Optimal Grid-Forming Strategy for a Remote Hydrogen Production System Supplied by Wind and Solar Power Through MMC-HVDC Link

Abstract

1. Introduction

- A remote power supply system is designed for large-scale hydrogen production. A renewable power base consisting of wind power, solar power, and battery energy storage is connected to a remote hydrogen production load through a MMC-HVDC link. Compared with the traditional hydrogen production in an AC system and DC microgrid, the proposed schemes can achieve stable operation at a total scale of 400 MW through a 200 km DC transmission line. The topology is suitable for various industrial production scenarios in practice.

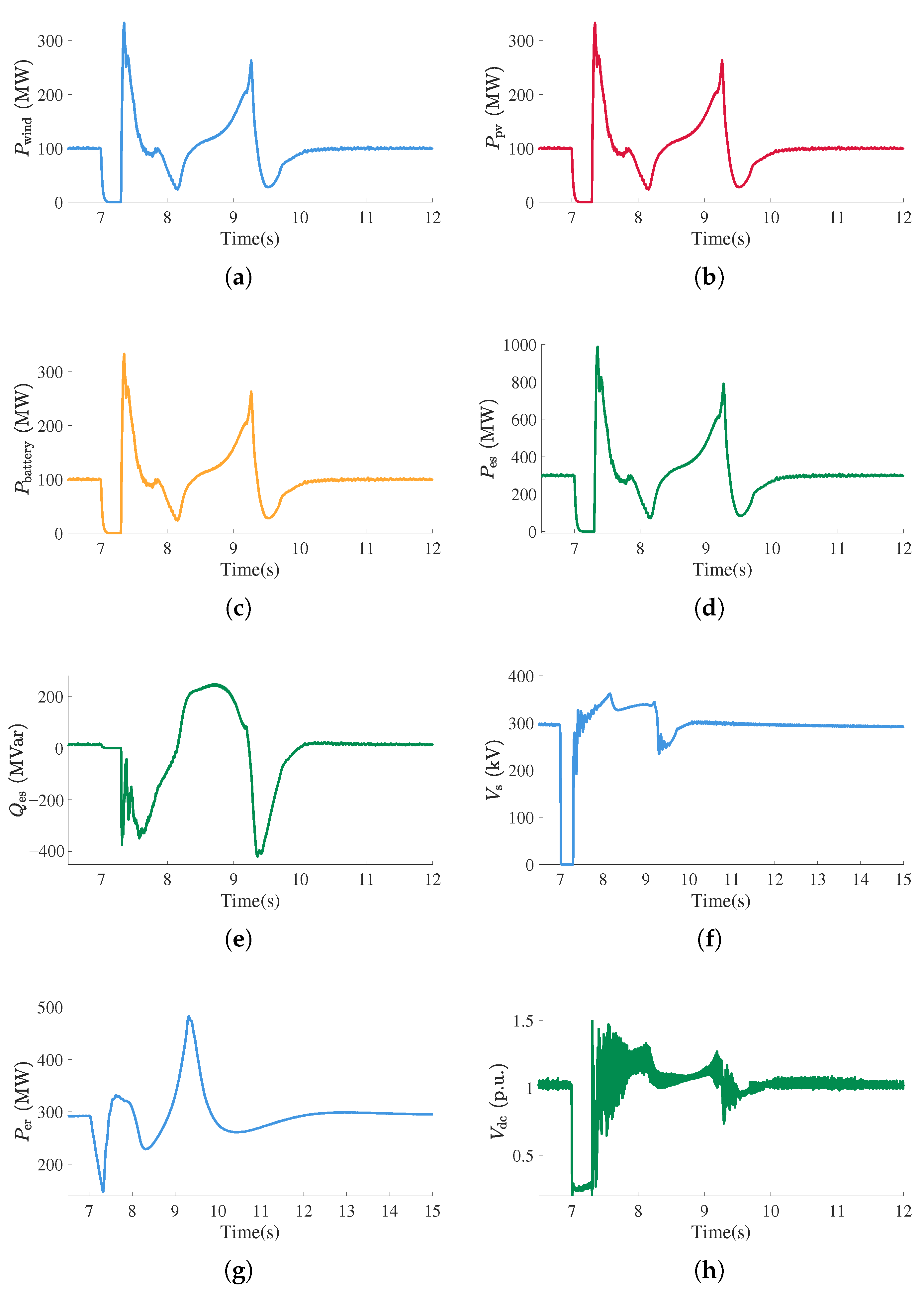

- Two grid-forming strategies are designed for the hydrogen production system. The first one is a battery energy storage-based grid-forming strategy, in which V/f control is employed for the battery energy storage station. The second one is a MMC-HVDC-based grid-forming strategy, in which the sending-end MMC station is control by VSG. Different from the conventional grid-following converter relying on the external power grid, the proposed two grid-forming schemes can achieve the support of voltage and frequency for the sending-end station. At the same time, the problem of frequency oscillation is overcome in long-distance transmission by equipping the system with MMC-HVDC.

- Impedance analysis is carried out for controller parameter optimization of renewable power sources and battery energy storage devices. Numerical simulations are undertaken to compare the performance of the two grid-forming strategies in the cases of both sending-end and receiving-end AC grid faults.

