Distinct Circulating Biomarker Profiles Associated with Type 2 Diabetes in a Regional Cohort—A Cross-Sectional Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Material and Methods

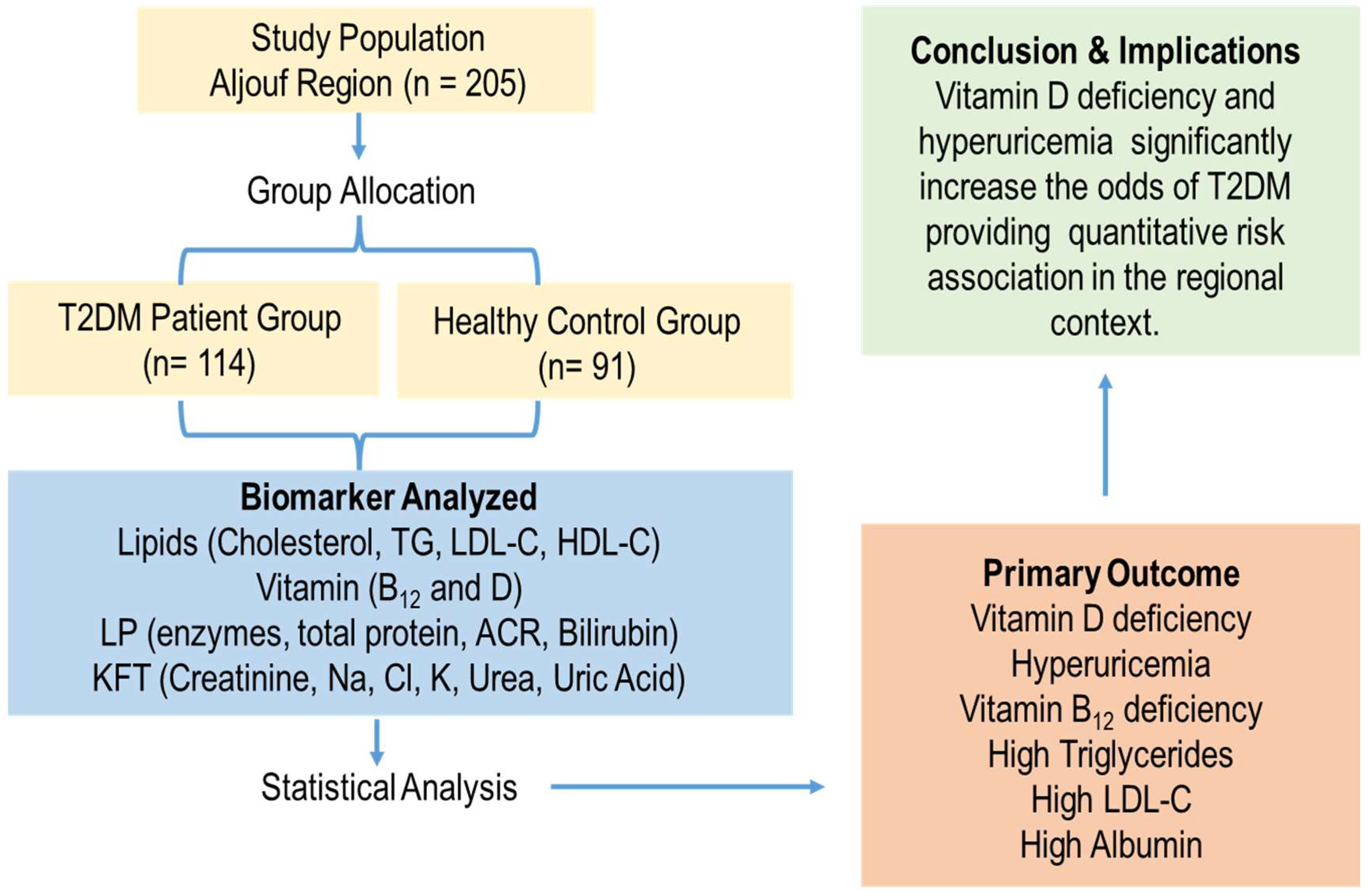

2.1. Study Population

2.2. Sociodemographic Data Collection

2.3. Blood Sampling and Laboratory Testing

2.4. Diabetes Diagnostic Criteria

2.5. Statistical Analyses

2.6. Ethical Approval

2.7. Patient Consent Statement

3. Results

3.1. Study Population Characteristics

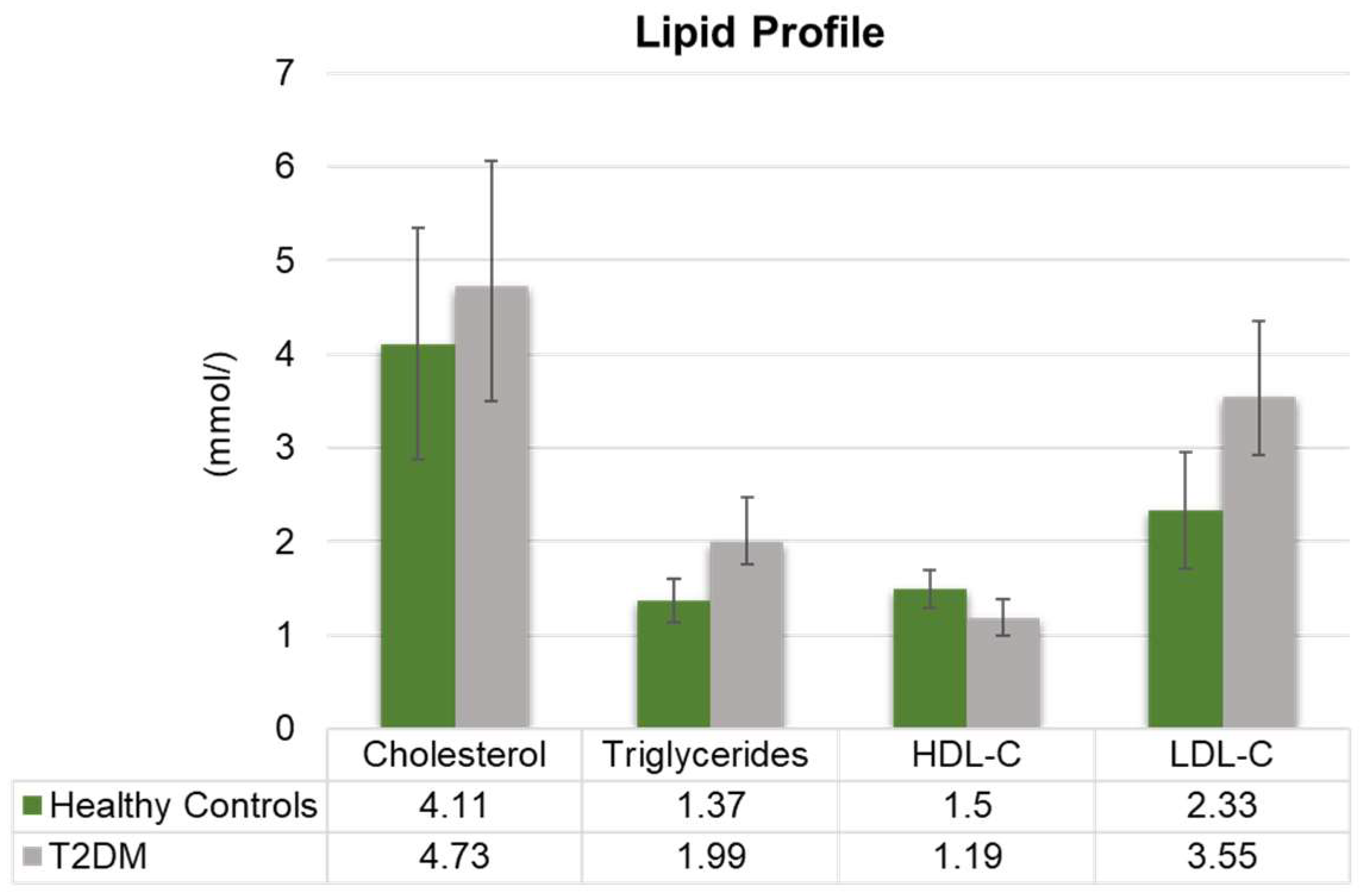

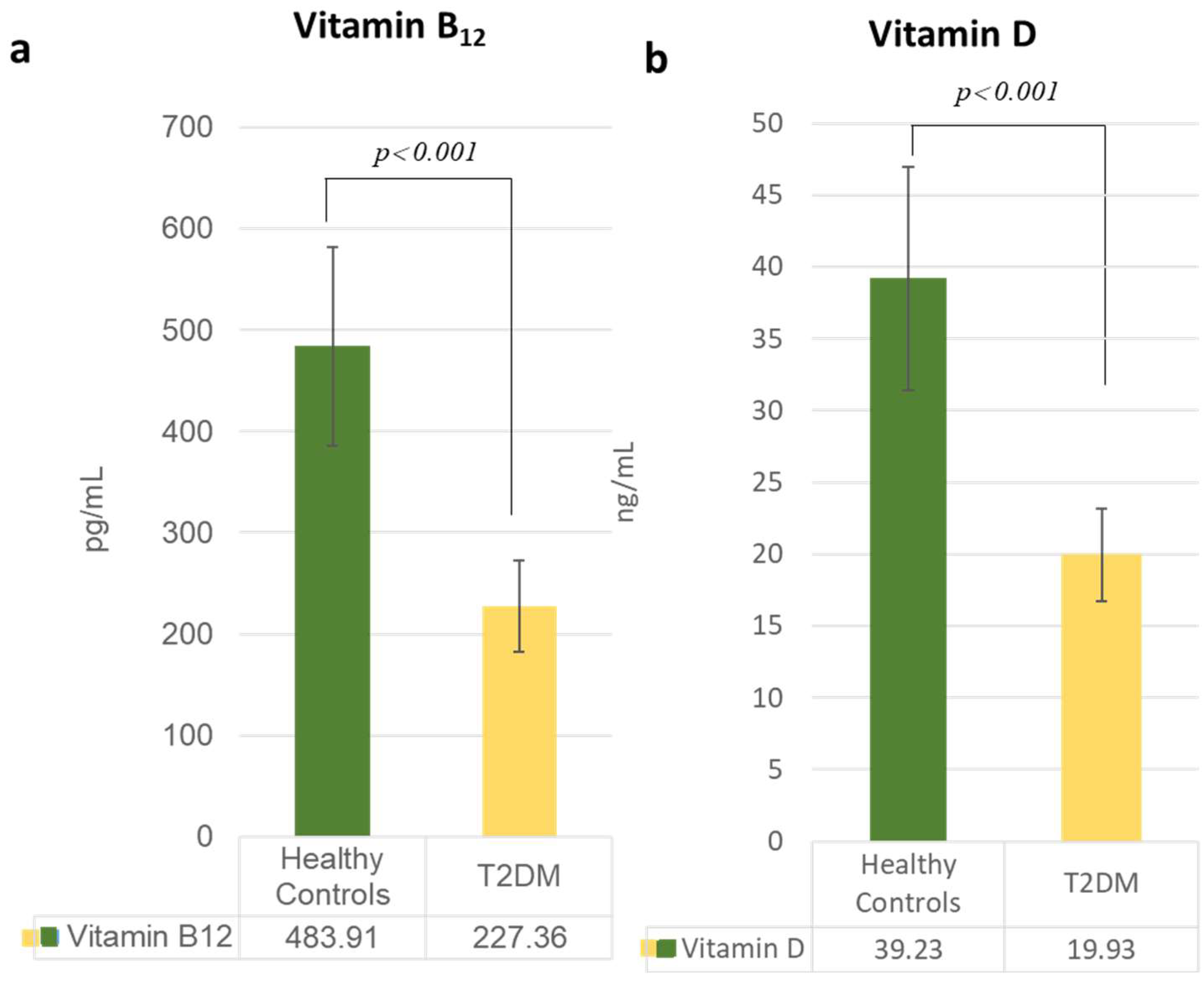

3.2. Alterations in Lipid and Vitamin Profiles

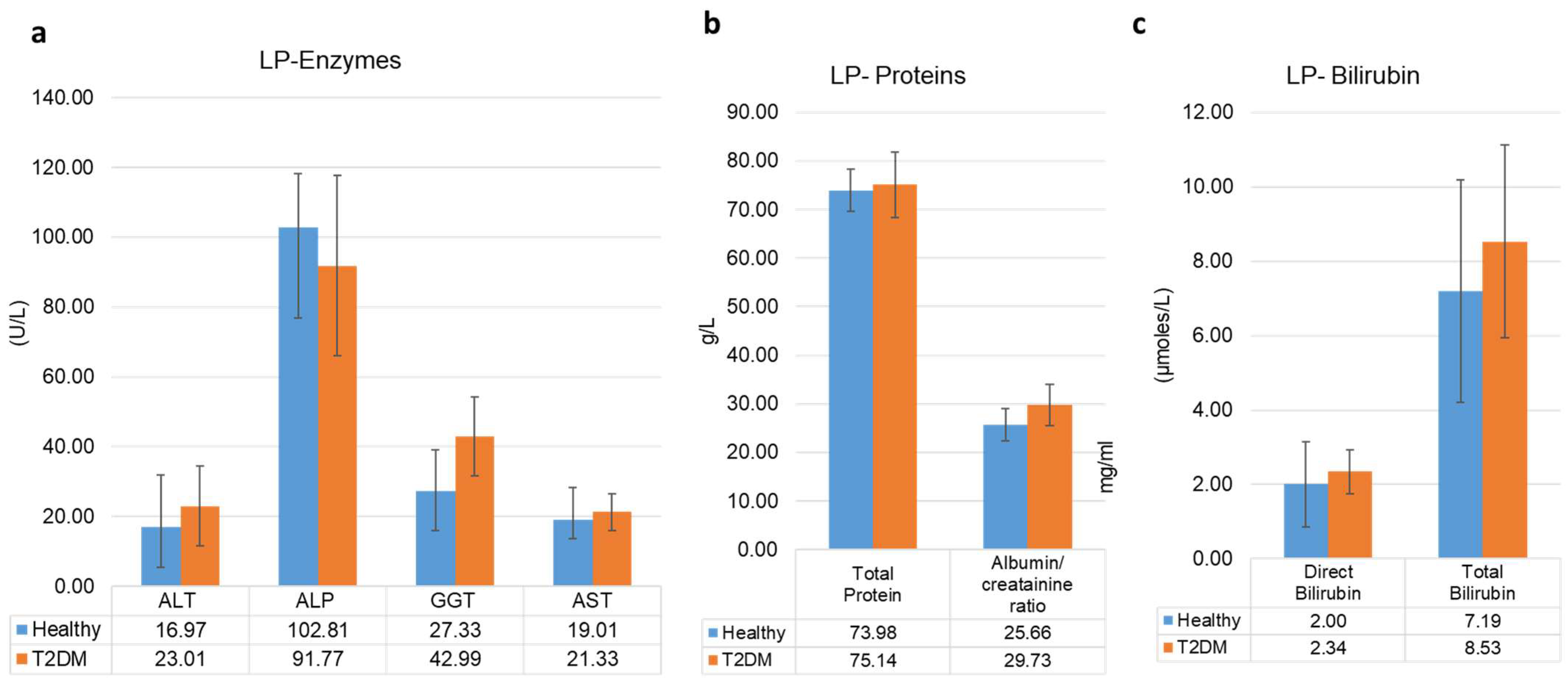

3.3. Liver Profile and Kidney Function Profiles

3.4. Multivariate Logistic Regression Analysis of Biomarker Associations with T2DM

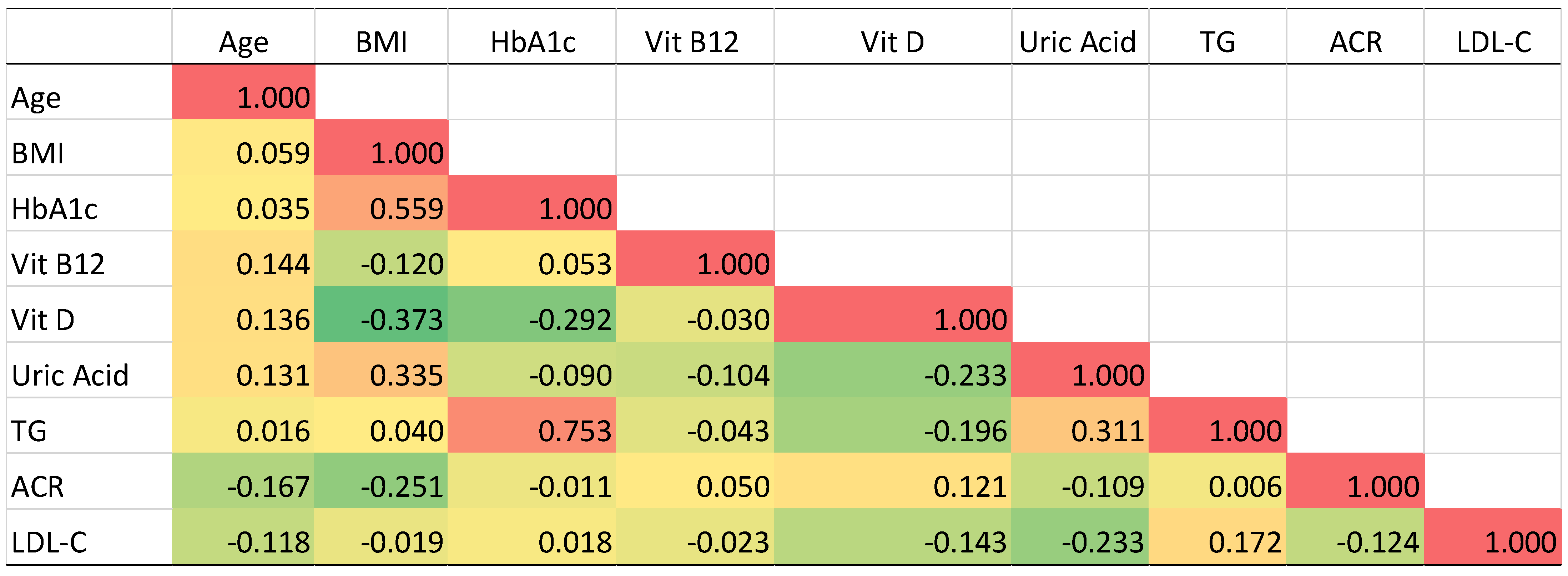

3.5. Pearson’s Correlation Analysis of T2DM Related Biomarkers

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Alwadeai, K.S.; Alhammad, S.A. Prevalence of type 2 diabetes mellitus and related factors among the general adult population in Saudi Arabia between 2016-2022: A systematic review and meta-analysis of the cross-sectional studies. Medicine 2023, 102, e34021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balooch Hasankhani, M.; Mirzaei, H.; Karamoozian, A. Global trend analysis of diabetes mellitus incidence, mortality, and mortality-to-incidence ratio from 1990 to 2019. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 21908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tomic, D.; Shaw, J.E.; Magliano, D.J. The burden and risks of emerging complications of diabetes mellitus. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2022, 18, 525–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bereda, G. Risk factors, complications and management of diabetes mellitus. Am. J. Biomed. Sci. Res. 2022, 16, 409–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Guo, C.; Wang, T.; Xu, Y.; Peng, F.; Zhao, S.; Li, H.; Jin, D.; Xia, Z.; Che, M.; et al. Interpretable machine learning-derived nomogram model for early detection of diabetic retinopathy in type 2 diabetes mellitus: A widely targeted metabolomics study. Nutr. Diabetes 2022, 12, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evangelatos, G.; Fragoulis, G.E. JAK inhibitors, cardiovascular and thromboembolic events: What we know and what we would like to know. Clin. Rheumatol. 2023, 42, 959–962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grewal, R.; Ortega, G.A.; Geng, F.; Srinivasan, S.; Rajabzadeh, A.R. Label-free electrochemical detection of glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c) and C-reactive protein (CRP) to predict the maturation of coronary heart disease due to diabetes. Bioelectrochemistry 2024, 159, 108743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Wang, Y.; Li, Y.; Hu, Y.; Jin, L.; Wang, W.; Gao, Z.; Tang, X.; Yan, L.; Wan, Q. High Normal urinary albumin–creatinine ratio is associated with hypertension, type 2 diabetes mellitus, HTN with T2DM, dyslipidemia, and cardiovascular diseases in the Chinese population: A report from the REACTION study. Front. Endocrinol. 2022, 13, 864562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sujana, C.; Salomaa, V.; Kee, F.; Costanzo, S.; Söderberg, S.; Jordan, J.; Jousilahti, P.; Neville, C.; Iacoviello, L.; Oskarsson, V. Natriuretic peptides and risk of type 2 diabetes: Results from the biomarkers for cardiovascular risk assessment in Europe (BiomarCaRE) consortium. Diabetes Care 2021, 44, 2527–2535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.; Wei, Y.; Liu, J.; Wang, Y.; Wang, G. Contributions of hepatic insulin resistance and islet β-Cell dysfunction to the blood glucose spectrum in