Investigations of Anomalies in Ship Movement During a Voyage

Abstract

1. Introduction

- (1)

- changes in speed, e.g., significant reduction or unexpected stopping;

- (2)

- changes in course;

- (3)

- deviations from recommended routes.

- (1)

- speed reduction for purposes such as:

- embarking or disembarking a pilot;

- executing a collision-avoidance action;

- maintaining a reduced speed under restricted visibility conditions;

- (2)

- deviation from the recommended route in order to:

- take on fuel (bunkering), receive supplies, or exchange crew;

- execute an anti-collision maneuver;

- intended action;

- due to propulsion failure;

- (3)

- deviation combined with speed reduction as a result of:

- equipment or engine failure;

- waiting for a pilot or port entry clearance.

1.1. Related Work—State of the Art

1.2. Research Gap

2. Materials and Methods

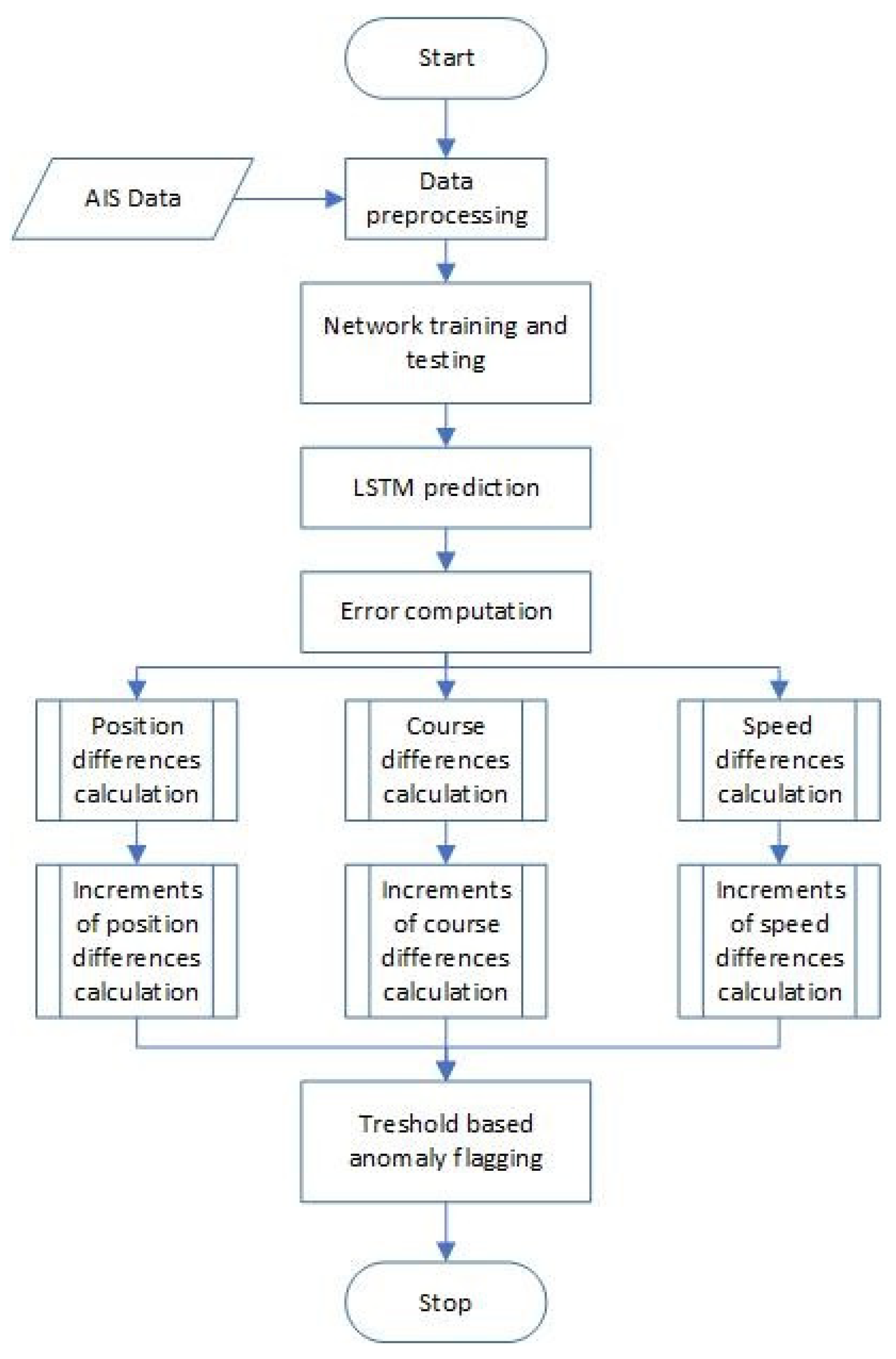

- (1)

- AIS data preprocessing and temporal alignment;

- (2)

- Network training and testing;

- (3)

- LSTM-based trajectory prediction for the next timesteps;

- (4)

- Computation of prediction errors for position, COG, and SOG;

- (5)

- Threshold-based classification of anomalies.

