Compressive-Sensing-Based Fast Acquisition Algorithm Using Gram-Matrix Optimization via Direct Projection

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Compressive Sensing Theory

2.1. Sparse Representation and Compressed Measurements

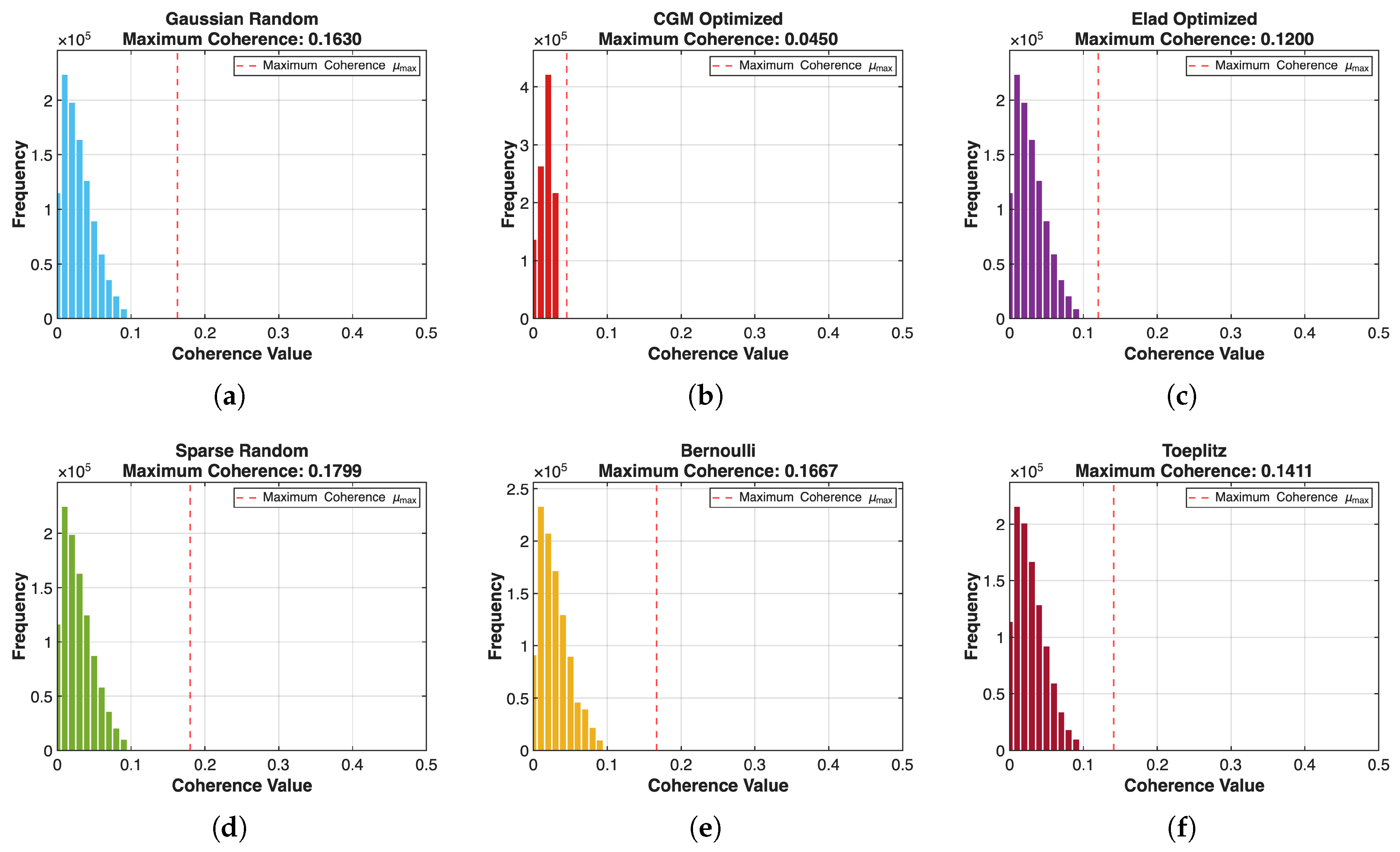

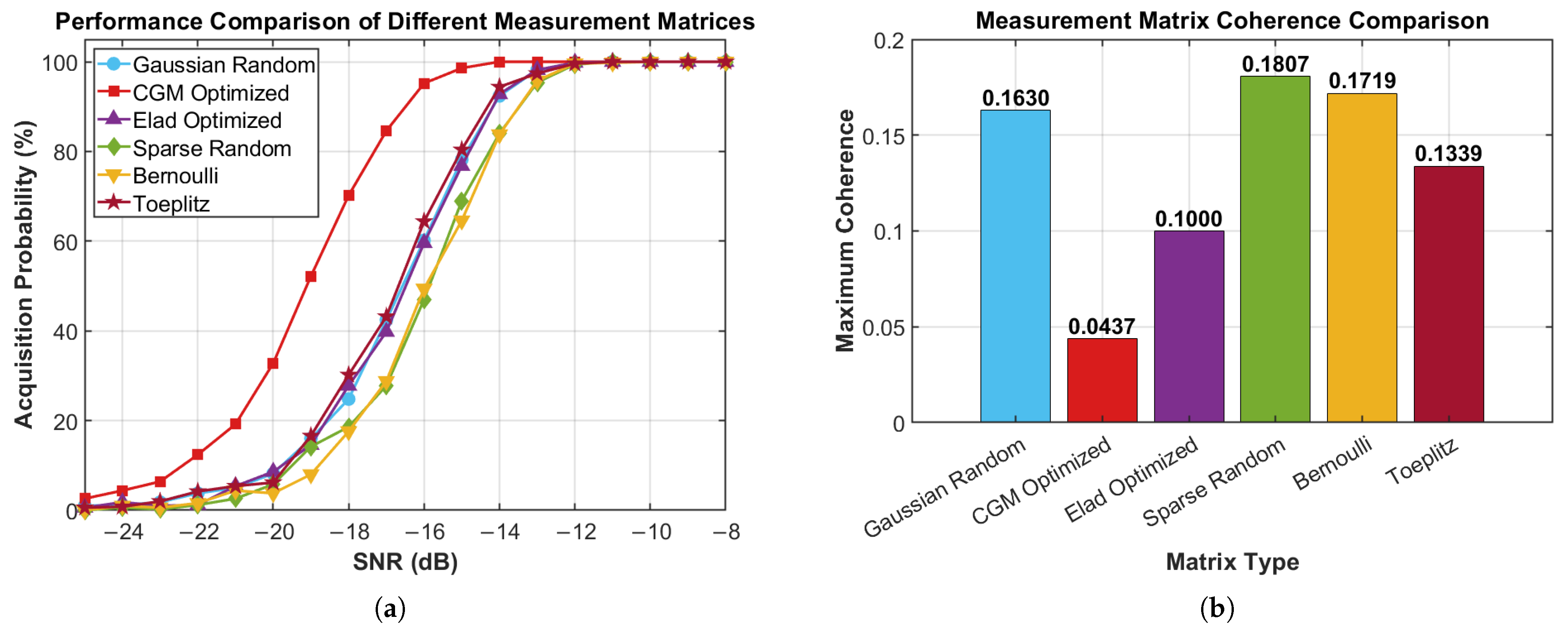

