1. Introduction

The rapid evolution of neural speech synthesis has transformed the way humans interact with machines, access information, and create digital media. Once limited to robotic or monotonous voices, modern Text-to-Speech (TTS) systems can now generate speech that is nearly indistinguishable from human recordings in both quality and expressiveness [

1]. This technological progress has enabled a wide range of beneficial applications, ranging from personalized accessibility tools and voice assistants to language learning and content generation. At the same time, however, it has introduced new and pressing challenges, such as the emergence of

speech deepfakes [

2,

3]. Speech deepfakes are synthetic audio samples generated to mimic real voices, with the malicious intent of misleading or deceiving human listeners or automated verification systems.

The proliferation of speech deepfakes poses an escalating threat to both digital communication and information security [

4]. Sophisticated TTS systems, many of them nowadays freely available or open-sourced, allow malicious actors to reproduce a person’s voice from a few excerpts of audio and synthesize speech that conveys arbitrary content with remarkable realism. This capability has already been exploited in documented cases of financial fraud, misinformation campaigns, and impersonation attacks targeting biometric verification systems [

5]. Consequently, the task of speech deepfake detection, i.e., determining whether a given audio recording is real or synthetic, has become a critical area of research at the intersection of signal processing, machine learning, and cybersecurity.

Despite growing attention to this issue, progress in speech deepfake detection remains constrained by the lack of standardized and well-controlled datasets. Existing corpora used for detection research include synthetic speech generated from multiple speakers and diverse recording conditions [

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16]. While such datasets are valuable for evaluating system robustness, they often conflate multiple sources of variability, such as speaker identity, linguistic content, and recording quality, making it difficult to isolate the intrinsic characteristics that differentiate real and synthetic speech from a forensic viewpoint. Furthermore, most available datasets contain unpaired examples, meaning that real and synthetic utterances do not correspond to the same textual or linguistic material. This lack of alignment further limits the ability to conduct fine-grained analyses of how specific synthesis methods modify pitch, prosody, spectral content, and other acoustic cues that detectors might exploit.

To address these limitations, we introduce LJ-TTS, a large-scale, single-speaker dataset explicitly designed for controlled studies of speech deepfake detection and analysis. Unlike current state-of-the-art datasets, LJ-TTS maintains a strict one-to-one correspondence between real and synthetic utterances. Each audio clip in the dataset exists in 12 aligned versions: 1 real recording from a single speaker and 11 synthetic counterparts generated by different state-of-the-art TTS systems. This design ensures that all factors other than the synthesis model (such as linguistic content, speaking style, and recording setup) are held constant. While this narrow domain may under-represent phenomena such as spontaneous pauses, or emotional speech, this choice is deliberate: LJ-TTS is intended to enable fine-grained forensic analysis by isolating synthesis-specific effects beyond speaker variability. As a result, LJ-TTS enables researchers to directly compare whether and how different generative models introduce detectable generation artifacts, as well as to systematically evaluate how deepfake detection algorithms generalize across diverse synthesis methods when speaker and content cues are restricted. Therefore, LJ-TTS is primarily intended as a complement to existing multi-speaker datasets, serving as a controlled benchmark for reproducible forensic analysis rather than to capture the full variability of real-world deepfake scenarios.

The dataset builds upon the well-established LJSpeech [

17] corpus, which provides high-quality recordings from a single English speaker. We carefully subsample and process these recordings to produce a balanced and consistent baseline. Each utterance is then synthesized using 11 distinct TTS architectures encompassing both autoregressive and non-autoregressive paradigms. After generation, all samples undergo a unified post-processing pipeline that includes amplitude normalization and silence trimming, to ensure consistency across generators. Additional quality control measures remove corrupted or mismatched samples, maintaining strict alignment among all speech variants.

LJ-TTS supports multiple research objectives within the broader domain of synthetic speech analysis. First, it serves as a forensic testbed for investigating how different TTS architectures encode spectral and temporal cues that reveal their synthetic nature. Second, it enables fair model attribution studies, where classifiers aim to identify the specific generator responsible for a synthetic sample. Third, LJ-TTS complements existing state-of-the-art corpora by serving as a test dataset for generalization studies, allowing researchers to evaluate whether detectors trained on one synthesis paradigm can accurately recognize deepfakes generated by another. Finally, because each sample has a precise one-to-one match between real and synthetic counterparts, LJ-TTS enables detailed analyses of pitch, duration, phoneme timing, and waveform artifacts that influence how deepfakes are perceived or detected. By providing parallel real and synthetic speech from multiple architectures, the dataset bridges the gap between TTS development and the forensic analysis of synthetic speech, promoting reproducible and interpretable research across both domains.

This paper makes the following contributions:

We introduce LJ-TTS, the first large-scale, single-speaker corpus pairing real recordings with synthetic speech from eleven distinct TTS generators.

By ensuring alignment between real and synthetic utterances, LJ-TTS allows researchers to isolate synthesis effects without interference from speaker or content variability.

We show how LJ-TTS supports diverse research tasks, including deepfake detection, TTS attribution, and fine-grained phonetic analysis.

The dataset, along with detailed documentation, is released publicly to facilitate research in speech deepfake detection and synthetic speech analysis (the dataset is available at

https://huggingface.co/datasets/violangg/LJ-TTS (accessed on 22 December 2025)).

The rest of this paper is organized as follows.

Section 2 provides background on speech synthesis and speech deepfake detection methods.

Section 3 describes the generation of LJ-TTS, including guiding principles, selection of reference data, synthesis methods, and post-processing procedures.

Section 4 offers an overview of the dataset’s structure and properties, summarizing its content and alignment characteristics.

Section 5 presents experiments demonstrating the utility of LJ-TTS for speech deepfake detection, source tracing of speech deepfakes, and phoneme-level analysis.

Section 6 discusses the broader implications, limitations, and potential extensions of the dataset for forensic and generative research. Finally,

Section 7 concludes with a summary of findings and perspectives on future directions in deepfake detection and trustworthy speech synthesis.

2. Background

This section provides an overview of speech synthesis and deepfake detection, focusing on neural Text-to-Speech (TTS) technologies and the challenges involved in distinguishing synthetic from real speech. We summarize key TTS architectures, state-of-the-art detection methods, and existing datasets, highlighting the motivation for developing a controlled, single-speaker benchmark such as LJ-TTS.

2.1. Speech Synthesis

Speech synthesis refers to the generation of human-like audio using machine learning and deep learning techniques. Over the past decade, advances in neural architectures have enabled systems to produce speech that not only achieves high intelligibility but also replicates natural rhythm, intonation, and expressiveness. Two major families of systems dominate this field: TTS and Voice Conversion (VC).

TTS systems transform written text into spoken language. Early approaches relied on concatenating pre-recorded segments of human speech, later replaced by Statistical Parametric Speech Synthesis (SPSS) based on HMMs and GMMs [

18]. With the rise of deep learning, TTS evolved into neural pipelines capable of producing far more natural and flexible outputs. Modern systems can be grouped into modular and end-to-end approaches. Modular pipelines typically consist of text analysis, acoustic modeling, and waveform generation via a vocoder, while end-to-end models integrate these stages into a single neural framework, directly mapping text to audio [

19,

20]. Neural vocoders such as WaveNet [

21], WaveRNN [

22], and HiFi-GAN [

23] synthesize high-quality audio from spectrograms that closely mimic human speech, achieving naturalness even in challenging prosodic patterns. GAN and transformer-based models [

23,

24] further improve expressiveness, prosody, and efficiency. Modern TTS models cover a range of architectures, including autoregressive systems, which generate speech sequentially conditioned on previous outputs, and non-autoregressive systems, which produce speech in parallel for faster inference. Many end-to-end pipelines integrate text analysis, acoustic modeling, and neural vocoders into a single framework. The generators included in LJ-TTS span both autoregressive and non-autoregressive approaches, providing a representative cross-section of contemporary TTS technologies.

In contrast, VC modifies an existing speech signal to resemble a different speaker while preserving its linguistic content. Unlike TTS, VC systems operate on audio input and typically require separate strategies for speaker identity and linguistic content. While advances in VC are notable, our focus is on TTS and the evaluation of generated speech across state-of-the-art TTS systems. These advances unlock valuable applications in entertainment, accessibility, and human–computer interaction, but they also enable highly convincing audio deepfakes, raising concerns about impersonation and misuse.

2.2. Deepfake Detection

The rapid advances in TTS and related generative technologies have enabled highly realistic synthetic speech, making automated detection increasingly important. Speech deepfake detection aims to distinguish real human speech from synthetically generated audio, a task that is critical for security, privacy, and trust in voice-based systems. Detection methods must account for diverse synthesis strategies, varying recording conditions, and subtle prosodic or acoustic artifacts that differentiate real from synthetic speech. The development of effective detectors relies on both sophisticated modeling techniques and carefully designed datasets that allow evaluation across multiple generators, speakers, and linguistic contexts.

2.2.1. State of the Art

Speech deepfake detection has progressed from traditional signal-processing approaches to a series of influential deep learning models. Early advances leveraged convolutional neural networks applied to mel-spectrograms, an idea borrowed from image classification. Notable examples include ResNet [

25] and LCNN [

26], which remain competitive and achieve state-of-the-art performance.

In parallel, approaches inspired by SincNet [

27] emerged. SincNet processes raw audio directly using parametrized band-pass filters, creating a filterbank specifically tailored for speech analysis. RawNet2 [

28] was an early application of this concept, combining SincNet filterbanks with residual blocks and feeding the resulting embeddings into Gated Recurrent Units (GRUs) for classification. To better model time–frequency dependencies, AASIST [

29] extended this idea by integrating spectral and temporal branches through a heterogeneous stacking graph attention mechanism, capturing joint artifacts across domains.

More recently, speech deepfake detection has shifted toward methods leveraging large Self-supervised Learning (SSL) encoders [

30], particularly wav2vec 2.0 [

31] and its multilingual extension XLS-R [

32]. Wav2vec 2.0 operates in the time domain with 1D convolutional layers followed by a transformer encoder, learning to predict masked latent speech representations. XLSR-AASIST [

33] first applied this approach by replacing SincNet features with XLS-R embeddings, improving detection performance and robustness. Later refinements, such as XLSR-SLS [

34], aggregated information from all transformer layers via a layer-wise weighted sum to capture artifacts at multiple levels of abstraction. Most recently, XLSR-Mamba [

35] introduced a state-space sequence encoder instead of the AASIST module. Unlike transformers, Mamba processes inputs sequentially, efficiently modeling long-range temporal patterns while capturing both short-term anomalies and long-term dependencies in synthetic speech.

2.2.2. Open Challenges

Although deepfake detection has achieved remarkable progress on benchmark datasets, persistent challenges remain in robustness [

36], generalization [

37,

38,

39], and interpretability [

40,

41]. Detection systems often overfit to dataset-specific artifacts or particular synthesis models, resulting in limited performance when evaluated on unseen generators or recording conditions. While multi-speaker datasets have been essential to advancing speech synthesis and detection, their diversity in speakers and recording conditions can sometimes make it difficult to disentangle synthesis artifacts from natural speaker-specific variability. This makes them less suited for controlled analyses that require isolating the contribution of synthesis methods from natural speaker variability.

At the same time, there is an increasing need for explainable detection and analysis methods that go beyond binary classification. Understanding which acoustic and prosodic features differentiate real from synthetic speech across TTS architectures remains an open problem. Addressing these issues requires controlled and well-aligned datasets that allow systematic comparison across models under identical linguistic and speaker conditions. Such resources are essential for advancing research on generalization, traceability, and the characterization of synthetic speech quality and detectability.

2.2.3. Existing Datasets

Several datasets have played a crucial role in advancing research on speech deepfake detection, each contributing different characteristics in terms of speaker diversity, linguistic coverage, and synthesis techniques. The ASVspoof series [

6,

16,

42] has been a cornerstone for evaluating spoofing countermeasures, offering both logical access and physical access scenarios with a variety of synthetic and replayed speech samples generated by both TTS and VC systems, later including post-processing conditions and adversarial attacks to better simulate real-world challenges. In-the-Wild [

9] provides unconstrained recordings sourced from real-world environments, capturing natural variability in background noise, recording devices, and speaking styles. The Fake or Real dataset [

10] focuses on distinguishing human speech from generated content, offering labeled samples that enable supervised learning for detection tasks. TIMIT-TTS [

11] and MLAAD [

8] further expand the landscape by including speech generated through multiple state-of-the-art TTS systems, covering diverse speakers and phonetic structures. DiffSSD [

15] introduces a complementary perspective by leveraging diffusion-based voice cloning models to provide challenging synthetic samples, highlighting artifacts that arise in more recent generative pipelines and offering an additional benchmark for detection performance. Recent datasets released in 2022 and 2023 [

13,

14] continue this trend by providing large-scale, linguistically diverse (Chinese), samples for evaluation.

WaveFake [

12] provides a valuable benchmark by synthesizing single-speaker data from the LJSpeech [

17] corpus using multiple vocoders. This resource allows researchers to isolate and study vocoder-specific artifacts, helping to evaluate the sensitivity of detection models to waveform-level distortions. However, the focus of these datasets is primarily on the waveform generation stage and does not fully capture the variability introduced by complete end-to-end TTS pipelines, including differences in linguistic content or in prosody modeling.

Before LJ-TTS, a controlled and systematic single-speaker dataset encompassing end-to-end TTS outputs across multiple architectures, which could serve as a comprehensive benchmark for the field, was still lacking. Such a resource enables: (1) rigorous comparison of detection models, (2) detailed analysis of both low-level waveform artifacts and high-level synthesis characteristics, and (3) the development of robust, explainable, and generalizable deepfake detection methods capable of operating across diverse TTS systems.

3. Dataset Generation

The LJ-TTS dataset was constructed to provide a unified and rigorously controlled benchmark for the analysis of synthetic speech. In this section, we describe the guiding principles behind its design, the reference data, the synthesis methods employed, and the post-processing steps applied to ensure high-quality, consistent audio samples. By systematically generating and curating speech from a single speaker across multiple state-of-the-art TTS architectures, LJ-TTS enables controlled experiments and detailed investigations into both low-level waveform properties and higher-level linguistic and prosodic characteristics.

3.1. Design Principles

The LJ-TTS corpus was designed to provide a controlled and comprehensive resource for the study of TTS synthesis and synthetic speech detection. The primary goal is to enable systematic comparison across multiple state-of-the-art TTS architectures while minimizing confounding factors such as speaker variability or recording inconsistencies.

To achieve this, we selected a single high-quality female English speaker as the reference source, i.e., Linda Johnson from LJSpeech [

17], to ensure consistent recording conditions for all utterances. Synthetic speech was then generated using a diverse set of 11 well-established TTS models, encompassing both autoregressive and non-autoregressive architectures, to capture a broad spectrum of synthesis strategies. Additional post-processing and normalization steps were applied to reduce dataset shortcuts and spurious artifacts, ensuring that analyses focus on model-specific characteristics rather than incidental noise or inconsistencies.

Importantly, each utterance in LJ-TTS exists in twelve aligned versions: one real recording and eleven synthetic counterparts. This strict one-to-one correspondence ensures that each synthetic signal is directly comparable to the original recording, allowing for systematic analyses of model-specific characteristics without confounding any linguistic content variability.

3.2. Reference Data

The real speech data in LJ-TTS is sourced from the LJSpeech dataset [

17], a widely used single-speaker corpus for text-to-speech research. LJSpeech contains 13,100 short audio clips, averaging approximately 6 s each, for a total of roughly 24 h of speech, recorded at 22,050 Hz. All recordings were produced by a single female speaker, Linda Johnson, reading passages from seven non-fiction books in American English, using a MacBook Pro microphone in a consistent recording environment with low background noise. The dataset features cleaned and normalized text transcripts with most punctuation preserved, making it suitable for end-to-end TTS training and evaluation. For LJ-TTS, we randomly subsample 4817 utterances from LJSpeech to form a balanced set, ensuring that each synthetic speech generator and the real class share the exact same utterances.

3.3. Synthesis Methods

Since LJSpeech serves as a standard training corpus for TTS models, we identified eleven pre-trained generators trained on this dataset and publicly released by their authors. These models collectively represent a diverse range of synthesis strategies, covering both autoregressive and non-autoregressive paradigms, as well as a mix of attention-based, flow-based, and convolutional architectures. Each model was used to synthesize all 4817 reference utterances, producing a fully aligned multi-generator corpus that enables detailed cross-model comparison.

The included systems are as follows:

FastPitch [43]: Non-autoregressive model, conditioned on fundamental frequency contours, that enables fast and controllable pitch and duration modeling.

FastSpeech2 [24]: Transformer-based feed-forward model with a variance adaptor that predicts duration, pitch, and energy, achieving high-speed inference with fine-grained prosody control.

Glow-TTS [44]: Flow-based generative architecture that learns a probabilistic latent space for expressive and flexible speech synthesis.

MixerTTS [45]: Transformer-based encoder–decoder system with a variance adaptor predicting token durations, pitch, and energy.

MixerTTS_X [45]: Extended MixerTTS variant that incorporates token embeddings from a pre-trained language model for enhanced linguistic conditioning.

Speedy-Speech [46]: Lightweight, non-autoregressive, student-teacher architecture using convolutional blocks with residual connections, optimized for fast synthesis.

TalkNet [47]: Duration-informed parallel synthesis model that explicitly predicts token durations before waveform generation.

Silero [48]: Compact neural TTS focused on low-latency, high-quality speech for edge deployment.

Tacotron2-DDC [20]: A seq2seq model, with an encoder-decoder structure, equipped with Double Decoder Consistency (DDC) to provide a more expressive and natural prosody.

Tacotron2-DDC_ph [20]: Phoneme-conditioned Tacotron2-DDC variant offering improved pronunciation consistency.

Tacotron2-DCA [20]: Tacotron2 extension employing Dynamic Convolutional Attention (DCA) for more stable alignment and expressive synthesis.

All models were executed with their official pretrained weights and default synthesis parameters to ensure reproducibility and comparability. Each generator processed the same normalized text transcripts, producing waveform outputs directly from the reference utterances without manual post-editing.

3.4. Post-Processing

To ensure consistency and minimize detection shortcuts, all audio tracks in LJ-TTS, both real and synthetic, underwent a standardized post-processing pipeline, including global resampling to 16 kHz, peak normalization, and uniform trimming of leading and trailing silence. This procedure is intended to remove superficial amplitude- and silence-related cues that detectors might otherwise exploit, while preserving meaningful synthesis-specific artifacts such as vocoding and acoustic modeling characteristics [

7,

49,

50].

First, all recordings were resampled to 16 kHz, the most common sampling rate among the selected generators. In particular, the original real recordings (22,050 Hz) were downsampled to match this rate, ensuring consistent time and frequency resolution across all samples.

Next, we applied peak amplitude normalization to ensure uniform loudness across all recordings, as in:

This normalization prevents amplitude-related cues from influencing detection or comparison analyses.

Leading and trailing silences were removed using an energy-based thresholding approach, with the decibel threshold empirically set to 40 dB to reliably trim silent regions while preserving speech content. This step was particularly important because 6 of the synthetic generators (FastPitch, Glow-TTS, Speedy-Speech, Tacotron2-DDC_ph, Tacotron2-DCA, Tacotron2-DDC) consistently introduced completely silent segments at the beginning or end of some tracks, and occasionally within tracks. Although such silent regions could, in principle, serve as a trivial cue for identifying these generators [

49], we assume that a careful adversary would likely detect and remove them, making them unreliable as a forensic feature. By trimming these silences, we ensured that volume normalization and downstream analyses are not affected by extraneous silent regions, while preserving the speech content for accurate waveform, prosody, and phoneme-level investigations.

Finally, we conducted a quality-control and alignment check to remove tracks that were somehow corrupted by a TTS system. As a criterion, we compared the duration of each synthetic track to the corresponding real reference: tracks differing by more than 2 were discarded. To preserve symmetry, if a sample was removed from one generator, the corresponding utterances from all other generators and the real class were also excluded. This guarantees full alignment and ensures that all classes contain an identical set of utterances, maintaining dataset integrity for fair cross-model comparison.

4. Dataset Overview

In this section, we provide a detailed description of the LJ-TTS dataset, including its structure and statistical properties. We present both signal-level and prosodic analyses to highlight how different TTS generators compare with real speech in terms of duration, energy, and pitch variability.

4.1. Summary Stastistics

A comparative overview of LJ-TTS characteristics and other state-of-the-art datasets discussed in

Section 2.2.3, is provided in

Table 1. Our proposed dataset contains 57,804 audio tracks, evenly distributed across the 11 synthetic speech generators and the real speech class, with each class containing 4817 utterances that share identical textual and linguistic content. All synthetic samples are generated at a sampling rate of 16

, and the original real speech recordings (initially at 22,050 Hz) were downsampled to the same rate to ensure direct comparability across all classes.

Table 2 summarizes key signal-level statistics before and after post-processing (see

Section 3.4), including average duration, root mean square (RMS) energy, peak amplitude, and amplitude level in dB. Post-processing clearly produces more uniform duration distributions and standardized amplitude levels, leading to consistent loudness across generators. Notably, small residual differences remain: for example, Glow-TTS and Tacotron2-DDC traces tend to be slightly longer than real speech on average, while other generators are slightly shorter; similar minor variations are observed in RMS energy. Importantly, these differences are not systematic and do not provide exploitable shortcuts for detectors. Overall, this normalization ensures that observed differences in downstream analyses can be attributed primarily to forensic traces introduced by the generation process, rather than to amplitude or silence-related artifacts.

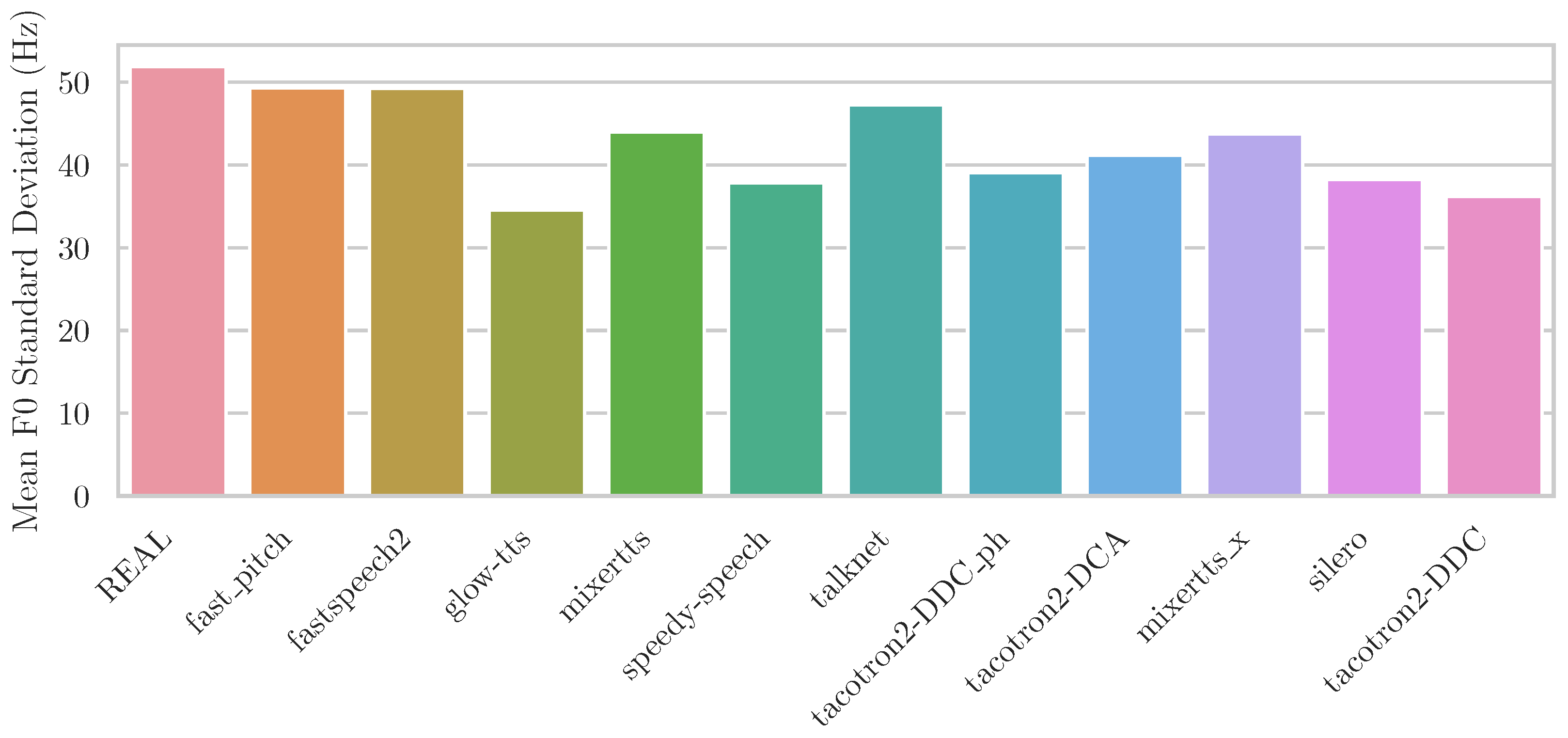

Table 3 reports the distribution of the fundamental frequency (

) for real and synthetic speech across all generators. Overall, the real speech maintains a mean

of approximately 217

, consistent with a female speaker’s natural pitch range. Synthetic speech generally exhibits comparable

means but with varying standard deviations and ranges, reflecting differences in pitch modeling and prosody control across TTS architectures. As shown in

Figure 1, generative models such as Glow-TTS, Tacotron2 variants, Silero, and SpeedySpeech exhibit reduced

variability, indicating smoother yet less expressive intonation compared to real speech.

4.2. Spectral Comparison

Analyzing the spectral characteristics of the audio tracks is essential for identifying differences introduced by the generation process. Having identical utterances across all classes allows for precise and direct comparisons of their time–frequency representations.

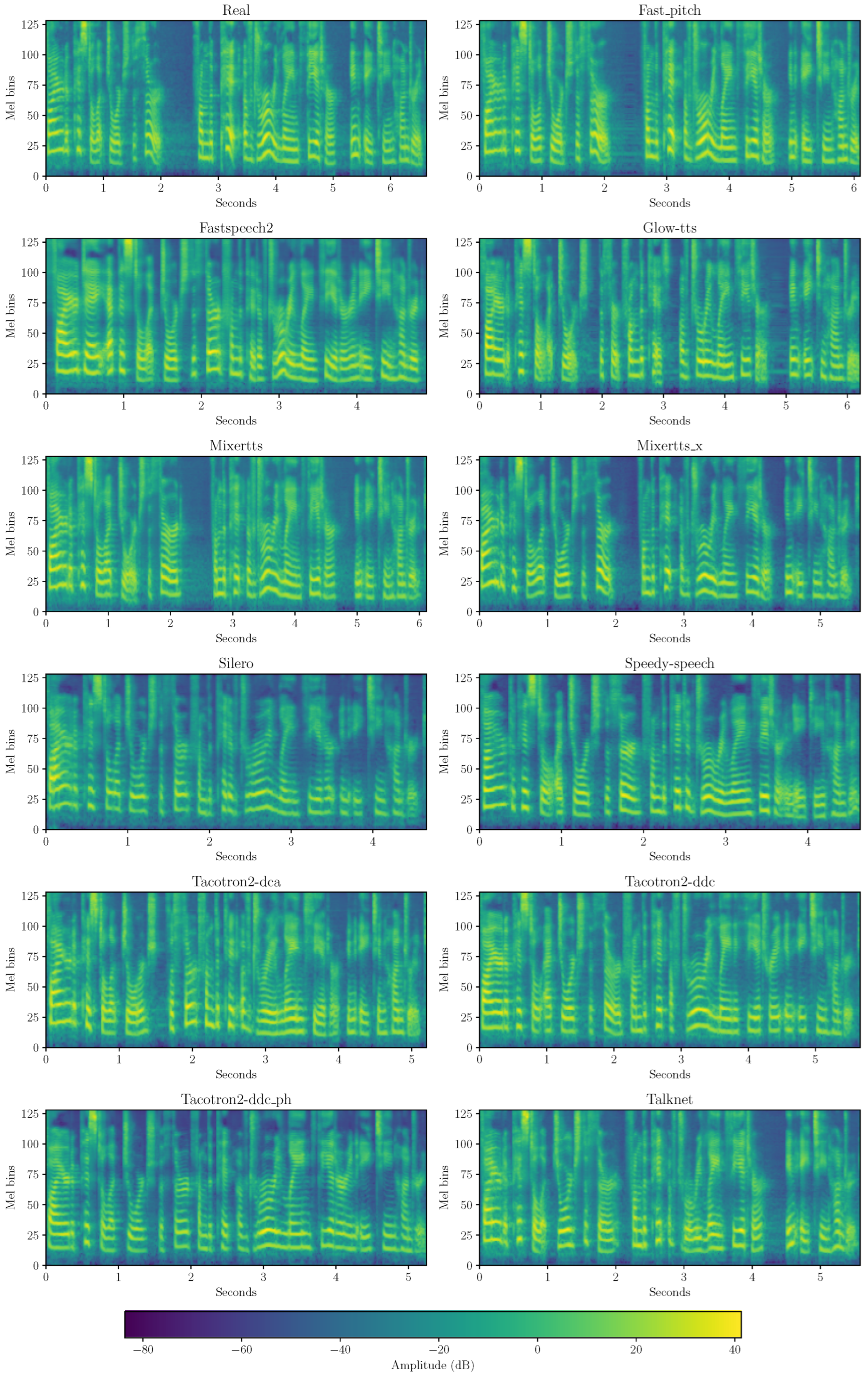

Figure 2 shows the mel-spectrograms of an example track from LJ-TTS (

LJ010-0152.wav) across all the 12 classes. Mel-spectrograms are adopted here due to their perceptual relevance: they reveal differences in duration, silence handling, formant structure, and harmonic richness. Tacotron2 variants, Glow-TTS, and Silero tend to produce flatter formants and harmonics compared with the real recording (top left), consistent with the reduced

variability discussed in

Section 4.1.

Another prominent difference between the real sample and the generated counterparts concerns silence handling. In particular, there is a consistent pause of the speaker right after 2 , lasting roughly . This silence is clearly reproduced in the FastPitch and MixerTTS models, although slightly shorter or shifted in time, whereas it is mostly absent in the remaining synthetic versions. This behavior is expected, as most TTS systems receive only text as input and infer pauses indirectly from punctuation or from duration models that may include dedicated tokens for silence. The extent to which these cues are preserved depends on model architecture, preprocessing, and prosody modeling, which could explain the different degrees of pause reproduction observed across generators. This behavior is also reflected in the overall duration of the tracks: the original real utterance lasts nearly 7 , while most synthetic versions are shorter, with Silero and Speedy-Speech producing outputs under 4 .

5. Experiments

In this section, we benchmark the generated data across three tasks relevant to speech deepfake detection. First, we assess how challenging LJ-TTS is as an evaluation benchmark for binary real-versus-fake detection. Second, we perform source verification to determine whether the dataset’s classes are easily distinguishable and to what extent model-specific characteristics can be identified. Finally, leveraging the dataset’s strong alignment across utterances, we conduct a phoneme-level analysis to examine which phoneme categories contribute most to detecting specific generators within LJ-TTS.

5.1. Deepfake Detection

First, we evaluate whether LJ-TTS constitutes a valuable benchmark for the speech deepfake detection task, formulated as a binary real-versus-fake classification problem at the sample level. To this end, we employ four state-of-the-art detectors (see

Section 2.2): LCNN, ResNet18, RawNet2, and AASIST. Each model is trained separately on two standard datasets from the ASVspoof series: ASVspoof 2019 [

6] and ASVspoof 5 [

7]. The ASVspoof 2019 dataset has long served as the primary benchmark for speech deepfake detection, due to its manageable scale and well-established evaluation protocol, whereas ASVspoof 5, released at the end of 2024, is progressively emerging as the new standard, incorporating more recent TTS technologies (see

Table 1).

All models are trained from scratch using the official train/dev splits for ASVspoof 2019 and the combined (train+dev) partition for ASVspoof 5. Prior to training, each sample is preprocessed by trimming leading and trailing silences and normalizing the peak amplitude, in order to remove shortcut artifacts that could otherwise impair model generalization in open-set conditions.

Table 4 reports the results of this experiment in terms of Equal Error Rate (EER) and Area Under the Curve (AUC), where lower EER and higher AUC indicate better performance. Models trained on ASVspoof 2019 exhibit limited generalization to LJ-TTS, with EERs ranging from 28% to 39% and AUC values below 77%. This indicates that LJ-TTS constitutes a challenging open-set benchmark, exposing differences between traditional datasets and more recent, diverse TTS outputs. Conversely, models trained on ASVspoof 5 achieve substantially higher performance, with AASIST reaching near-perfect discrimination (AUC above 99%). This improvement is likely due to the inclusion of more modern TTS systems in ASVspoof 5, which are temporally and technologically closer to, and in some cases overlapping with, the generators represented in LJ-TTS, whereas ASVspoof 2019 primarily contains earlier architectures.

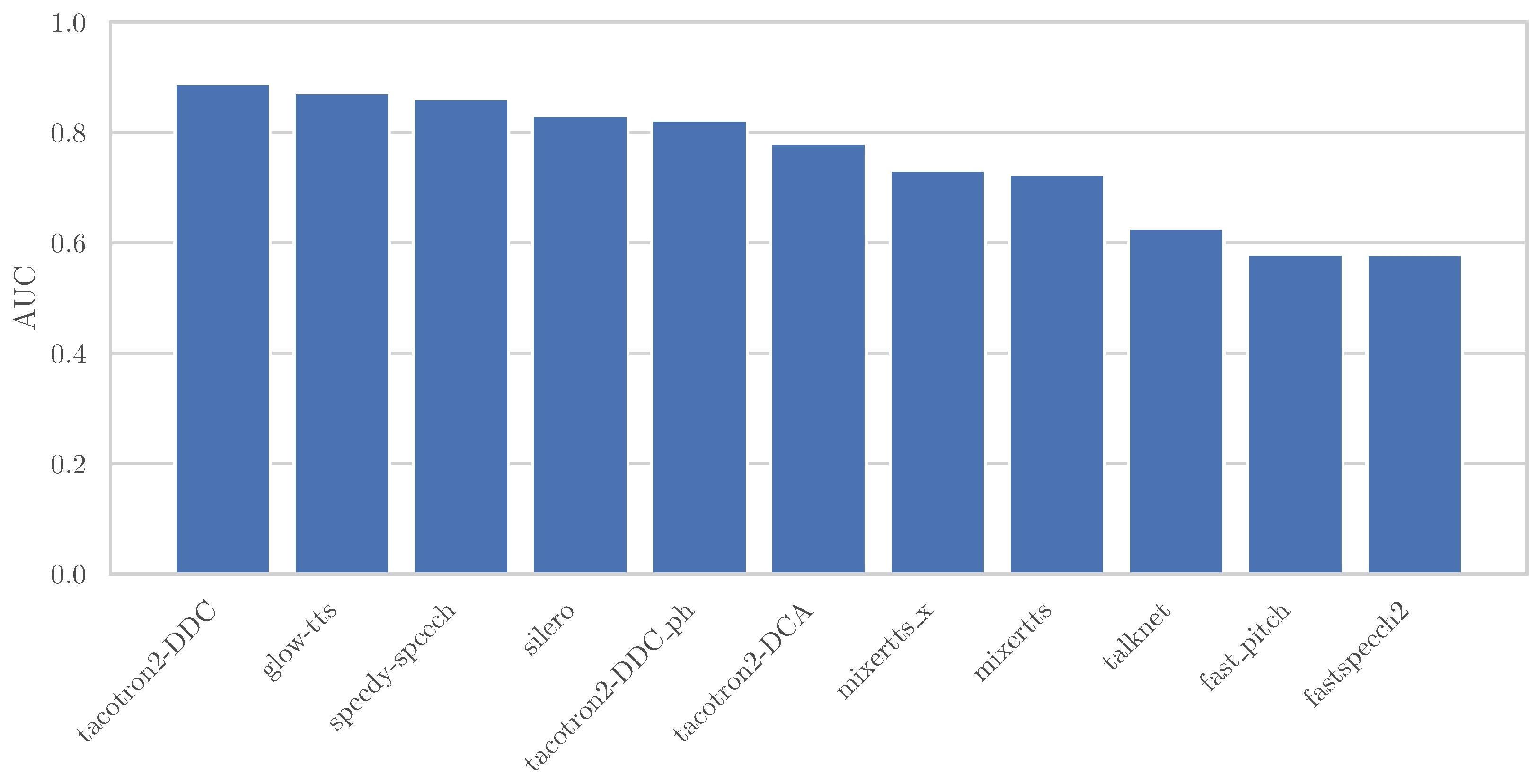

While the LJ-TTS generators were selected for architectural diversity rather than strict recency, their relative maturity also enables an investigation of whether fundamental prosodic cues alone can support real-versus-fake discrimination. To this end, also based on the observations made in

Section 4.1 and

Section 4.2, we now analyze detection performance using only the variability of the fundamental frequency (

) as a feature.

Figure 3 shows the AUC values for speech deepfake detection obtained when using solely the standard deviation of the fundamental frequency

as the discriminative feature. Interestingly, all generators exceed 50% AUC, with results ranging from 57.79% for FastSpeech2 to 88.83% for Tacotron2-DDC. Although these values should not be interpreted as evidence of full discriminative capability, they suggest that variability in

alone carries non-negligible information about the synthesis process, yielding performance in some cases comparable to detectors trained on ASVspoof 2019 (see

Table 4).

5.2. Source Verification

In this experiment, we investigate source verification [

51], a subtask of source tracing for speech deepfakes that aims to determine whether two synthetic audio samples originate from the same generative model. Unlike closed-set attribution approaches, which require explicit training on all known generators, source verification operates in a comparison-based framework. Specifically, embeddings from a query track are compared against embeddings of reference signals to infer whether they originate from the same generative source. This verification paradigm eliminates the need for exhaustive training on every possible generator, allowing new reference models to be added dynamically.

As the backbone model, we adopt a ResNet18 architecture, which was selected following prior work in which multiple models were evaluated and relative source verification trends were shown to be stable across architectures [

51]. MLAAD is retained as the training corpus, as in [

51], because, like LJ-TTS, it consists exclusively of TTS-generated speech and is currently the only dataset of this kind with sufficient scale to support efficient training for source verification. We note that the conclusions drawn in this study are therefore scoped to such adopted architecture and training configuration.

We filter MLAAD to retain only English-language generators and train two versions of the ResNet18 model: one on 10 random non-LJSpeech English generators, and another on the 10 LJSpeech-based generators. Both models are then evaluated on (a) the proposed LJ-TTS dataset (considering all the synthetic samples from its 11 generators) and (b) the MLAAD subset comprising the same LJSpeech-based generators, using test tracks disjoint from those used for training.

The results in

Table 5 show a clear distinction between the two training configurations. The model trained on LJSpeech-based generators achieves strong verification performance both on MLAAD and on the proposed LJ-TTS dataset (AUC values above 90%), indicating that the acoustic and stylistic characteristics of the generators are well captured when the training and test data share a similar speaker identity and linguistic domain. In contrast, the model trained on non-LJSpeech generators performs substantially worse, particularly on the MLAAD (LJ) test set (AUC 62.4%). Interestingly, this second model performs comparatively better on LJ-TTS (AUC 75.6%), despite not being trained on LJSpeech-based voices. One possible explanation is that LJ-TTS, although voiced by the same speaker as MLAAD-LJ, exhibits more consistent acoustic conditions and less intra-generator variability, likely as a result of its standardized post-processing

Section 3.4, making structural differences between generators more salient even for a model trained on different voices.

5.3. Phoneme-Level Analysis

To investigate fine-grained characteristics of the generated tracks, we adopt a phoneme-level methodology inspired by the Person-of-Interest (POI)-based detection approach proposed in [

52]. Rather than treating each audio track as a single entity, this method decomposes speech into individual phonemes and uses them to perform the detection process. All phonemes are grouped into seven categories based on the standard International Phonetic Alphabet (IPA) classification (

Table 6), as in prior works, facilitating comparison with existing studies [

52,

53,

54]. For every phoneme, we compute a dedicated embedding. Then, we aggregate the phoneme-level embeddings derived from real speech to construct a speaker-specific phoneme profile. This profile serves as a reference for evaluating test samples.

Following the procedure described in [

52], we randomly select 100 real speech tracks from the LJ-TTS dataset to build the speaker profile. The remaining tracks are used as test samples. Each test track is then compared against the reference profile by analyzing the correspondence between phonetic units. In this comparison, phonemes that appear more distant from the reference profile are categorized as fake, whereas those that align closely with the profile are classified as real. Eventually, this process can reveal which phoneme groups provide the most discriminative cues for distinguishing genuine speech from generated audio. We conduct experiments using one phoneme category at a time to assess phoneme-level detection performance. The aim of this analysis is to ultimately identify which phoneme classes are most difficult for deepfake generators to reproduce accurately and, consequently, which contribute most to effective detection.

Table 7 shows the results of this analysis. Affricates alone achieve the best detection performance, with an AUC of 76.60%, outperforming all other phoneme categories. This indicates that affricates, such as /t∫/ and /ʤ/, carry strong discriminative cues that reveal inconsistencies in synthetic speech. In contrast, all other phoneme groups exhibit relatively lower performance (AUC around 73%), suggesting that these sounds are generally reproduced more faithfully by neural TTS systems. The combined performance across all phonemes remains around 73%, implying that phoneme-specific representations provide more discriminative power than aggregate ones for this dataset.

Table 8 further details results per generator. Affricates consistently yield the highest AUC values across all architectures, confirming their robustness as discriminative features, particularly for models such as Speedy-Speech (79.82% AUC) and Glow-TTS (77.31% AUC). To confirm that this superiority is not coincidental, we performed a paired

t-test comparing the AUC of affricates against the mean AUC of all other phoneme groups across generators. The results show a highly significant difference (

,

), supporting the significance of affricates’ enhanced discriminative power.

Interestingly, our results contrast with those reported in [

52], where vowels emerged as the most informative phoneme class for distinguishing real from synthetic speech. A plausible explanation lies in differences in dataset composition and phoneme coverage. In the state-of-the-art datasets used in [

52], vowels typically dominate the signal in terms of frequency of occurrence, as also noted by the authors. When embeddings are aggregated across many utterances and speakers, this higher representation may render vowel-based statistics more stable and thus more informative overall. Conversely, in a clean, controlled, single-speaker dataset with aligned linguistic content such as LJ-Speech, other less frequent phoneme groups can become more distinctive.

Previous studies [

53,

55] have also identified fricatives and nasals as salient for deepfake detection, highlighting that different datasets and model architectures may emphasize different acoustic cues. These works suggest that no single phoneme class is universally optimal for detection, but the most informative categories depend on the phoneme distribution, dataset characteristics, and synthesis model properties, all of which influence how artifacts manifest in the speech signal. In our case, the prominence of affricates may stem from the recording quality of the LJSpeech corpus: Linda Johnson’s clear articulation and strong high-frequency content make real affricates particularly consistent, rendering synthetic ones easier to detect.

6. Discussion and Limitations

LJ-TTS was designed as a controlled and transparent benchmark to support systematic research on synthetic speech generation and detection. Its single-speaker, parallel structure provides a unique setting to analyze how different TTS systems modify acoustic and prosodic features while keeping linguistic content and speaker identity fixed. Our experiments on deepfake detection, source verification, and phoneme-level analysis show that such control reveals subtle, synthesis-specific patterns, underscoring the value of aligned datasets for both forensic and generative studies.

Despite these strengths, several limitations should be acknowledged. First, the present release covers only a subset of the original LJSpeech corpus, constraining linguistic and phonetic diversity. Future versions of LJ-TTS will progressively incorporate the full corpus to expand utterance coverage and enable broader analyses of prosodic and spectral variability. Second, the dataset currently focuses on a single American English female voice. Future iterations will include additional speakers with different linguistic and demographic backgrounds, yet always maintaining utterance-level correspondence across real and synthetic versions. This will make it possible to study how synthesis artifacts generalize across voices, accents, and genders.

Another limitation concerns the temporal coverage of synthesis technologies. The current LJ-TTS release features generators representative of the state-of-the-art of today. Future releases of LJ-TTS will expand to cover a broader and more contemporary set of TTS architectures. This includes diffusion-based generators, which provide improved naturalness and prosodic control; large-scale zero-shot systems, capable of synthesizing speech from previously unseen speakers; and commercial-grade architectures, representative of widely deployed production systems. All expansions will maintain the controlled, utterance-level alignment of LJ-TTS, ensuring that the dataset continues to support reproducible, fine-grained forensic analysis while progressively reflecting contemporary synthesis technologies.

Overall, LJ-TTS should be regarded as a foundation for reproducible and fine-grained analyses of synthetic speech. Its design promotes controlled evaluation of deepfake detection methods, interpretability studies, and cross-generator generalization, and it is intended to evolve in scope and coverage as TTS technology advances.

LJ-TTS is released with the explicit goal of supporting research in speech forensics, deepfake detection, and the development of defensive technologies. While the dataset contains only synthetic speech generated from publicly available recordings, we acknowledge that such resources may be misused to benchmark or refine generative models. We encourage users of the dataset to adhere to responsible research practices and to consider the broader societal implications of synthetic speech technologies.

7. Conclusions

In this work, we introduced LJ-TTS, a novel single-speaker speech deepfake dataset designed to enable reliable and interpretable research on synthetic speech. By maintaining exact alignment between real and generated utterances across eleven state-of-the-art TTS systems, LJ-TTS isolates synthesis-specific cues from linguistic or speaker-related variability, providing a consistent foundation for comparative and diagnostic studies.

Beyond its role as a benchmark, LJ-TTS bridges forensic and generative perspectives within a unified corpus. It supports controlled evaluation of deepfake detection, model attribution, and phoneme-level interpretability, while also facilitating cross-architecture and cross-domain generalization analyses. Its structured and transparent design ensures that experimental findings remain reproducible and comparable across studies.

Looking ahead, LJ-TTS is intended to evolve as a living resource that keeps pace with advances in neural speech synthesis. Future extensions will broaden its scope through increased speaker diversity and expanded technological coverage. By fostering collaboration between the speech synthesis and security communities, LJ-TTS aims to advance the development of transparent, trustworthy, and scientifically grounded methods for the detection and understanding of synthetic speech.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, V.N., D.S., I.A., S.T. and P.B.; Methodology, V.N. and D.S.; Validation, V.N.; Formal analysis, V.N.; Investigation, V.N., D.S., L.C., T.M.W. and M.U.; Data curation, D.S. and M.U.; Writing—original draft, V.N.; Writing—review & editing, D.S., L.C. and T.M.W.; Supervision, I.A., S.T. and P.B.; Funding acquisition, S.T. and P.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the FOSTERER project, funded by the Italian Ministry of Education, University, and Research within the PRIN 2022 program. This work was partially supported by the European Union–Next Generation EU under the Italian National Recovery and Resilience Plan (NRRP), Mission 4, Component 2, Investment 1.3, CUP D43C22003080001, partnership on “Telecommunications of the Future” (PE00000001–program “RESTART”). This work was partially supported by the European Union–Next Generation EU under the Italian National Recovery and Resilience Plan (NRRP), Mission 4, Component 2, Investment 1.3, CUP D43C22003050001, partnership on “SEcurity and RIghts in the CyberSpace” (PE00000014–program “FF4ALL-SERICS”).

Data Availability Statement

The datasets presented in this article are currently being prepared for sharing, and all authors are reviewing them for accuracy and completeness. Requests to access the datasets in the meantime should be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Barakat, H.; Turk, O.; Demiroglu, C. Deep learning-based expressive speech synthesis: A systematic review of approaches, challenges, and resources. EURASIP J. Audio Speech Music. Process. 2024, 2024, 11. [Google Scholar]

- Ajder, H.; Patrini, G.; Cavalli, F.; Cullen, L. The State of Deepfakes: Landscape, Threats, and Impact. Technical Report, Deeptrace (now Sensity AI), Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2019. Available online: https://regmedia.co.uk/2019/10/08/deepfake_report.pdf (accessed on 22 December 2025).

- Maras, M.H.; Alexandrou, A. Determining authenticity of video evidence in the age of artificial intelligence and in the wake of Deepfake videos. Int. J. Evid. Proof 2019, 23, 255–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaccari, C.; Chadwick, A. Deepfakes and disinformation: Exploring the impact of synthetic political video on deception, uncertainty, and trust in news. Soc. Media+ Soc. 2020, 6, 2056305120903408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wani, T.M.; Qadri, S.A.A.; Wani, F.A.; Amerini, I. Navigating the Soundscape of Deception: A Comprehensive Survey on Audio Deepfake Generation, Detection, and Future Horizons. Found. Trends® Priv. Secur. 2024, 6, 153–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Yamagishi, J.; Todisco, M.; Delgado, H.; Nautsch, A.; Evans, N.; Sahidullah, M.; Vestman, V.; Kinnunen, T.; Lee, K.A.; et al. ASVspoof 2019: A large-scale public database of synthesized, converted and replayed speech. Comput. Speech Lang. 2020, 64, 101114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Delgado, H.; Tak, H.; Jung, J.w.; Shim, H.j.; Todisco, M.; Kukanov, I.; Liu, X.; Sahidullah, M.; Kinnunen, T.; et al. ASVspoof 5: Crowdsourced speech data, deepfakes, and adversarial attacks at scale. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2408.08739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, N.M.; Kawa, P.; Choong, W.H.; Casanova, E.; Gölge, E.; Müller, T.; Syga, P.; Sperl, P.; Böttinger, K. MLAAD: The multi-language audio anti-spoofing dataset. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Joint Conference on Neural Networks (IJCNN), Yokohama, Japan, 30 June–5 July 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Müller, N.; Czempin, P.; Diekmann, F.; Froghyar, A.; Böttinger, K. Does Audio Deepfake Detection Generalize? In Proceedings of the Interspeech, Incheon, Republic of Korea, 18–22 September 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Reimao, R.; Tzerpos, V. FoR: A dataset for synthetic speech detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Speech Technology and Human-Computer Dialogue (SpeD), Timisoara, Romania, 10–12 October 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Salvi, D.; Hosler, B.; Bestagini, P.; Stamm, M.C.; Tubaro, S. TIMIT-TTS: A text-to-speech dataset for multimodal synthetic media detection. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 50851–50866. [Google Scholar]

- Frank, J.; Schönherr, L. WaveFake: A Data Set to Facilitate Audio Deepfake Detection. In Proceedings of the NeurIPS (Track on Datasets and Benchmarks), Virtual, 6–14 December 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Yi, J.; Fu, R.; Tao, J.; Nie, S.; Ma, H.; Wang, C.; Wang, T.; Tian, Z.; Bai, Y.; Fan, C.; et al. Add 2022: The first audio deep synthesis detection challenge. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP), Singapore, 23–27 May 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Yi, J.; Tao, J.; Fu, R.; Yan, X.; Wang, C.; Wang, T.; Zhang, C.; Zhang, X.; Zhao, Y.; Ren, Y.; et al. ADD 2023: The Second Audio Deepfake Detection Challenge. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2305.13774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhagtani, K.; Yadav, A.K.S.; Bestagini, P.; Delp, E.J. DiffSSD: A Diffusion-Based Dataset For Speech Forensics. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP), Hyderabad, India, 6–11 April 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, X.; Wang, X.; Sahidullah, M.; Patino, J.; Delgado, H.; Kinnunen, T.; Todisco, M.; Yamagishi, J.; Evans, N.; Nautsch, A.; et al. ASVspoof 2021: Towards spoofed and deepfake speech detection in the wild. IEEE ACM Trans. Audio Speech Lang. Process. 2023, 31, 2507–2522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ito, K.; Johnson, L. The LJ Speech Dataset. 2017. Available online: https://keithito.com/LJ-Speech-Dataset/ (accessed on 22 December 2025).

- Zen, H.; Senior, A.; Schuster, M. Statistical parametric speech synthesis using deep neural networks. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP), Vancouver, BC, Canada, 26–31 May 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Skerry-Ryan, R.; Stanton, D.; Wu, Y.; Weiss, R.J.; Jaitly, N.; Yang, Z.; Xiao, Y.; Chen, Z.; Bengio, S.; et al. Tacotron: Towards end-to-end speech synthesis. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1703.10135. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, J.; Pang, R.; Weiss, R.J.; Schuster, M.; Jaitly, N.; Yang, Z.; Chen, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Skerrv-Ryan, R.; et al. Natural tts synthesis by conditioning wavenet on mel spectrogram predictions. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP), Calgary, AB, Canada, 15–20 April 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Oord, A.v.d. WaveNet: A Generative Model for Raw Audio. arXiv 2016, arXiv:1609.03499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalchbrenner, N.; Elsen, E.; Simonyan, K.; Noury, S.; Casagrande, N.; Lockhart, E.; Stimberg, F.; Oord, A.; Dieleman, S.; Kavukcuoglu, K. Efficient neural audio synthesis. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning, PMLR, Stockholm, Sweden, 10–15 July 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Kong, J.; Kim, J.; Bae, J. Hifi-gan: Generative adversarial networks for efficient and high fidelity speech synthesis. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2020, 33, 17022–17033. [Google Scholar]

- Ren, Y.; Hu, C.; Tan, X.; Qin, T.; Zhao, S.; Zhao, Z.; Liu, T.Y. FastSpeech 2: Fast and High-Quality End-to-End Text to Speech. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR), Virtual, 3–7 May 2021. [Google Scholar]

- He, K.; Zhang, X.; Ren, S.; Sun, J. Deep residual learning for image recognition. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Las Vegas, NV, USA, 27–30 June 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, X.; He, R.; Sun, Z.; Tan, T. A light CNN for deep face representation with noisy labels. IEEE Trans. Inf. Forensics Secur. 2018, 13, 2884–2896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravanelli, M.; Bengio, Y. Speaker recognition from raw waveform with sincnet. In Proceedings of the IEEE Spoken Language Technology Workshop (SLT), Athens, Greece, 18–21 December 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Tak, H.; Patino, J.; Todisco, M.; Nautsch, A.; Evans, N.; Larcher, A. End-to-end anti-spoofing with RawNet2. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP), Toronto, ON, Canada, 6–11 June 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Jung, J.w.; Heo, H.S.; Tak, H.; Shim, H.j.; Chung, J.S.; Lee, B.J.; Yu, H.J.; Evans, N. AASIST: Audio anti-spoofing using integrated spectro-temporal graph attention networks. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP), Singapore, 23–27 May 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Salvi, D.; Yadav, A.K.S.; Bhagtani, K.; Negronil, V.; Bestagini, P.; Delp, E.J. Comparative Analysis of ASR Methods for Speech Deepfake Detection. In Proceedings of the 58th Asilomar Conference on Signals, Systems, and Computers, Pacific Grove, CA, USA, 27–30 October 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Baevski, A.; Zhou, Y.; Mohamed, A.; Auli, M. wav2vec 2.0: A framework for self-supervised learning of speech representations. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2020, 33, 12449–12460. [Google Scholar]

- Babu, A.; Wang, C.; Tjandra, A.; Lakhotia, K.; Xu, Q.; Goyal, N.; Singh, K.; von Platen, P.; Saraf, Y.; Pino, J.; et al. XLS-R: Self-supervised Cross-lingual Speech Representation Learning at Scale. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2111.09296. [Google Scholar]

- Tak, H.; Todisco, M.; Wang, X.; Jung, J.w.; Yamagishi, J.; Evans, N. Automatic speaker verification spoofing and deepfake detection using wav2vec 2.0 and data augmentation. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2202.12233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Wen, S.; Hu, T. Audio deepfake detection with self-supervised XLS-R and SLS classifier. In Proceedings of the 32nd ACM International Conference on Multimedia, Melbourne, Australia, 28 October–1 November 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Xiao, Y.; Das, R.K. XLSR-Mamba: A dual-column bidirectional state space model for spoofing attack detection. IEEE Signal Process. Lett. 2025, 32, 1276–1280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Chen, P.Y.; Wei, W. Measuring the Robustness of Audio Deepfake Detectors. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2503.17577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, N.M.; Evans, N.; Tak, H.; Sperl, P.; Böttinger, K. Harder or Different? Understanding Generalization of Audio Deepfake Detection. In Proceedings of the Interspeech, Kos Island, Greece, 1–5 September 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Kawa, P.; Plata, M.; Syga, P. Attack Agnostic Dataset: Towards Generalization and Stabilization of Audio DeepFake Detection. In Proceedings of the Interspeech, Incheon, Republic of Korea, 18–22 September 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Coletta, E.; Salvi, D.; Negroni, V.; Leonzio, D.U.; Bestagini, P. Anomaly detection and localization for speech deepfakes via feature pyramid matching. In Proceedings of the European Signal Processing Conference (EUSIPCO), Palermo, Italy, 8–12 September 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Cuccovillo, L.; Papastergiopoulos, C.; Vafeiadis, A.; Yaroshchuk, A.; Aichroth, P.; Votis, K.; Tzovaras, D. Open challenges in synthetic speech detection. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE International Workshop on Information Forensics and Security (WIFS), Shanghai, China, 12–16 December 2022; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Salvi, D.; Bestagini, P.; Tubaro, S. Towards frequency band explainability in synthetic speech detection. In Proceedings of the European Signal Processing Conference (EUSIPCO), Helsinki, Finland, 4–8 September 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.; Delgado, H.; Tak, H.; Jung, J.w.; Shim, H.j.; Todisco, M.; Kukanov, I.; Liu, X.; Sahidullah, M.; Kinnunen, T.; et al. ASVspoof 5: Design, collection and validation of resources for spoofing, deepfake, and adversarial attack detection using crowdsourced speech. Comput. Speech Lang. 2025, 95, 101825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ańcucki, A. Fastpitch: Parallel text-to-speech with pitch prediction. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP), Toronto, ON, Canada, 6–11 June 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, J.; Kim, S.; Kong, J.; Yoon, S. Glow-tts: A generative flow for text-to-speech via monotonic alignment search. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2020, 33, 8067–8077. [Google Scholar]

- Tatanov, O.; Beliaev, S.; Ginsburg, B. Mixer-TTS: Non-autoregressive, fast and compact text-to-speech model conditioned on language model embeddings. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP), Singapore, 23–27 May 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Vainer, J.; Dušek, O. Speedyspeech: Efficient neural speech synthesis. In Proceedings of the Interspeech, Virtual, 25–29 October 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Beliaev, S.; Rebryk, Y.; Ginsburg, B. TalkNet: Fully-convolutional non-autoregressive speech synthesis model. In Proceedings of the Interspeech, Brno, Czech Republic, 30 August–3 September 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Team, S. Silero Models: Pre-Trained Enterprise-Grade STT/TTS Models and Benchmarks. 2021. Available online: https://github.com/snakers4/silero-models (accessed on 22 December 2025).

- Müller, N.M.; Dieckmann, F.; Czempin, P.; Canals, R.; Böttinger, K.; Williams, J. Speech is silver, silence is golden: What do asvspoof-trained models really learn? In Proceedings of the Interspeech, Brno, Czech Republic, 30 August–3 September 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Sahidullah, M.; Shim, H.-j.; Hautamäki, R.G.; Kinnunen, T.H. Shortcut Learning in Binary Classifier Black Boxes: Applications to Voice Anti-Spoofing and Biometrics. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Signal Process. 2025, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Negroni, V.; Salvi, D.; Bestagini, P.; Tubaro, S. Source verification for speech deepfakes. In Proceedings of the Interspeech, Rotterdam, The Netherlands, 17–21 August 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Salvi, D.; Negroni, V.; Mandelli, S.; Bestagini, P.; Tubaro, S. Phoneme-Level Analysis for Person-of-Interest Speech Deepfake Detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, Honolulu, HI, USA, 19–23 October 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Dhamyal, H.; Ali, A.; Qazi, I.A.; Raza, A.A. Using self attention DNNs to discover phonemic features for audio deep fake detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE Automatic Speech Recognition and Understanding Workshop (ASRU), Cartagena, Colombia, 13–17 December 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Suthokumar, G.; Sriskandaraja, K.; Sethu, V.; Wijenayake, C.; Ambikairajah, E. Phoneme specific modelling and scoring techniques for anti spoofing system. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP), Brighton, UK, 12–17 May 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Nagarsheth, P.; Khoury, E.; Patil, K.; Garland, M. Replay Attack Detection Using DNN for Channel Discrimination. In Proceedings of the Interspeech, Stockholm, Sweden, 20–24 August 2017. [Google Scholar]

| Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |