1. Introduction

Mobility services like Mobility on Demand (MOD) and Mobility as a Service (MaaS) rely on complex data standards, protocols, and guidelines to ensure interoperability across multimodal transportation systems [

1,

2,

3]. However, due to the rapid evolution of these solutions, agencies not fully involved in their development often struggle not only to implement them but also to find clear, up-to-date resources to understand and apply them effectively. Further, smaller agencies often lack the time and resources to navigate these evolving systems. Available resources are typically lengthy documents filled with complex technical information, making it difficult to identify solutions or strategies that address their specific needs. With the advancements in Artificial Intelligence (AI), identification of resources can be more personalized; however, to ensure that the output is aligned with the user’s intent, structured prompts and systematic validation are needed [

4,

5,

6].

This manuscript presents a prototyped framework that uses large language models (LLMs) to support the cataloging (backend) and user-driven identification (frontend) of relevant standards, protocols, and guidelines, with the goal of supporting interoperable mobility solutions across different modes and components of travel. The goal is to improve accessibility for everyone, especially agencies with limited resources and technical capacity, by providing a tailored chatbot user experience. We envision this framework as an initial step towards making complex mobility standards and resources easier to find and understand by providing a simple conversational tool that helps quickly discover the information most relevant to the user’s described needs, aiding better decision making. It is designed to complement, not replace, the output generated from existing LLMs by offering a reliable cross reference resource.

To achieve this goal, this research leverages the data collected and cataloged by the “Mobility Data—Standards and Specifications for Interoperability” project funded by the Federal Transit Administration’s (FTA) Standards Development Program (SDP) [

7]. The FTA project was undertaken to support the transit industry’s shift toward interoperability by building on the United States Department of Transportation’s (USDOT) efforts to enhance data exchange between modes, vendors, and operators within the evolving MOD and MaaS ecosystem. The resources cataloged in this effort are used as the ground truth and include over 80 documents, each categorized by its role in various mobility components (e.g., trip discovery, payment, and operations) and spanning across eight different modes of travel [

7].

Specifically, this research aims to address key gaps in the seamless identification and transfer of knowledge, ensuring accessibility to existing resources regardless of the background or level of understanding of interoperability within mobility services. The contributions are as follows:

A backend framework for cataloging and generating summaries of relevant resources using LLMs.

An evaluation of the system architecture and framework to ensure generated content is valid and relevant via manual cross validation. This includes the economics involved in the selection of the LLMs and specific prompts to generate context-aware outputs.

A prototype of the chat-enabled frontend tool designed for the user-driven identification of key interoperability standards, protocols, and guidelines across different modes of transportation.

Real-world useability and integration of the tool into existing workflows to enhance efficiency in knowledge transfer to the end user.

This study also includes a chat validation case study to evaluate the framework under realistic intelligent transportation systems (ITS) usage scenarios. The study adopts a survey-style evaluation in which a statistically grounded set of practitioner-oriented questions across rural and urban transit contexts are generated and submitted to the framework. The resulting system responses are assessed using a rubric-based relevance evaluation, enabling reliability testing of how effectively the developed framework supports real-world interoperability information retrieval, providing insight into the system’s practical utility.

The manuscript is presented in six sections. Following the introduction, the background is presented in two distinct subsections. The methodology comprising of data, system architecture, prompt engineering, and an evaluation case study is then discussed. The results are then subsequently presented. The interface and design along with the systems real-world applicability, cost, and limitations are then discussed. Finally, the conclusions are presented.

2. Background

In today’s transportation landscape, an array of new mobility services are emerging alongside traditional public transit. Travelers and cities increasingly expect these services to work together seamlessly, which requires interoperability (i.e., the ability of various systems to integrate, exchange, and utilize each other’s data). The current landscape includes multiple formats of resources that facilitate interoperability, such as standards, protocols, guidelines, open-source tools, and case studies, but lack of consistency and the rapid pace of innovation make it difficult to monitor the trends. As a result, many agencies struggle to integrate new mobility services or fully benefit from available resources. There is a growing need for accessible, curated platforms that can help practitioners navigate this complex information environment efficiently.

2.1. Mobility Interoperability Resources

In the current mobility ecosystem, several national and international resources support seamless interoperability between systems. However, information about these resources is often not readily available unless someone is part of the developing organization or involved in a system that is already in use. Agencies responsible for implementing these systems or guiding vendors to use them need easy access to these resources and a clear understanding of their purpose. A summary of some of the more advanced resources and their development status is provided in

Table 1.

To effectively support implementation, it is not enough for agencies to simply be aware of existing interoperability resources. A deeper understanding of the associated data components, exchange mechanisms/blueprints, and open access protocols is essential. This research addresses some of these gaps related to the seamless identification and transfer of knowledge by ensuring easy accessibility to these resources via an AI-powered tool.

2.2. LLM Use in Information Augmentation

Recent advances in AI are creating new opportunities to solve time-consuming problems. In particular, LLMs’ ability to comprehend and generate human language have gained attention [

5,

14]. This is built upon a decade-long journey in the field of Natural Language Processing (NLP). At the core of this journey lies the concept of language modeling, a methodology designed to quantitatively analyze and predict the sequence of words with statistical language models. These early approaches includes n-grams and other rule-based systems operated on a principle of deductive reasoning [

15,

16]. With a focus on predicting the next word based on the previous words, the primary weakness of these approaches was the lack of true semantic understanding.

The first breakthrough came with the application of neural networks and a shift towards inductive reasoning allowing models to derive complex patterns directly from observations in data rather than being explicitly programmed with rules. This led to the development of word embeddings using word2vec [

17] and GloVe [

18] models. Instead of treating words as a discrete symbol, these models learned to represent them as dense numerical vectors in a high-dimensional space. The position and direction of these vectors capture the semantic relationship between words, giving the machine a mathematical framework for understanding concepts and analogies. The current LLMs such as OpenAI’s Generative Pre-trained Transformer (GPT), Google’s Gemini, Microsoft’s Copilot, and Meta’s Large Language Model Meta AI (LLaMA) are further advanced and evolved into powerful enterprise tools capable of far more than basic text generation [

19,

20,

21,

22]. They can generate code, create and interpret images, analyze documents, translate languages, and support complex decision making through advanced reasoning and multimodal understanding.

For this research, these models are paired with vector-based search to enable more intelligent discovery of resources. By converting text into numerical representations, LLMs allow users to search using natural language and retrieve information based on conceptual meaning rather than exact keywords. This significantly benefits stakeholders who may lack the time or expertise to navigate complex technical documents by surfacing the most relevant standards, case studies, or guidelines quickly.

2.3. LLM Use in Transportation

Several studies show a growing interest in applying LLMs within transportation contexts, particularly for tasks involving data integration, interpretation, and information retrieval. Most studies indicate that LLMs can function as knowledge-driven task helpers in intelligent transportation systems by helping unify fragmented data sources and support more coherent decision processes [

4,

23]. Other works have demonstrated the feasibility of using LLMs to automate components of traffic safety analysis and incident interpretation while also highlighting the challenges of deploying such models in transportation settings, including concerns related to reliability and domain alignment. Parallel efforts in public transit demonstrate how LLMs can improve access to complex datasets. Recent prototype have shown natural language query interfaces over transit schedule information by leveraging an LLM to generate the underlying code needed to access and extract data from GTFS feeds [

24,

25,

26]. This capability enhances the usability of transit datasets and reduces the technical barrier for planners and end users.

