1. Introduction

Knowledge is the key marketing strategy for micro, small, and medium enterprises to enter, understand, utilize, and reach the place in the hearts of customers. Therefore, it requires attitudes and behaviors that have skills in increasing networks/friendships to create or exploit opportunity from a competitive market [

1]. The basis of the existence of a product that the customer may demand is derived from the application and management of knowledge in the planning arrangements related to the circulation of raw materials and finished materials, processes and production, distribution services, and the transparency of liabilities and business assets. Market knowledge management capability is the competence and modern business asset that SMEs must have in maintaining competitiveness [

2].

Market knowledge is a source of competitive advantage and a concept that can be measured for its influence on company performance [

3,

4]. Integrating market knowledge into marketing capabilities can help companies grow [

3]. To implement and develop these goals requires a reputation in designing the market knowledge system [

5]. In order to generate high quality market knowledge that can serve as an intermediary bridge, it requires the support of information technology to provide learning in capturing signals from knowledge providers [

6,

7]. The study of Hou and Chien [

2] exploring the impact of market knowledge management competencies on performance through “dynamic capabilities” finds a positive relationship between dynamic capabilities, market knowledge management competencies, and business performance. The dynamic capabilities in marketing perspectives, according to Barrales-Molina, Martínez-López, & Gázquez-Abad [

8], today become one of the significant problems with the role of the marketing function in the development of dynamic capabilities so that it is necessary to collaborate on marketing and operations to integrate market knowledge into the supply chain. It is therefore necessary for the participation of middle managers in the planning process to identify potential business and relevant supply chains to become informed in marketing strategy decisions [

9].

Research on the dynamic marketing capabilities from Barrales-Molina et al. [

8] still rarely analyzes the effects of dynamic marketing capabilities on strategic variables of a company, such as performance or (sustainable) competitive advantage. While in a dynamic global market, the role of internal and external functions of the company is needed in the process of creating product value that is difficult to imitate by competitors as a competitive advantage [

10]. Different capabilities of resource quality and value characteristics inherent in high performing products are the company’s goal to grow an existing market share and win the competition [

11]. According to Hollebeek, Srivastava, and Chen [

12], in today’s rapidly growing marketplace, the organization’s agility in responding (or ideally, getting around) changing customer-driven trends is the key to competitive success [

13]. Kumar and Pansari [

14] focus on understanding internal (employee) and external (customer) engagement as organizational stakeholders and found that the level of engagement can be improved by identifying the current level of internal (employee) and external (customer) engagement and applying to relevant strategies.

Meanwhile, in strategic management research based on microfoundations, the value of co-creation is viewed in the context of a service ecosystem involving the role of actors’ attachment. It indicates the need to explore attachments not only as customer engagement but also the acumen of other actors, such as from suppliers, manufacturers, retailers, and providers [

15]. According to Finsterwalder [

16], to understand and build multi-actor engagement requires the use of item measurements and the appropriate scale to assess the degree of engagement of each actor in the focus of the interaction, whether to the perpetrator or other objects, such as resources, or both as the focus of sustainable value creation activities. According to Frow, Nenonen, Payne, and Storbacka [

17], sustainable creation benefits include improved employee integration of supply chain integrity, while from a customer perspective, interaction with a company enables sustainable creation of the consumption experience, enhances customer brand experience, and rewards for strengthening relationships. Meanwhile, Grönroos and Helle [

18] argue that business engagement is established on mutually beneficial calculations of benefits, and Marcos-cuevas, Nätti, Palo, and Baumann [

19] argue that sustainable creation practices and capabilities are reinforced by mutual ends together widely in the mind (i.e., goals). Additionally, they also argue for continuous engagement in expanding the scope and nature of the collaborative effort (i.e., engagement) to create value in a shared sphere where the actors involved operate over time (i.e., sustainability). It can be interpreted that engagement and sustainability is about the company’s ability to establish relationships with employees, supply chains, and customers [

20,

21]. Thus, engagement and sustainability is about a relationship in creating shared value. While in view of Ranjan & Read [

22], relationships are defined as engagement, network, lasting exchange, interdependence, and collaboration, and they are a mutual, reciprocal, and recurring process that are the basis of the relationship between customers and objects in an active communication environment and/or attachment. The linkage is reinforced by Karagouni and Protogerou [

21], who suggest that research both in the perspective of dynamic ability and sustainable value creation, highlights the role of capabilities that enable firms to engage in value creation activities, while dynamic ability can be considered as a facilitator in the process of sustainable value creation. Meanwhile, research on the role of capability in view of microfoundations by Pérez-Cabañero, Cruz-Ros, and González-Cruz [

23] explains that marketing ability is a strategy part of the dynamic capabilities embedded in the business management process [

4].

