A Lightweight DTDMA-Assisted MAC Scheme for Ad Hoc Cognitive Radio IIoT Networks

Abstract

1. Introduction

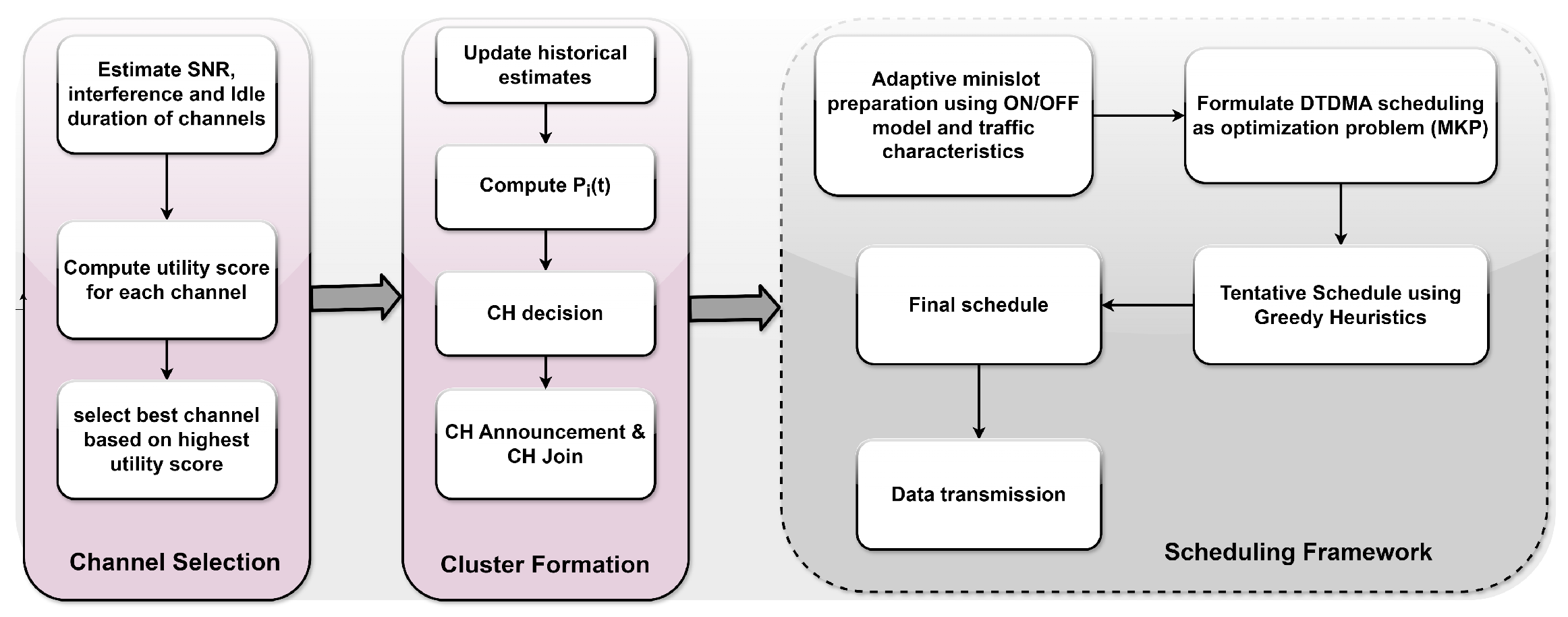

- We propose a lightweight DTDMA-assisted CR MAC (LDCRM) scheme for ad hoc CR-IIoT networks. LDCRM schedules minislots among devices by considering the spectrum availability and bandwidth requirements of IIoT applications, ensuring a low computational complexity.

- A lexicographic channel-ranking method is proposed that sorts channels based on PU interference, the expected idle duration, and the signal strength to maximize the transmission opportunities.

- We developed a random search-based adaptive minislot strategy that dynamically adjusts the minislot duration to mitigate bandwidth fragmentation.

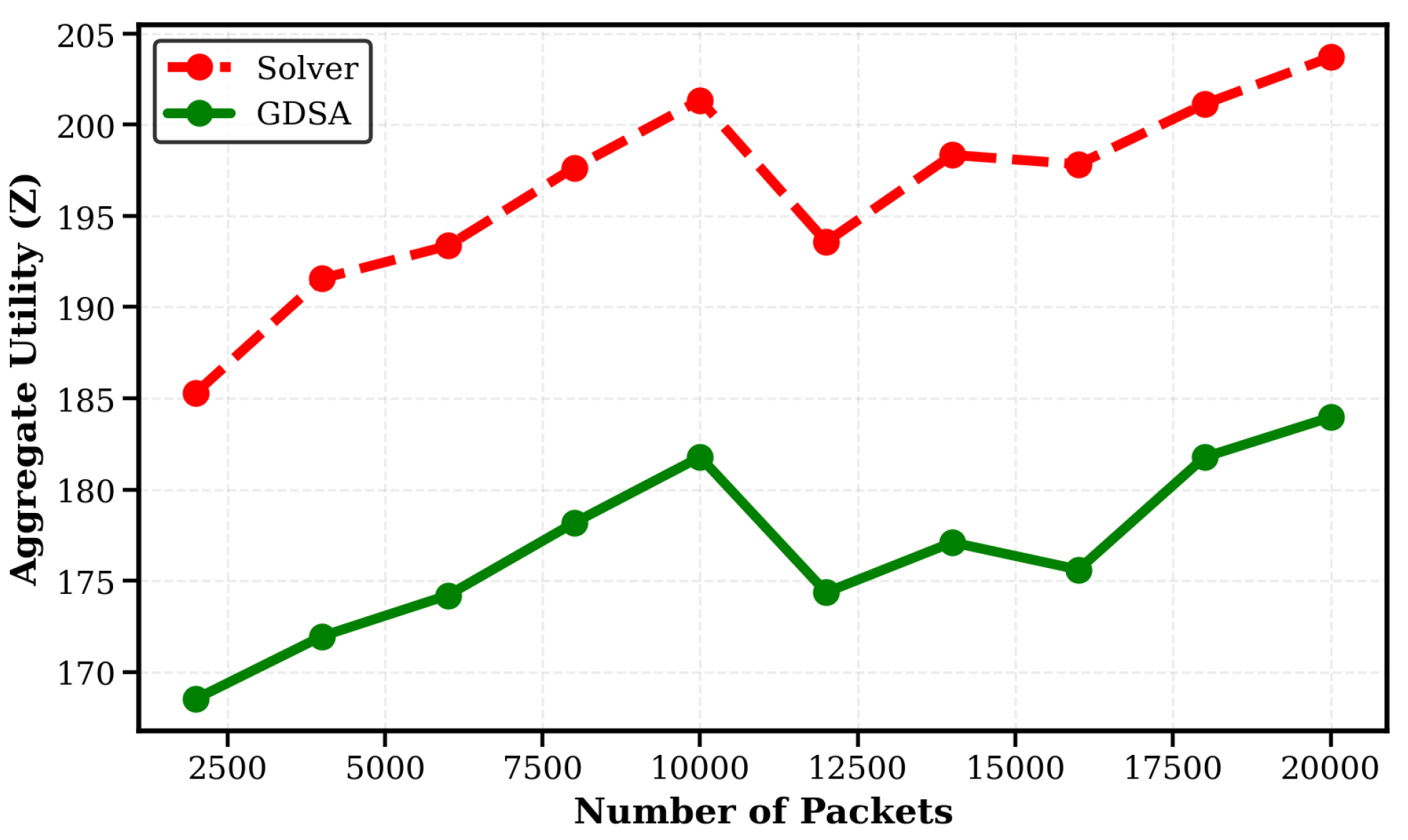

- The DTDMA scheduling was modeled using a multiple knapsack problem (MKP) framework and solved using a lightweight greedy heuristic to achieve a near-optimal performance with a reduced complexity.

2. Related Works

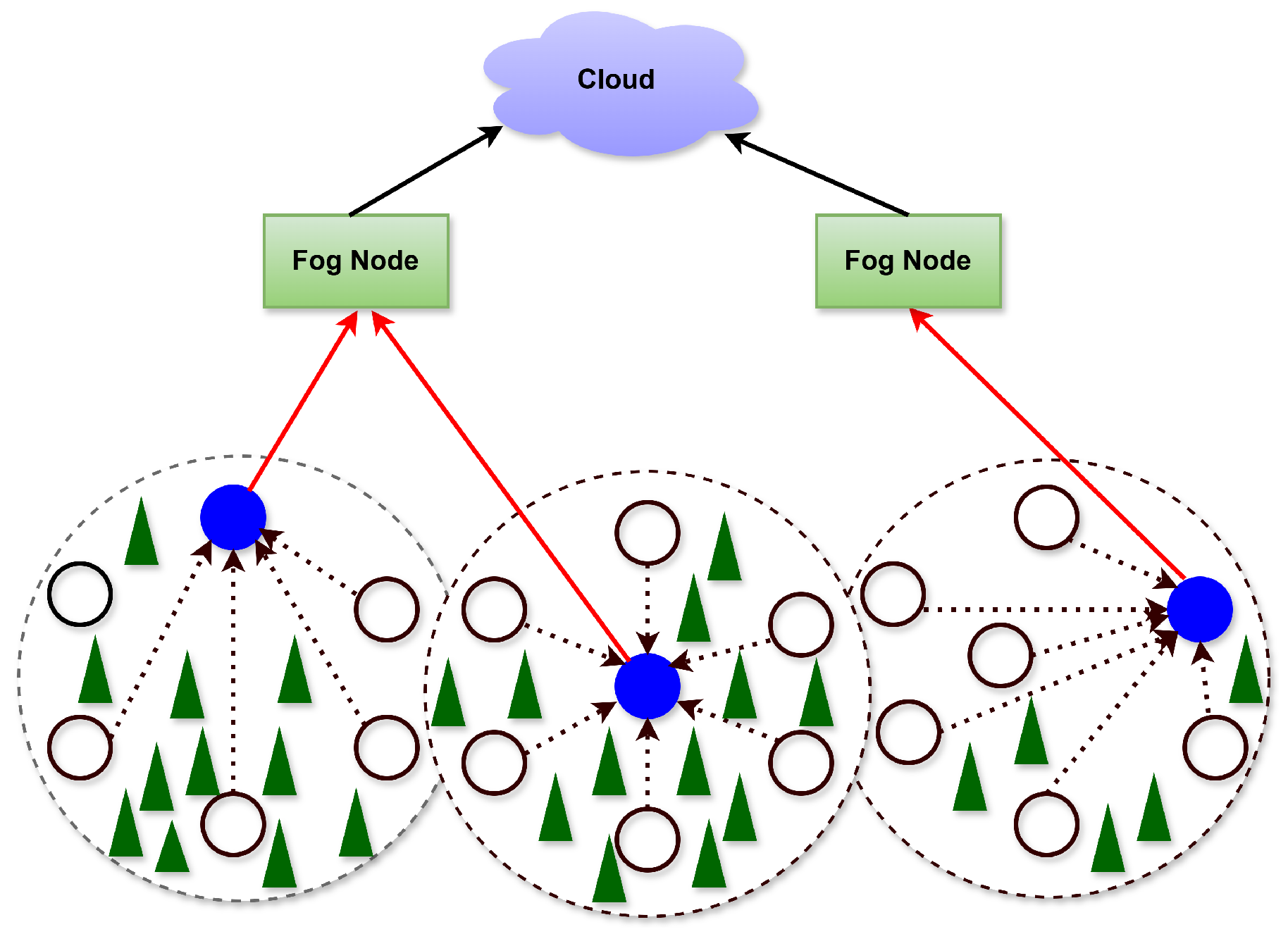

3. System Model and Assumptions

- Each CR-IIoT device is assigned a 16-bit unique identifier by the fog node upon joining the network [31].

- The CR-IIoT devices are battery-powered and operate under energy constraints.

- Each device operates with a single transceiver to maintain low interference and cost-effectiveness [29].

- The residual energy is estimated using the Coulomb counting method [32].

- The devices are capable of direct transmission to the fog layer and support power control and signal processing [33].

- To meet the PU protection requirements, a dedicated channel from the industrial, scientific, and medical (ISM) frequency band is designated as the common control channel (CCC) to exchange control messages such as CH_Announcement and Join_Request [29].

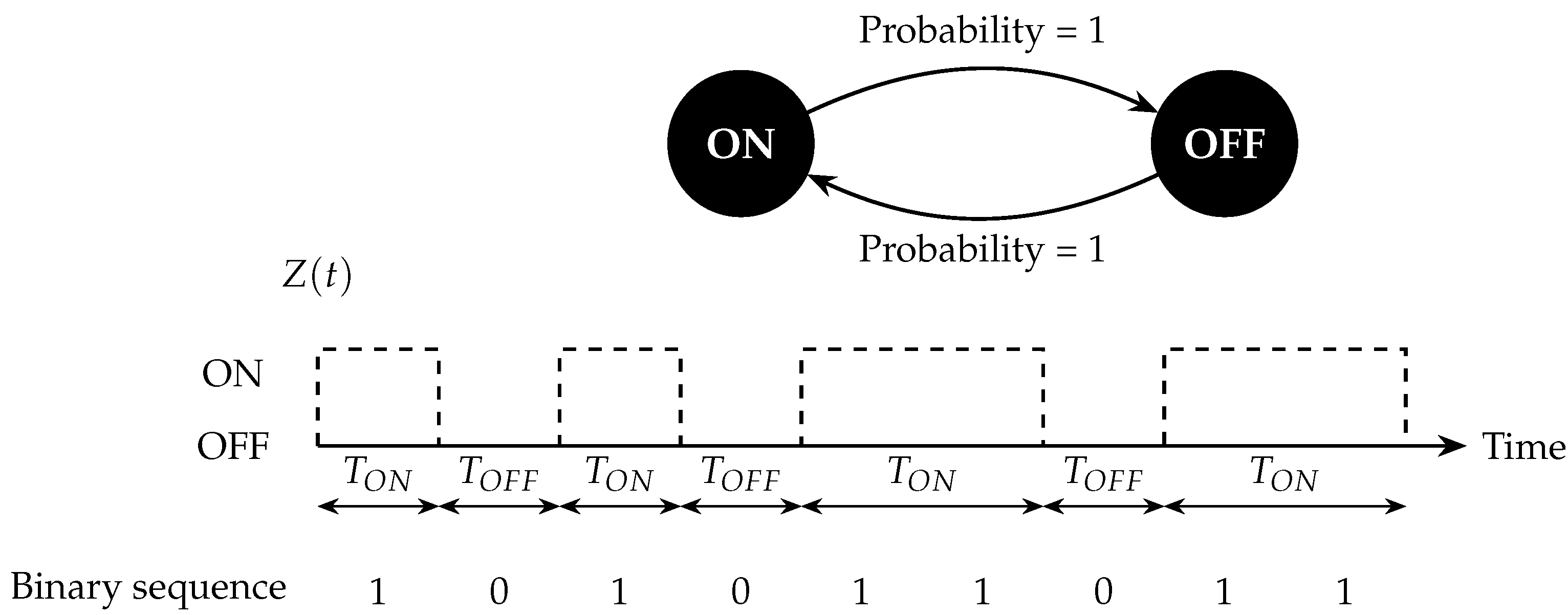

3.1. PU-Sensing Model

3.2. Dynamic Channel-Selection Policy

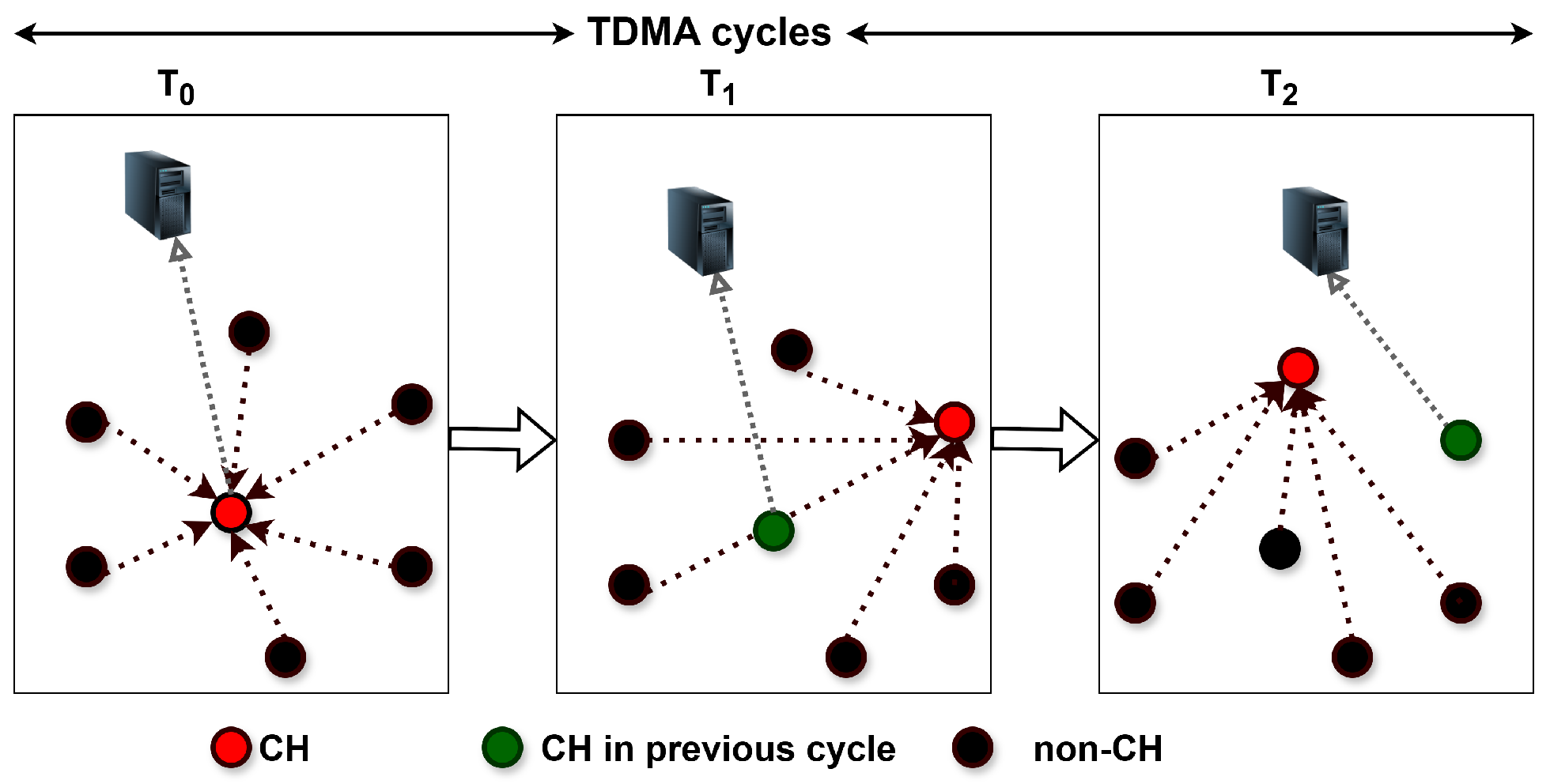

3.3. Energy- and Spectrum-Aware Distributed CH Selection

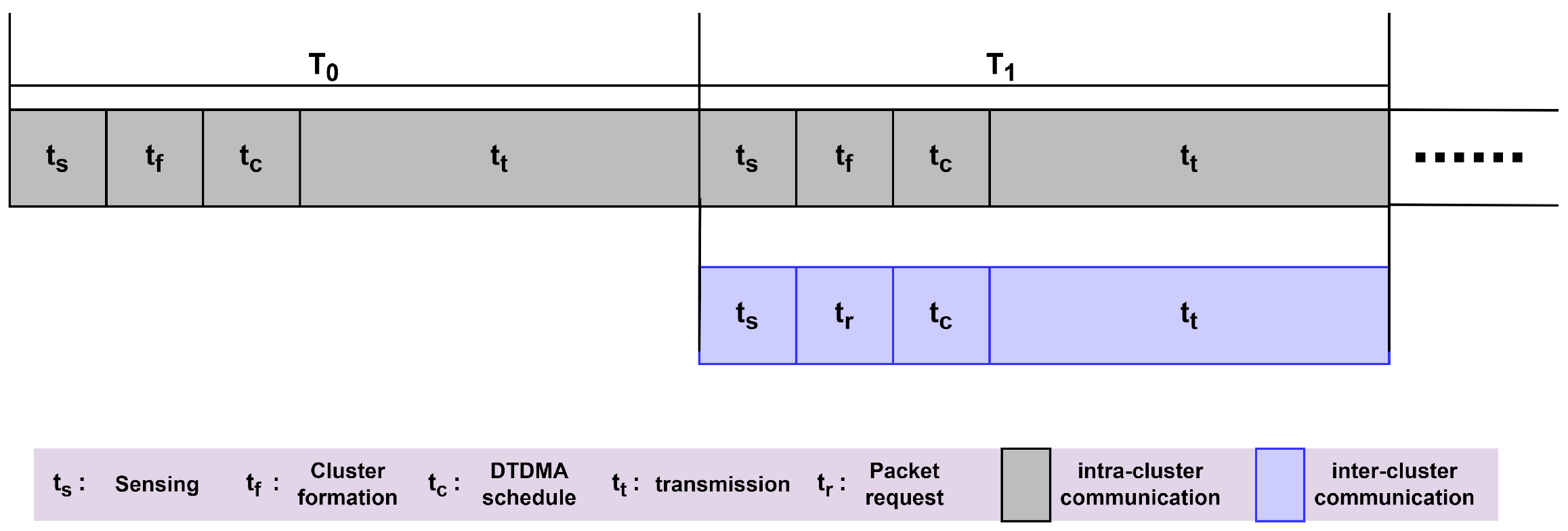

4. LDCRM Scheduling Framework

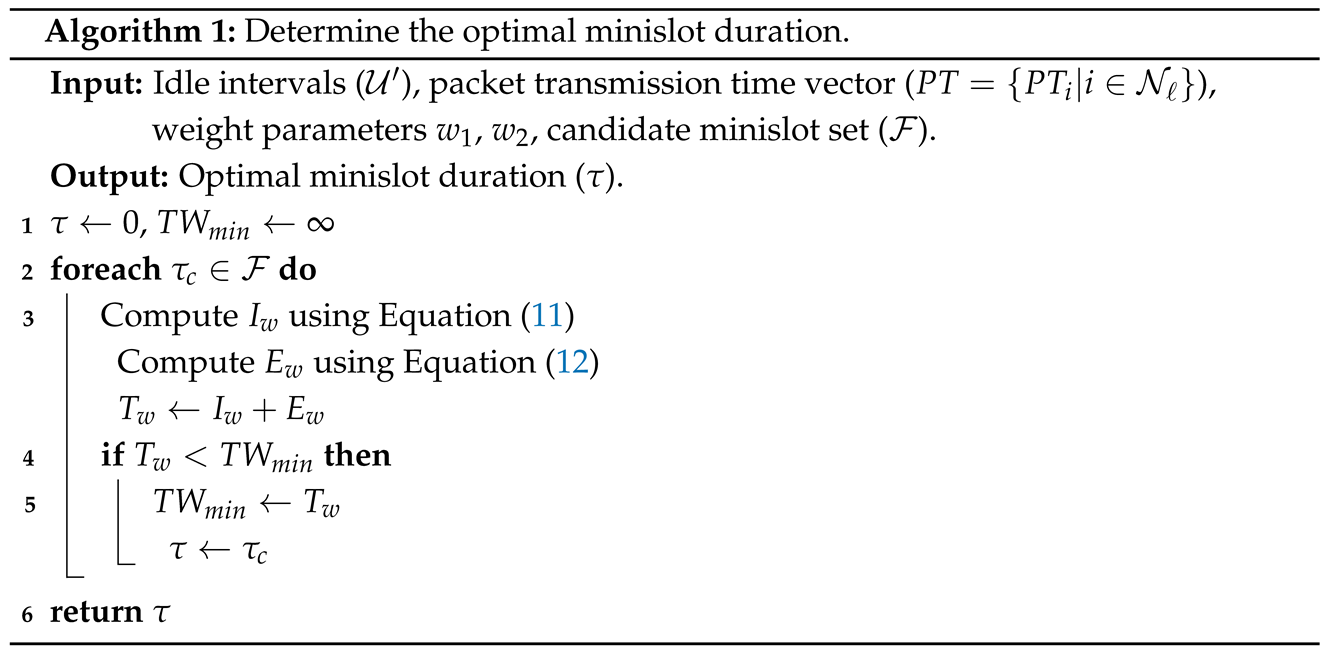

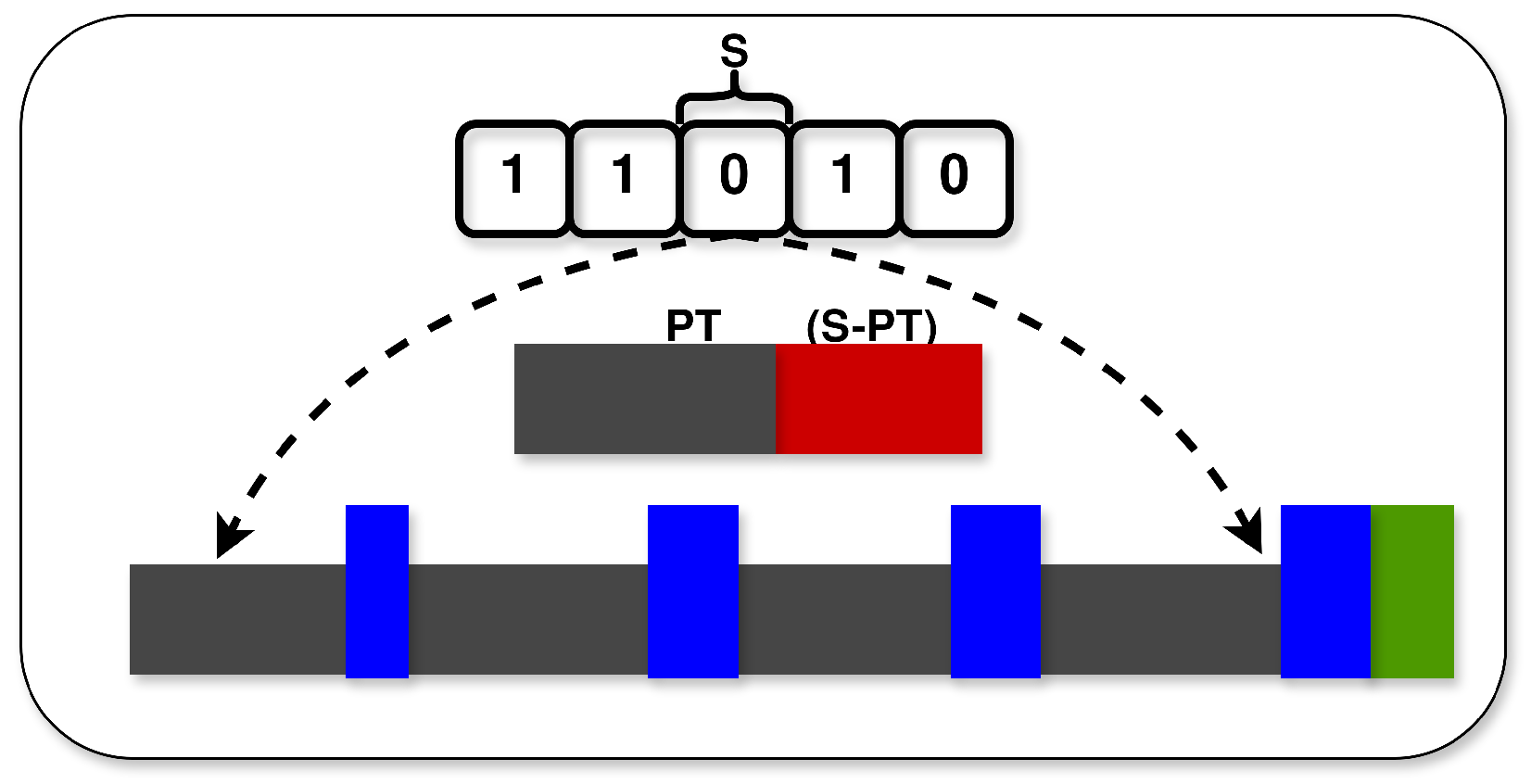

