Safety Engineering for Humanoid Robots in Everyday Life—Scoping Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

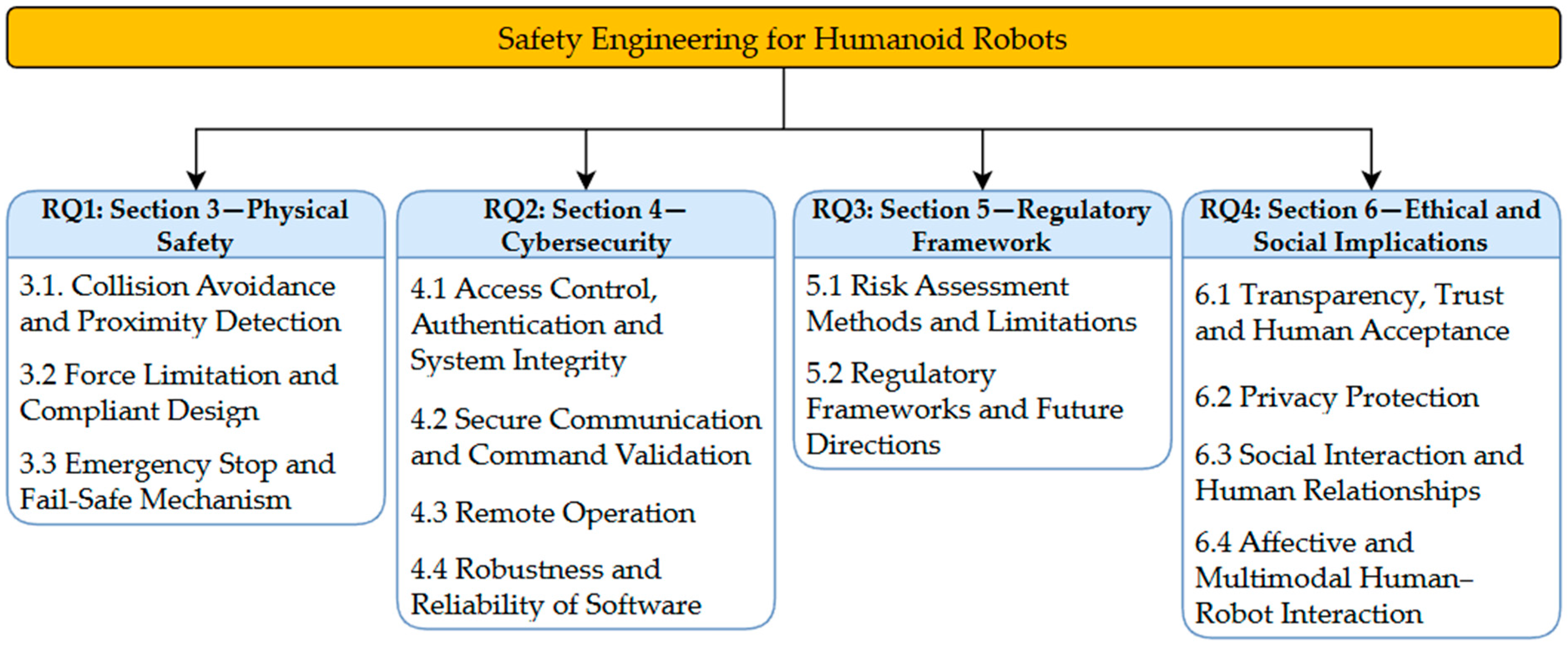

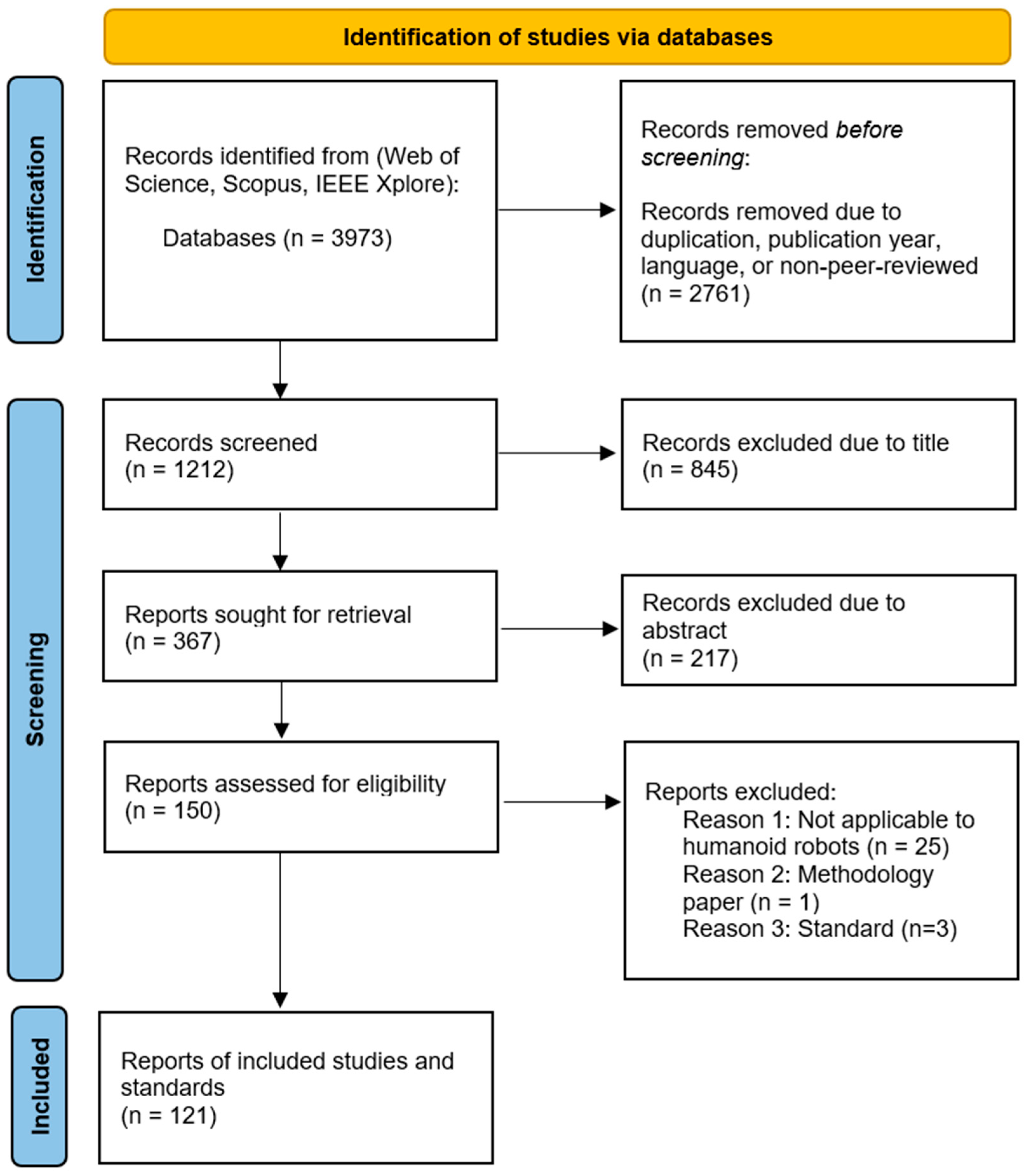

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Search Strategy

2.2. Study Selection Process and Eligibility Criteria

- RQ1: What hardware and control design are applied in human-shared environments?

- RQ2: How do studies address software/cybersecurity in shared environments?

- RQ3: How do the studies map or interpret the requirements of ISO 10218 series, ISO/TS 15066, and related standards?

- RQ4: How are social risks and user acceptance handled in human shared environments?

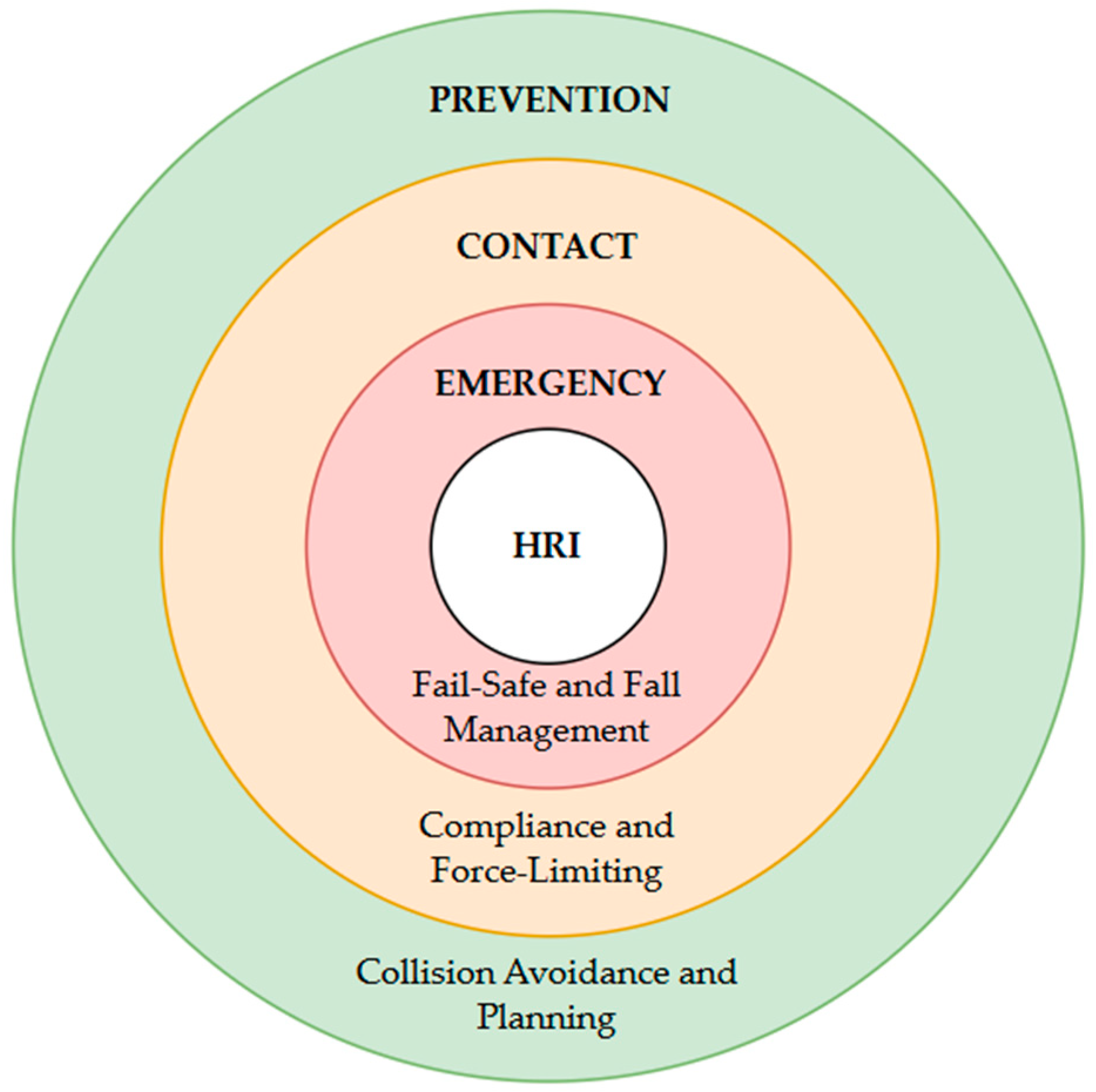

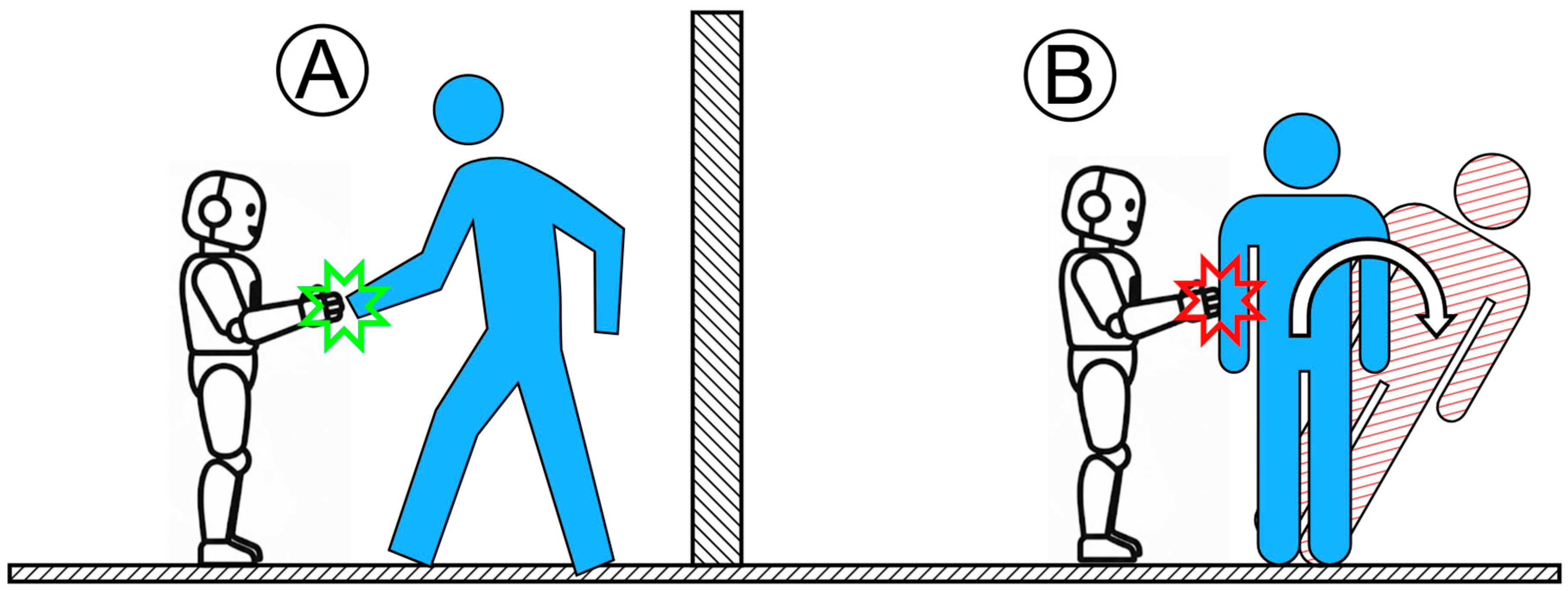

3. Physical Safety in Human–Robot Interaction

3.1. Collision Avoidance and Proximity Detection

3.2. Force Limitation and Compliant Design

3.3. Emergency Stop and Fail-Safe Mechanism

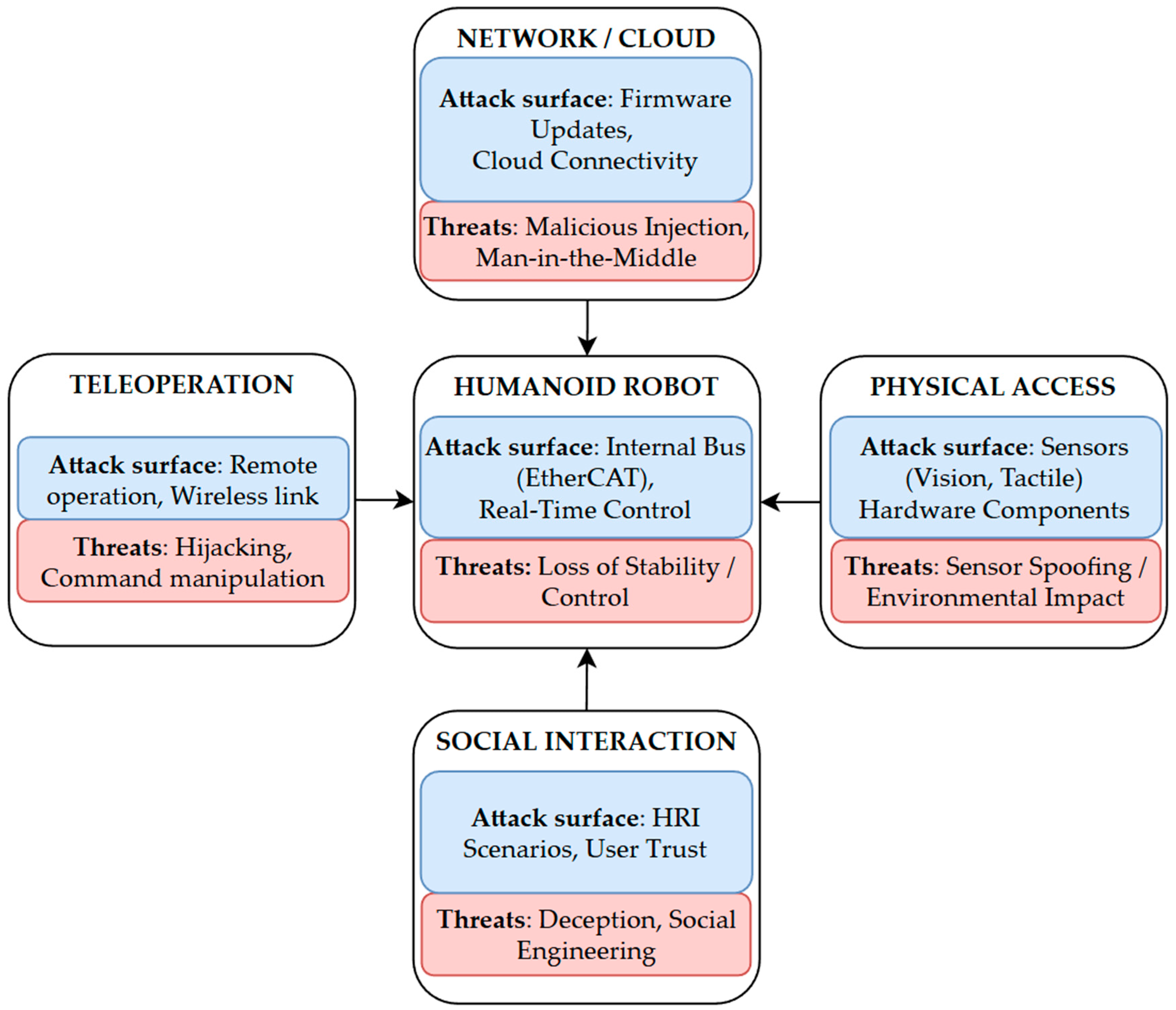

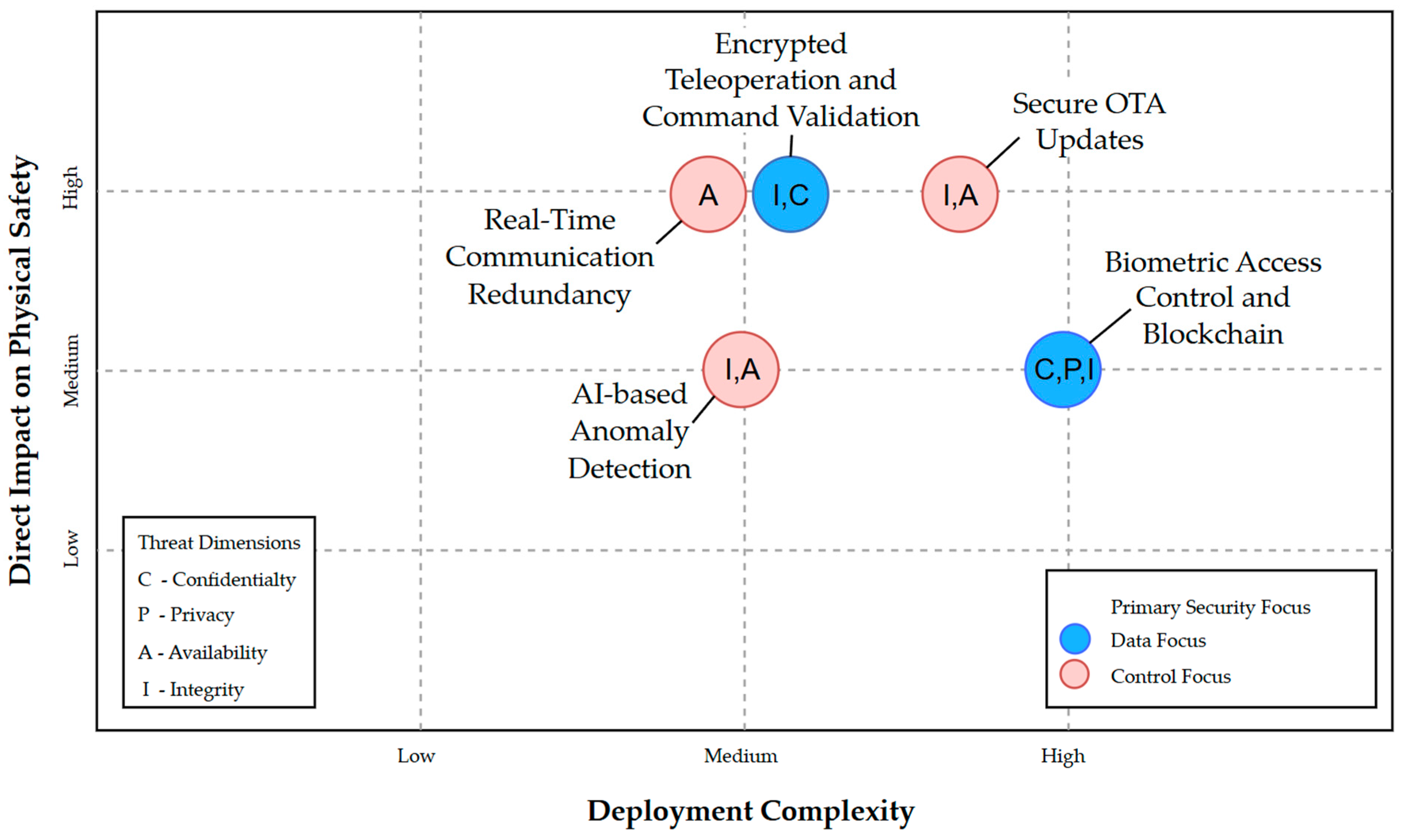

4. Cybersecurity and Software Robustness in HRI

4.1. Access Control, Authentication, and System Integrity

4.2. Secure Communication and Command Validation

4.3. Remote Operation

4.4. Robustness and Reliability of Software

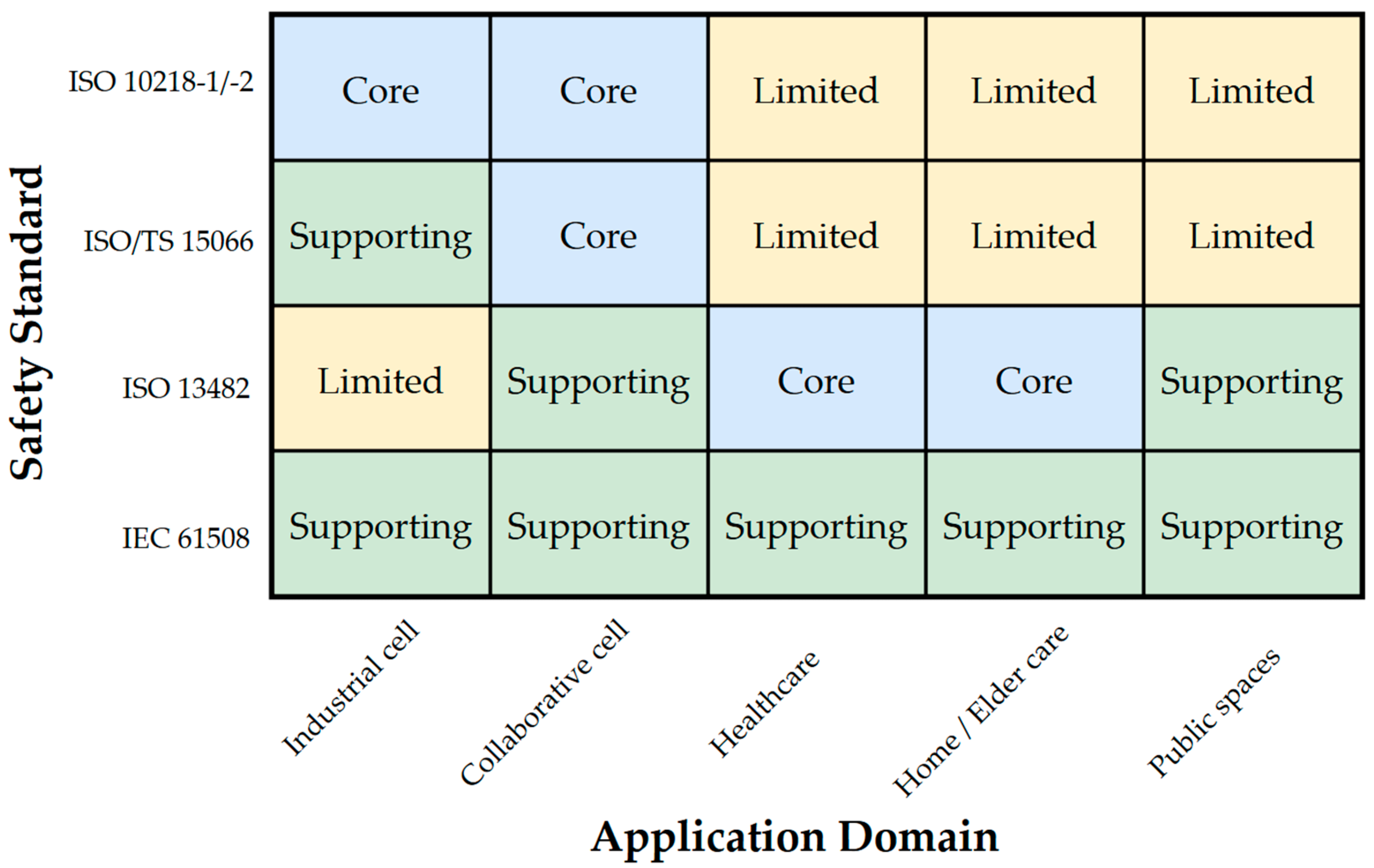

5. Safety Standards and Regulatory Framework

5.1. Risk Assessment Methods and Limitations

5.2. Regulatory Frameworks and Future Directions

6. Ethical and Social Implications

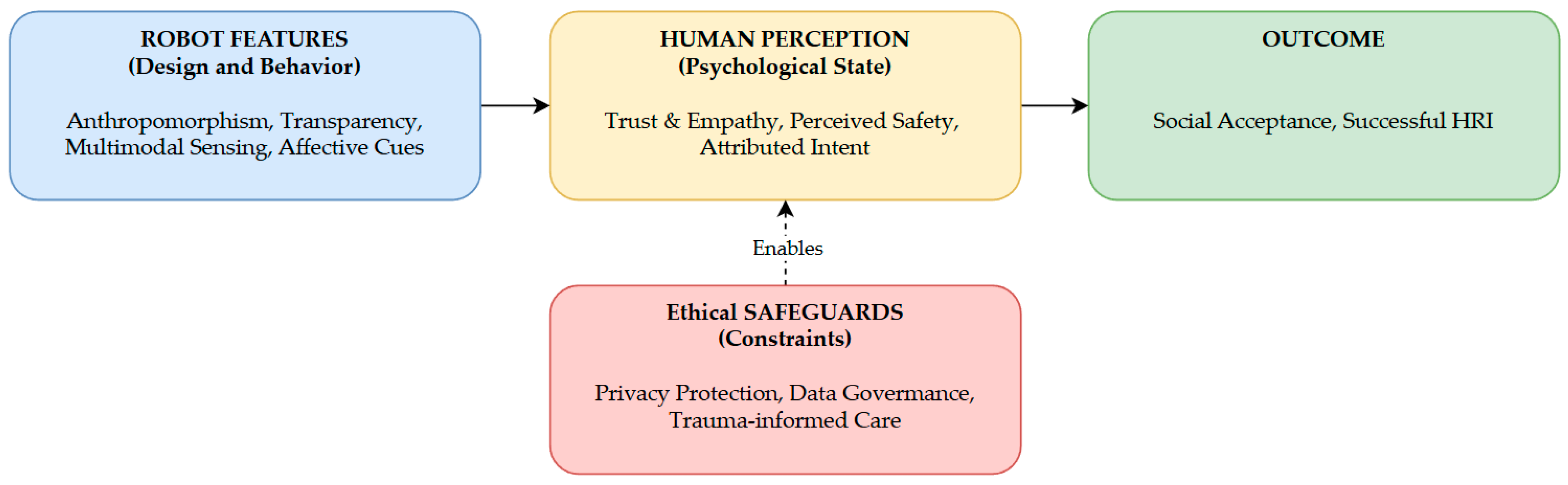

6.1. Transparency, Trust, and Human Acceptance

6.2. Privacy Protection

6.3. Social Interaction and Human Relationships

6.4. Affective and Multimodal Human–Robot Interaction

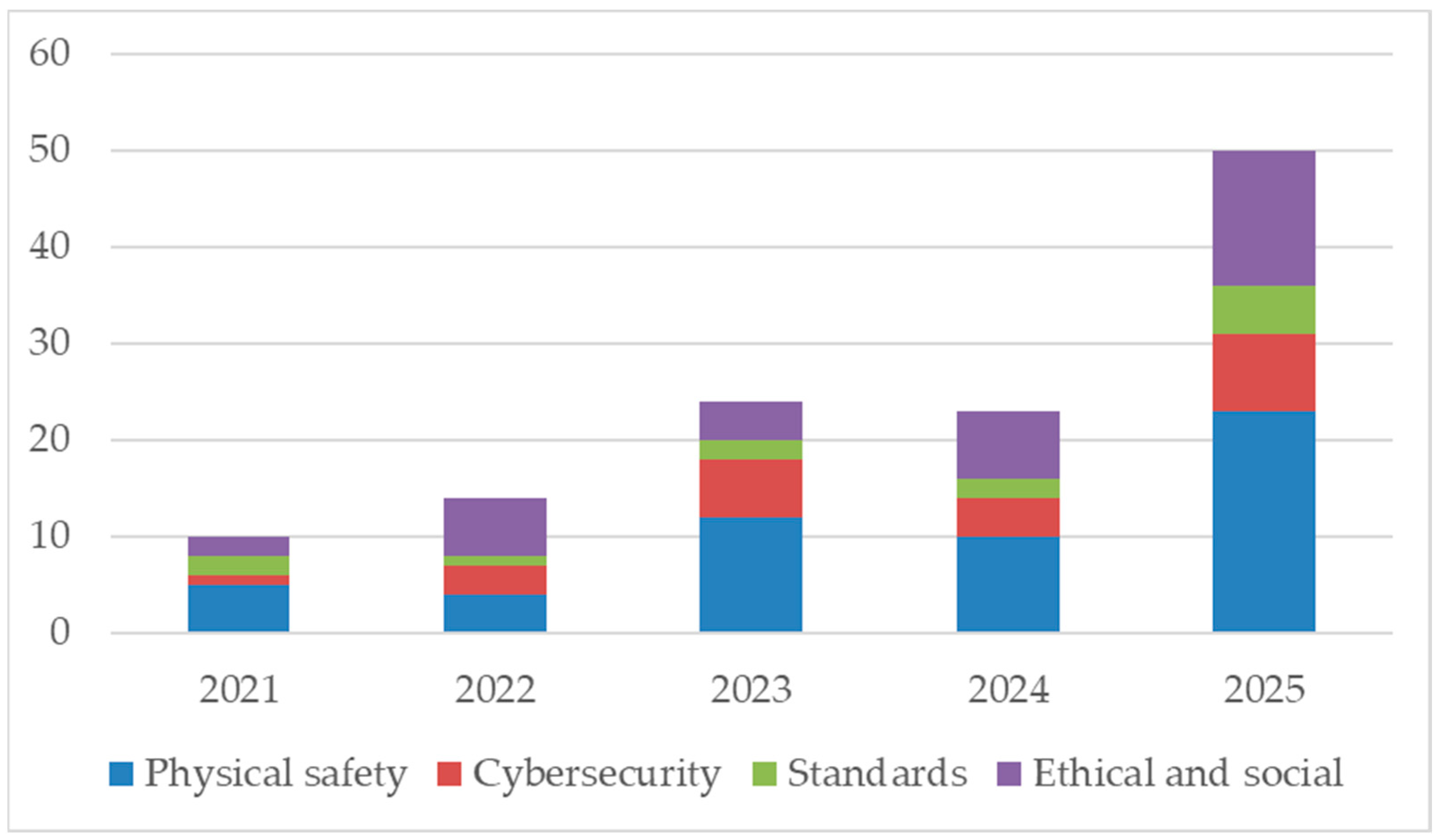

7. Discussion

7.1. Discussion and Summary of Evidence

7.2. Challenges and Restrictions

7.3. Conclusions and Recommendations

7.4. Limitations

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AI | Artificial intelligence |

| AMR | Autonomous Mobile Robot |

| ASD | Autism Spectrum Disorder |

| DOF | Degrees of freedom |

| DRL | Deep reinforcement learning |

| E/E/PE | Electrical, Electronic, and Programmable Electronic Safety-Related Systems |

| FTA | Fault Tree Analysis |

| HAZOP | Hazard and Operability Studies |

| HRC | Human–robot collaboration |

| HRI | Human–robot interaction |

| IoT | Internet of Things |

| MPC | Model predictive control |

| OTA | Over-the-air |

| PAM | Pneumatic artificial muscle |

| PFMEA | Process Failure Mode And Effects Analysis |

| PFL | Power and force limitation |

| pHRI | Physical human–robot interaction |

| PRISMA-ScR | Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses—Extension for Scoping Reviews |

| RQ | Research questions |

| SMUFR | Single-Motor Ultra-High-Flexibility |

| SRMS | Safety-rated monitored stop |

| SSM | Speed and separation monitoring |

References

- Scianca, N.; Ferrari, P.; De Simone, D.; Lanari, L.; Oriolo, G. A Behavior-Based Framework for Safe Deployment of Humanoid Robots. Auton. Robots 2021, 45, 435–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agrawal, A.K.; Kumar, J. Humanoid Left Arm Collaboration Empowered by IoT and Synchronization of Human Joints: IOT BASED JOINT SYNCHRONIZED COLLABORATIVE HUMANOID ARM. J. Sci. Ind. Res. JSIR 2024, 83, 819–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, J.; Park, S.; Sim, J.; Park, J. Dual-Channel EtherCAT Control System for 33-DOF Humanoid Robot TOCABI. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 44278–44286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodmann, P.R.; Saveriano, M.; Kritikakou, A.; Rech, P. Neutrons Sensitivity of Deep Reinforcement Learning Policies on EdgeAI Accelerators. IEEE Trans. Nucl. Sci. 2024, 71, 1480–1486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pohl, C.; Hegemann, P.; An, B.; Grotz, M.; Asfour, T. Humanoid robotic system for grasping and manipulation in decontamination tasks: Humanoides Robotersystem für das Greifen und Manipulieren bei Dekontaminierungsaufgaben. at-Automatisierungstechnik 2022, 70, 850–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shamsuddoha, M.; Nasir, T.; Fawaaz, M.S. Humanoid Robots like Tesla Optimus and the Future of Supply Chains: Enhancing Efficiency, Sustainability, and Workforce Dynamics. Automation 2025, 6, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruscelli, F.; Rossini, L.; Hoffman, E.M.; Baccelliere, L.; Laurenzi, A.; Muratore, L.; Antonucci, D.; Cordasco, S.; Tsagarakis, N.G. Design and Control of the Humanoid Robot COMAN+: Hardware Capabilities and Software Implementations. IEEE Robot. Autom. Mag. 2025, 32, 12–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavin, P.; Lesage, M.; Monroe, E.; Kanevsky, M.; Gruber, J.; Cinalioglu, K.; Rej, S.; Sekhon, H. Humanoid Robot Intervention vs. Treatment as Usual for Loneliness in Long-Term Care Homes: Study Protocol for a Pilot Randomized Controlled Trial. Front. Psychiatry 2022, 13, 1003881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lapresa, M.; Lauretti, C.; Cordella, F.; Reggimenti, A.; Zollo, L. Reproducing the Caress Gesture with an Anthropomorphic Robot: A Feasibility Study. Bioinspir. Biomim. 2024, 20, 016010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slane, A.; Pedersen, I. Bringing Older People’s Perspectives on Consumer Socially Assistive Robots into Debates about the Future of Privacy Protection and AI Governance. AI Soc. 2025, 40, 691–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, Y.-J.; Jao, Y.-L.; Boltz, M.; Adekeye, O.T.; Berish, D.; Yuan, F.; Zhao, X. Use of a Humanoid Robot in Supporting Dementia Care: A Qualitative Analysis. SAGE Open Nurs. 2023, 9, 23779608231179528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tobis, S.; Piasek-Skupna, J.; Neumann-Podczaska, A.; Religioni, U.; Suwalska, A. Determinants of Attitude to a Humanoid Social Robot in Care for Older Adults: A Post-Interaction Study. Med. Sci. Monit. 2023, 29, e941205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mazuz, K.; Yamazaki, R. Trauma-Informed Care Approach in Developing Companion Robots: A Preliminary Observational Study. Front. Robot. AI 2025, 12, 1476063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lippi, V.; Mergner, T. A Challenge: Support of Standing Balance in Assistive Robotic Devices. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 5240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Zhang, S.; Wang, A.; Li, W.; Song, L. Musculoskeletal Modeling and Humanoid Control of Robots Based on Human Gait Data. PeerJ Comput. Sci. 2021, 7, e657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aryania, A.; Aghdasi, H.S.; Heshmati, R.; Bonarini, A. Robust Risk-Averse Multi-Armed Bandits with Application in Social Engagement Behavior of Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder While Imitating a Humanoid Robot. Inf. Sci. 2021, 573, 194–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puglisi, A.; Caprì, T.; Pignolo, L.; Gismondo, S.; Chilà, P.; Minutoli, R.; Marino, F.; Failla, C.; Arnao, A.A.; Tartarisco, G.; et al. Social Humanoid Robots for Children with Autism Spectrum Disorders: A Review of Modalities, Indications, and Pitfalls. Children 2022, 9, 953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roštšinskaja, A.; Saard, M.; Korts, L.; Kööp, C.; Kits, K.; Loit, T.-L.; Juhkami, J.; Kolk, A. Unlocking the Potential of Social Robot Pepper: A Comprehensive Evaluation of Child-Robot Interaction. J. Pediatr. Health Care 2025, 39, 572–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodrich, M.A.; Schultz, A.C. Human-Robot Interaction: A Survey. Found. Trends Hum.-Comput. Interact. 2007, 1, 203–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheridan, T.B. Human–Robot Interaction: Status and Challenges. Hum. Factors 2016, 58, 525–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Jeelani, I.; Gheisari, M. Safe Human-Robot Collaboration in Construction: A Conceptual Perspective. J. Saf. Res. 2023, 86, 39–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, M.; Feng, Z.; Yang, X.; Liu, B. A Method for Human–Robot Complementary Collaborative Assembly Based on Knowledge Graph. CCF Trans. Pervasive Comput. Interact. 2025, 7, 70–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, H.; Wang, P.; Yang, Y.; Li, D.; Wei, W.; Luo, Y.; Deng, G. Reactive Human-to-Robot Dexterous Handovers for Anthropomorphic Hand. IEEE Trans. Robot. 2025, 41, 742–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arents, J.; Abolins, V.; Judvaitis, J.; Vismanis, O.; Oraby, A.; Ozols, K. Human–Robot Collaboration Trends and Safety Aspects: A Systematic Review. J. Sens. Actuator Netw. 2021, 10, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alenjareghi, M.J.; Keivanpour, S.; Chinniah, Y.A.; Jocelyn, S.; Oulmane, A. Safe Human-Robot Collaboration: A Systematic Review of Risk Assessment Methods with AI Integration and Standardization Considerations. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2024, 133, 4077–4110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmieri, J.; Di Lillo, P.; Lippi, M.; Chiaverini, S.; Marino, A. A Control Architecture for Safe Trajectory Generation in Human-Robot Collaborative Settings. IEEE Trans. Autom. Sci. Eng. 2025, 22, 365–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, K.; Chang, J.; Feng, S.; Fan, Y.; Wei, Z.; Hu, G. Safe Human Dual-Robot Interaction Based on Control Barrier Functions and Cooperation Functions. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 2024, 9, 9581–9588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farajtabar, M.; Charbonneau, M. The Path towards Contact-Based Physical Human–Robot Interaction. Robot. Auton. Syst. 2024, 182, 104829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandoval, E.B.; Sosa, R.; Cappuccio, M.; Bednarz, T. Human–Robot Creative Interactions: Exploring Creativity in Artificial Agents Using a Storytelling Game. Front. Robot. AI 2022, 9, 695162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rutili de Lima, C.; Khan, S.G.; Tufail, M.; Shah, S.H.; Maximo, M.R.O.A. Humanoid Robot Motion Planning Approaches: A Survey. J. Intell. Robot. Syst. 2024, 110, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vikas; Parhi, D.R. Chaos-Based Optimal Path Planning of Humanoid Robot Using Hybridized Regression-Gravity Search Algorithm in Static and Dynamic Terrains. Appl. Soft Comput. 2023, 140, 110236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kashyap, A.K.; Parhi, D.R.; Pandey, A. Multi-Objective Optimization Technique for Trajectory Planning of Multi-Humanoid Robots in Cluttered Terrain. ISA Trans. 2022, 125, 591–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Kim, Y.-C.; Lyu, Z.; Zhang, H. Research on Path Planning for Robot Based on Improved Design of Non-Standard Environment Map With Ant Colony Algorithm. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 99776–99791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Luca, A.; Muratore, L.; Tsagarakis, N.G. Autonomous Navigation with Online Replanning and Recovery Behaviors for Wheeled-Legged Robots Using Behavior Trees. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 2023, 8, 6803–6810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bin, T.; Yan, H.; Wang, N.; Nikolić, M.N.; Yao, J.; Zhang, T. A Survey on the Visual Perception of Humanoid Robot. Biomim. Intell. Robot. 2025, 5, 100197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subburaman, R.; Kanoulas, D.; Tsagarakis, N.; Lee, J. A Survey on Control of Humanoid Fall Over. Robot. Auton. Syst. 2023, 166, 104443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Gao, J.; Chen, Z.; Zhong, S.; Qiao, H. Fall Analysis and Prediction for Humanoids. Robot. Auton. Syst. 2025, 190, 104995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Z.; Yu, Z.; Chen, X.; Huang, Q.; Kheddar, A. Self-Protect Falling Trajectories for Humanoids with Resilient Trunk. Mechatronics 2023, 95, 103061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aller, F.; Pinto-Fernandez, D.; Torricelli, D.; Pons, J.L.; Mombaur, K. From the State of the Art of Assessment Metrics Toward Novel Concepts for Humanoid Robot Locomotion Benchmarking. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 2020, 5, 914–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.H.; Kim, J.S.; Yu, S. The Impact of Care Robots on Older Adults: A Systematic Review. Geriatr. Nur. 2025, 65, 103507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M.D.J.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L.; et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shamsah, A.; Gu, Z.; Warnke, J.; Hutchinson, S.; Zhao, Y. Integrated Task and Motion Planning for Safe Legged Navigation in Partially Observable Environments. IEEE Trans. Robot. 2023, 39, 4913–4934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Dai, H.; Mu, Y.; Wu, P.; Wang, H.; Chi, X.; Fei, Y.; Zhang, S.; Liu, C. DOZE: A Dataset for Open-Vocabulary Zero-Shot Object Navigation in Dynamic Environments. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 2024, 9, 7389–7396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.; Nahrendra, I.M.A.; Oh, M.; Yu, B.; Myung, H. TRG-Planner: Traversal Risk Graph-Based Path Planning in Unstructured Environments for Safe and Efficient Navigation. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 2025, 10, 1736–1743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Zeng, J.; Chen, S.; Sreenath, K. Autonomous Navigation of Underactuated Bipedal Robots in Height-Constrained Environments. Int. J. Robot. Res. 2023, 42, 565–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palleschi, A.; Hamad, M.; Abdolshah, S.; Garabini, M.; Haddadin, S.; Pallottino, L. Fast and Safe Trajectory Planning: Solving the Cobot Performance/Safety Trade-Off in Human-Robot Shared Environments. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 2021, 6, 5445–5452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dou, R.; Yu, S.; Li, W.; Chen, P.; Xia, P.; Zhai, F.; Yokoi, H.; Jiang, Y. Inverse Kinematics for a 7-DOF Humanoid Robotic Arm with Joint Limit and End Pose Coupling. Mech. Mach. Theory 2022, 169, 104637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, M.; Fan, Z.; Yu, X.; Wan, H.; Chen, Q.; Wang, P.; Fu, L. Division-Merge Based Inverse Kinematics for Multi-DOFs Humanoid Robots in Unstructured Environments. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2022, 198, 107090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, Y.; Zhai, D.-H.; Xia, Y. Robust Whole-Body Safety-Critical Control for Sampled-Data Robotic Manipulators via Control Barrier Functions. IEEE Trans. Autom. Sci. Eng. 2025, 22, 16050–16061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertoni, L.; Baccelliere, L.; Muratore, L.; Tsagarakis, N.G. A Proximity-Based Framework for Human-Robot Seamless Close Interactions. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 2025, 10, 8514–8521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Zheng, H.; Xu, L.; Chen, L.; Xia, F.; Song, Y. A Biomimetic Nanofluidic Tongue for Highly Selective and Sensitive Bitterness Perception. J. Mater. Chem. A 2025, 13, 31023–31033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, C.; Zhou, Y.; He, B.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, C.; Sang, H.; Liu, H. An Active Strategy for Safe Human–Robot Interaction Based on Visual–Tactile Perception. IEEE Syst. J. 2023, 17, 5555–5566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jassim, H.S.; Akhter, Y.; Aalwahab, D.Z.; Neamah, H.A. Recent Advances in Tactile Sensing Technologies for Human-Robot Interaction: Current Trends and Future Perspectives. Biosens. Bioelectron. X 2025, 26, 100669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, R.; Tao, J.; Zhao, J.; Dong, M.; Li, J.; Pan, C. Integrated Intelligent Tactile System for a Humanoid Robot. Sci. Bull. 2023, 68, 1027–1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, X.; Ying, Y.; Dong, W. CEASE: Collision-Evaluation-Based Active Sense System for Collaborative Robotic Arms. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2024, 73, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharkawy, A.-N.; Koustoumpardis, P.N. Human–Robot Interaction: A Review and Analysis on Variable Admittance Control, Safety, and Perspectives. Machines 2022, 10, 591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Qian, K.; Schuller, B.W.; Wollherr, D. An Online Robot Collision Detection and Identification Scheme by Supervised Learning and Bayesian Decision Theory. IEEE Trans. Autom. Sci. Eng. 2021, 18, 1144–1156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, C.Y.; Vergez, L.; Suleiman, W. Vision- and Tactile-Based Continuous Multimodal Intention and Attention Recognition for Safer Physical Human–Robot Interaction. IEEE Trans. Autom. Sci. Eng. 2024, 21, 3205–3215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Zhang, M.; Guo, J.; He, H. Barrier Offset Varying-Parameter Dynamic Learning Network for Solving Dual-Arms Human-Like Behavior Generation. IEEE Trans. Cogn. Dev. Syst. 2025, 17, 1199–1211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.; Zhang, M.; Liu, Y.; Lin, J.; Zhang, Z. Dynamic Neural Learning for Obstacle Avoidance of Humanoid Robot Performing Cooperative Tasks. Neurocomputing 2025, 633, 129727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, B.; Liang, D.; Huang, Q.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, P.; Wan, M.; Song, W.; Wang, B. Frame-By-Frame Motion Retargeting with Self-Collision Avoidance from Diverse Human Demonstrations. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 2024, 9, 8706–8713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, S.; Hofmann, A.; Williams, B. Fast-Reactive Probabilistic Motion Planning for High-Dimensional Robots. SN Comput. Sci. 2021, 2, 484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Wang, Y.; Guo, Y.; Duan, J. Vole Foraging-Inspired Dynamic Path Planning of Wheeled Humanoid Robots Under Workshop Slippery Road Conditions. Biomimetics 2025, 10, 277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dawood, M.; Pan, S.; Dengler, N.; Zhou, S.; Schoellig, A.P.; Bennewitz, M. Safe Multi-Agent Reinforcement Learning for Behavior-Based Cooperative Navigation. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 2025, 10, 6256–6263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özbaltan, M.; Özbaltan, N.; Bıçakcı Yeşilkaya, H.S.; Demir, M.; Şeker, C.; Yıldırım, M. Task Scheduling of Multiple Humanoid Robot Manipulators by Using Symbolic Control. Biomimetics 2025, 10, 346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Z.; Gao, F.; Chen, Z.; Yin, Y.; Yang, L.; Xi, Q.; Yang, E.; Luo, X. Force-Compliance MPC and Robot-User CBFs for Interactive Navigation and User-Robot Safety in Hexapod Guide Robots. IEEE Trans. Autom. Sci. Eng. 2025, 22, 20296–20310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salt Ducaju, J.; Olofsson, B.; Johansson, R. Model-Based Predictive Impedance Variation for Obstacle Avoidance in Safe Human–Robot Collaboration. IEEE Trans. Autom. Sci. Eng. 2025, 22, 9571–9583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Chen, X.; Yu, Z.; Yu, H.; Meng, L.; Yokoi, H. High-Precision Dynamic Torque Control of High Stiffness Actuator for Humanoids. ISA Trans. 2023, 141, 401–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jing, Z.; Luo, A.; Liu, X.; Wang, H.; Li, H.; Song, B.; Lu, S. Precision Actuation Method for Humanoid Eye Expression Robots Integrating Deep Reinforcement Learning. Sens. Actuators Phys. 2025, 393, 116762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, D.; Sun, N.; Wu, Y.; Liu, G.; Fang, Y. Fuzzy-Sliding Mode Control for Humanoid Arm Robots Actuated by Pneumatic Artificial Muscles with Unidirectional Inputs, Saturations, and Dead Zones. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inform. 2022, 18, 3011–3021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wang, G.; Ge, W.; Duan, J.; Chen, Z.; Wen, L. Perceived Safety Assessment of Interactive Motions in Human–Soft Robot Interaction. Biomimetics 2024, 9, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Zhao, Z. A Meniscus-Like Structure in Anthropomorphic Joints to Attenuate Impacts. IEEE Trans. Robot. 2024, 40, 3109–3126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Chen, X.; Yu, Z.; Han, L.; Gao, Z.; Zhao, Q.; Huang, G.; Li, K.; Huang, Q. HTEC Foot: A Novel Foot Structure for Humanoid Robots Combining Static Stability and Dynamic Adaptability. Def. Technol. 2025, 44, 30–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, H.; Song, C.; Ota, J. A Novel Cable-Driven 7-DOF Anthropomorphic Manipulator. IEEE ASME Trans. Mechatron. 2021, 26, 2174–2185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higashi, K.; Koyama, K.; Ficuciello, F.; Ozawa, R.; Kiyokawa, T.; Wan, W.; Harada, K. Synergy Hand Using Fluid Network: Realization of Various Grasping/Manipulation Styles. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 164966–164978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, Q.; Li, D.; Zhou, X.; Xin, W.; Wang, C.; Ambrose, J.W.; Yeow, R.C.-H. Single-Motor Ultraflexible Robotic (SMUFR) Humanoid Hand. IEEE Trans. Med. Robot. Bionics 2024, 6, 1666–1677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, Y.; Ye, Z.; Tan, X.; Dai, M.; Ge, S.; Zhao, X.; Kong, D.; Ruan, Y. Fruit Grasping Evaluation Based on a Humanoid Underactuated Manipulator and an Adaptive Grasping Algorithm. Smart Agric. Technol. 2025, 11, 101007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, S.; Shang, W.; Dai, S.; Deng, J.; Zhang, F.; Zhang, B.; Cong, S. Stiffness Optimization of Cable-Driven Humanoid Manipulators. IEEEASME Trans. Mechatron. 2024, 29, 4168–4178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, S.; Liu, H.; Wu, C.; Huang, L.; Chen, Y. Anti-Falling of Wheeled Humanoid Robots Based on a Novel Variable Stiffness Mechanism. Smart Mater. Struct. 2025, 34, 085002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrari, P.; Rossini, L.; Ruscelli, F.; Laurenzi, A.; Oriolo, G.; Tsagarakis, N.G.; Mingo Hoffman, E. Multi-Contact Planning and Control for Humanoid Robots: Design and Validation of a Complete Framework. Robot. Auton. Syst. 2023, 166, 104448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scianca, N.; Smaldone, F.M.; Lanari, L.; Oriolo, G. A Feasibility-Driven MPC Scheme for Robust Gait Generation in Humanoids. Robot. Auton. Syst. 2025, 189, 104957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, J.; Chen, X.; Yu, Z.; Chen, Z.; Dong, C.; Liu, X.; Huang, Q. Towards High Mobility and Adaptive Mode Transitions: Transformable Wheel-Biped Humanoid Locomotion Strategy. ISA Trans. 2025, 158, 184–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.; Sun, S.; Huang, H.; Gao, Q.; Xu, W. Design and Control of Continuous Jumping Gaits for Humanoid Robots Based on Motion Function and Reinforcement Learning. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2024, 250, 51–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, X.; Ye, Y.; Jiao, B.; Kong, Y.; Yu, L.; Liu, R.; Yun, S.; Lu, D.; Qiao, J.; Liu, Z.; et al. A Flexible Thermal Management Method for High-Power Chips in Humanoid Robots. Device 2025, 3, 100576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, S.G. Adaptive Chaos Control of a Humanoid Robot Arm: A Fault-Tolerant Scheme. Mech. Sci. 2023, 14, 209–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, S.G.; Bendoukha, S.; Abdelmalek, S. Chaos Stabilization and Tracking Recovery of a Faulty Humanoid Robot Arm in a Cooperative Scenario. Vibration 2019, 2, 87–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, J.; Lam, T.L.; Ge, L.; Pang, J.; Huang, Y. Safe and Adaptive 3-D Locomotion via Constrained Task-Space Imitation Learning. IEEE ASME Trans. Mechatron. 2023, 28, 3029–3040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oruma, S.O.; Sánchez-Gordón, M.; Colomo-Palacios, R.; Gkioulos, V.; Hansen, J.K. A Systematic Review on Social Robots in Public Spaces: Threat Landscape and Attack Surface. Computers 2022, 11, 181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajiabbasi, M.; Akhtarkavan, E.; Majidi, B. Cyber-Physical Customer Management for Internet of Robotic Things-Enabled Banking. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 34062–34079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biström, D.; Westerlund, M.; Duncan, B.; Jaatun, M.G. Privacy and Security Challenges for Autonomous Agents: A Study of Two Social Humanoid Service Robots. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE International Conference on Cloud Computing Technology and Science (CloudCom), Bangkok, Thailand, 13–16 December 2022; pp. 230–237. [Google Scholar]

- Ghandour, M.; Jleilaty, S.; Ait Oufroukh, N.; Olaru, S.; Alfayad, S. Real-Time EtherCAT-Based Control Architecture for Electro-Hydraulic Humanoid. Mathematics 2024, 12, 1405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, C.-Y.; Lee, S.-J.; Lee, I.-G. Secure and Lightweight Firmware Over-the-Air Update Mechanism for Internet of Things. Electronics 2025, 14, 1583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catuogno, L.; Galdi, C. Secure Firmware Update: Challenges and Solutions. Cryptography 2023, 7, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, A.R.; Kamal, H. Robust Fault Detection in Industrial Machines Using Hybrid Transformer-DNN With Visualization via a Humanoid-Based Telepresence Robot. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 115558–115580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baltes, J.; Christmann, G.; Saeedvand, S. A Deep Reinforcement Learning Algorithm to Control a Two-Wheeled Scooter with a Humanoid Robot. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2023, 126, 106941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, S.; Li, C.; Zhao, Z.; Huang, H.; Xu, W. Leveraging Large Language Models for Comprehensive Locomotion Control in Humanoid Robots Design. Biomim. Intell. Robot. 2024, 4, 100187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, M.; Cao, Y. Robust Human-Machine Teaming Through Reinforcement Learning from Failure via Sparse Reward Densification. IEEE Control Syst. Lett. 2025, 9, 2315–2320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sekkat, H.; Moutik, O.; El Kari, B.; Chaibi, Y.; Tchakoucht, T.A.; El Hilali Alaoui, A. Beyond Simulation: Unlocking the Frontiers of Humanoid Robot Capability and Intelligence with Pepper’s Open-Source Digital Twin. Heliyon 2024, 10, e34456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, X.; Guo, Z.; Jin, X.; Guo, H. Digital Twin-Enabled Safety Monitoring System for Seamless Worker-Robot Collaboration in Construction. Autom. Constr. 2025, 174, 106147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonnet, V.; Mirabel, J.; Daney, D.; Lamiraux, F.; Gautier, M.; Stasse, O. Practical Whole-Body Elasto-Geometric Calibration of a Humanoid Robot: Application to the TALOS Robot. Robot. Auton. Syst. 2023, 164, 104365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altan, D.; Sariel, S. CLUE-AI: A Convolutional Three-Stream Anomaly Identification Framework for Robot Manipulation. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 48347–48357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuo, Y.; Guo, B.H.W.; Goh, Y.M.; Lim, J.-Y. Identifying Human-Robot Interaction (HRI) Incident Archetypes: A System and Network Analysis of Accidents. Saf. Sci. 2025, 191, 106959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 10218-1:2025; Robotics—Safety Requirements Part 1: Industrial Robots. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2025.

- ISO 10218-2:2025; Robotics—Safety Requirements Part 2: Industrial Robot Applications and Robot Cells. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2025.

- Bhattathiri, S.S.; Bogovik, A.; Abdollahi, M.; Hochgraf, C.; Kuhl, M.E.; Ganguly, A.; Kwasinski, A.; Rashedi, E. Unlocking Human-Robot Synergy: The Power of Intent Communication in Warehouse Robotics. Appl. Ergon. 2024, 117, 104248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ISO/TS 15066:2016; Robots and Robotic Devices–Collaborative Robots. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2016.

- Jacobs, T.; Virk, G.S. ISO 13482–The New Safety Standard for Personal Care Robots. In Proceedings of the ISR/Robotik 2014; 41st International Symposium on Robotics, Munich, Germany, 2–3 June 2014; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Fosch-Villaronga, E.; Calleja, C.J.; Drukarch, H.; Torricelli, D. How Can ISO 13482:2014 Account for the Ethical and Social Considerations of Robotic Exoskeletons? Technol. Soc. 2023, 75, 102387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IEC 61508:2010; Functional Safety of Electrical/Electronic/Programmable Electronic Safety-Related Systems–Part 1: General Requirements (See Functional Safety and IEC 61508). ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2010.

- Fosch-Villaronga, E.; Shaffique, M.R.; Schwed-Shenker, M.; Mut-Piña, A.; van der Hof, S.; Custers, B. Science for Robot Policy: Advancing Robotics Policy through the EU Science for Policy Approach. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2025, 218, 124202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, K. Does Ascribing Robots with Mental Capacities Increase or Decrease Trust in Middle-Aged and Older Adults? Int. J. Soc. Robot. 2025, 17, 1617–1631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsumura, T.; Yamada, S. Shaping Empathy and Trust Toward Agents: The Role of Agent Behavior Modification and Attitude. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 116908–116923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holbrook, C.; Krishnamurthy, U.; Maglio, P.P.; Wagner, A.R. Physical Anthropomorphism (but Not Gender Presentation) Influences Trust in Household Robots. Comput. Hum. Behav. Artif. Hum. 2025, 3, 100114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, C.S.; Kim, Y.-K. The Role of the Human-Robot Interaction in Consumers’ Acceptance of Humanoid Retail Service Robots. J. Bus. Res. 2022, 146, 489–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, C.S.; Kim, Y.-K.; Jo, B.W.; Park, S.-h. Trust in Humanoid Robots in Footwear Stores: A Large-N Crisp-Set Qualitative Comparative Analysis (csQCA) Model. J. Bus. Res. 2022, 152, 251–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tobis, S.; Piasek-Skupna, J.; Neumann-Podczaska, A.; Suwalska, A.; Wieczorowska-Tobis, K. The Effects of Stakeholder Perceptions on the Use of Humanoid Robots in Care for Older Adults: Postinteraction Cross-Sectional Study. J. Med. Internet Res. 2023, 25, e46617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tobis, S.; Piasek-Skupna, J.; Suwalska, A.; Wieczorowska-Tobis, K. The Impact of Real-World Interaction on the Perception of a Humanoid Social Robot in Care for Institutionalised Older Adults. Technologies 2025, 13, 189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horstmann, A.C.; Krämer, N.C. The Fundamental Attribution Error in Human-Robot Interaction: An Experimental Investigation on Attributing Responsibility to a Social Robot for Its Pre-Programmed Behavior. Int. J. Soc. Robot. 2022, 14, 1137–1153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.-L.; Kwak, H.S. Effect of Cooking and Food Serving Robot Design Images and Information on Consumer Liking, Willingness to Try Food, and Emotional Responses. Food Res. Int. 2025, 214, 116626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Misaroș, M.; Stan, O.P.; Enyedi, S.; Stan, A.; Donca, I.; Miclea, L.C. A Method for Assessing the Reliability of the Pepper Robot in Handling Office Documents: A Case Study. Biomimetics 2024, 9, 558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, E.A.; Dudding, K.M.; Carrington, J.M. When to Err Is Inhuman: An Examination of the Influence of Artificial Intelligence-Driven Nursing Care on Patient Safety. Nurs. Inq. 2024, 31, e12583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Law, T.S.-T.; Yeung, S.S.S. Let Robots Tell Stories: Using Social Robots as Storytellers to Promote Language Learning among Young Children. Comput. Hum. Behav. Artif. Hum. 2025, 6, 100210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Orozco, D.; Valdez, R.; Uchuari, Y.; Fajardo-Pruna, M.; Quero, L.C.; Algabri, R.; Yumbla, E.Q.; Yumbla, F. YAREN: Humanoid Torso Robot Platform for Research, Social Interaction, and Educational Applications. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 106175–106187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Kang, T.; Song, D.; Ahn, G.; Yi, S.-J. Development of Dual-Arm Human Companion Robots That Can Dance. Sensors 2024, 24, 6704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Menassa, C.C.; Kamat, V.R. Siamese Network with Dual Attention for EEG-Driven Social Learning: Bridging the Human-Robot Gap in Long-Tail Autonomous Driving. Expert Syst. Appl. 2025, 291, 128470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiilavuori, H.; Sariola, V.; Peltola, M.J.; Hietanen, J.K. Making Eye Contact with a Robot: Psychophysiological Responses to Eye Contact with a Human and with a Humanoid Robot. Biol. Psychol. 2021, 158, 107989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, J.; Jeon, M. Happiness Improves Perceptions and Game Performance in an Escape Room, Whereas Anger Motivates Compliance with Instructions from a Robot Agent. Int. J. Hum.-Comput. Stud. 2025, 202, 103547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, S.; González-Jiménez, H.; Zheng, L. Help Please! Deriving Social Support from Geminoid DK, Pepper, and AIBO as Companion Robots. Int. J. Hum.-Comput. Stud. 2025, 203, 103577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trieu, N.; Nguyen, T. Enhancing Emotional Expressiveness in Biomechanics Robotic Head: A Novel Fuzzy Approach for Robotic Facial Skin’s Actuators. CMES–Comput. Model. Eng. Sci. 2025, 143, 477–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, X.; Wu, Y.; Nielsen, M.; Wang, F. Does Appearance Affect Children’s Selective Trust in Robots’ Social and Emotional Testimony? J. Appl. Dev. Psychol. 2025, 96, 101739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Research Question (RQ) | Keywords/Queries | Database |

|---|---|---|

| RQ1 | (“humanoid robot” OR “anthropomorphic robot”) AND (“human–robot interaction” OR HRI OR “human–robot collaboration” OR HRC) AND (safety OR “collision avoidance” OR fall) | Web of Science Scopus IEEE Xplore |

| RQ2 | (“humanoid robot” OR “anthropomorphic robot”) AND (cybersecurity OR “secure boot” OR “over-the-air” OR authentication OR “access control”) | Web of Science Scopus IEEE Xplore |

| RQ3 | (“humanoid robot” OR “collaborative robot” OR cobot) AND (“ISO 10218” OR “ISO/TS 15066” OR “ISO 13482” OR “IEC 61508” OR standard OR certification OR “risk assessment”) | Web of Science Scopus IEEE Xplore |

| RQ4 | (“humanoid robot” OR “anthropomorphic robot”) AND (ethical OR trust OR acceptance OR privacy OR GDPR) | Web of Science Scopus IEEE Xplore |

| Approach | Primary Sensing Modality | Sensing Technology | Main Safety Function | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Behavior-based safety layers | Human pose + robot state | External vision/motion tracking + kinematics | Proactive speed and trajectory adaptation. | [1,26,46,47,48,49] |

| Null-space motion | Internal state + obstacle pos. | Joint/task-space kinematics + obstacle estimates | Avoidance using redundancy without stopping the task. | [47,48,49] |

| Proximity-based “skins” | On-body proximity | Distributed proximity sensors | Blind-spot safety. | [50] |

| Emerging sensing | Chemical | Biomimetic chemical sensors | Detection of hazardous substances. | [51] |

| Visual–tactile hierarchy | Vision + tactile | Vision (prediction) + tactile (feedback) | Pre-impact deceleration + post-impact force control. | [52] |

| Active vision | Vision | Actuated cameras with dynamic gaze control | Minimizing occlusions and optimizing field of view. | [55] |

| Dynamic path planning | Range + robot state | Range sensors + bio-inspired planners | Stability on slippery on dynamic terrain. | [62,63] |

| Category | Key Method/Approach | Advantages | Disadvantages | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Perception and Detection | Multimodal Sensor Fusion (Vision + Tactile) | Distinguishes between accidental and intentional contact; high-accuracy contextual awareness. | High computational cost; data synchronization challenges; sensor noise. | [52,53,54,58] |

| AI-based Classification (Supervised Learning, Bayesian) | Fast response (<20 ms); high classification accuracy (99.6%); enables context-appropriate reaction. | Requires extensive training data; reliance on model generalization; potential “black box” unreliability. | [57,58] | |

| Proximity Sensing Skins | Whole-body awareness; effective in confined spaces and for blind spots. | Wiring complexity; calibration maintenance; potentially limited range compared to vision. | [50,51] | |

| Proactive Avoidance (Pre-Impact) | Safety Metrics/Separation Monitoring | Continuously guarantees a minimum safety distance; standard-compliant approach (SSM). | Can reduce robot productivity (frequent stops); conservative behavior in dense crowds. | [26,46] |

| Null-Space Motion | Utilizes kinematic redundancy to avoid obstacles without interrupting the primary task. | Applicable only to redundant manipulators; limited by joint limits and singularity issues. | [47,48,49] | |

| Active Vision/Dynamic Planning | Optimizes observation direction to minimize occlusion; adapts trajectory in real time. | Complex control architecture; depends heavily on environment predictability. | [55,59,60,61,62,63,64,65] | |

| Impact Mitigation (Contact) | Active Compliance (Impedance/Admittance Control) | Software-adjustable stiffness; adaptable to different tasks; no hardware modification needed. | Bandwidth is limited by control loop and actuators; risk of instability; requires precise force sensing. | [56,66,67,68] |

| Passive Compliance (Soft Robotics, Mechanisms) | Inherently safe; infinite bandwidth response to impact; energy absorption. | Lower positioning precision; difficult to model and control; lower payload capacity. | [69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78] | |

| Emergency Response (Fail-Safe) | Fall Prediction and Management | Prevents or minimizes damage from stability loss; protects environment. | High dynamic complexity; inevitable hardware damage risk if recovery fails. | [36,37,38,79] |

| Fault-Tolerant Control | Maintains stability during actuator/sensor failure; prevents chaotic motion. | Design complexity; requires redundancy; effective only up to specific failure limits. | [84,85,86] |

| Cybersecurity Measure | Primary Threat Dimensions Addressed | Deployment Complexity | Direct Impact on Physical Safety | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Biometric Access Control and Blockchain | Confidentiality, Privacy, Integrity | High | Medium | [89,90] |

| (preventing unauthorized user access and data tampering) | (requires deep learning models and decentralized network infrastructure) | (prevents unauthorized commands; primary focus is data protection) | ||

| Secure Over-the-Air (OTA) Updates | Integrity, Availability | Medium/High | High | [92,93] |

| (ensuring software authenticity and system boot) | (requires PKI, encryption, and secure bootloader implementation) | (prevents injection of malicious code that could disable collision avoidance) | ||

| Real-time Communication Redundancy (e.g., EtherCAT) | Availability | Medium | High | [3,91] |

| (ensuring continuous control-signal flow) | (requires dual-channel architecture and specialized drivers) | (prevents loss of stability and erratic motion due to signal loss) | ||

| Encrypted Teleoperation and Command Validation | Integrity, Confidentiality | Medium | High | [2,94] |

| (preventing hijacking of remote-controlled sessions) | (standard encryption protocols and authentication logic) | (prevents attackers from remotely driving the robot into hazardous states) | ||

| AI-based Anomaly Detection | Integrity, Availability | Medium | Medium | [85,101] |

| (detecting abnormal software/hardware states) | (depends on model architecture, e.g., CNN or statistical methods) | (enables fail-safe reaction to unexpected operational faults) |

| Standard | Title | Focus Area |

|---|---|---|

| ISO 10218-1:2025 | Robotics—Safety requirements Part 1: Industrial robots | Safety requirements specific to industrial robots. |

| ISO 10218-2:2025 | Robotics—Safety requirements Part 2: Industrial robot applications and robot cells | Safety of industrial robot applications and robot cells. |

| ISO/TS 15066:2016 | Robots and robotic devices—Collaborative robots | Safety requirements for collaborative industrial robot systems |

| ISO 13482:2014 | Robots and robotic devices—Safety requirements for personal care robots | Mobile servant robot, physical assistant robot, person-carrier robot. |

| IEC 61508:2010 | Functional safety of E/E/PE safety-related systems | Electrical, Electronic, and Programmable Electronic Safety-Related Systems |

| Safety Domain | Key Issue | Methods/Approaches | Key References (ID) |

|---|---|---|---|

| RQ1—Physical safety | Proactive collision avoidance in shared spaces | Behavior-based safety layers; safety-metric controllers (minimum separation); null-space motion; proximity sensing + multimodal fusion; active vision | [1,26,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55] |

| Distinguishing accidental vs. intentional contact | Collision detection and identification (supervised learning + Bayesian decision); posture/gaze-aware intent inference | [57,58] | |

| Safety-constrained motion planning | Neural dynamic schemes; probabilistic/nature-inspired planners; multi-agent RL with MPC safety filters; symbolic scheduling for multi-robot | [59,60,61,62,63,64,65] | |

| Active (software) compliance | Impedance control (virtual mass-spring-damper); online MPC tuning; control-barrier enforcement; precise torque | [66,67,68] | |

| Passive (hardware) compliance | Soft-robotic structures (PAMs); biomechanical damping (meniscus-like); lightweight hands (cable/fluidic/SMUFR); stiffness optimization | [66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75] | |

| Fall safety and stability | Early fall prediction; online selection of self-protective fall | [36,37,38,79,80,81,82,83] | |

| Fault tolerance and reliability | Thermal management of high-performance chips; adaptive fault-tolerant sliding-mode control; passive-safety stop behaviors | [84,85,86,87] | |

| RQ2—Cybersecurity | Unauthorized access/command hijacking (telepresence/IoT) | Deep learning-based biometric modeling; symmetric and asymmetric encryption modules; decentralized data transmission | [88,89] |

| Secure over-the-air updates | End-to-end encryption of update packages; cryptographic firmware signing; device-side secure bootloader and integrity checks | [92,93] | |

| Data/privacy protection in sensing | Real-time anonymization of collected visual data; blockchain network for secure data transmission and validation | [89,120,121] | |

| Deterministic, reliable, real-time communication | EtherCAT fieldbus with dual-channel redundancy; modular, distributed real-time control | [3,91] | |

| RQ3—Standards and regulation | Baseline industrial robot safety | ISO 10218-1/-2 requirements for design, manufacture, and integration | [103,104] |

| Collaborative operation guidance | ISO/TS 15066 (modes: SRMS, hand-guiding, SSM, PFL; biomechanical limits) | [106] | |

| Personal-care robot safety | ISO 13482 (mobile servant, person-carrier, physical assistant robots) | [107] | |

| Functional safety lifecycle | IEC 61508 (safety-critical software and hardware) | [108] | |

| Risk assessment and benchmarking gaps | PFMEA/HAZOP/FTA + data-driven incident archetypes; evidence-based benchmarking incl. safety and HRI quality | [24,25,39,102] | |

| RQ4—Ethical and social implications | Trust, acceptance, anthropomorphism | Behavior/demeanor tuning; study of anthropomorphism’s effect on trust; analysis of real-world interactions’ positive effect on perception | [111,112,113,114,115] |

| Elder-care adoption and user perception | Real-world interactions in elder care; include users’ perspectives in governance | [12,116,117,118] | |

| ASD therapy/education use | Predictable social cues; multi-armed bandit; storytelling for language and bonding | [16,17,18,122] | |

| Nonverbal understanding and intent communication | Multimodal perception (vision/touch; posture/gaze); clear motion-intent signaling in shared work | [58,125,126,127] | |

| Privacy and data governance | Develop ethical/legal frameworks for data handling, storage, and use; incorporate user (e.g., seniors’) perspectives into AI governance | [10,11,120,121] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kóczi, D.; Sárosi, J. Safety Engineering for Humanoid Robots in Everyday Life—Scoping Review. Electronics 2025, 14, 4734. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics14234734

Kóczi D, Sárosi J. Safety Engineering for Humanoid Robots in Everyday Life—Scoping Review. Electronics. 2025; 14(23):4734. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics14234734

Chicago/Turabian StyleKóczi, Dávid, and József Sárosi. 2025. "Safety Engineering for Humanoid Robots in Everyday Life—Scoping Review" Electronics 14, no. 23: 4734. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics14234734

APA StyleKóczi, D., & Sárosi, J. (2025). Safety Engineering for Humanoid Robots in Everyday Life—Scoping Review. Electronics, 14(23), 4734. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics14234734