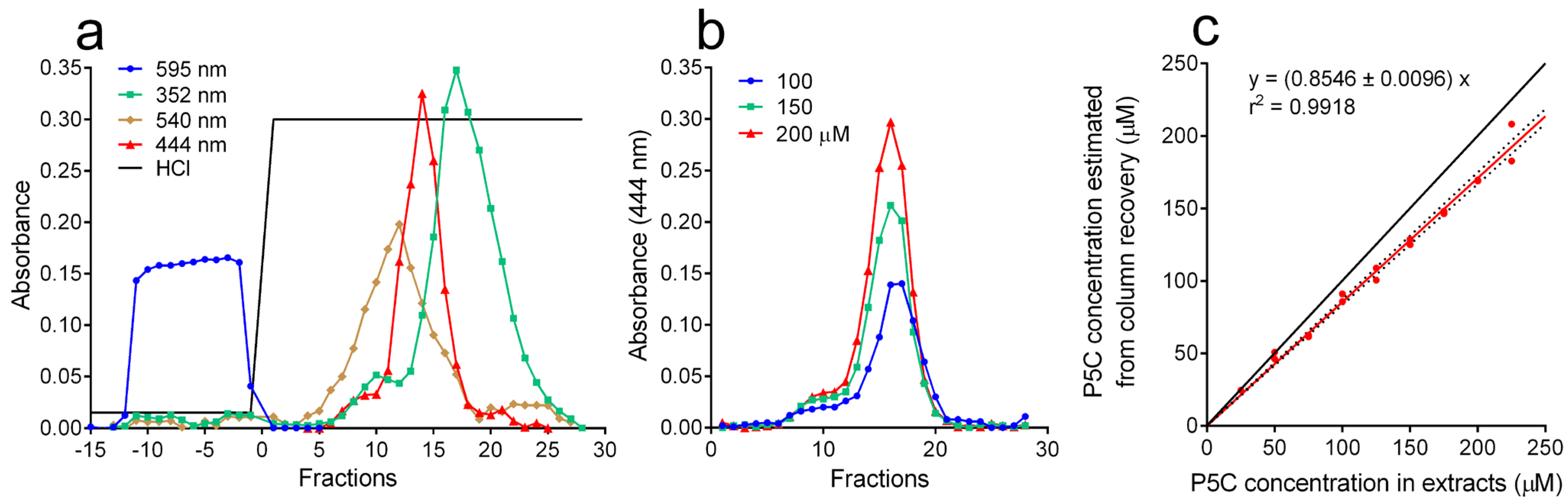

3.1. Fractionation of Extracts by Cation Exchange Chromatography Followed by the oAB Assay Allowed Detection in Plant Tissues of P5C Levels Exceeding 20 nmol g−1

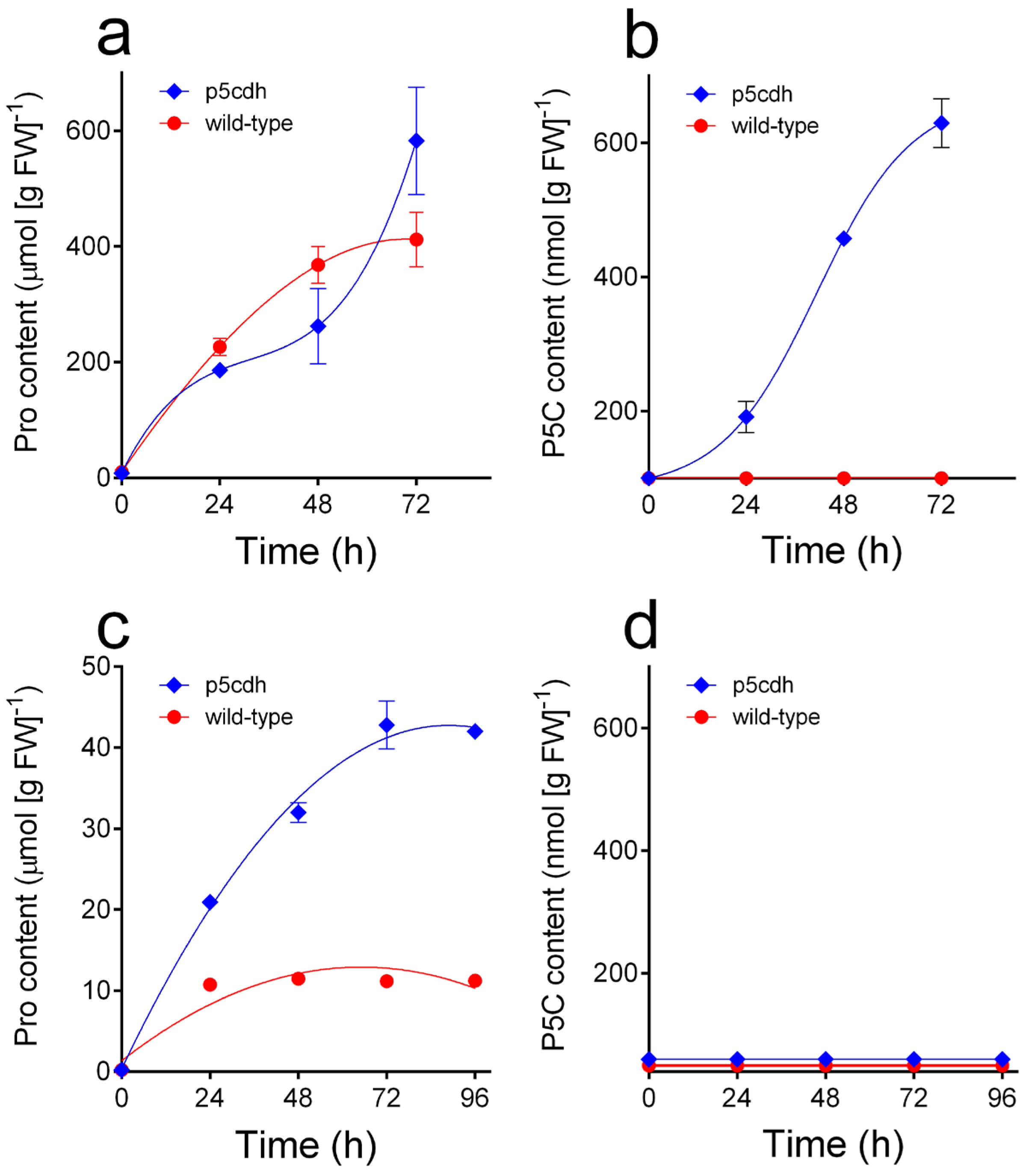

3.2. P5C Levels in Plant Tissues and Cultured Cells Were Found to Be Below the Detection Limit of the Method but Could Be Measured in Proline-Treated Seedlings of an A. thaliana p5cdh Mutant