newly diagnosed type 2 diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Metab. J. 2025, 49, 883–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, L.; Ran, X.; Liu, X.; Shen, X.; Chen, S.; Liu, F.; Zhao, D.; Bi, Y.; Su, Q.; Lu, Y.; et al. The effects of daily dose and treatment duration of metformin on the prevalence of vitamin B12 deficiency and peripheral neuropathy in Chinese patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: A multicenter cross-sectional study. J. Diabetes 2023, 15, 765–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renke, G.; Starling-Soares, B.; Baesso, T.; Petronio, R.; Aguiar, D.; Paes, R. Effects of vitamin D on cardiovascular risk and oxidative stress. Nutrients 2023, 15, 769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cosentino, N.; Campodonico, J.; Milazzo, V.; De Metrio, M.; Brambilla, M.; Camera, M.; Marenzi, G. Vitamin D and cardiovascular disease: Current evidence and future perspectives. Nutrients 2021, 13, 3603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dey, S.K.; Kumar, S.; Rani, D.; Maurya, S.K.; Banerjee, P.; Verma, M.; Senapati, S. Implications of vitamin D deficiency in systemic inflammation and cardiovascular health. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2024, 64, 10438–10455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Q.; Wu, Y.; Lu, Y.; Fei, X. Role of vitamin D in risk factors of patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Med. Clin. 2020, 154, 151–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farhana, A.; Khan, Y.S.; Alsrhani, A. Vitamin D at the intersection of health and disease: The immunomodulatory perspective. Int. J. Health Sci. 2024, 18, 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, Z.; Zhi, X.; Li, J.; Li, B.; Wang, J.; Zhu, J.; Zhang, Z. Effects of long-term vitamin D supplementation on metabolic profile in middle-aged and elderly patients with type 2 diabetes. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2023, 225, 106198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiou, S.J.; Chang, Y.J.; Chen, C.D.; Liao, K.; Tseng, T.S. Using Patient Profiles for Sustained Diabetes Management Among People With Type 2 Diabetes. Prev. Chronic. Dis. 2023, 20, E13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheehan, S.; Wicking, K.; Chapman, M.; Birks, M. Profiling risk factors of patients diagnosed with type 2 diabetes awaiting outpatient diabetes specialist consultant appointment, a narrative review. Collegian 2022, 29, 109–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.C.; Li, C.I.; Liu, C.S.; Lin, W.Y.; Lin, C.H.; Yang, S.Y.; Chiang, J.H.; Lin, C.C. Development and validation of prediction models for the risks of diabetes-related hospitalization and in-hospital mortality in patients with type 2 diabetes. Metabolism 2018, 85, 38–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zghebi, S.S.; Mamas, M.A.; Ashcroft, D.M.; Salisbury, C.; Mallen, C.D.; Chew-Graham, C.A.; Reeves, D.; Van Marwijk, H.; Qureshi, N.; Weng, S.; et al. Development and validation of the DIabetes Severity SCOre (DISSCO) in 139 626 individuals with type 2 diabetes: A retrospective cohort study. BMJ Open Diabetes Res. Care 2020, 8, e000962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dos Reis, R.C.P.; Duncan, B.B.; Szwarcwald, C.L.; Malta, D.C.; Schmidt, M.I. Control of glucose, blood pressure, and cholesterol among adults with diabetes: The Brazilian National Health Survey. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 3428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hernandez, P.; Passi, N.; Modarressi, T.; Kulkarni, V.; Soni, M.; Burke, F.; Bajaj, A.; Soffer, D. Clinical management of hypertriglyceridemia in the prevention of cardiovascular