Research on a Dual-Trust Selfish Node Detection Algorithm Based on Behavioral and Social Characteristics in VANETs

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Related Work

2.1. Reputation- and Credit-Based Methods

2.2. Trust-Based Methods and Hybrid Methods

2.3. Socially-Aware Methods

2.4. Machine Learning-Based Methods

3. System Model

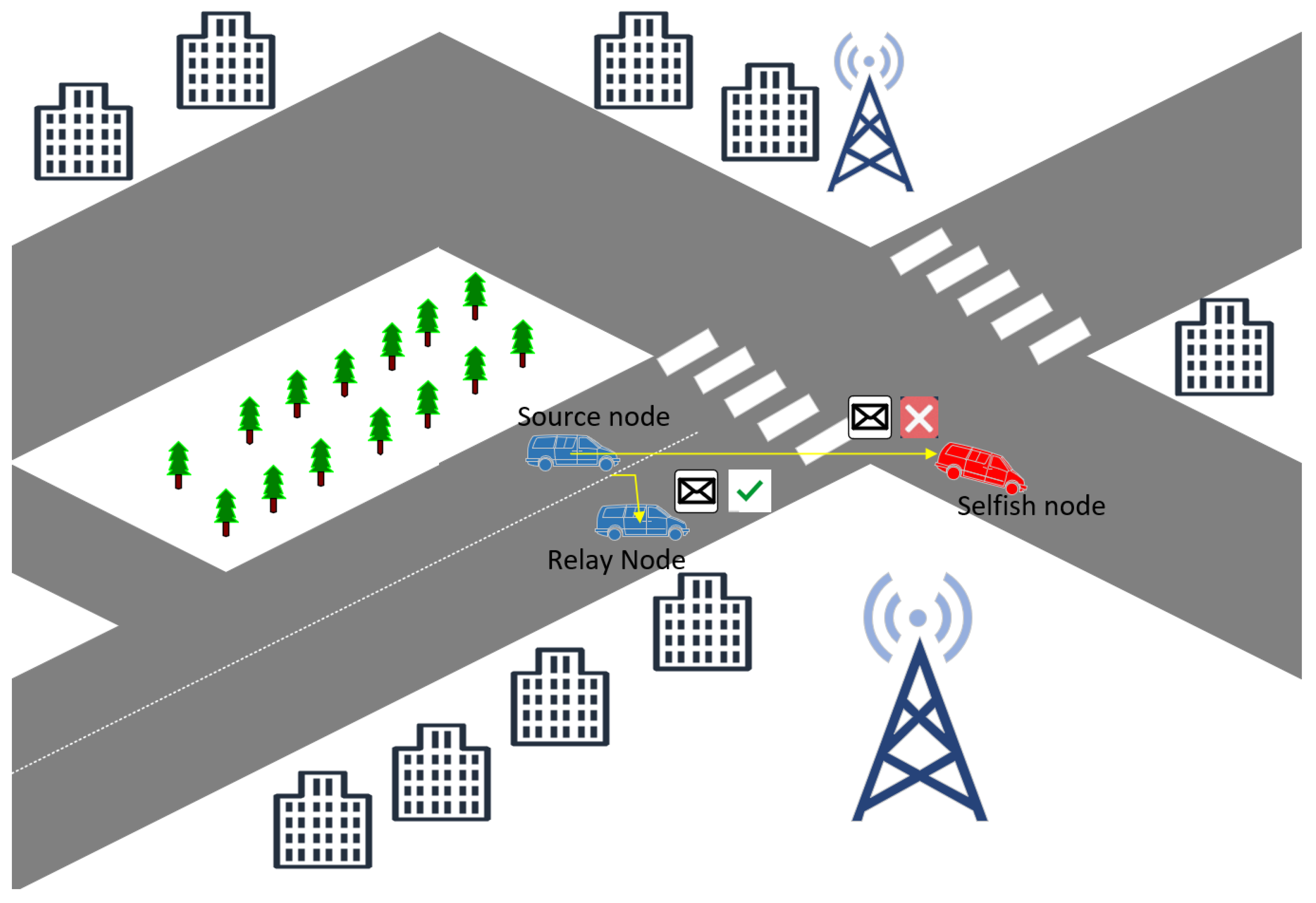

3.1. Network Model

- Cooperative Node: A cooperative node actively participates in network communication and correctly receives messages, maintaining a consistently high forwarding rate and trust level.

- Selfish Node: If a relay node is marked as selfish, it will not serve as the final recipient of messages and exhibits the following behaviors:

- Refuses messages from any other nodes;

- Discards received messages;

- Does not participate in forwarding or relaying;

- Non-Malicious Assumption: Unlike malicious nodes, selfish nodes do not actively tamper with the content of received or sent messages, nor do they forge or inject false information. Their behavior is limited to selfishness in communication.

- Energy-saving Equivalence Assumption: In practice, VANET nodes may enter sleep or inactive modes to conserve energy. As reviewed by Gu Rehman et al. [28], this behavior has an effect equivalent to selfish behavior during vehicle operation. Therefore, for the sake of theoretical and experimental analysis, such energy-saving behavior is considered equivalent to selfish behavior to maintain model consistency and completeness.

