A Review of Embedded Software Architectures for Multi-Sensor Wearable Devices: Sensor Fusion Techniques and Future Research Directions

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Sensor drift and calibration: The accuracy of sensors can degrade over time, a phenomenon known as “drift,” which necessitates periodic recalibration to ensure the reliability of the collected data. This process can be unwieldy for the user and requires revolutionary software solutions for automatic and seamless calibration [8].

- Power constraints and battery life: The continuous operation of multiple sensors, coupled with the computational demands of data processing and wireless communication, places a significant strain on the limited battery capacity of small, lightweight wearable devices. Energy-efficient hardware and intelligent power management software are therefore significant for extending battery life and enhancing the user experience [3,4].

- Real-time processing demands: The aggregation and fusion of data from multiple sensors in real time require significant computational power. Embedded systems in wearable devices are typically resource-constrained, making it a challenge to perform complex data processing tasks without introducing unacceptable latency. This necessitates the development of highly efficient algorithms and software architectures that can operate within these constraints [3,4].

- Embedded software framework: A comprehensive embedded software framework tailored for multi-sensor data processing can allow the device to reach excellent levels of performance. The framework is designed to manage the intricacies of collecting and preparing data from various sensors in a resource-constrained environment [3,4].

- Real-Time synchronization and fusion: This paper details the implementation of real-time synchronization and data fusion using efficient embedded techniques. This is critical for ensuring low-latency processing and immediate feedback, which are essential for real-world applications [6].

Scope and Contributions of This Review

- Critical comparison of sensor fusion strategies highlighting accuracy, computational cost, and suitability for different wearable applications.

- Evaluation of embedded software architectures, emphasizing scalability, maintainability, and power-aware design.

- Analysis of practical challenges, including energy management, hardware limitations, and system integration issues.

- Identification of gaps in the existing literature and recommendations for future research directions, guiding both academic and industrial practitioners.

2. Embedded System Constraints in Wearable Devices

Processing, Memory and Real-Time Constraints

- High-resolution time stamping: Immediately upon acquisition within the high-priority task, each data sample from every sensor is tagged with a timestamp from a common, high-resolution hardware timer. This establishes a unified time base across all sensor data streams, which is essential for the fusion algorithm to correlate measurements correctly [17].

- RTOS synchronization primitives: The RTOS is used to manage the temporal alignment of data for processing. The main data fusion task waits on an RTOS synchronization object (such as an event flag or semaphore). The individual sensor acquisition tasks signal this object after placing new, time stamped data into their respective buffers. The fusion task is only activated to run when a complete and temporally consistent set of measurements is available from all required sensors [14,17].

3. Communication Protocols for Multi-Sensor Wearables

3.1. Wired Communication Interfaces (SPI, I2C, UART)

- Serial Peripheral Interface (SPI): This is a synchronous serial communication protocol used for high-throughput sensors like accelerometers and gyroscopes. Its full-duplex, high-speed capabilities ensure that data can be read from sensors with minimal latency, which is essential for real-time applications [18,19].

- Inter-Integrated Circuit (I2C): This two-wire protocol is used for sensors that require lower data bandwidth, such as magnetometers or environmental sensors. Its primary advantage is the ability to connect multiple slave devices to the same bus, reducing pin count and simplifying the hardware layout [18,20].

