1. Introduction

Binary programs are a key component of the software supply chain. The proliferation of their vulnerabilities—including known cloned vulnerabilities and unknown vulnerability variants (logically similar to known vulnerabilities but in different scenarios)—within the supply chain has become a core security challenge. The spread of such vulnerabilities propagates along the supply chain hierarchy, triggering chain reactions that threaten the stability of the digital ecosystem and cause severe security losses and risks.

Current binary vulnerability detection technologies fall into three categories: dynamic analysis, static analysis, and decompilation-assisted analysis. However, each approach faces significant bottlenecks. Dynamic analysis techniques—such as fuzz testing [

1,

2] and symbolic execution [

3,

4,

5]—are often limited by insufficient test coverage and path explosion. Moreover, taint analysis [

6,

7] suffers from accuracy issues, which further reduces its practical efficiency. As the mainstream approach [

8], static analysis has inherent limitations in its sub-methods: its similarity matching [

9,

10,

11] can only identify known vulnerabilities, suffering from high false-positive rates and reliance on manual verification; its pattern detection [

12] produces high false-positive and false-negative rates due to overly broad features or the need for manual feature extraction by experts. Although recent deep learning-based schemes [

13,

14] can automatically extract instruction semantics, modeling based on assembly or intermediate representation (IR) is prone to interference from compilation diversity (e.g., register reassignment or instruction reordering). Coarse-grained function-level feature modeling amplifies this interference, further undermining matching accuracy. Decompilation-assisted methods have not yet formed a mature system and fail to fully exploit the core value of decompilation technology.

Decompilation technology has been widely applied in binary analysis [

15]. Compared with assembly or IR, the pseudocode it generates offers significant advantages: it can fully reconstruct high-level semantic structures such as loops and branches, greatly reducing analysis complexity; meanwhile, with grammatical logic, control flow, and data structure characteristics highly consistent with source code, it fills the compatibility gap between low-level binary representations and mature source-code vulnerability detection tools. Source-code vulnerability detection tools already possess the ability to efficiently identify vulnerability patterns (e.g., buffer overflow and null pointer dereference) and properly handle complex code-logic associations. Decompiled pseudocode precisely serves as a key bridge between the two, providing a new path to address the challenges of binary vulnerability detection.

Despite their great potential, existing decompilation-related schemes still face two core issues restricting their application, the first of which is insufficient semantic restoration quality. The outputs of traditional decompilation tools such as IDA Pro [

16] and Ghidra [

17] suffer from problems including incomplete semantics, incorrect variable-type inference, and deviations in complex control-flow reconstruction [

18], failing to meet the stringent requirements of vulnerability detection for “high-precision decompiled source code”. The second issue affecting their application is inadequate tool compatibility. Most existing studies only utilize decompiled intermediate representations [

19,

20] or merely use pseudocode for auxiliary feature extraction [

21,

22], failing to achieve in-depth integration with mature source-code vulnerability detection tools and underutilizing their mature analytical capabilities.

To address the aforementioned issues, this paper proposes LLMVulDecompiler, a binary-code decompilation model based on large-model fine tuning. Its core goal is to generate high-precision decompilation results that can be directly integrated with source-code static analysis tools. The specific contributions are outlined as follows:

We propose the LLMVulDecompiler decompilation large language model for binary vulnerability detection, explore the feasibility of applying large models in this field, and design a low-cost inference path to achieve low-consumption and high-efficiency inference.

We construct a decompilation-specific training and evaluation dataset, covering multiple optimization levels and diverse functionalities to support the comprehensiveness of model training and the objectivity of evaluation.

We establish a multi-dimensional evaluation system, conduct quantitative decompilation analysis based on average edit distance, design targeted special test code for functionalities, and realize in-depth verification of the model’s decompilation performance.

We integrate source-code vulnerability analysis tools to detect real vulnerability instances, verifying the practicality and effectiveness of the proposed method in binary vulnerability detection scenarios.

2. Related Work

2.1. Research Status of Binary Decompilation Technology

Binary decompilation is a key enabler of security analysis when source code is unavailable. Following decades of development [

23,

24], binary decompilation has evolved through three phases: (1) traditional static analysis-driven methods, (2) neural machine translation-based approaches, and (3) LLM-powered techniques. Current research focuses on improving output readability, semantic consistency, and practical deployability. The traditional phase was centered on static analysis and pattern matching [

25], witnessing the emergence of industrial tools such as IDA Pro [

16] and Ghidra [

17]. However, their outputs suffer from limitations including confused variable mapping and redundant goto statements [

26]. After 2018, it entered the neural translation paradigm [

24], relying on RNN encoder–decoder architectures to learn semantic mapping [

27]. While this improved the degree of structuring, it was constrained by shortcomings in modeling long-sequence dependencies. With the application of LLMs in code understanding [

28,

29,

30], decompilation has stepped into the dedicated large model phase. BTC [

31] and Slade [

32], fine-tuned based on a 200-million-parameter foundation language model, achieved breakthroughs in structured output for simple binaries. Nova [

33] enhances the understanding of complex instruction sets. In 2024, the open-source LLM4Decompile [

34], leveraging large-scale pre-training, performed excellently in semantic restoration and recompilability. ReF-Decompile [

35] enhances the semantic consistency of decompilation through relabeling and function call inference. WaDec [

36] expands to the processing of the WebAssembly format. Current technologies are evolving from “syntactic restoration” to “semantically equivalent restoration”, exhibiting three key trends: model specialization and scaling, practicalization of evaluation systems, and technology integration.

2.2. Application of Decompilation in Vulnerability Detection

Binary decompilation serves as the key bridge connecting “source code-free binaries” and “source code-level detection”, but the effectiveness of its application is constrained by decompilation quality and scenario adaptability. LLM technology provides new possibilities for the optimization of hybrid approaches—for instance, WPeChatGPT [

37] leverages GPT-4 to process decompiled pseudocode and improve detection accuracy. However, limited by network stability and invocation costs, it is difficult for such approaches to achieve large-scale deployment.

Synthesizing the aforementioned research status, there are two core research gaps in this hybrid field: On the decompilation front, existing large models (e.g., Slade [

32] and LLM4Decompile [

34]) are mostly general-purpose designs, lacking customized optimization objectives for vulnerability detection scenarios (such as prioritizing the restoration of semantic structures related to high-risk vulnerabilities). Their output suffers from insufficient semantic completeness and compatibility with detection tools. On the technology chain front, there is a lack of a complete technical chain integrating “LLM-optimized decompilation-connection to source code detection tools”. Moreover, most existing studies focus on individual links, only evaluating the syntactic correctness or executability of decompilation, without verifying the end-to-end implementation value of the “decompilation-detection” process in real vulnerability scenarios.

3. Decompilation Large Language Model: LLMVulDecompiler

To address the aforementioned gaps in decompilation-based vulnerability detection, we focus on two objectives: (1) customizing a dedicated decompilation large language model and (2) verifying its practical effectiveness in real-world vulnerability detection. First, we fine tune a large decompilation model specialized in binary vulnerability detection based on foundation language models to improve the quality of semantic restoration and compatibility with detection tools. Second, we select real vulnerability instances to verify the end-to-end effectiveness along two dimensions: “adaptability of decompilation results” and “detection accuracy”.

