1. Introduction

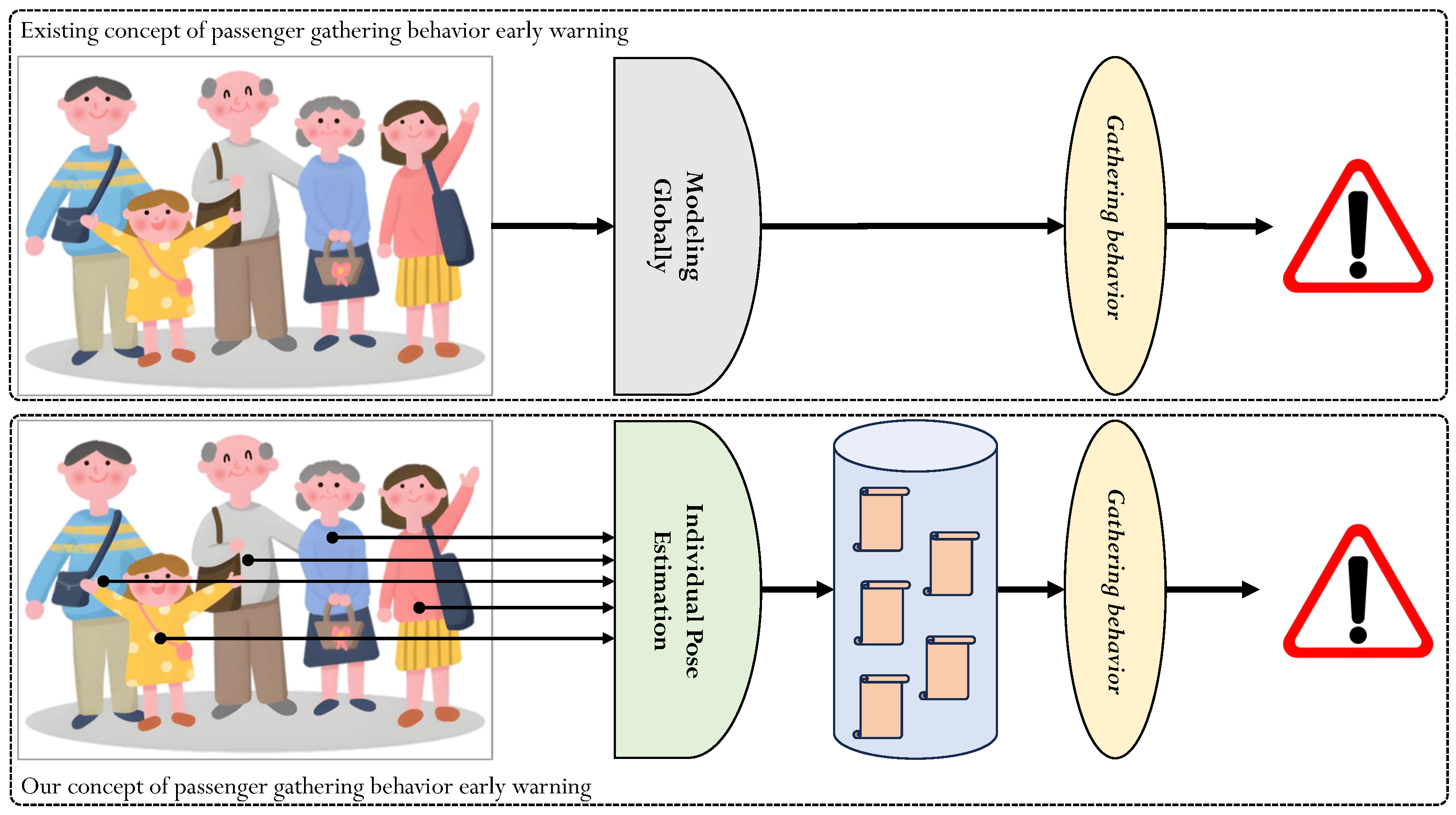

Passenger-gathering behavior (as shown in

Figure 1) is often associated with risks such as traffic congestion and stampede incidents, and the early warning of such behavior in scenarios like airports and high-speed railway stations plays a crucial role in intelligent transportation, safe travel, and related fields [

1]. In recent years, with the rapid advancement of software and hardware technologies, deep neural network (DNN)-based methods have demonstrated highly competitive performance in numerous computer vision tasks [

2], including early warning of passenger-gathering behavior. However, in recent years, existing approaches to passenger-gathering behavior warning have primarily focused on organizing and modeling images containing passengers and conducting gathering-behavior analysis solely from the perspective of global features. However, these methods largely overlook the influence of individual actions and interactions among different pedestrians in the images on the formation and evolution of collective gathering behavior. Due to the lack of accurate capture and in-depth mining of discriminative individual-level information (e.g., key postures, movement trends, and interaction patterns of typical individuals) in the visual data, the aforementioned frameworks fail to establish a reliable connection between individual behaviors and the underlying causes of passenger gathering. This deficiency not only leads to insufficient interpretability in assessing the triggers for event collection but also results in significant issues, such as high false-negative and false-positive rates in practical early-warning applications, which severely restrict the deployment and promotion of related technologies in real-world scenarios.

In this case, we divide the passenger behavior early warning task into two components: individual human pose estimation [

3,

4] and group behavior analysis (the comparisons of existing and our concepts for passenger-gathering behavior early warning are shown in

Figure 2). The former aims to estimate the pose and action information of each individual passenger in the image or video, while the latter focuses on the information interaction and integration among different individual features. Given the mature advancement of data fusion, feature fusion, and decision fusion technologies, this paper focuses on the estimation of individual poses within a group in practical 3D physical spaces [

5]. Given the large number of passengers in a single image, sequentially estimating the 3D pose of each individual using existing methods is not only time-consuming and computationally expensive but also fails to meet the requirements of practical applications.

