The Cellular Stability Hypothesis: Evidence of Ferroptosis and Accelerated Aging-Associated Diseases as Newly Identified Nutritional Pentadecanoic Acid (C15:0) Deficiency Syndrome

Abstract

1. Introduction

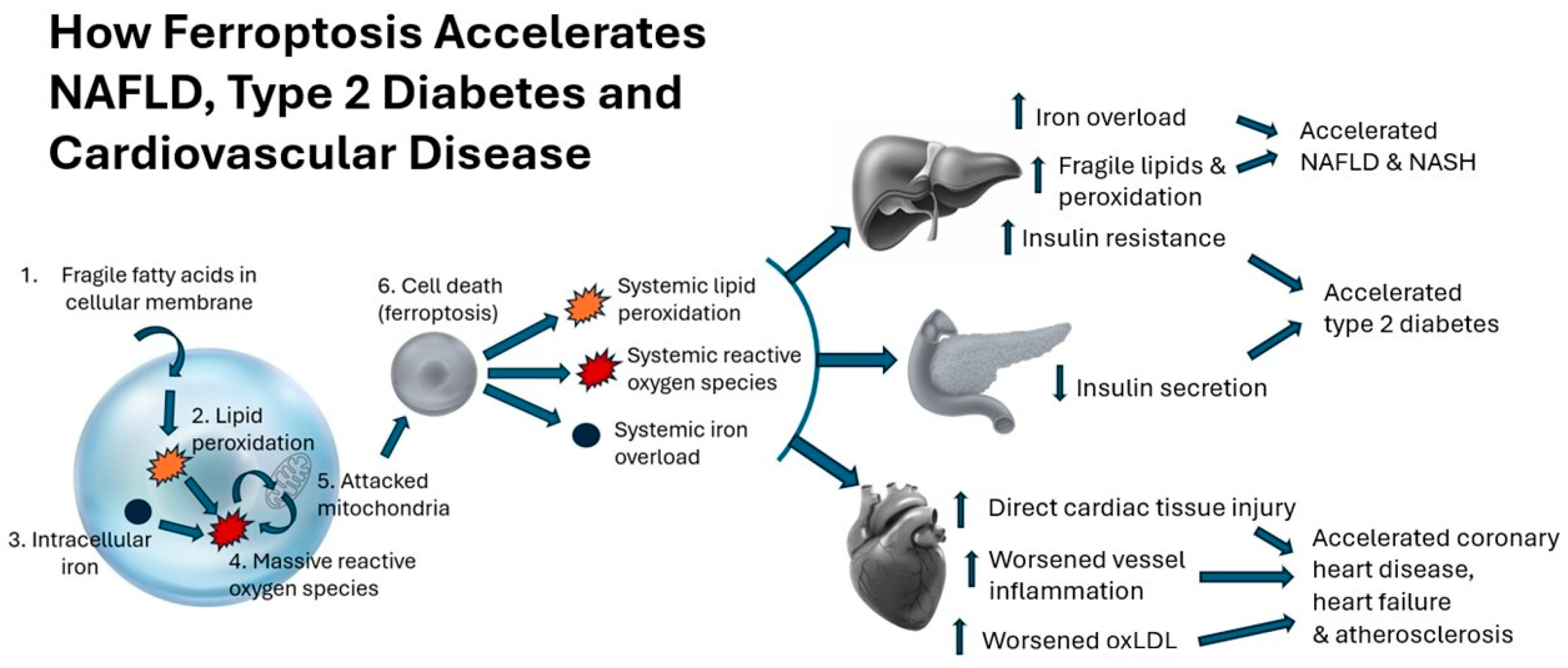

2. Relevance of Ferroptosis to Rising Metabolic and Related Diseases

2.1. Core Features of Ferroptosis: Lipid Peroxidation and Iron Overload

2.2. Type 2 Diabetes

2.3. Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease

2.4. Cardiovascular Disease

2.5. Neurodegenerative Disease

2.6. Therapeutic Approaches to Ferroptosis

3. Essentiality of C15:0, Evidence of Nutritional Deficiencies, and Relevance to Metabolic and Related Diseases

3.1. Evidence of Essentiality

- Dietary C15:0 intake is directly and reliably correlated to circulating C15:0 concentrations, demonstrating that C15:0 is primarily exogenous [49].

3.2. Evidence of Nutritional C15:0 Deficiencies

3.2.1. Normal C15:0 Concentrations in Humans

3.2.2. Associations between Lower C15:0 Concentrations and Increased Risk of Type 2 Diabetes, Cardiovascular Disease, and NAFLD