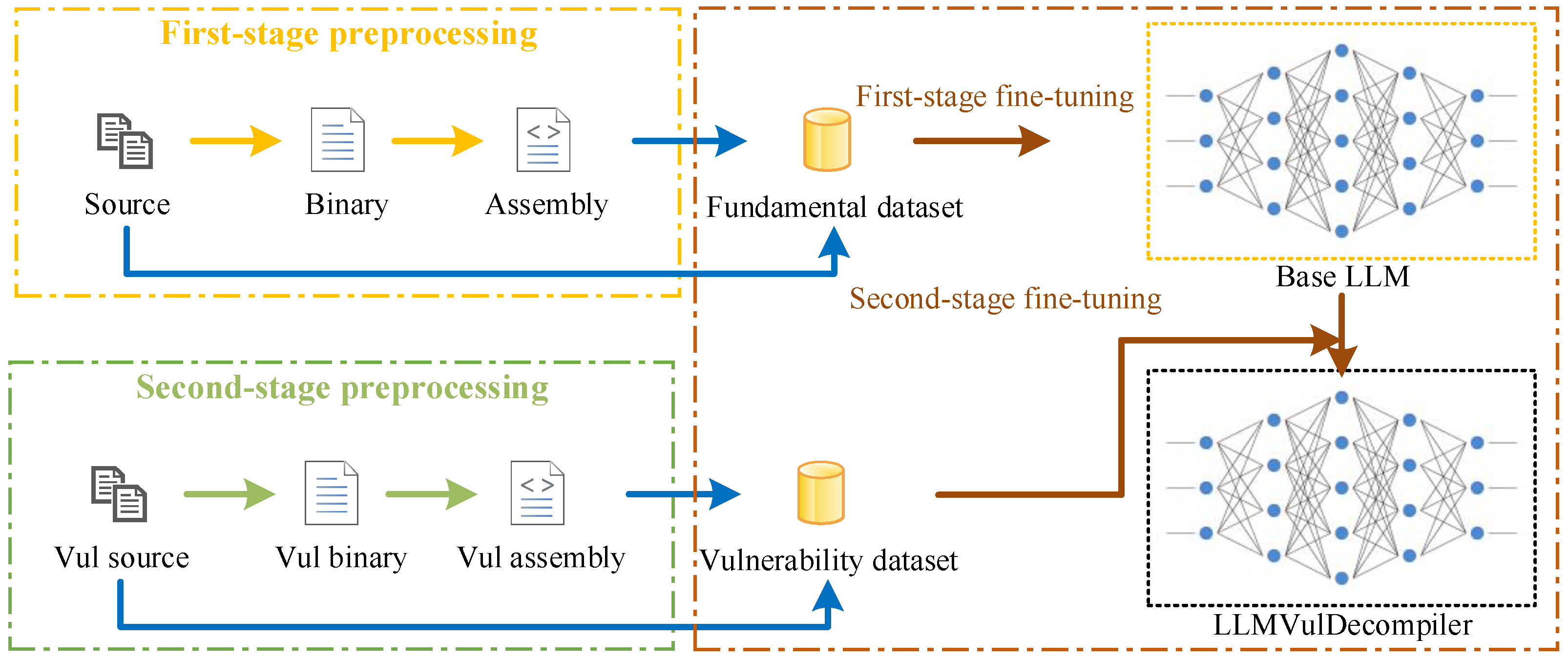

To intuitively illustrate the differences between existing vulnerability detection schemes and the proposed scheme in the technical chain, we attach the following flow chart (as shown in

Figure 1).

This chapter elaborates on the core implementation scheme of the LLMVulDecompiler model, following the logical thread of “data support–model training–capability implementation”. It sequentially introduces the design of data collection and preprocessing, large model fine tuning, and vulnerability detection modules. These modules form an iterative pipeline: the data module supplies training pairs, the fine-tuning module learns decompilation mappings, and the detection module applies the output to vulnerability identification.

3.1. Data Collection

High-quality training data is a core prerequisite for models to learn decompilation mapping relationships. This section focuses on two key dimensions: dataset construction and quality control. Function-level data is selected from ExeBench [

38], compilation optimization strategies are integrated to enhance data diversity, and duplicate samples are removed through preprocessing to provide reliable data support for subsequent model fine tuning. This paper focuses on the x86-64 assembly functions of C programs, and the proposed method can be extended to other assembly languages such as ARM.

Numerous studies have confirmed that the performance of large language models is closely related to the scale, quality, and diversity of training datasets. Therefore, constructing a large-scale training dataset based on ExeBench is identified as the primary step of training optimization. We construct assembly–source code pairs using ExeBench, the first public dataset of executable C code. It contains 4.5 million compilable C functions and 700,000 executable functions, spanning scenarios from simple algorithms to complex engineering projects. For regular C functions, we adopt a deduplication-then-sampling strategy: we first apply SHA-256 hashing to remove duplicates from the 4.5 million functions in ExeBench, then randomly select 12,000 samples from the deduplicated set. Since ExeBench inherently covers diverse functional scenarios (e.g., algorithm implementations and engineering development) and code structures, random sampling preserves the original diversity of the dataset; therefore, we do not apply further augmentation or pruning. To further expand the scale of training data, we leverage compilation optimization states common in daily development, such as redundant instruction elimination, register allocation optimization, and loop transformation, which effective for data augmentation in decompilation tasks. We incorporate four core optimization levels, ranging from the basic O0 (no optimization) to the aggressive O3. The specific implementation process is described as follows: First, clarify the compilation environment and parameter configuration; build a standardized compilation pipeline based on a GCC compiler with a unified x86-64 target architecture; and use static linking to embed all dependencies, ensuring complete disassembly without missing external symbols. Second, for each extracted C-function source-code sample, execute compilation commands for each of the following four levels: generate binary files corresponding to the optimization levels by adding parameters or -O0 (no optimization), -O1 (basic optimization), -O2 (advanced optimization), and -O3 (aggressive optimization), among which the O0 level preserves the original execution logic and instruction structure of the source code, while levels O1–O3 sequentially enable progressive optimization technologies such as redundant instruction elimination, register allocation optimization, loop unrolling/transformation, and function inlining, resulting in differentiated assembly instruction sequences for binary files of different levels. Finally, establish pairing rules for “source code-multi-optimization-level assembly” and bind each original C-function source code one-to-one with the x86-64 assembly code generated by disassembling the four optimization-level binary files via Objdump, forming multi-dimensional paired data of “single source code-four assemblies”. This not only achieves a fourfold expansion of the scale of the training data but also enables the model to fully learn the mapping variation rules between the source code and assembly under different optimization strategies.

Data quality is critical for the training of efficient models, making training-set cleaning the second core task. To remove exact duplicate data in the training set, we first preprocess the code: unify all code into UTF-8 encoding to eliminate misjudgments caused by encoding differences and remove irrelevant format information such as redundant white space and comments while retaining core code logic. Subsequently, we compute the SHA-256 hash value for each preprocessed sample, identify duplicate samples through global hash-value matching, and ultimately retain only the first occurrence of each duplicated group, completely eliminating redundant data and reducing the effect of interference from redundant information on model training.