2. Design of System Structure and Grid-Forming Strategies

2.1. System Structure Design

2.2. Grid-Forming Strategies

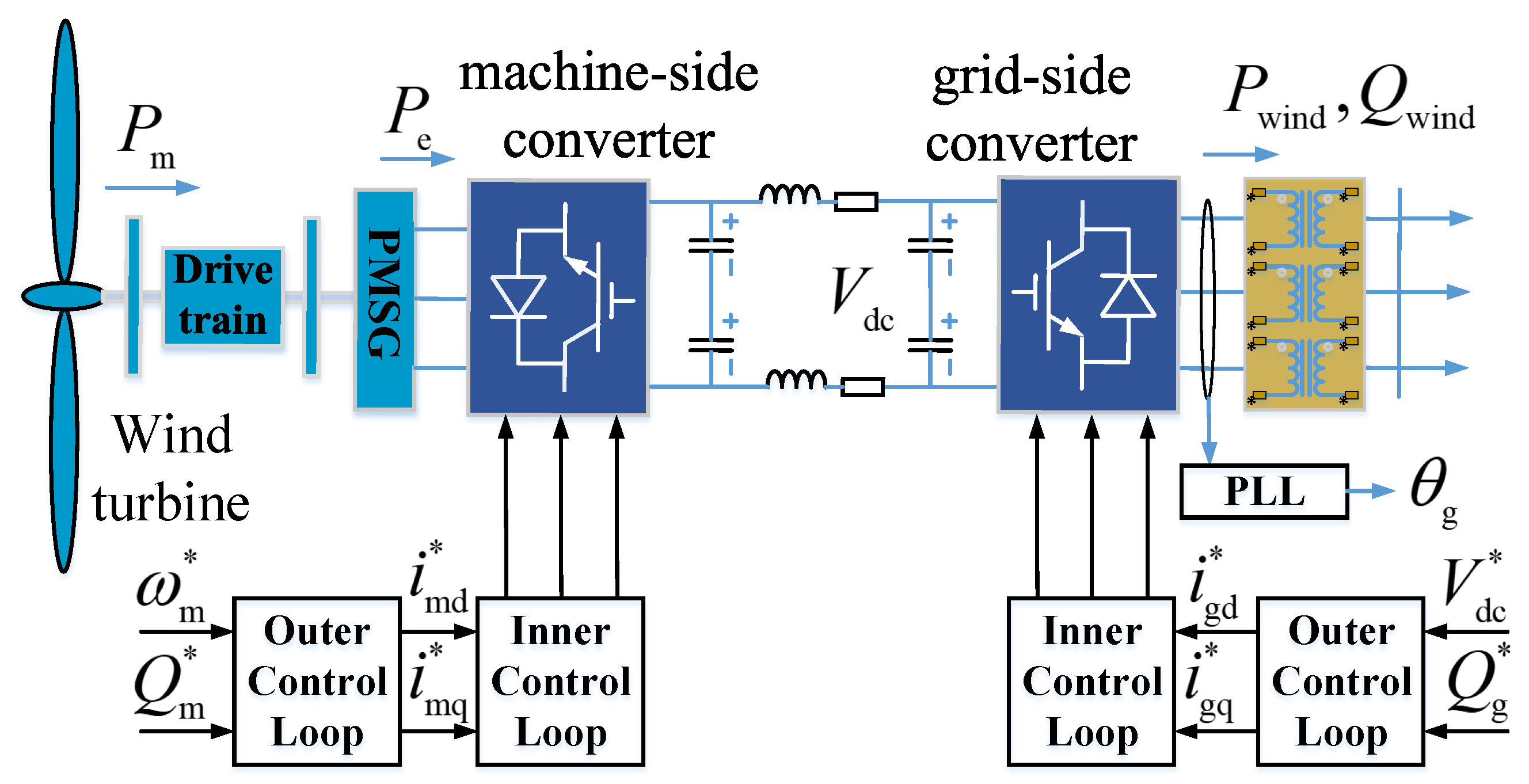

2.3. Control Scheme for Wind Power Plant

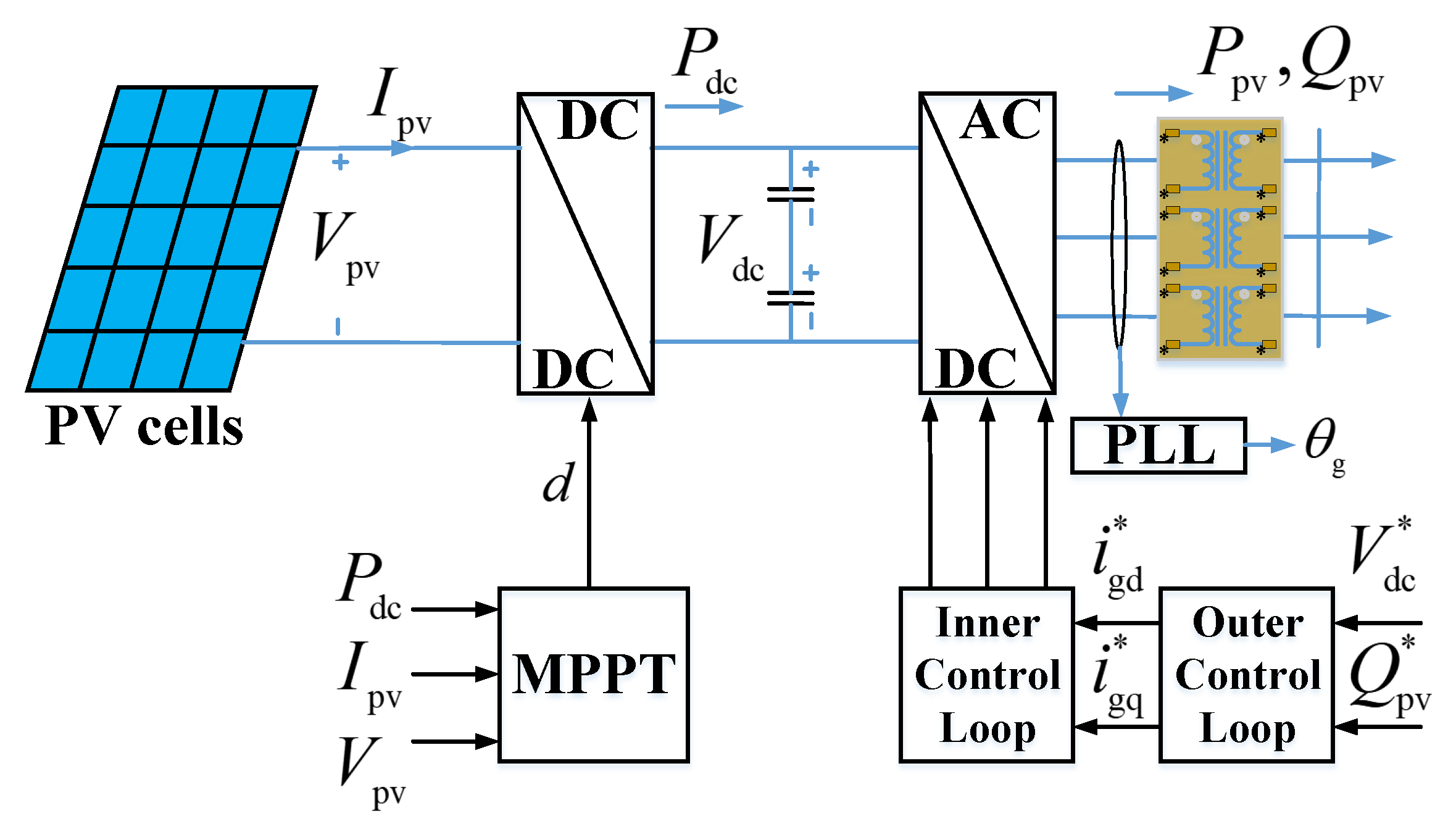