Based on these explanations, it can be stated that the dynamic marketing engagement study has two solid foundations. First, that the context of dynamic marketing ability has a relationship with internal and external engagement as a process of competitive advantage. Second, there is a need to include the engagement of internal and external sources of the company as a source of knowledge information from a continuously growing and sustainable market [

8,

15,

24]. To follow up these needs into this research, it is necessary to discuss the capacity gap from several studies related to dynamic capability and internal/external engagement to the company’s business performance. These differences will be described in the research gap and are interpreted with an SME business perspective. According to Hou and Chien [

2], market knowledge has become a major asset of modern business and the key to maintaining competitiveness. The study of Dietmar, Jaeger, and Staubmann [

25] also explains that product-related export/service capabilities, partner relationship capabilities, and relationship process capabilities can replace resource shortages. In contrast to Park and Kim’s [

26] research explaining the type of strategy and market maturity affecting the level of dynamic capabilities, those obtained from the environment (such as customer types and technological regimes) have no relationship to dynamic levels of ability. As with Anabel Fernández-Mesa, Alegre-Vidal, Chiva-Gómez, & Gutiérrez-Gracia [

27], the organization’s learning capabilities are needed to improve product innovation through the intermediate of design management capabilities. This is useful for the business performance of a customer-oriented company, as the effect of market intervention can improve company performance [

28]. In addition, adaptability, absorptive capacity, and corporate innovation are essential in establishing relationships in competitive markets to achieve higher performance [

29].

Meanwhile, in Wilhelm’s research, Wilhelm, Schlömer, and Maurer [

30] state that dynamic capabilities have different performance effects in dynamic environments, especially when dynamic capabilities increase the effectiveness of operational routines at both the (high and low) levels of the dynamic environment. However, when the cost of increased efficiency is taken into account, the dynamic environment makes a difference, where the ability in a low dynamic environment indicates a smaller value because it does not impact the efficiency of the operating routine, whereas in high dynamic environments, it leads to higher efficiency of operating routines. It is crucial in developing SMEs that survive using resource-based views efficiently to transform dynamic capabilities into a key driver of SME success. Therefore, the SME strategy for managing the environment of public concern should be green business, while the ability and resources of the organization have an important role to improve the business performance of the company [

31]. To fill this research gap, the authors refer to the SME industry using two offline marketing systems and online. The reference is due to the low market knowledge that SMEs have to effectively use the marketing system side by side between offline and online. Although basically, SMEs have started to use the internet marketing system, such as the use of social media, as an easy and practical marketing medium, but that is still not maximized. This is based on the focus of marketing that still relies on physical appearance and that is most still trusted by the customer in assessing the product and ease in the payment process. One study linking dynamic capabilities with social media and performance was performed by Saavedra, Andreu, and Criado [

32] of 191 various sectoral companies in Spain who found evidence of the intensity effects of moderating social media marketing on the strength of relationships and the importance of strong and committed marketing strategies in an online social network for each type of business. In Indonesia, social media used by SMEs is still at the stage of following the social trend in developing communication. Although not realized, SMEs have felt the new market and the opportunity to reach customers by entering the online marketing system. The SMEs’ lack of understanding is not based on online marketing learning knowledge and they are still reluctant to integrate marketing from online systems to online. This may be due to the inability or absence of coordination within the SME organization. According to Zhang and Wu [

33], the ability to sense is the company’s unique ability to scan and track by exploring markets and technologies. Essentially, the ability to feel is useful for realizing the company’s potential to develop new products and enhance the company’s competitiveness in the face of rapid environmental change.

