Study of the Thyroid Profile of Patients with Alopecia

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Thyroid Hormones (THs) and Hair Follicles

1.2. Alopecia: From General Considerations to Thyroid Connections

1.3. Aim

2. Methods

3. Different Types of Alopecia: The Link to the Thyroid Profile

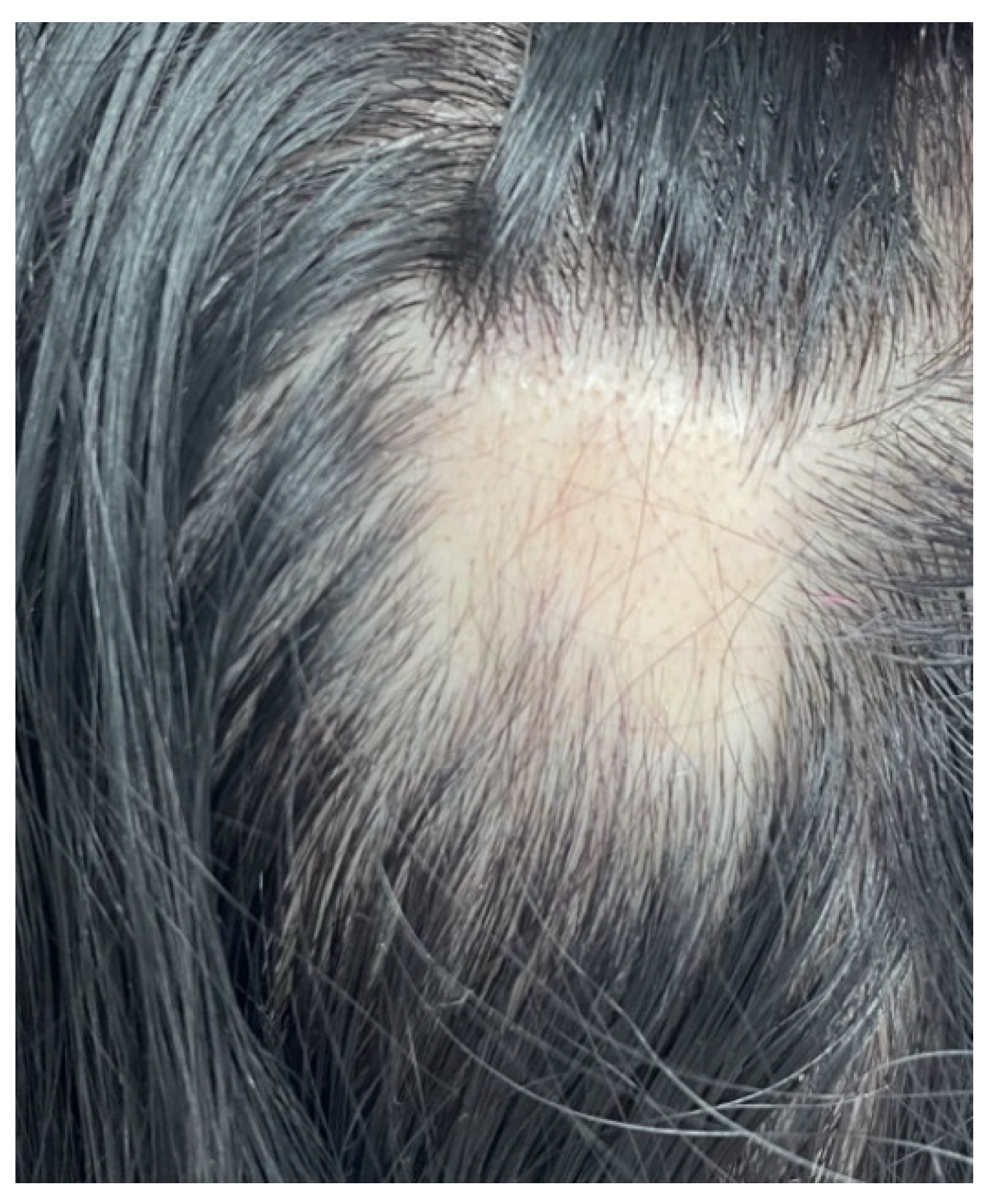

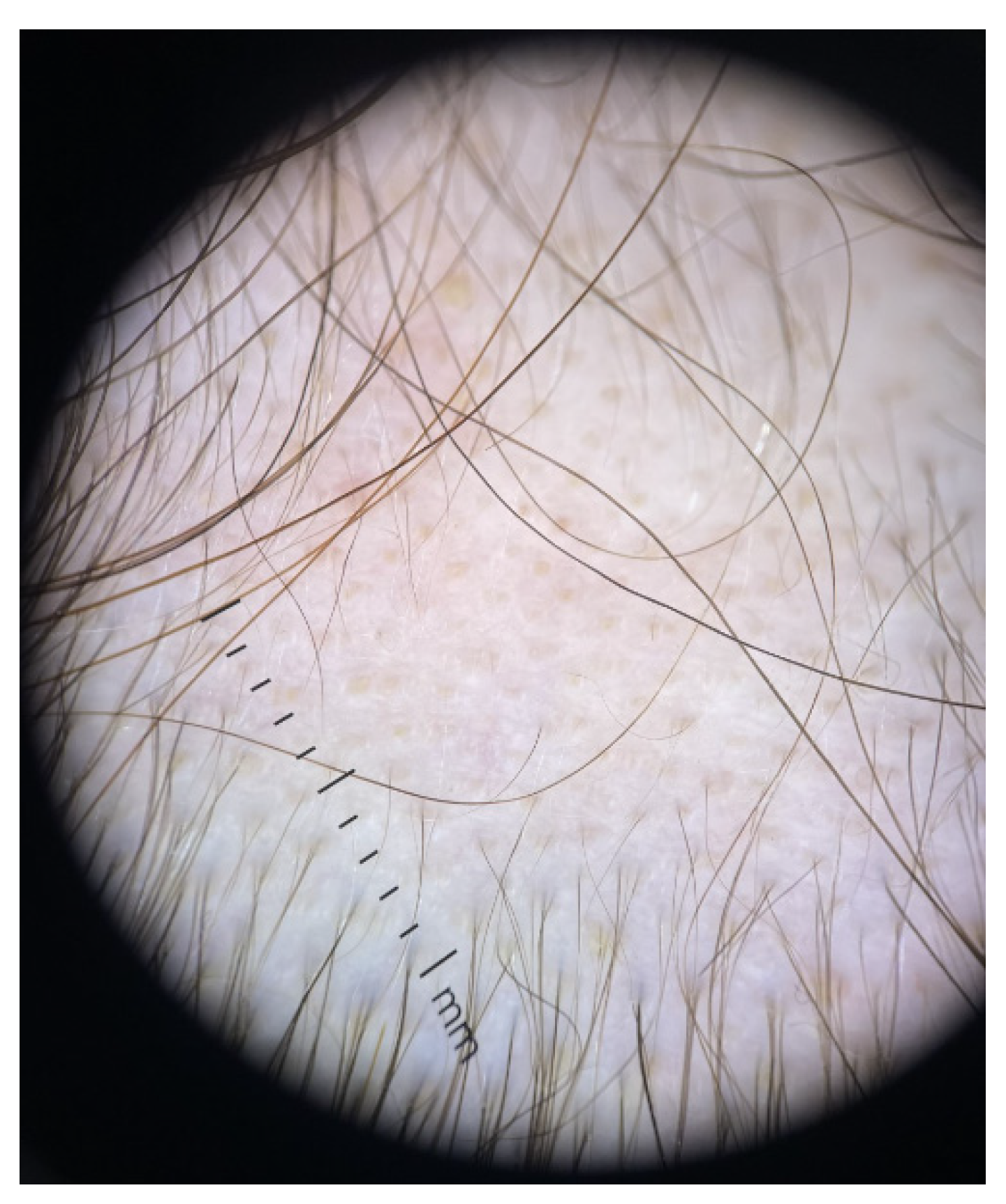

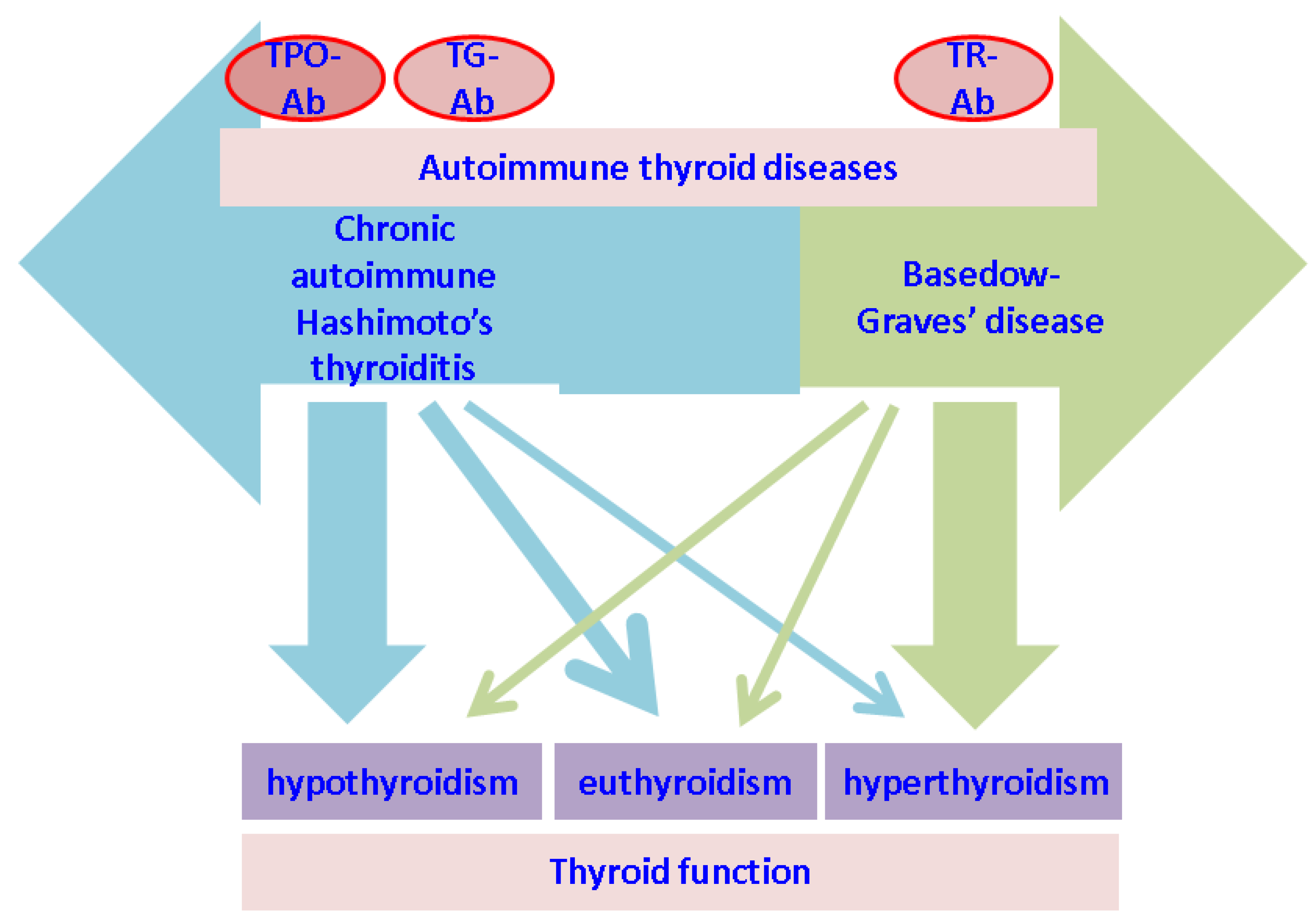

3.1. Alopecia Areata (AA)

3.2. Androgenic Alopecia

3.3. Male Pattern Alopecia

3.4. Telogen Effluvium (TE)

3.5. Alopecia Neoplastica (AN)

3.6. Frontal Fibrosing Alopecia (FFA)

3.7. Lichen Planopilaris (LPP)

4. Discussion

4.1. From Alopecia to Thyroid Anomalies

4.2. Cicatricial Alopecia and Thyroid Status

4.3. Polyglandular Autoimmune Syndrome

4.4. Endocrine Perspective of Alopecia

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AA | alopecia areata |

| Ab | antibodies |

| AN | alopecia neoplastica |

| ATD | autoimmune thyroid disease |

| APS-1 | autoimmune poly-endocrine syndrome type 1 |

| CI | Confidence Interval |

| FFA | frontal fibrosing alopecia |

| FPHL | female pattern hair loss |

| HLA | Human Leukocyte Antigen |

| LPP | lichen planopilaris |

| IFN | interferon |

| IQR | interval inter-quartile |

| OR | Odds Ratio |

| NKG | Natural Killer Group |

| NOS | No other specified |

| MPA | male pattern alopecia |

| PPAR | peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor |

| SAVI | STING-associated vasculopathy with onset in infancy |

| TE | telogen effluvium |

| TH | thyroid hormones |

| TG-Ab | anti-thyroglobulin antibodies |

| TR-Ab | TSH-receptor antibody |

| TPO-Ab | antithyroperoxidase antibodies |

| TR | thyroid hormones receptor |

| T3 | Triiodothyronine |

| T4 | thyroxine |

| TSH | Thyroid Stimulating Hormone |

References

- Mancino, G.; Miro, C.; Di Cicco, E.; Dentice, M. Thyroid hormone action in epidermal development and homeostasis and its implications in the pathophysiology of the skin. J. Endocrinol. Investig. 2021, 44, 1571–1579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kasumagić-Halilović, E. Thyroid autoimmunity in patients with alopecia areata. Acta Derm. Croat. 2008, 16, 123–125. [Google Scholar]

- Contreras-Jurado, C.; Garcia-Serrano, L.; Gomez-Ferreria, M.; Costa, C.; Paramio, J.M.; Aranda, A. The thyroid hormone receptors as modulators of skin proliferation and inflammation. J. Biol. Chem. 2011, 286, 24079–24088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Contreras-Jurado, C.; Lorz, C.; Garcia-Serrano, L.; Paramio, J.M.; Aranda, A. Thyroid hormone signalling controls hair follicle stem cell function. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2015, 26, 1263–1272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paus, R.; Bertolini, M. The role of hair follicle immune privilege collapse in alopecia areata: Status and perspectives. J. Investig. Derm. Symp. Proc. 2013, 16, S25–S27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heymann, W.R. Adjusting the Screen Door: Developing a Rational Approach to Assessing for Thyroid Disease in Patients with Alopecia Areata. Skinmed 2019, 17, 185–186. [Google Scholar]

- Fröhlich, E.; Wahl, R. Thyroid Autoimmunity: Role of Anti-thyroid Antibodies in Thyroid and Extra-Thyroidal Diseases. Front. Immunol. 2017, 8, 521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyritsi, E.M.; Kanaka-Gantenbein, C. Autoimmune Thyroid Disease in Specific Genetic Syndromes in Childhood and Adolescence. Front. Endocrinol. 2020, 11, 543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiromatsu, Y.; Satoh, H.; Amino, N. Hashimoto’s thyroiditis: History and future outlook. Hormones 2013, 12, 12–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadeler, E. Leonardo Da Vinci’s Archival of the Dermatologic Condition. J. Med. Humanit. 2021, 42, 795–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Domper, L.; Ballesteros-Redondo, M.; Vañó-Galván, S. Trichoscopy: An Update. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2022, S0001-7310(22)01064-X. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keskitalo, S.; Haapaniemi, E.; Einarsdottir, E.; Rajamäki, K.; Heikkilä, H.; Ilander, M.; Pöyhönen, M.; Morgunova, E.; Hokynar, K.; Lagström, S.; et al. Novel TMEM173 Mutation and the Role of Disease Modifying Alleles. Front. Immunol. 