Generalizable Interaction Recognition for Learning from Demonstration Using Wrist and Object Trajectories

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Video-based approaches: Video-based representations have become a prominent approach in LfD, leveraging the rich information contained in raw visual data to facilitate the acquisition of manipulation skills. The recent emergence of large-scale annotated video datasets, such as EPIC-KITCHENS [14] and Something-Something [15], has accelerated the development of models capable of extracting detailed spatiotemporal features from human demonstrations. Modern deep learning architectures including 3D Convolutional Neural Networks (3D CNNs), two-stream networks, and Transformer-based models have significantly enhanced the ability to learn from video by capturing both spatial and temporal dynamics [16,17]. Notably, action recognition frameworks such as Temporal Segment Networks (TSNs) [17] and Action Transformer Networks [16] explicitly model long-range temporal dependencies, which are crucial for segmenting and understanding extended manipulation tasks. Additionally, the EPIC-KITCHENS dataset [14] and Something-Something [15] have been central in benchmarking the generalization and robustness of video-based representation learning, promoting the design of systems that can recognize subtle variations in human–object interactions across diverse real-world settings. Recent robotics-focused advancements in this domain have tailored these techniques to the nuances of manipulation learning. For example, Yang et al. [18] proposed a two-stream framework tailored for robotic LfD, combining a grasp detection network to localize manipulable objects with a specialized video captioning network to interpret frame-level and local object dynamics. This method extends beyond generic video captioning by grounding visual semantics in object interactions relevant to robotic tasks. Similarly, Jia et al. [19] employed activity recognition and object detection within a vision-based pipeline, demonstrating the feasibility of learning multi-step skills from human videos using minimal supervision and domain knowledge transfer. Nevertheless, several challenges remain in deploying video-based LfD at scale. Achieving high accuracy often requires large volumes of annotated data and substantial computational resources, limiting adaptability to new tasks and real-time operation on embedded or resource-constrained robotic systems. Moreover, methods that rely solely on RGB or RGB-D data frequently face difficulties with occlusions, viewpoint variation, and background clutter, which are common in real-world environments [14,15,17]. Additionally, most video-based approaches lack explicit grounding in object pose or dynamic constraints, hindering effective policy transfer to physical robots and reducing generalization to scenarios outside the training distribution [18,19].

- Pose-based approaches: Pose-based methods form a fundamental strand of LfD research by representing human demonstrations primarily through the spatial and temporal evolution of skeletal joint positions. Advances in marker-based motion capture and, more recently, markerless pose estimation using deep learning methods such as OpenPose [20], or MediaPipe [21,22] have enabled the efficient extraction of full-body or hand skeletons from videos or sensor data. These representations enable the decomposition of demonstrations into interpretable sub-actions, such as reaching, grasping, or waving, thus facilitating modular skill learning and hierarchical policy design. Recent works have demonstrated the efficacy of skeleton-based recognition models including Graph Convolutional Networks (GCNs) [23], and Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs) [24,25] in capturing fine-grained temporal and spatial features in human motion. For hand-centric manipulation, high-resolution fingertip and wrist trajectories support the nuanced analysis of actions relevant for robotic grasping and in-hand manipulation. Pose-based LfD has been successfully applied to collaborative robotics, teleoperation, and assistive scenarios, where gesture recognition and intent estimation are crucial [19]. Despite these strengths, pose-based methods exhibit several limitations for manipulation-centric LfD. Purely skeletal representations fail to capture object information, impeding the robust recognition of interactions where the object state or context is essential for task understanding. This can lead to ambiguities in action segmentation, especially in environments with clutter, occlusion, or similar gesture sequences involving different objects. Furthermore, the accuracy of pose estimation drops under challenging lighting, occlusion, or camera viewpoints, impacting learning in unstructured real-world settings. Consequently, there is growing interest in hybrid approaches that incorporate object localization and scene context alongside skeleton data to enrich demonstration encoding.