2.2. Signal Reconstruction and Optimization Problem

2.3. Direct Projection Method for GNSS Signal Acquisition

3. Compressive-Sensing-Based Fast Acquisition Algorithm Using Direct Projection

3.1. Frequency-Domain Fast Cyclic Correlation

3.2. Peak Detection and Acquisition Decision

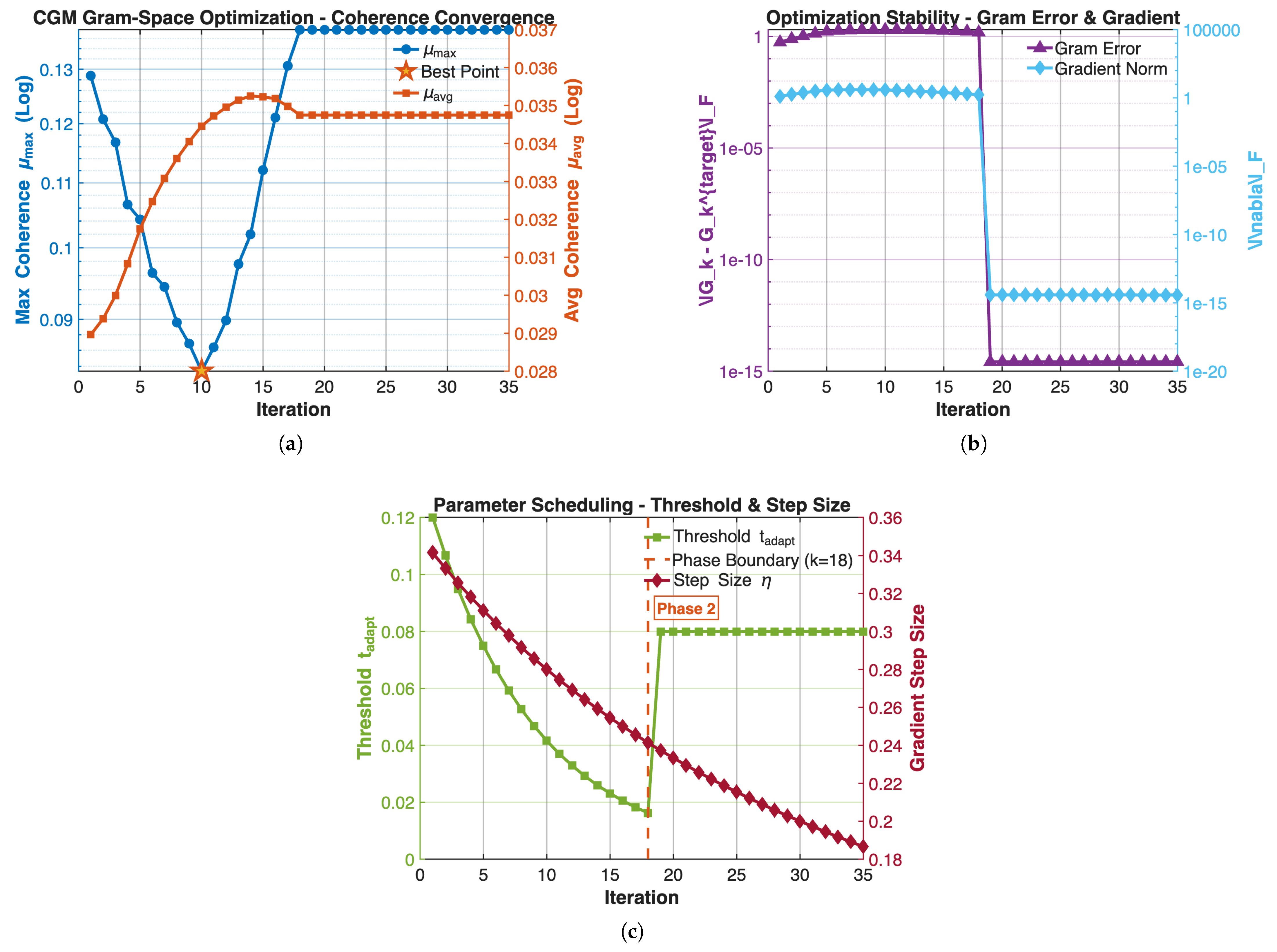

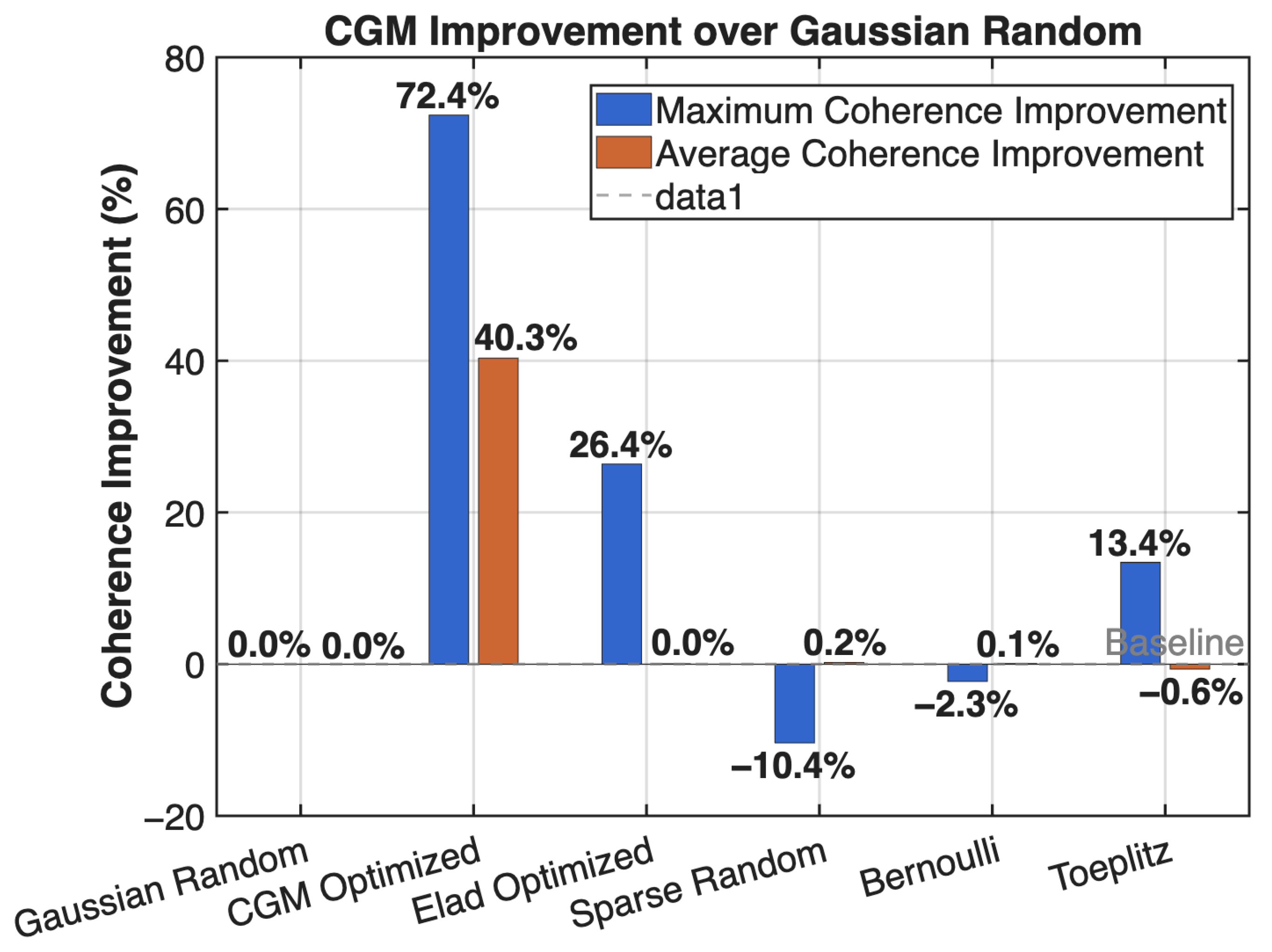

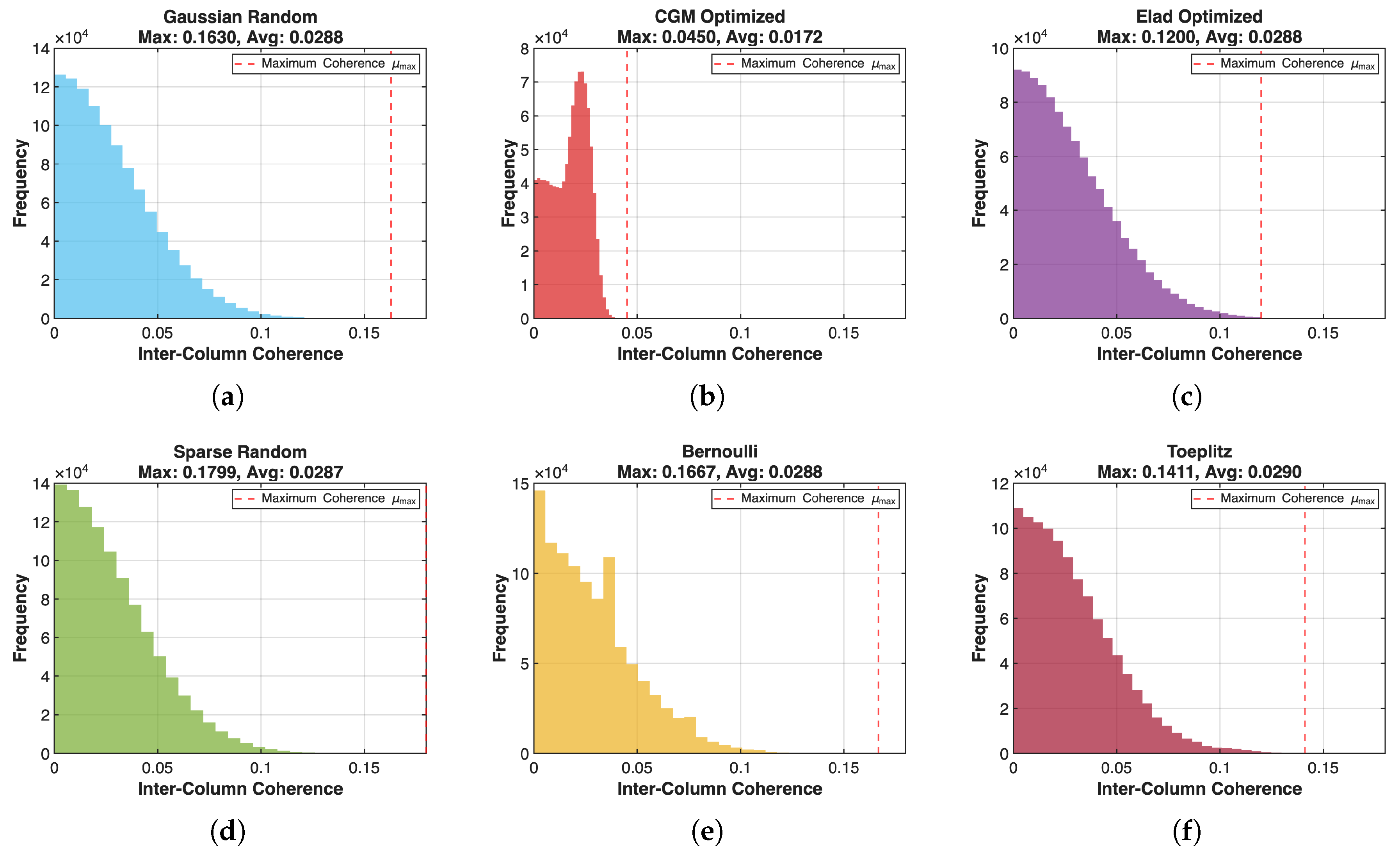

3.3. Measurement Matrix Design Based on Gram-Matrix Optimization

3.3.1. Objective Function Under a Bi-Level Optimization Framework

3.3.2. Adaptive Threshold Setting

3.3.3. Manifold Projection Based on Eigendecomposition

