An Ensemble Imbalanced Classification Framework via Dual-Perspective Overlapping Analysis with Multi-Resolution Metrics

Abstract

1. Introduction

- •

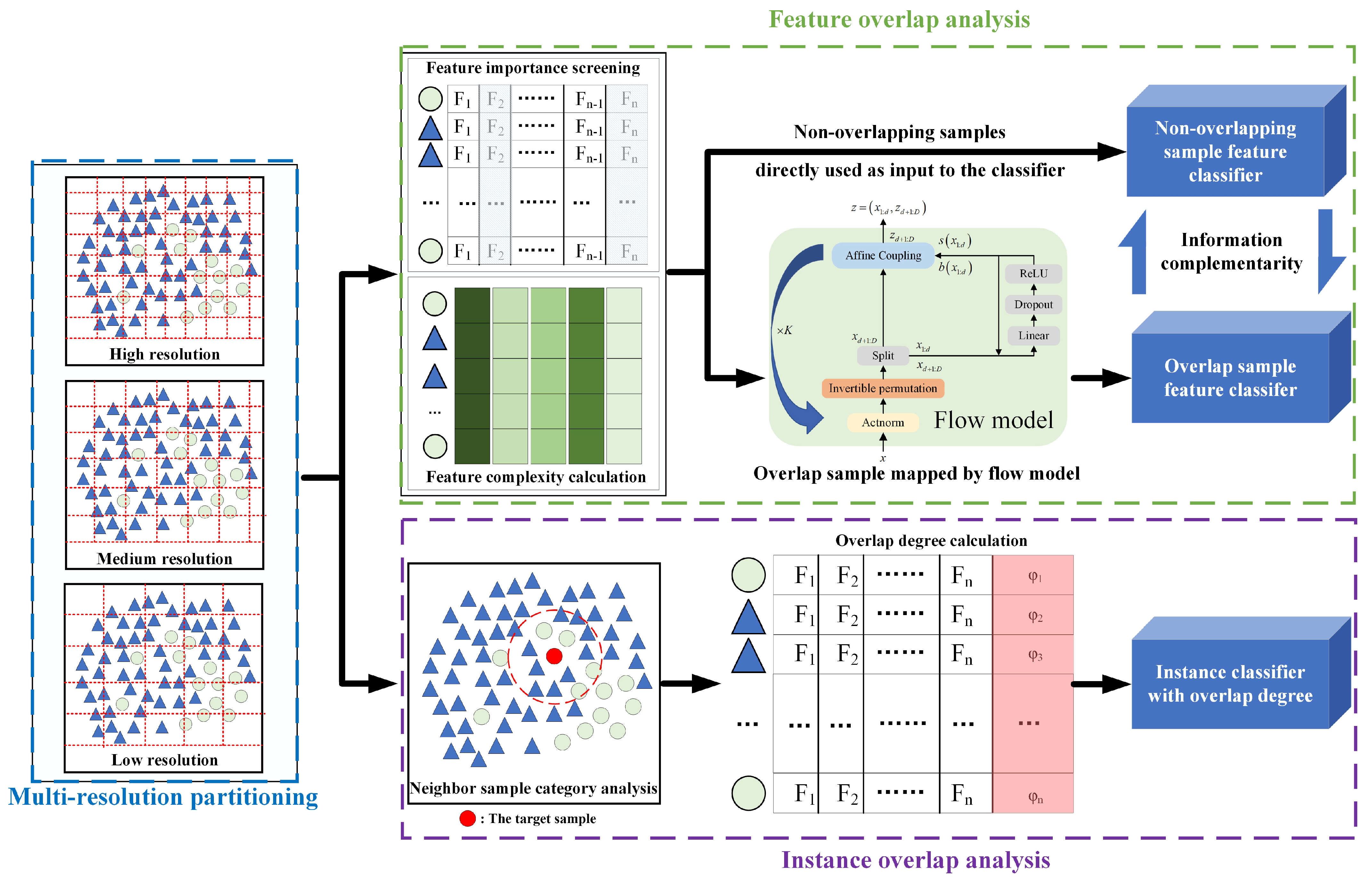

- A dual-perspective multi-resolution overlap measurement framework is proposed. We propose a unified framework that analyzes overlap from both “feature” and “instance” perspectives across multiple resolutions. This approach captures distributional information from local to global levels, overcoming the limitations of single-metric methods in identifying complex overlap patterns.

- •

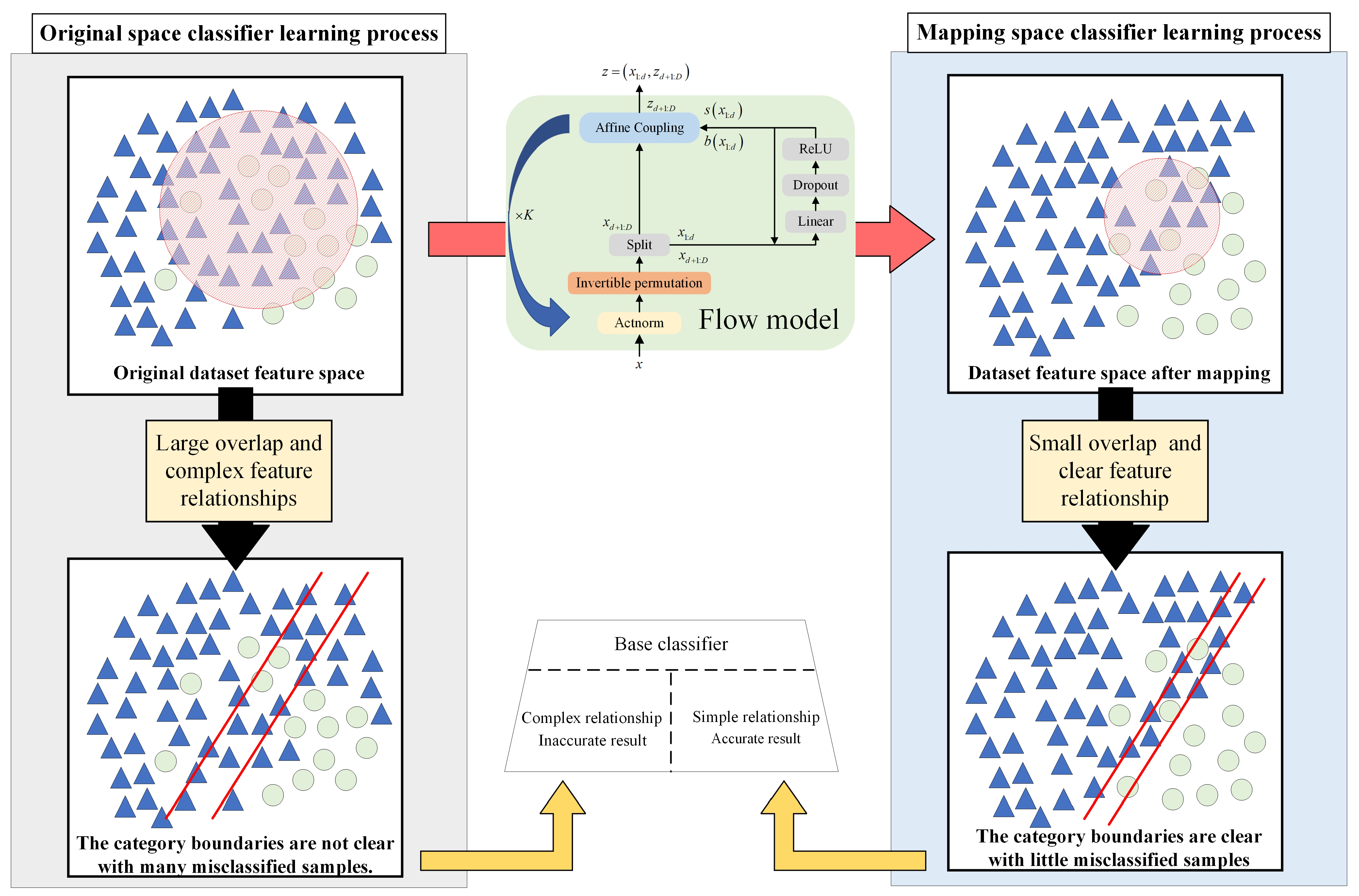

- A method for overlapping feature separation based on flow model mapping is proposed. To address the “feature overlap” challenge, we design a flow model-based mapping strategy. This mechanism projects highly entangled samples into a lower-dimensional, separable latent space, significantly reducing the difficulty of learning discriminative features in boundary regions.

- •

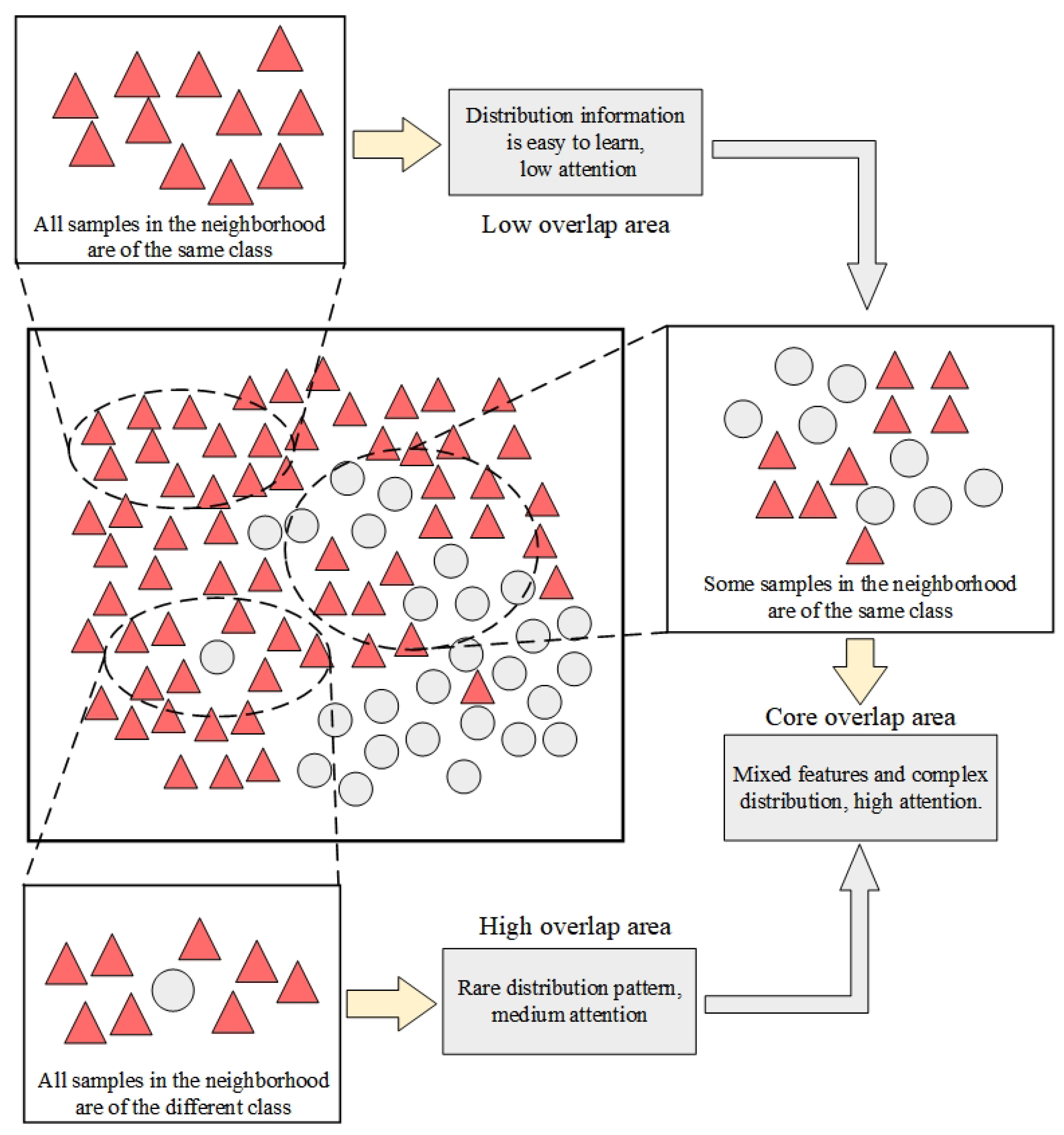

- A method for calculating attention weights based on multi-nearest-neighbor distribution discrimination in the data neighborhood is proposed. Focusing on “instance overlap,” we develop an adaptive weighting scheme that categorizes samples based on their neighborhood heterogeneity. This enables the model to selectively prioritize hard-to-classify boundary samples while suppressing noise and redundant information from the majority class.

2. Related Work

2.1. Data-Level Imbalanced Classification Methods

2.2. Algorithm-Level Imbalanced Classification Methods

2.3. Relevant Work on Overlap Region Division

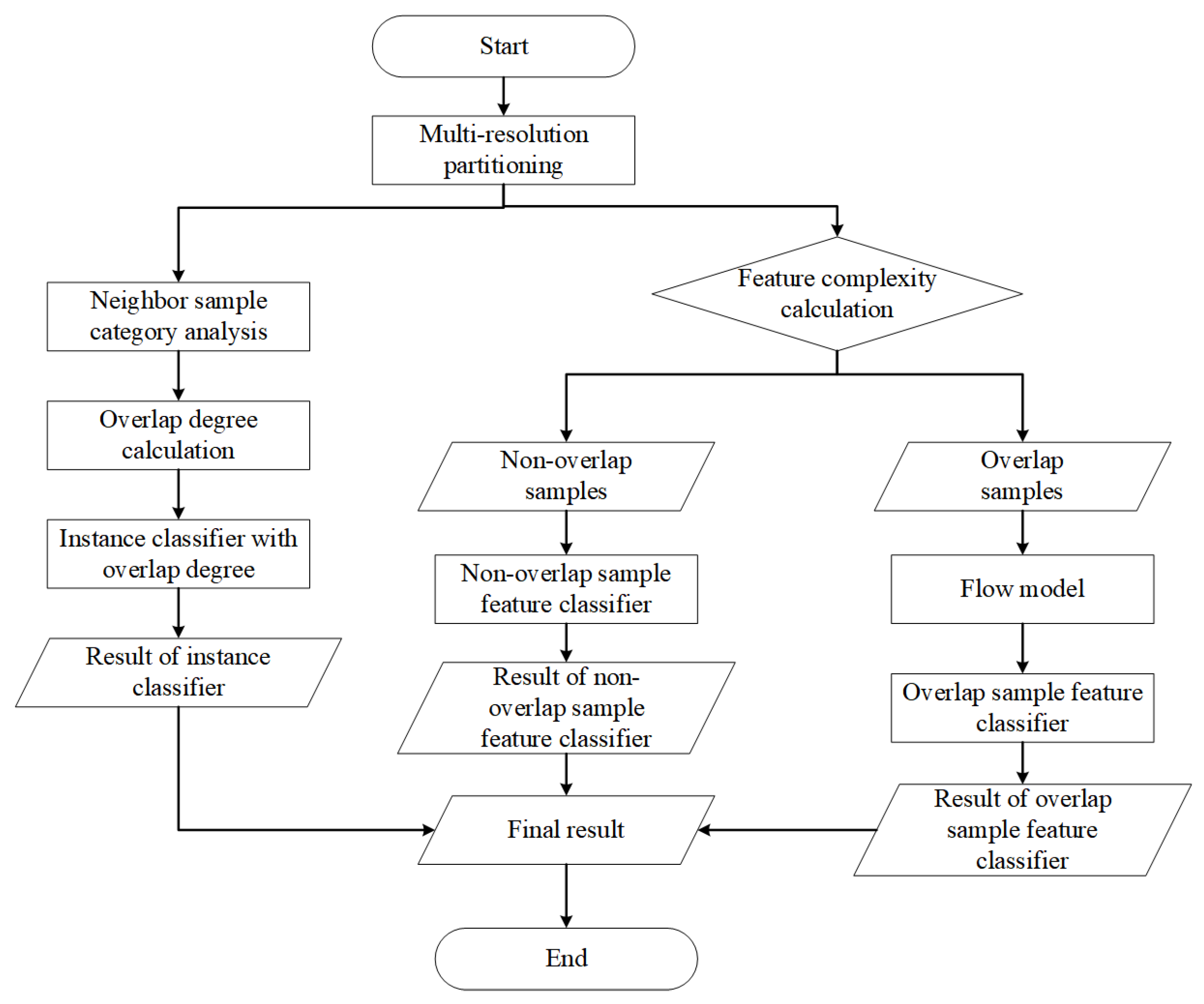

3. The Proposed Method: DPOA-MRM

3.1. The Framework for Overlap Degree Analysis Based on Dual-Perspective and Multi-Resolution Measurements

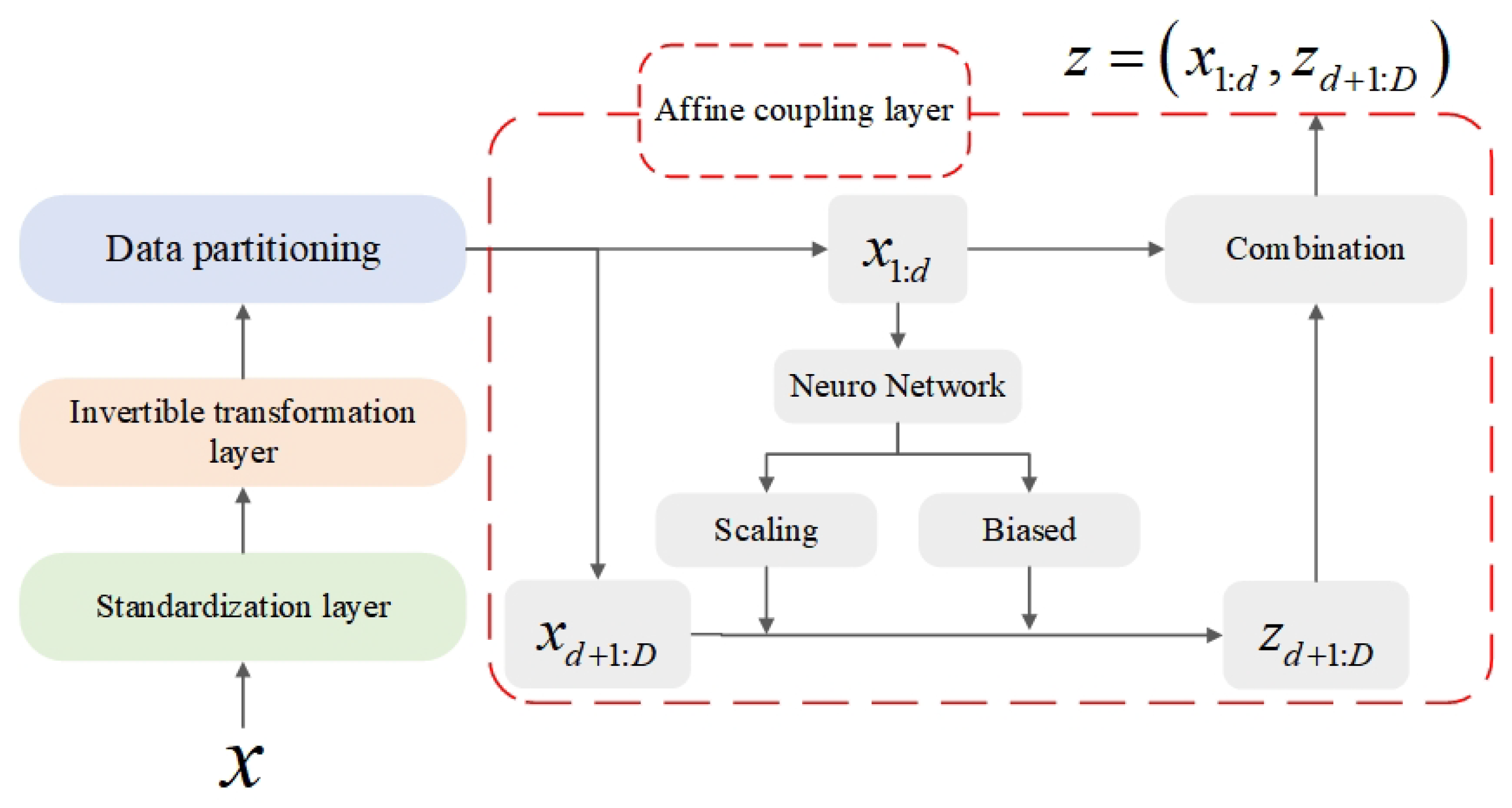

3.2. Hybrid Feature Separation Method Based on Flow Model Mapping

| Algorithm 1 The calculation process of feature overlap. |

| Require: Training dataset , the training epochs of flow model , The number of samples sampled during each training of the flow model . |

| Ensure: Feature overlapping sample set ; Non overlapping feature sample set ; Trained Flow Model ; Trained feature overlapping sample classifier ; Trained feature non overlapping sample classifier ; |

|

3.3. Attention Weight Calculation Method Based on Multi-Neighbor Distribution Discrimination

| Algorithm 2 The overlap weights calculation process. |

| Require: Original dataset X, the size of the nearest neighbor pool S, The overall expansion factor of the dataset . |

| Ensure: Target-neighbor sample combination dataset A; |

| for each x in X do |

|

3.4. Algorithm Complexity Analysis

3.4.1. Time Complexity

3.4.2. Space Complexity

3.4.3. Comparison of Complexity with Existing Ensemble Methods

4. Experiments

4.1. Datasets and Evaluation Metrics

4.2. Parameter Settings

4.3. Comparison with Imbalanced Classification Methods

4.4. Comparison of Experimental Results When the Datasets Overlap Seriously

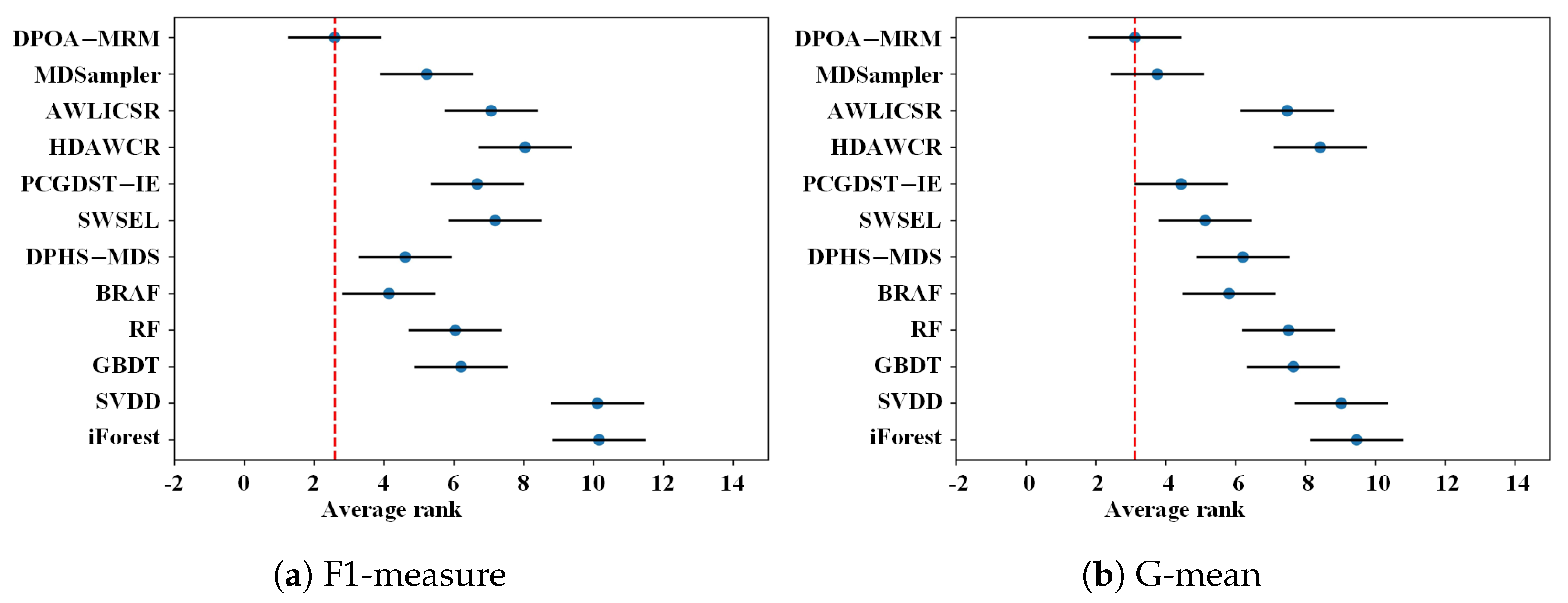

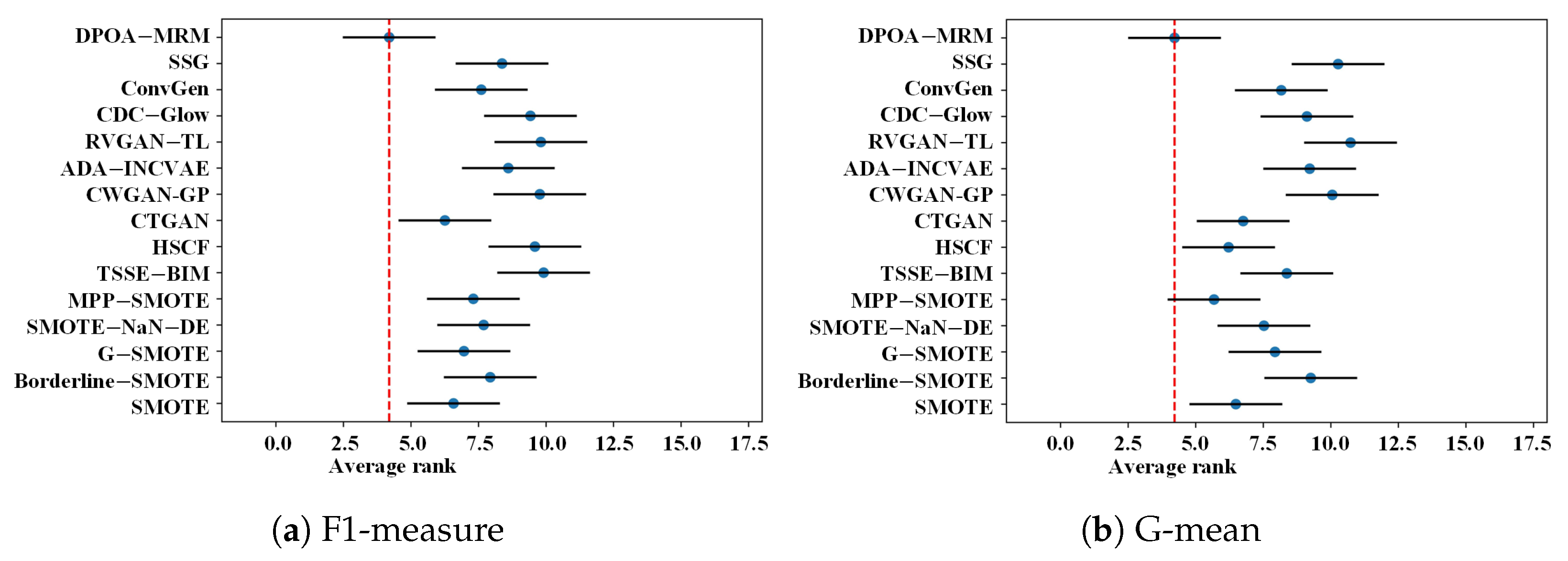

4.5. Nemenyi Post Hoc Test

4.6. Parameter Sensitivity Experiments

4.7. Ablation Study

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. The Supplementary Experimental Results

| Dataset | SMOTE | Borderline-SMOTE | G-SMOTE | SMOTE-NaN-DE | MPP-SMOTE | TSSE-BIM | HSCF | CTGAN | CWGAN-GP | ADA-INCVAE | RVGAN-TL | CDC-Glow | ConvGeN | SSG | DPOA-MRM |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ecoli-0vs1 | 0.9871 | 0.9862 | 0.9862 | 0.9862 | 0.9806 | 0.9806 | 0.9709 | 0.9871 | 0.9367 | 0.6833 | 0.8966 | 0.4832 | 0.9677 | 0.9798 | 0.9802 |

| wisconsin | 0.9575 | 0.9517 | 0.9534 | 0.9571 | 0.9532 | 0.9422 | 0.9584 | 0.9592 | 0.9386 | 0.9862 | 0.9136 | 0.0000 | 0.9697 | 0.9609 | 0.9617 |

| pima | 0.6663 | 0.6879 | 0.6622 | 0.6639 | 0.6724 | 0.6068 | 0.6721 | 0.6478 | 0.6357 | 0.3383 | 0.0000 | 0.4924 | 0.6825 | 0.6460 | 0.6786 |

| vehicle_2 | 0.9549 | 0.9446 | 0.9482 | 0.9479 | 0.9309 | 0.9442 | 0.8460 | 0.9314 | 0.9074 | 0.6585 | 0.9211 | 0.6555 | 0.9778 | 0.9430 | 0.9752 |

| vehicle_1 | 0.6735 | 0.6773 | 0.6885 | 0.6365 | 0.6648 | 0.5934 | 0.5748 | 0.4778 | 0.5558 | 0.6615 | 0.4151 | 0.7405 | 0.6333 | 0.4209 | 0.6532 |

| vehicle_3 | 0.6390 | 0.6413 | 0.6475 | 0.6119 | 0.6485 | 0.5698 | 0.5523 | 0.3883 | 0.5685 | 0.3667 | 0.0000 | 0.4931 | 0.5862 | 0.3307 | 0.6099 |

| vehicle_0 | 0.9339 | 0.9029 | 0.9175 | 0.9200 | 0.8984 | 0.8919 | 0.7662 | 0.9062 | 0.9055 | 0.4943 | 0.9367 | 0.7937 | 0.9524 | 0.9258 | 0.9520 |

| ecoli_1 | 0.7615 | 0.7644 | 0.7709 | 0.7869 | 0.7697 | 0.7651 | 0.7611 | 0.7946 | 0.6648 | 0.7778 | 0.1111 | 0.6917 | 0.7222 | 0.7760 | 0.8321 |

| new-thyroid1 | 0.9733 | 0.9581 | 0.9581 | 0.9581 | 0.9733 | 0.9581 | 0.9714 | 0.9600 | 0.8700 | 0.7177 | 0.9412 | 0.9303 | 1.0000 | 0.9179 | 0.9647 |

| new-thyroid2 | 0.9733 | 0.9750 | 0.9750 | 0.9750 | 0.9733 | 0.8910 | 0.9407 | 0.9600 | 0.8338 | 0.7357 | 0.8571 | 0.8069 | 1.0000 | 0.9147 | 1.0000 |

| ecoli2 | 0.8678 | 0.8695 | 0.8778 | 0.8786 | 0.8455 | 0.7867 | 0.7428 | 0.8390 | 0.8090 | 0.9724 | 0.1250 | 0.5184 | 0.9091 | 0.8212 | 0.8816 |

| segment0 | 0.9908 | 0.9674 | 0.9893 | 0.9892 | 0.9442 | 0.9804 | 0.9747 | 0.9718 | 0.9862 | 0.8546 | 0.7071 | 0.9426 | 0.9846 | 0.9766 | 0.9909 |

| yeast3 | 0.7314 | 0.7522 | 0.7430 | 0.7651 | 0.7153 | 0.7633 | 0.7286 | 0.7063 | 0.7372 | 0.0333 | 0.0000 | 0.1665 | 0.7222 | 0.7633 | 0.7948 |

| ecoli3 | 0.6738 | 0.6673 | 0.6515 | 0.6734 | 0.6522 | 0.6849 | 0.5251 | 0.6490 | 0.6236 | 0.7012 | 0.0000 | 0.7351 | 0.5714 | 0.6333 | 0.7029 |

| page-blocks0 | 0.7387 | 0.7284 | 0.7357 | 0.7441 | 0.7251 | 0.8389 | 0.6795 | 0.7471 | 0.6948 | 0.7611 | 0.4848 | 0.7589 | 0.6230 | 0.6514 | 0.8533 |

| yeast-2_vs_4 | 0.7622 | 0.7781 | 0.7470 | 0.7589 | 0.7053 | 0.7296 | 0.7322 | 0.6991 | 0.7346 | 0.4446 | 0.0000 | 0.6871 | 0.7692 | 0.7575 | 0.8225 |

| ecoli-0-6-7_vs_3-5 | 0.7795 | 0.6976 | 0.8208 | 0.7905 | 0.6788 | 0.6929 | 0.6656 | 0.7422 | 0.7722 | 0.8000 | 0.3333 | 0.3508 | 0.7273 | 0.8006 | 0.7802 |

| yeast-0-2-5-6_vs_3-7-8-9 | 0.5830 | 0.4370 | 0.6199 | 0.6007 | 0.5797 | 0.5593 | 0.6286 | 0.5565 | 0.3627 | 0.9291 | 0.0000 | 0.9553 | 0.6154 | 0.5525 | 0.6735 |

| yeast-0-2-5-7-9_vs_3-6-8 | 0.8010 | 0.6413 | 0.8229 | 0.8000 | 0.7693 | 0.7396 | 0.7793 | 0.7261 | 0.6625 | 0.4626 | 0.0000 | 0.7206 | 0.8571 | 0.8307 | 0.8231 |

| glass-0-4_vs_5 | 0.6333 | 0.7000 | 0.8000 | 0.8000 | 0.6667 | 0.9600 | 0.6867 | 0.8286 | 0.5850 | 0.7524 | 0.0000 | 0.7333 | 0.6667 | 0.1333 | 1.0000 |

| ecoli-0-1-4-7_vs_5-6 | 0.7805 | 0.7933 | 0.8378 | 0.8352 | 0.6241 | 0.7543 | 0.7582 | 0.7110 | 0.5239 | 0.0500 | 0.0000 | 0.4860 | 0.7500 | 0.8296 | 0.8039 |

| glass4 | 0.8076 | 0.7933 | 0.7533 | 0.7533 | 0.7257 | 0.8400 | 0.4909 | 0.7671 | 0.6500 | 0.0364 | 0.5000 | 0.1662 | 0.8000 | 0.2133 | 0.8305 |

| ecoli4 | 0.7711 | 0.8111 | 0.7653 | 0.7875 | 0.8232 | 0.6859 | 0.7388 | 0.8833 | 0.7561 | 0.8483 | 0.6667 | 0.7776 | 0.7500 | 0.8476 | 0.8292 |

| page-blocks-1-3_vs_4 | 0.9071 | 0.9119 | 0.8799 | 0.8825 | 0.9051 | 0.9483 | 0.5136 | 0.6205 | 0.5578 | 0.7265 | 0.7500 | 0.8460 | 0.9091 | 0.6032 | 0.9846 |

| abalone9-18 | 0.3152 | 0.3164 | 0.3183 | 0.3680 | 0.3814 | 0.2881 | 0.2165 | 0.2824 | 0.2435 | 0.0803 | 0.0000 | 0.3475 | 0.3529 | 0.0000 | 0.4340 |

| MEU-Mobile KSD | 0.8168 | 0.8520 | 0.8373 | 0.8489 | 0.8279 | 0.8646 | 0.9240 | 0.8924 | 0.6923 | 0.6504 | 0.9000 | 0.8514 | 0.8421 | 0.9097 | 0.9204 |

| yeast-2_vs_8 | 0.3413 | 0.5524 | 0.3484 | 0.3817 | 0.6381 | 0.4019 | 0.6681 | 0.6276 | 0.6000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.1967 | 0.4000 | 0.6857 | 0.7405 |

| flare-F | 0.2676 | 0.3212 | 0.2545 | 0.2486 | 0.2522 | 0.2073 | 0.1835 | 0.2770 | 0.1349 | 0.6760 | 0.0000 | 0.6251 | 0.2727 | 0.1812 | 0.2503 |

| kr-vs-k-zero-one_vs_draw | 0.2441 | 0.0000 | 0.2114 | 0.1520 | 0.3027 | 0.3721 | 0.4660 | 0.7938 | 0.6737 | 0.2903 | 0.3000 | 0.7233 | 0.2785 | 0.8651 | 0.0000 |

| kr-vs-k-one_vs_fifteen | 0.5725 | 0.8147 | 0.7183 | 0.2551 | 0.5865 | 0.8148 | 0.8670 | 0.9935 | 0.6689 | 0.0364 | 1.0000 | 0.2295 | 0.5957 | 1.0000 | 0.8167 |

| winequality-red-4 | 0.1644 | 0.1460 | 0.1895 | 0.1828 | 0.1561 | 0.1819 | 0.1724 | 0.2030 | 0.0959 | 0.3133 | 0.0000 | 0.4381 | 0.1277 | 0.0000 | 0.1783 |

| yeast-1-2-8-9_vs_7 | 0.0869 | 0.3034 | 0.1298 | 0.1399 | 0.1263 | 0.2248 | 0.1836 | 0.1944 | 0.0606 | 0.9452 | 0.0000 | 0.9665 | 0.2353 | 0.0500 | 0.3248 |

| abalone-3_vs_11 | 0.9429 | 0.9714 | 0.9714 | 0.9714 | 0.8548 | 0.9714 | 0.4261 | 0.9714 | 0.9214 | 0.0823 | 1.0000 | 0.3296 | 0.8000 | 1.0000 | 0.9714 |

| kr-vs-k-three_vs_eleven | 0.1540 | 0.0000 | 0.1543 | 0.1543 | 0.1540 | 0.1596 | 0.8159 | 0.9111 | 0.7866 | 0.2917 | 0.9744 | 0.6500 | 0.1498 | 0.9943 | 0.0000 |

| ecoli-0-1-3-7_vs_2-6 | 0.4667 | 0.7333 | 0.4143 | 0.4276 | 0.3467 | 0.7133 | 0.6333 | 0.7133 | 0.6000 | 0.9714 | 0.0000 | 1.0000 | 0.6667 | 0.7333 | 0.5800 |

| abalone-17_vs_7-8-9-10 | 0.2042 | 0.2882 | 0.2391 | 0.2365 | 0.2185 | 0.2875 | 0.1212 | 0.1625 | 0.1565 | 0.8942 | 0.0000 | 0.8414 | 0.2174 | 0.1642 | 0.3235 |

| yeast6 | 0.4080 | 0.4552 | 0.4123 | 0.3990 | 0.3225 | 0.4196 | 0.2876 | 0.3697 | 0.4218 | 0.9617 | 0.0000 | 0.9506 | 0.6087 | 0.5063 | 0.6467 |

| poker-8-9vs6 | 0.8421 | 0.7365 | 0.7587 | 0.8421 | 0.6511 | 0.2792 | 0.9278 | 0.1931 | 0.3459 | 0.2464 | 1.0000 | 0.3496 | 0.8000 | 0.5810 | 0.7336 |

| poker-8vs6 | 0.8933 | 0.7029 | 0.6733 | 0.8429 | 0.7481 | 0.3841 | 0.8029 | 0.0995 | 0.2111 | 0.8077 | 1.0000 | 0.9314 | 0.6667 | 0.3133 | 0.7867 |

| Average | 0.6684 | 0.6726 | 0.6714 | 0.6655 | 0.6511 | 0.6584 | 0.6501 | 0.6704 | 0.6124 | 0.5651 | 0.4034 | 0.6247 | 0.6708 | 0.6465 | 0.7201 |

| Average Friedman-rank | 7.0897 | 7.0128 | 6.7308 | 6.5641 | 8.5385 | 7.8077 | 9.0513 | 7.6282 | 10.7692 | 8.8077 | 11.8590 | 8.7692 | 7.1026 | 8.0385 | 4.2308 |

| Dataset | SMOTE | Borderline-SMOTE | G-SMOTE | SMOTE-NaN-DE | MPP-SMOTE | TSSE-BIM | HSCF | CTGAN | CWGAN-GP | ADA-INCVAE | RVGAN-TL | CDC-Glow | ConvGeN | SSG | DPOA-MRM |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ecoli-0vs1 | 0.9873 | 0.9864 | 0.9864 | 0.9864 | 0.9837 | 0.9835 | 0.9721 | 0.9873 | 0.9418 | 0.6916 | 0.9014 | 0.5323 | 0.9682 | 0.9801 | 0.9833 |

| wisconsin | 0.9724 | 0.9677 | 0.9679 | 0.9702 | 0.9683 | 0.9587 | 0.9706 | 0.9717 | 0.9590 | 0.9901 | 0.9350 | 0.0000 | 0.9830 | 0.9727 | 0.9774 |

| pima | 0.7406 | 0.7572 | 0.7370 | 0.7381 | 0.7452 | 0.6911 | 0.7461 | 0.7255 | 0.7113 | 0.6894 | 0.0000 | 0.9039 | 0.7519 | 0.7156 | 0.7457 |

| vehicle_2 | 0.9747 | 0.9725 | 0.9695 | 0.9680 | 0.9683 | 0.9648 | 0.9277 | 0.9459 | 0.9536 | 0.7288 | 0.9239 | 0.7307 | 0.9920 | 0.9500 | 0.9867 |

| vehicle_1 | 0.8094 | 0.8147 | 0.8216 | 0.7693 | 0.8006 | 0.7238 | 0.7207 | 0.5963 | 0.6813 | 0.7990 | 0.5204 | 0.9253 | 0.7766 | 0.5342 | 0.7802 |

| vehicle_3 | 0.7864 | 0.7889 | 0.7940 | 0.7573 | 0.7948 | 0.7012 | 0.7076 | 0.5160 | 0.7035 | 0.3993 | 0.0000 | 0.7565 | 0.7402 | 0.4604 | 0.7540 |

| vehicle_0 | 0.9730 | 0.9604 | 0.9625 | 0.9666 | 0.9613 | 0.9322 | 0.9006 | 0.9507 | 0.9517 | 0.5906 | 0.9717 | 0.9512 | 0.9845 | 0.9556 | 0.9792 |

| ecoli_1 | 0.8735 | 0.8738 | 0.8839 | 0.8757 | 0.8839 | 0.8564 | 0.8860 | 0.8907 | 0.7634 | 0.8693 | 0.2425 | 0.8236 | 0.8385 | 0.8373 | 0.9168 |

| new-thyroid1 | 0.9944 | 0.9798 | 0.9798 | 0.9798 | 0.9944 | 0.9798 | 0.9826 | 0.9916 | 0.9463 | 0.9309 | 0.9856 | 0.9572 | 1.0000 | 0.9232 | 0.9915 |

| new-thyroid2 | 0.9944 | 0.9944 | 0.9944 | 0.9944 | 0.9944 | 0.9400 | 0.9529 | 0.9916 | 0.8998 | 0.9315 | 0.8660 | 0.9492 | 1.0000 | 0.9215 | 1.0000 |

| ecoli2 | 0.9410 | 0.9169 | 0.9425 | 0.9425 | 0.9358 | 0.8617 | 0.9077 | 0.9339 | 0.9110 | 0.9731 | 0.2582 | 0.0000 | 0.9451 | 0.8816 | 0.9370 |

| segment0 | 0.9921 | 0.9880 | 0.9931 | 0.9918 | 0.9901 | 0.9904 | 0.9893 | 0.9888 | 0.9888 | 0.9204 | 0.7395 | 0.9647 | 0.9847 | 0.9896 | 0.9934 |

| yeast3 | 0.8950 | 0.8990 | 0.9000 | 0.9038 | 0.9068 | 0.8816 | 0.8864 | 0.8986 | 0.8364 | 0.0603 | 0.0000 | 0.4830 | 0.8656 | 0.8410 | 0.9221 |

| ecoli3 | 0.8958 | 0.8835 | 0.8722 | 0.8813 | 0.9009 | 0.8048 | 0.7655 | 0.8789 | 0.8187 | 0.7999 | 0.0000 | 0.8238 | 0.8630 | 0.7731 | 0.8667 |

| page-blocks0 | 0.9250 | 0.9215 | 0.9199 | 0.9207 | 0.9194 | 0.9482 | 0.8751 | 0.8739 | 0.8097 | 0.9154 | 0.5759 | 0.9512 | 0.8479 | 0.7907 | 0.9401 |

| yeast-2_vs_4 | 0.8974 | 0.8733 | 0.8936 | 0.8955 | 0.8703 | 0.8733 | 0.8493 | 0.8694 | 0.8659 | 0.5625 | 0.0000 | 0.7921 | 0.9275 | 0.8243 | 0.9169 |

| ecoli-0-6-7_vs_3-5 | 0.8634 | 0.8000 | 0.8810 | 0.8759 | 0.8685 | 0.7652 | 0.8546 | 0.8962 | 0.8617 | 0.8000 | 0.4472 | 0.7388 | 0.8718 | 0.8253 | 0.8602 |

| yeast-0-2-5-6_vs_3-7-8-9 | 0.7647 | 0.7424 | 0.7875 | 0.7891 | 0.7990 | 0.7505 | 0.7842 | 0.7893 | 0.5325 | 0.9583 | 0.0000 | 0.9737 | 0.8540 | 0.6555 | 0.7949 |

| yeast-0-2-5-7-9_vs_3-6-8 | 0.8829 | 0.8485 | 0.9001 | 0.8970 | 0.9019 | 0.8508 | 0.8992 | 0.9124 | 0.7998 | 0.5692 | 0.0000 | 0.8228 | 0.9381 | 0.8809 | 0.8939 |

| glass-0-4_vs_5 | 0.6784 | 0.7615 | 0.8243 | 0.8243 | 0.8556 | 0.9936 | 0.9501 | 0.9618 | 0.6886 | 0.8660 | 0.0000 | 0.8706 | 0.7071 | 0.1414 | 1.0000 |

| ecoli-0-1-4-7_vs_5-6 | 0.8797 | 0.8774 | 0.9066 | 0.9068 | 0.8598 | 0.8397 | 0.8524 | 0.9458 | 0.6746 | 0.1103 | 0.0000 | 0.7663 | 0.7746 | 0.8870 | 0.9034 |

| glass4 | 0.9480 | 0.9053 | 0.9028 | 0.9028 | 0.9404 | 0.9216 | 0.8905 | 0.8924 | 0.7104 | 0.0665 | 0.5774 | 0.5688 | 0.8165 | 0.2555 | 0.9796 |

| ecoli4 | 0.8803 | 0.8835 | 0.9041 | 0.9057 | 0.9373 | 0.8117 | 0.9286 | 0.9671 | 0.8889 | 0.9359 | 0.7071 | 0.9022 | 0.8592 | 0.8610 | 0.9374 |

| page-blocks-1-3_vs_4 | 0.9771 | 0.9618 | 0.9560 | 0.9559 | 0.9770 | 0.9803 | 0.8139 | 0.7781 | 0.6539 | 0.9291 | 0.7746 | 0.9473 | 0.9129 | 0.6611 | 0.9989 |

| abalone9-18 | 0.7637 | 0.5396 | 0.7246 | 0.7734 | 0.7352 | 0.5792 | 0.4180 | 0.4498 | 0.5134 | 0.1992 | 0.0000 | 0.6924 | 0.7582 | 0.0000 | 0.6506 |

| MEU-Mobile KSD | 0.8465 | 0.8702 | 0.8578 | 0.8686 | 0.9005 | 0.9335 | 0.9270 | 0.9146 | 0.8899 | 0.7136 | 0.9045 | 0.9039 | 0.8922 | 0.9148 | 0.9467 |

| yeast-2_vs_8 | 0.6050 | 0.6509 | 0.6360 | 0.7028 | 0.7567 | 0.6975 | 0.7283 | 0.7565 | 0.7203 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.5288 | 0.5000 | 0.7381 | 0.8008 |

| flare-F | 0.7559 | 0.7025 | 0.6958 | 0.7522 | 0.7252 | 0.6202 | 0.7736 | 0.8155 | 0.2727 | 0.8080 | 0.0000 | 0.8738 | 0.7565 | 0.3074 | 0.3976 |

| kr-vs-k-zero-one_vs_draw | 0.7727 | 0.0000 | 0.7917 | 0.7344 | 0.7931 | 0.7888 | 0.9559 | 0.9846 | 0.7990 | 0.4173 | 0.4201 | 0.8910 | 0.6927 | 0.9516 | 0.0000 |

| kr-vs-k-one_vs_fifteen | 0.8601 | 0.8301 | 0.8256 | 0.8358 | 0.8510 | 0.8303 | 0.9942 | 0.9998 | 0.9126 | 0.0665 | 1.0000 | 0.6457 | 0.9169 | 1.0000 | 0.8311 |

| winequality-red-4 | 0.6056 | 0.3757 | 0.5972 | 0.6360 | 0.6468 | 0.6402 | 0.6743 | 0.4739 | 0.3021 | 0.3569 | 0.0000 | 0.4883 | 0.4937 | 0.0000 | 0.4730 |

| yeast-1-2-8-9_vs_7 | 0.4338 | 0.6240 | 0.6116 | 0.5504 | 0.5652 | 0.7098 | 0.6723 | 0.7000 | 0.2186 | 0.9524 | 0.0000 | 0.9820 | 0.7614 | 0.0814 | 0.4755 |

| abalone-3_vs_11 | 0.9979 | 0.9990 | 0.9990 | 0.9990 | 0.9938 | 0.9990 | 0.8522 | 0.9990 | 0.9969 | 0.2120 | 1.0000 | 0.6971 | 0.8165 | 1.0000 | 0.9990 |

| kr-vs-k-three_vs_eleven | 0.8293 | 0.0000 | 0.8293 | 0.8293 | 0.8293 | 0.7801 | 0.9747 | 0.9968 | 0.9049 | 0.3536 | 0.9991 | 0.7581 | 0.8136 | 0.9998 | 0.0000 |

| ecoli-0-1-3-7_vs_2-6 | 0.7304 | 0.7414 | 0.7248 | 0.7267 | 0.7198 | 0.8771 | 0.7378 | 0.9314 | 0.7926 | 0.9990 | 0.0000 | 1.0000 | 0.7071 | 0.7414 | 0.7851 |

| abalone-17_vs_7-8-9-10 | 0.8054 | 0.7124 | 0.8551 | 0.8541 | 0.7848 | 0.7202 | 0.2573 | 0.3347 | 0.4105 | 0.9157 | 0.0000 | 0.8828 | 0.8399 | 0.3088 | 0.5917 |

| yeast6 | 0.8263 | 0.7969 | 0.8409 | 0.8399 | 0.8383 | 0.7944 | 0.8860 | 0.8762 | 0.6832 | 0.9775 | 0.0000 | 0.9650 | 0.9844 | 0.6726 | 0.8178 |

| poker-8-9vs6 | 0.8603 | 0.7737 | 0.7948 | 0.8603 | 0.8325 | 0.7452 | 0.9338 | 0.7191 | 0.5186 | 0.5997 | 1.0000 | 0.8804 | 0.8165 | 0.6520 | 0.8098 |

| poker-8vs6 | 0.9047 | 0.7097 | 0.7202 | 0.8619 | 0.8763 | 0.8693 | 0.8252 | 0.7484 | 0.3762 | 0.9101 | 1.0000 | 0.9742 | 0.7071 | 0.3569 | 0.8094 |

| Average | 0.8493 | 0.7868 | 0.8509 | 0.8570 | 0.8617 | 0.8356 | 0.8365 | 0.8424 | 0.7401 | 0.6556 | 0.4295 | 0.7769 | 0.8374 | 0.6986 | 0.8063 |

| Average Friedman-rank | 6.1410 | 8.2564 | 6.5897 | 6.3205 | 5.7308 | 8.4231 | 7.6667 | 6.4359 | 10.9487 | 10.0128 | 12.1154 | 8.3333 | 7.0385 | 10.3462 | 5.6410 |

| Dataset | SMOTE | Borderline-SMOTE | G-SMOTE | SMOTE-NaN-DE | MPP-SMOTE | TSSE-BIM | HSCF | CTGAN | CWGAN-GP | ADA-INCVAE | RVGAN-TL | CDC-Glow | ConvGeN | SSG | DPOA-MRM |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ecoli-0vs1 | 0.9810 | 0.9741 | 0.9676 | 0.9862 | 0.9746 | 0.9738 | 0.9798 | 0.9750 | 0.9583 | 0.6540 | 0.9333 | 0.7274 | 0.9375 | 0.9595 | 0.9802 |

| wisconsin | 0.9547 | 0.9505 | 0.9479 | 0.9339 | 0.9546 | 0.9469 | 0.9325 | 0.9555 | 0.9438 | 0.9877 | 0.9268 | 0.0000 | 0.9592 | 0.9517 | 0.9617 |

| pima | 0.6809 | 0.6644 | 0.6491 | 0.6229 | 0.6754 | 0.6186 | 0.6631 | 0.6404 | 0.6419 | 0.5800 | 0.6000 | 0.4793 | 0.6903 | 0.6170 | 0.6786 |

| vehicle_2 | 0.9656 | 0.9589 | 0.9590 | 0.9653 | 0.9642 | 0.9509 | 0.8809 | 0.9464 | 0.9596 | 0.6499 | 0.9512 | 0.6557 | 0.9556 | 0.9622 | 0.9752 |

| vehicle_1 | 0.6231 | 0.6341 | 0.6478 | 0.5879 | 0.6267 | 0.5846 | 0.6201 | 0.6053 | 0.5583 | 0.7979 | 0.5102 | 0.8572 | 0.6024 | 0.5279 | 0.6532 |

| vehicle_3 | 0.6409 | 0.6081 | 0.6297 | 0.5478 | 0.6217 | 0.5354 | 0.6170 | 0.5455 | 0.5851 | 0.6921 | 0.5238 | 0.4869 | 0.6000 | 0.4940 | 0.6099 |

| vehicle_0 | 0.9205 | 0.9294 | 0.9271 | 0.9057 | 0.9264 | 0.9043 | 0.7486 | 0.9175 | 0.9108 | 0.8061 | 0.8780 | 0.7516 | 0.8500 | 0.9131 | 0.9520 |

| ecoli_1 | 0.7879 | 0.7642 | 0.7954 | 0.8099 | 0.7875 | 0.7468 | 0.7709 | 0.7879 | 0.7450 | 0.7801 | 0.7368 | 0.6232 | 0.6667 | 0.7840 | 0.8321 |

| new-thyroid1 | 0.9559 | 0.8824 | 0.8824 | 0.9200 | 0.9081 | 0.9179 | 0.9119 | 0.9483 | 0.8667 | 0.8173 | 0.9412 | 0.9256 | 1.0000 | 0.9196 | 0.9647 |

| new-thyroid2 | 0.9014 | 0.9263 | 0.9596 | 0.9138 | 0.9314 | 0.9008 | 0.8898 | 0.9090 | 0.9129 | 0.8173 | 0.9333 | 0.8542 | 0.9231 | 0.9513 | 1.0000 |

| ecoli2 | 0.8232 | 0.7869 | 0.7652 | 0.7571 | 0.7949 | 0.8199 | 0.6915 | 0.8611 | 0.7867 | 0.9613 | 0.7692 | 0.0000 | 0.7619 | 0.8246 | 0.8816 |

| segment0 | 0.9879 | 0.9802 | 0.9879 | 0.9832 | 0.9836 | 0.9804 | 0.9587 | 0.9880 | 0.9830 | 0.9310 | 0.9767 | 0.8470 | 0.9848 | 0.9863 | 0.9909 |

| yeast3 | 0.7704 | 0.7691 | 0.7711 | 0.7762 | 0.7892 | 0.7310 | 0.7755 | 0.7863 | 0.7542 | 0.0558 | 0.6667 | 0.1901 | 0.6667 | 0.7614 | 0.7948 |

| ecoli3 | 0.6240 | 0.6073 | 0.5603 | 0.6321 | 0.6237 | 0.6032 | 0.5560 | 0.5295 | 0.5947 | 0.7430 | 0.5455 | 0.7248 | 0.7500 | 0.5862 | 0.7029 |

| page-blocks0 | 0.8520 | 0.8427 | 0.8511 | 0.8506 | 0.8242 | 0.8415 | 0.6681 | 0.8621 | 0.7911 | 0.7919 | 0.8502 | 0.6943 | 0.7778 | 0.8744 | 0.8533 |

| yeast-2_vs_4 | 0.7729 | 0.7978 | 0.7619 | 0.7729 | 0.7453 | 0.7253 | 0.6484 | 0.7825 | 0.7636 | 0.5427 | 0.6154 | 0.6876 | 0.7500 | 0.7248 | 0.8225 |

| ecoli-0-6-7_vs_3-5 | 0.6795 | 0.7288 | 0.7457 | 0.6476 | 0.7105 | 0.7067 | 0.6374 | 0.7881 | 0.7500 | 0.5111 | 0.6667 | 0.5467 | 0.8333 | 0.7392 | 0.7802 |

| yeast-0-2-5-6_vs_3-7-8-9 | 0.5708 | 0.5030 | 0.5700 | 0.5729 | 0.5745 | 0.5591 | 0.4892 | 0.6256 | 0.4883 | 0.9280 | 0.6486 | 0.9500 | 0.7222 | 0.5858 | 0.6735 |

| yeast-0-2-5-7-9_vs_3-6-8 | 0.7903 | 0.7999 | 0.8131 | 0.8242 | 0.7516 | 0.7732 | 0.7210 | 0.8036 | 0.7128 | 0.5673 | 0.7273 | 0.7032 | 0.8095 | 0.8157 | 0.8231 |

| glass-0-4_vs_5 | 0.9333 | 0.9600 | 0.9600 | 0.9600 | 0.8533 | 0.9600 | 0.8533 | 0.8933 | 0.7508 | 0.7202 | 0.6667 | 0.7254 | 1.0000 | 0.9200 | 1.0000 |

| ecoli-0-1-4-7_vs_5-6 | 0.8244 | 0.7628 | 0.8099 | 0.8378 | 0.7338 | 0.7230 | 0.6258 | 0.7611 | 0.7335 | 0.3614 | 0.6667 | 0.5049 | 0.6667 | 0.7544 | 0.8039 |

| glass4 | 0.8314 | 0.8648 | 0.8629 | 0.8914 | 0.6214 | 0.7600 | 0.5483 | 0.7542 | 0.7062 | 0.1531 | 0.6667 | 0.1982 | 0.8000 | 0.7133 | 0.8305 |

| ecoli4 | 0.8159 | 0.7286 | 0.7800 | 0.7244 | 0.8349 | 0.7357 | 0.6195 | 0.8883 | 0.7580 | 0.7533 | 0.7500 | 0.7520 | 0.5455 | 0.6514 | 0.8292 |

| page-blocks-1-3_vs_4 | 0.9636 | 0.9513 | 0.9692 | 0.9692 | 0.9205 | 0.9136 | 0.5639 | 0.8791 | 0.8426 | 0.7412 | 0.9091 | 0.7344 | 1.0000 | 0.9331 | 0.9846 |

| abalone9-18 | 0.2828 | 0.3480 | 0.3652 | 0.3520 | 0.3129 | 0.3172 | 0.1935 | 0.3868 | 0.2859 | 0.1918 | 0.5000 | 0.3736 | 0.1667 | 0.3459 | 0.4340 |

| MEU-Mobile KSD | 0.9097 | 0.8962 | 0.8992 | 0.8992 | 0.8610 | 0.8637 | 0.8044 | 0.8960 | 0.6390 | 0.5719 | 0.8421 | 0.7205 | 0.8889 | 0.8836 | 0.9204 |

| yeast-2_vs_8 | 0.4523 | 0.4610 | 0.5311 | 0.4527 | 0.5229 | 0.4095 | 0.5302 | 0.6395 | 0.6444 | 0.1387 | 0.3333 | 0.2065 | 0.4000 | 0.5790 | 0.7405 |

| flare-F | 0.2412 | 0.2779 | 0.1868 | 0.2102 | 0.2175 | 0.2425 | 0.1584 | 0.2526 | 0.1531 | 0.6252 | 0.0000 | 0.6157 | 0.0000 | 0.1905 | 0.2503 |

| kr-vs-k-zero-one_vs_draw | 0.2441 | 0.0000 | 0.2227 | 0.1520 | 0.3027 | 0.3728 | 0.1692 | 0.9395 | 0.7870 | 0.6619 | 0.9714 | 0.6700 | 0.0000 | 0.9656 | 0.0000 |

| kr-vs-k-one_vs_fifteen | 0.5808 | 0.8147 | 0.7183 | 0.2551 | 0.7225 | 0.8175 | 0.2911 | 1.0000 | 0.8417 | 0.1895 | 1.0000 | 0.2561 | 0.8966 | 1.0000 | 0.8167 |

| winequality-red-4 | 0.1421 | 0.1525 | 0.1319 | 0.1673 | 0.1594 | 0.1640 | 0.1663 | 0.0882 | 0.0963 | 0.3800 | 0.2222 | 0.4500 | 0.2000 | 0.0641 | 0.1783 |

| yeast-1-2-8-9_vs_7 | 0.1578 | 0.3161 | 0.2398 | 0.1701 | 0.2230 | 0.1799 | 0.2722 | 0.2533 | 0.3207 | 0.9631 | 0.2500 | 0.9623 | 0.6000 | 0.3333 | 0.3248 |

| abalone-3_vs_11 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | 0.9429 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | 0.9714 | 0.1866 | 1.0000 | 0.3122 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | 0.9714 |

| kr-vs-k-three_vs_eleven | 0.1540 | 0.0000 | 0.1543 | 0.1543 | 0.1540 | 0.1568 | 0.3102 | 1.0000 | 0.7612 | 0.8286 | 0.9744 | 0.7171 | 0.0000 | 1.0000 | 0.0000 |

| ecoli-0-1-3-7_vs_2-6 | 0.3733 | 0.5467 | 0.4667 | 0.6333 | 0.3733 | 0.3905 | 0.4733 | 0.5467 | 0.5778 | 0.9714 | 0.6667 | 0.9600 | 0.4000 | 0.3467 | 0.5800 |

| abalone-17_vs_7-8-9-10 | 0.3471 | 0.3521 | 0.3698 | 0.3325 | 0.3077 | 0.2542 | 0.2085 | 0.3123 | 0.1730 | 0.6421 | 0.3750 | 0.6773 | 0.3529 | 0.3135 | 0.3235 |

| yeast6 | 0.4229 | 0.4889 | 0.5247 | 0.4629 | 0.3899 | 0.3622 | 0.3684 | 0.5651 | 0.4964 | 0.9416 | 0.3077 | 0.9401 | 0.4615 | 0.4799 | 0.6467 |

| poker-8-9vs6 | 0.8874 | 0.8833 | 0.5087 | 0.9278 | 0.9500 | 0.1611 | 0.8556 | 0.4254 | 0.7087 | 0.5105 | 0.3333 | 0.6818 | 0.5000 | 0.4421 | 0.7336 |

| poker-8vs6 | 0.9714 | 0.6648 | 0.4833 | 0.8648 | 0.9429 | 0.2526 | 0.7629 | 0.3400 | 0.5800 | 0.9379 | 0.4000 | 0.8778 | 1.0000 | 0.3514 | 0.7867 |

| Average | 0.6877 | 0.6815 | 0.6763 | 0.6776 | 0.6799 | 0.6374 | 0.6137 | 0.7200 | 0.6804 | 0.6432 | 0.6727 | 0.6164 | 0.6697 | 0.6986 | 0.7201 |

| Average Friedman-rank | 6.5256 | 7.3333 | 6.8205 | 7.0385 | 7.7821 | 9.8205 | 10.6667 | 6.4487 | 9.3846 | 9.1795 | 9.6282 | 9.7436 | 7.7949 | 7.8462 | 3.9872 |

| Dataset | SMOTE | Borderline-SMOTE | G-SMOTE | SMOTE-NaN-DE | MPP-SMOTE | TSSE-BIM | HSCF | CTGAN | CWGAN-GP | ADA-INCVAE | RVGAN-TL | CDC-Glow | ConvGeN | SSG | DPOA-MRM |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ecoli-0vs1 | 0.9839 | 0.9795 | 0.9761 | 0.9864 | 0.9803 | 0.9798 | 0.9831 | 0.9806 | 0.9694 | 0.7938 | 0.9354 | 0.9009 | 0.9514 | 0.9663 | 0.9833 |

| wisconsin | 0.9674 | 0.9640 | 0.9600 | 0.9528 | 0.9674 | 0.9626 | 0.9478 | 0.9694 | 0.9577 | 0.9916 | 0.9476 | 0.0000 | 0.9727 | 0.9640 | 0.9774 |

| pima | 0.7536 | 0.7385 | 0.7263 | 0.7037 | 0.7490 | 0.7009 | 0.7344 | 0.7196 | 0.7193 | 0.7739 | 0.6733 | 0.8531 | 0.7601 | 0.6977 | 0.7457 |

| vehicle_2 | 0.9758 | 0.9735 | 0.9750 | 0.9759 | 0.9812 | 0.9749 | 0.9470 | 0.9704 | 0.9796 | 0.7251 | 0.9677 | 0.7315 | 0.9767 | 0.9718 | 0.9867 |

| vehicle_1 | 0.7495 | 0.7547 | 0.7675 | 0.7149 | 0.7548 | 0.7173 | 0.7602 | 0.7116 | 0.6842 | 0.8688 | 0.6829 | 0.9433 | 0.7107 | 0.6500 | 0.7802 |

| vehicle_3 | 0.7643 | 0.7423 | 0.7573 | 0.6886 | 0.7534 | 0.6780 | 0.7605 | 0.6638 | 0.7104 | 0.7054 | 0.6159 | 0.6818 | 0.7078 | 0.6211 | 0.7540 |

| vehicle_0 | 0.9567 | 0.9635 | 0.9560 | 0.9451 | 0.9671 | 0.9432 | 0.8824 | 0.9480 | 0.9519 | 0.9262 | 0.9434 | 0.9095 | 0.9004 | 0.9409 | 0.9792 |

| ecoli_1 | 0.8747 | 0.8628 | 0.8791 | 0.8922 | 0.8802 | 0.8448 | 0.8952 | 0.8569 | 0.8166 | 0.8887 | 0.8429 | 0.7898 | 0.7966 | 0.8618 | 0.9168 |

| new-thyroid1 | 0.9675 | 0.9235 | 0.9235 | 0.9463 | 0.9571 | 0.9595 | 0.9464 | 0.9888 | 0.9462 | 0.9502 | 0.9856 | 0.9368 | 1.0000 | 0.9595 | 0.9915 |

| new-thyroid2 | 0.9187 | 0.9486 | 0.9795 | 0.9466 | 0.9742 | 0.9438 | 0.9405 | 0.9772 | 0.9458 | 0.9502 | 0.9354 | 0.9523 | 0.9258 | 0.9542 | 1.0000 |

| ecoli2 | 0.8994 | 0.8587 | 0.8545 | 0.8519 | 0.8765 | 0.9000 | 0.8620 | 0.9245 | 0.8763 | 0.9700 | 0.8088 | 0.0000 | 0.8377 | 0.8645 | 0.9370 |

| segment0 | 0.9942 | 0.9878 | 0.9929 | 0.9896 | 0.9959 | 0.9878 | 0.9865 | 0.9954 | 0.9844 | 0.9621 | 0.9897 | 0.8867 | 0.9911 | 0.9926 | 0.9934 |

| yeast3 | 0.8940 | 0.8942 | 0.8998 | 0.8922 | 0.8997 | 0.8647 | 0.8895 | 0.8768 | 0.8452 | 0.1201 | 0.7792 | 0.5666 | 0.7516 | 0.8526 | 0.9221 |

| ecoli3 | 0.7973 | 0.7657 | 0.7509 | 0.8317 | 0.8235 | 0.7541 | 0.7818 | 0.6800 | 0.7188 | 0.8145 | 0.6124 | 0.8087 | 0.9028 | 0.7120 | 0.8667 |

| page-blocks0 | 0.9574 | 0.9467 | 0.9503 | 0.9517 | 0.9501 | 0.9251 | 0.9283 | 0.9178 | 0.8748 | 0.9557 | 0.9248 | 0.9257 | 0.9137 | 0.9210 | 0.9401 |

| yeast-2_vs_4 | 0.8908 | 0.8863 | 0.8615 | 0.9102 | 0.8866 | 0.8645 | 0.9104 | 0.8821 | 0.8585 | 0.6639 | 0.7034 | 0.7854 | 0.8849 | 0.8116 | 0.9169 |

| ecoli-0-6-7_vs_3-5 | 0.8494 | 0.8246 | 0.8273 | 0.8133 | 0.8336 | 0.8033 | 0.8394 | 0.8641 | 0.8429 | 0.7264 | 0.7649 | 0.7870 | 0.9747 | 0.7998 | 0.8602 |

| yeast-0-2-5-6_vs_3-7-8-9 | 0.7418 | 0.7058 | 0.7378 | 0.7489 | 0.7779 | 0.7584 | 0.7702 | 0.7297 | 0.6494 | 0.9545 | 0.8217 | 0.9668 | 0.7995 | 0.6936 | 0.7949 |

| yeast-0-2-5-7-9_vs_3-6-8 | 0.8910 | 0.9066 | 0.8938 | 0.9050 | 0.8852 | 0.8699 | 0.8903 | 0.8782 | 0.7965 | 0.6757 | 0.8310 | 0.7993 | 0.9091 | 0.8845 | 0.8939 |

| glass-0-4_vs_5 | 0.9936 | 0.9940 | 0.9940 | 0.9940 | 0.9751 | 0.9940 | 0.9813 | 0.9877 | 0.8995 | 0.8723 | 0.9718 | 0.8935 | 1.0000 | 0.9881 | 1.0000 |

| ecoli-0-1-4-7_vs_5-6 | 0.9078 | 0.8322 | 0.9064 | 0.9274 | 0.8528 | 0.8478 | 0.8373 | 0.8586 | 0.8803 | 0.5000 | 0.7683 | 0.7578 | 0.8725 | 0.8185 | 0.9034 |

| glass4 | 0.9505 | 0.9557 | 0.9558 | 0.9583 | 0.8373 | 0.8723 | 0.9149 | 0.9374 | 0.8135 | 0.2589 | 0.8062 | 0.4829 | 0.8165 | 0.8150 | 0.9796 |

| ecoli4 | 0.8835 | 0.8108 | 0.8392 | 0.8349 | 0.8851 | 0.8515 | 0.8872 | 0.9417 | 0.8770 | 0.8428 | 0.8592 | 0.8580 | 0.8385 | 0.7511 | 0.9374 |

| page-blocks-1-3_vs_4 | 0.9977 | 0.9804 | 0.9977 | 0.9977 | 0.9943 | 0.9769 | 0.9351 | 0.9909 | 0.9477 | 0.9552 | 0.9944 | 0.9311 | 1.0000 | 0.9793 | 0.9989 |

| abalone9-18 | 0.6115 | 0.5586 | 0.6659 | 0.6717 | 0.5718 | 0.6672 | 0.6446 | 0.5847 | 0.4057 | 0.3594 | 0.6302 | 0.7044 | 0.3309 | 0.5019 | 0.6506 |

| MEU-Mobile KSD | 0.9148 | 0.9030 | 0.9046 | 0.9046 | 0.9328 | 0.9126 | 0.8773 | 0.9346 | 0.9015 | 0.7965 | 0.8528 | 0.8498 | 0.8944 | 0.8917 | 0.9467 |

| yeast-2_vs_8 | 0.6863 | 0.5618 | 0.7299 | 0.7481 | 0.6910 | 0.7376 | 0.6820 | 0.7181 | 0.7226 | 0.2679 | 0.4472 | 0.5467 | 0.5000 | 0.6553 | 0.8008 |

| flare-F | 0.5084 | 0.4816 | 0.3663 | 0.6406 | 0.5437 | 0.7143 | 0.7339 | 0.3786 | 0.2589 | 0.7400 | 0.0000 | 0.8336 | 0.0000 | 0.2792 | 0.3976 |

| kr-vs-k-zero-one_vs_draw | 0.7727 | 0.0000 | 0.7944 | 0.7344 | 0.7931 | 0.7913 | 0.7943 | 0.9457 | 0.9073 | 0.7885 | 0.9991 | 0.8108 | 0.0000 | 0.9707 | 0.0000 |

| kr-vs-k-one_vs_fifteen | 0.8460 | 0.8301 | 0.8256 | 0.8358 | 0.8456 | 0.8320 | 0.8859 | 1.0000 | 0.9904 | 0.3292 | 1.0000 | 0.5792 | 0.9014 | 1.0000 | 0.8311 |

| winequality-red-4 | 0.4057 | 0.3127 | 0.3679 | 0.4803 | 0.4668 | 0.5001 | 0.5087 | 0.2291 | 0.3078 | 0.4155 | 0.4069 | 0.5560 | 0.4216 | 0.1233 | 0.4730 |

| yeast-1-2-8-9_vs_7 | 0.3320 | 0.5545 | 0.4149 | 0.4396 | 0.5227 | 0.6106 | 0.4809 | 0.3374 | 0.4518 | 0.9737 | 0.4448 | 0.9805 | 0.7052 | 0.4197 | 0.4755 |

| abalone-3_vs_11 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | 0.9979 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | 0.9990 | 0.3510 | 1.0000 | 0.6303 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | 0.9990 |

| kr-vs-k-three_vs_eleven | 0.8293 | 0.0000 | 0.8293 | 0.8293 | 0.8293 | 0.7992 | 0.9299 | 1.0000 | 0.9532 | 0.9000 | 0.9991 | 0.8971 | 0.0000 | 1.0000 | 0.0000 |

| ecoli-0-1-3-7_vs_2-6 | 0.5352 | 0.6784 | 0.4828 | 0.6816 | 0.5352 | 0.7234 | 0.7304 | 0.7333 | 0.7850 | 0.9990 | 0.7071 | 0.9633 | 0.6941 | 0.5340 | 0.7851 |

| abalone-17_vs_7-8-9-10 | 0.8114 | 0.6914 | 0.7601 | 0.8060 | 0.7331 | 0.7112 | 0.6824 | 0.4815 | 0.3185 | 0.8373 | 0.5748 | 0.8026 | 0.4989 | 0.4763 | 0.5917 |

| yeast6 | 0.7393 | 0.7607 | 0.8175 | 0.7952 | 0.7495 | 0.7729 | 0.8192 | 0.7289 | 0.6681 | 0.9556 | 0.4974 | 0.9565 | 0.6513 | 0.6479 | 0.8178 |

| poker-8-9vs6 | 0.9123 | 0.8916 | 0.5497 | 0.9338 | 0.9549 | 0.7007 | 0.8676 | 0.4843 | 0.7497 | 0.6484 | 0.4472 | 0.9188 | 0.5774 | 0.4603 | 0.8098 |

| poker-8vs6 | 0.9732 | 0.7089 | 0.5717 | 0.8779 | 0.9464 | 0.6531 | 0.7885 | 0.3788 | 0.6421 | 0.9514 | 0.5000 | 0.9375 | 1.0000 | 0.3887 | 0.8094 |

| Average | 0.8318 | 0.7727 | 0.8062 | 0.8394 | 0.8347 | 0.8231 | 0.8369 | 0.7996 | 0.7848 | 0.7477 | 0.7608 | 0.7722 | 0.7531 | 0.7646 | 0.8063 |

| Average Friedman-rank | 6.1923 | 8.5000 | 7.5641 | 6.6026 | 6.1538 | 8.1795 | 7.3974 | 7.7949 | 9.8333 | 8.8718 | 10.6667 | 9.0256 | 8.2949 | 10.4615 | 4.4615 |

References

- He, H.; Garcia, E.A. Learning from Imbalanced Data. IEEE Trans. Knowl. Data Eng. 2009, 21, 1263–1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devarriya, D.; Gulati, C.; Mansharamani, V.; Sakalle, A.; Bhardwaj, A. Unbalanced breast cancer data classification using novel fitness functions in genetic programming. Expert Syst. Appl. 2020, 140, 112866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zavrtanik, V.; Kristan, M.; Skočaj, D. Reconstruction by inpainting for visual anomaly detection. Pattern Recognit. 2021, 112, 107706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, H.; Liu, G.; Zhou, M.; Xie, Y.; Abusorrah, A.; Kang, Q. Optimizing Weighted Extreme Learning Machines for imbalanced classification and application to credit card fraud detection. Neurocomputing 2020, 407, 50–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Huang, S.; Huang, W.; Chang, X. Privacy-Preserving Cost-Sensitive Learning. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 2021, 32, 2105–2116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Wang, S.; Xiao, F. Pattern recognition-based chillers fault detection method using Support Vector Data Description (SVDD). Appl. Energy 2013, 112, 1041–1048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.T.; Ting, K.M.; Zhou, Z.H. Isolation forest. In Proceedings of the 2008 Eighth IEEE International Conference on Data Mining, Pisa, Italy, 15–19 December 2008; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2008; pp. 413–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Mao, Z. Outlier detection based on a dynamic ensemble model: Applied to process monitoring. Inf. Fusion 2019, 51, 244–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chawla, N.V.; Bowyer, K.W.; Hall, L.O.; Kegelmeyer, W.P. SMOTE: Synthetic Minority Over-sampling Technique. J. Artif. Intell. Res. 2002, 16, 321–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krawczyk, B.; Galar, M.; Jeleń, Ł.; Herrera, F. Evolutionary undersampling boosting for imbalanced classification of breast cancer malignancy. Appl. Soft Comput. 2016, 38, 714–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yen, S.J.; Lee, Y.S. Cluster-based under-sampling approaches for imbalanced data distributions. Expert Syst. Appl. 2009, 36, 5718–5727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vuttipittayamongkol, P.; Elyan, E. Neighbourhood-based undersampling approach for handling imbalanced and overlapped data. Inf. Sci. 2020, 509, 47–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kingma, D.P.; Welling, M. Auto-Encoding Variational Bayes. In Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Learning Representations, ICLR 2014—Conference Track Proceedings, Banff, AB, Canada, 14–16 April 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, A.; White, T.; Dumoulin, V.; Arulkumaran, K.; Sengupta, B.; Bharath, A.A. Generative Adversarial Networks: An Overview. IEEE Signal Process. Mag. 2018, 35, 53–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cover, T.M.; Hart, P.E. Nearest Neighbor Pattern Classification. IEEE Trans. Inf. Theory 1967, 13, 21–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, X.; Zheng, Y.; Chen, W.; Zhang, X.; Qi, L.; Fan, Z.; Huang, S. SVDD-based weighted oversampling technique for imbalanced and overlapped dataset learning. Inf. Sci. 2022, 588, 13–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Zhu, Q.; Wu, Q.; Zhang, Z.; Gong, Y.; He, Z.; Zhu, F. SMOTE-NaN-DE: Addressing the noisy and borderline examples problem in imbalanced classification by natural neighbors and differential evolution. Knowl.-Based Syst. 2021, 223, 107056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Z.; Zhang, L.; Zhao, L. Minority-prediction-probability-based oversampling technique for imbalanced learning. Inf. Sci. 2023, 622, 1273–1295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Zheng, M.; Ma, K.; Hu, X. Resampling approach for imbalanced data classification based on class instance density per feature value intervals. Inf. Sci. 2025, 692, 121570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, Q.; Sun, W.; Wang, Z.; Lu, Y.; Li, Y.; Jiang, X. GIS partial discharge data enhancement method based on self attention mechanism VAE-GAN. Glob. Energy Interconnect. 2023, 6, 601–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faber, K.; Corizzo, R.; Sniezynski, B.; Japkowicz, N. VLAD: Task-agnostic VAE-based lifelong anomaly detection. Neural Netw. 2023, 165, 248–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, M.; Li, T.; Zhu, R.; Tang, Y.; Tang, M.; Lin, L.; Ma, Z. Conditional Wasserstein generative adversarial network-gradient penalty-based approach to alleviating imbalanced data classification. Inf. Sci. 2020, 512, 1009–1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, J.; Qi, J.; Shen, C. Binary imbalanced data classification based on diversity oversampling by generative models. Inf. Sci. 2022, 585, 313–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, K.; Wang, X. ADA-INCVAE: Improved data generation using variational autoencoder for imbalanced classification. Appl. Intell. 2021, 52, 2838–2853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, H.; Sun, Y.; Wang, Z.; Huang, N.; Shen, Z.; Cui, X. RGAN-EL: A GAN and ensemble learning-based hybrid approach for imbalanced data classification. Inf. Process. Manag. 2023, 60, 103235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, H.; Sun, Y.; Huang, N.; Shen, Z.; Wang, Z.; Iftekhar, A.; Cui, X. RVGAN-TL: A generative adversarial networks and transfer learning-based hybrid approach for imbalanced data classification. Inf. Sci. 2023, 629, 184–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Zhou, S.; Li, D. Robust multiclass least squares support vector classifier with optimal error distribution. Knowl.-Based Syst. 2021, 215, 106652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, X.; Li, Q.; Guo, W.; Ren, C.; Li, C.; Liu, R.; Zou, J. Self-adaptive cost weights-based support vector machine cost-sensitive ensemble for imbalanced data classification. Inf. Sci. 2019, 487, 31–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svetnik, V.; Liaw, A.; Tong, C.; Culberson, J.C.; Sheridan, R.P.; Feuston, B.P. Random Forest: A Classification and Regression Tool for Compound Classification and QSAR Modeling. J. Chem. Inf. Comput. Sci. 2003, 43, 1947–1958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedman, J.H. Greedy function approximation: A gradient boosting machine. Ann. Stat. 2001, 29, 1189–1232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; Guestrin, C. XGBoost: A Scalable Tree Boosting System. In Proceedings of the 22nd ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, San Francisco, CA, USA, 13–17 August 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Wang, J.; He, K. Majority-to-minority resampling for boosting-based classification under imbalanced data. Appl. Intell. 2023, 53, 4541–4562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehmood, Z.; Asghar, S. Customizing SVM as a base learner with AdaBoost ensemble to learn from multi-class problems: A hybrid approach AdaBoost-MSVM. Knowl.-Based Syst. 2021, 217, 106845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ning, Z.; Guo, C.; Zhang, D. Meta-distribution-based ensemble sampler for imbalanced semi-supervised learning. Pattern Recognit. 2025, 164, 111552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, S.; Gu, Y.; Yu, H.; Yang, X.; Gao, S. RUE: A robust personalized cost assignment strategy for class imbalance cost-sensitive learning. J. King Saud Univ.-Comput. Inf. Sci. 2023, 35, 36–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Wang, B.; Shen, Y.; Wang, P.; Li, Y. An overlapping oriented imbalanced ensemble learning algorithm with weighted projection clustering grouping and consistent fuzzy sample transformation. Inf. Sci. 2023, 637, 118955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Wang, S.; Jin, J.; Tao, H.; Han, C.; Chen, C.P. Hybrid density-based adaptive weighted collaborative representation for imbalanced learning. Appl. Intell. 2024, 54, 4334–4351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Wang, S.; Jin, J.; Zhu, F.; Zhao, L.; Liang, J.; Philip Chen, C. Imbalanced complemented subspace representation with adaptive weight learning. Expert Syst. Appl. 2024, 249, 123555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Yang, M.; Feng, X. Sparse representation or collaborative representation: Which helps face recognition? In Proceedings of the 2011 International Conference on Computer Vision, Barcelona, Spain, 6–13 November 2011; pp. 471–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, X.; Ren, B.; Zhang, H.; Sun, B.; Li, J.; Xu, J.; He, Y.; Li, K. An ensemble imbalanced classification method based on model dynamic selection driven by data partition hybrid sampling. Expert Syst. Appl. 2020, 160, 113660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Li, H.; Fujita, H.; Fu, B.; Ai, W. Class-imbalanced dynamic financial distress prediction based on Adaboost-SVM ensemble combined with SMOTE and time weighting. Inf. Fusion 2020, 54, 128–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, F.; El-Sappagh, S.; Islam, S.R.; Kwak, D.; Ali, A.; Imran, M.; Kwak, K.S. A smart healthcare monitoring system for heart disease prediction based on ensemble deep learning and feature fusion. Inf. Fusion 2020, 63, 208–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Fang, B.; Shang, Z.; Tang, Y. Tackling class overlap and imbalance problems in software defect prediction. Softw. Qual. J. 2018, 26, 97–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez-Martin, M.; Sanchez-Esguevillas, A.; Arribas, J.I.; Carro, B. Supervised contrastive learning over prototype-label embeddings for network intrusion detection. Inf. Fusion 2022, 79, 200–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorena, A.C.; Garcia, L.P.F.; Lehmann, J.; Souto, M.C.P.; Ho, T.K. How Complex Is Your Classification Problem? A Survey on Measuring Classification Complexity. ACM Comput. Surv. 2019, 52, 1–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, S. A new dataset evaluation method based on category overlap. Comput. Biol. Med. 2011, 41, 115–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Walt, C.M. Data Measures that Characterise Classification Problems. Master’s Thesis, University of Pretoria, Pretoria, South Africa, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Kingma, D.P.; Dhariwal, P. Glow: Generative Flow with Invertible 1 × 1 Convolutions. arXiv 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bader-El-Den, M.; Teitei, E.; Perry, T. Biased random forest for dealing with the class imbalance problem. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 2018, 30, 2163–2172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, Q.; Liu, J.W.; Yang, J.P. SWSEL: Sliding Window-based Selective Ensemble Learning for class-imbalance problems. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2023, 121, 105959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.; Wang, W.Y.; Mao, B.H. Borderline-SMOTE: A New Over-Sampling Method in Imbalanced Data Sets Learning. Lect. Notes Comput. Sci. 2005, 3644, 878–887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandhan, T.; Choi, J.Y. Handling imbalanced datasets by partially guided hybrid sampling for pattern recognition. In Proceedings of the 2014 22nd International Conference on Pattern Recognition, Stockholm, Sweden, 24–28 August 2014; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2014; pp. 1449–1453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, L.; Ju, T.; Wang, H.; Lei, M.; Pan, X. Two-step ensemble under-sampling algorithm for massive imbalanced data classification. Inf. Sci. 2024, 665, 120351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Skoularidou, M.; Cuesta-Infante, A.; Veeramachaneni, K. Modeling Tabular data using Conditional GAN. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2019, 32, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Z.; Gao, X.; Chen, W.; Cheng, Y.; Xue, B.; Meng, Z.; Zhang, G.; Fu, S. An imbalanced binary classification method via space mapping using normalizing flows with class discrepancy constraints. Inf. Sci. 2023, 623, 493–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schultz, K.; Bej, S.; Hahn, W.; Wolfien, M.; Srivastava, P.; Wolkenhauer, O. ConvGeN: A convex space learning approach for deep-generative oversampling and imbalanced classification of small tabular datasets. Pattern Recognit. 2024, 147, 110138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahsan, M.M.; Ali, M.S.; Siddique, Z. Enhancing and improving the performance of imbalanced class data using novel GBO and SSG: A comparative analysis. Neural Netw. 2024, 173, 106157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Derrac, J.; Garcia, S.; Sanchez, L.; Herrera, F. Keel data-mining software tool: Data set repository, integration of algorithms and experimental analysis framework. J. Mult. Valued Log. Soft Comput 2015, 17, 255–287. [Google Scholar]

- Barella, V.H.; Garcia, L.P.; de Souto, M.C.; Lorena, A.C.; de Carvalho, A.C. Assessing the data complexity of imbalanced datasets. Inf. Sci. 2021, 553, 83–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García, S.; Fernández, A.; Luengo, J.; Herrera, F. Advanced nonparametric tests for multiple comparisons in the design of experiments in computational intelligence and data mining: Experimental analysis of power. Inf. Sci. 2010, 180, 2044–2064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taheri, S.M.; Hesamian, G. A generalization of the Wilcoxon signed-rank test and its applications. Stat. Pap. 2012, 54, 457–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, D.G.; Afonso, A.; Medeiros, F.M. Overview of Friedman’s Test and Post-hoc Analysis. Commun. Stat.-Simul. Comput. 2015, 44, 2636–2653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Method | Training Time Complexity | Testing Time Complexity | Peak Space Complexity |

|---|---|---|---|

| DPOA-MRM (ours) | |||

| GBDT | |||

| RF | |||

| BRAF | |||

| DPHS-MDS | |||

| SWSEL | |||

| MDSampler |

| Level | Method | Basis | Publication and Year |

|---|---|---|---|

| Algorithm | iForest [7] | One-class learning | ICDM 2008 |

| SVDD [6] | Applied Energy 2013 | ||

| GDBT [30] | Ensemble learning | Annals of statistics 2001 | |

| RF [29] | Journal of Chemical Information and Computer Sciences 2003 | ||

| BRAF [49] | IEEE Transactions on Neural Networks and Learning Systems 2018 | ||

| DPHS-MDS [40] | Expert Systems with Applications 2020 | ||

| SWSEL [50] | Engineering Applications of Artificial Intelligence 2023 | ||

| MDSampler [34] | Pattern Recognition 2025 | ||

| PCGDST-IE [36] | Cost-sensitive learning | Information Sciences 2023 | |

| HDAWCR [37] | Applied Intelligence 2024 | ||

| AWLICSR [38] | Expert Systems with Applications 2024 | ||

| Data | SMOTE [9] | Sampling | Journal of Artificial Intelligence Research 2002 |

| Borderline-SMOTE [51] | ICIC 2005 | ||

| G-SMOTE [52] | ICPR 2014 | ||

| SMOTE-NaN-DE [17] | Knowledge-Based Systems 2021 | ||

| MPP-SMOTE [18] | Information Sciences 2023 | ||

| TSSE-BIM [53] | Information Sciences 2024 | ||

| HSCF [19] | Information Sciences 2025 | ||

| CTGAN [54] | Generating | NIPS 2019 | |

| CWGAN-GP [22] | Information Sciences 2020 | ||

| ADA-INCVAE [24] | Applied Intelligence 2022 | ||

| RVGAN-TL [26] | Information Sciences 2023 | ||

| CDC-Glow [55] | Information Sciences 2023 | ||

| ConvGeN [56] | Pattern Recognition 2024 | ||

| SSG [57] | Neural Networks 2024 |

| Dataset | Instances | Features | Minority Instances | Majority Instances | IR | Overlap Degree |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ecoli-0vs1 | 220 | 8 | 77 | 143 | 1.86 | 0.0367 |

| wisconsin | 683 | 10 | 239 | 444 | 1.86 | 0.0405 |

| pima | 768 | 9 | 268 | 500 | 1.87 | 0.5625 |

| vehicle_2 | 846 | 19 | 218 | 628 | 2.88 | 0.6811 |

| vehicle_1 | 846 | 19 | 217 | 629 | 2.9 | 0.8221 |

| vehicle_3 | 846 | 19 | 212 | 634 | 2.99 | 0.8284 |

| vehicle_0 | 846 | 19 | 199 | 647 | 3.25 | 0.5682 |

| ecoli_1 | 336 | 8 | 77 | 259 | 3.36 | 0.3566 |

| newthyroid1 | 215 | 6 | 35 | 180 | 5.14 | 0.0819 |

| newthyroid2 | 215 | 6 | 35 | 180 | 5.14 | 0.0727 |

| ecoli2 | 336 | 8 | 52 | 284 | 5.46 | 0.3416 |

| segment0 | 2308 | 20 | 329 | 1979 | 6.02 | 0.4925 |

| yeast3 | 1484 | 9 | 163 | 1321 | 8.1 | 0.3092 |

| ecoli3 | 336 | 8 | 35 | 301 | 8.6 | 0.4916 |

| page-blocks0 | 5472 | 11 | 559 | 4913 | 8.79 | 0.0640 |

| yeast-2_vs_4 | 514 | 9 | 51 | 463 | 9.08 | 0.2896 |

| ecoli-0-6-7_vs_3-5 | 222 | 8 | 22 | 200 | 9.09 | 0.0527 |

| yeast-0-2-5-6_vs_3-7-8-9 | 1004 | 9 | 99 | 905 | 9.14 | 0.3108 |

| yeast-0-2-5-7-9_vs_3-6-8 | 1004 | 9 | 99 | 905 | 9.14 | 0.3058 |

| glass-0-4_vs_5 | 92 | 10 | 9 | 83 | 9.22 | 0.2508 |

| ecoli-0-1-4-7_vs_5-6 | 332 | 7 | 25 | 307 | 12.28 | 0.2341 |

| glass4 | 214 | 10 | 13 | 201 | 15.46 | 0.2434 |

| ecoli4 | 336 | 8 | 20 | 316 | 15.8 | 0.2631 |

| page-blocks-1-3_vs_4 | 472 | 11 | 28 | 444 | 15.86 | 0.0731 |

| abalone9-18 | 731 | 9 | 42 | 689 | 16.4 | 0.4568 |

| MEU-Mobile KSD | 1071 | 72 | 51 | 1020 | 20 | 0.2848 |

| yeast-2_vs_8 | 482 | 9 | 20 | 462 | 23.1 | 0.0000 |

| flare-F | 1066 | 12 | 43 | 1023 | 23.79 | 0.4131 |

| kr-vs-k-zero-one_vs_draw | 2901 | 7 | 105 | 2796 | 26.63 | 0.2681 |

| kr-vs-k-one_vs_fifteen | 2244 | 7 | 78 | 2166 | 27.77 | 0.0000 |

| winequality-red-4 | 1599 | 12 | 53 | 1546 | 29.17 | 0.6376 |

| yeast-1-2-8-9_vs_7 | 947 | 9 | 30 | 917 | 30.57 | 0.6547 |

| abalone-3_vs_11 | 502 | 9 | 15 | 487 | 32.47 | 0.4092 |

| kr-vs-k-three_vs_eleven | 2935 | 7 | 81 | 2854 | 35.23 | 0.5400 |

| ecoli-0-1-3-7_vs_2-6 | 281 | 8 | 7 | 274 | 39.14 | 0.0499 |

| abalone-17_vs_7-8-9-10 | 2338 | 9 | 58 | 2280 | 39.31 | 0.0747 |

| yeast6 | 1484 | 9 | 35 | 1449 | 41.4 | 0.3550 |

| poker-8-9vs6 | 1485 | 11 | 25 | 1460 | 58.4 | 0.9367 |

| poker-8vs6 | 1477 | 11 | 17 | 1460 | 85.88 | 0.9297 |

| Dataset | iForest | SVDD | GBDT | RF | BRAF | DPHS-MDS | SWSEL | PCGDST-IE | HDAWCR | AWLICSR | MDSampler | DPOA-MRM |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ecoli-0vs1 | 0.3593 | 0.6575 | 0.9810 | 0.9871 | 0.9871 | 0.9819 | 0.9862 | 0.9543 | 0.0000 | 0.2857 | 0.9604 | 0.9802 |

| wisconsin | 0.9420 | 0.7430 | 0.9544 | 0.9609 | 0.9579 | 0.9597 | 0.9373 | 0.9539 | 0.1666 | 0.0663 | 0.9608 | 0.9617 |

| pima | 0.3544 | 0.5746 | 0.6496 | 0.6375 | 0.6382 | 0.6657 | 0.6715 | 0.6182 | 0.6376 | 0.6666 | 0.6573 | 0.6786 |

| vehicle_2 | 0.2042 | 0.1624 | 0.9580 | 0.9700 | 0.9724 | 0.9710 | 0.8543 | 0.7654 | 0.4477 | 0.5294 | 0.9704 | 0.9752 |

| vehicle_1 | 0.1201 | 0.3049 | 0.5464 | 0.5203 | 0.5498 | 0.6095 | 0.5648 | 0.5707 | 0.9620 | 0.9620 | 0.6479 | 0.6532 |

| vehicle_3 | 0.1032 | 0.4451 | 0.5194 | 0.4964 | 0.5112 | 0.5688 | 0.5434 | 0.5434 | 0.9555 | 0.9662 | 0.6661 | 0.6099 |

| vehicle_0 | 0.2208 | 0.3218 | 0.9244 | 0.9355 | 0.9430 | 0.9408 | 0.8168 | 0.8044 | 0.2500 | 0.2500 | 0.9295 | 0.9520 |

| ecoli_1 | 0.1933 | 0.4944 | 0.7681 | 0.7888 | 0.7871 | 0.7666 | 0.7858 | 0.7472 | 0.8484 | 0.9696 | 0.7868 | 0.8321 |

| new-thyroid1 | 0.4584 | 0.5024 | 0.8872 | 0.9560 | 0.9516 | 0.9276 | 0.9133 | 0.9026 | 0.0698 | 0.0698 | 0.9713 | 0.9647 |

| new-thyroid2 | 0.4366 | 0.4731 | 0.9226 | 0.9513 | 0.9667 | 0.9419 | 0.9514 | 0.9086 | 0.9333 | 0.9333 | 0.9579 | 1.0000 |

| ecoli2 | 0.0422 | 0.2676 | 0.8143 | 0.7994 | 0.8258 | 0.8200 | 0.6741 | 0.6404 | 0.7333 | 0.7857 | 0.8032 | 0.8816 |

| segment0 | 0.0064 | 0.0411 | 0.9803 | 0.9923 | 0.9818 | 0.9884 | 0.9776 | 0.9023 | 0.0267 | 0.0267 | 0.9804 | 0.9909 |

| yeast3 | 0.0318 | 0.1746 | 0.7519 | 0.7460 | 0.7711 | 0.7860 | 0.6877 | 0.7509 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.7566 | 0.7948 |

| ecoli3 | 0.1402 | 0.3009 | 0.6337 | 0.5772 | 0.5739 | 0.5797 | 0.6154 | 0.5483 | 0.4705 | 0.7999 | 0.5972 | 0.7029 |

| page-blocks0 | 0.4222 | 0.3974 | 0.8721 | 0.8801 | 0.8869 | 0.8775 | 0.6956 | 0.5859 | 0.1188 | 0.1188 | 0.8826 | 0.8533 |

| yeast-2_vs_4 | 0.3465 | 0.4206 | 0.7015 | 0.7599 | 0.7555 | 0.7359 | 0.7387 | 0.6507 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.7955 | 0.8225 |

| ecoli-0-6-7_vs_3-5 | 0.3375 | 0.2823 | 0.7457 | 0.8071 | 0.7448 | 0.7579 | 0.6915 | 0.7074 | 0.3703 | 0.5263 | 0.6601 | 0.7802 |

| yeast-0-2-5-6_vs_3-7-8-9 | 0.2988 | 0.3903 | 0.5982 | 0.6262 | 0.6369 | 0.6459 | 0.3506 | 0.5089 | 0.5189 | 0.5189 | 0.5558 | 0.6735 |

| yeast-0-2-5-7-9_vs_3-6-8 | 0.2853 | 0.4643 | 0.7746 | 0.7952 | 0.7842 | 0.7946 | 0.6334 | 0.7425 | 0.3673 | 0.3749 | 0.8060 | 0.8231 |

| glass-0-4_vs_5 | 0.2905 | 0.1746 | 0.9333 | 0.9333 | 0.9600 | 0.9600 | 0.8667 | 0.6131 | 0.0807 | 0.0807 | 0.9333 | 1.0000 |

| ecoli-0-1-4-7_vs_5-6 | 0.3199 | 0.1923 | 0.8033 | 0.7833 | 0.8154 | 0.7898 | 0.5153 | 0.5856 | 0.1818 | 0.9999 | 0.7022 | 0.8039 |

| glass4 | 0.2324 | 0.2030 | 0.5133 | 0.6200 | 0.6978 | 0.6895 | 0.6343 | 0.5695 | 0.9999 | 0.0000 | 0.6267 | 0.8305 |

| ecoli4 | 0.1992 | 0.2092 | 0.7862 | 0.7562 | 0.7563 | 0.7543 | 0.7889 | 0.5909 | 0.0000 | 0.5454 | 0.7187 | 0.8292 |

| page-blocks-1-3_vs_4 | 0.4110 | 0.1346 | 0.9818 | 0.9418 | 0.9787 | 0.9447 | 0.6890 | 0.5870 | 0.7692 | 0.9333 | 0.9818 | 0.9846 |

| abalone9-18 | 0.1800 | 0.1077 | 0.3193 | 0.1572 | 0.3326 | 0.2889 | 0.1354 | 0.2903 | 0.4000 | 0.7999 | 0.2492 | 0.4340 |

| MEU-Mobile KSD | 0.0250 | 0.2611 | 0.7942 | 0.8627 | 0.9332 | 0.8924 | 0.5086 | 0.8609 | 0.0917 | 0.0893 | 0.9065 | 0.9204 |

| yeast-2_vs_8 | 0.5595 | 0.1208 | 0.5276 | 0.5467 | 0.5771 | 0.5838 | 0.2644 | 0.2289 | 0.2857 | 0.6249 | 0.2317 | 0.7405 |

| flare-F | 0.1585 | 0.1216 | 0.1245 | 0.1168 | 0.0323 | 0.0323 | 0.1942 | 0.5848 | 0.5000 | 0.7272 | 0.1932 | 0.2503 |

| kr-vs-k-zero-one_vs_draw | 0.1118 | 0.0828 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.9110 | 0.9014 | 0.0000 | 0.9225 | 0.0562 | 0.0562 | 0.3741 | 0.0000 |

| kr-vs-k-one_vs_fifteen | 0.2329 | 0.1930 | 0.8148 | 0.8148 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | 0.8147 | 0.9931 | 0.4999 | 0.4999 | 0.8148 | 0.8167 |

| winequality-red-4 | 0.0664 | 0.0472 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0218 | 0.0238 | 0.1196 | 0.3060 | 0.4062 | 0.4637 | 0.1411 | 0.1783 |

| yeast-1-2-8-9_vs_7 | 0.0461 | 0.0722 | 0.3144 | 0.2300 | 0.2251 | 0.1808 | 0.1112 | 0.2221 | 0.5925 | 0.6799 | 0.1260 | 0.3248 |

| abalone-3_vs_11 | 0.1795 | 0.2367 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | 0.7714 | 0.8815 | 0.0500 | 0.0500 | 0.9314 | 0.9714 |

| kr-vs-k-three_vs_eleven | 0.0941 | 0.0800 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.9570 | 0.9652 | 0.0000 | 0.9460 | 0.0687 | 0.0687 | 0.1565 | 0.0000 |

| ecoli-0-1-3-7_vs_2-6 | 0.1593 | 0.0801 | 0.3467 | 0.4667 | 0.5793 | 0.7467 | 0.3733 | 0.2982 | 0.2000 | 0.2000 | 0.1921 | 0.5800 |

| abalone-17_vs_7-8-9-10 | 0.0921 | 0.0807 | 0.2105 | 0.0333 | 0.2463 | 0.2433 | 0.0664 | 0.4607 | 0.0893 | 0.0893 | 0.2777 | 0.3235 |

| yeast6 | 0.1303 | 0.1344 | 0.3435 | 0.4955 | 0.5097 | 0.4976 | 0.3221 | 0.4468 | 0.1994 | 0.1994 | 0.3142 | 0.6467 |

| poker-8-9vs6 | 0.0302 | 0.0316 | 0.0667 | 0.0667 | 0.3324 | 0.1248 | 0.0692 | 0.2751 | 0.1000 | 0.2353 | 0.0685 | 0.7336 |

| poker-8vs6 | 0.0189 | 0.0221 | 0.1000 | 0.0000 | 0.0080 | 0.0000 | 0.0237 | 0.3444 | 0.0423 | 0.0449 | 0.0355 | 0.7867 |

| Average | 0.2267 | 0.2565 | 0.6144 | 0.6157 | 0.6949 | 0.6907 | 0.5476 | 0.6362 | 0.3459 | 0.4164 | 0.6236 | 0.7201 |

| Average Friedman-rank | 10.1538 | 10.1026 | 6.2051 | 6.0385 | 4.1410 | 4.6026 | 7.1795 | 6.6667 | 8.0385 | 7.0641 | 5.2179 | 2.5897 |

| Dataset | iForest | SVDD | GBDT | RF | BRAF | DPHS-MDS | SWSEL | PCGDST-IE | HDAWCR | AWLICSR | MDSampler | DPOA-MRM |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ecoli-0vs1 | 0.4363 | 0.6116 | 0.9839 | 0.9873 | 0.9873 | 0.9844 | 0.9864 | 0.9656 | 0.0000 | 0.4416 | 0.9669 | 0.9833 |

| wisconsin | 0.9624 | 0.7689 | 0.9665 | 0.9719 | 0.9695 | 0.9719 | 0.9623 | 0.9666 | 0.3015 | 0.0000 | 0.9718 | 0.9774 |

| pima | 0.4761 | 0.6630 | 0.7236 | 0.7120 | 0.7140 | 0.7406 | 0.7448 | 0.6900 | 0.8514 | 0.7840 | 0.7339 | 0.7457 |

| vehicle_2 | 0.3645 | 0.3298 | 0.9658 | 0.9774 | 0.9818 | 0.9791 | 0.9335 | 0.8656 | 0.5650 | 0.6242 | 0.9806 | 0.9867 |

| vehicle_1 | 0.2717 | 0.4026 | 0.6560 | 0.6418 | 0.6655 | 0.7328 | 0.7177 | 0.7212 | 0.9709 | 0.9709 | 0.7803 | 0.7802 |

| vehicle_3 | 0.2544 | 0.5565 | 0.6349 | 0.6067 | 0.6274 | 0.6988 | 0.7030 | 0.6989 | 0.9767 | 0.9807 | 0.8012 | 0.7540 |

| vehicle_0 | 0.3825 | 0.4048 | 0.9498 | 0.9552 | 0.9670 | 0.9674 | 0.9225 | 0.9082 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.9618 | 0.9792 |

| ecoli_1 | 0.2827 | 0.6491 | 0.8392 | 0.8491 | 0.8646 | 0.8513 | 0.8638 | 0.8776 | 0.8857 | 0.9826 | 0.8758 | 0.9168 |

| new-thyroid1 | 0.6430 | 0.7710 | 0.9273 | 0.9677 | 0.9635 | 0.9393 | 0.9578 | 0.9631 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.9824 | 0.9915 |

| new-thyroid2 | 0.6307 | 0.7477 | 0.9366 | 0.9542 | 0.9720 | 0.9522 | 0.9887 | 0.9635 | 0.9860 | 0.9860 | 0.9796 | 1.0000 |

| ecoli2 | 0.1173 | 0.3622 | 0.8648 | 0.8352 | 0.8821 | 0.8557 | 0.8522 | 0.8673 | 0.8049 | 0.8211 | 0.9019 | 0.9370 |

| segment0 | 0.0324 | 0.1442 | 0.9877 | 0.9924 | 0.9931 | 0.9897 | 0.9911 | 0.9668 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.9903 | 0.9934 |

| yeast3 | 0.0936 | 0.4647 | 0.8443 | 0.8224 | 0.8520 | 0.8700 | 0.9131 | 0.9387 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.8769 | 0.9221 |

| ecoli3 | 0.3156 | 0.6295 | 0.7497 | 0.6812 | 0.6838 | 0.6901 | 0.8898 | 0.8678 | 0.5923 | 0.9194 | 0.8250 | 0.8667 |

| page-blocks0 | 0.6322 | 0.5874 | 0.9165 | 0.9250 | 0.9357 | 0.9420 | 0.9396 | 0.8473 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.9385 | 0.9401 |

| yeast-2_vs_4 | 0.5242 | 0.7919 | 0.8235 | 0.8315 | 0.8291 | 0.8054 | 0.9279 | 0.8816 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.9210 | 0.9169 |

| ecoli-0-6-7_vs_3-5 | 0.6418 | 0.6614 | 0.8184 | 0.8439 | 0.8030 | 0.8021 | 0.8360 | 0.8570 | 0.8519 | 0.9246 | 0.8415 | 0.8602 |

| yeast-0-2-5-6_vs_3-7-8-9 | 0.4877 | 0.7497 | 0.7036 | 0.7079 | 0.7203 | 0.7328 | 0.7469 | 0.7594 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.7989 | 0.7949 |

| yeast-0-2-5-7-9_vs_3-6-8 | 0.4738 | 0.8265 | 0.8553 | 0.8575 | 0.8618 | 0.8580 | 0.8980 | 0.9180 | 0.6327 | 0.6346 | 0.9031 | 0.8939 |

| glass-0-4_vs_5 | 0.4020 | 0.4307 | 0.9936 | 0.9936 | 0.9936 | 0.9936 | 0.9815 | 0.8462 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.9936 | 1.0000 |

| ecoli-0-1-4-7_vs_5-6 | 0.6959 | 0.5506 | 0.8610 | 0.8340 | 0.8604 | 0.8333 | 0.8600 | 0.9038 | 0.8202 | 1.0000 | 0.8916 | 0.9034 |

| glass4 | 0.5022 | 0.6954 | 0.5947 | 0.7195 | 0.7527 | 0.7639 | 0.9618 | 0.8790 | 1.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.9247 | 0.9796 |

| ecoli4 | 0.3974 | 0.6453 | 0.8565 | 0.7878 | 0.8350 | 0.7802 | 0.9296 | 0.9167 | 0.0000 | 0.6493 | 0.8975 | 0.9374 |

| page-blocks-1-3_vs_4 | 0.7501 | 0.5120 | 0.9989 | 0.9605 | 0.9823 | 0.9482 | 0.9702 | 0.9337 | 0.8333 | 0.9860 | 0.9989 | 0.9989 |

| abalone9-18 | 0.5761 | 0.3266 | 0.3884 | 0.2354 | 0.4214 | 0.3945 | 0.5108 | 0.7259 | 0.7954 | 0.8165 | 0.7254 | 0.6506 |

| MEU-Mobile KSD | 0.0625 | 0.7950 | 0.8210 | 0.8713 | 0.9361 | 0.8986 | 0.8975 | 0.9195 | 0.1715 | 0.0000 | 0.9449 | 0.9467 |

| yeast-2_vs_8 | 0.7859 | 0.5179 | 0.6230 | 0.6237 | 0.6491 | 0.6554 | 0.7639 | 0.6805 | 0.4241 | 0.6742 | 0.7624 | 0.8008 |

| flare-F | 0.7124 | 0.5430 | 0.2495 | 0.2311 | 0.0663 | 0.0663 | 0.7474 | 0.8070 | 0.9354 | 0.9763 | 0.6911 | 0.3976 |

| kr-vs-k-zero-one_vs_draw | 0.6248 | 0.3439 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.9410 | 0.9251 | 0.0000 | 0.9652 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.7888 | 0.0000 |

| kr-vs-k-one_vs_fifteen | 0.8096 | 0.8020 | 0.8303 | 0.8303 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | 0.8301 | 0.9974 | 0.5773 | 0.5773 | 0.8303 | 0.8311 |

| winequality-red-4 | 0.2992 | 0.3163 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0379 | 0.0436 | 0.6274 | 0.5913 | 0.5322 | 0.5855 | 0.6886 | 0.4730 |

| yeast-1-2-8-9_vs_7 | 0.1586 | 0.4267 | 0.4191 | 0.3117 | 0.3076 | 0.2709 | 0.6179 | 0.6571 | 0.8488 | 0.8882 | 0.6772 | 0.4755 |

| abalone-3_vs_11 | 0.8464 | 0.7289 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | 0.9907 | 0.9952 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.9623 | 0.9990 |

| kr-vs-k-three_vs_eleven | 0.6725 | 0.6114 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.9685 | 0.9706 | 0.0000 | 0.9831 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.7978 | 0.0000 |

| ecoli-0-1-3-7_vs_2-6 | 0.6652 | 0.6371 | 0.5333 | 0.4828 | 0.6662 | 0.8784 | 0.7191 | 0.8364 | 0.3333 | 0.3333 | 0.7211 | 0.7851 |

| abalone-17_vs_7-8-9-10 | 0.6139 | 0.4970 | 0.3592 | 0.0603 | 0.3856 | 0.3697 | 0.5719 | 0.6656 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.8320 | 0.5917 |

| yeast6 | 0.3976 | 0.6703 | 0.4804 | 0.5949 | 0.6369 | 0.6109 | 0.8563 | 0.8305 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.8198 | 0.8178 |

| poker-8-9vs6 | 0.2565 | 0.4777 | 0.0894 | 0.0894 | 0.3979 | 0.1647 | 0.6687 | 0.7162 | 0.2321 | 0.3732 | 0.7108 | 0.8098 |

| poker-8vs6 | 0.2485 | 0.4886 | 0.1155 | 0.0000 | 0.0100 | 0.0000 | 0.4327 | 0.7030 | 0.5539 | 0.5805 | 0.6139 | 0.8094 |

| Average | 0.4744 | 0.5677 | 0.6759 | 0.6602 | 0.7467 | 0.7418 | 0.7875 | 0.8481 | 0.4225 | 0.4490 | 0.8540 | 0.8063 |

| Average Friedman-rank | 9.4615 | 9.0256 | 7.6538 | 7.5128 | 5.8077 | 6.2051 | 5.1282 | 4.4359 | 8.4231 | 7.4744 | 3.7564 | 3.1154 |

| F1-Score | G-Mean | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VS | R+ | R− | p-Value | Assuming | R+ | R− | p-Value | Assuming |

| iForest | 773 | 7 | rejected | 693 | 87 | rejected | ||

| SVDD | 777 | 3 | rejected | 708 | 72 | rejected | ||

| GBDT | 758 | 22 | rejected | 776 | 4 | rejected | ||

| RF | 742 | 38 | rejected | 773.5 | 6.5 | rejected | ||

| BRAF | 621 | 159 | rejected | 670 | 110 | rejected | ||

| DPHS-MDS | 611 | 169 | rejected | 647 | 133 | rejected | ||

| SWSEL | 778 | 2 | rejected | 617 | 163 | rejected | ||

| PSGDST-IE | 615 | 165 | rejected | 469 | 311 | not rejected | ||

| HDAWCR | 686 | 94 | rejected | 695 | 85 | rejected | ||

| AWLICSR | 632 | 148 | rejected | 669 | 111 | rejected | ||

| MDSampler | 674 | 106 | rejected | 476 | 304 | not rejected | ||

| Dataset | SMOTE | Borderline-SMOTE | G-SMOTE | SMOTE-NaN-DE | MPP-SMOTE | TSSE-BIM | HSCF | CTGAN | CWGAN-GP | ADA-INCVAE | RVGAN-TL | CDC-Glow | ConvGeN | SSG | DPOA-MRM |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ecoli-0vs1 | 0.9746 | 0.9862 | 0.9862 | 0.9862 | 0.9746 | 0.9793 | 0.9798 | 0.9810 | 0.9802 | 0.6547 | 0.9677 | 0.7847 | 0.9677 | 0.9867 | 0.9802 |

| wisconsin | 0.9592 | 0.9550 | 0.9569 | 0.9443 | 0.9674 | 0.9505 | 0.9374 | 0.9634 | 0.9489 | 0.9923 | 0.9398 | 0.0495 | 0.9592 | 0.9605 | 0.9617 |

| pima | 0.6510 | 0.6558 | 0.6629 | 0.6231 | 0.6675 | 0.6255 | 0.6778 | 0.6546 | 0.6313 | 0.6959 | 0.5243 | 0.4743 | 0.6903 | 0.6329 | 0.6786 |

| vehicle_2 | 0.9750 | 0.9700 | 0.9704 | 0.9675 | 0.9640 | 0.9636 | 0.8743 | 0.9532 | 0.9645 | 0.6433 | 0.9756 | 0.6444 | 0.9451 | 0.9716 | 0.9752 |

| vehicle_1 | 0.5971 | 0.6105 | 0.6214 | 0.5843 | 0.6166 | 0.5879 | 0.6337 | 0.5771 | 0.5640 | 0.8020 | 0.5814 | 0.8787 | 0.6000 | 0.5054 | 0.6532 |

| vehicle_3 | 0.6329 | 0.5714 | 0.5838 | 0.5433 | 0.6050 | 0.5640 | 0.5935 | 0.5435 | 0.5661 | 0.5595 | 0.3714 | 0.5152 | 0.5750 | 0.5191 | 0.6099 |

| vehicle_0 | 0.9199 | 0.9175 | 0.9256 | 0.9114 | 0.9227 | 0.9158 | 0.7506 | 0.9346 | 0.9219 | 0.8376 | 0.9351 | 0.7197 | 0.8974 | 0.9375 | 0.9520 |

| ecoli_1 | 0.7888 | 0.7869 | 0.8109 | 0.8088 | 0.8005 | 0.7704 | 0.7604 | 0.8071 | 0.7321 | 0.8278 | 0.7778 | 0.7063 | 0.7429 | 0.7540 | 0.8321 |

| new-thyroid1 | 0.9713 | 0.9188 | 0.9035 | 0.9200 | 0.9559 | 0.8851 | 0.9427 | 0.9483 | 0.8533 | 0.8872 | 1.0000 | 0.9409 | 0.9231 | 0.9379 | 0.9647 |

| new-thyroid2 | 0.9713 | 0.9263 | 0.9533 | 0.9417 | 0.9309 | 0.9600 | 0.9150 | 0.9514 | 0.9379 | 0.9077 | 0.9333 | 0.9223 | 1.0000 | 0.9667 | 1.0000 |

| ecoli2 | 0.8590 | 0.8199 | 0.8049 | 0.8192 | 0.8104 | 0.7695 | 0.7404 | 0.8263 | 0.7802 | 0.9802 | 0.7500 | 0.2084 | 0.8571 | 0.8145 | 0.8816 |

| segment0 | 0.9924 | 0.9892 | 0.9924 | 0.9847 | 0.9850 | 0.9786 | 0.9709 | 0.9880 | 0.9892 | 0.9559 | 0.9844 | 0.9559 | 0.9924 | 0.9923 | 0.9909 |

| yeast3 | 0.7896 | 0.7556 | 0.7728 | 0.7955 | 0.7631 | 0.7505 | 0.7591 | 0.7497 | 0.7371 | 0.0000 | 0.7246 | 0.1596 | 0.6071 | 0.7463 | 0.7948 |

| ecoli3 | 0.6213 | 0.6701 | 0.6225 | 0.6416 | 0.6256 | 0.6336 | 0.6389 | 0.6265 | 0.5633 | 0.7164 | 0.5455 | 0.7295 | 0.8000 | 0.5353 | 0.7029 |

| page-blocks0 | 0.8632 | 0.8761 | 0.8888 | 0.8509 | 0.8292 | 0.8241 | 0.6670 | 0.8789 | 0.7977 | 0.8824 | 0.8724 | 0.7888 | 0.7843 | 0.8950 | 0.8533 |

| yeast-2_vs_4 | 0.7852 | 0.7736 | 0.7945 | 0.7781 | 0.7731 | 0.7109 | 0.6959 | 0.7695 | 0.7553 | 0.4736 | 0.8000 | 0.7030 | 0.7500 | 0.7619 | 0.8225 |

| ecoli-0-6-7_vs_3-5 | 0.7295 | 0.7576 | 0.7652 | 0.7470 | 0.6589 | 0.7470 | 0.6998 | 0.8253 | 0.7833 | 0.6667 | 0.7500 | 0.6667 | 0.9091 | 0.7225 | 0.7802 |

| yeast-0-2-5-6_vs_3-7-8-9 | 0.6172 | 0.5284 | 0.5865 | 0.5822 | 0.6001 | 0.5187 | 0.5581 | 0.6200 | 0.4689 | 0.9359 | 0.6400 | 0.9576 | 0.7222 | 0.6297 | 0.6735 |

| yeast-0-2-5-7-9_vs_3-6-8 | 0.8004 | 0.7676 | 0.7917 | 0.8297 | 0.7906 | 0.7874 | 0.7498 | 0.8001 | 0.6881 | 0.4886 | 0.8000 | 0.7086 | 0.8571 | 0.8325 | 0.8231 |

| glass-0-4_vs_5 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | 0.9600 | 0.9600 | 0.9333 | 0.7908 | 0.7079 | 0.6667 | 0.7346 | 1.0000 | 0.8000 | 1.0000 |

| ecoli-0-1-4-7_vs_5-6 | 0.7687 | 0.7611 | 0.7483 | 0.8343 | 0.7260 | 0.7311 | 0.7566 | 0.8099 | 0.7056 | 0.2558 | 0.6667 | 0.5449 | 0.8000 | 0.7944 | 0.8039 |

| glass4 | 0.8343 | 0.8648 | 0.7667 | 0.8933 | 0.6548 | 0.7267 | 0.6118 | 0.7614 | 0.7068 | 0.0983 | 0.5000 | 0.1746 | 0.8000 | 0.6200 | 0.8305 |

| ecoli4 | 0.7889 | 0.7514 | 0.7800 | 0.7578 | 0.8325 | 0.7525 | 0.7355 | 0.9206 | 0.7524 | 0.7595 | 0.4000 | 0.8040 | 0.8000 | 0.7651 | 0.8292 |

| page-blocks-1-3_vs_4 | 0.9818 | 0.9818 | 0.9636 | 0.9636 | 0.9532 | 0.9359 | 0.4943 | 0.9664 | 0.7226 | 0.9185 | 1.0000 | 0.7871 | 1.0000 | 0.9018 | 0.9846 |

| abalone9-18 | 0.2649 | 0.3130 | 0.3047 | 0.3342 | 0.3500 | 0.2800 | 0.2272 | 0.3269 | 0.3219 | 0.0935 | 0.0000 | 0.2695 | 0.0000 | 0.1200 | 0.4340 |

| MEU-Mobile KSD | 0.9226 | 0.8480 | 0.8861 | 0.9357 | 0.9050 | 0.8764 | 0.9123 | 0.9236 | 0.7667 | 0.7578 | 0.7778 | 0.8360 | 0.8889 | 0.8731 | 0.9204 |

| yeast-2_vs_8 | 0.5886 | 0.6324 | 0.6714 | 0.5202 | 0.6673 | 0.4360 | 0.6014 | 0.6610 | 0.6244 | 0.0000 | 0.3333 | 0.1769 | 0.4000 | 0.6324 | 0.7405 |

| flare-F | 0.2622 | 0.1291 | 0.1691 | 0.2089 | 0.1741 | 0.2386 | 0.1630 | 0.1312 | 0.1067 | 0.5948 | 0.1111 | 0.6431 | 0.0000 | 0.0933 | 0.2503 |

| kr-vs-k-zero-one_vs_draw | 0.2441 | 0.0000 | 0.2114 | 0.1520 | 0.3027 | 0.3393 | 0.2540 | 0.9612 | 0.6855 | 0.6314 | 0.9714 | 0.6500 | 0.0000 | 0.9610 | 0.0000 |

| kr-vs-k-one_vs_fifteen | 0.5808 | 0.8147 | 0.7183 | 0.2551 | 0.7225 | 0.8135 | 0.5231 | 1.0000 | 0.9242 | 0.0333 | 1.0000 | 0.2308 | 0.8966 | 1.0000 | 0.8167 |

| winequality-red-4 | 0.1606 | 0.0571 | 0.0711 | 0.1054 | 0.1937 | 0.1737 | 0.1744 | 0.1188 | 0.0697 | 0.2000 | 0.0000 | 0.5000 | 0.1429 | 0.0000 | 0.1783 |

| yeast-1-2-8-9_vs_7 | 0.1805 | 0.1916 | 0.2622 | 0.1238 | 0.1477 | 0.1891 | 0.3587 | 0.2578 | 0.2389 | 0.9768 | 0.0000 | 0.9733 | 0.2857 | 0.1714 | 0.3248 |

| abalone-3_vs_11 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | 0.9429 | 0.9600 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | 0.8929 | 0.0794 | 1.0000 | 0.3212 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | 0.9714 |

| kr-vs-k-three_vs_eleven | 0.1540 | 0.0000 | 0.1543 | 0.1543 | 0.1540 | 0.1568 | 0.3706 | 1.0000 | 0.8229 | 0.7600 | 1.0000 | 0.6711 | 0.0000 | 1.0000 | 0.0000 |

| ecoli-0-1-3-7_vs_2-6 | 0.4600 | 0.4667 | 0.4667 | 0.6667 | 0.4933 | 0.4356 | 0.6133 | 0.6933 | 0.6667 | 1.0000 | 0.4000 | 0.9600 | 0.6667 | 0.5333 | 0.5800 |

| abalone-17_vs_7-8-9-10 | 0.2766 | 0.3856 | 0.2635 | 0.3334 | 0.3354 | 0.3094 | 0.2112 | 0.2476 | 0.1197 | 0.8139 | 0.0000 | 0.8325 | 0.2500 | 0.2133 | 0.3235 |

| yeast6 | 0.4750 | 0.4437 | 0.5637 | 0.5107 | 0.4422 | 0.3994 | 0.3738 | 0.5866 | 0.4550 | 0.9583 | 0.0000 | 0.9507 | 0.4000 | 0.4396 | 0.6467 |

| poker-8-9vs6 | 0.6032 | 0.6230 | 0.4143 | 0.4889 | 0.8222 | 0.1973 | 0.7921 | 0.4444 | 0.5563 | 0.5925 | 0.3333 | 0.6725 | 0.5000 | 0.2833 | 0.7336 |

| poker-8vs6 | 0.4933 | 0.3800 | 0.2800 | 0.0800 | 0.5933 | 0.2189 | 0.3800 | 0.2400 | 0.5200 | 0.9559 | 0.4000 | 0.9579 | 0.4000 | 0.1600 | 0.7867 |

| Average | 0.6805 | 0.6636 | 0.6690 | 0.6558 | 0.6834 | 0.6424 | 0.6425 | 0.7278 | 0.6696 | 0.6435 | 0.6265 | 0.6463 | 0.6618 | 0.6786 | 0.7201 |

| Average Friedman-rank | 6.5769 | 7.9359 | 6.9615 | 7.6923 | 7.3077 | 9.9103 | 9.5897 | 6.2564 | 9.7692 | 8.6026 | 9.8077 | 9.4231 | 7.6026 | 8.3718 | 4.1923 |

| Dataset | SMOTE | Borderline-SMOTE | G-SMOTE | SMOTE-NaN-DE | MPP-SMOTE | TSSE-BIM | HSCF | CTGAN | CWGAN-GP | ADA-INCVAE | RVGAN-TL | CDC-Glow | ConvGeN | SSG | DPOA-MRM |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ecoli-0vs1 | 0.9800 | 0.9864 | 0.9864 | 0.9864 | 0.9803 | 0.9826 | 0.9831 | 0.9839 | 0.9835 | 0.7860 | 0.9682 | 0.9111 | 0.9682 | 0.9869 | 0.9833 |

| wisconsin | 0.9717 | 0.9682 | 0.9693 | 0.9605 | 0.9782 | 0.9641 | 0.9525 | 0.9758 | 0.9641 | 0.9924 | 0.9599 | 0.0000 | 0.9727 | 0.9708 | 0.9774 |

| pima | 0.7280 | 0.7319 | 0.7368 | 0.7042 | 0.7415 | 0.7060 | 0.7481 | 0.7311 | 0.7081 | 0.8433 | 0.6130 | 0.8552 | 0.7601 | 0.7073 | 0.7457 |

| vehicle_2 | 0.9837 | 0.9791 | 0.9822 | 0.9766 | 0.9812 | 0.9781 | 0.9451 | 0.9757 | 0.9857 | 0.7159 | 0.9839 | 0.7207 | 0.9728 | 0.9766 | 0.9867 |

| vehicle_1 | 0.7254 | 0.7363 | 0.7430 | 0.7087 | 0.7508 | 0.7193 | 0.7711 | 0.6957 | 0.6943 | 0.8705 | 0.7239 | 0.9413 | 0.7219 | 0.6303 | 0.7802 |

| vehicle_3 | 0.7548 | 0.7071 | 0.7130 | 0.6838 | 0.7377 | 0.7030 | 0.7413 | 0.6577 | 0.6914 | 0.6238 | 0.4843 | 0.6231 | 0.6899 | 0.6249 | 0.7540 |

| vehicle_0 | 0.9583 | 0.9579 | 0.9573 | 0.9439 | 0.9690 | 0.9488 | 0.8883 | 0.9669 | 0.9621 | 0.9185 | 0.9622 | 0.8824 | 0.9246 | 0.9594 | 0.9792 |

| ecoli_1 | 0.8748 | 0.8799 | 0.8883 | 0.8921 | 0.8912 | 0.8482 | 0.8869 | 0.8688 | 0.8035 | 0.8958 | 0.8619 | 0.8314 | 0.8478 | 0.8374 | 0.9168 |

| new-thyroid1 | 0.9824 | 0.9456 | 0.9310 | 0.9309 | 0.9675 | 0.9290 | 0.9649 | 0.9888 | 0.9208 | 0.9351 | 1.0000 | 0.9511 | 0.9258 | 0.9514 | 0.9915 |

| new-thyroid2 | 0.9824 | 0.9486 | 0.9662 | 0.9634 | 0.9619 | 0.9799 | 0.9578 | 0.9887 | 0.9514 | 0.9560 | 0.9354 | 0.9567 | 1.0000 | 0.9690 | 1.0000 |

| ecoli2 | 0.9061 | 0.8652 | 0.8698 | 0.8821 | 0.8900 | 0.8635 | 0.8910 | 0.8930 | 0.8597 | 0.9835 | 0.7746 | 0.0000 | 0.8966 | 0.8447 | 0.9370 |

| segment0 | 0.9949 | 0.9906 | 0.9949 | 0.9885 | 0.9962 | 0.9862 | 0.9924 | 0.9954 | 0.9906 | 0.9675 | 0.9909 | 0.9675 | 0.9924 | 0.9923 | 0.9934 |

| yeast3 | 0.8916 | 0.8692 | 0.8829 | 0.9035 | 0.8845 | 0.8656 | 0.8757 | 0.8411 | 0.8124 | 0.0000 | 0.8017 | 0.4124 | 0.7096 | 0.8265 | 0.9221 |

| ecoli3 | 0.7981 | 0.8320 | 0.7965 | 0.8182 | 0.8258 | 0.7862 | 0.8115 | 0.7685 | 0.6849 | 0.7895 | 0.6124 | 0.8029 | 0.9105 | 0.6503 | 0.8667 |

| page-blocks0 | 0.9473 | 0.9474 | 0.9522 | 0.9486 | 0.9455 | 0.9341 | 0.9329 | 0.9324 | 0.8859 | 0.9565 | 0.9316 | 0.9438 | 0.8964 | 0.9343 | 0.9401 |

| yeast-2_vs_4 | 0.8713 | 0.8640 | 0.8840 | 0.9097 | 0.9160 | 0.8424 | 0.9024 | 0.8704 | 0.8486 | 0.5926 | 0.8615 | 0.7943 | 0.8849 | 0.8269 | 0.9169 |

| ecoli-0-6-7_vs_3-5 | 0.8533 | 0.8287 | 0.8478 | 0.8453 | 0.8420 | 0.8411 | 0.8568 | 0.8915 | 0.8699 | 0.7396 | 0.7746 | 0.7926 | 0.9874 | 0.7975 | 0.8602 |

| yeast-0-2-5-6_vs_3-7-8-9 | 0.7577 | 0.6784 | 0.7294 | 0.7445 | 0.7828 | 0.7404 | 0.7904 | 0.7164 | 0.6039 | 0.9620 | 0.6860 | 0.9760 | 0.7995 | 0.7114 | 0.7949 |

| yeast-0-2-5-7-9_vs_3-6-8 | 0.8879 | 0.8428 | 0.8770 | 0.9057 | 0.9007 | 0.8758 | 0.8950 | 0.8823 | 0.7705 | 0.6156 | 0.8379 | 0.8016 | 0.9381 | 0.8815 | 0.8939 |

| glass-0-4_vs_5 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | 0.9940 | 0.9940 | 0.9936 | 0.9058 | 0.8384 | 0.9718 | 0.8876 | 1.0000 | 0.8000 | 1.0000 |

| ecoli-0-1-4-7_vs_5-6 | 0.8344 | 0.8129 | 0.8361 | 0.8873 | 0.8557 | 0.8353 | 0.8980 | 0.9064 | 0.8270 | 0.3600 | 0.7683 | 0.7627 | 0.8872 | 0.8411 | 0.9034 |

| glass4 | 0.9190 | 0.9022 | 0.8181 | 0.9245 | 0.8390 | 0.8878 | 0.9230 | 0.9401 | 0.8505 | 0.2027 | 0.5774 | 0.4328 | 0.8165 | 0.6838 | 0.9796 |

| ecoli4 | 0.8819 | 0.8124 | 0.8392 | 0.8376 | 0.8849 | 0.8830 | 0.9274 | 0.9448 | 0.8660 | 0.8446 | 0.5000 | 0.8936 | 0.9843 | 0.8258 | 0.9374 |

| page-blocks-1-3_vs_4 | 0.9826 | 0.9826 | 0.9651 | 0.9651 | 0.9966 | 0.9793 | 0.9323 | 0.9977 | 0.8793 | 0.9644 | 1.0000 | 0.9281 | 1.0000 | 0.9357 | 0.9989 |

| abalone9-18 | 0.5714 | 0.4921 | 0.5509 | 0.6368 | 0.5972 | 0.5883 | 0.6603 | 0.5080 | 0.4705 | 0.1998 | 0.0000 | 0.5020 | 0.0000 | 0.2076 | 0.6506 |

| MEU-Mobile KSD | 0.9263 | 0.8589 | 0.8930 | 0.9378 | 0.9352 | 0.9234 | 0.9161 | 0.9361 | 0.8984 | 0.8436 | 0.7977 | 0.8820 | 0.8944 | 0.8815 | 0.9467 |

| yeast-2_vs_8 | 0.7406 | 0.6967 | 0.7373 | 0.7290 | 0.7448 | 0.7115 | 0.6864 | 0.7191 | 0.7217 | 0.0000 | 0.4472 | 0.3745 | 0.5000 | 0.6967 | 0.8008 |

| flare-F | 0.5276 | 0.2725 | 0.3020 | 0.6142 | 0.4751 | 0.6918 | 0.7445 | 0.2578 | 0.2032 | 0.6885 | 0.3687 | 0.8384 | 0.0000 | 0.1600 | 0.3976 |

| kr-vs-k-zero-one_vs_draw | 0.7727 | 0.0000 | 0.7917 | 0.7344 | 0.7931 | 0.7844 | 0.8775 | 0.9706 | 0.7871 | 0.7537 | 0.9991 | 0.8090 | 0.0000 | 0.9705 | 0.0000 |

| kr-vs-k-one_vs_fifteen | 0.8460 | 0.8301 | 0.8256 | 0.8358 | 0.8456 | 0.8292 | 0.9639 | 1.0000 | 0.9958 | 0.0663 | 1.0000 | 0.5012 | 0.9014 | 1.0000 | 0.8311 |

| winequality-red-4 | 0.3343 | 0.0851 | 0.1446 | 0.3100 | 0.4273 | 0.6076 | 0.5722 | 0.3472 | 0.2418 | 0.2309 | 0.0000 | 0.5567 | 0.3005 | 0.0000 | 0.4730 |

| yeast-1-2-8-9_vs_7 | 0.3336 | 0.3253 | 0.3921 | 0.2744 | 0.3306 | 0.6036 | 0.5642 | 0.3375 | 0.3121 | 0.9829 | 0.0000 | 0.9874 | 0.4082 | 0.2449 | 0.4755 |

| abalone-3_vs_11 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | 0.9979 | 0.9633 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | 0.9959 | 0.1416 | 1.0000 | 0.5868 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | 0.9990 |

| kr-vs-k-three_vs_eleven | 0.8293 | 0.0000 | 0.8293 | 0.8293 | 0.8293 | 0.7995 | 0.9495 | 1.0000 | 0.9582 | 0.8280 | 1.0000 | 0.8269 | 0.0000 | 1.0000 | 0.0000 |

| ecoli-0-1-3-7_vs_2-6 | 0.5383 | 0.4828 | 0.4828 | 0.6828 | 0.5396 | 0.7258 | 0.7359 | 0.7396 | 0.7963 | 1.0000 | 0.5000 | 0.9633 | 0.7071 | 0.5414 | 0.7851 |

| abalone-17_vs_7-8-9-10 | 0.5931 | 0.6124 | 0.5072 | 0.6766 | 0.6522 | 0.7226 | 0.6618 | 0.4831 | 0.2923 | 0.8473 | 0.0000 | 0.8598 | 0.4074 | 0.3268 | 0.5917 |

| yeast6 | 0.7101 | 0.6467 | 0.7494 | 0.7644 | 0.7083 | 0.7901 | 0.8063 | 0.6904 | 0.5903 | 0.9686 | 0.0000 | 0.9650 | 0.5336 | 0.5578 | 0.8178 |

| poker-8-9vs6 | 0.6631 | 0.6762 | 0.4363 | 0.5367 | 0.8472 | 0.7167 | 0.8152 | 0.5367 | 0.5868 | 0.7866 | 0.4472 | 0.9281 | 0.5774 | 0.3338 | 0.8098 |

| poker-8vs6 | 0.5047 | 0.4155 | 0.3309 | 0.1000 | 0.6202 | 0.8411 | 0.4464 | 0.2633 | 0.5942 | 0.9675 | 0.5000 | 0.9796 | 0.5000 | 0.2000 | 0.8094 |

| Average | 0.8041 | 0.7298 | 0.7728 | 0.7942 | 0.8170 | 0.8301 | 0.8426 | 0.7999 | 0.7632 | 0.7092 | 0.6831 | 0.7597 | 0.7235 | 0.7253 | 0.8063 |

| Average Friedman-rank | 6.4872 | 9.2564 | 7.9359 | 7.5256 | 5.6795 | 8.3718 | 6.2179 | 6.7564 | 10.0513 | 9.2179 | 10.7308 | 9.1154 | 8.1667 | 10.2692 | 4.2179 |

| F1-Score | G-Mean | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VS | R+ | R− | p-Value | Assuming | R+ | R− | p-Value | Assuming |

| SMOTE | 637 | 143 | rejected | 642 | 138 | rejected | ||

| Borderline-SMOTE | 721 | 59 | rejected | 759.5 | 20.5 | rejected | ||

| G-SMOTE | 674 | 106 | rejected | 691 | 89 | rejected | ||

| SMOTE-NaN-DE | 615 | 165 | rejected | 621 | 159 | rejected | ||

| MPP-SMOTE | 654 | 126 | rejected | 586 | 194 | rejected | ||

| TSSE-BIM | 709 | 71 | rejected | 546 | 234 | rejected | ||

| HSCF | 660 | 120 | rejected | 504.5 | 275.5 | not rejected | ||

| CTGAN | 549 | 231 | rejected | 627 | 153 | not rejected | ||

| CWGAN-GP | 668 | 112 | rejected | 663 | 117 | rejected | ||

| ADA-INCVAE | 482 | 298 | not rejected | 508 | 272 | rejected | ||

| RVGAN-TL | 643 | 137 | rejected | 671 | 109 | rejected | ||

| CDC-Glow | 483 | 297 | not rejected | 450 | 330 | not rejected | ||

| ConvGeN | 626 | 154 | rejected | 674.5 | 105.5 | rejected | ||

| SSG | 641 | 139 | rejected | 674 | 106 | rejected | ||

| Dataset | iForest | SVDD | GBDT | RF | BRAF | DPHS-MDS | SWSEL | PCGDST-IE | HDAWCR | AWLICSR | MDSampler | DPOA-MRM |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| pima | 0.3544 | 0.5746 | 0.6496 | 0.6375 | 0.6382 | 0.6657 | 0.6715 | 0.6182 | 0.1000 | 0.2353 | 0.6573 | 0.6786 |

| vehicle_2 | 0.2042 | 0.1624 | 0.9580 | 0.9700 | 0.9724 | 0.9710 | 0.8543 | 0.7654 | 0.9555 | 0.9662 | 0.9704 | 0.9752 |

| vehicle_1 | 0.1201 | 0.3049 | 0.5464 | 0.5203 | 0.5498 | 0.6095 | 0.5648 | 0.5707 | 0.4477 | 0.5294 | 0.6479 | 0.6532 |

| vehicle_3 | 0.1032 | 0.4451 | 0.5194 | 0.4964 | 0.5112 | 0.5688 | 0.5434 | 0.5434 | 0.4062 | 0.4637 | 0.6661 | 0.6099 |

| vehicle_0 | 0.2208 | 0.3218 | 0.9244 | 0.9355 | 0.9430 | 0.9408 | 0.8168 | 0.8044 | 0.9620 | 0.9620 | 0.9295 | 0.9520 |

| segment0 | 0.0064 | 0.0411 | 0.9803 | 0.9923 | 0.9818 | 0.9884 | 0.9776 | 0.9023 | 0.2500 | 0.2500 | 0.9804 | 0.9909 |

| ecoli3 | 0.1402 | 0.3009 | 0.6337 | 0.5772 | 0.5739 | 0.5797 | 0.6154 | 0.5483 | 0.0000 | 0.5454 | 0.5972 | 0.7029 |

| abalone9-18 | 0.1800 | 0.1077 | 0.3193 | 0.1572 | 0.3326 | 0.2889 | 0.1354 | 0.2903 | 0.2000 | 0.2000 | 0.2492 | 0.4340 |

| flare-F | 0.1585 | 0.1216 | 0.1245 | 0.1168 | 0.0323 | 0.0323 | 0.1942 | 0.5848 | 0.0807 | 0.0807 | 0.1932 | 0.2503 |

| winequality-red-4 | 0.0664 | 0.0472 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0218 | 0.0238 | 0.1196 | 0.3060 | 0.1666 | 0.0663 | 0.1411 | 0.1783 |

| yeast-1-2-8-9_vs_7 | 0.0461 | 0.0722 | 0.3144 | 0.2300 | 0.2251 | 0.1808 | 0.1112 | 0.2221 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.1260 | 0.3248 |

| kr-vs-k-three_vs_eleven | 0.0941 | 0.0800 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.9570 | 0.9652 | 0.0000 | 0.9460 | 0.0562 | 0.0562 | 0.1565 | 0.0000 |

| abalone-17_vs_7-8-9-10 | 0.0921 | 0.0807 | 0.2105 | 0.0333 | 0.2463 | 0.2433 | 0.0664 | 0.4607 | 0.0500 | 0.0500 | 0.2777 | 0.3235 |

| poker-8-9vs6 | 0.0302 | 0.0316 | 0.0667 | 0.0667 | 0.3324 | 0.1248 | 0.0692 | 0.2751 | 0.0423 | 0.0449 | 0.0685 | 0.7336 |

| poker-8vs6 | 0.0189 | 0.0221 | 0.1000 | 0.0000 | 0.0080 | 0.0000 | 0.0237 | 0.3444 | 0.0267 | 0.0267 | 0.0355 | 0.7867 |

| Average | 0.1224 | 0.1809 | 0.4231 | 0.3822 | 0.4884 | 0.4789 | 0.3842 | 0.5455 | 0.2496 | 0.2984 | 0.4464 | 0.5729 |

| Average Friedman-rank | 9.5333 | 9.5333 | 6.0333 | 7.7333 | 5.4333 | 5.2000 | 6.5667 | 4.8000 | 8.6000 | 8.1333 | 4.3333 | 2.1000 |

| Dataset | iForest | SVDD | GBDT | RF | BRAF | DPHS-MDS | SWSEL | PCGDST-IE | HDAWCR | AWLICSR | MDSampler | DPOA-MRM |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| pima | 0.4761 | 0.6630 | 0.7236 | 0.7120 | 0.7140 | 0.7406 | 0.7448 | 0.6900 | 0.2321 | 0.3732 | 0.7339 | 0.7457 |

| vehicle_2 | 0.3645 | 0.3298 | 0.9658 | 0.9774 | 0.9818 | 0.9791 | 0.9335 | 0.8656 | 0.9767 | 0.9807 | 0.9806 | 0.9867 |

| vehicle_1 | 0.2717 | 0.4026 | 0.6560 | 0.6418 | 0.6655 | 0.7328 | 0.7177 | 0.7212 | 0.5650 | 0.6242 | 0.7803 | 0.7802 |

| vehicle_3 | 0.2544 | 0.5565 | 0.6349 | 0.6067 | 0.6274 | 0.6988 | 0.7030 | 0.6989 | 0.5322 | 0.5855 | 0.8012 | 0.7540 |

| vehicle_0 | 0.3825 | 0.4048 | 0.9498 | 0.9552 | 0.9670 | 0.9674 | 0.9225 | 0.9082 | 0.9709 | 0.9709 | 0.9618 | 0.9792 |

| segment0 | 0.0324 | 0.1442 | 0.9877 | 0.9924 | 0.9931 | 0.9897 | 0.9911 | 0.9668 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.9903 | 0.9934 |

| ecoli3 | 0.3156 | 0.6295 | 0.7497 | 0.6812 | 0.6838 | 0.6901 | 0.8898 | 0.8678 | 0.0000 | 0.6493 | 0.8250 | 0.8667 |

| abalone9-18 | 0.5761 | 0.3266 | 0.3884 | 0.2354 | 0.4214 | 0.3945 | 0.5108 | 0.7259 | 0.3333 | 0.3333 | 0.7254 | 0.6506 |

| flare-F | 0.7124 | 0.5430 | 0.2495 | 0.2311 | 0.0663 | 0.0663 | 0.7474 | 0.8070 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.6911 | 0.3976 |

| winequality-red-4 | 0.2992 | 0.3163 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0379 | 0.0436 | 0.6274 | 0.5913 | 0.3015 | 0.0000 | 0.6886 | 0.4730 |

| yeast-1-2-8-9_vs_7 | 0.1586 | 0.4267 | 0.4191 | 0.3117 | 0.3076 | 0.2709 | 0.6179 | 0.6571 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.6772 | 0.4755 |

| kr-vs-k-three_vs_eleven | 0.6725 | 0.6114 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.9685 | 0.9706 | 0.0000 | 0.9831 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.7978 | 0.0000 |

| abalone-17_vs_7-8-9-10 | 0.6139 | 0.4970 | 0.3592 | 0.0603 | 0.3856 | 0.3697 | 0.5719 | 0.6656 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.8320 | 0.5917 |

| poker-8-9vs6 | 0.2565 | 0.4777 | 0.0894 | 0.0894 | 0.3979 | 0.1647 | 0.6687 | 0.7162 | 0.5539 | 0.5805 | 0.7108 | 0.8098 |

| poker-8vs6 | 0.2485 | 0.4886 | 0.1155 | 0.0000 | 0.0100 | 0.0000 | 0.4327 | 0.7030 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.6139 | 0.8094 |

| Average | 0.3757 | 0.4545 | 0.4859 | 0.4330 | 0.5485 | 0.5386 | 0.6720 | 0.7712 | 0.2977 | 0.3398 | 0.7873 | 0.6876 |

| Average Friedman-rank | 8.3333 | 8.0667 | 7.6667 | 8.4333 | 6.2333 | 6.4000 | 4.5667 | 4.0000 | 9.4667 | 9.0000 | 2.9333 | 2.9000 |

| m | Average F1-Score | Average G-Mean |

|---|---|---|

| 10 | 0.7201 | 0.8063 |

| 20 | 0.7156 | 0.7996 |

| 30 | 0.708 | 0.797 |

| 40 | 0.7043 | 0.7883 |

| 50 | 0.6982 | 0.7743 |

| Average F1-Score | Average G-Mean | |

|---|---|---|

| Full Model | 0.7201 | 0.8063 |