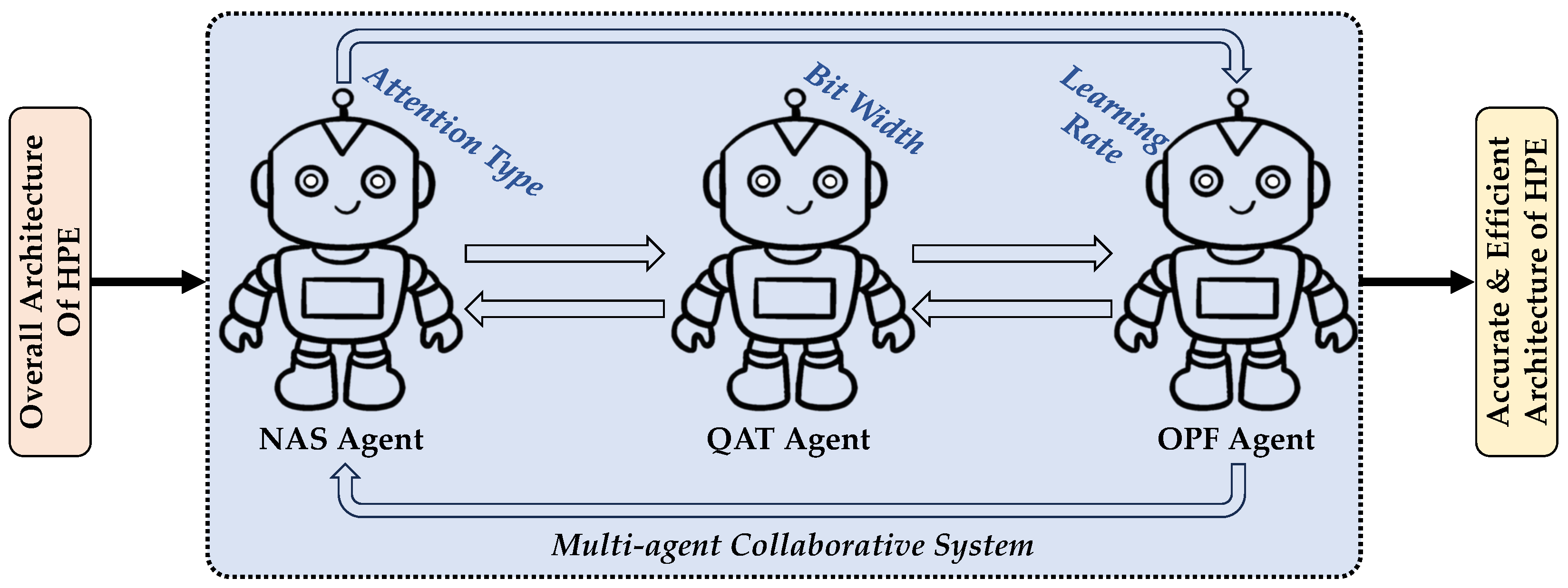

To address this problem, we present a multi-agent collaboration method for 3D human pose estimation. It utilizes the joint training of the architecture search (AS) agent, optimization feedback (OF) agent, and model quantization (MQ) agent to realize the dynamical balance of performance and computation loads. Specifically, the AS agent uses reinforcement learning to select optimal attention types for each block to construct a compact neural network architecture and avoid redundant connections and computations. The OF agent monitors validation performance after each training epoch and dynamically adjusts the AS agent’s learning rate based on the monitoring results. The MQ agent injects simulated quantization nodes to enable the model to learn parameter representations that are resilient to low-precision perturbations and further realize the parameter reduction. Together, these three agents operate cooperatively across different training phases, forming a full-cycle closed-loop optimization system that seamlessly integrates architecture design, performance tuning, and deployment readiness. In summary, the contributions of this work can be summarized as follows:

We discuss a concept that divides early warning of passenger-gathering behavior into individual pose estimation and group behavior recognition, and analyze its feasibility and potential theoretically.

We present a 3D human pose estimation method based on multi-agent collaboration that effectively balances performance, parameter scale, and computational load through joint training.

We conduct a series of experiments on the public 3D pose estimation dataset Human3.6M, and the experimental results have shown the efficiency, effectiveness, and superiority of our method.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows:

Section 2 details the proposed 3D human pose estimation method based on multi-agent collaboration.

Section 3 reports the experiments from different perspectives.

Section 4 concludes the paper.

2. Proposed Method

This chapter presents the proposed IHMP (Intelligent Hybrid Multi-agent 3D Pose estimation framework, abbreviated as IHMP), and its overview flowchart is shown in

Figure 3. The core idea is to integrate three specialized agents, the architecture search agent, the optimization feedback agent, and the model quantization agent, to collaboratively design, train, and compress a high-performance pose estimation model in an automated and efficient manner. The chapter is organized as follows: we first introduce the overall system architecture, then detail the hybrid spatio-temporal Transformer network, followed by a discussion of the internal mechanisms of the three agents. Finally, we elaborate on the experimental setup, datasets, evaluation metrics, and implementation details and provide an analysis of the results.

2.1. Framework Overview

To address the simultaneous demands for high accuracy, computational efficiency, and model compactness in 3D human pose estimation, we propose a multi-agent collaborative framework that combines a two-stage training paradigm with three core functional agents. The goal is to produce a lightweight and deployable model optimized for pose estimation.

To balance model accuracy, search efficiency, and deployment performance, we design a Two-Stage Training Paradigm that seamlessly integrates architecture optimization and quantization-aware training (QAT). This paradigm combines reinforcement learning, feedback-based adaptation, and lightweight compression into a unified and automated framework.

2.1.1. Stage 1, Floating-Point Pretraining and Architecture Search

In the first stage, the model is trained with full precision (FP32), during which a reinforcement learning-based architecture search agent dynamically selects the optimal attention mechanism, choosing between global self-attention, windowed attention, and external attention for each Transformer block to minimize the pose estimation error. Moreover, a feedback optimization agent monitors MPJPE validation and adaptively adjusts the learning rate of architecture parameters to balance exploration and convergence. This stage not only initializes the model with supervised learning but also adaptively optimizes its structure under multiple constraints, such as bone-length consistency, anatomical symmetry, and temporal smoothness.