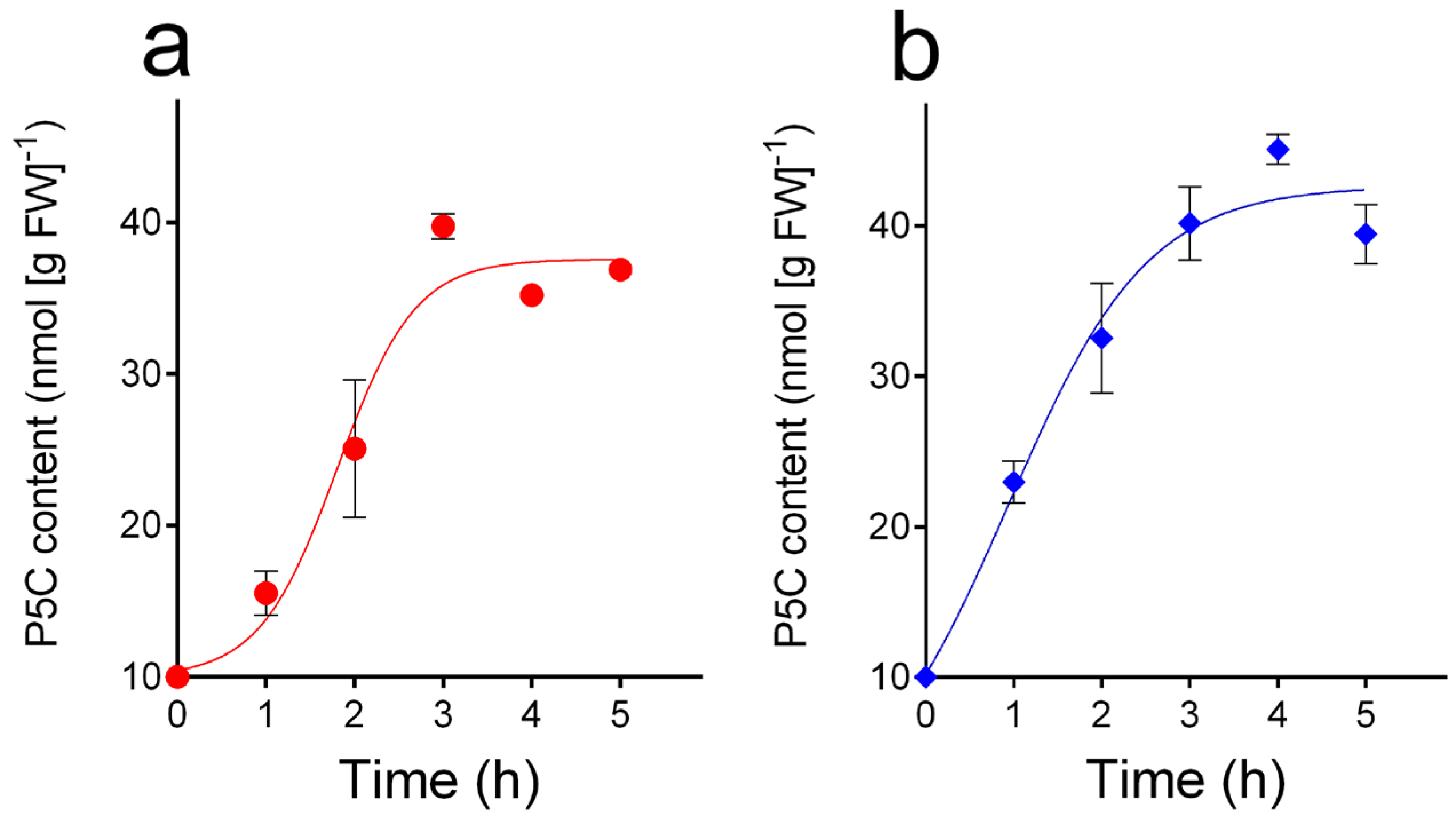

3.3. The Protocol Allowed Measurement of the Incorporation of Exogenous P5C by Suspension Cultures, Which Was Similar in A. thaliana Wild-Type and p5cdh Cells