2019, 10, 2770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paolino, G.; Pampena, R.; Grassi, S.; Mercuri, S.R.; Cardone, M.; Corsetti, P.; Moliterni, E.; Muscianese, M.; Rossi, A.; Frascione, P.; et al. Alopecia neoplastica as a sign of visceral malignancies: A systematic review. J. Eur. Acad. Derm. Venereol. 2019, 33, 1020–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, T.Y.; Lee, J.H.; Noh, T.K.; Choi, M.W.; Yun, J.S.; Lee, K.H.; Bae, J.M. Alopecia areata and overt thyroid diseases: A nationwide population-based study. J. Dermatol. 2018, 45, 1411–1417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naik, P.P.; Farrukh, S.N. Association between alopecia areata and thyroid dysfunction. Postgrad. Med. 2021, 133, 895–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, S.; Lee, H.; Lee, C.H.; Lee, W.S. Comorbidities in alopecia areata: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2019, 80, 466–477.e16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kinoshita-Ise, M.; Martinez-Cabriales, S.A.; Alhusayen, R. Chronological association between alopecia areata and autoimmune thyroid diseases: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Dermatol. 2019, 46, 702–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xin, C.; Sun, X.; Lu, L.; Yang, R.; Shan, L.; Wang, Y. Increased Incidence of Thyroid Disease in Patients with Alopecia Areata: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Dermatology 2020, 236, 251–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, Y.X.; Tai, Y.H.; Chang, Y.T.; Chen, T.J.; Chen, M.H. Bidirectional association between alopecia areata and thyroid diseases: A nationwide population-based cohort study. Arch. Derm. Res. 2021, 313, 339–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villasante Fricke, A.C.; Miteva, M. Epidemiology and burden of alopecia areata: A systematic review. Clin. Cosmet. Investig. Dermatol. 2015, 8, 397–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, R.; Conic, R.Z.; Bergfeld, W.; Mesinkovska, N.A. Prevalence of Comorbid Conditions and Sun-Induced Skin Cancers in Patients with Alopecia Areata. J. Investig. Derm. Symp. Proc. 2015, 17, 61–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lyakhovitsky, A.; Shemer, A.; Amichai, B. Increased prevalence of thyroid disorders in patients with new onset alopecia areata. Australas. J. Dermatol. 2015, 56, 103–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bertoli, M.J.; Sadoughifar, R.; Schwartz, R.A.; Lotti, T.M.; Janniger, C.K. Female pattern hair loss: A comprehensive review. Derm. Ther. 2020, 33, e14055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramos, P.M.; Miot, H.A. Female Pattern Hair Loss: A clinical and pathophysiological review. Bras. Dermatol. 2015, 90, 529–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaikittisilpa, S.; Rattanasirisin, N.; Panchaprateep, R.; Orprayoon, N.; Phutrakul, P.; Suwan, A.; Jaisamrarn, U. Prevalence of female pattern hair loss in postmenopausal women: A cross-sectional study. Menopause 2022, 29, 415–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Famenini, S.; Slaught, C.; Duan, L.; Goh, C. Demographics of women with female pattern hair loss and the effectiveness of spironolactone therapy. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2015, 73, 705–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, S.M.; Son, S.W.; Lee, K.G.; Kim, S.H.; Lee, S.K.; Cho, E.R.; Kim, I.H.; Shin, C. Gender-specific association of androgenetic alopecia with metabolic syndrome in a middle-aged Korean population. Br. J. Dermatol. 2012, 167, 306–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel Fattah, N.S.; Darwish, Y.W. Androgenetic alopecia and insulin resistance: Are they truly associated? Int. J. Dermatol. 2011, 50, 417–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vincent, M.; Yogiraj, K. A Descriptive Study of Alopecia Patterns and their Relation to Thyroid Dysfunction. Int. J. Trichology. 2013, 5, 57–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krysiak, R.; Kowalcze, K.; Marek, B.; Okopień, B. The impact of levothyroxine on thyroid autoimmunity and hypothalamic-pituitary-thyroid axis activity in men with autoimmune hypothyroidism and early-onset androgenetic alopecia. Endokrynol. Pol. 2021, 72, 498–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rebora, A. Telogen effluvium revisited. G Ital. Derm. Venereol. 2014, 149, 47–54. [Google Scholar]

- Paus, R.; Ramot, Y.; Kirsner, R.S.; Tomic-Canic, M. Topical L-thyroxine: The Cinderella among hormones waiting to dance on the floor of dermatological therapy? Exp. Dermatol. 2020, 29, 910–923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yorulmaz, A.; Hayran, Y.; Ozdemir, A.K.; Sen, O.; Genc, I.; Gur Aksoy, G.; Yalcin, B. Telogen effluvium in daily practice: Patient characteristics, laboratory parameters, and treatment modalities of 3028 patients with telogen effluvium. J. Cosmet. Dermatol. 2021, 21, 2610–2617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deo, K.; Sharma, Y.K.; Wadhokar, M.; Tyagi, N. Clinicoepidemiological Observational Study of Acquired Alopecias in Females Correlating with Anemia and Thyroid Function. Derm. Res. Pract. 2016, 2016, 6279108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chansky, P.; Micheletti, R.G. Alopecia neoplastica. BMJ Case Rep. 2017, 2017, bcr2017220215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flanagan, K.E.; Burns, L.J.; Pathoulas, J.T.; Walker, C.J.; Pupo Wiss, I.; Cornejo, K.M.; Senna, M.M. Primary Alopecia Neoplastica: A Novel Case Report and Literature Review. Ski. Appendage Disord. 2021, 7, 499–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skafida, E.; Triantafyllopoulou, I.; Flessas, I.; Liontos, M.; Koutsoukos, K.; Zagouri, F.; Dimopoulos, A.M. Secondary Alopecia Neoplastica Mimicking Alopecia Areata following Breast Cancer. Case Rep. Oncol. 2020, 13, 627–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos, P.M.; Anzai, A.; Duque-Estrada, B.; Farias, D.C.; Melo, D.F.; Mulinari-Brenner, F.; Pinto, G.M.; Abraham, L.S.; Santos, L.D.N.; Pirmez, R.; et al. Risk factors for frontal fibrosing alopecia: A case-control study in a multiracial population. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2021, 84, 712–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valesky, E.M.; Maier, M.D.; Kippenberger, S.; Kaufmann, R.; Meissner, M. Frontal fibrosing alopecia—Review of recent case reports and case series in PubMed. J. Dtsch. Derm. Ges. 2018, 16, 992–999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valesky, E.M.; Maier, M.D.; Kaufmann, R.; Zöller, N.; Meissner, M. Single-center analysis of patients with frontal fibrosing alopecia: Evidence for hypothyroidism and a good quality of life. J. Int. Med. Res. 2019, 47, 653–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanti, V.; Constantinou, A.; Reygagne, P.; Vogt, A.; Kottner, J.; Blume-Peytavi, U. Frontal fibrosing alopecia: Demographic and clinical characteristics of 490 cases. J. Eur. Acad. Derm. Venereol. 2019, 33, 1976–1983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panchaprateep, R.; Ruxrungtham, P.; Chancheewa, B.; Asawanonda, P. Clinical characteristics, trichoscopy, histopathology and treatment outcomes of frontal fibrosing alopecia in an Asian population: A retro-prospective cohort study. J. Dermatol. 2020, 47, 1301–1311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aldoori, N.; Dobson, K.; Holden, C.R.; McDonagh, A.J.; Harries, M.; Messenger, A.G. Frontal fibrosing alopecia: Possible association with leave-on facial skin care products and sunscreens; a questionnaire study. Br. J. Dermatol. 2016, 175, 762–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tolkachjov, S.N.; Chaudhry, H.M.; Camilleri, M.J.; Torgerson, R.R. Frontal fibrosing alopecia among men: A clinicopathologic study of 7 cases. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2017, 77, 683–690.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atanaskova Mesinkovska, N.; Brankov, N.; Piliang, M.; Kyei, A.; Bergfeld, W.F. Association of lichen planopilaris with thyroid disease: A retrospective case-control study. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2014, 70, 889–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Larkin, S.C.; Cantwell, H.M.; Imhof, R.L.; Torgerson, R.R.; Tolkachjov, S.N. Lichen Planopilaris in Women: A Retrospective Review of 232 Women Seen at Mayo Clinic From 1992 to 2016. Mayo Clin. Proc. 2020, 95, 1684–1695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cantwell, H.M.; Wieland, C.N.; Proffer, S.L.; Imhof, R.L.; Torgerson, R.R.; Tolkachjov, S.N. Lichen planopilaris in men: A retrospective clinicopathologic study of 19 patients. Int. J. Dermatol. 2021, 60, 482–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brankov, N.; Conic, R.Z.; Atanaskova-Mesinkovska, N.; Piliang, M.; Bergfeld, W.F. Comorbid conditions in lichen planopilaris: A retrospective data analysis of 334 patients. Int. J. Womens Dermatol. 2018, 4, 180–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babahosseini, H.; Tavakolpour, S.; Mahmoudi, H.; Balighi, K.; Teimourpour, A.; Ghodsi, S.Z.; Abedini, R.; Ghandi, N.; Lajevardi, V.; Kiani, A.; et al. Lichen planopilaris: Retrospective study on the characteristics and treatment of 291 patients. J. Dermatol. Treat. 2019, 30, 598–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manatis-Lornell, A.; Okhovat, J.P.; Marks, D.H.; Hagigeorges, D.; Senna, M.M. Comorbidities in patients with lichen planopilaris: A retrospective case-control study. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2020, 83, 205–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marahatta, S.; Agrawal, S.; Mehata, K.D. Alopecia Areata and Thyroid Dysfunction Association—A Study from Eastern Nepal. Kathmandu Univ. Med. J. 2018, 16, 161–165. [Google Scholar]