The final step of dataset construction focuses on enabling the model to solidify binary-related knowledge and specifically enhance the restoration capability of vulnerable code. The first phase is the basic capability foundation stage: we use a large-scale compilable C-language dataset and compile the code into x86-64 architecture binary files via GCC. By learning such “source code-binary” paired data, the model gradually establishes the correspondence between C-language logic and x86-64 binary instructions, thereby mastering the underlying transformation rules and features of binary code. The second phase is the vulnerability scenario enhancement stage. Focusing on representative vulnerability types—such as buffer overflow, null pointer dereference, integer overflow/underflow, and format string vulnerabilities—we construct a dataset of 500 vulnerable code samples using a hybrid approach that combines curated public vulnerability data with synthetically generated examples. Specifically, 20 samples are extracted from real-world, reproducible vulnerability fragments sourced from CVE entries and GitHub Security Advisories, while the remaining 480 are synthetic. These synthetic samples strictly replicate the core triggering mechanisms of actual CVEs, preserving key semantic features—such as stack-based out-of-bounds accesses (in buffer overflows) and arithmetic wraparound (in integer overflows)—to ensure fidelity to real-world vulnerability semantics. To enrich sample diversity and improve model generalization in complex scenarios, we vary contextual elements, including the loop-nesting depth, function call-chain length, input sources, and compiler optimization levels (O0–O3). This design ensures that all synthetic cases reflect diverse code structures, input origins, and triggering conditions while remaining grounded in the fundamental principles and contextual characteristics of each vulnerability type. All code is written in C, encapsulated into independent functions, supplemented with necessary dependencies, and standardized in terms of format to ensure compilability, consistent with the format of the first-phase dataset. Subsequently, the samples are compiled into x86-64 binaries of all optimization levels (O0–O3) via GCC, forming “vulnerable code-corresponding binary” paired data for model training. This enables the model to better capture the distinctive patterns of compiled vulnerable code, building on its general binary understanding, thereby enhancing its ability to restore vulnerability scenarios.

3.2. Large-Model Fine Tuning

Fine tuning is the core step for the model to acquire the capability of decompiling from assembly to source code-like output. First, this section introduces the fine-tuning workflow—from source code to binary, then to assembly and, finally, to source code-like outputs. It then elaborates on the two-stage training strategy of “basic capability learning–vulnerability feature enhancement” and, finally, explains the design of the loss function, fine-tuning framework, and key parameter configurations.

Figure 2 illustrates the binary source-code decompilation fine-tuning framework and its correspondence with the compilation process: during compilation, the preprocessor first cleans the source code (removing comments, expanding macros, and including files); the compiler converts it into assembly code; the assembler generates binary code; and, finally, the linker integrates function calls to produce an executable file. Decompilation, by contrast, is the reverse process of restoring binary code to source code. Since large language models are trained on text and cannot directly process binary data, Objdump is used to disassemble binary files into equivalent assembly code first; then, the difference between the decompiled code and the original source code is used as the loss to guide training.

The core of large-model fine tuning is to enable the model to master the ability to generate source code-like outputs through decompilation. It generally follows the workflow of source code → binary → assembly → source code-like output, with the goal of “minimizing differences”. The specific data conversion process is described as follows: The source code of the basic function dataset is taken as input and compiled into x86-64 binary files via GCC (adopting static linking to integrate all dependent libraries to avoid incomplete decompilation caused by missing dynamic link libraries). Then the binary files are disassembled into the x86-64 assembly code. Finally, the assembly code is input into the model, which generates a “decompiled source code” with structure and logic close to those of the original source code.

A two-stage progressive strategy of “foundation capability building–vulnerability feature enhancement” is adopted for fine tuning, forming a closed loop with the dataset construction logic to ensure training effectiveness. The first stage focuses on cultivating assembly source-code restoration capability in general scenarios. It utilizes the “x86-64 assembly source code” paired data generated by compiling the large-scale compilable C-language dataset (from the first phase) via GCC and disassembling via Objdump. The core goal is to learn the mapping rules between general C-language syntax, code structures, and x86-64 assembly instructions; optimize the restoration accuracy of basic elements, such as variable definitions, loop/branch logic, and function calls; and help the model establish a stable cognitive mapping between “assembly instruction sequences and source-code logic”. On the basis of meeting the basic capability requirements, the second stage targets key vulnerability types (e.g., buffer overflow and null pointer dereference) and adopts vulnerability-specific “x86-64 assembly source code” paired data covering all optimization levels (O0–O3). It focuses on the unique assembly characteristics of compiled vulnerable code (such as stack operation instruction sequences corresponding to buffer overflow and memory access instruction patterns corresponding to null pointer dereference), enhancing the model’s sensitivity to vulnerability-related assembly features. Ultimately, it achieves the goal of accurately restoring the vulnerable source-code structure, triggering logic and key details from the assembly code in vulnerability scenarios.

During fine tuning, we minimize the difference between the original source code and the model-generated decompiled code as the training objective. We fine tune the DeepSeek-Coder-1.3B model on a single NVIDIA RTX A6000 GPU (CUDA 12.6, 48 GB GDDR6 memory) for approximately 10 days. Specifically, we use the publicly available DeepSeek-Coder-1.3B-Base model from Hugging Face as our base, leaving its architecture unchanged. We conduct training using the LLaMAFactory [

39] framework and adopt refined hyperparameters to ensure effectiveness. We set the number of training epochs to two to balance learning and overfitting. This choice is driven by hardware constraints: training for two epochs on a single GPU already requires about 10 days. Moreover, the loss stabilizes after the second epoch, with no significant further reduction with additional epochs. We limit the combined input and output length to 1024 tokens to fit the typical scale and structure of our data. For batching, we use a per device batch size of 16 with 16-step gradient accumulation, yielding an effective batch size of 256 to balance GPU memory usage and training stability. We set the initial learning rate to 2 × 10

−5, apply gradient clipping at 1.0 to prevent explosion, and use a weight decay of 0.1—a value commonly adopted in similar LLM fine-tuning studies [

34]. Computational constraints prevent us from testing alternatives. Additionally, we apply a learning-rate warmup over the first 2.5% of training steps to stabilize early optimization. With these settings, the model progressively improves as it minimizes loss, producing decompiled code that more closely matches the structure and logic of the original source.

In model fine-tuning, negative log-likelihood Loss is adopted to optimize the generation accuracy from assembly code to source code-like outputs. Let the tokenized input assembly sequence be

and the target original source-code sequence be

. The conditional probability of the model predicting the next token based on prefix

A and the generated partial source-code sequence is

(where

denotes model parameters). The loss function is defined as follows:

This loss supervises the autoregressive prediction process of the target sequence (

S), minimizing the difference between the generated sequence and the true sequence. The term

is used to balance the weights of sequences with different lengths. This study employs a lightweight fine-tuning strategy, completing all training on a single NVIDIA RTX A6000 GPU in approximately 10 days. The training data consists of 12,000 standard C-function samples and 500 vulnerability samples, totaling about 1.88 million tokens—achieving effective vulnerability detection while significantly constraining computational overhead. In contrast, LLM4Decompile [

34]—even its 1.3B-parameter variant—requires a cluster of eight A100 GPUs for training, takes around 12 days to converge, and performs full fine tuning on a large-scale corpus comprising approximately 7.6 billion tokens. The substantial differences in computational resources, training duration, and data volume highlight the advantages of our approach in terms of data efficiency, hardware accessibility, and deployment practicality, making it particularly suitable for academic research or resource-constrained security teams seeking rapid reproducibility and real-world applicability.

3.3. Vulnerability Detection

Figure 3 illustrates the overall workflow of binary vulnerability detection based on the decompilation results of the LLMVulDecompiler model. This section designs a detection scheme around this workflow, with the core goal of realizing vulnerability identification through static analysis tools. Meanwhile, it enhances the model’s accuracy in restoring vulnerable code by leveraging vulnerability data augmentation during the fine-tuning phase, ultimately optimizing the overall vulnerability detection accuracy.

We use mature static analysis tools to scan the decompiled source code for vulnerabilities. The specific workflow is described as follows: Taking the high-precision decompiled source code generated by the model as input, the tool performs automated scanning and in-depth analysis. Then, combined with the tool’s output results (e.g., vulnerability alert information and vulnerability type identifiers), it determines whether the target vulnerability exists in the source code, ultimately completing the full process of binary-code vulnerability identification.

The key to improving the accuracy of the aforementioned detection workflow lies in enhancing the model’s precision in restoring vulnerable code. We achieve this goal by introducing a “vulnerable instance dataset” during the fine-tuning phase. This dataset covers multiple vulnerability scenarios focused on in the research, including corresponding C-language source code and its compiled the x86-64 assembly code. After integrating such “vulnerable source code–vulnerable assembly” paired data into training, the model can specifically learn the assembly and source-code features in vulnerability scenarios, thereby accurately capturing the manifestation rules of vulnerabilities at the binary level. Thus, the model produces decompiled code that better reflects real vulnerability patterns, giving static analyzers more reliable input and improving detection accuracy.

4. Experiments

4.1. Experimental Setup

4.1.1. Training Data

As described in

Section 3.1, we constructed paired assembly–source code training data from the ExeBench dataset and collected or generated vulnerable code, focusing on the decompilation task of C functions compiled by GCC on the x86-64 Linux platform. After data cleaning (removing duplicate and non-compilable samples), the final scale of the training set was determined as follows: the general C-code training set contains 12,000 samples (covering scenarios such as basic algorithms and engineering modules), corresponding to approximately 1.8 million tokens; the vulnerable-code training set includes 500 samples (covering target vulnerability types such as buffer overflow and use-after-free), corresponding to approximately 75,000 tokens.

We used a unified input–output template during training: # Assembly code: [assembly code] # Provide source code: [source code]. Here, [assembly code] refers to the x86-64 assembly code obtained by disassembling binary files via Objdump, and [source code] denotes the original C function. This template merely unifies the data format, helping the model learn the assembly-to-source mapping without degrading performance. No fixed initialization seed was set during the training process; instead, random number generation relied on the system’s default values, with no relevant initialization logic implemented at the code level.

4.1.2. Evaluation Benchmarks and Metrics

Evaluation Benchmark

The core evaluation benchmark was built based on the authoritative HumanEval programming benchmark [

40]: the original benchmark contains 164 handwritten Python programming problems, covering core scenarios such as data structures, algorithm implementation, and string processing. To meet the requirements of C-language decompilation evaluation, we followed the Decompile-Eval benchmark methodology proposed in [

34] for benchmark construction: on the one hand, we equivalently converted the 164 Python solutions corresponding to the original problems into C-language implementations, only adjusting the formatting to comply with C-language syntax rules, without altering the original functional logic or algorithmic complexity; on the other hand, we followed the test-case conversion approach of this methodology to extend and convert the Python black-box test cases—matching one test case for each target C function at each of the four GCC compiler optimization levels, i.e., O0 (no optimization), O1 (mild optimization), O2 (moderate optimization), and O3 (high optimization). This resulted in a total of over 600 directly compilable and executable C-language test cases, which fully cover the functional verification needs under different compilation optimization scenarios. Accordingly, this evaluation benchmark was named HumanEval-C.

Evaluation Metrics

Three core metrics were designed to evaluate the model’s decompilation performance with respect to dimensions: restoration similarity, executability, and functional correctness.

Average Edit Distance: This metric quantifies the textual similarity between decompiled code and original code. The workflow is described as follows: compile the original C code in HumanEval-C into binary files via GCC, disassemble the binaries and input the assembly code into the model to generate decompiled source code, calculate the edit distance between the generated code and the original code for each sample, and take the average of all samples. A smaller value indicates higher restoration accuracy. The unified calculation formula is exoressed as follows:

where

denotes the average edit distance across all experimental samples;

k is the total number of “original C code–decompiled code” pairs included in the calculation;

i is the sample index (within the range of

);

is the total length of normalized matching blocks for the

i-th sample; and

and

are the total normalized character lengths of the original C code and decompiled code for the

i-th sample, respectively. The average edit distance falls within the range of [0, 1]. Values closer to 0 indicate higher structural similarity between the decompiled code and original code, reflecting better code restoration accuracy of the model.

Compilation Success Rate: This metric evaluates the syntactic validity of decompiled code. It is defined as the proportion of decompiled source-code samples generated by the model that can be successfully compiled by GCC (x86-64 architecture) without syntax errors.

Black-box Test Pass Rate: This metric verifies the functional consistency of decompiled code. It calculates the proportion of successfully compiled decompiled source-code samples that pass all black-box test cases in HumanEval-C after linking with the test code. A higher proportion indicates more accurate functional restoration.

4.1.3. Baseline Models

We compare against three baselines. First, we include Doubao [

41], a widely used commercial large language model that possesses mature general text understanding and code generation capabilities, representing the performance ceiling of current industrial-grade commercial LLMs in related tasks. Second, DeepSeekCoder [

30], a representative model in the open-source code field, has undergone specialized optimization for tasks such as code generation and understanding and maintains leading performance on authoritative code benchmarks, representing the highest level of publicly accessible models. Third, the recently proposed LLM4Decompile [

34], a dedicated decompilation model, adopts an “assembly → source code” generation framework similar to that proposed in this study and is optimized for binary decompilation scenarios. It represents the latest technical progress in this direction, enabling direct comparison of performance differences on specialized tasks.

The specific configurations of the aforementioned baseline models are outlined as follows: Doubao uses the public version (1.82.5), without fixed decoding parameters, interacting through multiple manual conversations. It incurs no additional invocation cost but is time-consuming. For DeepSeek-Coder-1.3B, we use the public base version from Hugging Face, with both temperature and decoding parameters set to official defaults and the maximum number of generated tokens limited to 1024. LLM4Decompile-1.3b-v1.5 is the official open-source v1.5 version, using default settings for all parameters. To control for input length, we truncated all inputs to a maximum of 1024 tokens.

We additionally tested Qwen2.5-Coder-1.5B-Instruct [

42], a model with a similar parameter scale. Its output was largely garbled, and its decompilation performance was inferior to that of DeepSeekCoder-1.3B, lacking comparative value. For large-parameter models such as DeepSeekCoder-33B, limited by a single NVIDIA RTX A6000 hardware configuration, only a small number of sample tests could be completed. These models exhibited extremely slow inference speed, without significant improvement in readability, failing to demonstrate the advantage of parameter scale. Furthermore, based on prior testing experience, models including StarCoder2 [

43], Code Llama [

44], and WizardCoder [

45] were predicted to be unable to match the specialized optimization objectives of this study for vulnerability detection scenarios and, therefore, were not included in the full comparison.

4.2. Experimental Results

Based on the HumanEval-C evaluation benchmark, this section systematically compares the decompilation performance of the proposed LLMVulDecompiler (1.3B) model with that of three types of baseline model (DeepSeekCoder-1.3B, Doubao, and LLM4Decompile-1.3b-v1.5) under different compilation optimization levels (O0–O3) of the x86-64 architecture. The comparison covers three core metrics: average edit distance (restoration similarity), compilation success rate (syntactic validity), and black-box test pass rate (functional correctness). All experiments used the settings reported in

Section 4.1 to ensure a fair comparison.

4.2.1. Results and Analysis of Average Edit Distance

The average edit distance quantifies the textual similarity between the “decompiled source code” generated by the model and the original C code. A smaller value indicates smaller differences between the two and higher restoration accuracy. Test results of each model under different compilation optimization levels are shown in

Table 1.

To more intuitively show the changes in restoration accuracy of various models under different compilation optimization levels,

Figure 4 plots the trend chart of the average edit distance. Across all compilation optimization levels, the average edit distance of LLMVulDecompiler (1.3B) is lower than that of DeepSeek-Coder-1.3B, Doubao, and LLM4Decompile-1.3b-v1.5. Among them, it achieves the best performance at the O0 level, with a significant advantage in restoration accuracy.

This improvement stems from our compilation optimization data augmentation strategy. Trained on four levels (O0–O3) of “source code–assembly” paired data, the model accurately captures the instruction–source code mapping rules under different optimization scenarios, demonstrating stronger adaptability to features such as instruction rearrangement and redundancy elimination at high optimization levels (O1–O3). In contrast, DeepSeek-Coder-1.3B performs poorly because it has not learned to map assembly back to C. Doubao’s accuracy is limited due to the lack of specialized decompilation training.

In addition, all models exhibit a pattern according to which “the accuracy is optimal at the O0 level and slightly decreases as the optimization level increases”. However, LLMVulDecompiler (1.3B) exhibits the smallest decline, further verifying its adaptability advantage over high-optimization-level binaries.

4.2.2. Results and Analysis of Compilation Success Rate and Black-Box Test Pass Rate

The compilation success rate reflects the syntactic validity of decompiled code (whether it can be compiled by GCC), while the black-box test pass rate verifies the functional consistency between the decompiled code and the original code (whether it can pass the functional test cases of HumanEval-C). Together, they measure the “usability” of the model’s decompilation results. The test results of each model are shown in

Table 2.

As shown in

Table 2, LLMVulDecompiler (1.3B) achieves the best performance in terms of practicality metrics. Its compilation success rate and black-box test pass rate are significantly higher than those of baseline models across all optimization levels, with the optimal performance at the O0 level. This benefit stems from the “two-stage fine-tuning” and “vulnerability feature enhancement” strategies, enabling the generated code to possess both syntactic validity and functional consistency.

Compared with baseline models, the same-domain LLM4Decompile-1.3b-v1.5 lags behind LLMVulDecompiler (1.3B) in both metrics. DeepSeek-Coder-1.3B achieved 0% on both metrics, rendering it impractical for real-world use. The commercial Doubao model delivers moderate performance, only approaching LLMVulDecompiler (1.3B) in functional restoration at the O0 level, but its performance degrades significantly as the optimization level increases. All models exhibit the pattern of “performance degradation from O0 to O3”, with the most notable drop in the black-box test pass rate. This is primarily because instruction reordering in highly optimized binaries obscures the original source structure. Even after the decline, LLMVulDecompiler (1.3B) remains leading, further verifying its specialized adaptation advantage.

4.2.3. Result Stability and Statistical Significance Testing

To ensure the reliability and statistical significance of the experimental results, we conducted three confirmatory replicate experiments on LLMVulDecompiler, covering all the aforementioned core metrics: average edit distance, compilation success rate, and black-box test pass rate. Across three runs, each metric varied by less than 0.001, demonstrating excellent stability. Based on these stable results, we performed independent-samples t-tests to compare performance differences between our model and each baseline. The p-values in all comparison scenarios were less than 0.05, confirming that the observed performance advantages are statistically significant (i.e., not attributable to random chance). Given the minimal standard deviations of the metrics across the three experiments, they are not separately tabulated above.

4.3. Vulnerability Case Testing

To verify the assembly-to-source code-like decompilation accuracy and vulnerability detection adaptability of the LLMVulDecompiler model in real vulnerability scenarios, we selected 12 real vulnerability instances (with public CVE IDs) covering 5 types of typical high-risk vulnerabilities (buffer overflow, null pointer dereference, use-after-free, etc.) as benchmark test samples while supplementing auxiliary samples to enhance the comprehensiveness and objectivity of the test system. Through the core workflow of “disassembly → model-generated source code-like output → static source code analysis tool detection”, it compares and analyzes the vulnerability detection accuracy of LLMVulDecompiler and the commercial Doubao model [

41]. The core evaluation metrics are the detection accuracy (number of accurately identified vulnerabilities/total number of vulnerabilities) and False-Positive Rate (FPR).

4.3.1. Test Setup

The multi-dimensional test suite constructed for this test consists of three types of samples to ensure the representativeness and objectivity of the test results: (1) Core benchmark samples include 12 C-language vulnerability instances across 5 high-risk categories, covering buffer overflow (CWE-119, CWE-121, and CWE-122), integer overflow (CWE-190), null pointer dereference (CWE-476), use after free (CWE-416), and format string vulnerability (CWE-134). All instances were sourced from real-world software such as OpenSSL, the Linux Kernel, and router firmware, with explicit CVE IDs ensuring the engineering practicality and representativeness of the test scenarios. (2) Auxiliary validation samples supplement eight non-CVE vulnerability instances (not included in accuracy calculation) to further improve the coverage of test scenarios. (3) False positive-rate calibration samples incorporate 30 vulnerability-free C-language function samples (derived from the HumanEval-C dataset presented in

Section 4.1) to accurately measure the model’s false-positive risk in vulnerability-free scenarios.

The test tool chain includes the Objdump disassembly tool (based on the x86-64 architecture, consistent with the experimental tools proposed in

Section 4.1) and the Tencent Cloud Code Analysis (TCA) static detection tool [

46]. TCA was chosen for its out-of-the-box coverage of the five target vulnerability types and its support for automated source-code scanning. The integrated Web-based tool of TCA was adopted, eliminating the need for manual configuration of activation rules and detection thresholds, inherently covering the target vulnerability types, and automatically generating detection results upon code input. Prior to scanning, only the standardization of the typesetting format (unified indentation and standardized bracket positions) was performed on the decompiled outputs, without modifying the code logic or syntax structure in order to ensure detection compatibility the objectivity of the results.

The test workflow was executed in the following steps: First, Objdump was used to disassemble the original binary file of each vulnerability instance into the x86-64 assembly code. Then, the assembly code was input into the LLMVulDecompiler and Doubao models to generate structurally complete “decompiled source code”. Subsequently, TCA was used to scan the decompiled source code output by the two models and generate vulnerability detection reports. Finally, the results were judged based on authoritative vulnerability features from the official CVE database, software vendor vulnerability announcements, and third-party security audit reports. “Accurate (✓)” means the detected vulnerability type and cause completely match the real labels, without redundant alerts, while “Error (×)” includes two cases: false negative (FN) for real vulnerabilities and false positive (FP) for irrelevant vulnerabilities.

4.3.2. Statistics of Detection Results

The vulnerability detection results and core metrics of the two types of models are summarized in

Table 3 and

Table 4. All results were based on the same assembly code input and detection rules to ensure the fairness of comparison.

The detection results for the auxiliary validation samples and false-positive rate calibration samples indicate that all eight non-CVE vulnerability instances were accurately detected after decompilation by LLMVulDecompiler and no vulnerabilities were detected by TCA scanning of the decompiled outputs from the 30 vulnerability-free C-language function samples. This further verifies the effectiveness of LLMVulDecompiler in extended vulnerability scenarios and its low false-positive characteristic in vulnerability-free scenarios.

4.3.3. Analysis of Results

Experimental data shows that LLMVulDecompiler outperforms Doubao significantly in detection accuracy and false-positive rate (FPR) across 12 real CVE vulnerability instances. Doubao’s false positives are concentrated in vulnerability scenarios with concealed features, such as null pointer dereferences involving indirect pointer offsets. The results of the auxiliary validation samples and false-positive rate calibration samples further reinforce this conclusion: the accurate detection of eight non-CVE vulnerability instances by LLMVulDecompiler demonstrates that its vulnerability detection capability can cover non-standardized public vulnerability scenarios; the zero-false-positive result of the 30 vulnerability-free samples confirms the objectivity of its false-positive rate metric, indicating that the model will not generate false positives for normal code in practical applications.

The core of the performance difference lies in the distinct learning paradigms for the “assembly–vulnerable source code mapping relationship”: LLMVulDecompiler constructs a dedicated “instruction pattern–logical structure” mapping space for high-risk vulnerabilities through two-stage fine tuning on “vulnerable source code–assembly” paired data. It can mine deep semantic associations triggering vulnerabilities, providing precise semantic input for static detection tools. In contrast, Doubao is trained on general text understanding, without optimizing the underlying assembly semantics or special vulnerability representations. It can only capture superficial instruction sequences, struggling to parse core semantics behind concealed features, leading to semantic distortion, false negatives, and false positives.

Furthermore, vulnerability feature attributes amplify this difference: assembly features of vulnerabilities such as use after free and buffer overflow are prominent, enabling both models to partially capture them. However, null pointer dereferences—especially instances involving indirect pointer passing—have concealed features. Their logical restoration relies on deep semantic reasoning, which is exactly the advantage of LLMVulDecompiler’s specialized mapping mechanism and the bottleneck of general-purpose models. The successful case of func0 (normal code) in

Appendix A verifies the model’s ability to accurately restore conventional syntax and logic, while the decompilation failure case of CVE-2018-5333 reveals its shortcomings in semantic restoration for scenarios involving complex data structures and concealed pointer offsets.

5. Conclusions

The proposed LLMVulDecompiler model improves the restoration accuracy and functional consistency of C-function decompilation by constructing an assembly–source code paired dataset for GCC-compiled programs on the x86-64 Linux platform and integrating compilation optimization data augmentation and a two-stage fine-tuning strategy. Validation of experimental results shows that the model outperforms commercial models (Doubao), open-source-code SOTA models (DeepSeekCoder), and domain-specific decompilation models (LLM4Decompile-1.3B-v1.5) in average edit distance, compilation success rate, and black-box test pass rate on the HumanEval-C benchmark. In the verification of 12 real vulnerability instances, except for a false positive in the extremely complex null pointer dereference vulnerability (CVE-2018-5333) due to concealed assembly features, the other 11 cases were accurately detected. With a detection accuracy of 91.7%, it outperforms Doubao’s 66.7% and significantly reduces the false-positive rate of general-purpose models in vulnerability scenarios. This study preliminarily verifies the effectiveness of specialized optimization for “assembly–source code mapping” in restoring code logic (especially vulnerability features), providing a practical reference for the design of domain-specific binary decompilation models and laying the foundation for subsequent verification and optimization in larger-scale and more complex scenarios.

6. Discussion

This study focuses on the x86-64 architecture and GCC compiler, a mainstream configuration in the industry that represents a dominant share of core scenarios such as servers and embedded systems, ensuring the experimental results cover key application contexts. The core methodologies—including the two-stage fine-tuning strategy, data construction logic, and tool integration framework—exhibit cross-architecture/compiler adaptability. Essentially, they learn the general mapping rules between “assembly instruction semantics and C-language logic”, enabling seamless migration to ARM/MIPS architectures and the Clang compiler by merely replacing the corresponding training dataset.

For the construction of the experimental validation system, tests were conducted based on the Decompile-Eval benchmark, which was optimized based on HumanEval for decompilation scenarios. The benchmark covers algorithmic scenarios highly consistent with practical industrial C functions, thereby guaranteeing the engineering applicability of the experimental results. Beyond the rationality of the experimental benchmark, the proposed LLMVulDecompiler demonstrates significant advantages over traditional decompilation tools in terms of vulnerability detection process compatibility. Compared with conventional tools like IDA Pro and Ghidra, LLMVulDecompiler offers distinct workflow integration benefits: traditional tools typically output assembly code or non-standardized pseudocode, which requires additional manual processing (e.g., syntax standardization and semantic supplementation) to interface with static analysis tools. In contrast, LLMVulDecompiler directly generates C language-compliant decompiled code that can seamlessly integrate with static detection tools without human intervention, substantially improving the efficiency of the engineering implementation of vulnerability detection. Currently, the academic community lacks a unified evaluation standard for the vulnerability detection capabilities of decompilation tools—a common limitation that precludes direct quantitative comparisons in terms of “detection accuracy”. However, LLM-based decompilation schemes inherently possess greater flexibility in semantic restoration accuracy and offer more technical expansion potential than traditional tools with mature core logic.

Further analysis of vulnerability detection performance reveals notable discrepancies in accuracy across different vulnerability types: Vulnerabilities such as buffer overflows and use after free exhibit strong assembly-level signature characteristics (e.g., characteristic stack operation instruction sequences and typical memory access patterns), allowing the model to accurately capture their mapping relationships with C-language logic. In contrast, null pointer dereferences—especially instances involving indirect pointer offsets—feature subtle assembly signatures that demand deep logical reasoning, such as structural semantic restoration and memory offset calculation. This remains not only a key challenge for the proposed model but also a universal bottleneck in the field of LLM-based decompilation.

The relatively low black-box test pass rate under high compiler optimization levels should be understood in context: this is a common challenge in decompilation, primarily due to two inherent constraints. First, aggressive optimizations—such as instruction reordering, loop unrolling, and function inlining—significantly alter or obscure the original program structure, making faithful reconstruction difficult; indeed, existing state-of-the-art models exhibit similarly limited pass rates under these conditions. Second, the evaluation benchmark imposes a strict functional equivalence requirement that exceeds the practical needs of real-world vulnerability detection. From an applied perspective, however, the current performance remains adequate for our core objective: the model consistently recovers the essential triggering logic of the evaluated vulnerabilities, with no missed detections attributable to minor behavioral discrepancies. Furthermore, the decompiled code is syntactically valid and preserves complete core semantics, enabling static analyzers to reliably identify vulnerability patterns—the reduced pass rate affects only executability, not the suitability for vulnerability detection. To further improve functional fidelity, we plan to incorporate more high-optimization-level samples into fine-tuning and refine inference-time decoding strategies.

From an engineering deployment perspective, three core scenarios require attention, representing specific extensions of cross-architecture/compiler adaptability, the first of which is the impact of compiler optimization levels. O2/O3 optimizations can lead to the simplification and merging of assembly instructions, potentially reducing the model’s semantic restoration accuracy. Consequently, supplementing a small amount of fine-tuning data from optimized samples is necessary. The second issue that requires attention relates to cross-scenario adaptation details. For binary files in embedded scenarios (ARM+GCC) and server scenarios (x86-64+Clang), only the training data corresponding to the target architecture/compiler needs to be replaced, with no modifications required for the core framework. Thirdly, efficiency adaptation requirements must be addressed. Static detection tools are sensitive to input-code redundancy; thus, the LLM must control redundant comments and invalid statements when generating C code to avoid slowing down the detection process.

When contextualizing this study within the broader binary security tool ecosystem, there is an increasing industrial demand for toolchain automation and end-to-end processing. Traditional tools rely on manual integration between decompilation and detection, resulting in low efficiency. Other LLM-based decompilation tools primarily focus on code restoration itself and lack optimization for vulnerability detection scenarios. LLMVulDecompiler precisely fills this gap by enabling seamless integration between decompilation and vulnerability detection, aligning with the industry’s core needs of reducing human intervention and improving implementation efficiency. It thereby serves as a critical supplement to and optimization of existing binary security tool chains.

Despite the aforementioned advantages in experimental design and tool adaptability, this study has two limitations: First, the current vulnerability test set includes 12 CVE instances (included in accuracy statistics) and 8 non-CVE instances (for auxiliary verification), covering only 5 high-risk vulnerability types. The sample size is insufficient to fully validate the model’s generalization ability. Second, quantitative analysis of the impact of different sample sizes on detection metrics was not conducted. Both limitations stem from the challenges in acquiring real binary vulnerability samples, experimental cycle constraints, and resource limitations. It should also be noted that this work does not include rigorous ablation studies to isolate and quantify the individual contributions of key components—such as the two-stage fine-tuning strategy or the inclusion of vulnerability-specific training samples. Addressing this methodological gap is a priority for future work: we plan controlled experiments comparing “single-stage vs. two-stage” fine tuning and “with vs. without vulnerability samples” to precisely measure the marginal gains of each module. To further mitigate current limitations, we will expand both the quantity and diversity of vulnerability samples through collaborations with security vendors and systematic curation from public vulnerability databases, and we will supplement our evaluation with sensitivity analyses on the scale of training data.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.M.; methodology, D.M.; software, Y.W.; validation, Y.W.; formal analysis, Y.W.; investigation, Y.W.; data curation, R.T.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.W.; writing—review and editing, Y.H.; visualization, Y.W.; supervision, D.M.; project administration, D.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Sichuan Provincial Major Scientific and Technological Special Project on Artificial Intelligence under Grant 2024ZDZX007. The APC was funded by the 30th Research Institute of China Electronics Technology Group Corporation.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the First Author, Yidan Wang, upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to extend their sincere gratitude to all editors and anonymous reviewers for their insightful comments and constructive suggestions, which have greatly contributed to the refinement of this study. The authors also acknowledge, with thanks, the 30th Research Institute of China Electronics Technology Group Corporation and the departmental research group for their valuable support during the entire research process.

Conflicts of Interest

All authors were employed by the company The 30th Research Institute of China Electronics Technology Group Corporation. The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Appendix A.1. Analysis of the Successful Case

Figure A1.

Successful decompilation case (func0).

Figure A1.

Successful decompilation case (func0).

The model achieves accurate restoration of the original code through three key aspects. First, it fully reproduces the double-loop logic, correctly capturing the iterative relationship. where the outer-loop variable (i) ranges from 0 to and the inner-loop variable (j) ranges from to . Second, it accurately identifies the fabs function call and the difference calculation logic of array elements, restoring the core expression for the absolute value of the difference between array elements [i] and [j]. Third, it precisely matches the conditional judgment and return-value logic, completely reproducing the functional logic of returning 1 when the threshold condition is met and returning 0 if no matching condition is found after traversing all elements.

This case confirms the model’s solid grasp of basic C-language syntax. Through large-scale assembly–source code paired training during the basic capability foundation stage, the model establishes a stable mapping relationship between general syntax structures and assembly instructions, enabling it to efficiently restore conventional code logic without complex semantic dependencies.

Appendix A.2. Analysis of the Failed Case

In this vulnerability scenario, the model exhibits three core semantic distortions, ultimately resulting in a false positive. First, it misjudges the structure type: the standard structure type (struct cmsghdr) of the input parameter is incorrectly identified as the fictional struct rds_connection, undermining the foundation for all subsequent offset calculations based on structure members. Second, the core offset logic is distorted: the additive calculation between cmsg->cmsg_data and the fixed offset of in the original code is erroneously replaced with the sum of conn->cmsg_buffer and the size of struct rds_cmsg_header. This not only confuses the structure members (cmsg_data and cmsg_buffer) but also incorrectly substitutes the fixed offset of with structure size calculation. Third, there is a deviation in the assignment target: the assignment to the local_addr member of the args structure in the original code is mistakenly mapped to the cmsg_flags member of the hdr structure, completely deviating from the core operation object of the vulnerability.

Figure A2.

Failed decompilation case (CVE-2018-5333).

Figure A2.

Failed decompilation case (CVE-2018-5333).

This case exposes a critical shortcoming of the model: when facing concealed pointer offset scenarios that combine structure member access and fixed offset calculation, the model fails to accurately parse the implicit association between structure semantics and memory layout in assembly instructions due to the lack of targeted training. In the assembly code, mov 0x10(%rax),%rax corresponds to the member offset access of cmsg->cmsg_data, and add $0x18,%rax corresponds to fixed-offset superposition. The model fails to correlate these two instructions with the structure member access logic, ultimately leading to complete distortion of semantic restoration. This also confirms the necessity of supplementing training data for complex structures and concealed offset scenarios in the vulnerability feature enhancement stage.

References

- Wei, X.; Yan, Z.; Liang, X. A survey on fuzz testing technologies for industrial control protocols. J. Netw. Comput. Appl. 2024, 232, 104020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutra, R.; Gopinath, R.; Zeller, A. Formatfuzzer: Effective fuzzing of binary file formats. ACM Trans. Softw. Eng. Methodol. 2023, 33, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poeplau, S.; Francillon, A. SymQEMU: Compilation-based symbolic execution for binaries. In Proceedings of the Ndss 2021, Network and Distributed System Security Symposium, Virtually, 21–25 February 2021. [Google Scholar]

- He, J.; Sivanrupan, G.; Tsankov, P.; Vechev, M. Learning to explore paths for symbolic execution. In Proceedings of the 2021 ACM SIGSAC Conference on Computer and Communications Security, Virtually, 15–19 November 2021; pp. 2526–2540. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, P.; Zheng, Z.; Luo, X. Park: Accelerating smart contract vulnerability detection via parallel-fork symbolic execution. In Proceedings of the 31st ACM SIGSOFT International Symposium on Software Testing and Analysis, Virtual, 18–22 July 2022; pp. 740–751. [Google Scholar]

- Sang, Q.; Wang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Jia, X.; Bao, T.; Su, P. Airtaint: Making dynamic taint analysis faster and easier. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE Symposium on Security and Privacy (SP), San Francisco, CA, USA, 20–23 May 2024; pp. 3998–4014. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Y.; Gao, C.; Li, Z.; Wang, Y.; Wang, R. Binary level concolic execution on windows with rich instrumentation based taint analysis. In Proceedings of the International Symposium on Dependable Software Engineering: Theories, Tools, and Applications, Nanjing, China, 27–29 November 2023; pp. 351–367. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Z.; Chen, C.; Ejaz, A.; Liu, D.; Zhang, J. Automated binary analysis: A survey. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Algorithms and Architectures for Parallel Processing, Copenhagen, Denmark, 10–12 October 2022; pp. 392–411. [Google Scholar]

- Haq, I.U.; Caballero, J. A survey of binary code similarity. ACM Comput. Surv. CSUR 2021, 54, 1–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Xu, Z.; Xiao, Y.; Lang, Z.; Tang, W.; Liu, Y.; Shi, Z.; Li, H.; Sun, L. Towards practical binary code similarity detection: Vulnerability verification via patch semantic analysis. ACM Trans. Softw. Eng. Methodol. 2023, 32, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massarelli, L.; Di Luna, G.A.; Petroni, F.; Querzoni, L.; Baldoni, R. Function representations for binary similarity. IEEE Trans. Dependable Secur. Comput. 2021, 19, 2259–2273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fevid, E.; Walsh, C.; Russo, L. Zero-day ransomware detection via assembly language bytecode analysis and random forest classification. Authorea Prepr. 2024. Available online: https://www.techrxiv.org/doi/full/10.36227/techrxiv.172565769.90012316 (accessed on 16 December 2025).

- Yan, H.; Luo, S.; Pan, L.; Zhang, Y. HAN-BSVD: A Hierarchical Attention Network for Binary Software Vulnerability Detection. Comput. Secur. 2021, 108, 102286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Y.; Xu, Z.; Zhang, W.; Yu, C.; Liu, L.; Zou, W. VIVA: Binary Level Vulnerability Identification via Partial Signature. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE International Conference on Software Analysis, Evolution and Reengineering (SANER), Honolulu, HI, USA, 9–12 March 2021; pp. 213–224. [Google Scholar]

- Burk, K.; Pagani, F.; Kruegel, C.; Vigna, G. DECOMPERSON: How Humans Decompile and What We Can Learn From It. In Proceedings of the 31st Usenix Security Symposium, Boston, MA, USA, 10–12 August 2022; pp. 2765–2782. [Google Scholar]

- Hex-Rays SA. IDA Pro: A Cross-Platform Multi-Processor Disassembler and Debugger. 2025. Available online: https://hex-rays.com/ida-pro/ (accessed on 16 December 2025).

- National Security Agency (NSA). Ghidra (Open-Source Reverse Engineering Tool). 2021. Available online: https://www.nsa.gov/resources/everyone/ghidra/ (accessed on 16 December 2025).

- Verbeek, F.; Naus, N.; Ravindran, B. Verifiably Correct Lifting of Position-Independent x86-64 Binaries to Symbolized Assembly. In Proceedings of the 2024 ACM Sigsac Conference on Computer and Communications Security, 31st Conference on Computer and Communications Security, Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 14–18 October 2024; pp. 2786–2798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engel, D.; Verbeek, F.; Ravindran, B. BIRD: A binary intermediate representation for formally verified decompilation of X86-64 binaries. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Tests and Proofs, Leicester, UK, 18–19 July 2023; pp. 3–20. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, Z.; Wang, P.; Wang, B.; Tang, Y.; Xie, W.; Zhou, X.; Liu, D.; Lu, K. VulHawk: Cross-architecture vulnerability detection with entropy-based binary code search. In Proceedings of the NDSS, San Diego, CA, USA, 27 February–3 March 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Li, D.; Liu, Y.; Huang, J. Assessment of software vulnerability contributing factors by model-agnostic explainable AI. Mach. Learn. Knowl. Extr. 2024, 6, 1087–1113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chukkol, A.H.A.; Luo, S.; Sharif, K.; Haruna, Y.; Abdullahi, M.M. Vulcatch: Enhancing binary vulnerability detection through codet5 decompilation and kan advanced feature extraction. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2408.07181. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Xu, T.; Wang, C. IRaDT: LLVM IR as Target for Efficient Neural Decompilation. Int. J. Softw. Eng. Knowl. Eng. 2024, 34, 1971–1992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katz, O.; Olshaker, Y.; Goldberg, Y.; Yahav, E. Towards neural decompilation. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1905.08325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brumley, D.; Lee, J.; Schwartz, E.J.; Woo, M. Native x86 decompilation using Semantics-Preserving structural analysis and iterative Control-Flow structuring. In Proceedings of the 22nd USENIX Security Symposium (USENIX Security 13), Washington, DC, USA, 14–16 August 2013; pp. 353–368. [Google Scholar]

- Wong, W.K.; Wang, H.; Li, Z.; Liu, Z.; Wang, S.; Tang, Q.; Nie, S.; Wu, S. Refining decompiled c code with large language models. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2310.06530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katz, D.S.; Ruchti, J.; Schulte, E. Using recurrent neural networks for decompilation. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE 25th International Conference on Software Analysis, Evolution and Reengineering (SANER), Campobasso, Italy, 20–23 March 2018; pp. 346–356. [Google Scholar]

- Li, R.; Allal, L.B.; Zi, Y.; Muennighoff, N.; Kocetkov, D.; Mou, C.; Marone, M.; Akiki, C.; Li, J.; Chim, J.; et al. Starcoder: May the source be with you! arXiv 2023, arXiv:2305.06161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roziere, B.; Gehring, J.; Gloeckle, F.; Sootla, S.; Gat, I.; Tan, X.E.; Adi, Y.; Liu, J.; Sauvestre, R.; Remez, T.; et al. Code llama: Open foundation models for code. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2308.12950. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, D.; Zhu, Q.; Yang, D.; Xie, Z.; Dong, K.; Zhang, W.; Chen, G.; Bi, X.; Wu, Y.; Li, Y.; et al. DeepSeek-Coder: When the Large Language Model Meets Programming–The Rise of Code Intelligence. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2401.14196. [Google Scholar]

- Hosseini, I.; Dolan-Gavitt, B. Beyond the c: Retargetable decompilation using neural machine translation. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2212.08950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armengol-Estapé, J.; Woodruff, J.; Cummins, C.; O’Boyle, M.F. Slade: A portable small language model decompiler for optimized assembly. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE/ACM International Symposium on Code Generation and Optimization (CGO), Edinburgh, UK, 2–6 March 2024; pp. 67–80. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, N.; Wang, C.; Liu, K.; Xu, X.; Tan, L.; Zhang, X. Nova+: Generative language models for binaries. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2311.13721. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, H.; Luo, Q.; Li, J.; Zhang, Y. Llm4decompile: Decompiling binary code with large language models. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2403.05286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Y.; Li, B.; Shi, X.; Zhu, Q.; Che, W. Interactive End-to-End Decompilation via Large Language Models. Electronics 2025, 14, 4442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- She, X.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, H. Wadec: Decompiling webassembly using large language model. In Proceedings of the 39th IEEE/ACM International Conference on Automated Software Engineering, Sacramento, CA, USA, 27 October–1 November 2024; pp. 481–492. [Google Scholar]

- WPeace-HcH. WPeChatGPT Version 2.3. 2023. Available online: https://github.com/WPeace-HcH/WPeChatGPT (accessed on 20 October 2025).

- Armengol-Estapé, J.; Woodruff, J.; Brauckmann, A.; Magalhaes, J.W.d.S.; O’Boyle, M.F. ExeBench: An ML-scale dataset of executable C functions. In Proceedings of the 6th ACM SIGPLAN International Symposium on Machine Programming; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2022; pp. 50–59. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, Y.; Zhang, R.; Zhang, J.; Ye, Y.; Luo, Z.; Feng, Z.; Ma, Y. Llamafactory: Unified efficient fine-tuning of 100+ language models. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2403.13372. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, M. Evaluating large language models trained on code. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2107.03374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ByteDance. Doubao. AI Chatbot. 2024. Available online: https://www.doubao.com (accessed on 16 December 2025).

- Hui, B.; Yang, J.; Cui, Z.; Yang, J.; Liu, D.; Zhang, L.; Liu, T.; Zhang, J.; Yu, B.; Dang, K.; et al. Qwen2. 5-Coder Technical Report. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2409.12186. [Google Scholar]

- BigCode Project. StarCoder2. 2024. Available online: https://github.com/bigcode-project/starcoder2 (accessed on 16 December 2025).

- Meta. Code Llama. Official Webpage for Code Llama, a Code Generation LLM Developed by Meta. 2023. Available online: https://www.llama.com/code-llama/ (accessed on 16 December 2025).

- Ollama. Wizard Coder. Ollama Library Webpage for Wizard Coder (Code Generation Model Based on Code Llama); Multiple Versions Available: Initial Release (2023-09-07) and 33B Version (2024-01-04). 2023. Available online: https://ollama.com/library/wizardcoder (accessed on 16 December 2025).

- Tencent. CodeAnalysis. 2025. Available online: https://github.com/Tencent/CodeAnalysis (accessed on 3 November 2025).

| Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |