DMBT Decoupled Multi-Modal Binding Transformer for Multimodal Sentiment Analysis

Abstract

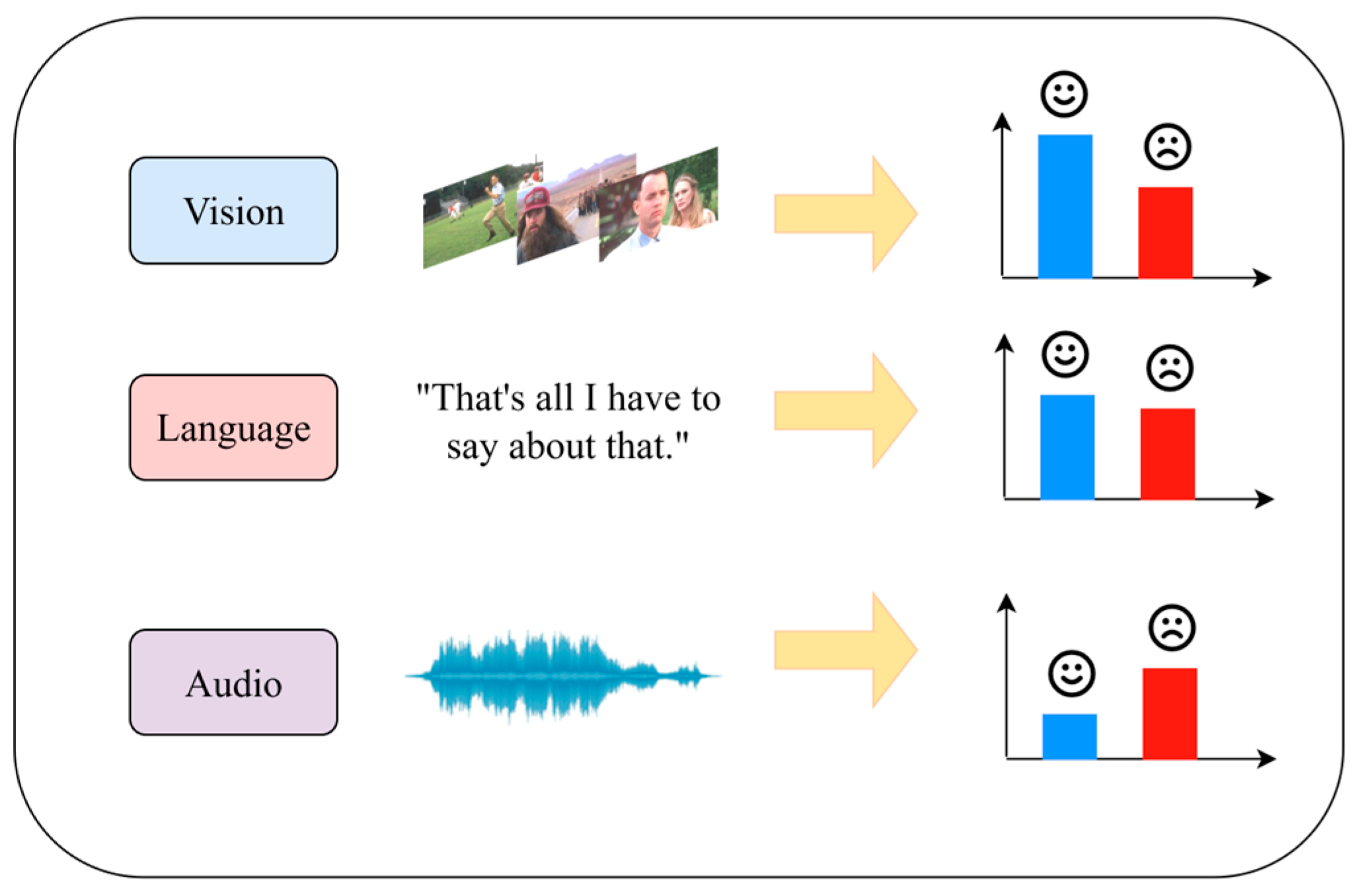

1. Introduction

- ●

- A novel, end-to-end framework for MSA, termed DMBT, is proposed. It systematically addresses the limitations of existing methods through two core innovative modules for feature disentanglement and fusion.

- ●

- An efficient Unsupervised Semantic Disentanglement (USD) module is designed and validated. It integrates an unsupervised, parameter-free paradigm with a language-focused framework, significantly enhancing model efficiency, stability, and disentanglement purity.

- ●

- A new Gated Interaction and Fusion Transformer (GIFT) is constructed, which serves as the core engine of the DMBT model. Its superior performance stems from the synergy between its two integral components: the Multi-modal Binding Transposed Attention (MBTA) and the Dynamic Fusion Gate (DFG).

2. Related Work

2.1. Multimodal Fusion Strategies

2.2. Disentangled Representation Learning

3. Proposed Approach

3.1. Initial Feature Representation

3.2. Unsupervised Semantic Disentanglement (USD)

3.3. Gated Interaction and Fusion Transformer (GIFT)

3.3.1. Common Feature Stream Processing

3.3.2. Specific Feature Stream Processing

3.3.3. Dynamic Fusion Gate (DFG)

3.4. Hierarchical Prediction and Training Objective

4. Experiment

4.1. Datasets and Evaluation Metrics

4.2. Implementation Details

4.3. Main Results and Analysis

4.4. Ablation Study

4.5. Further Analysis

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Xu, P.; Zhu, X.; Clifton, D.A. Multimodal learning with transformers: A survey. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2023, 45, 12113–12132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, D.; Chen, Z.; Wang, Y.; Wang, S.; Li, M.; Liu, S.; Zhao, X.; Huang, S.; Dong, Z.; Zhai, P.; et al. Context de-confounded emotion recognition. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 17–24 June 2023; pp. 19005–19015. [Google Scholar]

- Tsai, Y.H.H.; Bai, S.; Liang, P.P.; Kolter, J.Z.; Morency, L.P.; Salakhutdinov, R. Multimodal transformer for unaligned multimodal language sequences. Proc. Conf. Assoc. Comput. Linguist. Meet. 2019, 2019, 6558. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Liu, S.; Ma, X.; Deng, S.; Suo, Y.; Zhang, J.; Ng, W.W. Lightweight multimodal Cycle-Attention Transformer towards cancer diagnosis. Expert Syst. Appl. 2024, 255, 124616. [Google Scholar]

- Hang, C.N.; Ho, S.M. Personalized Vocabulary Learning through Images: Harnessing Multimodal Large Language Models for Early Childhood Education. In Proceedings of the 2025 IEEE Integrated STEM Education Conference (ISEC), Princeton, NJ, USA, 15 March 2025; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Marquez-Carpintero, L.; Viejo, D.; Cazorla, M. Enhancing engineering and STEM education with vision and multimodal large language models to predict student attention. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 114681–114695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, K.; Hughes, C.E. A unified transformer-based network for multimodal emotion recognition. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2308.14160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ezzameli, K.; Mahersia, H. Emotion recognition from unimodal to multimodal analysis: A review. Inf. Fusion 2023, 99, 101847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poria, S.; Cambria, E.; Bajpai, R.; Hussain, A. A review of affective computing: From unimodal analysis to multimodal fusion. Inf. Fusion 2017, 37, 98–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zadeh, A.; Chen, M.; Poria, S.; Cambria, E.; Morency, L.P. Tensor fusion network for multimodal sentiment analysis. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1707.07250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Shen, Y.; Lakshminarasimhan, V.B.; Liang, P.P.; Zadeh, A.; Morency, L.P. Efficient low-rank multimodal fusion with modality-specific factors. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1806.00064. [Google Scholar]

- Zadeh, A.; Liang, P.P.; Poria, S.; Vij, P.; Cambria, E.; Morency, L.P. Multi-attention recurrent network for human communication comprehension. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, New Orleans, LA, USA, 2–7 February 2018; Volume 32. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Z.; Wan, Z.; Wan, X. Transmodality: An end2end fusion method with transformer for multimodal sentiment analysis. In Proceedings of the Web Conference 2020, Taipei, Taiwan, 20–24 April 2020; pp. 2514–2520. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, H.; Wang, J.; Lin, H.; Zhang, B.; Zhang, Y.; Xu, B. A transformer-based model with self-distillation for multimodal emotion recognition in conversations. IEEE Trans. Multimed. 2023, 26, 776–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gan, C.; Fu, X.; Feng, Q.; Zhu, Q.; Cao, Y.; Zhu, Y. A multimodal fusion network with attention mechanisms for visual–textual sentiment analysis. Expert Syst. Appl. 2024, 242, 122731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Wang, Y.; Yin, G.; Liu, K.; Liu, Y.; Yu, T. Learning language-guided adaptive hyper-modality representation for multimodal sentiment analysis. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2310.05804. [Google Scholar]

- Lei, Y.; Yang, D.; Li, M.; Wang, S.; Chen, J.; Zhang, L. Text-oriented modality reinforcement network for multimodal sentiment analysis from unaligned multimodal sequences. In Proceedings of the CAAI International Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Fuzhou, China, 22–23 July 2023; Springer: Singapore, 2023; pp. 189–200. [Google Scholar]

- Hasan, M.K.; Islam, M.S.; Lee, S.; Rahman, W.; Naim, I.; Khan, M.I.; Hoque, E. Textmi: Textualize multimodal information for integrating non-verbal cues in pre-trained language models. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2303.15430. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, X.; Zhang, X.; Tang, X.; Zhao, J.; Xiong, D.; Ouyang, L.; Yang, B.; Zhou, H.; Ling, B.W.K.; Teo, K.L. MACTFusion: Lightweight cross transformer for adaptive multimodal medical image fusion. IEEE J. Biomed. Health Inform. 2024, 29, 3317–3328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsai, Y.H.H.; Liang, P.P.; Zadeh, A.; Morency, L.P.; Salakhutdinov, R. Learning factorized multimodal representations. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1806.06176. [Google Scholar]

- Hazarika, D.; Zimmermann, R.; Poria, S. Misa: Modality-invariant and-specific representations for multimodal sentiment analysis. In Proceedings of the 28th ACM International Conference on Multimedia, Seattle, WA, USA, 12–16 October 2020; pp. 1122–1131. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, D.; Huang, S.; Kuang, H.; Du, Y.; Zhang, L. Disentangled representation learning for multimodal emotion recognition. In Proceedings of the 30th ACM International Conference on Multimedia, Lisboa, Portugal, 10–14 October 2022; pp. 1642–1651. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, P.; Zhou, Q.; Wu, Y.; Chen, T.; Hu, J. DLF: Disentangled-language-focused multimodal sentiment analysis. Proc. AAAI Conf. Artif. Intell. 2025, 39, 21180–21188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Bai, T.; Wu, B. A cross-temporal contrastive disentangled model for ancient Chinese understanding. Neural Netw. 2024, 179, 106559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Z.; Pan, L.; Guo, X.; Zhao, J. CoDeGAN: Contrastive Disentanglement for Generative Adversarial Network. Neurocomputing 2025, 648, 130478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zadeh, A.; Zellers, R.; Pincus, E.; Morency, L.P. Multimodal sentiment intensity analysis in videos: Facial gestures and verbal messages. IEEE Intell. Syst. 2016, 31, 82–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zadeh, A.A.B.; Liang, P.P.; Poria, S.; Cambria, E.; Morency, L.P. Multimodal language analysis in the wild: Cmu-mosei dataset and interpretable dynamic fusion graph. In Proceedings of the 56th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (Volume 1: Long Papers), Melbourne, VIC, Australia, 15–20 July 2018; pp. 2236–2246. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, J.; Kleinegesse, S.; Comanescu, R.; Radu, O. Recognizing emotions in video using multimodal DNN feature fusion. In Proceedings of the Grand Challenge and Workshop on Human Multimodal Language, Melbourne, VIC, Australia, 20 July 2018; Association for Computational Linguistics: Stroudsburg, PA, USA, 2018; pp. 11–19. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, J.; Comanescu, R.; Radu, O.; Tian, L. Dnn multimodal fusion techniques for predicting video sentiment. In Proceedings of the Grand Challenge and Workshop on Human Multimodal Language (Challenge-HML), Melbourne, VIC, Australia, 20 July 2018; pp. 64–72. [Google Scholar]

- Zadeh, A.; Liang, P.P.; Mazumder, N.; Poria, S.; Cambria, E.; Morency, L.P. Memory fusion network for multi-view sequential learning. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, New Orleans, LA, USA, 2–7 February 2018; Volume 32. [Google Scholar]

- Lv, F.; Chen, X.; Huang, Y.; Duan, L.; Lin, G. Progressive modality reinforcement for human multimodal emotion recognition from unaligned multimodal sequences. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Nashville, TN, USA, 20–25 June 2021; pp. 2554–2562. [Google Scholar]

- Rahman, W.; Hasan, M.K.; Lee, S.; Zadeh, A.; Mao, C.; Morency, L.P.; Hoque, E. Integrating multimodal information in large pretrained transformers. Proc. Conf. Assoc. Comput. Linguist. Meet. 2020, 2020, 2359. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Wang, Y.; Cui, Z. Decoupled multimodal distilling for emotion recognition. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 17–24 June 2023; pp. 6631–6640. [Google Scholar]

| Method | Acc-7 (↑) | Acc-5 (↑) | Acc-2 (↑) | F1 (↑) | Corr (↑) | MAE (↓) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TFN * | 34.9 | 39.39 | 80.08 | 80.07 | 0.698 | 0.901 |

| LMF * | 33.2 | 38.13 | 82.5 | 82.4 | 0.695 | 0.917 |

| EF-LSTM † | 35.39 | 40.15 | 78.48 | 78.51 | 0.669 | 0.949 |

| LF-DNN † | 34.52 | 38.05 | 78.63 | 78.63 | 0.658 | 0.955 |

| MFN † | 35.83 | 40.47 | 78.87 | 78.9 | 0.67 | 0.927 |

| Graph-MFN † | 34.64 | 38.63 | 78.35 | 78.35 | 0.649 | 0.956 |

| MulT | 40 | 42.68 | 83 | 82 | 0.698 | 0.871 |

| PMR | 40.6 | - | 83.6 | 83.6 | - | - |

| MISA † | 41.37 | 47.08 | 83.54 | 83.58 | 0.778 | 0.777 |

| MAG-BERT | 43.62 | - | 84.43 | 84.61 | 0.781 | 0.727 |

| DMD ** | 44.3 | 49.34 | 84.33 | 84.22 | 0.769 | 0.741 |

| DLF | 47.08 | 52.33 | 85.06 | 85.04 | 0.781 | 0.731 |

| DMBT(Ours) | 46.48 | 52.34 | 85.52 | 85.48 | 0.784 | 0.718 |

| Method | Acc-7 (↑) | Acc-5 (↑) | Acc-2 (↑) | F1 (↑) | Corr (↑) | MAE (↓) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TFN * | 50.2 | 53.1 | 82.5 | 82.1 | 0.7 | 0.593 |

| LMF * | 48 | 52.9 | 82 | 82.1 | 0.677 | 0.623 |

| EF-LSTM † | 50.01 | 51.16 | 80.79 | 80.67 | 0.683 | 0.601 |

| LF-DNN † | 50.83 | 51.97 | 82.74 | 82.52 | 0.709 | 0.58 |

| MFN† | 51.34 | 52.76 | 82.85 | 82.85 | 0.718 | 0.575 |

| Graph-MFN † | 51.37 | 52.69 | 83.48 | 83.43 | 0.713 | 0.575 |

| MulT | 51.8 | 54.18 | 82.5 | 82.3 | 0.703 | 0.58 |

| PMR | 52.5 | - | 83.6 | 83.4 | - | - |

| MISA † | 52.05 | 53.63 | 84.67 | 84.66 | 0.752 | 0.558 |

| MAG-BERT | 52.67 | - | 84.82 | 84.71 | 0.755 | 0.543 |

| DMD ** | 53.68 | 54.52 | 85.25 | 85.11 | 0.759 | 0.54 |

| DLF | 53.9 | 55.7 | 85.42 | 85.27 | 0.764 | 0.536 |

| DMBT(Ours) | 53.73 | 56.27 | 85.74 | 85.72 | 0.77 | 0.532 |

| Method | Acc-7 (%) | Acc-2 (%) | F1 (%) | MAE (↓) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DMBT(Ours) | 46.48 | 85.52 | 85.48 | 0.718 |

| Different Modalities | ||||

| only A | 15.45 | 42.23 | 25.07 | 1.468 |

| only V | 15.12 | 42.68 | 28.14 | 1.470 |

| only L | 44.15 | 84.45 | 84.37 | 0.764 |

| L & A | 44.37 | 84.70 | 84.61 | 0.752 |

| L & V | 44.31 | 84.21 | 84.03 | 0.758 |

| Different Components | ||||

| w/o USD | 44.02 | 83.08 | 83.12 | 0.765 |

| w/o MBTA | 45.61 | 84.54 | 83.75 | 0.781 |

| w/o DFG | 44.31 | 83.62 | 83.56 | 0.760 |

| Aggregation Strategy | Acc-7 (%) | Acc-2 (%) | F1 (%) | MAE (↓) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| min(Ours) | 46.48 | 85.52 | 85.48 | 0.718 |

| max | 44.02 | 83.08 | 83.12 | 0.765 |

| mean | 45.61 | 84.54 | 83.75 | 0.781 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Guo, R.; Gong, G.; Jiang, F. DMBT Decoupled Multi-Modal Binding Transformer for Multimodal Sentiment Analysis. Electronics 2025, 14, 4296. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics14214296

Guo R, Gong G, Jiang F. DMBT Decoupled Multi-Modal Binding Transformer for Multimodal Sentiment Analysis. Electronics. 2025; 14(21):4296. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics14214296

Chicago/Turabian StyleGuo, Rui, Gu Gong, and Fan Jiang. 2025. "DMBT Decoupled Multi-Modal Binding Transformer for Multimodal Sentiment Analysis" Electronics 14, no. 21: 4296. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics14214296

APA StyleGuo, R., Gong, G., & Jiang, F. (2025). DMBT Decoupled Multi-Modal Binding Transformer for Multimodal Sentiment Analysis. Electronics, 14(21), 4296. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics14214296