Using Approximate Computing and Selective Hardening for the Reduction of Overheads in the Design of Radiation-Induced Fault-Tolerant Systems

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Background and Related Works

2.1. Radiation Effects and Soft Errors

2.2. Software-Based Fault Tolerance

2.3. Approximate Computing (AC)

- Bit width reduction: This technique is based on precision reduction (number of bits that would normally be used) in floating-point numbers. In this way, energy efficiency and performance can be improved by sacrificing accuracy in the results [24]. On the other hand, when using the highest precision available in a microprocessor, code execution could take more time, so energy consumption would increase. On the other hand, if the representation of the data to put into operation is done using a smaller number of bits, it could have a lower energy consumption by reducing the accuracy in the result.

- Float point to fixed point conversion: Following the same principle of the prior technique, a floating-point variable can be replaced by a fixed-point variable [25]. The computation of real data type operations using a fixed-point number representation could be executed faster than operations using a floating point representation. For instance, this technique could be used for the computation of arithmetical operations in systems that lack a floating point unit (FPU), such as small microcontrollers.

- Code perforation: This technique identifies sections of code that can be discarded, without greatly affecting the results, to reduce computational costs. An example is to reduce the number of iterations in a loop, i.e., loop perforation [26,27]. This is a technique that transforms a loop to execute a subset of iterations of the original loop. By executing fewer iterations, the perforated loop will have a shorter execution time. Nevertheless, reducing iterations in a loop changes the result obtained with the original loop. Sometimes that difference may not be significant, but in other cases, the percentage of error between the results can be considerable, so the designer must establish a trade-off between accuracy of results and execution time.

- Synchronization elision: In multi-core systems, one of the most time-consuming tasks is synchronization. This technique implies a relaxing synchronization in parallel applications to reduce the associated costs [28]. Traditional relaxing synchronization techniques are based on the identification of scenarios where synchronization is not necessary. In contrast, this new technique takes advantage of the possibility of reducing the accuracy in the result without having a great impact on the behavior of the application. In this way, the synchronization is relaxed to improve performance at the expense of inexact results.

2.4. Fault Tolerance with Approximate Computing Techniques

3. Proposed Method

3.1. Approximation stage

3.2. Selective Hardening Stage

3.3. Validation Stage

- SDCs (silent data corruption): When the program completes its execution with erroneous output results.

- unACEs (unnecessary for architecturally correct execution): When the program obtains the expected results.

- Hangs: For abnormal terminations of the program or infinite loops.