2.1.2. Stage 2, Quantization-Aware Fine-Tuning (QAT)

Once the optimal architecture is found, the model quantization agent is introduced. In the second stage, quantization-aware training is introduced to compress the model into an INT8 format while maintaining high accuracy. During QAT, the model simulates quantization effects in forward passes and learns to adapt to these perturbations through gradient-based optimization. After training, the function finalizes the quantization by combining operations and replacing layers with their efficient quantized counterparts, producing a lightweight, deployment-ready model optimized for INT8 inference on edge devices. This two-stage approach not only enhances precision and generalization but also achieves substantial compression and inference acceleration, offering a robust solution for real-world deployment. For Multi-Agent Collaboration Mechanism:

Architecture Search Agent: It utilizes reinforcement learning to dynamically select attention mechanisms within each Combined-Attention Block Guided by a learnable controller (RLController), the agent makes discrete decisions—via Gumbel-Softmax sampling—among global self-attention, windowed attention, and external attention for each block. These selections are driven by validation performance, with the MPJPE score serving as a reward signal. Through repeated exploration and policy updates, the agent gradually converges towards an architecture that is structurally optimized for the 3D pose estimation task.

Optimization Feedback Agent: The agent serves as a lightweight heuristic meta-controller that monitors the model’s validation accuracy after each epoch. It adjusts the learning rate of architecture parameters based on whether the current MPJPE exceeds or meets a predefined threshold. If performance lags behind, it increases the learning rate to promote exploration; if the model meets expectations, it decreases the rate to encourage stable convergence. This adaptive feedback mechanism enhances both robustness and efficiency during the architecture search process.

Model Quantization Agent: It becomes active during the second training stage, handling the transformation of the floating-point model into a compact INT8 version. By injecting simulated quantization nodes (FakeQuantize) and performing quantization-aware training, this agent enables the model to learn parameter representations that are resilient to low-precision perturbations. Upon completion, the model is finalized using the convert() function, which fuses operations and replaces standard modules with quantized counterparts. The result is a model with drastically reduced computational cost and memory footprint, while preserving inference accuracy.

Additionally, a dynamic token selection mechanism (DPC-KNN) is integrated to focus on informative frames, compress intermediate features, and reduce redundant computation. Together, these components form an end-to-end automated pipeline that starts from a flexible super-network and, through coordinated agent decisions, outputs a compact model optimized for deployment.

2.2. Hybrid Spatio-Temporal Feature Collaborative Network

The backbone architecture for 3D pose estimation is a hybrid attention spatial-temporal transformer. It is capable of efficiently extracting spatio-temporal features and offers structural flexibility. The network captures both spatial dependencies between joints and temporal relationships across frames and uses dynamic attention mechanisms and frame-level focus strategies to perform effective sequence modeling.

The model takes a sequence of 2D joint coordinates as input, shaped as

, where

B is the batch size,

F is the number of frames,

N is the number of joints, and 2 denotes the coordinates. The architecture comprises three main components: an input embedding module, alternating spatial and temporal Transformer encoder blocks, and a final prediction head. To enhance representation power and incorporate spatial-temporal positional information, 2D coordinates are projected into a high-dimensional space and augmented with learnable position embeddings. Each 2D joint coordinate

is first projected into a

D-dimensional embedding space via a linear transformation defined in Equation (

1).

This is implemented as a shared weight linear layer, and the output tensor has the shape

. To enable the model to perceive the order of joints and frames, we introduce encodings of learnable spatial and temporal position, denoted as

and

, respectively. These encodings are added to the corresponding spatial and temporal embeddings before being passed to the downstream modules. After embedding, a dropout layer is applied to regularize the input and mitigate overfitting.

In addition, the core idea of the model is to process data through a series of alternating space-time encoder (STE/TTE) blocks: the data are reshaped into the form , allowing all joints within each frame to interact with one another. A spatial Transformer encoder (STEBlock) is applied to capture the spatial structural relationships between joints. Subsequently, the data is reshaped into , so that the trajectories of each joint across all time frames can be processed independently. A temporal Transformer encoder (TTEBlock) is employed to capture the motion dynamics of each joint. This interleaved design allows the model to build increasingly complex spatio-temporal representations across different hierarchical levels. To flexibly model spatiotemporal dependencies under various scenarios, we propose a novel Combined-Attention Block. Instead of statically selecting one specific attention mechanism, this module dynamically chooses among three candidate attention types within each layer: Global Self-Attention, Window Attention, and External Attention. This provides great adaptability and expressive power while balancing accuracy and efficiency.

2.2.1. Global Self-Attention

This is the standard self-attention mechanism used in Transformers. Calculate the attention weights between all elements in the input sequence. Given the input

. Query

K, key

K, and value

V are calculated with Equation (

2):

Attention Weight (Scaled Dot-Product Attention) can be calculated with Equation (

3):

where

,

L is the sequence length, and

is the key dimension.

2.2.2. Window Attention

To reduce computational cost, window attention restricts attention computation within non-overlapping local windows, which is efficient for local interactions (e.g., adjacent joints or consecutive frames) but may miss global dependencies. Start by transforming the

Q,

K, and

V for each window with Equation (

4):

Secondly, calculate the attention in the local window with Equation (

5):

Linear projection with Equation (

6) after stitching of the results:

2.2.3. External Attention

This is a lightweight alternative attention mechanism that allows global interaction via a set of shared memory units, implicitly encoding interactions between all positions. First, map the query feature into the external attention space with Equation (

7):

Then normalize each column with Equation (

8):

Finally, map back to the original dimension with Equation (

9):

In the

Combined-Attention Block, Self attention focuses on the fine extraction of local features, External attention expands the context range of feature extraction, and Window attention helps capture richer details within local areas. This multi-angle feature-extraction strategy enables the model to achieve more accurate human pose estimation while maintaining a lower computational cost. The task of the architectural search agent is to determine which attention mechanism should be activated at the current training stage for each instance in the model.

2.3. Core Agent Design

This section provides an in-depth explanation of the internal mechanisms of the three core agents that drive the entire framework.

