A Methodology for Payload Parameter Sensitivity Analysis of Lightweight Electric Vehicle State Prediction

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Load-Oriented Vehicle Dynamics Model

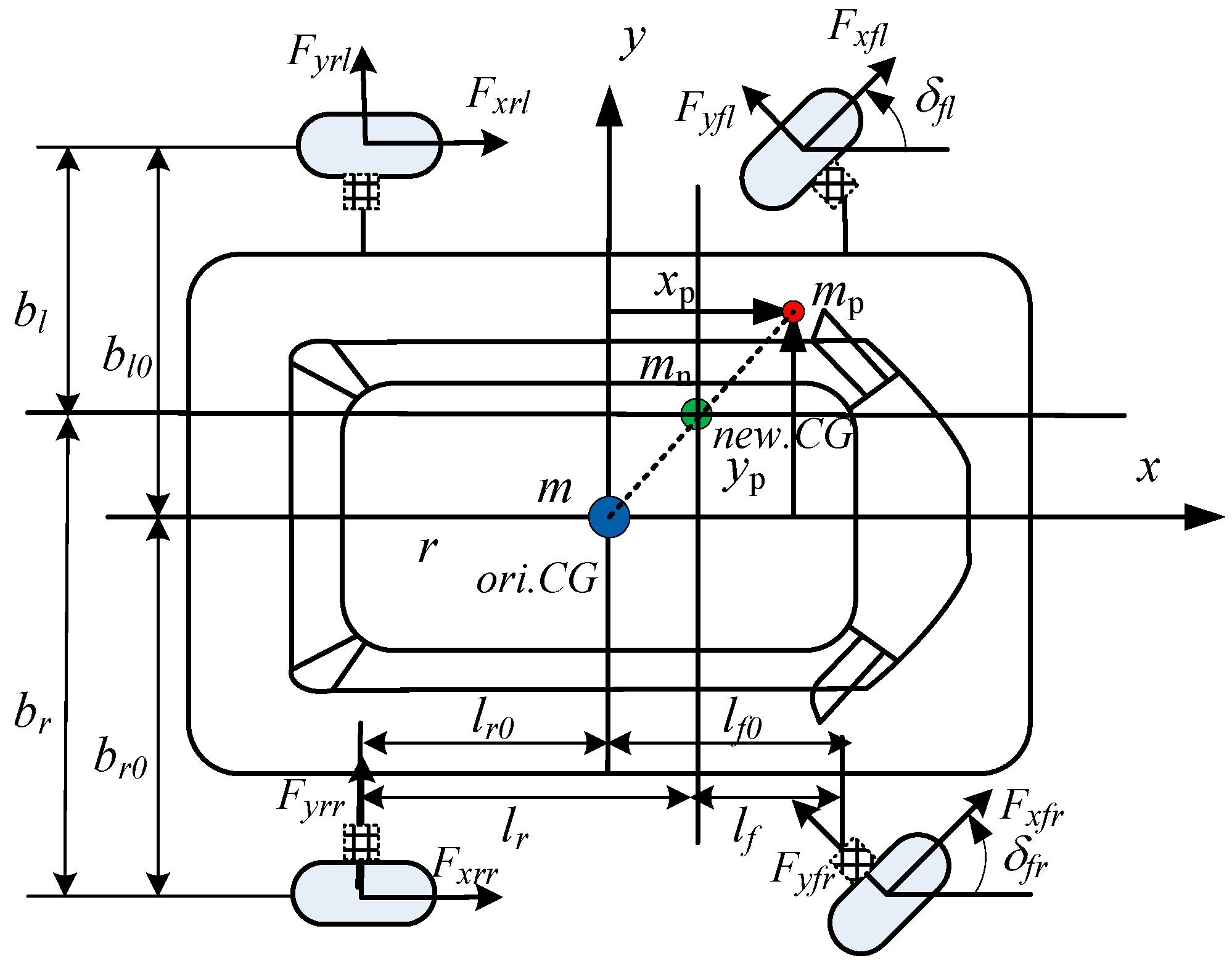

2.1. Vehicle Dynamics Model with Load Parameter Variations

2.2. Nonlinear Tire Model

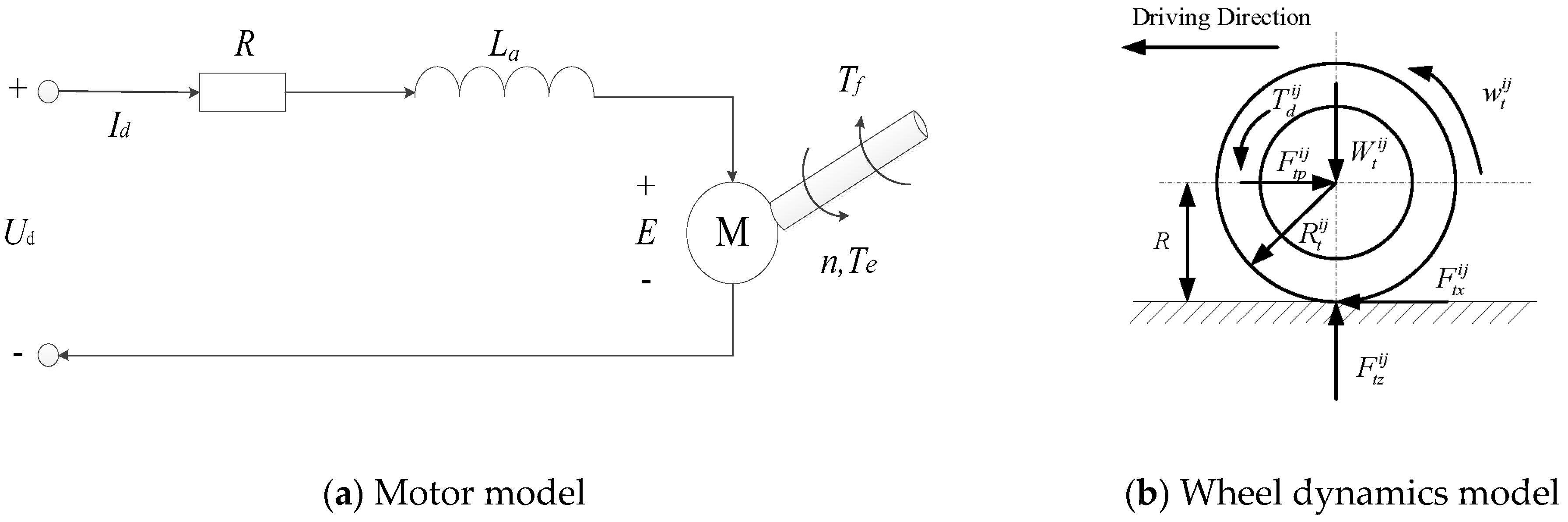

2.3. Motor and Wheel Dynamics Model

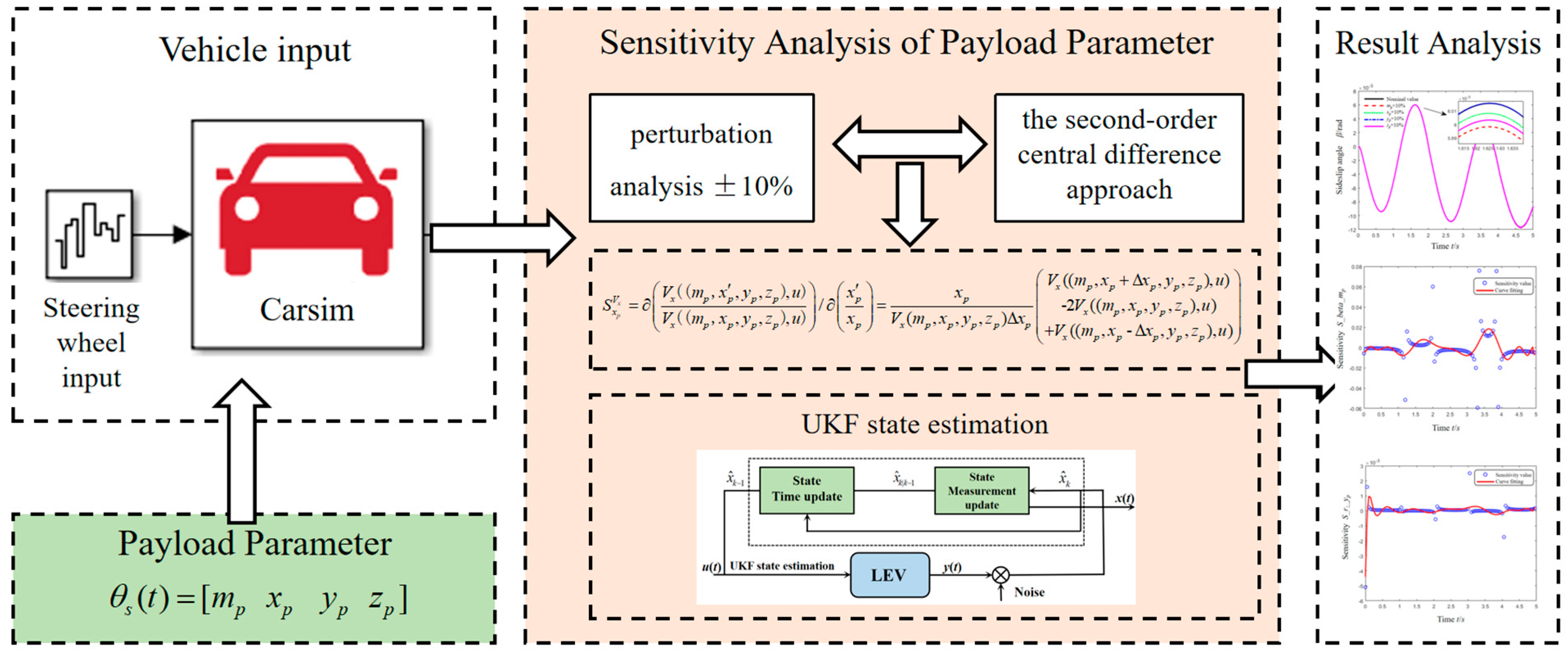