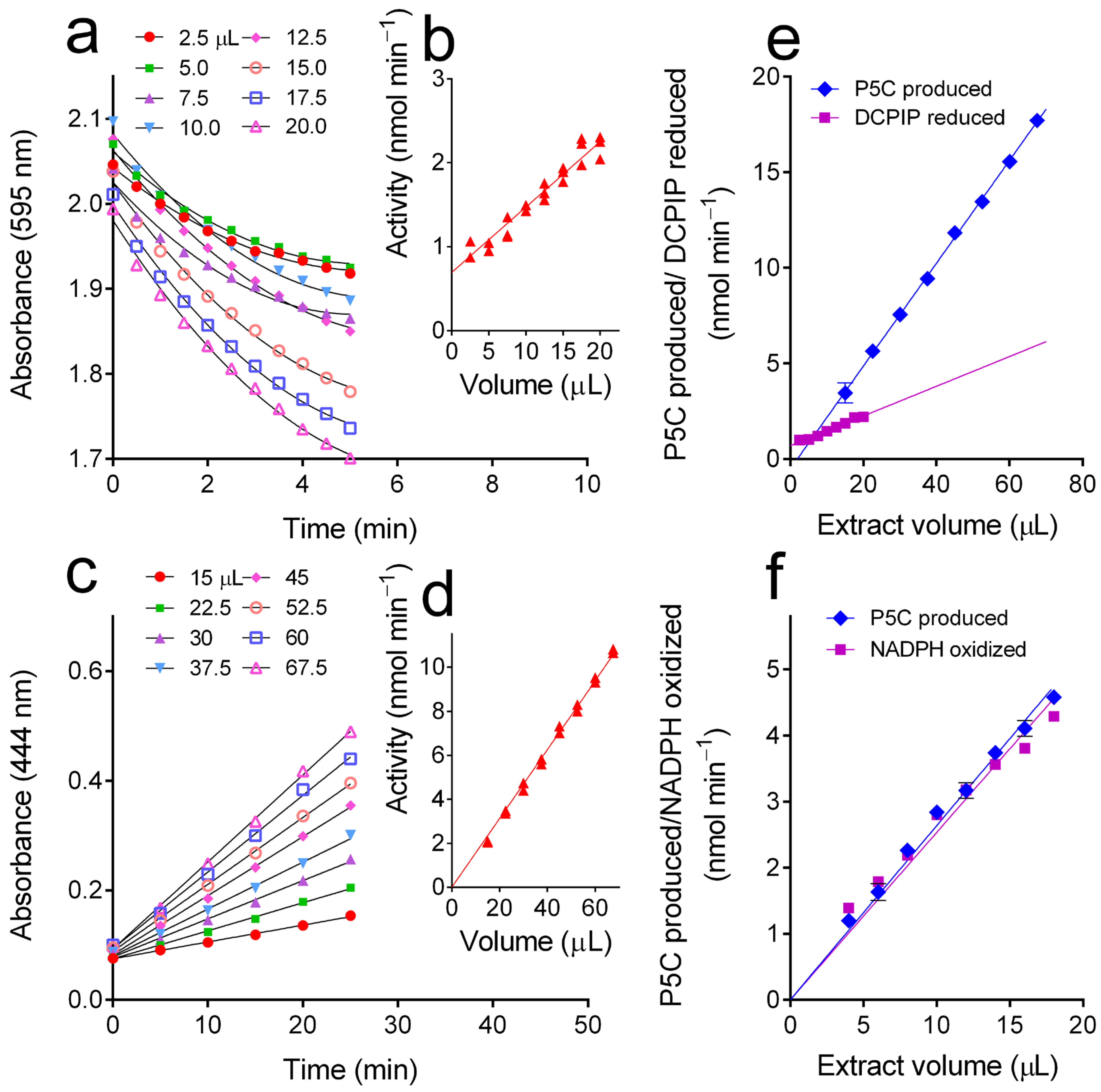

3.4. Following Sample Deproteinization with Sulphosalycilic Acid, the oAB Assay Was Found Useful to Assay ProDH, Providing More Reliable Results than the DCPIP Reduction Assay Method

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| oAB | ortho-aminobenzaldehyde |

| DCPIP | dichlorophenol indophenol |

| GSA | glutamate γ-semialdehyde |

| OAT | ornithine-δ-aminotransferase |

| P5C | δ1-pyrroline-5-carboxylic acid |

| P5CDH | δ1-pyrroline-5-carboxylate dehydrogenase |

| P5CR | δ1-pyrroline-5-carboxylate reductase |

| P5CS | δ1-pyrroline-5-carboxylate synthetase |

| PCD | programmed cell death |

| ProDH | proline dehydrogenase |

References

- Chalecka, M.; Kazberuk, A.; Palka, J.; Surazynski, A. P5C as an Interface of Proline Interconvertible Amino Acids and Its Role in Regulation of Cell Survival and Apoptosis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 11763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Becker, D.F. Connecting proline metabolism and signaling pathways in plant senescence. Front. Plant Sci. 2015, 6, 552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Forlani, G.; Sabbioni, G.; Barera, S.; Funck, D. A complex array of factors regulate the activity of Arabidopsis thaliana δ1-pyrroline-5-carboxylate synthetase isoenzymes to ensure their specific role in plant cell metabolism. Plant Cell Environ. 2024, 47, 1348–1362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fichman, Y.; Gerdes, S.Y.; Kovács, H.; Szabados, L.; Zilberstein, A.; Csonka, L.N. Evolution of proline biosynthesis: Enzymology, bioinformatics, genetics, and transcriptional regulation. Biol. Rev. Camb. Philos. Soc. 2015, 90, 1065–1099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anwar, A.; She, M.; Wang, K.; Riaz, B.; Ye, X. Biological Roles of Ornithine Aminotransferase (OAT) in Plant Stress Tolerance: Present Progress and Future Perspectives. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 3681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giberti, S.; Funck, D.; Forlani, G. Delta1-Pyrroline-5-carboxylate reductase from Arabidopsis thaliana: Stimulation or inhibition by chloride ions and feedback regulation by proline depend on whether NADPH or NADH acts as co-substrate. New Phytol. 2014, 202, 911–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schertl, P.; Cabassa, C.; Saadallah, K.; Bordenave, M.; Savouré, A.; Braun, H.P. Biochemical characterization of proline dehydrogenase in Arabidopsis mitochondria. FEBS J. 2014, 281, 2794–2804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korasick, D.A.; Končitíková, R.; Kopečná, M.; Hájková, E.; Vigouroux, A.; Moréra, S.; Becker, D.F.; Šebela, M.; Tanner, J.J.; Kopečný, D. Structural and Biochemical Characterization of Aldehyde Dehydrogenase 12, the Last Enzyme of Proline Catabolism in Plants. J. Mol. Biol. 2019, 431, 576–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, G.; Honig, A.; Stein, H.; Suzuki, N.; Mittler, R.; Zilberstein, A. Unraveling delta1-pyrroline-5-carboxylate-proline cycle in plants by uncoupled expression of proline oxidation enzymes. J. Biol. Chem. 2009, 284, 26482–26492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.; Cabassa-Hourton, C.; Planchais, S.; Lebreton, S.; Savouré, A. The proline cycle as an eukaryotic redox valve. J. Exp. Bot. 2021, 72, 6856–6866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verslues, P.E. Please, carefully, pass the P5C. J. Exp. Bot. 2024, 75, 663–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renzetti, M.; Funck, D.; Trovato, M. Proline and ROS: A Unified Mechanism in Plant Development and Stress Response? Plants 2024, 14, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hosseinifard, M.; Stefaniak, S.; Ghorbani Javid, M.; Soltani, E.; Wojtyla, Ł.; Garnczarska, M. Contribution of Exogenous Proline to Abiotic Stresses Tolerance in Plants: A Review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 5186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayat, S.; Hayat, Q.; Alyemeni, M.N.; Wani, A.S.; Pichtel, J.; Ahmad, A. Role of proline under changing environments: A review. Plant Signal Behav. 2012, 7, 1456–1466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monteoliva, M.I.; Rizzi, Y.S.; Cecchini, N.M.; Hajirezaei, M.R.; Alvarez, M.E. Context of action of proline dehydrogenase (ProDH) in the Hypersensitive Response of Arabidopsis. BMC Plant Biol. 2014, 14, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarez, M.E.; Savouré, A.; Szabados, L. Proline metabolism as regulatory hub. Trends Plant Sci. 2022, 27, 39–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qamar, A.; Mysore, K.S.; Senthil-Kumar, M. Role of proline and pyrroline-5-carboxylate metabolism in plant defense against invading pathogens. Front. Plant Sci. 2015, 6, 503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, H.J.; Ayliffe, M.A.; Rashid, K.Y.; Pryor, A.J. A rust-inducible gene from flax (fis1) is involved in proline catabolism. Planta 2006, 223, 213–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S.; Villamor, J.G.; Verslues, P.E. Essential role of tissue-specific proline synthesis and catabolism in growth and redox balance at low water potential. Plant Physiol. 2011, 157, 292–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shinde, S.; Villamor, J.G.; Lin, W.; Sharma, S.; Verslues, P.E. Proline Coordination with Fatty Acid Synthesis and Redox Metabolism of Chloroplast and Mitochondria. Plant Physiol. 2016, 172, 1074–1088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanner, J.J. Structural Biology of Proline Catabolic Enzymes. Antioxid. Redox Signal 2019, 30, 650–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanner, J.J.; Fendt, S.M.; Becker, D.F. The Proline Cycle As a Potential Cancer Therapy Target. Biochemistry 2018, 57, 3433–3444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phang, J.M. Perspectives, past, present and future: The proline cycle/proline-collagen regulatory axis. Amino Acids 2021, 53, 1967–1975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Forlani, G.; Sabbioni, G.; Ragno, D.; Petrollino, D.; Borgatti, M. Phenyl-substituted aminomethylene-bisphosphonates inhibit human P5C reductase and show antiproliferative activity against proline-hyperproducing tumour cells. J. Enzyme Inhib. Med. Chem. 2021, 36, 1248–1257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, C.A. Isozymes of P5C reductase (PYCR) in human diseases: Focus on cancer. Amino Acids 2021, 53, 1835–1840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Funck, D.; Winter, G.; Baumgarten, L.; Forlani, G. Requirement of proline synthesis during Arabidopsis reproductive development. BMC Plant Biol. 2012, 12, 191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.; Cabassa-Hourton, C.; Eubel, H.; Chevreux, G.; Lignieres, L.; Crilat, E.; Braun, H.P.; Lebreton, S.; Savouré, A. Pyrroline-5-carboxylate metabolism protein complex detected in Arabidopsis thaliana leaf mitochondria. J. Exp. Bot. 2024, 75, 917–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, I.; Frank, L. Improved chemical synthesis and enzymatic assay of delta-1-pyrroline-5-carboxylic acid. Anal. Biochem. 1975, 64, 85–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giberti, S.; Bertazzini, M.; Liboni, M.; Berlicki, L.; Kafarski, P.; Forlani, G. Phytotoxicity of aminobisphosphonates targeting both delta1-pyrroline-5-carboxylate reductase and glutamine synthetase. Pest. Manag. Sci. 2017, 73, 435–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fekkes, D. State-of-the-art of high-performance liquid chromatographic analysis of amino acids in physiological samples. J. Chromatogr. B Biomed. Appl. 1996, 682, 3–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, S.A.; Strydom, D.J. Amino acid analysis utilizing phenylisothiocyanate derivatives. Anal. Biochem. 1988, 174, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drnevich, D.; Vary, T.C. Analysis of physiological amino acids using dabsyl derivatization and reversed-phase liquid chromatography. J. Chromatogr. 1993, 613, 137–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bian, X.; Zhou, N.; Zhao, Y.; Fang, Y.; Li, N.; Zhang, X.; Wang, X.; Li, Y.; Wu, J.L.; Zhou, T. Identification of proline, 1-pyrroline-5-carboxylate and glutamic acid as biomarkers of depression reflecting brain metabolism using carboxylomics, a new metabolomics method. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2023, 77, 196–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Merx, J.; van Outersterp, R.E.; Engelke, U.F.H.; Hendriks, V.; Wevers, R.A.; Huigen, M.; Waterval, H.; Körver-Keularts, I.; Mecinović, J.; Rutjes, F.; et al. Identification of Δ1-pyrroline-5-carboxylate derived biomarkers for hyperprolinemia type II. Commun. Biol. 2022, 5, 997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Forlani, G.; Funck, D. A Specific and Sensitive Enzymatic Assay for the Quantitation of L-Proline. Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 11, 582026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Forlani, G.; Bertazzini, M.; Zarattini, M.; Funck, D. Functional characterization and expression analysis of rice delta1-pyrroline-5-carboxylate dehydrogenase provide new insight into the regulation of proline and arginine catabolism. Front. Plant Sci. 2015, 6, 591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forlani, G.; Bertazzini, M.; Zarattini, M.; Funck, D.; Ruszkowski, M.; Nocek, B. Functional properties and structural characterization of rice delta1-pyrroline-5-carboxylate reductase. Front. Plant Sci. 2015, 6, 565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deuschle, K.; Funck, D.; Forlani, G.; Stransky, H.; Biehl, A.; Leister, D.; van der Graaff, E.; Kunze, R.; Frommer, W.B. The role of [Delta]1-pyrroline-5-carboxylate dehydrogenase in proline degradation. Plant Cell 2004, 16, 3413–3425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murashige, T.; Skoog, F. A Revised Medium for Rapid Growth and Bio Assays with Tobacco Tissue Cultures. Physiol. Plantarum 1962, 15, 473–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradford, M.M. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal. Biochem. 1976, 72, 248–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Funck, D.; Eckard, S.; Müller, G. Non-redundant functions of two proline dehydrogenase isoforms in Arabidopsis. BMC Plant Biol. 2010, 10, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lebreton, S.; Cabassa-Hourton, C.; Savoure, A.; Funck, D.; Forlani, G. Appropriate Activity Assays Are Crucial for the Specific Determination of Proline Dehydrogenase and Pyrroline-5-Carboxylate Reductase Activities. Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 11, 602939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Ninhydrin Assay | oAB Assay | |

|---|---|---|

| molar extinction coefficient | 4600 M−1 cm−1 at 540 nm | 2940 M−1 cm−1 at 444 nm |

| sensitivity 1 | about 670 μM | about 75 μM |

| specificity | low | high |

| optimal solvent for cell extraction | 3% (w/v) sulfosalicylic acid | 50 mM HCl |

| solvent required for the assay | glacial acetic acid | ethanol |

| assay temperature | 50 °C | room temperature |

| time for colour development | 20 min | 15 min |

| possible interferences | most amino acids react under the same conditions, even if to a lesser extent | proteins may precipitate due to the presence of 50% ethanol in the reaction mixture |

| pre-requisites | resolution from all other free amino acids | sample deproteinization |

| P5C Assay | DCPIP Assay | NAD(P)H Assay | |

|---|---|---|---|

| molar extinction coefficient | 2940 M−1 cm−1 at 444 nm | about 20,000 M−1 cm−1 at 595 nm, depending on pH | 6220 M−1 cm−1 at 340 nm |

| reaction measured | direct | direct | coupled: need the addition of purified P5CR (or P5CDH 1) |

| type of assay | discontinuous; requires sample deproteinization before oAB addition | continuous | discontinuous; requires absence or heat inactivation of endogenous P5CDH before the addition of P5CR and NADPH |

| reaction measured | physiological | artificial | physiological |

| linearity with time | good | poor | good |

| sensitivity | lower | higher | lower |

| time required for the assay | from 30 to 60 min | from 10 to 20 min | from 45 to 90 min |

| possible interferences | none in desalted extracts | presence of endogenous dehydrogenases able to re-oxidate DCPIP; partial transfer of electrons from ProDH to the respiratory chain | none in desalted extracts |

| pre-requisites | desalting step to remove NAD(P)(H), whose presence could allow endogenous P5CR/P5CDH to further metabolize the P5C produced by ProDH | complete inhibition of dehydrogenases able to use reduced DCPIP as an electron donor; complete inhibition of electron transfer from ProDH to the respiratory chain | availability of purified P5CR/P5CDH; desalting step to remove NAD(P)(H), whose presence could allow endogenous P5CR/P5CDH to further metabolize the P5C produced by ProDH |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Forlani, G.; Trupia, F. Measurement of δ1-Pyrroline-5-Carboxylic Acid in Plant Extracts for Physiological and Biochemical Studies. Metabolites 2025, 15, 777. https://doi.org/10.3390/metabo15120777

Forlani G, Trupia F. Measurement of δ1-Pyrroline-5-Carboxylic Acid in Plant Extracts for Physiological and Biochemical Studies. Metabolites. 2025; 15(12):777. https://doi.org/10.3390/metabo15120777

Chicago/Turabian StyleForlani, Giuseppe, and Flavia Trupia. 2025. "Measurement of δ1-Pyrroline-5-Carboxylic Acid in Plant Extracts for Physiological and Biochemical Studies" Metabolites 15, no. 12: 777. https://doi.org/10.3390/metabo15120777

APA StyleForlani, G., & Trupia, F. (2025). Measurement of δ1-Pyrroline-5-Carboxylic Acid in Plant Extracts for Physiological and Biochemical Studies. Metabolites, 15(12), 777. https://doi.org/10.3390/metabo15120777