3.4. Design Principle of Fast Acquisition

3.5. Computational Complexity Analysis

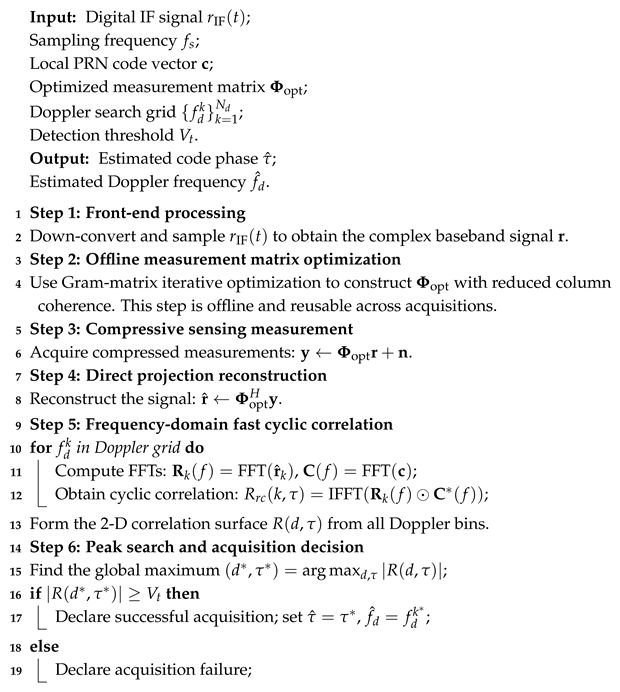

3.6. Complete Algorithm Workflow

| Algorithm 1: Compressive-Sensing-Based Fast Acquisition Algorithm Using Gram-Matrix Optimization via Direct Projection (CGM) |

|

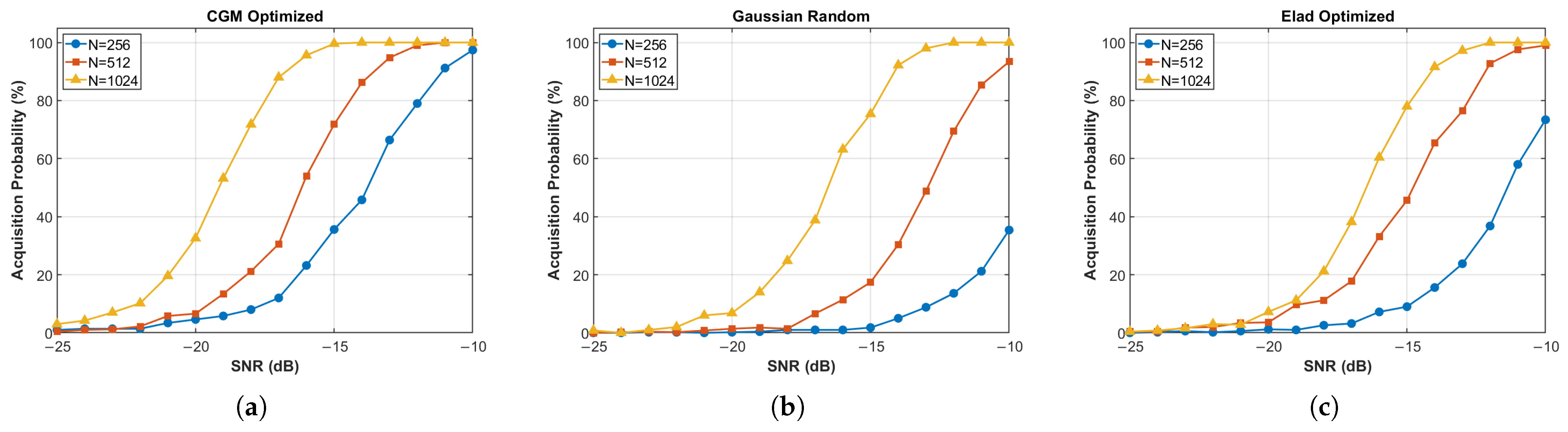

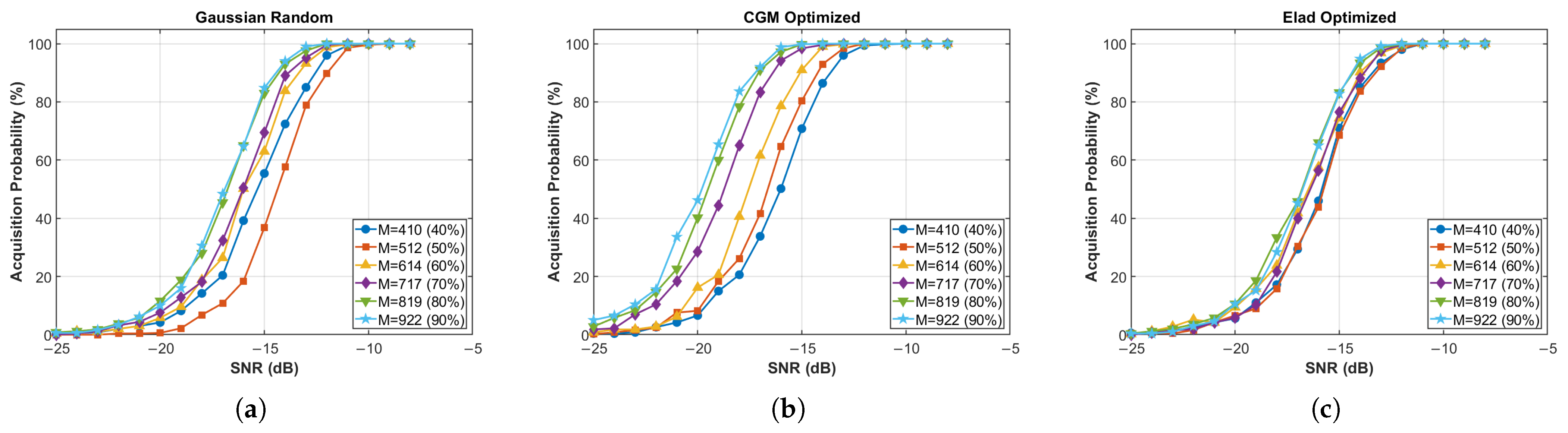

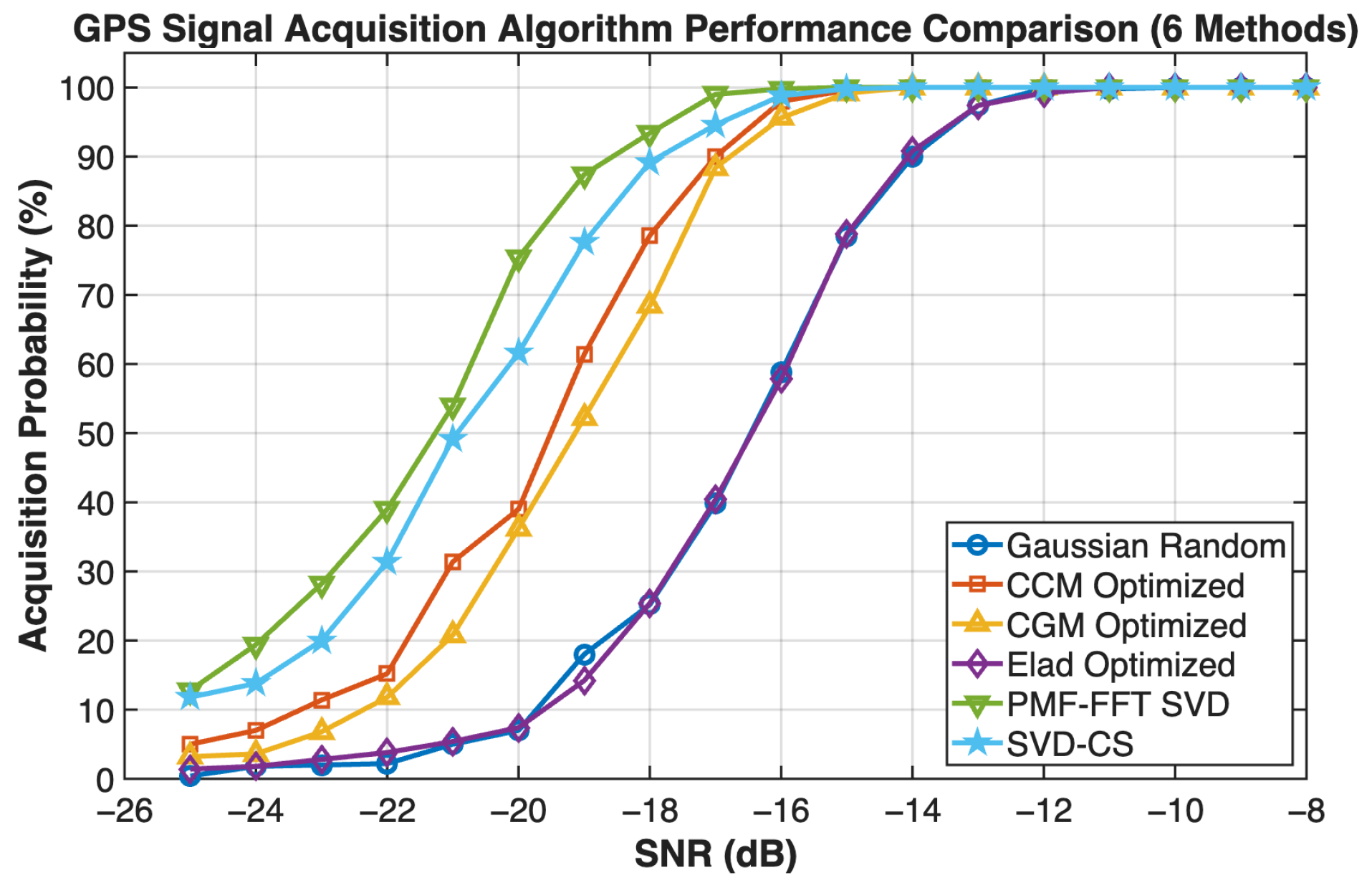

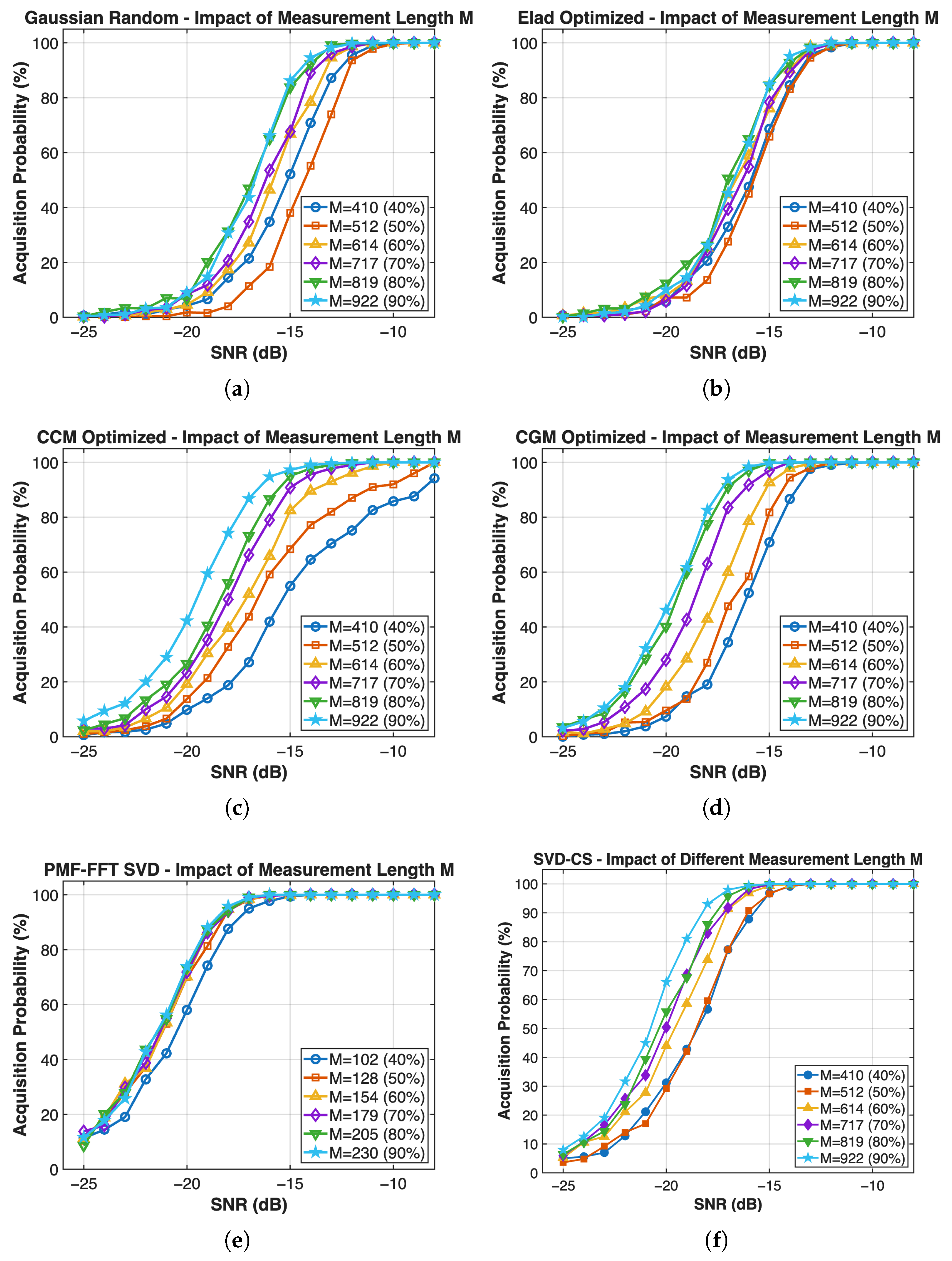

4. Algorithm Performance Analysis

4.1. Perturbation Analysis of the Direct Projection Method

4.2. Detection Probability Analysis

5. Simulation Validation

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| GNSS | Global Navigation Satellite System |

| FFT | Fast Fourier Transform |

| CGM-Optimized | Proposed CGM-based direct-projection acquisition |

| CCM-Optimized | CCM-based CS acquisition |

| ELAD-Optimized | ELAD-Optimized direct-projection acquisition |

| Gaussian-Random | Gaussian-Random direct-projection acquisition |

| PMF-FFT-SVD | CS-SVD-PMF-FFT acquisition |

| SNR | Signal-to-Noise Ratio |

| ETF | Equiangular Tight Frame |

References

- Carvalho, G.S.; Silva, F.O.; Pacheco, M.V.O.; Campos, G.A.O. Performance Analysis of Relative GPS Positioning for Low-Cost Receiver-Equipped Agricultural Rovers. Sensors 2023, 23, 8835. [Google Scholar]

- Kowalczyk, W.Z.; Hadas, T. A comparative analysis of the performance of various GNSS positioning concepts dedicated to precision agriculture. Rep. Geod. Geoinformatics 2024, 117, 11–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubo, N. Global Navigation Satellite System Precise Positioning Technology. IEICE Trans. Commun. 2024, 11, 691–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hegarty, C.J. The Global Positioning System (GPS). In Springer Handbook of Global Navigation Satellite Systems; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2017; pp. 197–218. [Google Scholar]

- Hofmann-Wellenhof, B.; Lichtenegger, H.; Wasle, E. GNSS—Global Navigation Satellite Systems: GPS, GLONASS, Galileo, and More; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, C.; Li, X.; Gao, S.; Lin, T.; Wang, L. Performance Analysis of Global Navigation Satellite System Signal Acquisition Aided by Different Grade Inertial Navigation System under Highly Dynamic Conditions. Sensors 2017, 17, 980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donoho, D.L. Compressed sensing. IEEE Trans. Inf. Theory 2006, 52, 1289–1306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ou, S.; Li, J.; Sun, J.; Zeng, D.; Li, J.; Yan, Y. A GNSS Signal Acquisition Scheme Based on Compressed Sensing. In Proceedings of the ION 2015 Pacific PNT Meeting, Honolulu, HI, USA, 20–23 April 2015; pp. 618–628. [Google Scholar]

- Elango, G.A.; Sudha, G.F. Weak GPS acquisition via compressed differential detection using structured measurement matrix. Int. J. Smart Sens. Intell. Syst. 2016, 9, 1877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albu-Rghaif, A.; Lami, I.A. Novel dictionary decomposition to acquire GPS signals using compressed sensing. In 2014 World Congress on Computer Applications and Information Systems (WCCAIS); IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2014; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, F.; Zhao, L.; Jiang, X.; Li, L.; Yu, J.; Liang, G. GNSS Signal Compression Acquisition Algorithm Based on Sensing Matrix Optimization. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 5866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, L.; Zhou, F.; Zhao, L.; Liang, G.; Yu, J. Compressed sensing GNSS signal acquisition algorithm based on singular value decomposition. J. Univ. Chin. Acad. Sci. 2023, 40, 128–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Chen, J.; Guo, Y.; Zhao, Y. GNSS Signal Acquisition Based on Compressive Sensing and Improved Measurement Matrix. In Proceedings of the 2024 6th International Conference on Electronic Engineering and Informatics (EEI), Chongqing, China, 28–30 June 2024; pp. 1762–1765. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, F.; Zhou, F.; Pan, L.; Lin, J. Parallel GPS Signal Acquisition Algorithm Based on Alternating Direction Method of Multipliers. J. Univ. Electron. Sci. Technol. China 2020, 49, 187–193. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, Z.; Deng, M.; Huang, H.; Wang, X.; Liu, Q. Non-Iterative Shrinkage-Thresholding-Reconstructed Compressive Acquisition Algorithm for High-Dynamic GNSS Signals. Aerospace 2025, 12, 958. [Google Scholar]

- Cai, Y.; Tang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Gao, H.; Sun, X.; Pan, S. Photonic compressive sensing system based on 1-bit quantization for broadband signal sampling. J. Light. Technol. 2025, 43, 9442–9449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eldar, Y.C.; Kutyniok, G. Compressed Sensing: Theory and Applications; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Tropp, J.A. A mathematical introduction to compressive sensing book review. Bull. Am. Math. Soc. 2017, 54, 151–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, H.; Li, Z.; Dou, Z. Fast Acquisition Method of GPS Signal Based on FFT Cyclic Correlation. Int. J. Commun. Netw. Syst. Sci. 2017, 10, 246–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.S. Research on fast acquisition of GPS signal using radix-2 FFT and radix-4 FFT algorithm. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE 6th International Conference on Advanced Computing (IACC), Bhimavaram, India, 27–28 February 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Nezhadshahbodaghi, M.; Mosavi, M.R.; Rahemi, N. Improved Semi-Bit Differential Acquisition Method for Navigation Bit Sign Transition and Code Doppler Compensation in Weak Signal Environment. J. Navig. 2020, 73, 892–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, F.; Yu, B.; Gan, X.; Jia, R.; Zhang, H.; Huang, L.; Wang, B. Unambiguous Acquisition/Tracking Technique Based on Sub-Correlation Functions for GNSS Sine-BOC Signals. Sensors 2020, 20, 485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nie, G.; Wang, X.; Shen, L.; Cai, Y. A fast method for the acquisition of weak long-code signal. GPS Solut. 2020, 24, 104. [Google Scholar]

- Pennec, X. Manifold-valued image processing with SPD matrices. In Riemannian Geometric Statistics in Medical Image Analysis; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2020; pp. 75–134. [Google Scholar]

- Krebs, J.; Rademacher, D.; von Sachs, R. Statistical inference for intrinsic wavelet estimators of SPD matrices in a log-Euclidean manifold. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2202.07010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, L.; Wu, X.J. Dimensionality reduction on the symmetric positive definite manifold with application to image set classification. J. Electron. Imaging 2020, 29, 043015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, A.; Weber, M. Structured Regularization for Constrained Optimization on the SPD Manifold. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2410.09660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jun, H. A New Technology For Gnss Signal Fast Acquisition Within Three Seconds, Applicable To Current Gnss Receivers. In Proceedings of the 2006 National Technical Meeting of the Institute of Navigation, Monterey, CA, USA, 18–20 January 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan, E.D.; Hegarty, C. Understanding GPS/GNSS: Principles and Applications; Artech House: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, L.; Chen, K.; Ying, R.; Liu, P.; Yu, W. Parallel Acquisition of Gnss Signal Based on Combined Code. In Proceedings of the 26th International Technical Meeting of the Satellite Division of the Institute of Navigation, Nashville, TN, USA, 16–20 September 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Wang, M.; Li, Y. Low Computational Signal Acquisition for GNSS Receivers Using a Resampling Strategy and Variable Circular Correlation Time. Sensors 2018, 18, 678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ta, T.H.; Shivaramaiah, N.C.; Dempster, A.G.; Presti, L.L. Significance of Cell-Correlation Phenomenon in GNSS Matched Filter Acquisition Engines. IEEE Trans. Aerosp. Electron. Syst. 2012, 48, 1264–1286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahouli, K.; Ripken, W.; Gugler, S.; Unke, O.T.; Müller, K.R.; Nakajima, S. Disentangling Total-Variance and Signal-to-Noise-Ratio Improves Diffusion Models. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2502.08598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Hardware | Parameters |

|---|---|

| CPU | AMD Ryzen 9 9950X CPU @ 4.3 GHz |

| RAM | KINGBANK DDR5 6400MHz 64GB |

| Hard Disk | PREDATOR SSD 4T |

| Graphics Card | NVIDIA RTX 5080 |

| Acquisition Algorithm | Complexity | CPU Time |

|---|---|---|

| CCM-based OMP CS acquisition (CCM) [11] | ||

| SVD-based OMP CS acquisition (SVD) [12] | ||

| PMF-FFT-SVD based OMP CS acquisition (PMF-FFT-SVD) [13] | ||

| CGM-based OMP CS acquisition (CGM) | ||

| The proposed acquisition (CGM-Optimized) | ||

| Gaussian-Random-based direct-projection CS acquisition (GR-Optimized) | ||

| ELAD-Optimized-based direct-projection CS acquisition (ELAD-Optimized) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Zhou, F.; Wang, W.; Xiao, Y.; Zhou, C. Compressive-Sensing-Based Fast Acquisition Algorithm Using Gram-Matrix Optimization via Direct Projection. Electronics 2026, 15, 171. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics15010171

Zhou F, Wang W, Xiao Y, Zhou C. Compressive-Sensing-Based Fast Acquisition Algorithm Using Gram-Matrix Optimization via Direct Projection. Electronics. 2026; 15(1):171. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics15010171

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhou, Fangming, Wang Wang, Yin Xiao, and Chen Zhou. 2026. "Compressive-Sensing-Based Fast Acquisition Algorithm Using Gram-Matrix Optimization via Direct Projection" Electronics 15, no. 1: 171. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics15010171

APA StyleZhou, F., Wang, W., Xiao, Y., & Zhou, C. (2026). Compressive-Sensing-Based Fast Acquisition Algorithm Using Gram-Matrix Optimization via Direct Projection. Electronics, 15(1), 171. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics15010171