- Muntyanu, A.; Gabrielli, S.; Donovan, J.; Gooderham, M.; Guenther, L.; Hanna, S.; Lynde, C.; Prajapati, V.H.; Wiseman, M.; Netchiporouk, E. The burden of alopecia areata: A scoping review focusing on quality of life, mental health and work productivity. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Lee, Y.B.; Kim, B.J.; Lee, W.S. Screening of thyroid function and autoantibodies in patients with alopecia areata: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2019, 80, 1410–1413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Orgiazzi, J. Thyroid autoimmunity. Presse Med. 2012, 41, e611–e625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilhar, A.; Keren, A.; Shemer, A.; d’Ovidio, R.; Ullmann, Y.; Paus, R. Autoimmune disease induction in a healthy human organ: A humanized mouse model of alopecia areata. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2013, 133, 844–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilhar, A.; Etzioni, A.; Paus, R. Alopecia areata. N Engl. J. Med. 2012, 366, 1515–1525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hordinsky, M.K. Overview of alopecia areata. J. Investig. Derm. Symp. Proc. 2013, 16, S13–S15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ito, T.; Hashizume, H.; Shimauchi, T.; Funakoshi, A.; Ito, N.; Fukamizu, H.; Takigawa, M.; Tokura, Y. CXCL10 produced from hair follicles induces Th1 and Tc1 cell infiltration in the acute phase of alopecia areata followed by sustained Tc1 accumulation in the chronic phase. J. Derm. Sci. 2013, 69, 140–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forstbauer, L.M.; Brockschmidt, F.F.; Moskvina, V.; Herold, C.; Redler, S.; Herzog, A.; Hillmer, A.M.; Meesters, C.; Heilmann, S.; Albert, F.; et al. Genome-wide pooling approach identifies SPATA5 as a new susceptibility locus for alopecia areata. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 2012, 20, 326–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seetharam, K.A. Alopecia areata: An update. Indian J. Derm. Venereol. Leprol. 2013, 79, 563–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malkud, S. Telogen Effluvium: A Review. J. Clin. Diagn. Res. 2015, 9, WE01–WE03. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grover, C.; Khurana, A. Telogen effluvium. Indian J. Derm. Venereol. Leprol. 2013, 79, 591–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guarrera, M. Additional methods for diagnosing alopecia and appraising their severity. G Ital. Derm. Venereol. 2014, 149, 93–102. [Google Scholar]

- Rebora, A. Telogen effluvium: A comprehensive review. Clin. Cosmet. Investig. Dermatol. 2019, 12, 583–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rebora, A.; Guarrera, M.; Baldari, M.; Vecchio, F. Distinguishing androgenetic alopecia from chronic telogen effluvium when associated in the same patient: A simple noninvasive method. Arch. Dermatol. 2005, 141, 1243–1245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guarrera, M.; Cardo, P.P.; Rebora, A. Assessing the reliability of the modified wash test. G Ital. Derm. Venereol. 2011, 146, 289–294. [Google Scholar]

- Porriño-Bustamante, M.L.; Fernández-Pugnaire, M.A.; Arias-Santiago, S. Frontal Fibrosing Alopecia: A Review. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 1805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stockmeier, M.; Kunte, C.; Sander, C.A.; Wolff, H. Frontale fibrosierende Kossard frontal fibrosing alopecia in a man. Hautarzt 2002, 53, 409–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vañó-Galván, S.; Molina-Ruiz, A.M.; Serrano-Falcón, C.; Arias-Santiago, S.; Rodrigues-Barata, A.R.; Garnacho-Saucedo, G.; Martorell-Calatayud, A.; Fernández-Crehuet, P.; Grimalt, R.; Aranegui, B.; et al. Frontal fibrosing alopecia: A multicenter review of 355 patients. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2014, 70, 670–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kossard, S.; Shiell, R.C. Frontal fibrosing alopecia developing after hair transplantation for androgenetic alopecia. Int. J. Dermatol. 2005, 44, 321–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porriño-Bustamante, M.L.; García-Lora, E.; Buendía-Eisman, A.; Arias-Santiago, S. Familial frontal fibrosing alopecia in two male families. Int. J. Dermatol. 2019, 58, e178–e180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faulkner, C.F.; Wilson, N.J.; Jones, S.K. Frontal fibrosing alopecia associated with cutaneous lichen planus in a premenopausal woman. Australas. J. Dermatol. 2002, 43, 65–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno-Ramírez, D.; Camacho Martínez, F. Frontal fibrosing alopecia: A survey in 16 patients. J. Eur. Acad. Derm. Venereol. 2005, 19, 700–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moreno-Ramírez, D.; Ferrándiz, L.; Camacho, F.M. Diagnostic and therapeutic assessment of frontal fibrosing alopecia]. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2007, 98, 594–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- MacDonald, A.; Clark, C.; Holmes, S. Frontal fibrosing alopecia: A review of 60 cases. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2012, 67, 955–961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, K.T.; Messenger, A.G. Frontal fibrosing alopecia: Clinical presentations and prognosis. Br. J. Dermatol. 2009, 160, 75–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suchonwanit, P.; Pakornphadungsit, K.; Leerunyakul, K.; Khunkhet, S.; Sriphojanart, T.; Rojhirunsakool, S. Frontal fibrosing alopecia in Asians: A retrospective clinical study. Int. J. Dermatol. 2020, 59, 184–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dlova, N.C.; Jordaan, H.F.; Skenjane, A.; Khoza, N.; Tosti, A. Frontal fibrosing alopecia: A clinical review of 20 black patients from South Africa. Br. J. Dermatol. 2013, 169, 939–941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miteva, M.; Whiting, D.; Harries, M.; Bernardes, A.; Tosti, A. Frontal fibrosing alopecia in black patients. Br. J. Dermatol. 2012, 167, 208–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ragusa, F.; Fallahi, P.; Elia, G.; Gonnella, D.; Paparo, S.R.; Giusti, C.; Churilov, L.P.; Ferrari, S.M.; Antonelli, A. Hashimotos’ thyroiditis: Epidemiology, pathogenesis, clinic and therapy. Best Pr. Res. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2019, 33, 101367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horesh, E.J.; Chéret, J.; Paus, R. Growth Hormone and the Human Hair Follicle. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 13205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samrao, A.; Chew, A.L.; Price, V. Frontal fibrosing alopecia: A clinical review of 36 patients. Br. J. Dermatol. 2010, 163, 1296–1300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alegre-Sánchez, A.; Saceda-Corralo, D.; Bernárdez, C.; Molina-Ruiz, A.M.; Arias-Santiago, S.; Vañó-Galván, S. Frontal fibrosing alopecia in male patients: A report of 12 cases. J. Eur. Acad. Derm. Venereol. 2017, 31, e112–e114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sato, M.; Saga, K.; Takahashi, H. Postmenopausal frontal fibrosing alopecia in a Japanese woman with Sjögren’s syndrome. J. Dermatol. 2008, 35, 729–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Inui, S.; Nakajima, T.; Shono, F.; Itami, S. Dermoscopic findings in frontal fibrosing alopecia: Report of four cases. Int. J. Dermatol. 2008, 47, 796–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakamura, M.; Tokura, Y. Expression of Snail1 in the fibrotic dermis of postmenopausal frontal fibrosing alopecia: Possible involvement of an epithelial-mesenchymal transition and a review of the Japanese patients. Br. J. Dermatol. 2010, 162, 1152–1154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harries, M.J.; Meyer, K.; Chaudhry, I.; EKloepper, J.; Poblet, E.; Griffiths, C.E.; Paus, R. Lichen planopilaris is characterized by immune privilege collapse of the hair follicle’s epithelial stem cell niche. J. Pathol. 2013, 231, 236–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katoulis, A.C.; Diamanti, K.; Damaskou, V.; Pouliakis, A.; Bozi, E.; Koufopoulos, N.; Rigopoulos, D.; Ioannides, D.; Panayiotides, I.G. Decreased melanocyte counts in the upper hair follicle in frontal fibrosing alopecia compared to lichen planopilaris: A retrospective histopathologic study. J. Eur. Acad. Derm. Venereol. 2021, 35, e343–e345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mobini, N.; Tam, S.; Kamino, H. Possible role of the bulge region in the pathogenesis of inflammatory scarring alopecia: Lichen planopilaris as the prototype. J. Cutan. Pathol. 2005, 32, 675–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harries, M.J.; Paus, R. Scarring alopecia and the PPAR-gamma connection. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2009, 129, 1066–1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katoulis, A.C.; Diamanti, K.; Sgouros, D.; Liakou, A.I.; Bozi, E.; Tzima, K.; Panayiotides, I.; Rigopoulos, D. Frontal fibrosing alopecia: Is the melanocyte of the upper hair follicle the antigenic target? Int. J. Dermatol. 2018, 57, e37–e38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, J.; Valdebran, M.; Bergfeld, W.; Conic, R.Z.; Piliang, M.; Atanaskova Mesinkovska, N. Hypopigmentation in frontal fibrosing alopecia. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2017, 76, 1184–1186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- King, A.D.; Lam, L.; Goh, C. Onset of frontal fibrosing alopecia during inhibition of Th1/17 Pathways with ustekinumab. Derm. Online J. 2019, 25, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanchard, P.G.; Festuccia, W.T.; Houde, V.P.; St-Pierre, P.; Brûlé, S.; Turcotte, V.; Côté, M.; Bellmann, K.; Marette, A.; Deshaies, Y. Major involvement of mTOR in the PPARγ-induced stimulation of adipose tissue lipid uptake and fat accretion. J. Lipid Res. 2012, 53, 1117–1125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karnik, P.; Tekeste, Z.; McCormick, T.S.; Gilliam, A.C.; Price, V.H.; Cooper, K.D.; Mirmirani, P. Hair follicle stem cell-specific PPAR gamma deletion causes scarring alopecia. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2009, 129, 1243–1257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sasannia, M.; Saki, N.; Aslani, F.S. Comparison of Serum Level of Sex Hormones in Patients with Frontal Fibrosing Alopecia with Control Group. Int. J. Trichology 2020, 12, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imhof, R.L.; Chaudhry, H.M.; Larkin, S.C.; Torgerson, R.R.; Tolkachjov, S.N. Frontal Fibrosing Alopecia in Women: The Mayo Clinic Experience With 148 Patients, 1992–2016. Mayo Clin. Proc. 2018, 93, 1581–1588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katoulis, A.C.; Diamanti, K.; Sgouros, D.; Liakou, A.I.; Alevizou, A.; Bozi, E.; Damaskou, V.; Panayiotides, I.; Rigopoulos, D. Frontal Fibrosing Alopecia and Vitiligo: Coexistence or True Association? Ski. Appendage Disord. 2017, 2, 152–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandru, F.; Carsote, M.; Albu, S.E.; Dumitrascu, M.C.; Valea, A. Vitiligo and chronic autoimmune thyroiditis. J. Med. Life 2021, 14, 127–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, J.; Choi, J.W. Primary cicatricial alopecia in a single-race Asian population: A 10-year nationwide population-based study in South Korea. J. Dermatol. 2018, 45, 1306–1311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bjørklund, G.; Pivin, M.; Hangan, T.; Yurkovskaya, O.; Pivina, L. Autoimmune polyendocrine syndrome type 1: Clinical manifestations, pathogenetic features, and management approach. Autoimmun. Rev. 2022, 21, 103135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hanai, S.; Ito, T.; Furuta, T.; Tokura, Y. Alopecia areata with autoimmune polyglandular syndrome type 3 showing type 1/Tc1 immunological inflammation. Eur. J. Dermatol. 2020, 30, 425–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neagu, N.; Morariu, S.H.; Grama, A. Alopecia Areata Universalis in the Onset of Autoimmune Polyendocrine Syndrome Type III C. Int. J. Trichology 2022, 14, 62–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silverberg, N. The genetics of pediatric cutaneous autoimmunity: The sister diseases vitiligo and alopecia areata. Clin. Dermatol. 2022, 40, 363–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lause, M.; Kamboj, A.; Fernandez Faith, E. Dermatologic manifestations of endocrine disorders. Transl. Pediatr 2017, 6, 300–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capo, A.; Amerio, P. Polyglandular autoimmune syndrome type III with a prevalence of cutaneous features. Clin. Exp. Dermatol. 2017, 42, 61–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garelli, S.; Dalla Costa, M.; Sabbadin, C.; Barollo, S.; Rubin, B.; Scarpa, R.; Masiero, S.; Fierabracci, A.; Bizzarri, C.; Crinò, A.; et al. Autoimmune polyendocrine syndrome type 1: An Italian survey on 158 patients. J. Endocrinol. Investig. 2021, 44, 2493–2510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campos-Alberto, E.; Hirose, T.; Napatalung, L.; Ohyama, M. Prevalence, comorbidities, and treatment patterns of Japanese patients with alopecia areata: A descriptive study using Japan medical data center claims database. J. Dermatol. 2022, 50, 37–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fertig, R.M.; Hu, S.; Maddy, A.J.; Balaban, A.; Aleid, N.; Aldahan, A.; Tosti, A. Medical comorbidities in patients with lichen planopilaris, a retrospective case-control study. Int. J. Dermatol. 2018, 57, 804–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trager, M.H.; Lavian, J.; Lee, E.Y.; Gary, D.; Jenkins, F.; Christiano, A.M.; Bordone, L.A. Medical comorbidities and sex distribution among patients with lichen planopilaris and frontal fibrosing alopecia: A retrospective cohort study. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2021, 84, 1686–1689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lugović-Mihić, L.; Krišto, M.; Špoljar, S.; Novak-Bilić, G.; Bešlić, I.; Vučić, M.; Šitum, M. Can Skin Be A Marker For Internal Malignancy? Evidence From Clinical Cases. Acta Clin. Croat. 2021, 60, 711–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mudraje, S.; Shetty, S.; Guruvare, S.; Kudva, R. Sertoli-Leydig cell ovarian tumour: A rare cause of virilisation and androgenic alopecia. BMJ Case Rep. 2022, 15, e249324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cussen, L.; McDonnell, T.; Bennett, G.; Thompson, C.J.; Sherlock, M.; O’Reilly, M.W. Approach to androgen excess in women: Clinical and biochemical insights. Clin. Endocrinol. 2022, 97, 174–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lie, C.; Liew, C.F.; Oon, H.H. Alopecia and the metabolic syndrome. Clin. Dermatol. 2018, 36, 54–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramanathan, B.; Murugan, J.; Velayutham, K. Pilot study on evaluation and determination of the prevalence of Polycystic Ovarian Syndrome (PCOS) associated gene markers in the South Indian population. Indian J. Endocrinol. Metab. 2021, 25, 551–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pivonello, R.; Isidori, A.M.; De Martino, M.C.; Newell-Price, J.; Biller, B.M.; Colao, A. Complications of Cushing’s syndrome: State of the art. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2016, 4, 611–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karakas, S.E.; Surampudi, P. New Biomarkers to Evaluate Hyperandrogenemic Women and Hypogonadal Men. Adv. Clin. Chem. 2018, 86, 71–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zubair, Z.; Kantamaneni, K.; Jalla, K.; Renzu, M.; Jena, R.; Jain, R.; Muralidharan, S.; Yanamala, V.L.; Alfonso, M. Prevalence of Low Serum Vitamin D Levels in Patients Presenting With Androgenetic Alopecia: A Review. Cureus 2021, 13, e20431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saini, K.; Mysore, V. Role of vitamin D in hair loss: A short review. J. Cosmet. Dermatol. 2021, 20, 3407–3414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feldman, D.; JMalloy, P. Mutations in the vitamin D receptor and hereditary vitamin D-resistant rickets. Bonekey Rep. 2014, 3, 510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damiani, G.; Conic, R.; Orlando, G.; Zampetti, A.; Marinello, E.; Piai, M.; Linder, M.D. Vitamin D in trichology: A comprehensive review of the role of vitamin D and its receptor in hair and scalp disorders. G. Ital. Derm. Venereol. 2020, 155, 190–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashad, A.F.; Elgamal, E.; Fouda, I. Intralesional vitamin D3 in treatment of alopecia areata: A randomized controlled clinical trial. J. Cosmet. Dermatol. 2022, 21, 4617–4622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cranwell, W.C.; Lai, V.W.; Photiou, L.; Meah, N.; Wall, D.; Rathnayake, D.; Joseph, S.; Chitreddy, V.; Gunatheesan, S.; Sindhu, K.; et al. Treatment of alopecia areata: An Australian expert consensus statement. Australas. J. Dermatol. 2019, 60, 163–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Payne, J.; Habet, K.A.; Pona, A.; Feldman, S.R. A Review of Topical Corticosteroid Foams. J. Drugs Dermatol. 2019, 18, 756–770. [Google Scholar]

| First Author (Reference) | Year of Publication | Type of Study | Studied Population | Type of Alopecia | Thyroid Involvement |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vincent [29] | 2013 | Prospective study | N = 176 patients with FPHL N1 = 1232 subjects (control group) | FPLH | Prevalence of thyroid dysfunction according to age groups:

|

| Atanaskova Mesinkovska [45] | 2014 | Retrospective, case-control study | N = 166 patients with LPP N1 = 81 subjects (control group) | LPP | Thyroid involvement: 34% versus 11% (control) Hypothyroidism: 29% versus 9% |

| Famenini [25] | 2015 | Prospective study | N = 64 patients with FPHL (age: 20–88 y) | FPHL | Hypothyroidism: 31.25% No correlation between FPHL severity and thyroid disease |

| Miller [21] | 2015 | Retrospective study | N = 584 patients with AA N1= 172 subjects (control group) | AA | Thyroid involvement: 18.80% OR 2.84; 95%CI 1.55–5.18; p = 0.0004 |

| Deo [34] | 2016 | Prospective study | N = 84 females with TE N1 = 135 females with non-TE alopecia (control group) (age: 15–60 y) | TE | Thyroid involvement: 17%, respective:

|

| Aldoori [43] | 2016 | Questionnaire-based study | N = 105 females with FFA (age: 42–79 y) N1 = 100 females (control group) | FFA | History of thyroid disease: 19% History of thyroid disease: 7% |

| Tolkachjov [44] | 2017 | Retrospective study | N = 7 males with FFA | FFA | None with thyroid involvement |

| Valesky [39] | 2018 | Meta-analysis | N = 932 patients with FFA (96.9% females) | FFA | Thyroid involvement: 31.4% |

| Brankov [48] | 2018 | Retrospective study | N = 334 patients with LLP N1 = 78 subjects with seborrheic dermatitis (control group) | LPP | Hashimoto’s thyroiditis: 6.3% versus 0%; p = 0.023 Hypothyroidism: 24.3% versus 12.8%; p = 0.028 |

| Valesky [40] | 2019 | Retrospective, single-centre study | N = 12 females with FFA | FFA | Hypothyroidism: 58% |

| Lee [16] | 2019 | Meta-analysis | n = 87 studies | AA | ATD prevalence: 13.9% OR 1.66; 95% CI 0.82–3.38 Thyroid dysfunction: 12.5% OR 4.36; 95% CI 1.19–15.99 respective: subclinical hyperthyroidism: 5.7% OR 5.55; 95% CI 1.73–17.85 subclinical hypothyroidism: 10.4% OR 19.61; 95% CI 4.07–94.41 |

| Kinoshita-Ise [17] | 2019 | Meta-analysis | N = 262,581 patients with AA N1 = 1,302,655 control subjects (AA free) | AA | Positive TPO-Ab: OR 3.58; 95% CI 1.96–6.53 Positive TG-Ab: OR 4.44; 95% CI 1.54–12.75 Risk of having both positive TPO-Ab and TG-Ab in the same subject: OR 2.32; 95% CI 1.08–4.98 Risk of having positive either of these antibodies in the same subject: OR 6.34; 95% CI 2.24–17.93 Positive TR-Ab: OR 60.90; 95% CI, 34.61–107.18 |

| Paolino [13] | 2019 | Meta-analysis | N = 123 patients with AN | AN | Thyroid cancer: 7.3% |

| Kanti [41] | 2019 | Prospective study | N = 490 patients with FFA (95% females) | FFA | Thyroid involvement: 33.8% Females with thyroid involvement: 35% Males with thyroid involvement: 13% |

| Babahosseini [49] | 2019 | Retrospective study | N = 291 patients with LPP (age: 11–73 y) | LPP | Hypothyroidism: 10.58% (females), and 0.98% (males) |

| Xin [18] | 2020 | Meta-analysis | N = 2850 patients with AA N1 = 4667 subjects (control group) | AA | Thyroid disease: OR 3.66; 95% CI 2.90–4.61 Positive Tg-Ab: OR 3.83; 95% CI 1.92–7.63 Positive TPO-Ab: OR 4.07; 95% CI 2.66–6.22 Positive TM-Ab: OR 3.05; 95% CI 1.99–4.67 Hyperthyroidism: OR 1.43; 95% CI 0.36–5.57 Hypothyroidism: OR 4.07; 95% CI 1.95–8.49 |

| Panchaprateep [42] | 2020 | Retroactive–prospective study | N = 51 females with FFA | FFA | Thyroid involvement: 15.7% |

| Larkin [46] | 2020 | Retrospective study | N = 232 females with LPP | LPP | Thyroid involvement: 30.1% Hypothyroidism: 23.3% |

| Manatis-Lornell [50] | 2020 | Retrospective study | N = 232 patients with LPP N1 = 192 subjects (control group) | LPP | Thyroid diseases (NOS): 28.4% versus 23.7% OR 1.28; 95% CI 0.83–1.98; p = 0.27 Thyroid nodules: 9.9% versus 11.3% OR 0.86; 95% CI 0.46–1.60; p = 0.63 Hypothyroidism: 20.7% versus 13.9% OR 1.61; 95% CI 0.96–2.70; p = 0.069 Hyperthyroidism: 1.7% versus 2.1% OR 0.83; 95% CI 0.21–3.38; p = 0.80 Goitre: 4.3% versus 6.7% OR 0.63; 95% CI 0.27–1.46; p = 0.28 Thyroiditis: 4.7% versus 4.1% OR 1.16; 95% CI 0.46–2.94; p = 0.76 Thyroid cancer: 1.3% versus 1.0% OR 1.26; 95% CI 0.21–7.60; p = 0.8 |

| Dai [19] | 2021 | Retrospective study | N = 5929 patients with AA N1 = 59,290 subjects (control group) | AA | Increased risk of developing all thyroid diseases, including: toxic nodular goitre: aHR 10.17; 95% CI 5.32–19.44 nontoxic nodular goitre: aHR 5.23; 95% CI 3.76–7.28 thyrotoxicosis: aHR 7.96; 95% CI 6.01–10.54 Graves’s disease: aHR 8.36; 95% CI 5.66–12.35 thyroiditis: aHR 4.04; 95% CI 2.12–7.73 Hashimoto’s thyroiditis: aHR 4.35; 95% CI 1.88–10.04 |

| Krysiak [30] | 2021 | Prospective study | N = 24 males (age: 18–40 y) with untreated autoimmune hypothyroidism and MPA N1= subjects (age: 18–40 y) with untreated autoimmune hypothyroidism without MPA (control group) | MPA |

TPO-Ab [IU/mL; mean (SD)]:

Tg-Ab [IU/mL; mean (SD)]:

Free T4 [pmol/L; mean (SD)]:

Free T3 [pmol/L; mean (SD)]:

|

| Yorulmaz [33] | 2021 | Retrospective study | N = 3028 patients (age: 20–37 y) with TE | TE | Normal thyroid function: 94.3% Hypothyroidism: 3.9% Hyperthyroidism: 1.8% |

| Cantwell [47] | 2021 | Retrospective study | N = 16 males with LPP (age: 15.3–77.9 y) | LPP | Thyroid involvement: 15.8% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Popa, A.; Carsote, M.; Cretoiu, D.; Dumitrascu, M.C.; Nistor, C.-E.; Sandru, F. Study of the Thyroid Profile of Patients with Alopecia. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 1115. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12031115

Popa A, Carsote M, Cretoiu D, Dumitrascu MC, Nistor C-E, Sandru F. Study of the Thyroid Profile of Patients with Alopecia. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2023; 12(3):1115. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12031115

Chicago/Turabian StylePopa, Adelina, Mara Carsote, Dragos Cretoiu, Mihai Cristian Dumitrascu, Claudiu-Eduard Nistor, and Florica Sandru. 2023. "Study of the Thyroid Profile of Patients with Alopecia" Journal of Clinical Medicine 12, no. 3: 1115. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12031115

APA StylePopa, A., Carsote, M., Cretoiu, D., Dumitrascu, M. C., Nistor, C.-E., & Sandru, F. (2023). Study of the Thyroid Profile of Patients with Alopecia. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 12(3), 1115. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12031115