3. Payload Parameter Sensitivity Analysis Approach

3.1. Trajectory Sensitivity of LEV System

3.2. LEV Payload Parameter Sensitivity

- (1).

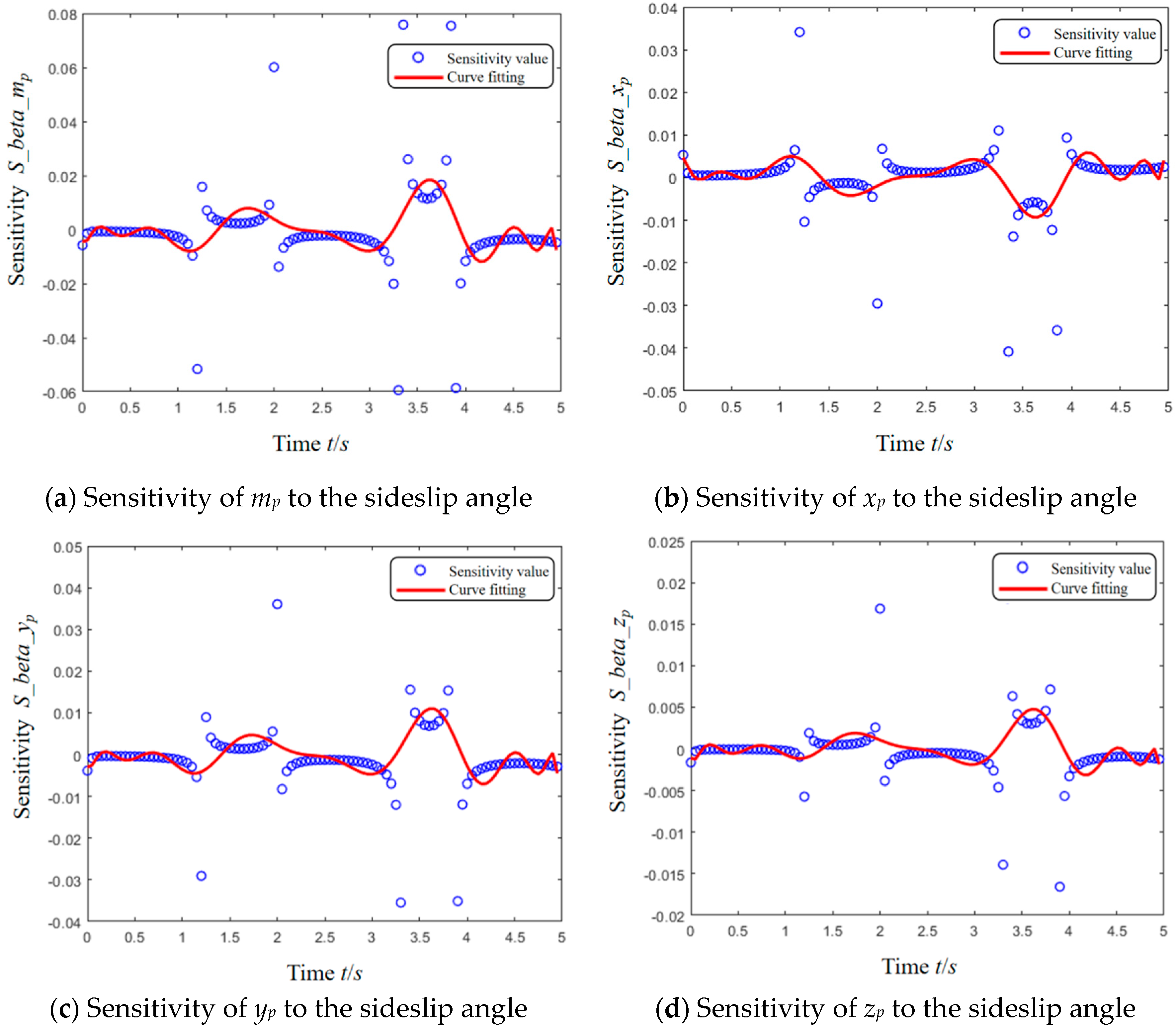

- Based on the definition of partial derivatives, a high-precision numerical differentiator is constructed using the second-order central difference method (Formulas (34)–(38)), and the parameters are dimensionless to ensure comparability.

- (2).

- For each state variable of interest (such as ) and each load parameter (such as ), at each simulation time step k, the instantaneous sensitivity trajectory of the time-varying state is calculated by executing the steps described in Formulas (41)–(44) and (49)–(52).

- (3).

- To further quantify the overall impact of the parameters, the arithmetic mean of the instantaneous sensitivity trajectory is calculated over the entire simulation time domain (Formulas (45)–(48) and (53)–(56)). The obtained results are used for subsequent sensitivity ranking and analysis.

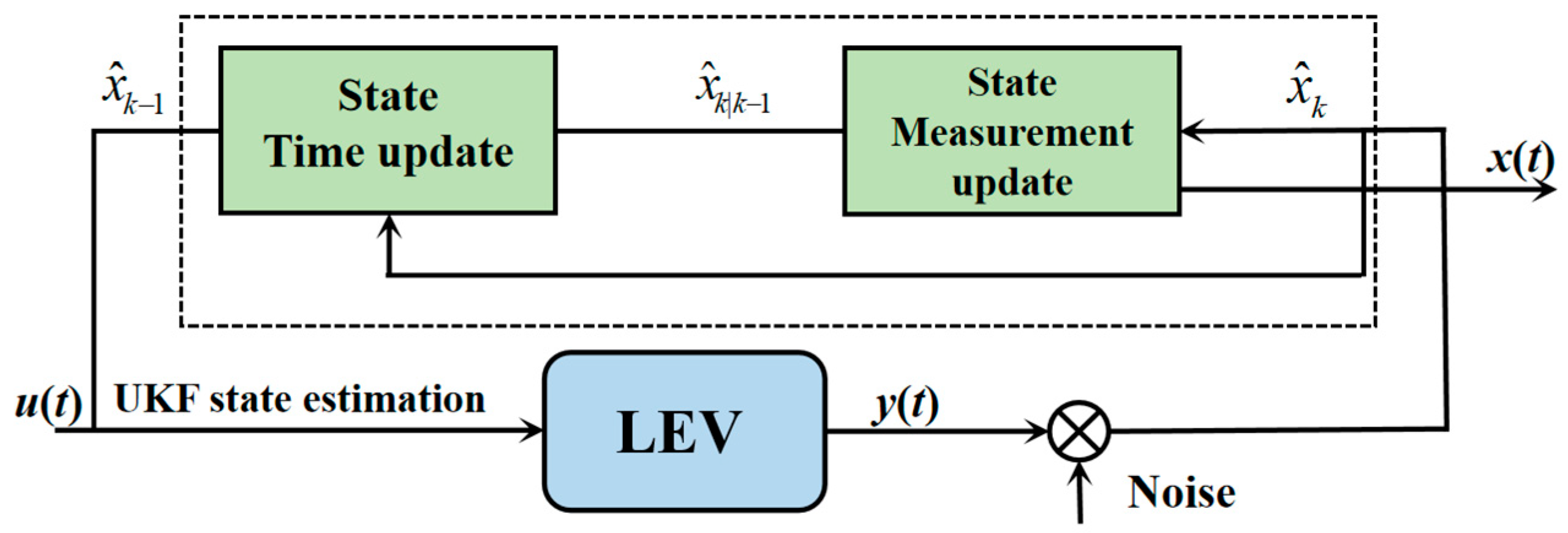

4. Design of Vehicle State Observer System

5. Simulation Result and Analysis

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zhang, H.; Zhang, X.; Wang, J. energy-to-peak control of vehicle lateral dynamics stabilisation. Veh. Syst. Dyn. 2014, 52, 309–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, H.; Zhao, Y.; Nguyen, A.T.; Huang, C. Fault tolerant predictive control with deep-reinforcement-learning-based torque distribution for four in-wheel motor drive. IEEE/ASME Trans. Mechatron. 2023, 28, 668–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farazandeh, A.; Ahmed, A.K.W.; Rakheja, S. An independently controllable active steering system for maximizing the handling performance limits of road vehicles. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part D J. Automob. Eng. 2015, 229, 1291–1309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, X.; Wang, Q.; Yan, Z.; Yang, H.; Yin, G. Integrated robust control of path following and lateral stability for autonomous in-wheel-motor-driven electric vehicles. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part D J. Automob. Eng. 2025, 239, 12696–12706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perić, S.L.; Antić, D.S.; Milovanović, M.B.; Mitić, D.B.; Milojković, M.T.; Nikolić, S.S. Quasi-sliding mode control with orthogonal endocrine neural network-based estimator applied in anti-lock braking system. IEEE/ASME Trans. Mechatron. 2015, 21, 754–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Z.; Guo, X. An ABS control strategy for commercial vehicle. IEEE/ASME Trans. Mechatron. 2015, 20, 384–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Liu, H.; Gao, H.; Shi, P. Reliable fuzzy control for active suspension systems with actuator delay and fault. IEEE Trans. Fuzzy Syst. 2011, 20, 342–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saifia, D.; Chadli, M.; Karimi, H.R.; Labiod, S. Fuzzy control for electric power steering system with assist motor current input constraints. J. Frankl. Inst. 2015, 352, 562–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, S.; Yu, H.; Niu, S.; Jian, L. Power Loss Analysis and Thermal Assessment on Wireless Electric Vehicle Charging Technology: The Over-Temperature Risk of Ground Assembly Needs Attention. Appl. Energ. 2020, 275, 115344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, C.; Liu, W.; He, H.; Chau, K.T. Deep reinforcement learning-based energy management strategy for fuel cell buses integrating future road information and cabin comfort control. Energ. Convers. Manag. 2024, 321, 119032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, D.; Yi, F.; Hu, D.; Li, J.; Yang, Q.; Wang, J. Online optimization of energy management strategy for FCV control parameters considering dual power source lifespan decay synergy. Appl. Energ. 2023, 348, 121516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishna, T.; Krishna, K.R. Sensitivity analysis of tyre characteristic parameters on ABS performance. Vehicle Syst. Dyn. 2020, 60, 47–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Wang, J. Longitudinal motion based lightweight vehicle payload parameter real-time estimations. J. Dyn. Syst. Meas. Control. 2013, 135, 011–013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Todeschini, F.; Corno, M.; Panzani, G.; Fiorenti, S.; Savaresi, S.M. Adaptive cascade control of a brake-by-wire actuator for sport motorcycles. IEEE/ASME Trans. Mechatron. 2014, 20, 1310–1319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Li, L.; Yan, B.; Yang, C.; Tang, G. A hybrid algorithm combining EKF and RLS in synchronous estimation of road grade and vehicle׳ mass for a hybrid electric bus. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2016, 68, 416–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, S.; Lee, C.; Borrelli, F.; Hedrick, J.K. A Novel Approach for Vehicle Inertial Parameter Identification Using a Dual Kalman Filter. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2015, 16, 151–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boada, B.L.; Garcia-Pozuelo, D.; Boada, M.J.L.; Diaz, V. A constrained dual Kalman filter based on pdf truncation for estimation of vehicle parameters and road bank angle: Analysis and experimental validation. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2016, 18, 1006–1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, W.; Feng, J.; Song, B.; Li, X. Huber-Based Robust Unscented Kalman Filter Distributed Drive Electric Vehicle State Observation. Energies 2021, 14, 750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lampe, N.; Ziaukas, Z.; Westerkamp, C.; Jacob, H.-G. Analysis of the Potential of Onboard Vehicle Sensors for Model-based Maximum Friction Coefficient Estimation. In Proceedings of the American Control Conference (ACC), San Diego, CA, USA, 31 May–2 June 2023; pp. 1622–1628. [Google Scholar]

- Ribeiro, A.M.; Moutinho, A.; Fioravanti, A.R.; de Paiva, E.C. Estimation of Tire-Road Friction for Road Vehicles: A Time Delay Neural Network Approach. J. Braz. Soc. Mech. Sci. Eng. 2019, 42, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.J.; Kim, J.S.; Lee, S.H.; Chung, C.C. A Comparative Study of Estimating Road Surface Condition Using Support Vector Machine and Deep Neural Networ. In Proceedings of the IEEE Intelligent Transportation Systems Conference (ITSC), Auckland, New Zealand, 27–30 October 2019; pp. 1066–1071. [Google Scholar]

- Grigorescu, S.; Trasnea, B.; Cocias, T.; Macesanu, G. A survey of deep learning techniques for autonomous driving. J. Field Robot. 2020, 37, 362–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baffet, G.; Charara, A.; Lechner, D. Experimental evaluation of a sliding mode observer for tire-road forces and an extended Kalman filter for vehicle sideslip angle. In Proceedings of the 46th IEEE Conference on Decision and Control, New Orleans, LA, USA, 12–14 December 2007; pp. 3877–3882. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, X.; Wang, Z.; Peng, W. Coordinated control of AFS and DYC for vehicle handling and stability based on optimal guaranteed cost theory. Vehicle Syst. Dyn. 2009, 47, 57–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poussot-Vassal, C.; Sename, O.; Dugard, L.; Savaresi, S.M. Vehicle dynamic stability improvements through gain-scheduled steering and braking control. Vehicle Syst. Dyn. 2011, 49, 1597–1621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, X.; Yin, G.; Chen, N. Advanced estimation techniques for vehicle system dynamic state: A survey. Sensors 2019, 19, 4289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callejo, A.; de Jalón, J.G. Vehicle Suspension Identification Via Algorithmic Computation of State and Design Sensitivities. J. Mech. Design 2014, 137, 021403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, C.; Zhao, C.; Xin, L.; Wang, J. Dynamic impact of unsupported sleepers on railway infrastructure with a coupled MBD-DEM-FDM model. Trans. Geotech. 2024, 45, 101221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Tire Parameters | Longitudinal Tire Force | Lateral Tire Force |

|---|---|---|

| x | s | α |

| C | 1.65 | 1.3 |

| D | ||

| BCD | ||

| E | ||

| Sh | ||

| Sv |

| Parameter | Value | Parameter | Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| mn | 833 kg | Iz | 1017 kg·m2 |

| Ix | 270 kg·m2 | Iy | 750 kg·m2 |

| lf | 1.103 m | bl | 0.7695 m |

| lr | 1.250 m | br | 0.7695 m |

| mp | 80 kg | yp | 0.38 m |

| xp | 0.62 m | zp | 0.29 m |

| Vx0 | 30 km/h | Ts | 0.001 s |

| Payload Parameter Change | mp | xp | yp | zp |

|---|---|---|---|---|

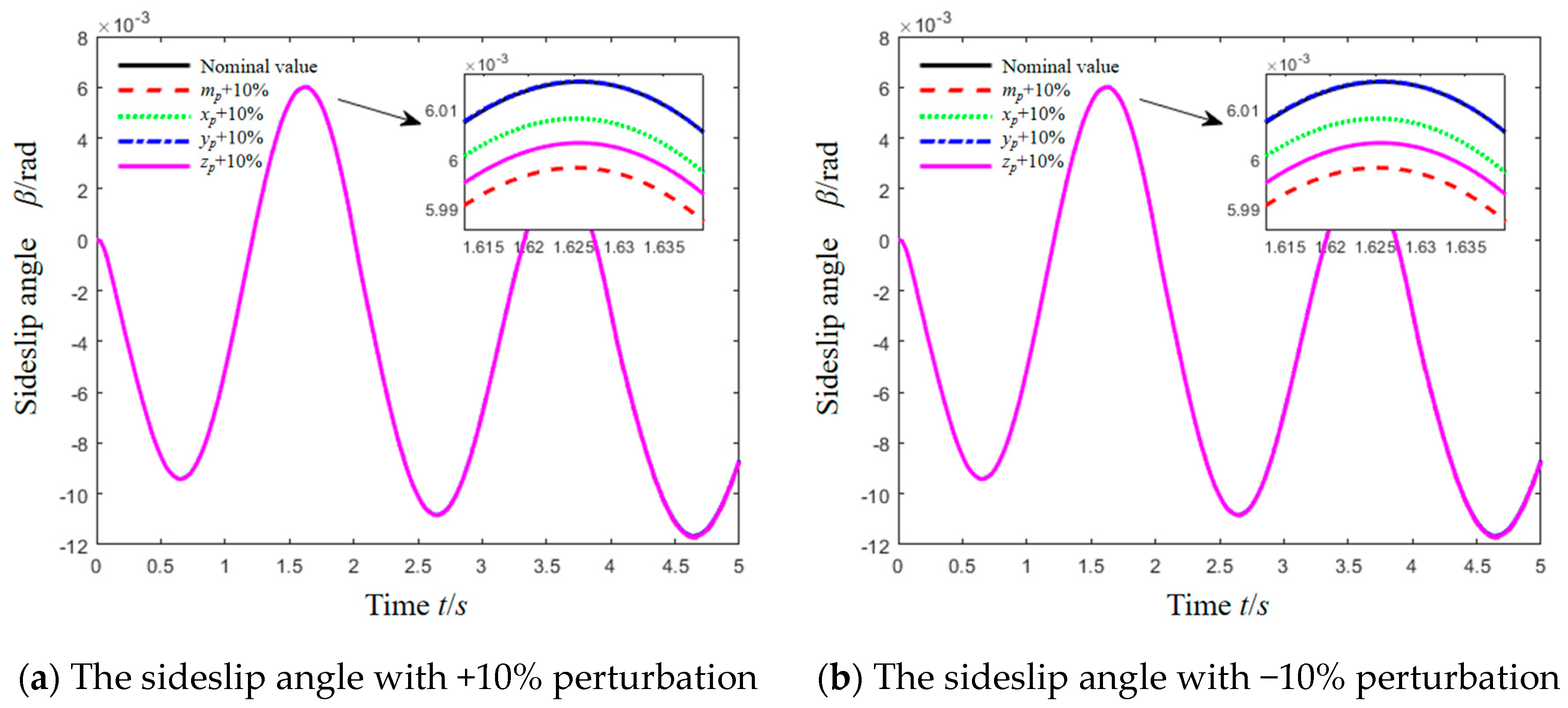

| Sideslip angle ±10% | 2.1516 × 10−2 | 1.1381 × 10−2 | 1.1281 × 10−2 | 5.2239 × 10−3 |

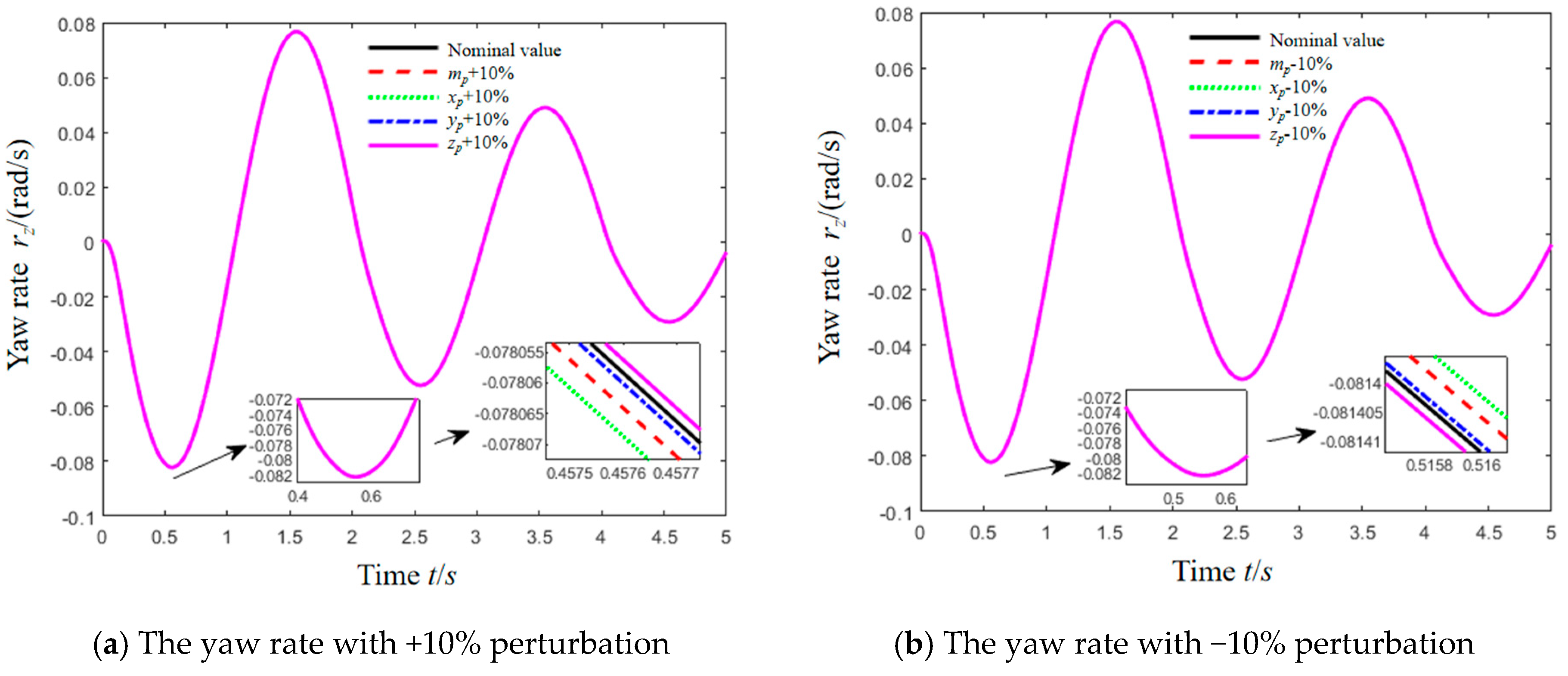

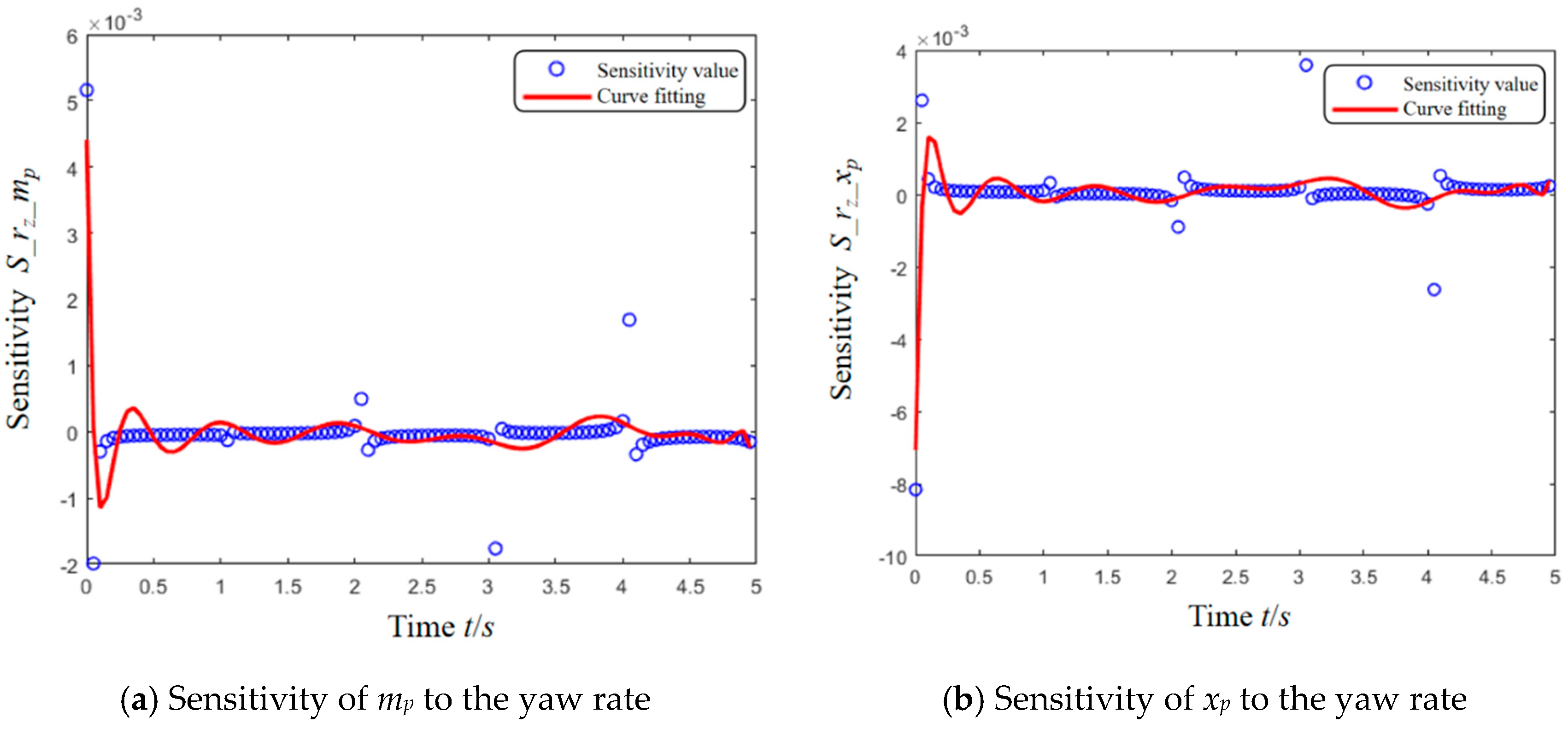

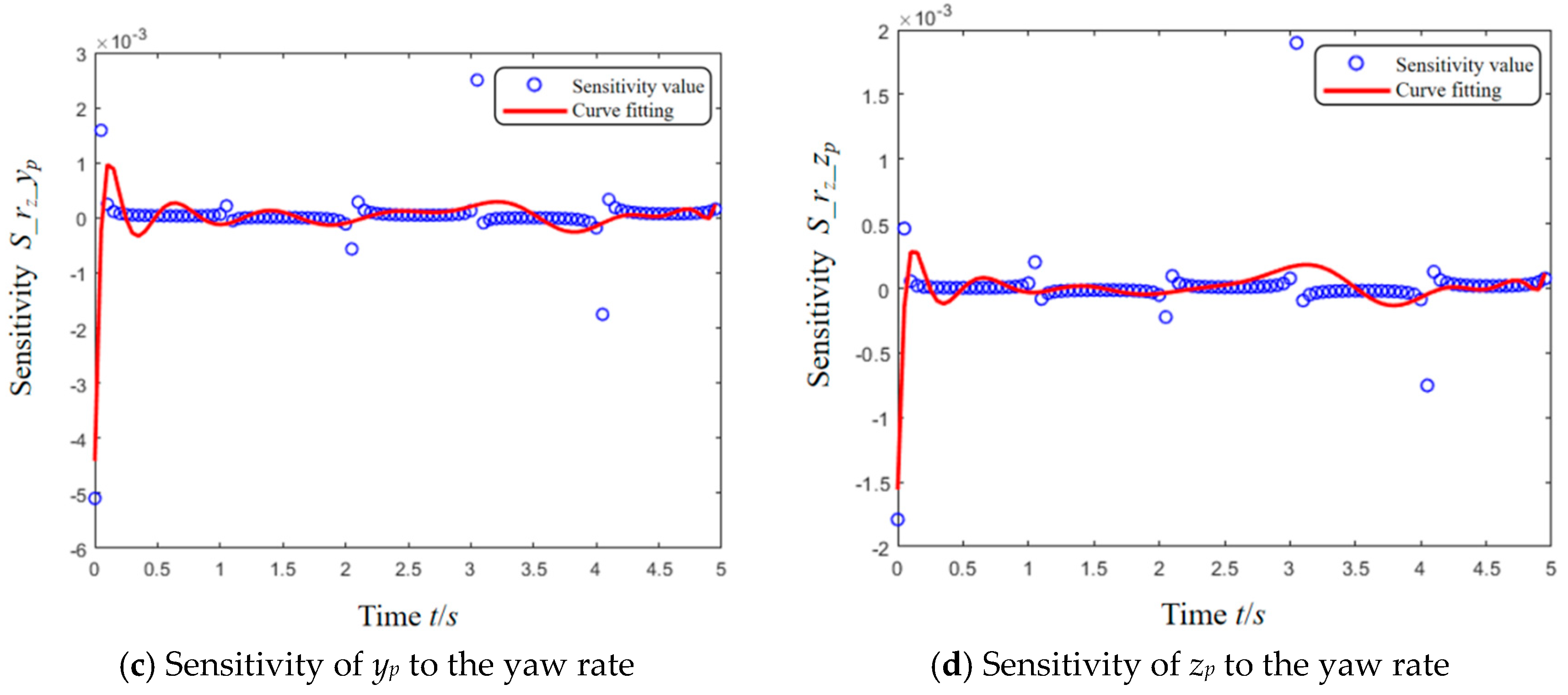

| Yaw rate ±10% | 2.9808 × 10−4 | 4.2395 × 10−4 | 2.6708 × 10−4 | 1.0961 × 10−4 |

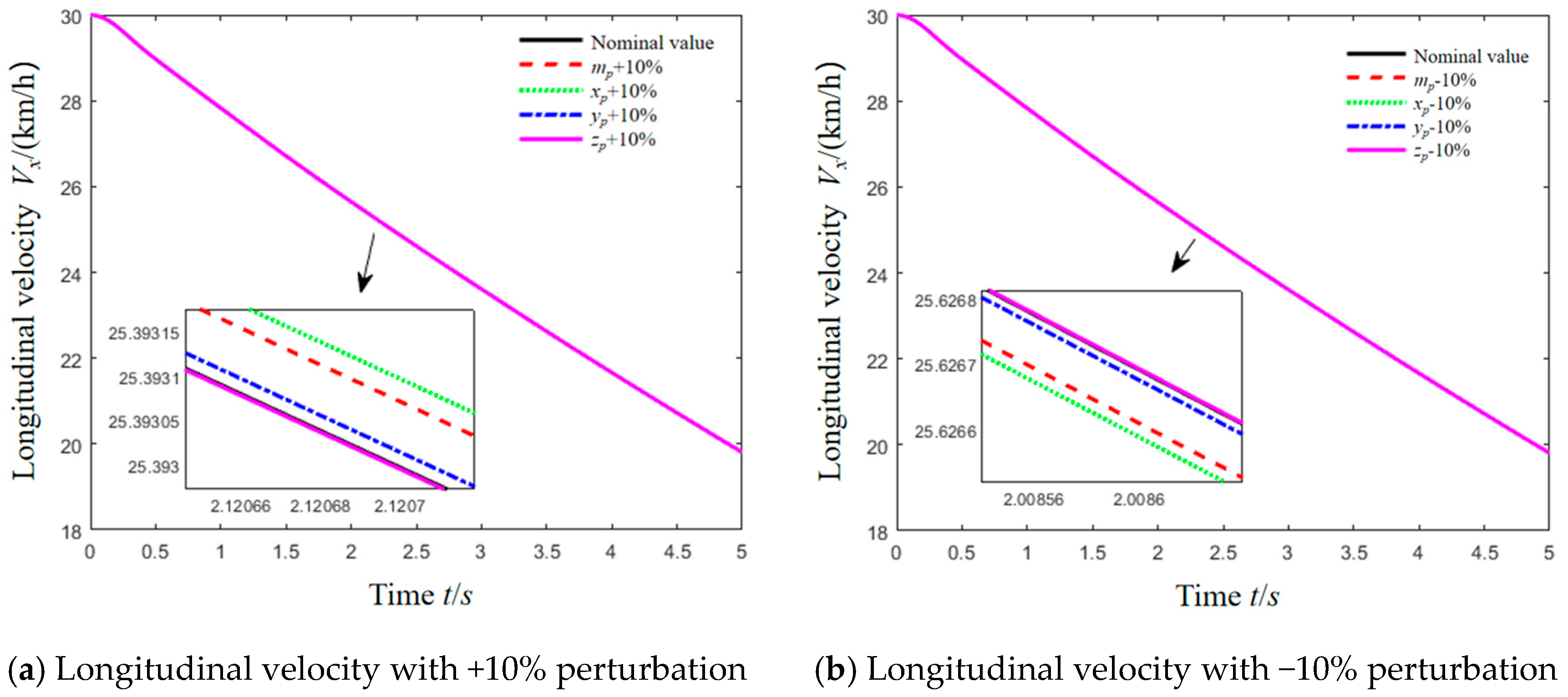

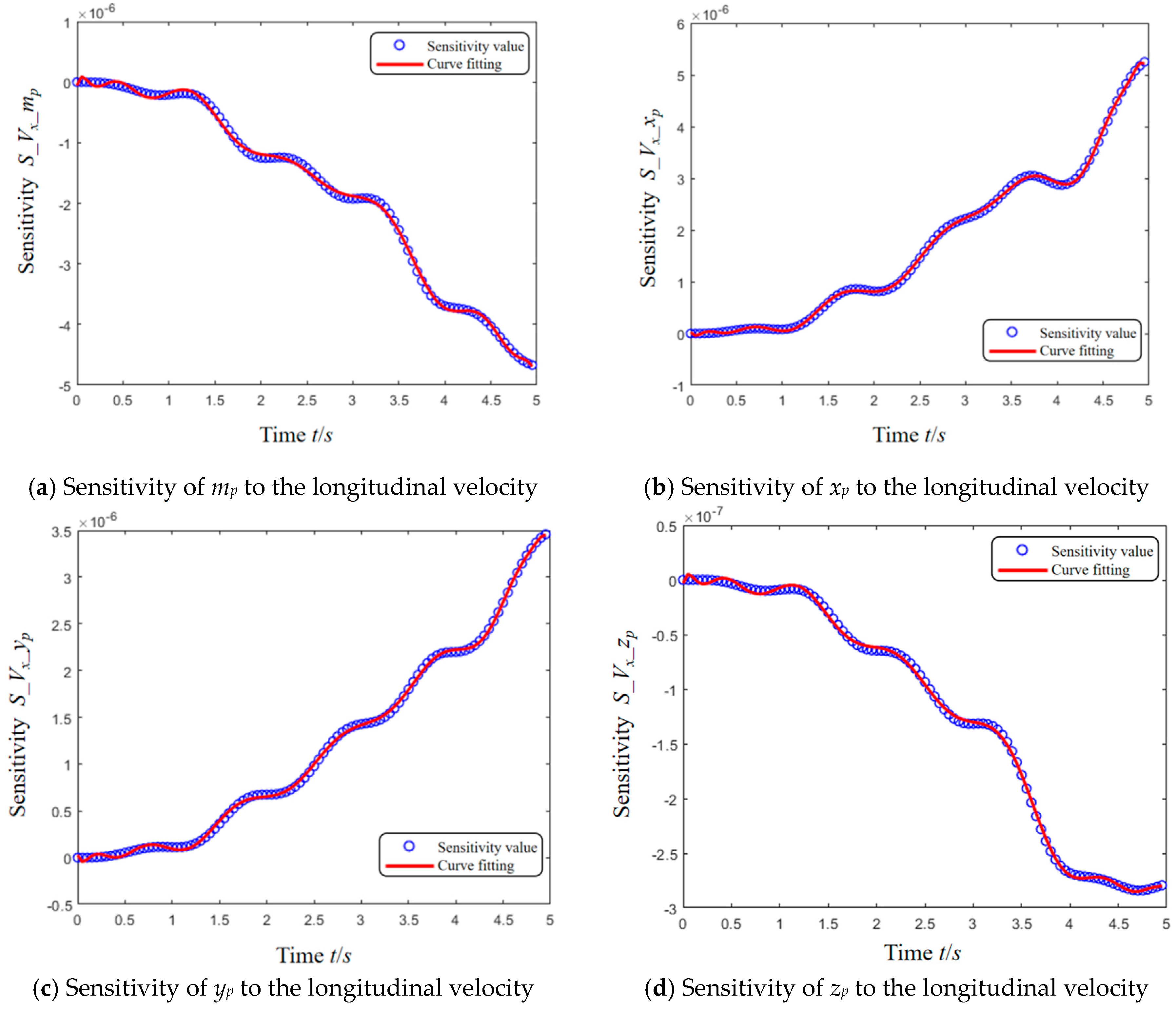

| Longitudinal velocity ±10% | 1.7861 × 10−6 | 1.7510 × 10−6 | 1.2070 × 10−6 | 1.1990 × 10−7 |

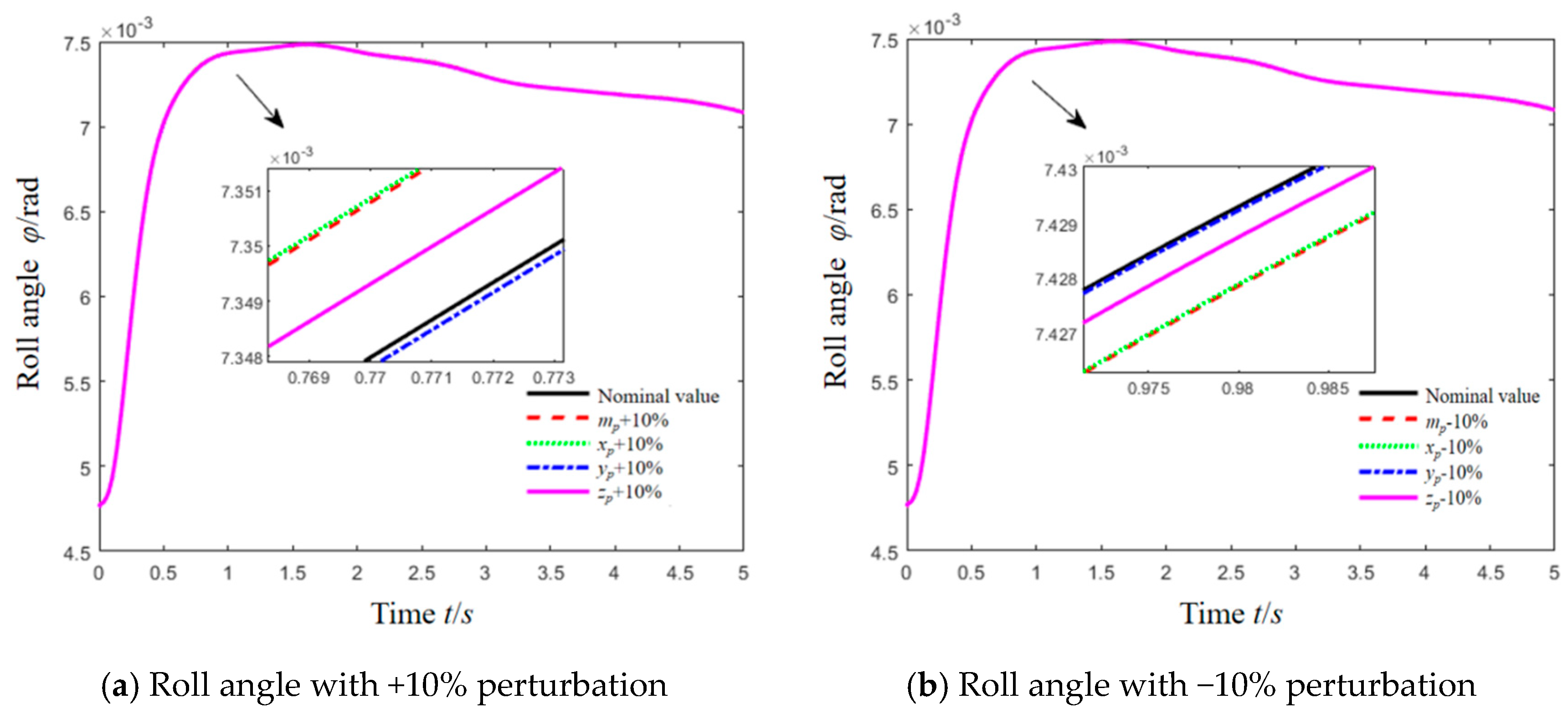

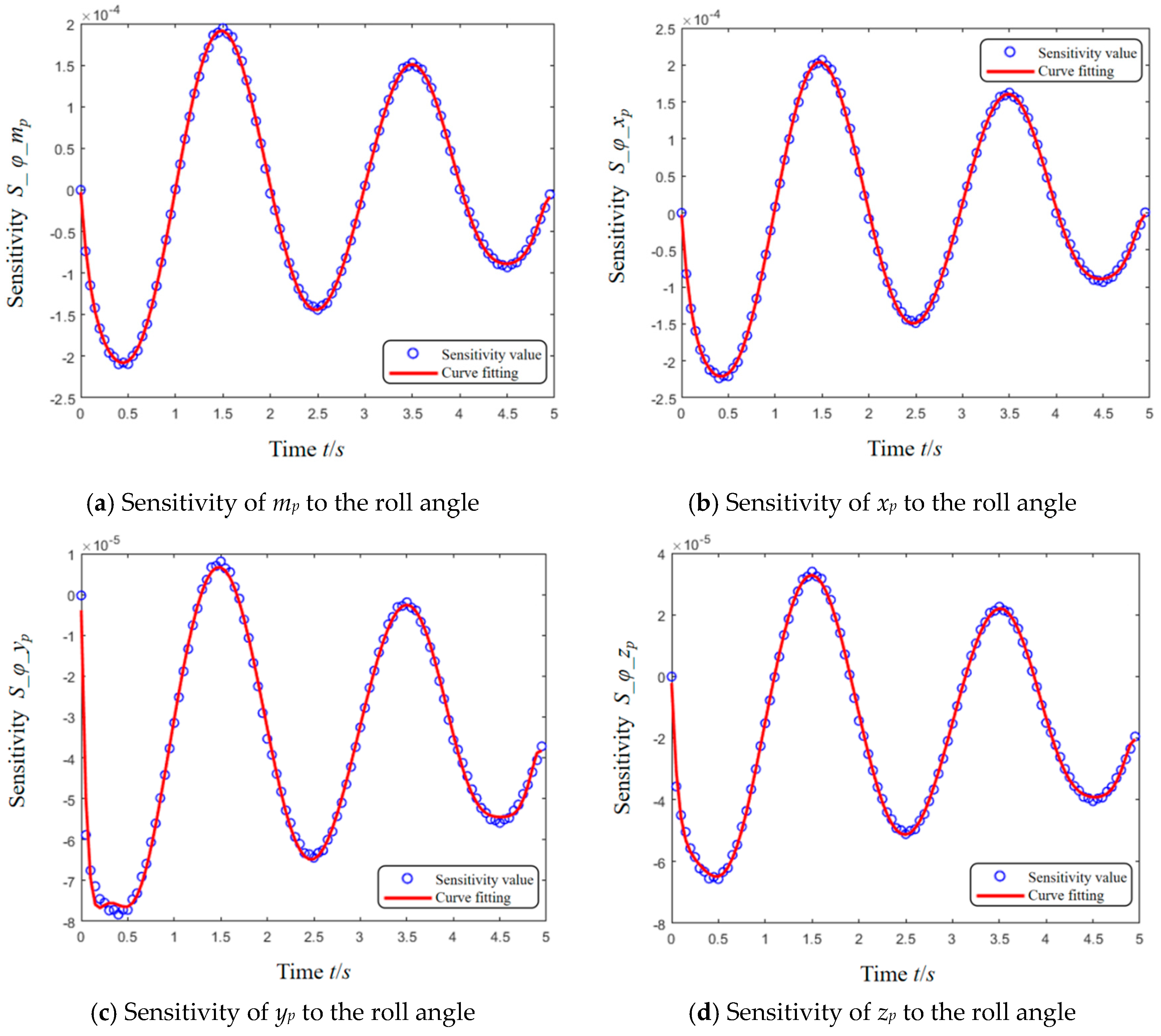

| Roll angle ±10% | 1.0177 × 10−4 | 1.0708 × 10−4 | 3.8248 × 10−5 | 3.0009 × 10−5 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jin, X.; Wang, Z.; Tao, Y.; Lv, J.; Lu, J.; Opinat Ikiela, N.V. A Methodology for Payload Parameter Sensitivity Analysis of Lightweight Electric Vehicle State Prediction. Electronics 2025, 14, 4372. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics14224372

Jin X, Wang Z, Tao Y, Lv J, Lu J, Opinat Ikiela NV. A Methodology for Payload Parameter Sensitivity Analysis of Lightweight Electric Vehicle State Prediction. Electronics. 2025; 14(22):4372. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics14224372

Chicago/Turabian StyleJin, Xianjian, Zhaoran Wang, Yinchen Tao, Jianbo Lv, Jianning Lu, and Nonsly Valerienne Opinat Ikiela. 2025. "A Methodology for Payload Parameter Sensitivity Analysis of Lightweight Electric Vehicle State Prediction" Electronics 14, no. 22: 4372. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics14224372

APA StyleJin, X., Wang, Z., Tao, Y., Lv, J., Lu, J., & Opinat Ikiela, N. V. (2025). A Methodology for Payload Parameter Sensitivity Analysis of Lightweight Electric Vehicle State Prediction. Electronics, 14(22), 4372. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics14224372