- Object-centric approaches: Object-centric approaches in LfD encode the state and dynamics of manipulated objects, typically as 6-DoF trajectories over time. By prioritizing object motion relative to task goals, these methods decouple learning from the specifics of human kinematics and instead emphasize the manipulation outcome. These representations are particularly effective in tasks such as assembly, insertion, and tool use, where success depends on changes in object states rather than human motion. Recent advances illustrate the potential of this paradigm. Sun et al. [26] proposed a pose-guided imitation learning framework for precise insertion tasks, representing demonstrations as relative Special Euclidean group SE(3) poses between source and target objects. With only 7–10 demonstrations, their method achieved millimeter-level precision, which was aided by a disentangled pose encoder and gated RGB-D fusion to handle noisy pose estimates. In parallel, Hsu et al. [27] introduced SPOT (SE(3) Pose Trajectory Diffusion), which is a trajectory diffusion model that synthesizes SE(3) object pose trajectories directly from demonstrations. By predicting future object-centric trajectories rather than low-level actions, SPOT enabled closed-loop control and cross-embodiment generalization, transferring policies from human video to robotic execution.

2. Methodology

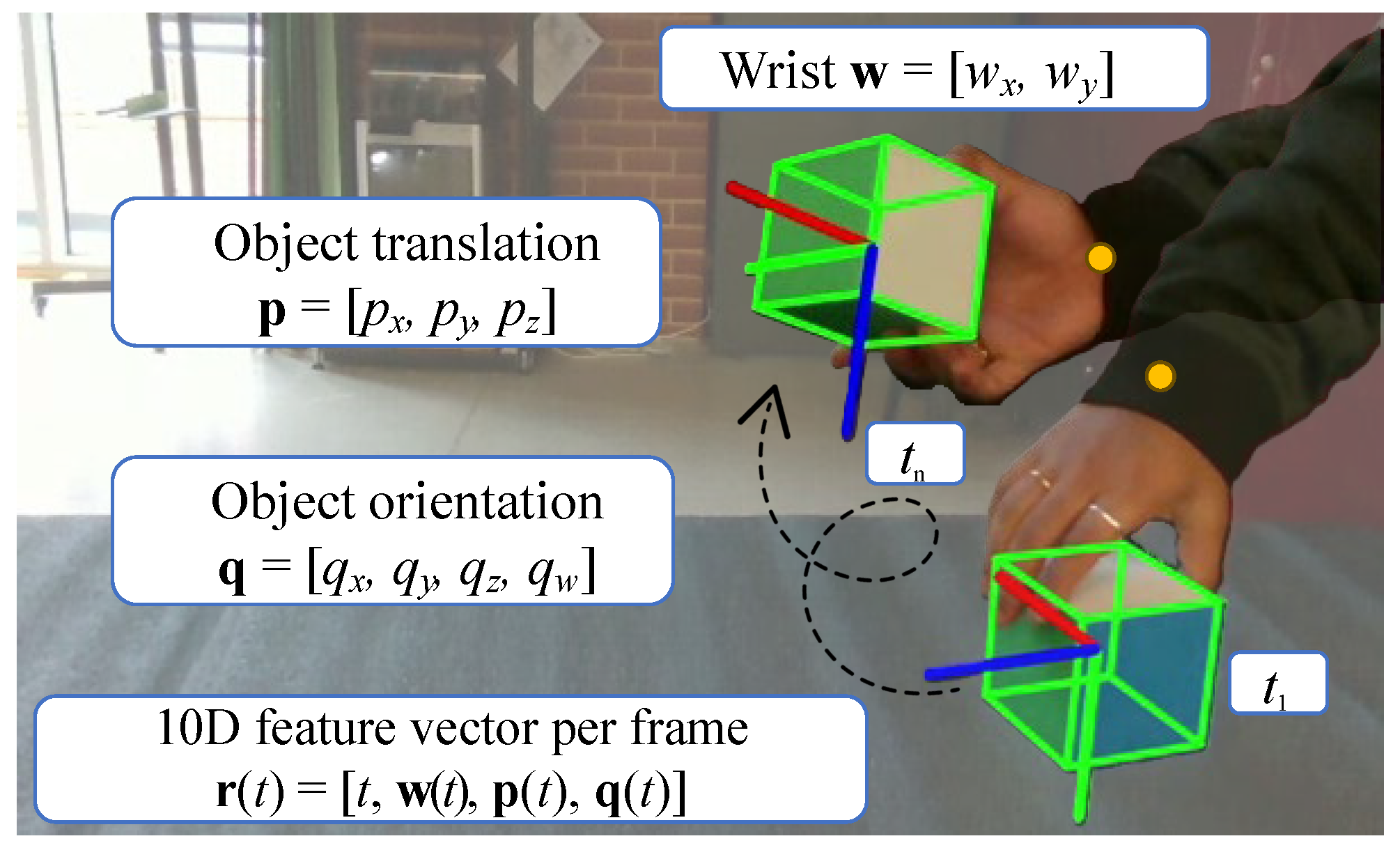

2.1. Problem Formulation

2.2. Approach and Data Preprocessing

2.3. Model Architectures and Training Strategy

2.3.1. Bi-LSTM with Attention

2.3.2. Transformer

3. Evaluation Setup

3.1. GRasping Actions with Bodies (GRAB) Dataset

3.2. First-Person Hand Action (FPHA) Dataset

3.3. Dataset Variations

3.4. Evaluation Metrics

- Classification Accuracy and F1-Score: The overall accuracy measures the proportion of correctly classified sequences, while the macro F1-score balances precision and recall across interaction classes. F1 is particularly important since some categories (e.g., offhandin GRAB, put in FPHA) contain fewer samples, and accuracy alone may overestimate performance on imbalanced datasets.

- Probability Error Metrics: In addition to categorical metrics (accuracy, F1), we report on the Mean Absolute Error (MAE) and Root Mean Squared Error (RMSE) between predicted probability distributions and one-hot ground truth vectors. These measures quantify how far the predicted class probabilities deviate from the target labels, offering a finer-grained view of model calibration and prediction confidence. RMSE penalizes larger probability deviations more heavily, providing insight into model certainty and temporal consistency across different architectures and input representations.

- Efficiency Metrics: Since resource efficiency is essential for LfD deployment, we report on the training time (minutes), inference speed, and GPU/CPU memory usage (MB). These metrics demonstrate real-world deployability in embedded robotics settings where computational resources may be constrained.

3.5. Experiments

- Input Representation Comparison: We evaluate different trajectory representations to assess the benefit of including object orientation information:

- -

- 5D: time + wrist coordinates + object translation ;

- -

- 6D: time + wrist coordinates + object translation ;

- -

- 10D: time + wrist coordinates + full object pose .

This experiment tests whether the inclusion of orientations parameterized as quaternions significantly improves interaction recognition compared to translation-only object tracking. We include a 6D setting to isolate the contribution of object depth (z) before adding orientation. We report accuracy, F1, and probability calibration metrics (MAE, RMSE) for all representations across the GRAB [32] and FPHA [33] datasets. - Temporal Models: We evaluate two temporal modeling architectures using both 10D inputs: Bi-LSTM with attention mechanism and Transformer encoder. This comparison assesses which temporal model better captures the dynamics of compact wrist–object sequences and provides more calibrated probability predictions for LfD applications. Both models are evaluated using identical training protocols and hyperparameters.

- Efficiency Comparison: Using the representation and model combination from Experiments 1–2, we conduct comprehensive efficiency analysis including training time, inference speed, memory footprint, and GPU vs. CPU performance. This experiment evaluates the computational requirements and deployability of our approach in resource-constrained robotics settings.