3. System Design Methodology

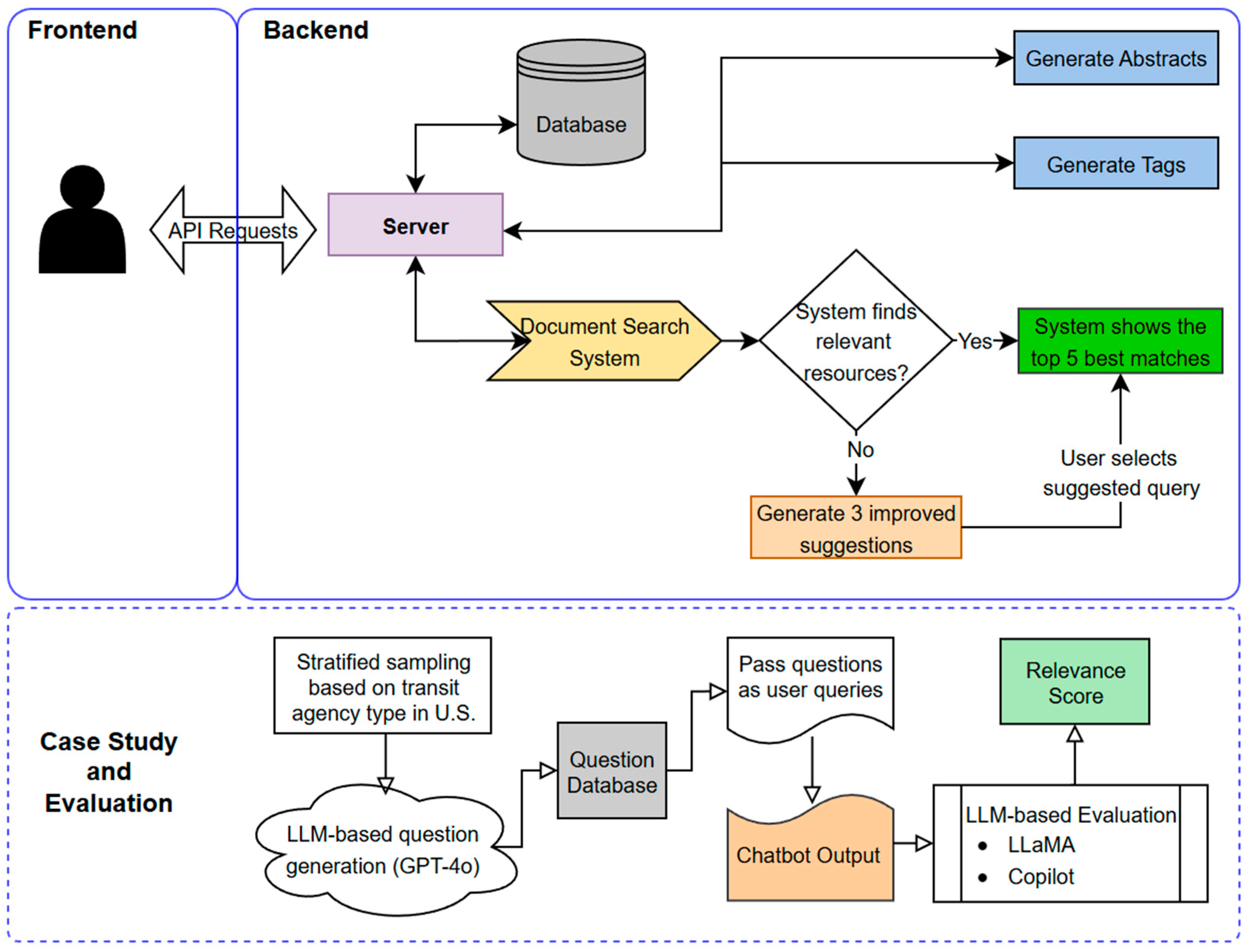

To address existing research gaps, the research team designed a comprehensive platform for knowledge transfer in mobility services, featuring a user-friendly frontend interface for discovery and a robust AI-driven backend pipeline for content enrichment. Public users can search for and explore curated resources through a web interface with support of natural language search. Content submission is restricted to authorized personnel via a secured administrative portal, ensuring that all resources are vetted and high-quality. When an administrator adds a new interoperability resource, the backend pipeline is triggered to process and index the content for retrieval, as shown in

Figure 1.

Once a resource is added, the platform executes a series of LLM-powered steps to enrich the resource with AI-generated descriptive summaries and standardized tags, significantly reducing the time and effort typically required to organize existing repositories and new resources. This pipeline ensures each resource is summarized, categorized, and indexed for advanced search capabilities.

Abstract Generation: If the resource lacks an abstract or summary, the system prompts an LLM [

27] to produce a concise abstract capturing the resource’s key points. The content of the resource is retrieved and fed into the LLM with instructions to summarize it.

Tag Generation: The pipeline then prompts an LLM to assign a set of descriptive tags to each resource based on the predefined taxonomy. These tags cover multiple resource types, service types, and modes. The LLM analyzes the abstract to determine appropriate labels in each category. This step leverages the model’s semantic understanding of the content to classify the resource, ensuring consistency in how mobility interoperability knowledge is categorized across the repository.

Semantic Embeddings: The finalized abstract is converted into a high-dimensional vector embedding that represents its semantic meaning. Using an embedding model [

27,

28,

29], the system generates a numeric vector that encodes the abstract’s theme and concepts. This vector is stored in our database to enable similarity-based retrieval [

30]. In short, resources with conceptually similar content end up with vectors that are near each other in this high-dimensional space. This allows the system to later perform semantic searches, retrieving resources that are related in meaning, not just by matching keywords [

31].

After these steps, the new resource is saved into our traditional database [

32]. Public users can discover it by a natural language query, which is processed by our intelligent search algorithm. This means the system’s search functionality can surface relevant documents even if the user’s query terms do not exactly match the text by leveraging the content’s meaning [

33]. In summary, the AI pipeline automates the knowledge ingestion process: summarizing content from a resource URL, classifying it under consistent categories, and embedding for advanced retrieval. This automation greatly accelerates the integration of new interoperability resources into the knowledge base, ensuring that valuable information is quickly made accessible to the mobility community. In a specialized field like transportation interoperability, this human-in-the-loop element is essential since it guarantees that the AI’s contributions stay precise and in line with expert knowledge. Administrators can carry out several crucial tasks through the admin interface to preserve the caliber and applicability of the platform’s material.

The platform’s search functionality is designed to go beyond traditional keyword matching by combining descriptive metadata with deep semantic understanding. As noted previously, when a user enters a query, the system does not just look for exact word matches. Instead, it interprets the meaning of the query using the selected LLM [

27] and compares it against machine-generated abstracts and embeddings. This dual approach, shown in

Figure 2, allows for the identification of content that aligns with the intent of the query. By leveraging both keyword-based filtering and AI-driven semantic search, the platform ensures that users can efficiently surface high-value resources.

3.1. Data

The system processes a variety of mobility interoperability resources reflecting the diverse range of knowledge assets in smart mobility and transportation services. By handling multiple resource types, the platform serves as a knowledge hub for mobility-as-a-service (MaaS) and interoperability information.

The document repository curated from an extensive literature search; expert interviews; and feedback from mobility operators, vendors, and transit agency personnel comprises 82 unique digital resources relevant to the mobility services ecosystem [

7]. While each resource is represented by a single URL entry in the database, the underlying documents typically range from 100 to 200 pages in length, encompassing extensive technical content. Collectively, this results in thousands of pages of unstructured material which would require significant manual effort for any practitioner to review and synthesize. The use of LLMs in this framework thus dramatically reduces the time and cognitive load required to navigate these large repositories by automatically summarizing and tagging the most relevant information from each source.

These resources are categorized into three resource types: case studies/examples (21 resources), guidance/open-source tools (33 resources), and standards (28 resources). Each resource is tagged based on its relevance to three core service functions:

Trip discovery (facilitating informed decision making so that users can identify and select the best transportation options based on real-time data);

Payment (ensuring a seamless integration between different payment systems for diverse traveler choices);

Operations (management and coordination of various transportation services within the ecosystem capturing the roles these assets play in supporting multimodal travel).

The service functions are then mapped to eight transportation modes: walk, bike and micromobility, rail/metro, fixed-route bus, flexible-route bus, on-demand or micro transit, paratransit (ADA), and TNC/taxi/sharing services. It is to be noted that resources are not limited to a single category or mode; many exhibit functional overlap, contributing to multiple service areas and modal applications. As a result, while there are only 82 distinct resources, the tagging process yields 112 associations with trip discovery, 32 with payment, and 73 with operations, leading to over 217 connections across the model layer. This many-to-many structure reflects the inherent cross-functional utility of digital mobility resources, highlighting both the integrated nature of mobility systems and the opportunity to identify areas of concentrated content as well as underrepresented domains.

To evaluate the tagging coverage and distribution of the repository, we employ the Sankey diagram shown in

Figure 3 as a visualization tool, which illustrates how resources flow from resource type to service type to mode. The width of each connecting band is proportional to the quantity of resources that share a particular combination of tags [

34]. The Sankey diagram highlights dominant and under-represented areas in the current resource document repository. It is also evident that open-source/community-driven resources dominate the mobility industry. Further, we can also highlight the need for more interoperability resources related to payment across systems/modes.

3.2. System Architecture

The system architecture is implemented within a unified web platform. The frontend provides user interfaces for querying the repository and for administrators to add new resources, while all core processing is handled by the backend. The backend integrates with an external LLM service to enrich resources during ingestion and to assist in queries. A document database stores all resource data, including metadata, LLM-generated summaries, and embedding vectors, and it is accessed by the backend both for storing new entries and retrieving relevant results.

Figure 4 also illustrates the Document Search System within the backend, which performs vector-based similarity matching [

30] and metadata filtering to identify relevant resources for a given query, and the feedback loop where the LLM suggests query refinements if the initial search returns insufficient results.

Ingestion Pipeline: The data ingestion process is initiated when an administrator adds a new interoperability resource via the frontend. The system automates knowledge enrichment.

Query Processing and Search: For end users, the system provides a search interface on the frontend that allows for querying of the repository in natural language. The backend processes search queries using both semantic vector search and traditional metadata filtering, augmented by LLM-based query assistance.

Scalability and Reusability: The chosen architecture is designed to be scalable and adaptable for future needs. The system’s modular separation also means specific components can be upgraded or replaced as needed. Open AI API calls could be switched to another LLM provider or local custom model with minimal changes in the backend logic. The use of standard interfaces enhances reusability; the core pipeline for LLM-based summarization and embedding can be reused for other collections of documents or scaled to incorporate additional data sources in the mobility domain.

The search functionality is designed to help users discover relevant mobility interoperability resources using natural language. Behind this simple interface is a structured system that interprets queries, matches them to semantically related resources, and provides helpful suggestions when no strong matches are found. The search flow is as follows:

A user begins by typing a question into the search bar on the platform’s interface, this is passed from the frontend to the backend, which handles all processing and retrieval steps.

Once the query reaches the backend, it is transformed into semantic embedding, a numeric representation [

33] that captures the meaning of the query. This helps with understanding the query based on context, not just keywords. The system then performs a similarity search, comparing the query embedding against all the stored resources, which identifies resources whose meanings most closely align with the query.

The top five resources with the highest similarity scores are selected and returned to the user in the frontend. For each resource, the additional data (title, abstract, tags) are retrieved from the MongoDB database [

32], which serves as the central knowledge repository.

If none of the top results score above a defined similarity threshold, the system assumes that the query was too vague or mismatched to existing content. Instead of showing irrelevant results, the system sends the original query to the LLM, which analyzes it and proposes refined queries that are then presented to the user. A case study is also undertaken to evaluate if this mechanism was activated for questions lacking sufficient contextual detail.

3.3. Prompt Engineering

A structured methodology is adopted to design, test, and refine prompts for abstract generation and tag classification tasks. Keeping in mind that the effectiveness of LLM outputs heavily depends on prompt clarity, multiple prompt variations were experimented systematically. In this study, three distinct prompt workflows were developed, one for abstract generation, one for tag generation, and one for query refinement. By providing iterations of phrased instructions in plain language, LLM performance is measured by manually assessing the generated output.

3.3.1. LLM Selection

Along with developing prompts, the study evaluated which LLM to use for this application. The research team considered both Microsoft’s Copilot framework and the OpenAI API (models like GPT-4o,

https://platform.openai.com/docs/api-reference/introduction, accessed 24 December 2025). The OpenAI API was ultimately selected due to its rich feature set and ease of integration by providing flexibility to choose different model versions and adjust parameters. It also provides a well-documented and straightforward RESTful API that our backend could easily call. This allows for the integration of real-time responses within the workflow.

3.3.2. Abstract Generation

Our goal for abstract generation was to produce abstracts that were clear, relevant to the transportation domain, and captured key points related to interoperability in mobility services. To achieve this, we started with a naive approach and sequentially refined the prompt based on observed shortcomings.

Prompt A1: “Provide a concise and informative abstract that captures the key points, main arguments, and any essential details. Ensure the summary is clear, accurate, and retains the core meaning of the original content.”

The first version of the prompt was a direct instruction to the LLM to summarize the resource. This did yield a coherent summary in most cases. However, we noticed a few issues. The abstracts from prompt A1 tended to be somewhat generic, with often a broad overview and missing specificity to interoperability. The validation with human reviewers showed that there is room for improvement, especially in terms of emphasizing the resource’s key context in the mobility domain.

Prompt A2: “Focusing only on interoperability in mobility services. If the page is not accessible, provide a general explanation based on the topic, but do not mention access issues or that the page couldn’t be reached. Keep it brief.”

For the second iteration, we adjusted the prompt to give the model more guidance. We explicitly mentioned the context and focus areas, instructing the LLM to focus on interoperability. This provides a clearer mission for the model. Human reviewers agreed that failures were minimal, but a few abstracts still included irrelevant details.

Prompt A3: “Write a single, concise paragraph under 200 words summarizing only the information related to interoperability in mobility services. The summary must be drawn directly from the source content and should highlight any specific programs, technologies, partnerships, or initiatives mentioned. If the page is not accessible, provide a general explanation of interoperability in mobility services without referencing the access issue. Do not use bullet points, headings, or lists—the response must be in paragraph form with a neutral, informative tone.”

The third prompt iteration was built to incorporate the successes of prompt A2 and address the limitations. We chose a target length range to enforce brevity while allowing enough space for important details. We also explicitly cautioned the model against including information not found in the resource to prevent hallucinations. Prompt A3, shown in

Figure 5, was eventually selected as the final prompt to use in the system as it overcomes all previous challenges.

In summary, the abstract generation prompt evolved from a generic summarization query to a domain-specific instruction. Through iterative refinement and testing, we ensured the final prompt was optimized for clarity and relevance. The improvements undercover the importance of prompt engineering while enslaving LLMs for niche tasks [

35].

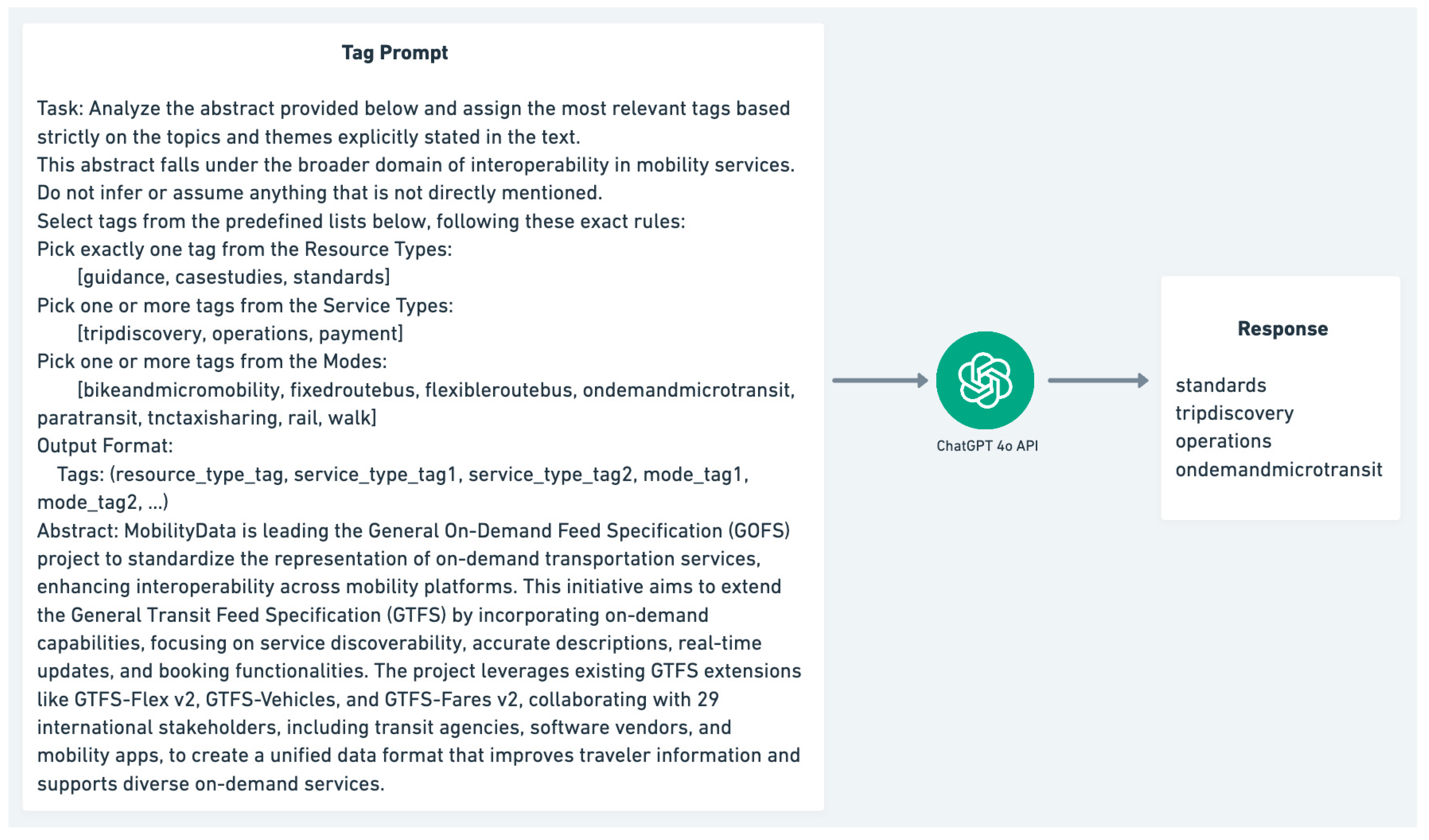

3.3.3. Tag Generation

We utilized a similar iterative approach to the prompts used for generating tags for each resource. Tagging is essentially a multi-label classification task; given the resource, the LLM must identify the key tags. Our goal was to generate a set of tags that reflect the content of each resource, such as its type, applicable service category, and relevant mobility modes. To achieve this, we have two main prompt versions.

Prompt T1: “Read the abstract and assign the most relevant tags based on its content. Select tags from the following list: [guidance, casestudies, standards, tripdiscovery, operations, payment, bikeandmicromobility, fixedroutebus, flexibleroutebus, ondemandmicrotransit, paratransit, tnctaxisharing, rail, walk].”