disease and pancreatitis. Curr. Atheroscler. Rep. 2021, 23, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reinstatler, L.; Qi, Y.P.; Williamson, R.S.; Garn, J.V.; Oakley, G.P., Jr. Association of biochemical B(1)(2) deficiency with metformin therapy and vitamin B(1)(2) supplements: The National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1999-2006. Diabetes Care 2012, 35, 327–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Infante, M.; Leoni, M.; Caprio, M.; Fabbri, A. Long-term metformin therapy and vitamin B12 deficiency: An association to bear in mind. World J. Diabetes 2021, 12, 916–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talmor, Y.; Bernheim, J.; Klein, O.; Green, J.; Rashid, G. Calcitriol blunts pro-atherosclerotic parameters through NFkappaB and p38 in vitro. Eur. J. Clin. Investig. 2008, 38, 548–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, P.; Huang, L.; Wang, Z.; Meng, X.; Yu, X. The association of serum uric acid with beta-cell function and insulin resistance in nondiabetic individuals: A cross-sectional study. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. Obes. 2021, 14, 2673–2682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martemucci, G.; Fracchiolla, G.; Muraglia, M.; Tardugno, R.; Dibenedetto, R.S.; D’Alessandro, A.G. Metabolic syndrome: A narrative review from the oxidative stress to the management of related diseases. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 2091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Truong, X.T.; Lee, D.H. Hepatic insulin resistance and steatosis in metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease: New insights into mechanisms and clinical implications. Diabetes Metab. J. 2025, 49, 964–986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alqahtani, S.A.M.; Awan, Z.A.; Alasmary, M.Y.; Al Amoudi, S.M. Association between serum