2.3.1. Architecture Search Agent-A Reinforcement Learning-Based Decision Maker

This agent is implemented using the RLController (our reinforcement-learning controller based on the REINFORCE algorithm) module, modeled as a policy network and trained using the REINFORCE algorithm (Monte Carlo policy gradient). Its goal is to select the optimal attention mechanism for each of the Combined-Attention Block (including STE and TTE) from the candidate set {Global Self-Attention, Window Attention, External Attention} in order to minimize 3D pose estimation error.

In the current design, we adopt a stateless policy design. The controller takes a one-hot vector indicating the index of the current block being processed. This design implies that the decisions for each block are independent and do not depend on the input data features. For each block, the action space is a discrete set

representing the three candidate attention types. The policy

is modeled by a multi-layer perceptron (MLP) in

RLController. For each block index

, the MLP outputs a 3-dimensional logits vector, and we use the

Gumbel-Softmax trick defined in Equation (

10) to enable differentiable discrete sampling during the training phase.

where

is the

i-th logit and

, with

sampled from a uniform distribution. During training, the forward pass uses a hard one-hot sample while the backward pass uses the soft Gumbel distribution.

The reward is sparse and only computed once per training epoch, based on the negative MPJPE (Mean Per Joint Position Error) defined in Equation (

11) on the validation set:

This directly transforms the minimization of validation error into a reward maximization problem in reinforcement learning. The expected cumulative reward is defined in (

12):

and its gradient is computed using Equation (

13):

where

D is the total number of decision steps (i.e., blocks), and

is the selected action for the

t-th block. The loss function is defined in Equation (

14):

where

is a small constant for numerical stability. The parameters are optimized using an independent Adam optimizer.

2.3.2. Optimization Feedback Agent-A Heuristic Meta Learning Rate Regulator

This agent is a simple rule-based meta-controller. Its goal is to accelerate and guide the architecture search process by adaptively adjusting the learning rate of the search agent. The key idea is to avoid premature convergence to suboptimal solutions or inefficient exploration of unpromising regions by dynamically tuning the search agent’s learning rate to maintain a balance between exploration and exploitation. This agent is triggered at the end of each epoch. It compares the model’s current performance on the validation set, denoted as p1_val (i.e., MPJPE), against a predefined target performance target_mpjpe.

If

, this indicates that the model’s performance has not yet reached the target. The agent considers the current architecture ineffective and that further exploration is needed. Thus, it increases the learning rate of the architecture search agent according to Equation (

15):

A higher learning rate allows the RL policy to perform larger updates, helping escape suboptimal regions and explore more diverse architectures. If

, This indicates that the model meets or surpasses the target performance. The agent considers the current architecture promising and calls for fine-grained exploitation. Thus, it decreases the learning rate according to Equation (

16):

A smaller learning rate facilitates stable convergence of the RL policy in promising regions, avoiding overshooting and preserving favorable structures. This feedback loop acts as a meta-layer that guides the behavior of the search algorithm itself based on the task performance, improving adaptability and robustness.

2.3.3. Model Quantization Agent-A Deployment-Oriented Compression Expert

This agent is responsible for transforming a trained floating-point model into an INT8 quantized model suitable for efficient inference via Quantization-Aware Training (QAT). Compared with Post-Training Quantization (PTQ), QAT significantly reduces the accuracy loss caused by quantization. The goal is to achieve substantial model compression and hardware acceleration while maintaining prediction accuracy by leveraging INT8 computing units. Before the second stage of training we invoke

prepare_qat(model) to process the model, which traverses the model graph and inserts three key nodes before and after quantization-sensitive layers. We quantize the incoming floating-point activations using Equation (

17):

where

s is the scale and

z is the zero point. Then we dequantize the outgoing INT8 values back to float with Equation (

18):

This is the core of QAT. In the forward pass, it simulates the quantize → dequantize process using Equation (

19):

This operation preserves float computation but mimics the quantization noise to make the model aware of it. Training continues with fake quant nodes inserted, and backpropagation uses STE defined in Equation (

20):

Though the forward pass uses quantized weights, the model still receives gradient updates on the original float weights. The model learns to adjust its parameters to compensate for quantization noise by minimizing the loss defined in Equation (

21):

During training, we apply PoseMixup with probability mixup_prob. This technique linearly interpolates two pose samples to generate new synthetic training data and enhance generalization. Through these steps, we obtain a final, deployable, high-performance INT8 model that can run on quantization-compatible CPUs or AI accelerators. After training, we call convert(model), which combines adjacent layers into a more efficient single fused operator and replaces float modules (e.g., nn.Linear) with INT8 equivalents (e.g., nn.quantized.Linear).

3. Experiments

3.1. Hardware and Dataset

The model is implemented using the PyTorch-CUDA-11.8 framework and trained/tested on an NVIDIA RTX 4090 (24GB VRAM) GPU. We base our work on the HoT and MixSTE architectures and extend them to the supported maximum frame lengths (e.g., ). We evaluate performance on the Human3.6M dataset, the most widely used indoor benchmark for 3D human pose estimation. Human3.6M includes 17 joints per pose, representing human skeletons. The dataset contains approximately 3.6 million video frames captured at 50 Hz using four RGB cameras. Eleven subjects perform 15 daily actions. We follow the standard training protocol by using S1, S5, S6, S7, S8 for training and S9, S11 for testing.

3.2. Evaluation Metrics

We adopt two metrics to evaluate model performance:

3.2.1. Per Joint Position Error (MPJPE)

This is the most commonly used metric, which calculates the average Euclidean distance between the predicted and ground-truth 3D joint positions, normalized by aligning the root joint (usually the pelvis). The formula is defined in Equation (

22):

where

J is the number of joints, and

are predicted and ground truth joint positions. Measured in millimeters.

3.2.2. Procrustes-Aligned MPJPE (P-MPJPE)

Based on MPJPE, this metric uses Procrustes analysis to align the predicted and ground-truth poses via rigid transformations (rotation, scaling, translation) to eliminate global misalignment. The formula is defined in Equation (

23):

where

is the optimal rigid transformation from Procrustes analysis.