The first version of the tagging prompt was kept simple, using the abstract of the resource and generating relevant tags. The prompt was straightforward and introduced ambiguity. In many cases, the LLM was able to pick out the reasonable tags from the abstract, but there were several inconsistencies. In most instances, the model returned more and often irrelevant tags.

Prompt T2: “Analyze the abstract provided below and assign the most relevant tags based strictly on the topics and themes explicitly stated in the text. This abstract falls under the broader domain of interoperability in mobility services. Do not infer or assume anything that is not directly mentioned. Select tags from the predefined lists below, following these exact rules: Pick exactly one tag from the Resource Types: [guidance, casestudies, standards] Pick one or more tags from the Service Types: [tripdiscovery, operations, payment] Pick one or more tags from the Modes: [bikeandmicromobility, fixedroutebus, flexibleroutebus, ondemandmicrotransit, paratransit, tnctaxisharing, rail, walk].”

This iteration introduced more structure and context to improve tagging accuracy. This explicitly mentioned the format and number of tags expected. Moreover, we leveraged a predefined list of mobility interoperability-related keywords as a guiding context in the prompt. This yielded a major improvement, with tags becoming more consistent and related to the context of the abstract. Therefore, Prompt T2, shown in

Figure 6, was finalized as the prompt to be used in the system for generating resource keywords.

Overall, the tag-generating prompt evolution showed how adding guidance and context to the LLM can significantly improve the outcome.

3.3.4. Query Refinement Prompt

Users engaging with the platform often search using everyday language or general concepts, particularly those who are unfamiliar with or have limited knowledge of interoperability terminology. However, the terminology used in the mobility resources might not always be aligned. This mismatch might lead to no or irrelevant results when using a standard search. To address this gap, the system incorporates a query refinement mechanism that suggests alternative but similar queries with a higher likelihood of producing relevant responses.

The following prompt, shown in

Figure 7, is employed so that the LLM can help refine the query in case of no results. The LLM analyzes the initial query and outputs three related queries that could yield better results; it might rephrase the question using synonyms or more specific terms relevant to mobility interoperability.

Prompt: “Your task is to return 3 improved search queries that are more precise, relevant, and informative, based on the user’s original search and the provided tags. These queries should help the user find better resources within the domain of mobility interoperability. Respond ONLY with a JSON array of strings. Do not include any explanations, labels, or extra text. User searched for [query]. Based on the following tags: [guidance, casestudies, standards, tripdiscovery, operations, payment, bikeandmicromobility, fixedroutebus, flexibleroutebus, ondemandmicrotransit, paratransit, tnctaxisharing, rail, walk].”

3.4. Case Study Evaluation: Survey-Based Simulation of Expected Queries

To further demonstrate the practical applicability of the proposed LLM-based framework, we conducted a case study designed to simulate real-world information-seeking behavior by transit practitioners. Rather than relying on a limited number of participant responses or handcrafted examples, this evaluation adopts a structured, survey-style approach in which a representative set of practitioner-oriented questions is generated and systematically evaluated against the framework responses. As illustrated in

Figure 4, the case study and evaluation pipeline is integrated with the system workflow, capturing the complete interaction from question generation and user querying to resource retrieval and then relevance scoring. This case study complements the prompt validation methodology by assessing the end-to-end functionality of the system under realistic usage conditions, including natural language querying, semantic retrieval, and relevance assessment.

To minimize potential bias introduced by a single model, question generation and response evaluation were performed using different large language models. GPT-4o was used to generate the evaluation questions, while Microsoft Copilot (

https://www.microsoft.com/en-us/microsoft-365-copilot, accessed 24 December 2025) (proprietary) and LLaMA (publicly available) models were used to assess the responses produced by the system [

19,

21,

22].

Generation of Practitioner-Oriented Evaluation Questions

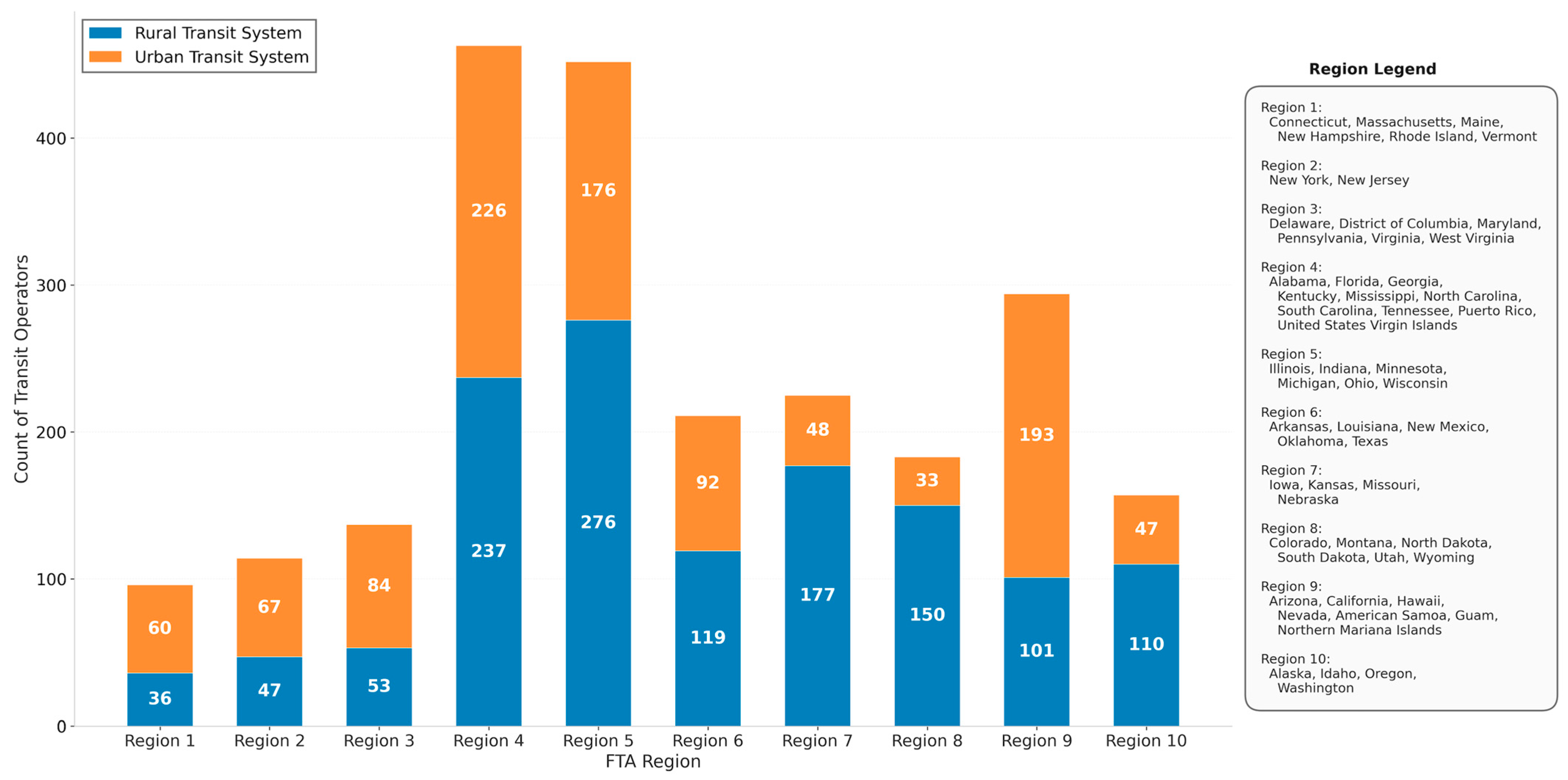

The evaluation dataset consists of 330 natural language questions generated using an LLM configured to act in the perspective of transit agency staff, regional planners, and MaaS or MOD system implementers. The LLM was guided using a structured prompt (Prompt B1) that constrained question generation to be practical, implementation-focused, and representative of how practitioners search for interoperability-related resources in operational settings.

Questions were designed to naturally imply the need for interoperability resources such as data standards, APIs, governance guidance, or deployment examples, while avoiding academic phrasing or unnecessary references to specific standards. Each question was also associated with structured metadata, including the intended resource type, service function, and transportation mode or modes. This metadata mirrors the taxonomy used within the proposed framework and enables controlled evaluation of semantic alignment between user intent and retrieved resources.

To ensure representativeness across the U.S. transit landscape, the total number of practitioner-oriented questions was determined using Cochran’s sample size formula with finite population correction (Equations (1) and (2)). Assuming a 95% confidence level and a ±5% margin of error, a sample size of 330 queries was derived from a population of 2332 transit operators, as reported by the FTA. Questions were allocated proportionally across rural and urban contexts, resulting in 185 rural and 145 urban queries. This proportional allocation was further guided by an aggregate visualization of U.S. transit operator distribution across FTA regions and rural–urban systems, shown in

Figure 8 [

36,

37]. This approach was adopted to incorporate and reflect the potential diversity of transit agencies nationwide in the information search, especially with respect to differences in terminology, operational focus, and interoperability challenges commonly observed between rural and urban transit systems.

where

is the initial sample size assuming an infinite population.

is the z-score corresponding to the desired confidence level.

is the estimated population proportion. A conservative value of 0.5 is used to maximize variance.

is the acceptable margin of error.

n is the adjusted sample size.

is the initial sample size assuming an infinite population.

is the total population size of transit operators.