2. Materials and Methods

In addition to online marketing learning knowledge factors and the inability to integrate marketing from offline to online systems, business phenomena are also a way of viewing angles to see company performance. The more tight the business competition, the more open the opportunities and threats that arise. Polmasari [

34] reported in possore.com that the phenomenon of the development of the digital commerce or e-commerce market is currently in line with government programs and activities in encouraging SMEs, especially export-oriented ones, to grow. The research results of the Indonesian E-commerce Association (idEA), Google Indonesia, and Taylor Nelson Sofres show that in 2013 the value of the Indonesian e-commerce market reached USD 8 billion (IDR 94.5 trillion). Based on data from the Ministry of Cooperatives and Small and Medium Enterprises, the number of SMEs in Indonesia in 2013 amounted to 57,895,721 units (99.99%), contributing to GDP (constant price) of USD 1,536,918.8 billion (57.56%) and absorbing manpower of 114,144,082 people (96.99%) (Data of Micro, Small, Medium Enterprises and Large Enterprises (UB) Year 2012–2013, 2013). Meanwhile, in the report of Wardhana [

35], based on data from the Ministry of Cooperatives and Small and Medium Enterprises until 2013, there are 55 to 56 million SMEs in Indonesia and only about 75 thousand to 100 thousand who have a website (site). Similarly, Deloitte 2015 reports that 36% of SMEs in Indonesia are still offline, 37% have only very basic online capabilities, 18% have intermediate online capabilities, and 9% have advanced online business capabilities with e-commerce capabilities.

The data clearly affirm the vital role of small and medium enterprises in Indonesia in realizing national goals to create jobs, improve living standards, and international competitiveness, which is why this digital requirement is an important agenda for the Indonesian government. From the results of the research, SMEs using digital technology can increase revenues by up to 80% or be 17 times more likely to be innovative and ready to compete internationally, and one and a half times more likely to increase employment. Therefore, government intervention in increasing broadband access to help SMEs become digital businesses, expanding e-payments, investment access, and e-government services is very influential.

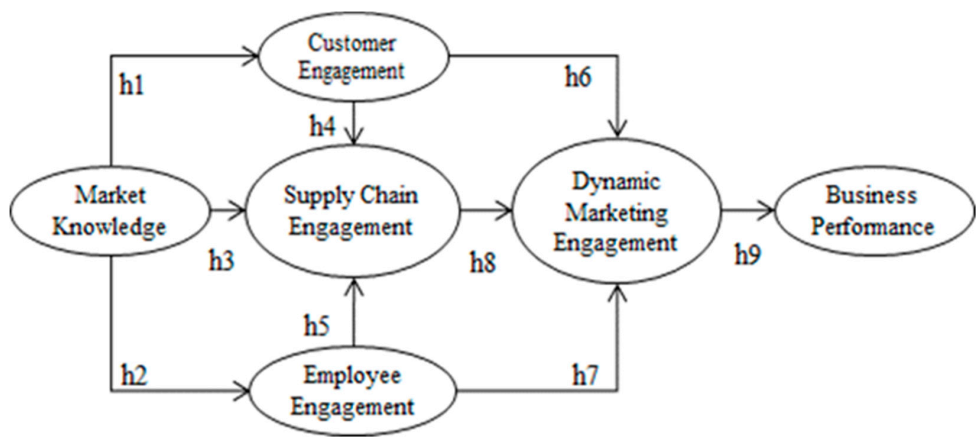

The description of secondary data shows the phenomenon of the development of the digital SME industry in general and also indicates the existence of a marketing business phenomenon in the digital system. Therefore, learning is needed in integrating business into the online marketing system and the importance of coordination within the organization to equip the knowledge of the SME market as a basis for dynamic capability in order to survive and compete in a competitive market environment. Based on the background, research gaps, and business phenomena that occur in the world of digital SME industry, it is necessary to explore a research model that connects dynamic marketing capabilities with business performance on digital SMEs. Therefore, the research problem is formulated as follows: “How to build a SME marketing strategy in an offline system through a new theoretical approach to overcome the research gap in dynamic ability and performance”. Furthermore, from the essence of synthesis theory and a literature study is proposed a new concept of dynamic marketing involvement derived from dynamic capability; a market knowledge strategy that engages customers, employees, and the supply chain for competitive advantage. Then, from the synthesis process produces a proposition that is:

“Dynamic marketing capabilities and multi-actor involvement as a competitive advantage strategy of a company on the concept of dynamic marketing engagement has the potential to improve the company’s business performance”.

The population to be researched is the owners, managers, or owners and managers of SME businesses marketing with two marketing systems, from offline to online, in Indonesian SMEs, spread over 7 (seven) sub-districts, specifically in the trade and industry centers of SMEs in Indonesia [

36,

37]. This research develops basic theoretical models and empiric research models to explain how business performance is improved, as shown in

Figure 1. The research model was developed by reviewing previous research on the relationship of the variables, so that nine hypotheses were built. Data came from as many as 250 questionnaires that were distributed and as many as 249 questionnaires were re-processed. The analysis tool used was structural equation modeling (SEM) with SPSS.AMOS software.

3. Results

The results of statistical tests on the research model show the value of the goodness of fit index, among others, and chi-square, probability, Goodness of Fit Index (GFI), Adjusted Goodness of Fit Index (AGFI), The Minimum Sample Discrepancy Function Divided with degree of Freedom (CMIN/DF), Tucker Lewis Index (TLI), and Comparative Fit Index (CFI) indicate that it has a decent value as indicated because it has the expected range value by the indicator used, so it is feasible to test the hypothesis, presented as follows in

Table 1.

The result of hypothesis testing shows empirical evidence from nine hypotheses submitted that are all accepted, and presented as follows in

Table 2.

Hypothesis 1 (H1). Market Knowledge positively affects Customer Engagement.

The testing parameter of the influence of Market Knowledge on Customer Engagement shows the result of the estimated value of 0.419, the value of c.r. is 4.068 > 2.0, and the probability value is 0.000 > 0.05. It can be concluded statistically that the variable Knowledge Market proved to have a positive effect on Customer Engagement. This result is the same as developed by Cui and Wu [

38] in that Market Knowledge established with Customer Engagement in joint development has a significant impact on the design of the organization. The findings are also consistent with the findings of Chien and Chen [

39], Lau [

40], and Abdolmaleki and Ahmadian [

41] who discovered Market Knowledge with significant new product development on Customer Engagement.

Hypothesis 2 (H2). Market Knowledge positively affects Employee Engagement.

The influence of Market Knowledge on Employee Engagement shows an estimated value of 0.616, a C.R. value of 4.888 > 2.0, and a probability value of 0.000 < 0.05. It can be concluded statistically that the variable of Market Knowledge proved to have positive effect on Employee Engagement. These results are the same as those found by Ye, Marinova, and Singh [

42] and Yang Chen, Tang, Jin, Li, and Paille [

43]. The findings of Chen, Wang, Huang, and Shen [

44] show market linking ability is considered to be an important ability that must take into account the firm’s engagement in service innovation that requires integration of employees.

Hypothesis 3 (H3). Market Knowledge positively affects Supply Chain Engagement.

The effect of Market Knowledge on Supply Chain Engagement shows the result of the estimated value of 0.307, the value of C.R. of 2.410 > 2.0, and the probability value 0.016 < 0.05. It can be concluded statistically that the variable of Market Knowledge proved to positively influence Supply Chain Engagement. The results are the same as the findings of Feng and Wang [

45] and Kanapathy, Khong, and Dekkers [

46]. Likewise, Feng and Zhao’s [

47] findings suggest market knowledge in relationships with suppliers has a positive influence with supplier engagement.

Hypothesis 4 (H4). Customer Engagement positively affects Supply Chain Engagement.

The influence of Customer Engagement on Supply Chain Engagement shows the result of the estimated value of 0.316, the value of C.R. is 3.117 > 2.0, and the probability value is 0.002 < 0.05. It can be concluded statistically that the variable of Customer Engagement proved to have a positive effect on Supply Chain Engagement. These results are the same as those developed by Kannan and Choon Tan [

48] and Singh and Power [

49], likewise with the findings of Danese and Romano [

50] and He, Keung Lai, Sun, and Chen [

51]. The findings of Siew-Phaik, Downe, and Sambasivan [

52] also state the alliance’s strategic alliance motives (suppliers, producers, and customers) have a positive relationship with the level of interdependence.

Hypothesis 5 (H5). Employee Engagement positively affects Supply Chain Engagement.

