1. Introduction

Supercapacitors, also known as ultracapacitors or electrochemical capacitors, are an advanced class of devices for the short-term storage of electrical energy. They combine the properties of classic capacitors and batteries, offering very high power density with moderate energy density. Unlike batteries, in which energy is stored through chemical reactions, supercapacitors store energy through a physical process, the formation of an electrical double layer at the electrode–electrolyte interface (Electric double layer Capacitor, EDLC) or through a pseudo-capacitance phenomenon associated with reactions at the electrode surface [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6].

The use of nanostructured carbon materials, such as activated carbon (for example, biomass), graphene, or carbon nanotubes, as well as modern oxide materials and conductive polymers, allows for a much larger active surface area and improved electrochemical performance to be achieved [

7,

8]. As a result, modern supercapacitors are characterised by high energy efficiency, long life (more than one million charge–discharge cycles), and wide temperature operating range.

Due to their properties, supercapacitors find applications in a wide range of technical areas—from electromobility (e.g., energy recovery systems in hybrid vehicles), to voltage stabilisation in emergency power systems, and to energy storage in microscale and macro-scale renewable-based systems. Contemporary research is focussing on the development of hybrid systems that combine the advantages of batteries and supercapacitors, which could be the key to increasing the efficiency and durability of future energy storage systems.

Supercapacitors are currently being implemented in braking energy recovery (regeneration) systems, acceleration support, and in the so-called hybrid energy storage systems (HESS), where they work together with lithium-ion batteries. Hybrid battery-supercapacitor systems improve the ability to deliver maximum power, reduce battery loads (extending battery life), and increase efficiency during rapid load changes [

9,

10,

11].

With fast response times and thousands to millions of cycles, supercapacitors are used as buffer sources in UPS, emergency power systems (e.g., to maintain voltage during short interruptions), in medical devices requiring short, reliable power supplies, and in consumer electronics requiring fast charge/discharge [

12,

13].

In photovoltaic and wind installations, supercapacitors are used to reduce short-term power fluctuations, improve power quality, provide ride-through during temporary disturbances and support frequency regulation in microgrids. Due to their instantaneous response, they are suitable for applications requiring rapid power injection or absorption, although they rarely store energy long-term by themselves—they more often act as support elements in hybrid storage systems [

14,

15,

16,

17].

Supercapacitors are also playing an increasingly important role in measurement systems, where their role is reduced to providing instantaneous energy to read values measured by sensors of various physical quantities [

18,

19].

This article refers to the Authors’ already published studies, the subject of which was to investigate the possibilities and develop a power system for a semi-passive RFID tag (system enabling the marking or identification of objects using RFID technology) [

20,

21]. A special feature of this study was the lack of power supply from an external source and the implementation of the possibility of obtaining the energy necessary for the correct operation of such a system from external common systems and/or from the reader-programmer of the RWD (Read–Write Device) RFID system. One of the basic analysed problem was the efficiency of the process of obtaining this energy, its conditioning in order to obtain parameters sufficient to ensure the operation of the RFID target system (voltage of the storage, obtainable current, etc.).

The essence of this study is a comprehensive examination of the properties of commercially available supercapacitors as one of the basic alternatives proposed for the implementation of a central energy storage facility. At the same time, the supercapacitor and its parameters determine the scope of possibilities for limiting the implementation of the energy storage system itself due to the need to protect these components from exceeding the permissible operating voltage and to balance the voltages on individual components of the supercapacitor batteries used to maximise the storage capacity. The article presents the results of an analysis of the possibilities of using modern supercapacitors as the main element of an energy storage and conditioning system for the proposed concept of such a system.

2. Energy Conditioning System Concept

The concept referred to by the authors in the following section is a certain general solution to the problem, independent of specific electronic components. The selection of specific circuits (microprocessor, memory, sensors, identifier chip, etc.) imposes certain requirements and possibilities in terms of the voltage present in the circuit, power consumption, etc., which consequently leads to the determination of energy considerations and imposes an appropriate approach to solving the energy conditioning problem. The system should also have a flexible interface for connecting different sensors, which also generates a certain number of requirements that need to be taken into account.

The operation of the entire identifier system is controlled by a low-power microcontroller. It decides when to carry out measurements, operates the sensors, stores data in non-volatile memory, and implements operating scenarios. The type of microcontroller used also decides which data exchange interfaces will be available to support the sensors and other identifier circuits (e.g., memory). The use of additional circuits to support a specific interface does not make sense energetically and especially geometrically. The best solution is to use a microcontroller that has the required interfaces, which, given the current market offerings, is not a problem.

The used sensors can be anything that meets three conditions: an interface compatible with the one present in the identifier circuit, a supply voltage within the range available in the circuit and a power consumption that allows the correct operation scenario to be carried out. It is advisable to choose a sensor for the measurand in question that supports the required measurement range, meets the above requirements and at the same time has the lowest power consumption of those available.

The ‘integrating’ element of the above components is the energy conditioner, whose task is to store the energy harvested by the harvester system and convert it to the form required by the individual electronics (

Figure 1).

The question of antennas used and the design of their matching and energy harvesting circuits is an independent aspect of the research and has been addressed in previous studies. The identifier’s ability to operate autonomously largely depends on the parameters of the harvester and the amount of energy recovered, the conditioner and the losses associated with energy storage and processing, the circuits used and the energy they consume, and the tasks faced by the system and the methods used to solve them. Three possible scenarios for the operation of the identifier depending on the efficiency of the energy conditioner are presented in

Figure 2.

The energy harvester system operates when the field strength exceeds the minimum value Emin. Then, there is a voltage Vout at the output of the harvester system with a value that depends on the electromagnetic field strength E, the load on the harvester system and the system construction. It is then also possible to operate the harvester systems at specific intervals determined by the functionality of the system. Failure to meet the Emin condition blocks the operation of the system (casual partially operation). The use of energy storage introduces new possibilities. Then two cases can be analysed (cyclical operation). The first, when the stored energy is too low (Vc < Vpmin before E > Emin) and the identification circuit loses the ability to determine the time elapsed on its own. The second is when the harvester system is able to charge the capacitor with enough energy to operate the identifier system (Vc > Vpmin) during the time when there is no energy recovery from the electromagnetic field, until the condition E > Emin is met. Then the possibility of continuity of identifier operation (including the possibility of correct measurement and/or time recording) appears.

Extremely important from the perspective of the final effects of the identifier system, the specificity of energy storage in the analysed system requires a broader multi-criteria analysis. The element responsible for this function can be a capacitor or supercapacitor, as other solutions, due to the supply and efficiency of energy harvesting from the mentioned sources, do not meet the basic assumptions.

The basic criterion is capacitance, i.e., the ability to store a certain energy at a given voltage. A capacitor is not a high-capacity component, which means that it is not able to store much energy, allowing long autonomous operation. In the case of a short time of power supply from an electromagnetic field, it is able to rapidly accumulate energy with sufficient voltage to start the microprocessor chip and carry out specified actions, but the disappearance of the field causes it to quickly discharge and the system becomes inactive. Supercapacitors have many times higher capacitance (several farads compared to microfarads in conventional capacitors), which allows to store a significant amount of energy in the event of long-term energy recovery. The problem is the field occurring on a short-term basis, when the supercapacitor’s considerable capacitance does not allow the system to quickly reach the correct voltage value and start up. However, this problem can be reduced by using appropriate circuit solutions.

One of the most important criteria for micropower systems is leakage current.

Table 1 shows a comparison of several selected capacitors of different types.

The ceramic capacitor has the lowest leakage current. Only such capacitors for small capacitances with a dielectric, e.g., type NP0, should be used in the designed circuit. Of course, a parallel connection of capacitors can also be used, but with a circuit of, e.g., 100 × 100 µF = 10 mF, there will be a leakage current comparable to that of a supercapacitor with a capacitance about 250 times larger with a much larger storage size. The time dependence of the leakage current of selected supercapacitors is illustrated in

Figure 3.

There is a lack of data in the literature on the leakage current in the first seconds, minutes, and hours of discharging a supercapacitor, as well as in cases of charging it with varying currents to different voltage values from the operating range. These are very important characteristics, especially in terms of the analysed system.

The voltage occurring in the identifier circuit is about a few volts, which for a capacitor is not a problem, while for a supercapacitor it can be a source of problems. In the case of a capacitor, an increase in voltage will possibly result in the need to select an element with a higher maximum voltage, which causes, among other things, its larger size. In the case of a supercapacitor, typically the maximum operating voltage is around 2–3 V. Higher voltages require such elements to be connected in series and additionally, due to the significant tolerance of supercapacitor parameters, the use of a circuit for balancing the voltages on individual supercapacitors in a battery built in this way (a so-called balancer). The use of this circuit is associated with an increase in self-discharge current for all energy storage.

The use of a single supercapacitor in the designed identifier generates another problem. Since the voltage value at the output of the energy recovery system is in the range of 1.7–4.5 V, this results in the need to build a circuit to protect the supercapacitor from destruction, which introduces significant energy losses. A better solution is to use a series connection of, for example, two supercapacitors to achieve a maximum voltage of approximately 5 V. Of course, it is necessary to use an active balancer circuit. If supercapacitors with an internal balancer with a total leakage current lower than that of the externally compensated solution were available, their use would simplify the electronic circuit of the identifier. At the moment, no such solutions are available, especially for such energy-critical applications, so the use of an active external balancer circuit was considered during the study.

3. Determining the Leakage Current of Supercapacitors

Supercapacitors are the most promising in terms of their ability to operate as energy storage for the model RFID tag system. The value of the

EN energy stored by a supercapacitor can be expressed by the formula:

where

C is the capacitance of the capacitor and

U is the voltage value between the terminals of the supercapacitor. Furthermore, supercapacitors can be charged very easily and do not require additional special circuits for this purpose.

However, when a suitable supercapacitor is selected for use as an energy store, the properties of the supercapacitor must be carefully analysed. The aim is to fit this element into the overall circuit in such a way that the energy can be stored in this element as efficiently as possible and can be used to power identifier circuits.

There are a wide variety of supercapacitors available on the market with varying capacitances and voltage ratings. A very big disadvantage of this element is the high energy loss during operation; its leakage can reach high values. Hence, this issue from the point of view of using a supercapacitor as an energy storage element needs to be analysed in more detail. Therefore, in this study, investigations of phenomena associated with the practical treatment of the leakage effect of these capacitors were carried out. A test stand was built to carry out the tests described above (

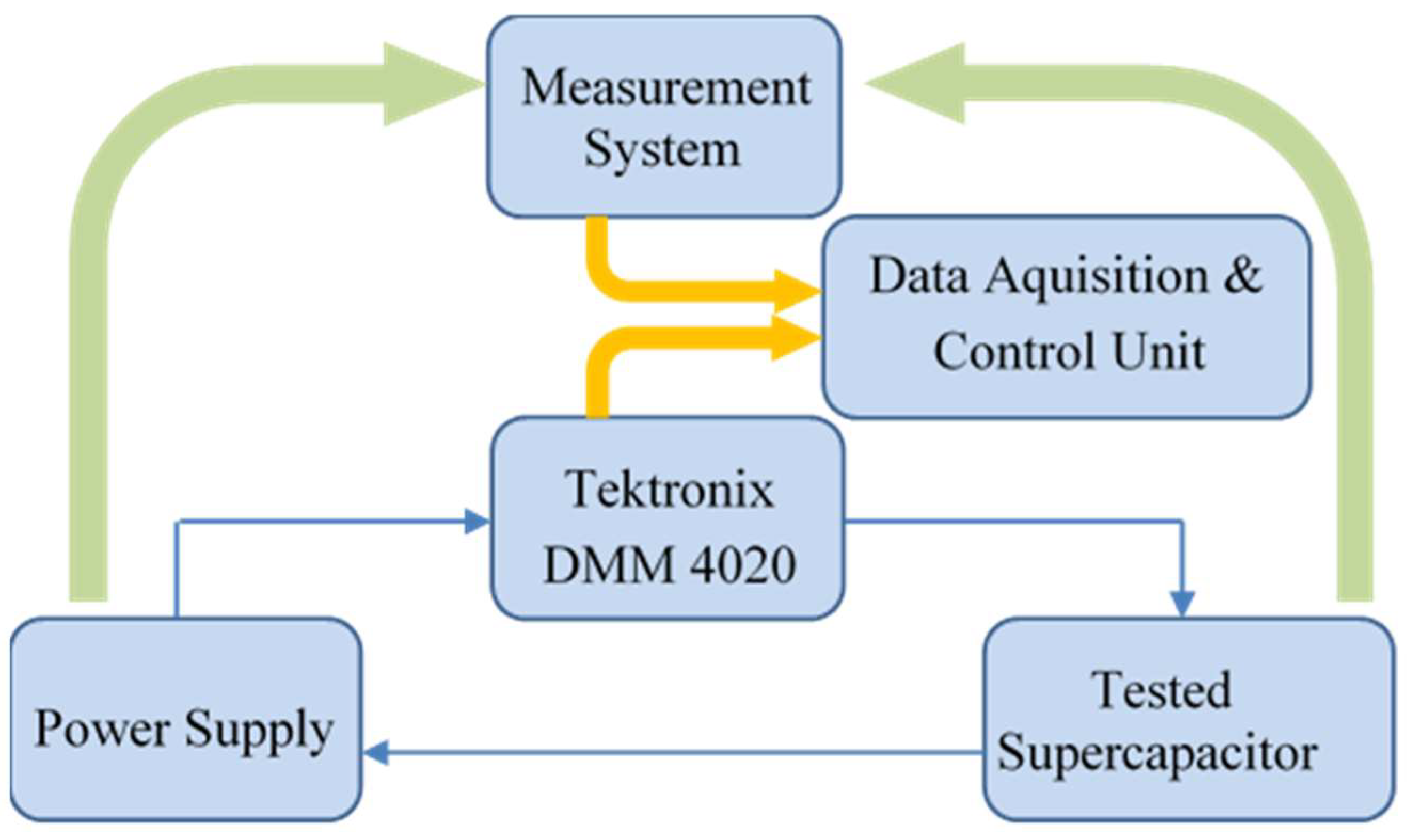

Figure 4).