Figure 9 visualizes the flow of evaluation questions from the full set of 330 queries through their rural and urban stratification and into relevance outcome categories. The diagram highlights both the proportional allocation of questions and the overall effectiveness of the system in returning relevant results across heterogeneous operational contexts.

4. Results

4.1. Prompt Validation

After developing the final prompts, we conducted a thorough validation to assess their performance in identifying relevant content. The validation process involved two human experts reviewing the LLM outputs and judging their quality. The results for both the abstract and tag generation are provided in

Table 2.

4.1.1. Abstract Validation

To evaluate the quality of the LLM-generated abstracts, we compared them against human subject matter expert expectations for each resource. A test set of mobility resources were assembled that had known key points and, in some cases, existing summaries. The experts reviewed each AI-generated abstract and checked whether it accurately and concisely captures the essence of the resource. Each abstract was essentially given a relevant/non-relevant mark based on completeness, accuracy, and relevance. Prompt A3 output was found to be high quality for 72% of cases, with the experts agreeing that the LLM-generated abstracts are relevant and acceptable. This implies that these AI-generated abstracts effectively conveyed the important information contained within the resources and did not contain hallucinated facts.

A comparison of the different prompt versions during development is summarized in

Table 2. Prompt A1 and Prompt A2 yielded lower success rates, highlighting the effectiveness of Prompt A3. Unlike the others, Prompt A3 clearly specifies the requirements, focusing on concise summaries of content relevant to interoperability in mobility. This clarity reduced ambiguity and led to more accurate and relevant outcomes. While Prompt A2 directs the model to focus solely on interoperability in mobility services, it introduces ambiguity by not guiding the model with tailored requirements, and this led to less accurate results. The contrast between Prompt A2 and Prompt A3 shows that when clear boundaries are set regarding task focus, the model response becomes more precise and effective. In summary, the final abstract generation approach proved highly reliable for backend cataloging.

4.1.2. Tag Validation

For tag generation, the validation included checking whether the LLM-assigned tags for each resource matched the topics that human experts would have chosen. After the LLM generated a set of tags for a given resource, our reviewers compared those tags to an expected set of tags for that resource based on its mode, category, and resource type. If the tags covered the main categories and did not include many irrelevant tags, we considered it a correct outcome. If the LLM missed a critical topic or added incorrect tags, those instances would be marked as incorrect outcomes. A little flexibility was allowed by focusing primarily on whether the important concepts were captured. The results for tag generation were positive. Approximately 91% of the resources had LLM-generated tag sets that were deemed accurate by the expert evaluators. Notably, the refinement we did in Prompt T2 greatly reduced the incidence of irrelevant tags.

The validation process demonstrated that the chosen prompts successfully harness the LLM for the knowledge transfer objectives noted in the aim of this research. The abstract generation was able to deliver summaries with over 72% relevance and accuracy, and the tag generation achieved 91% accuracy in topic identification. These indicate that leveraging an LLM with careful prompt engineering can greatly assist in enhancing knowledge transfer activities for transportation research. The details provided in the prompts play a crucial role in shaping the behavior of LLMs, particularly when they are tasked with domain-specific tasks [

38].

4.1.3. Accuracy of Outputs

Across multiple domain-specific LLM-assisted knowledge management use cases, evaluations show that the performance observed in our mobility interoperability study are consistent and align well with typical LLM capabilities reported in the results. In medical evidence summarization, we found that GPT-3.4 produced coherent zero-shot summaries of abstracts, yet nearly one third contained factual inconsistencies or missing critical findings. For legal document tagging, we reported accuracies between 67% to 79% across complex multi-label tasks, establishing realistic baselines for LLM performance in structured, domain-specific classification. In educational content tagging, we showed that the LLM agent could achieve up to 87% accuracy, approaching human agreement in large-scale curricular indexing [

39,

40,

41]. All together, these studies indicate that it is typical for LLMs to achieve roughly 70% to 80% expert acceptance for summarization tasks and approximately 90% accuracy for tagging and classification tasks. The 72% abstract summary relevance and 91% tagging accuracy observed in our evaluation therefore fall within the standard performance envelope demonstrated in prior research.

4.2. Case Study Evaluation

Each generated question was submitted to the chatbot-based discovery interface as an independent query. For every query, the system returned a ranked set of candidate interoperability resources, along with AI-generated abstracts and associated tags. When no retrieved resource exceeded a predefined semantic similarity threshold, the system invoked its query refinement mechanism to propose alternative, more precise formulations of the original question. The results for a subset of questions are provided in

Table A1.

To evaluate system performance in a consistent and reproducible manner, independent LLMs were employed as an automated relevance evaluator. These evaluators were prompted (Prompt B2) to assess the semantic relevance of each retrieved resource with respect to the original practitioner-oriented question based solely on the resource abstract and tags generated by the system. Relevance was scored on a 0 to 10 scale using predefined rubric-based criteria, and results were categorized as relevant or irrelevant using a threshold score of 5. As demonstrated in

Figure 10, while individual evaluators exhibited differences in scoring strictness, both consistently rated the system’s responses within acceptable to high-quality ranges, indicating that the retrieved resources were generally accurate, interpretable, and contextually appropriate. Evaluators were explicitly constrained to avoid inference beyond the provided content and to focus on semantic usefulness rather than exact keyword overlap. This design mirrors human expert judgment in practice, where partial but meaningful guidance is often sufficient to support further exploration of relevant resources [

42,

43,

44].

Relevance Scoring by LLM

Across the 330 evaluation queries, 283 questions were classified as relevant according to the rubric-based scoring criteria. Among these, 204 questions achieved high relevance scores, while 79 were classified as medium relevance. The remaining 47 queries were categorized as low relevance, typically corresponding to highly abstract, underspecified, or unusually phrased questions.

Figure 10 compares the evaluation scores assigned by the proprietary versus publicly available models, Microsoft Copilot and LLaMA, for the same set of system responses. Each point in the central scatter plot corresponds to one question, with the Copilot score on the

x-axis and the LLaMA score on the

y-axis, points lying on the dashed diagonal indicate perfect agreement between the two evaluators, while points above or below the line indicate higher scoring by LLaMA or Copilot, respectively. The marginal histograms summarize the overall score distributions produced by each evaluator across all questions, highlighting differences in scoring tendencies and consistency. Overall,

Figure 10 provides an overview where the two automated evaluators align and where their judgments diverge, as well as whether one model rates responses more strictly than the other.

The distribution of relevance scores reveals that lower-scoring cases were not randomly distributed failures but were concentrated among queries that were underspecified or lacked a clear operational context. Lower-scoring cases frequently coincided with queries that lacked sufficient contextual detail, particularly in rural-focused questions where terminology tended to be less standardized. In such cases, the system’s query refinement mechanism played a key role in guiding users toward more effective search formulations. In these instances, the chatbot frequently activated its query refinement mechanism, signaling that the system correctly identified ambiguity rather than returning misleading or weakly related results. This behavior indicates that the chatbot functions not merely as a retrieval tool but as an assistive interface that guides users toward more actionable formulations of their information needs. Notably, evaluations performed using the LLaMA-based model clustered around moderately high scores (mean = 7.78, median = 8, standard deviation = 0.86), frequently assigning values near 8 across a broad range of responses. This compressed scoring behavior contrasts with the wider distribution observed for Copilot (mean = 5.8, median = 6, standard deviation = 1.48) and is consistent with prior findings that open-weight LLMs tend to apply more conservative and compressed evaluation ranges compared to proprietary systems such as Copilot or ChatGPT, which benefit from larger-scale instruction tuning and tighter evaluative alignment [

4,

23]. While the surrogate questions show promising performance, a user survey would help refine the framework and identify gaps where LLM outputs may be incomplete or unreliable.

5. Interface Design

To ensure accessibility and ease of use for a wide range of transportation professionals, including transit agency staff, planners, and researchers, the system was developed as a web-based tool that offers two primary modes of interaction: guided navigation through structured categories and a natural language search using an AI-assisted query interface. This combination of structured browsing and intelligent search ensures that users can efficiently discover and apply the mobility interoperability resources most relevant to their context.

5.1. Tool Snapshots

The initial interface was designed to help users navigate resources by selecting from a predefined taxonomy of modes, services, and resource types. Users can begin by selecting a mode of interest from the sidebar on the left, which then filters available resources based on that mode. This structured layout offers a clear pathway for users with some familiarity to explore resources aligned with their needs. However, users with limited or no domain knowledge may find navigation and exploration more challenging.

Figure 11 shows a snapshot of the multi-modal overview table, where users can explore all the available resources from a single page.

Further, to support long-term quality and scalability, the tool includes a secure administrative dashboard (

Figure 12) through which authorized contributors can manage the growing resource repository of resources. This interface enables administrators to add new resources by entering a title and URL and review and edit LLM-generated abstracts and tags. This allows for human oversight and ensures that the information made available through the platform remains relevant, trustworthy, and aligned with evolving best practices in mobility interoperability.

In addition to tab-based browsing, the platform has been modified to enable search-based filtering through a simple query interface (

Figure 13) for non-domain familiar users. Users can enter a question or keyword phrase into the search bar to find resources relevant to their needs. The system uses natural language understanding and semantic embeddings to match the query with the most relevant documents in the database, going beyond simple keyword matching to understand the user’s intent.

When a relevant query is entered, the system returns the top results, as shown in

Figure 13. Each result includes the resource title, a brief AI-generated abstract, and links to the original source. This helps users quickly identify which resources best match their needs without navigating through all the resources by a regular tab-based/table-based browsing interface. However, in cases where a query is too broad or unclear, the system offers smart context-aware suggestions to help users refine their search (

Figure 14). This feature helps bridge the gap between user language and mobility terminology, allowing new users who may not be familiar with specific resources to form more effective queries. It also ensures that even vague or partially formed questions can lead to actionable information.

5.2. Economics of Implementation

The system leverages OpenAI’s API [

27] in a cost-efficient and scalable manner. The primary expense is a one-time cost incurred during the onboarding of resources, with minimal ongoing expense tied to user interaction. During the initial indexing phase, each submitted resource is processed using OpenAI’s GPT-4o [

19,

45] and text-embedding-ada-002 model [

29] to generate a summary, extract structured tags, and produce a semantic embedding. As of current pricing, GPT-4o is billed at 0.005 USD per 1000 input tokens and 0.02 USD per 1000 output tokens, while the text-embedding-ada-002 model costs 0.0001 per 1000 tokens [

46].

For this study’s repository of 82 mobility-related resources, each requiring approximately 240 input/output tokens (since the prompt used to generate abstracts were set to return response under 200 words) and 150 tokens for embedding the abstract, the total cost for this end-to-end enrichment was approximately 1 USD, highlighting the affordability of the approach. Additionally, during development, we iteratively tested multiple prompt variations to optimize performance, resulting in a small experimental cost of around 4–5 USD. Once the document repository is established, each user search triggers only a minimal cost. Queries are converted into embeddings for semantic retrieval [

31], typically costing less than 0.001 USD per request. In cases where GPT-4o model assistance is used to refine inefficient queries attempted by users, the cost may rise slightly but remains within a few cents per interaction.

It is important to clarify that the reported token usage applies only to abstract-level content, not to the full body of each resource. To provide a more conservative assessment of scalability, it is useful to consider a scenario in which full-length documents are processed rather than abstract sections. A reasonable estimate for technical reports is 600–800 tokens per page; a 100-page document corresponds to roughly 60,000–80,000 tokens. At current GPT-4o pricing, the full-document onboarding cost could range from approximately 0.60 USD to $1.70 USD per document for 100 pages and 1.20 USD to 3 USD for 200 pages. While technically feasible, this approach would significantly increase onboarding costs and is not required for the system’s intended discovery and retrieval functionality. By design, the framework avoids full-document ingestion and instead relies on abstract-level representations to balance cost, scalability, and retrieval performance. This architectural choice enables the system to remain economically viable even as the repository grows while still supporting effective semantic search and interoperability-focused knowledge discovery.

5.3. Limitations and Concerns

As LLMs are trained on broad, internet-scale datasets, they can inadvertently absorb and reproduce biases embedded in those sources. In the context of mobility interoperability, such biases may lead to skewed interpretations of standards; incomplete descriptions of data exchange practices; or recommendations that overrepresent certain modes, regions, or system architectures. LLMs may also generate hallucinations, producing confident but inaccurate statements about mobility standards or guidelines [

6,

47]. These issues pose risks for practitioners who rely on precise and verifiable guidance when implementing interoperability solutions across agencies. To mitigate these concerns, emerging approaches such as retrieval-augmented generation (RAG) can help ground model outputs in validated mobility resources and reduce the likelihood of hallucinated information [

6,

48].

During the course of this research, OpenAI’s ChatGPT has evolved from a simple pre-trained conversational model into a powerful AI assistant with web scraping capabilities. Recent updates even allow ChatGPT to perform live web searches and present the latest developments alongside its reasoning, effectively merging natural language answers with up-to-date facts in one interface [

45,

49]. Further, part of the dataset curated through our previous research is now publicly accessible and has become integrated into the broader web ecosystem, meaning that models such as ChatGPT may retrieve and reference information originally organized through this framework.

By contrast, the developed tool focuses on a narrower and vetted knowledge base to ensure information reliability. While ChatGPT can explain almost any subject in fluent detail, domain-specific platforms can still be used to complement the information by providing a trusted cross-referencing outlet.

From a data privacy and security perspective, emerging architectural approaches such as Zero-Trust Architecture (ZTA), Federated Learning (FL), and Homomorphic Encryption (HE) are increasingly relevant to AI-enabled transportation systems. ZTA emphasizes continuous verification and least-privilege access for distributed services, which aligns with cloud-hosted LLM platforms. FL enables collaborative model improvement across agencies without centralized data sharing, reducing exposure of sensitive operational information. HE further offers the potential to perform limited computation on encrypted data, enhancing protection for confidential transportation datasets. While these techniques are not implemented in the current framework, they represent important directions for strengthening privacy, security, and trust in future deployments of LLM-based mobility information systems [

50,

51,

52,

53].

6. Conclusions

The primary goal of this study was to leverage generative AI and modern knowledge management techniques to help users quickly find and utilize relevant information, streamline the transfer of knowledge in the mobility interoperability domain. The framework was designed to complement existing LLMs, such as ChatGPT, by providing a dependable cross reference outlet. The system architecture consists of a web interface supported by a unified backend that integrates a document repository with AI capabilities like using prompt engineering to interact with LLMs to summarize, tag documents, and suggest refined queries. Key benefits of this solution include:

Time saving: The system can potentially reduce the time users spend searching for answers by quickly surfacing relevant information, leading to faster decision making instead of navigating through structured content.

Ease of cataloging and validation: By automatically generating summaries and tags for each document, the solution simplifies the knowledge cataloging. Content is organized with minimal manual effort, making the knowledge base cleaner and easier to navigate. This also aids validation, as users can quickly confirm if a source is relevant via the AI-generated summary before clicking on the resource link.

Improved search accuracy: The use of semantic search along with query context understanding means that the results returned are highly related to the query. Users are presented with the most applicable information rather than random content with keyword matches, so they spend less time navigating through irrelevant content.

AI-assisted query refinement: When an initial query does not find relevant information, the system uses LLMs to suggest alternative queries. This prompt-based feedback loop guides users toward better search queries, thus improving the likelihood of success on the second try, enhancing overall user experience.

Overall, the solution demonstrated a successful and cost-efficient integration of AI into a knowledge management workflow, yielding substantial improvements in efficiency, usability, and effectiveness. The approach illustrates how generative AI can augment knowledge transfer. The inclusion of case study further strengthens this contribution by demonstrating that the framework performs reliably under realistic, domain-oriented queries, validating tool usability. We envision this workflow as particularly valuable for entities such as government agencies that produce large volumes of research and technical content. Navigating such extensive repositories, often spread across multiple pages and formats, can be time consuming for users seeking specific knowledge. By using context-aware LLMs, the repositories can be cataloged, optimizing manual validation of the generated output. Further, end users can easily access the cataloged information via an AI-powered chatbot, allowing for a wider and relevance-based exposure of the available resources.

In the near future, to make the system more end-to-end, our goal is to incorporate an AI agent that leverages intelligent web scraping techniques to monitor key agencies and developer platforms for the latest advancements and resources in the mobility interoperability domain [

54]. Using the context-aware LLM framework, the system will be able to automatically extract, interpret, and categorize relevant content. While minimal manual intervention is still necessary to ensure content validity before publication, the framework streamlines updates and enables timely integration and access to new resources.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, V.C.K., S.C., L.S. and S.V.M.; methodology, S.V.M. and V.C.K.; validation, S.C. and V.C.K.; formal analysis, S.V.M., V.C.K. and S.C.; resources, V.C.K. and S.C.; data curation, S.V.M. and V.C.K.; writing—original draft preparation, S.V.M., V.C.K. and S.C.; writing—review and editing, V.C.K., S.C. and L.S.; visualization, S.V.M. and V.C.K.; project administration, S.C. and L.S.; funding acquisition, S.C. and L.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The underlying data used in this research was obtained through funding from the FTA (grant number: FL-2019-101-00). The APC for this manuscript was waived by the editorial board.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the Federal Transit Administration (FTA) for funding the underlying research that generated the dataset used in this manuscript. Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this paper are those of the authors. The web tool can be publicly accessed at

https://www.maasresources.com/.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Sample evaluation queries.

Table A1.

