Spatiotemporal Visual Analysis in Parallel Coordinate Plots (STPCPs): A Case Study of Meteorological Data Analysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Related Work

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Design Rationale

3.2. Data Preliminary Analysis

3.3. Data and Code Availability

3.4. Detailed Design

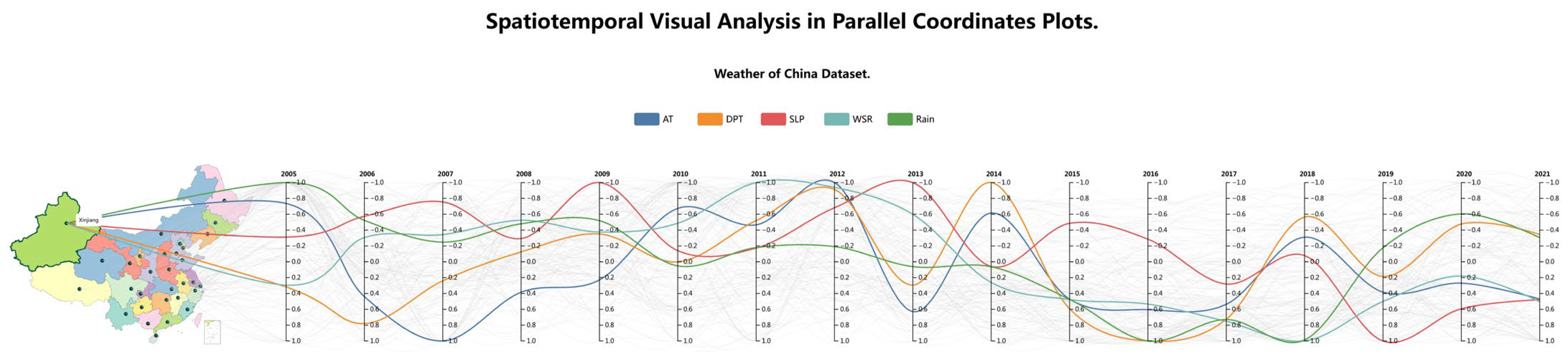

3.4.1. Time Series Visualization in PCP

3.4.2. Map in PCP

3.4.3. Color-Encoded High-Dimensional Attributes

3.4.4. Data Table

3.4.5. Accessible Design Considerations

3.4.6. Prototype Implementation

4. Meteorological Data Exploration

4.1. Case Study

4.2. Comparative Evaluation

4.2.1. Study Design

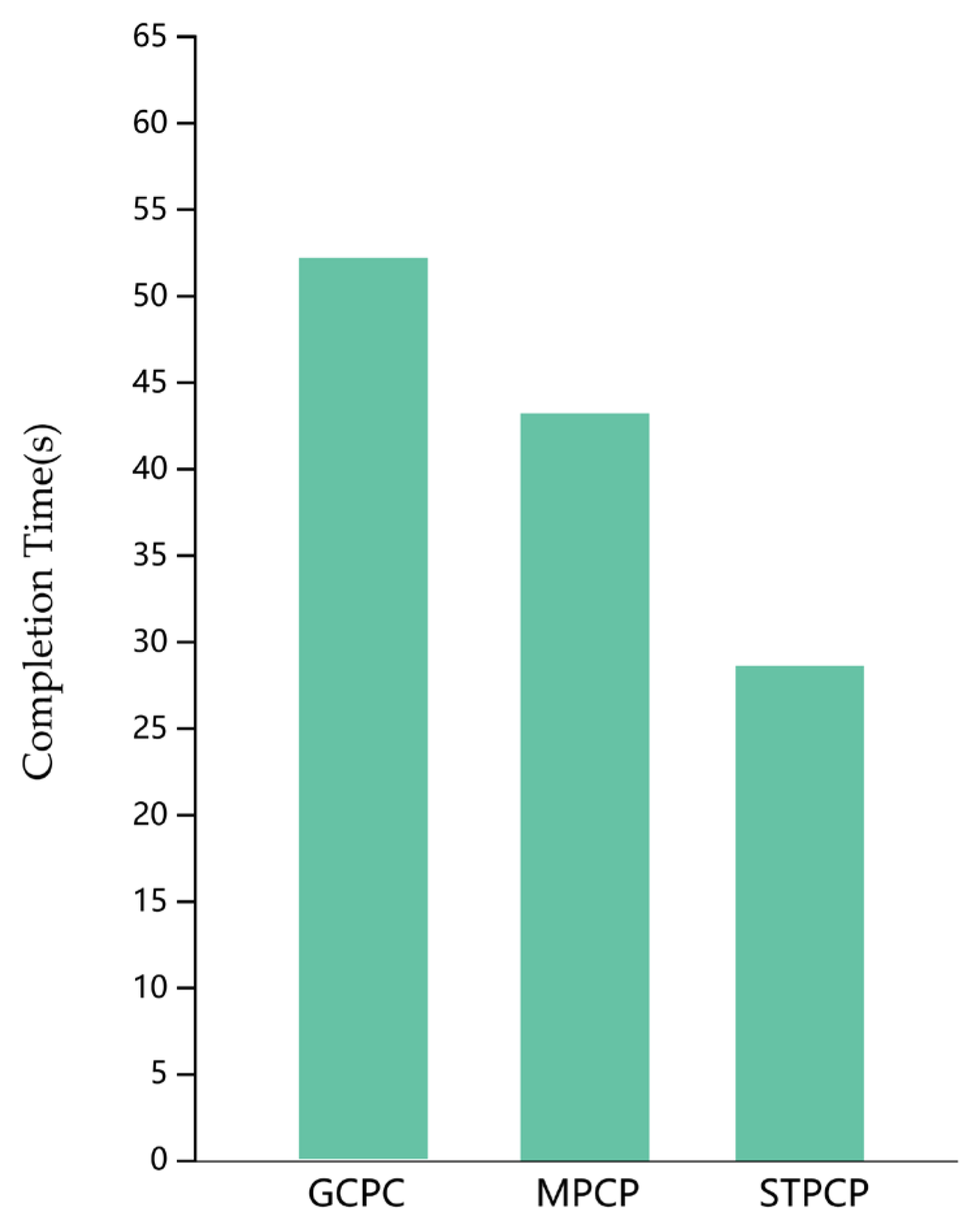

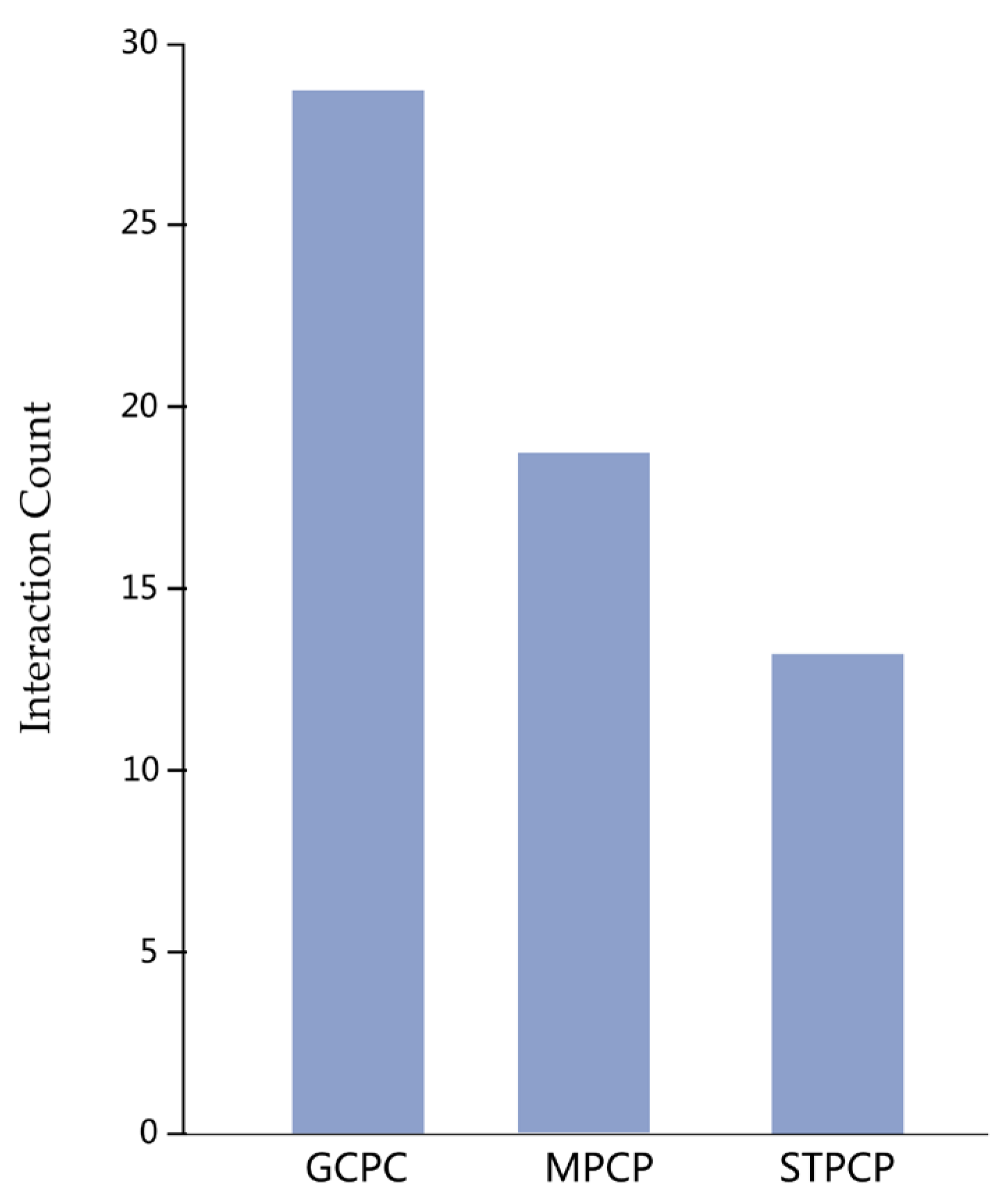

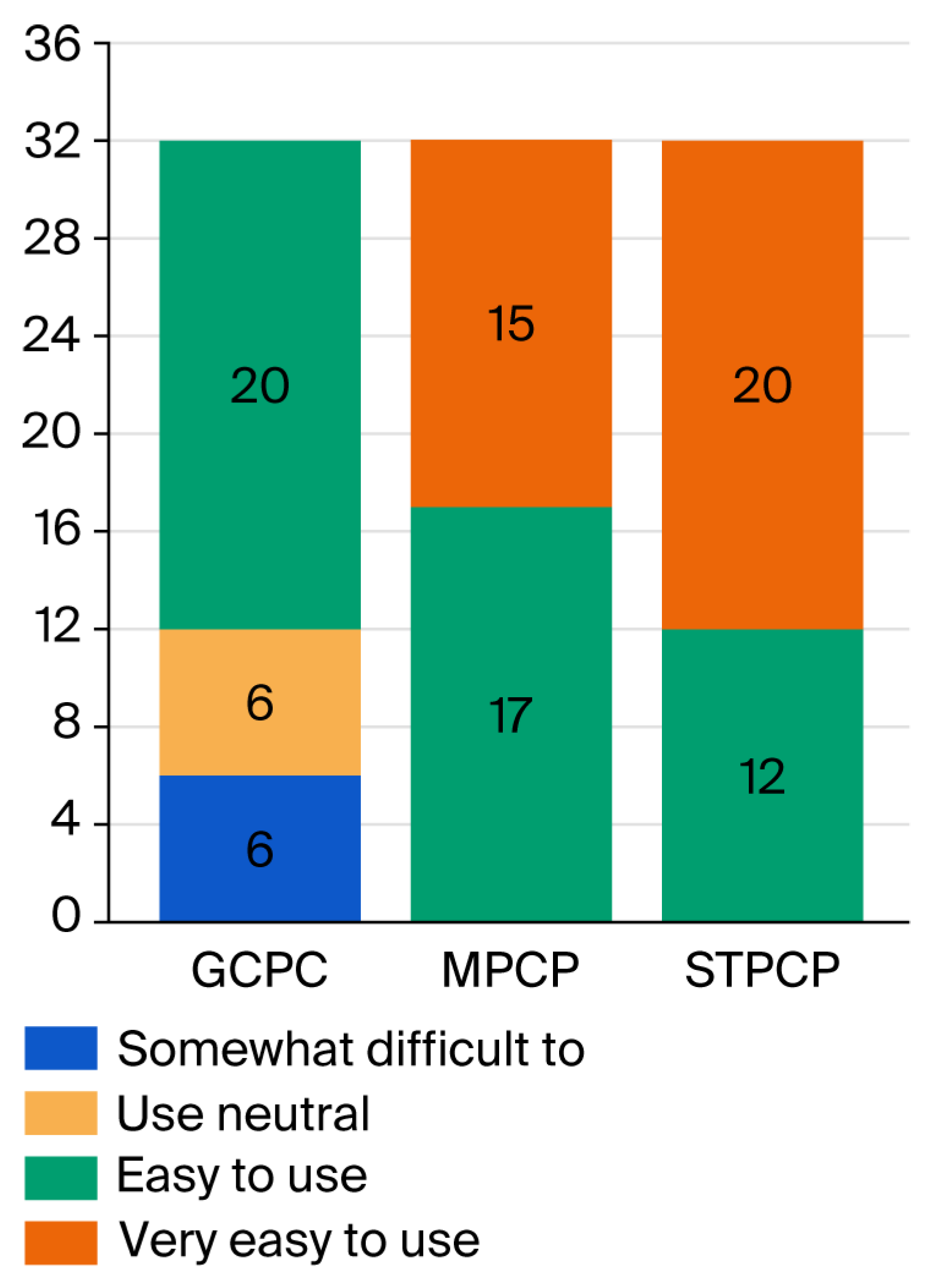

4.2.2. Results and Statistical Analysis