4. Case Study

4.1. Experimental Setup

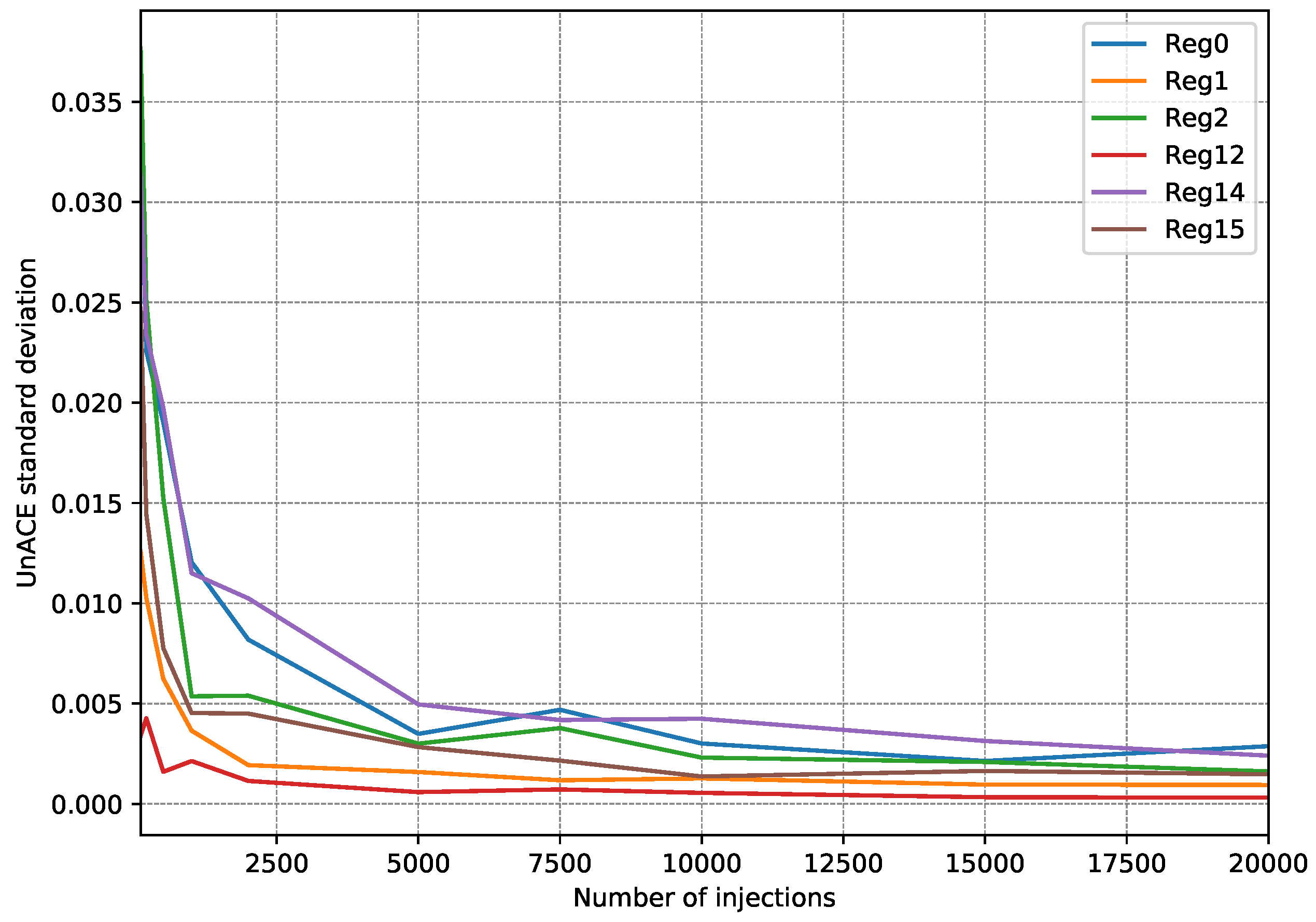

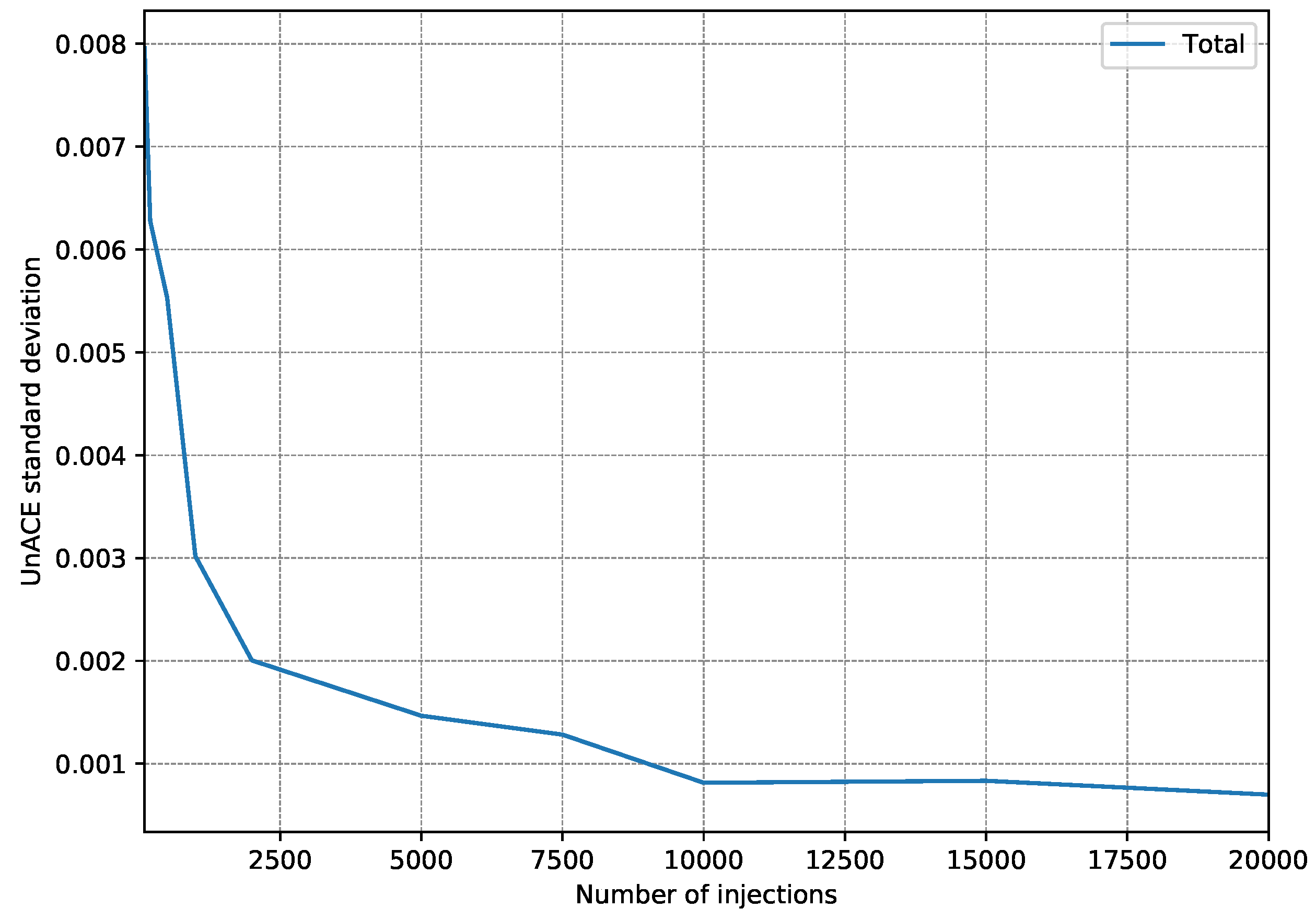

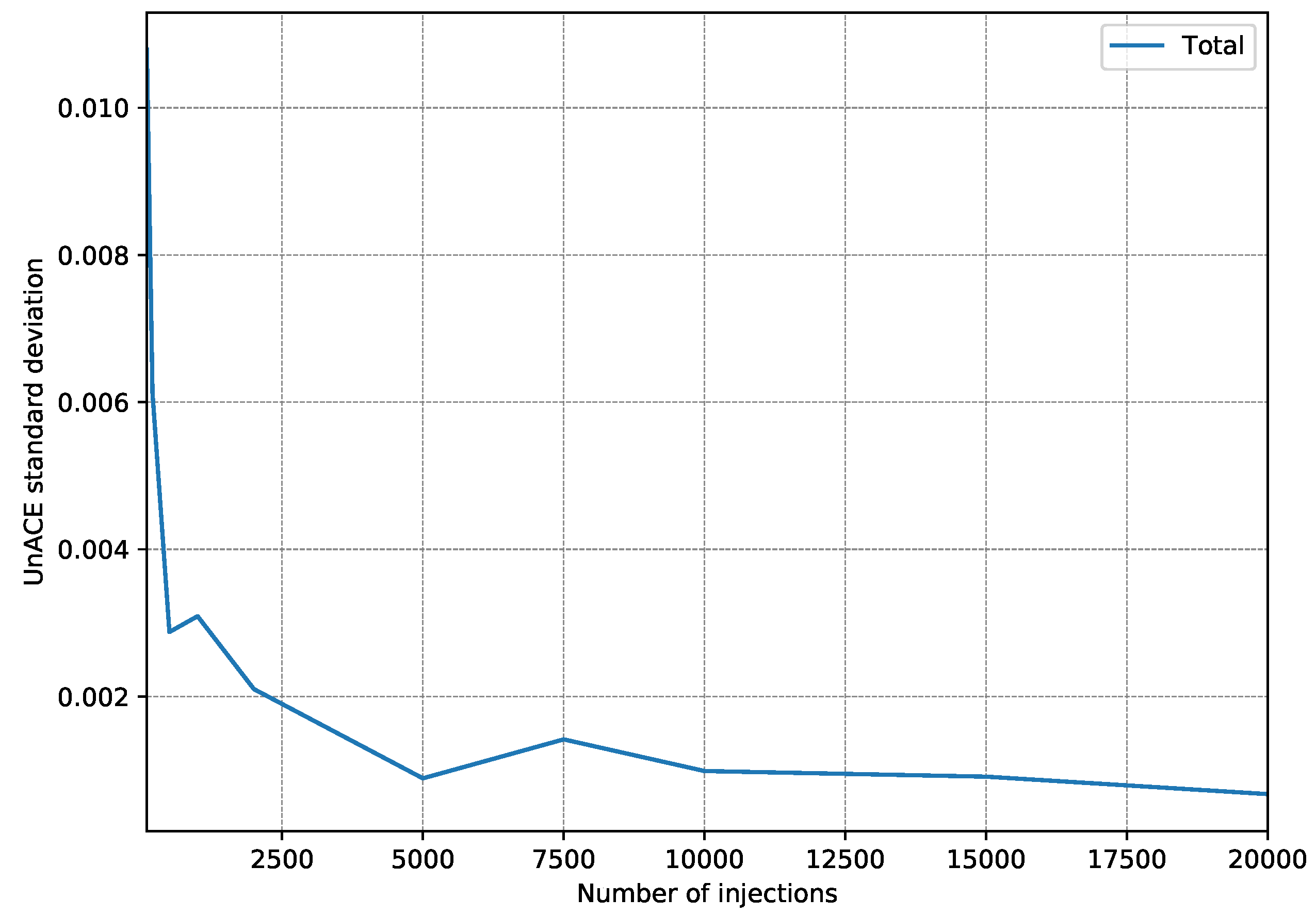

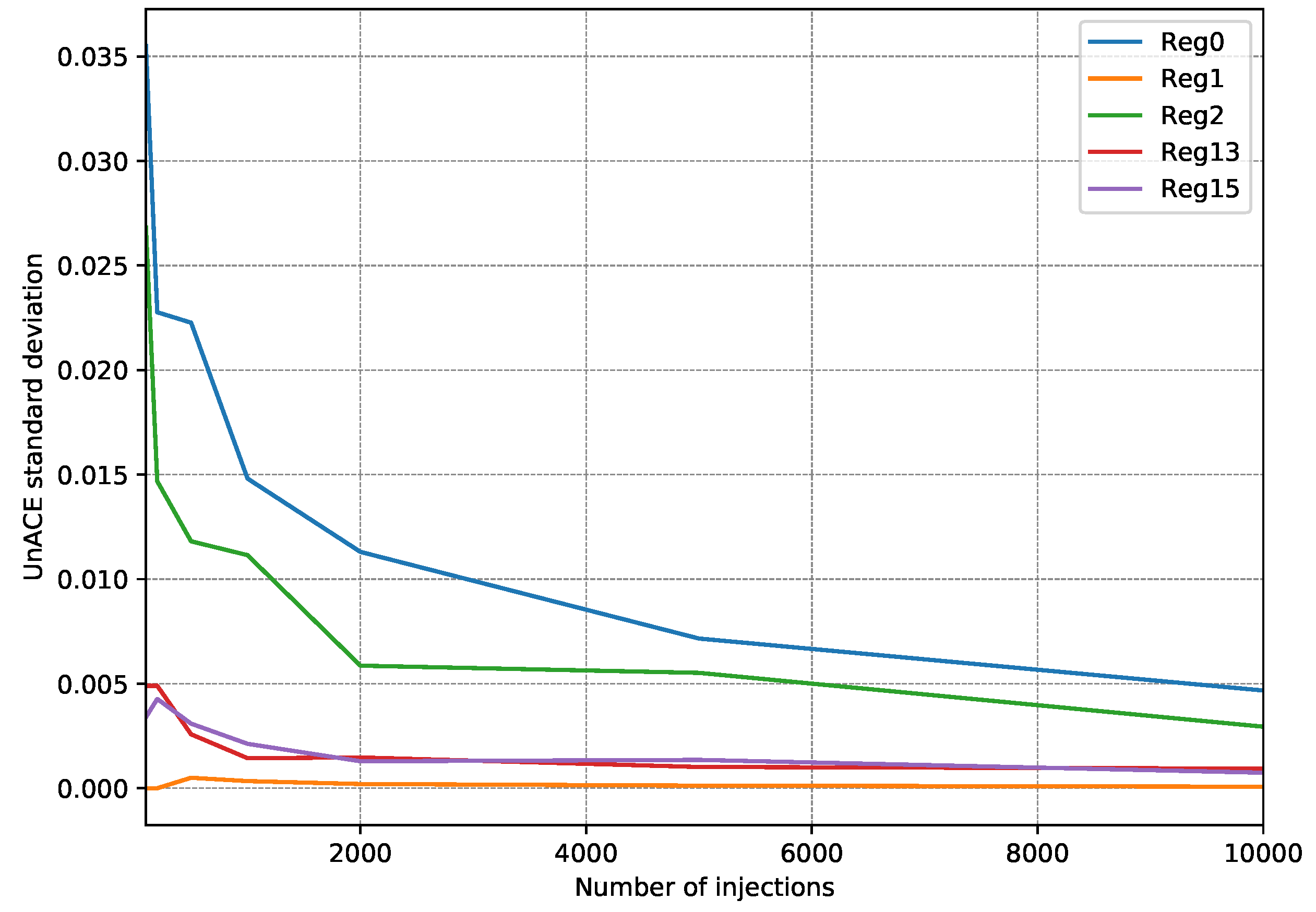

4.2. Fault Injection Campaigns

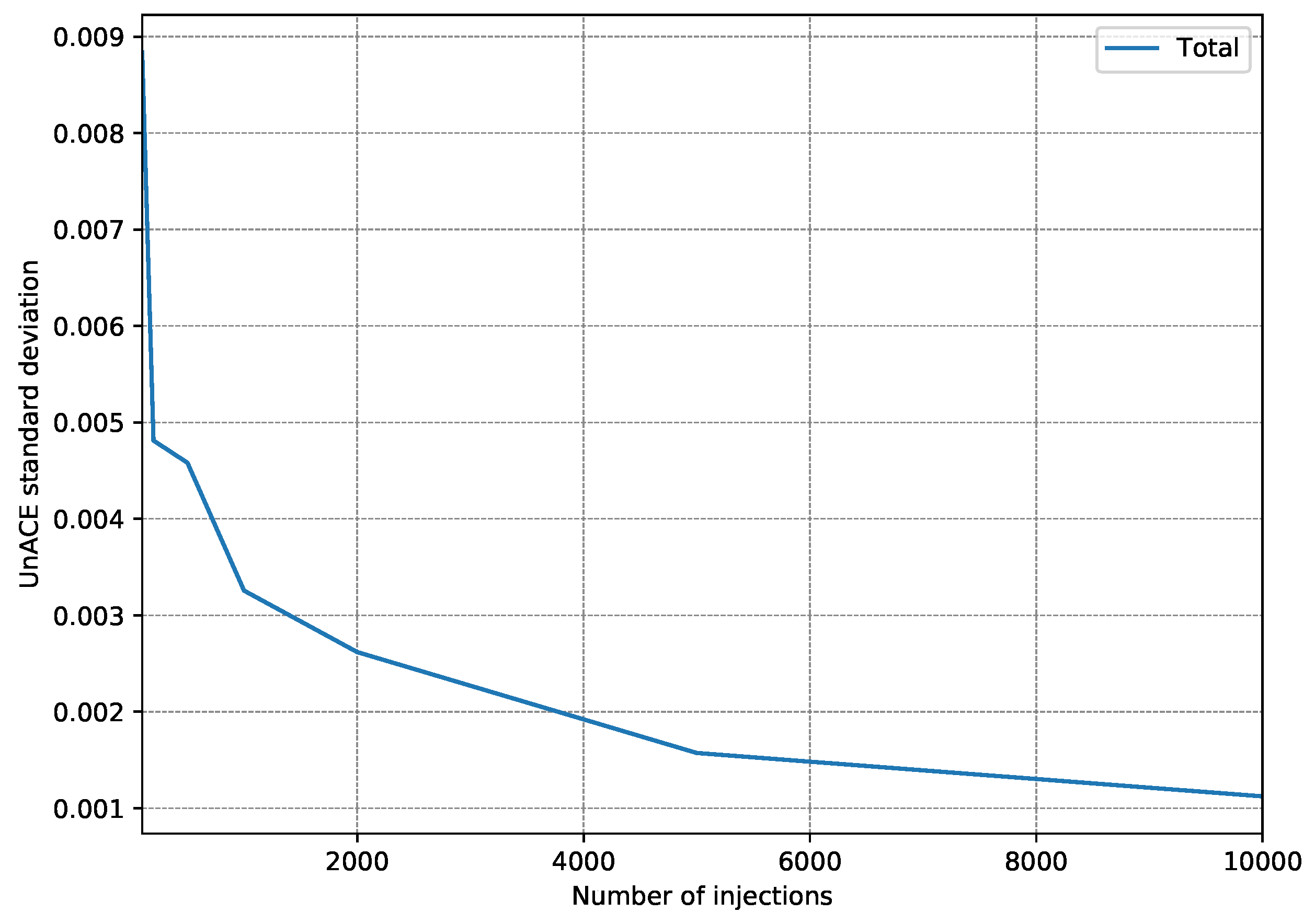

- First, 15 fault injection campaigns were carried out, injecting 100 faults per register (a single fault per execution).

- After each injection campaign, the faults classified as unACE are totalized. Only registers used in the test program are taken into account since injection into a register that is not used would always be classified as unACE.

- With the 15 campaign results, the standard deviation is calculated to estimate how scattered they are.

- The whole procedure is repeated, each time increasing the number of injections per register to be performed.