3.2.3. Importance of Normal C15:0 Concentrations to Support Healthy Pregnancies and Early Child Development

3.2.4. Drivers for Declining C15:0 Concentrations

4. Metabolic Diseases and Iron Overload in Dolphins: Insights on an Emerging C15:0 Nutritional Deficiency Syndrome

4.1. Physiologic Similarities between Dolphins and Humans

4.2. Fatty Liver Disease, Iron Overload, and Metabolic Syndrome in Dolphins: Dysmetabolic Iron Overload Syndrome

4.3. Dysmetabolic Iron Overload Syndrome in Humans

4.4. Lower Dietary and Circulating C15:0 Are Associated with DIOS in Dolphins

4.5. An Unexpected Clue: Increased Dietary C15:0 Alleviates Anemia in Dolphins

4.6. C15:0 Attenuation of Anemia, DIOS, NASH, and Metabolic Syndrome in a Relevant Model

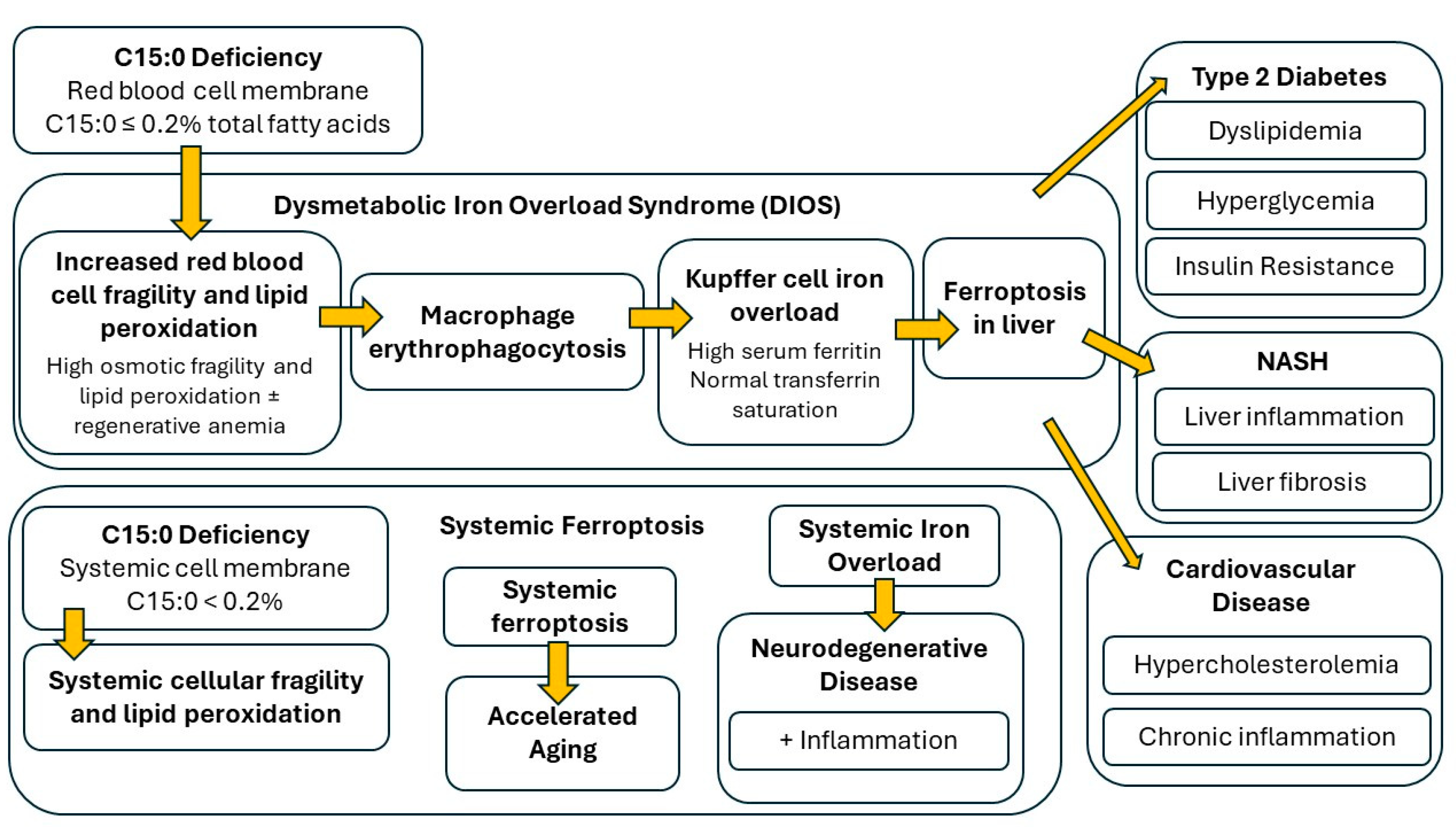

5. Proposed Nutritional-C15:0-Deficiency-Driven Cellular Fragility Syndrome

5.1. Proposed Nutritional C15:0 Deficiency Definition

- C15:0 deficiency, defined as ≤0.2% of total circulating fatty acids, results in Cellular Fragility Syndrome, which includes higher risks of developing DIOS, ferroptosis, anemia, advanced NAFLD and NASH, cardiovascular disease, and type 2 diabetes. In addition to low C15:0 concentrations and indices associated with liver and cardiometabolic diseases, people with Cellular Fragility Syndrome are expected to have (1) hyperferritinemia, (2) elevated lipid peroxidation levels, (3) red blood cells with elevated osmotic fragility, and (4) elevated red blood cell distribution width (RDW) [3,4,5,6,47,140,142].

5.2. Proposed Pathophysiology of Nutritional C15:0 Deficiencies (Cellular Fragility Syndrome)

- First, red blood cell membranes containing C15:0 ≤ 0.2% total fatty acids become fragile and susceptible to lipid peroxidation. In addition to C15:0 measurements, tests to detect this stage may include osmotic fragility tests, RDW, and systemic lipid peroxidation.

- Second, fragile red blood cells are engulfed by macrophages, including liver Kupffer cells, which over time results in regenerative anemia and DIOS. Tests that may detect this stage include low hemoglobin, high reticulocytes, high RDW, and hyperferritinemia.

- Third, combined elevated lipid peroxidation with iron overload results in ferroptosis in the liver and the subsequent advancement of NAFLD and NASH, including increased inflammation, cell damage, and fibrosis in the liver. Tests that may detect this stage include elevated liver enzymes and increased inflammatory markers (elevated globulins, IL-6, TNFα, and MCP-1).

- Fourth, impaired liver function and ferroptosis results in insulin resistance, metabolic syndrome, type 2 diabetes, and cardiovascular disease. Tests to detect this stage include non-specific markers of these diseases, including elevated insulin, glucose, cholesterol, and triglycerides.

- Finally, spillover iron and systemically fragile cell membranes result in systemic iron overload and ferroptosis, which pairs with fragile cells to further impair tissues, resulting in accelerated aging, including accelerated cardiovascular disease.

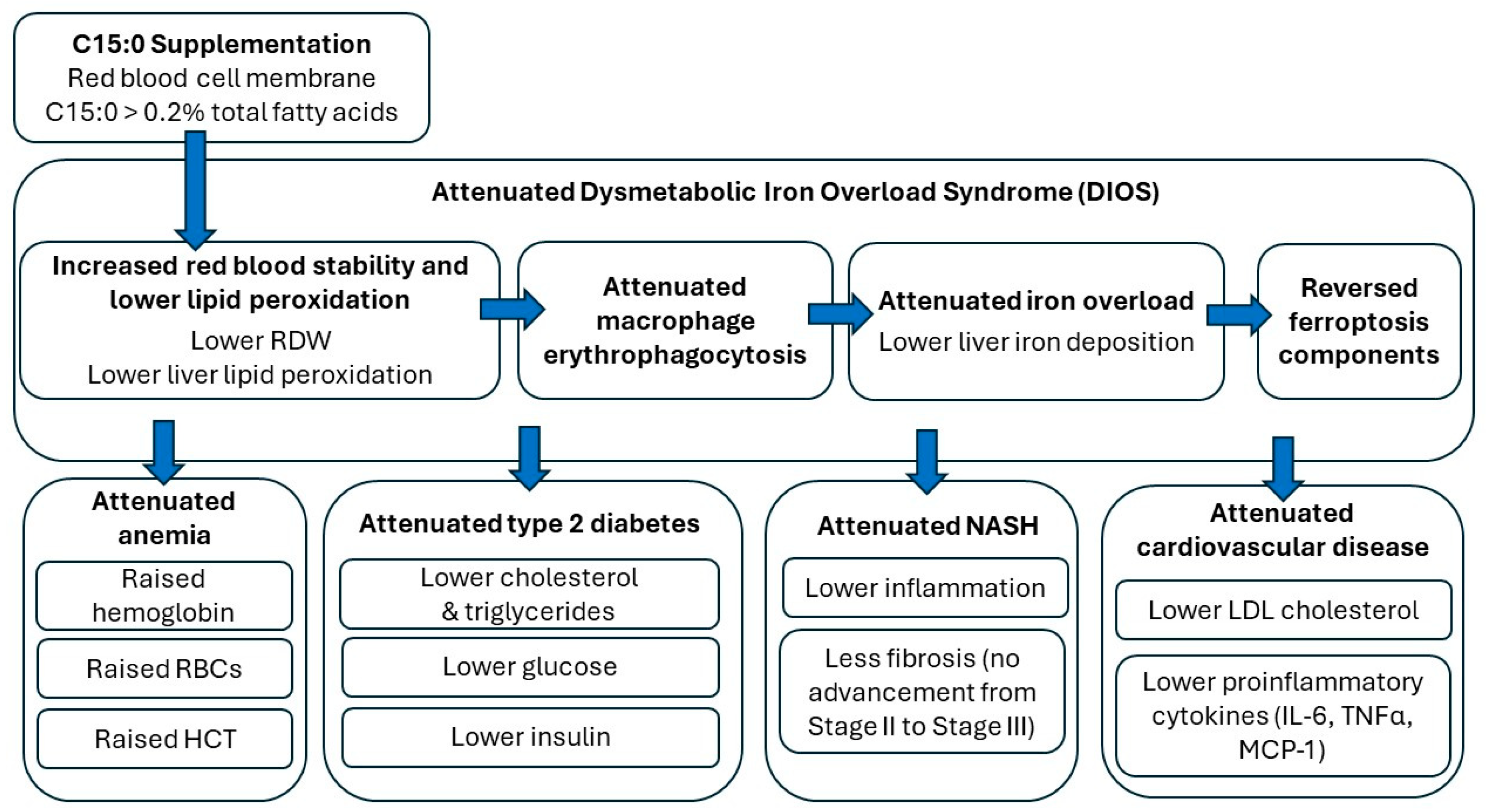

6. Demonstrated In Vivo Efficacies of Oral C15:0 Supplementation to Reverse Cellular Fragility Syndrome

6.1. C15:0 Supplementation Stabilizes Red Blood Cells, Attenuates Anemia, and Lowers Lipid Peroxidation

6.2. C15:0 Supplementation Decreases Erythrophagocytosis by Liver Kupffer Cells, Resulting in Attenuated DIOS, NAFLD, and NASH

6.3. C15:0 Supplementation Lowered Indices of Insulin Resistance, Metabolic Syndrome, Type 2 Diabetes, and Cardiovascular Disease

7. Conclusions

8. Patents

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hulbert, A.J. On the importance of fatty acid composition of membranes for aging. J. Theor. Biol. 2005, 234, 277–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dixon, S.J.; Lemberg, K.M.; Lamprecht, M.R.; Skouta, R.; Zaitsev, E.M.; Gleason, C.E.; Patel, D.N.; Bauer, A.J.; Cantley, A.M.; Yang, W.S.; et al. Ferroptosis: An iron-dependent form of nonapoptotic cell death. Cell 2012, 149, 1060–1072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, R.; Fang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Wei, J.; Zhang, Y.; Tian, J. Iron metabolism and ferroptosis in type 2 diabetes mellitus and complications: Mechanisms and therapeutic opportunities. Cell Death Dis. 2023, 14, 186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, H.; Zhang, E.; Hu, H. Role of ferroptosis in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and its implications for therapeutic strategies. Biomedicines 2021, 9, 1660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pasini, A.M.F.; Stranieri, C.; Busti, F.; Di Leo, E.G.; Girelli, D.; Cominacini, L. New insights into the role of ferroptosis in cardiovascular disease. Cells 2023, 12, 867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Zhou, L.; Qiao, H.; Xu, Q.; Liu, Y. The role of ferroptosis in neurodegenerative diseases. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2023, 50, 1655–1661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tonnies, T.; Brinks, R.; Isom, S.; Dabelea, D.; Divers, J.; Mayer-Davis, E.J.; Lawrence, J.M.; Pihoker, C.; Dolan, L.; Liese, A.D.; et al. Projections of type 2 and type 2 diabetes burden in the U.S. population aged < 20 years through 2060: The SEARCH for diabetes in youth study. Diabetes Care 2023, 46, 313–320. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lee, Y.T.H.; Fang, J.; Schieb, L.; Park, S.; Casper, M.; Gillespie, C. Prevalence and trends of coronary heart disease in the United States, 2011 to 2018. JAMA Cardiol. 2022, 7, 459–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koh, B.; Tan, D.J.H.; Ng, C.H.; Fu, C.E.; Lim, W.H.; Zeng, R.W.; Yong, J.N.; Koh, J.H.; Syn, N.; Meng, W.; et al. Patterns in cancer incidence among people younger than 50 years in the U.S., 2010 to 2019. JAMA Netw. Open 2023, 6, e2328171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ludwig, J.; Viggiano, T.R.; McGill, D.B.; Oh, B.J. Nonalcoholic steatohepatitis: Mayo Clinic experiences with a hitherto unnamed disease. Mayo Clin. Proc. 1980, 55, 434–438. [Google Scholar]

- Younossi, Z.M.; Koenig, A.B.; Abdelatif, D.; Fazel, Y.; Henry, L.; Wymer, M. Global epidemiology of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) and nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH): A systematic review. Hepatology 2023, 77, 1335–1347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pope, L.E.; Dixon, S.J. Regulation of ferroptosis by lipid metabolism. Trends Cell Biol. 2023, 33, 1077–1087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, X.; Yu, C.; Kang, R.; Tang, D. Iron metabolism in ferroptosis. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2020, 8, 590226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mortensen, M.S.; Ruiz, J.; Watts, J.L. Polyunsaturated fatty acids drive lipid peroxidation during ferroptosis. Cells 2023, 12, 804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Masenga, S.K.; Kabwe, L.S.; Chackulya, M.; Kirabo, A. Mechanisms of oxidative stress in metabolic syndrome. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 7898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martin-Fernandez, M.; Arroyo, V.; Carnicero, C.; Siguenza, R.; Busta, R.; Mora, N.; Antolin, B.; Tamayo, E.; Aspichueta, P.; Carnicero-Frutos, I.; et al. Role of oxidative stress and lipid peroxidation in the pathophysiology of NAFLD. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 2217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gianazza, E.; Brioschi, M.; Fernandez, A.M.; Casalnuovo, F.; Altomare, A.; Aldini, G.; Banfi, C. Lipid peroxidation in atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2020, 34, 49–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Butterfield, D.A. Brain lipid peroxidation and Alzheimer disease: Synergy between the Butterfield and Mattson laboratories. Ageing Res. Rev. 2020, 64, 101049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, A.V.; Lorenzo, F.R.; McClain, D.A. Iron and the pathophysiology of diabetes. Ann. Rev. Physiol. 2023, 85, 339–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elthes, Z.Z.; Szabo, M.I.M. Iron metabolism and metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease. Acta Marisienses–Ser. Med. 2023, 69, 182–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawicki, K.T.; De Jesus, A.; Ardehali, H. Iron metabolism in cardiovascular disease: Physiology, mechanisms, and therapeutic targets. Circ. Res. 2023, 132, 379–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, S.; Kovacs, G.G. The irony of iron: The element with diverse influence on neurodegenerative diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 4269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- GBD 2021 Diabetes Collaborators. Global, regional, and national burden of diabetes from 1990 to 2021, with projections of prevalence to 2050: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. Lancet 2023, 402, 203–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perng, W.; Conway, R.; Mayer-Davis, E.; Dabelea, D. Youth-onset type 2 diabetes: The epidemiology of an awakening epidemic. Diabetes Care 2023, 46, 490–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Wang, H. Oxidative stress in pancreatic beta cell regeneration. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2017, 2017, 1930261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Wang, Y.; Jiang, R.; Xue, R.; Yin, X.; Wu, M.; Meng, Q. Ferroptosis in liver disease: New insights in to disease mechanisms. Cell Death Discov. 2021, 7, 276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ajmera, V.; Cepin, S.; Tesfai, K.; Hofflich, H.; Cadman, K.; Lopez, S.; Madamba, E.; Bettencourt, R.; Richards, L.; Behling, C.; et al. A prospective study on the prevalence of NAFLD, advanced fibrosis, cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma in people with type 2 diabetes. J. Hepatol. 2023, 78, 471–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosengren, A.; Dikaiou, P. Cardiovascular outcomes in type 1 and type 2 diabetes. Diabetologia 2023, 66, 425–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Song, M.; Cao, Y.; Eliassen, A.H.; Wolpin, B.M.; Stampfer, M.J.; Willett, W.C.; Wu, K.; Ng, K.; Hu, F.B.; et al. Incident early- and later-onset type 2 diabetes and risk of early- and later-onset cancer: Prospective cohort study. Diabetes Care 2023, 46, 120–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marrano, N.; Biondi, G.; Borrelli, A.; Rella, M.; Zambetta, T.; Di Giola, L.; Caporussa, M.; Logroscino, G.; Perrini, S.; Giorgino, F.; et al. Type 2 diabetes and Alzheimer’s disease: The emerging role of cellular lipotoxicity. Biomolecules 2023, 13, 183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Wang, H.; Zhang, X.J.; Cai, J.; Li, H. NAFLD: An emerging causal factor for cardiovascular disease. Physiology 2023, 38, 255–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muhamad, N.A.; Maamor, N.H.; Leman, F.N.; Mohamad, Z.A.; Bakon, S.K.; Mutalip, M.H.A.; Rosli, I.A.; Aris, T.; Lai, N.M.; Hassan, M.R.A. The global prevalence of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and its association with cancers: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Interact. J. Med. Res. 2023, 12, e40653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chan, W.K.; Chuah, K.H.; Rajaram, R.B.; Lim, L.L.; Ratnasingam, J.; Vethakkan, S.R. Metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD): A state-of-the-art review. J. Obes. Metab. Syndr. 2023, 32, 197–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hangstrom, H.; Vessby, J.; Ekstedt, M.; Shang, Y. 99% of patients with NAFLD meet MASLD criteria and natural history is therefore identical. J. Hepatol. 2024, 80, E76–E77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qi, J.; Kim, J.W.; Zhou, Z.; Lim, C.W.; Kim, B. Ferroptosis affects the progression of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis via the modulation of lipid peroxidation-mediated cell death in mice. Am. J. Pathol. 2020, 190, 68–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmad, F.B.; Anderson, R.N. The leading causes of death in the US for 2020. JAMA 2021, 325, 1829–1830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Xu, X.D.; Ma, M.Q.; Liang, Y.; Cai, Y.B.; Zhu, Z.X.; Xu, T.; Zhu, L.; Ren, K. The mechanisms of ferroptosis and its role in atherosclerosis. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2024, 171, 116112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Li, X.; Wang, S.; Miao, R.; Zhong, J. Targeting iron metabolism and ferroptosis as novel therapeutic approaches in cardiovascular diseases. Nutrients 2023, 15, 591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villalon-Garcia, I.; Povea-Cabello, S.; Avarez-Cordoba, M.; Talaveron-Rey, M.; Suarez-Rivero, J.M.; Suarez-Carrillo, A.; Munuera-Cabeza, M.; Reche-Lopez, D.; Cilleros-Holgado, P.; Pinero-Perez, R.; et al. Vicious cycle of lipid peroxidation and iron accumulation in neurodegeneration. Neural Regen. Res. 2023, 18, 1196–1202. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan, S.K.; Ugalde, C.L.; Roland, A.S.; Skidmore, J.; Devos, D.; Hammond, T.R. Therapeutic inhibition of ferroptosis in neurodegenerative disease. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2023, 44, 674–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, S.; Shen, J.; Jiang, J.; Wang, F.; Min, J. Targeting ferroptosis opens new avenues for the development of novel therapeutics. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2023, 8, 372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingold, I.; Berndt, C.; Schmitt, S.; Doll, S.; Poschmann, G.; Buday, K.; Roveri, A.; Peng, X.; Freitas, F.P.; Seibt, T.; et al. Selenium utilization by GPX4 is required to prevent hydroperoxide-induced ferroptosis. Cell 2018, 172, 409–422.e21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.; Lin, J.S.; Aris, I.M.; Yang, G.; Chen, W.Q.; Li, L.J. Circulating saturated fatty acids and incident type 2 diabetes: A systemic review and meta-analysis. Nutrients 2019, 11, 998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imamura, F.; Fretts, A.; Marklund, M.; Korat, A.V.A.; Yang, W.S.; Lankinen, M.; Qureshi, W.; Helmer, C.; Chen, T.A.; Wong, K.; et al. Fatty acid biomarkers of dairy fat consumption and incidence of type 2 diabetes: A pooled analysis of prospective cohort studies. PLoS Med. 2018, 15, e1002670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, J.S.; Sharp, S.J.; Imamura, F.; Koulman, A.; Schulze, M.B.; Ye, Z.; Griffin, J.; Guevara, M.; Huerta, J.M.; Kroger, J.; et al. Association between plasma phospholipid saturated fatty acids and metabolic markers of lipid, hepatic, inflammation, and glycaemic pathways in eight European countries: A cross-sectional analysis in the EPIC-InterAct study. BMC Med. 2017, 15, 203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmon, R. Essential fatty acids. Nutr. Rev. 1958, 16, 33–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venn-Watson, S.; Lumpkin, R.; Dennis, E.A. Efficacy of dietary odd-chain saturated fatty acid pentadecanoic acid parallels broad associated health benefits: Could it be essential? Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 8161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dornan, K.; Gunenc, A.; Oomah, D.; Hosseinian, F. Odd chain fatty acids and odd chain phenolipic lipids (alkylresorcinols) are essential for diet. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2021, 98, 813–824. [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins, B.J.; Seyssel, K.; Chiu, S.; Pan, P.H.; Lin, S.Y.; Stanley, E.; Ament, Z.; West, J.A.; Summerhill, K.; Griffin, J.L.; et al. Odd chain fatty acids; new insights of the relationship between the gut microbiota, dietary intake, biosynthesis and glucose intolerance. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 44845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, W.; Wong, C.C.; Jia, Z.; Liu, W.; Liu, C.; Ji, F.; Pan, Y.; Wang, F.; Wang, G.; Zhao, L.; et al. Parabacteroides distasonis uses dietary inulin to suppress NASH via its metabolite pentadecanoic acid. Nat. Microbiol. 2023, 8, 1534–1548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chooi, Y.C.; Zhang, Q.A.; Magkos, F.; Ng, M.; Michael, N.; Wu, X.; Volchanskaya, V.S.B.; Lai, X.; Wanjaya, E.R.; Elejalde, U.; et al. Effect of an Asian-adapted Mediterranean diet and pentadecanoic acid on fatty liver disease: The TANGO randomized controlled trial. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2024, 119, 788–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, W.C.; Li, H.Y.; Li, T.T.; Yang, K.; Chen, J.X.; Want, S.J.; Liu, C.H.; Zhang, W. Pentadecanoic acid promotes basal and insulin-stimulated glucose update in C2C12 myotubes. Food Nutr. Res. 2021, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albani, V.; Celis-Morales, C.; Marsaux, C.F.M.; Forster, H.; O’Donovan, C.B.; Woolhead, C.; Macready, A.; Fallaize, R.; Navas-Carretero, S.; San-Cristobal, R.; et al. Exploring the association of dairy product intake with the fatty acids C15:0 and C17:0 measured from dried blood spots in a multi-population cohort: Findings from the Food4Me study. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2016, 60, 834–845. [Google Scholar]

- Slim, M.; Ha, C.; Vanstone, C.A.; Morin, S.N.; Rahme, E.; Weiler, H.A. Evaluation of plasma and erythrocyte fatty acids C15:0, t-C16:1n-7 and C17:0 as biomarkers of dairy fat consumption in adolescents. Prostaglandins Leukot. Essent. Fat. Acids 2019, 149, 24–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poppitt, S.D.; Kilmartin, P.; Butler, P.; Keogh, G.F. Assessment of erythrocyte phospholipid fatty acid composition as a biomarker for dietary MUFA, PUFA or saturated fatty acid intake in a controlled cross-over intervention trial. Lipids Health Dis. 2005, 4, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matorras, R.; Ruiz, J.I.; Mendoza, R.R.; Ruiz, N.; Sanjurjo, P.; Rodriquez-Escudero, F.J. Fatty acid composition of fertilization-failed human oocytes. Hum. Reprod. 1998, 13, 2227–2230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Kingsbury, K.J.; Heyes, T.D.; Morgan, M.; Aylott, C.; Burton, P.A.; Emmerson, R.; Robinson, P.J.A. The effect of dietary changes on the fatty acid composition of normal human depot fat. Biochem. J. 1962, 84, 124–133. [Google Scholar]

- Manca, C.; Carta, G.; Murru, E.; Abolghasemi, A.; Ansar, H.; Errigo, A.; Cani, P.D.; Banni, S.; Pes, G.M. Circulating fatty acids and endocannabinoidome-related mediator profiles associated to human longevity. GeroScience 2021, 43, 1783–1798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.; Li, Y.; Zeng, F.; Deng, G.; Liang, J.; Wang, J.; Su, Y.; Chen, Y.; Mao, L.; Liu, Z.; et al. Biomarkers of fatty acids and risk of type 2 diabetes: A systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2020, 61, 2705–2718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahadoran, Z.; Mirmiran, P. Usual intake of dairy products and the chance of pre-diabetes regression to normal glycemia or progression to type 2 diabetes: A 9-year follow-up. Nutr. Diabetes 2024, 14, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Lei, H.; Jiang, H.; Fan, Y.; Shi, J.; Li, C.; Chen, F.; Mi, B.; Ma, M.; Lin, J.; et al. Saturated fatty acid biomarkers and risk of cardiometabolic diseases: A meta-analysis of prospective studies. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 963471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maruyama, C.; Yoneyama, M.; Suyama, N.; Kasuya, Y.; Teramoto, A.; Sakaki, Y.; Suto, Y.; Takahashi, K.; Araki, R.; Ishizaka, Y.; et al. Differences in serum phospholipid fatty acid compositions and estimated desaturase activities between Japanese men with and without metabolic syndrome. J. Atheroscler. Thromb. 2008, 15, 306–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; Li, S.; Luo, J.; Wang, W.; Lu, W.; He, Y.; Xu, X. Serum levels of pentadecanoic acid and heptadecanoic acid negatively correlate with kidney stone prevalence: Evidence from NHANES 2011–2014. Res. Sq. 2024; preprint. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Mello, V.D.; Selander, T.; Lindstrom, J.; Tuomilehto, J.; Uusitupa, M.; Kaarniranta, K. Serum levels of plasmalogens and fatty acid metabolites associate with retinal microangiopathy in participants from the Finnish Diabetes Prevention Study. Nutrients 2021, 13, 4452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, J.; Yu, H.; Li, K.; Ding, B.; Xiao, R.; Ma, W. The association between plasma fatty acid and cognitive function mediated by inflammation in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. Obes. 2022, 15, 1423–1436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trieu, K.; Bhat, S.; Dai, Z.; Leander, K.; Gigante, B.; Qian, F. Biomarkers of dairy fat intake, incident cardiovascular disease, and all-cause mortality: A cohort study, systematic review, and meta-analysis. PLoS Med. 2021, 18, e1003763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biong, A.S.; Veierod, M.B.; Ringstad, J.; Thelle, D.S.; Pedersen, J.I. Intake of milk fat, reflected in adipose tissue fatty acids and risk of myocardial infarction: A case-control study. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2006, 60, 236–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warsenjo, E.; Jansson, J.H.; Berglund, L.; Boma, K.; Ahren, B.; Weinehail, L.; Lindahl, B.; Hallmans, G.; Vessby, B. Estimated intake of milk fat is negatively associated with cardiovascular risk factors and does not increase the risk of acute myocardial infarction. A prospective case-control study. Br. J. Nutr. 2004, 91, 635–642. [Google Scholar]

- Djousse, L.; Biggs, M.L.; Matthan, N.R.; Ix, J.H.; Fitzpatrick, A.L.; King, I.; Lamaitre, R.N.; McKnight, B.; Kizer, J.R.; Lichtenstein, A.H.; et al. Serum individual nonesterifies fatty acids and risk of heart failure in older adults. Cardiology 2021, 46, 351–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, J.; Zhou, Q.; Amakye, W.K.; Su, Y. Biomarkers of dairy fat intake and risk of cardiovascular disease: A systemic review and meta-analysis of prospective studies. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2018, 58, 1122–1130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Sun, Y.; Yang, P.; Wang, X.; Zhang, X.; Hu, P.; Jiang, T.; Xu, Z. Untargeted metabolomics analysis of differences in metabolite levels in congenital heart disease of varying severity. Res. Sq. 2023; preprint. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maciejewska, D.; Palma, J.; Dec, K.; Skonieczna-Zydecka, K.; Gutowska, I.; Szcuko, M.; Jakubczyk, K.; Stachowska, E. Is the fatty acids profile in blood a good predictor of liver changes? Correlation of fatty acids profile with fatty acids content in the liver. Diagnostics 2019, 9, 197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kratz, M.; Marcovina, S.; Nelson, J.E.; Yeh, M.M.; Kowdley, K.V.; Callahan, H.S.; Song, X.; Di, C.; Utzschneider, K.M. Dairy fat intake is associated with glucose tolerance, hepatic and systemic insulin sensitivity, and liver fat, but not β-cell function in humans. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2014, 99, 1385–1396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawh, M.C.; Wallace, M.; Shapiro, E.; Goyal, N.P.; Newton, K.P.; Yu, E.L.; Bross, C.; Durelle, J.; Knott, C.; Gangoiti, J.A.; et al. Dairy fat intake, plasma C15:0 and plasma iso-C17:0 are inversely associated with liver fat in children. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 2021, 72, 90–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fidler, N.; Koletzko, B. The fatty acid composition of human colostrum. Eur. J. Nutr. 2000, 39, 31–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fidler, N.; Salobir, K.; Stibilj, V. Fatty acid composition of human milk in different regions of Slovenia. Ann. Nutr. Metab. 2000, 44, 187–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- USDA FoodData Central. Available online: https://fdc.nal.usda.gov/fdc-app.html#/?component=1299 (accessed on 21 March 2024).

- Yuhas, R.; Pramuk, K.; Lien, E.L. Human milk fatty acid composition from nine countries varies most in DHA. Lipids 2006, 41, 851–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, T.C.; Lau, B.H.; Chen, P.H.; Wu, L.T.; Tang, R.B. Fatty acid composition of Taiwanese human milk. J. Chin. Med. Assoc. 2010, 73, 581–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carta, S.; Correddu, F.; Battacone, G.; Pulina, G.; Nudda, A. Comparison of milk odd- and branched-chain fatty acids among human, dairy species and artificial substitutes. Foods 2022, 11, 4118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Tsai, M.Y.; Sun, Q.; Hinkle, S.N.; Rawal, S.; Mendola, P.; Ferrara, A.; Albert, P.S.; Zhang, C. A prospective and longitudinal study of plasma phospholipid saturated fatty acid profile in relation to cardiometabolic biomarkers and the risk of gestational diabetes. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2018, 107, 1017–1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, A.D.; Gay, M.C.L.; Wlodek, M.E.; Murray, K.; Geddes, D.T. The fatty acid species and quantity consumed by the breastfed infant are important for growth and development. Nutrients 2021, 13, 4183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, W.L.; Armand, M.; Peyre, H.; Sarte, C.; Charles, M.A.; Heude, B.; Bernard, J.Y. Associations between perinatal biomarkers of maternal dairy fat intake and child cognitive development: Results from the EDEN mother-child cohort. medRxiv, 2024; preprint. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Murgia, M.A.; Baptista, J.; Marcone, M.F. Sardinian dietary analysis for longevity: A review of the literature. J. Ethn. Foods 2022, 9, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, J.S.; Imamura, F.; Sharp, S.J.; Koulman, A.; Griffin, J.L.; Mulligan, A.A.; Luben, R.; Khaw, K.T.; Wareham, N.J.; Forouhi, N.G. Changes in plasma phospholipid fatty acid profiles over 13 years and correlates of change: European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition-Norfolk Study. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2019, 109, 1527–1534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brevik, A.; Veierod, M.B.; Drevon, C.A.; Andersen, L.F. Evaluation of the odd fatty acids 15:0 and 17:0 in serum and adipose tissue as markers of intake of milk and dairy fat. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2005, 59, 1417–1422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jenkins, B.; Aoun, M.; Feillet-Coudray, C.; Coudray, C.; Ronis, M.; Koulman, A. The dietary total-fat content affects the in vivo circulating C15:0 and C17:0 fatty acids independently. Nutrients 2018, 10, 1646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prada, M.; Wittenbecher, C.; Eichelmann, F.; Wernitz, A.; Drouin-Chartier, J.P.; Schulze, M.B. Association of the odd-chain fatty acid content in lipid groups with type 2 diabetes risk: A targeted analysis of lipidomic data in the EPIC-Potsdam cohort. Clin. Nutr. 2021, 40, 4988–4999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, W.L.; Bernard, J.Y.; Armand, M.; Sarte, C.; Charles, M.A.; Heude, B. Associations of maternal consumption of dairy products during pregnancy with perinatal fatty acid profile in the EDEN cohort study. Nutrients 2022, 14, 1636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dietary Goals for the United States, Second Edition. Prepared by the Staff of the Select Committee on Nutrition and Human Needs, United States Senate. 1977. Available online: https://archive.org/details/CAT79715358 (accessed on 21 March 2024).

- United States Department of Agriculture. Dietary Guidelines for Americans 2020–2025. Ninth Edition. DietaryGuidelines.gov. Available online: https://www.dietaryguidelines.gov/sites/default/files/2021-03/Dietary_Guidelines_for_Americans-2020-2025.pdf (accessed on 21 March 2024).

- American Heart Association. Saturated Fats. Available online: https://www.heart.org/en/healthy-living/healthy-eating/eat-smart/fats/saturated-fats (accessed on 26 December 2023).

- American Diabetes Association. Fats. Available online: https://diabetes.org/food-nutrition/reading-food-labels/fats#:~:text=The%20goal%20is%20to%20get,or%20less%20of%20saturated%20fat (accessed on 12 May 2024).

- American Academy of Pediatrics Institute for Healthy Childhood Weight, “Healthy Beverage Quick Reference Guide”. Available online: https://downloads.aap.org/AAP/PDF/HealthyBeverageQuickReferenceGuideDownload.pdf (accessed on 21 March 2024).

- WHO. Saturated Fatty Acid and Trans-Fatty Acid Intake for Adults and Children: WHO Guideline; License CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Stewart, H.; Kuchler, F. Fluid Milk Consumption Continues Downward Trend, Proving Difficult to Reverse. USDA Economic Research Service. 2022. Available online: https://www.ers.usda.gov/amber-waves/2022/june/fluid-milk-consumption-continues-downward-trend-proving-difficult-to-reverse/ (accessed on 21 March 2024).

- Mascarehenas, M.; Mondick, J.; Barrett, J.S.; Wilson, M.; Stallings, V.A.; Schall, J.I. Malabsorption blood test: Assessing fat absorption in patients with cystic fibrosis and pancreatic insufficiency. J. Clin. Pharm. 2015, 55, 854–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stallings, V.A.; Mondick, J.T.; Schall, J.I.; Barrett, J.S.; Wilson, M.; Mascarenhas, M.R. Diagnosing malabsorption with systemic lipid profiling: Pharmacokinetics of pentadecanoic acid and triheptadecanoic acid following oral administration in healthy subjects and subjects with cystic fibrosis. Int. J. Clin. Pharm. Ther. 2013, 51, 263–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fomon, S. Infant Feeding in the 20th Century: Formula and Beikost. J. Nutr. 2001, 131, 409S–420S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, S.S.; Costa, A.; Pozza, M.; Vamerali, T.; Niero, G.; Censi, S.; De Marchi, M. How animal milk and plant-based alternatives diverge in terms of fatty acid, amino acid, and mineral composition. NPJ Sci. Food 2023, 7, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tubb, C.; Seba, T. Rethinking food and agriculture 2020–2030: The second domestication of plants and animals, the disruption of the cow, and the collapse of industrial livestock farming. Ind. Biotechnol. 2021, 17, 57–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skeaff, M.; Hodson, L.; McKenzie, J.E. Dietary-induced changes in fatty acid composition of human plasma, platelet, and erythrocyte lipids follow a similar time course. J. Nutr. 2006, 136, 565–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hanus, O.; Krizova, L.; Samkova, E.; Spicka, J.; Kucera, J.; Klimesova, M.; Roubal, P.; Jedelska, R. The effect of cattle breed, season and type of diet on the fatty acid profile of raw milk. Arch. Anim. Breed. 2016, 59, 373–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Couvreur, S.; Hurtaud, C.; Lopez, C.; Delaby, L.; Payraud, J.L. The linear relationship between the proportion of fresh grass in the cow diet, milk fatty acid composition, and butter properties. J. Dairy Sci. 2006, 89, 1956–1969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rego, O.A.; Rosa, H.J.D.; Regalo, S.M.; Alves, S.P.; Alfaia, C.M.M.; Prates, J.A.M.; Vouzela, C.M.; Bessa, R.J.B. Seasonal changes of CLA isomers and other fatty acids of milk fat from grazing dairy herds in the Azores. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2008, 10, 1855–1859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falchero, L.; Lombardi, G.; Gorlier, A.; Lonati, M.; Odoardi, M.; Cavallero, A. Variation in fatty acid composition of milk and cheese from cows grazed on two alpine pastures. Dairy Sci. Technol. 2010, 90, 657–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abouel-Yazeed, A.M. Fatty acids profile of some marine water and freshwater fish. J. Arab. Aquac. Soc. 2013, 8, 283–292. [Google Scholar]

- Batis, C.; Sotres-Alvarez, D.; Gordon-Larsen, P.; Mendez, M.A.; Adair, L.; Popkin, B. Longitudinal analysis of dietary patterns in Chinese adults from 1991 to 2009. Br. J. Nutr. 2014, 111, 1441–1451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martins, I.S.; Schrodt, F.; Blowes, S.A.; Bates, A.E.; Bjorkman, A.D.; Brambilla, V.; Carvajal-Quintero, J.; Chow, C.F.Y. Daskalova, G.N.; Edwards, K.; et al. Widespread shifts in body size within populations and assemblages. Science 2023, 381, 1067–1071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wohlrab, J.; Gabel, A.; Wolfram, M.; Grosse, I.; Neubert, R.H.H.; Steinback, S.C. Age- and diabetes-related changes in the free fatty acid composition of the human stratum corneum. Skin Pharmacol. Physiol. 2018, 31, 283–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thewissen, J.G.M.; Cooper, L.N.; George, J.C.; Bujpai, S. From land toa water: The origin of whales, dolphins, and porpoises. Evol. Educ. Outreach 2009, 2, 272–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venn-Watson, S.; Ridgway, S.H. Big brains and blood glucose: Common ground for diabetes mellitus in humans and healthy dolphins. Comp. Med. 2007, 57, 390–395. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Colagiuri, S.; Miller, J.B. The ‘carnivore connection’—Evolutionary aspects of insulin resistance. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2002, 56, S30–S35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craik, J.D.; Young, J.D.; Cheeseman, C.I. GLUT-1 mediation of rapid glucose transport in dolphin (Tursiops truncatus) red blood cells. Am. J. Physiol. Reg. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 1998, 274, R112–R119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Montgomery, S.H.; Geisler, J.H.; McGowen, M.R.; Fox, C.; Marino, L.; Gatesy, J. The evolutionary history of cetacean brain and body size. Evolution 2013, 67, 3339–3353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bielec, P.E.; Gallagher, D.S.; Womack, J.E.; Busbee, D.L. Homologies between human and dolphin chromosomes detected by heterologous chromosome painting. Cytogenet. Cell Genet. 1998, 81, 18–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Venn-Watson, S. Dolphins and diabetes: Applying one health for breakthrough discoveries. Front. Endocrinol. 2014, 5, 227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venn-Watson, S.; Jensen, E.D.; Smith, C.R.; Xitco, M.; Ridgway, S.H. Evaluation of annual survival and mortality rates and longevity of bottlenose dolphins (Tursiops truncatus) at the United States Navy Marine Mammal Program from 2004 through 2013. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 2015, 246, 893–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venn-Watson, S.; Smith, C.R.; Jensen, E.D. Assessment of increased serum aminotransferases in a managed Atlantic bottlenose dolphin (Tursiops truncatus) population. J. Wildl. Dis. 2008, 44, 318–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eder, S.K.; Feldman, A.; Strebinger, G.; Kemnitz, J.; Zandanell, S.; Niderseer, D.; Strasser, M.; Haufe, H.; Sotlar, K.; Stickel, F.; et al. Mesenchymal iron deposition is associated with adverse long-term outcome in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Liver Int. 2020, 40, 1872–1882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mazzaro, L.M.; Johnson, S.; Fair, P.; Bossart, G.; Carlin, K.P.; Jensen, E.D.; Smith, C.R.; Andrews, G.A.; Chavey, P.S.; Venn-Watson, S. Iron indices in bottlenose dolphins (Tursiops truncatus). Comp. Med. 2012, 62, 508–515. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, S.P.; Venn-Watson, S.K.; Cassle, S.E.; Smith, C.R.; Jensen, E.D.; Ridgway, S.H. Use of phlebotomy treatment in Atlantic bottlenose dolphins with iron overload. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 2009, 235, 194–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, N.; Lu, Y.; Cao, L.; Lu, M. The association between non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and serum ferritin levels in American adults. J. Clin. Lab. Anal. 2022, 36, e24225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venn-Watson, S.; Smith, C.R.; Stevenson, S.; Parry, C.; Daniels, R.; Jensen, E.; Cendejas, V.; Balmer, B.; Janech, M.; Neely, B.A.; et al. Blood-based indicators of insulin resistance and metabolic syndrome in bottlenose dolphins (Tursiops truncatus). Front. Endocrinol. 2013, 4, 136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deugnier, Y.; Bardow-Jacquet, E.; Laine, F. Dysmetabolic iron overload syndrome (DIOS). La Presse Med. 2017, 46, e306–e311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pietrangelo, A. Hereditary hemochromatosis: Pathogenesis, diagnosis, and treatment. Gastroenterology 2010, 139, 393–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piperno, A. Classification and diagnosis of iron overload. Haematologica 1998, 83, 447–455. [Google Scholar]

- Fargion, S. Dysmetbolic iron overload syndrome. Haematologica 1999, 84, 97–98. [Google Scholar]

- Deugnier, Y.; Mendler, M.H.; Moirand, R. A new entity: Dysmetabolic hepatosiderosis. Presse Med. 2000, 29, 949–951. [Google Scholar]

- Altes, A.; Remacha, A.F.; Sureda, A.; Martino, R.; Briones, J.; Brunet, S.; Baiget, M.; Sierra, J. Patients with biochemical iron overload: Causes and characteristics of a cohort of 150 cases. Ann. Hematol. 2003, 82, 127–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deugnier, Y.; Turlin, B. Pathology of hepatic iron overload. World J. Gastroenterol. 2007, 21, 4755–4760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, L.Y.; Chang, S.D.; Sreenivasan, G.M.; Tsang, P.W.; Broady, R.C.; Li, C.H.; Zaypchen, L.N. Dysmetabolic hyperferritinemia is associated with normal transferrin saturation, mild hepatic iron overload, and elevated hepcidin. Ann. Hematol. 2011, 90, 139–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dongiovanni, P.; Fracanzani, A.L.; Fargion, S.; Valenti, L. Iron in fatty liver and in the metabolic syndrome: A promising therapeutic target. J. Hepatol. 2011, 55, 920–932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stechemesser, L.; Eder, S.K.; Wagner, S.K.; Patsch, W.; Feldman, A.; Strasser, M.; Auer, S.; Niderseer, D.; Huber-Schonauer, U.; Paulweber, B.; et al. Metabolomic profiling identifies potential pathways involved in the interaction of iron homeostasis with glucose metabolism. Mol. Metab. 2016, 6, 38–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbalho, S.M.; Laurindo, L.F.; Tofano, R.J.; Flatro, U.A.P.; Mendes, C.G.; Goulart, R.A.; Milla Briguezi, A.M.G.; Bechara, M.D. Dysmetabolic iron overload syndrome: Going beyond the traditional risk factors associated with metabolic syndrome. Endocrines 2023, 4, 18–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malesza, I.J.; Bartkowiak-Wieczorek, J.; Winkler-Galicki, J.; Nowicka, A.; Dzieciolowska, D.; Blaszczyk, M.; Gajniak, P.; Slowinska, K.; Niepolski, L.; Walkowiak, J.; et al. The dark of iron: The relationship between iron, inflammation and gut microbiota in selected diseases associated with iron deficiency anaemia—A narrative review. Nutrients 2022, 14, 3478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jezequel, C.; Laine, F.; Laviolle, B.; Kiani, A.; Bardou-Jacquet, E.; Deugnier, Y. Both hepatic and body iron stores are increased in dysmetabolic iron overload syndrome. A case-control study. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0128530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Datz, C.; Muller, E.; Aigner, E. Iron overload and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Minerva Endocrinol. 2017, 42, 173–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venn-Watson, S.; Parry, C.; Baird, M.; Stevenson, S.; Carlin, K.; Daniels, R.; Smith, C.R.; Jones, R.; Wells, R.S.; Ridgway, S.; et al. Increased dietary intake of saturated fatty acid heptadecanoic acid (C17:0) associated with decreasing ferritin and alleviated metabolic syndrome in dolphins. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0132117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venn-Watson, S.; Baird, M.; Novick, B.; Parry, C.; Jensen, E.D. Modified fish diet shifted serum metabolome and alleviated chronic anemia in bottlenose dolphins (Tursiops truncatus): Potential role of odd-chain saturated fatty acids. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0230769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Otogawa, K.; Kinoshita, K.; Fujii, H.; Sakabe, M.; Shiga, R.; Nakatani, K.; Ikeda, K.; Nakajima, Y.; Ikura, Y.; Ueda, M.; et al. Erythrophagocytosis by liver macrophages (Kupffer cells) promotes oxidative stress, inflammation, and fibrosis in a rabbit model of steatohepatitis: Implications for the pathogenesis of human nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Am. J. Pathol. 2007, 170, 967–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soboleva, M.K.; Sharapov, V.I.; Grek, O.R. Fatty acids of the lipid fraction of erythrocyte membranes and intensity of lipid peroxidation in iron deficiency. Bull. Exp. Biol. Med. 1994, 117, 601–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venn-Watson, S. Compositions for Diagnosis and Treatment of Type 2 Diabetes. U.S. Patent 10,449,170B2, 22 October 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Venn-Watson, S. Methods for Use in Support of Planned Supplement and Food Ingredient Products for Diagnosis and Treatment of Metabolic Syndrome. U.S. Patent 11,116,740B2, 14 September 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Venn-Watson, S. Compositions and Methods for Diagnosis and Treatment of Anemia. U.S. Patent 10,238,618B2, 26 March 2019. [Google Scholar]

| Fish Species | C15:0 Content (% Total Fatty Acids) |

|---|---|

| Mullet | 1.18% |

| Catfish | 0.94% |

| Striped red mullet | 0.92% |

| Sea bass | 0.82% |

| Eel | 0.73% |

| Red porgy | 0.63% |

| Golden grouper | 0.62% |

| Sardine | 0.60% |

| Carp | 0.53% |

| Sole | 0.50% |

| Sea bream | 0.42% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Venn-Watson, S. The Cellular Stability Hypothesis: Evidence of Ferroptosis and Accelerated Aging-Associated Diseases as Newly Identified Nutritional Pentadecanoic Acid (C15:0) Deficiency Syndrome. Metabolites 2024, 14, 355. https://doi.org/10.3390/metabo14070355

Venn-Watson S. The Cellular Stability Hypothesis: Evidence of Ferroptosis and Accelerated Aging-Associated Diseases as Newly Identified Nutritional Pentadecanoic Acid (C15:0) Deficiency Syndrome. Metabolites. 2024; 14(7):355. https://doi.org/10.3390/metabo14070355

Chicago/Turabian StyleVenn-Watson, Stephanie. 2024. "The Cellular Stability Hypothesis: Evidence of Ferroptosis and Accelerated Aging-Associated Diseases as Newly Identified Nutritional Pentadecanoic Acid (C15:0) Deficiency Syndrome" Metabolites 14, no. 7: 355. https://doi.org/10.3390/metabo14070355

APA StyleVenn-Watson, S. (2024). The Cellular Stability Hypothesis: Evidence of Ferroptosis and Accelerated Aging-Associated Diseases as Newly Identified Nutritional Pentadecanoic Acid (C15:0) Deficiency Syndrome. Metabolites, 14(7), 355. https://doi.org/10.3390/metabo14070355