3.2. Wireless Communication Interfaces (BLE and Related Protocols)

3.3. Comparative Discussion and Design Implications

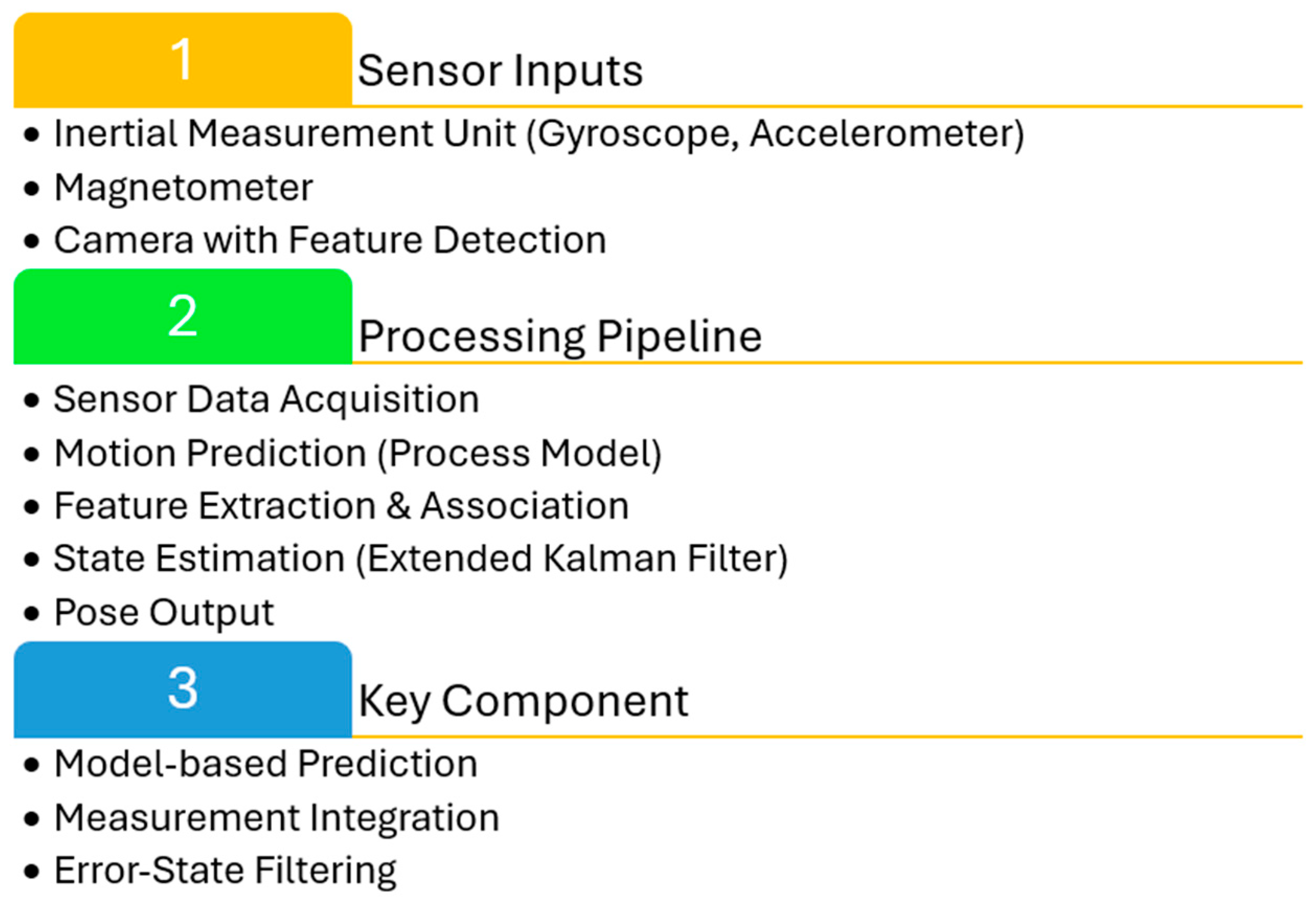

4. Sensor Fusion Techniques for Wearable Systems

4.1. Levels of Sensor Fusion (Data, Feature, Decision)

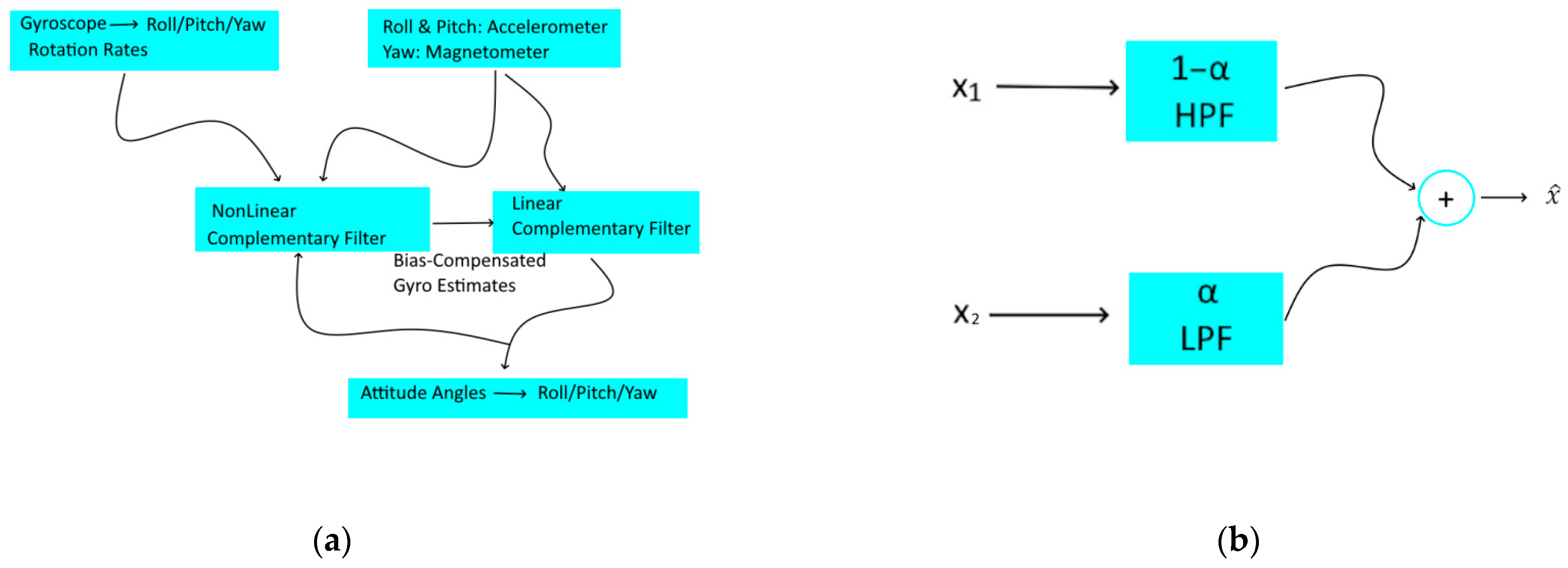

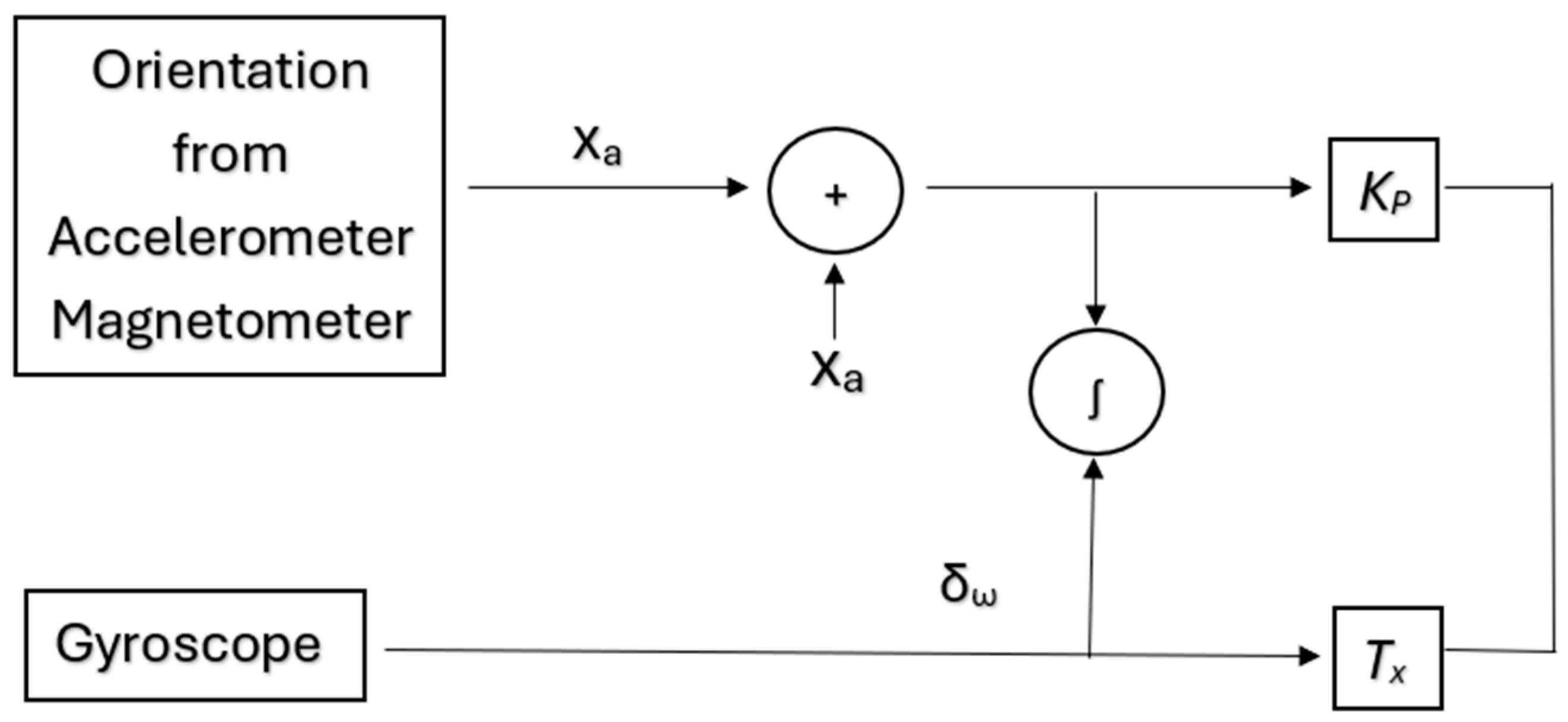

4.2. Complementary and Heuristic Filters

4.3. Kalman-Based Fusion Methods

- Prediction: The filter predicts the system’s next state based on a predefined motion model.

- Update: It corrects the predicted state using the actual measurements from the sensors, weighing the correction based on the relative uncertainty of the prediction and the measurement [34].

4.4. Comparative Analysis and Deployment Suitability

5. Embedded Software Architectures for Wearables

5.1. Bare-Metal Architectures

5.2. RTOS-Based Architectures

5.3. Comparative Analysis and Long-Term Deployment Implications

6. Power Management and Energy Harvesting in Wearables

6.1. Low-Power Design and Scheduling Techniques

6.2. Energy-Harvesting Sources and Architectures

6.3. Coordination of Multiple Energy Sources

6.4. Practical Trade-Offs and Maturity Considerations

- Dynamic frequency scaling: The microcontroller’s clock speed is adjusted based on the current computational demand. During intensive processing, such as running the fusion algorithm, the clock speed is maximized for performance. During periods of lower activity, the clock speed is reduced to save power [25,26,27,29,52,53,54,55].

- Peripheral gating: The software selectively powers down communication peripherals like SPI, I2C, and the BLE radio when they are not in active use. For instance, the BLE module is kept in a low-power state between transmissions, and sensor communication buses are only enabled when data is being actively sampled [29,53,56,57].

7. Practical Challenges, Gaps and Deployment Considerations

7.1. Manufacturing and Scalability Challenges

7.2. Reliability, Calibration and Long-Term Operation

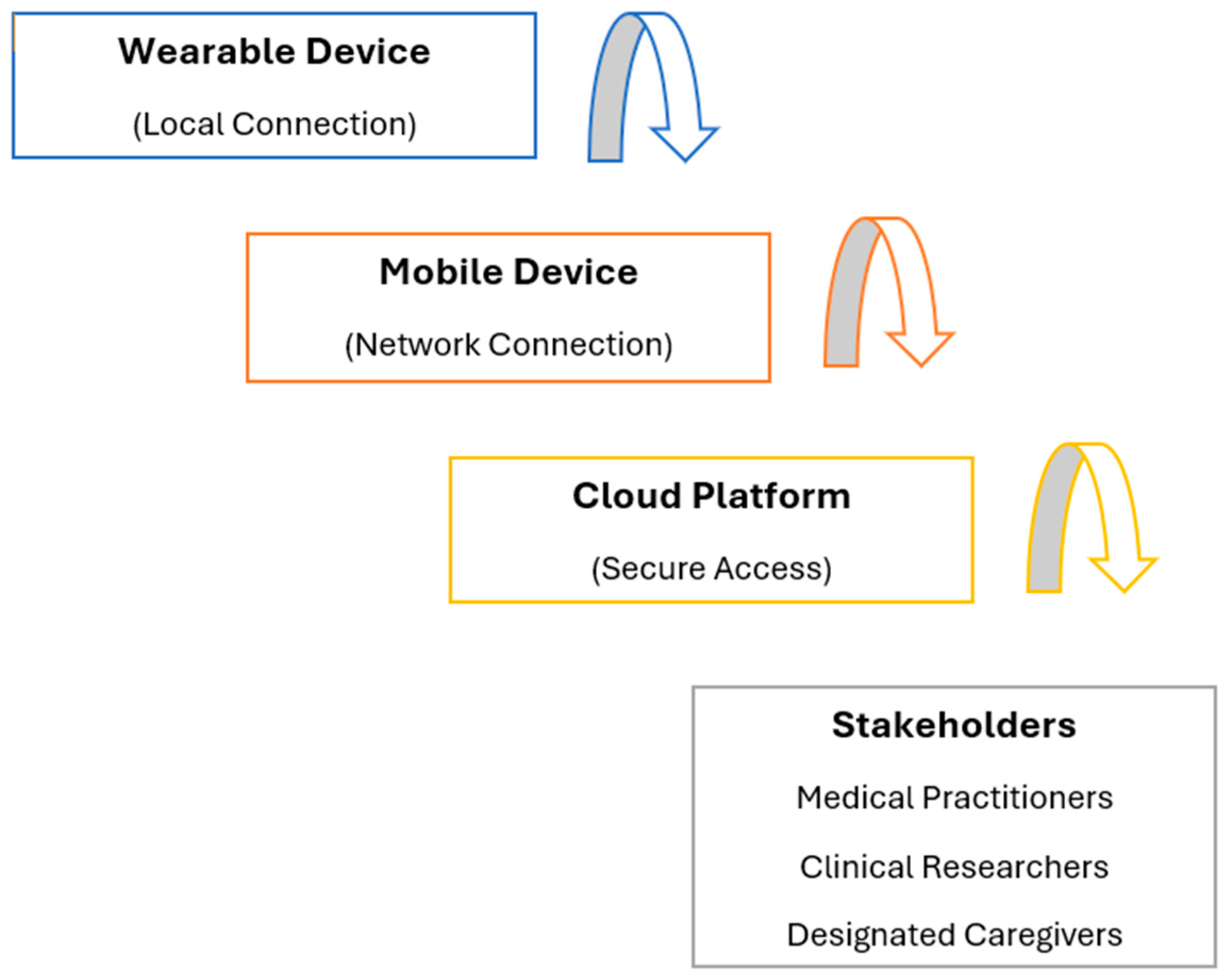

- Hardware constraints: A significant challenge in designing wearable devices is the trade-off between functionality and the physical limitations of the hardware. The primary constraint is managing power consumption to ensure reasonable battery life. Typical embedded software architectures reported in the literature are designed with an emphasis on low-power operation, utilizing efficient data buffering and power-aware processing techniques to meet the strict energy budgets of embedded systems. This ensures that the device can perform continuous real-time monitoring without frequent recharging, a critical factor for user adoption [58].

- Scalability to more sensors: Such frameworks were explicitly designed for modular scalability. Software architecture allows for the straightforward integration of additional sensors without requiring a complete system overhaul. This is achieved through a modular data acquisition and processing pipeline that can accommodate new data streams with minimal overhead. This flexibility is a key advantage, as it allows the platform to be adapted for more complex future applications, such as integrating environmental sensors alongside physiological ones [30,59,60].

- Latency and throughput in embedded processing: For the system to be effective in real-time monitoring, both latency and data throughput must be optimized. Reported case studies in the literature, which involved physiological monitoring and motion tracking, indicate that the system meets the demanding real-time processing demands of these applications. The embedded software’s real-time data acquisition, buffering, and synchronization mechanisms are efficient enough to process data from the entire sensor array with minimal delay. This ensures that the system’s outputs are timely and accurately reflect the user’s current state, which is crucial for applications requiring immediate feedback or intervention [61].

7.3. User Experience, Privacy and Security

8. Comparative Synthesis of the Literature

9. Conclusions and Future Research Directions

9.1. Key Takeaways for System Designers

9.2. Key Open Research Challenges and Future Directions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Haghi, M.; Thurow, K.; Stoll, R. Wearable Devices in Medical Internet of Things: Scientific Research and Commercially Available Devices. Healthc. Inform. Res. 2017, 23, 4–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Adeghe, E.P.; Okolo, C.A.; Ojeyinka, O.T. A review of wearable technology in healthcare: Monitoring patient health and enhancing outcomes. Open Access Res. J. Multidiscip. Stud. 2024, 7, 142–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gravina, R.; Alinia, P.; Ghasemzadeh, H.; Fortino, G. Multi-sensor fusion in body sensor networks: State-of-the-art and research challenges. Inf. Fusion 2017, 35, 68–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seneviratne, S.; Hu, Y.; Nguyen, T.; Lan, G.; Khalifa, S.; Thilakarathna, K.; Hassan, M.; Seneviratne, A. A Survey of Wearable Devices and Challenges. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tutor. 2017, 19, 2573–2620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, Y.; Ostfeld, A.E.; Lochner, C.M.; Pierre, A.; Arias, A.C. Monitoring of Vital Signs with Flexible and Wearable Medical Devices. Adv. Mater. 2016, 28, 4373–4395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- King, R.C.; Villeneuve, E.; White, R.J.; Sherratt, R.S.; Holderbaum, W.; Harwin, W.S. Application of data fusion techniques and technologies for wearable health monitoring. Med. Eng. Phys. 2017, 42, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shcherbina, A.; Mattsson, C.M.; Waggott, D.; Salisbury, H.; Christle, J.W.; Hastie, T.; Wheeler, M.T.; Ashley, E.A. Accuracy in Wrist-Worn, Sensor-Based Measurements of Heart Rate and Energy Expenditure in a Diverse Cohort. J. Pers. Med. 2017, 7, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stisen, A.; Blunck, H.; Bhattacharya, S.; Prentow, T.S.; Kjærgaard, M.B.; Dey, A.; Sonne, T.; Jensen, M.M. Smart Devices are Different: Assessing and MitigatingMobile Sensing Heterogeneities for Activity Recognition. In Proceedings of the 13th ACM Conference on Embedded Networked Sensor Systems (SenSys ‘15), Seoul, Republic of Korea, 1–4 November 2015; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2015; pp. 127–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atallah, L.; Lo, B.; King, R.; Yang, G.-Z. Sensor Positioning for Activity Recognition Using Wearable Accelerometers. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Circuits Syst. 2011, 5, 320–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Gao, R.X.; Freedson, P.S. Computational methods for estimating energy expenditure in human physical activities. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2012, 44, 2138–2146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Bicocchi, N.; Mamei, M.; Zambonelli, F. Detecting activities from body-worn accelerometers via instance-based algorithms. Pervasive Mob. Comput. 2010, 6, 482–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parkka, J.; Ermes, M.; Korpipaa, P.; Mantyjarvi, J.; Peltola, J.; Korhonen, I. Activity classification using realistic data from wearable sensors. IEEE Trans. Inf. Technol. Biomed. 2006, 10, 119–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laplante, P.A.; Ovaska, S.J. Real-Time Systems Design and Analysis: Tools for the Practitioner, 4th ed.; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2012; pp. 79–82, 109–110. [Google Scholar]

- Cooling, J. Real-Time Operating Systems: Book 1—The Theory; Lindentree Associates: Burford, UK, 2017; pp. 37–75, 280–285. [Google Scholar]

- White, E. Making Embedded Systems: Design Patterns for Great Software; O’Reilly Media: Sebastopol, CA, USA, 2011; pp. 176–182. [Google Scholar]

- Hasan, K.F.; Wang, C.; Feng, Y.; Tian, Y.-C. Time synchronization in vehicular ad-hoc networks: A survey on theory and practice. Veh. Commun. 2018, 14, 39–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schöpping, T.; Kenneweg, S.; Hesse, M.; Rückert, U. μRT: A lightweight real-time middleware with integrated validation of timing constraints. Front. Robot. AI 2023, 10, 1081875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leens, F. An introduction to I2C and SPI protocols. IEEE Instrum. Meas. Mag. 2009, 12, 8–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, C.-W.; Yu, H.-C.; Liao, Y.-C. Verification of SPI Protocol Using Universal Verification Methodology for Modern IoT and Wearable Devices. Electronics 2025, 14, 837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kher, R.K.; Patel, D.M. A comprehensive review on wearable health monitoring systems. Open Biomed. Eng. J. 2021, 15, 213–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baiense, J.; Zdravevski, E.; Coelho, P.; Pires, I.M.; Velez, F.J. Driving Healthcare Monitoring with IoT and Wearable Devices: A Systematic Review. ACM Comput. Surv. 2025, 57, 294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koulouras, G.; Katsoulis, S.; Zantalis, F. Evolution of Bluetooth Technology: BLE in the IoT Ecosystem. Sensors 2025, 25, 996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Villa, M.; Casilari, E. Wearable Fall Detectors Based on Low Power Transmission Systems: A Systematic Review. Technologies 2024, 12, 166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghasemzadeh, H.; Amini, N.; Saeedi, R.; Sarrafzadeh, M. Power-aware computing in wearable sensor networks: An optimal architecture design. IEEE Trans. Mob. Comput. 2015, 14, 800–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, M.; Yao, Y.; Wang, Y.; Wang, B.; Wang, P.; Wang, Y.; Dai, J.; Liu, S.; Torres, J.F.; Cheng, W.; et al. Wearable power management system enables uninterrupted battery-free data-intensive sensing and transmission. Nano Energy 2023, 107, 108107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majumder, S.; Mondal, T.; Deen, M.J. Wearable Sensors for Remote Health Monitoring. Sensors 2017, 17, 130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaikh, F.K.; Zeadally, S. Energy harvesting in wireless sensor networks and internet of things: A review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2016, 55, 1041–1054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luna, R.; Islam, S.A. Security and Reliability of Safety-Critical RTOS. SN Comput. Sci. 2021, 2, 356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rault, T.; Bouabdallah, A.; Challal, Y. Energy Efficiency in Wireless Sensor Networks: A Top-Down Survey. Comput. Netw. 2014, 67, 104–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, S.; Irfan, S.; Kiran, N.; Masood, N.; Anjum, N.; Ramzan, N. Remote Health Monitoring Systems for Elderly People: A Survey. Sensors 2023, 23, 7095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, R.C.; Yih, C.-C.; Su, K.L. Multisensor fusion and integration: Approaches, applications, and future research directions. IEEE Sens. J. 2002, 2, 107–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narkhede, P.; Poddar, S.; Walambe, R.; Ghinea, G.; Kotecha, K. Cascaded Complementary Filter Architecture for Sensor Fusion in Attitude Estimation. Sensors 2021, 21, 1937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, S.; Li, X.; Zhang, S.; Jian, Z.; Duan, H.; Wang, Z. A review: State estimation based on hybrid models of Kalman filter and neural network. Syst. Sci. Control Eng. 2023, 11, 2173682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kok, M.; Hol, J.D.; Schön, T.B. Using Inertial Sensors for Position and Orientation Estimation. Found. Trends Signal Process. 2017, 11, 1–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, D.L.; Llinas, J. An introduction to multisensor data fusion. Proc. IEEE 1997, 85, 6–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-de-Villa, S.; Casillas-Pérez, D.; Jiménez-Martín, A.; García-Domínguez, J.J. Inertial sensors for human motion analysis: A comprehensive review. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2023, 72, 4006439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kok, M.; Schön, T.B. A fast and robust algorithm for orientation estimation using inertial sensors. IEEE Signal Process. Lett. 2019, 26, 1533–1537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kok, M.; Schön, T.B. Magnetometer calibration using inertial sensors. IEEE Sens. J. 2016, 16, 5679–5689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazarahari, M.; Rouhani, H. Sensor fusion algorithms for orientation tracking via magnetic and inertial measurement units: An experimental comparison survey. Inf. Fusion 2021, 76, 8–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Z.-A.; Hu, Y.; Yu, J.; Na, Z. Extended Kalman Filter for Real Time Indoor Localization by Fusing WiFi and Smartphone Inertial Sensors. Micromachines 2015, 6, 523–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sreelekshmy, I.; Resmi, R. A review on real time MEMS sensor fusion. Int. Res. J. Eng. Technol. (IRJET) 2020, 7, 21–23. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, H.; Schall, M.C.; Fethke, N.B. Measuring upper arm elevation using an inertial measurement unit: An exploration of sensor fusion algorithms and gyroscope models. Appl. Ergon. 2020, 89, 103187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azarbeik, M.M.; Razavi, H.; Merat, K.; Salarieh, H. Augmenting inertial motion capture with SLAM using EKF and SRUKF data fusion algorithms. Measurement 2023, 222, 113690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poulose, A.; Kim, J.; Han, D.S. A Sensor Fusion Framework for Indoor Localization Using Smartphone Sensors and Wi-Fi RSSI Measurements. Appl. Sci. 2019, 9, 4379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, H.; Haile, M.A.; Wang, Y. Robust extended Kalman filtering for systems with measurement outliers. IEEE Control Syst. Lett. 2021, 30, 795–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nathan, V.; Jafari, R. Particle filtering and sensor fusion for robust heart rate monitoring using wearable sensors. IEEE J. Biomed. Health Inform. 2018, 22, 1834–1846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- John, A.; Wang, H.; Cardiff, B.; Parhi, K.K.; John, D. Multimodal fusion for robust respiratory rate estimation in wearable sensing. Inf. Fusion 2025, 123, 103253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, W.; Wang, J.; Wang, Y. Design of an Embedded System for Wearable Physiological Monitoring. IEEE Access 2016, 4, 3940–3950. [Google Scholar]

- Zalizovskyi, M.; Huzynets, N. Comparative analysis between real-time operating systems and supercycles. Electron. Inf. Technol. 2024, 26, 33–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labrosse, J.J. MicroC/OS-II: The Real-Time Kernel, 2nd ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2002; pp. 35–45. [Google Scholar]

- Banbury, C.; Zhou, C.; Fedorov, I.; Matas, R.; Thakker, U.; Gope, D.; Janapa Reddi, V.; Mattina, M.; Whatmough, P. MicroNets: Neural Network Architectures for Deploying TinyML Applications on Commodity Microcontrollers. In Proceedings of the Machine Learning and Systems (MLSys), Virtual, 5–9 April 2021; Volume 3, pp. 517–532. [Google Scholar]

- Maioli, A.; Quinones, K.A.; Ahmed, S.; Alizai, M.H.; Mottola, L. Dynamic Voltage and Frequency Scaling for Intermittent Computing. ACM Trans. Sens. Netw. 2025, 21, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zidar, J.; Matić, T.; Aleksi, I.; Hocenski, Ž. Dynamic Voltage and Frequency Scaling as a Method for Reducing Energy Consumption in Ultra-Low-Power Embedded Systems. Electronics 2024, 13, 826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pillai, P.; Shin, K.G. Real-time dynamic voltage scaling for low-power embedded operating systems. In Proceedings of the Eighteenth ACM Symposium on Operating Systems Principles (SOSP ‘01), Banff, AL, Canada, 21–24 October 2001; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2001; pp. 89–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mittal, S. A survey of techniques for improving energy efficiency in embedded computing systems. Int. J. Comput. Aided Eng. Technol. 2014, 6, 440–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dias, D.; Cunha, J.P.S. Wearable Health Devices—Vital Signs Monitoring, Systems and Technologies. Sensors 2018, 18, 2414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vafeas, A.; Biswas, M.I.; Fafoutis, X.; Elsts, A.; Craddock, I.; Piechocki, R.; Oikonomou, G. Wearable devices for digital health: The SPHERE Wearable 3. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Embedded Wireless Systems and Networks (EWSN 2020), Lyon, France, 17–18 February 2020; Junction Publishing: Junction, TX, USA, 2020; pp. 236–241. [Google Scholar]

- Covi, E.; Donati, E.; Liang, X.; Kappel, D.; Heidari, H.; Payvand, M.; Wang, W. Adaptive extreme edge computing for wearable devices. Front. Neurosci. 2021, 15, 611300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pantelopoulos, A.; Bourbakis, N.G. A survey on wearable sensor-based systems for health monitoring and prognosis. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man Cybern.—Part C Appl. Rev. 2010, 40, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinheiro, G.P.M.; Miranda, R.K.; Praciano, B.J.G.; Santos, G.A.; Mendonça, F.L.L.; Javidi, E.; da Costa, J.P.J.; de Sousa, R.T., Jr. Multi-sensor wearable health device framework for real-time monitoring of elderly patients using a mobile application and high-resolution parameter estimation. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2022, 15, 750591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez, A.J.; Zeadally, S. Recent Advances in Wearable Sensing Technologies. Sensors 2021, 21, 6828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irfan, M.; Dalai, S.; Trslic, P.; Riordan, J.; Dooly, G. LSAF-LSTM-Based Self-Adaptive Multi-Sensor Fusion for Robust UAV State Estimation in Challenging Environments. Machines 2025, 13, 130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erhan, L.; Ndubuaku, M.; Di Mauro, M.; Song, W.; Chen, M.; Fortino, G.; Bagdasar, O.; Liotta, A. Smart anomaly detection in sensor systems: A multi-perspective review. Inf. Fusion 2021, 67, 64–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valade, A.; Acco, P.; Grabolosa, P.; Fourniols, J.-Y. A Study about Kalman Filters Applied to Embedded Sensors. Sensors 2017, 17, 2810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Chen, Y.; Hao, S.; Peng, X.; Hu, L. Deep learning for sensor-based activity recognition: A survey. Pattern Recognit. Lett. 2019, 119, 3–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaukat, N.; Ali, A.; Javed Iqbal, M.; Moinuddin, M.; Otero, P. Multi-Sensor Fusion for Underwater Vehicle Localization by Augmentation of RBF Neural Network and Error-State Kalman Filter. Sensors 2021, 21, 1149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Reference/System | Fusion Level | Sensor Types Used | Sensor Configuration | Feature Domain | Fusion Strategy | Classifier/Algorithm | Application Area |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Atallah et al. [9] | Feature-level | Accelerometer (×3) | Wrist, Waist, Ankle | Time domain | Cooperative | k-NN (k = 1) | Activity Recognition |

| Liu et al. [10] | Feature-level | Accelerometer | Wrist, Waist | Time and frequency | Complementary | SVM, DT | Physical Activity Estimation |

| Bicocchi et al. [11] | Decision-level | Accelerometer | Pocket (Mobile Phone) | Time domain | Cooperative | Instance-based, k-NN | Activity Recognition |

| Pärkkä et al. [12] | Feature-level | Accelerometer + Physio sensors | Wrist | Time domain | Complementary | SVM | Activity Monitoring |

| Reference/System | Accuracy (%) | Data Window Size | Evaluation Dataset |

|---|---|---|---|

| Atallah et al. [9] | 91% | 1 s window, 50% overlap | Custom Dataset |

| Liu et al. [10] | 93.2% | 2 s window, 50% overlap | Custom Dataset |

| Bicocchi et al. [11] | ~75% | 3 s window | Real-Life Activity Dataset |

| Pärkkä et al. [12] | N/A | 2–5 s window | Custom Dataset |

| Aspect | Traditional (e.g., EKF Fuse) | RTOS + Ring Buffer Pipeline | Middleware (μRT, etc.) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Data Capture Triggering | Polling, periodic tasks | Interrupt-driven, high-priority acquisition | ISR → topic publish (ring buffer enqueued) |

| 2. | Buffer Structure | Fixed buffers, double-buffer | Circular FIFO per sensor | Ring buffers in publish–subscribe topics |

| 3. | Timestamping | Often software layer | High-resolution hardware timer at acquisition task | Timestamp at publish based on message info time |

| 4. | Synchronization Mechanism | Manual polling or heuristics | RTOS semaphores/events combining all sensors | Topic subscriber triggered when all timestamps align |

| 5. | Resilience to Processing Load | Minimal: buffer overflows possible | Buffers decouple fusion; ISR always handles capture | Topic logic drops or reschedules based on buffer age |

| 6. | Maturity/Usage | Widely deployed in avionics/UAVs (EKF pipelines) | Common in embedded sensor systems (FreeRTOS, VxWorks) | Emerging in µRT and DDS frameworks |

| Protocol | Use Case | Device | Advantages | Latency/Throughput | Wiring |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SPI | High-speed motion sensors | Accelerometer, gyroscope | Full-duplex, low latency | ≥10 Mbps | 4 wires |

| I2C | Mid/low bandwidth sensors | Magnetometer, temperature, pressure | Multi-slave, 2-wire simplicity | 100 kbps–5 Mbps | 2 wires |

| UART | Serial modules and debugging | GPS, console | Simple P2P, minimal hardware | ≤1 Mbps | 2 wires |

| BLE | Wireless data transmission | Gateway, smartphone | Ultra-low power, burst transfers | 100 kbps–1 Mbps | Wireless |

| Fusion Method | Computational Cost | Maturity Level | Key Strength | Typical Applications | Main Limitation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Linear Complementary Filter | Low | High (widely deployed) | Low computational overhead and minimal power consumption, simple implementation | Basic orientation tracking, excellent for low-power wearables | Limited accuracy in highly dynamic or nonlinear motion |

| Cascaded CF ([32]) | Medium | Medium | Improved drift compensation without heavy computation | Robust attitude estimation in wearables/robots, good for mid-range devices | Requires empirical tuning, limited adaptivity |

| Extended Kalman Filter | High | High (industry-grade) | High accuracy, uncertainty modeling, sensor redundancy handling | Navigation, motion capture, GPS-denied environments, suitable for high-end wearables | High computational complexity and increased power consumption |

| Algorithm Type | Pros | Cons | Typical Error | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | EKF (a + g + m) | Long-term drift correction; widely used, balance of accuracy/compute | Nonlinear model; requires tuning Jacobians | ~2–4° orientation |

| 2. | Complementary filter + bias | Computationally efficient, robust | Less flexible to complex dynamics | <3–4° peak error |

| 3. | UKF/SR-UKF | Better nonlinear handling, more accuracy | Higher compute requirement | Slightly better accuracy |

| 4. | Particle filter (PF) | Handles non-Gaussian noise well | Highest computational cost | Comparable |

| Reference | Fusion Method | Sensor Set | Key Benefits |

|---|---|---|---|

| A Review on Multisensor Data Fusion for Wearable Health Monitoring [3] | Generic multi-sensor fusion | accelerometer, gyroscope, magnetometer, physiological sensors | Robustness to sensor faults, compensates unreliable input |

| Extended Kalman Filter for Real-Time Indoor Localization by Fusing WiFi and Smartphone Inertial Sensors [40] | EKF fusion | gyroscope + accelometer + magnetometer + Wi-Fi RSSI | Corrects drift, high orientation and positional accuracy |

| Robust Extended Kalman Filtering for Systems with Measurement Outliers [45] | EKF variant | IMU data with outlier detection | Enhanced robustness to disturbances and sensor anomalies |

| Particle Filtering and Sensor Fusion for Robust Heart Rate Monitoring Using Wearable Sensors [46] | Particle filter + fusion | PPG + IMU motion data | Excellent noise rejection, reliable heart-rate estimation |

| Multimodal Fusion for Robust Respiratory Rate Estimation in Wearable Sensing [47] | Sequential fusion | respiratory + motion sensors | Smooth output stream, reduced noise for clean physiological features |

| Aspect | Bare-Metal Super-Loop | RTOS-Based Framework |

|---|---|---|

| Memory footprint | Minimal (<2 KB) | Small but larger (2–10 KB) |

| Task ordering | Manual loop or interrupts | Preemptive, priority-based scheduler |

| Real-time guarantees | Manual timing, non-deterministic | Deterministic scheduling |

| Concurrency handling | ISR-heavy, complex scaling | Native task synchronization |

| Modularity | Code entangled | High modularity via tasks |

| Scalability | Poor beyond few sensors | High, modular task expansion |

| Power management | Sleep in loop, custom code | Integrated (tickless idle, sleep hooks) |

| Maintainability | Degrades rapidly with complexity | High for long-term development |

| Overall suitability | Prototyping, simple devices | Recommended for deployable multi-sensor wearables |

| Technique/Approach | System Level | Key Idea | Advantages | Limitations | Technology Maturity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tickless RTOS Idle [29] | Software (RTOS) | Suppresses periodic OS ticks during idle periods | Significant reduction in idle power consumption, easy RTOS integration | Limited benefit under high task activity | High (commercially deployed) |

| Duty Cycling [57] | Software/System | Periodic activation/deactivation of sensors and peripherals | Simple to implement, effective for low-duty workloads | Can increase latency and reduce responsiveness | High |

| Dynamic Voltage and Frequency Scaling (DVFS/DVS) [53,54] | Hardware/Software | Adjusts CPU voltage and frequency based on workload | Large energy savings under variable load | Requires hardware support and careful timing analysis | Medium–High |

| Peripheral Power Gating [55,56] | Hardware/Software | Shuts down unused peripherals and buses | Reduces leakage and dynamic power | Reinitialization overhead | High |

| Energy-Aware Task Scheduling | Software (RTOS) | Schedules tasks based on energy constraints | Improves system-wide efficiency | Increased scheduler complexity | Medium |

| Event-Driven Processing | System | Activates processing only on relevant events | Minimizes unnecessary computation | Not suitable for continuous sensing | Medium |

| Energy Harvesting Integration [52] | System wearables | Uses ambient energy (motion, thermal, solar) | Extends operational lifetime | Intermittent and unpredictable energy | Low–Medium (experimental) |

| Multi-Source Power Coordination | System | Combines battery and harvested energy sources | Improved resilience and autonomy | Complex control logic | Low (research stage) |

| System | Sensor Coverage | Power Constrains | Latency and Throughput | Scalability | Communication/Compute Architecture |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pantelopoulos & Bourbakis (2010) [59] | Multiple physiological sensors (ECG, SpO2) | High battery efficiency, low–power focus | Real-time vital sign detection but limited throughput benchmarks | Modular wearable prototypes | Early body area network, simple wireless |

| Remote Health Monitoring for Elderly (2023) [30] | Bio-sensors, environmental, actigraphy | Fog-enabled to reduce power and latency | Latency-sensitive via edge/fog—~140 ms sensing-to-actuation latency | Easily extensible gateway-based systems | IoT-edge-cloud layered architecture |

| Adaptive Extreme Edge Computing (2021) [58] | Neuromorphic sensor fusion capabilities | Ultra-low power, memristive/CMS architectures | Designed for minimal latency, low footprint | Supports adaptive, incremental sensor additions | On-device edge compute, minimal offloading |

| Method | Accuracy | Computation | Real-Time Viability | Robustness | Embedded Suitability | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | EKF | High (model-dependent) | Moderate–High | Possibly constrained | Sensitive to model/data | Moderate |

| 2. | Complementary Filter | Moderate | Low | Real-time viable | Robust but less accurate | Excellent |

| 3. | Deep Learning/LSTM | Very high in complex dynamic environments | Very High | Poor for real-time embedded | Good adaptability | Limited embedded readiness |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Toptsis, M.; Karkanis, N.; Giannakoulas, A.; Kaifas, T. A Review of Embedded Software Architectures for Multi-Sensor Wearable Devices: Sensor Fusion Techniques and Future Research Directions. Electronics 2026, 15, 295. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics15020295

Toptsis M, Karkanis N, Giannakoulas A, Kaifas T. A Review of Embedded Software Architectures for Multi-Sensor Wearable Devices: Sensor Fusion Techniques and Future Research Directions. Electronics. 2026; 15(2):295. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics15020295

Chicago/Turabian StyleToptsis, Michail, Nikolaos Karkanis, Andreas Giannakoulas, and Theodoros Kaifas. 2026. "A Review of Embedded Software Architectures for Multi-Sensor Wearable Devices: Sensor Fusion Techniques and Future Research Directions" Electronics 15, no. 2: 295. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics15020295

APA StyleToptsis, M., Karkanis, N., Giannakoulas, A., & Kaifas, T. (2026). A Review of Embedded Software Architectures for Multi-Sensor Wearable Devices: Sensor Fusion Techniques and Future Research Directions. Electronics, 15(2), 295. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics15020295