3.3. Comparative Experiments

3.3.1. Contrasting Methods

To illustrate the effectiveness, efficiency, and superiority of the proposed method, we compare it with several existing ones, including PoseFormer [

6], Strided [

7], P-STMO [

8], STCFormer [

9], MHFormer [

10], MixSTE [

11], TPC w. MixSTE [

12], HoT w. MixSTE [

12], TPC w. MHFormer [

12].

3.3.2. Comparative Results

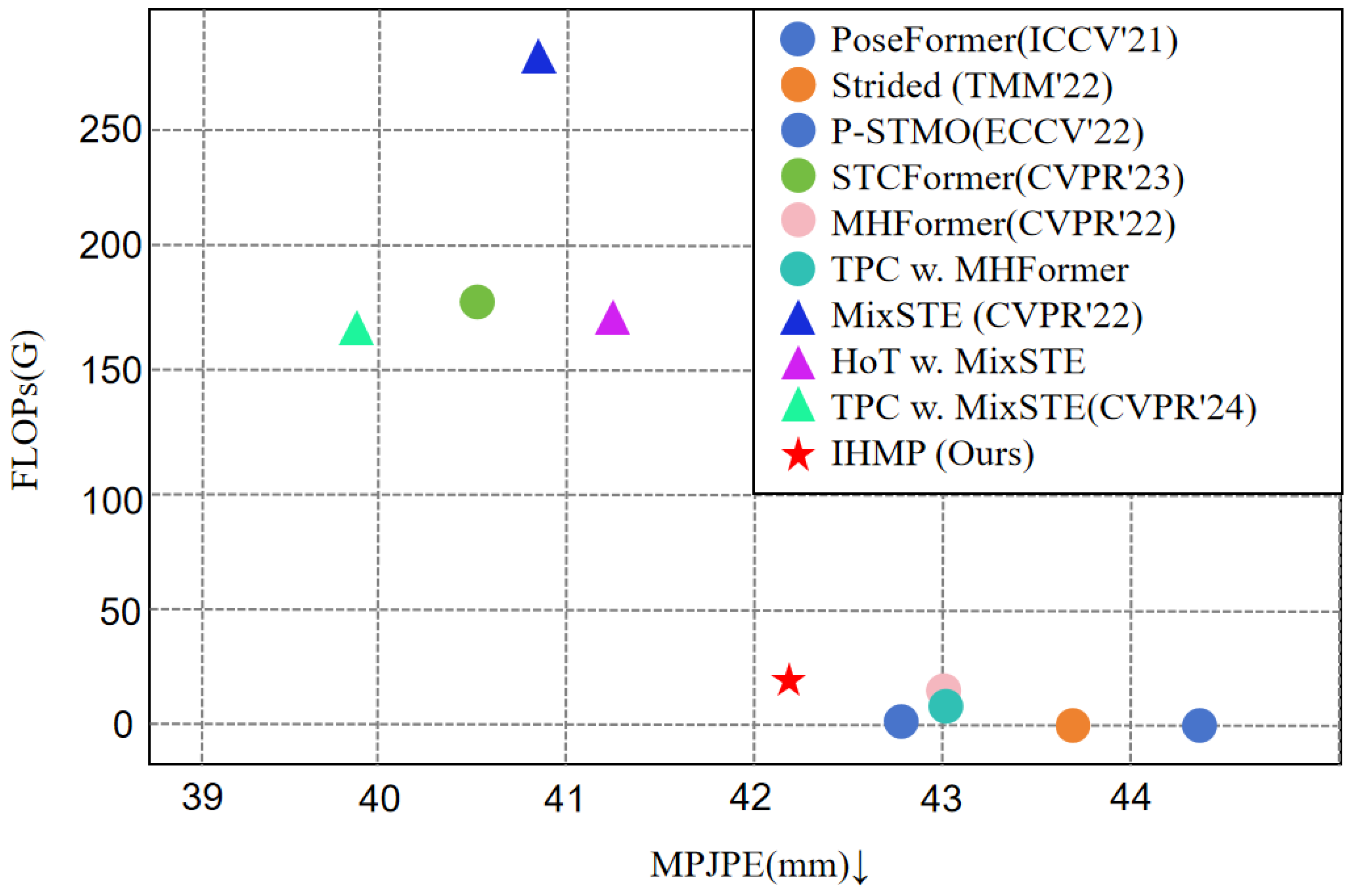

Table 1 summarizes the parameter count, FLOPs, and accuracy of IHMP compared with ten state-of-the-art methods on the Human3.6M benchmark.

Figure 4 shows the FLOPs and MPJPE of different 3D pose estimation methods on Human3.6M. Our IHMP-FP32 model achieves 42.22 mm MPJPE with only 4.38 M parameters and 19.39 GFLOPs, representing a favorable trade-off between accuracy and efficiency. In comparison, PoseFormer (44.30 mm, 9.6 M, 1.63 G), P-STMO (42.80 mm, 7.01 M, 1.74 G), and GraphMLP (43.80 mm, 9.73 M, 0.36 G) require more parameters or yield higher errors despite lower FLOPs. For heavyweight architectures, such as MixSTE (40.89 mm, 33.78 M, 277.25 G) and STCFormer (40.50 mm, 18.93 M, 156.22 G), IHMP achieves slightly higher MPJPE but with 7.7× fewer parameters and up to 14× lower FLOPs, highlighting its efficiency advantage. Compared with HoT w. MixSTE (41.00 mm, 34.70 M, 167.52 G) and IHMP offer a significantly more compact design while maintaining competitive accuracy.

Notably, after quantization to INT8, IHMP achieves 42.15 mm MPJPE, which is slightly better than its FP32 counterpart. This improvement is reasonable because quantization-aware training (QAT) involves an additional fine-tuning process under simulated quantization noise. During this stage, the model still trains with FP32 precision while being exposed to quantization perturbations through fake-quantization nodes. Such noise injection acts as a form of regularization, enabling the model to enhance generalization and robustness to low-precision inference. Therefore, the observed performance gain reflects the stabilizing effect of QAT rather than a contradiction to common quantization outcomes. These results collectively confirm that IHMP achieves a favorable balance between accuracy, model compactness, and computational efficiency, highlighting its potential for practical 3D human pose estimation deployment.

