1. Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic significantly intensified the emotional and physical challenges associated with social distancing, sparking a surge of interest in Computer-Mediated Communication (CMC) technologies that support mediated touch [

1]. In particular, interfaces that enable mediated social touch have emerged as promising tools to restore emotional closeness during periods of prolonged isolation [

2]. As we reimagine what digital touch might look like in the context of remote interaction, the design of such technology becomes critically important [

3]. Affective communication systems, such as huggable interfaces, must not only function technically but also resonate emotionally with users [

4].

However, these systems are not experienced uniformly. How users perceive and emotionally respond to huggable communication devices depends on individual differences—particularly how they interpret the physical form and emotional intent of the device. The appearance of a huggable device—its shape, degree of anthropomorphism, and tactile affordances—plays a key role in shaping emotional perception, usability, and acceptance. Devices that appear overly human-like, childlike, or visually ambiguous may provoke discomfort or rejection instead of fostering connection [

5].

Design preferences for emotionally expressive technologies are influenced by multiple factors. Although prior research has explored how cultural norms shape attitudes toward social touch [

6,

7], this study shifts the focus to personality traits as drivers of user preference. Traits such as openness, extraversion, and conscientiousness have been shown to influence how people engage with interactive systems—including their preferences for emotional expressiveness, simplicity, or anthropomorphic features. In the field of Human–Robot Interaction (HRI), personality has been identified as a key predictor of robot acceptance [

8]. The Big Five personality model offers a well-established framework for investigating how such traits shape interactions with emotionally communicative technologies [

9,

10]. For example, previous research found that users less in extraversion and emotional stability preferred less human-like robots, suggesting that appearance preferences may reflect deeper psychological dispositions [

11]. At the same time, a distinction exists between huggable robots and systems designed primarily as mediating communication devices. Huggable robots are often created as social companions intended to provide comfort and emotional support through direct physical interaction with users [

8,

11]. In contrast, huggable communication interfaces serve as communication artifacts connecting two remote users, with the physical body of the device acting as a substitute for the partner’s presence. Although their purpose differs, certain design features explored in huggable robots may also inform the design of huggable communication artifacts. This shift in role nevertheless reshapes users’ expectations and design priorities for these emotionally oriented communication technologies.

Building on this distinction, the present study investigates how personality traits influence user preferences for the appearance of huggable communication devices. As a practical example, we introduce HugBits, a soft, cushion-shaped device designed to convey emotional support through remote tactile signals such as vibration and ambient light. The study examines whether users’ preferences for different HugBits shapes, ranging from more neutral to more anthropomorphic, are associated with their Big Five personality traits. To address this, we first outline the design rationale behind HugBits and describe the selection of seven alternative shapes developed through a participatory design workshop and a review of related huggable technologies. We then present the findings of an online survey conducted with 79 Polish participants, who evaluated the different shapes and completed the Big Five Inventory (BFI-44). The use of a culturally homogeneous sample allowed us to control for cultural variation and focus more directly on personality-driven effects. This paper presents the results of that survey, identifying the visual and conceptual features that shaped user preferences and offering design insights for emotionally expressive user-centered huggable interfaces in computer-mediated communication. By emphasizing personality-based variation in design expectations and emotional perception, this work contributes to a more personalized and inclusive approach to the design of mediated social touch.

2. Related Work

This section reviews prior research on huggable and tangible interfaces designed to convey emotional support or mediated social touch. We specifically focus on artifacts that are physically held, hugged, or placed in the environment, encompassing both huggable communication devices and huggable robots intended for emotional or therapeutic interaction. Wearable systems such as vests, wristbands, or garments are excluded from this review, as they represent a distinct class of technologies emphasizing on-body sensing or actuation rather than shared, co-present physical forms. By focusing on non-wearable haptic artifacts that embody or facilitate interpersonal affective exchange, we highlight how material form, anthropomorphism, and spatial presence influence users’ emotional experiences and perceptions of mediated intimacy. In this context, anthropomorphism refers to the extent to which a device’s form or behavior evokes human or animal qualities—such as the presence of limbs, facial features, or lifelike motion—that encourage users to attribute emotional or social characteristics to it. Varying degrees of anthropomorphism, from abstract object-like designs to expressive companion-like forms, play a crucial role in shaping how users interpret and emotionally engage with huggable technologies.