4.1. Adaptive Minislot Preparation

4.2. Problem Formulation

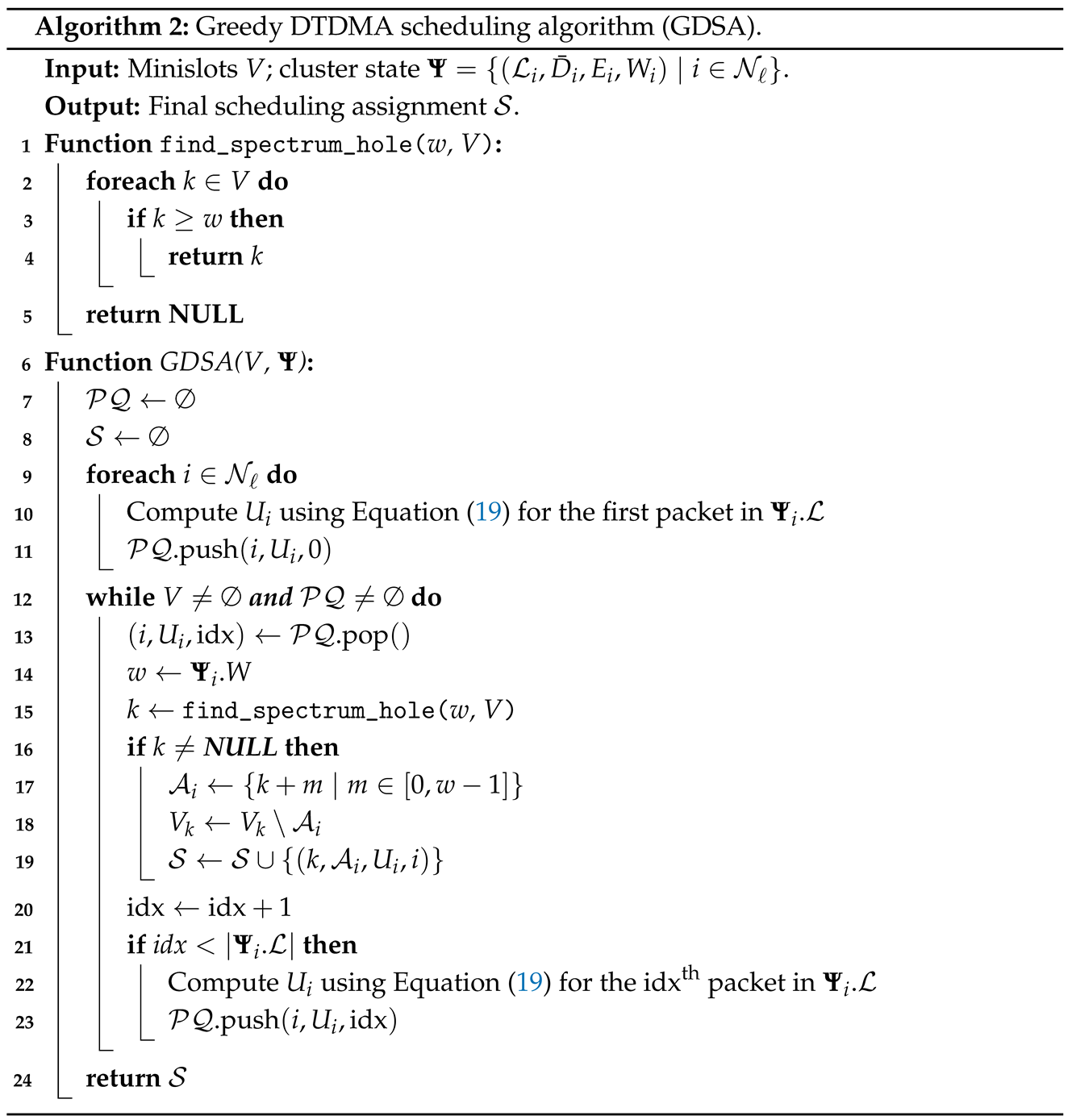

4.3. Proposed Heuristic Algorithm

4.4. Asymptotic Analysis

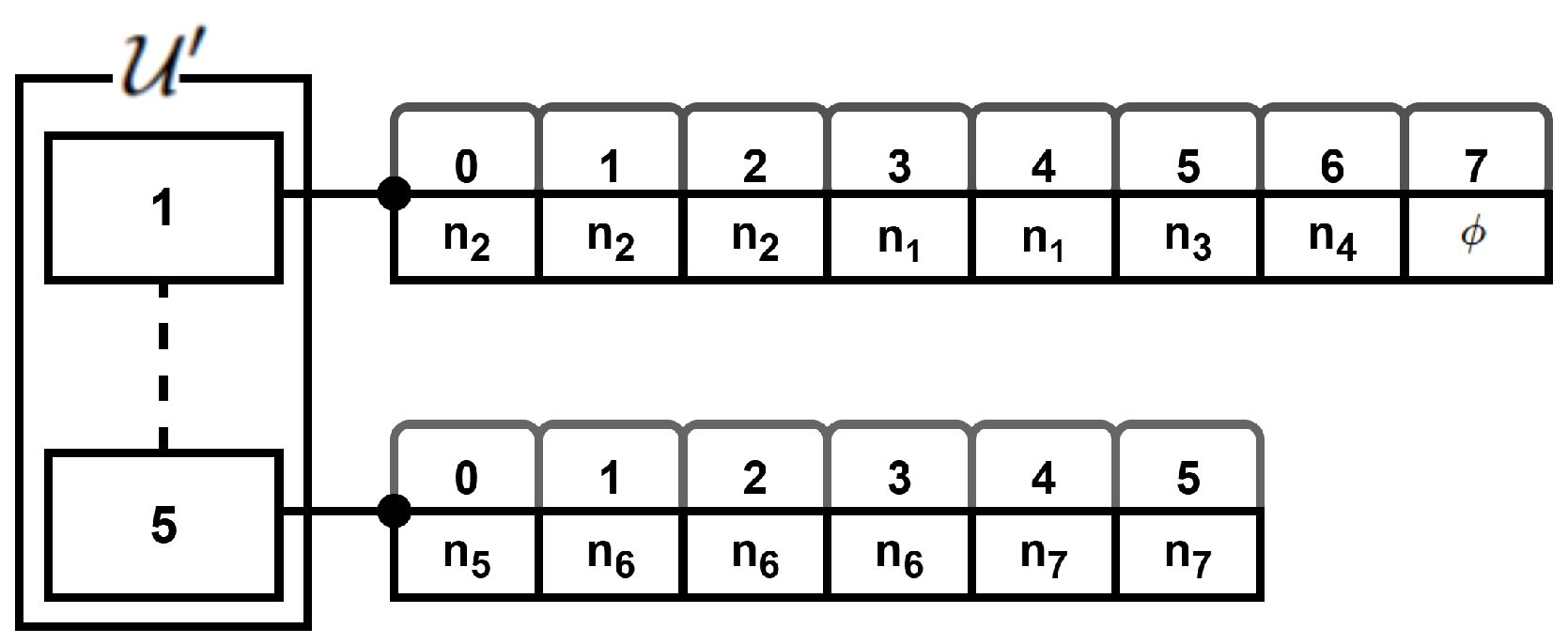

4.5. Construction of DTDMA Schedule

| Algorithm 3: DTDMA schedule-construction procedure. |

| Input: Idle periods , cluster state . Output: Final conflict-free DTDMA schedule.

|

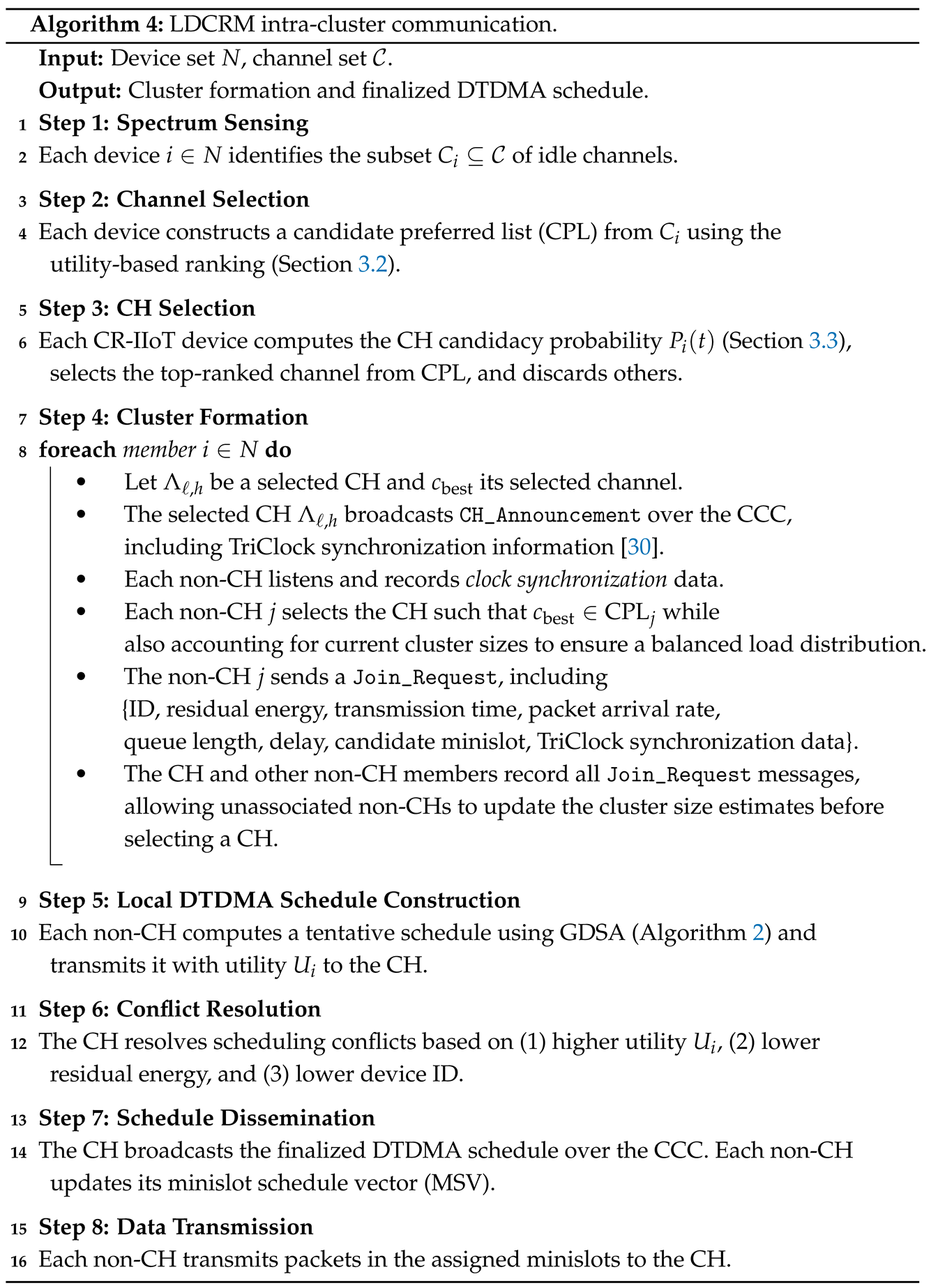

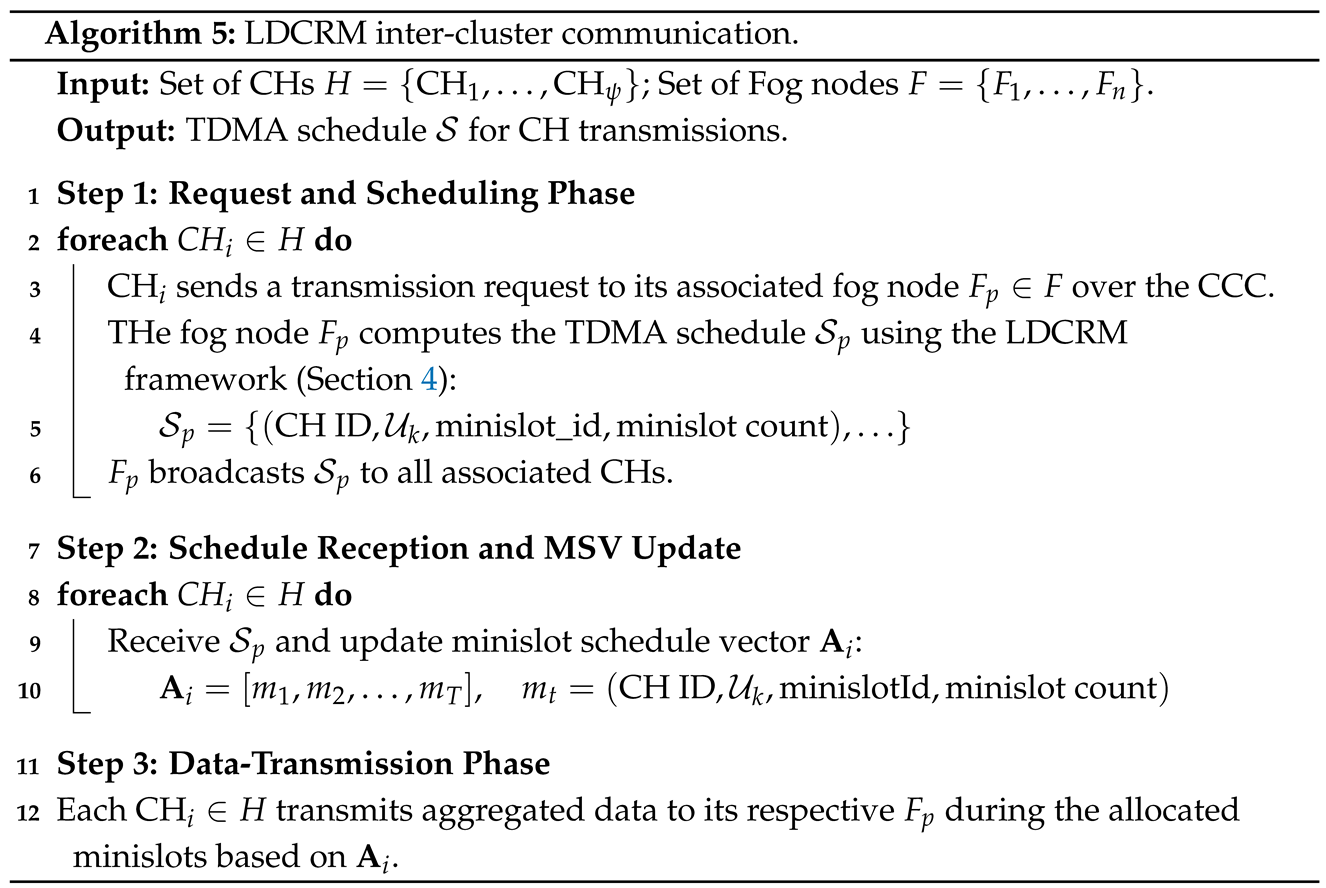

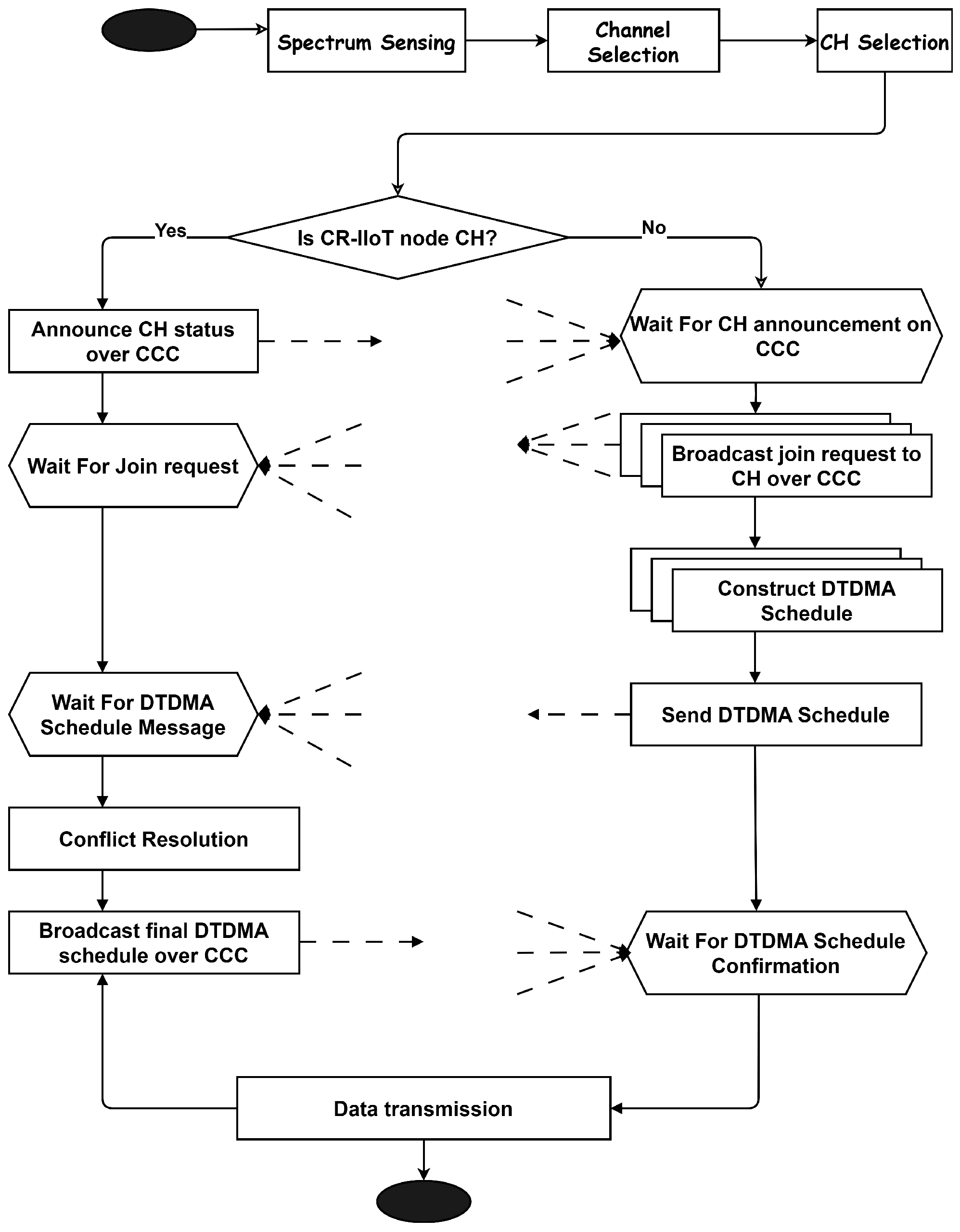

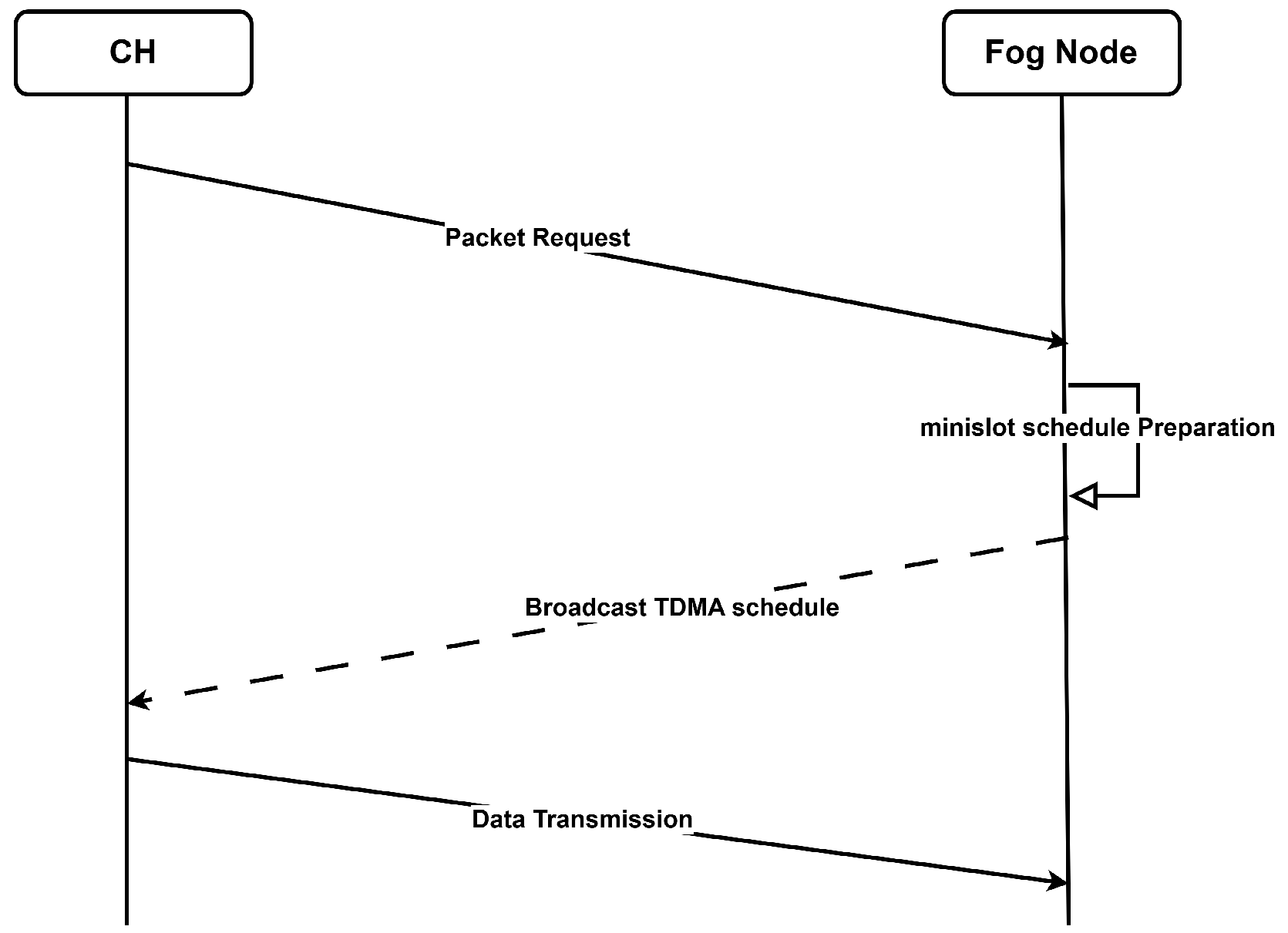

5. Proposed MAC Scheme

5.1. Intra-Cluster Communication Round

5.2. Inter-Cluster Communication Round

6. Experiments and Discussion

6.1. Performance Benchmarking

6.2. Experimental Setup

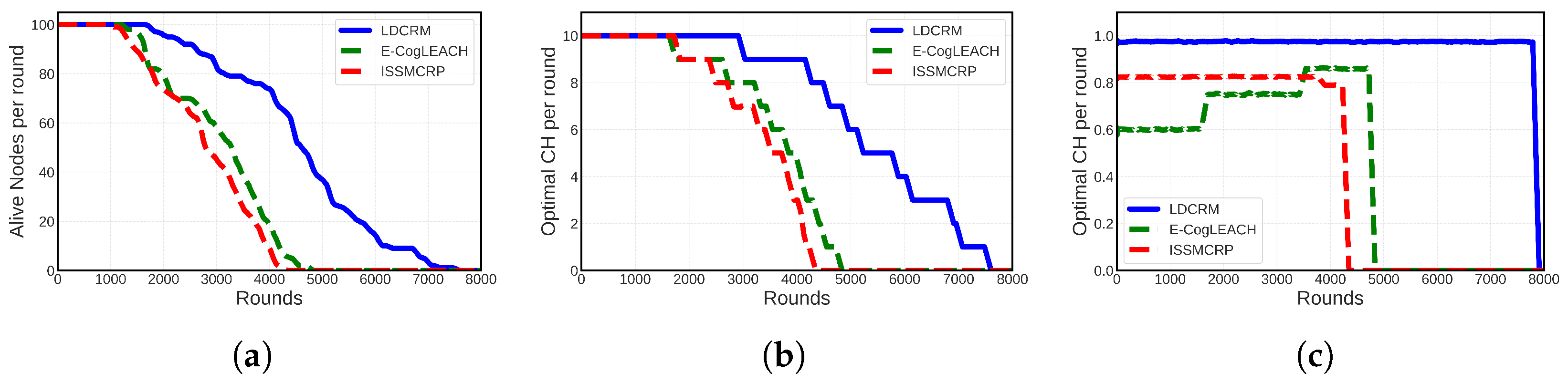

6.3. Experimental Analysis of Cluster Stability and Fairness

6.4. Experimental Result Analysis

6.4.1. Performance Evaluation Metrics

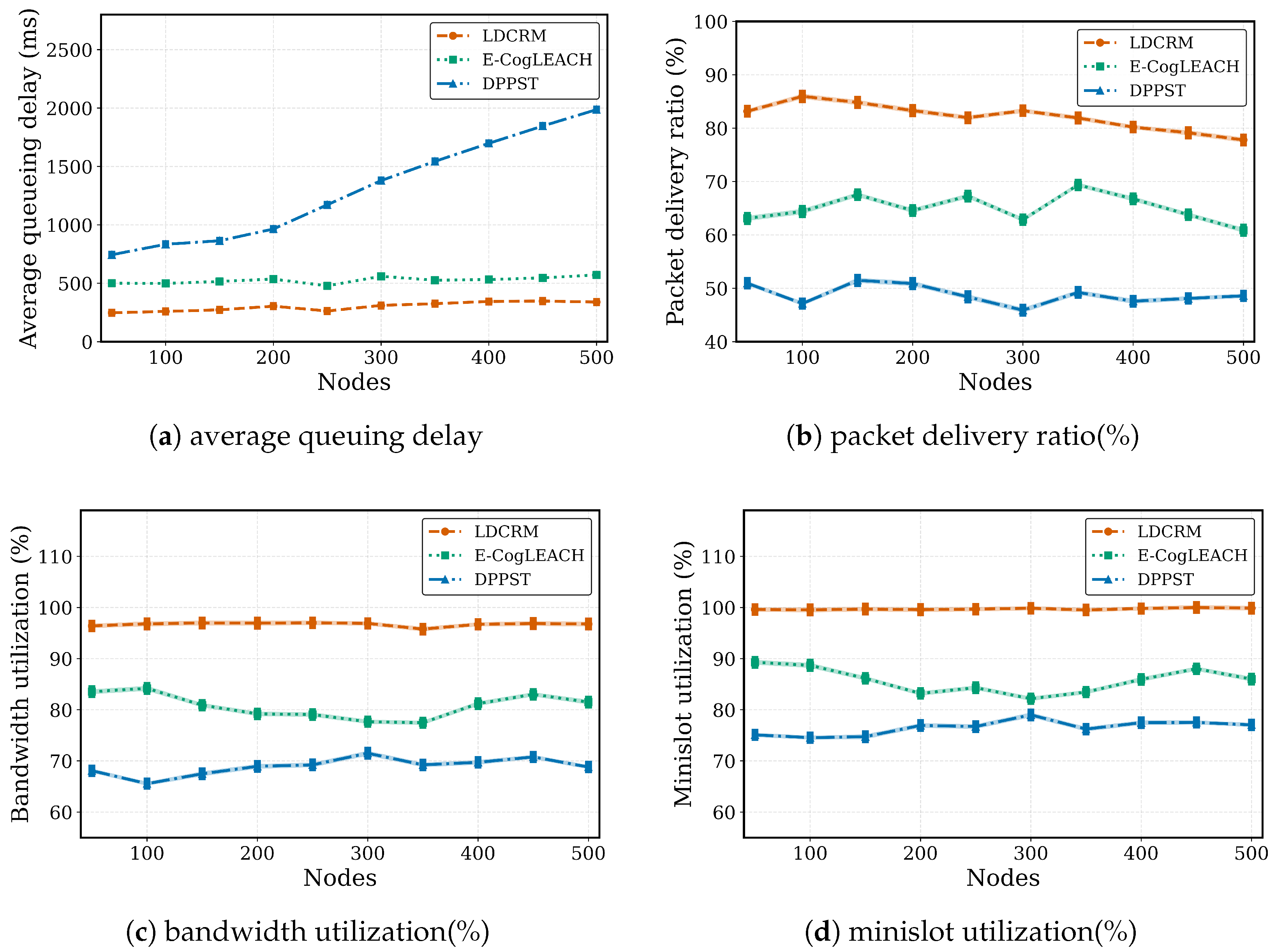

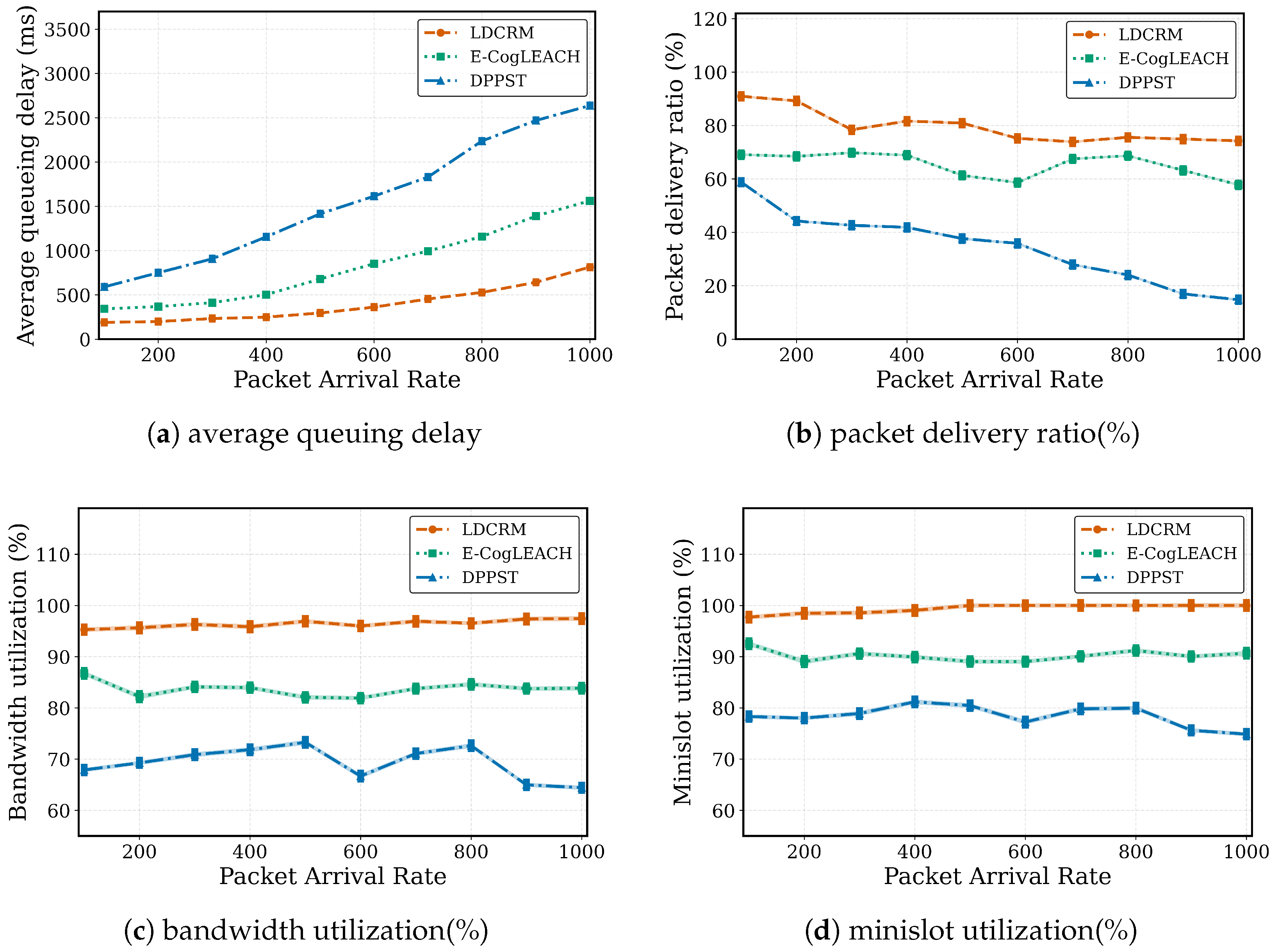

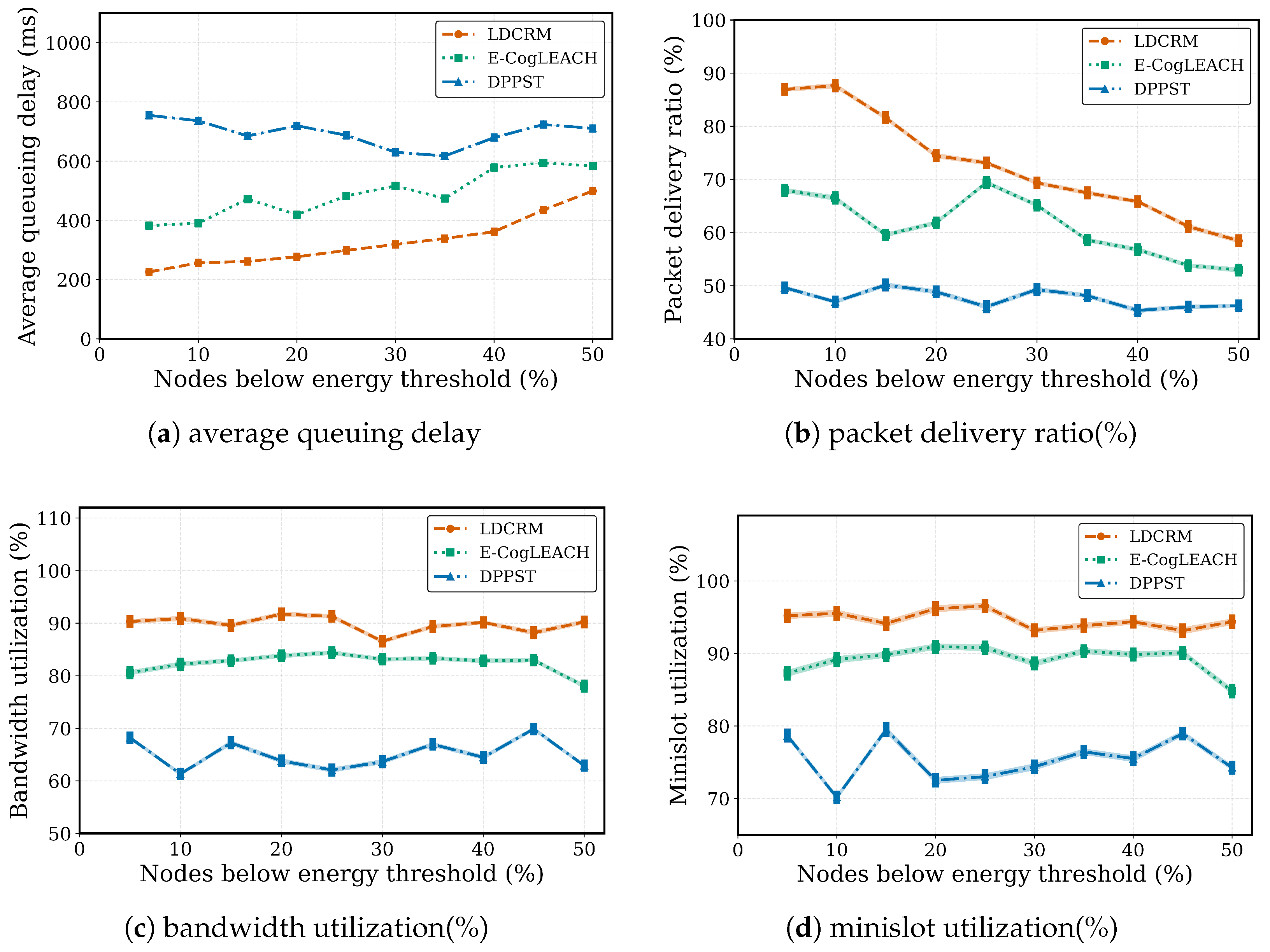

- The average queuing delay () was computed using Little’s Law [42]:where is the arrival rate of the device.

- Bandwidth utilization (, %) measures the efficiency in spectrum utilization, computed by Equation (30):

- The packet delivery ratio (, %) indicates the reliability of packet transmission, defined by Equation (31):where and are packets delivered and transmitted in cycle t.

- Slot utilization (, %) demonstrates the minislot allocation efficiency, given by Equation (32):where and denote the used and total minislots in cycle t.

6.4.2. Scalability Analysis by Increasing Network Size

6.4.3. Impact Analysis of Packet Arrival Rate on Performance

6.4.4. Impact Analysis of Residual Energy Threshold Variations on Performance

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Haykin, S. Cognitive radio: Brain-empowered wireless communications. IEEE J. Sel. Areas Commun. 2005, 23, 201–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Federal Communications Commission. Spectrum Policy Task Force Report; Report ET Docket No. 02-135; Federal Communications Commission: Washington, DC, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Mitola, J.; Maguire, G.Q. Cognitive radio: Making software radios more personal. IEEE Pers. Commun. 1999, 6, 13–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khisa, S.; Moh, S. Priority-Aware fast MAC protocol for UAV-assisted industrial IoT systems. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 57089–57106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, X.; Song, Z.; Yang, B.; ElMossallamy, M.A.; Qian, L.; Han, Z. A distributed ambient backscatter MAC protocol for Internet-of-Things networks. IEEE Internet Things J. 2019, 7, 1488–1501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batta, M.S.; Harous, S.; Louail, L.; Aliouat, Z. A distributed tdma scheduling algorithm for latency minimization in internet of things. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE International Conference on Electro Information Technology (EIT); IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2019; pp. 108–113. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Zhang, X.; Zeng, J.; Wan, Y.; Ma, F. A distributed TDMA scheduling algorithm based on energy-topology factor in Internet of Things. IEEE Access 2017, 5, 10757–10768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derakhshani, M.; Khan, Y.; Nguyen, D.T.; Parsaeefard, S.; Shoaei, A.D.; Le-Ngoc, T. Self-organizing TDMA: A distributed contention-resolution MAC protocol. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 144845–144860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, N.; Kumar, A.; Minenkov, D.; Kaplun, D.; Sharma, S. Optimized MAC Protocol Using Fuzzy-Based Framework for Cognitive Radio AdHoc Networks. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 27506–27518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salh, A.; Audah, L.; Alhartomi, M.A.; Kim, K.S.; Alsamhi, S.H.; Almalki, F.A.; Abdullah, Q.; Saif, A.; Algethami, H. Smart packet transmission scheduling in cognitive IoT systems: DDQN based approach. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 50023–50036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.M.; Kao, Y.C.; Chang, K.F.; Tsai, C.T.; Hou, C.C. A q-learning-based adaptive mac protocol for internet of things networks. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 128905–128918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benrebbouh, C.; Louail, L.; Cherbal, S. Distributed TDMA for IoT Using a Dynamic Slot Assignment. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Advances in Computing Research; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2023; pp. 469–480. [Google Scholar]

- Dhurandher, S.K.; Gupta, N.; Nicopolitidis, P. Contract theory based medium access contention resolution in TDMA cognitive radio networks. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2019, 68, 8026–8035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batta, M.S.; Aliouat, Z.; Harous, S. A distributed weight-based tdma scheduling algorithm for latency improvement in iot. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE 10th Annual Ubiquitous Computing, Electronics & Mobile Communication Conference (UEMCON); IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2019; pp. 768–774. [Google Scholar]

- Touati, H.; Chriki, A.; Snoussi, H.; Kamoun, F. Cognitive Radio and Dynamic TDMA for efficient UAVs swarm communications. Comput. Netw. 2021, 196, 108264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiwari, J.; Prakash, A.; Tripathi, R. A novel cooperative MAC protocol for safety applications in cognitive radio enabled vehicular ad-hoc networks. Veh. Commun. 2021, 29, 100336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, R.P.; Sangwan, A.; Godara, K. Modified-PRMA MAC protocol for cognitive radio networks. Wirel. Pers. Commun. 2019, 107, 869–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.T.; Kim, T.; Kim, T. A distributed TDMA scheduling algorithm using topological ordering for wireless sensor networks. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 145316–145331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eletreby, R.M.; Elsayed, H.M.; Khairy, M.M. CogLEACH: A spectrum aware clustering protocol for cognitive radio sensor networks. In Proceedings of the 2014 9th International Conference on Cognitive Radio Oriented Wireless Networks and Communications (CROWNCOM); IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2014; pp. 179–184. [Google Scholar]

- Tarek, D.; Benslimane, A.; Darwish, M.; Kotb, A.M. Distributed Packets Scheduling Technique for Cognitive Radio Internet of Things Based on Discrete Permutation Particle Swarm Optimization. In Proceedings of the 2020 International Conferences on Internet of Things (iThings) and IEEE Green Computing and Communications (GreenCom) and IEEE Cyber, Physical and Social Computing (CPSCom) and IEEE Smart Data (SmartData) and IEEE Congress on Cybermatics (Cybermatics); IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2020; pp. 142–151. [Google Scholar]

- Sarvghadi, M.A.; Wan, T.C. Distributed and Efficient Slot Assignment–Alignment Protocol for Resource-Constrained Wireless IoT Devices. IEEE Internet Things J. 2022, 10, 8754–8772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agrawal, N.K.; Kumar, S.; Bisht, G.S.; Srivastav, A.; Bansla, V.; Jain, A. RECRIoT-MAC: A Reliable and Energy Efficient Resource Management for Internet of Things Based Cognitive Radio Multi-Channel MAC Protocol. In Proceedings of the 2024 International Conference on Communication, Computer Sciences and Engineering (IC3SE); IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2024; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Oñate, W.; Sanz, R. Analysis of architectures implemented for IIoT. Heliyon 2023, 9, e12868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sengupta, J.; Ruj, S.; Bit, S.D. A secure fog-based architecture for industrial Internet of Things and industry 4.0. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inform. 2020, 17, 2316–2324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akyildiz, I.F.; Lee, W.Y.; Chowdhury, K.R. CRAHNs: Cognitive radio ad hoc networks. Ad Hoc Netw. 2009, 7, 810–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cordeiro, C.; Challapali, K. C-MAC: A cognitive MAC protocol for multi-channel wireless networks. In Proceedings of the 2007 2nd IEEE International Symposium on New Frontiers in Dynamic Spectrum Access Networks; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2007; pp. 147–157. [Google Scholar]

- Yucek, T.; Arslan, H. A survey of spectrum sensing algorithms for cognitive radio applications. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tutor. 2009, 11, 116–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akyildiz, I.F.; Lo, B.F.; Balakrishnan, R. Cooperative spectrum sensing in cognitive radio networks: A survey. Phys. Commun. 2011, 4, 40–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yarnagula, H.K.; Deka, S.K.; Sarma, N. Distributed TDMA based MAC protocol for data dissemination in ad-hoc Cognitive Radio networks. In Proceedings of the 2013 IEEE International Conference on Advanced Networks and Telecommunications Systems (ANTS); IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2013; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Leugner, S.; Constapel, M.; Hellbrueck, H. Triclock-clock synchronization compensating drift, offset and propagation delay. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE International Conference on Communications (ICC); IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2018; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- IEEE Std 802.15.4-2020; IEEE Standard for Low-Rate Wireless Networks. IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2020. Available online: https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/document/9144691 (accessed on 22 December 2025).

- Mohammadi, F. Lithium-ion battery State-of-Charge estimation based on an improved Coulomb-Counting algorithm and uncertainty evaluation. J. Energy Storage 2022, 48, 104061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heinzelman, W.B.; Chandrakasan, A.P.; Balakrishnan, H. An application-specific protocol architecture for wireless microsensor networks. IEEE Trans. Wirel. Commun. 2002, 1, 660–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehmani, M.H.; Viana, A.C.; Khalife, H.; Fdida, S. Surf: A distributed channel selection strategy for data dissemination in multi-hop cognitive radio networks. Comput. Commun. 2013, 36, 1172–1185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehmani, M.H.; Viana, A.C.; Khalife, H.; Fdida, S. Activity pattern impact of primary radio nodes on channel selection strategies. In Proceedings of the 4th International Conference on Cognitive Radio and Advanced Spectrum Management, Tenerife, Spain, 26–29 October 2011; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, H.; Shin, K.G. Efficient discovery of spectrum opportunities with MAC-layer sensing in cognitive radio networks. IEEE Trans. Mob. Comput. 2008, 7, 533–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quan, Z.; Cui, S.; Poor, H.V.; Sayed, A.H. Collaborative wideband sensing for cognitive radios. IEEE Signal Process. Mag. 2008, 25, 60–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, A.S.; Deka, S.K.; Chauhan, P.; Karmakar, A. Throughput optimization for interference aware underlay CRN. Wirel. Pers. Commun. 2019, 107, 325–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldsmith, A. Wireless Communications; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Robbins, H.; Monro, S. A stochastic approximation method. Ann. Math. Stat. 1951, 22, 400–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurose, J.F. Computer Networking: A Top-Down Approach Featuring the Internet, 3/E; Pearson Education India: New Delhi, India, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Little, J.D.; Graves, S.C. Little’s law. In Building Intuition: Insights from Basic Operations Management Models and Principles; Pearson Education India: New Delhi, India, 2008; pp. 81–100. [Google Scholar]

- LoRa Alliance. LoRaWAN® L2 1.0.4 Specification; Defines LoRaWAN Layer 2 protocol including MAC frame formats and payload size constraints; Technical Report; LoRa Alliance: Fremont, CA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- LoRa Alliance. LoRaWAN® Regional Parameters RP002-1.0.4; Specifies maximum payload sizes per region and data rate for LoRaWAN; Technical Report; LoRa Alliance: Fremont, CA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.; Liu, C. An imperfect spectrum sensing-based multi-hop clustering routing protocol for cognitive radio sensor networks. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 4853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Texas Instruments. CC2420 2.4 GHz IEEE 802.15.4/ZigBee-Ready RF Transceiver Technical Reference Manual. 2020. Available online: https://www.ti.com/lit/ds/symlink/cc2420.pdf (accessed on 22 December 2025).

- Smaragdakis, G.; Matta, I.; Bestavros, A. SEP: A Stable Election Protocol for Clustered Heterogeneous Wireless Sensor Networks; Technical Report; Boston University Computer Science Department: Boston, CA, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Jain, R.K.; Chiu, D.M.W.; Hawe, W.R. A Quantitative Measure of Fairness and Discrimination; Eastern Research Laboratory, Digital Equipment Corporation: Hudson, MA, USA, 1984; Volume 21, pp. 2022–2023. [Google Scholar]

| Parameter | Used Value (s) |

|---|---|

| Number of slots | 100 |

| Number of CR-IIoT devices | [50–500] |

| Packet arrival rate (ms) | [10–100] |

| [0.1–2.5] | |

| [0.1–2.1] | |

| Residual energy threshold | 0.05 |

| Weights | [0.01–1] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Mazumdar, B.; Deka, S.K. A Lightweight DTDMA-Assisted MAC Scheme for Ad Hoc Cognitive Radio IIoT Networks. Electronics 2026, 15, 170. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics15010170

Mazumdar B, Deka SK. A Lightweight DTDMA-Assisted MAC Scheme for Ad Hoc Cognitive Radio IIoT Networks. Electronics. 2026; 15(1):170. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics15010170

Chicago/Turabian StyleMazumdar, Bikash, and Sanjib Kumar Deka. 2026. "A Lightweight DTDMA-Assisted MAC Scheme for Ad Hoc Cognitive Radio IIoT Networks" Electronics 15, no. 1: 170. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics15010170

APA StyleMazumdar, B., & Deka, S. K. (2026). A Lightweight DTDMA-Assisted MAC Scheme for Ad Hoc Cognitive Radio IIoT Networks. Electronics, 15(1), 170. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics15010170