2.1. AIS Data

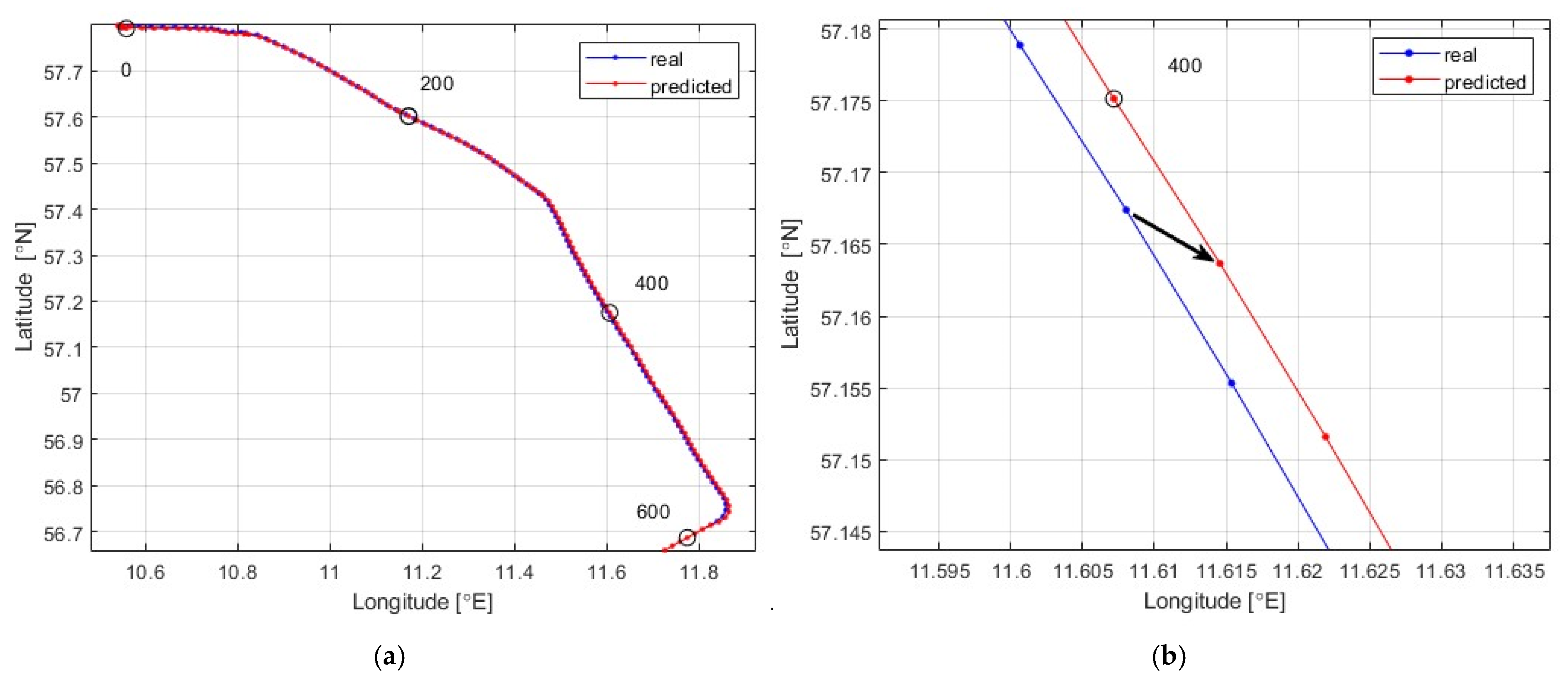

2.2. LSTM-Based Trajectory Prediction Model

2.2.1. Data Preparation and Feature Construction

2.2.2. LSTM Model Architecture and Training

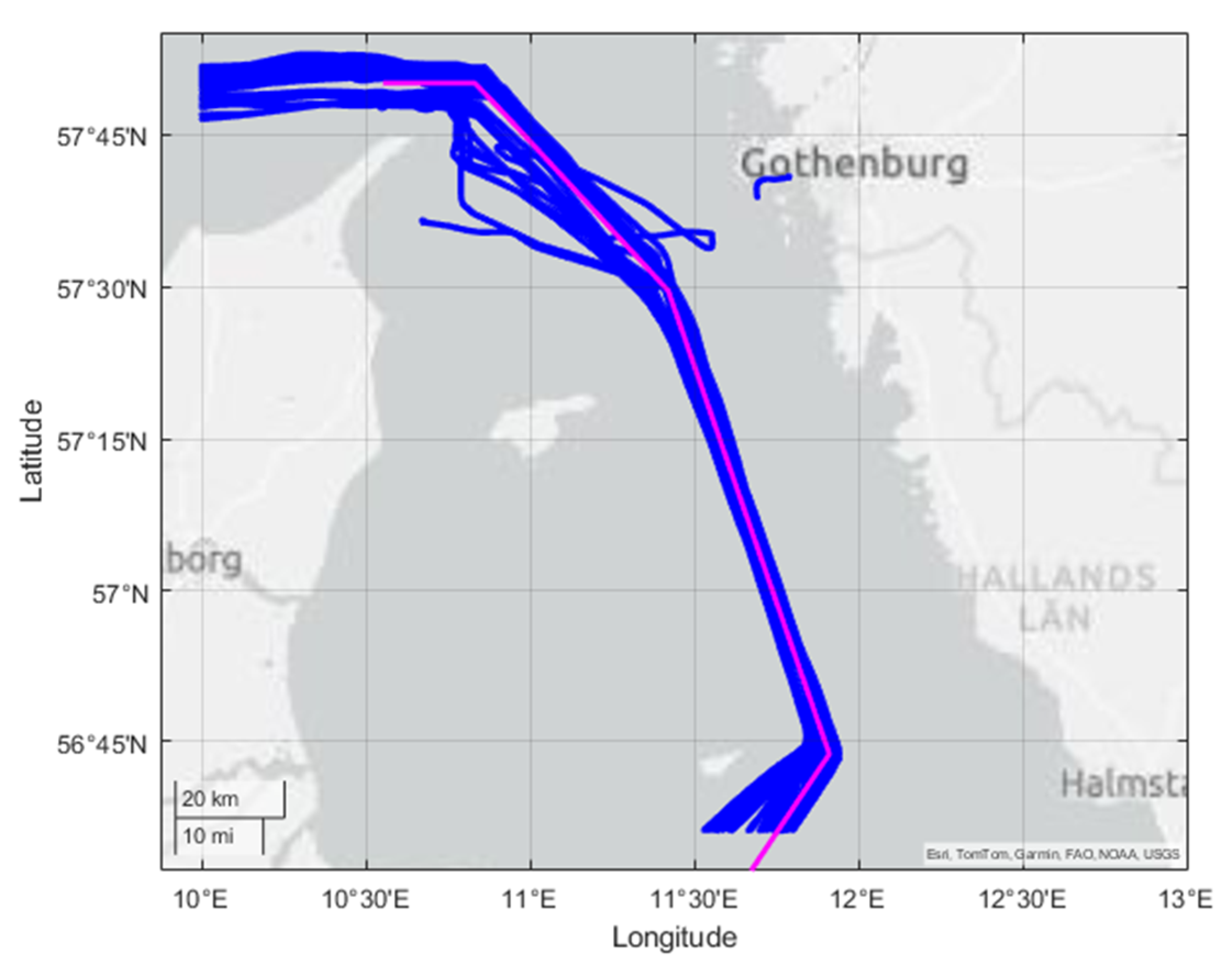

2.3. Area of Research

2.4. Data Preparation and Selection

- Route T and DW (Deep Water Route) via the Kattegat, Skagerrak, Great Belt, and Langeland Belt, with a minimum draft of 12 m (maximum approximately 15 m);

- Route H, with a draft of up to 10 m;

- Route S, with a draft of up to 7.7 m.

3. Research

- (1)

- selection of the study area and the group of analyzed vessels;

- (2)

- acquisition and preliminary processing of AIS data (preprocessing);

- (3)

- development of an artificial neural network architecture for ship movement prediction and execution of the network training process;

- (4)

- definition and calculation of indicators for ship movement anomaly identification;

- (5)

- identification of anomalies in vessel movement based on the proposed indicators using the artificial neural network.

3.1. Assumptions

3.2. Anomaly Identification Process

- —the number of AIS messages recorded for the vessel,

- —the x-coordinate of the position of ship j at time i, ,

- —the y-coordinate of the position of ship j at time i, ,

- —the course over ground of ship j at time i, ,

- —the speed over ground of ship j at time i, .

- —the predicted state vector of ship j at time i,

- —the increments of the state vector of ship j at time i,

- —the prediction function for the increments of the ship’s state vector,

- —the length of the input data vector of the artificial neural network,

- —the predicted increment of the x-coordinate of ship j at time i, ,

- —the predicted increment of the y-coordinate of ship j at time i, ,

- —the predicted change in the course over ground of ship j at time i, ,

- —the predicted change in the speed over ground of ship j at time i, ,

- —the predicted x-coordinate of the position of ship j at time i, ,

- —the predicted y-coordinate of the position of ship j at time i, ,

- —the predicted course over ground of ship j at time i, ,

- —the predicted speed over ground of ship j at time i, ,

- —the predicted position x of ship j at time i, ,

- —the predicted position y of ship j at time i, .

- atan2d—four quadrant inverse tangent,

- ), ),—predicted vertical and horizontal components of

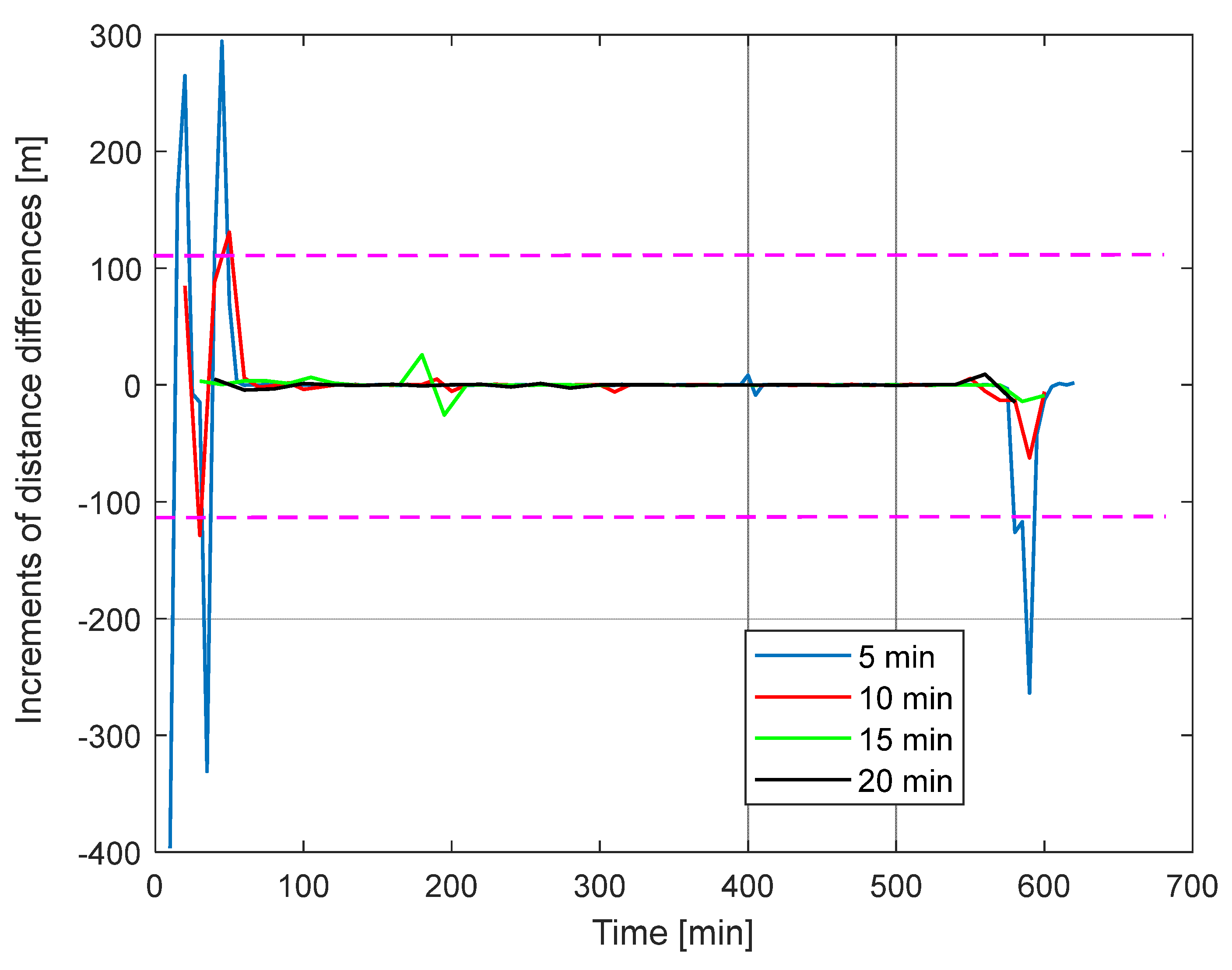

- position error > 0.5 L, where L—ship length;