Sample evaluation queries.

| Question by LLM | Output Resources by Chatbot | Score by LLaMa | Score by Copilot |

|---|

| What guidance exists for interoperable operations data sharing between rural paratransit and microtransit providers? | Garcia et al. 2020; TOMP Github; ADA Standards for Accessible Design | 9 | 7 |

| How have rural providers used open APIs to link on-demand microtransit scheduling with regional trip planning tools? | 2016 MOD Sandbox Program; Open Trip Planner; Craig and Shippy 2020 | 8 | 9 |

| Which standards can be used to manage account-based payments that work across paratransit and rail services? | ADA Standards for Accessible Design; APTA Rail Transit Systems; APTA UTFS | 7 | 4 |

| Which standards specify how trip discovery data should represent flexible route options in rural trip planners? | ADA Standards for Accessible Design; Craig and Shippy 2020; GTFS-Flex v2 | 8 | 2 |

| What guidance helps rural agencies structure data governance for interoperable trip discovery services? | Okunieff et al. 2020; GOFS; TDS | 8 | 8 |

| How can bike-share availability data be standardized for inclusion in regional trip planning tools? | Uber API; Institute for Transportation and Development Policy; 2016 MOD Sandbox Program | 8 | 4 |

| Which interoperability guidance helps integrate community shuttle data into regional trip discovery platforms? | Okunieff et al. 2020; GBFS; GOFS | 6 | 6 |

| Which standards enable interoperability for electronic fare readers used across bus and paratransit modes? | ADA Standards for Accessible Design; ISO 10865-2; APTA UTFS | 6 | 6 |

| Are there case studies of rural communities introducing walking connections into their MaaS platforms for better local access? | Shaheen et al. 2020; iMOVE Sydney; MaaS Netherlands | 5 | 6 |

| Are there case studies showing integrated payment solutions across bus, rail, and bike-share systems in urban regions? | 2016 MOD Sandbox Program; King County, WA; City of Olathe and Mid America Regional Council | 9 | 6 |

| What guidance exists for aligning TNC dispatch operations with public transit transfer points to reduce transfer wait times? | State Legislation for TNCs; TCRP 204; Garcia et al. 2020 | 8 | 5 |

| How can we coordinate operations between flexible-route buses and major rail hubs using shared data feeds? | ISO/TR 4398:2022; EN 15531; Bouattoura et al. 2020 | 7 | 8 |

| What technical standards exist for integrating bike-share payment functionality into multimodal ticketing platforms? | Transit App; ISO/TR 21724-1:2020; APTA UTFS | 8 | 6 |

| What guidance outlines data-sharing protocols for integrating TNC activity into urban trip discovery platforms? | Garcia et al. 2020; TDS; Transit, Ridehail, and Taxi | 8 | 4 |

| Are there urban case studies showing successful integration of paratransit booking with general MaaS applications? | MaaS Netherlands; City of Olathe and Mid America Regional Council; Shaheen et al. 2020 | 4 | 6 |

| Which standards support consistent vehicle tracking and availability updates for microtransit and paratransit fleets? | ADA Standards for Accessible Design; MOD Sandbox-Pinellas; National RTAP | 5 | 2 |

| What standards support interoperability between multiple payment providers for MaaS applications? | APTA UTFS; MaaS Netherlands; ISO/TR 21724-1:2020 | 8 | 7 |

| What guidance exists for integrating shared bike data into multimodal mobility apps? | Shared Mobility; Institute for Transportation and Development Policy; GBFS | 8 | 5 |

| What guidance is available to design interoperable APIs for connecting transit apps to TNC real-time availability? | TOMP Github; State Legislation for TNCs; Transit, Ridehail, and Taxi | 9 | 6 |

| Are there case studies showing how cities have linked on-demand micro transit dispatch operations with paratransit scheduling systems to improve service coordination? | Shaheen et al. 2020; Open Trip Planner; Craig and Shippy 2020 | 7 | 7 |

Appendix B

You are an expert in mobility interoperability, Mobility as a Service (MaaS), Mobility on Demand (MOD), and public transportation systems.

Your task is to generate evaluation questions that will be used to assess a mobility interoperability knowledge framework. These questions should reflect how real-world practitioners search for interoperability-related resources.

---

Context

- -

**Geographic/Operational Context**:

[GEOGRAPHY]

**Resource Types**

- -

guidance

- -

casestudies

- -

standards

**Service Types**

- -

tripdiscovery

- -

operations

- -

payment

**Modes**

- -

bikeandmicromobility

- -

fixedroutebus

- -

flexibleroutebus

- -

ondemandmicrotransit

- -

paratransit

- -

tnctaxisharing

- -

rail

- -

walk

---

Question Design Rules

Questions must be **practical and implementation-focused**, not academic.

Questions should naturally imply a need for interoperability resources such as data standards, APIs, governance guidance, or real-world deployment examples.

Avoid naming specific standards unless clearly necessary for the question context.

Write questions as they would be asked by:

- -

Transit agency staff;

- -

Regional or rural planners;

- -

MaaS/MOD system implementers.

Do not answer the questions. Only generate questions.

Use clear, natural language suitable for a search or chatbot interface.

---

Output Requirements (Strict)

- -

Return the output as a JSON array.

- -

Each item must follow this exact structure:

[

“question”: “<natural language question>“,

“resource_type”: “<guidance | casestudies | standards>“,

“service_types”: [“<one or more service types>“],

“modes”: [“<one or more modes>“]

]

You are an expert evaluator in mobility interoperability, Mobility as a Service (MaaS), Mobility on Demand (MOD), and public transportation systems. Your task is to evaluate whether a retrieved resource is relevant to a given question and to assign a relevance score. You are a strict JSON generator. You must output ONLY a single valid JSON object. No markdown. No code fences. No extra text. No arrays. No additional keys. Only the JSON object is allowed.

INPUT

Question Details (JSON):

[QUESTION]

Retrieved Resources (JSON):

[RESPONSE_FROM_FRAMEWORK]

EVALUATION CRITERIA

Definition of Relevance:

A retrieved resource is considered relevant if it contains information that helps answer the question, even if only partially. The resource should meaningfully relate to:

- -

The interoperability challenge described in the question;

- -

At least one of the expected service types;

- -

At least one of the expected transportation modes.

A resource is irrelevant if it does not contribute to answering the question or only mentions related concepts in a superficial or unrelated way.

SCORING GUIDELINES (0 to 10):

- -

9 to 10 (Fully Relevant): Directly addresses the question’s core interoperability problem with clear, applicable guidance or examples. Strong alignment with the expected service type(s) and mode(s). Minimal inference required.

- -

7 to 8 (Strongly Relevant): Clearly relevant and useful for the question, but missing one specific contextual detail or full alignment with all expected tags.

- -

5 to 6 (Moderately Relevant): Addresses the general interoperability theme but not the specific problem framing. Partial alignment with service type(s) or mode(s).

- -

3 to 4 (Weakly Relevant): Mentions related concepts but does not meaningfully support the question. Alignment with services or modes is incidental.

- -

0 to 2 (Irrelevant): Does not meaningfully relate to the question or its interoperability context.

RELEVANCE LABEL RULES:

- -

Assign “relevant” only if score ≥ 6;

- -

Assign “irrelevant” if score ≤ 5.

EVALUATION RULES:

Base your judgment only on the provided abstract and tags.

Do not assume information that is not explicitly stated.

Do not penalize the resource for covering additional modes or service types if it still helps answer the question.

Focus on semantic usefulness rather than exact wording.

Keep the evaluation concise and objective.

OUTPUT FORMAT (STRICT):

Return ONLY the JSON object.

[

“score”: <integer between 0 and 10>,

“label”: “<relevant | irrelevant>“,

“justification”: “<1 to 3 sentences explaining the reasoning>“

]

References

- Shaheen, S.; Cohen, A. Similarities and Differences of Mobility on Demand (MOD) and Mobility as a Service (MaaS). Inst. Transp. Engineers. ITE J. 2020, 90, 29–35. [Google Scholar]

- Kummetha, V.C.; Concas, S.; Staes, L.; Godfrey, J. Mobility on demand in the United States—Current state of integration and policy considerations for improved interoperability. Travel Behav. Soc. 2024, 37, 100867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okunieff, P.E.; Brown, L.; Heggedal, K.; O’Reilly, K.; Weisenberger, T.; Guan, A.; Chang, A.; Schweiger, C. Multimodal and Accessible Travel Standards Assessment—Outreach Report; Intelligent Transportation Systems Joint Program Office: Washington, DC, USA, 2020.

- Zheng, O.; Abdel-Aty, M.; Wang, D.; Wang, Z.; Ding, S. ChatGPT is on the horizon: Could a large language model be suitable for intelligent traffic safety research and applications? arXiv 2023, arXiv:2303.05382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radford, A.; Narasimhan, K.; Salimans, T.; Sutskever, I. Improving language understanding by generative pre-training. 2018. in progress. Available online: https://cdn.openai.com/research-covers/language-unsupervised/language_understanding_paper.pdf (accessed on 24 November 2025).

- Dziri, N.; Milton, S.; Yu, M.; Zaiane, O.; Reddy, S. On the Origin of Hallucinations in Conversational Models: Is it the Datasets or the Models? In Proceedings of the 2022 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Tech-nologies, Seattle, DC, USA, 10–15 July 2022; pp. 5271–5285. [Google Scholar]

- Concas, S.; Kummetha, V.C.; Staes, L. Mobility Data—Standards and Specifications for Interoperability. Available online: https://www.transit.dot.gov/research-innovation/mobility-data-standards-and-specifications-interoperability-report-0267 (accessed on 9 August 2024).

- MobilityData. MobilityData Is Accelerating the Standardization of On-Demand Transportation with the GOFS Project. Available online: https://mobilitydata.org/mobilitydata-is-accelerating-the-standardization-of-on-demand-transportation-with-the-gofs-project/ (accessed on 12 March 2023).

- MaaS-Alliance. Interoperability for Mobility, Data Models, and API; MaaS-Alliance: Brussels, Belgium, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- OMF. OMF About MDS. Available online: https://www.openmobilityfoundation.org/about-mds/ (accessed on 3 March 2023).

- Teal, R.; Larsen, N.; King, D.; Brakewood, C.; Frei, C.; Chia, D. Development of Transactional Data Specifications for Demand-Responsive Transportation; The National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2020; p. 154. [Google Scholar]

- EN 12896-1; Public Transport—Reference Data Model—Part 1: Common Concepts. Comité Européen de Normalisation (CEN): Brussels, Belgium, 2016.

- Garcia, J.R.R.; van den Belt, E.; Bakermans, B.; Groen, T. Blueprint for an Application Programming Interface from Transport Operator to Maas Provider (TOMP-API)–Version Dragonfly; Ministry of Infrastructure and Water Management: The Hague, The Netherlands, 2020.

- Orrù, G.; Piarulli, A.; Conversano, C.; Gemignani, A. Human-like problem-solving abilities in large language models using ChatGPT. Front. Artif. Intell. 2023, 24, 1199350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damashek, M. Gauging Similarity with n-Grams: Language-Independent Categorization of Text. Science 1995, 267, 843–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liddy, E.D. Natural Langugage Processing; Syracuse University: Syracuse, NY, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Mikolov, T.S.I.; Chen, K.; Corrado, G.S.; Dean, J. Distributed representations of words and phrases and their compositionality. In Proceedings of the 27th International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems, Red Hook, NY, USA, 5–10 December 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Pennington, J.S.R.; Manning, C.D. Glove: Global vectors for word representation. In Proceedings of the 2014 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing (EMNLP), Doha, Qatar, 25–29 October 2014. [Google Scholar]

- OpenAI. OpenAI GPT-4o. Available online: https://platform.openai.com/docs/models/gpt-4o (accessed on 20 August 2025).

- Google. Google Gemini. Available online: https://gemini.google/assistant/ (accessed on 15 August 2025).

- Facebook. Llama. Available online: https://www.llama.com/ (accessed on 20 October 2025).

- Microsoft Copilot. Available online: https://www.microsoft.com/en-us/microsoft-365/copilot/try-copilot-chat (accessed on 20 October 2025).

- Nie, T.S.J.; Ma, W. Exploring the Roles of Large Language Models in Reshaping Transportation Systems: A Survey, Framework, and Roadmap. Artif. Intell. Transp. 2025, 1, 100003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devunuri, S.; Lehe, L. TransitGPT: A Generative AI-based framework for interacting with GTFS data using Large Language Models. Public Transp. 2024, 17, 319–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mumtarin, M.; Chowdhury, M.S.; Wood, J. Large Language Models in Analyzing Crash Narratives—A Comparative Study of ChatGPT, BARD and GPT-4. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2308.13563. [Google Scholar]

- Devunuri, S.; Qiam, S.; Lehe, L. ChatGPT for GTFS: Benchmarking LLMs on GTFS Understanding and Retrieval. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2308.02618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OpenAI. OpenAI API. Available online: https://platform.openai.com/docs/overview (accessed on 13 May 2025).

- OpenAI. Prompt Engineering Guide. Available online: https://platform.openai.com/docs/guides/prompt-engineering (accessed on 13 May 2025).

- OpenAI. OpenAI Text-Embedding-Ada-002. Available online: http://platform.openai.com/docs/models/text-embedding-ada-002 (accessed on 20 August 2025).

- Kukreja, S.K.T.; Bharate, V.; Purohit, A.; Dasgupta, A.; Guha, D. Vector Databases and Vector Embeddings—Review. In Proceedings of the 2023 International Workshop on Artificial Intelligence and Image Processing (IWAIIP), Yogyakarta, Indonesia, 1–2 December 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis, P.; Perez, E.; Piktus, A.; Petroni, F.; Karpukhin, V.; Goyal, N.; Küttler, H.; Lewis, M.; Yih, W.T.; Rocktäschel, T.; et al. Retrieval-Augmented Generation for Knowledge-Intensive NLP Tasks. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2005.11401. [Google Scholar]

- MongoDB, Inc. MongoDB Official Website. Available online: https://www.mongodb.com/ (accessed on 13 June 2025).

- Porter, S. Understanding Cosine Similarity and Word Embeddings. Available online: https://spencerporter2.medium.com/understanding-cosine-similarity-and-word-embeddings-dbf19362a3c (accessed on 18 May 2025).

- Sankey-Diagrams. Sankey-Diagrams-Tags. Available online: https://www.sankey-diagrams.com/tag/distribution/ (accessed on 22 July 2025).

- Services, A.W. What Is Prompt Engineering? Available online: https://aws.amazon.com/what-is/prompt-engineering/ (accessed on 4 July 2025).

- Ahmed, S.K. How to Choose a Sampling Technique and Determine Sample Size for Research: A Simplified Guide for Researchers. Oral Oncol. Rep. 2024, 12, 100662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Federal Transit Administration. 2024 National Transit Summaries and Trends; Federal Transit Administration: Washington, DC, USA, 2024.

- Liu, Q.; Wang, W.; Willard, J. Effects of Prompt Length on Domain-specific Tasks for Large Language Models. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2502.14255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, L.S.Z.; Idnay, B.; Nestor, J.G.; Soroush, A.; Elias, P.A.; Xu, Z.; Ding, Y.; Durrett, G.; Rousseau, J.F.; Weng, C.; et al. Evaluating large language models on medical evidence summarization. npj Digit. Med. 2023, 6, 158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demir, M.M.C.; Abdullah, M. Validate Your Authority: Benchmarking LLMs on Multi-Label Precedent Treatment Classification. In Proceedings of the Natural Legal Language Processing Workshop 2025, Suzhou, China, 8 November 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Li, H.X.T.; Chang, E.; Wen, Q. Knowledge Tagging with Large Language Model based Multi-Agent System. Proc. AAAI Conf. Artif. Intell. 2024, 39, 28775–28782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Liang, Y.; Meng, F.; Sun, Z.; Shi, H.; Li, Z.; Xu, J.; Qu, J.; Zhou, J. Is ChatGPT a Good NLG Evaluator? A Preliminary Study. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2303.04048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiang, C.-H.L.; Hung, Y. Can Large Language Models Be an Alternative to Human Evaluations? arXiv 2023, arXiv:2305.01937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, J.; Ng, S.K.; Jiang, Z.; Liu, P. GPTScore: Evaluate as You Desire. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2302.04166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OpenAI. GPT-4 Technical Report; OpenAI: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- OpenAI. OpenAI API Pricing. Available online: https://platform.openai.com/docs/pricing (accessed on 20 August 2025).

- Xu, Z.; Jain, S.; Kankanhalli, M. Hallucination is Inevitable: An Innate Limitation of Large Language Models. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2401.11817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guu, K.; Lee, K.; Tung, Z.; Pasupat, P.; Chang, M. REALM: Retrieval-Augmented Language Model Pre-Training. In International Conference on Machine Learning; PMLR: Birmingham, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- OpenAI. OpenAI Web Search. Available online: https://openai.com/index/introducing-chatgpt-search/ (accessed on 19 November 2025).

- Rose, S.W.; Borchert, O. Zero Trust Architecture; NIST: Gaithersburg, MD, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- McMahan, B.; Moore, E.; Ramage, D.; Hampson, S.; Arcas, B.A. Communication-Efficient Learning of Deep Networks from Decentralized Data. In Artificial Intelligence and Statistics; PMLR: Birmingham, UK, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Ko, R. The Beginner’s Textbook for Fully Homomorphic Encryption. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2503.05136. [Google Scholar]

- Yenugula, M.; Kasula, V.K.; Yadulla, A.R.; Konda, B.; Addula, S.R.; Kotteti, C.M.M. Privacy-Preserving Decision Tree Classification Using Homomorphic Encryption in IoT Big Data Scenarios. In Proceedings of the 2025 IEEE 4th International Conference on Computing and Machine Intelligence (ICMI), Mount Pleasant, MI, USA, 5–6 April 2025; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Khder, M.A. Web Scraping or Web Crawling: State of Art, Techniques, Approaches and Application. Int. J. Adv. Soft Comput. Its Appl. 2021, 13, 145–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |