Evaluation of M-Payment Technology and Sectoral System Innovation—A Comparative Study of UK and Indian Models

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

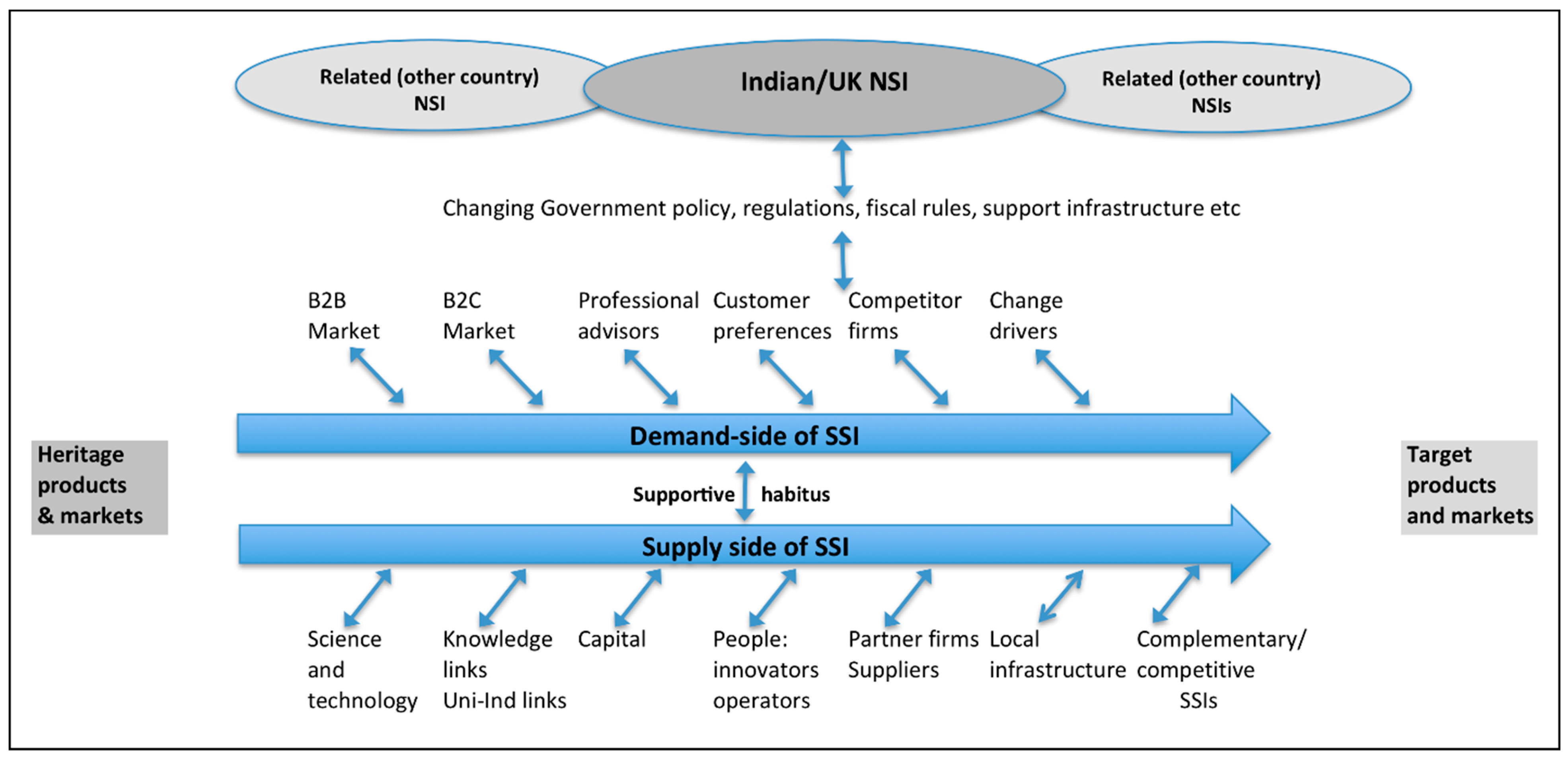

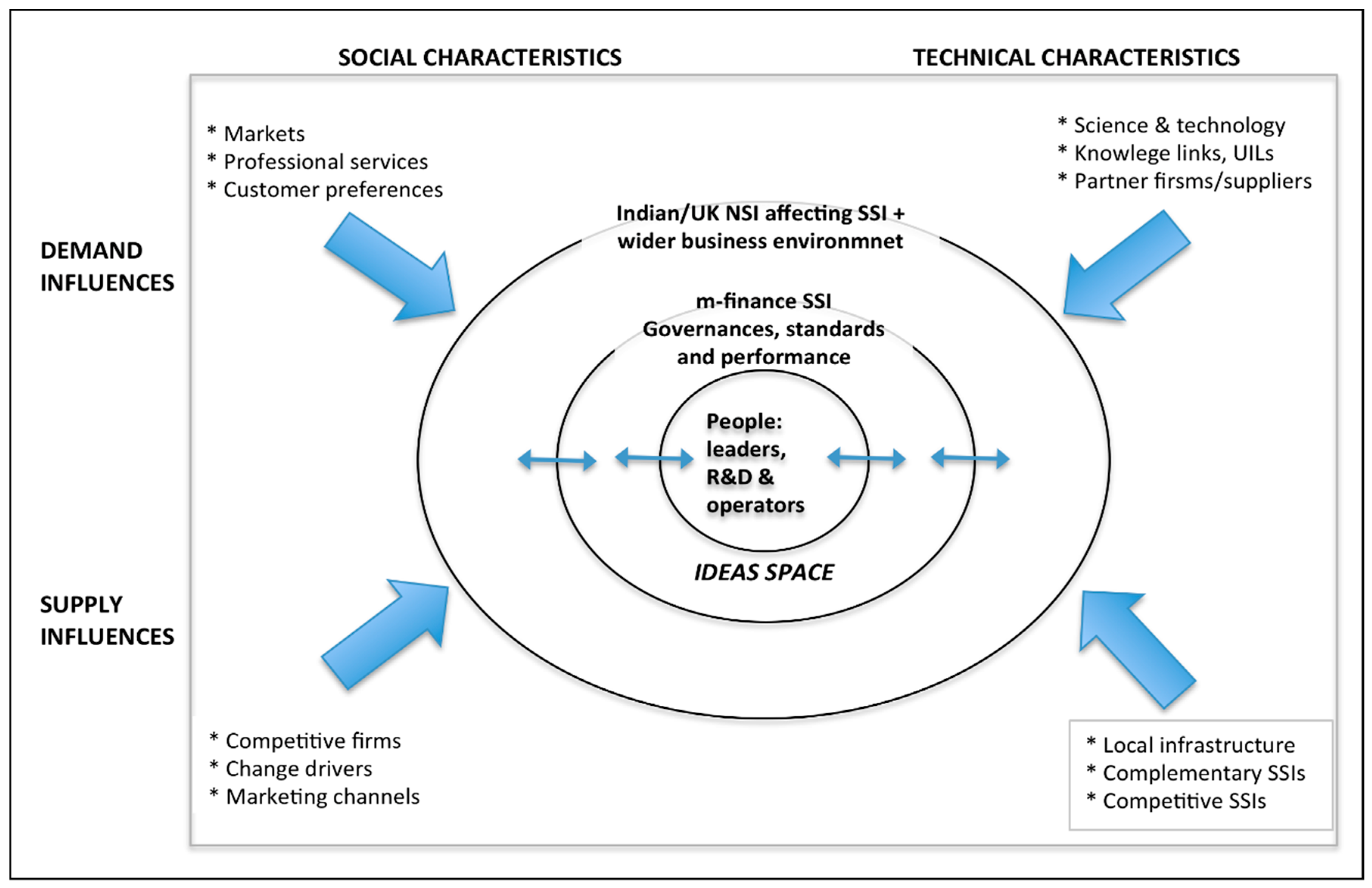

2.1. Sectorial Systems of Innovation (SSI)

2.2. Business Models

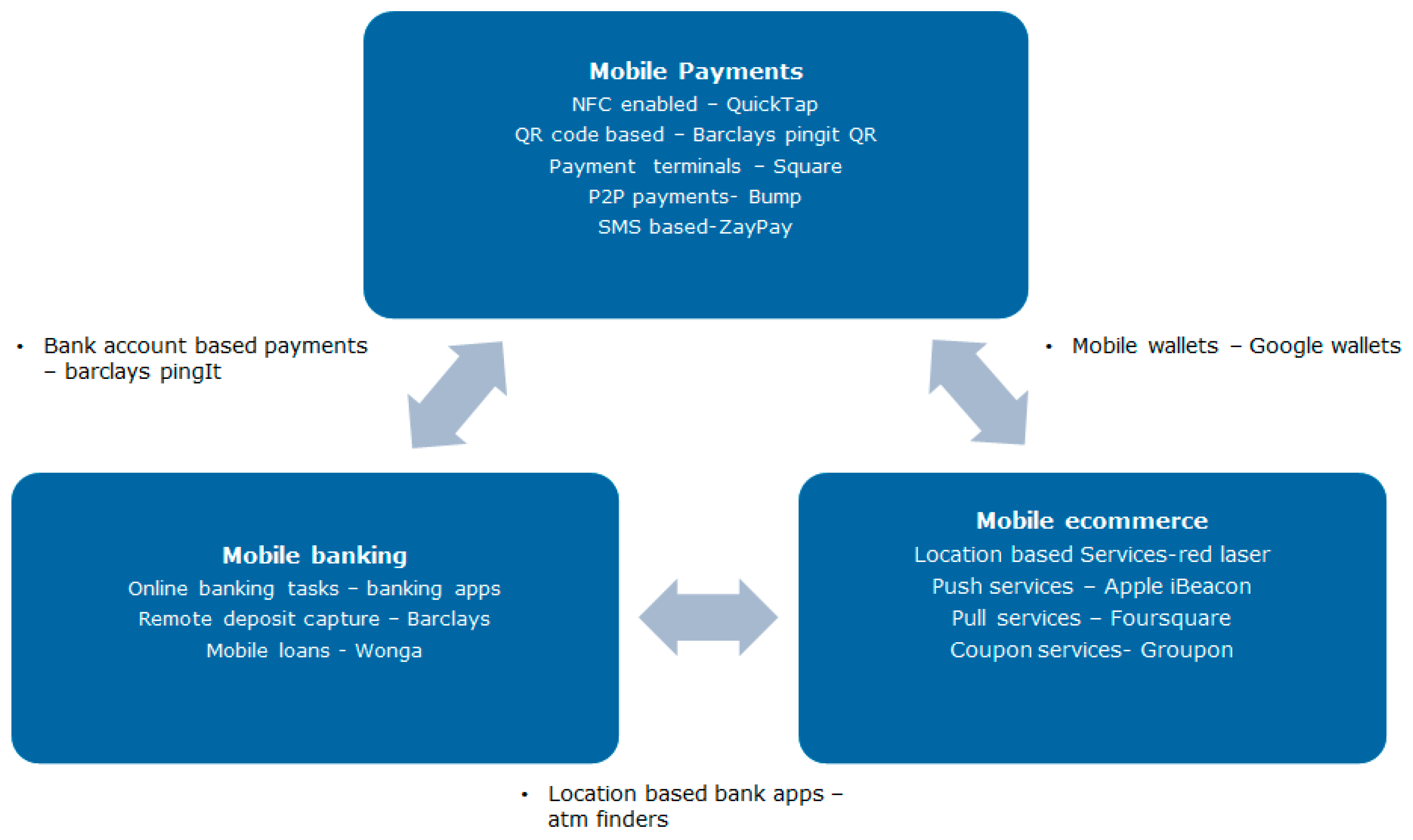

2.3. The Nature of M-Payments

3. Methodology

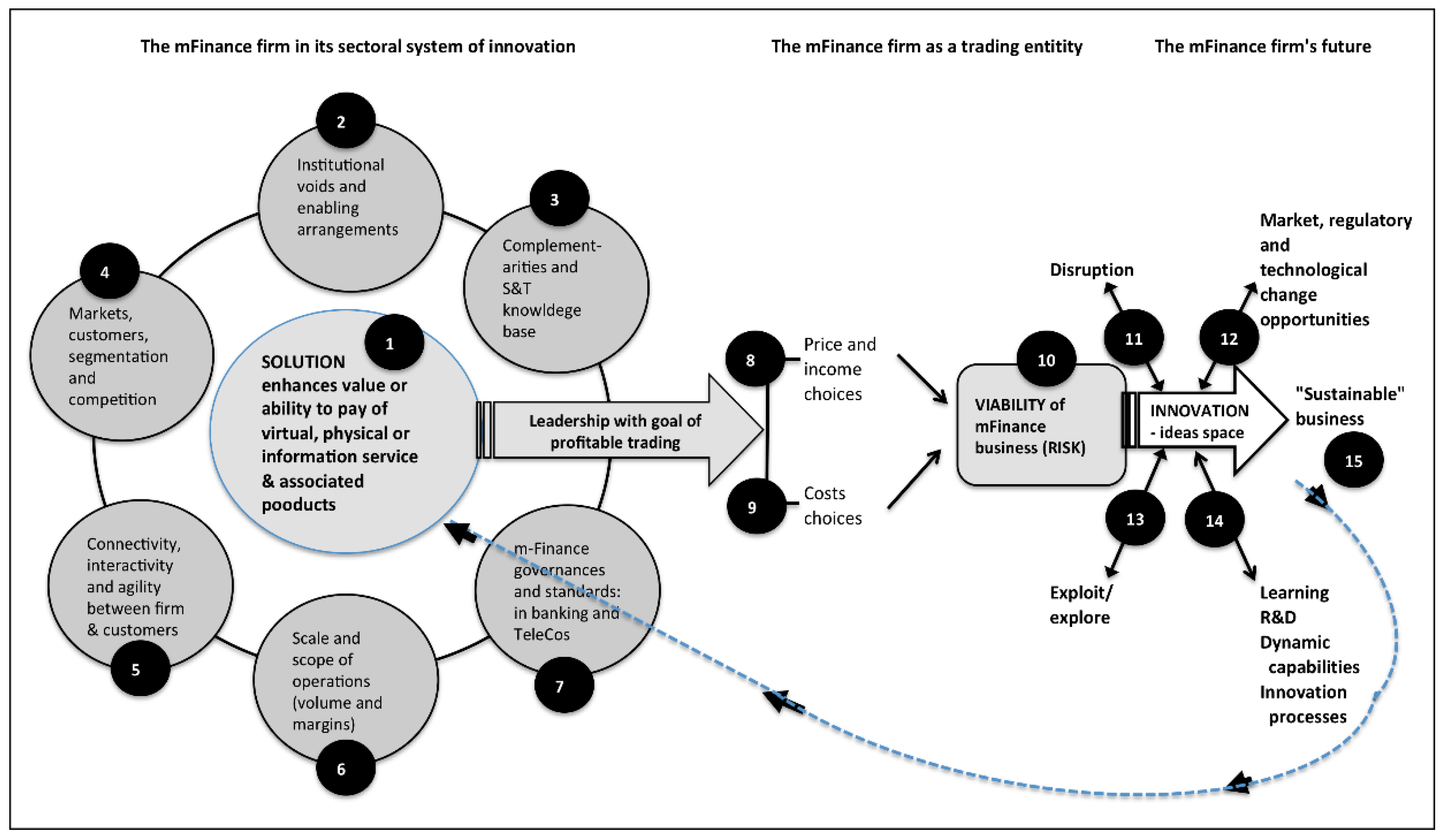

Framework Development

4. Findings

4.1. The UK M-Payments Sectoral Systems of Innovation

4.1.1. Wide Range of Agents

One of the biggest challenges of mobile payments is that it often addresses low value payments, also meaning low revenue per transactions. If you want a sustainable business model, you then need to process higher volumes of transactions, more transactions, less revenue per transaction.

4.1.2. Proprietary Systems

If you have to pay someone else you have to know their bank details, but Pingit will use your mobile phone number as a proxy for sort code or account details; you only need to know the mobile phone number using the app. Useful when you are with group of friends in paying your other friends instead of diving up a debit card. It does not matter what mobile company you are connected with, only that you have to have a bank account. So Pingit is a proxy.

4.1.3. Dominant Banks

Regulation impacts customers, in my opinion, potentially to a more convenient or innovative service. I guess it is also there to protect them, so I guess I have seen a lot of cases recently where banks have abused that and therefore regulation was required. From a bank’s perspective then, to me it levels playing fields, so everyone is impacted by the same regulation. So, whilst it might impact your revenues slightly and impacts everyone’s revenues, it is not as if it is a competitive advantage to be gained.

4.1.4. Legacy Systems and Innovation

4.1.5. Social Impact

4.1.6. Intensity of Competition

Of course, I think most banks haven’t even realized the opportunity for mobile banks, there are so many opportunities to make money. It is the traditional revenue streams that you can make money through, like I mentioned earlier; increasing sales, incremental sales, incremental transactions or incremental interactions with your brands as a bank, through mobile should lead to more and [so] those sorts of traditional revenue lines, these cost production revenue lines around moving people into mobile. Which by and large is the cheapest channel to service at the moment.

4.1.7. Governances

4.2. The Indian M-Payments Sectoral Systems of Innovation

4.2.1. Combined Technological and Social Agendas

4.2.2. Institutions Drive Innovation

So, let me put it this way: India has never prescribed banks to tie up necessarily with operators, or just the telecomm operators. If telecomm operators want to be in the State in India, they need the bank to provide cash out and other services, which are more, banking related. So, if they were to kind of operate a security framework, the multiple regulations out there in India, so that is what comes because you use the world banking correspondent or things like that.

4.2.3. Innovative Firms and Business Models

So, the banking correspondent is basically just an extension of a banking network, so instead of the brick and mortar bank branches you can, you know, reach and therefore be, putting the penetration of banking services. So, it would be anybody in the country, so one of them could be an operator, a mobile network operator because they have this traditional network but they only act on behalf of the bank. The consumer in this case is owned by the bank, so the operator or anybody else, third party, really provides the network from a distribution standpoint, for consumers to access banking services.

So when it is all electronic and you are dealing with just pure electronic stuff, the cost of the transaction can be low but we are dealing with a lot of cash and therefore the exchange of information is really what we have made really cheap; the transactions, the processing of financial transactions are still, and convenient, and easy, and in areas where say, for example, data directing is not available, which is a very large part of the country still, that does not have connectivity.

4.2.4. The Indian Government

5. Discussion

5.1. Drivers of Innovation in the UK and Indian M-Payments Sectors

5.2. Innovation in the UK and Indian M-Payments Sector

6. Conclusions and Implications

Implications

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| No. | Company | Industry | Country of Origin | Public or Private | Countries of Operation for Service |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 A | National Payments Corporation of India (NPCI) | Finance | India | Public | India |

| 2 B | Atom Technologies | Software Technology | India | Private | India |

| 3 C | Eko Indian Financial Services | Finance | India | Private | India |

| 4 D | Mahindra Comviva | Telecommunications | India | Private | Global |

| 5 E | Induslnd Bank | Finance/Banking | India | Private | India |

| 6 F | HDFC | Finance/Banking | India | Public | India |

| 7 G | Idea Cellular | Telecommunications | India | Public | India |

| 8 H | CITI Group | Finance/Banking | US | Public | Global |

| 9 I | iKaaz | Software Technology | India | Private | Global |

| 10 J | Beam Money | Software Technology | India | Public | India |

| 11 K | Standard Charter | Finance/Banking | UK | Public | Global |

| 12 L | Nokia Siemens Networks | Telecommunications Equipment | Finland | Public | Global |

| 13 M | MH Invent | Software/Security | UK | Private | UK/Europe |

| 14 N | Tesco Bank | Finance/Banking/Insurance | UK | Private | UK |

| 15 O | TIBCO Software Limited | Computer Software | US | Public | Global |

| 16 P | Monitise Group | Technology/Services | UK | Public | Global |

| 17 Q | GSM Association | Trade Association for Telcos | UK | Private | Global |

| 18 R | Royal Bank of Scotland | Finance/Banking | UK | Public | Global |

| 19 S | Sainsbury Bank | Finance/Banking | UK | Public | UK |

| 20 T | Lloyds TSB | Finance/Banking | UK | Public | UK |

| 21U | Barclays | Finance/Banking | UK | Public | UK |

References

- Chang, H.J. Institutional Change and Economic Development; Anthem Press: New York, NY, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Gartner. Gartner Says Worldwide Mobile Payment Transaction Value to Surpass $171.5 Billion. 29 May 2012. Available online: http://www.gartner.com/newsroom/id/2028315 (accessed on 2 November 2013).

- Reserve Bank of India. M-Banking in India—Regulations and Rationale. 2012. Available online: http://www.rbi.org.in/scripts/BS_SpeechesView.aspx?id=681 (accessed on 3 November 2013).

- Crabbe, M.; Standing, S.; Karjaluoto, H.; Standing, C. An adoption model for mobile banking in Ghana. Int. J. Mob. Commun. 2009, 7, 515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, J.C.; Lee, S.C.; Suh, Y.H. Determinants of Behavioural Intention to Mobile Banking. Expert Syst. Appl. 2009, 36, 11605–11616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demirguc-Kunt, A.; Klapper, L.; Randall, D. The Global Findex Database Financial Inclusion in India; The World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2013; Available online: http://siteresources.worldbank.org/EXTGLOBALFIN/Resources/8519638-1332259343991/N8india6pg3.pdf (accessed on 20 February 2014).

- Mallat, N. Exploring Consumer Adoption of Mobile Payments—A Qualitative Study. Sprouts Work. Pap. Inf. Syst. 2006, 6, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shon, T.H.; Swatman, P.M.C. Identifying effectiveness criteria for Internet payment systems. Internet Res. 1998, 8, 202–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siau, K.; Sheng, H.; Nah, F.; Davis, S. A qualitative investigation on consumer trust in mobile commerce. Int. J. Electron. Bus. 2004, 2, 283–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayawardhena, C.; Foley, P. Overcoming constraints on electronic commerce: Internet payment systems. J. Gen. Manag. 1998, 24, 19–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogle, R. Smart World; Harvard Business School Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Breschi, S.; Malerba, F. Sectoral Innovation Systems: Technological Regimes, Schumpeterian Dynamics and Spatial Boundaries; Edquist, C., Ed.; Systems of Innovation Pinter: London, UK, 1997; pp. 130–156. [Google Scholar]

- Geels, F.W. Sectoral systems of innovation to socio-technical systems: Insights about dynamics and change from sociology and institutional theory. Res. Policy 2004, 33, 897–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trist, E. Referent organisations and the development of inter-organisational domains. Hum. Relat. 1951, 36, 269–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varieties of Capitalism; Hall, P.A., Soskice, D.W., Eds.; OUP: Oxford, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Casper, S. Creating Silicon Valley in Europe; OUP: Oxford, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Scott, W.R. Institutions and Organisations; SAGE: London, UK, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Kay, J. The Truth about Markets; Penguin: London, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Gladwell, M. The Tipping Point: How Little Things Can Make a Big Difference; Little, Brown and Co.: Boston, MA, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Hughes, T.P. Networks of Power: Electrification in Western Society, 1880–1930; The Johns Hopkins University Press: Baltimore, MD, USA, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Malerba, F. Sectoral systems of innovation and production. Res. Policy 2002, 31, 247–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lave, J. Situated learning in communities of practice. In Perspectives on Socially Shared Cognition; Resnick, L.B., Levine, J.M., Teasley, S.D., Eds.; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 1993; pp. 63–82. [Google Scholar]

- Nardi, B.A. Studying context: A comparison of activity theory, situated action models, and distributed cognition. In Context and Consciousness: Activity Theory and Human-Computer Interaction; Nardi, B.A., Ed.; The MIT Press: London, UK, 1996; pp. 69–102. [Google Scholar]

- Bourdieu, P. Systems of education and systems of thoughts. In Knowledge and Control; Young, F.D., Ed.; Collier-Macmillan: London, UK, 1997; pp. 189–207. [Google Scholar]

- Herrmann, A.; Peine, A. When ‘national innovation system’ meet ‘varieties of capitalism’ arguments on labour qualifications: On the skill types and scientific knowledge needed for radical and incremental product innovations. Res. Policy 2011, 40, 687–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Østergaard, C.R.; Timmermans, B.; Kristinsson, K. Does a different view create something new? The effect of employee diversity on innovation. Res. Policy 2011, 40, 500–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schumpeter, J.A. Business Cycles: A Theoretical, Historical and Statistical Analysis of the Capitalist Process; McGraw-Hill: London, UK, 1939. [Google Scholar]

- Park, H. Technology convergence, open innovation, and dynamic economy. J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex. 2017, 3, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, R.R.; Winter, S. An Evolutionary Theory of Economic Change; Harvard University Press: Boston, MA, USA, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Vargo, S.L.; Lusch, R.F. Evolving to a New Dominant Logic for Marketing. J. Mark. 2004, 68, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vargo, S.L.; Lusch, R.F. Service-dominant Logic: Continuing the Evolution. J. Acad. Mark. 2008, 36, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bitner, M.; Ostrom, A.; Morgan, F. Service blueprinting: A practical technique for service. California Management Review. 2007, 50, 66–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amit, R.; Zott, C. Value creation in E-business. Strateg. Manag. J. 2001, 22, 493–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chesbrough, H. Business model innovation: it’s not just about technology anymore. Strategy Leadersh. 2007, 35, 12–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yun, J. How do we conquer the growth limits of capitalism? Schumpeterian Dynamics of Open Innovation. J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex. 2015, 1, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patra, S.; Krishna, V. Globalization of R&D and open innovation: Linkages of foreign R&D centers in India. J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex. 2015, 1, 7. [Google Scholar]

- Dweck, C.S. Mindset: The New Psychology of Success; Random House: New York, NY, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Granovetter, M. The strength of weak ties. Am. J. Sociol. 1973, 78, 1360–1380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chesbrough, H. Business model innovation: Opportunities and barriers. Long Range Plan. 2010, 43, 354–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGrath, R. Business Models: A Discovery Driven Approach. Long Range Plan. 2010, 43, 247–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demil, B.; Lecocq, X. Business Model Evolution: In Search of Dynamic Consistency. Long Range Plan. 2010, 43, 227–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, W.K.; Binns, A.; Tushman, M.L. Complex business models: Managing strategic paradoxes simultaneously. Long Range Plan. 2010, 43, 448–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turban, E.; King, D.; Lee, J. Electronic Commerce 2006; Pearson Educational International: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Laukkanen, T. Internet vs. mobile banking: Comparing customer value perceptions. Bus. Process Manag. J. 2007, 13, 788–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karnouskos, S.; Fokus, F. Mobile Payment: A journey through existing procedures and standardization initiatives. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tutor. 2004, 6, 44–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahlberg, T.; Mallat, N.; Ondrus, J. Past, present and future of mobile payments research: A literature review. Electron. Commer. Res. Appl. 2008, 7, 165–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryman, A.; Bell, E. Business Research Methods; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Rabinow, P.; Sullivan, W.M. Interpretive Social Science, 2nd ed.; University of California Press: Berkeley, CA, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Yanow, D. Conducting Interpretive Policy Analysis; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Hewitt-Taylor, J. Use of constant comparative analysis in qualitative research. Nurs. Standard. 2001, 15, 39–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ambert, A.; Adler, P.A.; Adler, P.; Detzner, D.F. Understanding and evaluating qualitative research. J. Marriage Fam. 1995, 57, 879–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schiffman, L.G.; Kanuk, L. Consumer Behaviour; Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Tvede, L.; Ohnemus, P. Marketing Strategies for the New Economy; John Wiley & Sons: Chichester, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Saunders, M.; Lewis, P.; Thornhill, A. Research Methods for Business Students, 4th ed.; Pearson Education: Harlow, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Eisenhardt, K.M. Building Theories from Case Study Research. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1989, 14, 532–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartley, J.F. Case studies in organizational research. In Qualitative Methods in Organizational Research; Cassell, C., Symon, G., Eds.; Sage: London, UK, 1994; pp. 209–229. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, R. Applied Social Research Methods Series. In Case Study Research: Design and Methods; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1994; Volume 5. [Google Scholar]

- Eisenhardt, K.; Graebner, M. Theory Building From Cases: Opportunities and Challenges. Acad. Manag. 2007, 50, 25–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frederickson, J. Strategic Process Research: Questions and Recommendations. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1983, 8, 565–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llewelyn, S. What counts as “theory” in qualitative management and accounting research? Introducing five levels of theorizing. Account. Audit. Account. J. 2003, 16, 662–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourgeois, L.J. III Toward a Method of Middle Range Theorizing. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1979, 4, 443–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterson, M.F. Embedded Organisational Events: The Units of Process in Organisation Science. Organ. Sci. 1998, 9, 16–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pauwels, P.; Matthyssens, P. The Architecture of Multiple Case Study Research in International Business. In Handbook of Qualitative Research Methods for International Business; Marschan-Piekkari, R., Welch, C., Eds.; Edward Elgar: Cheltenham, UK, 2004; pp. 125–143. [Google Scholar]

- Gummesson, E. Quality Dimensions: What to Measure in Service Organizations. In Advances in Services Marketing and Management; Swartz, T., Bowen, D.E., Brown, S.W., Eds.; JAI Press: Greenwich, CT, USA, 1992; Volume 1, pp. 177–205. [Google Scholar]

- Elliott, J. Using Narratives in Social Research; Sage: London, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Castells, M. Communication Power; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Ahonen, T. m-Profits; Wiley: Chichester, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Clemons, E.K. Business models for monetizing Internet applications and web sites: Experience, theory and predictions. J. Manag. Inf. Syst. 2009, 26, 15–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ondrus, J.; Lyytinen, K. Mobile payments market: Towards another clash of the Titans? In Proceedings of the 10th International Conference on Mobile Business, Como, Italy, 20–21 June 2011; pp. 166–172. [Google Scholar]

- Whitley, R. Developing innovative competences: The role of institutional frameworks. Ind. Corp. Chang. 2002, 11, 497–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godschalk, H.; Krueger, M. Why e-money still fails—Chances of e-money within a competitive payment instrument market. In Proceedings of the Third Berlin Internet Economics Workshop, Berlin, Germany, 26–27 May 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, M.R.; Chien, K.M.; Hong, L.Y.; Yang, T.N. Evaluating the collaborative ecosystem for an innovation-driven economy: a systems analysis and case study of science parks. Sustainability 2018, 10, 887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yun, J.J.; Won, D.; Park, K. Dynamics from open innovation to evolutionary change. J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex. 2016, 2, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yun, J.J.; Won, D.; Park, K. Entrepreneurial cyclical dynamics of open innovation. J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex. 2018, 28, 1151–1174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Utterback, J.; Abernathy, W. A dynamic model of process and product innovation. Omega 1975, 3, 639–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostry, S.; Nelson, R.R. Techno-Nationalism and Techno-Globalism: Conflict and Co-Operation; Brookings Institution: Washington, DC, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

| 1 | Solution: the service offer (virtual, physical or information products) such as P2P payment, or payment for goods: note the connection to business leadership |

| 2 | Institutional thickness or institutional voids enabling/inhibiting m-finance, such as the availability of a banking network to target customers |

| 3 | Complementarity arrangements to m-finance such as Internet penetration, 3G availability and connections into the relevant science and technology base |

| 4 | Customers, how they segment (high value or low-cost business models) and how the firm competes with competitors – its strategic USPs |

| 5 | Basic connectivity, user-provider interactivity and the agility of the firm to respond to opportunities |

| 6 | Scale and scope: range of services, volume of target provision |

| 7 | Key governances and standards impacting on m-finance design and delivery, banking and TeleCos governances and operations |

| 8 | Price/income choices such as ARPU maximization or high-volume low margin services |

| 9 | Cost, cost-sensitivity of the firm and who bears cost within the ecosystem |

| 10 | Viability of business model: can the firm trade at a profit and who is bearing what risk? |

| 11 | Over time, is it likely that the business model and firm can be disrupted? |

| 12 | Over time, are changes in markets, technology or regulation opportunities or threats; such as the impact of the cloud? |

| 13 | Over time, should the firm’s strategy be exploitation or exploration? |

| 14 | Over time, is the firm actively learning, exploiting R&D and evolving dynamic capabilities to remain competitive? |

| 15 | Over time, is the firm capable of the sustained innovation necessary to be a sustainable business, including altering its business model? |

| 1 | Solution: all of the UK has wired Internet coverage, those areas without mobile network coverage are isolated rural settlements, the quality of the connectivity varies. 99.6% of the population can access at least 2G and access (sometimes slowly) a wide range of m-payment services. |

| 2 | Institutional thickness: personal financial services are more highly regulated than apps and mobile connectivity. Institutional arrangements, such as the payment of wages and benefits enforces bank account usage. Institutions drive innovation targeting higher-end customers. |

| 3 | Complementarily arrangements to m-payment: the UK is globally competitive in Internet security, apps development and personal (and investment) financial services innovation as the Barclays case demonstrates. There is a close relationship between industry actor R&D and university research bases around Informatics products such as apps. |

| 4 | UK banks have low or non-existent charges, however, charges are high for additional services (such as overdrafts); banks choose their customers often by de-marketing poorer segments of society: high income individual and businesses are the banks preferred customers, for whom they provide a wide range of services, including traditionally non-Bank services. |

| 5 | Basic connectivity is high; most (3G) users can access highly interactive m-finance services via m-Internet or apps. M-payments are a major area of competition between banks e.g., RBS’s GetCash app. |

| 6 | 25% of the UK m-Internet users access m-finance services, often via dedicated Bank app. Scope of services varies: the Barclays case indicates how m-banking is seen as competitive advantage. |

| 7 | Key governances and standards: while banks are regulated, non-bank organizations are opening banks (retailors), acting as banks (iTunes) or offering C2B payment services (including telcos). |

| 8 | Both banks and telcos compete for higher-value customers meaning those using a wider range of paid-for services. |

| 9 | UK banks and telcos are highly profitable firms squeeze costs by automating services |

| 10 | M-finance firms (including banks) and telcos minimize risk using techniques such as credit scoring and high charges for some services, they trade profitably: risk are exogenous such as the banking crises or over paying for network licenses. |

| 11 | Low cost alternatives (especially cloud-based_ may disrupt, however, regulatory arrangements offer protection to banks and telcos. |

| 12 | Low cost cloud services may disrupt, however, regulation changes would disrupt more. |

| 13 | Banks and telcos currently exploit their existing customer base by expanding service ranges (NFC, PingIt), some organizations (Barclays) see innovation as giving competitive advantage. |

| 14 | R&D (often university-based e.g., automated credit scoring and meta data analysis) supporting automation drives down costs and increases margins. Telcos and banks seek to “bundle” wider ranges of products, trading on brand. |

| 15 | Despite crises (banking, overpayment for licenses, market entry e.g., by retailers) the major firms in the SSI survive profitably and internationalizing. |

| 1 | Solution: recognizing the cost effectiveness of m-finance, the SSI is enabling the diffusion of mobile Internet-enables solutions providing financial inclusion for un-baned citizens. |

| 2 | Institutional thickness: while banking is strongly regulated and non-banks inhibited from providing banking services, institutions support m-finance services to the poor in ways and at costs making them accessible: the institutions service as a social justice agenda. |

| 3 | Complementarily arrangements to m-mobile such as RBI regulations, NCPI infrastructure, TIBCO’s data processing systems, for services such as Indusland Bank and Eko Financial Services, using physical infrastructures (retail outlets, the 2G telephone network). |

| 4 | Customers able to pay charges are served by 3G-enabled m-finance technologies and services provided by the market. Bottom-of-the-pyramid customers can access simpler transaction services, using basic mobile devices leveraging either retail outlets (Eko) or the (numeric literacy) services of Indusland Bank. |

| 5 | Basic (2G) connectivity remains a challenge – around 20% of the population have a mobile, half have the access, many of the 50% are in rural areas outside mobile network reach. 2G networks provide sufficient connectivity for basic m-finance services since firms are shaping services to align with the available technology and absence of banks. |

| 6 | Firms such as Indusland Bank and Eko are sustainable business provided the volume of transactions is high and range of services narrow: it is likely that the scale of these services will continue to increase, with technical network reach a major constraint. |

| 7 | RBI strictly regulates banks; this obliges banks to support NPCI’s infrastructure expansion IMPS (affecting telcos and banks) and inhibits ‘cherry picking’ market strategies by banks or organizations that would otherwise enter the market (such as major retailers or brand names e.g., Infosys, Tata). Governances suit the social justice agenda. |

| 8 | Indian telcos operate on low ARPU; for the BoP segment this is especially so. |

| 9 | Advanced technologies (NFC, complex payments) are limited to 3G users, mainly in urban areas. BoP services are cost sensitive and rely on scale economies and the intermediate/appropriate deployment of back-office technologies by firms such as TIBCO. Regulator pressure on telcos for network expansion imposes costs that they might otherwise choose not to endure. |

| 10 | Banks are protected from risks associate with services to BoP customers or businesses dealing with BoP customers (TIBCO) by intermediaries such Indusland Bank and Eko, who in turn minimize risk using retailer bonds or bank underwriting. |

| 11 | Basic service models will wither as people become richer: not a short-term prospect. |

| 12 | The Cloud (TIBCO) is enhancing the BoP business models by helping contain the costs of high transaction volumes. |

| 13 | As the network reach expands, so too will the customer base. |

| 14 | The sector, especially for BoP customers, is highly innovative, in context. Yet, how far the models are exportable is uncertain. |

| 15 | Eko and Indusland Bank’s business models appear sustainable, provided the rate of enrolment is greater than the rate of customer loss, as their incomes improve. |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Webb, H.; Liu, S.; Yan, M.-R. Evaluation of M-Payment Technology and Sectoral System Innovation—A Comparative Study of UK and Indian Models. Electronics 2019, 8, 1282. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics8111282

Webb H, Liu S, Yan M-R. Evaluation of M-Payment Technology and Sectoral System Innovation—A Comparative Study of UK and Indian Models. Electronics. 2019; 8(11):1282. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics8111282

Chicago/Turabian StyleWebb, Heather, Shubo Liu, and Min-Ren Yan. 2019. "Evaluation of M-Payment Technology and Sectoral System Innovation—A Comparative Study of UK and Indian Models" Electronics 8, no. 11: 1282. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics8111282

APA StyleWebb, H., Liu, S., & Yan, M.-R. (2019). Evaluation of M-Payment Technology and Sectoral System Innovation—A Comparative Study of UK and Indian Models. Electronics, 8(11), 1282. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics8111282