1. Introduction

Recently, deep neural networks (DNNs) reached state-of-the-art performances across many applications [

1], including speech recognition, natural language processing (NLP), and even autonomous and agentic systems. Developing these models however is extremely costly and requires access to large-scale datasets, significant computational power, and a deep expertise in both architecture design and hyperparameter optimization. Due to the substantial amount of resources invested in their development, DNNs are considered highly valuable forms of Intellectual Property (IP) [

2], and ensuring their protection is a crucial concern for both industrial and academic stakeholders.

Up until recently, DNN inference was carried out mainly on high-performance cloud servers. However, as the number of connected devices rapidly increased, this cloud-focused model revealed limitations in terms of scalability, cost, and privacy. Thanks to the TinyML (Tiny Machine Learning) movement [

3] and its investment in edge AI, it has become possible to run lightweight neural networks (NNs) directly on micro-controllers (MCUs) and other low-power hardware such as sensors. Furthermore, through techniques like weight pruning and quantization (usually down to 8-bit integers or even less), TinyML has enabled ultra-low-power on-device intelligence, opening the door to applications ranging from wearable health monitors to real-time assistance in sensor-based systems [

4].

Distributing intelligence across numerous tiny neural networks (NNs) rather than a single centralized model raises the likelihood of IP exposure, as each standalone binary encapsulates a fully trained model that is vulnerable to extraction or reverse engineering [

5]. To mitigate these risks, an optimization of the FreeMark Neural Network Watermarking (NNW) approach by Chen et al. [

6] has been developed for the tiny NN use case, serving both as a safeguard against unauthorized use and as a mechanism for asserting model ownership. Optimizing the original watermarking method proved essential for applying it to the tiny neural network (NN) domain because state-of-the-art watermarking techniques are generally designed for larger models that can absorb additional watermark information without degrading their performance. Furthermore the vast number of parameters available in large NNs enables them to preserve high performance despite intense model alterations aimed at eliminating the embedded watermark (WM) (e.g., weight pruning) or overwriting it (e.g., fine-tuning). The role of over-parameterization in enabling a model to “forget” specific learned information while maintaining high accuracy on the main task is discussed in [

7]. Since networks can also be trivially copied, measures that only protect against tampering or verify integrity are insufficient; watermarks must also be resilient to a wide range of transformations.

Generally, watermarking techniques rely on storing a large amount of WM information in the model parameters, thus porting them to tiny networks is not an easy task: the lower number of available parameters, and the need to operate under strict latency and resources constraints, reduces the capacity of the model to store longer watermarks and makes removal attacks more likely to succeed.

This manuscript explores the applicability of FreeMark, a state-of-the-art NNW technique presented by Chen et al. [

6], to tiny NNs, devising and evaluating an optimized version, Opt-FreeMark, that leverages Singular Value Decomposition (SVD) and Error-Correcting Codes (ECC) to enhance the robustness of the watermarking method enabling its use on tiny NNs. Additionally, the robustness against four attacks, Gaussian noise addition, weight pruning, quantization, and fine-tuning, has been extensively evaluated.

The study shows that with the applied optimizations, Opt-FreeMark maintains its performance and remains resilient against malicious tampering, offering an effective solution for protecting tiny NNs deployed in real edge scenarios.

The paper is organized as follows:

Section 2 presents a review of the state-of-the-art, where different white-box and black-box watermarking methods are presented.

Section 3 examines the deployability of the watermarked models on a standard low-power MCU.

Section 4 offers a technical explanation of the optimized watermarking method.

Section 5 is where the two use cases and experimental results are presented and analyzed. Finally in

Section 6, the conclusions are discussed.

2. State of the Art

Depending on how a watermark (WM) is inserted into a NN, watermarking approaches are typically divided into training-based, fine-tuning-based, or post-training-based [

8]. Early research on DNN watermarking focused on embedding watermarks during the original training process, embedding the WM without degrading model performance on the primary task. However, this is not always practical: training large-scale networks requires a considerable amount of resources. For this reason, many researchers have investigated watermark insertion pipelines via fine-tuning of already-trained models, which makes the process much faster and cheaper [

9]. Beyond training and fine-tuning approaches, post-training watermarking has recently emerged as a compelling, very low-cost alternative; the method described in [

10] is among the first examples of this class of embedding methods. Watermarking schemes are also distinguished based on the data used to detect the WM: techniques are categorized as white-box (WB) if they require internal model information, or black-box (BB) if they rely only on the inputs–outputs relationships [

11].

2.1. White-Box Watermarking

A watermarking technique is called “white-box” if the WM is inserted in the network’s internal parameters and recovered by reading those otherwise hidden parameters. These can be either static, like the network weights, or dynamic, like the neuron activations produced in response to a selected set of inputs. The work by Uchida et al. [

12] is one of the first attempts at static white-box NN watermarking, and it validated the possibility of encoding a bit-string into one or more target layers by introducing a dedicated regularizer to the loss function. Regarding dynamic white-box watermarking, in the work by Rouhani et al. [

13], they used a tailored loss function, modified by adding two regularization terms to the original loss function, altering the feature distributions produced by the target layers.

2.2. Black-Box Watermarking

A watermarking technique is called “black-box” if the WM is encoded in the input–output behavior of the network, since only the output of the model is accessible; therefore, WM extraction is performed by querying the network on a predetermined set of samples and inspecting the final output. Networks may be trained to produce distinctive outputs for particular “triggers”, generating anomalous behaviors that an unmodified model would not exhibit, which is the basis for many backdoor-style black-box watermarking methods. An example is given by the work by Zhang et al. [

14] where the trigger information is embedded into the training samples, creating in this way trigger-based watermarks. A different approach was proposed by Ong et al. [

15], who encouraged the model to generate watermarked images in response to specific triggers by creating a mapping between each trigger and the corresponding output.

3. Deployability on MCU

To evaluate the deployability of the watermarked models, the NUCLEO-STM32H743ZI2 board was used as a reference MCU; the specifics of the board are shown in

Table 1.

The assessment of the memory size required by the two models and their latency was carried out using ST Edge AI Developer Cloud (

https://stedgeai-dc.st.com/home, accessed on 2 October 2025), an online platform that enables the deployment of pre-trained NNs onto specific STM boards, offering an automated optimization and benchmarking pipeline, directly on real MCUs.

Table 2 presents the measurements obtained after deploying the models on the board.

Since neither FreeMark nor Opt-FreeMark required changing the baseline model topologies, the watermarked NNs exhibited identical memory usage (both flash and RAM), inference time, and per-inference energy consumption of the baseline networks.

4. Post-Training Non-Invasive White-Box Watermarking

The FreeMark post-training non-invasive NNW pipeline, presented by Chen et al. in [

6], is based on the idea of indirectly watermarking a model without modifying its parameters by carefully learning its behavior over a set of trigger inputs, extracted from the original training data. The model is queried on a subset of the training data

, which is used to generate a series of activations computed over a target layer

l. These are the features

that will be used to tie the model behavior on the trigger inputs to the WM message. Applying the state-of-the-art approach to the two tiny NNs adopted in this work led to some difficulties in guaranteeing reasonable WM robustness to attacks and model modifications due to the limited number of features that can be extracted from such tiny models. Two modifications were devised and applied to the FreeMark pipeline to enhance its robustness for the “tiny” use case: (I) Applying redundancy to the watermarking message through hamming encoding/decoding, making it more resistant to noise. (II) Instead of simply averaging the

features extracted from the

lth layer using the triggers, Singular Value Decomposition (SVD) is computed over the

matrix, and the

singular values

are kept for further processing. SVD is a mathematical technique that factorizes a real or complex matrix into a rotation followed by a scaling operation that is then followed by another rotation, which is done by decomposing the matrix into three components,

U,

, and

, where

U and

are the matrices containing the left-singular vectors and right-singular vectors, respectively.

is the matrix that contains the singular values representing the intrinsic strength of different data directions. By only keeping the largest singular values, SVD captures the most significant structural information while filtering out minor variations caused by noise. This property makes SVD inherently robust to perturbations. As shown in

Section 5, through these two additional processing steps, the new Opt-FreeMark version becomes much more robust to even the most intense attacks. The same mathematical notation of [

6] is used for the unmodified section of the watermarking and detection flows. Since many objects are created and used during the watermarking process, the main parameters are listed here for clarity:

b: The randomly generated WM vector with length N, b.

: The redundant WM vector with length obtained by applying hamming encoding to b.

: The extracted redundant WM vector with length .

: The extracted WM vector obtained by applying hamming decoding to .

: The subset of trigger inputs extracted from the training data.

: The activations computed over from the lth layer, where M is the number of features extracted from the layer l, and S is the number of samples in .

: Signature computed from the singular values extracted from using SVD.

: An auxiliary vector sampled from a normal distribution , , where K is the number of singular values kept.

: A pair of secret keys, with , and .

: A predetermined threshold, where .

4.1. Embedding the Watermark

Given a host model H, a trigger set is extracted from the training data, so that it contains at least one sample from each class. By querying the model H on , the feature matrix is extracted from the target layer l. SVD is computed over obtaining the singular values matrix, among all the singular values computed through SVD, the top k are kept as the signature of the model while the rest are discarded. The model owner then generates a random binary WM b of length N applying hamming encoding to it, obtaining the redundant WM .

A thresholding function

can be defined as

with

Given a vector

, the thresholding function is applied as follows:

A random auxiliary vector

of length

K is sampled from a normal distribution

. The WM

b is encoded through hamming encoding, obtaining the redundant WM

. The next step is to generate a secret matrix

, such that

This is achieved by randomly initializing

, then for each iteration

, the matrix

A is updated by solving the following optimization problem:

where

is the learning rate. After having generated the secret matrix

, a second secret key

is generated by computing the following:

where

is a scaling factor that solves the following equation:

This process ensures the robustness of the WM, as

is a hyperparameter that can be arbitrarily tuned by the model owner. The secret key generation process is concluded by saving the secret keys

, the scaling factor

, and the subset of trigger inputs

. The secret key generation process is shown in

Figure 1.

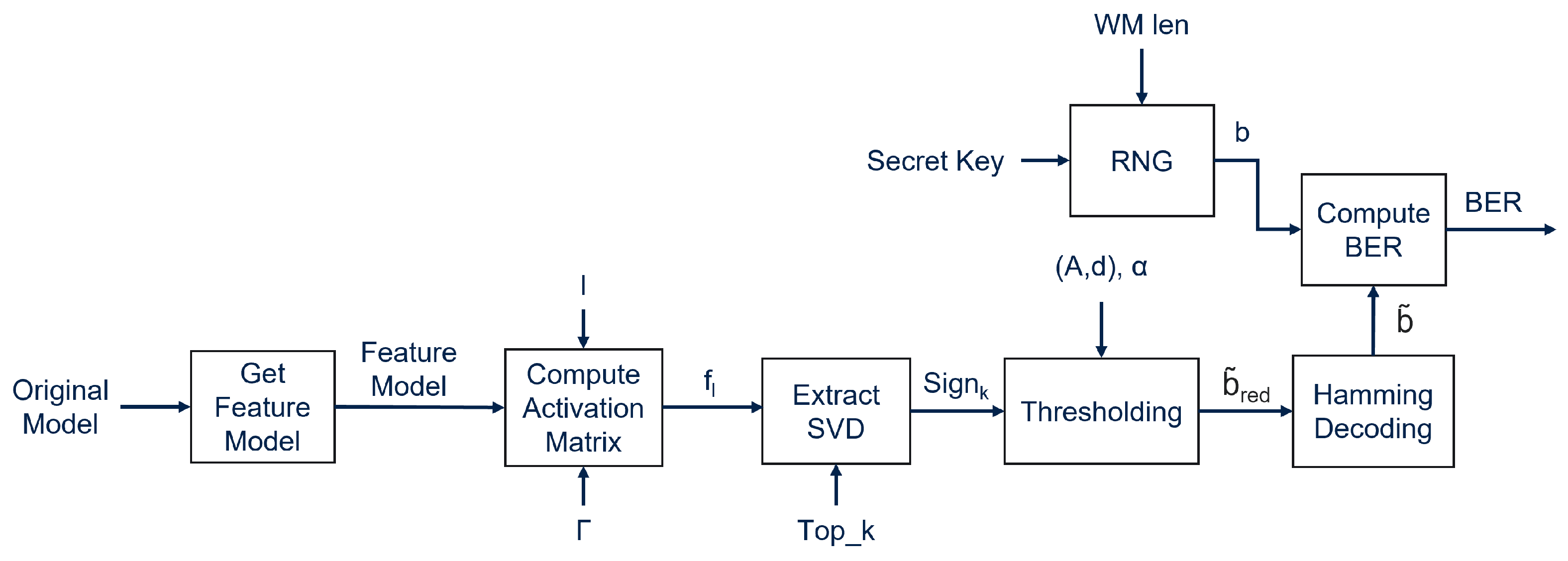

4.2. Extracting the Watermark

To verify if a model is watermarked, the owner of the model can use the trigger set

to query the model, extracting the features

generated by the

lth layer. Now the

singular values

are computed by applying SVD on the features

, and the extracted WM

is computed as follows:

Finally, the extracted WM

is obtained by applying hamming decoding to

. The Bit Error Rate (BER), the percentage of bits differing between two messages, is computed between the original WM

b and the extracted WM

in order to verify the correctness of the extracted WM. If the BER is below the predetermined threshold

, then the WM is considered successfully extracted. The extraction process is shown in

Figure 2.

6. Conclusions

This work explored the applicability of Opt-FreeMark, an optimized version of FreeMark for tiny NN watermarking. Two optimizations have been devised: model signature computation through SVD, and the creation of a noise-resistant watermarking message through ECC. The optimizations are aimed at improving the robustness of the state-of-the-art method when applied to tiny NNs. The proposed technique has been extensively evaluated on four common malicious model modification attacks, Gaussian noise addition, weight pruning, quantization, and fine-tuning, ensuring that the WM remains correctly identifiable even after the models have been subject to powerful modifications. This paper also verified the capability of Opt-FreeMark to withstand ambiguity attacks by using multiple subsets of different types of forged keys and evaluating the accuracy on the WM obtained using them. The results presented in the work confirm the robustness of Opt-FreeMark for tiny NNs against all the attack pipelines explored in the paper, confirming its capability of guaranteeing the model’s IP protection. Future research should address the applicability of Opt-FreeMark to other typical tiny NN domains, such as speech recognition or sensor data analysis, while also exploring other model architectures. The results achieved in the work also underline the importance of designing specialized watermarking techniques for tiny NN architectures.