The test stand consists of the following components:

- (1)

Charging system:

a regulated power supply;

a current source enabling the supercapacitor under test to be charged with a constant value current;

a control system (consisting of a parallel port emulator and a current source relay control system), which allows the current source to be controlled using a computer;

- (2)

A measurement system:

Instrument amplifier circuit including power supply—thanks to the very high input resistance of the instrument amplifiers used as the input stage of the measurement system, the influence of the measurement system on the parameters of the capacitors under test can be minimised;

Tektronix DMM 4020m (Beaverton, USA) for measuring the leakage current of the supercapacitor under test;

NI PXI 5122 measuring module from National Instruments (Austin, TX, USA);

- (3)

The control and data acquisition system, which was a PXI computer from National Instruments.

The control of the conducted tests and the acquisition of measurements were realised through programmes written using the LabVIEW 2019 environment according to the functional diagram shown in

Figure 5.

Several commercially available supercapacitors from different manufacturers with different parameters were used for the research. These are generally supercapacitors consisting of two cells connected in series. The investigated Cellergy supercapacitors are single-cell supercapacitors. All supercapacitors tested and their parameters are given in

Table 2.

A very important aspect of the correct selection of a supercapacitor for use in the design circuit is the determination of the leakage current value of this component. In most cases, when supercapacitors are used in various types of system, this parameter is of little importance because supercapacitors are intermediate energy storage devices and the values of the currents at which they operate are generally high. Hence, the values of their internal leakage currents are neglected. For this reason, in the catalogue notes of supercapacitors available on the market, information regarding their leakage is very poor. In their product documentation, supercapacitor manufacturers usually quote leakage currents under stable conditions after a certain period of time. The length of this time is usually 72, 96 or even 120 h after charging to nominal voltage. Materials that give some characteristics of the leakage current can be found, but these are relatively few [

22,

28]. There is also a lack of accurate information on the leakage current values of supercapacitors in the first seconds, minutes, and hours after the supercapacitor starts charging or self-discharging.

For the design of systems with energy harvesting from an inefficient source, information on the leakage current values in the initial phase of the supercapacitor charging process is very important. In the case of a bad selected supercapacitor, or if certain behaviours of the supercapacitor under different operating conditions are not taken into account, there may even be a situation where energy is recovered all the time, but all of it is only transferred to cover the supercapacitor’s own losses.

The two PowerStor PB-5R0V104-R supercapacitors were tested. For this purpose, a measuring system was built (

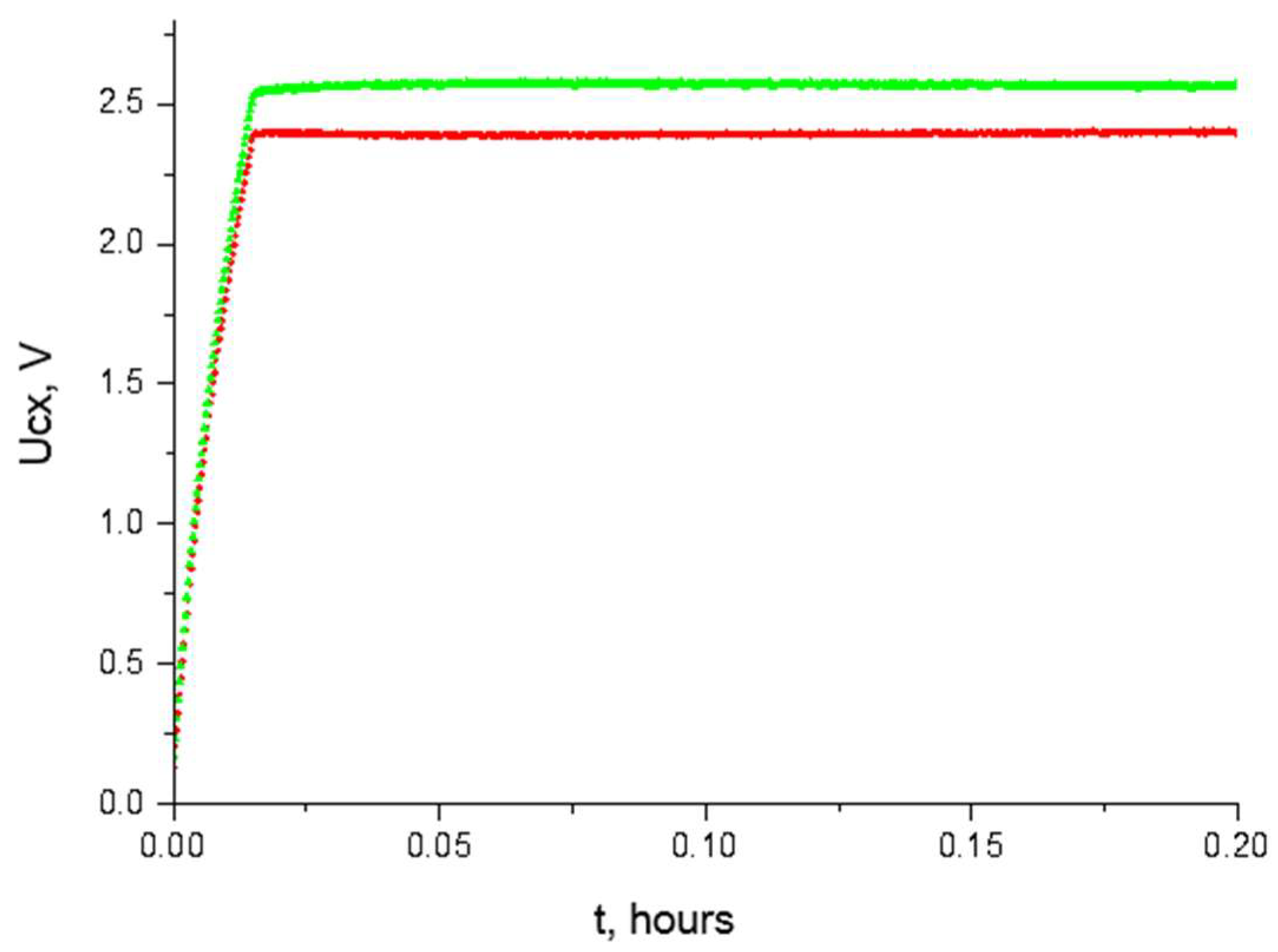

Figure 5). The tests consisted in charging the supercapacitors to a nominal voltage, disconnecting them from the power source, and then recording changes in the voltage level during the self-discharge process. Measurements were recorded over a period of more than 72 h. The time range adopted for recording the self-discharge process was based on the leakage current information provided in the catalogue data for the selected supercapacitor. According to the manufacturer’s data, the leakage current of the PowerStor PB-5R0V104-R supercapacitors should not exceed 3 µA after a time of 72 h. The supercapacitors used to carry out the tests were initially fully discharged. The results of the measurements are shown in

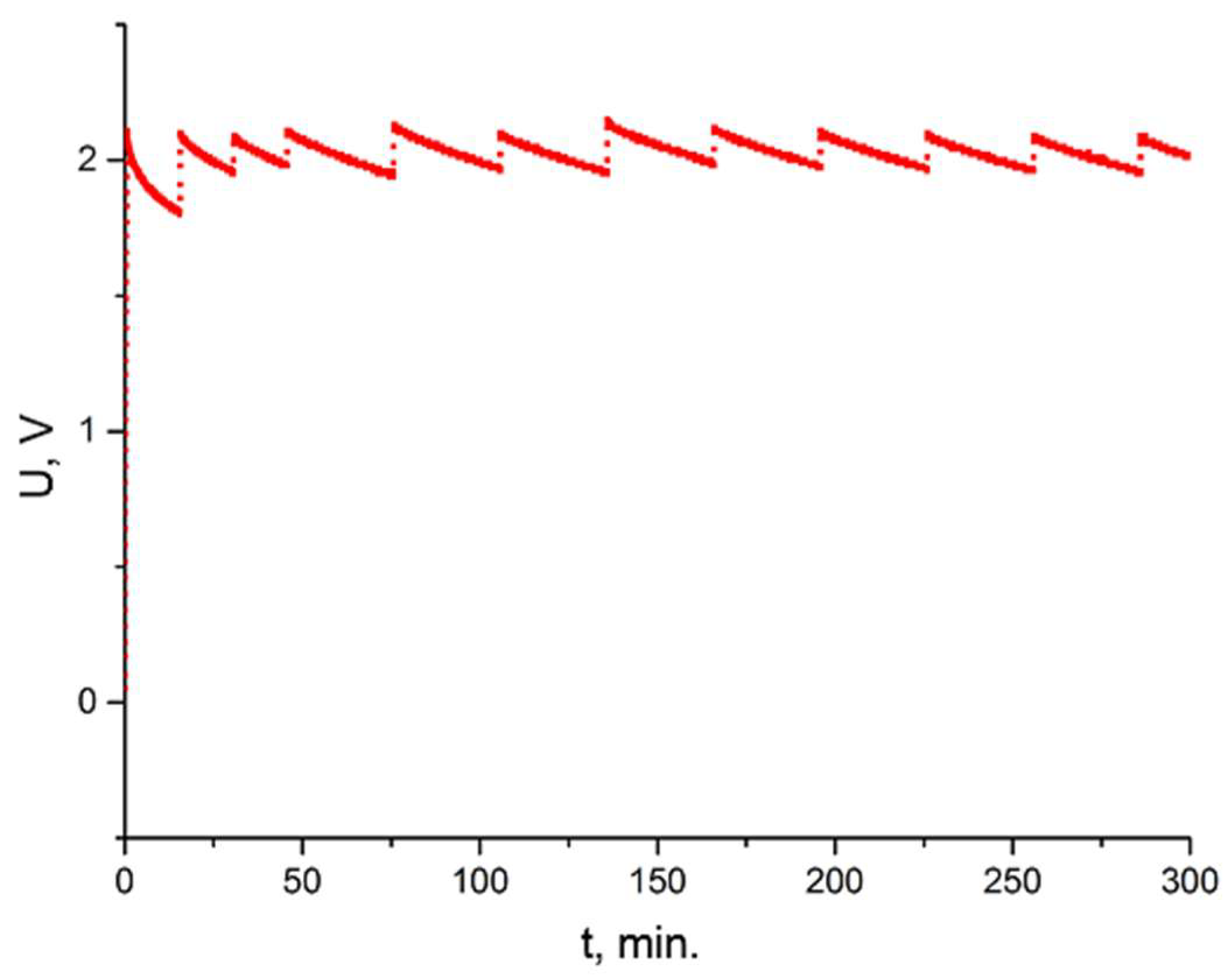

Figure 6.

From the obtained self-discharge characteristics of the tested supercapacitors (

Figure 6, waveforms 1 and 2), it can be seen that in the first minutes there is a very sharp drop in the measured voltage at their terminals, i.e., there will be high energy losses in the first phase of self-discharge. On this basis, it is difficult to directly determine the leakage current values of the tested supercapacitors. The only way to do this is to carry out mathematical calculations. Comparing the results, it can be concluded that the leakage current of a supercapacitor is more influenced by the charging method (

Figure 6—curves 1, 3 and 4) than by the technological dispersion of parameters (

Figure 6—curves 1 and 2).

For this purpose, a two-branch electrical model of the supercapacitor was adopted (

Figure 7). This is a simplified model and the results obtained may to some extent differ from reality, but it is very often used in the available literature and allows a fairly accurate representation of a supercapacitor in an electrical circuit. If more accurate calculations were to be made, complex and sometimes very tedious simulations would have to be used for this purpose, taking into account the complex nature of the supercapacitor’s internal structure, which would take into account any phenomena resulting from its construction and manufacturing technology (e.g., DRC lines).

In this model, the capacitance of a supercapacitor

C1 is a combination of two parallel capacitances—

C0, with a fixed value, and

CV, with a value depending on the voltage

at the electrodes of the capacitor:

where

kv is the technology factor,

UP is the voltage at the terminals of the supercapacitor.

The adopted supercapacitor electrical model contains two paths, which are responsible for modelling the fast (R1C1) and slow (R2C2) states, respectively. The other elements are the parallel resistance Rp that models the leakage resistance of the supercapacitor and the inductance of the leads L (which is not significant in the frequency range used in the carried out analysis).

Based on this model, a calculation algorithm was developed using MATLAB/Simulink ver. R2024b (

Figure 8), which was used in a further stage of the work to determine the leakage current values and their dependence on the voltage value at the supercapacitors’ terminals. In order to improve the convergence of the calculations with the observed actual measurement results, the resistance R2 and capacitance C2 values were also made dependent on the recorded voltage values. The calculation results in the form of characteristics are presented in

Figure 9 and

Figure 10.

The leakage current values obtained from the calculations in the first minutes of self-discharge reach very high values, reaching up to 400 µA. In addition, there is a very high dependence of the leakage current value on the voltage value at the supercapacitor terminals. Leakage currents reach high values in the first stage of self-discharge when the voltage when the supercapacitor is charged to its rated voltage of 5 V is still above 4 V (

Figure 10). Furthermore, as shown in

Figure 9., the leakage current values obtained after a self-discharge time of 72 h are approximately 2 µA (the leakage current value according to the catalogue data after 72 h of self-discharge should not exceed 3 µA), which confirms the accuracy of the calculations.

In order to analyse the self-discharge under different initial operating conditions, two more self-discharge measurements were carried out, whereby in the first case, before recording the self-discharge process, the supercapacitor under test was connected to a 5 V power source and kept in this state for about 4 h. The voltage was then disconnected, and the recording of the self-discharge process started. In the next step, the same supercapacitor was completely discharged and once again charged to 5 V. In this case, the power supply was continuously connected to the terminals of this supercapacitor for about 6 h. After this time, the voltage was disconnected and the self-discharge recording process started again. The characteristics obtained by recording the voltages in both cases are presented in

Figure 11 for comparison with those obtained by recording the self-discharge process discussed earlier. The supercapacitor was charged to its rated voltage and disconnected when this voltage was reached, a 4 h pre-charging for the case in which the supercapacitor under test was held at 5 V prior to the start of the self-discharge process, and a 6 h pre-charging for the case in which the supercapacitor under test was held at 5 V prior to the start of the self-discharge process, and a 6 h pre-charging for the case in which the supercapacitor under test was held at 5 V for the indicated time.

Analysing the obtained measurement results, it can be seen that the state of charge has a very strong influence on the values of the internal leakage currents, which in turn is related to the rate of energy loss in the supercapacitor. The longer the supercapacitor under test has been connected to the power source, the lower the determined values of the leakage current in the initial phase, the faster the internal transients are stabilised (

Figure 11a), and consequently the smaller the voltage changes in the initial phase of self-discharge. This leads to reduced energy losses in the supercapacitor (

Figure 11b). It can be seen from the energy variation diagram for the three cases analysed that after the first hour of self-discharge, the energy determined for the initial charge of 4 h was approximately 30% higher, while the determined energy for the 6 h initial charge was about 38% higher than for the direct self-discharge. In contrast, after 8 h of self-discharge, an increase in energy of about 43% can be observed for the 4 h pre-charge and an increase of about 59% for the 6 h pre-charge. After a self-discharge time of 40 h, the proportions changed slightly. For the 4 h pre-charging, the determined energy was about 30% higher, while for the 6 h pre-charging, the increase in energy compared to the value determined for direct self-discharge was about 48%.

The phenomenon of internal conditions formation in a supercapacitor is also confirmed by another research approach. It may happen under real operating conditions that a supercapacitor used as storage can be discharged with a very low current and then recharged to a certain voltage without exceeding this voltage value, if only for safety reasons. Such simulations were also carried out on exemplary supercapacitors using a circuit, the ideas of which are shown in

Figure 5. The following figures show exemplary characteristics obtained by charging a supercapacitor with constant current up to a certain voltage and discharging it through a self-discharge process. In this way, both single-cell supercapacitors (Cellergy CLC03P025F12—

Figure 12) and supercapacitors with two cells connected in series (Murata DMF 474M—

Figure 13 and CapXX HW209—

Figure 14) were tested. The results of realised tests on one of the PowerStor PB-5R0V104-R supercapacitors are presented in

Figure 15. In addition to the continuous charging process, a dynamic voltage change from 1 V to 4 V (green curve), from 2 V to 4 V (red curve) and from 3 V to 4 V (blue curve), which occurred at the same time (ca. 43 min. of charging process) during the realised test, was additionally made. All tested supercapacitors were discharged prior to measurements. In each of the cases, it can be seen that in the first phase after charging the energy loss is high (voltage drop on discharge). Subsequent cycles shape the internal conditions of the supercapacitors, and thus the energy loss on discharge is increasingly smaller.

Figure 15 also shows that a change in the operating conditions of the supercapacitor (dynamic change in the value of the voltage to which it has been charged) also generates correspondingly higher values of leakage current in the first stage immediately after switching (depending on the value of the voltage before switching), which successively decrease during continuous recharging.

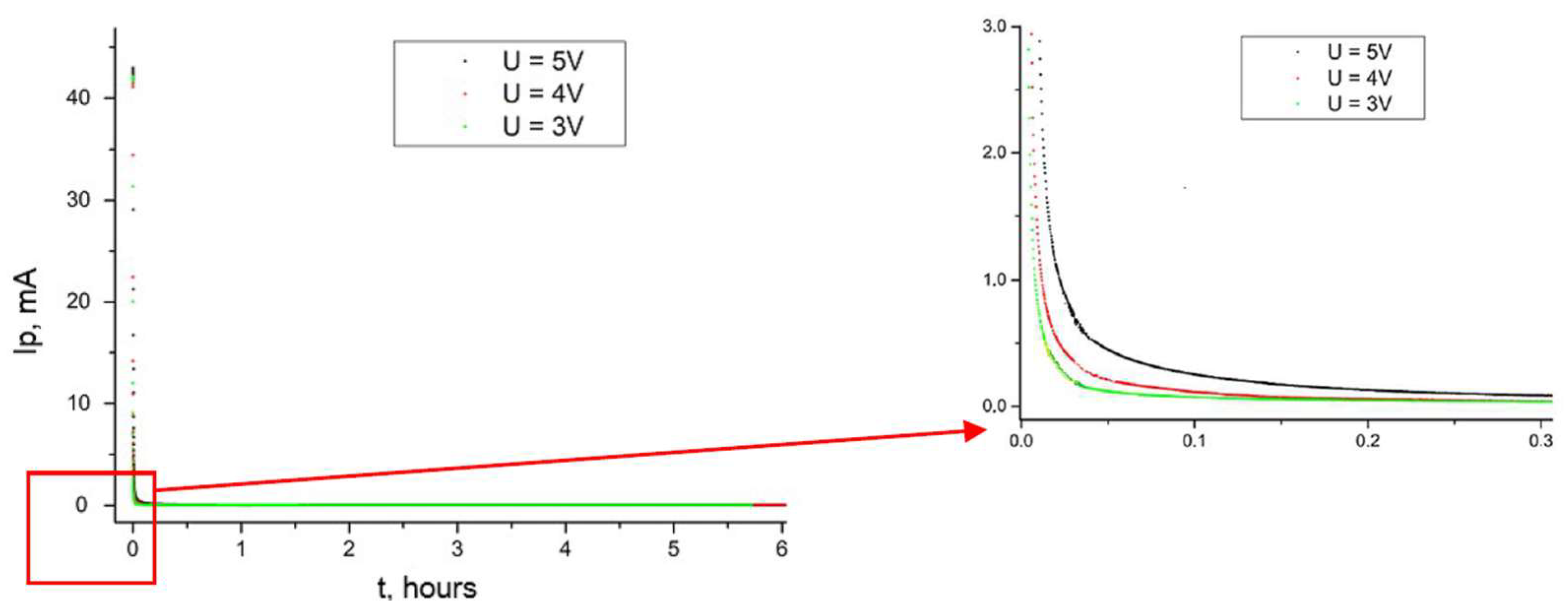

The tests described above are used in situations in which the voltage values at the terminals of the tested supercapacitors were recorded, while the current values were determined indirectly using a mathematical calculation model. In the next step, tests were carried out to directly measure the value of the current flowing through the supercapacitor under test. All supercapacitors under test were fully discharged prior to measurement. Measurements were made using the measuring system shown in

Figure 16.

During the measurements in this case, the supercapacitor under test was connected to a power source with a specific voltage value during the course of the entire measurement. The current flowing in the circuit was measured with a Tektronix DMM4020 multimeter (Beaverton, OR, USA). A National Instruments computer equipped with measurement cards was used to archive the measurement data under the LabView 2019 programme.

Figure 17 shows the results of testing the PowerStor PB-5R0V104-R supercapacitor at different voltages applied to the terminals of this supercapacitor. For comparison of the different supercapacitors, the current values recorded during the tests are shown in

Figure 18 and

Figure 19. It can be seen that, in the first minutes after the rated voltage is applied to the terminals of the tested supercapacitors, the measured currents have very high values. For all supercapacitors with a rated voltage of 5 V (independent of the supercapacitor’s capacitance value), the currents measured in the first seconds of charging exceed 40 mA. In the case of supercapacitors where a voltage of 3 V was applied to the terminals (PowerStor PB-5R0V104-R supercapacitors and Cellergy CLC03P025F12 supercapacitors), the recorded currents in the first seconds of charging also had high values, even reaching around 40 mA. The situation was different for the Cellergy CLC03P012F12 supercapacitor. The current value in this case was only about 3 mA. In each of the cases analysed, for the different supercapacitors at different charging voltages, the currents reached high values in the first phase of the process. Over time, they stabilised to values of a single µA. Depending on the type of measured supercapacitor or the value of the voltage applied to the terminals, this time had different values. As can be seen from the characteristics, the magnitude of the voltage applied to the terminals of the supercapacitors tested largely influenced the rate of stabilisation of the leakage current. The lower the voltage value, the faster the supercapacitor was able to charge, resulting in a faster termination of transient processes and stabilisation of the current. The rate of stabilisation of the leakage current value in the supercapacitor was also strongly influenced by the value of the supercapacitor’s capacitance and the type of materials used in its construction. Based on a comparison of the current characteristics of supercapacitors connected to a voltage of 3 V, it can be concluded that the current flowing through the capacitor with the smallest capacitance value was the fastest to stabilise. In contrast, when comparing supercapacitors connected to a voltage of 5 V, the capacitance values do not play a role in stabilising the current value as the type of materials used to build the supercapacitors.

On the basis of the analysis of the results presented, it can be concluded that prolonged prior charging of the supercapacitor causes some formation of the supercapacitor’s internal structure. Phenomena occur that counteract the significant loss of energy as a result of the self-discharge process. It is therefore preferable, when using a supercapacitor in an identifier, to charge it for a long time and to keep it as charged as possible for as long as possible. Furthermore, it can be observed that the better the supercapacitor that would be used to store the acquired energy, the more stable the internal conditions are, which in turn improves its energy properties. It is also important to select a suitable supercapacitor and the voltage value to which it will be charged during operation, as this affects the rate at which transient processes disappear and thus the energy conditions of the entire system with an integrated supercapacitor.

4. Balancing Voltage Variations in Supercapacitor Systems

When analysing the properties of supercapacitors with a view to their use as energy storage in the ID to be created, attention should be drawn to another disadvantage of these elements, namely the non-uniformity of charging of the series-connected component cells of the supercapacitor. It should also be noted that this negative phenomenon does not necessarily occur in every case when two supercapacitors are connected in series (or in a two-cell capacitor) but should nevertheless also be taken into account in general considerations. In the course of the tests, this was evident in both the charging and self-discharge processes of the supercapacitors (

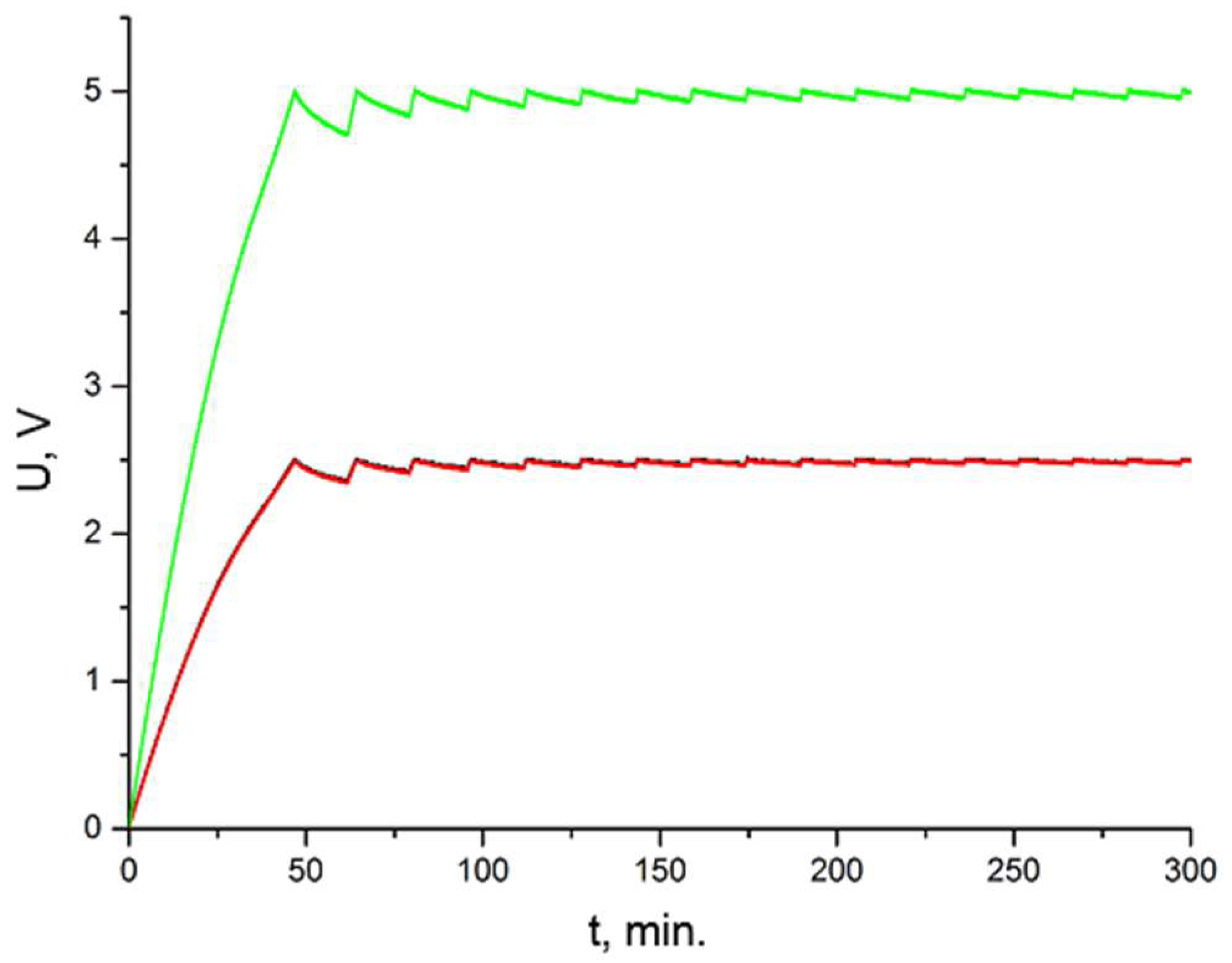

Figure 14), as well as when charging the tested supercapacitors with a constant voltage value (

Figure 20).

In both cases, it can be seen that the voltages of the individual component cells of the supercapacitor differ, and they are charged to different voltage levels. This state is very unfavourable. If the voltage on one of the cells were to rise above the rated value, damage would occur to that cell, and as a result, the entire series connexion would malfunction. Similarly, different leakage currents of capacitors charged to different voltages would prevent or hinder the effective operation of such storage.

The available literature describes circuits for balancing the distribution of voltages in individual sections of the supercapacitor battery built on the basis of operational amplifiers (

Figure 21), which effectively protect against excessive differences between the voltages in individual supercapacitors (or component cells of the supercapacitor battery).

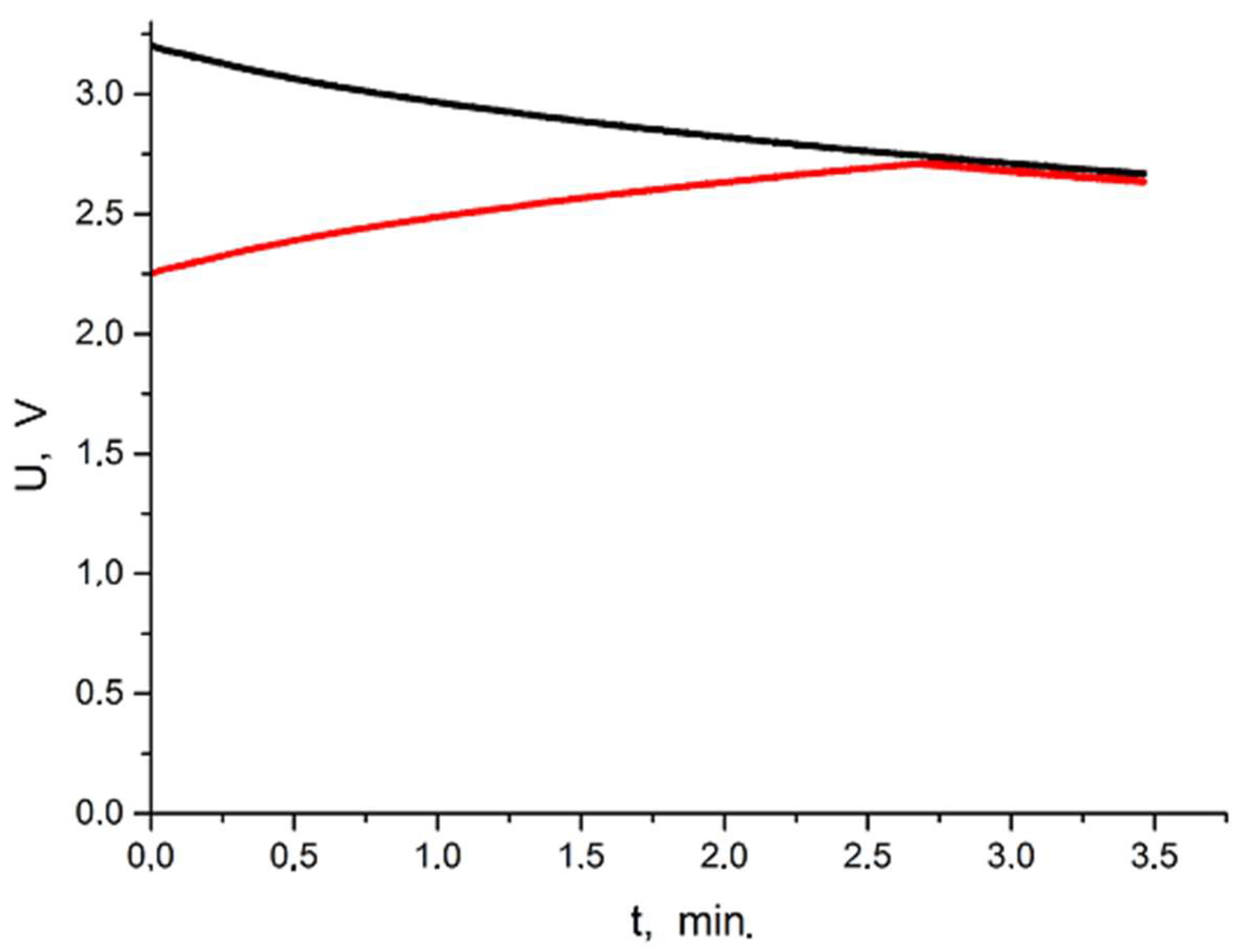

Figure 22 shows a laboratory system with two supercapacitors under test connected in series with the active balancer circuit attached. The recorded voltage waveforms of the individual component cells of such a series connexion as a result of the activation of the active balancer circuit is shown in

Figure 23. In the simulations of the balancer system, two in series connected supercapacitors were charged at different voltages. One was charged to 3.4 V, while the other was charged to 2.5 V. The balancer used resulted in an equalisation of the voltages of the two connected supercapacitors. One supercapacitor was charged, while the other was discharged, until the two voltages were equalised. Once the two voltages were equalised, simultaneous discharge of both supercapacitors took place because of the leakage currents of these supercapacitors augmented by the small leakage of the balancer.

The use of an active balancer circuit is able to protect a system of two supercapacitors connected in series against the formation of an excessive difference between the voltages of the component cells. However, they will not protect such a combination of supercapacitors from the simultaneous rise in both voltages of these supercapacitors above an assumed safe value. For this purpose, a circuit consisting of two Triune Systems TS12001 ICs was proposed. This circuit, in addition to being able to protect the individual component cells of the supercapacitor series connection against excessive voltage variation, also protects against an excessive increase in the voltage of the individual cells and thus against supercapacitor damage due to overcharging.

A circuit diagram of the supercapacitor voltage control system built on the TS12001 circuit is shown in

Figure 24. SC1 and SC2 are equivalent circuits of real-world supercapacitors in an energy storage system. Resistors enable the simulation of the leakage current of individual components.

At the input of each stage of the circuit, there is a comparator that compares the voltage of the supercapacitor under control with a preset reference voltage value. If the voltage on the supercapacitor exceeds the reference voltage value, a key is switched on, which discharges the supercapacitor through an additional resistor to the reference value.

Figure 25 shows the simulation results of the presented voltage monitoring system for two supercapacitors connected in series. In the initial phase, both supercapacitors are charged simultaneously (key J1A is switched on). The voltage of both supercapacitors increases. When the value set as safe is exceeded, both keys K1 and K2 are switched on. To the self-discharge currents of the supercapacitors (simulated by additional resistors connected in parallel to the capacitors), additional discharge currents are added via resistors R3 and R5. Disconnection of the charging voltage takes place (key J1A is opened). The voltage on both capacitors drops to a safe value. When the safe values are reached, both keys K1 and K2 are opened. The voltage on both capacitors decreases due to self-discharge processes. At some point, an unexpected recharge of one of the component supercapacitors takes place (key J2A will be switched on). At the moment when the voltage that is considered safe is exceeded, the protection is switched on to prevent the safe value being exceeded. At another point in time, the second component cell of the series connection may be unexpectedly charged (key J3A will be switched on). Again, protection is in operation to prevent the safe value from being exceeded in an uncontrolled manner. As a result of this behaviour of the system, voltage imbalances may occur. Subsequent common charging of both component cells of the series connection is able to equalise on these cells. This is made possible by the independent operation of the two TS12001 circuits. In the simulation shown, it can be seen that the two circuits switch on at different times as required, allowing the whole system to operate correctly.

The two circuits, both the active balancer circuit and the two control circuits based on TS12001, were made, and their operation was tested under real operating conditions (

Figure 26).

Figure 27 shows a comparison of the operation of the two protection circuits with the CapXX HW209 supercapacitor. As a result of the continuous charging and discharging process of each supercapacitor, there is a variation in the voltages of its component cells (red line). The use of both an active balancer circuit and a protection circuit with two TS12001 integrated circuits maintains the voltage of both supercapacitor component cells at a certain level, with better properties in terms of levelling voltage levels being achieved when an active balancer is used.

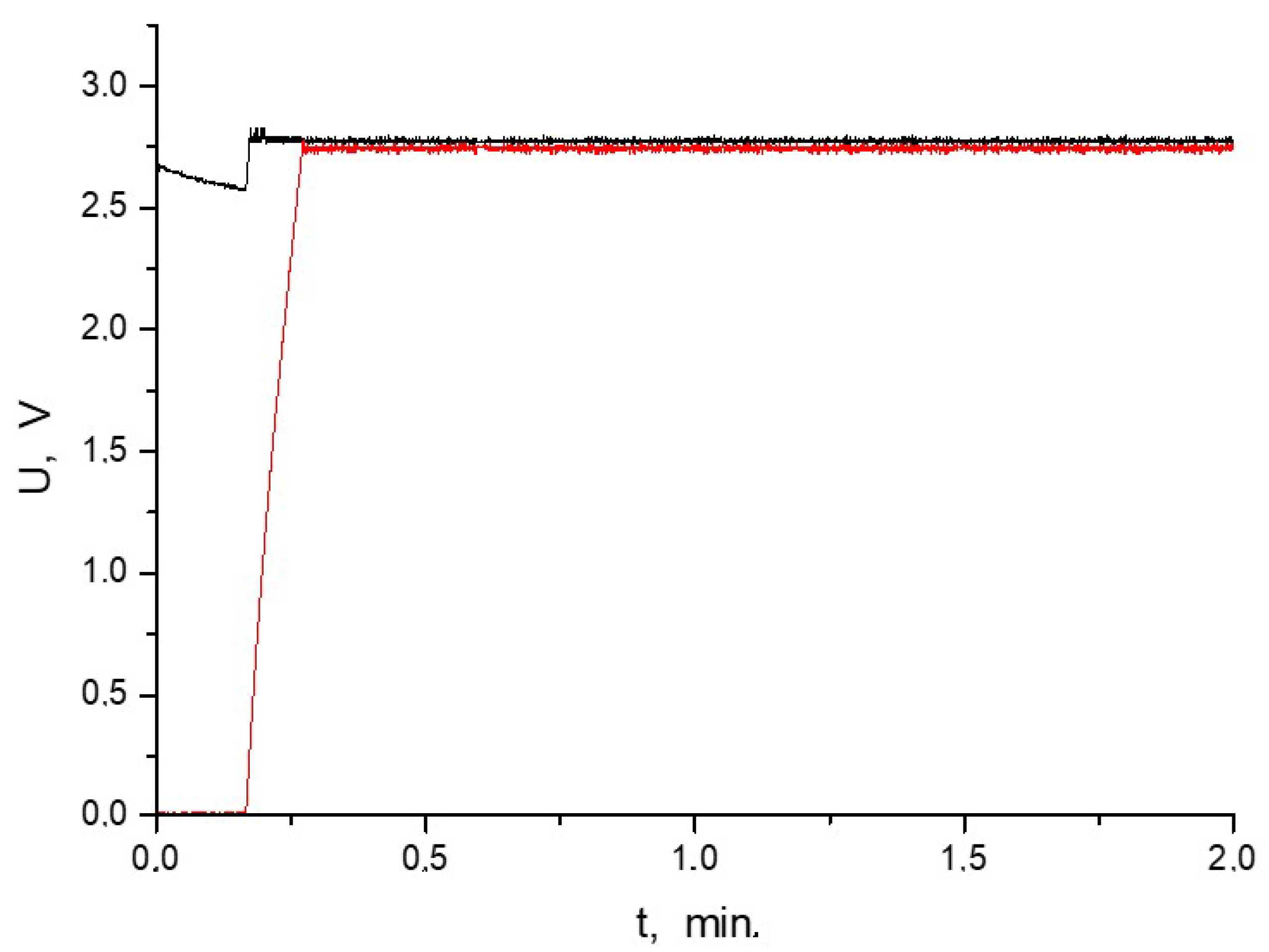

The operation of the TS12001 chip-based protection circuit was also tested in a different (non-direct) way (

Figure 28). Two supercapacitors were connected in series with each other. One of these supercapacitors was charged to a voltage of approximately 2.6 V. A charge of the entire connection to 6 V was started. Much earlier, the protection circuit of the supercapacitor, which was charged from a certain initial voltage, was tripped. The protection circuit did not allow this supercapacitor to be overcharged above the set point (approximately 2.7–2.8 V). After the cell was charged from 0 V, the voltages on both component supercapacitors were kept constant at around 2.7 V. The protection circuits did not allow these values to be exceeded, even though the charging circuits attempted to charge both supercapacitors connected in series to 6 V.

5. Conclusions

This paper presents the results of work aimed at investigating the performance of an energy recovery system (harvester) of electromagnetic fields generated by common-use telecommunications systems and RFID system devices with an energy conditioning and storage system under real-world conditions. The essence of this work was the possibility of realising the energy recovery process under specific environmental, system, and configuration conditions according to the developed concept of operation of a model semi-passive identifier. In the presented analysis, particular emphasis was placed on the realisation of the main energy storage using increasingly advanced supercapacitors, providing them with optimal operating conditions, protection against possible damage and—on the other hand—meeting the requirements of the target system for which the system was designed.

When using these elements in low-power systems, certain problems arise in relation to their internal structure and operating principle. A major drawback here is the relatively high values of leakage currents, especially in the initial stage (first seconds and minutes) of their charging. The leakage currents of supercapacitors are influenced by their level of charge or, in other words, by the correct formation of the charge layer. These phenomena are also strongly influenced by the way in which the supercapacitor is manufactured, the use of suitable materials for its construction. The only way out in all cases is to select the right supercapacitor for the application in question on the basis of research and analysis.

The leakage currents of various capacitors were measured and compared, and the influence of the supercapacitor voltage value on its leakage current level was determined. A study of the active balancer circuit, which is attached to two supercapacitors connected in series, was also carried out to prevent the supercapacitors from charging or discharging unevenly. The performance of the TS12001 circuit was also analysed when used to protect the supercapacitors from overcharging.

The selection of a supercapacitor for energy storage is multi-criteria, especially in the context of its use in micro-power systems such as RFID identifiers. Based on the research conducted, Cap-XX HA230 can be identified as a low leakage component for systems with relatively higher energy recovery from the environment, capable of ensuring a more stable long-term operation. However, in the case of RFID implementation, where energy recovery is low, the problems of increased leakage current in operating states with low and temporarily zero voltage on the capacitor should be taken into account, and components characterised by low leakage current (e.g., CLC03P012F12) should be selected in an area rarely documented by manufacturers. Note that in many cases, the selection of a supercapacitor based on capacity will be insufficient.

Energy density limitations are a major obstacle in certain applications where optimising energy storage capacity is essential. In this case, hybrid supercapacitors, which combine the advantages of classic capacitors with the capacity offered by supercapacitors, may be an alternative solution.