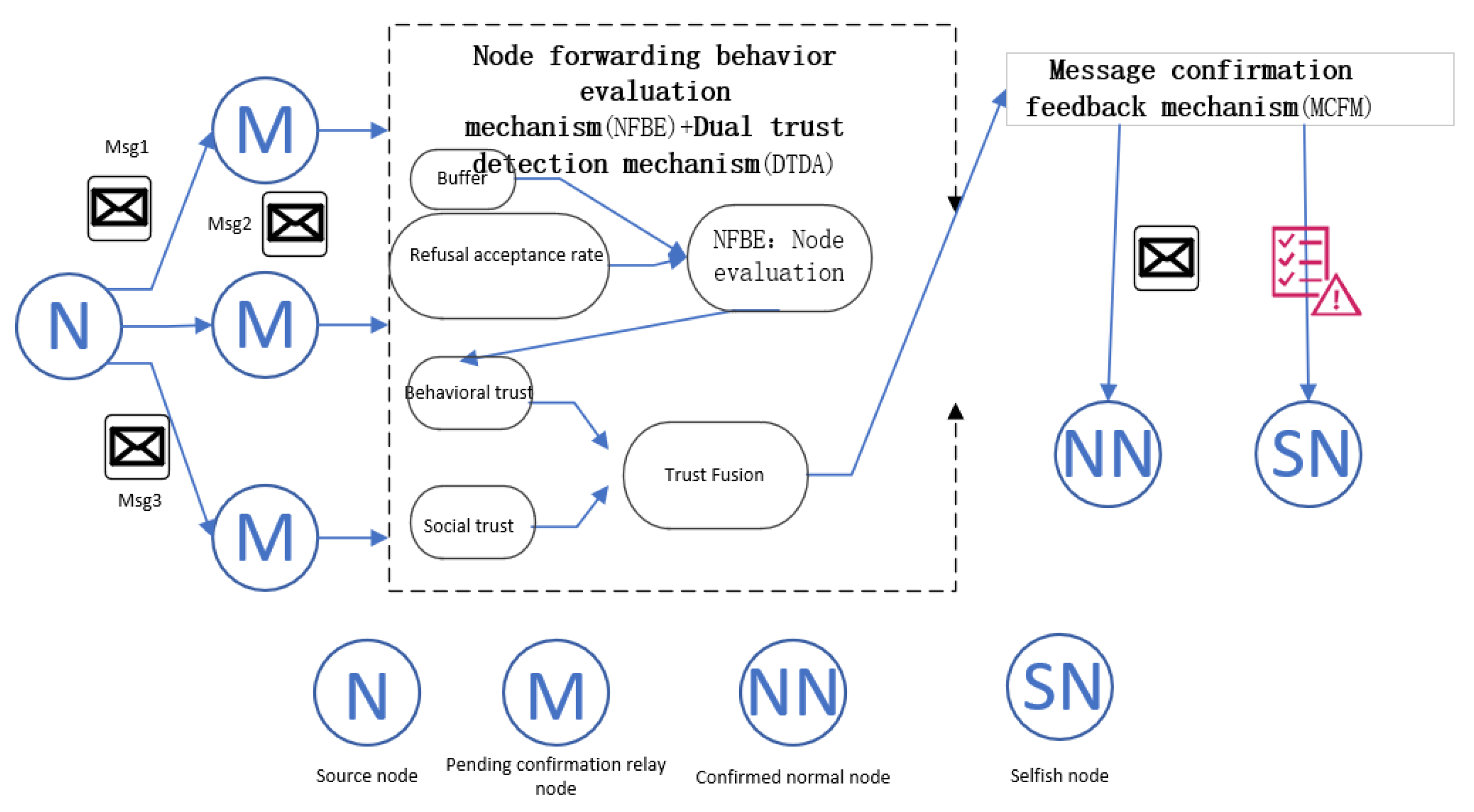

3.2. Trust Modeling

3.2.1. Behavior Trust

3.2.2. Social Trust

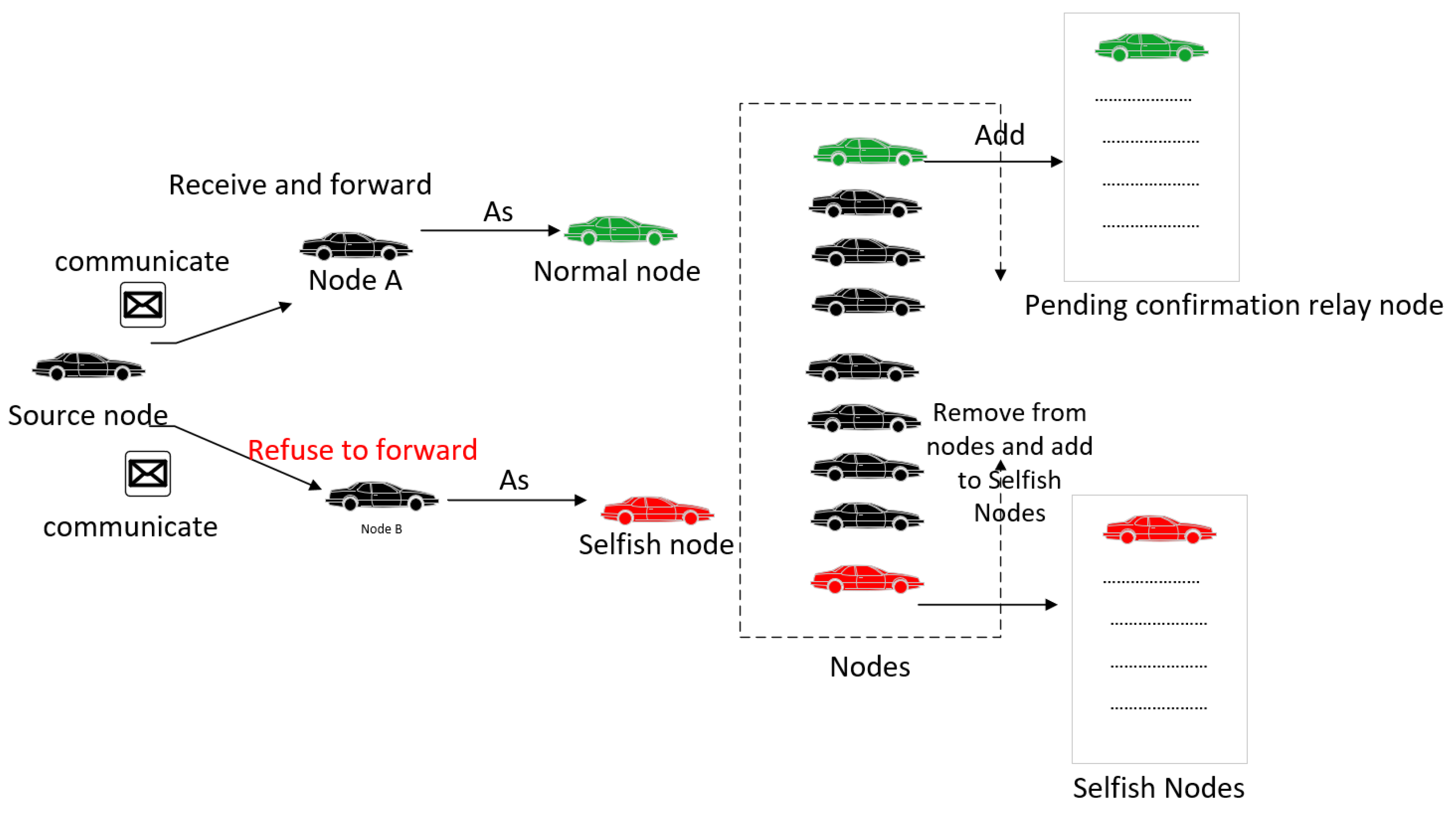

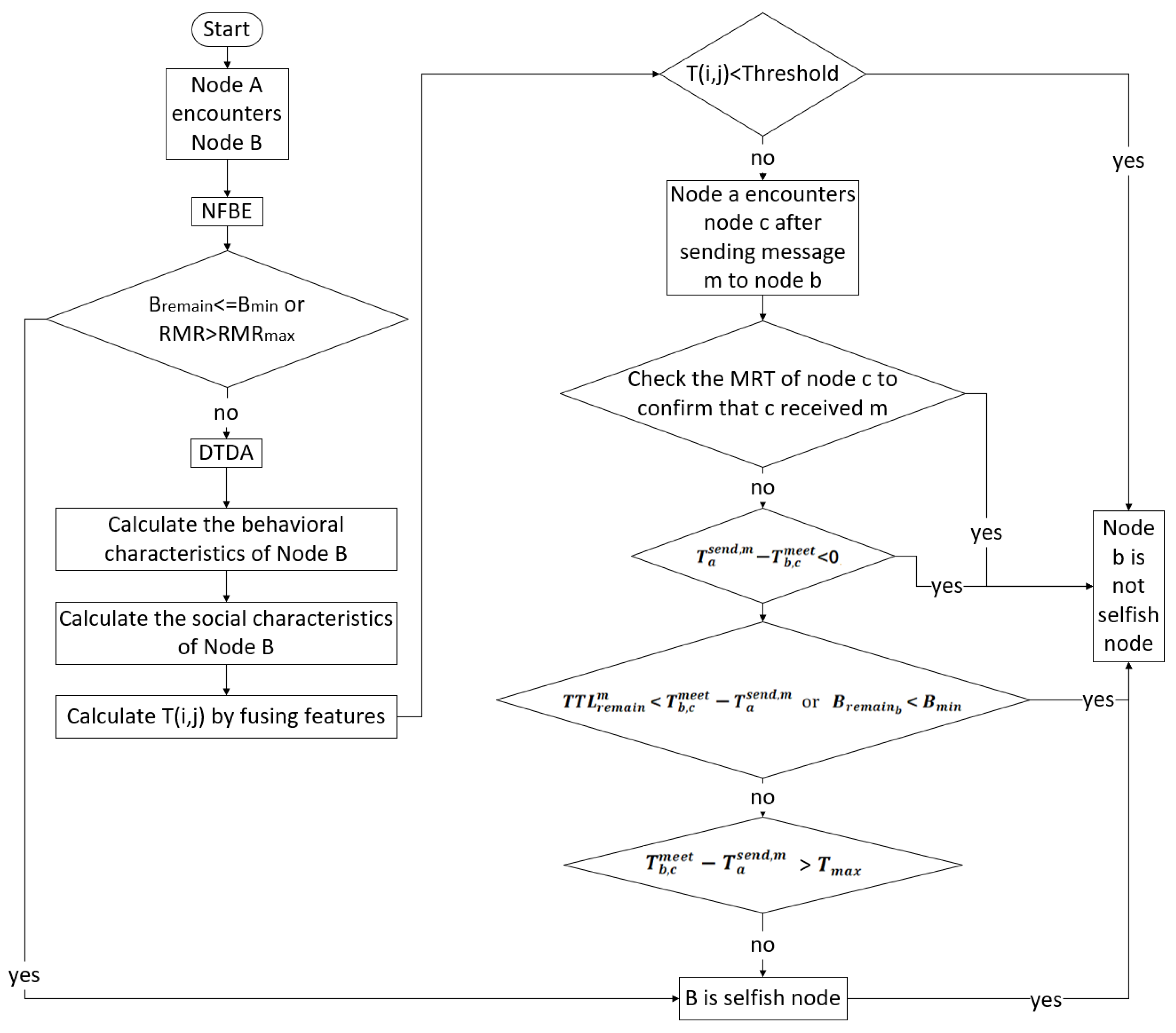

4. Dual-Trust-Based Selfish Node Detection Algorithm (DTSDA) Based on Behavioral and Social Features

4.1. Algorithm Design Approach

- Resource-Aware Preliminary Filtering (NFBE): Existing models often misjudge nodes as selfish when they are merely physically constrained. DTSDA first evaluates a node’s remaining buffer and message refusal rate to differentiate between “objective inability” and “subjective selfishness”. This initial stage prevents the unnecessary consumption of computational resources on nodes that are physically unavailable.