uric acid with diabetes and other biochemical markers. J. Fam. Med. Prim. Care 2022, 11, 1401–1409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Wu, Y. Correlation of glucose and lipid metabolism levels and serum uric acid levels with diabetic retinopathy in type 2 diabetic mellitus patients. Emerg. Med. Int. 2022, 2022, 9201566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, X.; Xu, J. Association between serum uric acid-to-high-density lipoprotein cholesterol ratio and insulin resistance in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. J. Diabetes Investig. 2024, 15, 113–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martínez-Sánchez, F.D.; Vargas-Abonce, V.P.; Guerrero-Castillo, A.P.; De los Santos-Villavicencio, M.; Eseiza-Acevedo, J.; Meza-Arana, C.E.; Gulias-Herrero, A.; Gómez-Sámano, M.Á. Serum Uric Acid concentration is associated with insulin resistance and impaired insulin secretion in adults at risk for Type 2 Diabetes. Prim. Care Diabetes 2021, 15, 293–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, M.; Miao, X.; He, Y.; Liu, S.; Song, Z.; Xie, X.; Sun, Y.; Deng, J.; Wang, Q.; Leng, S. Associations between serum uric acid related ratios and the onset of metabolic dysfunction associated steatotic liver disease. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 22609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burger, K.; Trauner, M.M.; Bergheim, I. Pathogenic aspects of fructose consumption in metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD): A narrative review. Cell Stress 2025, 9, 49–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baharuddin, B. The Metabolic and Molecular Mechanisms Linking Fructose Consumption to Lipogenesis and Metabolic Disorders. Clin. Nutr. ESPEN 2025, 69, 63–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, S.A.; Dubourg, J.; Knott, M.; Colca, J. Hyperinsulinemia, an overlooked clue, and potential way forward in metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease. Hepatology 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deji-Oloruntoba, O.; Balogun, J.O.; Elufioye, T.; Ajakwe, S.O. Hyperuricemia and insulin resistance: Interplay and potential for targeted therapies. Int. J. Transl. Med. 2025, 5, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; He, Q.; Chen, Z.; Qin, J.-J.; Lei, F.; Liu, Y.-M.; Liu, W.; Chen, M.-M.; Sun, T.; Zhu, Q. A bidirectional relationship between hyperuricemia and metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease. Front. Endocrinol. 2022, 13, 821689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krajewska, M.; Witkowska-Sędek, E.; Rumińska, M.; Stelmaszczyk-Emmel, A.; Sobol, M.; Majcher, A.; Pyrżak, B. Vitamin D effects on selected anti-inflammatory and pro-inflammatory markers of obesity-related chronic inflammation. Front. Endocrinol. 2022, 13, 920340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karamanakos, G.; Kokkinos, A.; Dalamaga, M.; Liatis, S. Highlighting the role of obesity and insulin resistance in type 1 diabetes and its associated cardiometabolic complications. Curr. Obes. Rep. 2022, 11, 180–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruze, R.; Liu, T.; Zou, X.; Song, J.; Chen, Y.; Xu, R.; Yin, X.; Xu, Q. Obesity and type 2 diabetes mellitus: Connections in epidemiology, pathogenesis, and treatments. Front. Endocrinol. 2023, 14, 1161521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choe, H.J.; Almas, T.; Neeland, I.J.; Lim, S.; Després, J.-P. Obesity phenotypes and atherogenic dyslipidemias. Eur. J. Clin. Investig. 2025, e70151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Healthy Controls | T2DM | p-Values | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of participants | 91 | 114 | N/A |