5. Results and Discussion

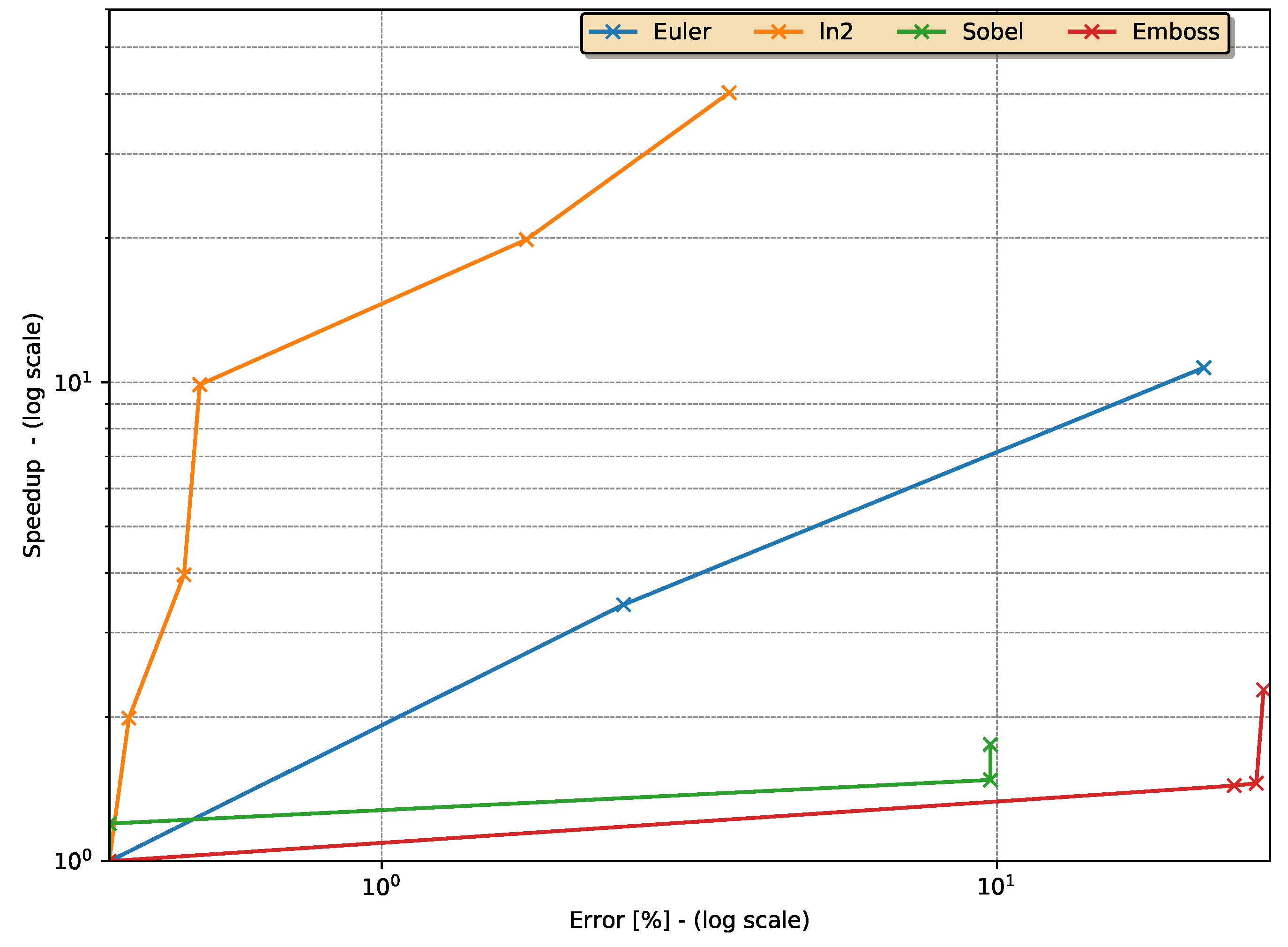

5.1. Approximation Speed-Up vs. Error Percentage

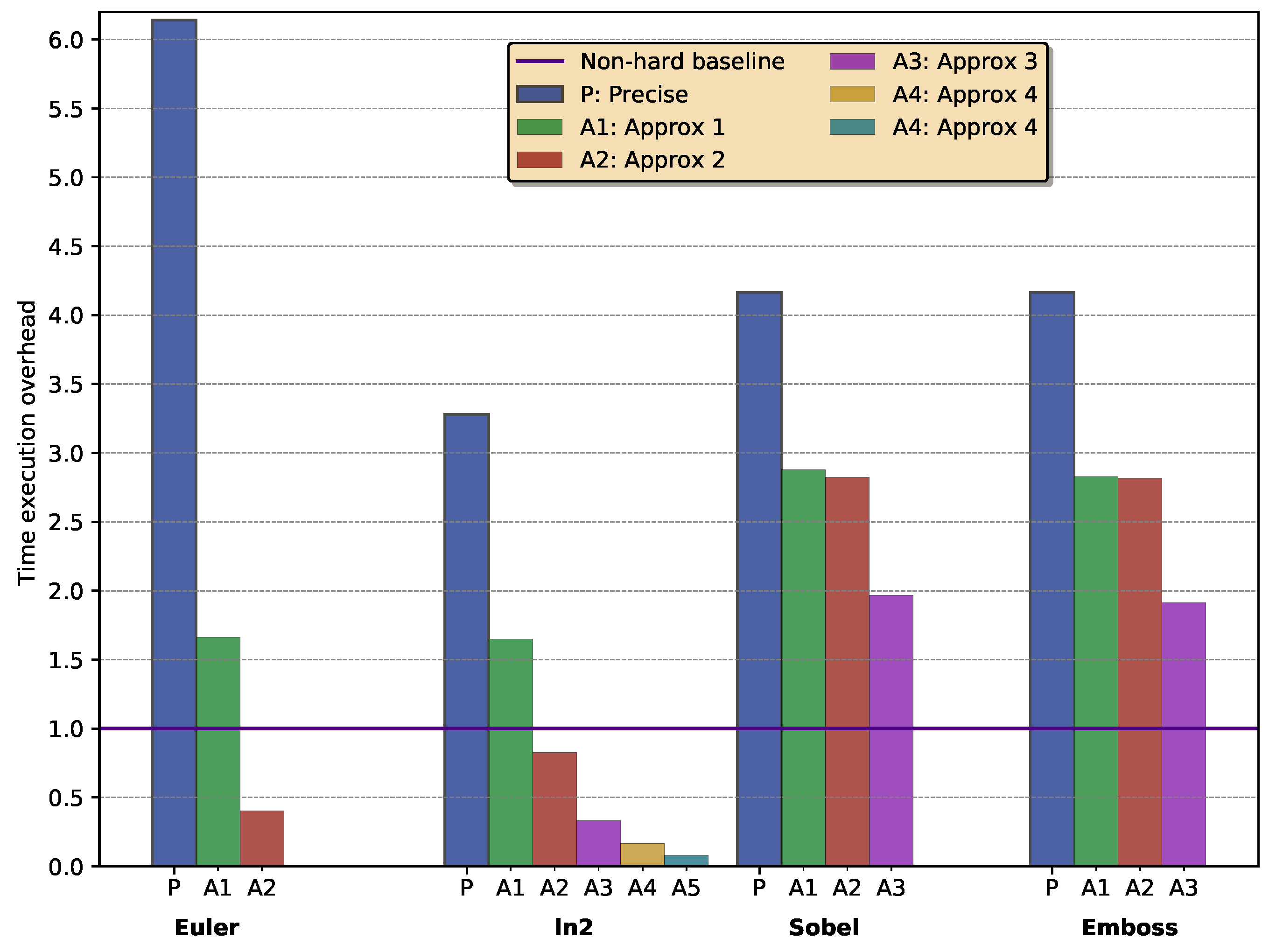

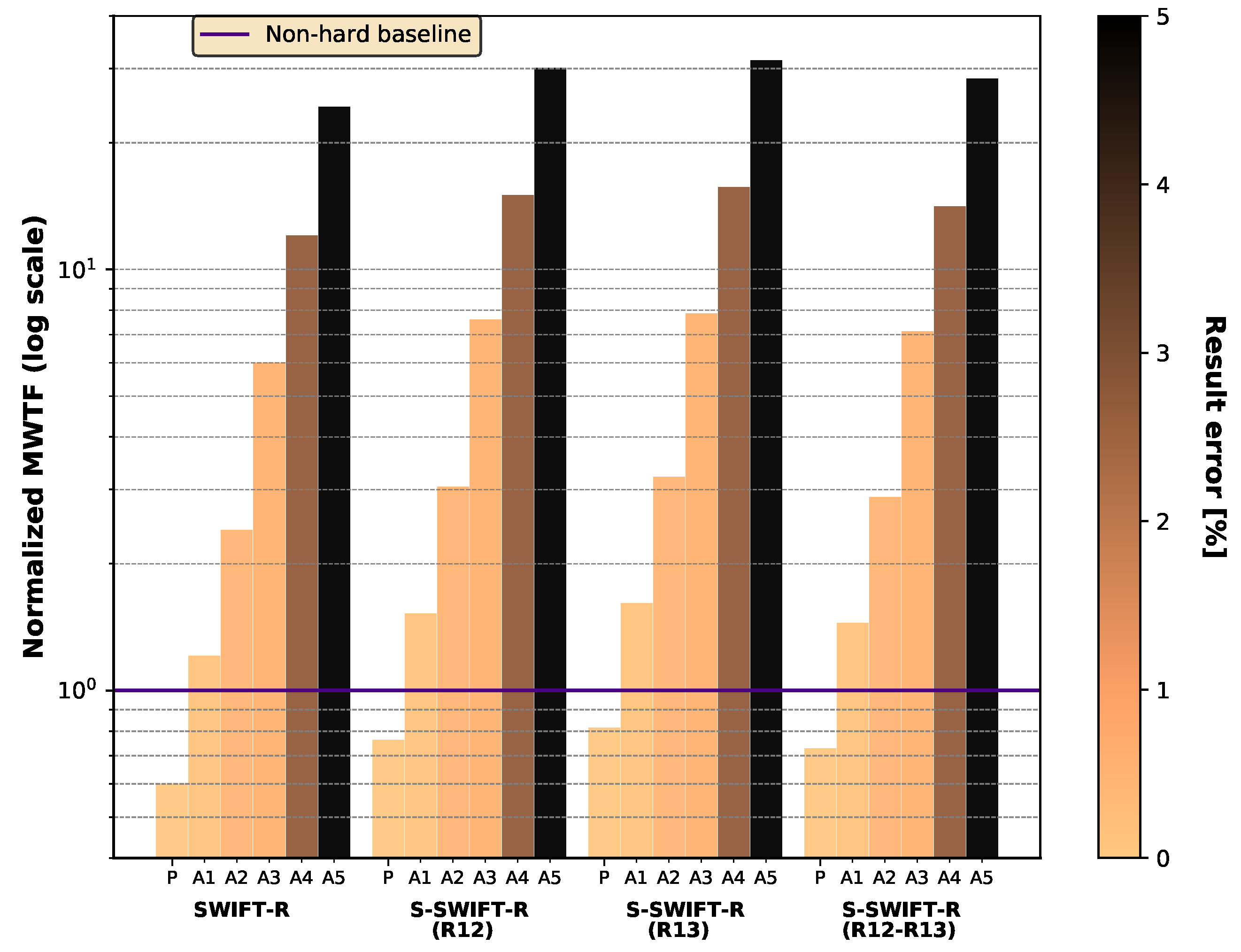

5.2. Execution Time Overheads

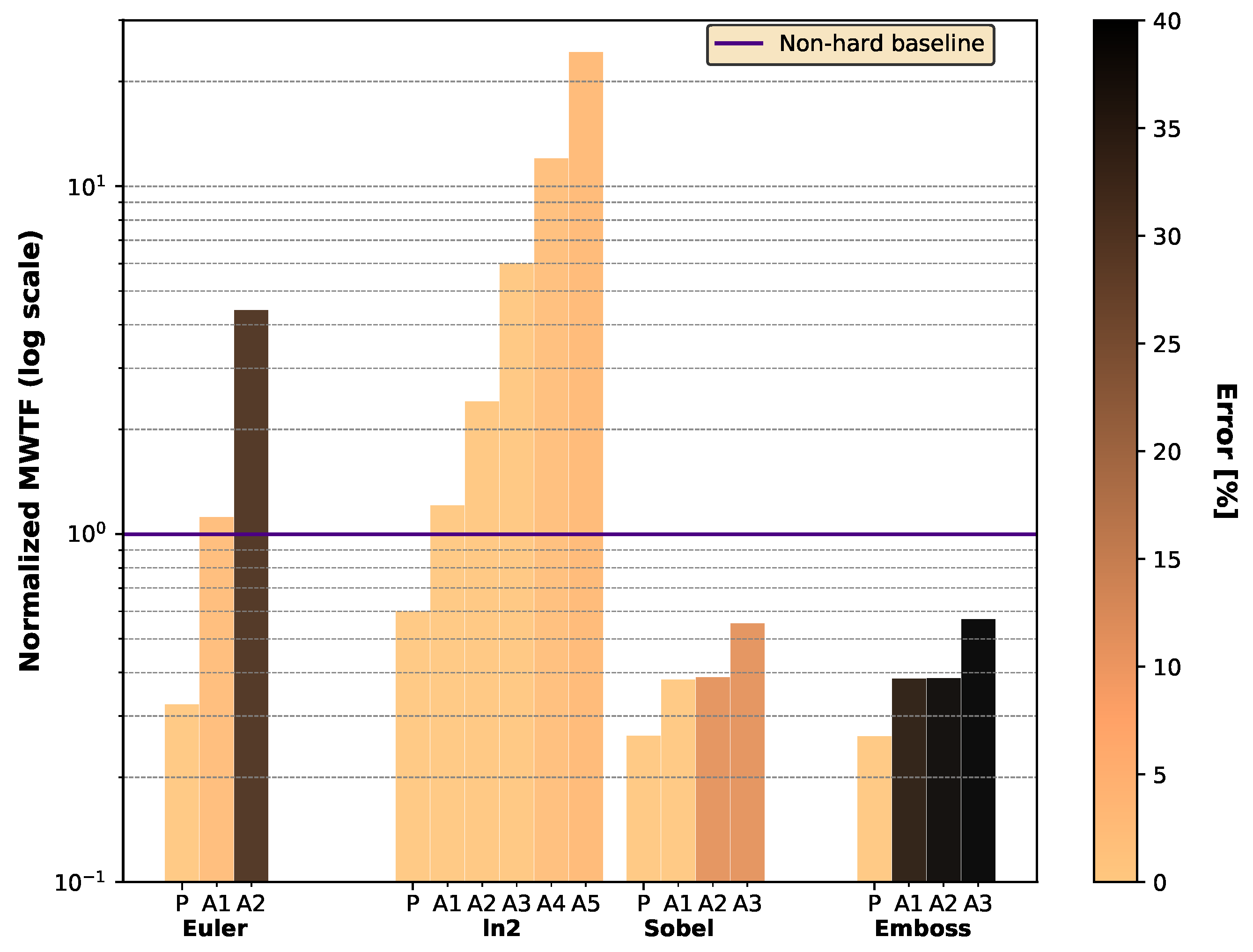

5.3. Reliability and Error Percentage

5.4. Selective Hardening

6. Conclusions and Future Work

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Shivakumar, P.; Kistler, M.D.; Keckler, S.W.; Burger, D.C.; Alvisi, L. Modeling the effect of technology trends on the soft error rate of combinational logic. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Dependable Systems and Networks, Bethesda, MD, USA, 23–26 June 2002; pp. 389–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heijmen, T. Soft Errors from Space to Ground: Historical Overview, Empirical Evidence, and Future Trends. In Soft Errors in Modern Electronic Systems; Nicolaidis, M., Ed.; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 2011; pp. 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Q.; Jiang, J. An overview of radiation effects on electronic devices under severe accident conditions in NPPs, rad-hardened design techniques and simulation tools. Prog. Nucl. Energy 2019, 114, 105–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ECSS. Techniques for Radiation Effects Mitigation in ASICs and FPGAs Handbook (1 September 2016)|European Cooperation for Space Standardization; ESA Requirements and Standards Division: Noordwijk, The Netherlands, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Martínez-Álvarez, A.; Cuenca-Asensi, S.; Restrepo-Calle, F. Soft Error Mitigation in Soft-Core Processors. In FPGAs and Parallel Architectures for Aerospace Applications; Kastensmidt, F., Rech, P., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; Chapter 16; pp. 239–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goloubeva, O.; Rebaudengo, M.; Sonza Reorda, M.; Violante, M. Software-Implemented Hardware Fault Tolerance; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Restrepo-Calle, F.; Martínez-Álvarez, A.; Cuenca-Asensi, S.; Jimeno-Morenilla, A. Selective SWIFT-R. A Flexible Software-Based Technique for Soft Error Mitigation in Low-Cost Embedded Systems. J. Electron. Test. 2013, 29, 825–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Chielle, E.; Azambuja, J.R.; Barth, R.S.; Almeida, F.; Kastensmidt, F.L. Evaluating selective redundancy in data-flow software-based techniques. IEEE Trans. Nucl. Sci. 2013, 60, 2768–2775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Q.; Hoffmann, H.; Khan, O. A Cross-Layer Multicore Architecture to Tradeoff Program Accuracy and Resilience Overheads. IEEE Comput. Archit. Lett. 2015, 14, 85–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez, A.; Entrena, L.; Kastensmidt, F. Approximate TMR for selective error mitigation in FPGAs based on testability analysis. In Proceedings of the 2018 NASA/ESA Conference on Adaptive Hardware and Systems (AHS), Edinburgh, UK, 6–9 August 2018; pp. 112–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mittal, S. A Survey of Techniques for Approximate Computing. ACM Comput. Surv. 2016, 48, 1–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benso, A.; Di Carlo, S.; Di Natale, G.; Prinetto, P.; Tagliaferri, L. Control-flow checking via regular expressions. In Proceedings of the 10th Asian Test Symposium, Kyoto, Japan, 19–21 November 2001; pp. 299–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goloubeva, O.; Rebaudengo, M.; Sonza Reorda, M.; Violante, M. Soft-error detection using control flow assertions. In Proceedings of the 16th IEEE Symposium on Computer Arithmetic, Santiago de Compostela, Spain, 15–18 June 2003; pp. 581–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, N.; McCluskey, E.J. Error detection by selective procedure call duplication for low energy consumption. IEEE Trans. Reliab. 2002, 51, 392–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reis, G.; Chang, J.; Vachharajani, N.; Rangan, R.; August, D. SWIFT: Software Implemented Fault Tolerance. In Proceedings of the International Symposium on Code Generation and Optimization, San Jose, CA, USA, 20–23 March 2005; pp. 243–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, J.; Reis, G.; August, D. Automatic Instruction-Level Software-Only Recovery. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Dependable Systems and Networks (DSN’06), Philadelphia, PA, USA, 25–28 June 2006; pp. 83–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Q.; Mytkowicz, T.; Kim, N.S. Approximate Computing: A Survey. IEEE Des. Test 2016, 33, 8–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aponte-Moreno, A.; Moncada, A.; Restrepo-Calle, F.; Pedraza, C. A review of approximate computing techniques towards fault mitigation in HW/SW systems. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE LATS, Sao Paulo, Brazil, 12–14 March 2018; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esmaeilzadeh, H.; Sampson, A.; Ceze, L.; Burger, D. Neural Acceleration for General-Purpose Approximate Programs. In Proceedings of the 2012 45th Annual IEEE/ACM International Symposium on Microarchitecture (MICRO), Vancouver, BC, Canada, 1–5 December 2012; Volume 33. [Google Scholar]

- Alaghi, A.; Hayes, J.P. STRAUSS: Spectral Transform Use in Stochastic Circuit Synthesis. IEEE Trans Comput.-Aided Des. Integr. Circuits Syst 2015, 34, 1770–1783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Leussen, M.; Huisken, J.; Wang, L.; Jiao, H.; de Gyvez, J.P. Reconfigurable Support Vector Machine Classifier with Approximate Computing. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE Computer Society Annual Symposium on VLSI (ISVLSI), Bochum, Germany, 3–5 July 2017; pp. 13–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X.; Yan, G.; Han, Y.; Li, X. ACR: Enabling computation reuse for approximate computing. In Proceedings of the ASP-DAC, Macau, China, 25–28 January 2016; pp. 643–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, N.M.; Manogaran, E.; Wong, W.F.; Anoosheh, A. Efficient floating point precision tuning for approximate computing. In Proceedings of the 2017 22nd ASP-DAC, Chiba, Japan, 16–19 January 2017; pp. 63–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubio-González, C.; Nguyen, C.; Nguyen, H.D.; Demmel, J.; Kahan, W.; Sen, K.; Bailey, D.H.; Iancu, C.; Hough, D. Precimonious. In Proceedings of the International Conference for High Performance Computing, Networking, Storage and Analysis on SC ’13, Denver, CO, USA, 17–21 November 2013; ACM Press: New York, NY, USA, 2013; pp. 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aamodt, T.M.; Chow, P. Compile-time and instruction-set methods for improving floating- to fixed-point conversion accuracy. ACM Trans Embed. Comput. Syst. 2008, 7, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Misailovic, S.; Sidiroglou, S.; Hoffmann, H.; Rinard, M. Quality of service profiling. In Proceedings of the 32nd ACM/IEEE International Conference on Software Engineering - ICSE ’10, Cape Town, South Africa, 1–8 May 2010; ACM Press: New York, NY, USA, 2010; Volume 1, p. 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sidiroglou-Douskos, S.; Misailovic, S.; Hoffmann, H.; Rinard, M. Managing performance vs. accuracy trade-offs with loop perforation. In Proceedings of the 19th ACM SIGSOFT symposium and the 13th European Conference on Foundations of Software Engineering—SIGSOFT/FSE ’11, Szeged, Hungary, 5–9 September 2011; ACM Press: New York, NY, USA, 2011; p. 124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renganarayana, L.; Srinivasan, V.; Nair, R.; Prener, D. Programming with relaxed synchronization. In Proceedings of the 2012 ACM Workshop on Relaxing Synchronization for Multicore and Manycore Scalability—RACES ’12, Tucson, AZ, USA, 21–25 October 2012; ACM Press: New York, NY, USA, 2012; p. 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salehi, M.; Tavana, M.K.; Rehman, S.; Kriebel, F.; Shafique, M.; Ejlali, A.; Henkel, J. DRVS: Power-efficient reliability management through Dynamic Redundancy and Voltage Scaling under variations. In Proceedings of the 2015 IEEE/ACM ISLPED, Rome, Italy, 22–24 July 2015; pp. 225–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baharvand, F.; Ghassem Miremadi, S. LEXACT: Low Energy N-Modular Redundancy Using Approximate Computing for Real-Time Multicore Processors. IEEE TETC 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choudhury, M.R.; Mohanram, K. Approximate logic circuits for low overhead, non-intrusive concurrent error detection. In Proceedings of the 2008 DATE, Munich, Germany, 10–14 March 2008; Volume 1, pp. 903–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes, I.A.C.; Kastensmidt, F.G.L. Reducing TMR overhead by combining approximate circuit, transistor topology and input permutation approaches. In Proceedings of the Chip in Curitiba 2013—SBCCI 2013: 26th Symposium on Integrated Circuits and Systems Design, Curitiba, Brazil, 2–6 September 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arifeen, T.; Hassan, A.S.; Moradian, H.; Lee, J.A. Probing Approximate TMR in Error Resilient Applications for Better Design Tradeoffs. In Proceedings of the 19th Euromicro Conference on Digital System Design (DSD 2016), Limassol, Cyprus, 31 August–2 September 2016; pp. 637–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arifeen, T.; Hassan, A.; Lee, J.A. A Fault Tolerant Voter for Approximate Triple Modular Redundancy. Electronics 2019, 8, 332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, H.; Leem, L.; Mitra, S. ERSA: Error Resilient System Architecture for Probabilistic Applications. IEEE Trans. Comput.-Aided Des. Integr. Circuits Syst. 2012, 31, 546–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omar, H.; Shi, Q.; Ahmad, M.; Dogan, H.; Khan, O. Declarative Resilience. ACM Trans. Embed. Comput. Syst. 2018, 17, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, G.S.; Kastensmidt, F.L.; Pouget, V.; Bosio, A. Performances VS Reliability: How to exploit Approximate Computing for Safety-Critical applications. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE 24th International Symposium on On-Line Testing And Robust System Design (IOLTS), Platja d’Aro, Spain, 2–4 July 2018; pp. 291–294. [Google Scholar]

- Rodrigues, G.S.; Barros de Oliveira, Á.; Kastensmidt, F.L.; Pouget, V.; Bosio, A. Assessing the Reliability of Successive Approximate Computing Algorithms under Fault Injection. J. Electron. Test. 2019, 35, 367–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, G.S.; Barros de Oliveira, A.; Bosio, A.; Kastensmidt, F.L.; Pignaton de Freitas, E. ARFT: An Approximative Redundant Technique for Fault Tolerance. In Proceedings of the 2018 Conference on Design of Circuits and Integrated Systems (DCIS), Lyon, France, 14–16 November 2018; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aponte-Moreno, A.; Pedraza, C.; Restrepo-Calle, F. Reducing Overheads in Software-based Fault Tolerant Systems using Approximate Computing. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE 20th Latin-American Test Symposium (LATS), Santiago, Chile, 11–13 March 2019; pp. 36–41. [Google Scholar]

- Sampson, A.; Baixo, A.; Ransford, B.; Moreau, T.; Yip, J.; Ceze, L.; Oskin, M. ACCEPT: A Programmer-Guided Compiler Framework for Practical Approximate Computing; Technical Report; University of Washington: Washington, DC, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Mukherjee, S.S.; Weaver, C.T.; Emer, J.; Reinhardt, S.K.; Austin, T. Measuring Architectural Vulnerability Factors. IEEE Micro 2003, 23, 70–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reis, G.; Chang, J.; Vachharajani, N.; Rangan, R.; August, D.; Mukherjee, S. Design and Evaluation of Hybrid Fault-Detection Systems. In Proceedings of the 32nd International Symposium on Computer Architecture (ISCA’05), Madison, WI, USA, 4–8 June 2005; pp. 148–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Corso, D.; Passerone, C.; Reyneri, L.M.; Sansoe, C.; Borri, M.; Speretta, S.; Tranchero, M. Architecture of a Small Low-Cost Satellite. In Proceedings of the 10th Euromicro Conference on Digital System Design Architectures, Methods and Tools (DSD 2007), Lubeck, Germany, 29–31 August 2007; pp. 428–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vladimirova, T.; Wu, X.; Bridges, C.P. Development of a Satellite Sensor Network for Future Space Missions. In Proceedings of the 2008 IEEE Aerospace Conference, Big Sky, MT, USA, 1–8 March 2008; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neji, B.; Hamrouni, C.; Alimi, A.M.; Alim, A.R.; Schilling, K. ERPSat-1 scientific pico satellite development. In Proceedings of the 2010 IEEE International Systems Conference, San Diego, CA, USA, 5–8 April 2010; pp. 255–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez-Alvarez, A.; Cuenca-Asensi, S.; Restrepo-Calle, F.; Pinto, F.R.P.; Guzman-Miranda, H.; Aguirre, M.A. Compiler-Directed Soft Error Mitigation for Embedded Systems. IEEE Trans. Dependable Secur. Comput. 2012, 9, 159–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aponte-Moreno, A.; Restrepo-Calle, F.; Pedraza, C. MiFIT: A Fault Injection Tool to Validate the Reliability of Microprocessors. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE 20th Latin-American Test Symposium (LATS), Santiago, Chile, 11–13 March 2019; pp. 8–12. [Google Scholar]

- Leveugle, R.; Calvez, A.; Maistri, P.; Vanhauwaert, P. Statistical fault injection: Quantified error and confidence. In Proceedings of the 2009 Design, Automation & Test in Europe Conf & Exhibition, Nice, France, 20–24 April 2009; pp. 502–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Aponte-Moreno, A.; Restrepo-Calle, F.; Pedraza, C. Using Approximate Computing and Selective Hardening for the Reduction of Overheads in the Design of Radiation-Induced Fault-Tolerant Systems. Electronics 2019, 8, 1539. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics8121539

Aponte-Moreno A, Restrepo-Calle F, Pedraza C. Using Approximate Computing and Selective Hardening for the Reduction of Overheads in the Design of Radiation-Induced Fault-Tolerant Systems. Electronics. 2019; 8(12):1539. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics8121539

Chicago/Turabian StyleAponte-Moreno, Alexander, Felipe Restrepo-Calle, and Cesar Pedraza. 2019. "Using Approximate Computing and Selective Hardening for the Reduction of Overheads in the Design of Radiation-Induced Fault-Tolerant Systems" Electronics 8, no. 12: 1539. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics8121539

APA StyleAponte-Moreno, A., Restrepo-Calle, F., & Pedraza, C. (2019). Using Approximate Computing and Selective Hardening for the Reduction of Overheads in the Design of Radiation-Induced Fault-Tolerant Systems. Electronics, 8(12), 1539. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics8121539