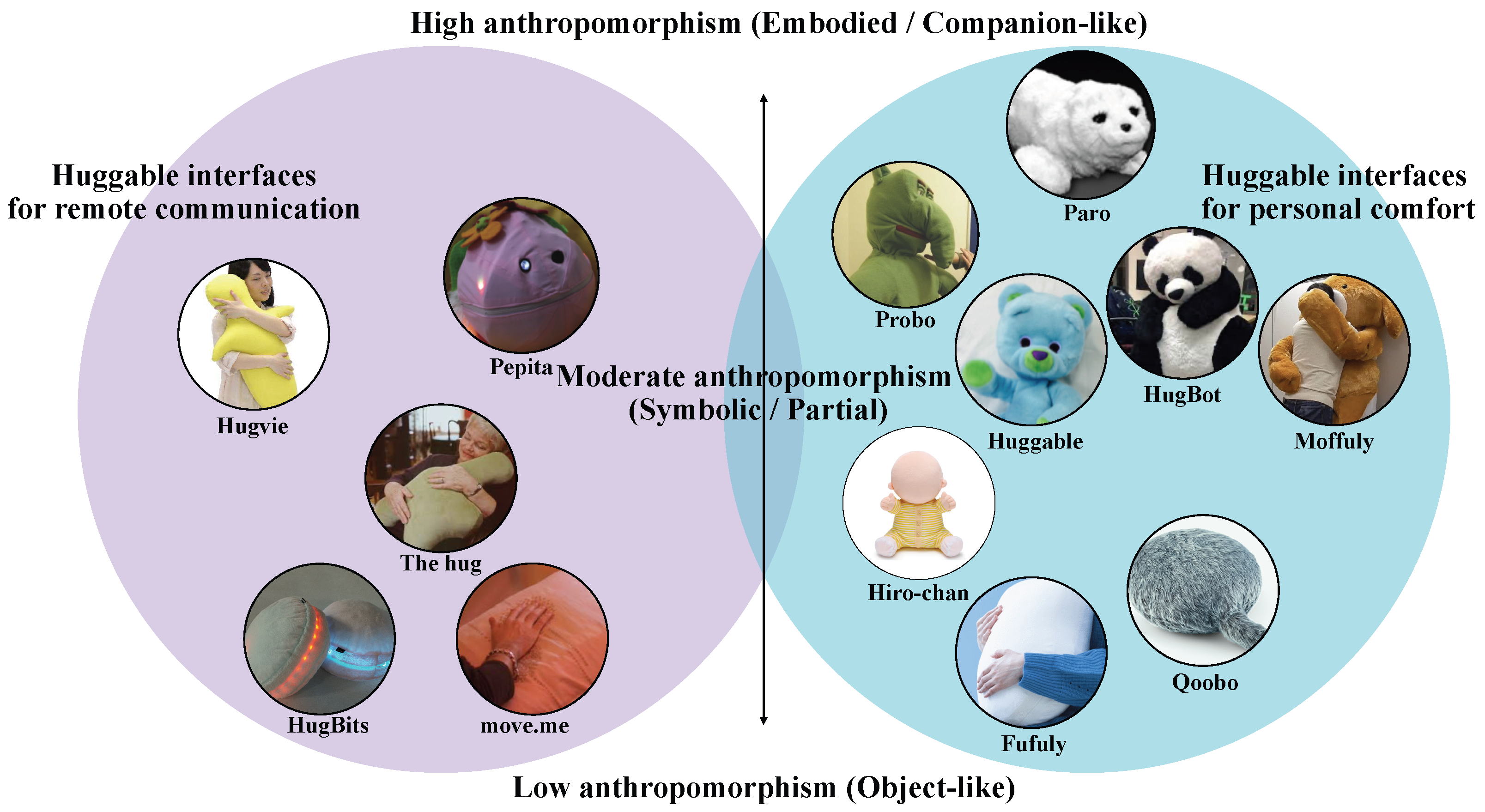

Figure 1 situates the huggable systems reviewed in the literature within two main categories—those designed for remote communication and those aimed at personal comfort—distributed along an axis describing their degree of anthropomorphism.

2.1. Huggable Interfaces for Remote Communication

Huggable devices for remote communication are often designed as ambient emotional channels, enabling non-verbal interaction through gestures such as hugging, squeezing, or holding [

4]. These systems extend traditional computer-mediated communication by embedding affective cues into tangible forms that transmit physical sensations over a distance. Interactions are typically supported by haptic (e.g., vibration, pressure) or visual (e.g., color, light) feedback [

12], transforming simple tactile gestures into signals of emotional presence and connectedness.

Several representative systems illustrate this design approach, differing primarily in their degree of anthropomorphism and integration within domestic environments.

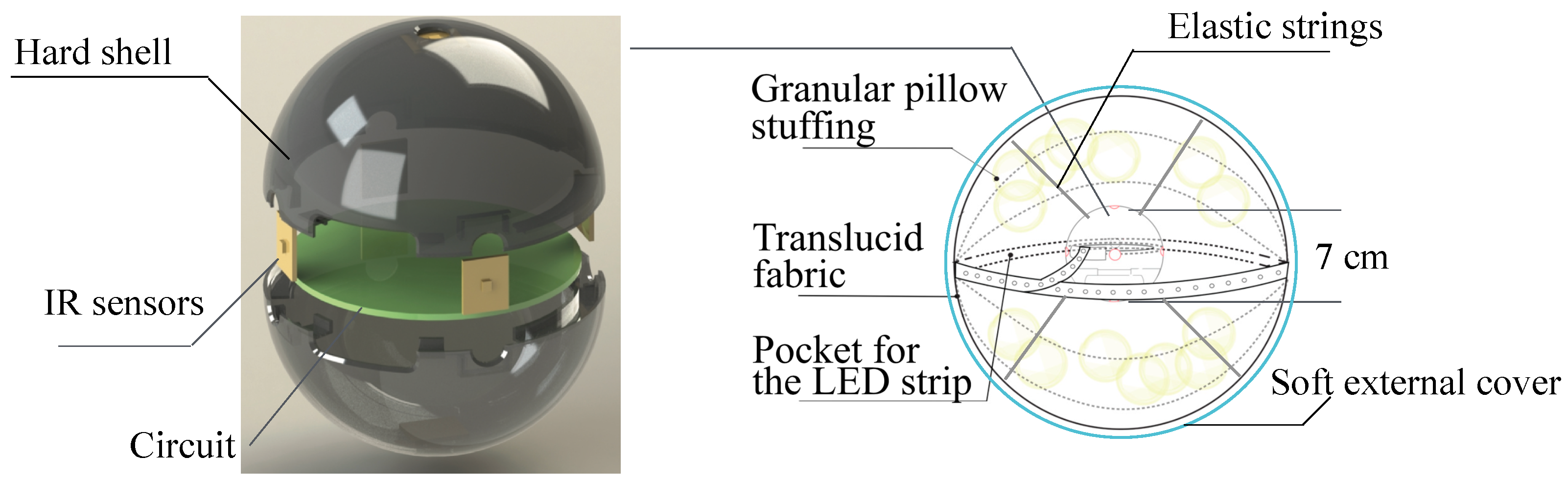

Move.me presents one of the most minimal examples: a set of square cushions equipped with light feedback that subtly respond to touch [

13]. Its neutral, object-like form allows it to blend into the surroundings, prioritizing comfort and discretion over expressiveness. Similarly, HugBits employs a round, cushion-shaped robotic form that synchronizes hugging gestures between paired devices through soft vibration and ambient light [

14]. While it maintains a neutral appearance, its responsive feedback and paired configuration evoke a sense of co-presence between remote users. Pepita, the conceptual predecessor of HugBits, was a huggable robotic companion that encouraged mediated interaction through a paired-device configuration [

15]. Its slightly anthropomorphic caricature-like form—with a rounded shape and minimal facial features—was meant to balance emotional expressiveness with social acceptability. The Hug adopts a more symbolic anthropomorphic form by incorporating large and flexible arms that wrap around the user, representing the physical act of embrace [

16]. Finally, Hugvie introduces a distinctly human-like outline—featuring a head and torso, but no facial features—allowing users to hold the device while speaking on the phone [

17]. Its simplified human silhouette evokes emotional closeness, while avoiding the uncanny effect that more detailed humanoid forms might produce. Together, these examples reveal a spectrum of design strategies—from abstract, object-like artifacts (Move.me, HugBits) to slightly more character-like forms (Pepita, The Hug, Hugvie)—that illustrate how varying degrees of anthropomorphism influence both social acceptability and emotional resonance in mediated-touch systems.

2.2. Huggable Interfaces for Personal Comfort

Unlike communication-oriented devices, comfort-focused huggables are designed for individual emotional support rather than interpersonal connection. They rely on softness, warmth, and familiar shapes to provide stress relief, relaxation, and a sense of companionship. In the literature, huggable robots represent the most prevalent category of huggable systems and serve as valuable design references for communication-oriented artifacts such as HugBits. Because these robots are not intended to mediate remote interaction, they are typically used in private contexts and are not required to maintain visual subtlety or environmental neutrality. Instead, they emphasize physical engagement and emotional resonance through expressiveness and lifelike behavior.

Representative examples illustrate a wide range of anthropomorphic expression. Fufuly, for example, adopts a minimalist aesthetic, expressing comfort through rhythmic breathing motion rather than anthropomorphic features [

18]. Qoobo, similarly, is a cushion with a robotic tail that wiggles in response to touch, evoking the companionship of a pet while maintaining an abstract, object-like form [

19]. Hiro-chan, on the contrary, assumes a simplified human-infant silhouette with a face without features and gentle movements to convey emotional responsiveness in elderly care settings [

20]. More overtly anthropomorphic designs include Moffuly [

21] and HugBot [

22], both of which adopt teddy bear-like morphologies with articulated arms capable of returning a user’s hug, reinforcing physical reciprocity and prosocial behavior. Probo, an elephant-inspired robot with a fully articulated face and expressive trunk, was developed to support empathy and social interaction in children through nuanced emotional cues [

23]. The Huggable combines a plush bear form with embedded sensors and actuators to facilitate rich, emotionally expressive interactions in healthcare and educational contexts [

24]. At the upper end of anthropomorphism, Paro takes the form of a baby seal with eyes, fins, and realistic fur, inviting nurturing and care through its animal-like responsiveness [

25]. These comfort-oriented huggable robots demonstrate how varying degrees of anthropomorphism—from abstract cushions to animal- and human-like embodiments—can elicit empathy, trust, and emotional attachment. Although often too lifelike or playful for public or shared settings, their design strategies provide valuable insights into how physical form and expressive behavior can be leveraged to evoke intimacy and affective connection in future huggable communication systems.

2.3. Bridging the Two: Designing for Hybrid Roles

Communication- and comfort-oriented interfaces have traditionally served different purposes: the first mediate user presence and expressivity across distance, while the latter provide personal reassurance and emotional regulation. Comfort-oriented systems often display autonomous behaviors that create a sense of social presence and offer emotional comfort. In contrast, huggable CMC devices serve a different purpose: instead of acting as independent social agents, they function as communication channels connecting two remote users, with agency arising from the users themselves rather than the system. However, this distinction is increasingly blurred as digital communication becomes more pervasive. In a context where many people live alone, work remotely and maintain geographically distributed relationships, there is a growing need for technologies that address both connectedness and well-being simultaneously.

Therefore, vast communication artifacts can evolve towards a hybrid role—one that not only transmits affective signals between users but also provides self-soothing and emotional support when used alone. However, achieving this balance requires careful attention to form and expressivity: designs that are too neutral may fail to convey warmth, whereas those that are overly anthropomorphic risk discomfort or social inappropriateness in shared environments. The challenge lies in defining an aesthetic and behavioral middle ground that evokes intimacy without intrusiveness, blending the ambient subtlety of communication artifacts with the emotional depth of huggable robots.

This study addresses these questions by investigating user preferences for the visual appearance of a huggable communication interface designed for computer-mediated communication. By evaluating form variations informed by literature and participatory workshops through a user survey, we aim to clarify how shape design and emotional function jointly influence the acceptance and perceived value of huggable technologies in everyday life. Finally, since users’ responses to huggable technologies can vary between individuals, the present study also explores how personality traits relate to appearance preferences, as described in the

Section 3.

4. Evaluation

The survey used a narrative-based framework to engage the participants and provide a contextual framework for the HugBits concept. After giving their informed consent, the participants completed a brief demographic questionnaire. To familiarize participants with the concept of HugBits, we presented a short explanation of the function and purpose of the device. This was followed by a fictional narrative that depicted a couple separated during the COVID-19 pandemic who used HugBits to maintain a sense of physical closeness. The story was designed to illustrate both the functionality of the device and its role as a tool for long-distance, emotionally supportive communication. To ensure attentiveness, we have embedded comprehension questions about the story as attention checks. Participants were allowed to revisit earlier pages to modify their responses; incorrect answers to these questions were used to flag inattentive participants and exclude them from the analysis.

Once participants understood the context and intended use of HugBits, the survey moved to the shape preference section. The participants were shown an illustration of the seven HugBits shapes. To avoid bias or emotional associations, in the survey we labeled the HugBits designs generically (Hugbits A, B, etc.). For clarity in this paper, we now use descriptive labels, as shown in

Figure 5. They were asked to imagine the softness of a conventional cushion while envisioning themselves sending or receiving a hug, signaled by glowing HugBits. They were also instructed to mentally place the device in their daily environments, visible and accessible at all times. To support this scenario, we included a simple illustration showing a user interacting with HugBits in a domestic setting (

Figure 6).

Participants first selected their favorite shape from seven options using interactive buttons, then completed a multiple choice question on preferred features—drawn from the earlier participatory workshop—and finally responded to an open-ended prompt describing the most important feature of the list. They then identified their least favorite shape using the same format, with feature descriptions rephrased negatively (e.g., “comfortable to hug” became “uncomfortable to hug”). Following shape selection, participants viewed two versions of their favorite HugBits, one with eyes (human-like features) and one without (object-like)—as shown in

Figure 6. They rated two statements on a 7-point Likert scale (“I like HugBits with human features” and “I like HugBits with object features”) and made a forced choice selection between the two.

The survey was concluded with the Big Five Inventory (BFI-44) [

9], which was used to examine potential correlations between the personality traits of the participants and their preferences for the HugBits shapes and features. It was administered in Polish and had an average completion time of approximately 12 min. Data were collected using SurveyMonkey [

28], and the complete survey instrument is available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Participants

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Engineering, Information and Systems at the University of Tsukuba (Application No. 2021R558). Participants were recruited from a Polish university through two primary methods: printed posters displayed in campus corridors and announcements posted in relevant Facebook groups. In addition, participants were encouraged to share the questionnaire link with their family and friends to broaden the sample. Participation was voluntary and no financial compensation was provided. In total, 101 responses were collected. Of these, 22 were excluded from the analysis; 10 were entirely incomplete and 12 failed the attention check embedded in the narrative section of the survey. The final sample consisted of 79 valid responses. All participants were Polish nationals and native Polish speakers. The age group most frequently reported was 45 to 54 years (n = 25), followed by 25 to 34 years (n = 19). The sample included 54 women (68.4%), 24 men (30.4%), and one individual (1.3%) who preferred not to disclose their sex. Most of the participants (n = 63, 79.7%) had completed higher education. A large proportion of the participants (n = 58, 73.4%) indicated that they had experienced physical separation from someone with whom they had a close emotional relationship. The duration of separation reported the most frequently was less than 6 months (n = 18), while the median duration was between 1 and 2 years.

5. Results

5.1. Shape Preference of HugBits

We analyzed user preferences using chi-square tests to assess the statistical significance of shape selection. For the most popular shape, a significant difference in shape preference was found (). Post hoc binominal tests with Holm-Bonferroni correction for multiple comparison indicated that Snowman was selected significantly more often than expected under a uniform distribution (43% vs. 14. 3%, ).

In the same manner, a significant difference was found for the least favorite shape (

), and the post-hoc tests revealed that

Baby was selected as the least favorite significantly more than expected (35% vs. 14.3%,

), and the number of selection of Snowman was significantly less than the expected (1.3% vs. 14.3%,

). The complete results are summarized in

Table 1.

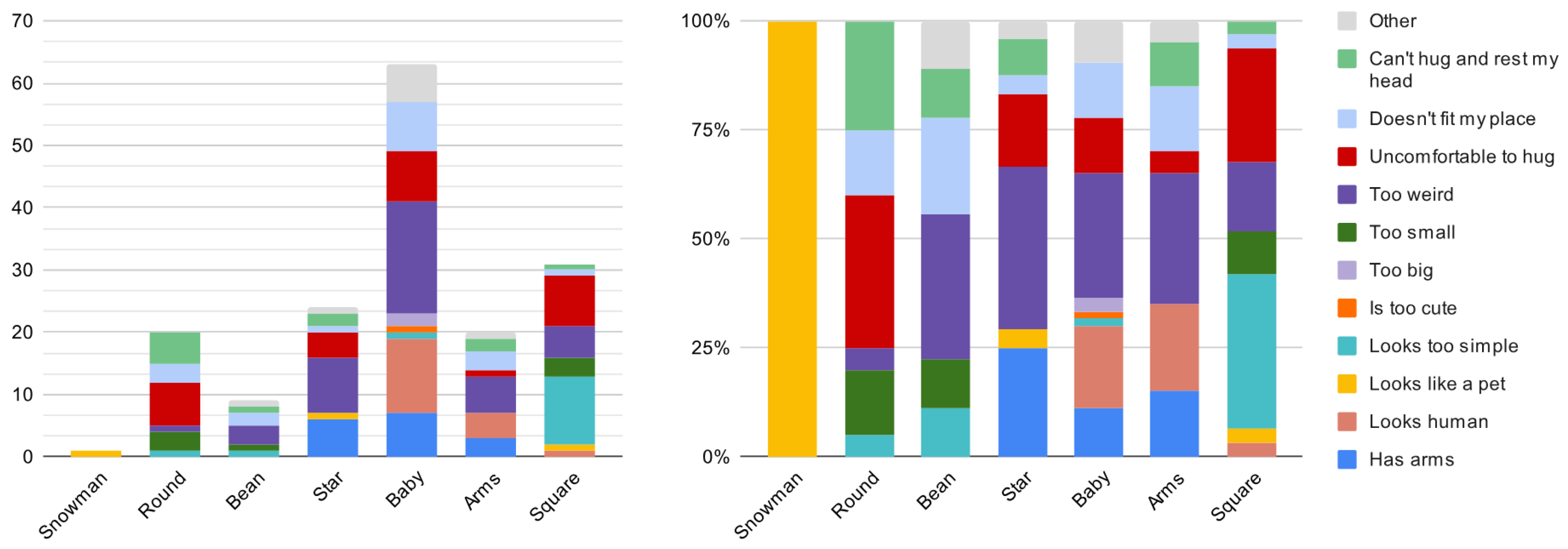

We examined potential associations between participants’ most and least preferred HugBits shapes. Although some patterns were observed, such as Snowman-preferring individuals often disliking Baby (13 respondents), Square-preferring individuals disliking Baby (6), and Bean-preferring individuals disliking Star (5), these trends were not statistically significant. Regarding the features associated with participants’ favorite HugBits, 62% of respondents selected “It looks comfortable to hug” as the most important characteristic. Other commonly mentioned features included “It is simple” (39%) and “I can hug and rest my head on it at the same time” (34%). The complete distribution of the selected features is shown in

Figure 7. The left panel displays the absolute number of respondents who selected each feature, grouped by their preferred HugBits shape. This allows for a direct comparison of how many individuals associated specific features with different types of HugBits. In contrast, the right panel shows the relative distribution of features within each shape group, indicating the proportion of respondents who selected a given feature among those who chose that shape as their favorite. This normalized view enables easier comparison between shapes, regardless of the number of respondents in each group.

Regarding the least favorite HugBits, the features most frequently indicated were “It is too weird” (42%) and “It looks uncomfortable to hug” (34%).

Figure 8 presents the full distribution of the selected features. As in the previous figure, the left panel shows the absolute number of respondents who associated each feature with their least preferred HugBits shape. The right panel displays the relative percentages, indicating the proportion of respondents within each shape group who selected a given feature. The responses classified as “Other” reflect the optional open responses from the participants, some of which are discussed in

Section 6.

5.2. HugBits with Human or Object Features

To assess the preferences between HugBits with human-like features (e.g., eyes) and those resembling objects, we asked participants to choose between the two. The majority of respondents (70.27%) favored HugBits similar to objects over those with characteristics similar to humans. Recognizing that shape preference could influence this outcome, we further analyzed responses by shape category. The preferences for the characteristics of the human or object varied significantly between the shapes (), with a Cramér V of 0.5049 indicating a strong association between the characteristics of the shape and the characteristics. Participants tended to prefer human-like features in the shapes of Round (0.2165), Star (0.2176), Baby (0.1602) and Arms (0.2247). In contrast, preferences shifted toward object-like features for the Bean (), Square (), and Snowman () shapes.

To explore these patterns in more detail, we examined participants’ ratings on two items on the Likert scale: ‘I like HugBits with human characteristics’ and ‘I like HugBits that resemble an object’. Responses were scored on a scale from −3 (Strongly disagree) to +3 (Strongly agree).

Figure 9 presents the average preference scores by shape. Participants rated object-like HugBits more favorably for Bean, Square, and Snowman, while Baby and Arms received higher ratings when paired with human-like features.

5.3. Personality Type and Preference to HugBits Form

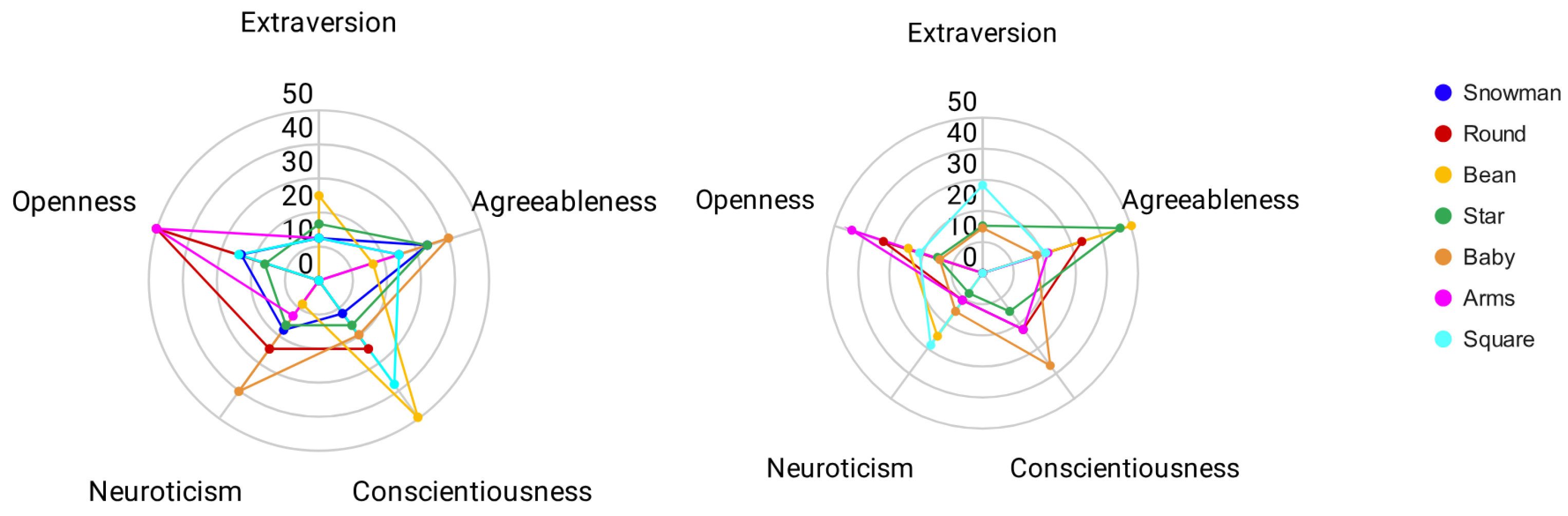

To investigate whether preferences for HugBits shape and appearance are related to personality traits, we analyzed responses to the Big Five Inventory (BFI-44). Specifically, we examined whether the dominant personality trait of each participant could predict their preference for specific HugBits forms.

Figure 10 shows the distribution of the dominant Big Five traits: Extroversion, Agreeableness, Conscientiousness, Neuroticism, and Openness across the HugBits shapes (left) of participants and the least favorite (right). The percentages reflect the proportion of respondents within each shape group exhibiting a given dominant trait. To examine whether personality traits predicted preferences for specific shapes, we performed a series of binary logistic regression analyzes. For each of the seven shapes, a separate model was estimated with the choice of that shape (selected = 1 vs. not selected = 0) as the dependent variable and the five personality trait scores as predictors. This approach allowed us to evaluate whether individual differences in personality were associated with increased or decreased odds of selecting a given shape. Then, the significance at the model level was assessed using a likelihood ratio test comparing the full model (five predictors) to an intercept-only model.

After applying Holm–Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons, none of the regression models reached statistical significance for most or least favorite shape selections. However, at the uncorrected level, modest associations were observed in the models for predicting: Bean as the most favorite (), Baby as the least favorite (), and Square as the least favorite (). At the coefficient-level of these models, Extroversion () and Openness () showed associations with Bean preference, while Conscientiousness predicted Baby (), and Extroversion () predicted Square as the least favorite shape. These findings did not remain significant after correction and should be considered exploratory.

To identify broader patterns, participants were grouped according to their combined preferences for cushion shape (i.e., Round, Snowman, Baby), and appearance (human-like vs. object-like). The initial trends observed in

Figure 9 suggested that participants who favored limbless forms (e.g., designs without arms) also tended to prefer object-like appearances. For classification purposes, a score was calculated for each shape, defined as the difference between the average preference for object-like features and the average preference for human-like features, as follows:

where

represents the average rating for features similar to objects and

represents the average rating for features similar to humans for each shape. Then a median split of the values

was applied to divide the shapes into two groups. Using this method, the Snowman shape score corresponded to the median value, resulting in the following classification: (1) Limbed HugBits (scores lower than the median): Arms, Baby and Star; and (2) Limbless HugBits (scores equal to or higher than the median): Snowman, Round, Square, and Bean.

Subsequently, we revisited the personality data and, to enhance representational accuracy, included both the first and second most dominant personality traits for each participant.

Figure 11 presents the relationship between the HugBits preferences (considering both shape and feature type) and personality traits. In particular, consistent patterns emerged across traits: participants, regardless of their dominant personality dimension, generally preferred limbless HugBits shapes, while limbed HugBits designs were more frequently ranked among their least favored.

6. Discussion

This study was motivated by the need to identify the appropriate aesthetic qualities of a huggable interface designed to support remote communication. A review of existing interactive systems revealed a wide spectrum of design approaches (

Figure 1), ranging from abstract product-like objects to more anthropomorphic companion-like interfaces. Combined with insights from a participatory design workshop, this informed the selection of seven distinct shapes for user evaluation. We ask the following question: What kind of appearance most positively shapes users’ impressions of a huggable communication interface? Using HugBits as a conceptual anchor, we concealed its original design and instead introduced participants to the device through a narrative-based survey, allowing evaluations based solely on functionality and visual design.

Our analysis revealed a clear preference for the Snowman shape, which was selected much more often than expected by chance. Participants frequently described this design as warm, familiar, and comfortable, emphasizing its neutral aesthetic and ergonomic form that made it suitable for hugging and resting the head. These results align with open-ended feedback, reinforcing the Snowman appeal as a huggable communication interface. In contrast, the Baby shape emerged as the least favored option, being chosen as least favorite significantly more often than expected. Qualitative comments described this design as awkward or even unsettling, with some respondents comparing it to a weapon or an erotic doll. Such reactions highlight the risks of anthropomorphic design in emotionally intimate contexts, where cultural interpretations can shape user perceptions in unpredictable ways. Interestingly, the Baby design was adapted from previous studies with Japanese users [

17], suggesting that cultural traditions such as animism may explain why it was positively received in some contexts but rejected in others. These findings point to the importance of cultural and contextual sensitivity when designing huggable interfaces, as anthropomorphic features can evoke comfort in some cultures but discomfort in others.

Participants’ feature selections offer deeper insight into why certain shapes were favored or disliked. A consistent preference for comfort and simplicity suggests that huggable communication interfaces should prioritize designs that feel physically inviting and emotionally neutral (

Figure 7). The possibility of resting one’s head also emerged as an important feature, emphasizing the role of ergonomic considerations in shaping the user experience. In contrast, negative reactions toward designs perceived as weird or uncomfortable to hug highlight how overly unconventional or anthropomorphic forms can undermine user acceptance (

Figure 8). Interestingly, even the plain square cushion was sometimes criticized as too simple, indicating that while users value approachability, the unique function and emotional role of a huggable communication interface may require a form that is distinct from conventional cushions. In addition, participants’ evaluations of human-like versus object-like versions of HugBits (

Figure 9) provide further nuance to these findings. In this comparison, human-like referred specifically to the presence of facial features—such as eyes—that made the interface resemble a companion rather than a neutral object. The results revealed a tendency for participants to prefer human-like versions when the base shape was already expressive or suggestive of a human form, such as the Arms or Baby designs, whereas simpler shapes—like Bean, Snowman, and Square—were generally preferred without facial features. This trend aligns with the previous literature (

Figure 1) that companion-like huggable robots designed for personal comfort often incorporate more anthropomorphic cues, while communication-oriented huggable artifacts rely on neutral, object-like forms to preserve social acceptability and emotional subtlety in shared environments.

A core question in this study was whether personality traits, measured using the BFI-44, could predict user shape preferences. Logistic regression analyses revealed no statistically significant associations after correcting for multiple comparisons, although some exploratory patterns emerged at the uncorrected level. For instance, Extroversion and Openness appeared modestly related to choosing Bean as a favorite shape, while Conscientiousness and Extroversion showed potential links to disliking Baby or Square. Because these effects did not survive correction, they should be interpreted with caution. Taken together, the findings suggest that personality alone may not be a primary driver of shape preference in huggable interfaces. Instead, preferences likely reflect a complex interaction between personality, aesthetic sensibilities, emotional associations, and cultural norms. Beyond personality effects, responses across participant groups consistently favored cushion-like designs without limbs (

Figure 11). This tendency echoes the distinction we defined in the Results between Limbed and Limbless HugBits: participants consistently rated limbless forms—those lacking explicit arms or appendages—as more comfortable, socially acceptable, and visually neutral. In contrast, limbed designs, while more expressive, were more often described as awkward or overly anthropomorphic. This finding highlights how subtle variations in limb presence can shift users’ emotional interpretation of the device from communicative artifact to companion-like entity, influencing both comfort and social acceptability. This general preference for hug-suggestive yet neutral forms suggests that users appreciate emotional expressiveness but wish to avoid the social or aesthetic awkwardness that overly human-like or toy-like designs can evoke. Previous research indicates that anthropomorphic or pet-like forms are often associated with children’s toys [

29,

30], which can make adults reluctant to use such devices in shared environments. The feedback of the participants in our study echoed this concern, highlighting the appeal of emotionally supportive devices that enrich social interaction rather than attempt to replace human connection. Together, these findings underscore the importance of aesthetic restraint and emotional subtlety in the design of huggable interfaces for socially situated contexts.

Several factors may explain the lack of statistically significant associations between personality traits and HugBits preferences. First, our sample composition was culturally homogeneous (all Polish participants) and skewed toward middle-aged adults, potentially limiting variability in both personality traits and aesthetic judgments. Second, we used a Big Five self-report inventory (BFI-44), which, although widely validated, may not capture context-specific emotional dispositions relevant to tactile or embodied technologies. Third, the image-based online methodology may have emphasized visual and functional attributes over affective or interactive experiences where personality differences might emerge more strongly. Finally, cultural conventions surrounding anthropomorphism and emotional expressiveness likely exerted stronger, more uniform influences than individual personality traits. Future studies with larger, cross-cultural samples and richer in-person interactions may clarify whether personality effects become more salient when these methodological constraints are addressed. It should be noted that HugBits’ form is constrained by its intended interaction modality: hugging. Although the most preferred shapes, such as Snowman and Bean, lacked visible arms, users highlighted the importance of features that supported full-body engagement, such as areas to rest the head or wrap arms around. This feedback reflects a functional requirement unique to huggable interfaces: they must invite physical affection while remaining visually and socially unobtrusive.

Recasting our findings in light of the framework of mediated intimacy [

31], the preference for ambiguous, neutral shapes can be understood as reflecting the kind of open-ended emotional communication often found in mediated touch. Rather than prescribing fixed affective meanings, such designs invite users to project their own emotions, intentions, and presence, aligning with perspectives from emotional computing [

32] that emphasize technology’s role in supporting rather than determining affective expression. This design stance, favoring suggestive rather than definitive emotional cues, echoes the balance intimate technologies must strike between presence and distance, expressivity, and restraint, thereby supporting emotionally meaningful but socially appropriate mediated touch.

Designing emotionally expressive huggable interfaces such as HugBits requires more than technical functionality: it calls for a deep understanding of how users interpret and emotionally engage with interactive artifacts. As demonstrated in our review of the literature, there is no one-size-fits-all approach. This study does not aim to define a single ideal form, but rather illustrates a methodology for exploring aesthetic preferences through the lens of personality and user-centered design. The approach developed here can be adapted by researchers and designers working on emotionally interactive systems, particularly during the early design phases, when user feedback can shape the visual and functional direction. Although facial features were generally unpopular among our adult participants, they may be more acceptable or even preferred by younger audiences, suggesting promising directions for age-specific personalization [

33,

34]. Ultimately, the design of huggable communication devices must balance emotional expressiveness, social appropriateness, and physical usability. To support meaningful long-term use, these technologies must be intuitive, personal resonant, and seamlessly integrated into the daily lives of users, not as replacements for human interaction, but as complementary tools that foster connection, comfort, and emotional well-being over distance.

6.1. Design Guidelines for Huggable Communication Interfaces

After completing this exploration, we now turn to the next stage of the HugBits design, guided by our goal of creating meaningful, emotionally resonant technologies that bring people together through mediated hugs. As illustrated in

Figure 12, the findings of this study already point to future iterations: designs that are hug-suggestive but remain object-like, balancing emotional expressiveness with social acceptability. To conclude, we summarize our key design guidelines for huggable communication interfaces, derived from both quantitative results and qualitative feedback:

Adopt neutral, object-like forms rather than anthropomorphic shapes. Facial features or human-like bodies were rarely favored among adult participants, who described them as childish, uncanny, or socially awkward. Instead, simple abstract forms that subtly convey the function of mediating hugs without mimicking human identity were consistently preferred.

Provide ergonomic affordances for hugging. Participants repeatedly emphasized the importance of comfort and functional support for full-body engagement, such as dedicated areas to rest the head or wrap the arms. These features directly influence both usability and emotional resonance.

Ensure aesthetic appropriateness in shared environments. Communication devices are inherently social; however, overly anthropomorphic or toy-like designs risk attracting unwanted attention or appearing out of place in public or semi-public contexts. Future designs should maintain discreet, socially acceptable aesthetics while signaling emotional warmth.

Maintain emotional subtlety to avoid over-signaling intimacy. Findings suggest that emotionally supportive devices are most acceptable when they complement rather than replace human connection. Subtle cues. through material feeling, haptic feedback, or embodied interaction, may foster intimacy without making users uncomfortable.

Account for diversity in culture, age, and sensory preferences. The present study involved a middle-aged, culturally homogeneous sample. Future work should incorporate age- and cross-cultural stratified perspectives to ensure that designs resonate across diverse user groups and interaction contexts.

Integrate multisensory feedback beyond visual appearance. Because this study relied on static images, participants could not evaluate tactile qualities or dynamic feedback. Future prototypes should combine haptic, visual, and auditory channels to support richer, embodied emotional interactions.

Looking ahead, we envision huggable communication technologies that bridge the space between communication media and comfort agents. Users’ preferences for form and expressiveness appear to depend on the system’s perceived agency: neutral, cushion-like designs feel appropriate for mediating connection between people, while more companion-like forms suit devices that provide emotional comfort directly. Yet these roles are not mutually exclusive. Emerging designs increasingly blend both functions—offering mediated interaction enriched with gentle, autonomous feedback. Ultimately, CMC interfaces and comfort robots share the same goal of enhancing emotional well-being but pursue it through different means. Recognizing this continuum can guide the creation of hybrid huggable interfaces that balance neutrality and expressiveness, enabling emotionally meaningful yet socially appropriate communication.

6.2. Limitations and Future Directions

This study has several limitations that should be considered when interpreting the findings. First, although huggable interfaces are inherently physical, we employed an image-based online survey to efficiently explore design variables such as shape, anthropomorphism, and comfort. Although this approach provided meaningful insights, it necessarily lacked embodied interaction; participants could not experience the tactile qualities—softness, weight, and texture—that are central to huggable communication devices. Insights from embodiment theories [

35] emphasize that emotional experiences emerge through dynamic bodily engagement rather than visual perception alone. Therefore, future research should incorporate in-person evaluations with functional prototypes to examine how sensorimotor interactions—hugging pressure, posture, and temporal synchrony—jointly shape emotional meaning and user experience.

Second, the cultural and demographic composition of the sample limits the generalizability of our results. Restricting recruitment to Polish participants minimized cultural variability and allowed us to isolate personality-based effects, but it also precluded examination of how cultural norms surrounding touch, anthropomorphism, and emotional expression shape user preferences. Likewise, the largest age subgroup comprised middle-aged adults, potentially biasing perceptions toward more socially reserved or utilitarian designs. Future studies should adopt cross-cultural and age-stratified designs to ensure that huggable interfaces resonate across diverse user groups.

Third, several methodological constraints warrant attention. The exploratory design workshop involved a small, homogeneous group, and no formal coding procedures or inter-rater reliability measures were applied. Similarly, our main survey focused on dominant personality traits and employed descriptive and chi-square analyses for interpretability with a modest sample size. These choices limited our ability to detect subtler relationships or interaction effects that involve personality, culture, age, and gender. Future research with larger and more diverse samples should incorporate multivariate and interaction modeling approaches to better capture how individual differences and contextual factors jointly shape user perceptions.

Finally, while the present findings highlight aesthetic and functional design preferences, hugging as a mediated interaction is essentially social and emotional. Future work should explore how design choices interact with social presence, intimacy, and emotional comfort during real-time-mediated communication, using longitudinal and ecologically valid methods to examine sustained engagement beyond initial impressions.