| Age | 47.26 ± 12.11 | 49.27 ± 9.11 | 0.147 |

| Sex (M/F) | M (46); F (45) | M (51); F (58) | 0.478 |

| Nationality | Saudi | Saudi | N/A |

| Family History of Diabetes | Yes (10%); No (90%) | Yes (48%): No (52%) | <0.001 * |

| Family History of Thyroid Disease | No | No | N/A |

| Family History of Liver or Renal Disease | No | No | N/A |

| Blood Pressure Values Averages (Systolic) | 125.58 | 126.98 | 0.387 |

| Blood Pressure Values Averages (Diastolic) | 80.59 | 82.20 | 0.192 |

| Height (cm) | 161.79 ± 12.44 | 164.20 ± 9.01 | 0.118 |

| Weight (kg) | 81.00 ± 14.72 | 81.56 ± 16.01 | 0.966 |

| BMI | 29.84 ± 3.41 | 30.11 ± 4.52 | 0.667 |

| HbA1c (%) | 4.89 ± 0.71 | 7.62 ± 0.82 | <0.001 * |

| Medication | None (6 participants on occasional NSAID) | Insulin | N/A |

| Biochemical Parameters | Odds Ratio (OR) | 95% CI | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Increased Uric Acid | 3.39 | 1.33–8.62 | 0.010 |

| Low Vitamin D | 2.77 | 1.50–5.11 | 0.001 |

| Low Vitamin B12 | 2.26 | 1.38–3.70 | 0.001 |

| TG | 2.31 | 1.05–5.09 | 0.049 |

| LDL-C | 1.95 | 1.13–3.37 | 0.017 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Alsrhani, A.; Atif, M.; Farhana, A. Distinct Circulating Biomarker Profiles Associated with Type 2 Diabetes in a Regional Cohort—A Cross-Sectional Study. Metabolites 2025, 15, 776. https://doi.org/10.3390/metabo15120776

Alsrhani A, Atif M, Farhana A. Distinct Circulating Biomarker Profiles Associated with Type 2 Diabetes in a Regional Cohort—A Cross-Sectional Study. Metabolites. 2025; 15(12):776. https://doi.org/10.3390/metabo15120776

Chicago/Turabian StyleAlsrhani, Abdullah, Muhammad Atif, and Aisha Farhana. 2025. "Distinct Circulating Biomarker Profiles Associated with Type 2 Diabetes in a Regional Cohort—A Cross-Sectional Study" Metabolites 15, no. 12: 776. https://doi.org/10.3390/metabo15120776

APA StyleAlsrhani, A., Atif, M., & Farhana, A. (2025). Distinct Circulating Biomarker Profiles Associated with Type 2 Diabetes in a Regional Cohort—A Cross-Sectional Study. Metabolites, 15(12), 776. https://doi.org/10.3390/metabo15120776