- While earlier hybrid schemes combine behavior and social features, they often fail to capture the transient nature of VANETs. DTSDA introduces an exponentially decayed time-weighting mechanism to reflect the dynamic evolution of behavioral trust. Furthermore, it integrates a distance-aware social trust model using a Euclidean decay factor to ensure that social stability is grounded in physical proximity.

- To address potential false negatives from the first two stages, a message acknowledgment feedback mechanism provides the ultimate verification of a node’s forwarding commitment.

4.2. Node Forwarding Behavior Evaluation Mechanism (NFBE)

4.2.1. Evaluation of Node Remaining Buffer

4.2.2. Message Refusal Rate of a Node

- If , the node’s remaining buffer is too low to support further forwarding operations. To conserve its own resources, the node exhibits selfish behavior by refusing to forward messages. In this case, the node is immediately marked as selfish, and no further evaluation is required, as its buffer limitation prevents it from participating in subsequent message forwarding or receiving.

- If , the node has sufficient remaining buffer and behaves as a normal node, willing to assist other nodes in forwarding messages. In this case, the Rejected Message Rate (RMR) is used to further assess the node’s selfishness.

- If (the maximum allowed message refusal rate), the node’s refusal rate is excessively high. A high RMR indicates that the node is likely to continue refusing messages due to various reasons, and therefore, the node is marked as selfish.

- If , the node may refuse messages occasionally for certain reasons, but this alone does not prove that it is selfish. In this case, the NFBE mechanism cannot conclusively determine the node’s selfishness, and the node will be further evaluated using the Dual-Trust Detection Algorithm (DTDA) for a more in-depth assessment.

4.3. Dual-Trust Detection Mechanism Algorithm (DTDA)

4.3.1. Behavioral Features

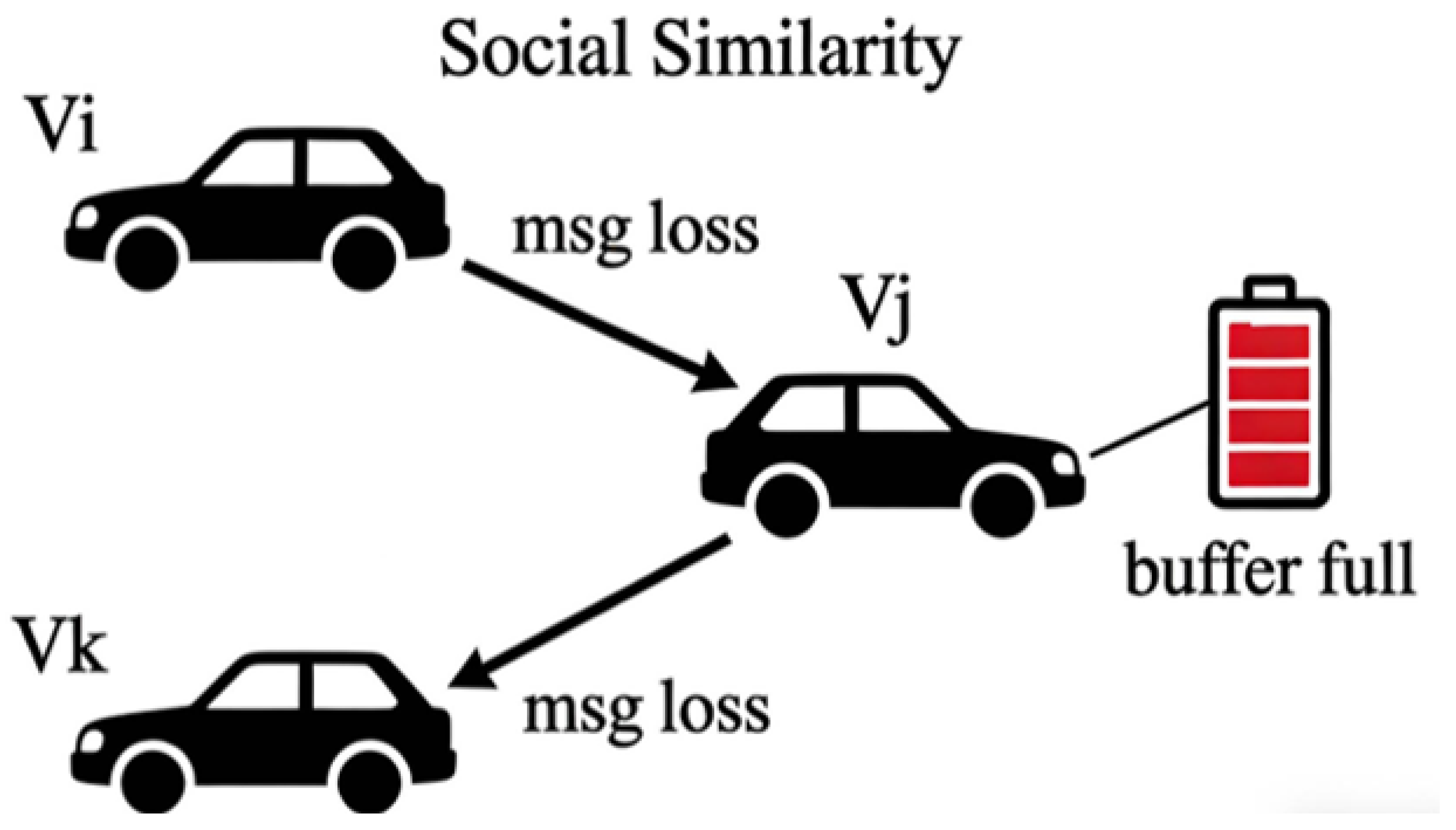

4.3.2. Social Features

- Contact DensityContact Density is an indicator used to measure the contact frequency and closeness between nodes in VANETs. It describes the number of encounters between two or more nodes within a unit time, thereby reflecting the strength of their social relationship and the potential for information propagation. In this study, the contact density represents the closeness between nodes i and j. It is computed as shown in Equation (9) and subsequently normalized to facilitate further calculations.Here, msgTtl denotes the total lifetime of a message, and C(i,j,msgTtl) represents the number of contacts between nodes i and j within the message lifetime. The encounter records of nodes i and j are stored in a contact hash table, and the number of encounters is calculated by iterating through the hash table. Contact density reflects node activity; a higher contact density indicates that the node remains active within the communication range and possesses higher trustworthiness.