4.2.3. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kolstad, C.D.; Moore, F.C. Estimating the economic impacts of climate change using weather observations. Rev. Environ. Econ. Policy 2020, 14, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neumann, J.E.; Willwerth, J.; Martinich, J.; McFarland, J.; Sarofim, M.C.; Yohe, G. Climate damage functions for estimating the economic impacts of climate change in the United States. Rev. Environ. Econ. Policy 2020, 14, 25–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gelfan, A.; Kalugin, A.; Krylenko, I.; Nasonova, O.; Gusev, Y.; Kovalev, E. Does a successful comprehensive evaluation increase confidence in a hydrological model intended for climate impact assessment? Clim. Change 2020, 163, 1165–1185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Getirana, A.; Biswas, N.K.; Qureshi, A.S.; Rajib, A.; Kumar, S.; Rahman, M.; Biswas, R.K. Avert Bangladesh’s looming water crisis through open science and better data. Nature 2022, 610, 626–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasp, S.; Dueben, P.D.; Scher, S.; Weyn, J.A.; Mouatadid, S.; Thuerey, N. WeatherBench: A benchmark data set for data-driven weather forecasting. J. Adv. Model. Earth Syst. 2020, 12, e2020MS002203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Price, I.; Sanchez-Gonzalez, A.; Alet, F.; Andersson, T.R.; El-Kadi, A.; Masters, D.; Ewalds, T.; Stott, J.; Mohamed, S.; Battaglia, P. Probabilistic weather forecasting with machine learning. Nature 2024, 637, 84–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Masson, V.; Heldens, W.; Bocher, E.; Bonhomme, M.; Bucher, B.; Burmeister, C.; de Munck, C.; Esch, T.; Hidalgo, J.; Kanani-Sühring, F. City-descriptive input data for urban climate models: Model requirements, data sources and challenges. Urban Clim. 2020, 31, 100536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neofytou, H.; Nikas, A.; Doukas, H. Sustainable energy transition readiness: A multicriteria assessment index. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2020, 131, 109988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayawi, K.; Shahriar, S.; Hacid, H. Climate Data Imputation and Quality Improvement Using Satellite Data. J. Data Sci. Intell. Syst. 2024, 3, 87–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atzmueller, M.; Fürnkranz, J.; Kliegr, T.; Schmid, U. Explainable and interpretable machine learning and data mining. Data Min. Knowl. Discov. 2024, 38, 2571–2595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrienko, G.; Andrienko, N.; Demsar, U.; Dransch, D.; Dykes, J.; Fabrikant, S.I.; Jern, M.; Kraak, M.-J.; Schumann, H.; Tominski, C. Space, time and visual analytics. Int. J. Geogr. Inf. Sci. 2010, 24, 1577–1600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, J.C. Coordinated multiple views for exploratory geovisualization. In Geographic Visualization: Concepts, Tools and Applications; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2008; pp. 25–48. [Google Scholar]

- Donoho, D.L. High-dimensional data analysis: The curses and blessings of dimensionality. AMS Math Chall. Lect. 2000, 1, 32. [Google Scholar]

- Kerkad, A.; Gouri, R. Meta-visualization framework for spatiotemporal analytics: From data generation to advanced visualization on maps. Inf. Vis. 2025, 14738716251349509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shneiderman, B. The eyes have it: A task by data type taxonomy for information visualizations. In The Craft of Information Visualization; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2003; pp. 364–371. [Google Scholar]

- Inselberg, A. The plane with parallel coordinates. Vis. Comput. 1985, 1, 69–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vali, Z.S.; Rastegar, H. Parallel coordinates plot: A visual examination of data structures in exploratory data analysis. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. Res. 2024, 11, 201–209. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, S.; Jeong, S.; Woo, I.; Jang, Y.; Maciejewski, R.; Ebert, D.S. Data flow analysis and visualization for spatiotemporal statistical data without trajectory information. IEEE Trans. Vis. Comput. Graph. 2017, 24, 1287–1300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jern, M.; Åström, T.; Johansson, S. In GeoAnalytics tools applied to large geospatial datasets. In Proceedings of the 2008 12th International Conference Information Visualisation, London, UK, 9–11 July 2008; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2008; pp. 362–372. [Google Scholar]

- El Meseery, M.; Hoeber, O. Geo-Coordinated Parallel Coordinates (GCPC): Field trial studies of environmental data analysis. Vis. Inform. 2018, 2, 111–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, X.; Xiao, H.; Guo, H.; Guo, P.; Kendall, W.; Huang, J.; Zhang, Y. Scalable multi-variate analytics of seismic and satellite-based observational data. IEEE Trans. Vis. Comput. Graph. 2010, 16, 1413–1420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johansson, S.; Jern, M. In GeoAnalytics visual inquiry and filtering tools in parallel coordinates plots. In Proceedings of the 15th Annual ACM International Symposium on Advances in Geographic Information Systems, Seattle, WA, USA, 7–9 November 2007; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Dertinger, S.D.; Briggs, E.; Hussien, Y.; Bryce, S.M.; Avlasevich, S.L.; Conrad, A.; Johnson, G.E.; Williams, A.; Bemis, J.C. Visualization strategies to aid interpretation of high-dimensional genotoxicity data. Environ. Mol. Mutagen. 2024, 65, 156–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vieira, A.P.S.B.; João, R.S.; Romani, L.A.; Ribeiro, M.X. The ST-Vis Tool for SpatioTemporal Visualization. In Information Technology-New Generations; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2018; pp. 577–587. [Google Scholar]

- Jeon, H.; Aupetit, M.; Lee, S.; Ko, K.; Kim, Y.; Quadri, G.J.; Seo, J. Distortion-aware Brushing for Reliable Cluster Analysis in Multidimensional Projections. IEEE Trans. Vis. Comput. Graph. 2025, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vahldiek, K.; Klawonn, F. Cluster-centered visualization techniques for fuzzy clustering results to judge single clusters. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bittner, O.; Zejdlik, J.; Burian, J.; Vozenilek, V. Exploring unconventional 3D geovisualization methods for land suitability assessment: A case study of Jihlava City. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2025, 14, 269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, D.; Chen, J.; MacEachren, A.M.; Liao, K. A visualization system for space-time and multivariate patterns (vis-stamp). IEEE Trans. Vis. Comput. Graph. 2006, 12, 1461–1474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, J.; Wan, G.; Jia, Y.; Liu, W.; Xie, Z.; Su, Z.; Li, C.; Peng, S. Map-in-Parallel-Coordinates Plot (MPCP): Field Trial Studies of High-Dimensional Geographical Data Analysis. Electronics 2023, 12, 2062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thijssen, J.; Tian, Z.; Telea, A. Interactive tools for explaining multidimensional projections for high-dimensional tabular data. Comput. Graph. 2024, 122, 103987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okabe, M.; Ito, K. Color Universal Design (CUD)—How to Make Figures and Presentations That Are Friendly to Colorblind People. Available online: https://www.scribd.com/presentation/35372210/Color-Blind (accessed on 10 December 2025).

- Bostock, M.; Ogievetsky, V.; Heer, J. D3 data-driven documents. IEEE Trans. Vis. Comput. Graph. 2011, 17, 2301–2309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pande, A.K. jqWidgets Framework. In jQuery 2 Recipes; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2014; pp. 473–542. [Google Scholar]

- Joshi, A.; Kale, S.; Chandel, S.; Pal, D.K. Likert scale: Explored and explained. Br. J. Appl. Sci. Technol. 2015, 7, 396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanca, M.J.; Arnau, J.; García-Castro, F.J.; Alarcón, R.; Bono, R. Non-normal Data in Repeated Measures ANOVA: Impact on Type I Error and Power. Psicothema 2023, 35, 21–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naganaidu, D.; Khalid, Z.M. ANOVA Assisted Variable Selection in High-dimensional Multicategory Response Data. Statistics 2023, 11, 92–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Zhou, L.; Chen, L.; He, S.; Weiskopf, D.; Wang, Y. Angle-uniform parallel coordinates. Comput. Vis. Media 2023, 9, 495–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohse, B.; Schneider, C. Exploration of High-Dimensional Performance Spaces via Clustering. IFAC-PapersOnLine 2025, 59, 421–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meka, L. Line Perception in Parallel Coordinates Under Different Aspect Ratios. Master’s Thesis, Technische Universität Wien, Vienna, Austria, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, Q.; Lu, T.; Guo, S.; Ma, X.; Yang, Y. CompositingVis: Exploring interactions for creating composite visualizations in immersive environments. IEEE Trans. Vis. Comput. Graph. 2025, 31, 591–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variable Name | Variable Value | Sample Size | Mean Value | Standard Deviation | Variance Test | Welch’s Test of Variance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Response time | GCPC | 32 | 52.44 | 5.829 | F = 124.676 p = 0.000 *** | F = 124.347 p = 0.000 *** |

| MPCP | 32 | 44.588 | 5.794 | |||

| STPCP | 32 | 29.984 | 5.696 | |||

| Total | 96 | 42.337 | 10.96 |

| Comparison | Mean Difference | Standard Error | 95% Simultaneous Confidence Interval | Adjusted p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MPCP-GCPC | −7.852 | 1.445 | [−11.30, −4.40] | <0.001 |

| STPCP-GCPC | −22.456 | 1.445 | [−25.90, −19.01] | <0.001 |

| STPCP-MPCP | −14.604 | 1.445 | [−18.05, −11.16] | <0.001 |

| Variable Name | Variable Value | Sample Size | Mean Value | Standard Deviation | Variance Test | Welch’s Test of Variance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Count | GCPC | 32 | 27.781 | 1.773 | F = 392.87 p = 0.000 *** | F = 533.452 p = 0.000 *** |

| MPCP | 32 | 19.094 | 2.668 | |||

| STPCP | 32 | 12.781 | 1.896 | |||

| Total | 96 | 19.885 | 6.537 |

| Comparison | Mean Difference | Standard Error | 95% Simultaneous Confidence Interval | Adjusted p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GCPC-MPCP | 8.687 | 0.537 | [7.407, 9.967] | <0.001 |

| GCPC-STPCP | 15.000 | 0.537 | [13.720, 16.280] | <0.001 |

| MPCP-STPCP | 6.313 | 0.537 | [5.033, 7.593] | <0.001 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Liu, J.; Feng, S.; Li, N.; Yuan, L. Spatiotemporal Visual Analysis in Parallel Coordinate Plots (STPCPs): A Case Study of Meteorological Data Analysis. Electronics 2026, 15, 168. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics15010168

Liu J, Feng S, Li N, Yuan L. Spatiotemporal Visual Analysis in Parallel Coordinate Plots (STPCPs): A Case Study of Meteorological Data Analysis. Electronics. 2026; 15(1):168. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics15010168

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiu, Jia, Songjiang Feng, Na Li, and Lihuan Yuan. 2026. "Spatiotemporal Visual Analysis in Parallel Coordinate Plots (STPCPs): A Case Study of Meteorological Data Analysis" Electronics 15, no. 1: 168. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics15010168

APA StyleLiu, J., Feng, S., Li, N., & Yuan, L. (2026). Spatiotemporal Visual Analysis in Parallel Coordinate Plots (STPCPs): A Case Study of Meteorological Data Analysis. Electronics, 15(1), 168. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics15010168