2.4. Control Scheme for PV Power Plant

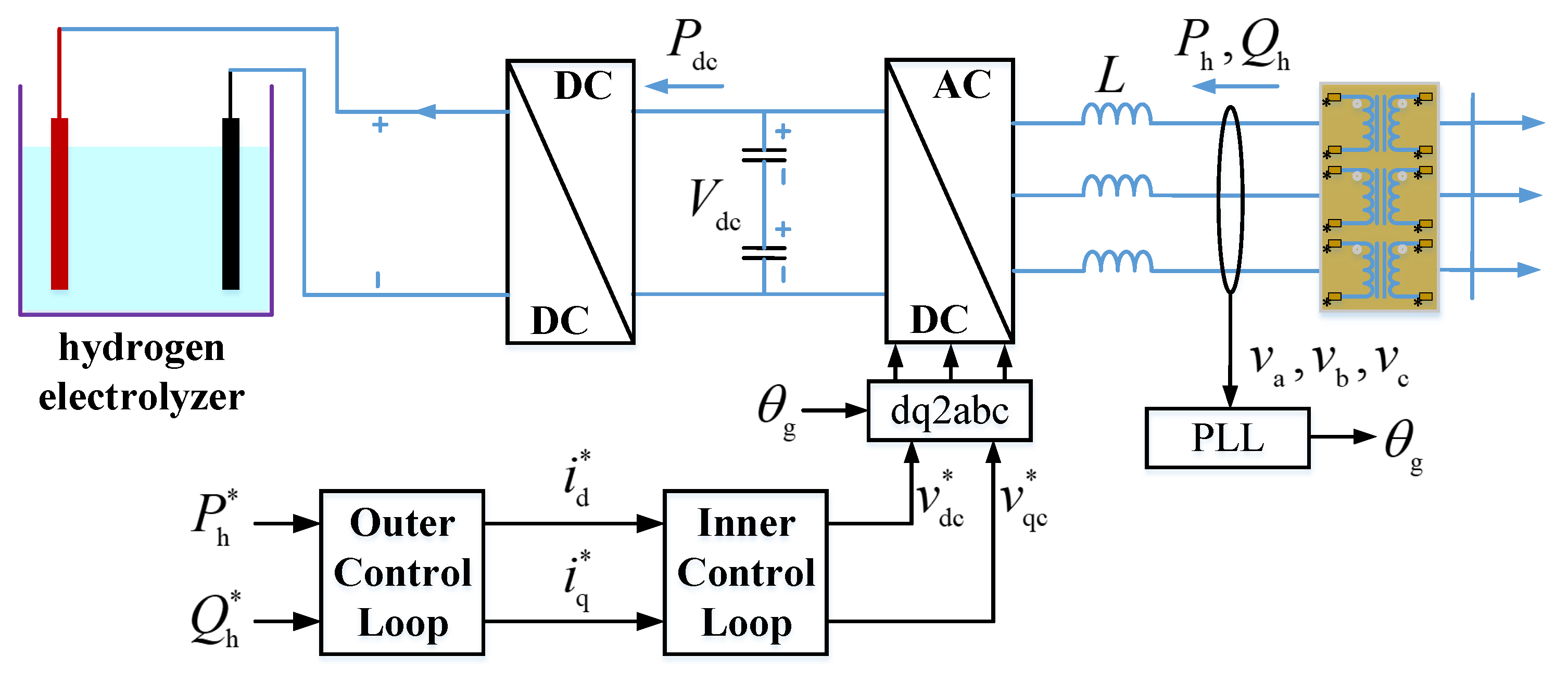

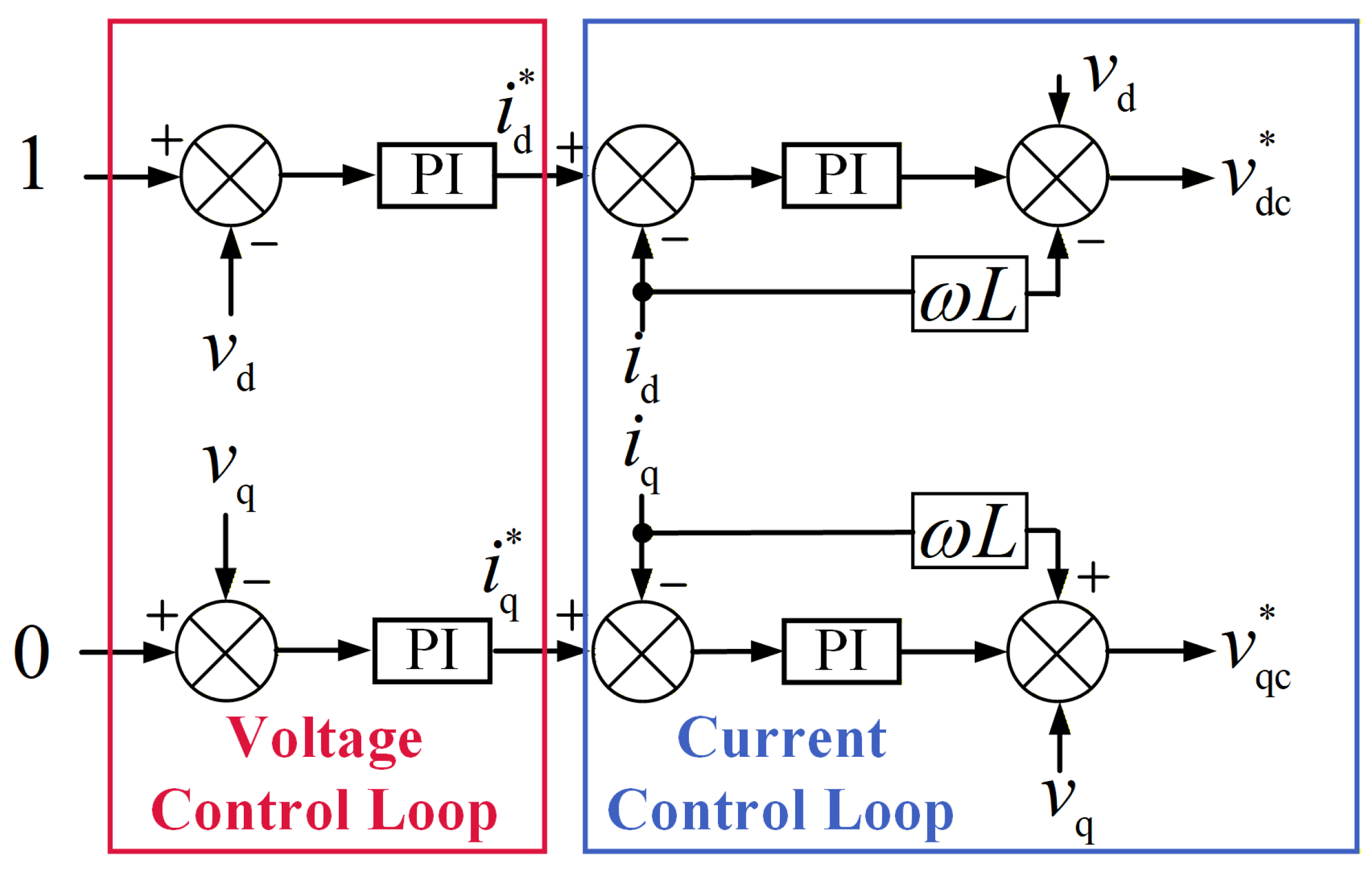

2.5. Hydrogen Production Load and Its Control System

2.6. Battery Energy Storage Station

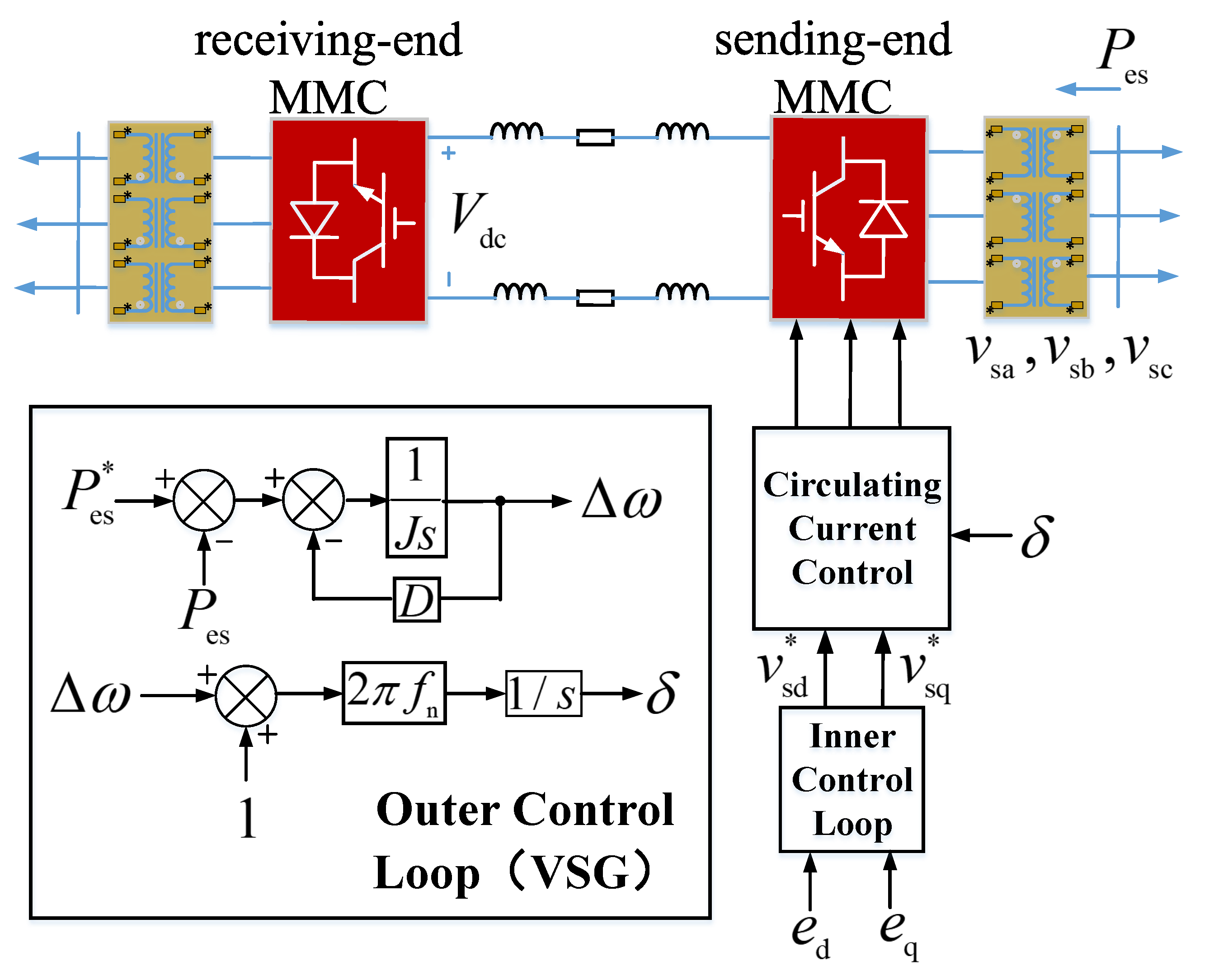

2.7. MMC-HVDC Link and Its Control System

3. Controller Parameter Optimization for Renewable Energy Base

3.1. Theory of Impedance Stability Analysis

3.2. Description of Impedance Measurement Method in PSCAD

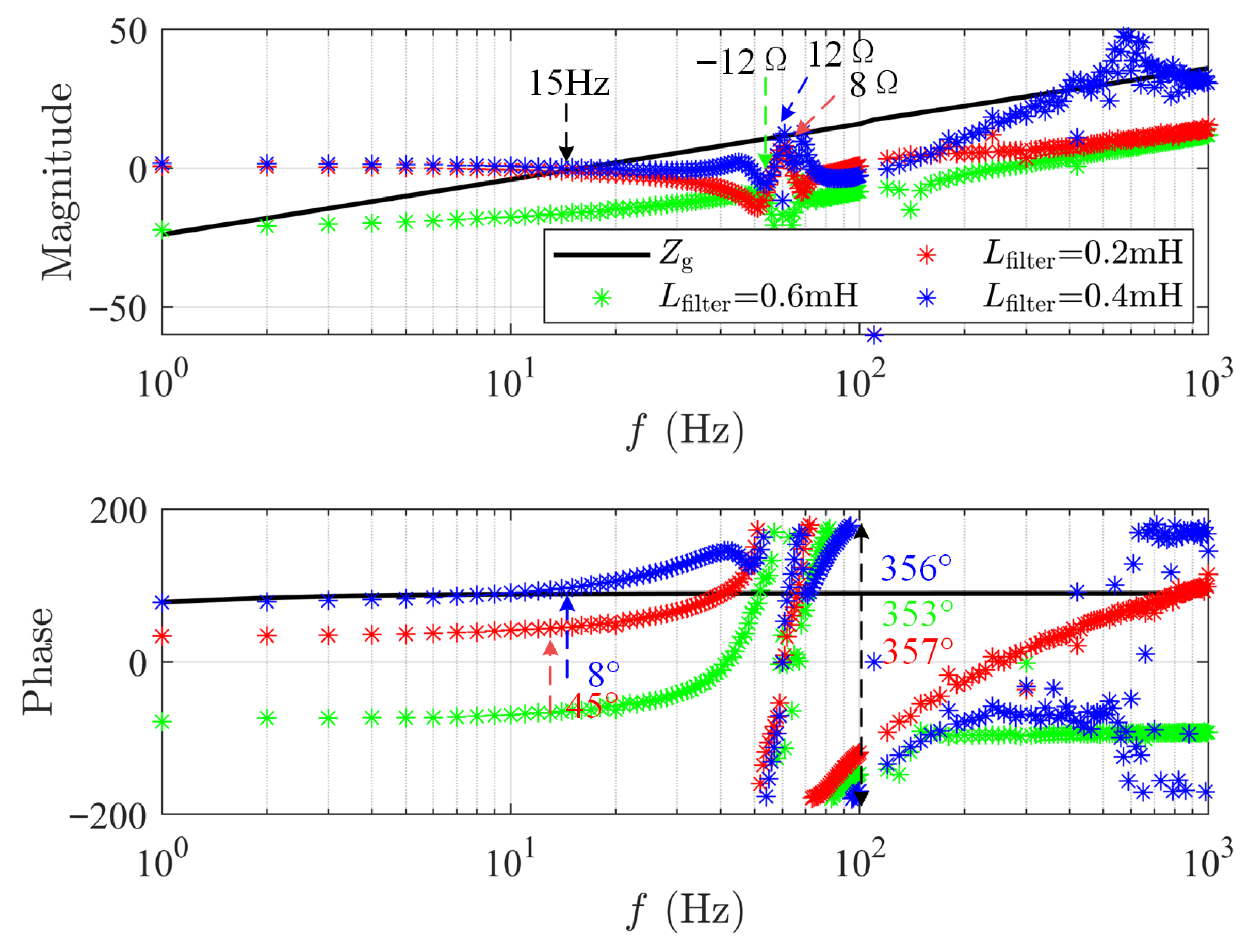

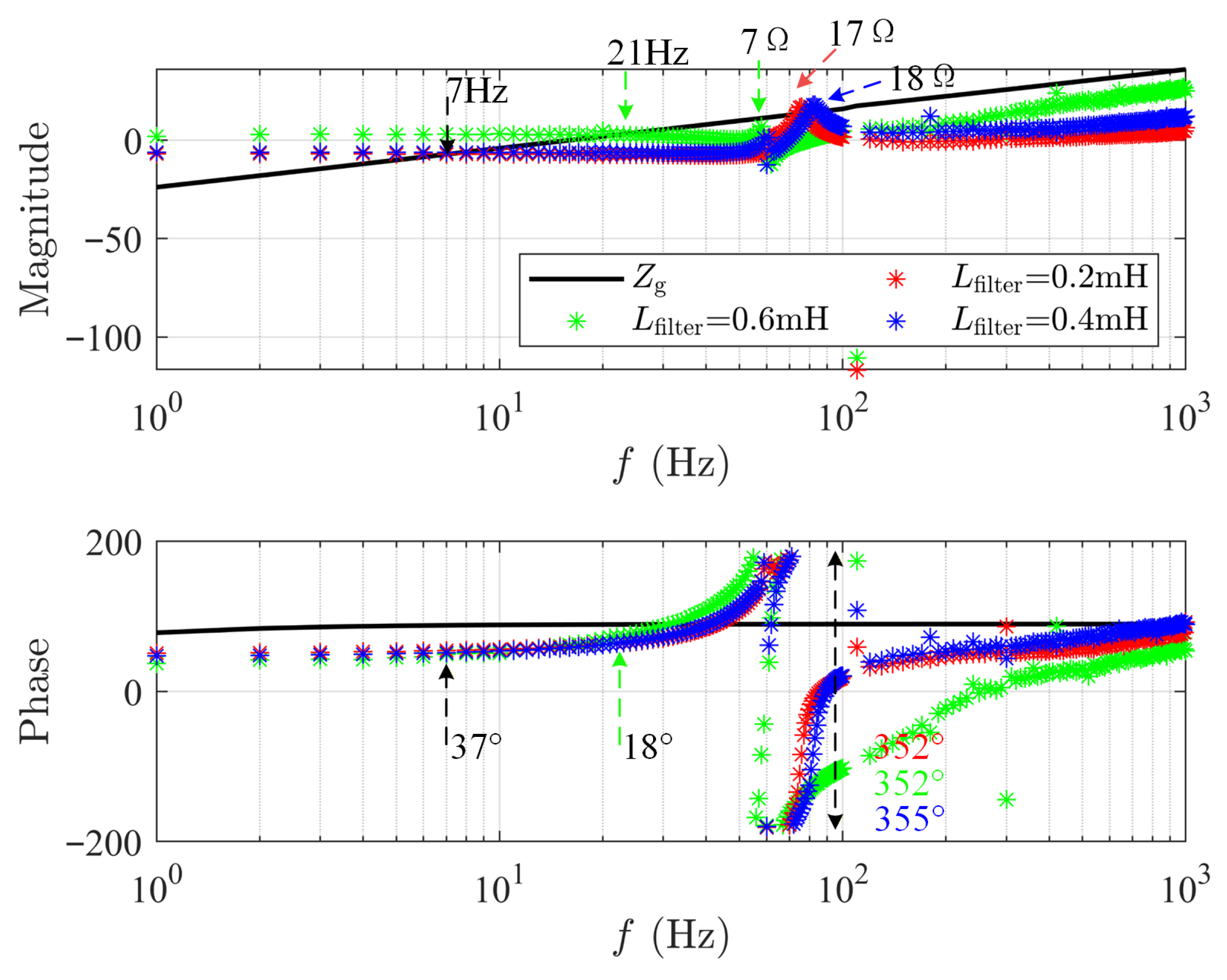

3.3. Parameter Optimization for Wind Power Generators

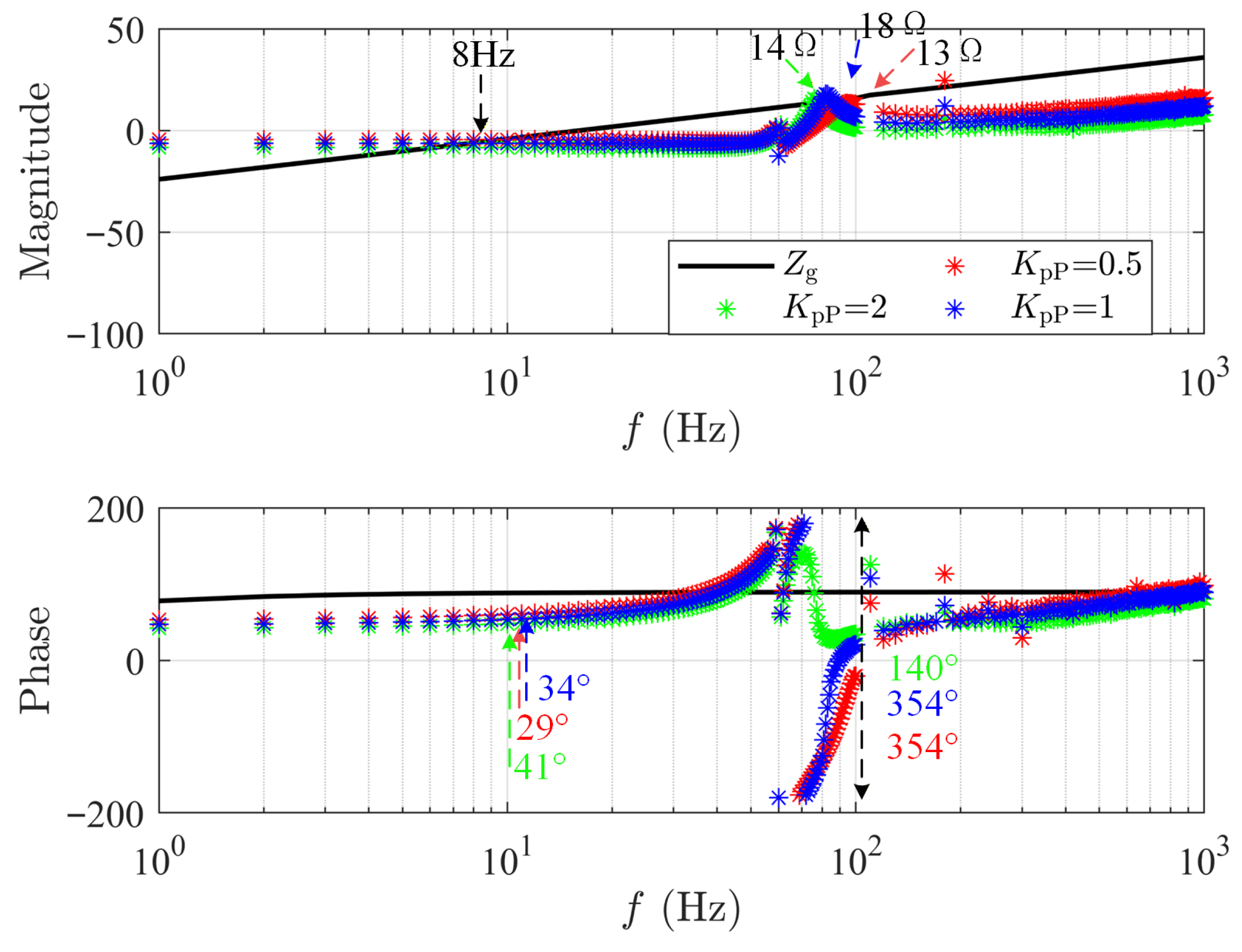

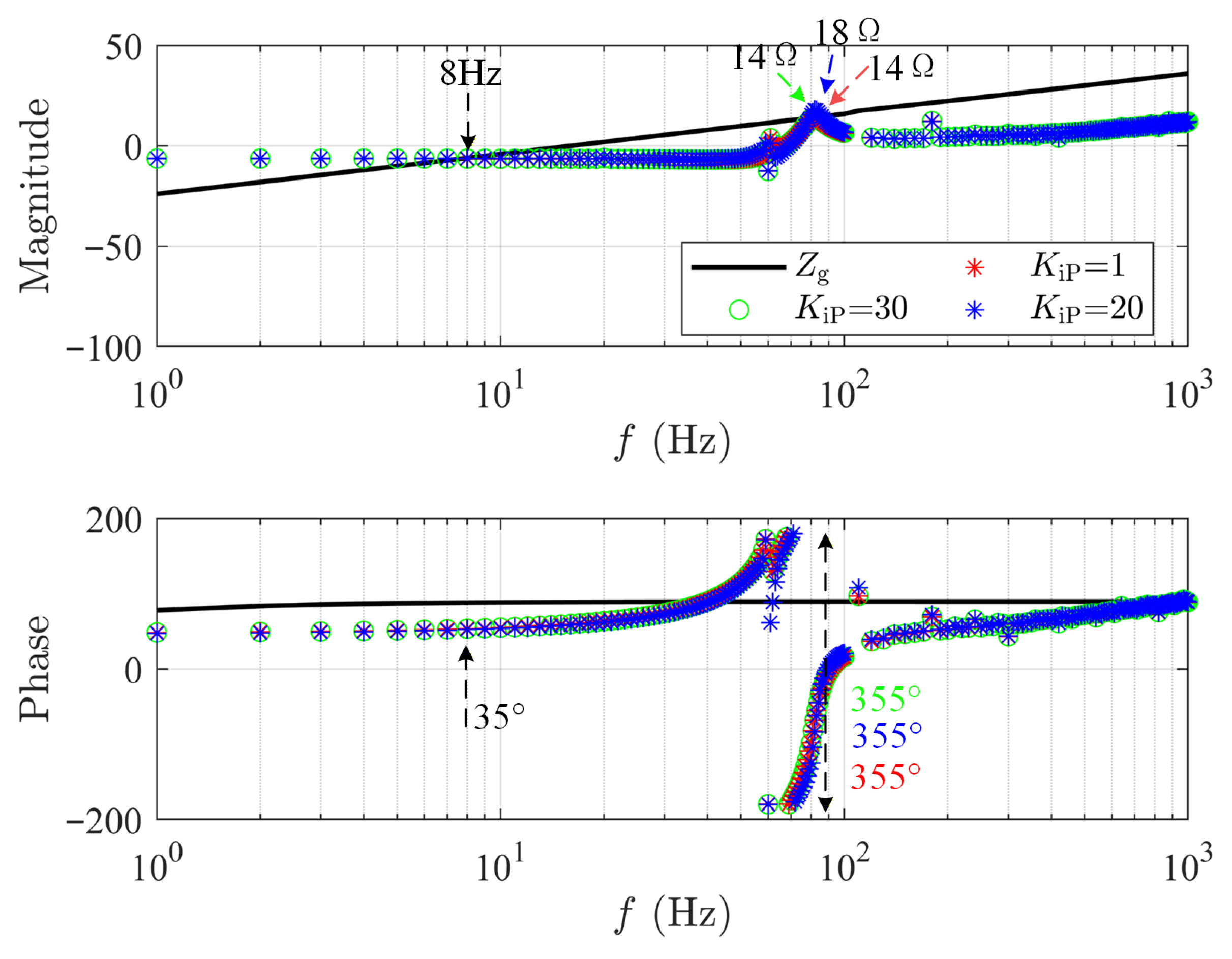

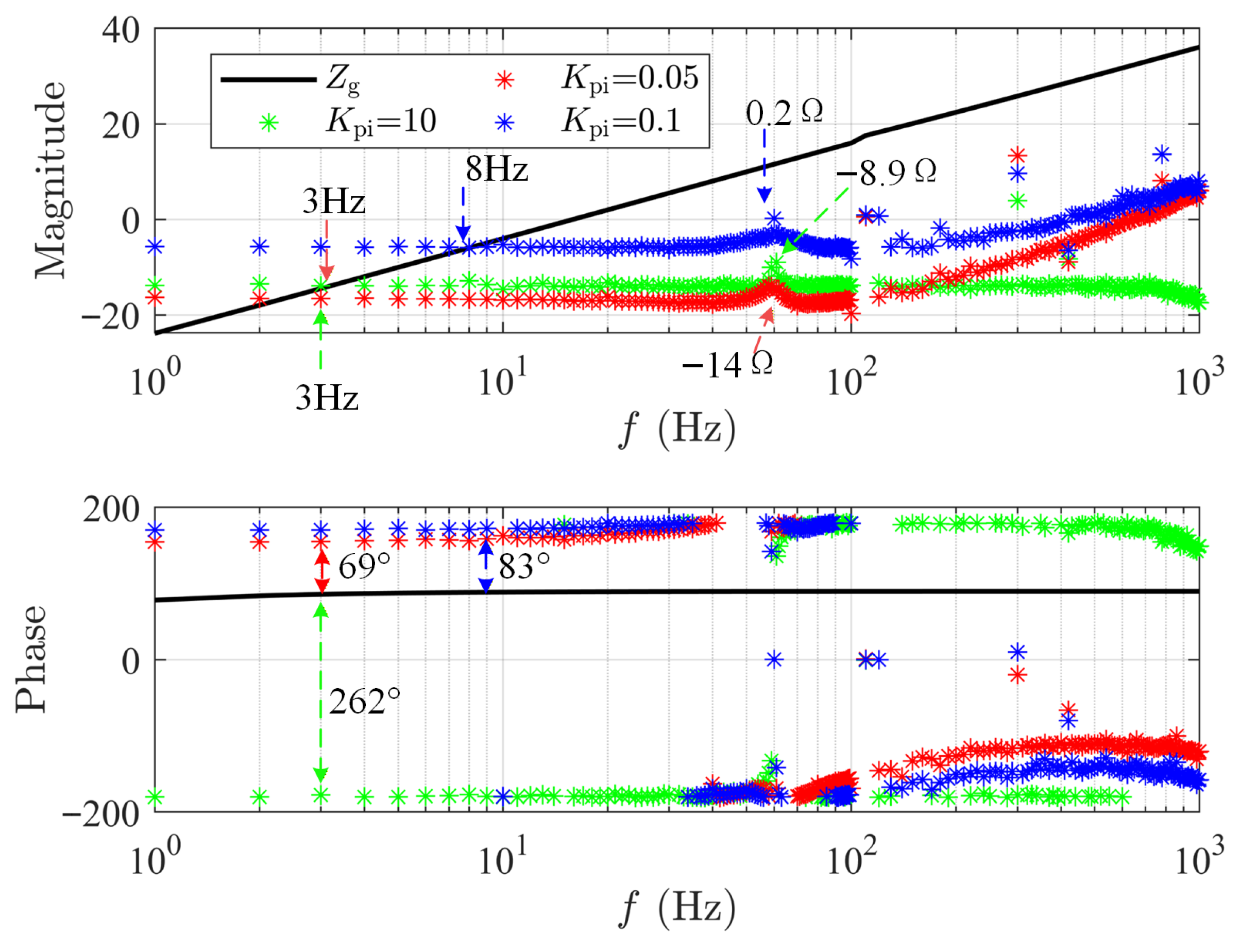

3.4. Parameter Optimization for Hydrogen Production Loads

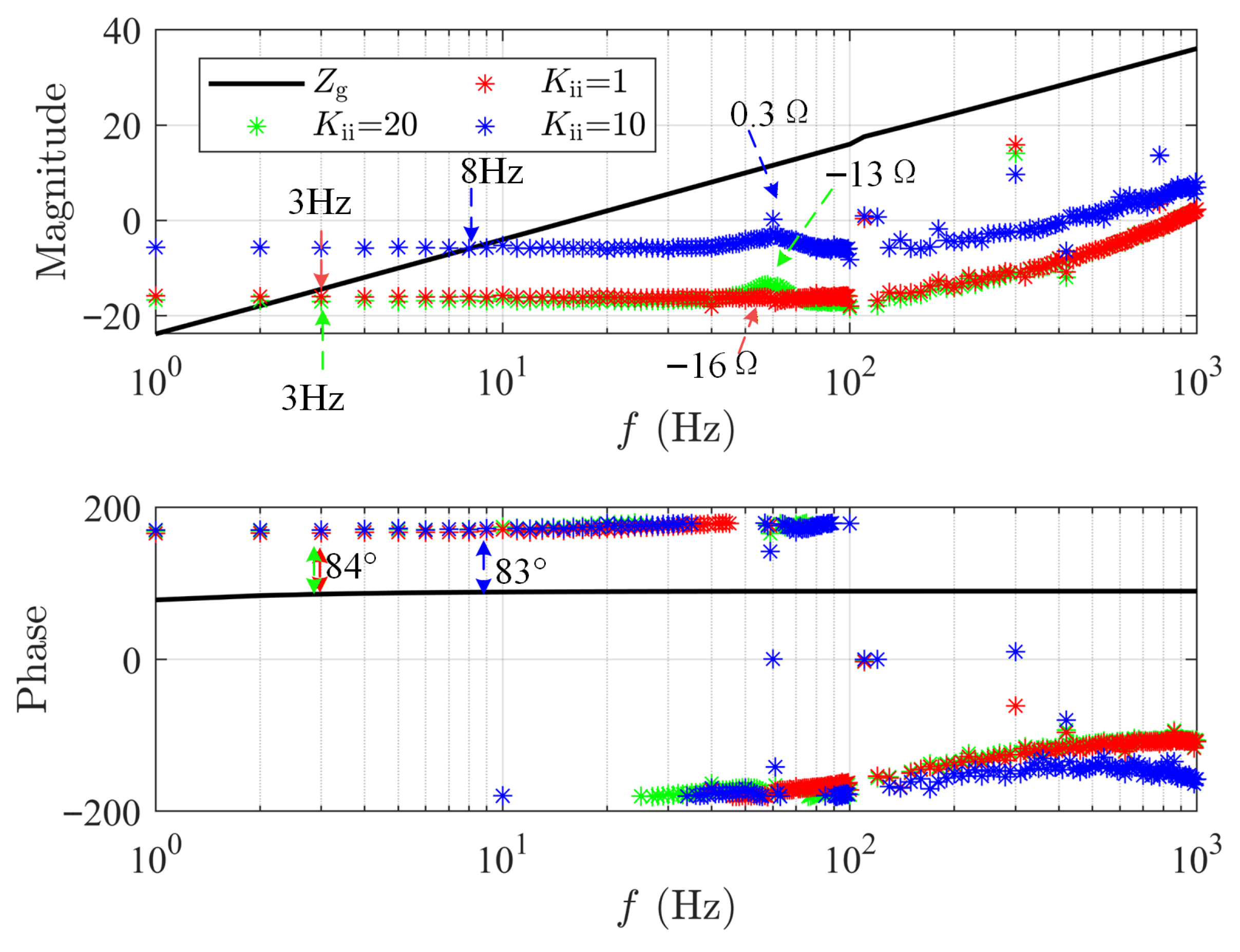

3.5. Parameter Optimization for Battery Energy Storage Stations

4. Results

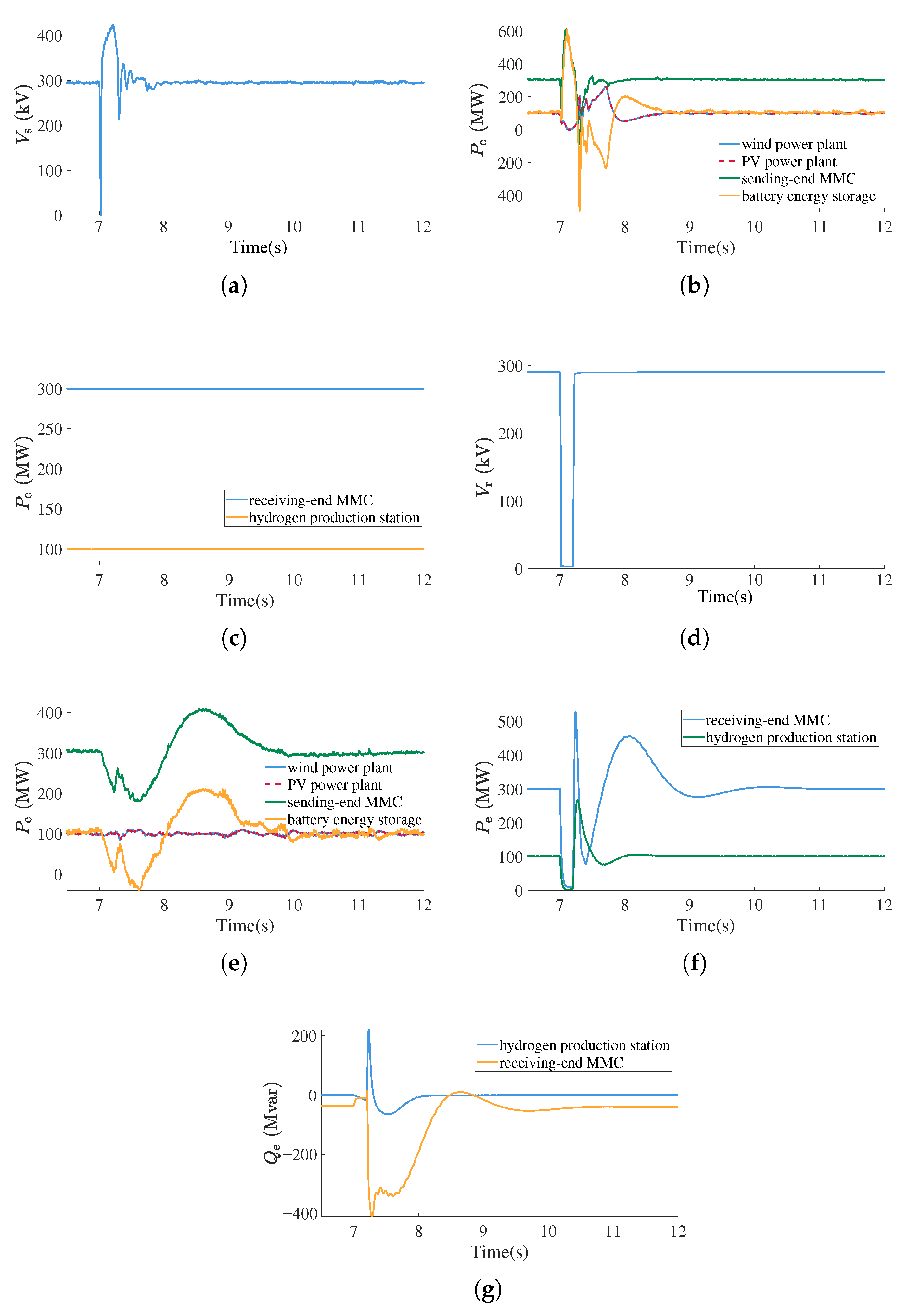

4.1. Transient Dynamics of Battery Energy Storage-Based Grid-Forming Strategy

4.2. Transient Dynamics of MMC-HVDC-Based Grid-Forming Strategy

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| WPG | Wind power generator |

| MMC | Modular multilevel converter |

| HVDC | High-voltage direct-current |

| PI | Proportional and integral |

| PLL | Phase locked loop |

| VSG | Virtual synchronous generator |

| RMS | Root mean square value |

| MMC-HVDC | MMC-based high-voltage direct-current transmission |

References

- Ramollo, K.V.; Ramohlola, K.E.; Maponya, T.C.; Hintsho-Mbita, N.C.; Modibane, K.D. Current developments on MIL-based metal-organic frameworks for photocatalytic hydrogen production. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2025, 180, 151728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Q.H.; Bose, A.; Singh, C.; Chow, J.H.; Mu, G.; Sun, Y.Z.; Liu, Z.X.; Li, Z.G.; Liu, Y. Control and Stability of Large-scale Power System with Highly Distributed Renewable Energy Generation: Viewpoints from Six Aspects. CSEE J. Power Energy Syst. 2023, 9, 8–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Liao, J.M.; Chen, Z.J.; Chen, Z.Y.; Yang, Y.X.; Xiahou, K.S.; Alkahtani, M. Evaluating transient stability of power systems by stability-preserving transfer of state vectors into domain of attraction of a state-reduction model. Int. J. Power Energy Syst. 2025, 171, 110930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Yao, H.J.; Di, P.Y.; Qin, Y.J.; Ma, Y.M.; Alkahtani, M.; Hu, Y.H. Region of Attraction Estimation for Power Systems with Multiple Integrated DFIG-Based Wind Turbines. IEEE Trans. Sustain. Energy 2025, 16, 3095–3109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.L.; Xiao, X.Z.; Li, Z.N.; Ouyang, L.Z. The perspective of offshore wind power: Based hydrogen production, hydrogen storage, and hydrogen transportation. Mater. Today 2025, 90, 800–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weng, X.; Jia, Z.; He, W.; Hu, Z.T.; Wang, K.S.; Hu, W.; Zhang, L.; Chu, W.F. Experimental and numerical study of a PV direct-coupled PEM electrolysis hydrogen production system. Renew. Energy 2026, 256, 124133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isaac, J.; Haidar, A.M.; Sabri, M.F.M.; Abdullah, M.O. Techno-economic analysis and dynamic operation of green hydrogen-integrated microgrid: An application study. Next Energy 2025, 9, 100418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiahou, K.S.; Zou, K.H.; Wang, Y.; Lin, Z.J.; Liu, Y.; Liu, Z.X.; Wu, Q.W. Distributed Observer-Based Resilient Control of Cyber-Physical DC Microgrids Against Communication-Link and Local Attacks. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 2025, 16, 5459–5471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.Y.; Huang, J.J.; Xu, Z.B.; Zhang, C.L.; Guan, X.H. Real-World Scale Deployment of Hydrogen-Integrated Microgrid: Design and Control. IEEE Trans. Sustain. Energy 2024, 15, 2380–2392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.Q.; Li, Q.; Zhao, S.D.; Chen, W.R.; Liu, H. A Hierarchical Self-Regulation Control for Economic Operation of AC/DC Hybrid Microgrid With Hydrogen Energy Storage System. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 89330–89341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Y.; Ling, X. Forecasting green hydrogen production in China: Hybrid deep learning assessment of economic, environmental, and renewable energy integration. Renew. Energy 2026, 256, 124414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kountouris, I.; Forcellati, M.; Pantelidis, I.; Keles, D. Renewable hydrogen and ammonia production: Location-specific considerations and competitive market dynamics in Europe. Appl. Energy 2025, 397, 126168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.Y.; Zhu, H.Y.; Luo, X.Y.; Chang, S.P.; Guan, X.P. A novel optimal dispatch strategy for hybrid energy ship power system based on the improved NSGA-II algorithm. Electr. Power Syst. Res. 2024, 232, 110385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Li, H.H.; Yang, Y.X.; Chen, Y.S.; Xiahou, K.S.; Wu, Q.H. Controlling inverters as flux linkage sources: Unifying operating mechanisms of power electronics inverters and AC machineries. CSEE J. Power Energy Syst. 2025, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.; Zhou, X.Y.; Ouyang, S. Capacitor Voltage Synchronizing Control-Based VSG Scheme for Inertial and Primary Frequency Responses of Type-4 WTGs. IET Gener. Transm. Distrib. 2018, 12, 3416–3469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, F.J.; Sawant, N.Y.; Pandey, A.A.; Thali, P.S.; Patange, Y.P.; Jadhav, S. Recent Advancements in Hydrogen: Overview of Hydrogen Production and Storage Technologies. In Proceedings of the 2025 7th International Conference on Inventive Material Science and Applications (ICIMA), Namakkal, India, 28–30 May 2025; Volume 2025, pp. 1035–1042. [Google Scholar]

- Debe, M.K.; Hendricks, S.M.; Vernstrom, G.D.; Meyers, M.; Brostrom, M.; Stephens, M.; Chan, Q.; Willey, J.; Hamden, M.; Mittelsteadt, C.K.; et al. Initial performance and durability of ultra-low loaded NSTF electrodes for PEM electrolyzers. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2012, 159, 165–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abomazid, A.M.; El-Taweel, N.A.; Farag, H.E.Z. Novel Analytical Approach for Parameters Identification of PEM Electrolyzer. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inform. 2022, 18, 5870–5881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiahou, K.S.; Du, W.; Xu, X.Y.; Lin, Z.J.; Liu, Y.; Liu, Z.X. Resilience Assessment for Hybrid AC/DC Cyber-Physical Power Systems Under Cascading Failures. IEEE Trans. Reliab. 2025, 74, 3442–3453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Symbol | Description |

|---|---|

| the open-circuit voltage of the hydrogen electrolyzer | |

| the temperature of the electrolyzer | |

| R | air constant |

| the water activity between the anode and the electrolyte | |

| the standard electromotive force | |

| the independent energy change constant in chemical reaction | |

| F | Faraday constant |

| the exchange coefficient of the electrolytic membrane | |

| the active power of | |

| the active power of | |

| i | the current density |

| the exchange current density | |

| the equivalent resistance of the electrolytic membrane | |

| output voltage of the hydrogen electrolyzer | |

| the reversible voltage of electrolyzer | |

| the current supplied to the electrolyzer | |

| the temperature of the electrolyzer | |

| equivalent resistance | |

| equivalent resistance | |

| over-voltage coefficient of the electrolyzer | |

| over-voltage coefficient of the electrolyzer | |

| over-voltage coefficient of the electrolyzer | |

| over-voltage coefficient of the electrolyzer | |

| A | the area of the electrode of the electrolyzer |

| the empirical temperature coefficient of the reversible voltage | |

| the reversible voltage under normal operation conditions | |

| the current efficiency of the electrolyzer |

| Parameter | Value | Parameter | Value | Parameter | Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (V) | 1.23 | A (m2) | 0.1 | (V/K) | 1.93 × |

| ( · m2) | 8.232 | ( · m2) | −4.51 × | (V) | 0.185 |

| (m2/A) | 2.54 × | (m2 · K2/A) | −0.158 | (m2· K2/A) | 1.212 × |

| 1 | 2.54 × | 0.96 |

| Parameter | Value | Parameter | Value | Parameter | Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| resistance/km | 0.18 | inductance/km | 8 H | capacitance/km | 10 F |

| 400 MVA | 400 MVA | 400 MVA |

| Parameter | Value | Parameter | Value | Parameter | Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| base MVA | 1000 MVA | arm resistance | 0.3 | arm inductance | 0.24 H |

| filter resistance | 0.46 | filter inductance | 0.064 H | submodule number | 264 |

| rated frequency | 60 Hz | rated AC voltage | 290 kV | rated DC voltage | 500 kV |

| PI outer loop | 2, 1 | PI inner loop | 0.9, 0.05 |

| Parameter | Value | Parameter | Value | Parameter | Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| base MVA | 1000 MVA | arm resistance | 0.3 | arm inductance | 0.24 H |

| filter resistance | 0.46 | filter inductance | 0.064 H | submodule number | 264 |

| rated frequency | 60 Hz | rated AC voltage | 290 kV | rated DC voltage | 500 kV |

| PI outer loop | 2, 1 | PI inner loop | 0.9, 0.05 | D | 0.5 |

| virtual inertia | 2 s | −0.3 p.u. |

| Dynamic Response | Battery Energy Storage-Based Grid-Forming Strategy | MMC-HVDC-Based Grid-Forming Strategy |

|---|---|---|

| Critical clearing time in sending-end station | 0.02 s | 0.3 s |

| Damping and inertia support | no | yes |

| Recovery time from fault and fault duration | 0.02 s/2 s | 0.3 s/4.7 s |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chao, W.; Huang, J.; Zhang, Z.; Tian, C.; Dai, L.; Wang, J.; Lin, X. Optimal Grid-Forming Strategy for a Remote Hydrogen Production System Supplied by Wind and Solar Power Through MMC-HVDC Link. Electronics 2025, 14, 4824. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics14244824

Chao W, Huang J, Zhang Z, Tian C, Dai L, Wang J, Lin X. Optimal Grid-Forming Strategy for a Remote Hydrogen Production System Supplied by Wind and Solar Power Through MMC-HVDC Link. Electronics. 2025; 14(24):4824. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics14244824

Chicago/Turabian StyleChao, Wujie, Junwei Huang, Zhibo Zhang, Changgeng Tian, Liyu Dai, Jinke Wang, and Xinyi Lin. 2025. "Optimal Grid-Forming Strategy for a Remote Hydrogen Production System Supplied by Wind and Solar Power Through MMC-HVDC Link" Electronics 14, no. 24: 4824. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics14244824

APA StyleChao, W., Huang, J., Zhang, Z., Tian, C., Dai, L., Wang, J., & Lin, X. (2025). Optimal Grid-Forming Strategy for a Remote Hydrogen Production System Supplied by Wind and Solar Power Through MMC-HVDC Link. Electronics, 14(24), 4824. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics14244824