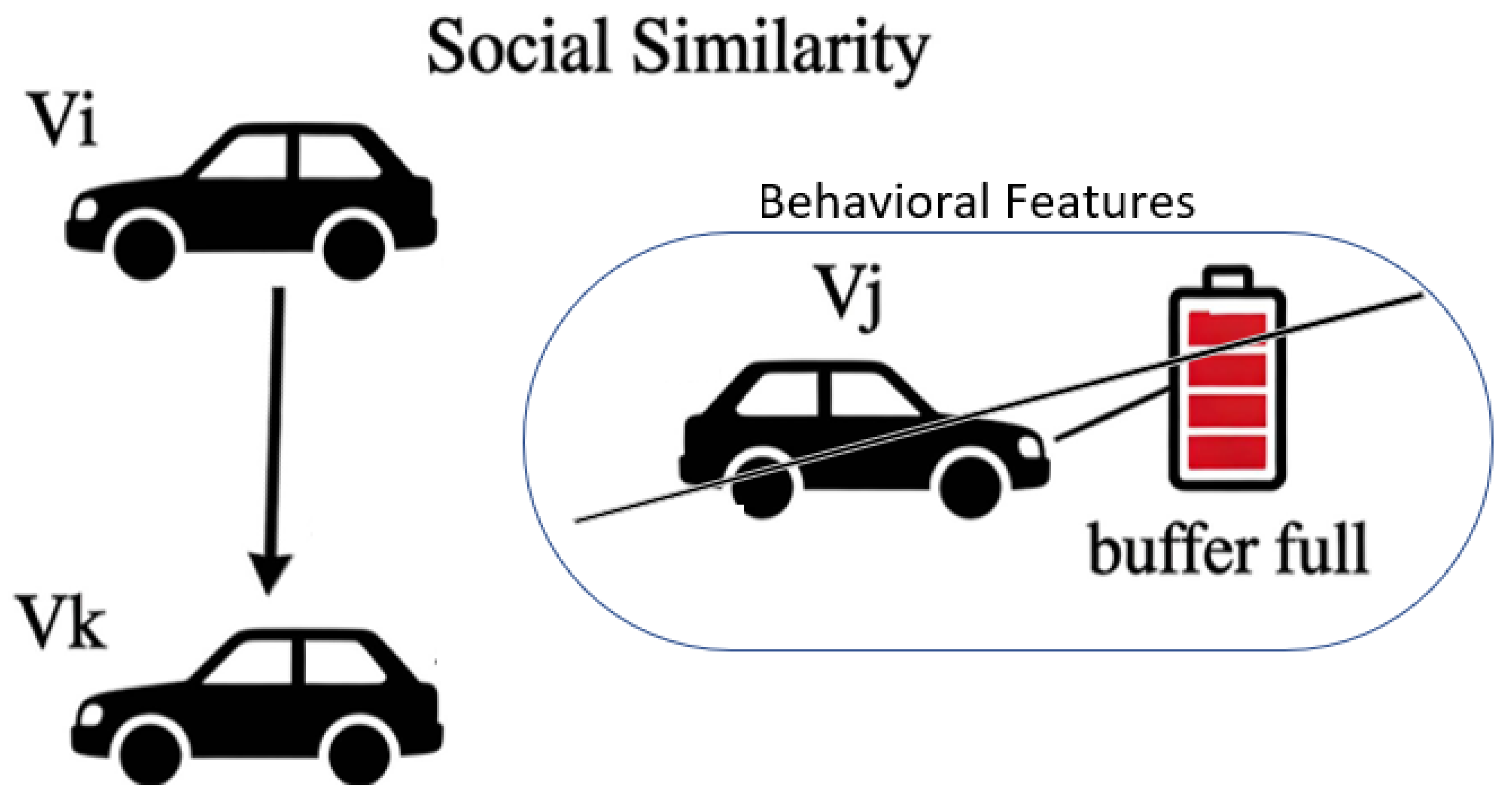

- Social SimilaritySocial Similarity is an indicator used to measure the degree of similarity between two individuals or nodes in a VANET, describing how alike the two nodes are in terms of interests, behaviors, and other attributes. In this study, the social similarity represents the similarity between nodes i and j. Its computation is given in Equation (11).Here, represents the number of common neighbors between nodes i and j, where and denote the total number of neighbors of nodes i and j, respectively.

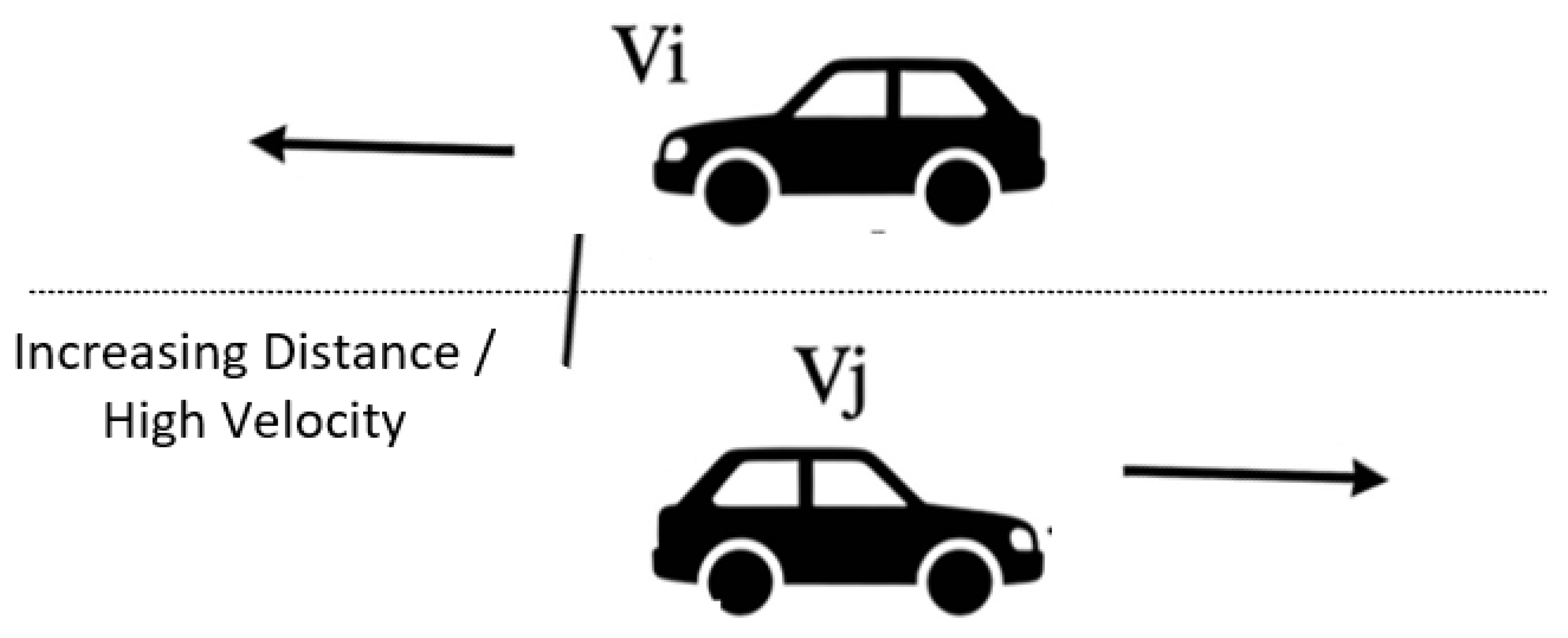

- Distance DecayUnlike traditional behavior-based trust models, social feature modeling focuses on the social relationships between nodes rather than individual behaviors. In addition to social similarity and contact density, a distance-aware concept is introduced. As the distance between vehicles increases, the frequency of information exchange decreases, resulting in an exponential decay of trust. The corresponding formula is given in Equation (12) and (13).

4.3.3. Trust Fusion

4.3.4. Scenario-Level Analysis of Dual-Trust Necessity

- Scenario A: Socially Connected but Physically Constrained (The Need for Behavioral Trust). Imagine a vehicle that belongs to the same commuter platoon as the source node , as shown in Figure 5. Due to their frequent encounters and shared routes, possesses high social similarity and contact density. However, currently suffers from a depleted buffer () or bandwidth congestion. A model relying primarily on social ties would wrongly select as a reliable relay, resulting in message loss. In DTSDA, the Behavioral Trust component (NFBE and RMR assessment) identifies this physical limitation and bypasses the node, ensuring communication reliability. As shown in Figure 6, because the behavioral feature is removed as a selfish node, directly passes the message to , and the message is not lost.

- Scenario B: Behaviorally Active but Socially Unstable (The Need for Social Trust). Consider a passing vehicle from an opposite lane that exhibits a high instantaneous forwarding rate, leading to a high behavioral trust score. However, has no common neighbors with the target and its physical distance from the source is increasing rapidly. Relying solely on behavioral metrics might lead the algorithm to select as a relay, but the link will soon break due to the lack of social stability, as shown in Figure 7. DTSDA’s Social Trust incorporates Euclidean distance decay , which penalizes the trust score of such transient nodes and favors more stable, socially-proximate neighbors.

4.4. Message Acknowledgment Feedback Mechanism (MAFM)

- If message m is found in node c’s MRT, it indicates that node b has successfully forwarded the message. Therefore, node b is not selfish.

- If message m is not found in node c’s MRT, node c’s NMT is checked to determine whether it has encountered node b. If no encounter occurred, it is currently not possible to determine whether node b is selfish. If an encounter did occur, the timestamps from node a’s MST and are considered. If < 0, it indicates that node a had not yet sent message m at the time of the encounter, so the selfishness of node b cannot be judged. Next, the remaining message lifetime and node b’s buffer are examined. If < or < , it indicates that the message has expired or node b lacks sufficient resources. Finally, if exceeds the maximum time threshold , it implies that a long time passed between node b receiving the message and encountering node c; otherwise, node b is determined to be selfish.

5. Simulation Analysis

5.1. Simulation Parameters and Environment Settings

5.2. Simulation Scenarios and Performance Parameters

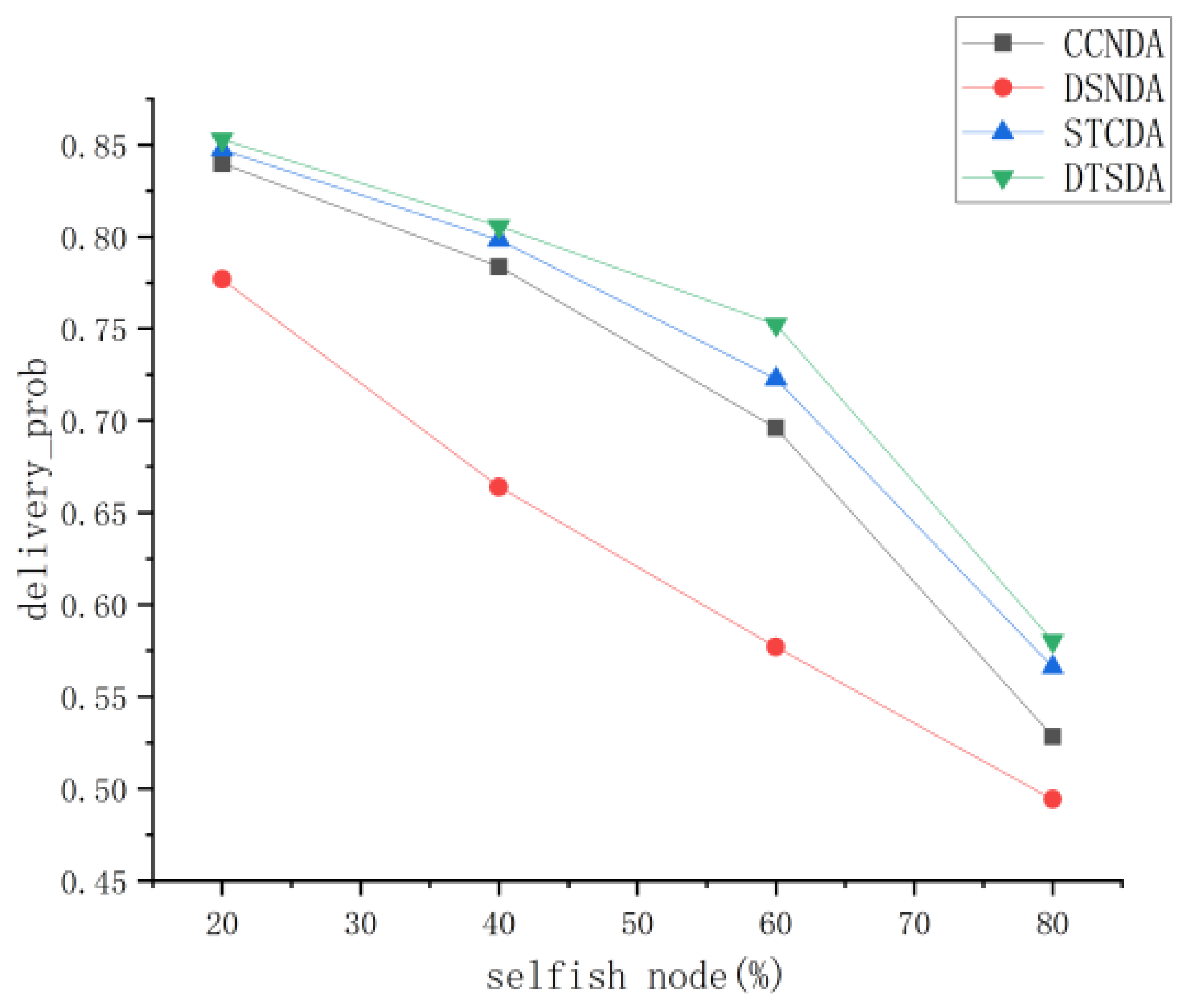

- Comprehensive Node Detection Algorithm (CCSDA) [33]:This scheme evaluates node performance from the perspectives of communication satisfaction and energy trust to determine node attributes.

- Data Service Node Detection Algorithm (DSNDA) [34]:DSNDA is a model designed to detect data service nodes by assessing their message forwarding capability and message processing mechanism to determine node properties.

- Social Trust Confirmation-Based Selfish Node Detection Algorithm (STCDA) [17]:STCDA determines the selfishness of nodes efficiently and accurately by calculating both individual and social benefits.

