5. Discussion

As expected, the study indicated an increase in abnormal eating habits in the group of women with a BMI ≥ 25 kg/m

2 compared to the normal-weight group among patients with PCOS phenotype A. According to the literature review, the prevalence of eating disorders, especially bulimia and binge eating disorders, as well as the presence of unhealthy eating habits, is higher in women with PCOS compared to healthy women, as suggested by some researchers, irrespective of their BMI [

18,

19,

20,

21,

22]. No publications evaluating differences in the severity of abnormal eating habits between the normal-weight group and the group of women with a BMI ≥ 25 kg/m

2 and PCOS phenotype A were found in the available literature. The most similar study is the one published in 2019 by Pirotta et al. The study showed that abnormal eating habits are more common in women with PCOS compared to a group of healthy women, and a dietary restriction is the only abnormal eating habit that occurs more frequently in the group of women with PCOS. They also emphasized that a significant predictor of the occurrence of both eating disorders and poor eating habits is increased BMI alone, irrespective of PCOS [

23].

The study showed no significant differences in the severity of impulsivity and aggression between the normal-weight group and the group of women with a BMI ≥ 25 kg/m

2 and PCOS phenotype A. Unfortunately, the results obtained cannot be compared with those of other authors, as no available publication on aggression and impulsivity in women with PCOS has divided the control and study groups according to BMI in women with PCOS phenotype A. In all available studies addressing aggression in women with PCOS, the control group was composed of healthy women. Researchers report, among other things, a higher number of hospitalizations for self-harm (7.2% to 2.9%), more frequent suicide attempts (14% to 2%), and more intense feelings and expressions of anger combined with poorer self-control in women with PCOS compared to healthy women [

24,

25,

26]. In addition, the available studies on the severity of anger expression in relation to BMI only apply to women without PCOS and show no significant correlation between those variables [

27]. Most of the available literature focuses on the study of the severity of impulsivity as one of the symptoms of psychiatric disorders such as Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder or impulse control disorders observed in eating disorders, the prevalence of which is described as higher in a group of women with PCOS compared to women without PCOS [

28,

29].

The study further showed that there were no statistically significant differences in scores for the assessed scales of the SRS questionnaire between the study group and the control group. In the available literature, there are both descriptions of the prevalence of sexual dysfunction in patients with PCOS compared to groups of women without the syndrome and the absence of such differences [

30,

31,

32,

33,

34,

35,

36,

37,

38,

39]. In addition, the relationship between BMI and sexual functioning in women with PCOS is inconclusive [

40]. Studies comparing the sexual functioning of obese and normal-weight PCOS patients provide the following findings: higher BMI is associated with a significant reduction in orgasm, reduced sexual activity, reduced sexual satisfaction, overall poorer sexual functioning, and a sense of lower sexual attractiveness [

30,

31,

35,

40,

41]. Interestingly, it is noted that obesity and overweight alone do not affect sexual activity, but the co-occurrence of obesity and PCOS may interfere with it [

40]. No publications were found in the available literature assessing the difference in severity of the tendency to engage in risky sexual behavior among women with PCOS phenotype A with a BMI-based stratification.

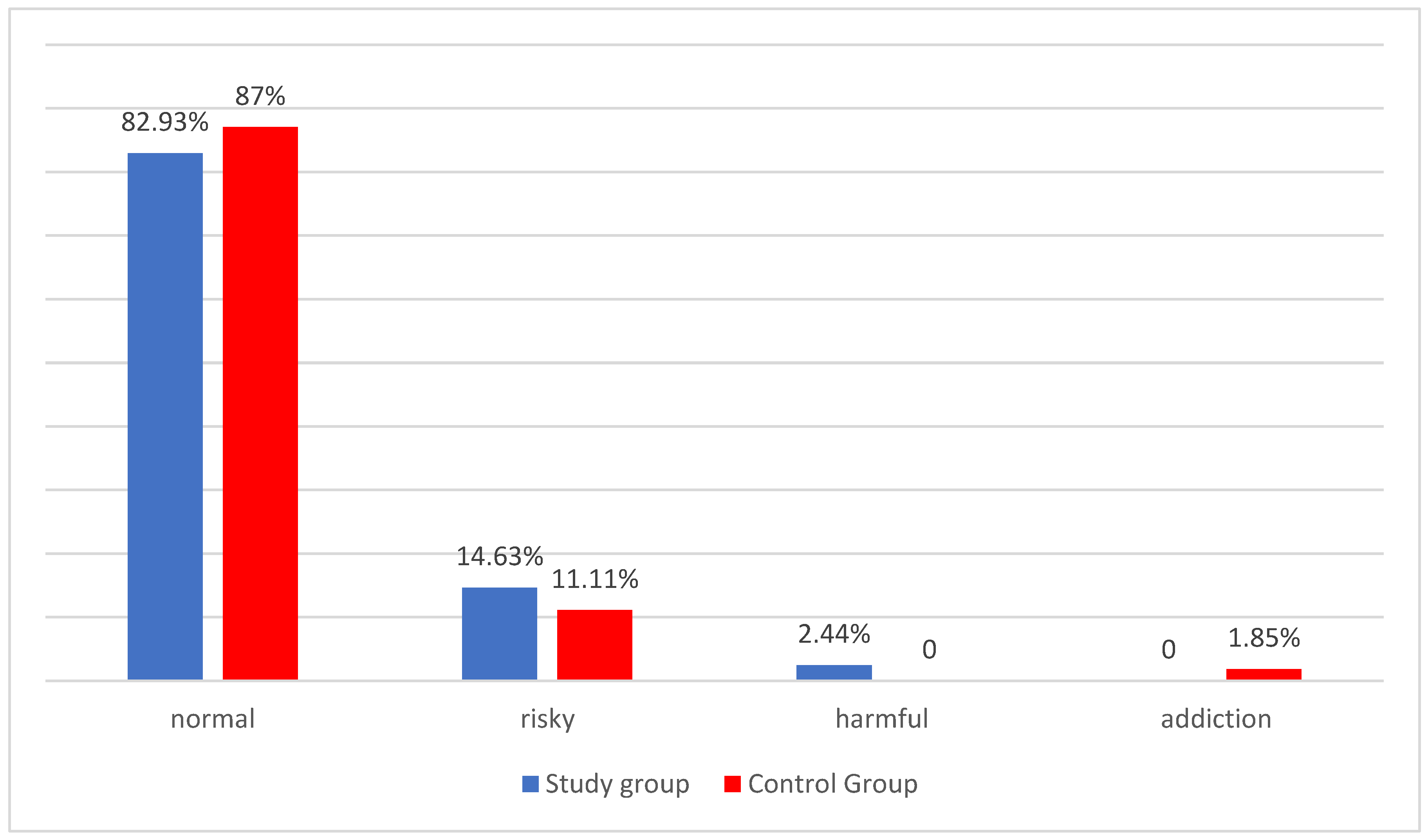

In the next stage of the study, it was observed that the risky pattern of alcohol consumption was slightly more frequent in the study group than in the control group, while the low-risk drinking pattern was more frequent in the control group. Given the very high prevalence of individuals in the overall population included in the analysis whose pattern is defined as a low-risk pattern (81 women), which represents a deviation of the distribution of the variables from the normal distribution for the interpretation of the variation in these quantitative variables, a non-parametric test (Anova Kruskal-Wallis) was used. Considering that more caution should be exercised with this test in drawing far-reaching conclusions from the study, it was decided to terminate the study of the severity of these characteristics at this stage, making it impossible to demonstrate the statistical significance of these results. There is a clear gap in the available literature when it comes to research on alcohol consumption patterns in women with PCOS. In the Chinese study published in 2014, Zhang J. et al. described alcohol drinking as an independent risk factor for PCOS [

42]. In contrast, Zhang B. et al. in 2020 found no difference between the three study groups (a group of women with PCOS and oligo-ovulation, a group of women with PCOS and normal ovulation, and a group of healthy women without PCOS) in alcohol consumption patterns [

43]. Similar findings were published by Sánchez-Ferrer et al. in 2020 and Cutillas-Tolín et al. in 2021, showing no differences in alcohol consumption patterns between a group of women with PCOS and a group of healthy women [

44,

45]. However, all the cited studies differ significantly in methodology, did not use the AUDIT test, and only asked about drinking alcohol. No studies comparing alcohol consumption patterns in women with PCOS phenotype A with a BMI-based stratification were found in the available literature.

In both the study group and the control group, there were no statistically significant correlations between the severity of impulsivity and the symptoms of clinical hyperandrogenism or the results of biochemical tests. There are inconclusive reports in the literature on the relationship between testosterone levels and impulsivity in healthy women without PCOS, confirming an indirect effect or showing a negative correlation [

46,

47]. An association has been shown between higher testosterone concentrations and more severe symptoms of Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder in women without diagnosed PCOS [

48]. Özdil et al. found a significant correlation between increased levels of total testosterone (TT) and higher scores on the total impulsivity scale, as well as between increasing values of the free androgen index (FAI) and higher scores on the total impulsivity scale, or impulsivity due to a lack of planning and motor impulsivity [

49]. In addition, they showed a significant correlation between decreasing levels of sex hormone-binding globulin and the motor impulsivity scale and impulsivity related to a lack of planning. No such relationship has been demonstrated in this study. It is difficult to explain the reasons for this discrepancy given that the study populations were very similar in terms of both age and size, the location of the study, and the fact that the same questionnaire was used in both studies to assess impulsivity. A noticeable difference is the selection of the group. It is possible that the final results were influenced by ethnic, cultural, and genetic differences between the groups of women included in the study. The study by Özdil et al. was conducted in Turkey, while this one was carried out in Poland.

No statistically significant associations were found between indicators of aggression severity, symptoms of clinical hyperandrogenism, and biochemical test results in the compared groups. There are descriptions in the available literature of a relationship between testosterone concentrations and the severity of aggression and anger, but the available studies differ significantly in the population of subjects [

7,

8,

50]. Barry et al. published a study negating the relationship between androgen levels and aggression severity in women with PCOS; however, in their study, the control group was infertile women without PCOS [

51]. Again, the only findings with which to compare the results obtained in this study are those of a previously cited study published by Özdil et al. The study showed that as TT and FAI concentrations increase, the feeling and expression of anger also increase, and the ability to control and inhibit its expression decreases. They identify FAI as a predictor of feeling, expressing, and controlling anger [

49]. In the present study, a complementary relationship was not obtained. As before, it is difficult to explain the reasons for this discrepancy given that the study populations were very similar in terms of age, size, and location. Different questionnaires assessing the severity of aggression or anger were used as in the previous case. It is also possible that the final results were influenced by ethnic, cultural, and genetic differences between the groups of women included in the study.

Several clinical implications of our results need to be considered. Firstly, a thorough medical interview with an assessment of eating habits should be conducted for patients with PCOS. Finding people with poor eating habits would allow them to receive additional psychological, dietary, or psychiatric support. Secondly, detailed psychoeducation in the field of healthy lifestyles should be provided. Finally, the results of this work could serve to determine the areas for further investigation of the mechanisms and severity of impulsivity and aggression in patients with PCOS, with special attention to their behavioral manifestations.

There are various limitations to the study that need to be considered. Firstly, we did not run a power analysis to assess the adequate sample size prior to the enrollment of patients, which is a major limitation to our study. The sample size of the study group was relatively small, which might contribute to false positive or false negative results; thus, replication studies with larger sample sizes are necessary. This is due to the broad exclusion criteria, which resulted in a 56% reduction in the study population. Secondly, the study design, based on self-administered questionnaires, retrospectively resulted in a negative impact on the sample size. A large number of the respondents withdrew from participating in the survey when filling out the questionnaires (16% of the respondents). Furthermore, we cautiously speculate that some of the questions, especially those related to alcohol consumption patterns or engaging in risky sexual behavior after psychoactive substance use, were answered with a certain degree of self-correction, driven by ongoing hospitalization and possible concern that such information might affect respondents’ treatment or influence the direction of further diagnosis. As with the behavioral manifestations of aggression and impulsivity in this population, there is relatively little data on the aggressiveness and impulsiveness of women with PCOS. In particular, the areas of risky sexual behavior, alcohol consumption patterns, and inappropriate eating habits in women with PCOS should be thoroughly assessed in the future. Such a scarcity of knowledge is reflected in the small number of sources that were cited in our study, especially those from the last five years. Consequently, further studies with larger groups are needed to confirm our findings.