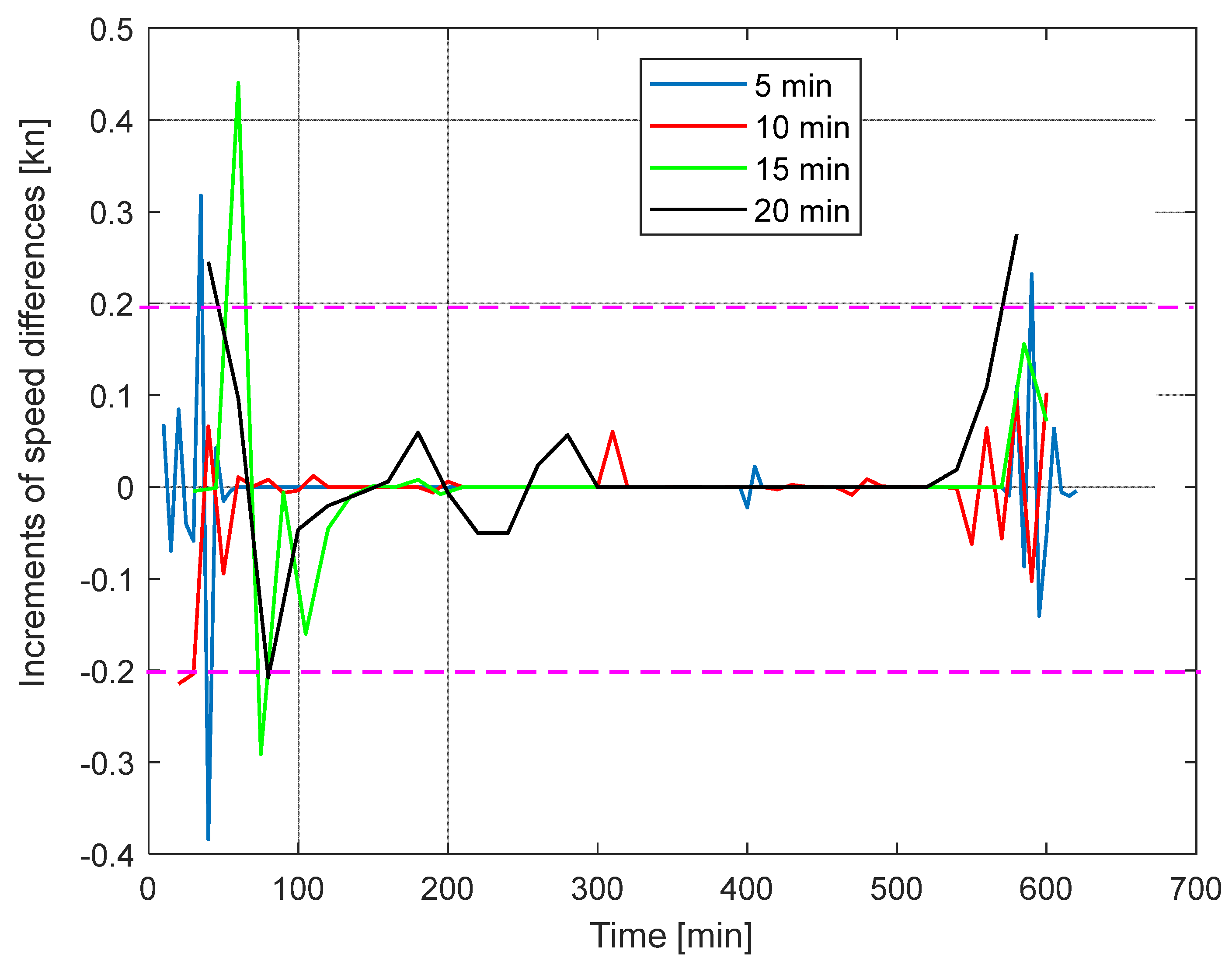

- speed deviation > 0.2 kn;

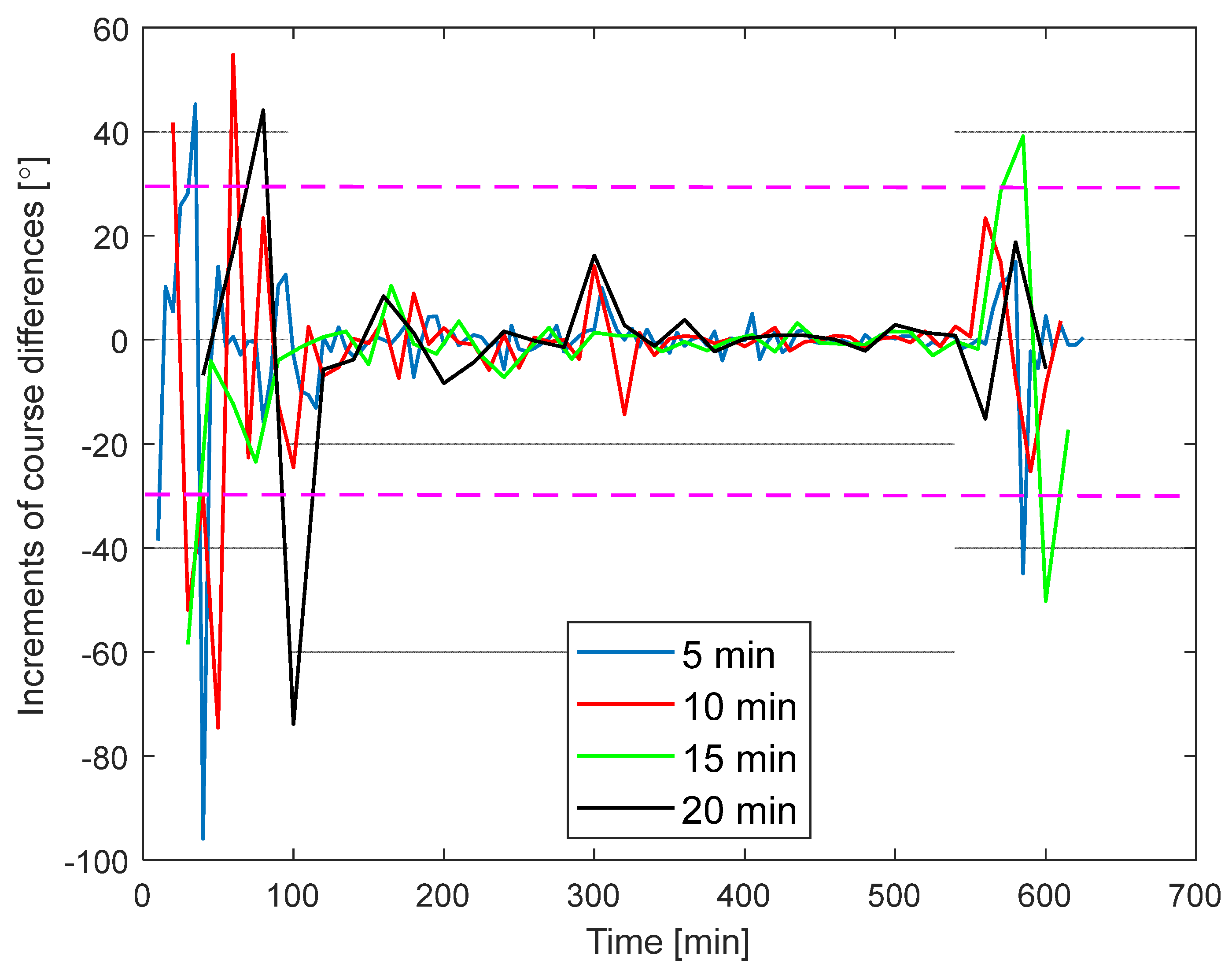

- course deviation > 30°.

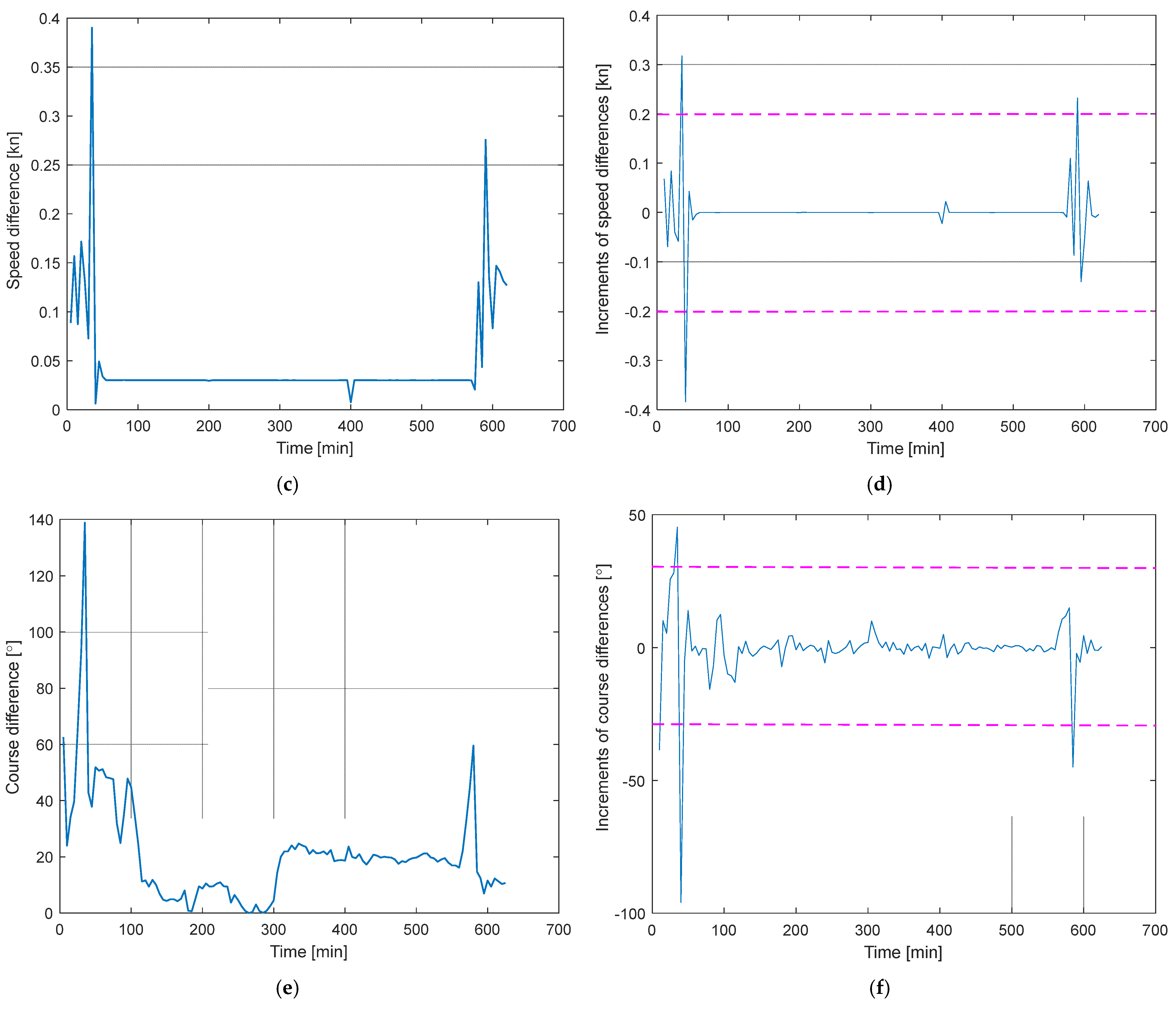

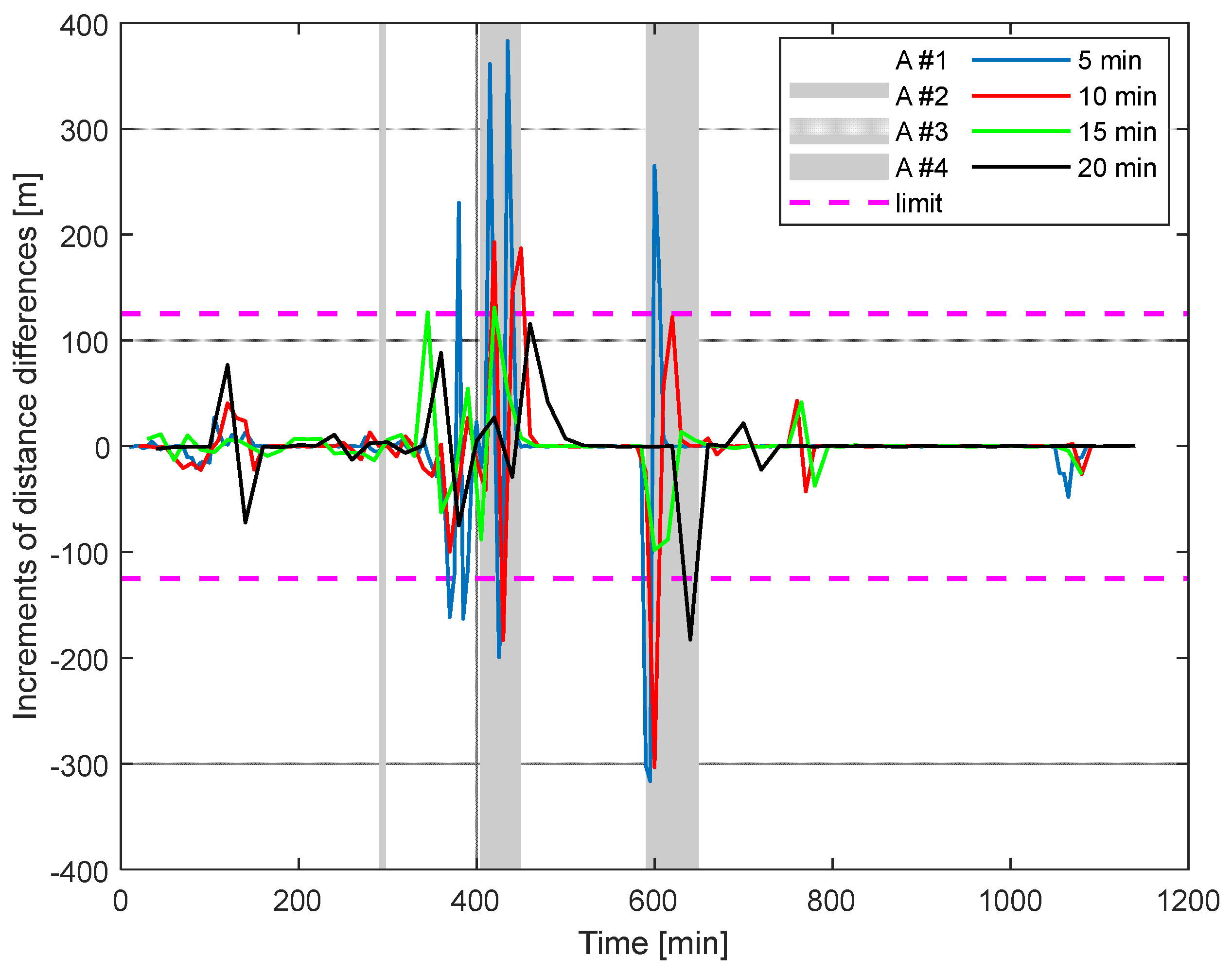

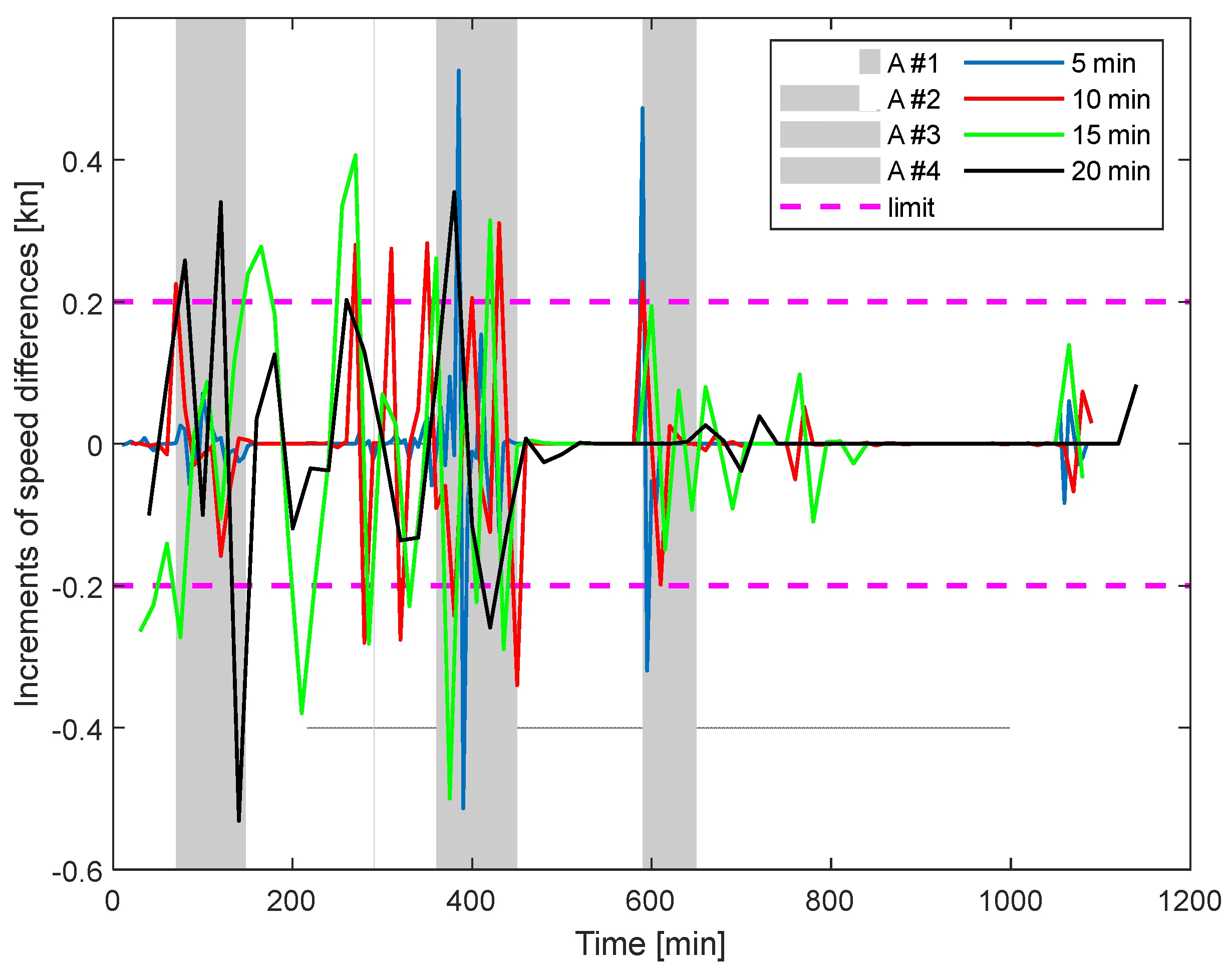

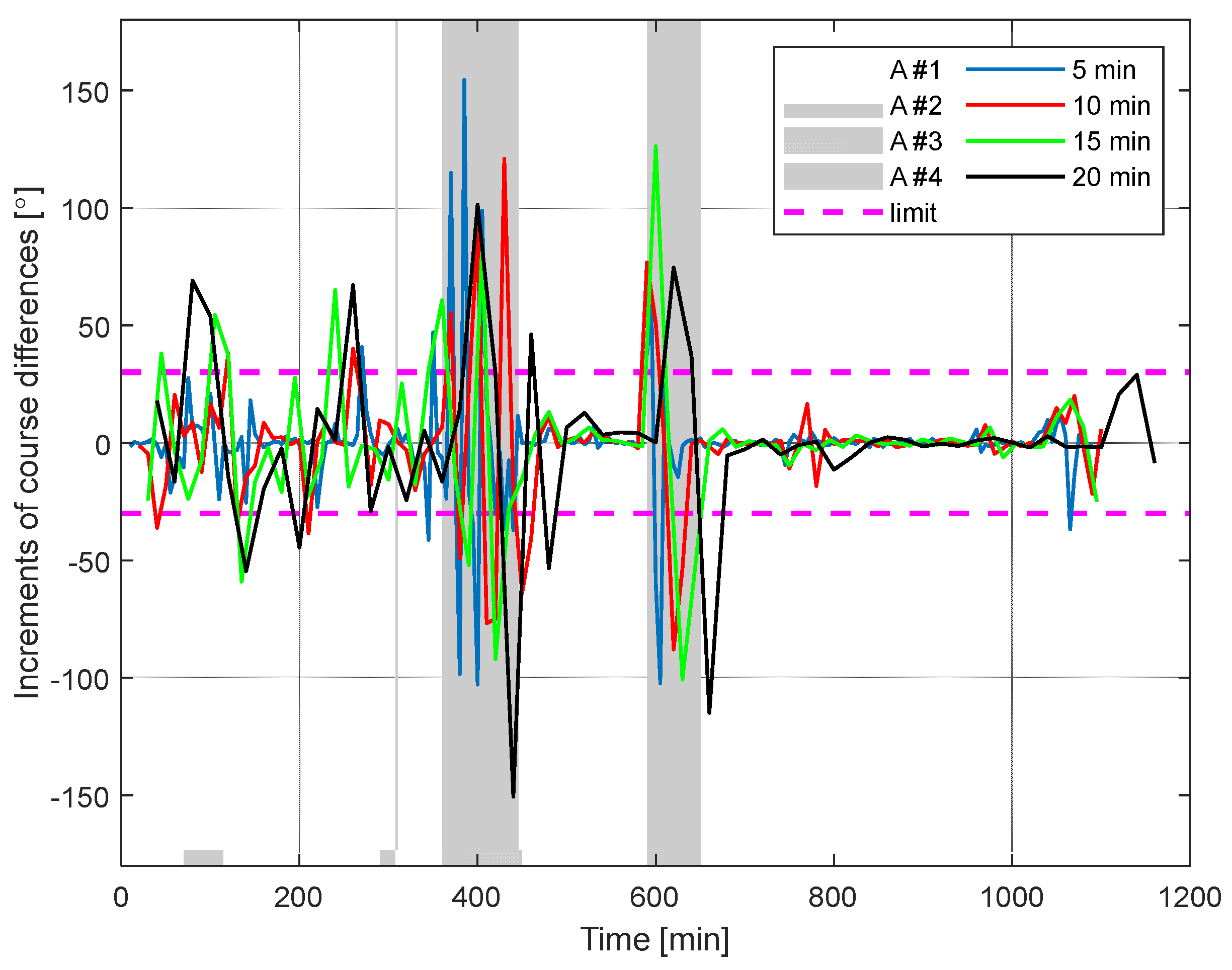

4. Results

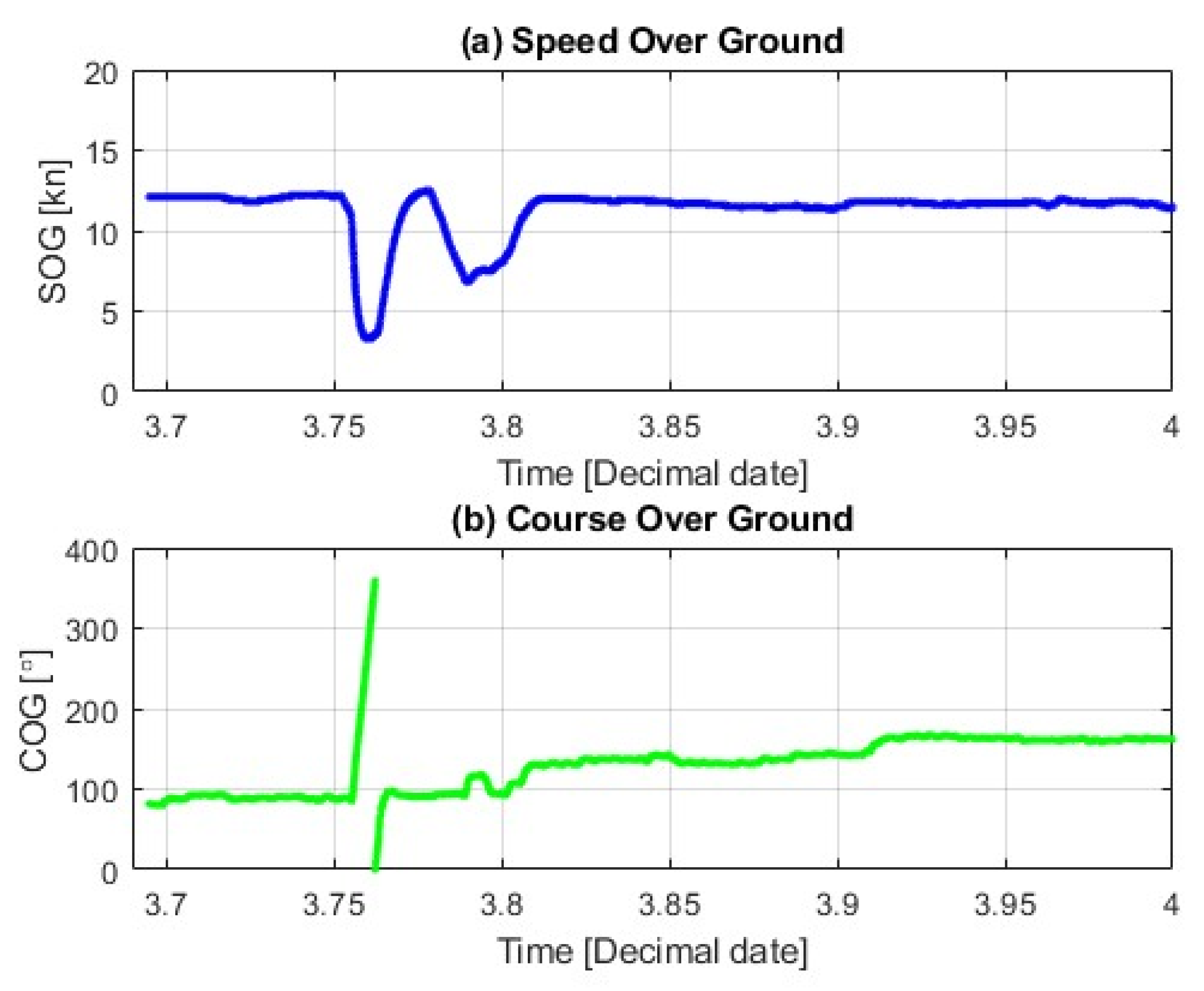

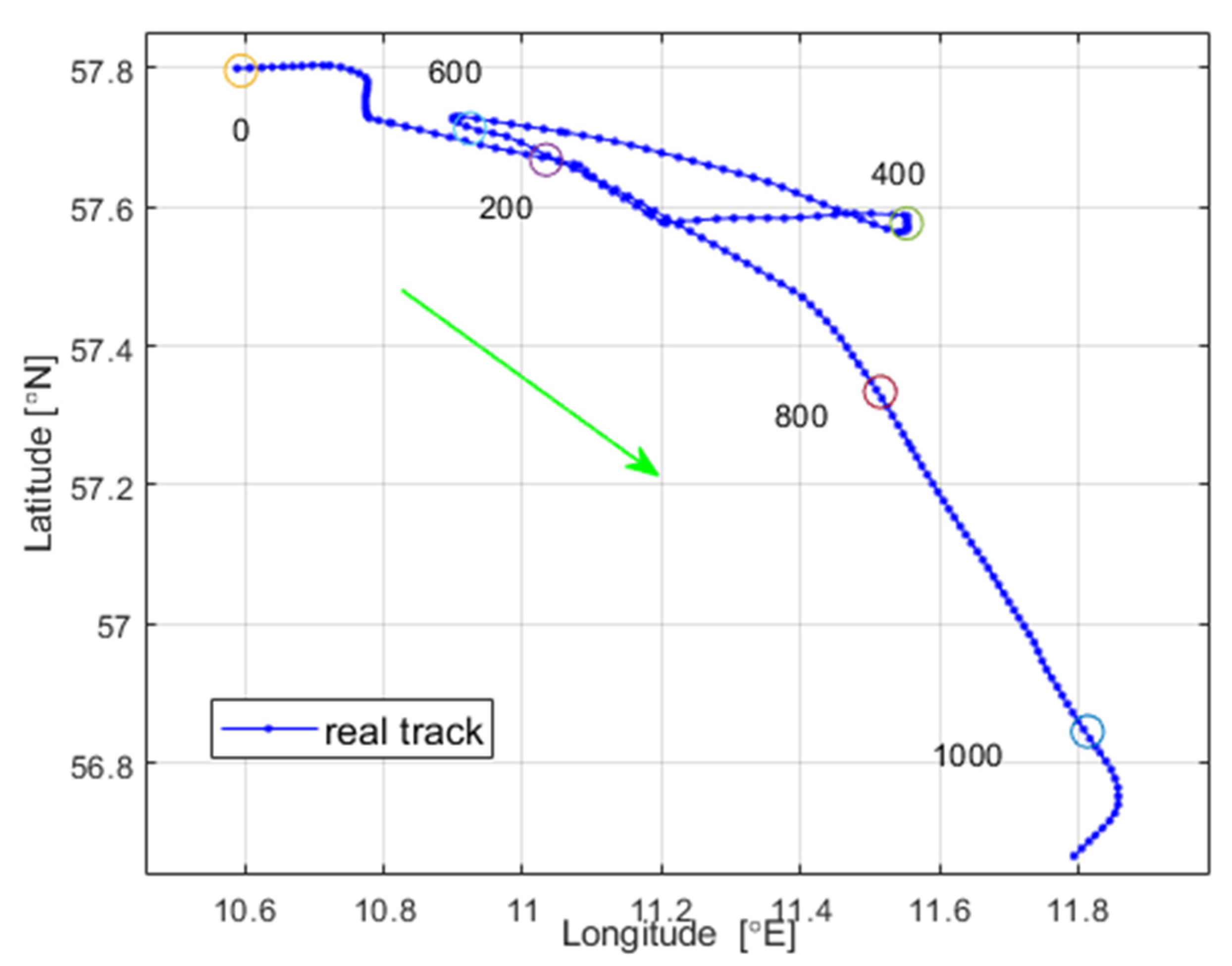

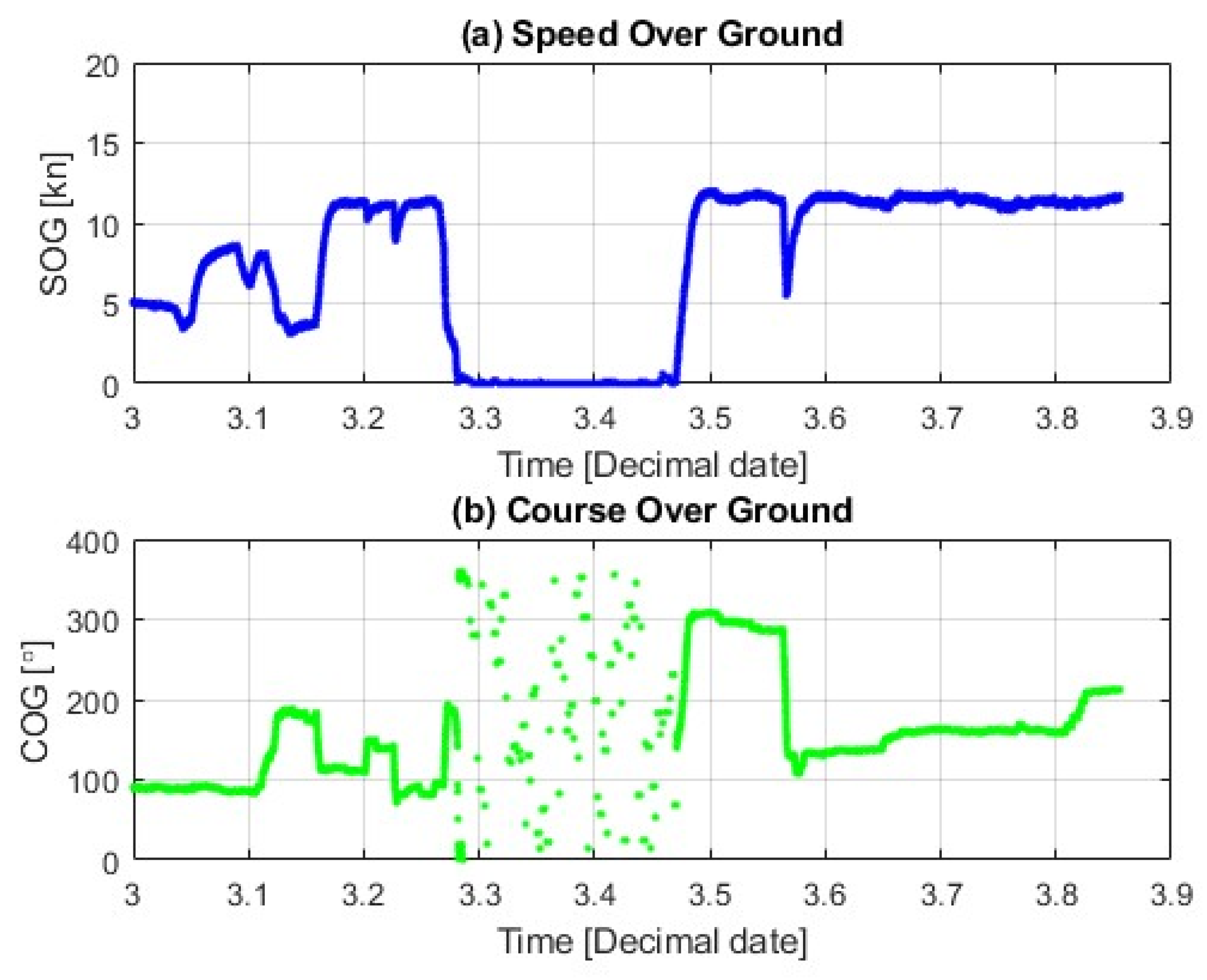

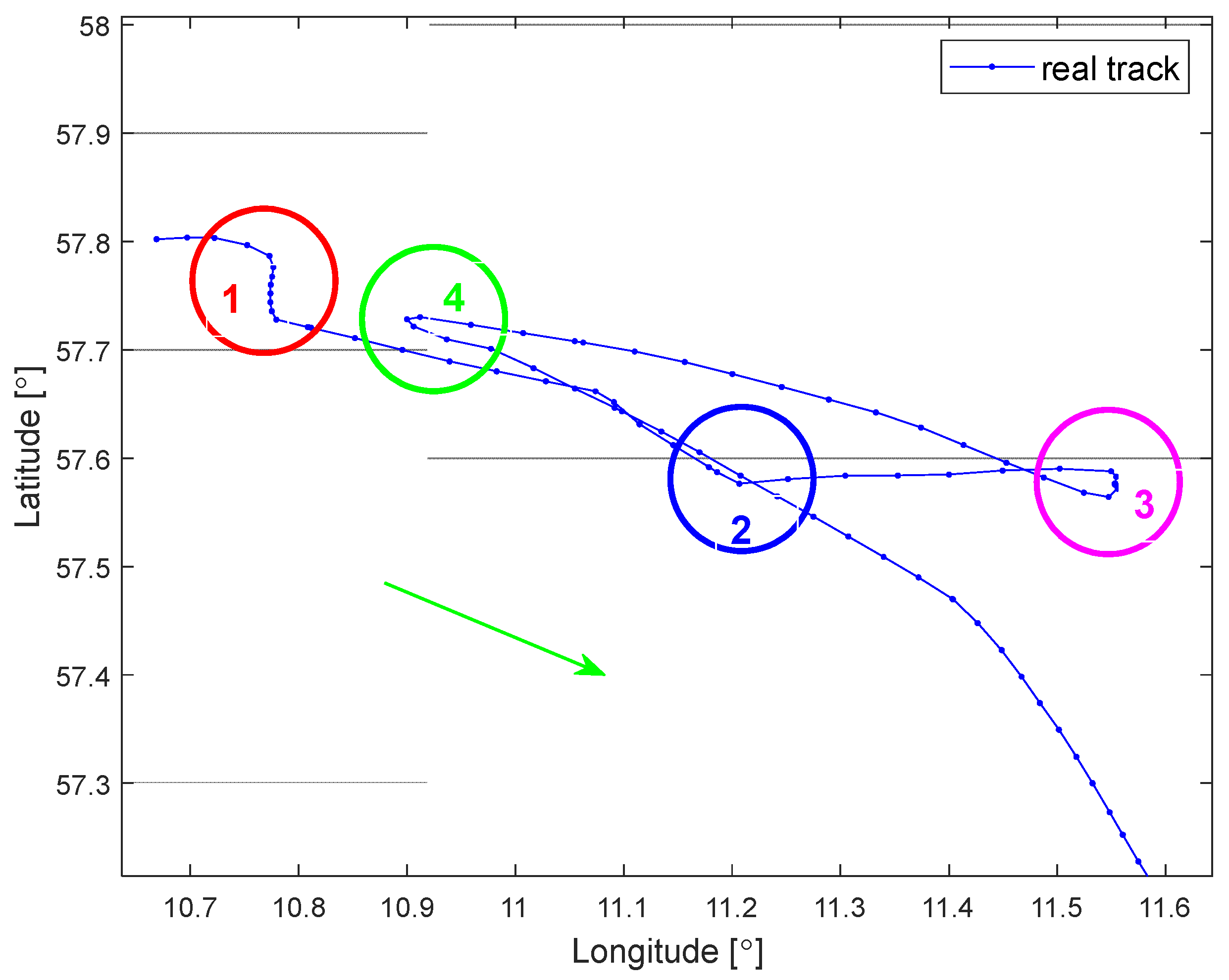

4.1. Case Study

- (1)

- a course alteration—anomaly #1;

- (2)

- a course alteration and deviation from the recommended route—anomaly #2;

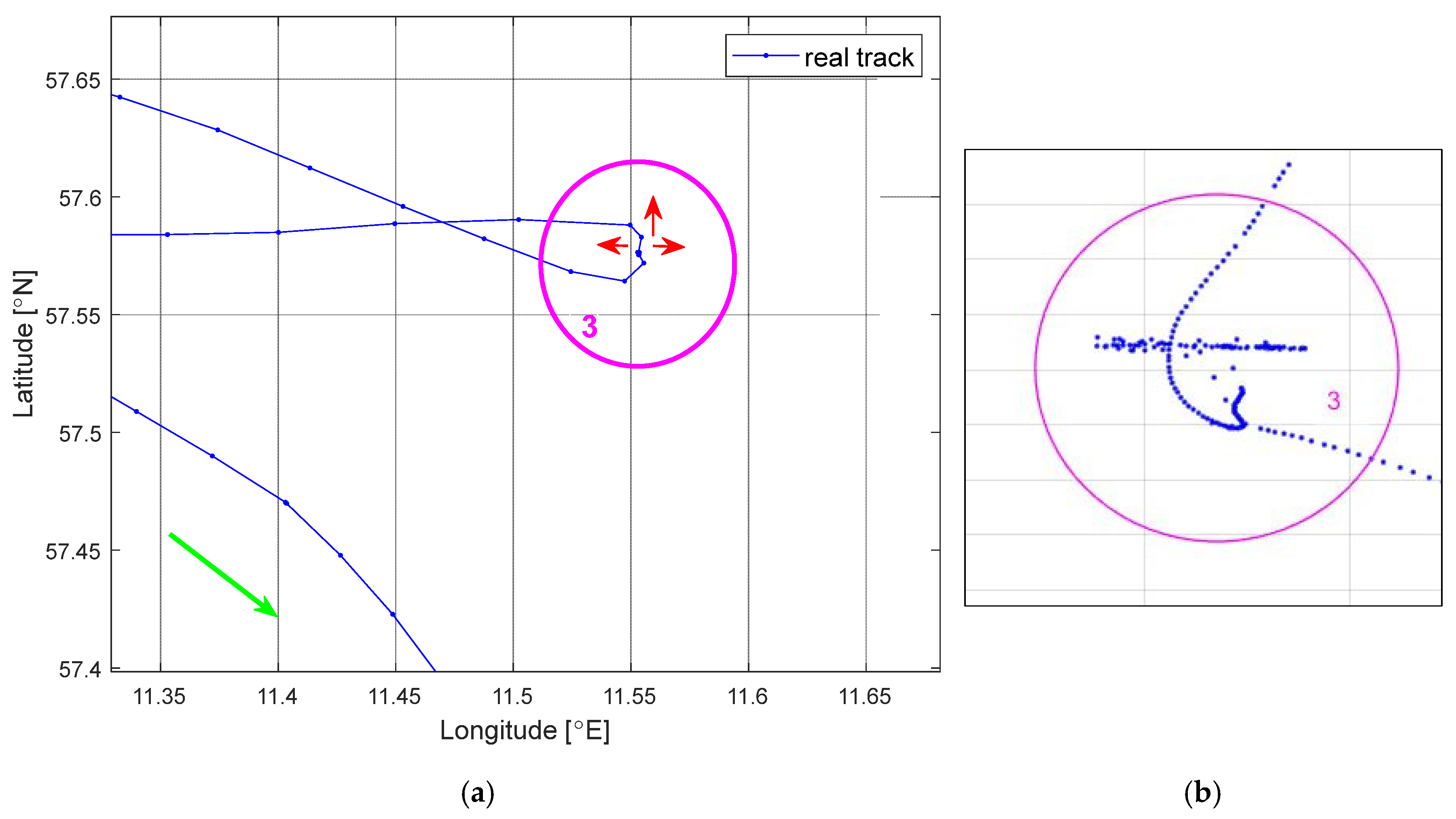

- (3)

- a decrease in speed and drifting stop—anomaly #3;

- (4)

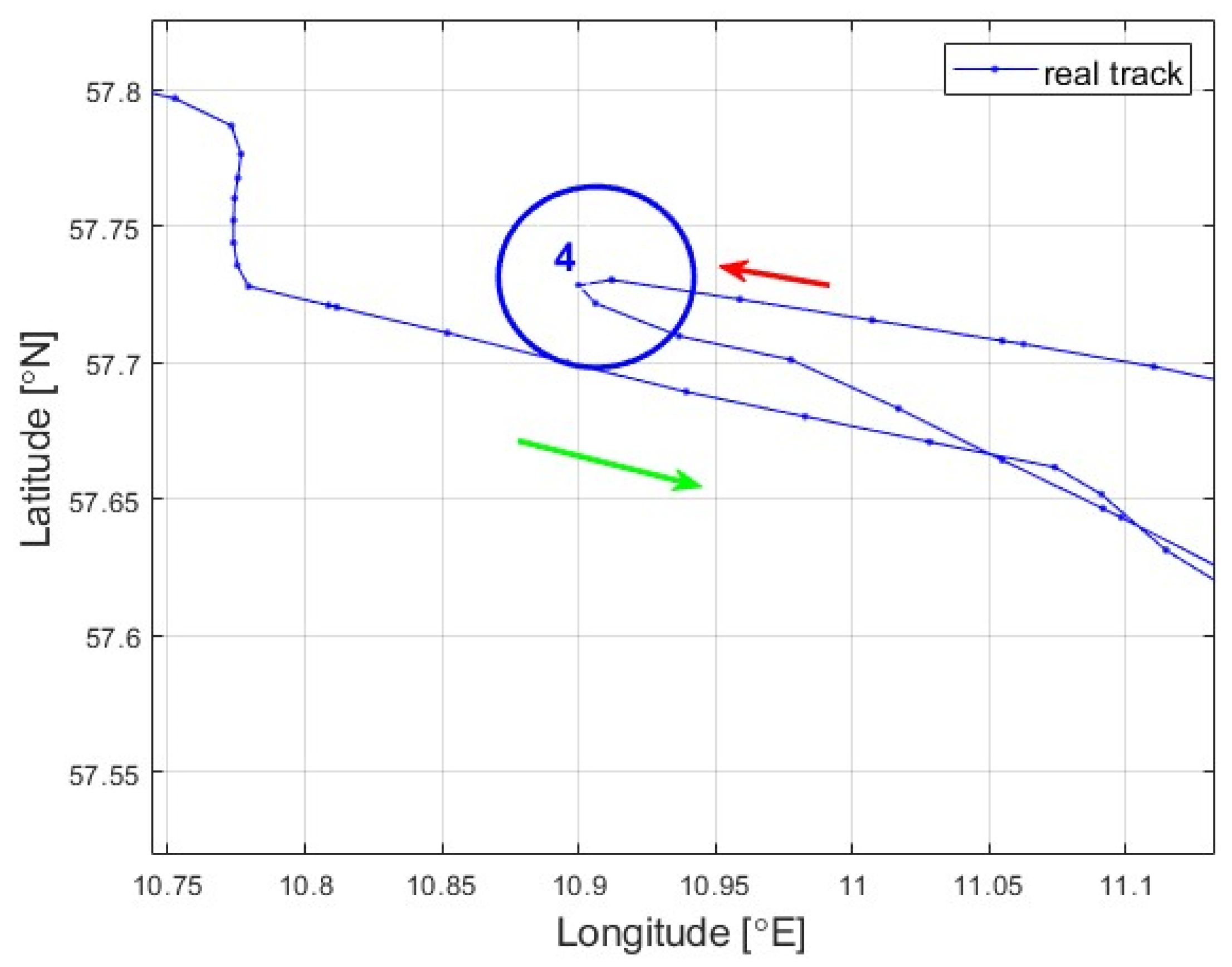

- a sudden 180° course change to return to the original trajectory—anomaly #4.

- anomaly #1: 70–150 min;

- anomaly #2: 290–310 min;

- anomaly #3: 360–450 min;

- anomaly #4: 590–650 min.

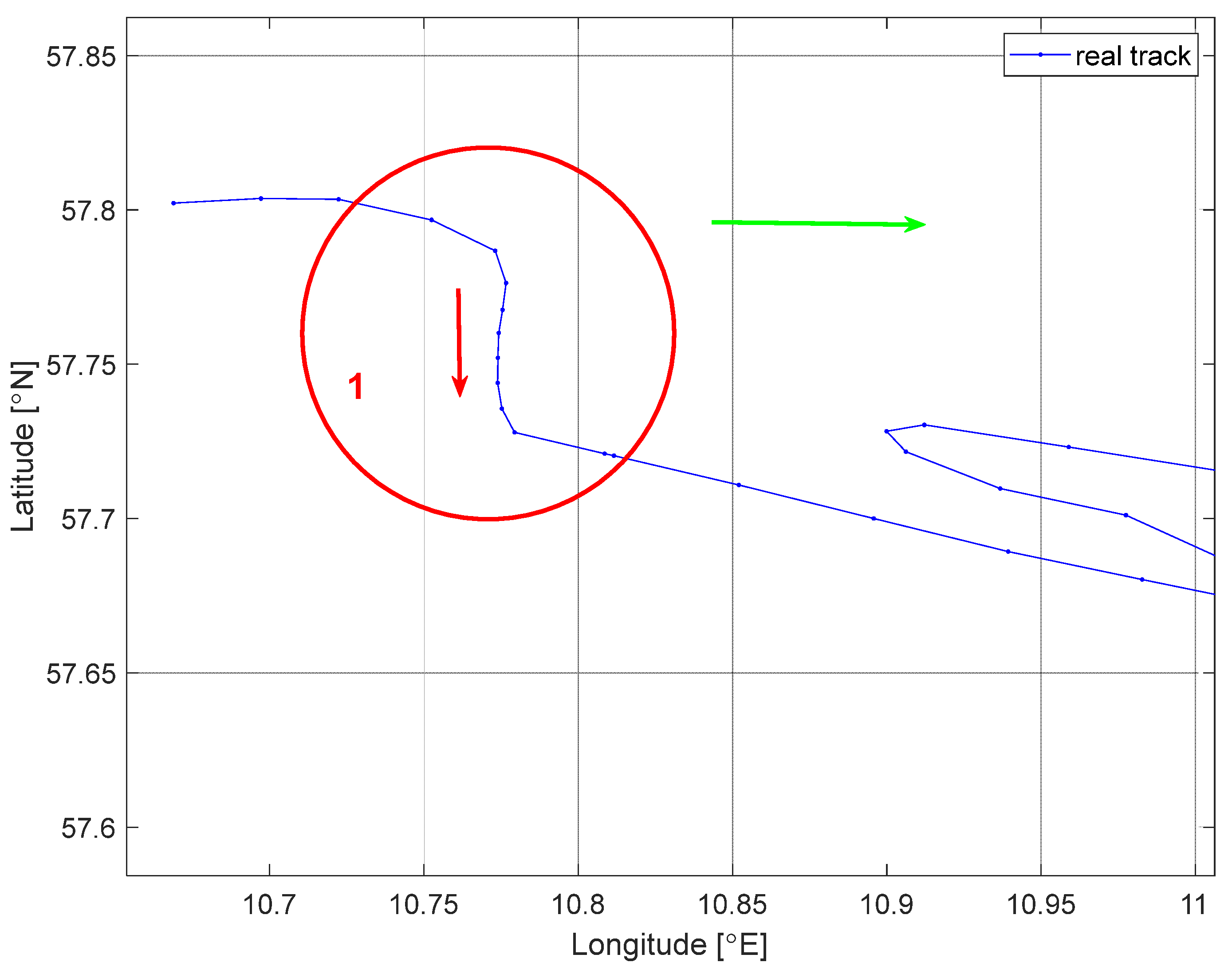

- Anomaly 1—Course alteration

- Anomaly 2—Course alteration and deviation from the recommended route

- Anomaly no. 3—decrease in speed and drifting stop

- Anomaly no. 4—sudden 180° course change

4.2. Analysis of Movement Processes

- anomaly #1 (70–150 min) for time steps of 10, 15, and 20 min;

- anomaly #2 (290–310 min) for time steps of 10 and 15 min;

- anomaly #3 (360–450 min) for all time steps;

- anomaly #4 (590–650 min) for time steps of 10 and 15 min.

- anomaly #1 (70–150 min) for time steps of 10, 15, and 20 min;

- anomaly #2 (290–310 min)—no anomalies detected;

- anomaly #3 (360–450 min) for all time steps;

- anomaly #4 (590–650 min) for all time steps.

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| A | Anomaly |

| AIS | Automatic Identification System |

| ANN | Artificial Neural Network |

| COG | Course Over Ground |

| IMO | International Maritime Organization |

| KN | Knot (ships’ speed unit [sea mile/hour]) |

| L | Length (here ship length) |

| LSTM | Long-short time memory |

| MMSI | Marine Mobile Service Identity |

| RNN | Recurrent neural network |

| SOG | Speed Over Ground |

References

- Capobianco, S.; Millefiori, L.M.; Forti, N.; Braca, P.; Willett, P. Deep Learning Methods for Vessel Trajectory Prediction Based on Recurrent Neural Networks. IEEE Trans. Aerosp. Electron. Syst. 2021, 57, 4329–4346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, C.; Zhang, Y. TriangularSORT: A Deep Learning Approach for Ship Wake Detection and Tracking. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2025, 13, 108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Liu, T. A Real-Time Tracking Approach for Moving Objects Based on an Integrated Algorithm of YOLOv7 and SORT. J. Circuits Syst. Comput. 2024, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yasir, M.; Liu, S.; Pirasteh, S.; Xu, M.; Sheng, H.; Wan, J.; de Figueiredo, F.A.; Aguilar, F.J.; Li, J. YOLOShipTracker: Tracking Ships in SAR Images Using Lightweight YOLOv8. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 2024, 134, 104137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yasir, M.; Shanwei, L.; Mingming, X.; Jianhua, W.; Hui, S.; Nazir, S.; Zhang, X.; Colak, A.T.I. YOLOv8-BYTE: Ship Tracking Algorithm Using Short-Time Sequence SAR Images for Disaster Response Leveraging GeoAI. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 2024, 133, 103771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Gao, M.; Shi, P.; Zeng, X.; Zhang, A. Target Ship Recognition and Tracking with Data Fusion Based on Bi-YOLO and OC-SORT Algorithms for Enhancing Ship Navigation Assistance. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2025, 13, 366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Ma, P.; Hu, Y.; Wang, X.; Hsieh, T.-H.; Han, B.; Wang, S. A MCKF-Based Cascade Vector Tracking Method Designed for Ship Navigation. Meas. Sci. Technol. 2024, 35, 046301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Liu, J.; Zhao, Y.; Luo, W.; Mei, K.; Wang, P.; Song, Y.; Li, X. A Reliable Unmanned Aerial Vehicle Multi-Ship Tracking Method. PLoS ONE 2025, 20, e0316933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shao, Z.; Yin, Y.; Lyu, H.; Guedes Soares, C. A Robust Method for Multi-Object Tracking in Autonomous Ship Navigation Systems. Ocean Eng. 2024, 11, 118560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damas, B.; Pessanha Santos, N.; Vieira, M. A Visual Tracking System for UAV Landing on Ships. In Proceedings of the 10th International Conference on Control, Decision and Information Technologies (CoDIT), Valletta, Malta, 1–4 July 2024; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Liu, T.; Liu, J.; Hu, X.; Wenhe, S. Trajectory Tracking for Autonomous Surface Ships Using Gaussian Process Regression and Model Predictive Control with BVS Strategy. J. Mar. Eng. Technol. 2024, 24, 179–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Chen, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Bian, S. AdapTrack: An Adaptive FairMOT Tracking Method Applicable to Marine Ship Targets. Eur. J. Artif. Intell. 2023, 36, 127–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Bai, W.; Zhang, W.; Zhao, Y. ADP-Based Adaptive Control of Ship Course Tracking System with Prescribed Performance. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part I J. Syst. Control Eng. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Wang, Y.; Wang, N.; Gao, X. An Enhanced SiamMask Network for Coastal Ship Tracking. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2021, 60, 5612011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Zhu, H.; Zhao, H.; Yang, D. Coastal Ship Tracking with Memory-Guided Perceptual Network. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 3150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilcev, D.S. Contemporary Architecture of the Satellite Global Ship Tracking (GST) Systems, Networks and Equipment. Aerosp. Syst. 2024, 7, 677–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Gao, P.; Wu, R.; Du, J. ESPO-Based Course-Tracking Control of Ships with Input Delay. Int. J. Control Autom. Syst. 2023, 21, 755–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, S.; Tougher, B.; Zetterlind, V. Estimating Speed Error of Commercial Radar Tracking to Inform Whale–Ship Strike Mitigation Efforts. Sensors 2025, 25, 1676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, Y.; Kim, K.; Baek, W.-K.; Ahn, J.-H.; Ryu, J.-H. Feasibility of Ship Detection and Tracking Using GOCI-II Images. Ocean Sci. J. 2024, 59, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.N.; Vijayakumar, A.; Balasubramaniyam, S.; Somayajula, A. Deep Reinforcement Learning for Ship Collision Avoidance and Path Tracking. In Proceedings of the ASME 2023 43rd International Conference on Ocean, Offshore and Arctic Engineering (OMAE2024), Singapore, 9–14 June 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Z.; Shao, J.; Nie, F.; Luo, Z.; Chen, C.; Xiao, L. Robust Online Learning Based on Siamese Network for Ship Tracking. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 7358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Setiawan, W.; Linawati, L.; Widyantara, I.M.; Wiharta, D.; Asri, S. Ship Trajectory Extraction Using Python Vessel Tracking Interpolation Method. PIKSEL Penelit. Ilmu Komput. Syst. Embed. Logic 2024, 12, 231–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, J.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, C. Tracking Moving Ships Using Distributed Acoustic Sensing Data. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 2025, 22, 7502605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wielgosz, M.; Malyszko, M. A Method for Early Identification of Vessels Potentially Threatening Critical Maritime Infrastructure. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 8716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rakhmanov, A.; Wiseman, Y. Compression of GNSS Data with the Aim of Speeding up Communication to Autonomous Vehicles. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 2165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Tu, P.; Zhao, Z.; Chen, X.Y. Incorporating Prior Knowledge of Collision Risk into Deep Learning Networks for Ship Trajectory Prediction in the Maritime Internet of Things Industry. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2025, 146, 110311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Wang, H.; Cui, F.; Liu, Y.; Liu, Z.; Dong, J. Research into Ship Trajectory Prediction Based on An Improved LSTM Network. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2023, 11, 1268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raj, N.; Kumar, P. Navigating the Future: A Comprehensive Review of Vessel Trajectory Prediction Techniques. Def. Sci. J. 2025, 75, 129–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seong, N.; Kim, J.; Lim, S. Graph-Based Anomaly Detection of Ship Movements Using AIS Trajectories. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2023, 11, 1956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Zhang, X.; Shu, Y.; Wang, C.; Guo, W.; Wang, J. Ship Anomalous Behavior Detection in Port Waterways Based on Text Similarity and Kernel Density Estimation. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2024, 12, 968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolsing, K.; Roepert, L.; Bauer, J.; Wehrle, K. Anomaly Detection in Maritime AIS Tracks. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2022, 10, 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, Y.; Hahn, A.; Valdez Banda, O.; Huang, Y. Data/Knowledge-Driven Behaviour Analysis for Maritime Traffic Surveillance. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2024, 12, 1799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez, J.P.; Irigoien, X.; Duarte, C.M.; Eguíluz, V.M. Identification of Suspicious Behavior through Anomalies in the Trajectories of Fishing Vessels. EPJ Data Sci. 2024, 13, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Yu, Q.; Yang, Z. Vessel Trajectory Prediction for Enhanced Maritime Safety Using a Hybrid GAT–LSTM Model. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2024, 12, 1351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evmides, N.; Michaelides, M.P.; Herodotou, H. Vessel Trajectory Prediction with Deep Learning: Temporal and Spatial Considerations. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2025, 13, 1439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaman, U.; Khan, J.; Lee, E.; Balobaid, A.S.; Aburasain, R.Y.; Kim, K. Enhancing Vessel Trajectories Prediction with AIS Data. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0310385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, H.; Yin, Y.; Shen, H. A Model for Vessel Trajectory Prediction Based on Long Short-Term Memory Network. J. Mar. Eng. Technol. 2019, 21, 136–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, Y.; Wang, T.; Lü, J.; Liu, K. TEMPO: Time-Evolving Multi-Period Observational Anomaly Detection Method for Space Probes. Chin. J. Aeronaut. 2025, 38, 103426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Q.; Xie, K.; Ye, W.; Zhou, T.; Xu, S. A Sparse Bayesian Learning Method for Moving Target Detection and Reconstruction. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2025, 74, 4505413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staudemeyer, R.C.; Morris, E.R. Understanding LSTM—A Tutorial into Long Short-Term Memory Recurrent Neural Networks. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1909.09586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gers, F.A.; Schmidhuber, J.; Cummins, F. Learning to Forget: Continual Prediction with LSTM. Neural Comput. 2000, 12, 2451–2471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greff, K.; Srivastava, R.K.; Koutník, J.; Steunebrink, B.R.; Schmidhuber, J. LSTM: A Search Space Odyssey. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 2016, 28, 2222–2232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Time | MMSI | Latitude | Longitude | Status | SOG [kn] | COG [deg] | Type | Length [m] | Draught [m] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 02:26:20 | 372713xxx | 55.54523 | 5.392 | 0 | 8.9 | 12.5 | 70 | 290 | 10.7 |

| 02:26:30 | 372713xxx | 55.54487 | 5.392 | 0 | 8.8 | 13 | 70 | 290 | 10.7 |

| 02:32:00 | 372713xxx | 55.55922 | 5.39235 | 0 | 8.9 | 12 | 70 | 290 | 10.7 |

| 02:32:10 | 372713xxx | 55.55962 | 5.392333 | 0 | 8.9 | 12 | 70 | 290 | 10.7 |

| 02:32:20 | 372713xxx | 55.56045 | 5.392317 | 0 | 8.9 | 12.5 | 70 | 290 | 10.7 |

| Anomalies | Increments of Differences | Time Step | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5 min | 10 min | 15 min | 20 min | ||

| A #1 | Dist. | - | - | - | - |

| SOG | - | x | x | x | |

| COG | - | x | x | x | |

| A #2 | Dist. | - | - | - | - |

| SOG | - | x | x | - | |

| COG | - | - | - | - | |

| A #3 | Dist. | x | x | x | - |

| SOG | x | x | x | x | |

| COG | x | x | x | x | |

| A #4 | Dist. | x | x | - | x |

| SOG | x | x | x | - | |

| COG | x | x | x | x | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wielgosz, M.; Pietrzykowski, Z.; Uriasz, J.; Góra, P. Investigations of Anomalies in Ship Movement During a Voyage. Electronics 2025, 14, 4733. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics14234733

Wielgosz M, Pietrzykowski Z, Uriasz J, Góra P. Investigations of Anomalies in Ship Movement During a Voyage. Electronics. 2025; 14(23):4733. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics14234733

Chicago/Turabian StyleWielgosz, Mirosław, Zbigniew Pietrzykowski, Janusz Uriasz, and Paulina Góra. 2025. "Investigations of Anomalies in Ship Movement During a Voyage" Electronics 14, no. 23: 4733. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics14234733

APA StyleWielgosz, M., Pietrzykowski, Z., Uriasz, J., & Góra, P. (2025). Investigations of Anomalies in Ship Movement During a Voyage. Electronics, 14(23), 4733. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics14234733