5.3. Simulation Results and Performance Analysis

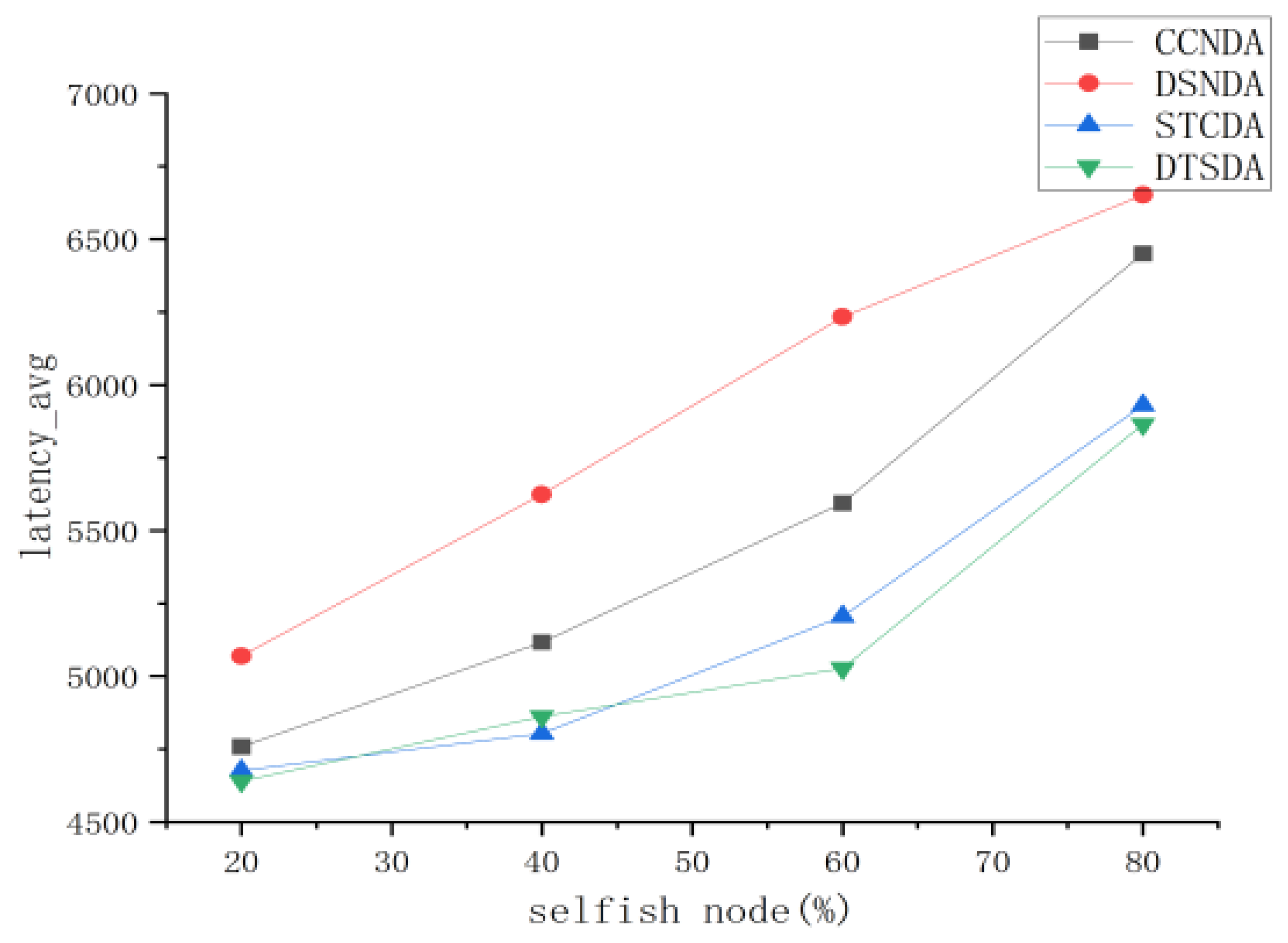

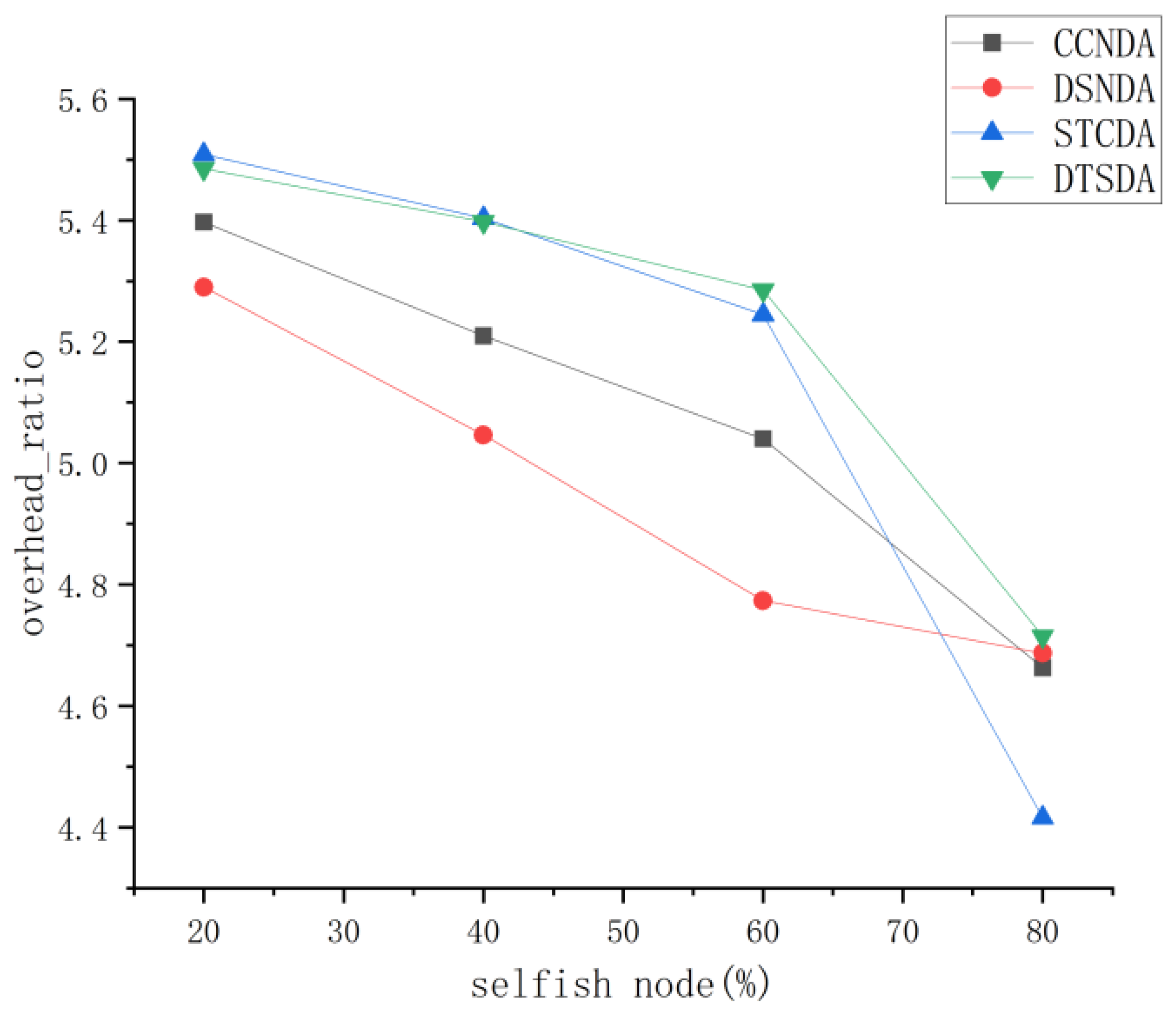

5.3.1. Performance Comparison and Analysis of Various Algorithms Under Different Percentages of Selfish Nodes

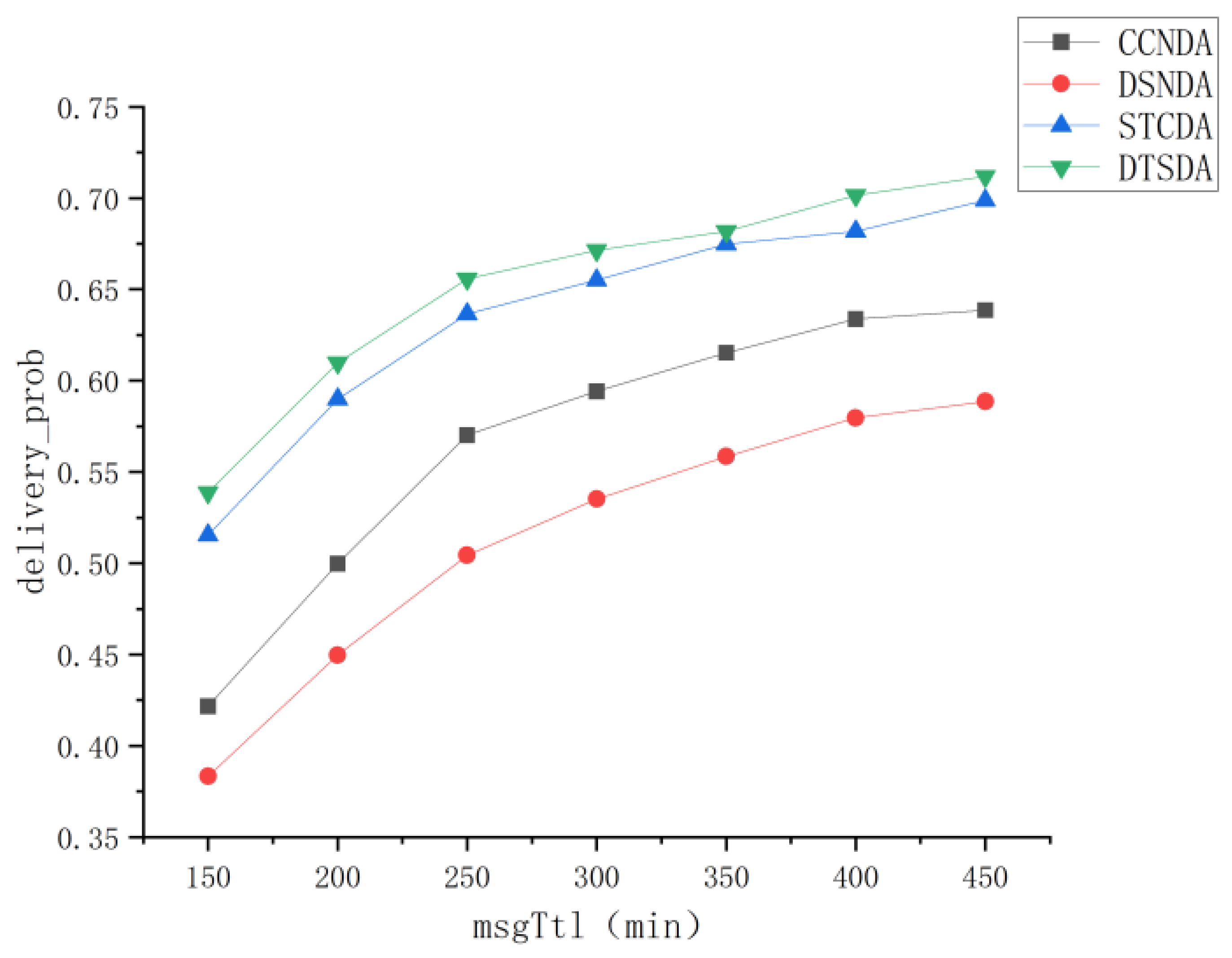

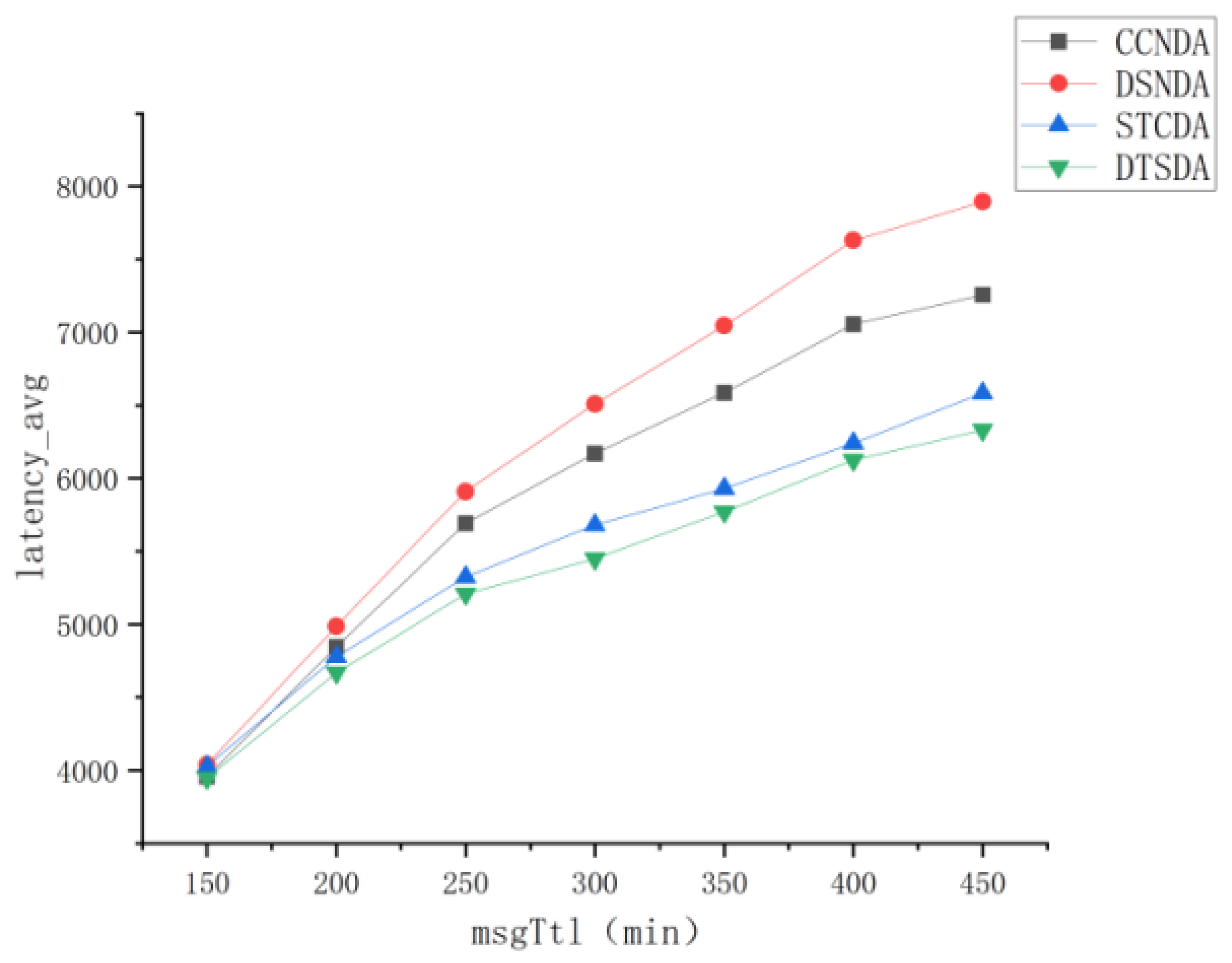

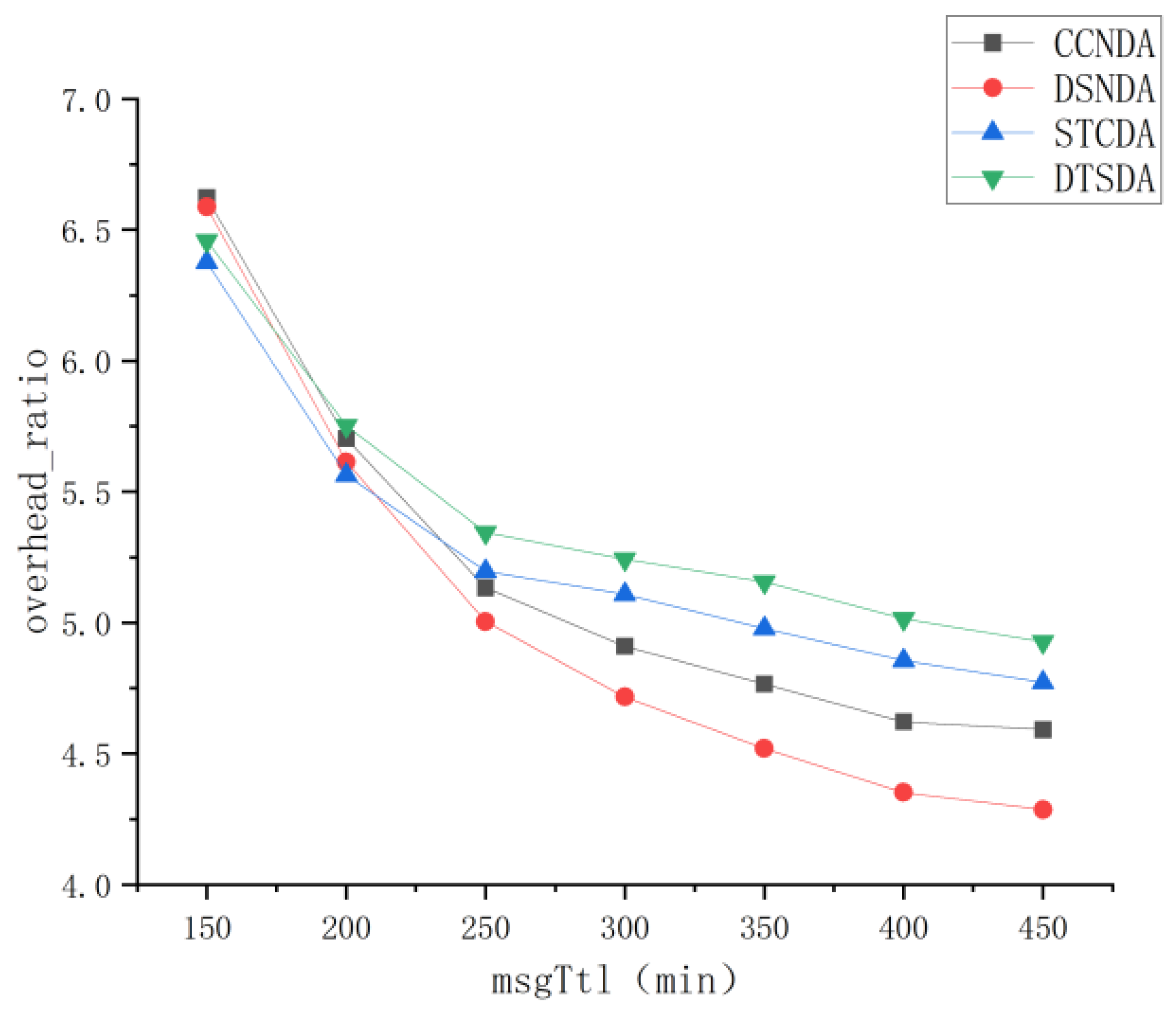

5.3.2. Performance Comparison and Analysis of Various Algorithms Under Different Message Survival Times

6. Summary

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Pal, S. Evaluating the Impact of Network Loads and Message Size on Mobile Opportunistic Networks in Challenged Environments. J. Netw. Comput. Appl. 2017, 81, 47–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahab, S.; Agarwal, P.; Mufti, T.; Obaid, A.J. SIoT (Social Internet of Things): A Review. ICT Anal. Appl. 2022, 289–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheikh, M.S.; Liang, J.; Wang, W. A survey of security services, attacks, and applications for vehicular ad hoc networks (VANETs). Sensors 2019, 19, 3589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, G.; Zhang, Y.; Li, X. Attention-based highway safety planner for autonomous driving via deep reinforcement learning. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2023, 73, 162–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, H.; Wang, M.; Shen, J.; He, D.; Kumar, N. Blockchain-Assisted Conditional Anonymous Authentication and Adaptive Tree-Based Group Key Agreement for VANETs. IEEE Trans. Dependable Secur. Comput. 2025, 1–16, early access. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutrala, A.K.; Bagga, P.; Das, A.K.; Kumar, N.; Rodrigues, J.J.P.C. On the Design of Conditional Privacy Preserving Batch Verification-Based Authentication Scheme for Internet of Vehicles Deployment. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2020, 69, 5535–5548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chettibi, S. Combination of HF set and MCDM for stable clustering in VANETs. IET Intell. Transp. Syst. 2020, 14, 190–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkhalidy, M.; Al-Serhan, A.F.; Alsarhan, A.; Igried, B. A new scheme for detecting malicious nodes in vehicular ad hoc networks based on monitoring node behavior. Future Internet 2022, 14, 223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borah, A.; Paranjothi, A. Enhancing VANET Security: An Unsupervised Learning Approach for Mitigating False Information Attacks in VANETs. Electronics 2024, 14, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Che, H.; Duan, Y.; Li, C.; Yu, L. On trust management in vehicular ad hoc networks: A comprehensive review. Front. Internet Things 2022, 1, 995233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arshad, M.; Ullah, Z.; Ahmad, N.; Khalid, M.; Criuckshank, H.; Cao, Y. A survey of local/cooperative-based malicious information detection techniques in VANETs. EURASIP J. Wirel. Commun. Netw. 2018, 2018, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, R.; Lee, J.; Zeadally, S. Trust in VANET: A survey of current solutions and future research opportunities. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2020, 22, 2553–2571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marti, S.; Giuli, T.J.; Lai, K.; Baker, M. Mitigating routing misbehavior in mobile ad hoc networks. In Proceedings of the 6th Annual International Conference on Mobile Computing and Networking, Boston, MA, USA, 6–11 August 2000; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2000; pp. 255–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jedari, B.; Xia, F.; Chen, H.; Das, S.K.; Tolba, A.; AL-Makhadmeh, Z. A social-based watchdog system to detect selfish nodes in opportunistic mobile networks. Future Gener. Comput. Syst. 2019, 92, 777–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nobahary, S.; Babaie, S. A Credit-based Method to Selfish Node Detection in Mobile Ad-hoc Network. Appl. Comput. Syst. 2018, 23, 118–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aslan, M.; Sen, S. A dynamic trust management model for vehicular ad hoc networks. Veh. Commun. 2023, 41, 100608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Rao, Y.; Xiong, Z.; Li, Y.; Zhang, X.; Hou, D.; Lou, Q.; Li, J. Social Trust Confirmation-Based Selfish Node Detection Algorithm in Socially Aware Networks. Electronics 2024, 13, 3797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, N.; Shen, S.; Wu, C.Q.; Yao, J. A hybrid trust model based on communication and social trust for vehicular social networks. Int. J. Distrib. Sens. Netw. 2022, 18, 15501329221097588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, E. Blockchain driven trust management for intelligent transportation systems in VANETs. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 39702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasanth, T. SecureTrust-PI: A Privacy-Integrity Trust Management Model for Vehicular Edge-Cloud. Eng. Technol. Appl. Sci. Res. 2025, 15, 30669–30675. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, Z.; Hu, B.; Song, H.; Liu, X. A social-aware routing protocol for two different scenarios in vehicular ad hoc network. In Communications and Networking, Proceedings of the 12th International Conference on Communications and Networking in China, Xi’an, China, 10–12 October 2017; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 563–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sultan, S.; Javaid, Q.; Malik, A.J.; Al-Turjman, F.; Attique, M. Collaborative-trust approach toward malicious node detection in vehicular ad hoc networks. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2022, 24, 7532–7550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarker, O.; Shen, H.; Babar, M.A. Reinforcement learning based neighbour selection for VANET with adaptive trust management. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE 22nd International Conference on Trust, Security and Privacy in Computing and Communications (TrustCom), Exeter, UK, 1–3 November 2023; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2023; pp. 585–594. [Google Scholar]

- Rashid, K.; Saeed, Y.; Ali, A.; Jamil, F.; Alkanhel, R.; Muthanna, A. An adaptive real-time malicious node detection framework using machine learning in vehicular ad hoc networks (VANETs). Sensors 2023, 23, 2594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canh, T.N.; HoangVan, X. Machine learning-based malicious vehicle detection for security threats and attacks in vehicle ad hoc network (VANET) communications. In Proceedings of the 2023 RIVF International Conference on Computing and Communication Technologies (RIVF), Hanoi, Vietnam, 23–25 December 2023; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2023; pp. 206–211. [Google Scholar]

- Jyothi, N.; Patil, R. An optimized deep learning-based trust mechanism in VANET for selfish node detection. Int. J. Pervasive Comput. Commun. 2022, 18, 304–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Youness, N.; Mostafa, A.; Sobh, M.A.; Bahaa, A.M.; Nagaty, K. VeMisNet: Enhanced Feature Engineering for Deep Learning-Based Misbehavior Detection in Vehicular Ad Hoc Networks. J. Sens. Actuator Netw. 2025, 14, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehman, G.-U.; Ghani, A.; Muhammad, S.; Singh, M.; Singh, D. Selfishness in vehicular delay-tolerant networks: A review. Sensors 2020, 20, 3000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutiérrez-Reina, D.; Sharma, V.; You, I.; Toral, S. Dissimilarity metric based on local neighboring information and genetic programming for data dissemination in vehicular ad hoc networks (VANETs). Sensors 2018, 18, 2320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Günay, F.B.; Öztürk, E.; Çavdar, T.; Hanay, Y.S.; Khan, K.u.R. Vehicular ad hoc network (VANET) localization techniques: A survey. Arch. Comput. Methods Eng. 2021, 28, 3001–3033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keranen, A. Opportunistic network environment simulator. In Special Assignment Report, Helsinki University of Technology, Department of Communications and Networking; Helsinki University of Technology: Espoo, Finland, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Spyropoulos, T.; Psounis, K.; Raghavendra, C.S. Spray and wait: An efficient routing scheme for intermittently connected mobile networks. In Proceedings of the 2005 ACM SIGCOMM Workshop on Delay-Tolerant Networking, Philadelphia, PA, USA, 26 August 2005; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2005; pp. 252–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, Z.; Li, X.; Zhang, X.; Deng, M.; Xu, F.; Zhou, B.; Zeng, M. A comprehensive confirmation-based selfish node detection algorithm for socially aware networks. J. Signal Process. Syst. 2023, 95, 1371–1389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, N.; Xinyi, R.; Xiong, Z.; Xu, F.; Zhang, X.; Xu, Q.; Zhao, X.; Ye, C. A diversity-based selfish node detection algorithm for socially aware networking. J. Signal Process. Syst. 2021, 93, 811–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Algorithm Type | Core Detection Mechanism | Time Complexity | Calculation Operation Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| DTSDA | Multi-stage logical/algebraic operations | Simple algebraic formulas, no need for iterative training | |

| ML-based | Deep learning/regression model | or | High-dimensional matrix operations rely on expensive training processes. |

| Blockchain | Distributed ledger/consensus algorithm | High (depends on consensus) | It involves intensive hash calculations and network communication. |

| Parameter | Value | Unit |

|---|---|---|

| Simulation | 12 | hour (h) |

| Number of nodes | 180 | node |

| Simulation area | 4500 × 3400 | square meters (m2) |

| Transmission range | 1000 | KB/s |

| Transmission speed | 10 | meter (m) |

| Mobility model | Shortest Path Map Based Movement | - |

| Buffer size per node | 20 | Megabyte (M) |

| Node speed | 0.5–2.9 | meter/second (m/s) |

| Message interval | 25–35 | s/node |

| Message size | 500–1000 | KB |

| Message lifetime | 5 | hour (h) |

| 0.5 | - |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Wang, W.; Qin, M.; You, L.; Yang, C.; Lou, Q.; Guo, W. Research on a Dual-Trust Selfish Node Detection Algorithm Based on Behavioral and Social Characteristics in VANETs. Electronics 2026, 15, 150. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics15010150

Wang W, Qin M, You L, Yang C, Lou Q, Guo W. Research on a Dual-Trust Selfish Node Detection Algorithm Based on Behavioral and Social Characteristics in VANETs. Electronics. 2026; 15(1):150. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics15010150

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Weihu, Menglong Qin, Lan You, Chunmeng Yang, Qiangqiang Lou, and Wenbo Guo. 2026. "Research on a Dual-Trust Selfish Node Detection Algorithm Based on Behavioral and Social Characteristics in VANETs" Electronics 15, no. 1: 150. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics15010150

APA StyleWang, W., Qin, M., You, L., Yang, C., Lou, Q., & Guo, W. (2026). Research on a Dual-Trust Selfish Node Detection Algorithm Based on Behavioral and Social Characteristics in VANETs. Electronics, 15(1), 150. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics15010150