3.4. Ablation Study

To comprehensively evaluate the contribution of each proposed component, we conduct ablation experiments focusing on two aspects. We assess the effect of progressively adding the three intelligent agents—Architecture Search Agent, Optimization Feedback Agent, and Quantization Agent—on top of the baseline multi-attention model. Results in

Table 2 show that introducing the Architecture Search Agent slightly improves MPJPE from 42.38 mm to 42.30 mm, demonstrating the benefit of dynamic attention selection. Adding the Feedback Agent further reduces MPJPE to 42.22 mm by stabilizing convergence. Incorporating the Quantization Agent (QAT) enables INT8 deployment with only a minor performance drop (44.10 mm). QAT alone introduces quantization noise without architectural adaptation, degrading accuracy; when combined with RL search and feedback, the model adapts to low-precision perturbations, recovering and slightly improving accuracy. The full model, integrating all three agents, achieves the best overall result of 42.15 mm MPJPE and 35.51 mm P-MPJPE, confirming the complementary benefits of the proposed components.

We examine the effect of the proposed two-stage training paradigm (Stage 1: FP32 architecture search; Stage 2: QAT fine-tuning). As reported in

Table 3, the static multi-attention baseline without quantization yields 42.38 mm MPJPE. Replacing static fusion with RL-based dynamic attention selection reduces MPJPE to 42.22 mm. Applying QAT after RL-based search (Ours-RL-QAT) preserves most of the accuracy (42.15 mm) while enabling efficient INT8 inference, demonstrating that our two-stage scheme maintains precision while achieving substantial model compression.

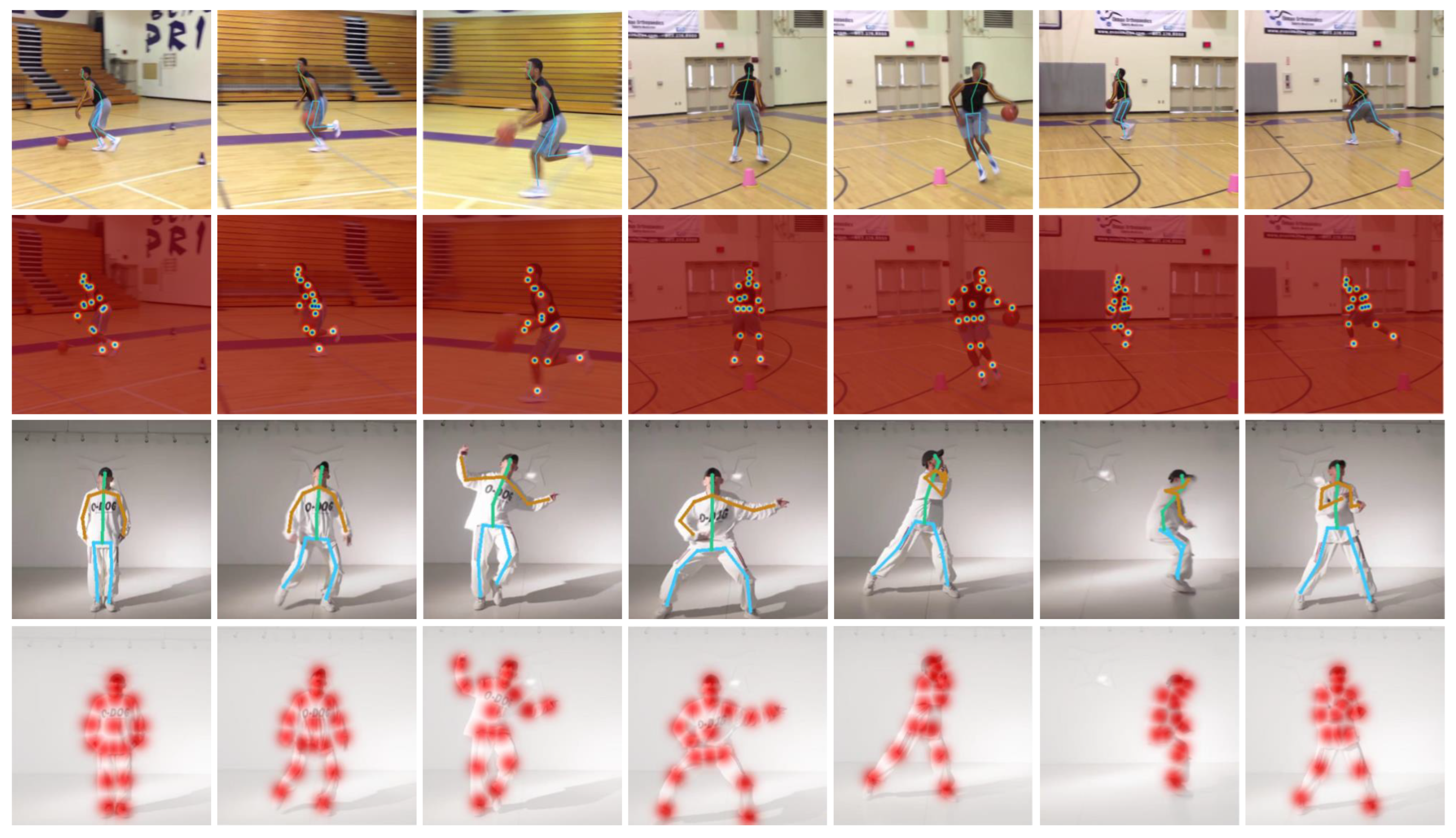

In

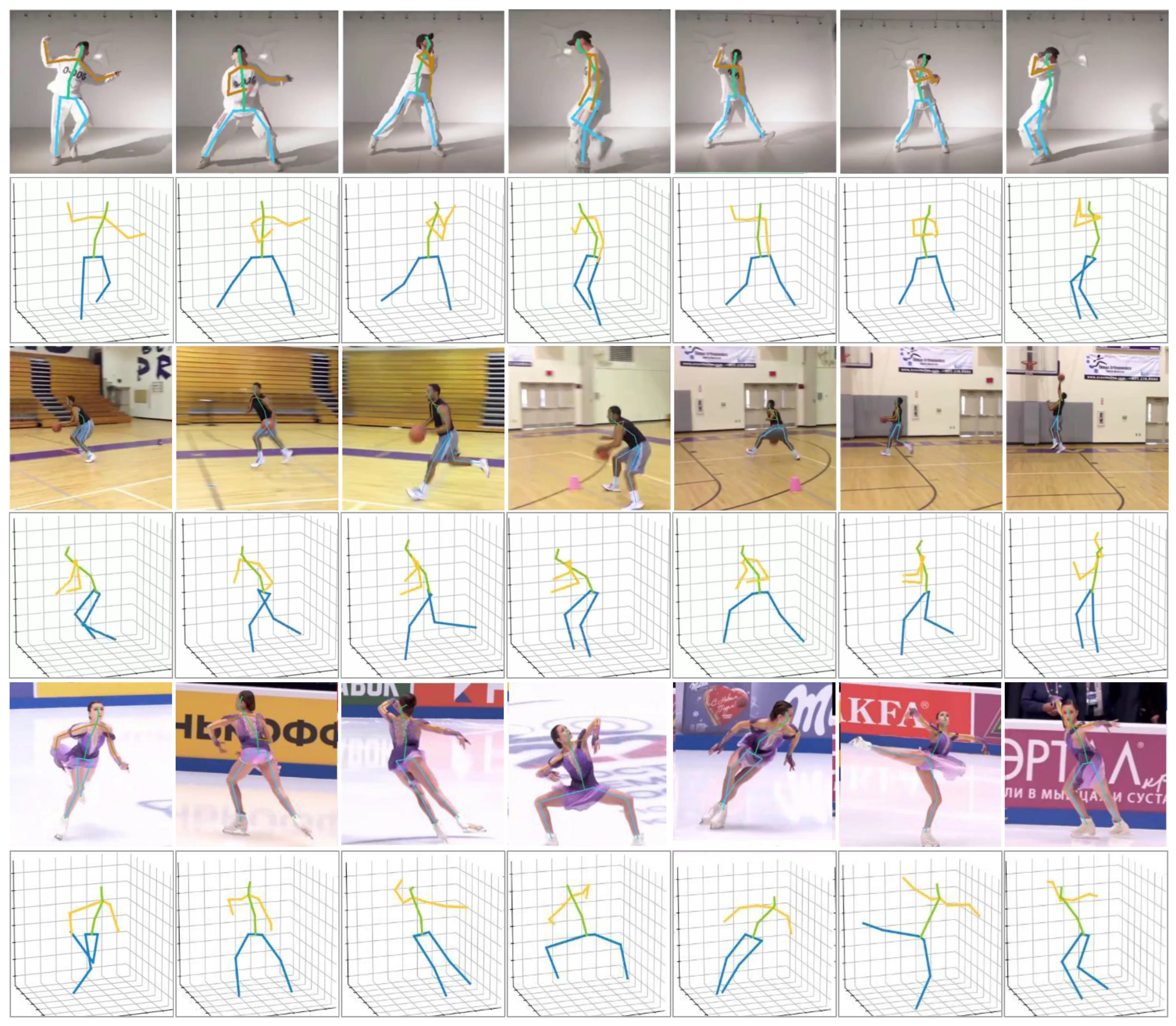

Figure 5, each pair of images from Human3.6M shows the predicted 3D pose projection and its corresponding heatmap, where each red activation indicates the probability distribution of a specific joint. The predicted joints maintain high spatial consistency with the ground truth across different motion types, demonstrating accurate localization.

Figure 6 shows results on the challenging in-the-wild videos. In in-the-wild videos, the method produces accurate skeletal predictions despite background clutter, occlusions, and dynamic motion, indicating strong generalization.

3.5. Efficiency Analysis

To analyze the efficiency of the proposed method, we tested it on NVIDIA RTX4090, Santa Clara, CA, USA and RockChip RK3588, Fuzhou, China, and the results are shown in

Table 4.

As evidenced by the results, even when deployed on the RockChip RK3588 edge device—where computational resources are inherently limited—our proposed method achieves a real-time inference speed of 30.9 FPS. This demonstrates that the efficiency of our method is sufficient to meet the requirements of practical applications in resource-constrained scenarios.

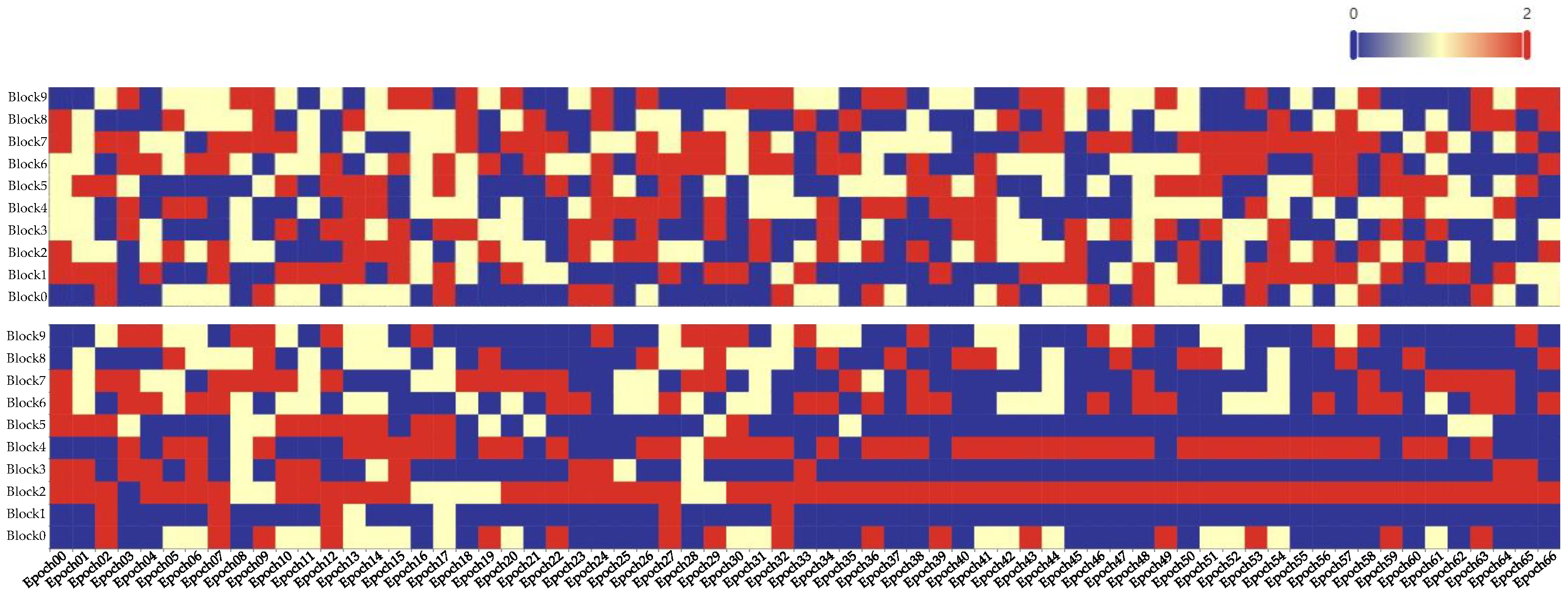

3.6. Process Visualization

The attention selection heatmaps of spatial and temporal blocks in different training epochs are shown in

Figure 7. From which we can see that, as the training progresses, the attention mechanism selection patterns across different modules tend to stabilize, which demonstrates the effectiveness of our architecture search agent.

4. Conclusions

This work addresses the inherent limitations of existing passenger-gathering behavior early warning methods that rely on global modeling, which often fail to capture fine-grained individual dynamics and contextual group interactions simultaneously. To mitigate this gap, we propose a novel two-stage framework that decouples the early warning task into individual pose estimation and group behavior recognition, enabling more precise modeling of passenger movements and collective patterns. As a key component of this framework, we develop a 3D human pose estimation approach based on multi-agent collaboration, comprising three specialized agents: an architecture search agent for efficient network design, an optimization feedback agent for adaptive parameter tuning, and a model quantization agent for resource-efficient deployment. Extensive experiments are conducted to validate the effectiveness and efficiency of the proposed method. Specifically, evaluations on the Human3.6M benchmark demonstrate that our approach achieves a competitive mean per-joint position error (MPJPE) of 42.15 mm, while maintaining a lightweight architecture with only 4.38 M parameters and 19.39 GFLOPs—outperforming many state-of-the-art methods in terms of accuracy-efficiency trade-offs. Furthermore, INT8 quantization of the proposed model results in minimal accuracy degradation (negligible performance loss) while achieving significant model compression, highlighting its potential for real-world deployment in resource-constrained scenarios.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, X.C. and H.L.; methodology, X.C.; software, J.F.; validation, J.F. and L.Y.; formal analysis, X.C. and J.F.; investigation, L.Y.; resources, H.L.; data curation, J.F.; writing—original draft preparation, X.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China, grant number 62201454.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Conflicts of Interest

Author Xirong Chen was employed by the company China Railway First Survey and Design Institute Group Co., Ltd. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Xu, J.; Shi, Y.; Zhang, H. Passengers gathering-scattering analysis at the corners of subway stations. Digit. Transp. Saf. 2023, 2, 139–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, J.; Cao, X.; Wang, D.; Xu, S. Multitask learning mechanism for remote sensing image motion deblurring. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2020, 14, 2184–2193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Tan, S.; Zhen, X.; Xu, S.; Zheng, F.; He, Z.; Shao, L. Deep 3D human pose estimation: A review. Comput. Vis. Image Underst. 2021, 210, 103225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; You, S.; Karaoglu, S.; Gevers, T. 3D human pose estimation and action recognition using fisheye cameras: A survey and benchmark. Pattern Recognit. 2025, 162, 111334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassanin, M.; Khamis, A.; Bennamoun, M.; Boussaid, F.; Radwan, I. Crossformer3D: Cross spatio-temporal transformer for 3D human pose estimation. Signal Image Video Process. 2025, 19, 618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, C.; Zhu, S.; Mendieta, M.; Yang, T.; Chen, C.; Ding, Z. 3d human pose estimation with spatial and temporal transformers. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, Tokyo, Japan, 18 March 2021; pp. 11656–11665. [Google Scholar]

- Li, W.; Liu, H.; Ding, R.; Liu, M.; Wang, P.; Yang, W. Exploiting temporal contexts with strided transformer for 3d human pose estimation. IEEE Trans. Multimed. 2022, 25, 1282–1293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shan, W.; Liu, Z.; Zhang, X.; Wang, S.; Ma, S.; Gao, W. P-stmo: Pre-trained spatial temporal many-to-one model for 3d human pose estimation. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision, Tel Aviv, Israel, 23–27 October 2022; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2022; pp. 461–478. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, Z.; Qiu, Z.; Hao, Y.; Hong, R.; Yao, T. 3d human pose estimation with spatio-temporal criss-cross attention. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 17–24 June 2023; pp. 4790–4799. [Google Scholar]

- Li, W.; Liu, H.; Tang, H.; Wang, P.; Van Gool, L. Mhformer: Multi-hypothesis transformer for 3d human pose estimation. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, New Orleans, LA, USA, 18–24 June 2022; pp. 13147–13156. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.; Tu, Z.; Yang, J.; Chen, Y.; Yuan, J. Mixste: Seq2seq mixed spatio-temporal encoder for 3d human pose estimation in video. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, New Orleans, LA, USA, 18 June–24 June 2022; pp. 13232–13242. [Google Scholar]

- Li, W.; Liu, M.; Liu, H.; Wang, P.; Cai, J.; Sebe, N. Hourglass tokenizer for efficient transformer-based 3D human pose estimation. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Seattle, WA, USA, 16–22 June 2024; pp. 604–613. [Google Scholar]

| Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |