Explainable and Optimized Random Forest for Anomaly Detection in IoT Networks Using the RIME Metaheuristic

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

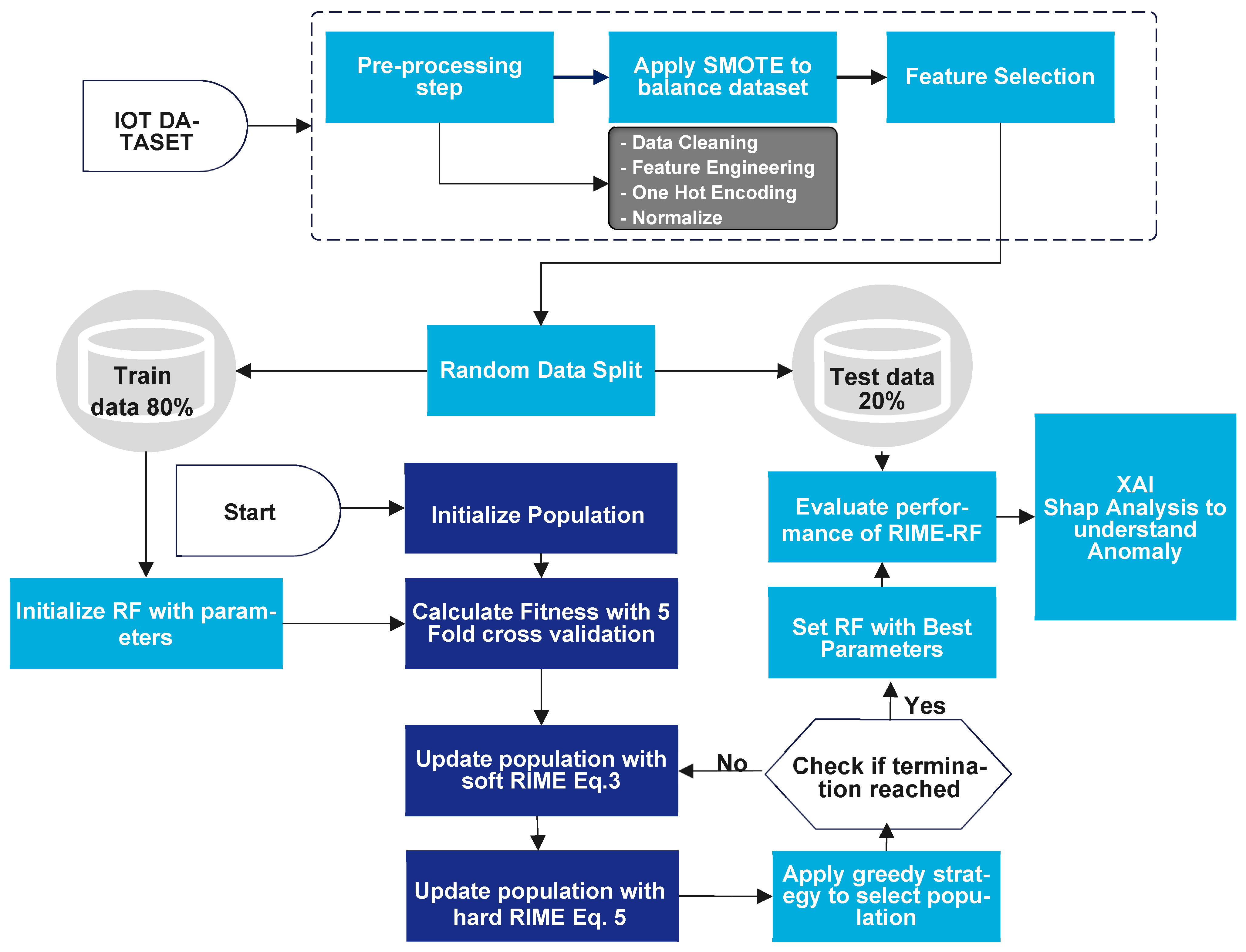

3. Methodology

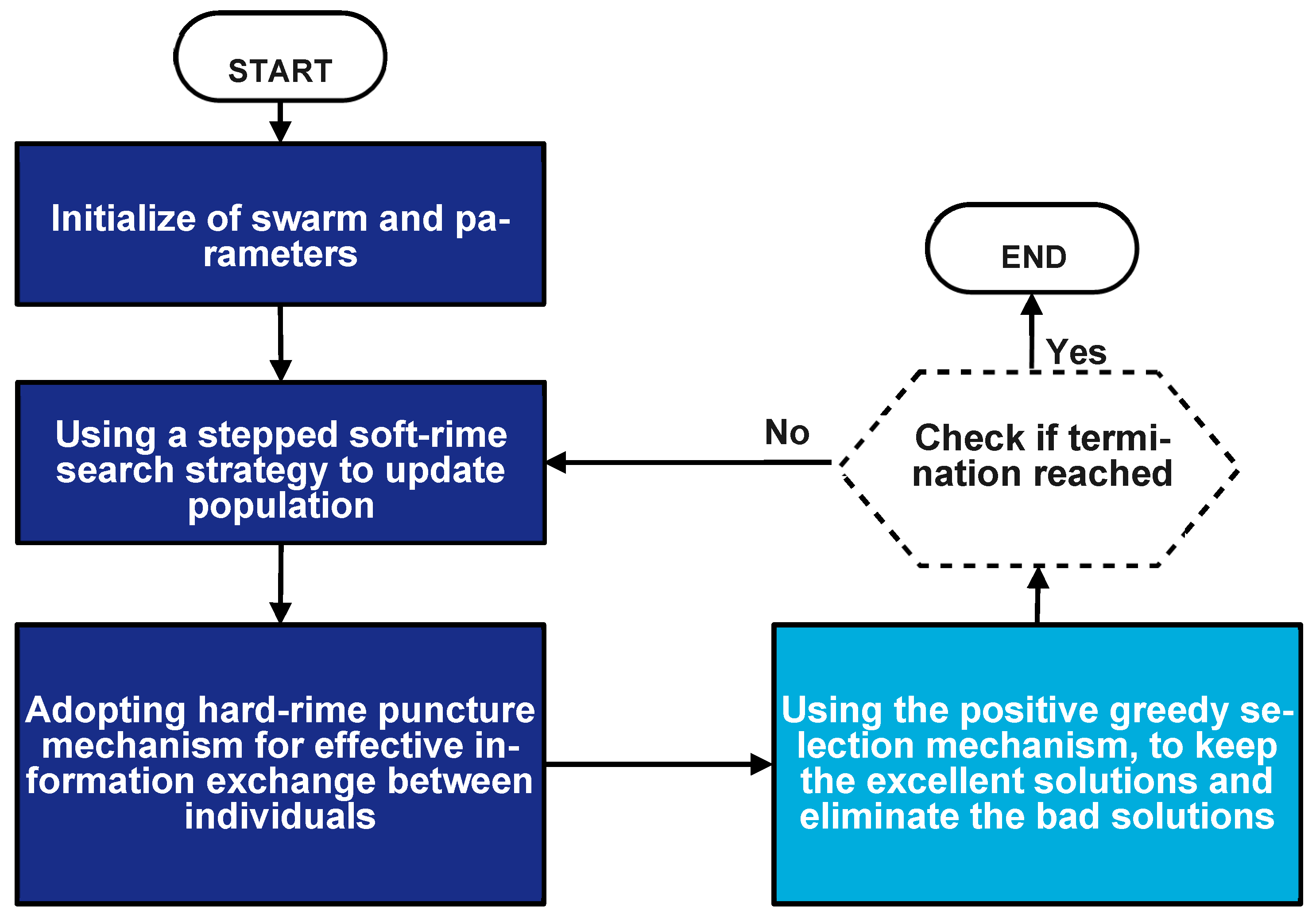

3.1. RIME Optimization Algorithm

- If (assuming a minimization problem), The new position is accepted: .

- Furthermore, if the fitness of the new position is superior to that of the current global best, , then the global best is updated: .

3.2. Random Forest

4. Hyperparameter Optimization of Random Forest Classifier Using RIME Algorithm

4.1. Data

4.1.1. Dataset Overview

4.1.2. Data Preprocessing

- Missing Value Treatment: Initial data quality assessment revealed the presence of null values across the dataset. These were addressed through complete case analysis, removing all instances containing missing values to maintain data integrity and avoid potential bias from imputation methods.

- Feature Engineering and Encoding: During the preprocessing stage, categorical variables underwent one-hot encoding transformation to convert string-based threat categories into numerical representations suitable for machine learning algorithms.

- Feature Scaling: To address the heterogeneous scales present across network traffic metrics, Min–Max normalization was applied to all features, transforming values to a standardized [0, 1] range. This normalization ensures that features with larger magnitudes do not dominate the learning process and facilitates convergence in gradient-based optimization algorithms.

- Dimensionality Reduction: Feature selection was performed using the SelectKBest algorithm with ANOVA F-statistic (f_classif) as the scoring function. The top 15 most discriminative features were retained based on their statistical significance in distinguishing between threat categories. This reduction strategy mitigates the curse of dimensionality while preserving the most informative attributes for classification.

- Class Imbalance Mitigation: The dataset exhibited significant class imbalance across different DDoS attack types. To address this challenge, the Synthetic Minority Over-sampling Technique (SMOTE) was employed when feasible, with automatic fallback to Random Over-Sampling (ROS) for classes with insufficient samples. The resampling strategy was determined dynamically based on the minimum class size, with SMOTE utilizing adaptive k-neighbors parameter selection to ensure valid synthetic sample generation.

- Data Partitioning: Following all preprocessing steps, the dataset was partitioned into training and testing subsets using stratified sampling with an 80:20 split ratio. The stratification ensured proportional representation of all threat categories in both subsets, maintaining the class distribution post-resampling. This comprehensive preprocessing approach ensures that the resulting dataset is suitable for training robust machine learning models while addressing common challenges in network security data, including high dimensionality, class imbalance, and scale heterogeneity.

4.2. Evaluation Metrics

- Accuracy: Accuracy quantifies the proportion of all classifications the model predicted correctly. It is defined as the ratio of correctly predicted samples to the total number of samples as defined in Equation (7).

- Precision: Precision measures the proportion of samples identified as a specific class by the model that are truly of that class; the formula is expressed in Equation (8).

- Recall (Sensitivity): Recall reflects the proportion of actual instances of a particular class that were correctly identified by the model. Its formula is given in Equation (9).

- F1 Score: The F1 score is the harmonic mean of precision and recall, providing a balanced measure that penalizes extreme values in either metric. The equation in Equation (10) defines the F1 score.

- Hamming Loss: Hamming Loss quantifies the fraction of incorrect labels to the total number of labels in multi-class classification. It is calculated as expressed in Equation (11).

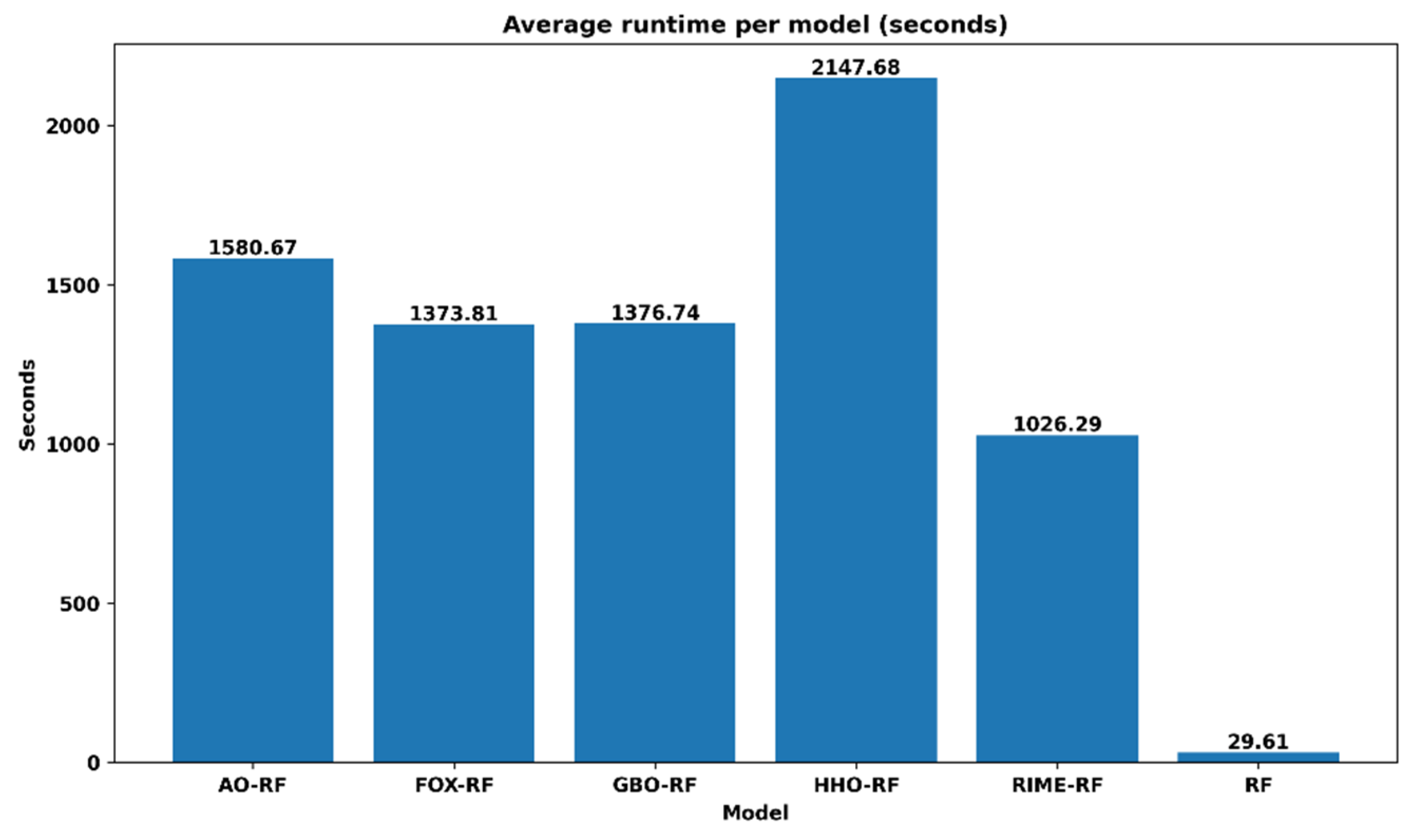

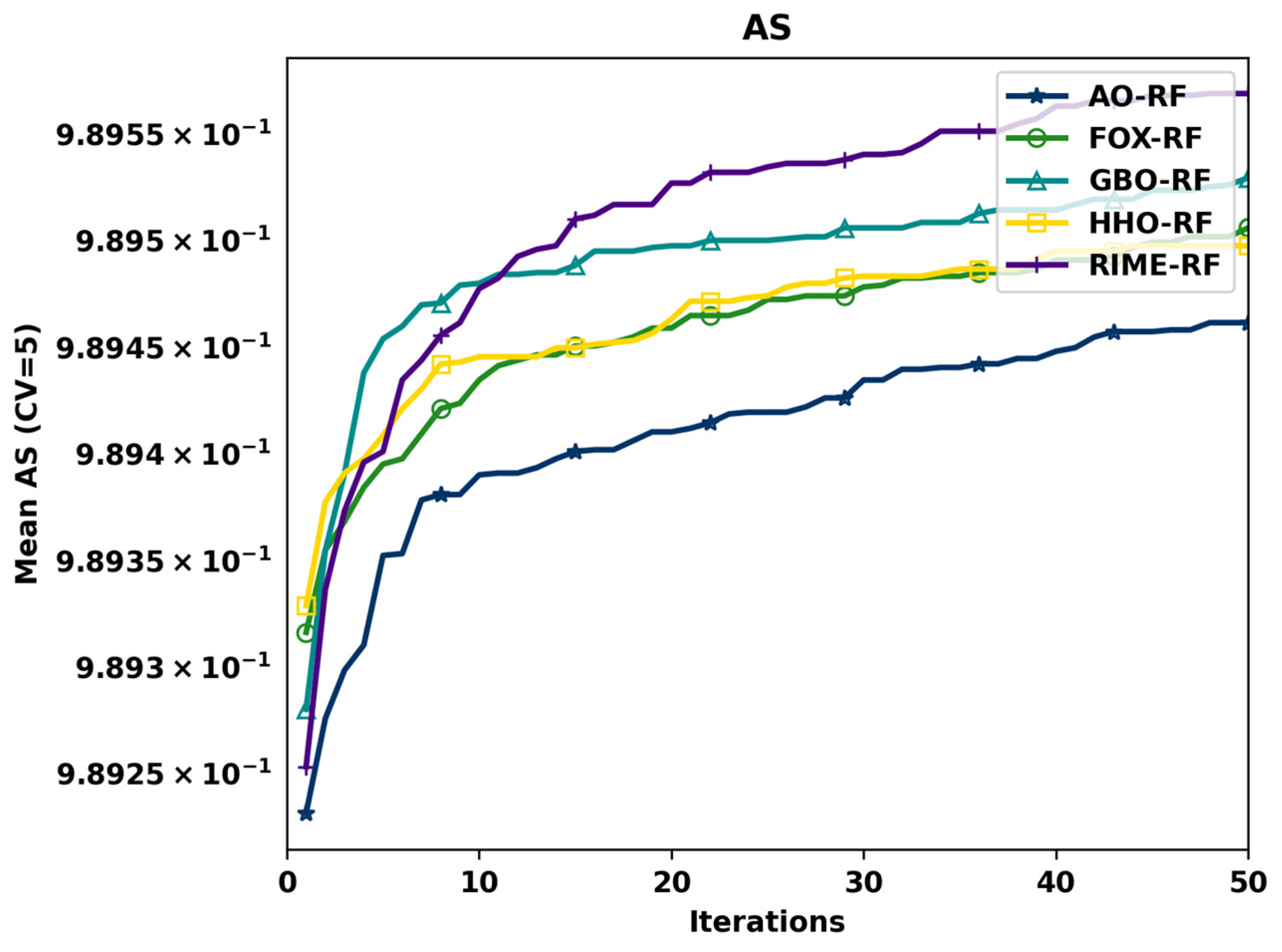

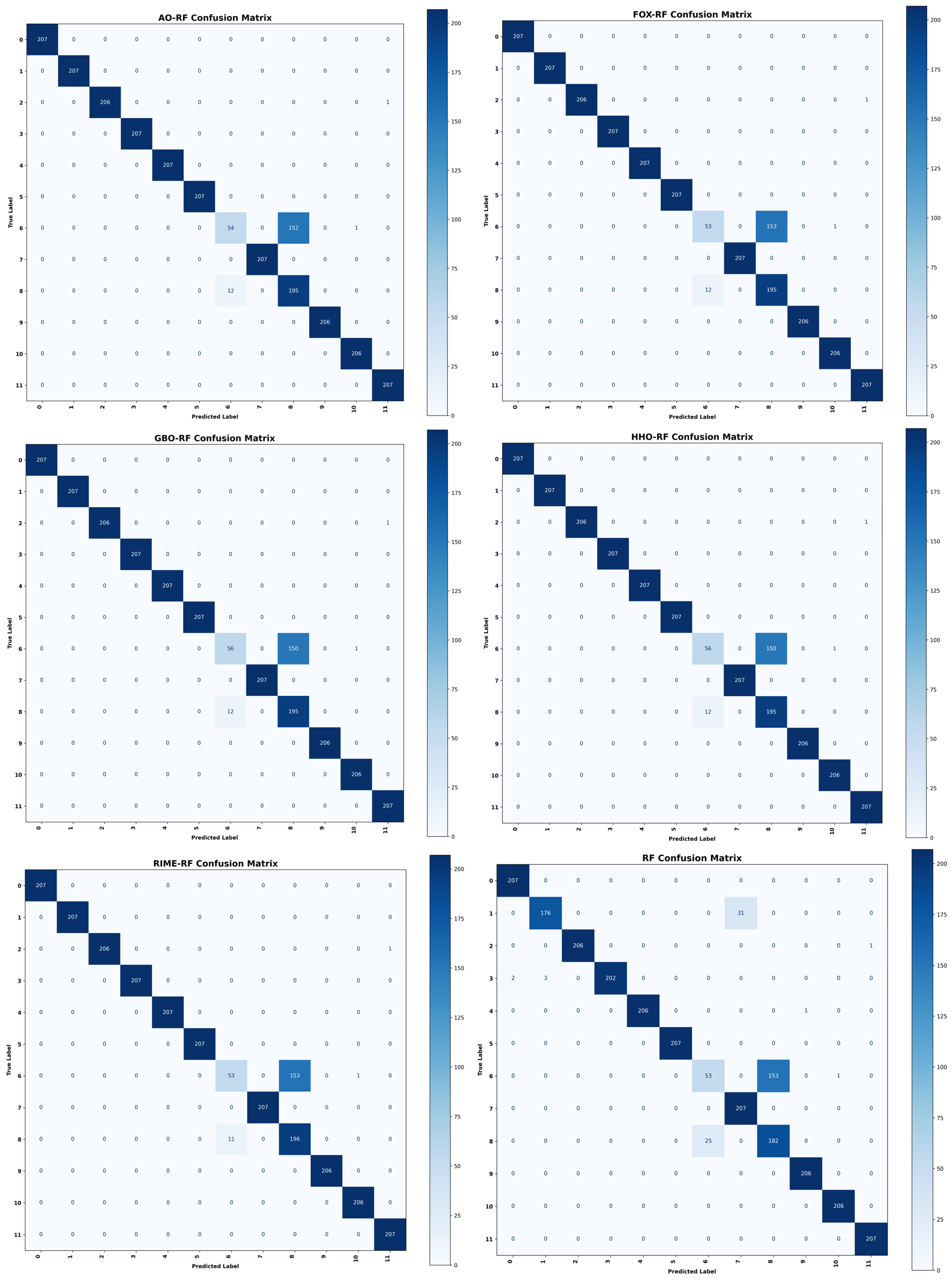

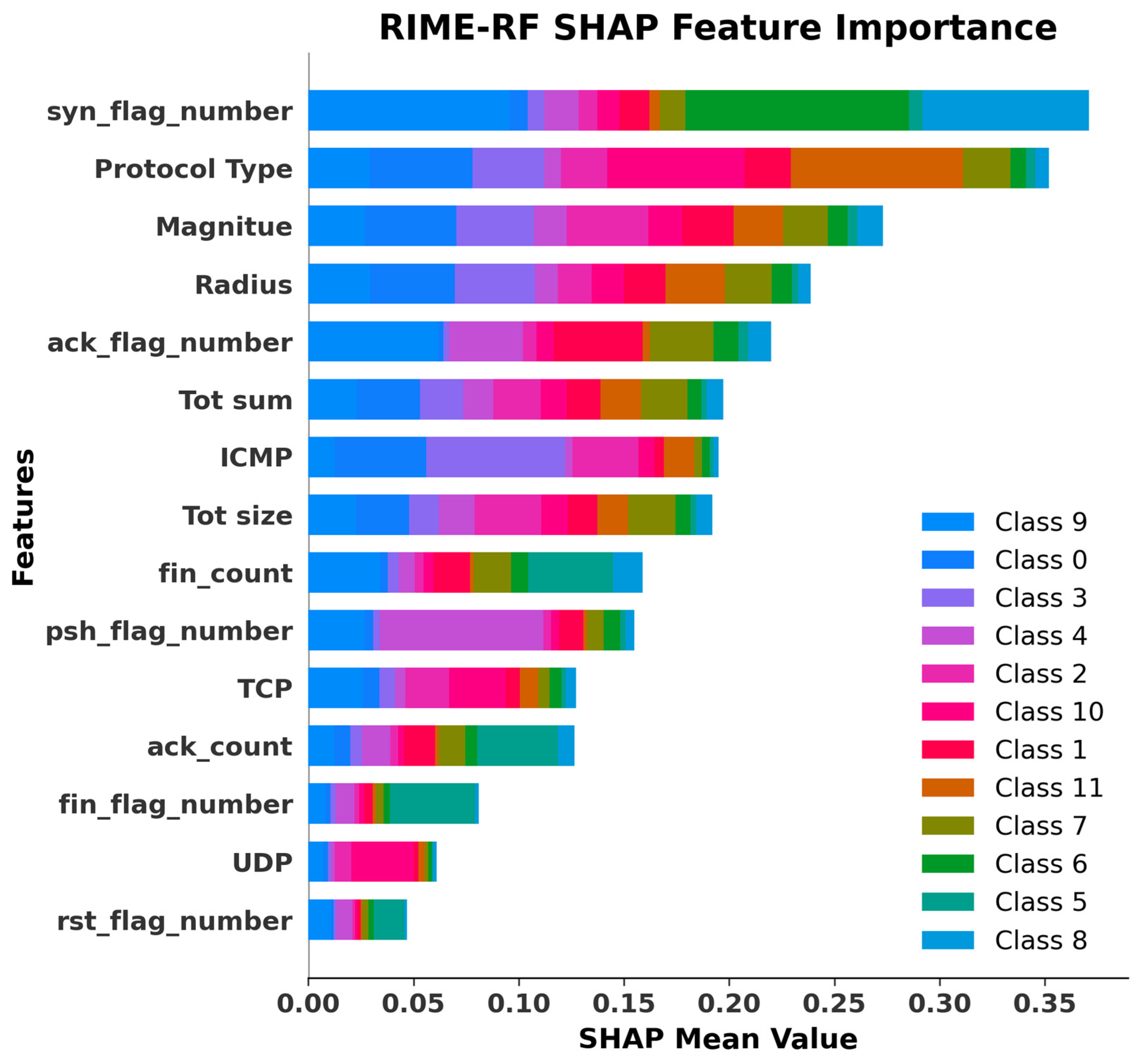

5. Results and Experiment

Performance Assessment and Results Presentation

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Aazam, M.; Zeadally, S.; Harras, K.A. Deploying Fog Computing in Industrial Internet of Things and Industry 4.0. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inform. 2018, 14, 4674–4682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Internet of Things Market (IoT) to Record CAGR of 24.3%, 2032. Available online: https://www.fortunebusinessinsights.com/press-release/internet-of-things-iot-market-9155?utm_source=chatgpt.com (accessed on 27 September 2025).

- Demertzi, V.; Demertzis, S.; Demertzis, K. An Overview of Cyber Threats, Attacks and Countermeasures on the Primary Domains of Smart Cities. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alahmadi, A.A.; Aljabri, M.; Alhaidari, F.; Alharthi, D.J.; Rayani, G.E.; Marghalani, L.A.; Alotaibi, O.B.; Bajandouh, S.A. DDoS Attack Detection in IoT-Based Networks Using Machine Learning Models: A Survey and Research Directions. Electronics 2023, 12, 3103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kottler, S. February 28th DDoS Incident Report. The GitHub Blog. Available online: https://github.blog/news-insights/company-news/ddos-incident-report/ (accessed on 27 September 2025).

- Orosz, P.; Nagy, B.; Varga, P. Real-Time Detection and Mitigation Strategies Newly Appearing for DDoS Profiles. Futur. Internet 2025, 17, 400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almadhor, A.; Altalbe, A.; Bouazzi, I.; Al Hejaili, A.; Kryvinska, N. Strengthening network DDOS attack detection in heterogeneous IoT environment with federated XAI learning approach. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 24322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alrefaei, A.; Ilyas, M. Using Machine Learning Multiclass Classification Technique to Detect IoT Attacks in Real Time. Sensors 2024, 24, 4516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berríos, S.; Garcia, S.; Hermosilla, P.; Allende-Cid, H. A Machine-Learning-Based Approach for the Detection and Mitigation of Distributed Denial-of-Service Attacks in Internet of Things Environments. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 6012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riaz, R.; Han, G.; Shaukat, K.; Khan, N.U.; Zhu, H. A robust anomaly detector for imbalanced industrial internet of things data. J. Comput. Des. Eng. 2025, 12, 46–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alqahtany, S.S.; Shaikh, A.; Alqazzaz, A. Enhanced Grey Wolf Optimization (EGWO) and random forest based mechanism for intrusion detection in IoT networks. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 1916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mante, J.; Kolhe, K. Ensemble of Tree Classifiers for Improved DDoS Attack Detection in the Internet of Things. Math. Model. Eng. Probl. 2024, 11, 2355–2367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priyadharshini, A.; Dhinakaran, S. Optimizing Machine Learning Models for IoT-Based DDoS Attack Detection through Hyper parameter Tuning. J. Comput. Anal. Appl. JoCAAA 2024, 33, 31–40. [Google Scholar]

- Kumari, T.A.; Mishra, S. Tachyon: Enhancing stacked models using Bayesian optimization for intrusion detection using different sampling approaches. Egypt. Inform. J. 2024, 27, 100520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gülsün, B.; Aydin, M.R. Optimizing a Machine Learning Algorithm by a Novel Metaheuristic Approach: A Case Study in Forecasting. Mathematics 2024, 12, 3921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zito, F.; Talbi, E.-G.; Cavallaro, C.; Cutello, V.; Pavone, M. Metaheuristics in automated machine learning: Strategies for optimization. Intell. Syst. Appl. 2025, 26, 200532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Basset, M.; Mohamed, R.; Sallam, K.M.; Chakrabortty, R.K. Light Spectrum Optimizer: A Novel Physics-Inspired Metaheuristic Optimization Algorithm. Mathematics 2022, 10, 3466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, H.; Zhao, D.; Heidari, A.A.; Liu, L.; Zhang, X.; Mafarja, M.; Chen, H. RIME: A physics-based optimization. Neurocomputing 2023, 532, 183–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonius, F.; Sekhar, J.; Rao, V.S.; Pradhan, R.; Narendran, S.; Borda, R.F.C.; Silvera-Arcos, S. Unleashing the power of Bat optimized CNN-BiLSTM model for advanced network anomaly detection: Enhancing security and performance in IoT environments. Alex. Eng. J. 2023, 84, 333–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gharehchopogh, F.S.; Abdollahzadeh, B.; Barshandeh, S.; Arasteh, B. A multi-objective mutation-based dynamic Harris Hawks optimization for botnet detection in IoT. Internet Things 2023, 24, 100952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Yang, H.; Yin, L.; Luo, X. Large-scale IoT attack detection scheme based on LightGBM and feature selection using an improved salp swarm algorithm. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 19165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharif, D.M.; Beitollahi, H. Detection of application-layer DDoS attacks using machine learning and genetic algorithms. Comput. Secur. 2023, 135, 103511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saiyed, M.F.; Al-Anbagi, I. A Genetic Algorithm- and t-Test-Based System for DDoS Attack Detection in IoT Networks. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 25623–25641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhari, S.S.; Yamini, D.A.D. Harris Hawk Optimization-Based Distributed Denial of Service Attack Detection in IoT Networks. In Proceedings of the 4th International Conference for Emerging Technology (INCET), Belgaum, India, 26–28 May 2023; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benmalek, M.; Seddiki, A. Particle swarm optimization-enhanced machine learning and deep learning techniques for Internet of Things intrusion detection. Data Sci. Manag. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SaiSindhuTheja, R.; Shyam, G.K. An efficient metaheuristic algorithm based feature selection and recurrent neural network for DoS attack detection in cloud computing environment. Appl. Soft Comput. 2021, 100, 106997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dey, A.K.; Gupta, G.P.; Sahu, S.P. A metaheuristic-based ensemble feature selection framework for cyber threat detection in IoT-enabled networks. Decis. Anal. J. 2023, 7, 100206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dakic, P.; Zivkovic, M.; Jovanovic, L.; Bacanin, N.; Antonijevic, M.; Kaljevic, J.; Simic, V. Intrusion detection using metaheuristic optimization within IoT/IIoT systems and software of autonomous vehicles. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 22884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Yang, X.; Yin, Y.; Wang, Q. A Novel Hybrid Improved RIME Algorithm for Global Optimization Problems. Biomimetics 2024, 10, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, T.K. Random Decision Forests. In Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Document Analysis and Recognition, Montreal, QC, Canada, 14–16 August 1995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imani, M.; Beikmohammadi, A.; Arabnia, H.R. Comprehensive Analysis of Random Forest and XGBoost Performance with SMOTE, ADASYN, and GNUS Under Varying Imbalance Levels. Technologies 2025, 13, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IoT Threat Classification. Available online: https://kaggle.com/code/tahfimjuwel/iot-threat-classification (accessed on 15 September 2025).

- Rainio, O.; Teuho, J.; Klén, R. Evaluation metrics and statistical tests for machine learning. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 6086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abualigah, L.; Yousri, D.; Elaziz, M.A.; Ewees, A.A.; Al-Qaness, M.A.; Gandomi, A.H. Aquila Optimizer: A novel meta-heuristic optimization algorithm. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2021, 157, 107250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, H.; Rashid, T. FOX: A FOX-inspired optimization algorithm. Appl. Intell. 2023, 53, 1030–1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmadianfar, I.; Bozorg-Haddad, O.; Chu, X. Gradient-based optimizer: A new metaheuristic optimization algorithm. Inf. Sci. 2020, 540, 131–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heidari, A.A.; Mirjalili, S.; Faris, H.; Aljarah, I.; Mafarja, M.; Chen, H. Harris hawks optimization: Algorithm and applications. Future Gener. Comput. Syst. 2019, 97, 849–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Algorithm | Parameter |

|---|---|

| AO | µ = 0.00565, |

| FOX | - |

| GBO | , |

| HHO | |

| RIME | W = 5 |

| AO-RF | FOX-RF | GBO-RF | HHO-RF | RIME-RF | RF | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AS | AVG | 0.94419 | 0.94419 | 0.94417 | 0.94419 | 0.94395 | 0.91215 |

| STD | 2.220 × 10−16 | 2.220 × 10−16 | 6.582 × 10−5 | 2.220 × 10−16 | 5.593 × 10−4 | 2.220 × 10−16 | |

| RS | AVG | 0.94419 | 0.94419 | 0.94417 | 0.94419 | 0.94395 | 0.91215 |

| STD | 2.220 × 10−16 | 2.220 × 10−16 | 6.582 × 10−5 | 2.220 × 10−16 | 5.593 × 10−4 | 2.220 × 10−16 | |

| PS | AVG | 0.96492 | 0.96487 | 0.96487 | 0.96500 | 0.96456 | 0.92042 |

| STD | 1.877 × 10−4 | 1.441 × 10−4 | 1.626 × 10−4 | 1.783 × 10−4 | 9.492 × 10−4 | 1.110 × 10−16 | |

| F1 | AVG | 0.93747 | 0.93748 | 0.93745 | 0.93745 | 0.93719 | 0.90556 |

| STD | 3.889 × 10−5 | 2.982 × 10−5 | 1.029 × 10−4 | 3.694 × 10−5 | 6.361 × 10−4 | 0 | |

| HS | AVG | 5.581 × 10−2 | 5.581 × 10−2 | 5.583 × 10−2 | 5.581 × 10−2 | 5.605 × 10−2 | 8.785 × 10−2 |

| STD | 0 | 0 | 6.582 × 10−5 | 0 | 5.593 × 10−4 | 0 |

| AO-RF | FOX-RF | GBO-RF | HHO-RF | RIME-RF | RF | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AS | AVG | 0.93288 | 0.93298 | 0.93372 | 0.93318 | 0.93376 | 0.91257 |

| STD | 7.023 × 10−4 | 4.639 × 10−4 | 8.872 × 10−4 | 4.977 × 10−4 | 6.032 × 10−4 | 0 | |

| RS | AVG | 0.93288 | 0.93298 | 0.93372 | 0.93318 | 0.93376 | 0.91257 |

| STD | 7.023 × 10−4 | 4.639 × 10−4 | 8.872 × 10−4 | 4.977 × 10−4 | 6.032 × 10−4 | 0 | |

| PS | AVG | 0.94732 | 0.94750 | 0.94871 | 0.94776 | 0.94887 | 0.92092 |

| STD | 1.181 × 10−3 | 8.114 × 10−4 | 1.481 × 10−3 | 1.044 × 10−3 | 9.476 × 10−4 | 3.331 × 10−16 | |

| F1 | AVG | 0.92393 | 0.92405 | 0.92495 | 0.92432 | 0.92497 | 0.90465 |

| STD | 8.894 × 10−4 | 6.238 × 10−4 | 1.104 × 10−3 | 6.328 × 10−4 | 7.806 × 10−4 | 0 | |

| HS | AVG | 6.712 × 10−2 | 6.702 × 10−2 | 6.628 × 10−2 | 6.682 × 10−2 | 6.624 × 10−2 | 8.743 × 10−2 |

| STD | 7.023 × 10−4 | 4.639 × 10−4 | 8.872 × 10−4 | 4.977 × 10−4 | 6.032 × 10−4 | 1.388 × 10−17 | |

| Mean Rank | 5 | 4 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 6 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sasi, M.; Adegboye, O.R.; Alzubi, A. Explainable and Optimized Random Forest for Anomaly Detection in IoT Networks Using the RIME Metaheuristic. Electronics 2025, 14, 4465. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics14224465

Sasi M, Adegboye OR, Alzubi A. Explainable and Optimized Random Forest for Anomaly Detection in IoT Networks Using the RIME Metaheuristic. Electronics. 2025; 14(22):4465. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics14224465

Chicago/Turabian StyleSasi, Mohamed, Oluwatayomi Rereloluwa Adegboye, and Ahmad Alzubi. 2025. "Explainable and Optimized Random Forest for Anomaly Detection in IoT Networks Using the RIME Metaheuristic" Electronics 14, no. 22: 4465. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics14224465

APA StyleSasi, M., Adegboye, O. R., & Alzubi, A. (2025). Explainable and Optimized Random Forest for Anomaly Detection in IoT Networks Using the RIME Metaheuristic. Electronics, 14(22), 4465. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics14224465