The influence of Employee Engagement on Supply Chain Engagement shows the result of the estimated value of 0.369, the value of C.R. of 4.348 > 2.0, and the probability value 0.000 < 0.05. It can be concluded statistically that Employee Engagement variables proved to positively affect Supply Chain Engagement. These results are the same as those developed by Vanichchinchai [

53] and Huo, Han, Chen, and Zhao [

54]. Similarly, Alfalla-Luque, Marin-Garcia, and Medina-Lopez [

55] found that the relationship between employee commitment and operational performance is fully mediated by supply chain integration, which finds significant Employee Engagement to Supply Chain Engagement.

Hypothesis 6 (H6). Customer Engagement positively affects Dynamic Marketing Engagement.

The influence of Customer Engagement on Dynamic Marketing Engagement shows the result of an estimated value equal to 0.213, value of C.R. equal to 2.120 > 2.0, and probability value 0.034 < 0.05. Then, it can be concluded statistically that the Customer Engagement variable proved to have a positive effect on Dynamic Marketing Engagement. These results are the same as those developed by Agarwal and Selen [

56]. According to Anabel Fernández-Mesa et al. [

27] in their findings, there is a positive relationship between dynamic capabilities in design management and product innovation performance. While Gu, Jiang, and Wang [

57] found that customer feedback and networking have a positive impact on high-tech SMEs’ innovation performance.

Hypothesis 7 (H7). Employee Engagement positively affects Dynamic Marketing Engagement.

The influence of Customer Engagement on Dynamic Marketing Engagement shows a result of an estimated value equal to 0.197, value of C.R. equal to 2.286 > 2.0, and probability value 0.022 < 0.05. It can be concluded statistically that Employee Engagement variables proved to have a positive effect on Dynamic Marketing Engagement. These results are the same as those developed by Saxena and Srivastava [

58], but in contrast to the findings of Román and Rodríguez [

59], that the effect of technology used as a result of the salesperson’s performance is entirely mediated by qualified skills of salespeople and customer sales. Likewise, the results of Tsai’s [

60] study found that empowered employees had a direct impact on the commercialization performance mediated by dynamic marketing capabilities.

Hypothesis 8 (H8). Supply Chain Engagement positively affects Dynamic Marketing Engagement.

The influence of Supply Chain Engagement on Dynamic Marketing Engagement shows a result of an estimated value equal to 0.224, value of C.R. equal to 2.336 > 2.0, and probability value 0.020 < 0.05. It can be concluded statistically that the variable of Supply Chain Engagement proved to have a positive effect on Dynamic Marketing Engagement. These results are the same as those developed by Chang [

61], and Lee and Rha [

62] provide an explanation for companies and the supply chain to understand the impact of different conditions and define scenarios for applying varied market situations. Similarly, the view of Chiu and Kremer [

63], which suggests the scenario of supply chain centralization benefits the time performance of supply chain networks, while supply chain centralized scenarios show superiority to cost performance. Unlike Day, Lichtenstein, and Samouel [

64], routines—results of supply management capabilities formed from a consistently internal set of routines—were significantly related to financial performance mediated by operational performance.

Hypothesis 9 (H9). Dynamic Marketing Engagement positively affects Business Performance.

The influence of Dynamic Marketing Engagement on Business Performance shows an estimated value of 0.158, a value of C.R. of 2.020 > 2.0, and a probability value of 0.043 < 0.05. It can be concluded statistically that the Dynamic Marketing Engagement variable proved to have a positive effect on Business Performance. These results are the same as those developed by Wilden and Gudergan [

65], Swoboda and Olejnik [

66], and Zhang, Xue, and Dhaliwal [

67], who argue that IT-based static value judgments are critical for a company to achieve success and build relationships, and use electronics to interact with customers, suppliers, and other partners in the supply chain to offer new opportunities in developing dynamic capabilities with joint creation.

4. Discussion

The testing of the role of supply chain constraints as mediators bridging the variables of customer engagement and employee engagement to dynamic marketing attachments is essential to provide answers to significant gaps in marketing function roles [

8]. According to Suhardi [

68], a variable is said to be a mediator because it plays a role to influence the change of independent variables (independent variable) to other variables (response variable, dependent variable). Meanwhile, according to Baron and Kenny [

69], a variable is called a mediator if the variable affects the relationship between predictor (independent) and criterion (dependent) variables. Ghozali [

70] argues that the determination of intervening variables depends on their theoretical form. In this study, the theoretical model of the supply chain supplier variable becomes the mediator variable and for testing, the Sobel test is done to assess the significance of direct or mediation influence in the structural equation model [

71]. The Sobel test calculation results show that the role of the supply chain variable has less role to play between the customer engagement variable and dynamic marketing engagement, where the value Z = 1.863 < 1.98 and the

p-value is 0.062, above the 0.05 significance. With these results it can be stated that the supply chain engagement variable has not been able to mediate between customer engagement variables with dynamic marketing engagement. While the role of the supply chain variable is significant to be the mediator between the employee engagement variable and dynamic marketing engagement, where the value of Z = 2.055 > 1.98 and the

p-value of 0.039 is under the 0.05 significance. With this result it can be stated that the supply chain engagement variable can be a mediator between the employee engagement variable and dynamic marketing engagement.

The results of direct influence calculations show that the supply chain dependency variable (0.240) has a greater direct impact than employee engagement (0.214) and customer engagement (0.186) to dynamic marketing engagement. The result of the indirect effect calculation shows that the market knowledge variable (0.289) has a larger indirect effect than employee engagement (0.090) and customer engagement (0.062) to dynamic marketing engagement. Meanwhile, for business performance improvement, the indirect effect of employee engagement (0.051) is greater than market knowledge (0.048), customer engagement (0.041), and supply chain engagement (0.040). Additionally, the result of the calculation of total influence shows the employee engagement variable (0.304) has greater total influence than the engagement of market knowledge (0.289), customer engagement (0.248), and supply chain engagement (0.240) to dynamic marketing engagement. Meanwhile, for business performance improvement, the total effect of dynamic marketing engagement (0.166) is greater than employee engagement (0.051), market knowledge (0.048), customer engagement (0.041), and supply chain engagement (0.040).

The main purpose of this research was to build basic and empirical theoretical models in connecting the research gap between dynamic capability and actors’ engagement to business performance as embodied in the new concept of dynamic marketing engagement.

Theoretically, dynamic marketing engagement is a new concept through a process of decline from the concept of dynamic marketing capabilities and the concept of engagement associated with competitive advantage and sustainability competitiveness. The basic foundation of novelty is based on the incorporation of dynamic capabilities and marketing capabilities, while the process involves the role of employees, customers, and the supply chain as the multi-actors’ engagement to enter and play the role of marketing function in two non-digital and market interconnections. Theoretical concepts are derived from two combinations of theoretical views; first, the dynamic capability theory (DC) concept of Teece, Pisano, and Shuen [

72] and the emergence of a new paradigm called dynamic marketing capabilities (DMCs), which Barrales-Molina et al. [

8] uncovered. The emergence of the term DMCs poses significant problems to the role of the marketing function that requires the collaboration of marketing and operations. Second; development of engagement theory proposed by Kumar and Pansari [

14] for competitive excellence through engagement still requires re-measurement of the role of employee and customer engagement to performance, and the last is the phenomenon of the business of the emergence of social media as a marketing tool in the online marketplace.

Based on the above description, theoretically the views above have a critical space that requires a new concept to answer those needs. According to Barney, Jr, and Wright [

73], one of the implications of maturity of a critically stated theory lies in the moment followed by revitalization or decline. Thus, it can be concluded that the concept of dynamic marketing engagement as a novelty has qualified. Empirically, the research gap used in building the concept of dynamic marketing engagement is based on Dietmar et al.’s [

25] studies, which suggest that product-related export/service capabilities, partner relationship capabilities, and relationship process capabilities can replace resource shortages. This is in contrast to Park and Kim’s [

26] research, which explains that this type of strategy and market maturity affects the level of dynamic capability but has no relationship with dynamic ability levels. Meanwhile, Wilhelm et al. [

30] stated that dynamic capabilities have different performance effects in dynamic environments.

The empirical results of the concept of dynamic marketing engagement through nine hypothetical pathways proved significant to business performance. Interpretation of SEM analysis results through SPSS.AMOS 22 on direct, indirect, and total influence suggests that dynamic marketing incremental variables play a greater role in improving business performance. In addition, to run the concept of a dynamic marketing engagement strategy that is directly more influenced by supply chain engagement and indirectly influenced by market knowledge and totally influenced by employee engagement.

5. Conclusions

The research issue of “how to build a marketing strategy for SMEs in an offline system with a dynamic engagement strategy to improve business performance” refers to some contradictions. First, to answer the role of marketing functions on dynamic capabilities in facilitating service logic; second, the relationship of market knowledge, the engagement of actors, and business performance; third, the phenomenon of business marketing in the digital system. Referring to the research problem that has been formulated, it can be concluded based on the results of the hypothesis that first, dynamic ability can answer the role of the marketing function in business operations through supply chain engagement and facilitate service logic through customer and employee engagement to dynamic marketing engagement. Second, the relationship of market knowledge to the engagement of actors (customers, employees, supply chains) positively impacts business performance through dynamic marketing engagement. Third, the phenomenon of SME marketing business in the digital system has proven positive that using digital technology can increase sales. Thus, it can be expressed that dynamic marketing engagement strategy can improve business performance of SMEs. To run a dynamic marketing engagement strategy requires direct collaboration with the supply chain, has strong market knowledge, and total employee roles in understanding the customer’s desire to achieve sustainable competitive advantage.

The propositions developed in this study are based on the dynamic ability theory of management innovation innovated by Teece et al. [

72] as the dynamic marketing capabilities (DMCs) term of Barrales-Molina et al. [

8] and the service logic theoretical views expressed by Vargo and Lusch [

74] contained in the research of Kumar and Pansari [

14]. The dynamic capability’s view explains that dynamic capability is a company’s ability to integrate, build, and configure internal and external competencies to cope with rapidly changing environments. Meanwhile, the service-dominant logic view (S-D Logic) suggests service is a fundamental goal of economic activity and marketing. The theoretical contribution in the study of marketing management through propositions developed is that, firstly, dynamic marketing capability proved positive to the concept of dynamic marketing engagement. Secondly, the multi-actor engagement proved positive against the concept of dynamic marketing engagement. Thirdly, dynamic marketing engagement proved positive for business performance.

Based on the conclusion of the research problem and the results of the hypotheses, it can be concluded that “dynamic marketing capabilities and multi-actor involvement as a competitive firm strategy of the company on the concept of dynamic marketing engagement proved positively to improve the company’s business performance”. The findings are in line with Hou and Chien [

2], exploring the impact of market knowledge management competencies on performance through “dynamic capabilities”. The findings also addressed the problem of dynamic ability in marketing perspectives through the integration of the supply chain into the multi-actor attachment, which Barrales-Molina et al. [

8] argued was one of the significant problems with the role of marketing functions in the development of dynamic capabilities. With the integration of the supply chain into the concept of attachment, the findings answer Chandler & Lusch’s [

15] statement about the need to explore attachments not only as customer engagement, but also the actor’s other acumen from suppliers, manufacturers, retailers, and providers. The findings are also in line with Kumar and Pansari [

14], who find the level of engagement can be improved by identifying current levels of internal (employee) and external (customer) engagement and applying to relevant strategies.

The findings also dispose of the multi-actor engagement in line with the definition of actors’ attitudes defined by Storbacka et al. [

24], as the same disposition with actors for attachment, and activity of engagement in the process of interactive integration of resources within the service ecosystem. The novelty findings of the dynamic marketing engagement concept as a management innovation strategy in marketing service activities for sustainable competitive advantage in improving the performance of SME’s business is in accordance with the theory of dynamic capability and service logic that is in line with Karagouni and Protogerou’s [

21] opinion that dynamic capability theory facilitates logic service.

The limitations of this study related to the process and the results of the study are described as follows: (1) The relationship between the variables built in the empirical model still yields a marginal relationship so it is necessary to re-examine the indicators that affect the significance and the fit of the model; likewise, with research samples that limit the generalization of the study so that it needs to be differentiated and added. (2) The concept of dynamic marketing engagement still leaves a difference where Park and Kim’s [

26] (dated) discovery finds that market strategy and maturity from customers and technology has no relationship with dynamic levels. However, it is in line with the findings of Anabel Fernández-Mesa et al. [

27], which suggest that corporate innovation is necessary in establishing relationships in competitive markets to achieve higher performance [

29]. Additionally, Wilhelm et al.’s [

30] research finds dynamic capability in a high dynamic environment leads to higher efficiency of operating routines. The findings are also consistent with the findings of Alfalla-Luque et al. [

55], in that the relationship between employee commitment and operational performance is fully mediated by supply chain integration.