As a high-performance model in the YOLO series, YOLOv11 has made significant strides in balancing detection accuracy and efficiency by integrating the novel C3k2 module and the C2PSA spatial attention mechanism. From an architectural perspective, the proposed network is organized into three distinct operational stages: the backbone (responsible for feature extraction), the neck, and the detection head. The backbone utilizes a cutting-edge Cross Stage Partial (CSP) configuration, anchored by the C3k2 block, to ensure superior efficiency in extracting features. In the Neck, an improved PANet (Path Aggregation Network) structure facilitates both bottom-up multi-scale feature fusion and top-down interaction between semantic and fine-grained features. Features from different scales are fused via Concatenation operations, while the novel C2PSA spatial attention module enhances the complementarity between semantic information and fine-grained details. The Head utilizes an efficient Decoupled Head, where each sub-head contains independent classification and regression branches. This design accelerates model convergence while simultaneously boosting detection accuracy. Consequently, we utilized YOLOv11n as the foundational baseline for this work. However, notwithstanding its inherent strengths, the standard model exhibits significant limitations when applied to aerial photography, particularly struggling to accurately identify minute targets against chaotic or intricate backgrounds.

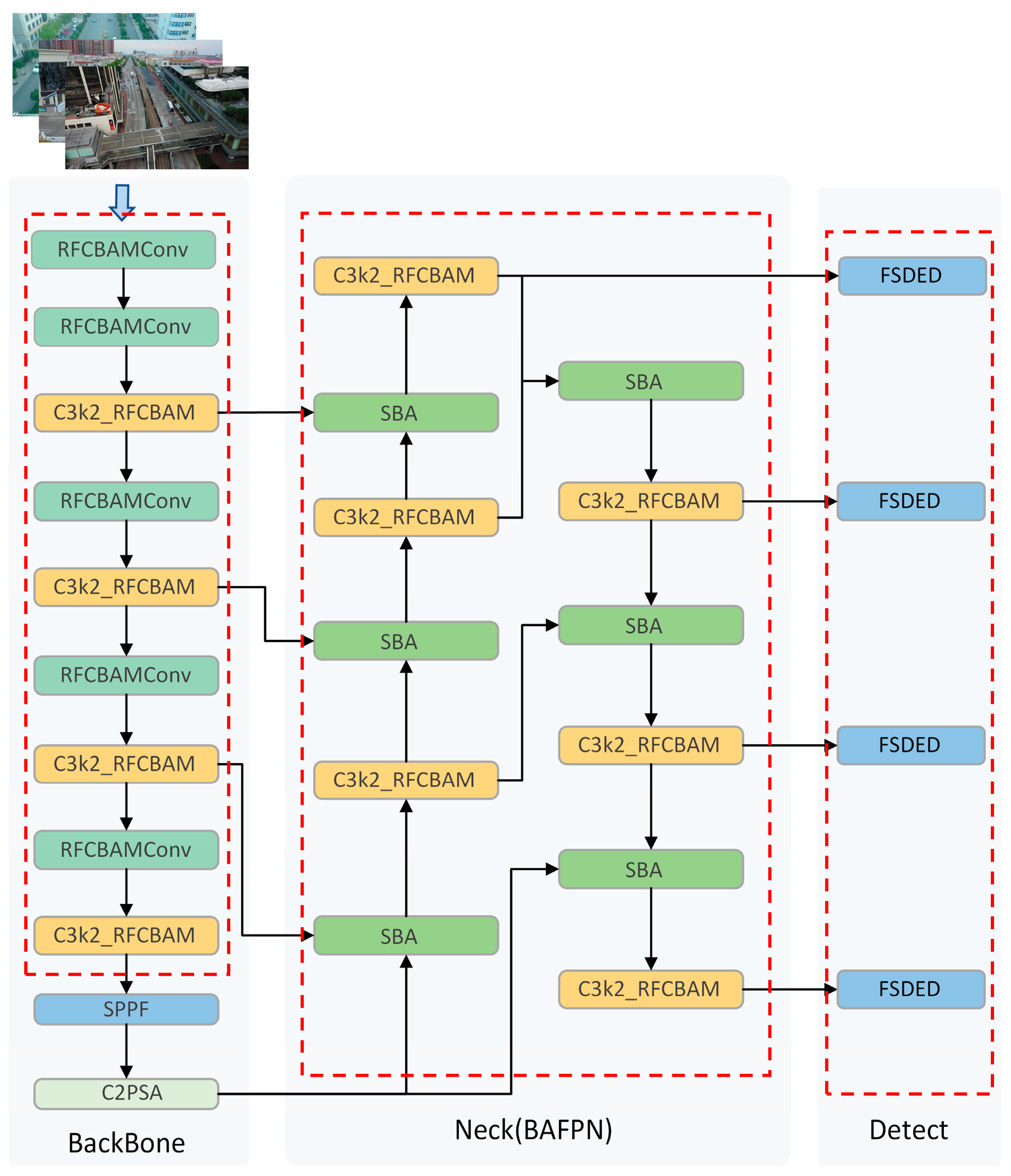

To enhance multi-scale object detection performance, particularly when addressing the challenges of small objects and complex background interference, this paper proposes an improved BFRI-YOLO architecture, with its overall framework illustrated in

Figure 1. While preserving the efficient inference characteristics of the YOLO series networks, this method designs multiple improved modules to target specific issues prevalent in small object detection within complex scenarios, such as the susceptibility to edge detail loss, insufficient shallow-level semantics, and simplistic feature fusion methods. In the Backbone, we introduce the RFCBAMConv and C3k2-RFCBAM structures. By combining lightweight convolution with attention mechanisms, this approach effectively enhances the network’s joint modeling capability of local details and global context, thereby maintaining strong robustness against complex background interference. In the Neck, we design the BAFPN module. Building upon the traditional pyramid network, it explicitly introduces a P2 layer and integrates the IFU and SBA mechanisms to realize dynamic interaction and selective enhancement between shallow edge features and deep semantic features. This enhances the boundary perception and spatial discrimination capabilities for small objects. Additionally, in the Head, we propose the FSDED structure. By leveraging multi-scale feature sharing alongside convolutional coordination, this mechanism reinforces information alignment across detection heads. Consequently, it elevates both the positioning precision and categorization success rates for minute targets. Furthermore, to refine the bounding box regression specifically for small targets situated in cluttered environments, we adopt an enhanced Inner-WIoU as our loss metric. This technique integrates a spatial weighting mechanism into the standard IoU framework, compelling the predicted box to concentrate its attention on the target’s core area, thereby mitigating localization errors common in small object scenarios. This alleviates localization errors caused by boundary ambiguity while enhancing overall regression stability.

3.1. BAFPN

In the task of small object detection within complex scenes, conventional Feature Pyramid Networks (FPN, PAN), while effective for multi-scale targets, typically commence feature aggregation from the P3 layer, neglecting the high-resolution and fine-grained information present in P2. This design leads to imprecise bounding box localization due to the loss of edge and positional information in shallow features during downsampling. Moreover, the lack of deep semantic support in these features results in frequent false positives and missed detections of small objects. Furthermore, most existing methods rely on static fusion strategies (upsampling and concatenation), which lack dynamic modeling of the complementary relationship between different feature levels, potentially introducing redundant or conflicting information and compromising detection accuracy and stability.

To counteract these shortcomings, this paper introduces a Balanced Adaptive Feature Pyramid Network (BAFPN). This structure explicitly incorporates the P2 layer into the feature pyramid and is optimized by integrating two core modules: IFU and SBA [

25]. As depicted in

Figure 2, the IFU module utilizes an interactive update mechanism to realize dynamic complementarity between shallow edge details and deep semantic information, which significantly enhances the localization and discriminative capabilities for small objects. Concurrently, the SBA module selectively amplifies boundary regions, effectively suppressing interference from complex backgrounds, thereby strengthening the contour perception and spatial representation of minute targets. Through the synergistic action of these two components, BAFPN maximizes the utility of both shallow and deep features while maintaining detection efficiency, providing a more robust feature expression for small object detection in complex environments.

As illustrated in

Figure 2, the internal components of the IFU module are defined by generic input features

and

. Here,

and

serve as mathematical placeholders representing positional and semantic feature paths, respectively. We apply convolution and Sigmoid activation to these two paths to obtain the attention weights:

Subsequently, the features are enhanced, respectively, using the interactive update formulas:

where

denotes element-wise multiplication,

epresents the Sigmoid function, and Upsample refers to the upsampling operation. This module effectively supplements the contextual information of distant small objects while preserving semantic consistency.