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Input Representation Comparison

4.2. Temporal Models

4.2.1. GRAB Dataset

4.2.2. FPHA Dataset

4.3. Efficiency Evaluation and Edge Feasibility

- Training Efficiency: GPU training provides a clear speed advantage across both datasets with reductions of up to compared to CPU training. For instance, Bi-LSTM training on the GRAB dataset completes in 89.9 s on GPU versus 612.9 s on CPU, while the Transformer requires 143.8 s and 734.4 s, respectively. The speedup arises from parallelized matrix operations and optimized batch execution on CUDA. Despite longer training times, CPU-only configurations remain practical for smaller datasets such as FPHA (62.3 s for Bi-LSTM), confirming that compact wrist–object representations do not demand large-scale GPU resources.

- Memory Utilization: GPU memory allocation during training remains well below 1.1 GB for both models with the total reserved memory between 2–4 GB. As shown in Table 6, memory requirements scale predictably with representation dimensionality (5D: 217 MB → 6D: 784 MB → 10D: 867 MB GPU allocation), yet all remain within practical deployment limits. This reflects PyTorch’s (v 2.3.1) efficient dynamic allocation and suggests that both architectures can be trained even on mid-range GPUs (e.g., RTX 3060). CPU memory usage ranges from 1.3 GB to 1.9 GB, indicating that training and inference are feasible on standard desktop or embedded systems with ≥8 GB RAM. During inference, both models exhibit extremely lightweight requirements, reserving less than 300 MB of GPU memory and ∼1 GB of CPU memory across all representation sizes.

- Inference Speed and Deployment: Inference latency remains below one second on GRAB (0.26–0.70 s) and below 0.05 s on FPHA for both models, meeting real-time constraints for imitation learning. Transformer models exhibit slightly faster CPU inference (0.03 s vs. 0.05 s on FPHA), indicating their suitability for on-device or embedded deployment. In contrast, the Bi-LSTM shows marginally faster GPU training and superior probability calibration, making it advantageous for fine-tuning or incremental learning.

- Edge Deployment Feasibility: The observed efficiency profile confirms that our 10D wrist–object representation enables training and inference on both high-performance GPUs and compact CPUs without specialized hardware acceleration. As demonstrated in Table 7, with inference times and minimal memory footprint (<1.3GB), both Bi-LSTM and Transformer architectures can be deployed on lightweight robotic platforms or edge devices such as NVIDIA Jetson AGX Orin, Intel NUC, or ARM-based systems. The computational requirements are well within the capabilities of modern edge devices. For instance, the Jetson AGX Orin provides up to 275 TOPS of AI performance with 64 GB memory capacity, easily accommodating our method’s resource demands. This efficiency makes the proposed framework practical for real-time LfD, where data-driven policy updates and online adaptation must occur within strict latency and resource limits.

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Schaal, S. Learning from Demonstration. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1996; Volume 9. [Google Scholar]

- Argall, B.D.; Chernova, S.; Veloso, M.; Browning, B. A survey of robot learning from demonstration. Robot. Auton. Syst. 2009, 57, 469–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Billard, A.; Calinon, S.; Dillmann, R.; Schaal, S. Robot Programming by Demonstration. In Springer Handbook of Robotics; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2008; pp. 1371–1394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chernova, S.; Thomaz, A.L. Modes of Interaction with a Teacher. In Robot Learning from Human Teachers; Chernova, S., Thomaz, A.L., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2014; pp. 17–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravichandar, H.; Polydoros, A.S.; Chernova, S.; Billard, A. Recent Advances in Robot Learning from Demonstration. Annu. Rev. Control. Robot. Auton. Syst. 2020, 3, 297–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osa, T.; Pajarinen, J.; Neumann, G.; Bagnell, J.A.; Abbeel, P.; Peters, J. An Algorithmic Perspective on Imitation Learning. Found. Trends Robot. 2018, 7, 1–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cederborg, T.; Li, M.; Baranes, A.; Oudeyer, P.Y. Incremental local online Gaussian Mixture Regression for imitation learning of multiple tasks. In Proceedings of the 2010 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems, Taipei, Taiwan, 18–22 October 2010; pp. 267–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahmatizadeh, R.; Abolghasemi, P.; Bölöni, L.; Levine, S. Vision-Based Multi-Task Manipulation for Inexpensive Robots Using End-To-End Learning from Demonstration. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1707.02920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finn, C.; Abbeel, P.; Levine, S. Model-Agnostic Meta-Learning for Fast Adaptation of Deep Networks. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1703.03400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, Y.; Andrychowicz, M.; Stadie, B.; Jonathan Ho, O.; Schneider, J.; Sutskever, I.; Abbeel, P.; Zaremba, W. One-Shot Imitation Learning. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems; Guyon, I., Luxburg, U.V., Bengio, S., Wallach, H., Fergus, R., Vishwanathan, S., Garnett, R., Eds.; Curran Associates, Inc.: Long Beach, CA, USA, 2017; Volume 30. [Google Scholar]

- Konidaris, G.; Barto, A. Skill Discovery in Continuous Reinforcement Learning Domains using Skill Chaining. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems; Curran Associates, Inc.: Vancouver, BC, Canada, 2009; Volume 22. [Google Scholar]

- Shan, D.; Geng, J.; Shu, M.; Fouhey, D.F. Understanding Human Hands in Contact at Internet Scale. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2006.06669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feichtenhofer, C.; Fan, H.; Malik, J.; He, K. SlowFast Networks for Video Recognition. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1812.03982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damen, D.; Doughty, H.; Farinella, G.M.; Furnari, A.; Kazakos, E.; Ma, J.; Moltisanti, D.; Munro, J.; Perrett, T.; Price, W.; et al. Rescaling Egocentric Vision: Collection, Pipeline and Challenges for EPIC-KITCHENS-100. Int. J. Comput. Vis. 2022, 130, 33–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goyal, R.; Kahou, S.E.; Michalski, V.; Materzyńska, J.; Westphal, S.; Kim, H.; Haenel, V.; Fruend, I.; Yianilos, P.; Mueller-Freitag, M.; et al. The “something something” video database for learning and evaluating visual common sense. Proc. IEEE Int. Conf. Comput. Vis. 2017, arXiv:1706.04261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girdhar, R.; João Carreira, J.; Doersch, C.; Zisserman, A. Video Action Transformer Network. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Long Beach, CA, USA, 15–20 June 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Xiong, Y.; Wang, Z.; Qiao, Y.; Lin, D.; Tang, X.; Van Gool, L. Temporal Segment Networks for Action Recognition in Videos. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2018, 41, 2740–2755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Zhang, W.; Lu, W.; Wang, H.; Li, Y. Learning Actions from Human Demonstration Video for Robotic Manipulation. Proc. IEEE/RSJ Int. Conf. Intell. Robots Syst. 2019, 1805–1811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, Z.; Lin, M.; Chen, Z.; Jian, S. Vision-based Robot Manipulation Learning via Human Demonstrations. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2003.00385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Z.; Hidalgo, G.; Simon, T.; Wei, S.E.; Sheikh, Y. OpenPose: Realtime Multi-Person 2D Pose Estimation Using Part Affinity Fields. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2021, 43, 172–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lugaresi, C.; Tang, J.; Nash, H.; McClanahan, C.; Uboweja, E.; Hays, M.; Zhang, F.; Chang, C.L.; Yong, M.G.; Lee, J.; et al. MediaPipe: A Framework for Building Perception Pipelines. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1906.08172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.K.; Kumbhare, V.A.; Arthi, K. Real-Time Human Pose Detection and Recognition Using MediaPipe. In Soft Computing and Signal Processing; Reddy, V.S., Prasad, V.K., Wang, J., Reddy, K., Eds.; Springer Nature: Singapore, 2022; pp. 145–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, S.; Xiong, Y.; Lin, D. Spatial Temporal Graph Convolutional Networks for Skeleton-Based Action Recognition. Proc. AAAI Conf. Artif. Intell. 2018, 32, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belluzzo, B.; Marana, A.N. Human Action Recognition Based on 2D Poses and Skeleton Joints. In Intelligent Systems; Xavier-Junior, J.C., Rios, R.A., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Springer, Cham, 2022; pp. 71–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, S.; Lan, C.; Xing, J.; Zeng, W.; Liu, J. Spatio-Temporal Attention-Based LSTM Networks for 3D Action Recognition and Detection. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 2018, 27, 3459–3471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, H.; Wang, Y.; Zhou, Z.; Wang, S.; Yang, H.; Sun, J.; Cao, Q. Exploring Pose-Guided Imitation Learning for Robotic Precise Insertion. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2505.09424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, C.C.; Wen, B.; Xu, J.; Narang, Y.; Wang, X.; Zhu, Y.; Biswas, J.; Birchfield, S. SPOT: SE(3) Pose Trajectory Diffusion for Object-Centric Manipulation. In Proceedings of the 2025 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), Atlanta, GA, USA, 19–23 May 2025; pp. 4853–4860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dang, H.; Allen, P.K. Robot learning of everyday object manipulations via human demonstration. In Proceedings of the 2010 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems, Taipei, Taiwan, 18–22 October 2010; pp. 1284–1289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carfì, A.; Patten, T.; Kuang, Y.; Hammoud, A.; Alameh, M.; Maiettini, E.; Weinberg, A.I.; Faria, D.; Mastrogiovanni, F.; Alenyà, G.; et al. Hand-Object Interaction: From Human Demonstrations to Robot Manipulation. Front. Robot. AI 2021, 8, 714023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Yang, T.; Danelljan, M.; Khan, F.S.; Zhang, X.; Sun, J. Learning Human-Object Interaction Detection Using Interaction Points. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Seattle, WA, USA, 14–19 June 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, E.Z.Y.; Li, Y.; Wang, Y.; Wang, S. Exploring Pose-Aware Human-Object Interaction via Hybrid Learning. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Seattle, WA, USA, 17–21 June 2024; pp. 17815–17825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taheri, O.; Ghorbani, N.; Black, M.J.; Tzionas, D. GRAB: A Dataset of Whole-Body Human Grasping of Objects. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV), Glasgow, UK, 23–28 August 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Hernando, G.; Yuan, S.; Baek, S.; Kim, T.K. First-Person Hand Action Benchmark with RGB-D Videos and 3D Hand Pose Annotations. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 18–23 June 2018; pp. 409–419. [Google Scholar]

- Kirillov, A.; Mintun, E.; Ravi, N.; Mao, H.; Rolland, C.; Gustafson, L.; Xiao, T.; Whitehead, S.; Berg, A.C.; Lo, W.Y.; et al. Segment anything. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, Paris, France, 2–6 October 2023; pp. 4015–4026. [Google Scholar]

- Wen, B.; Yang, W.; Kautz, J.; Birchfield, S. FoundationPose: Unified 6D Pose Estimation and Tracking of Novel Objects. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Seattle, WA, USA, 17–18 June 2024; pp. 18677–18687. [Google Scholar]

- Siami-Namini, S.; Tavakoli, N.; Namin, A.S. The Performance of LSTM and BiLSTM in Forecasting Time Series. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE International Conference on Big Data (Big Data), Los Angeles, CA, USA, 9–12 December 2019; pp. 3285–3292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, A.; Xu, Z.; Li, W.; Chen, Y.; Pan, Y. Urban Signalized Intersection Traffic State Prediction: A Spatial-Temporal Graph Model Integrating the Cell Transmission Model and Transformer. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 2377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehraban, S.; Adeli, V.; Taati, B. MotionAGFormer: Enhancing 3D Human Pose Estimation With a Transformer-GCNFormer Network. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Winter Conference on Applications of Computer Vision (WACV), Waikoloa, HI, USA, 3–8 January 2024; pp. 6920–6930. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.; Yang, Y.; Wu, X.; Li, S. Spatio-temporal transformer and graph convolutional networks based traffic flow prediction. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 24299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xin, W.; Liu, R.; Liu, Y.; Chen, Y.; Yu, W.; Miao, Q. Transformer for Skeleton-based action recognition: A review of recent advances. Neurocomputing 2023, 537, 164–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Do, J.; Kim, M. SkateFormer: Skeletal-Temporal Transformer for Human Action Recognition. In Computer Vision—ECCV 2024; Leonardis, A., Ricci, E., Roth, S., Russakovsky, O., Sattler, T., Varol, G., Eds.; Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2025; Volume 15099, pp. 401–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, D.; Chen, M.; Wu, P.; Wu, M.; Zhang, T.; Li, C. Two-stream spatio-temporal GCN-transformer networks for skeleton-based action recognition. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 4982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, Y.; Ke, Q.; Rahmani, H.; Bailey, J.; Liu, J. IGFormer: Interaction Graph Transformer for Skeleton-Based Human Interaction Recognition. In Computer Vision—ECCV 2022; Avidan, S., Brostow, G., Cissé, M., Farinella, G.M., Hassner, T., Eds.; Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; Volume 13685, pp. 605–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Q.; Liu, H. Multi-Modal Enhancement Transformer Network for Skeleton-Based Human Interaction Recognition. Biomimetics 2024, 9, 123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Jiang, X.; Zhao, Z.; Wang, K.; Yang, Y. Exploring interaction: Inner-outer spatial–temporal transformer for skeleton-based mutual action recognition. Neurocomputing 2025, 636, 130007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Anwer, R.M.; Khan, M.H.; Khan, F.S.; Pang, Y.; Shao, L.; Laaksonen, J. Deep Contextual Attention for Human-Object Interaction Detection. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Seoul, Republic of Korea, 27 October–2 November 2019; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2019; pp. 5693–5701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| (a) | ||||||

| Dataset | Split | Pick | Pass | Inspect | Offhand | Drink |

| GRAB | Train | 183 | 277 | 107 | 56 | 53 |

| Test | 91 | 137 | 52 | 11 | 24 | |

| (b) | ||||||

| Dataset | Split | Close | Open | Put | Pour | |

| FPHA | Train | 60 | 61 | 26 | 61 | |

| Test | 15 | 14 | 7 | 14 | ||

| Input | Accuracy | F1-Score | MAE | RMSE | Training Time (s) | Inference Time (s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5D | 0.927 | 0.928 | 0.117 | 0.225 | 16.5 | 0.26 |

| 6D | 0.931 | 0.928 | 0.107 | 0.204 | 71.0 | 0.65 |

| 10D | 0.946 | 0.948 | 0.079 | 0.149 | 89.9 | 0.70 |

| Model | Device | Accuracy | F1-Score | MAE | RMSE | Training Time (s) | Inference Time (s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bi-LSTM (Attn.) | GPU | 0.946 | 0.947 | 0.079 | 0.149 | 89.90 | 0.70 |

| Bi-LSTM (Attn.) | CPU | 0.905 | 0.909 | 0.142 | 0.307 | 612.88 | 0.68 |

| Transformer | GPU | 0.936 | 0.938 | 0.085 | 0.136 | 143.77 | 0.26 |

| Transformer | CPU | 0.918 | 0.923 | 0.130 | 0.257 | 734.40 | 0.27 |

| Model | Device | Accuracy | F1-Score | MAE | RMSE | Training Time (s) | Inference Time (s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bi-LSTM (Attn.) | GPU | 0.899 | 0.881 | 0.14 | 0.14 | 3.43 | 0.12 |

| Bi-LSTM (Attn.) | CPU | 0.919 | 0.900 | 0.09 | 0.09 | 62.35 | 0.05 |

| Transformer | GPU | 0.940 | 0.939 | 0.06 | 0.06 | 0.97 | 0.15 |

| Transformer | CPU | 0.961 | 0.959 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 14.07 | 0.03 |

| Model | Dataset | Device | Training | Inference | Training Time (s) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CPU Mem (MB) | GPU Alloc (MB) | GPU Rsrv (MB) | CPU Mem (MB) | GPU Alloc (MB) | GPU Rsrv (MB) | ||||

| Bi-LSTM (Attn.) | GRAB | GPU | 1789.17 | 867.07 | 4400.00 | 1128.98 | 310.03 | 942.00 | 89.89 |

| CPU | 1427.76 | – | – | 1068.07 | – | – | 612.88 | ||

| FPHA | GPU | 1349.07 | 103.80 | 248.00 | 990.48 | 49.89 | 68.00 | 3.43 | |

| CPU | 811.54 | – | – | 577.94 | – | – | 62.35 | ||

| Transformer | GRAB | GPU | 1784.89 | 1086.02 | 2090.00 | 1192.53 | 136.88 | 222.00 | 143.77 |

| CPU | 1924.19 | – | – | 1242.82 | – | – | 734.40 | ||

| FPHA | GPU | 1381.73 | 72.75 | 114.00 | 1073.90 | 12.87 | 26.00 | 0.97 | |

| CPU | 822.51 | – | – | 575.06 | – | – | 14.07 | ||

| Representation | Training | Inference | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CPU (MB) | GPU Alloc (MB) | GPU Rsrv (MB) | CPU (MB) | GPU Alloc (MB) | GPU Rsrv (MB) | |

| 5D | 1410.15 | 217.35 | 860.00 | 1016.49 | 93.02 | 238.00 |

| 6D | 1612.19 | 783.81 | 3030.00 | 1072.69 | 207.22 | 744.00 |

| 10D | 1789.17 | 867.07 | 4400.00 | 1128.98 | 310.03 | 942.00 |

| Dataset | Model | Device | Inference Time (s) | Peak Memory (MB) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GRAB | Bi-LSTM | GPU | 0.70 | CPU: 1128.98/GPU: 310.03 |

| CPU | 0.68 | CPU: 1068 | ||

| Transformer | GPU | 0.26 | CPU: 1192.53/GPU: 136.88 | |

| CPU | 0.27 | CPU: 1242.82 | ||

| FPHA | Bi-LSTM | GPU | 0.12 | CPU: 990.48/GPU: 49.89 |

| CPU | 0.05 | CPU: 577.94 | ||

| Transformer | GPU | 0.15 | CPU: 1073.90/GPU: 12.87 | |

| CPU | 0.03 | CPU: 575.06 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pyaraka, J.C.; Isaksson, M.; McCormick, J.; Sutjipto, S.; Sukkar, F. Generalizable Interaction Recognition for Learning from Demonstration Using Wrist and Object Trajectories. Electronics 2025, 14, 4297. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics14214297

Pyaraka JC, Isaksson M, McCormick J, Sutjipto S, Sukkar F. Generalizable Interaction Recognition for Learning from Demonstration Using Wrist and Object Trajectories. Electronics. 2025; 14(21):4297. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics14214297

Chicago/Turabian StylePyaraka, Jagannatha Charjee, Mats Isaksson, John McCormick, Sheila Sutjipto, and Fouad Sukkar. 2025. "Generalizable Interaction Recognition for Learning from Demonstration Using Wrist and Object Trajectories" Electronics 14, no. 21: 4297. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics14214297

APA StylePyaraka, J. C., Isaksson, M., McCormick, J., Sutjipto, S., & Sukkar, F. (2025). Generalizable Interaction Recognition for Learning from Demonstration Using Wrist and Object Trajectories. Electronics, 14(21), 4297. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics14214297