To optimize the feature fusion stage, this study introduces the SBA module (

Figure 3), which instantiates the IFU logic for specific feature alignment. In this context, we map the fine-grained positional features

to

and the deep semantic features

to

. By exploiting their complementary nature, this module significantly bolsters detection performance for small objects. Structurally, the SBA comprises two parallel IFU units designed to interactively augment boundary and spatial information, respectively; this process is mathematically formulated in Equation (4). Subsequently, the final fused features are synthesized through a concatenation operation followed by a convolution layer, as defined in Equation (5).

This module effectively mitigates the impact of complex background interference on the recognition of edge details for small objects while maintaining detection efficiency.

3.2. FSDED

When identifying minute targets amidst cluttered backgrounds, the architectural configuration of the detection head acts as a critical determinant of the model’s overall precision. Traditional detection heads in the YOLO series typically adopt a decoupled branch structure, where each feature layer independently constructs convolutional branches to predict targets. However, this approach faces two primary limitations when handling small objects. First, the lack of a shared collaboration mechanism significantly increases the model’s computational and parameter overhead. The independently constructed detection branches lead to a substantial amount of redundant operations during feature extraction. Second, the perception capability for distant, tiny objects is extremely limited. The absence of multi-scale semantic interaction makes it difficult for the model to extract effective discriminative information from blurry shallow features, resulting in insufficient classification and localization accuracy for distant targets. To address the aforementioned issues, this paper proposes a Four-Scale Shared Detail-Enhanced Detection Head (FSDED). Illustrated in

Figure 4, the fundamental design philosophy of the FSDED unit centers on integrating a shared convolutional framework with Detail-Enhanced Convolution (DEConv). This synthesis facilitates effective cross-scale resource sharing and the retention of fine-grained details, which subsequently elevates the model’s precision and stability in identifying small targets.

First, for the input multi-scale features P2, P3, P4, and P5, we apply Group Normalization (GN) [

26] to each scale to ensure the stability of features with varying distributions under small-batch training.

Secondly, following the shared convolution, this paper introduces the Detail-Enhanced Convolution (DEConv) [

27]. Its core mechanism lies in modeling texture and structural information at different levels through parallel detail and structural branches.

where

and

denote the structural features and detail features, respectively;

and

are the corresponding weight parameters; and

represents the convolution operation. This mechanism ensures that the detection head enhances the representation capability of local details while preserving multi-scale semantic information. Finally, after being processed by shared convolution and DEConv, features from all scales are uniformly fed into the classification and regression branches to achieve end-to-end detection prediction:

By adopting this consolidated decoding approach, we minimize calculation redundancy and guarantee consistent feature representation across multiple scales. This strategy is pivotal for elevating the detection efficacy of minute targets. Empirical evidence confirms that the FSDED module substantially bolsters the model’s perceptual sensitivity and precision for small objects, all without imposing a significant burden on parameter size or computational load.

3.3. C3K2_RFCBAM

In aerial small object detection tasks, the ability of the network to efficiently extract discriminative features is paramount, particularly given the generally small scale of targets and the frequent presence of complex background interference. While the C3k2 module in YOLO series models maintains a lightweight design and computational efficiency, its internal standard Bottleneck structure relies solely on stacking convolutions for feature modeling. Consequently, it lacks sufficient attention to multi-scale context and salient regions. This limitation renders the model susceptible to false and missed detections in complex backgrounds. To address this, this paper integrates RFCBAMConv into the C3k2 module of YOLOv11, replacing the standard convolution.

The RFConv module [

28] addresses scale variation issues by utilizing convolutions with multiple receptive fields, which is crucial for stabilizing performance against complex backgrounds. On the other hand, CBAM [

29] refines feature extraction by recalibrating channel and spatial weights, ensuring the network prioritizes salient regions over background distractions. Building on this foundation, the proposed RFCBAMConv module, as illustrated in

Figure 5, integrates the strengths of both RFConv and CBAM. It achieves the unification of multi-scale modeling and salient feature selection.

We replace the standard Bottleneck structure in the original C3k2 with the RFCBAM-Bottleneck, effectively embedding the RFCBAMConv module after the convolutional layer to achieve lightweight, attention-enhanced feature learning. The overall improved structure is illustrated in

Figure 6. Specifically,

Figure 6a depicts the original C3k2 structure, while

Figure 6b shows the improved C3k2-RFCBAM structure.

Figure 6c,d illustrates the comparison between the standard Bottleneck and the RFCBAM-Bottleneck. Compared to the original C3k2, the C3k2-RFCBAM demonstrates significant advantages in the following aspects: First, leveraging the multi-receptive field mechanism of RFConv, the improved module can better model features of targets at varying scales, thereby enhancing the detection capability for distant small objects. Second, by integrating the channel and spatial attention mechanisms of CBAM, the network is guided to focus more intently on key target regions while suppressing irrelevant background information in complex scenes. This significantly improves the specificity of feature selection. By effectively controlling parameter count, the lightweight RFCBAMConv maintains high computational efficiency, ensuring the model’s suitability for real-time deployment.

3.4. Inner-WIoU

CIoU Loss is implemented within the YOLOv11 framework to manage the bounding box regression task, focusing on optimizing the spatial location and dimensionality of the output predictions. This metric represents a significant advancement over legacy loss functions, such as IoU, by explicitly integrating penalty terms related to both the centroid distance and the aspect ratio discrepancy. The full CIoU loss function is formally expressed as follows:

In this expression, quantifies the spatial displacement between the geometric centers of the prediction and the ground truth box. To ensure shape alignment, is introduced as a constraint term for aspect ratio deviations. The coefficient is used to balance the contribution of the aspect ratio cost relative to the distance loss, while specifically evaluates the consistency of the aspect ratios.

To further optimize bounding box regression, the WIoU series of methods was proposed. WIoU-v1 introduces sample weights into the loss function to assign varying degrees of importance to high-quality and low-quality predicted boxes. WIoU-v3 [

22], conversely, employs a dynamic non-monotonic gradient allocation strategy to achieve adaptive weight adjustment via the outlier degree

and the gain function

. The outlier degree is defined as the ratio of the current sample’s IoU loss to the historical mean:

High-quality samples are characterized by a small

, in contrast to large

values which flag a marked divergence between the regression result and the ground truth. In this context,

denotes the specific loss of the current instance, and

corresponds to the historical moving mean of the loss.

where

and

hyperparameters used to control the shape of the gradient curve. The form of the WIoU-v3 loss function is expressed as follows:

WIoU-v3 incorporates bounding box center offset, IoU loss, and a dynamic weight allocation mechanism. It enhances detection accuracy and robustness in complex scenarios while ensuring fast convergence speed. Building upon these methods, to further improve the localization precision for small and dense objects, researchers proposed Inner-IoU [

30]. As illustrated in

Figure 7, The central concept involves calculating the Inner-IoU score based on the geometric relationship between the regression output and the ground-truth label. By measuring the degree of pixel overlap within the bounding boxes, it more precisely constrains the alignment between the prediction and the ground truth. Its loss function can be expressed as follows:

Specifically, the inner box coordinates are derived by scaling the original bounding box with a ratio factor

$ratio

$. Let the center of the ground truth box be

and its size be

. The width and height of the inner ground truth box are computed as follows:

Similarly, the inner predicted box is scaled by the same factor. The inner intersection is then calculated based on these scaled boxes. In our experiments, we set the scaling factor ratio = 0.7, which effectively creates a stricter constraint on the central alignment of bounding boxes.

Where

denotes the Intersection over Union of the internal regions between the predicted box and the ground truth box. Since Inner-IoU primarily emphasizes the matching of local regions, it demonstrates superior effectiveness in aerial small object detection and the weighting of target boundary details. However, the standalone Inner-IoU suffers from inadequate weight allocation, lacking the ability to dynamically adjust based on sample quality. Therefore, to combine the advantages of both, we formulate the Inner-WIoU loss. Mathematically, this is achieved by substituting the standard IoU term in the original WIoU-v3 loss with the Inner-IoU metric. Specifically, we subtract the standard IoU loss component

and add the Inner-IoU loss component

. The final derived formulation is expressed as follows:

Inner-WIoU not only retains the adaptive dynamic weighting capability of WIoU-v3 for high- and low-quality samples in complex scenes, but also integrates the constraint effects of Inner-IoU regarding small objects and precise boundary alignment. As a result, this strategy significantly boosts the recognition precision for minute aerial targets, all while preserving superior model stability. The efficacy of Inner-WIoU on tiny objects can be attributed to the gradient amplification effect. For small targets in aerial imagery, standard IoU loss often exhibits weak gradients when the overlap is high, limiting further localization refinement. By utilizing a smaller auxiliary box (), the effective IoU decreases compared to the original scale for the same deviation, thereby generating a larger gradient signal that forces the model to focus on finer alignment of the centroids. Coupled with the dynamic focusing mechanism of WIoU, this ensures that high-quality samples receive sufficient attention during the late stages of training.